Abstract

Recently, guidelines have been outlined for management of immune-related adverse events occurring with immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer, irrespective of affected organ systems. Increasingly, these complications have been recognized as including diverse neuromuscular presentations, such as demyelinating and axonal length–dependent peripheral neuropathies, vasculitic neuropathy, myasthenia gravis, and myopathy. We present 2 cases of brachial plexopathy developing on anti–programmed cell death-1 checkpoint inhibitor therapies (pembrolizumab, nivolumab). Both cases had stereotypic lower-trunk brachial plexus–predominant onsets, and other clinical features distinguishing them from Parsonage-Turner syndrome (ie, idiopathic plexitis). Each case responded to withholding of anti–programmed cell death-1 therapy, along with initiation of high-dose methylprednisiolone therapy. However, both patients worsened when being weaned from corticosteroids. Discussed are the complexities in the decision to add a second-line immunosuppressant drug, such as infliximab, when dealing with neuritis attacks, for which improvement may be prolonged, given the inherent slow recovery seen with axonal injury. Integrated care with oncology and neurology is emphasized as best practice for affected patients.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: EMG, electromyographic examination; IV, intravenous; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NCS, nerve conduction study; PD-1, programmed cell death 1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; PET, positron emission tomography

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy historically has occurred secondary to direct neurotoxic effects, which are most commonly associated with platinum compounds, vinca alkaloids, taxanes, or proteasome inhibitors.1 We are entering an era of immune checkpoint inhibitor chemotherapies with neurological toxicities by immune-mediated mechanisms.2 Two important drugs in this category are pembrolizumab and nivolumab, which are both human IgG4 antibodies against programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1). These drugs were first recognized as being effective against melanoma, non–small-cell lung cancer, and renal cell carcinoma.3 Many other clinical trials have been reviewed since then and reveal efficacy against head and neck cancers, lymphoma, bladder cancer, and Merkel cell cancer.4, 5

The programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) pathway plays an important role in tumor-induced immunosuppression. Activated T cells encounter the PD-1 ligands PD-L1 (B7-H1) and programmed cell death ligand 2 (B7-DC) expressed by both immune and tumor cells, and this interaction leads to decreased T-cell receptor signaling, as well as reduced T-cell activation, cytokine production, and target-cell lysis.6 Programmed death ligand 1 (also known as CD274 and B7-H1)7 is more broadly expressed than programmed cell death ligand 2 on both hematopoietic and non hematopoietic cells, including tumor cells,8 where it functions to down-regulate effector T-cell activity and thereby protect tumors from immune attack.9, 10 Because cancer cells often have overexpressed PD-L1 antigens, PD-1 favors propagation of the metastatic state. Antibodies directed against PD-1 can selectively enhance T-cell activity against tumor antigens.3 However, a global shift in cellular reactivity by pro inflammatory Th1/Th17 response and disinhibition of the host's immune-regulating mechanisms also occurs.11 This shift can ultimately manifest itself with “immune-related adverse events” involving multiple systems, with significant morbidity and functional impairment.12

The peripheral nervous system is especially vulnerable to immune-mediated neuromuscular complications caused by misdirected T-cell reactions.13 Increasingly, case series have emerged that highlight the often severe peripheral nervous system complications that occur with these agents, including neuromuscular junction defects (myasthenia gravis),14, 15 muscle disease (necrotic myositis),16, 17 peripheral nerve vasculitis,18 and acute demyelinating (Guillain-Barré syndrome) neuropathies.19 Their identification and proper management are crucial in reducing morbidity and avoiding improper therapy for clinical mimics.12, 14

Methods

We reviewed 2 patients prospectively, in our oncology and neurology clinics, who developed brachial plexus neuropathy while undergoing anti–PD-1 inhibitor therapy for cancer. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Case 1

Case 1 is a 56-year-old man with metastatic melanoma positive for B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) V600E mutation taking pembrolizumab. Previous systemic therapy included a dabrafenib-trametinib (BRAF/EMK inhibition) combination, in addition to a previous history of bilateral axillary lymph node dissection and adjuvant radiation therapy, with a total dose of 3000 Gy at the time of original diagnosis. After his ninth pembrolizumab infusion, he developed sudden (<8 hours to maximal deficit) weakness of the left hand associated with loss of sensation and neuropathic pain in the medial hand, forearm, and back of hand. Pain was rated 7 of 10 (0 = no pain; 10 = worst possible pain), and weakness on the Medical Research Council scale included 75% weakness and sensory loss (Figure). The left brachioradialis reflex was reduced, and the left triceps reflex was absent. Horner syndrome was absent.

