Abstract

Purpose

The evidence is emerging that prescription medications are the topmost drivers of increasing health care costs in Canada. The financial burden of medications may lead individuals to adopt various rationing or restrictive behaviors, such as cost-related nonadherence (CRNA) to medications. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to provide an overview of the type, extent, and quantity of research available on CRNA to prescription drugs in Canada, and evaluate existing gaps in the literature.

Methods

The study was conducted using a scoping review methodology. Six databases were searched from inception till June 2017. Articles were considered for inclusion if they focused on extent, determinants, and consequences of CRNA to prescription medication use in the Canadian context. Variables extracted for data charting included author(s), year of publication, study design, the focus of the article, sample size, population characteristics, and key outcomes or results.

Results

This review found 37 studies that offered evidence on the extent, determinants, and consequences of CRNA to prescription medications in Canada. Depending on the population characteristics and province, the prevalence of CRNA varies between 4% and 36% in Canada. Canadians who are young (between 18 and 64 years), without drug insurance, have lower income or precarious or irregular employment, and high out-of-pocket expenditure on drugs are most likely to face CRNA to their prescriptions. The evidence that CRNA has negative health and social outcomes for patients is insufficient. Literature regarding the influence of prescribing health care professionals on patients’ decisions to stop taking medications is limited. There is also a dearth of literature that explores patients’ decisions and strategies to manage their prescription cost burden.

Conclusion

More evidence is required to make a strong case for national Pharmacare which can ensure universal, timely, and burden-free access to prescription medications for all Canadians.

Keywords: Pharmacare, medication adherence, drug costs, drug insurance

Video abstract

Introduction

Prescription medications play an important role in the treatment and prevention of disease, especially for people living with chronic conditions.1 However, costs associated with the long-term use may pose a lifetime economic burden on people who are in need of those medications.2 Evidence is emerging that prescription medications are the topmost drivers of increasing health care costs in Canada.3 In 2015, spending on prescription medications in Canada increased by 9.2% compared with 2014.4 Public plans contributed 44%, private insurance paid for 35%, and out-of-pocket payments made up the remaining 20% of the costs.4,5 These out-of-pocket payments potentially include direct out-of-pocket payments at the point of care, insurance premiums paid either directly or on payroll deduction, and user charges such as co-payments or deductibles.6

In Canada, public health insurance is meant to cover all medically necessary hospital, physician, and some long-term services – but not prescription medications.7 Furthermore, there is no national standard for drug coverage or drug purchasing in Canada.8 People are covered by either private insurance plans, or provincial drug benefit plans for older adults, people with disabilities, or people with catastrophic health needs.9 The extent of coverage, however, varies extensively among individuals, as well as the provinces.10

There is evidence that in the absence of insurance coverage for medications, patients are often in a position of having to make economic decisions about whether or not they will take their medications as prescribed. The decision to alter medication regimes for economic reasons is referred to as cost-related nonadherence (CRNA), such as stop filling prescriptions, delay prescriptions, or take less frequent and smaller doses to make them last longer.11 CRNA has been shown to have both direct and indirect effects on health and social outcomes of individuals, such as use of other medications and health services (doctor, specialist, and/or a hospital), and social consequences such as sacrificing other basic needs or taking loans to fulfill medication needs.11

Piette et al developed a conceptual model to understand the determinants of CRNA among patients with chronic illnesses.12 According to this framework, the cost–adherence relationship is determined by the interplay of various factors in context, such as:

characteristics related to patients themselves (eg, age, income, and employment status);

medication usage and its type (eg, importance of medications and complexity of dosing);

clinician-related factors (eg, medication choice, support provided by the doctors, and communication about medication costs); and

health system factors (eg, mechanisms to help low-income patients get the financial assistance for filling necessary prescriptions).12

The framework developed by Piette et al suggests that medication use and adherence is modified by various cost and non-cost factors, where some patients despite the costs use their medicines as per their prescription, while others report underuse or nonadherence despite having an apparent ability to afford their prescriptions.12 The framework was the first ever theoretically grounded conceptual model that laid the foundations to understand the construct of CRNA to medications in patients with chronic illness. In the early 2000s, the national political debates about prescription cost pressures started emerging in the USA.13 However, at the time, the sound theoretical basis for understanding the cost–adherence relationships among chronically ill patients was lacking. Therefore, this work of authors proved timely and crucial, both academically and politically, which built the stage for research, policy, and practice considerations to address the issue of CRNA among patients. Since then, the model has been applied and adapted widely to understand CRNA in various populations such as older adults and patients with diabetes and other chronic illnesses.14–18

Due to the mounting attention to the increasing costs of prescription medications in Canada over the past decade, many health care groups, advocacy associations, and health policy researchers have proposed different Pharmacare models for Canada.19,20 However, to date, no homogeneous analysis has been done that can inform Canadian policymakers and researchers regarding the extent, determinants, and consequences of CRNA to prescribed medications among Canadian people. Therefore, in this study, we aim to systematically map the literature on CRNA to prescription medications in Canada. We also report the type, extent, and quantity of research available21 on this topic and evaluate the existing gaps.

Methods

We conducted this study using a scoping review methodology developed by Arksey and O’Malley22 and supplemented by Colquhoun et al.21,23,24 The Arksey and O’Malley framework for the scoping review process defines five main stages that include identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting studies, charting the data, and then collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The search and review criteria were developed a priori by the authors, in consultation with a medical librarian with extensive experience conducting scoping reviews. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts (at the first stage of screening) and full-text articles (at the second stage for inclusion or exclusion of the articles) using a predefined charting form. However, the process was not linear. Our search strategy, criteria for article selection, and format for data charting were reviewed and revised several times in an iterative manner. Any disagreements were resolved with the guidance of senior authors on the paper.

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The research question guiding this scoping review was “What does the existing literature inform about the extent, determinants, and consequences of CRNA to prescription medications in Canada?”. We included studies that described:

the prevalence, frequency, and types of CRNA;

the determinants of CRNA; and

the evidence for health and social consequences of CRNA.

The conceptual framework developed by Piette et al (referred above) was used to identify and include studies that explored factors associated with CRNA to prescription medications, and for subsequent data charting and coding for analyses.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Studies were located through a comprehensive search of major electronic bibliographic databases and search engines that included Ovid MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Global Health, and Google Scholar. The search was done in June 2017 and updated on February 20, 2018. Reference list searching for some of the key articles was done to identify articles that did not emerge in the initial database search. The search terms included a combination of subject headings and free text terms – prescription fees, drug costs, prescription drugs, prescription drug cost, drug insurance, pharmaceutical services, medication adherence, cost-related non-adherence to medicines, and Canada. This combination of keywords varied to some extent as per the different indexing schemes used in each of the databases. Also, there is no uniform terminology to refer to the concept of CRNA. Therefore, we used various combinations of common key terms that are used in the Canadian studies such as “cost-related barriers to prescription drugs”,2 “prescription drug cost-related nonadherence”,25 “cost-related prescription nonadherence”,26,27 “effect of cost-sharing on use of medication”,28 “primary nonadherence with prescribed medication”,29 “medicine underuse due to cost”,30 “cost-related nonadherence to prescribed medicines”,31 and “prescription nonadherence due to cost”.32 The search strategy used to identify articles from PubMed is given in Box 1.

