Abstract

Human-dominated land uses can increase transport of major ions in streams due to the combination of human-accelerated weathering and anthropogenic salts. Calcium, magnesium, sodium, alkalinity, and hardness significantly increased in the drinking water supply for Baltimore, Maryland over almost 50 years (p<0.05) coinciding with regional urbanization. Across a nearby land use gradient at the Baltimore Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) site, there were significant increases in concentrations of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and Si and pH with increasing impervious surfaces in 9 streams monitored bi-weekly over a 3–4 year period (p<0.05). Base cations in urban streams were up to 60 times greater than forest and agricultural streams, and elemental ratios suggested road salt and carbonate weathering from impervious surfaces as potential sources. Laboratory weathering experiments with concrete also indicated that impervious surfaces increased pH and DIC with potential to alkalinize urban waters. Ratios of Na+ and Cl− suggested that there was enhanced ion exchange in the watersheds from road salts, which could mobilize other base cations from soils to streams. There were significant relationships between Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and K+ concentrations and Cl−, SO42−, NO3− and DIC across land use (p<0.05), which suggested tight coupling of geochemical cycles. Finally, concentrations of Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and pH significantly increased with distance downstream (p<0.05) along a stream network draining 170 km2 of the Baltimore LTER site contributing to river alkalinization. Our results suggest that urbanization may dramatically increase major ions, ionic strength, and pH over decades from headwaters to coastal zones, which can impact integrity of aquatic life, infrastructure, drinking water, and coastal ocean alkalinization.

Introduction

Human-dominated land use is increasing rapidly on a global level (Foley et al. 2005, Grimm et al. 2008) with major impacts on water quality in streams and rivers across time and space (e.g. Walsh et al. 2005, Lyons and Harmon 2012, Kaushal et al. 2014, Chambers et al.2016). A growing number of studies suggest that dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and base cations can be significantly elevated in streams and rivers draining human-dominated watersheds compared with forested watersheds (e.g., Daniel et al. 2002, Baker et al. 2008, Peters 2009, Barnes and Raymond 2009, Aquilina et al. 2012, Kaushal et al 2013). In addition, DIC and calcium concentrations in streams throughout the Eastern U.S. have shown increasing trends over time (Raymond et al. 2008, Kaushal et al. 2013). These geographic regions include urbanized watersheds, which sometimes drain minimal or no natural carbonate lithology (Kaushal et al. 2013, Kaushal et al. 2015). However, relatively little work has evaluated: (1) long-term changes in concentrations of different base cations in urban watersheds over decadal scales, (2) the effects of land use on multiple weathering products and coupling with acid/base chemistry, and (3) the impacts of urbanization on salinization and alkalinization over spatial scales ranging from small headwater streams to coastal waters. Furthermore, potential sources of DIC and base cations in urban streams are still poorly understood relative to sodium chloride pollution from road salts and nutrient pollution. A more holistic understanding of coupled changes in transport of DIC, base cations, silica, and pH from watersheds across land use has environmental implications relevant to drinking water quality, biodiversity, ecosystem primary production, and the coastal carbon cycle (e.g., Kaushal 2016, Canedo-Arguelles et al. 2016, Clements et al. 2016). Human activities have increased the flux of carbon from land to ocean primarily via rivers by 1 Pg/yr since preindustrial times (Regnier et al. 2013), and carbon fluxes are usually dominated by dissolved inorganic carbon from weathering and anthropogenic inputs (Cole et al. 2007, Stets and Striegl 2012, Kaushal et al. 2013).

Human activities such as urbanization can not only increase transport of DIC but also increase other base cations, and silica in streams (Williams et al. 2005, Peters 2009, Bhatt et al. 2014. Carey and Fulweiler 2012). However, many questions still remain. For example, urbanization increases DIC concentrations, but the sources of DIC are still poorly understood (e.g., Daniel et al. 2002; Baker et al. 2008; Barnes and Raymond 2009, Prasad et al. 2013, Smith and Kaushal 2015). Similarly, base cations and silica concentrations are elevated in urbanized streams compared to forested streams, but abiotic vs. biotic mechanisms are still poorly understood (Williams et al. 2005, Peters 2009, Bhatt et al. 2014). Finally, there are questions regarding whether geochemical cycles can be coupled in urban watersheds due to similarities in sources and transport. Sometimes, land use has the potential to be more important than natural lithology in controlling transport of major ions in urban watersheds, but temporal and spatial trends, sources, and coupling of different geochemical cycles warrant further investigation (Carey and Fulweiler 2012, Bhatt et al. 2014).

There are several abiotic and biotic processes, which can contribute to increased major ions in urban streams compared with forested streams. These potential mechanisms include chemical weathering, road salts, sewage inputs, and decreased biological uptake by vegetation (Baker et al. 2008, Barnes and Raymond 2009, Peters 2009, Carey and Fulweiler 2012, Connor et al. 2014 Kaushal et al. 2015). Disturbance of soils during construction can bring bedrock materials to the surface, where they are available for chemical weathering reactions and alkalinization of water chemistry releasing base cations (Siver et al. 1996). Chemical weathering of carbonate rich urban infrastructure can also be a potential source of DIC, Ca2+, Mg2+, and other major ions to streams and contributes to a distinct urban lithology known as the “urban karst” (sensu Kaushal et al. 2014, Kaushal et al. 2015). The dissolution of the urban karst as a result of urban construction (e.g., bridges, engineered river banks, buildings, drainage infrastructure, and pavement on road and parking lots) can influence salinity, major ions, and alkalinity (Conway 2007; Davies et al. 2010; Kaushal et al. 2014). Carbonates present within urban impervious surfaces such as concrete may be directly dissolved by sulfuric and nitric acids from acidic precipitation and also may be coupled to NO3− and SO42− sources and transport in streams, but these phenomena have been less well explored. Road salts can also be direct sources of base cations and other anions including SO42− in streams. In addition, ion exchange reactions in response to salinization from road salts can also be an important component of chemical weathering in soils and contribute to coupling of release of base cations and anions from exchange sites (Shanley 1994). Alternatively, oxidation of organic matter from wastewater and remineralization of organic matter from algal and terrestrial sources can also provide significant inputs of DIC, Si, K+, and other major ions to streams (Williams et al. 2005, Prasad et al. 2013, Smith and Kaushal 2015, Bhatt et al. 2014). Thus, there is a need to better identify potential sources of major ions in addition to their spatial and temporal patterns in urban watersheds.

Increased concentrations of dissolved inorganic carbon, base cations, and silica in streams have implications for water quality from regional to local scales (Kaushal et al. 2013, Kaushal 2016). For example, DIC transported from minimally disturbed watersheds is mainly derived from chemical weathering of rocks and organic matter oxidation (Berner et al. 1983, Hope et al. 1994). Although some DIC is released to the atmosphere, a considerable fraction of sequestrated CO2 can be stored globally in the form of DIC in fresh and marine waters (Cole et al. 2007). From the perspective of water quality, increased DIC and silica concentrations can enhance eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems (Tobias and Bohlke 2011, Boyd et al. 2016) because they can be rapidly assimilated by algae, particularly in nutrient-rich aquatic ecosystems. Calcium and magnesium further influence water hardness, toxicity of metals, and can impact pH and aquatic life (Boyd et al. 2016). Dissolved salts can corrode piped infrastructure, complicate drinking water treatment, and can decrease drinking water safety (Kaushal et al. 2016). Increased DIC and base cations contribute to increased buffering capacity, and may counteract acidification in freshwater and coastal waters (Johnson et al. 1994, Kaushal et al. 2013, Pfister et al.2014). An improved understanding of changes in concentrations and sources of different major ions in watersheds across land use is currently needed to better inform watershed management across time and space.