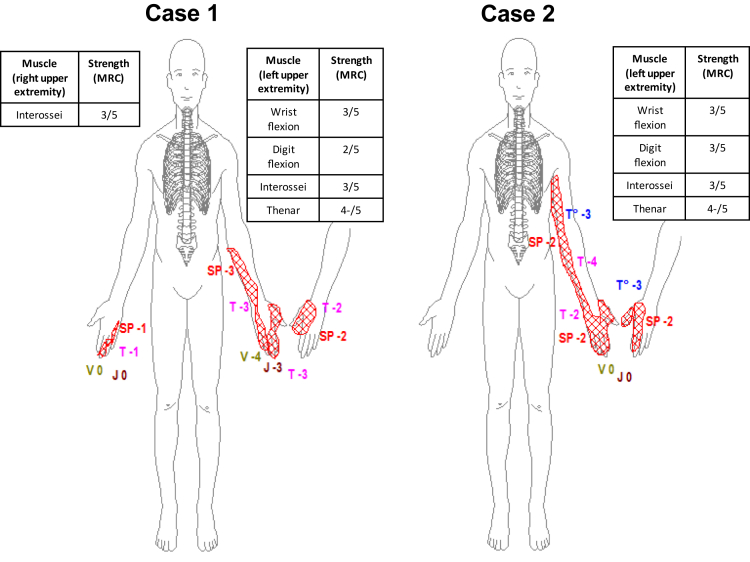

Figure.

Shown are the motor and sensory neurological deficits at maximum severity of 2 cases with anti–programmed cell death 1 brachial plexopathy. Case 1, with melanoma in remission on pembrolizumab, had an acute (<8-hour onset) attack of the left upper extremity, affecting predominantly the lower trunk of the brachial plexus, with improvement on high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone, with subsequent attack of the right upper extremity on oral dexamethasone. Case 2, while on nivolumab, developed a similar attack of the left upper extremity, also affecting the lower trunk of the brachial plexus, responsive to high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone. Both patients had their anti–programmed cell death 1 inhibitor therapy withheld and remain in oncological remission. MRC = Medical Research Council scale strength grading score; SP = painful sensation; V = vibration detection; J = joint position detection; T (lavender) = light touch detection; T (blue) = temperature sensation detection.

His immediate work-up, including computed tomography angiography of the left upper extremity, was unremarkable, with patent vasculature and no thrombus. A nerve conduction study (NCS) performed 4 days from onset revealed low-amplitude median compound muscle action potential recorded from the abductor pollicis brevis, with unobtainable F waves, and symmetric medial antebrachial sensory responses. Electromyographic examination (EMG) revealed mildly long-duration motor unit potentials in left C7-innervated muscles with no elicitable motor unit activation in the left abductor pollicis brevis and first dorsal interosseous muscles. Recruitment of motor units in muscles innervated by the lower trunk was markedly reduced. A repeat NCS-EMG 3 weeks after onset of symptoms with persistent weakness revealed fibrillations in lower trunk– and posterior cord–innervated brachial plexus muscles, with new loss of medial antebrachial sensory responses, consistent with a lower trunk–predominant brachial plexopathy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left brachial plexus did not reveal metastasis but rather features suggestive of a lower-trunk plexitis, as evidenced by a bright T2 signal without contrast enhancement. A whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) scan revealed no evidence of melanoma recurrence.

