Abstract

The central Asian Republic of Tajikistan has been an area of extensive historical agricultural pesticide use as well as large scale burials of banned chlorinated insecticides. The current investigation was a four year study of legacy organochlorine pesticides in surface soil and raw foods in four rural areas of Tajikistan. Study areas included the pesticide burial sites of Konibodom and Vakhsh, and family farms of Garm and Chimbuloq villages. These areas were selected to represent a diversity of pesticide disposal histories and to allow assessment of local pesticide contamination in Tajikistan. Each site was visited multiple times and over 500 samples of surface soil and raw foods were collected and analyzed for twenty legacy organochlorine pesticides. Various local food products were sampled to represent the range of raw foods potentially containing residues of banned pesticides, including dairy products, meat, edible plant and cotton seed products. The pesticide analytes included DDTs (DDT, DDD, DDE), lindane isomers (α, β, γ, δ BHC), endosulfan isomers (endosulfan I, II, sulfate), other cyclodienes (aldrin, α and γ chlordanes, dieldrin, endrin, endrin aldehyde and ketone, heptachlor, heptachlor epoxide), and methoxychlor. Pesticide analytes were selected based on availability of commercial standards and known or suspected historical pesticide use and burial. Pesticide contamination was highest in soil and generally low in meat, dairy, and plant products. DDT was consistently the highest measured individual pesticide at each of the four sampling areas, along with BHC isomers and endosulfan II. Soil concentrations of pesticides were extremely heterogeneous at the Vakhsh and Konibodam disposal sites with many soil samples greater than 10 ppm. In contrast, samples from farms in Chimbuloq and Garm had low concentrations of pesticides. Pesticide contamination in raw foods was generally low, indicating minimal transfer from the pesticide sites into local food chains.

Keywords: organochlorine pesticides, Tajikistan, soil, food, contamination

Capsule:

Organochlorine pesticide contamination in Tajikistan was highest in soils at burial sites, with minimal transfer from pesticide sites into local food chains.

1. Introduction

The storage and release of legacy and now obsolete organochlorine pesticides continues to be a global concern because of chemical persistence, toxicity and potential to enter food webs (Loganathan et al. 1994; Kalantzi et al. 2001). Countries of the former Soviet Union, including the Republic of Tajikistan, were the locations of intense agriculture and pesticide use (Sharov et al. 2016). Tajikistan is a mountainous landlocked agrarian-industrial country in central Asia with a population of approximately 8 million, with arable land primarily located in the western portion of the country (UNEP 2007; Zhao et al. 2013). Historically, Tajikistan had several regions of large scale agriculture and extensive pesticide use, with an estimated 63,000 tons of agricultural pesticides delivered for agricultural use between 1965 and 1990 (Juraev 2007). Organochlorine pesticides included aldrin, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor, benzene hexachloride (BHC), chlordane, toxaphene and DDT (UNEP 2007; Juraev 2007). Use of DDT between 1960 and 1970 for growing cotton in Tajikistan was estimated to be 8700 tons per year, primarily in the western regions of the country (Juraev 2007).

Tajikistan is now known to contain several large uncontrolled pesticide burial sites (Juraev 2007; Sharov et al. 2016). These include the Soviet era pesticide disposal site in southwestern Tajikistan near the city of Vakhsh, and the agricultural burial site in the northern Sugd region near the city of Konibodom. Both Vakhsh and Konibodom burial sites have had hundreds of exposed and decomposing pesticide containers at the surface due to uncontrolled surface excavations (ISTC 2015). The Vakhsh burial site has been recognized by both the United Nations and the World Bank as a significant area of obsolete pesticide storage with a high potential to expose humans through direct contact, dust, vapors and cattle grazing (Tauw 2009). An estimated 7,500 to 9,500 tons of pesticides have been buried at Vakhsh, including an estimated 3,000 tons of DDT (Juraev 2007; Tauw 2009). In addition to regional burial sites, smaller stockpiles of pesticides and localized burials have been documented throughout Tajikistan (Juraev 2007; UNEP 2007).

Despite large volumes of uncontrolled storage and burial, there have been only a few studies that have reported concentrations of legacy organochlorine pesticides in environmental or human samples from Tajikistan. Previous preliminary site assessments have shown extremely high pesticide levels in damaged excavated containers (barrels, bags; >10,000 ppm) at the Vakhsh and Konibodom burial sites, and low part per million concentrations of DDT and BHC isomers in surface soils in proximity to pesticide burials, along with numerous other pesticides at generally lower concentrations (Tauw 2009; Juraev 2007). A 1989 study reported generally low pesticide residues (<0.01 to 0.1 ppm) in breast milk of residents of the capital city of Dushanbe, which is distant from areas of pesticide burial (Lederman 1993). A study of mountainous areas across Tajikistan showed concentrations of 0.05 to 0.25 mg/kg of twenty organochlorine pesticides, with concentrations highest in areas closest to agricultural areas (Zhao et al. 2013).

