Abstract

Irreversible hypofunction of salivary glands is common in head and neck cancer survivors treated with radiotherapy and can only be temporarily relieved with current treatments. We found recently in mouse models that transient activation of Hedgehog pathway following irradiation rescued salivary gland function by preserving salivary stem/progenitor cells, parasympathetic innervation and microvessels. Due to huge differences between salivary glands of rodents and humans, to examine the translational potential of this approach, we evaluated effects of Shh gene transfer in a miniature pig model of irradiation-induced hyposalivation.

Methods: The right parotid of each pig was irradiated with a single dose of 20 Gray. Shh and control GFP genes were delivered into irradiated parotid glands by noninvasive retrograde ductal instillation of corresponding adenoviral vectors 4 or 16 weeks after irradiation. Parotid saliva was collected every two weeks. Parotid glands were collected 5 or 20 weeks after irradiation for histology, Western blot and qRT-PCR assays.

Results: Shh gene delivery 4 weeks after irradiation significantly improved stimulated saliva secretion and local blood supply up to 20 weeks, preserved saliva-producing acinar cells, parasympathetic innervation and microvessels as found in mouse models, and also activated autophagy and inhibited fibrogenesis in irradiated glands.

Conclusion: These data indicate the translational potential of transient activation of Hedgehog pathway to preserve salivary function following irradiation.

Keywords: hyposalivation, Hedgehog signaling, radiotherapy, gene therapy, pig model

Introduction

Head and neck cancers (HNC) including cancers in the oral cavity, pharynx, nasal cavity, sinuses and larynx account for about 4.2% of all cancers in USA with 70,340 estimated new cases in 2017 1 and with about 577,550 estimated survivors in 2026 2. Radiotherapy for HNC frequently exposes nondiseased salivary glands to irradiation (IR). Due to the exquisite radiosensitivity of salivary glands, irreversible hyposalivation is common (68.1%-90.9%) in long-term HNC survivors treated with conventional radiotherapy 3. The reduction of saliva secretion correlated significantly with the mean irradiation dose received by salivary glands 4. Novel intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) significantly decreased IR dose to salivary glands and the incidence of hyposalivation, but around 20% of patients treated with IMRT still have long-term hyposalivation and related weight loss 5. Hyposalivation exacerbates dental caries and periodontal disease, and causes dysgeusia and problems of sleep and speech, which severely impair the quality of life of patients. The irreversible hyposalivation is caused by the loss or impairment of saliva-producing acinar cells and the replacement by connective tissue and fibrosis. Multiple mechanisms contribute to IR-induced hyposalivation including the loss of functional glandular stem/progenitor cells 6, the impairment of parasympathetic innervation 7 and microvessels 8, and cellular senescence 9. Current treatments for IR-induced hyposalivation, such as artificial saliva and saliva secretion stimulators, can only temporarily relieve these symptoms. Gene therapy transferring water channel protein Aquaporin-1 locally showed promises to restore salivary gland function 10, but the rescue effect varies and needs to be improved.

Hedgehog (Hh) intercellular signaling pathway is highly conserved during evolution, required for branching morphogenesis of salivary glands 11 and activated during functional regeneration of adult salivary glands after obstructive damage 12. Hh signaling is triggered by the binding of Hh ligands such as Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) to receptor Patched (Ptch), which derepresses G protein-coupled receptor Smoothened (Smo) to activate Gli family zinc finger transcription factors and the consequent transcription of Hh target genes including Gli1 and Ptch1 13. Using mouse models we found recently that IR did not activate Hh/Gli signaling, whereas transient activation of Hh pathway in salivary gland by inducible expression of Shh transgene in Keratin5+ epithelial cells or adenovirus-mediated intragland transfer of Shh gene rescued IR-induced hyposalivation 14, 15. The underlying mechanisms of this rescue effect include the preservation of parasympathetic innervation, putative salivary stem/progenitor cells and microvessels through upregulation of angiogenic and neurotrophic factors.

Due to the huge difference between salivary glands of humans and rodents, it is necessary to re-examine our recent findings in large animal models. Here we report that in a miniature pig model of IR-induced hyposalivation, transient activation of Hh signaling by intragland transfer of Shh gene effectively mitigated the detrimental effect of IR on function of salivary glands. The underlying mechanisms are related to the alleviation of IR damages on microvessels and parasympathetic innervation, the inhibition of IR-induced cellular senescence, and the activation of autophagy. These data indicated that transient activation of Hh pathway is promising to preserve salivary gland function following radiotherapy in HNC patients.

Results

Retrograde ductal instillation of Ad-Shh transiently activated Hh pathway in parotids of miniature pigs