Pembrolizumab therapy was witheld at neurological presentation, and on day 3 from onset, we initiated intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone at 500 mg daily for 5 days, followed by 1 g daily for an additional 6 days. After the first week of receiving corticosteroids, his finger flexion strength improved to 4 of 5 and his interossei to 4- of 5, compared with earlier measurements of 2 of 5 and 3 of 5, respectively. Both the strength of other previously weak muscles and sensory deficits remained unchanged. The patient's left arm and forearm pain rating decreased to 4 of 10. Intravenous methylprednisolone was discontinued, and oral dexamethasone was initiated at 20 mg daily (ie, a prednisone equivalent of 1.5 mg/kg per day). He did not experience muscle atrophy, even in weak muscles, in combination with this or his subsequent attack.

Approximately 4 weeks after onset of initial symptoms and 3 weeks after a switch from high-dose IV methylprednisolone to oral dexamethasone, acute-onset (<8 hours), medial-aspect, right-hand and fifth-digit sensory loss, and right-hand finger flexor and abductor weakness developed. Physical examination revealed a 4 of 5 weakness measurement of hypothenar and interossei muscles in the right hand, with reduced sensation and paresthesia involving the medial right hand and fifth digit. Due to concern for recurrent neuropathy/brachial plexitis, IV methylprednisolone was again initiated, this time at 500 mg twice weekly for 4 weeks. A whole-body PET scan was performed, and the results ruled out melanoma recurrence. A repeated NCS-EMG performed 10 weeks after onset of symptoms in the right hand revealed evidence of a right lower trunk–predominant brachial plexopathy with predominant involvement of the medial cord. An MRI scan of the cervical spine (with and without gadolinium) did not reveal an alternative structural or infiltrative process. A slow weaning of the patient from corticosteroids began after clinical stabilization occurred. At 18 weeks from onset while the patient was taking oral prednisone alternating between 20 mg and 40 mg every other day, he remained stable, with right-hand symptoms unchanged and no further improvement of left-hand weakness and no cancer recurrence. He was unable to work at his job as a mechanic.

Case 2

Case 2 is a 50-year-old woman taking nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma after 800 mg/d of pazopanib had failed to control her cancer with progressive pulmonary metastasis. After the ninth infusion, she experienced sudden-onset (<8 hours), severe, left medial arm, forearm, and axilla pain, rated at its worst as 10 of 10 severity and not responsive to narcotics or pregabalin. This pain was associated with hand burning, prickling paresthesia, and loss of feeling extending on the medial forearm and arm, with a 4 of 5 weakness in finger flexors, thenar, and interossei musculature. Muscle strength measures and sensory examination results are shown in the Figure; muscle atrophy was not seen. The left triceps reflex was reduced, with other upper extremity reflexes being normal and symmetric. Brachial neuritis with predominant lower-trunk involvement was thought to be the most likely diagnosis.

Nivolumab was discontinued, and the patient was treated with daily IV methyprednisolone, 500 mg once daily for 7 days. The patient had rapid improvement of weakness, with strength measure returning to 5 of 5 in previously affected muscles, and resolution of numbness within 1 week of initiating methylprednisolone. An MRI scan of the brachial plexus extending to the shoulder yielded normal findings and did not reveal metastasis or T2 brightness, both with and without gadolinium. Oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg per day was continued, followed by a slow taper. An NCS-EMG performed 11 days after onset of symptoms and after marked clinical improvements revealed only evidence of a previously documented left median neuropathy at the wrist (ie, carpal tunnel syndrome), and she continued to improve. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis 3 weeks after onset of neuropathic symptoms revealed regression of pulmonary metastasis and hilar adenopathy.

Two months after discontinuation of her corticosteroids she had a new, severe, aching type of pain in her left hand, this time with point tenderness of the flexor retinaculum. Repeat MRI and neurological examination results were consistent with severe flexor tendonitis, superimposed on her earlier lower-trunk brachial plexitis. Her weakness and sensory loss had resolved compared with the earlier neurological examination, and repeated PET imaging results revealed continued improvements, including decrease in the size of the renal mass and previously noted pulmonary nodules. She remained off nivolumab. She underwent flexor retinaculum corticosteroid injections and remained stable, with no evidence of symptom recurrence at 14 weeks after the initial brachial plexopathy attack. She was able to return to work as a nurse.