Here, we explore how watershed land use can enhance transport of DIC, other major ions (calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium), and silica due to the synergistic effects of: (1) an abundance of materials that can be easily weathered in the built environment (e.g. cement infrastructure); (2) widespread exposure of carbonates in the built environment to acidification in response to precipitation; and (3) road salt inputs and ion exchange, and sewage inputs. In the current paper, we explored the following two hypotheses: (1) urbanization significantly increases concentrations of DIC and major ions (Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Na+, Si) in streams and rivers over time and space and (2) accelerated weathering of impervious surfaces has the potential to increase DIC and pH of urban waters. Firstly, we documented long-term increasing trends in weathering products including alkalinity, hardness, magnesium, and sodium in the drinking water supply of Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Secondly, we analyzed concentrations of weathering products across a land-use gradient to explore drivers of these long-term trends. Thirdly, we analyzed longitudinal concentrations of weathering products and pH from headwaters to coastal waters to better understand downstream impacts. Finally, we investigated the potential for weathering of impervious surfaces to influence water quality in these watersheds using both laboratory experiments and elemental ratios in stream water over 3–4 years of sampling. An improved understanding of the role of land use and weathering of the built environment on stream chemistry is critical for understanding the evolution of urban geochemical and biogeochemical cycles over time scales ranging from days to decades (Kaushal et al. 2014, Kaushal et al. 2015). Ultimately, human-accelerated weathering and road salts should be considered in reducing nonpoint sources of pollution, which can alter major ions, pH, hardness, and alkalinity in receiving waters.

Methods

Study Sites

Drinking Water Supply on the Patapsco River

Long-term chemistry of Baltimore’s drinking water was obtained and analyzed from the Ashburton Treatment Plant in Baltimore, MD, which receives water from Liberty Reservoir on the North Branch of the Patapsco River. Liberty Reservoir drains approximately 42,476 hectares (Koterba et al. 2011). The watershed is located in the Piedmont Plateau Physiographic Province and drains gentle to steep slopes, low hills, and ridges. The underlying lithology is crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks of volcanic origin consisting of schist and gneiss (Maryland Department of Natural Resources 2002). Major land uses are agriculture (43 percent), forest (32 percent), and developed land (22 percent) (Maryland Department of Planning 2000). Long-term data on drinking water chemistry at the Ashburton Treatment Plant spanned from January 1964 to December 2008, and samples were analyzed at a monthly frequency for sodium, calcium, magnesium, alkalinity, and hardness. Detailed methods and QA/QC information regarding Baltimore’s drinking water quality testing program can be found elsewhere (Koterba et al. 2011). Alkalinity and hardness were analyzed using standard methods and base cations were analyzed using atomic absorption spectrophotometry and duplicates and spikes were conducted to ensure precision and accuracy for drinking water (Koterba et al. 2011).

Baltimore Long-Term Ecological Research Site

The Gwynns Falls is the main focal watershed of the Baltimore Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) site. The Gwynns Falls watershed (76°30’, 39°15’) is a tributary of the North Branch of the Patapsco River, and it is located predominantly within the Piedmont physiographic province in Baltimore County and Baltimore City, Maryland. Much previous work has focused on characterizing the hydrology and biogeochemistry of the Gwynns Falls (e.g., Groffman et al. 2004, Kaushal et al. 2005, Kaushal et al. 2008, Shields et al. 2008, Duan et al. 2012). The watershed drains a total area of 17,150 ha and flows to the Northwest Branch of the Patapsco River, which then flows into the Chesapeake Bay. The spatial land use distributions of the study area show a clear rural-urban land use gradient, from forest/low-density-residential in the nearby reference sites, suburban/agricultural in upper Gwynns Falls, to urban in lower Gwynns Falls (Figure 1; Table 1; Supporting Information). Impervious surface cover follows the rural-urban gradient and increases from ~0–0.3% in the reference watershed, ~10–22% in upper subwatersheds to ~26–56% in the lower subwatersheds (Table 1; Supporting Information). There are no point-source discharges (e.g. domestic or industrial waste water) in the study reaches of the Gwynns Falls watershed, but nonpoint source N pollution from aging sanitary infrastructure has been shown to be important (Kaushal et al. 2011).

Figure 1.

Geologic map of the Gwynns Falls watershed showing lithologic gradients and long-term sampling locations of the Baltimore LTER site.

Table 1.

Land use and watershed characteristics for the Baltimore LTER site (based on Groffman et al. 2004, Shields et al. 2008, Kaushal et al. 2008, Newcomer Johnson et al. 2014).

| Land Use (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Station | Code | Context | Drainage Area (ha) | Impervious Surface (%) | Population Density (per ha) | Forested | High Density Residential | Low and Medium Density Residential | Commercial | Agricultural |

| Pond Branch | POBR | Forested | 38 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| McDonogh | MCDN | Forested/Agriculture | 7.8 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 |

| Baisman Run | BARN | Forested/Suburban | 382 | 0.25 | 1 | 71 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 2 |

| Gwynnbrook | GFGB | Suburban | 1065 | 15 | 16.4 | 17 | 5 | 31 | 15 | 8 |

| Villanova | GFVN | Urban | 8349 | 17 | 12.2 | 22 | 2 | 30 | 17 | 8 |

| Glyndon | GFGL | Suburban | 81 | 19 | 9.4 | 19 | 4 | 31 | 15 | 5 |

| Carroll Park | GFCP | Urban | 16378 | 24 | 19.7 | 17 | 5 | 41 | 10 | 6 |

| Dead Run | DRKR | Urban | 1414 | 31 | 12.6 | 5 | 6 | 57 | 3 | 2 |

| Gwynns Run | GRGF | Urban | 557 | 61 | -- | 1.5 | 63 | 0 | 18.5 | 0 |

The geology of the Baltimore LTER site is characterized by gentle to steep rolling topography, low hills and ridges characteristic of the Piedmont Plateau Physiographic Province. Crystalline rocks of igneous or metamorphic origin characterize the surface geology. Precambrian schist and gneiss are in the upper watershed in Baltimore County, and Paleozoic basic/granitic igneous rocks are in the lower watershed in Baltimore City (Figure 1). These changes in surficial geology also follow an increase in impervious surface cover in the upper watershed in Baltimore County to the lower watershed in Baltimore City (Supporting Information). Little to no carbonate rock is found in the study area. These crystalline formations decrease in elevation from northwest to southeast and eventually extend beneath the younger sediments of the Coastal Plain. The Gwynns Falls watershed lies predominantly in the Baile and Lehigh soil series.

Routine Stream Sampling of Major Ions and Weathering Products

The Baltimore Ecosystem Study (BES) LTER project has collected data on weekly water chemistry in the Gwynns Falls and a nearby reference watershed since 1998 (e.g. Groffman et al. 2004; Kaushal et al. 2005; Kaushal et al. 2008; Kaushal et al. 2011; Duan et al. 2012). Samples are collected from 4 longitudinal sites along the main channel of the Gwynns Falls, 2 medium-sized mixed land-use watersheds, and 3 small watersheds with relatively homogeneous land use, including an agricultural reference watershed, MCDN (Table 1). All sites were located in the Gwynns Falls watershed, except Pond Branch, the completely forested reference watershed, and Baisman Run (a mostly forested low-density residential watershed), which were both in the adjacent Gunpowder River watershed. The BES LTER site includes long-term streamflow information for all of the following U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) stream gauges, where data is available online: POBR (USGS 01583570), BARN (USGS 01583580), MCDN (USGS 01589238), DRKR (USGS 01589330), GFGL (USGS 01589180), GFGB (USGS 01589197), GFVN (USGS 01589300), and GFCP (USGS 01589352). Further descriptions of land use and maps with watershed boundaries for the Baltimore LTER site can be found at: http://www.beslter.org/frame4-page_3f_05.html.

Longitudinal Synoptic Stream Sampling of Major Ions and Weathering Products

Synoptic surveys of stream chemistry along the urban watershed continuum of the Gwynns Falls have been described previously (Sivirichi et al. 2011, Kaushal and Belt 2012, Kaushal et al. 2014, Newcomer Johnson et al. 2014). Sites were typically sampled during baseflow conditions. Longitudinal synoptic sampling for base cations occurred during 3 seasons (March 2008, July 2008, and October 2008) to investigate longitudinal variations in concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+. Longitudinal synoptic sampling for DIC and pH occurred during October 2013. The synoptic sampling typically occurred over 1–2 days at baseflow (there were a few storm events) (Kaushal et al. 2014). We sampled synoptic locations along the entire length of the Gwynns Falls watershed from headwaters to outflow. Specific sampling locations of the synoptic sites for the Gwynns Falls watershed were chosen based on tributary junctions and positioning of BES LTER and USGS gauging stations (Kaushal et al. 2014).