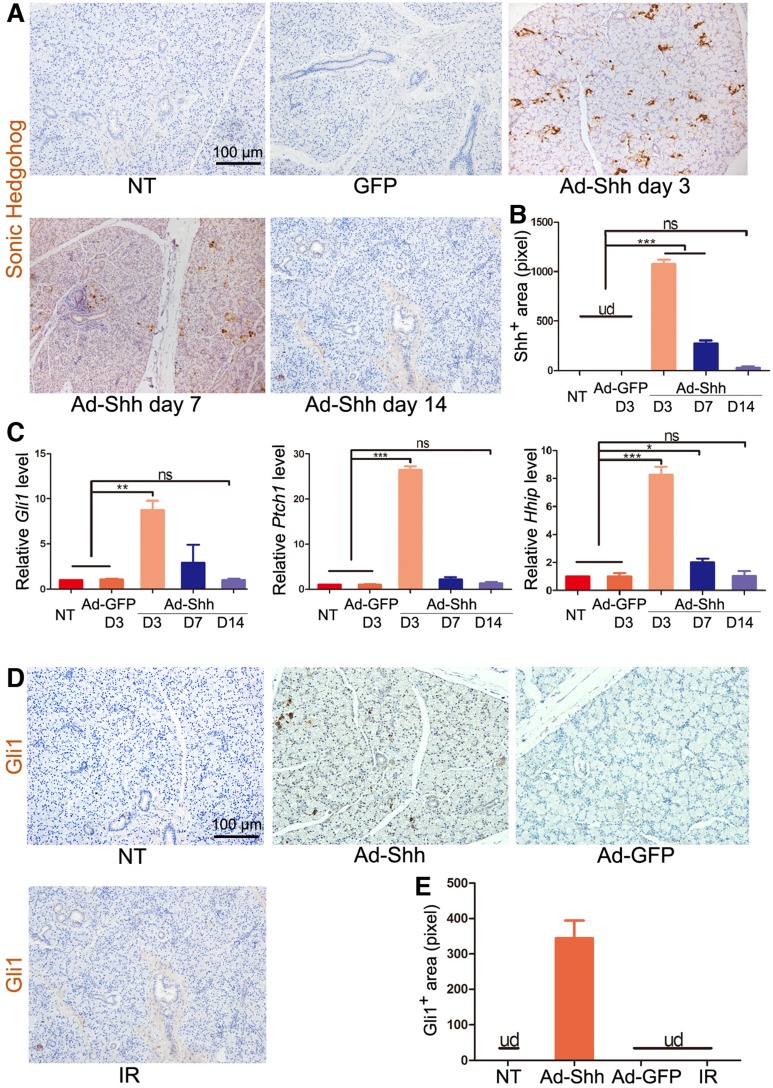

To determine the effect of adenovirus carrying rat Shh gene (Ad-Shh) on the activation of Hh/Gli signaling in salivary glands of miniature pigs, 2×1010 particles per gland of Ad-Shh or control adenoviral vector carrying the gene of green fluorescence protein (Ad-GFP) were delivered via retrograde instillation through duct cannulation into parotid glands. In non-treated (NT) and Ad-GFP-transferred parotid glands, Shh protein expression was undetectable (UD) by immunohistochemistry (IHC) at any time points examined, whereas, in Ad-Shh transferred parotids, Shh expression (brown) was strong on Day 3, weak on Day 7, and marginal on Day 14 as indicated by IHC (Figure 1A-B). In glands collected 3 days after Ad instillation, the expression of Hh target genes Gli1, Hhip and Ptch1 was significantly increased in Ad-Shh group but not in Ad-GFP group in comparison with NT controls as indicated by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis (Figure 1C, p < 0.01, n = 3). In glands collected 7 and 14 days after Ad-Shh instillation, the expression levels of these Hh target genes were either slightly higher or not significantly changed compared to NT group but were all significantly lower than that in Day 3 Ad-Shh group. Consistently, the expression of Gli1 protein (brown) was increased by intragland transfer of Shh but not GFP gene on Day 7, whereas IR did not activate Gli1 protein expression on Day 7 (Figure 1D-E). These data indicated that Shh gene delivery transiently and efficiently activated Hh/Gli pathway in parotid glands of miniature pigs.

Figure 1.

The expression of Shh transgene and Hh target genes after retrograde ductal instillation of Ad-Shh into pig parotids. (A) The representative IHC images of rat Shh protein (brown) encoded by Ad-Shh in parotids with no treatment (NT), 3 days after intragland delivery of Ad-GFP, and 3, 7 or 14 days after intragland delivery of Ad-Shh. (B) The quantification of Shh+ areas in IHC data from 3 independent samples and 10 fields per sample (n=30). Shh signal was undetected (ud) in NT and Ad-GFP groups. After Ad-Shh instillation, the Shh signal was highest on day 3 but successively decreased at day 7 and 14. (C) qRT-PCR analyses on the expression of Hh target genes Gli1, Ptch1, and Hhip in the above 5 groups of parotids indicated strong, weak and no upregulation of these Hh target genes 3, 7 and 14 days after Ad-Shh delivery, respectively (n=3). (D) Representative IHC images of pig Gli1 protein (brown) in parotids collected 5 weeks after IR or 1 week after Shh or GFP gene delivery. (E) Quantification of Gli1+ areas from IHC data (n=30). Gli1+ positive area was detected only in the Ad-Shh group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005; ns, not significant, P > 0.05.