Discussion

Recognition and treatment of anti–PD-1 inhibitor neurological toxicities can be challenging. Immune-suppressant treatments, including IV and oral corticosteroids, immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange, are linked with partial recovery.14, 18, 19 Recognition of the neurological complications associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy is important, largely to avoid potentially harmful therapies, and to make determinations regarding potential chemotherapeutic cessation. To our knowledge, including a PubMed review, brachial neuritis associated with pembrolizumab and/or nivolumab therapy has not been reported. Our 2 patients' attacks seem to be distinct from typical Parsonage-Turner syndrome, a potential disease mimic (Table).20 These features support a different pathophysiologic immune mechanism, as did the rapid improvement in case 2, which was suggestive of a neuropraxic mechanism not seen in Parsonage-Turner syndrome.21 However, the exact immune-mediated mechanism is not clarified by this or earlier reports of neuropathic adverse events, although peripheral T-cell dysregulation seems likely.14, 16, 19 Fortunately, neuropathic adverse effects induced by pembrolizumab and nivolumab seem to be uncommon and were found in a review of 496 treated melanoma patients to occur in only 8 patients.14

Table.

Anti Programmed Cell Death-1 Brachial Plexus Neuropathy vs Typical Parsonage-Turner Syndrome

| Measure | Anti–PD-1 brachial plexopathy | Parsonage-Turner syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of weakness | Acute (hours) | Subacute (days to weeks) |

| Anatomic localization | Lower trunk–predominant (C8-T1) | Upper trunk (C5-6) |

| Amyotrophy (muscle atrophy) | Not seen | Rapid onset (first week) |

| Response to high-dose corticosteroids | Pain, motor, sensory improvements | Pain predominant |

Both patients described in this report had rapid diagnosis and similar patterns of involvement, ie, lower-trunk brachial plexopathy. Discontinuation of anti–PD-1 therapy and initiation of IV and oral corticosteroid therapy occurred in both. Despite this therapy, Case 1 had incomplete improvement, with residual neurological deficits 18 weeks after onset of left brachial neuritis, in addition to contralateral upper extremity recurrence after discontinuation of high-dose IV corticosteroids. Case 2 had rapid and complete resolution after high-dose IV corticosteroids but experienced tendonitis with corticosteroid weaning. Attribution of the lack of response in Case 1 to a higher toxicity profile of pembrolizumab cannot be made accurately without accumulation of similar cases. Other cases of neuropathy with pembrolizumab are reported to improve significantly after therapy with glucocorticoids.18, 19

Recently, guidelines have been outlined for management of immune-related adverse events that occur with immune checkpoint inhibitors, irrespective of affected systems.12 Specifically, withholding of anti–PD-1 inhibitors and initiation of corticosteroids should be done in cases of Grade 2 to 4 adverse events, as defined by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.12, 22 In both of our cases, the symptoms were disabling—ie, Grade 3 or 4—but only longitudinally in Case 1. The guidelines also suggest that alternative immunosuppressive agents be used, including infliximab (5 mg/kg), if symptoms persist beyond 3 days while taking high-dose (>2 mg/kg equivalent) IV glucocorticoids. Peripheral neuropathy recovery is naturally more protracted, and longer intervals may be permissible for recovery. As an example, Parsonage-Turner syndrome recovery may be slow, often extending over a period of 1 to 2 years. In Case 1, initiation of infliximab could conceivably have prevented the second attack; in Case 2, the attack quickly resolved with corticosteroids. Therefore, the guidelines seem to be appropriate for these cases.12, 22 Exceptional cases likely occur, and the guidelines should provide only a framework for management strategies. Determining the best strategy for optimizing recovery from a neuropathy while minimizing risk of tumor recurrence from aggressive immunosuppression requires careful assessment. Close collaboration between oncologists and neurologists is critical for establishing the correct diagnosis, managing the patients, and ruling out possible mimics not caused by anti–PD-1 inhibitors. Mimics are predicted to become more common as patients survive longer and accrue common neurological illnesses that are not drug related, such as benign carpal tunnel syndrome, as seen in Case 2, and structural radiculopathies, both of which could mimic brachial neuritis attacks.