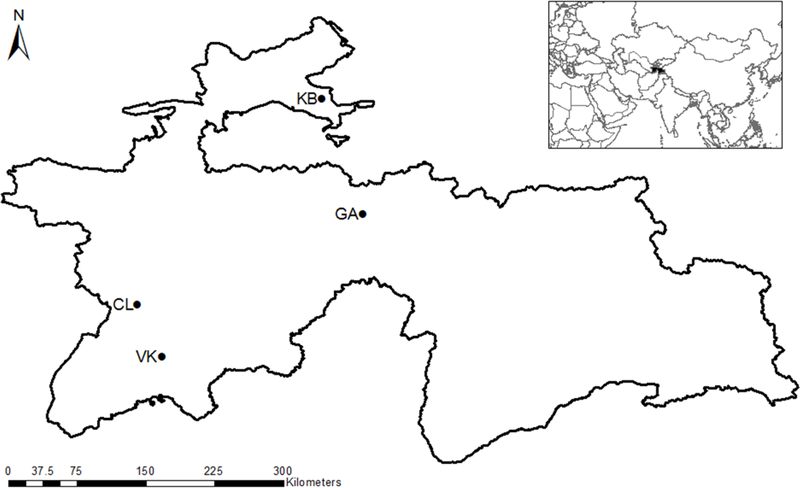

The current investigation was a four year study of obsolete legacy organochlorine pesticides in surface soil and raw foods (meat, dairy products, plant items) in four rural areas of Tajikistan. The four study areas included the burial sites of Konibodom and Vakhsh, and the family farm areas of Garm and Chimbuloq villages (Fig. 1). These areas were selected to represent a diversity of pesticide disposal histories and to allow assessment of local organochlorine pesticide contamination in selected areas of Tajikistan. Each site was visited multiple times and over 500 samples of surface soil and raw foods were collected and analyzed for twenty chlorinated pesticides. Various local food products were sampled to represent the range of raw foods potentially containing residues of banned pesticides. Food samples included a variety of dairy products (milk, fermented milk), raw meat and plant products (fruits, vegetables, nuts), and cotton seed products (seeds, oil, meal). The pesticide analytes included DDTs (DDT, DDD, DDE), lindane isomers (α, β, γ, δ BHC), endosulfan isomers (endosulfan I, II, sulfate), other cyclodienes (aldrin, chlordane isomers, dieldrin, endrin, endrin aldehyde and ketone, heptachlor, heptachlor epoxide), and methoxychlor. Pesticide analytes were selected based on availability of commercial standards and known or suspected historical pesticide use and burial.

Figure 1.

Locations of four pesticide study areas in the Republic of Tajikistan: Konibodom (KB); Garm (GA); Chimbuloq (CL); Vakhsh (VK); see Table SI-1 for details. Insert map shows world location of Tajikistan (black). Mapped using ArcMap v10.3 (Esri, Redmond, CA)

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample locations

Four sampling areas were selected to represent a diversity of pesticide disposal histories and to allow assessment of local pesticide contamination in rural areas of Tajikistan (Fig. 1). The Chimbuloq farming village site (CL) was selected because of no documented historical burial or known current use of organochlorine pesticides, and served as the reference site for the study (Table SI-1). The Garm site (GA) was selected as an example family farm with limited historical banned pesticide use and burial. The farm is located in the village of Karashar, Tajikistan (Table SI-1).

The Vakhsh site (VK) was selected because of its historical use as a Soviet-era pesticide disposal site containing thousands of leaking containers of banned pesticides (Table SI-1). An estimated 7,500–9,500 tons of pesticides were buried at Vakhsh, including an estimated 3,000 tons of DDT (Juraev 2007; Tauw 2009). Vakhsh is a 7.2 ha burial site in a dry grassland area that includes 4 ha of excavated land in seven large trenches with 41 burial pits (Tauw 2009). The site has had hundreds of exposed leaking plastic and corroded metal containers of banned organochlorine pesticides and is used for grazing of goats, cows and sheep from local villages (Table SI-1). Levels of organochlorine pesticides inside excavated pesticide containers mixed with surface soil exceed 5,000 ppm (Juraev 2007). Rural villages are located 4 to 7 km downgradient of the site.

The Konibodom site (KB) was selected because of its historical use as an agricultural pesticide disposal site containing hundreds of exposed, corroded and opened metal containers. An estimated 3,000 tons of pesticides were buried at Konibodom, a 1.4 ha site located within 4 to 11 km to a number of villages (Juraev 2007). Levels of organochlorine pesticides inside excavated pesticide containers mixed with surface soil exceed 5,000 ppm (Juraev 2007). The site is not vegetated and grazing is not known to occur.