Box 1. Search terms used in PubMed.

((((((cost-related non-adherence to prescription medic*) OR cost-related non-adherence to prescription drug*) OR “Medication Adherence”[Mesh]) OR “Drug Costs”[Mesh]) OR “Insurance, Pharmaceutical Services”[Mesh]) AND “Canada”[Mesh] AND Journal Article[ptyp] AND full text[sb] AND English[lang] AND medline[sb]

Stage 3: study selection

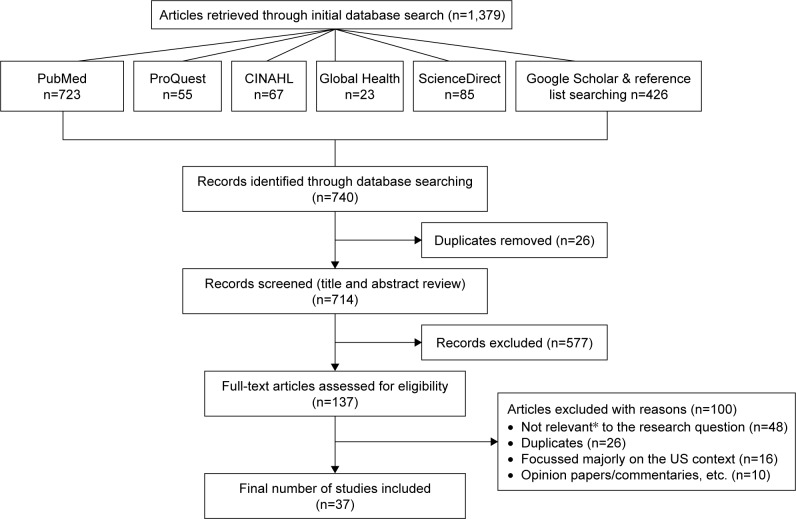

The articles we selected after initial screening, based on the review of titles and abstract, were further screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles were considered for inclusion if they focused on extent, determinants, and/or consequences of the financial burden of medications, in the Canadian context. We also limited selection to articles that were peer-reviewed, published in scholarly journals, and available in English. Studies were excluded if they did not focus on Canada or did not include Canadian population. The articles that were not available in English or did not have abstract or full text available were also excluded. We did not exclude any articles based on the study design, though the papers published as editorial letters, commentaries, news articles, or case studies were excluded. Articles meeting criteria were reviewed by the first author, and consensus for inclusion was reached through subsequent discussions with the other authors. A flowchart representing this procedure is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Note: *Focused on generic vs branded pricing and prescribing, formulary of public drug programs, prescription auditing, and polypharmacy.

Stage 4: charting the data

The variables extracted for data charting from the selected studies included author(s), year of publication, study design, sample size, population characteristics, study purpose, the focus of the article, and key outcomes or results. The data charting was done in an excel file based on which an analytical synthesis was prepared.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Following the recommendations of Arksey and O’Malley, results were reported using descriptive numerical summary and thematic analysis. A summary of descriptive findings was collated from the spreadsheet and is presented in Table 1. Key themes that were used to extract data were developed based on the research question of the study, and results are presented in Tables 2–4.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of the studies included in review

| Study | Province/country | Population characteristic | Sample size | Study design | Focus of the study | Outcome measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell et al35 | Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia | Adults with chronic conditions | N=1,849 | Population-based survey | Financial barriers to care including prescriptions | CRNA defined as stopped taking one or more medications for at least a week in last 12 months due to cost |

| Hennessy et al26 | Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia | Adults with chronic conditions | N=1,849 | Population-based survey | OOP spending on prescriptions and CRNA | CRNA defined if patients did not get drugs needed due to cost in the past 12 months |

| Tamblyn et al29 | Quebec | Patients accessing primary care | N=15,961 | Retrospective cohort study | Medication nonadherence with CRNA as one of the elements | Nonadherence defined as not filling incident prescription within 9 months |

| Hunter et al36 | Ontario and British Columbia | Homeless and vulnerably housed adults | N=716 | Prospective cohort study | Medication nonadherence with CRNA as one of the elements | CRNA defined as not taking medication prescribed by a doctor because it is too expensive |

| Kratzer et al51 | Ontario | Adults with chronic conditions | N=2,161,311 | Population-based survey | Effects of private drug coverage on prescription use | Drug use was defined as having drugs in the past month, and drug coverage was defined if private insurance covered all or part of the prescription medication cost |

| Ungar et al28 | Ontario | Children with asthma | N=17,046 | Retrospective cohort study using administrative database | Effect of cost-sharing on prescription use | Cost-sharing levels were categorized as: zero cost-sharing, <20% (low cost-sharing), and ≥20% (high cost-sharing) |

| McLeod et al58 | Pan-Canada | General Canadian population | N=14,430 | Population-based survey | Financial burden of prescription drug spending | Catastrophic OOP drug expenditure defined as HHs with drug budget share ≥10% |

| Després et al37 | Quebec | Non-senior adults with chronic conditions | N=2,872 | Retrospective cohort study | Effects of OOP costs on adherence in privately insured patients | Adherence defined as proportion of days covered over 1 year−the number of days supply of the medication during the follow-up period divided by the number of days of follow-up |

| Després et al34 | Quebec | Non-senior adults with chronic conditions | N=1,933 | Retrospective cohort study | Effects of OOP costs on adherence in publicly and privately insured patients | Adherence defined as proportion of days covered over 1 year |

| Kennedy and Morgan27 | Canada and the USA | Adult American and Canadian population | N=2,980 Canadians and 2,486 Americans | Population-based survey | Compare rates of CRNA for prescription drugs in the USA and Canada | CRNA identified if participant responded yes to “During the past 12 months, was there a time when you did not fill a prescription, or you skipped doses of your medicine, due to cost?” |

| Thanassoulis et al38 | Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia | Seniors with chronic conditions | N=67,040 | Cohort study using administrative data | Impact of type of drug coverage on medication use | Drug use was determined at 30 days of discharge, stratified by prescription plan in each province |

| Sanmartin et al6 | Pan-Canada | General population | N=98% Canadians | Population-based survey | Trends in health care expenditure including OOP expenditure on prescription medications | Direct expenditures and insurance premiums for prescription medications Direct expenditures defined as those not covered by insurance, such as exclusions, deductibles, and expenses over limits, and exclude payments for which individuals have been or will be reimbursed |

| Rotermann et al33 | Pan-Canada | General population | N=11,386 | Population-based survey | Determinants of prescription medication use including HH income | Drug use was determined if respondents had taken at least one prescription medication within 2 days of their HH interview |

| Allin and Hurley54 | Pan-Canada | General population | N=33,161 | Population-based survey | Impact of drug coverage on physician utilization | Physician utilization measured by asking if person has seen a family doctor or specialist in last 12 months |

| Kapur and Basu56 | Pan-Canada | General population | N=n/a | Population-based survey | Extent of drug coverage and financial burden of prescription drugs | Financial burden of prescription drugs calculated as OOP drug expenses of HHs as a proportion of HH income |