Study reaches of the Gwynns Falls watershed were -located near 4 mainstem USGS gauges (GFGL, GFGB, GFVN, GFCP) that are supported as part of the BES LTER project. Water samples were also collected at least 100 m downstream from any tributary confluence along the mainstem of the Gwynns Falls watershed (to increase the likelihood that the stream was well-mixed). Coordinates for all seasonal synoptic sites were recorded using handheld GPS systems. Our synoptic sampling scheme included grab sample collection to measure concentrations of major ions including base cations, pH, and DIC. Real-time discharge data were available at 4 gauging stations along the Gwynns Falls watershed and tributaries. The recession of storm hydrographs from the Gwynns Falls watershed occurs from minutes to days depending upon storm size and watershed position (Shields et al. 2008) and sampling was conducted typically at least 3 days after any rain events.

Weathering of Impervious Surfaces: Laboratory Experiments

In order to further investigate the potential for weathering of impervious surfaces to influence stream chemistry, we performed weathering experiments in the laboratory. Representative concrete samples were collected in urban and suburban areas of Baltimore County, MD and also provided by the Maryland State Highway Administration. We tested potential effects of acidification on DIC and pH at three different pH levels in laboratory experiments. In each individual experiment, water was introduced as a fixed volume (100 mL) to a small piece of concrete material with a roughly cubic shape (mean surface area of 65.8 cm2 from all samples; n=30). All impervious surfaces were completely submerged, indicative of sitting or slowly moving water that has the potential to infiltrate cracks and pore spaces in concrete. Impervious surfaces allow for some infiltration due to cracking from regular wear, freeze-thaw cycles, root growth of vegetation, etc. Rainfall was not mimicked and the water was in the same container for the duration of each experiment. These experiments ranged from 30 seconds to three minutes, after which time the sample material was immediately removed from the water. Selection of shorter time scales in the experimental design was a result of preliminary experiments that confirmed rapid chemical changes during the first 1–5 minutes.

Glass mason jars were acid washed in a 10% HCl solution, rinsed five times with MilliQ water, air dried, and then used for the concrete dissolution experiments. Each jar was then sample rinsed with a small aliquot of stream water prior to dissolution experiments. The stream water used for the experiments was collected in the field 24–48 hours before the lab experiments. The source of the water used in experiments was Pond Branch, our forested reference stream with zero impervious surface coverage (Table 1). Stream water was collected in multiple acid washed 1 liter HDPE bottles and kept on ice in the field. Upon return to the lab, the water was stored at 4°C until used in experiments. Aliquots of the stream water were filtered and analyzed for DIC concentration prior to initiation of the experiments.

Stream water from the minimally disturbed reference watershed (Pond Branch), which was used in all experiments, had a pH of 6.8 or ~7). In addition to ambient conditions (pH = ~7), stream water was also acidified in the lab with nitric acid to pH = 3 and pH = 5, which was based on the study of acid “attack” on concrete by rainfall (Chen et al. 2013) and the long-term mean pH of precipitation in the Baltimore-Washington metropolitan area. The mean pH of precipitation in this region has ranged from 4.4 to 5.0 over the last decade, with a weekly mean average of 4.5 (National Atmospheric Deposition Program; http://nadp.sws.uiuc.edu). pH and DIC were measured throughout the time course of the laboratory experiments to evaluate whether exposure to ambient pH and acidified water had potential to reduce acidity and increase DIC via chemical weathering and neutralization of acids by concrete surfaces. Because a fixed volume of water was used in these small, enclosed experiments over short durations, water was not pipetted out/removed during the leaching process. This procedure would have changed the ratio of water to sample and could have contributed to an inaccurate concentration of DIC. Therefore, separate duplicate experiments were run at each level of acidity and each time step. pH was measured in each experiment at 15–30 second intervals throughout the leaching processes. Overall, these data allowed us to plot a DIC and pH “path” using each of the individual leaching experiments over time.

Water Chemistry Analyses

Base cation samples (collected in HDPE Nalgene bottles) were left unfiltered, acidified with concentrated HNO3 to a pH of 2.0, and stored at room temperature until analysis. Analysis of base cations was performed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry at USEPA, Ground Water and Ecosystem Restoration Division and using ICP-OES at the University of Maryland following methods in Sivirichi et al. (2011). Cl− and SO42− were measured by ion chromatography (Groffman 2016). DIC was analyzed on a Shimadzu 5000 TOC-L (total organic carbon) analyzer. SiO2 was measured colorimetrically using the molybdate blue method on a Lachat autoanalyzer. Precision and accuracy of measurements of base cations, DIC, and SiO2 were evaluated in the laboratory by duplicates and spikes with commercial standards.

Percent difference between duplicates was typically < 5% and spike recovery was within 10% of expected concentrations. pH measurements were made with a multipurpose, all-weather meter made by Hanna Instruments. Calibration of the pH meter was performed using a traditional three-point method with buffering solutions of pH 4.0, 7.0, and 10.0. Instrument sensors were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water and dried between measurements.

Results

Increased Concentrations of Major Ions and DIC with Watershed Urbanization

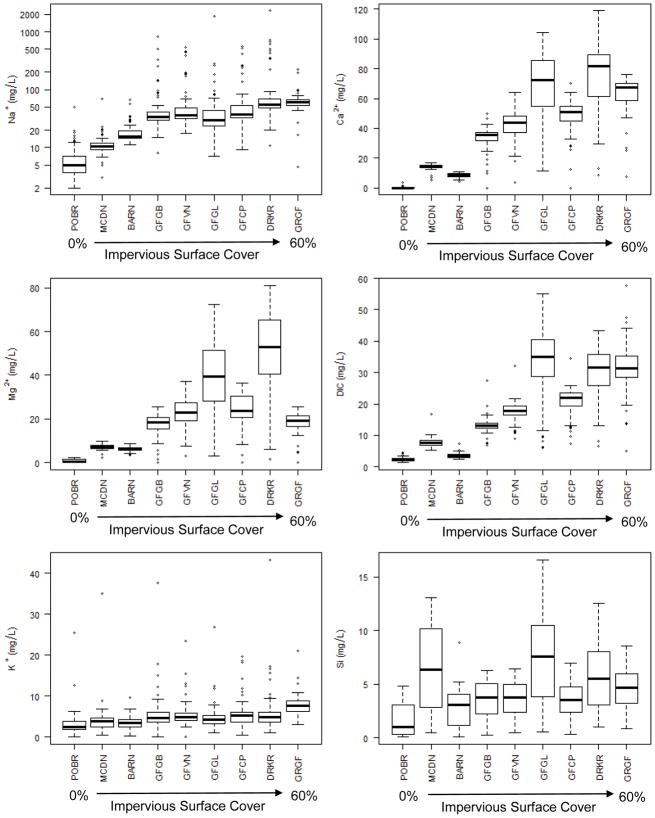

There were significant increasing long-term trends in major ions and alkalinity in the drinking water supply of Baltimore, Maryland over almost 50 years (p<0.05) (Figure 2). These increasing drinking water chemistry trends coincide with long-term urbanization in the Baltimore metropolitan area (Kaushal et al. 2005, Kaushal et al. 2014, Kaushal et al. 2015). There were also distinct temporal patterns in stream chemistry over annual cycles in smaller watersheds of the Baltimore LTER site across a well-defined land use gradient (Figure 3). For example, concentrations of sodium showed sharp peaks during winter months coinciding with road salt inputs and sodium remained elevated throughout all seasons in urbanized watersheds (Figure 3). Although there was temporal variability, concentrations of sodium, calcium, magnesium, potassium, silica, and DIC typically increased with watershed impervious surface cover across land use (Figure 4, Tables 2–3). At the most urban sites, mean concentrations of DIC, sulfate, sodium, calcium, and magnesium were respectively 16, 23, 22, 243, and 67 times greater than the forest site (Table 2). Silica and potassium in urban and agricultural streams showed modestly increased concentrations up to 2–4 times than the forested reference site (Table 2). There were significant positive linear relationships between impervious surface cover and median concentrations of DIC, sulfate, pH, silica, sodium, calcium, and potassium (p<0.05) (Figure 5, Table 3).

Figure 2.

Long-term trends in drinking water chemistry from Baltimore, Maryland, USA (data courtesy of Bill Stack and Baltimore Department of Public Works.

Figure 3.

Concentrations of sodium in streams draining a land use gradient at the Baltimore LTER site over time.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of major ions in streams draining a land use gradient at the Baltimore LTER site. The center vertical lines of the box and whisker plots indicate the median of the sample. The length of each whisker shows the range within which the central 50 % of the values fall. Box edges indicate the rst and third quartiles. Open circles represent outside values.

Table 2.