2.2. Sample collection and storage

Surface soil and various local food products were sampled to represent the range of raw food products potentially containing residues of banned organochlorine pesticides. Raw food samples included a variety of dairy products (milk, fermented milk), meat, plant products (fruits, vegetables, nuts), and cotton seed products (seeds, oil, meal) (Table SI-1). Soil samples were collected within the top 10 cm with a small shovel, placed into plastic bags, then air dried. Rocks greater than approximately 2 mm were removed prior to solvent extraction and chemical analysis. Food products, including meat, milk products, fruits and vegetables, nuts and cotton seed products were obtained from local markets or villages in proximity to the pesticide sites (Table SI-1). The local origin of the food was determined through interviews with local vendors or residents. Soil was stored at ambient laboratory temperature (10 to 25 °C) and food products were stored at −20 °C prior to solvent extraction.

2.3. Sample processing and extraction

All samples were individually homogenized prior to analysis, then subsamples were extracted following the methods of Klisenko and Kolos (1983) (Table SI-2). Meat was processed with a commercial grinder, whole fruits and vegetables were minced, and nuts, cotton seeds and seed meal were ground. Liquids (milk products, cotton seed oil) were first mixed by shaking. The initial steps of the extraction procedures differed for each matrix as detailed below, whereas the final steps were the same for all sample extracts. The final steps included: 1) reducing the extract volume to 1 to 3 mL by evaporation, 2) bringing the volume to 20 mL with hexane, 3) extracts of meat and dairy products were cleaned three times with 10 mL dilute sulfuric acid (1:5), and 4) reduction to a one mL volume.

For soil processing, a 10 g aliquot was first mixed with 20 mL distilled water and then held at 20 °C for 12 hours. The sample was then shaken for one hour after addition of 40 mL hexane and 10 mL acetone, then centrifuged for 30 min. The precipitate was re-extracted with 10 mL water, 10 mL acetone and 40 mL hexane. The aqueous phases were combined, shaken for 30 min, then centrifuged for 30 min. The precipitate was then rinsed with 10 mL hexane and the extracted aqueous phases were combined and mixed with 80 mL of water. Following phase separation, the hexane layer was collected and dried through 10 g g anhydrous sodium sulfate.

For processing milk and fermented milk products, a 25 mL sample aliquot was first mixed with 5 mL of potassium oxalate and 5 mL of saturated sodium chloride. The sample was shaken for 5 min after addition of 100 mL acetone, then shaken another 5 min after addition of 100 mL chloroform. After separation, the solvent phase was collected, evaporated, then dried with 10 g anhydrous sodium sulfate.

For processing fruit, vegetables and nuts, a 20 g sample aliquot was mixed with 30 mL hexane, shaken for 15 min, then allowed to separate. The sample was re-extracted two more times with 30 mL hexane, and the hexane phases combined, then dried with 10 g anhydrous sodium sulfate.

For processing meat, a 20 g sample aliquot was first mixed with 5 g anhydrous sodium sulfate, then extracted with a 50 mL hexane:50mL acetone by shaking for 3 hr. Following phase separation, the hexane layer was dried with10 g anhydrous sodium sulfate.

For processing cotton products, an aliquot of 20 g seeds or seed meal, or 20 mL cotton oil, was first divided into two parts and each half was extracted separately by mixing with 10 mL hexane for 30 min. Each sample was re-extracted two times with 10 mL hexane followed by shaking for 30 min. Each hexane extract of seed products was filtered through a Buchner funnel prior to combining. All of the hexane extracts were then combined, dried with 10 g g anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the volume was reduced to 30 mL. The extract was then split into two 15 mL portions and frozen for a minimum of 1 hr. Each portion was passed through a column of alumina impregnated with sulfuric acid at rate of 2 mL/min. The column was washed with 50 mL ethyl ether-hexane (15:85) and the purified extracts were combined.

2.4. Chromatography procedures

Over 500 samples of soil and food products were analyzed by gas chromatography (GC-2010plus, Shimadzu) with electron capture detection (ECD-2010 Plus, Shimadzu). Chromatography procedures were optimized for resolution and quantification of twenty organochlorine pesticides. Chromatography specifications and conditions included: 30 m microcapillary column (0.25 mm i.d; df 0.25 μm; Supelco SLB-5ms), 1 uL injection volume, 300°C injection port, helium or nitrogen carrier gas (99.99% purity), 3 mL/min purge flow, 2 mL/min column flow, linear velocity of 47.6 cm/sec (35 mL/min total flow), and 340°C ECD. The column temperature regime included: 150°C for 1 min, ramp to 200°C from 1 to 5 min, 200°C for 5 min, ramp to 250°C over 3 min, then 250°C for 10 min. Pesticides were identified based on comparison of analyte retention time, peak shape, area and resolution to 20 standards (Supelco, 1 mg/mL per analyte; CLP Organochlorine Pesticide Mix; Sigma Aldrich). Only sample peaks eluting within the retention time window (+/− 0.03 min) of each standard were quantified. Pesticides were quantified from calibration curves developed at concentrations of 0.005, 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1 ug/mL (helium) or 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10 ug/mL (nitrogen).