| Law et al25 | Pan-Canada | General population | N=5,732 | Population-based survey | Extent and determinants of CRNA | CRNA defined as if costs led people who reported taking medication in past year to do anything to make their prescription last longer, not fill a new prescription or not renew a prescription |

| Zhong53 | Ontario | General senior and non-senior population | N≥60,000 | Population-based survey | Inequality in drug use with respect to income | Drug utilization was determined by asking the participants: “How many different numbers of prescription drugs have you taken in the last 4 weeks?” |

| Millar50 | Pan-Canada | Senior and non- senior population diagnosed with a chronic disease | N=70,884 | Population-based survey | Availability of drug insurance and its effect on prescription drug use | Number of drugs taken in the past month used as an indicator of the influence of drug insurance coverage on medication use |

| Luffman57 | Pan-Canada | General senior and non-senior population | N≥20,000 HHs | Population-based survey | OOP prescription drug spending across various provinces | OOP drug spending referred to expenditures for medicines, drugs, and pharmaceutical products prescribed by a doctor such as exclusions, deductibles, and expenses over limits |

| Lee and Morgan31 | Pan-Canada | Senior population | N=5,269 | Population-based survey | CRNA and its determinants | CRNA defined as not filling a prescription or skipping doses within the last 12 months because of OOP costs, among those who reported taking at least one prescription |

| Kemp et al30 | Australia, Canada, the UK, the USA, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Germany | General population | N=8,898 | Population-based survey | CRNA and its determinants across countries | Cost-related medication underuse assessed if there was a time in the last 12 months when respondent did not collect a prescription or skipped doses because of the cost? (yes/no) |

| Hanley52 | Ontario | Non-senior population | N=31,630 | Population-based survey | Impact of prescription drug insurance on unmet health care needs | Unmet health care need was identified if participants decided not to seek care because he or she anticipated that a visit to a physician would result in a prescription |

| Dhaliwal et al45 | Alberta | Individuals with heart disease | N=13 | Qualitative study | Experiences of patients who reported financial barriers to care including prescriptions | CRNA was identified if participants shared that they forgo their pills if they cannot afford it |

| Dewa et al7 | Pan-Canada | Senior and non-senior community- dwelling Canadians | N=33,000 | Population-based survey | Characteristics of people covered or not covered for public prescription drug insurance | Having a drug insurance was identified if participant said yes to “Do you have insurance that covers all or part of the costs of your prescription medications?” |

| Demers et al10 | Pan-Canada | Senior and non-senior individuals including social assistance recipients | N=32* scenarios | Policy analysis | To examine the impact of variation in provincially funded public drug benefits on patients’ prescription drug costs having similar prescription needs | Cost-sharing strategies were examined in the form of premium, deductible, co-payment, and maximum annual contribution by the beneficiary, and pharmacists’ dispensing fees |

| Kennedy and Morgan32 | Canada and the USA | Adult American and Canadian population | N=8,688 | Population-based survey | Extent and determinants of CRNA in two countries | CRNA was measured as failure to obtain prescribed medication due to cost in the prior month |

| Guilcher et al43 | Pan-Canada | Health care professional, non-health professionals, and policymakers | N=180 | Qualitative study | Perspectives of key stakeholders about the availability and use of prescription drugs for neurological conditions | n/a |

| Wang et al46 | Pan-Canada (Quebec vs rest of Canada) | Canadians between age of 12 and 64 | N=10,653 | Experimental study | Impact of universal prescription drug insurance on health care utilization and health outcomes | Drug insurance status was determined if a person reported having drug insurance. Measures of health care utilization include drug utilization, physician visits, and hospitalization. Drug utilization measures the number of distinct medications taken in the previous month |

| Zheng et al49 | Ontario | Patients visiting an outpatient clinic | N=60 | Small survey | Predictors leading to CRNA | CRNA was assessed by asking patients to think for last 12 months and describe how frequently they left prescriptions unfilled, delayed filling prescriptions, took prescriptions with reduced frequency, and lowered dosages because of the cost |

| Goldsmith et al44 | Ontario and British Columbia | Adults engaging in CRNA in past or currently | N=35 | Qualitative study | Understand patients’ experiences of CRNA through typology development | CRNA was explored by asking participants’ most recent experience with stopping, reducing, or not filling a prescription medication due to OOP costs |

| Yao et al39 | Saskatchewan | Seniors with chronic illnesses | N=188,109 | Retrospective cohort study | Quantify the impact of drug benefit plan on medication adherence that capped OOP costs at $15 per prescriptions | Adherence was measured over 365 days using medication possession ratio |

| Assayag et al40 | Quebec | Non-senior patients with depression | N=2,249 | Matched cohort study | Adherence between privately and publicly insured patients | Adherence over 1 year was estimated using the proportion of prescribed days covered |

| Daw and Morgan42 | Pan-Canada | n/a | N=n/a | Analyses of administrative database | Review of provincial drug benefit programs to find factors leading to catastrophic drug expenditures | Assessed premiums and cost-sharing mechanisms in the form of the expenses borne by the patient (or via supplementary private insurance): deductibles, co-payments/co-insurance, and OOP limits to find catastrophic drug expenditures |

| Anis et al41 | British Columbia | Elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis | N=2,968 | Retrospective cohort study using administrative database | Effect of prescription drug cost-sharing on overall health care utilization | In people who reached the annual maximum co- payment of $200 for any calendar year from 1997 to 2000, the outcomes assessed were number of hospital admissions, the number of physician visits, and the total number of prescriptions filled |

| Tamblyn et al47 | Quebec | Elderly and welfare recipients | N=93,950 elderly persons and 55,333 adults on welfare | Interrupted time series analysis | Adverse effects of prescription drug cost- sharing on overall health care utilization | Mean number of drugs used per month, ED visits, and hospitalization, nursing home admission, and mortality before and after policy introduction |

| Lexchin and Grootendorst48 | Industrialized countries including Canada | Vulnerable population | N=25 studies | Systematic review of literature | Effects of user fees for prescription drugs on drug use, other health services use, and overall health status | User fee included costs that patients pay OOP for prescriptions such as in the form of co-payment, deductibles, reimbursement limits, etc. |

| Law et al55 | Pan-Canada | General population | N=28,091 | Population-based survey | Consequences for prescription drug costs | Health consequences that led to use of additional health care services such as a doctor visit or ER visit, and other consequences leading to trade-offs between prescriptions and other basic needs |

Note:

Number of case scenarios.

Abbreviations: CRNA, cost-related nonadherence; OOP, out-of-pocket; HH, household; ED, emergency department; ER, emergency room; n/a, not available.

Table 2.