Shh gene delivery preserved function of irradiated parotids

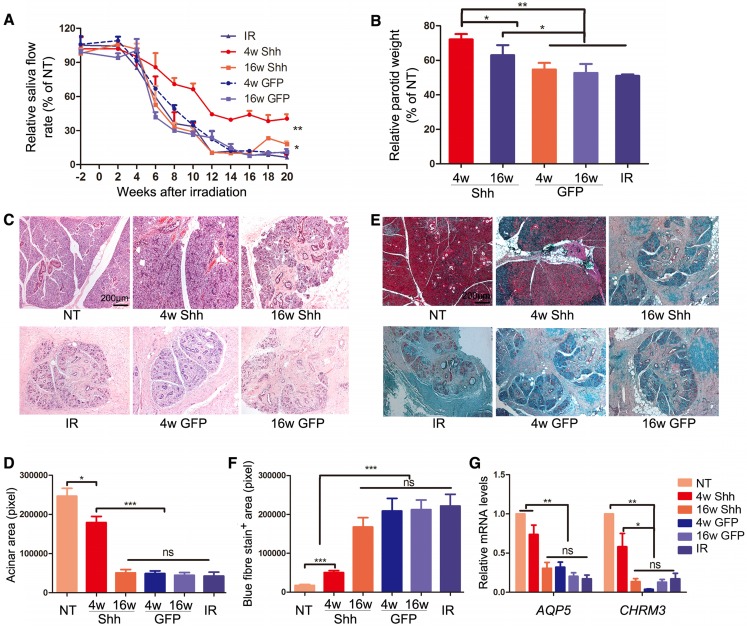

To establish the swine model of IR-induced hyposalivation, the parotid gland area at the right side of minipigs was irradiated with a single dose of 20 Gray (Gy) as we reported previously 16. To examine the effect of Ad-Shh delivery on IR-induced hyposalivation, 2×1010 particles of Ad-GFP or Ad-Shh were delivered into the right parotid gland of each pig via retrograde ductal instillation 4 or 16 weeks after IR (IR+Ad-GFP or IR+Ad-Shh, 4w or 16w) (Figure S1). In IR-only group, the stimulated parotid saliva flow rate was significantly reduced from Week 6, decreased to the bottom by Week 12 and was stable thereafter till the endpoint at Week 20 with a >90% decrease as expected (Figure 2A). Shh gene delivery 4 weeks after IR significantly improved the stimulated saliva flow rate of irradiated glands from Week 8 compared to IR or IR + Ad-GFP treatment, and maintained it at ~40% of NT glands of the same animal from Week 12 till the endpoint (Figure 2A, n = 3). Shh gene delivery 16 weeks after IR significantly improved the stimulated parotid saliva flow rate at Weeks 18 and 20 to about 18% of normal level compared to about 6% of normal level in IR or IR + Ad-GFP groups (Figure 2A, n = 3; Figure S3). After the last saliva collection on Week 20, the parotid glands were completely excised and weighed immediately. IR significantly deceased parotid weight normalized with NT parotid weight by Week 20, whereas the delivery of Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP at either 4 or 16 weeks after IR significantly increased normalized parotid weight (Figure 2B, n = 3). H&E and Masson's trichrome staining of parotid sections indicated that IR induced a significant reduction of acinar area and an increase of interlobular collagen deposition as reported 17, 18.

Figure 2.

Effects of Shh gene delivery on the function and histology of irradiated parotids. (A) Stimulated parotid saliva flow rates from the irradiated side or the NT side of animals with no further treatment or of animals who received delivery of Ad-GFP or Ad-Shh 4 or 16 weeks after IR into irradiated parotids were measured separately every two weeks from two weeks before IR until 20 weeks after IR. Percentages of saliva flow rate from the irradiated parotid to that from the NT parotid of the same pig are shown. (B) The wet weights of irradiated parotids collected 20 weeks after IR were normalized to that of NT parotid of the same pig. (C-D) Parotids collected 20 weeks after IR were examined by H&E staining and acinar areas were quantified from 30 fields from 3 independent samples (n=30). (E-F) Parotids collected 20 weeks after IR were examined by Masson's trichrome staining and the blue-stained fiber areas were quantified (n=30). (G) The expression of acinar markers AQP5 and Chrm3 in parotids collected 20 weeks after IR were examined by qRT-PCR (n=3).

Ad-Shh delivery at Week 4 obviously preserved acini structure and decreased collagen deposition, whereas Ad-Shh delivery at Week 16 or Ad-GFP delivery at either time points did not show any clear protective effects on both histology indexes (Figure 2C-F). Consistently, the mRNA expression of acinar marker Aquaporin 5 (AQP5) and Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor M3 (CHRM3) in parotid glands 20 weeks after IR was significantly downregulated by IR as reported 19-21, but improved by Shh gene delivery 4 weeks after IR as indicated by qRT-PCR (Figure 2G, n = 3). Notably, earlier delivery of Shh gene resulted in significantly better preservation of saliva secretion and Aqp5 expression than later delivery. These data indicate that single Shh gene delivery into parotid mitigated the detrimental effect of IR on parotid function.