Mean concentrations of major ions in streams across land use for the Baltimore LTER site.

| Code | DIC | H+ | SO4 | Si | Na+ | Ca2+ | K+ | Mg2+ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | |

| POBR | 2.39 ± 0.06 | 87 | 4.11E-07 ± 3.51E-08 | 106 | 1.47 ± 0.06 | 111 | 1.67 ± 0.16 | 88 | 6.95 ± 0.84 | 65 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 65 | 3.25 ± 0.42 | 65 | 0.76 ± 0.10 | 65 |

| MCDN | 7.72 ± 0.16 | 78 | 2.18E-07 ± 1.40E-08 | 97 | 14.09 ± 0.18 | 100 | 6.57 ± 0.43 | 75 | 12.07 ± 1.08 | 61 | 14.06 ± 0.25 | 61 | 4.32 ± 0.55 | 61 | 7.06 ± 0.14 | 61 |

| BARN | 3.58 ± 0.08 | 89 | 1.22E-07 ± 7.85E-09 | 107 | 3.29 ± 0.22 | 111 | 2.76 ± 0.19 | 87 | 19.05 ±1.22 | 63 | 8.53 ± 0.16 | 63 | 3.55 ± 0.20 | 63 | 6.26 ± 0.13 | 63 |

| GFGB | 13.17 ± 0.24 | 101 | 6.44E-08 ± 3.19E-09 | 109 | 7.26 ± 0.28 | 112 | 3.63 ± 0.17 | 100 | 66.19 ± 14.87 | 66 | 33.51 ± 1.01 | 66 | 5.80 ± 0.60 | 66 | 17.38 ± 0.64 | 66 |

| GFVN | 17.52 ± 0.32 | 94 | 2.79E-08 ± 1.77E-09 | 109 | 11.33 ± 0.47 | 113 | 3.62 ± 0.16 | 94 | 71.79 ± 13.14 | 66 | 41.51 ± 1.29 | 66 | 5.56 ± 0.41 | 66 | 22.71 ± 0.86 | 66 |

| GFGL | 33.48 ± 1.08 | 98 | 3.31E-08 ± 2.71E-09 | 109 | 23.83 ± 0.70 | 113 | 7.37 ± 0.40 | 95 | 75.12 ± 29.02 | 63 | 69.43 ± 2.67 | 63 | 4.82 ± 0.45 | 63 | 39.90 ± 2.09 | 63 |

| GFCP | 20.99 ± 0.41 | 96 | 2.23E-08 ± 1.43E-09 | 109 | 17.96 ± 0.49 | 113 | 3.56 ± 0.18 | 96 | 80.18 ± 15.08 | 65 | 48.12 ± 1.47 | 65 | 5.85 ± 0.46 | 65 | 23.81 ± 0.94 | 65 |

| DRKR | 30.16 ± 0.79 | 95 | 2.26E-08 ± 1.61E-09 | 110 | 26.45 ± 1.00 | 112 | 5.78 ± 0.32 | 96 | 158.07 ± 40.30 | 65 | 73.40 ± 2.80 | 65 | 6.20 ± 0.71 | 65 | 50.45 ± 2.32 | 65 |

| GRGF | 31.70 ± 0.86 | 77 | 2.89E-08 ± 2.11E-09 | 104 | 33.75 ± 0.85 | 107 | 4.54 ± 0.19 | 90 | 64.47 ± 4.50 | 54 | 62.56 ± 1.77 | 54 | 7.92 ± 0.39 | 54 | 18.35 ± 0.69 | 54 |

Table 3.

Linear regressions between median concentrations and impervious surface cover for streams at the Baltimore LTER site.

| R2 | Slope | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIC | 0.59 | 0.5 | <0.05 |

| pH | 0.52 | 0.02 | <0.05 |

| Si | 0.05 | 0.02 | <0.05 |

| Na+ | 0.86 | 0.91 | <0.05 |

| Ca2+ | 0.58 | 1.16 | <0.05 |

| K+ | 0.89 | 0.07 | <0.05 |

| Mg2+ | 0.22 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

Figure 5.

Examples of relationships between median concentrations of major ions and impervious surface cover in streams draining a land use gradient at the Baltimore LTER site over time. R2 values for statistically significant relationships are: impervious surface cover vs. median concentrations of Na+ (0.86), Ca2+ (0.58), K+ (0.89), DIC (0.59), and pH (0.52).

There were consistent increases in DIC concentrations from forest, agricultural to suburban/urban sites. Natural lithology doesn’t explain the sources of the DIC increases; because we observed increases in DIC with urbanization independent of natural lithologic gradients at the Baltimore LTER site (e.g. from watersheds draining metamorphic rocks to watersheds draining igneous rocks – there is no natural carbonate lithology draining the Baltimore LTER sites (Figure 1). Instead, there was additional DIC transport in these urban watersheds from anthropogenic sources. Si and K+ also increased with urbanization and impervious surface cover in watersheds from forested to forest, agricultural to suburban/urban sites (Figure 3). However, the pattern of increase in Si and K+ was not as strong as DIC which may have been due to biological uptake in soils or streams. The highest concentrations of Si were in the smallest suburban and agricultural streams where stream size may have played a role (Table 2).

Relationships between Base Cations and Anions

There were significant relationships between concentrations of base cations and anions in streams across land use. Elemental ratios in stream water suggested that road salts and carbonate weathering from impervious surfaces were potential sources. Chloride showed significant relationships with sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium in streams across land use (p<0.05) (Figure 6). As urbanization increased, there was a shift towards a 1:1 ratio of Na:Cl in streams with less variability in Na:Cl ratios (Figure 7). However, Na:Cl was typically less than 1 at the most urban sites, suggesting greater mobility of chloride ions relative to sodium ions (Figure 7). Sulfate was strongly related to sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium in streams across land use (p<0.05) (Figure 6). DIC was related to sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium in streams across land use (p<0.05) (Figure 6). Ca2+ + Mg2+ vs. DIC showed significant relationships in streams across land use and shifted in values with increasing urbanization suggesting the potential importance of carbonate weathering in watersheds with no natural sources of carbonates (Figure 7). Some sites showed a deviation in Ca2+ + Mg2+ vs. DIC away from the linear relationship, which potentially suggested sewage inputs or road salts, in addition to carbonate weathering. Interestingly, Na+ + K+ vs. Si also showed no clear relationship with highly elevated Na+ + K+ concentrations relative to Si at urban sites, which suggested road salt and sewage could be more important inputs than silicate weathering (Supporting Information). Nitrate concentrations were related to base cation concentrations at some urban sites (p<0.05) potentially due to similar sources, similar modes of watershed transport, and/or coupled geochemical cycles (Figure 8).

Figure 6.

Relationships between base cations and anions in streams draining a land use gradient at the Baltimore LTER site. R2 values for all statistically significant relationships are: Na+ vs. Cl− (0.97), DIC (0.08), SO42− (0.17); Ca2+ vs. Cl− (0.24), DIC (0.63), SO42− (0.83); Mg2+ vs. Cl− (0.17), DIC (0.52), SO42− (0.78); K+ vs. Cl− (0.54), DIC (0.03), and SO42− (0.12).

Figure 7.

Relationships between elemental ratios in streams draining a land use gradient at the Baltimore LTER site. Line represents 1:1 relationship for Na:Cl.

Figure 8.

Examples of relationships between base cations and nitrate concentrations in some urban streams at the Baltimore LTER site. R2 values for relationships at the DRKR site are: nitrate vs. Ca2+ (0.46), Mg2+ (0.57). R2 values for relationships at the GFCP site are: nitrate vs. Ca2+ (0.68), Mg2+ (0.49). R2 values for relationships at the GFGB site are: nitrate vs. Ca2+ (0.70), Mg2+ (0.80).

Potential Impacts of Weathering of Impervious Surfaces: Laboratory Experiments

In all laboratory experiments, a strong and consistent increase was measured in pH and DIC among all concrete samples subjected to experimental weathering, regardless of manipulation of initial pH (Figure 9). pH and DIC increased incrementally over time for each level of acidification. Incremental elevation in DIC concentrations in lab experiments was tempered slightly at the higher levels of acidification, likely due to some outgassing of CO2 in response to acidification (Figure 9). Increases in DIC in laboratory experiments across all pH levels were likely due to carbonate weathering in the concrete and aggregate material. As expected, pH also consistently increased along with DIC during experiments, which suggested weathering of carbonates and neutralization of acid over shorter time scales (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Changes in pH and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in acidification experiments with concrete samples. DIC values at time zero are concentrations in ambient stream water at Pond Branch (a forest reference stream with no impervious surface cover) prior to any introduction of the concrete samples or experimental acidification. Solutions were then manipulated in the lab to produce different acidity levels: pH ~3 (upper panel), pH ~4.5 (middle panel) and pH ~7 (lower panel).