Extent of cost-related nonadherence to prescription medications

| Extent | Population | Province | Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.6% reported CRNA to medications ranging from 3.6% (95% CI 2.4–4.5) to 35.6% (95% CI 26.1–44.9) depending on income and availability of insurance | General population | Pan-Canada | Law et al25 |

| 2 | 8.2% reported CRNA to medications who were prescribed at least one medication in last 12 months | General population | Pan-Canada | Law et al55 |

| 3 | 8.3% Canadians aged 55 years and older reported CRNA to medications | Senior population | Pan-Canada | Lee and Morgan31 |

| 4 | 15% reported CRNA to medications | Patients visiting outpatient clinic | Ontario | Zheng et al49 |

| 5 | Prevalence of CRNA between privately and publicly insured individuals was 14% and 18%, respectively | Non-senior patients with depression | Quebec | Assayag et al40 |

| 6 | 4.1% reported CRNA to medications | Adults with chronic conditions | Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia | Hennessy et al26 |

| 7 | 13% reported stopped taking medications in last 12 months at least for a week due to cost | Adults with chronic conditions | Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia | Campbell et al35 |

| 8 | 31.3% of the incident prescriptions were not filled in the last 9 months | Patients accessing primary care | Quebec | Tamblyn et al29 |

| 9 | 26% reported nonadherence to prescriptions | Homeless and precariously housed adults | Ontario and British Columbia | Hunter et al36 |

Abbreviation: CRNA, cost-related non-adherence.

Table 3.

Factors associated with cost-related nonadherence

| Factors | Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low income or lack of regular employment (n=15) | Hennessy et al;26 Sanmartin et al;6 Rotermann et al;33 Kapur and Basu;56 Law et al;25,55 Zhong;53 Millar;50 Lee and Morgan;31 Kemp et al;30 Dewa et al;7 Kennedy and Morgan;32 Guilcher et al;43 Goldsmith et al;44 Daw and Morgan42 |

| 2 | Young age (non-senior) (n=12) | Tamblyn et al;29 Hunter et al;36 Kennedy and Morgan;27,32 Kapur and Basu;56 Millar;50 Lee and Morgan;31 Kemp et al;30 Dewa et al;7 Guilcher et al;43 Yao et al;39 Law et al55 |

| 3 | Multiple comorbidities, chronic illness, severe illness, or poor health status (n=10) | Hennessy et al;26 Tamblyn et al;29 Kratzer et al;51 Kennedy and Morgan;27,32 Law et al;25,55 Millar;50 Lee and Morgan;31 Kemp et al30 |

| 4 | High out-of-pocket expenditure on drugs, and expensive or costly drugs (n=10) | Campbell et al;35 Hennessy et al;26 Tamblyn et al;29 Ungar et al;28 Després et al;37 Kemp et al;30 Zheng et al;49 Goldsmith et al;44 Daw and Morgan;42 Demers et al10 |

| 5 | No drug insurance (n=9) | Rotermann et al;33 Law et al;25,55 Zhong;53 Millar;50 Lee and Morgan;31 Kennedy and Morgan;32 Zheng et al;49 Goldsmith et al44 |

| 6 | Province of residence (n=7) | McLeod et al;58 Thanassoulis et al;38 Kapur and Basu;56 Law et al;25,55 Luffman;57 Daw and Morgan42 |

| 7 | Having public drug insurance vs private insurance (n=5) | Kratzer et al;51 Després et al;34 Kemp et al;30 Lee and Morgan;31 Zheng et al49 |

| 8 | Race and ethnicity: immigrant or aboriginal status, or being non-white (n=3) | Law et al;55 Dewa et al;7 Zhong53 |

| 9 | Not having a primary physician (n=3) | Hunter et al;36 Tamblyn et al;29 Kennedy and Morgan32 |

| 10 | Women (sex) (n=2) | Kennedy and Morgan;27 Law et al55 |

| 11 | Less education (n=2) | Kapur and Basu;56 Zhong53 |

| 12 | Living alone or not having spouse or partner (n=2) | Kapur and Basu;56 Dewa et al7 |

| 13 | Living in a rural area (n=1) | Kapur and Basu56 |

Table 4.

Impact of cost-related nonadherence to prescription medications

| Impact/consequences | Population | Province | Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Relative to those with no drug insurance, the insured make more use of physician services after controlling for need of seeking care | General population | Pan-Canada | Allin and Hurley54 |

| 2 | People without prescription drug insurance were more than twice as likely as those with insurance to report an unmet need for health care | Non-senior population | Pan-Canada | Hanley52 |

| 3 | Introduction of the mandatory drug coverage program increased medication use and GP visits. No statistically significant effects were found for specialist visits and hospitalization | Canadians between age of 12 and 64 | Pan-Canada | Wang et al46 |

| 4 | Across the 4 years, there were 0.38 more physician visits per month, 0.50 fewer prescriptions filled per month, and 0.52 fewer prescriptions filled per physician visit, during the cost-sharing period than during the free period. Among patients who were admitted to the hospital at least once, there were 0.013 more admissions per month during the cost- sharing period than during the free period | Elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis | British Columbia | Anis et al41 |

| 5 | After co-payments were introduced, the number of prescription drugs used per day decreased by 9% among older people and by 16% among those receiving social assistance; these reductions were associated with an increased rate of emergency department visits by 14.2 and 54.2 events per 10,000 person-months, respectively | Elderly and welfare recipients | Quebec | Tamblyn et al47 |

| 6 | Cost-sharing leads patients foregoing essential medications and to a decline in health care status. Co-payments or a cap on the monthly number of subsidized prescriptions lower drug costs for the payer, but any savings offset by increases in other health care areas | Vulnerable population | OECD countries including Canada | Lexchin and Grootendorst48 |

| 7 | Many Canadians forewent basic needs such as food (about 730,000 people), heat (about 238,000), and other health care expenses (about 239,000) because of drug costs | General population | Pan-Canada | Law et al55 |

| 8 | Some participants identified that their CRNA led to adverse clinical outcomes. Some of them also “separated” medications into essential and nonessential categories and prioritized medications over healthy food | Individuals with heart disease | Alberta | Dhaliwal et al45 |

| 9 | Self-reported financial barriers to drugs were not found significantly associated with increased number of emergency department visits or hospitalizations, though patients facing financial barriers to take medications were 50% less likely to take medications | Adults with chronic conditions | Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia | Campbell et al35 |

Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; CRNA, cost-related non-adherence.

Results

The initial database search retrieved a total of 740 articles, out of which 37 were included in the final review. A summary of the selected 37 articles is presented in Table 1.

Characteristics of the records included in the study

Year published

Out of 37 studies, 16 were published in last 5 years, with a maximum number of studies published in 2014 (n=5).6,29,33–35 The remaining included (n=16) studies were published between 1999 and 2012.