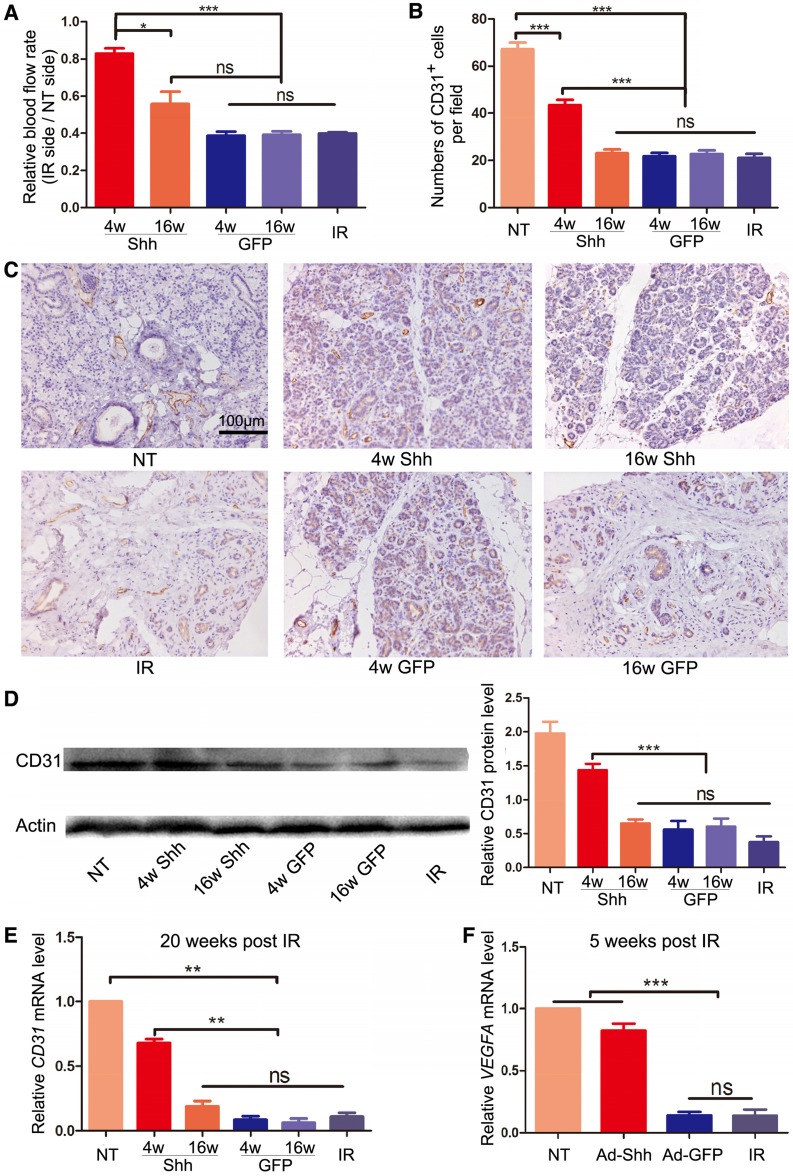

Intragland Shh gene delivery mitigated the microvascular damage by IR

The microvascular damage by IR is a major cause of hyposalivation following IR 8, 22. We examined blood flow rate in parotid glands with laser Doppler flowmetry 20 weeks after IR and confirmed that IR significantly decreased blood flow in irradiated glands to about 35% of that in non-treated glands (P < 0.001). Ad-Shh delivery at Week 4 significantly increased blood flow compared to IR alone and all other treatments (Figure 3A). Parotid glands collected 20 weeks after IR were examined for the microvascular density (MVD) by immunohistochemistry staining (IHC) against the endothelial marker CD31 as reported 8, 23, and the expression of CD31 was further quantified with Western blot and qRT-PCR. IR significantly decreased CD31+ MVD and the expression of CD31 at both protein and mRNA levels, whereas Ad-Shh instillation on Week 4 but not Week 16 after IR significantly preserved both indexes in parotid gland (Figure 3B-E). In multiple mouse organs, Hh/Gli signaling promotes angiogenesis during tissue repair and/or regeneration via inducing the secretion of pro-angiogenic factors 24. In glands collected 5 weeks after IR, qRT-PCR indicated that IR significantly decreased the mRNA expression of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), whereas Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP transfer at Week 4 significantly preserved VEGFA expression (Figure 3F). These data indicate that transient Hh activation alleviates the IR damage to microvascular endothelial cells likely through the upregulation of pro-angiogenic factors.

Figure 3.

Effects of Shh gene delivery on the microvascular damage caused by IR. (A) 20 weeks after IR, blood flow rates in both parotids were measured by Doppler flowmetry directly and presented as ratios between that of irradiated and non-irradiated parotid of the same pig. (B-C) Parotids collected 20 weeks after IR were examined with IHC for the endothelial marker CD31, and the numbers of CD31+ microvessel endothelial cells per 200x field in each treatment group were counted as microvascular densities (MVD) from 30 fields from 3 independent samples (n=30). (D-E) The expression levels of CD31 protein and mRNA in parotids 20 weeks after IR were examined with Western blot and qRT-PCR analyses (n=3). (F) The expression level of VEGFA mRNA in parotid 5 weeks after IR was examined by qRT-PCR (n=3).

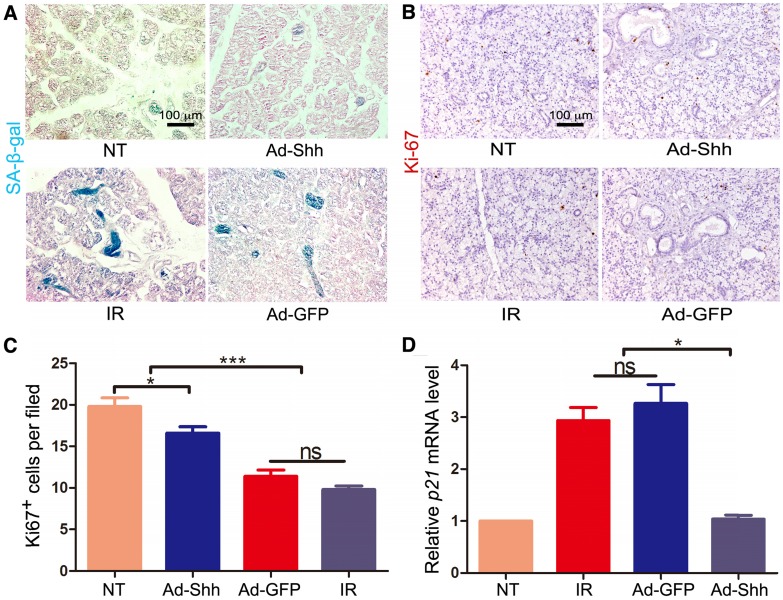

Intragland Shh gene delivery alleviated IR-induced cellular senescence

IR induces persistent DNA damage and cellular senescence in mouse salivary glands, which is a major cause of hyposalivation following IR in mouse models 9. We have revealed recently that Shh gene transfer in mouse salivary glands inhibited IR-induced cellular senescence by promoting DNA repair and reducing oxidative stress 25. To determine whether IR induces cellular senescence in pig salivary glands, we performed staining for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) on sections of parotid glands collected 5 weeks after IR. Compared to neglectable SA-β-gal signals in NT samples, IR alone induced obvious SA-β-gal activity mostly in ductal cells, whereas Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery at Week 4 after IR clearly inhibited the upregulation of SA-β-gal activity by IR (Figure 4A). Consistently, IHC for the proliferation marker Ki67 (brown) indicated that the proliferation of parotid cells was significantly inhibited by IR, and this inhibition was mitigated by Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery at Week 4 after IR (Figure 4B-C). On the other hand, qRT-PCR indicated that the expression of p21/CDKN1A, a cell cycle inhibitor and senescence marker, was significantly increased by IR, whereas Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery at Week 4 after IR abolished the p21 upregulation by IR (Figure 4D). These data indicated that transient activation of Hh pathway inhibited IR-induced cellular senescence in pig parotid glands.

Figure 4.