Longitudinal Patterns in Major Ions along the Urban Watershed Continuum

Longitudinally, concentrations of Ca2+, and Mg2+ significantly increased from the suburban headwaters to the urban outflow of the Gwynns Falls across the entire stream network (p<0.05) (Figure 10). Longitudinally, DIC concentrations generally increased with distance downstream but were more variable at a few headwater sites, and there was no significant trend over the entire stream network. However, there was a significant relationship between DIC and distance downstream when the first 2 headwater sites were removed as outliers. There was a significant linear relationship between pH and distance downstream for the entire stream network (P < 0.05) (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Longitudinal patterns in concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ from individual grab samples significantly increased from the headwaters to the outflow of the Gwynns Falls at the Baltimore Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) site (p<0.05). R2 values for statistically significant relationships were: distance downstream vs. Ca2+ (0.56) and Mg2+ (0.16). DIC concentrations generally increased with distance downstream but were variable at a few headwater sites, and there were no significant relationships. However, there was a statistically significant relationship between DIC and distance downstream with the first 2 headwater sites removed (p<0.05), and the R2 was 0.67. There was a significant linear increase in pH with distance downstream over the entire stream network (p<0.05) and the R2 for distance downstream vs. pH was 0.56.

Discussion

Our results suggest that road salts and human-accelerated weathering have contributed to salinization and alkalinization of fresh water in urban regions over almost half a century extending from headwaters to coastal zones in our study. In natural geologic settings, concentrations of base cations, silica, DIC, and pH can be temporally and spatially heterogeneous in streams due to changes in the weathering rates of local bedrock and overlying regolith (Meybeck 1987, Thornton et al. 1998, Calmels et al. 2011). However, our results show that the built environment contributes to a distinct urban lithology, an urban karst (Kaushal and Belt 2012, Kaushal et al. 2014), which is dominated by carbonate weathering from impervious surfaces and road salts across time and space. Furthermore, our results show that there can be an accumulation of weathering products and elevated pH along stream networks contributing to downstream river alkalinization. Our observations of tight relationships between base cations and anions (including nitrate and silicate) suggest that human-accelerated weathering, ion exchange, and anthropogenic sources may have potential to contribute to coastal eutrophication. Below, we discuss our results regarding temporal and spatial trends in salinization, major ions, and alkalinization of urban waters and implications.

Elevated Concentrations of Major Ions in Streams across Land use

We observed increasing concentrations of DIC and major ions among 9 streams with increasing urbanization across a land use gradient. We also observed long-term increases in alkalinity, hardness, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+ in the Patapsco River with increasing watershed urbanization over nearly a 50-year time period. Urbanization can increase concentrations of DIC, alkalinity, and other major ions (Whitmore et al. 2006, Zampella et al. 2007, Barnes and Raymond 2009, Kaushal et al. 2015). Alkalinity and major ion concentrations in fresh water can increase over time with urbanization and population growth (Stoddard 1991, Whitmore et al. 2006). DIC concentrations are typically greater in highly urbanized catchments, particularly those covered with carbonate bedrock (Baker et al. 2008). Similarly, Si concentrations increase in urbanized streams due to erosion, weathering, and other biological sources (Carey and Fulweiler 2012). Increased Si concentrations in urban streams have been specifically attributed to accelerated weathering of silicate minerals in response to elevated temperatures, sewage inputs, and/or increased biological remineralization of Si in organic matter (Carey and Fulweiler 2012). Furthermore, construction of roads and homes results in the removal of organic rich forest soils (Siver et al. 1996) and increased exposure to cement and concrete surfaces. Interactions between acidic precipitation and concrete surfaces can accelerate weathering of major ions and further contribute to alkalinization of fresh water (Conway et al. 2007, Davies et al. 2010, Connor et al. 2014, Kaushal et al. 2014, Kaushal et al. 2015). Road salt inputs can contribute directly to increases in Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ concentrations in freshwater (Kaushal et al. 2005, Kaushal 2016). Road salt effects may be chronic, occurring even when salts are no longer applied to road surfaces because ground water can serve as a reservoir for saline water, feeding surface waters throughout the year (Cooper et al. 2014). Road salt also influences mobilization of Ca2+ and Mg2+ from soils to streams by increasing cation exchange (Shanley et al. 1999, Daly et al. 2009, Cooper et al. 2014). In addition to road salt, liming of lawns, home gardens, etc. can also increase base cation concentrations and alkalinization of fresh water (Whitmore et al. 2006). Furthermore, sewage leaks impact many of our urban study sites (Kaushal et al. 2011, Kaushal et al. 2014) and can be an additional source of base cations and silica in urban streams (Williams et al. 2005, Bhatt et al. 2014). Finally, mineralization of labile organic matter from terrestrial and algal sources may also influence DIC, Si, and K+ and other bioreactive ions (Barnes and Raymond 2009, Prasad et al. 2013, Kaushal et al. 2014, Smith and Kaushal 2015). Overall, there are multiple synergistic geochemical and biogeochemical processes contributing to the salinization and alkalinization of urban waters, but potential sources can be further explored by a combination of elemental ratios and laboratory experiments.

Relationships between Anions and Base Cations

We found strong relationships between base cations and anions in streams across land use, which suggests similar sources and/or transport. Other work has also found tight correlations among base cations and chloride in urban watersheds, which has largely been attributed to sewage inputs (Bhatt and McDowell 2007). Anthropogenically enhanced inputs of base cations from sewage to rivers can lead to large overestimates of actual weathering rates inferred solely by measuring fluxes of apparent weathering products in streams (Bhatt et al. 2014). In our present study, combined lines of evidence (elemental ratios in stream water and laboratory experiments) suggested that weathering was an important source of major ions at our study sites. For example, there were strong relationships between base cations and DIC in streams across land use. We observed a strong relationship between Ca2+ + Mg2+ vs. HCO3− for most sites, which suggested the importance of carbonate weathering (consistent with our concrete weathering experiments). However, there were considerable deviations in this relationship for some urban sites, which also suggested probable inputs of sewage and road salts.

Road salts were likely another source of major ions and showed strong winter peaks in sodium concentrations across land use. In particular, sodium and chloride showed a strong linear relationship in urban watersheds, which suggested road salts (halite) as a source. In contrast, higher concentrations of Na+ relative to Cl− at our forested site indicated that weathering of silicate minerals was a dominant source in the absence of urbanization. As urbanization increased, there was a shift in Na:Cl ratio towards 1:1 due to inputs from road salts (primarily halite). There were no clear relationships between Na+ + K+ vs. Si and elevated Na+ at urban sites, which also suggested the importance of road salts over silicate weathering in highly urban watersheds. Interestingly, the Na:Cl ratios at the urban sites were <1, which was likely due to retardation of sodium in soils and cation exchange. Given that Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, and Na+ were all strongly related to Cl−, ion exchange due to road salts may be important in the transport of base cations to urban streams. There were also strong relationships between base cations and SO42− in streams across land use, further suggesting the importance of road salts and/or weathering of construction materials. Dissolution of gypsum and dolomite in impervious surfaces and building materials along with other chemical constituents in road salts could potentially explain the relationship between base cations and SO42−.

A Distinct Urban Lithology Now Includes Impervious Surfaces

Our results from both elemental ratios in streams and laboratory concrete weathering experiments indicated that impervious surfaces are a significant factor influencing the salinization and alkalinization of urban waters. For example, concrete materials used in roadways and drainage systems can provide an artificial source of calcium and bicarbonate (Davies et al. 2010, Connor et al. 2014, Kaushal et al. 2014, Kaushal et al. 2015), which could lead to increased concentrations as those we observed in urban streams in this study. Typically, concrete is composed of cement filler, water, and an aggregate material of crushed rock and sand (Domone et al. 2007, Lothenbach et al. 2008). Similar to our laboratory weathering experiments, concrete can experience weathering of minerals dependent upon on acidity and other environmental factors such as temperature, salinity, and external loading from traffic and rates of infiltration of surface water (Domone et al. 2007, Cui et al. 2014). Minerals in impervious surfaces derived from geologic sources (quartz, feldspar, mica and carbonates) are prone to the same weathering processes experienced by natural lithology (Domone et al. 2007, Lothenbach et al. 2008, Cui et al. 2014), which could explain our observation of elevated concentrations of base cations in urban streams in this study.