Study design

There were a large number of studies (n=19) that used data from population-based surveys (self-reported; telephone or mail-based surveys) with sample size varying between 5,000 and 70,000 people. These surveys included Canadian Community Health Survey, Barriers to Care for People with Chronic Health Conditions, National Population Health Survey, International Health Policy Survey, Canadian Health Measure Survey, Ontario Health Survey, Family Expenditure Survey, and Survey of Household Spending. Nine studies adopted retrospective or prospective cohort designs where population cohorts were identified using administrative database.28,29,34,36–41 Studies that used administrative data utilized pharmacy databases, private insurance claims, public drug benefit insurance claims, or electronic health records of the patients accessing primary care in public health institutions. Two studies used data obtained from the National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System and the Canadian Pharmacists Association.10,42 Three studies were based on qualitative methods.43–45 One study adopted a natural experimental design,46 while one was based on interrupted time series analysis.47 One of the included studies was a review article,48 while one was based on a small survey.49

Participant characteristics

The majority of the studies (n=17) included both senior and non-senior general community-dwelling individuals or family households living in Canada. Twelve studies involved patients having chronic illnesses/conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, depression, rheumatoid arthritis, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, and asthma.26,28,34,35,37–41,45,50,51 Within these 12 studies, five involved both elderly and non-elderly population with chronic conditions, three included non-elderly with chronic conditions, three included only elderly with chronic conditions, and one focused on children (<18 years) with chronic conditions. Three studies involved patients accessing primary care.29,44,49 One study specifically focused on senior population (>65 years),31 one included seniors and social assistance recipients,47 one review article focused specifically on persons more vulnerable and poor,48 and one study included only non-senior population (between 18 and 64 years).52 One study included individuals who are homeless,36 and one involved health care professionals and policymakers focusing on people with long-term neurological conditions.43

Geographical representation

Out of 37 studies, 14 were Pan-Canadian, that is, included participants/data from all Canadian provinces. Five studies were conducted in Ontario,28,49,51–53 six in Quebec,29,34,37,38,40,47 one in Saskatchewan,39 one in British Columbia,41 and one in Alberta.45 Five studies compared/studied prescription drug policy of selected provinces in Canada.26,35,36,38,44 Four studies included data from several countries that compared Canada with other countries such as the USA, the UK, New Zealand, Australia, the Netherlands, and Germany.27,30,32,48

Focus of the included studies

Of the total 37 studies, 12 primarily focused on CRNA.25–27,30–32,34,37,39,40,44,49 Eight studies focused on the impact or consequences of prescription medication costs or cost-related barriers on health and/or social outcomes such as access or utilization of other health care services.41,45–48,52,54,55 Six studies analyzed the effects of having prescription drug insurance on prescription drug use,7,10,38,50,51,56 while four focused on the impact of out-of-pocket costs and income on prescription drug use.6,28,33,53 Three studies analyzed and reviewed out-of-pocket costs of prescriptions including catastrophic drug costs across provinces or provincial drug benefit programs.6,57,58 Two studies focused on general nonadherence with CRNA to medications as one of the elements.29,36 Two studies discussed general cost-related barriers to health care including financial burden of prescription medication costs.35,45 One study collected the perspectives of various stakeholders on the affordability of necessary prescription medications for people with neurological conditions in Canada.43

Measurement/operationalization of CRNA

The most common method used to measure CRNA was based on a survey question which asked participants: “During the past 12 months, have you ever taken less of your medication than prescribed because of cost such as skipping doses or not filling a prescription?” (n=6).25–27,30,31,49 Three studies used “proportion or number of days covered” method which measured adherence through the number of days covered by prescription refills over 1 year.34,37,40 One study defined CRNA as failure to obtain prescribed medication due to cost in the prior month.32 One study measured adherence over 365 days using medication possession ratio.39 One qualitative study focused on developing the typology of CRNA but did not mention any particular way of measuring it.44

Thematic analysis

Based on the research question for the study, we used three themes related to extent, determinants, and consequences of CRNA to medications for the data synthesis. These themes are represented and discussed here.

Extent of CRNA to prescription medications

Out of the total studies included, nine measured the prevalence of CRNA within their participant population which varied between 4.1% and 35.6%, depending on the participant characteristics and provinces (Table 2).25,26,29,31,35,36,40,49,55

Overall, the national prevalence including both seniors and non-seniors was reported at 9.6% in 2012,25 which decreased slightly to 8.2% in 2018 as reported by the same group of authors in their recent study.55 However, in 2012, the extent of CRNA varied between 3.6% (95% CI 2.4–4.5) and 35.6% (95% CI 26.1–44.9) depending on income and availability of insurance.25 This national study also found that rates of CRNA were lowest in Quebec (7.2%, 95% CI 4.5–9.8) and highest in British Columbia (17.0%, 95% CI 12.6–21.4).25

Focusing on the senior population, another recent national study reported that around one in 12 (8.3%) Canadians aged 55 years and older faced CRNA to prescription medications in 2014.31 Among people accessing primary care in Quebec, prevalence of CRNA was reported at 31.3%.29 Among those who were homeless and precariously housed, CRNA was experienced by 26% of the participants, residing in Ontario and British Columbia.36 A study involving people with cardiovascular-related chronic conditions across four provinces (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia) reported that around 14% of the participants reported lack of drug insurance coverage, out of which 4.1% faced financial barriers to accessing medications leading to nonadherence,16 while another study conducted with similar population in these four provinces reported that 13% of the respondents had stopped taking medications due to cost.35 A study comparing prevalence of CRNA between privately and publicly insured individuals reported it as 14% and 18%, respectively.40

Determinants of CRNA to prescription medications

Twenty-nine studies identified the most common factors that predict someone’s risk of facing CRNA to medications. We describe these factors under four categories as per the Piette model.

Person-/patient-related factors

Within the person-/patient-related factors, lower household or personal income (specifically below CAD 30,000 a year) and lack of regular employment are the primary predictors of CRNA reported by the highest number of studies (n=15). After individuals’ income and employment status, young age (ie, <55 years) (n=12), poor health status (ie, having a chronic illness, severe health condition, or multiple comorbidities) (n=10), and not having drug insurance (n=9) are the most common person-related factors that lead individuals to forgo their medications or skip or split doses due to cost. The national-level studies suggest that Canadians who are younger, in worse health, have lower income, precarious or irregular employment, and no drug insurance are most likely to face cost-related barriers to their prescriptions.25,31,32,43,50

Having prescription drug insurance was also reported to be significantly associated with having access to prescription medication without financial barriers.25,31–33,44,49,50,53,55 A recent qualitative study exploring the typology of CRNA among adults who reported engaging in CRNA found that an array of factors such as individuals’ financial flexibility, the importance of the drug, burden of the drug costs, and having insurance interact with each other and influence CRNA in individuals.44 A number of studies also reported that people with chronic conditions holding private drug insurance were more likely to use prescription drugs than those having public drug insurance.30,31,34,49,51 A study analyzing risk of not having prescription drug insurance coverage reported that people residing in one of the Atlantic Provinces, Manitoba, or Saskatchewan, who were young (<25 years or to a lesser extent 25–34 years), had no post-secondary education, self-employed, working part-year or part-time, single persons living on their own, living in a rural area, and belonging to households with lower or middle income had a higher risk of not having prescription drug insurance coverage.56

Other factors that were found related but reported in only a few studies included sex, education, relationship status, ethnicity, and place of residence. These studies reported that being female,27,55 having education less than high school,53,56 living alone,7,56 being non-white, immigrant or aboriginal status,7,53,55 and living in a rural area56 increased the risk of facing financial barriers to medications (Table 3).