Effects of Shh gene delivery on the IR-induced cellular senescence. 5 weeks after IR, we collected parotids not irradiated (NT), irradiated alone (IR), and transduced with Ad-GFP or Ad-Shh 4 weeks after IR for the following assays. (A) The activity of senescence marker SA-β-gal (blue) in parotids was clearly increased by IR compared to the marginal activity in NT samples, and this increase was inhibited by Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery 4 weeks after IR. (B-C) IHC for the proliferation marker Ki67 indicated that Ki67 expression was significantly decreased by IR compared to the NT samples, and Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery 4 weeks after IR preserved Ki67 expression. (D) qRT-PCR analysis (n=3) indicated that the mRNA expression of senescence marker p21/CDKN1A was significantly increased by IR compared to NT samples, and this increase was significantly inhibited by Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery 4 weeks after IR.

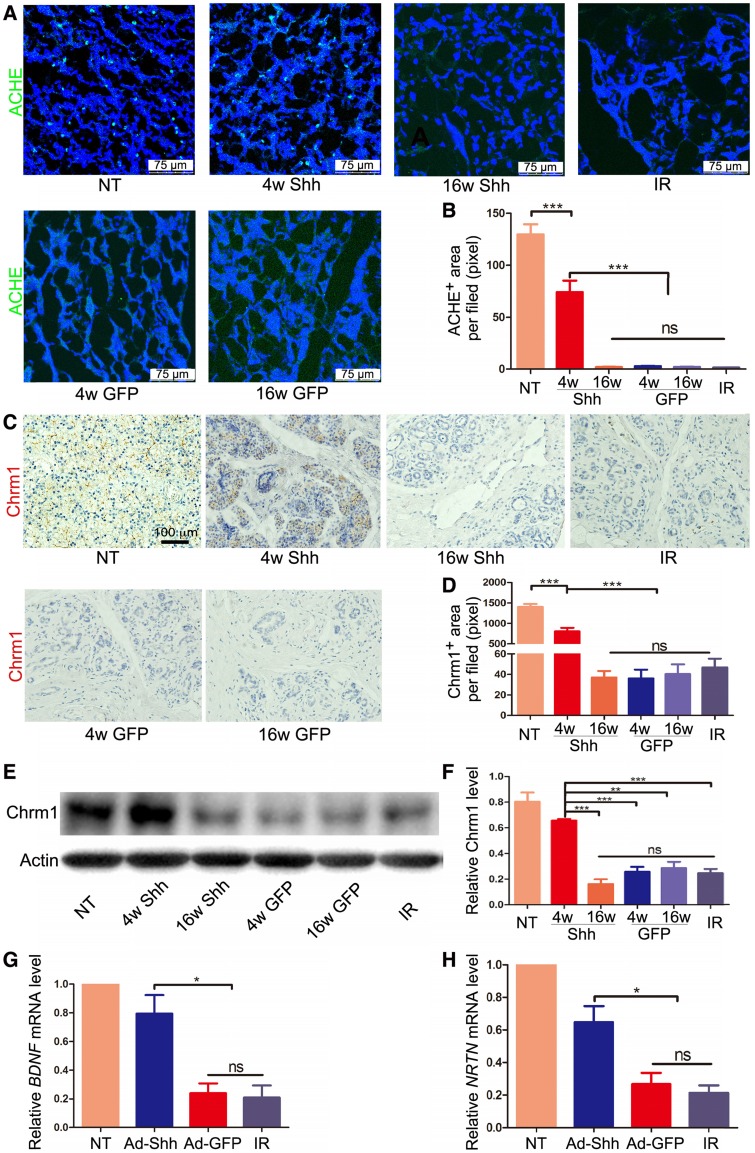

Intragland Shh gene delivery preserved parasympathetic innervation

Parasympathetic stimulation improves regeneration of mouse embryonic salivary gland after IR, and adult human salivary glands damaged by IR have reduced parasympathetic innervation 7. We found previously that IR impaired parasympathetic innervation similarly in adult mouse submandibular glands (SMGs), whereas transient expression of Shh transgene in salivary glands ameliorated such damage in adult mice by increasing production of neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), nerve growth factor (Ngf) and Neurturin (Nrtn) 15, 21. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining for acetylcholinesterase (ACHE), a marker of parasympathetic nerve 26, in pig parotids collected 20 weeks after IR indicated that IR clearly decreased ACHE expression, whereas Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery at Week 4 after IR significantly preserved ACHE expression (Figure 5A-B). Consistently, IHC indicated that the expression of Chrm1, the receptor of Acetylcholine related to preservation and expansion of mouse salivary progenitor cells regulated by parasympathetic innervation 27, was decreased by IR but preserved by Shh gene transfer 20 weeks after IR (Figure 5C-D). The IHC data were verified by the Western blot results of Chrm1 (Figure 5E-F). Consistent with the previous findings in mouse models 21, in parotids collected 5 weeks after IR the mRNA expression of neurotrophic factors BDNF and Neurturin was significantly decreased by IR but preserved by Ad-Shh instillation 4 week after IR (Figure 5G-H). These data indicated that Shh gene transfer following IR preserved the parasympathetic innervation in pig parotids likely through maintaining the expression of neurotrophic factors including BDNF and Neurturin.

Figure 5.

Effects of Shh gene delivery on the IR damage to parasympathetic innervation in parotids. (A-B) In parotids collected 20 weeks after IR, IF staining of parasympathetic innervation marker ACHE and quantification of ACHE signals indicated that parasympathetic innervation was impaired by IR but preserved by Ad-Shh transfer 4 weeks after IR, whereas Ad-Shh transfer 16 weeks after IR and Ad-GFP transfer at either time point did not significantly preserve ACHE expression (n=30). (C-D) IHC staining and quantification of cholinergic receptor muscarinic 1 (Chrm 1) in parotids 20 weeks after IR indicated that the Chrm1 expression was downregulated by IR but preserved by Ad-Shh transfer 4 weeks after IR, whereas Ad-Shh transfer 16 weeks after IR and Ad-GFP transfer at either time point did not significantly preserve Chrm1 expression (n=30). (E-F) Western blot and quantification of Chrm1 confirmed the IHC data (n=3). (G-H) In parotids collected 5 weeks after IR, qRT-PCR assays indicated that the mRNA expression of BDNF and NRTN was decreased by IR alone or IR plus GFP gene transfer, but was preserved by Shh gene transfer 4 weeks after IR (n=3).