Our experimental results clearly showed that interactions between acidic water and impervious surfaces consistently increased pH (neutralization and reduction of hydrogen ions) and DIC concentrations. In urban environments, acidic precipitation from fossil fuel combustion may accelerate: (1) weathering of carbonate minerals by acidic rain or other strong acids; (2) weathering of silicate and carbonate minerals by carbonic acid produced from the dissolution of anthropogenically enhanced CO2 (and/or natural biogenic soil CO2) by infiltrating water. Acidification accelerates weathering of anthropogenic impervious surfaces through the production of DIC via neutralization of acidity by carbonate weathering. Results from our laboratory weathering experiments confirmed that elevated concentrations of DIC and pH in urban streams can be produced by acidification reactions with carbonates in impervious surfaces. The types and distributions of impervious surfaces within urban watersheds may have significant impacts on “hot spots” of urban weathering. Furthermore, atmospheric deposition of anions can be concentrated near roadways and contribute to accelerated weathering (Bettez et al. 2013, Rao et al. 2014). We observed relationships between anions and base cations suggesting that nitric and sulfuric acids from urban air pollution can contribute to accelerated weathering. Further work is necessary to track the sources of increased bicarbonate and major ions in urban streams and quantify the proportion of major ions derived from weathering of impervious surfaces vs. road salts and to assess the contribution of nitric, sulfuric, and carbonic acids to urban weathering rates.

Longitudinal Patterns in Weathering Products from Headwaters to Coastal Waters

We observed significant longitudinal patterns in salinization, major ions, and alkalinization along the stream network, which reflect changes in sources, weathering, and transformations. For example, calcium, magnesium, DIC and pH increased from headwaters to larger order streams. Previous work has also shown progressive increases in base cations and other major ions in urban watersheds in Asia where distance downstream was a strong predictor of major ion concentrations (Bhatt and McDowell 2007). Similar to results from our study, coupled patterns in major ions along urban stream networks could have been due to increases in similar anthropogenic sources of salts downstream in response to urbanization due to impervious surfaces (e.g., Na), sewage inputs, and/or weathering of infrastructure (Bhatt and McDowell 2007). Similarities in modes of transport of major ions could also be an explanation for longitudinal trends in this study. Hydrologic pathways along urban drainage networks are dramatically altered by extensive storm drains and leaky pipes, which can rival the extent of natural streams and rivers (Kaushal and Belt 2012, Kaushal et al. 2014). These engineered hydrologic pathways and exchanges of water and chemicals extend into subsurface ground water and leaky piped infrastructure (Garcia-Fresca and Sharp 2005, Hibbs and Sharp 2012, Cooper et al. 2014). Some of the drainage structures of the urban watershed continuum are made of easily weathered materials including concrete and terra cotta piping that further contribute to alkaline and saline runoff (Conway et al. 2007, Davies et al. 2010). In addition, these drainage structures enhance efficient transport of road salt and weathering products from impervious surfaces, soils, agricultural fields, lawns, drainage pipes, etc. directly to streams (Elmore and Kaushal 2008, Kaushal et al. 2014).

Freshwater Alkalinization: Coupling Weathering and Biogeochemical Processes

Although carbonate weathering of impervious surfaces and road salts play a dominant role in influencing major ion concentrations in urban watersheds, there are still other biogeochemical mechanism to consider. Some of our urban streams did not show a significant relationship between DIC and Ca2+ and Mg2+, and had elevated DIC concentrations relative to other urban sites. Elevated DIC relative to Ca2+ and Mg2+ may suggest additional biogeochemical processes that increase alkalinity and DIC in response to urbanization (Tobias and Bohlke 2011, Prasad et al. 2013, Smith and Kaushal 2015). For example, mineralization of organic carbon associated with sewage inputs in urban streams and rivers can increase DIC concentrations potentially explaining some of our observations (Daniel et al. 2002, Baker 2008, Barnes and Raymond 2009, Prasad et al. 2013). Previous work at our study sites demonstrated the influence of sewage leaks on carbon and nitrogen transport in streams (Kaushal et al. 2011, Kaushal et al. 2014). In the present study, we also observed strong relationships with nitrate and base cations, which suggests similar sewage and/or groundwater sources (Bhatt and McDowell 2007). There can also be anaerobic microbial processes in sediments, which can further increase DIC concentrations (i.e., sulfate and iron reduction, denitrification) (Chen and Wang 1999). Overall, the complicated interplay between anthropogenic inputs, weathering, and biogeochemical generation of DIC in human-dominated watersheds warrants further research (Dubois et al. 2010, Tobias and Bohlke 2011, Smith and Kaushal 2015).

There may also be additional biogeochemical controls on nitrate, potassium, and silica cycles in urban streams. The strong relationships between nitrate and base cations at some of our urban sites further suggests the coupling of weathering and urban biogeochemical cycles. Weathering due to acidification from microbial nitrification in streams may have contributed to elevated base cations given strong relationships between nitrate and base cations. Previous work has shown relationships between nitrogen and base cations in human-dominated watersheds due to accelerated weathering from nitric acid (Aquilina et al. 2012). Other work has shown that road salts can mobilize nitrogen from soils via ion exchange and stimulate nitrification (Green et al. 2008, Duan and Kaushal 2015), which may have also contributed to our observations of relationships between nitrate and base cations in this study. Finally, we found that potassium and silica concentrations showed considerably smaller increases in response to urbanization compared to other major ions such as sodium, calcium, and magnesium. Potassium and silica are strongly influenced by biological uptake in watersheds and can be regenerated from organic matter decomposition in addition to mineral weathering (Tripler et al. 2006). Such biogeochemical coupling warrants further study.

Conclusions

Our results suggested that urbanization can increase transport of major ions in streams due to the combination of human-accelerated weathering and anthropogenic salts over almost 5 decades of time extending from headwater to coastal zones. We observed considerable increases in concentrations of many major ions such as DIC, Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, SO42−, and Si and increased pH with increasing impervious surfaces in streams across land use. Interestingly, some of the increasing trends in DIC and major ions across space and time could not simply be accounted for by natural, lithological carbonate sources. Elemental ratios in stream water suggested that road salts and carbonate weathering from impervious surfaces were major sources of ions in urbanized streams. Laboratory weathering experiments with concrete confirmed that impervious surfaces could increase pH and DIC, which complemented our interpretations from elemental ratios in streams. Ratios of Na+ and Cl− < 1 in urban watersheds indicated that there could be enhanced ion exchange due to road salts, which could potentially explain why base cation concentrations showed similar dynamics and relationships to anions in urban watersheds. There were significant relationships between Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and K+ concentrations and Cl−, SO42−, NO3− and DIC across land use, which suggested tight coupling of geochemical cycles hypothetically due to: (1) reactions between weathering agents (anions) and weathering substrates (base cations), (2) synergistic effects of ion exchange on mobilization of base cations and anions from soils to streams due to road salts, and (3) nonpoint sources such as sewage inputs from leaky sanitary infrastructure near streams. Finally, concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, DIC, and pH simultaneously increased with distance downstream contributing to river alkalinization. Our results suggest that urbanization may increase major ions, ionic strength, and pH over decades from headwaters to coastal zones, which can impact integrity of aquatic life, infrastructure, drinking water, and coastal ocean alkalinization. Given increasing urbanization globally, the downstream impacts on water quality from human-accelerated weathering, road salt use, and sewage inputs warrant further consideration, quantification, and management.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Figure 1. Impervious cover for the Gwynns Falls watershed.

Supporting Figure 2. Sodium plus potassium vs. silica in stream water for streams across a land use gradient at the Baltimore LTER site.

Supporting Figure 3. Hydrographs for subwatersheds along the Gwynns Falls during the study period.

Highlights.

Base cations increased in drinking water over ~50 years coinciding with urbanization.

DIC, cations, Si, SO42− and pH in streams increased with impervious surface cover.

Road salts and weathering of impervious surfaces were major sources of ions.

Base cations and pH contributed to alkalinization from headwaters to coastal waters.

Increased ions impact drinking water, infrastructure, and coastal alkalinization.