Drug-related factors

High drug costs (ie, >5% of annual household income or >$20 a month out-of-pocket) (n=10) was the major determinant of CRNA.4,11,15,18,19,29,39 Three studies including people with cardiovascular conditions found that those spending >5% costs of medications out of their pocket were more likely to report CRNA than those spending <5%.4,11,15 Another study also reported that drugs in the upper quartile of cost were least likely to be filled29 in congruence with another smaller survey which found that spending >$100 a month out-of-pocket increased the likelihood of CRNA among patients.49 Quantifying the impact of senior drug benefit plan launched in 2007 that capped out-of-pocket costs at $15 per prescription for seniors on chronic medication reported that the impact of the program on adherence was consistently demonstrated in subgroups of patients receiving medications costing between $16 and $30 and those costing ≥$30.39 A large retrospective study involving patients accessing primary care in Quebec also found that costly drugs and co-payments for low-income groups (along with young age and more severe comorbidities) were significantly associated with nonadherence.29

Health system-related factors

A large number of studies analyzed the effects of variations in provincial drug benefit programs on prescription drug costs.7,10,12,26,35,46–48 These variations in the provincial drug benefit programs were found to be having significant implications on the costs that patients pay for same medications and hence the extent of CRNA they face. McLeod et al found substantial interprovincial variation in the prevalence of catastrophic prescription drug costs paid by senior and social assistance households.58 Demers et al found that the eligibility criteria and cost-sharing mechanisms of public drug programs differed markedly across provinces, resulting in people with the same prescription needs bearing different financial costs.10 They found that seniors paid ≤35% of their prescription costs in two provinces, but elsewhere they may pay as much as 100%. With few exceptions, non-seniors paid >35% of their prescription costs in every province, while most social assistance recipients paid ≤35% of their prescription costs in five provinces and pay no costs in the other five. In 2002, Ontario residents spent the least out-of-pocket cost for prescription drugs (less than CAD 300), while Saskatchewan residents spent the most (more than CAD 400). Families in Alberta, British Columbia, and Quebec spent less (between CAD 300 and 350) than those in the Atlantic provinces (more than CAD 400) and Manitoba (between CAD 350 and 400), reflecting the differences in prescription drug coverage, employment status, health status, and age structure of the provincial population.57

Three studies compared the reasons of self-reported medicine underuse due to cost across different countries having different health systems including Canada.27,30,32 An international study comparing Canada and six other countries found that approximately one-fifth of the respondents in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the US, with annual out-of-pocket costs over $500, reported underusing medicines due to cost.30 This study found that cost-related underuse of medicines was least common in countries with lowest out-of-pocket costs and reduced co-payments or cost ceilings for low-income patients, the Netherlands and the UK. Analysis from two other international health policy surveys between Canada and the USA found that Canadians were less likely than Americans to report cost-associated nonadherence (5.1% vs 9.9%, P<0.001 in 2001; 23.1% vs 8.0%, P<0.001 in 2007); however, in both the countries, people without prescription drug coverage were significantly more likely than those with insurance to report cost-associated nonadherence.27,32

One qualitative study collected data from policymakers and health care professionals and highlighted the effect of governance and structure of drug programs in Canada on access to drugs for individuals with neurological conditions. The study identified various factors such as shortage on drug formulary listings, lengthy processes for new drug approvals, the complexity of applying and confirming eligibility for coverage, piecemeal coverage across jurisdictions, and lack of collaboration among public, private, and industry sectors that affected access to prescription drugs for people with neurological conditions in Canada.43 The study reported that “participants identified frustrations with respect to the lack of standardization among Canadian jurisdictions as to which drugs are publicly covered under the provincial and territorial formularies” (p. 393) and concluded that “these differences can impact choice of permanent residence, as participants described individuals relocating within Canada in order to obtain better drug coverage” (p. 392).43

Clinician-related factors

Of the 37 studies included in this review, three explored clinician-/physician-related factors determining cost–adherence relationship for patients.29,32,36 A retrospective study involving >15,000 patients accessing primary care reported that patients who had a greater proportion of physician visits with the prescribing physician had lower odds of nonadherence.29 Similarly, among individuals who were homeless, a study found that lack of access to a physician was one among the most common reasons identified by participants for not adhering to their medications.36 However, Kennedy and Morgan reported that the number of physician visits did not significantly predict nonadherence after controlling for other factors.32 We did not find any other studies that explored the effect of support or propensity of prescribing health care professionals to take into account financial situations of patients on decisions that patients make to manage prescription cost burden.

Consequences of CRNA to prescription medications

Of the 37 articles included, nine discussed the potential impact that prescription drug costs can have on individual health or social outcomes (Table 4).

Health consequences

Evidence regarding the impact of CRNA on individual health outcomes such as disease exacerbation, poor self-reported health, increase in symptoms leading to increasing hospitalizations, emergency department visits, or mortality was limited and mixed. Of seven studies that we found on this topic, three explored the effects of having drug insurance coverage on utilization of other health care services,46,52,54 three explored the effects of co-payments or cost-sharing for drugs on the utilization of other health care services,41,47,48 and one explored the association between CRNA and health service utilization.28

A recent study by Wang et al found that a mandatory universal drug insurance program substantially increased the physician visits among Canadians aged between 12 and 64 years.46 A study examining the impact of private drug financing on the utilization of physician services in Ontario revealed that people with prescription drug insurance make more physician visits than those without insurance.54 A study by Hanley found that adults who did not have prescription drug insurance were 1.27 times more likely to report an unmet need for health care than those with insurance.52

Few studies reported that cost-sharing for drugs in the form of co-payments leads patients to foregoing essential medications and a decline in health care status, especially in the vulnerable population.48 A study conducted with elderly and social assistance recipients in Quebec in 2001 found that after co-payments were introduced, prescription drug use reduced by 9% and 16%, respectively, which was further associated with increased rate of emergency department visits in this population.47 Another study compared the prescription drug use, physician service utilization, and hospital admissions among elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis when they paid a co-payment for medications (cost-sharing period) vs when they did not (free period).41 The study found that during the cost-sharing period, there were increased physician visits, fewer prescriptions filled, and increased hospital admissions per month as compared to free period.41 Another study including people with cardiovascular conditions found that although self-reported financial barriers to drugs were not significantly associated with increased emergency department visits or hospitalizations, patients facing financial barriers to medications were 50% less likely to take statins.35

Social consequences

Of total nine studies we found on consequences of CRNA, only two discussed the social outcomes and/or strategies adopted by the individuals to cope and manage the medication costs.45,55 Law et al drawing from the Canadian Community Health Survey 2016 reported that around 1.2 million Canadians forewent basic needs such as food, heat, and other health care expenses because of drug costs, and >100,000 Canadians had an additional physician visit, emergency department visit, and hospital stay due to CRNA.55 This was supported by a qualitative study collecting data from individuals with heart diseases in Alberta which reported that individuals who faced financial barriers to medications prioritized essential medication over other nonessential medications and over healthy food and faced adverse clinical outcomes due to nonadherence to medications associated with cost.45

Discussion

The growing evidence on the barriers faced by Canadians to fulfill necessary medications has given a strong impetus to the national Pharmacare debate. Many negotiations and discussions are underway calling for a solution to this big drug problem in Canada, and there has been a fair difference in the suggested propositions. Our study informs this conversation by answering three key questions that are at the core of this national discourse: first, how many Canadians face CRNA to fulfill their medications; second, who are at risk of facing CRNA; and third, what outcomes or consequences they face or might face due to CRNA. Answers to these questions will help policymakers and researchers in agenda-setting and future policy and program development.

In this scoping study, we found 37 articles that offered some evidence on the extent, determinants, and consequences of CRNA to prescription medications in Canada. Findings suggest the following:

Depending on the population characteristics and provinces, the prevalence of CRNA varies between 4% and 36%.