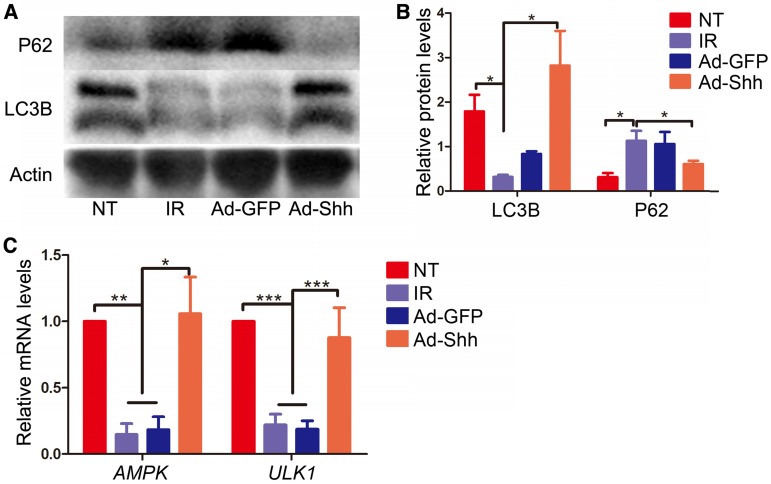

Intragland Shh gene delivery preserved autophagy activity in irradiated parotids likely through AMPK-ULK1 pathway

Autophagy, the natural mechanism of the cell to disassemble unnecessary or dysfunctional components, correlates with maintenance of salivary gland function following IR 28. Shh induced autophagy in cardiomyocytes undergoing oxygen or glucose deprivation through AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) / unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (Ulk1) pathway to protect cardiomyocytes in myocardial infarction 29. To determine whether intragland Shh gene could activate autophagy in miniature pig parotid after IR, we examined the expression of microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3β (LC3B) and P62/sequestosome 1 that positively and negatively correlate to autophagy respectively by Western blot in parotids collected 5 weeks after IR. IR down-regulated positive autophagy marker LC3B and up-regulated negative autophagy marker P62, whereas Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery after IR maintained both LC3B and P62 expression at levels comparable to NT (Figure 6A-B). Similar data of LC3B expression were obtained in parotid glands collected 20 weeks after IR (Figure S4), suggesting that the effects of IR and Shh gene delivery on autophagy were persistent. We also examined the relative mRNA expression of AMPK and ULK1 in Week 5 samples by qRT-PCR. The expression of both genes was down-regulated by IR and maintained by Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery at Week 4 after IR (Figure 6C). These data indicated Shh gene delivery preserved autophagy likely through the AMPK-ULK1 pathway in miniature pig parotid after IR.

Figure 6.

Effects of intragland Shh gene delivery on autophagy activity and AMPK-ULK1 pathway in irradiated parotids. (A-B) In parotids collected 5 weeks after IR, as indicated by Western blot analyses, IR significantly decreased the level of the positive autophagy marker LC3B and increased the level of the negative autophagy marker P62, whereas Ad-Shh but not Ad-GFP delivery significantly inhibited effects of IR on the expression of these two autophagy markers (n = 3). (C) In parotids 5 weeks after IR, the mRNA expression of AMPK and ULK1, two autophagy activators regulated by Hh signaling, was concurrently decreased by IR and resorted by Shh but not GFP gene delivery as indicated by qRT-PCR (n = 3).

Discussion

In our previous studies, the transient activation of Hh pathway in salivary glands by transient expression of Shh transgene rescued IR-induced hyposalivation in mouse models. However, rodent salivary glands are very different from those of humans in their size, morphology and gene expression profile. For instance, rodent SMGs contain a unique granular convoluted tubular structure producing a variety of growth factors that is absent in human salivary glands 30, whereas only about 65% of human salivary gland-specific genes showed similar levels of enrichment in mouse salivary glands 31.

Compared to rodents, the pig is a more suitable model for studies of human salivary gland diseases due to the similar size, shared morphological characteristics including the ductal system and the distribution of distinct types of acini, as well as the similar saliva flow rate 32. The miniature pig model has successfully predicated the clinical efficacy of Aqp1 gene therapy 16, and verified the essential role of microvessel damage in IR-induced hyposalivation 22. In order to verify the potential therapeutic effects of transient Hh activation on irradiated salivary glands in large animal models comparable to those of humans, we performed intragland Shh gene delivery in miniature pigs who received unilateral IR at the parotid region. We observed effectively preserved function of irradiated parotids up to 20 weeks after IR as indicated by the improved parotid saliva flow rate, the preservation of acinar structures and expression of acinar markers, and the inhibition of fibrogenesis. Consistent with our previous studies in mouse models, transient Hh activation in pig parotid glands preserved microvessels and parasympathetic innervation. Moreover, we confirmed that IR induced cellular senescence in pig parotid glands similarly to that in mouse SMGs, and found that transient Hh activation after IR effectively inhibited cellular senescence and preserved proliferation capacities of pig parotid cells, which likely also contributes to the Hh-mediated preservation of salivary gland function. In addition, we found that IR inhibited autophagy in parotid glands, whereas intragland Shh gene delivery preserved autophagy in both short-term and long-term likely through AMPK-ULK1 pathway.

The safety of intragland delivery of Ad-Shh was examined by histology analysis of multiple vital organs (heart, liver, spleen, kidneys and lungs) collected 20 weeks after IR and 16 weeks after Shh gene delivery. No obvious differences were observed between Shh and NT groups, which verified the safety of this strategy (Figure S5). Multiple Clinical laboratory analyses of serum including ALT, AST, ALP, LDH, Ca2+, K+, Na+, Cl- were also performed, and no changes were found except K+ (Table S1), which was consistent with our previous studies 16.