2.5. Quality assurance and data analysis

Quality assurance procedures included analysis of clean matrix spikes, solvent blanks, and sample extract spikes with individual standards. Reporting limits for the detection of pesticides in extracts were determined to be an area of 100,000 uV/min (approximated the lowest calibration standard response). Extracts with a response area equal to or greater than 10,000,000 uV/min were diluted and re-chromatographed. Sample data from chromatograms with poorly resolved peaks or shifted retention times were excluded from data analysis. Pesticide concentrations were reported without correction for spike recoveries which ranged from 70 to 110%. Concentrations of pesticide analytes (ppm) are reported in graphical summaries as the mean and standard error. The mean and standard deviation of pesticide concentrations in each matrix (soil, meat, dairy, fruit/nut/vegetable, or cotton) were computed for all samples collected during the four year study that met quality assurance and quality control requirements. Correlations between pesticide levels and sample time were determined by simple linear regression. For each study site, graphical summaries were developed for specific analytes (e.g., DDD, DDE, DDE), and for analyte groups (e.g., DDTs, BHCs, endosulfans/chlordanes, other cyclodienes/heptachlors).

3. Results

3.1. General trends

Pesticide contamination was highest in soil at each of the four sites, and generally low in meat, dairy, and plant products (Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5). DDT was consistently the highest measured individual pesticide at each of the four sampling areas, along with BHC isomers and endosulfan II. Soil concentrations of DDD and DDE were substantially lower than levels of DDT at each site. At all four sites, 7 of the 20 analytes were either not detected or only present at trace (<0.1 ppm) levels: heptachlor, heptachlor epoxide B, methoxychlor, endrin ketone, aldrin, endrin, and endosulfan sulfate. Soil concentrations of pesticides were extremely heterogeneous at the Vakhsh and Konibodam disposal sites with many samples greater than 10 ppm. In contrast, samples from Chimbuloq and Garm had generally low concentrations of pesticides. Summary of all pesticide concentrations are provided in the Supplemental Information (Table SI-3).

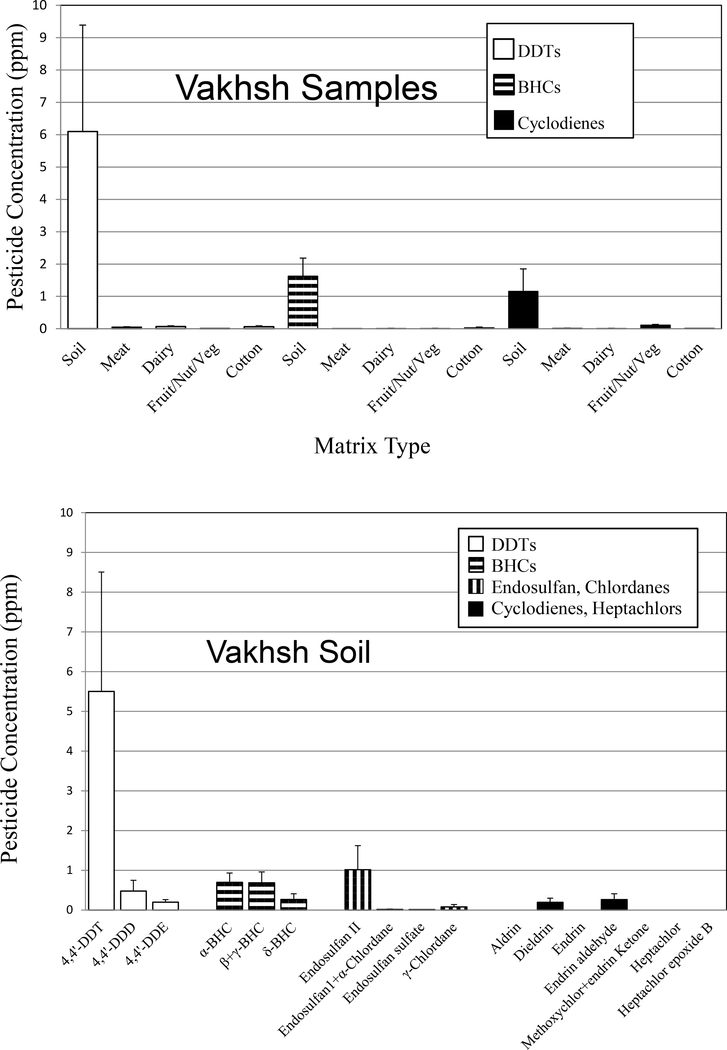

Figure 2.

Pesticide concentrations in samples from the Vakhsh burial site (ppm; mean, standard error). Top Panel: Concentrations of DDTs (sum of 4,4’-DDT, 4,4’-DDD, 4,4’-DDE isomers), BHCs (sum of α, β, γ, δ lindane isomers), and cyclodienes (sum of aldrin, dieldrin, and chlordane, endrin, endosulfan, and heptachlor isomers) in Vakhsh surface soil and raw food products. Bottom Panel: Concentrations of individual pesticides in Vakhsh surface soil samples.