Acknowledgments

Peter Groffman and Dan Dillon provided important logistical support related to collection and analysis of samples from the Baltimore LTER site. Ashley Sides Raley and Melissa Grese assisted with collection and analysis of synoptic data. Eric Dougherty and Maryland State Highways provided impervious surfaces for laboratory experiments. Peter Groffman provided data on anions in the present study. Significant funding for collection of these data and other data in this paper was provided by the National Science Foundation Long-Term Ecological Research program (NSF DEB-0423476 and DEB-1027188), and NSF DBI 0640300, NSF CBET 1058502, NSF Coastal SEES 1426844, and NSF EAR 1521224. The research has been subjected to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency review but does not necessarily reflect the views of any of the funding agencies, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

References

- Aquilina L, Poszwa A, Walter C, Vergnaud V, Pierson-Wickmann AC, Ruiz L. Long-Term Effects of High Nitrogen Loads on Cation and Carbon Riverine Export in Agricultural Catchments. Environmental Science & Technology. 2012;46(17):9447–9455. doi: 10.1021/es301715t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A, Cumberland S, Hudson N. Dissolved and total organic and inorganic carbon in some British rivers. Area. 2008;40(1):117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RT, Raymond PA. The contribution of agricultural and urban activities to inorganic carbon fluxes within temperate watersheds. Chemical Geology. 2009;266(3–4):318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA, Lasaga AC, Garrels RM. The carbonate-silicate geochemical cycle and its effect on atmospheric carbon-dioxide over the past 100 million years. American Journal of Science. 1983;283(7):641–683. doi: 10.2475/ajs.284.10.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettez ND, Marino R, Howarth RW, Davidson EA. Roads as nitrogen deposition hot spots. Biogeochemistry. 2013;114(1–3):149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt MP, McDowell WH. Evolution of chemistry along the Bagmati drainage network in Kathmandu valley. Water Air and Soil Pollution. 2007;185(1–4):165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt MP, McDowell WH, Gardner KH, Hartmann J. Chemistry of the heavily urbanized Bagmati River system in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal: export of organic matter, nutrients, major ions, silica, and metals. Environmental Earth Sciences. 2014;71(2):911–922. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CE, Tucker CS, Somridhivej B. Alkalinity and Hard ness: Critical but Elusive Concepts in Aquaculture. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society. 2016;47(1):6–41. [Google Scholar]

- Calmels D, Galy A, Hovius N, Bickle M, West AJ, Chen MC, Chapman H. Contribution of deep groundwater to the weathering budget in a rapidly eroding mountain belt, Taiwan. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2011;303(1–2):48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Canedo-Arguelles M, Hawkins CP, Kefford BJ, Schafer RB, Dyack BJ, Brucet S, Buchwalter D, Dunlop J, Fror O, Lazorchak J, Coring E, Fernandez HR, Goodfellow W, Achem ALG, Hatfield-Dodds S, Karimov BK, Mensah P, Olson JR, Piscart C, Prat N, Ponsa S, Schulz CJ, Timpano AJ. Saving freshwater from salts. Science. 2016;351(6276):914–916. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey JC, Fulweiler RW. Human activities directly alter watershed dissolved silica fluxes. Biogeochemistry. 2012;111(1–3):125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CTA, Wang SL. Carbon, alkalinity and nutrient budgets on the East China Sea continental shelf. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans. 1999;104(C9):20675–20686. [Google Scholar]

- Chen MC, Wang K, Xie L. Deterioration mechanism of cementitious materials under acid rain attack. Engineering Failure Analysis. 2013;27:272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Clements WH, Kotalik C. Effects of major ions on natural benthic communities: an experimental assessment of the US Environmental Protection Agency aquatic life benchmark for conductivity. Freshwater Science. 2016;35(1):126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Cole JJ, Prairie YT, Caraco NF, McDowell WH, Tranvik LJ, Striegl RG, Duarte CM, Kortelainen P, Downing JA, Middelburg JJ, Melack J. Plumbing the global carbon cycle: Integrating inland waters into the terrestrial carbon budget. Ecosystems. 2007;10(1):171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Connor NP, Sarraino S, Frantz DE, Bushaw-Newton K, MacAvoy SE. Geochemical characteristics of an urban river: Influences of an anthropogenic landscape. Applied Geochemistry. 2014;47:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Conway TM. Impervious surface as an indicator of pH and specific conductance in the urbanizing coastal zone of New Jersey, USA. Journal of Environmental Management. 2007;85(2):308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CA, Mayer PM, Faulkner BR. Effects of road salts on groundwater and surface water dynamics of sodium and chloride in an urban restored stream. Biogeochemistry. 2014;121:149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Corsi SR, Graczyk DJ, Geis SW, Booth NL, Richards KD. A Fresh Look at Road Salt: Aquatic Toxicity and Water-Quality Impacts on Local, Regional, and National Scales. Environmental Science & Technology. 2010;44(19):7376–7382. doi: 10.1021/es101333u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui S, Blackman BRK, Kinloch AJ, Taylor AC. Durability of asphalt mixtures: Effect of aggregate type and adhesion promoters. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives. 2014;54:100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Daley ML, Potter JD, McDowell WH. Salinization of urbanizing New Hampshire streams and groundwater: effects of road salt and hydrologic variability. J N AmBenthol Soc. 2009;28:929–940. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel MHB, Montebelo AA, Bernardes MC, Ometto J, DeCamargo PB, Krusche AV, Ballester MV, Victoria RL, Martinelli LA. Effects of urban sewage on dissolved oxygen, dissolved inorganic and organic carbon, and electrical conductivity of small streams along a gradient of urbanization in the Piracicaba River basin. Water Air and Soil Pollution. 2002;136(1–4):189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PJ, Wright IA, Jonasson OJ, Findlay SJ. Impact of concrete and PVC pipes on urban water chemistry. Urban Water Journal. 2010;7(4):233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Domone PL. A review of the hardened mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete. Cement & Concrete Composites. 2007;29(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Duan SW, Kaushal SS, Groffman PM, Band LE, Belt KT. Phosphorus export across an urban to rural gradient in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences. 2012;117 [Google Scholar]

- Duan S, Kaushal SS. Salinization alters fluxes of bioreactive elements from stream ecosystems across land use. Biogeosciences. 2015;12:7331–7347. doi: 10.5194/bg-12-7331-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois KD, Lee D, Veizer J. Isotopic constraints on alkalinity, dissolved organic carbon, and atmospheric carbon dioxide fluxes in the Mississippi River. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences. 2010;115 [Google Scholar]

- Elmore AJ, Kaushal SS. Disappearing headwaters: patterns of stream burial due to urbanization. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2008;6(6):308–312. [Google Scholar]

- Elvidge CD, Tuttle BT, Sutton PS, Baugh KE, Howard AT, Milesi C, Bhaduri BL, Nemani R. Global distribution and density of constructed impervious surfaces. Sensors. 2007;7(9):1962–1979. doi: 10.3390/s7091962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley JA, DeFries R, Asner GP, Barford C, Bonan G, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, Coe MT, Daily GC, Gibbs HK, Helkowski JH, Holloway T, Howard EA, Kucharik CJ, Monfreda C, Patz JA, Prentice IC, Ramankutty N, Snyder PK. Global consequences of land use. Science. 2005;309(5734):570–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1111772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortner SK, Lyons WB, Carey AE, Shipitalo MJ, Welch SA, Welch KA. Silicate weathering and CO2 consumption within agricultural landscapes, the Ohio-Tennessee River Basin, USA. Biogeosciences. 2012;9(3):941–955. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Fresca B, Sharp JM. Hydrogeologic considerations of urban development: Urban-induced recharge. In: Ehlen J, Haneberg WC, Larson RA, editors. Humans as Geologic Agents. Reviews in Engineering Geology. Geological Soc Amer Inc; Boulder: 2005. pp. 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Green SM, Machin R, Cresser MS. Effect of long-term changes in soil chemistry induced by road salt applications on N-transformations in roadside soils. Environmental Pollution. 2008;152(1):20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm NB, Faeth SH, Golubiewski NE, Redman CL, Wu JG, Bai XM, Briggs JM. Global change and the ecology of cities. Science. 2008;319(5864):756–760. doi: 10.1126/science.1150195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groffman PM, Law NL, Belt KT, Band LE, Fisher GT. Nitrogen fluxes and retention in urban watershed ecosystems. Ecosystems. 2004;7(4):393–403. [Google Scholar]

- Groffman PM. Stream chemistry for core sites in Gwynns Falls: concentration of Cl, NO3, PO4, total N and P, SO4, dissolved oxygen, E. coli, plus temperature, pH, clarity and turbidity: BES_0700/47 [Database] 2016 www.beslter.org.