Taken together, our data indicated that Shh gene transfer is a feasible approach to mitigate the detrimental effect of IR on salivary gland function, likely through multiple mechanisms mentioned above.

Methods

Animals

Healthy littermate BA-MA male miniature pigs around 8 months old and weighing 25-35 kg were purchased from the Institute of Animal Science of the Chinese Agriculture University (Beijing, China). In total, 42 animals were housed and fed under conventional conditions as reported previously 12. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Capital Medical University (AEEI-2015-089).

Preparation and delivery of Adenoviral vectors

Adenoviral vectors encoding GFP or rat Shh (Ad-GFP or Ad-Shh, Applied Biological Materials Inc., Canada) were expanded in 293A cells and purified by two rounds of ultracentrifugation in a cesium chloride gradient. The titers (particles/mL) of purified vectors were determined by qPCR using Adeno-x rapid titer kit (Clontech). Miniature pigs were anesthetized with Ketamine (60 mg/kg) and Xylazine (8 mg/kg) intraperitoneally, and then vectors were delivered to the right side of the parotid gland by retrograde ductal instillation as reported 16 at a dose of 2×1010 particles per gland based on our experiences with similar adenoviral vectors 17.

Irradiation of parotid glands

We performed axial computerized tomographic scans to determine the irradiation (IR) plan using a three-dimensional treatment planning system (Pinnacle3, version 7.6; ADAC Inc., Concord, CA, USA). Calculations showed that more than 95% of the irradiation dose covered the whole target volume of the parotid gland. The reference point for all dose calculations was the center-targeted parotid gland. We used image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) technology for all IR. Miniature pigs were anesthetized with Ketamine and Xylazine as mentioned above. Before irradiation, the real-time image of the parotid gland area by iViewGT was aligned with the determined plan, and then the imaging workflow was integrated into the system. Thereafter, the animals were irradiated with 6 mV of photon energy at 3.2 Gy/min by Elekta Synergy accelerator (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) and received a single dose of 20 Gy (Figure S2).

Collection of saliva and blood

Parotid saliva was collected and salivary flow rates were determined using a modified Carlson-Crittenden cup as described previously 14 on anesthetized animals following an intramuscular injection of pilocarpine (0.1 mg/kg). In this study, we used a mechanical vacuum device (Shanghai Zhang Dong Medical, Shanghai, China), connected with the Carlson-Crittenden cup. Parotid saliva was collected from each parotid gland of all animals for ~10 min at the time points indicated in the Results section. Meanwhile, about 2 mL blood was collected from the precaval vein, and then serum was isolated for chemical analyses.

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses

Twenty weeks after irradiation the animals were sacrificed, the parotid glands were removed and weighed, then cut into pieces of ~5×5×5 mm3, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After being dehydrated with gradient ethanol, the samples were embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned at 5 μm thickness. The sections were stained either with hematoxylin and eosin for the evidence of pathological changes or immunohistochemically for the evidence of CD31 (1:50, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), Shh (1:100, Santa Cruz, USA), Gli 1(1:100, Santa Cruz), Chrm1 (1:100, Abcam, USA), Ki67 (1:100 Abcam) expression. Microvascular density (MVD) was determined by counting the number of CD31 positive cells per field at ×200 magnification. Frozen parotid sections were used for immunofluorescent staining. Sections were first incubated in a 1:50 dilution of anti-Ache (1:200, Abcam) or LC3B (1:400, Abcam). Primary antibodies were detected with appropriate secondary antibodies labeled with FITC (Vector Lab), and nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI. All parotid samples were labeled with numerical codes by investigators performing the treatment and sample collection, whereas the sectioning, histology/immunology staining, imaging and signal quantification of these samples were performed by investigators blinded to the experimental treatment. Two sections from two separate pieces of each parotid were randomly chosen for each type of staining, and 5 random 200x fields of each section were imaged for quantification (n = 3 × 2 × 5 = 30).

Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was done as reported 12. Primers for GAPDH, HHIP, PTCH1, CD31, GLI1, AQP5, BDNF, NRTN, C-KIT, P21, AMPK, ULK1, CHRM1, CHRM3 and VEGFA were designed with the Primer3 software (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3/). For Western blot, fresh parotid samples were homogenized with 40 μL T-PRE reagent containing protease inhibitors (Pierce, USA) per mg followed by centrifugation at 10,000 ×g for 5 min to collect supernatant. Western blot was done as reported 12 with antibodies against CD31 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), LC3B (1:2000, Abcam), P62 (1:5000, Abcam), Chrm1 (1:1000, Abcam) (Details in supplemental methods).

Clinical laboratory analyses of serum samples

Serum samples were analyzed for standard clinical biochemistry and enzyme indexes including serum calcium (Ca2+), potassium (K+), sodium (Na+), chloride (Cl-), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactatedehydrogenase (LDH) with commercial kits.

Statistics

All quantified data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison test. Statistical analyses and graphical generation of data were done with GraphPad Prism software. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials and methods, figures and table.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NIDCR 1R01DE022975-01 (to FL and SW), the National Natural Science Foundation of China 91649124 (to SW) and 81700991 (to ZZ), and Beijing Municipality Government (Beijing Scholar Program- PXM2018_014226_000021, PXM2017_014226_000023 and PXM2018_193312_000006_0028S643_FCG) (SW).