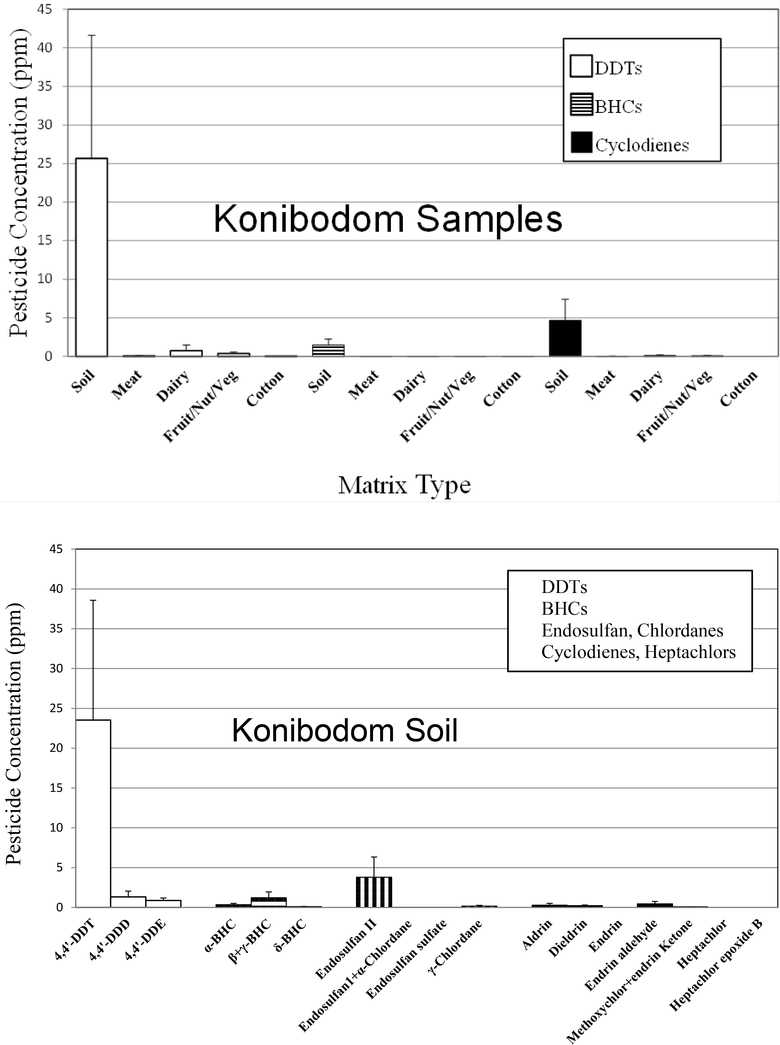

Figure 3.

Pesticide concentrations in samples from the Konibodom burial site (ppm; mean, standard error). Top Panel: Concentrations of DDTs (sum of 4,4’-DDT, 4,4’-DDD, 4,4’-DDE isomers), BHCs (sum of α, β, γ, δ lindane isomers), and cyclodienes (sum of aldrin, dieldrin, and chlordane, endrin, endosulfan, and heptachlor isomers) in Konibodom surface soil and raw food products. Bottom Panel: Concentrations of individual pesticides in Konibodom surface soil samples.