The spectrum of neurological complications from anti–PD-1 therapy has been expanded to include painful brachial plexus neuritis. Withholding PD-1 inhibitors and initiating high-dose corticosteroids seems to be beneficial, and whether to add corticosteroid-sparing agents such as infliximab to the course of therapy needs to be considered on an individual basis.

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Roxanna S. Dronca, Email: dronca.roxanna@mayo.edu.

Christopher J. Klein, Email: klein.christopher@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Cavaletti G., Marmiroli P. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(12):657–666. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen T.W., Razak A.R., Bedard P.L., Siu L.L., Hansen A.R. A systematic review of immune-related adverse event reporting in clinical trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(9):1824–1829. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topalian S.L., Hodi F.S., Brahmer J.R., et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamanishi J., Mandai M., Matsumura N., Abiko K., Baba T., Konishi I. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in cancer treatment: perspectives and issues. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21(3):462–473. doi: 10.1007/s10147-016-0959-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nghiem P.T., Bhatia S., Lipson E.J., et al. PD-1 Blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced Merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2542–2552. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumeister S.H., Freeman G.J., Dranoff G., Sharpe A.H. Coinhibitory pathways in immunotherapy for cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:539–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong H., Zhu G., Tamada K., Chen L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat Med. 1999;5(12):1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/70932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong H., Strome S.E., Salomao D.R., et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brahmer J.R., Drake C.G., Wollner I., et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong R.M., Scotland R.R., Lau R.L., et al. Programmed death-1 blockade enhances expansion and functional capacity of human melanoma antigen-specific CTLs. Int Immunol. 2007;19(10):1223–1234. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dulos J., Carven G.J., van Boxtel S.J., et al. PD-1 blockade augments Th1 and Th17 and suppresses Th2 responses in peripheral blood from patients with prostate and advanced melanoma cancer. J Immunother. 2012;35(2):169–178. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318247a4e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar V., Chaudhary N., Garg M., Floudas C.S., Soni P., Chandra A.B. Current diagnosis and management of immune related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:49. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein C.J. Autoimmune-mediated peripheral neuropathies and autoimmune pain. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;133:417–446. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63432-0.00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmer L., Goldinger S.M., Hofmann L., et al. Neurological, respiratory, musculoskeletal, cardiac and ocular side-effects of anti-PD-1 therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:210–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polat P., Donofrio P.D. Myasthenia gravis induced by nivolumab therapy in a patient with non-small-cell lung cancer. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54(3):507. doi: 10.1002/mus.25163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddox C.L., Shenoy N., Shah K.K., et al. Pembrolizumab induced bulbar myopathy and respiratory failure with necrotizing myositis of the diaphragm. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(3):673–675. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallet H., Gaillet A., Weiss N., et al. Pembrolizumab-induced necrotic myositis in a patient with metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(7):1352–1353. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aya F., Ruiz-Esquide V., Viladot M., et al. Vasculitic neuropathy induced by pembrolizumab. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(2):433–434. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Maleissye M.F., Nicolas G., Saiag P. Pembrolizumab-induced demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):296–297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1515584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsairis P., Dyck P.J., Mulder D.W. Natural history of brachial plexus neuropathy: report on 99 patients. Arch Neurol. 1972;27(2):109–117. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1972.00490140013004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suarez G.A., Giannini C., Bosch E.P., et al. Immune brachial plexus neuropathy: suggestive evidence for an inflammatory-immune pathogenesis. Neurology. 1996;46(2):559–561. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.2.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Health and Human Services Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). Version 4.03. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf Accessed August 5, 2017.