Author contributions

The study was conceived and supervised by SW and FL. LH and ZZ performed most of the experiments. BH, QZ and LQ contributed to preparation of adenoviral vectors. SC, LM, YX, XL, XF, XW contributed to part of the experiment. SW, FL and LH wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH. et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–89. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen SB, Pedersen AM, Vissink A, Andersen E, Brown CG, Davies AN. et al. A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: management strategies and economic impact. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1061–79. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roesink JM, Moerland MA, Hoekstra A, Van Rijk PP, Terhaard CH. Scintigraphic assessment of early and late parotid gland function after radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: a prospective study of dose-volume response relationships. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1451–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh-Laskar S, Yathiraj PH, Dutta D, Rangarajan V, Purandare N, Gupta T. et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial to compare 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy to intensity-modulated radiotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Long-term results. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1481–7. doi: 10.1002/hed.24263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konings AW, Coppes RP, Vissink A. On the mechanism of salivary gland radiosensitivity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knox SM, Lombaert IM, Haddox CL, Abrams SR, Cotrim A, Wilson AJ. et al. Parasympathetic stimulation improves epithelial organ regeneration. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1494. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotrim AP, Sowers A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ. Prevention of irradiation-induced salivary hypofunction by microvessel protection in mouse salivary glands. Mol Ther. 2007;15:2101–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marmary Y, Adar R, Gaska S, Wygoda A, Maly A, Cohen J. et al. Radiation-induced loss of salivary gland function is driven by cellular senescence and prevented by IL6 modulation. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1170–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vissink A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ, Limesand KH, Jensen SB, Fox PC. et al. Clinical management of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer patients: successes and barriers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:983–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haara O, Fujimori S, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Hartmann C, Thesleff I, Mikkola ML. Ectodysplasin and Wnt pathways are required for salivary gland branching morphogenesis. Development. 2011;138:2681–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.057711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hai B, Yang Z, Millar SE, Choi YS, Taketo MM, Nagy A. et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates postnatal development and regeneration of the salivary gland. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1793–801. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osterlund T, Kogerman P. Hedgehog signalling: how to get from Smo to Ci and Gli. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alaminos M, Perez-Kohler B, Garzon I, Garcia-Honduvilla N, Romero B, Campos A. et al. Transdifferentiation potentiality of human Wharton's jelly stem cells towards vascular endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:640–7. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hai B, Zhao Q, Qin L, Rangaraj D, Gutti VR, Liu F. Rescue effects and underlying mechanisms of intragland Shh gene delivery on irradiation-induced hyposalivation. Hum Gene Ther. 2016;27:390–9. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shan Z, Li J, Zheng C, Liu X, Fan Z, Zhang C. et al. Increased fluid secretion after adenoviral-mediated transfer of the human aquaporin-1 cDNA to irradiated miniature pig parotid glands. Mol Ther. 2005;11:444–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo L, Gao R, Xu J, Jin L, Cotrim AP, Yan X. et al. AdLTR2EF1alpha-FGF2-mediated prevention of fractionated irradiation-induced salivary hypofunction in swine. Gene Ther. 2014;21:866–73. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Y, Qu ZY, Cao SY, Li Q, Ma L, Krencik R. et al. Directed differentiation of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. J Neurosci Methods. 2016;266:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takagi K, Yamaguchi K, Sakurai T, Asari T, Hashimoto K, Terakawa S. Secretion of saliva in X-irradiated rat submandibular glands. Radiat Res. 2003;159:351–60. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0351:sosixi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hai B, Yang Z, Shangguan L, Zhao Y, Boyer A, Liu F. Concurrent transient activation of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway prevents radiation damage to salivary glands. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hai B, Qin L, Yang Z, Zhao Q, Shangguan L, Ti X. et al. Transient activation of hedgehog pathway rescued irradiation-induced hyposalivation by preserving salivary stem/progenitor cells and parasympathetic innervation. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:140–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Yan X, Gao R, Mao L, Cotrim AP, Zheng C. et al. Effect of irradiation on microvascular endothelial cells of parotid glands in the miniature pig. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delporte C, O'Connell BC, He X, Lancaster HE, O'Connell AC, Agre P. et al. Increased fluid secretion after adenoviral-mediated transfer of the aquaporin-1 cDNA to irradiated rat salivary glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3268–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pola R, Ling LE, Silver M, Corbley MJ, Kearney M, Blake Pepinsky R. et al. The morphogen Sonic hedgehog is an indirect angiogenic agent upregulating two families of angiogenic growth factors. Nat Med. 2001;7:706–11. doi: 10.1038/89083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hai B, Zhao Q, Deveau MA, Liu F. Delivery of sonic hedgehog gene repressed irradiation-induced cellular senescence in salivary glands by promoting DNA repair and reducing oxidative stress. Theranostics. 2018;8:1159–67. doi: 10.7150/thno.23373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi J, Luukko K, Poteryaev D, Laurikainen A, Sun YF, Laakso T. et al. Retarded growth and deficits in the enteric and parasympathetic nervous system in mice lacking GFR alpha2, a functional neurturin receptor. Neuron. 1999;22:243–52. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knox SM, Lombaert IM, Reed X, Vitale-Cross L, Gutkind JS, Hoffman MP. Parasympathetic innervation maintains epithelial progenitor cells during salivary organogenesis. Science. 2010;329:1645–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1192046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan-Bathke M, Hill GA, Harris ZI, Lin HH, Chibly AM, Klein RR. et al. Autophagy correlates with maintenance of salivary gland function following radiation. Scientific reports. 2014;4:5206. doi: 10.1038/srep05206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Q, Yang Y, Qin Y, He YH, Chen KX, Zhu JW. et al. AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent autophagy mediated the protective effect of sonic hedgehog pathway on oxygen glucose deprivation-induced injury of cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;457:419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amano O, Mizobe K, Bando Y, Sakiyama K. Anatomy and histology of rodent and human major salivary glands—overview of the Japan salivary gland society-sponsored workshop. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2012;45:241–50. doi: 10.1267/ahc.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gluck C, Min S, Oyelakin A, Smalley K, Sinha S, Romano RA. RNA-seq based transcriptomic map reveals new insights into mouse salivary gland development and maturation. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:923. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S, Liu Y, Fang D, Shi S. The miniature pig: a useful large animal model for dental and orofacial research. Oral Dis. 2007;13:530–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials and methods, figures and table.