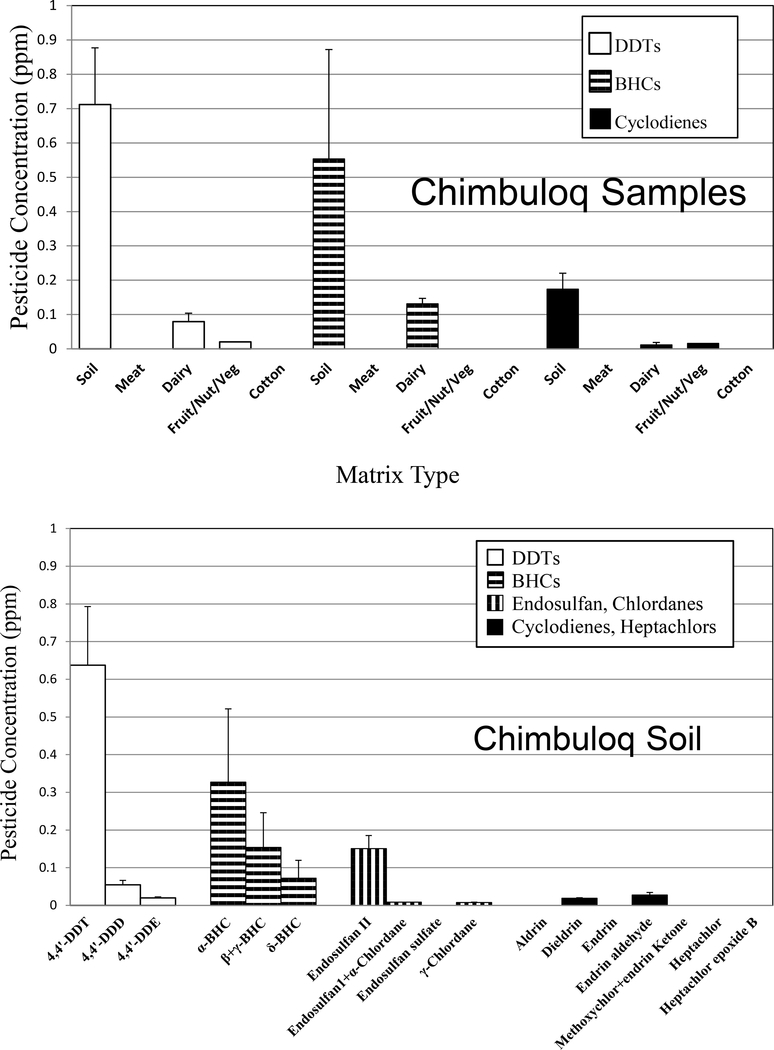

Figure 4.

Pesticide concentrations in samples from the Chimbuloq site (ppm; mean, standard error); no samples for meat and cotton. Top Panel: Concentrations of DDTs (sum of 4,4’-DDT, 4,4’-DDD, 4,4’-DDE isomers), BHCs (sum of α, β, γ, δ lindane isomers), and cyclodienes (sum of aldrin, dieldrin, and chlordane, endrin, endosulfan, and heptachlor isomers) in Chimboloq surface soil and raw food products. Bottom Panel: Concentrations (mg/kg) of individual pesticides in Chimbuloq surface soil samples.

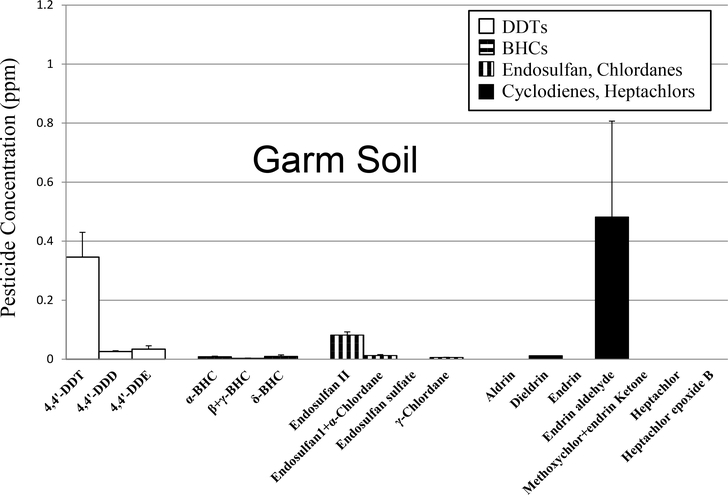

Figure 5.

Pesticide concentrations in surface soil samples from the Garm site (ppm; mean, standard error). No data were available for pesticides in food products.

3.2. Vakhsh

Pesticide concentrations were highly variable spatially in Vakhsh soils (>100 fold), and had no correlation with sample time. 4,4’-DDT was the highest detected pesticide in Vakhsh surface soils, with concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 42 ppm (Fig. 2). High concentrations (>5 ppm) of endosulfan II and BHC isomers were also present in some site soil samples. Samples of meat, dairy, and plant products from villages located 4 to 7 km from the Vakhsh site all had low concentrations of pesticides (<0.2 ppm; Fig. 2).

3.3. Konibodom

The Konibodom burial site contained the highest concentrations of most analytes among the four study areas, including samples containing 199 ppm of 4,4’-DDT, 36 ppm endosulfan II, and 8.8 ppm of BHC isomers (Fig. 3). Pesticide concentrations were highly variable spatially in surface soils (>100 fold), and had no correlation with sample time. Samples of meat, dairy, and plant products from villages located 4 to 11 km from the Konibodom site had generally low concentrations of pesticides, although a few samples contained concentrations greater than 1 ppm of DDT and BHC isomers, and total cyclodienes (Fig. 3).

3.4. Chimbuloq

Concentrations of pesticides in surface soil samples collected from the Chimbuloq site were low compared to the Vakhsh and Konibodom disposal sites. 4,4’-DDT (0.05 to 1.2 ppm) and BHC isomers (0.01 to 2.0 ppm) were the highest detected pesticides in Chimbuloq surface soils (Fig. 4). Samples of meat, dairy, and plant products from Chimbuloq had low concentrations of pesticides (<0.2 ppm).

3.5. Garm

Concentrations of pesticides in surface soil samples collected from the Garm area, near village of Karashar, were low compared to the Vakhsh and Konibodom disposal sites. 4,4’-DDT (0.2 to 0.7 ppm) and endrin aldehyde (0.01 to 2.3 ppm) were the highest detected pesticides in Garm surface soils (Fig. 5). No data were available for pesticides in raw food products from the Garm site because of compromised samples.