- Guo JH, Wang FS, Vogt RD, Zhang YH, Liu CQ. Anthropogenically enhanced chemical weathering and carbon evasion in the Yangtze Basin. Scientific Reports. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep11941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs BJ, Sharp JM. Hydrogeological Impacts of Urbanization. Environmental & Engineering Geoscience. 2012;18(1):3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hope D, Billett MF, Cresser MS. A review of the export of carbon in river water – fluxes and processes. Environmental Pollution. 1994;84(3):301–324. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(94)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CE, Litaor MI, Billett MF, Bricker OP. Chemical Weathering in Small Catchments: Climatic and Anthropogenic Influences. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, SCOPE; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal SS, Belt KT. The Urban Watershed Continuum: Evolving Spatial and Temporal Dimensions. Urban Ecosystems. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11252-012-0226-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal SS. Increased Salinization Decreases Safe Drinking Water. Environmental Science & Technology. 2016;50(6):2765–2766. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal SS, Groffman PM, Band LE, Elliott EM, Shields CA, Kendall C. Tracking Nonpoint Source Nitrogen Pollution in Human-Impacted Watersheds. Environmental Science & Technology. 2011;45(19):8225–8232. doi: 10.1021/es200779e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal SS, Groffman PM, Band LE, Shields CA, Morgan RP, Palmer MA, Belt KT, Swan CM, Findlay SEG, Fisher GT. Interaction between urbanization and climate variability amplifies watershed nitrate export in Maryland. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008;42(16):5872–5878. doi: 10.1021/es800264f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal SS, Groffman PM, Likens GE, Belt KT, Stack WP, Kelly VR, Band LE, Fisher GT. Increased salinization of fresh water in the northeastern United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(38):13517–13520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506414102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal SS, Likens GE, Utz RM, Pace ML, Grese M, Yepsen M. Increased River Alkalinization in the Eastern US. Environmental Science & Technology. 2013;47(18):10302–10311. doi: 10.1021/es401046s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal SS, McDowell WH, Wollheim WM. Tracking evolution of urban biogeochemical cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry. 2014;121(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal SS, McDowell WH, Wollheim WM, Newcomer Johnson TA, Mayer PM, Belt KT, Pennino MJ. Urban Evolution: The Role of Water. Water. 2015;7(8):4063–4087. [Google Scholar]

- Koterba MT, Waldron MC, Kraus TEC. The water-quality monitoring program for the Baltimore reservoir system, 1981–2007—Description, review and evaluation, and framework integration for enhanced monitoring: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5101. 2011:133. also available at http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2011/5101.

- Likens GE, Driscoll CT, Buso DC. Long-term effects of acid rain: Response and recovery of a forest ecosystem. Science. 1996;272(5259):244–246. [Google Scholar]

- Lothenbach B, Le Saout G, Gallucci E, Scrivener K. Influence of limestone on the hydration of Portland cements. Cement and Concrete Research. 2008;38(6):848–860. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons WB, Harmon RS. Why Urban Geochemistry? Elements. 2012;8(6):417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Shanks Ken., editor. Maryland Department of Natural Resources in Partnership with Carroll County. Liberty Reservoir Watershed Characterization. Maryland Department of Natural Resources; Annapolis, Maryland: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Department of Planning. Maryland Department of Planning land use and land cover data from year 2000, Annapolis, Maryland, unnumbered table. Maryland Department of Natural Resources, 2002, Liberty Reservoir watershed characterization; Annapolis, Maryland: 2000. p. 28.p. 61. plus additional maps. [Google Scholar]

- Meybeck M. Global chemical-weathering of surficial rocks estimated from river dissolved loads. American Journal of Science. 1987;287(5):401–428. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer Johnson TA, Kaushal SS, Mayer PM, Grese MM. Effects of stormwater management and stream restoration on watershed nitrogen retention. Biogeochemistry. 2014;121:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Peters NE. Effects of urbanization on stream water quality in the city of Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Hydrological Processes. 2009;23(20):2860–2878. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister CA, Esbaugh AJ, Frieder CA, Baumann H, Bockmon EE, White MM, Carter BR, Benway HM, Blanchette CA, Carrington E, McClintock JB, McCorkle DC, McGillis WR, Mooney TA, Ziveri P. Detecting the Unexpected: A Research Framework for Ocean Acidification. Environmental Science & Technology. 2014;48(17):9982–9994. doi: 10.1021/es501936p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JD, McDowell WH, Helton AM, Daley ML. Incorporating urban infrastructure into biogeochemical assessment of urban tropical streams in Puerto Rico. Biogeochemistry. 2014;121(1):271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad MBK, Kaushal SS, Murtugudde R. Long-term pCO(2) dynamics in rivers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Applied Geochemistry. 2013;31:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Cole JJ. Increase in the export of alkalinity from North America's largest river. Science. 2003;301(5629):88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1083788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Oh NH, Turner RE, Broussard W. Anthropogenically enhanced fluxes of water and carbon from the Mississippi River. Nature. 2008;451(7177):449–452. doi: 10.1038/nature06505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley JB. Effects of ion-exchange on stream solute fluxes in a basin receiving highway deicing salts. Journal of Environmental Quality. 1994;23(5):977–986. doi: 10.2134/jeq1994.00472425002300050019x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CA, Band LE, Law N, Groffman PM, Kaushal SS, Savvas K, Fisher GT, Belt KT. Streamflow distribution of non-point source nitrogen export from urban-rural catchments in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Water Resources Research. 2008;44(9) [Google Scholar]

- Siver PA, Canavan RW, Field CK, Marsicano LJ, Lott AM. Historical changes in Connecticut lakes over a 55-year period. Journal of Environmental Quality. 1996;25(2):334–345. [Google Scholar]

- Sivirichi GM, Kaushal SS, Mayer PM, Welty C, Belt KT, Newcomer TA, Newcomb KD, Grese MM. Longitudinal variability in streamwater chemistry and carbon and nitrogen fluxes in restored and degraded urban stream networks. Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 2011;13:288–303. doi: 10.1039/c0em00055h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RM, Kaushal SS. Carbon cycle of an urban watershed: exports, sources, and metabolism. Biogeochemistry. 2015;126(1–2):173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Stets EG, Striegl RG. Carbon export by rivers draining the conterminous United States. Inland Waters. 2012;2(4):177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard JL. Trends in Catskill Stream Water-Quality - Evidence from historical data. Water Resources Research. 1991;27(11):2855–2864. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton GJP, Dise NB. The influence of catchment characteristics, agricultural activities and atmospheric deposition on the chemistry of small streams in the English Lake District. Science of the Total Environment. 1998;216(1–2):63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tobias C, Boehlke JK. Biological and geochemical controls on diel dissolved inorganic carbon cycling in a low-order agricultural stream: Implications for reach scales and beyond. Chemical Geology. 2011;283(1–2):18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tripler CE, Kaushal SS, Likens GE, Walter MT. Patterns in potassium dynamics in forest ecosystems. Ecology Letters. 2006;9(4):451–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CJ, Roy AH, Feminella JW, Cottingham PD, Groffman PM, Morgan RP. The urban stream syndrome: current knowledge and the search for a cure. Journal of the North American Benthological Society. 2005;24(3):706–723. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore TJ, Brenner M, Kolasa KV, Kenney WF, Riedinger-Whitmore MA, Curtis JH, Smoak JM. Inadvertent alkalization of a Florida lake caused by increased ionic and nutrient loading to its watershed. Journal of Paleolimnology. 2006;36(4):353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Hopkinson C, Rastetter E, Vallino J, Claessens L. Relationships of land use and stream solute concentrations in the Ipswich River basin, northeastern Massachusetts. Water Air and Soil Pollution. 2005;161(1–4):55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zampella RA, Procopio NA, Lathrop RG, Dow CL. Relationship of land-use/land-cover patterns and surface-water quality in the Mullica River basin. Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 2007;43(3):594–604. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Figure 1. Impervious cover for the Gwynns Falls watershed.

Supporting Figure 2. Sodium plus potassium vs. silica in stream water for streams across a land use gradient at the Baltimore LTER site.

Supporting Figure 3. Hydrographs for subwatersheds along the Gwynns Falls during the study period.