The most common factors associated with CRNA include age (between 18 and 64 years), employment status or income, health status, lack of insurance coverage, and high out-of-pocket cost of medications. Though, these factors may be confounded with each other.

Evidence on the impact of CRNA to prescriptions on individual health outcomes such as disease exacerbation, poor self-reported health, increase in symptoms leading to an increase in hospitalizations or emergency department visits, or mortality is limited and mixed.

The literature regarding social outcomes and/or strategies adopted by the individuals to cope and manage the medication costs is absolutely insufficient.

Findings of our study resonate with the results from studies done in countries other than Canada, both having different and similar health care system arrangements for prescription medications. A national study from Israel reported that around 10% of chronically ill patients faced CRNA that was strongly associated with their lower income, unemployment, lack of physician explanation about the prescribed medication, and age.59 A study from the USA showed strong correlation between co-payments paid by the patients and medication underuse.16 Another study reported that age <65 years, lack of drug coverage, increased number of overnight hospitalizations, and greater functional limitations were associated with greater likelihood of CRNA among diabetic patients, while nursing home residence decreased risk.18 CRNA was least common in countries with lowest out-of-pocket costs, and reduced co-payments or cost ceilings for low-income patients.27,30,32 Overall, across all the countries, people without prescription drug coverage were significantly more likely than those with insurance to report cost-associated nonadherence.

Although studies examining the consequences of CRNA on individual health outcomes are limited in the Canadian context, a number of studies from other countries report that CRNA to prescription drugs has a negative impact on the health outcomes of people who face these barriers.60–62 Internationally, evidence on social outcomes and/or strategies adopted by the individuals to cope and manage the medication costs is also emerging. A study exploring strategies patients use to reduce the cost burden of prescriptions across the UK and Italy reported that commonly used strategies were not to get prescribed drugs at all, prioritizing by not getting all prescribed medicines or delay purchasing medicines until they got paid, or cost-consciously self-medicating with over-the-counter products for minor conditions.63 Another study from the USA reported that patients coped with medication costs by obtaining free samples from physicians, splitting doses so medications last longer, buying drugs from other countries and/or over the internet, or buying medications through the Veterans Administration.64

Methodological issues in the included studies

It must be noted that available literature on CRNA with in the context of Canada adopts no national or international standards to define, conceptualize, and measure CRNA, which leads to lack of uniformity across the studies and hence the results drawn from these studies. Additionally, a majority of the studies are either survey based that used data from large population-based national and international surveys, or cohort studies that used administrative claims databases. Both of these methods have some limitations that should be taken into consideration. First, the studies using claims data to assess adherence may not necessarily represent the actual consumption of prescribed medications or cannot account for medications that were not purchased due to cost.37,58 Second, most of the national surveys collected data over the phone.27,30–32,35 Though in national or international surveys, sample was intended to represent the general population, telephone-based surveys may underrep-resent the most socially disadvantaged, individuals in remote areas, and individuals who do not own landline phones. It is also possible that some participants might not feel comfortable reporting underusing medicines because of cost, in which case the occurrence of cost-related underuse would be underestimated by these studies.65 Third, as most of the survey data were self-reported, they may have a recall bias or a social desirability bias.26 Fourth, studies that analyzed various provincial drug benefit programs or utilized claims data from provincial programs possibly included only those drugs that were on the public formularies and hence could not have accounted for those drugs that did not fall onto the list or for which claims were rejected.

Gaps in the current literature

Within the Canadian context, there is a lack of literature that examines the effect of the propensity of prescribing health care professionals to discuss economic issues with their patients on determining cost–adherence relationships for them. It is important to explore and find how patients’ experiences can be improved through the support from clinicians. For example, prescribing less costly alternative or generic medication or having conversations about the medication costs may have a positive effect on decisions that patients make to manage their prescription cost burden.55 Studies on strategies adopted by patients to cope with prescription cost burden, such as reducing the frequency, dose, or duration of medications, obtaining samples or generic substitutes, or substituting prescribed drugs with over-the-counter or herbal medications, are also limited.

Furthermore, most of the available evidence in the Canadian context is drawn from the general population, senior population, and patients with chronic diseases, and nothing has been specifically studied in or established for people with disabilities or people belonging to aboriginal communities. Evidence from other countries shows that people with disabilities and those belonging to aboriginal communities are at increased odds of facing CRNA. For example, indigenous patients belonging to aboriginal communities residing in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand were two to three times more likely to report CRNA compared with nonindigenous patients.30 Similarly, studies show that severe disability, poor health status, low income, lack of insurance, and a high use of prescriptions increase the likelihood of people with disabilities of engaging into CRNA.66,67

Recommendations for future research

Future research should explore factors that influence patients’ decisions to alternative medicine regimens due to cost. Also, there is need to explore the experiences of people while managing prescription drugs costs. Only two qualitative studies involved people facing these barriers directly and explored their experiences. These experiences are important to know, because access to necessary prescription medications might have implications that are beyond just health and health care, especially for socially vulnerable and disadvantaged.65 The role of health system governance in ensuring burden-free access to prescription medications for all also needs to be investigated. Research that can analyze the structures (ie, supports, institutions, resources), processes (ie, access, roles, and functions), and outcomes (justice, equality, and service) of provincial health and social policies, and their effect on cost-related access to medicines for people in Canada, is required.68

Study limitations

Our study has certain limitations. One limitation is related to the generalizability of its findings. Given that the study specifically aimed to map the literature from Canada, this study might be helpful for Canadian policymakers to inform future policy directions and alternatives. Additionally, as scoping studies are intended to provide a wide spectrum, that is, quantity and breadth of literature, we did not assess the quality of included studies. Also, we only included articles published in English. Conducting the literature search in French would permit more confident claims regarding the comprehensiveness of the search strategy in this scoping review.

Conclusion

Due to the emerging attention on increasing costs of prescription medications in Canada and incidence of CRNA among Canadians over the past decade, many health care groups, advocacy associations, and health policy researchers have proposed different Pharmacare models for Canada. Findings of this scoping review suggest that what we know about the phenomenon of CRNA might be just the tip of an iceberg. Inquiry on CRNA is insufficient especially among the socially disadvantaged groups such as indigenous population and people with disabilities, as well as its impact on health outcomes and access and utili-zation of other health care services. Future research should look at the effects of health system factors and support from prescribing health care professionals on modifying the cost–adherence relationships for individuals. In summary, more evidence is required to inform whether national Pharmacare can ensure universal, timely, and burden-free access to prescription medications for all or targeted policy efforts are required, balancing the competing influences and demands.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of the doctoral thesis work of Shikha Gupta. Her work is supported through the doctoral studentship awarded by Queen’s University. Sara Guilcher is supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Embedded Clinician Scientist Salary Award on Transitions in Care. The authors would like to thank Mr Atul Jaiswal for helping in the two-stage screening process of the articles.