4. Discussion

Uncontrolled storage and burial of obsolete organochlorine pesticides in areas of the Republic of Tajikistan has been recognized as an increasing international environmental concern (e.g., UNEP 2007; Sharov et al. 2016). Organochlorine pesticides were never produced in Tajikistan, but western parts of the country were areas of intensive pesticide use and storage to support large scale production of cotton and other crops (e.g., Li et al. 2006). The Vakhsh burial site was established during Soviet times following international recognition of the potential hazards and subsequent restrictions on the use of organochlorine pesticides. The Vakhsh site became an uncontrolled area after the fall of the Soviet Union and civil war in Tajikistan, followed by subsequent local excavations and uncontrolled surface soil releases of formerly buried metal and plastic containers of DDT and multiple other organochlorine pesticides. The Konibodom burial site received uncontrolled burials of organochlorine pesticides formerly used in the Sugd region of northwestern Tajikistan and other agricultural areas. Numerous much smaller local storages have subsequently been identified within the country (UNEP 2007; Juraev 2007).

Despite international concerns over uncontrolled releases and potential for human exposures, there have been only limited assessments of environmental contamination and only a very few published scientific articles on organochlorine pesticide contamination in Tajikistan. Lederman (1993) reported alpha (0.16–3.5 ppb; detections in 19 of 23 samples) and gamma BHC (hexachlorocyclohexane: 0.07–92 ppb; 23/43 samples), 4,4’ DDT (100–110 ppb; 29/43 samples) and 4,4’ DDD (1.4–2.8 ppb; 8/43 samples) in breast milk of humans in the capital city of Dushanbe in 1989. DDE was detected in all 43 milk samples at concentrations of 2.1 to 120 ppb; endosulfan (thiodan) and metaphos were also detected in a limited number of samples (Lederman 1993). Low concentrations of organochlorine pesticides (<0.25 mg/Kg) were observed in 20 surface soil samples collected during 2011 in mountainous areas of Tajikistan, with the highest concentrations at locations closest to agricultural areas (Zhao et al. 2013). Aldrins, chlordanes, BHC and endosulfan compounds were the most predominant organochlorine pesticides in mountain soils, while DDTs and methoxychlor were present at much lower concentrations. Based on compositional analysis, Zhao et al (2013) concluded that these pesticides were derived from atmospheric transport of historically used pesticides. International preliminary site assessments have shown extremely high pesticide levels in damaged excavated containers (barrels, bags; >5,000 ppm) at the Vakhsh and Konibodom burial sites, and low part per million concentrations of DDT and BHC isomers in surface soils within the pesticide burial sites, along with numerous other pesticides at generally lower concentrations (Tauw 2009; Juraev 2007). Sharov et al. (2016) recently reported that contaminated sites in Tajikistan, including the pesticide sites of Vakhsh and Konibodom, may potentially expose an estimated population of 126,000 residents.

The current study represents the first comprehensive assessment of contamination in site soils and local raw foods in proximity to the legacy organochlorine pesticide burial sites of Vakhsh and Konibodam, as well at two local farm areas in the Republic of Tajikistan. The results of this study confirm previous investigations of more limited scope showing high concentrations of several banned obsolete pesticides in the surface soils of the Vakhsh and Konibodom disposal sites, including DDT and BHC isomers and endosulfan II. Our investigation showed ratios of DDE+DDD/DDT were less than 0.2 in soil samples from the Vakhsh and Konibodam burial sites, indicating more recent releases of DDT and possibly slow degradation in the arid environments at these locations. Several cyclodiene pesticides were also present in Konibodom site soils at concentrations greater than 1 ppm including endosulfan II. Pesticide concentrations at Vakhsh and Konibodam were highly variable spatially in site surface soils, with no apparent declines over the four year study. However, the sample collection dates were based on opportunity, and the study was not specifically designed to monitor changes in pesticides over time. Seven of the pesticide analytes in this study were either not detected or detected at only trace levels at all four sites, indicating limited presence at the burial sites consistent with available historical information on use and disposal. Pesticide contamination in raw food products was generally low, indicating minimal transfer from the pesticide sites into local food chains.

All pesticides in this study were tentatively identified using GC/ECD based on comparison to specific retention windows of each analytical standard. Mass spectral or other confirmatory analysis would be needed to positively confirm the identity of each detected analyte, as well as identify resolved peaks of unknown identity. Although only pesticides were measured in the study, PCBs and other major organochlorine contaminants were not apparent in site soils as indicated by the absence of consistent major unidentified peaks in chromatograms. Also, as noted in preliminary site investigation reports, the site locations had no history of PCB or other non-pesticide disposals (Juraev 2007; UNEP 2007; Tauw 2009). Sulfuric acid was used in the clean up of meat and dairy extracts, which can degrade some cyclodiene pesticides (Muccio et al. 1990; Bernal et al. 1992). The reported concentrations were considered reliable because only dilute acid was used and preliminary analysis of spiked samples indicated no selective loss of analytes. Additonally, a major oxidation product of endosulfan is endosulfan sulfate, which was either minor or not detected in any sample (Hao and Xue 2006). Our results were consistent with available information from previous remedial site investigations and available information on pesticide use and burial, and thus were considered reliable and representative of local conditions. For example, earlier preliminary remedial investigations of the Vakhsh and Konibodam sites showed up to 81 mg/Kg of total organochlorine residues with DDT and hexachlorocyclohexane (BHC) isomers as the major pesticides in site surface soils (0.05 to 2 mg/kg), and the presence of endosulfan II, dieldrin and other pesticides at generally lower concentrations (Juraev 2007; Tauv 2009).

5. Conclusions

Significant challenges remain in remediating contaminated sites and mitigating contaminant risks in the former Soviet Union. In the Republic of Tajikistan, the Vakhsh and Konibodom burial sites have been estimated to contain 3000 to 9500 tons of uncontrolled and obsolete organochlorine pesticides (UNEP 2007; Juraev 2007; Tauv 2009). The results of our investigation show heterogeneous contamination in Vakhsh and Konibodom site soils, and relatively limited contamination in raw foods from local villages in proximity to the burial areas. Pesticide contamination in raw food products at all four study sites was generally low, indicating minimal transfer of legacy organochlorine pesticides into local food chains. The primary purpose of the Stockholm Convention on POPs was the protection of human health and environment from persistent organic pollutants (UNEP 2007). Ongoing and future work at in Tajikistan conducted by international organizations in support of the Stockholm Convention include increasing public awareness of pesticide hazards, worker training, pesticide inventory, development and modernization of storage facilities, environmental assessment, and planning and implementation of safe pesticide destruction and site remediation protocols (UNEP 2007).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the memory of Professor Mukhamadcho Kukaniev. This research was funded by the U.S. EPA, U.S. State Department, and International Science and Technology Center. Thanks to Julie Krzywa, Larisa Lee, and Abubakr Ashurova for assistance with data compilation, data analyses, and quality assurance, to Leah Oliver for map preparation, to Mike Marcovich and Marilynn Hoglund for analytical assistance, and to Patrick Russo and Doug Steele for travel and logistical assistance. The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not represent the policies or opinions of the U.S. EPA. This document has been reviewed in accordance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency policy and approved for publication.

References

- Bernal JL, Del Nozal MJ, Jimenez JJ. 1992. Some observations on clean-up procedures using sulphuric acid and florisil. J Chromatog 607:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- Di Muccio A, Santilio A, Dommarco R, Rizzica M, Gambetti L, Ausili A, Vergori F. 1990. Behavior of 23 persistent organochlorine compounds during sulphuric acid clean-up on a solid matrix column. J Chromatog 513:333–337. [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, Xue J. 2006. Multiresidue analysis of 18 organochlorine pesticides in traditional Chinese medicine. J Chromatog Sci 44:518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISTC. 2015. Residues of obsolete chlorinated pesticide contamination in surface soil and raw foods from areas of Tajikistan ISTC T-1892 Final Technical Report. International Science and Technology Center, Moscow, Russia. [Google Scholar]

- Juraev A 2007. Use of pesticides in the Republic of Tajikistan and inventory of POPS-related pesticides. P. 102–110. Proceedings. Obsolete Pesticides in Central and Eastern European, Caucasus and Central Asia Region: Start of Clean up. 9th International HCH and Pesticides Forum for CEECCA Countries September 20–22, 2007 Chisinau, Republic of Moldova. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantzi OI, Alcock RE, Johnston PA, Santillo D, Stringer RL, Thomas GO, Jones KC. 2001. The global distribution of PCBs and organochlorine pesticides in butter. Env Sci Tech 35:1013–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klisenko MA and Kolos M. 1983. Methods for determination of microquantities of pesticides in food, feed and the environment Edited Klisenko MA. USSR Ministry of Agriculture State Commission on Chemical Pest Control, plant Diseases and Weeds. 304 p. Moscow, USSR. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman SA. 1993. Environmental contaminants and their significance for breastfeeding in the central Asian republics. Wellstart International, Washington DC: July 1993. 39 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Loganathan BG, Kannan K. 1994. Global organochlorine contamination trends: an overview. Ambio 23:187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Sharov P, Dowling R, Gogishvili M, Jones B, Caravanos J, McCartor A, Kashdan Z, Fuller R. 2016. The prevalence of toxic hotspots in former Soviet countries. Env Poll 211:346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauw. 2009. Interim report Obsolete Pesticides Technical Study in the Republic of Tajikistan. World Bank project; 100020592 Prepared by Tauw bv, The Netherlands: December 2, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. 2007. National Implementation Plan on Realization of Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Republic of Tajikistan. United Nations Environmental Program, Global Ecological Fund, and Republic of Tajikstan; Dushanbe, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li YF, Zhulidov AV, Robarts RD, Korotova LG, Zhulidov DA, Gurtovaya TYu, Ge LP. 2006. Dichlorodiphenyltrichlorethane usage in the former Soviet Union. Sci Total Env 357:138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Zeng H, Wu J, Zhang L. 2013. Organochlorine pesticide (OCP) residues in mountain soils from Tajikistan. Eviron Sci Process Impacts 15:608–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.