Footnotes

Author contributions

The paper was prepared by Shikha Gupta, who also conducted the scoping review and analysis. Mary Ann McColl supervised Shikha Gupta and provided substantial contributions to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. Sara J Guilcher and Karen Smith are the subject experts, and senior authors who contributed in revising the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Allin S, Laporte A. Socioeconomic status and the use of medicines in the Ontario public drug program. Can Public Policy. 2011;37(4):563–576. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang KL, Ghali WA, Manns BJ. Addressing cost-related barriers to prescription drug use in Canada. CMAJ. 2013;186(4):276–280. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Law MR, Daw JR, Cheng L, Morgan SG. Growth in private payments for health care by Canadian households. Health Policy. 2013;110(2–3):141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) Prescribed drug spending in Canada, 2016: a focus on public drug programs. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2016. [Accessed June 10, 2017]. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/product-Family.htm?locale=en&pf=PFC3333. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan SG, Law M, Daw JR, Abraham L, Martin D. Estimated cost of universal public coverage of prescription drugs in Canada. CMAJ. 2015;187(7):491–497. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanmartin C, Hennessy D, Lu Y, Law MR. Trends in out-of-pocket health care expenditures in Canada, by household income, 1997 to 2009. Health Rep. 2014;25(4):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewa CS, Hoch JS, Steele L. Prescription drug benefits and Canada’s uninsured. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2005;28(5):496–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan SG, Daw JR, Law MR. Commentary 384. Toronto, ON: C.D. Howe Institute; 2013. [Accessed May 27, 2017]. Rethinking Pharmacare in Canada. Available from: https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed/Commentary_384_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan SG, Boothe K. Universal prescription drug coverage in Canada: Long-promised yet undelivered. Healthcare Management Forum. 2016;29(6):247–254. doi: 10.1177/0840470416658907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demers V, Melo M, Jackevicius C, et al. Comparison of provincial prescription drug plans and the impact on patients’ annual drug expenditures. CMAJ. 2008;178(4):405–409. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost-Related Medication Under-use Among Chronically III Adults: the Treatments People Forgo, How Often, and Who Is at Risk. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1782–1787. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piette JD, Heisler M, Horne R, Caleb Alexander G. A conceptually based approach to understanding chronically ill patients’ responses to medication cost pressures. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(4):846–857. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soumerai SB. Benefits and risks of increasing restrictions on access to costly drugs in Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(1):135–146. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piette JD. Cost-related medication underuse: a window into patients’ medication-related concerns. Diabetes Spectr. 2009;22(2):77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piette JD, Beard A, Rosland AM, McHorney CA. Beliefs that influence cost-related medication non-adherence among the “haves” and “have nots” with chronic diseases. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:389–396. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S23111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner TH, Heisler M, Piette JD. Prescription drug co-payments and cost-related medication underuse. Health Econ Policy Law. 2008;3(Pt 1):51–67. doi: 10.1017/S1744133107004380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cost-Related Medication Underuse: A Window Into Patients’ Medication- Related Concerns. Diabetes Spectrum. 2009;22:77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang JX, Lee JU, Meltzer DO. Risk factors for cost-related medication non-adherence among older patients with diabetes. World J Diabetes. 2014;5(6):945–950. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i6.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blomqvist A, Busby C.Feasible Pharmacare in the Federation: A Proposal to Break the Gridlock C.D. Howe Institute; ebrief 217October 21, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picard A.Pharmacare talk, but still no action The Globe and Mail April 19, 2018Section A:5 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. “Scoping the scope” of a cochrane review. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2011;33(1):147–150. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:15. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law MR, Cheng L, Dhalla IA, Heard D, Morgan SG. The effect of cost on adherence to prescription medications in Canada. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):297–302. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hennessy D, Sanmartin C, Ronksley P, et al. Out-of-pocket spending on drugs and pharmaceutical products and cost-related prescription non-adherence among Canadians with chronic disease. Health Rep. 2016;27(6):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy J, Morgan S. Cost-related prescription nonadherence in the United States and Canada: a system-level comparison using the 2007 International Health Policy Survey in Seven Countries. Clin Ther. 2009;31(1):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ungar WJ, Kozyrskyj A, Paterson M, Ahmad F. Effect of cost-sharing on use of asthma medication in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(2):104–110. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamblyn R, Eguale T, Huang A, Winslade N, Doran P. The incidence and determinants of primary nonadherence with prescribed medication in primary care: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):441–450. doi: 10.7326/M13-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kemp A, Roughead E, Preen D, Glover J, Semmens J. Determinants of self-reported medicine underuse due to cost: a comparison of seven countries. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010;15(2):106–114. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee A, Morgan S. Cost-related nonadherence to prescribed medicines among older Canadians in 2014: a cross-sectional analysis of a telephone survey. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(1):E40–E44. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy J, Morgan S. A cross-national study of prescription nonadherence due to cost: data from the Joint Canada-United States Survey of Health. Clin Ther. 2006;28(8):1217–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotermann M, Sanmartin C, Hennessy D, Arthur M. Prescription medication use by Canadians aged 6 to 79. Health Rep. 2014;25(6):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Després F, Perreault S, Lalonde L, Forget A, Kettani FZ, Blais L. Impact of drug plans on adherence to and the cost of antihypertensive medications among patients covered by a universal drug insurance program. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(5):560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell DJ, King-Shier K, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Self-reported financial barriers to care among patients with cardiovascular-related chronic conditions. Health Rep. 2014;25(5):3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hunter CE, Palepu A, Farrell S, Gogosis E, O’Brien K, Hwang SW. Barriers to prescription medication adherence among homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. J Prim Care Community Health. 2015;6(3):154–161. doi: 10.1177/2150131914560610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Després F, Forget A, Kettani FZ, Blais L. Impact of patient reimbursement timing and patient out-of-pocket expenses on medication adherence in patients covered by private drug insurance plans. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(5):539–547. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.5.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thanassoulis G, Karp I, Humphries K, Tu JV, Eisenberg MJ, Pilote L. Impact of restrictive prescription plans on heart failure medication use. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(5):484–490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.804351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao S, Lix L, Shevchuk Y, Teare G, Blackburn DF. Reduced out-of-pocket costs and medication adherence – a population based study. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2018;25(1):e1–e7. doi: 10.22374/1710-6222.25.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Assayag J, Forget A, Kettani FZ, Beauchesne MF, Moisan J, Blais L. The impact of the type of insurance plan on adherence and persistence with antidepressants: a matched cohort study. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(4):233–239. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anis AH, Guh DP, Lacaille D, et al. When patients have to pay a share of drug costs: effects on frequency of physician visits, hospital admissions and filling of prescriptions. CMAJ. 2005;173(11):1335–1340. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daw JR, Morgan SG. Stitching the gaps in the Canadian public drug coverage patchwork?: a review of provincial pharmacare policy changes from 2000 to 2010. Health Policy. 2012;104(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guilcher S, Munce S, Conklin J, et al. The financial burden of prescription drugs for neurological conditions in Canada: results from the National Population Health Study of Neurological Conditions. Health Policy. 2017;121(4):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldsmith LJ, Kolhatkar A, Popowich D, Holbrook AM, Morgan SG, Law MR. Understanding the patient experience of cost-related non-adherence to prescription medications through typology development and application. Soc Sci Med. 2017;194:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhaliwal KK, King-Shier K, Manns BJ, Hemmelgarn BR, Stone JA, Campbell DJ. Exploring the impact of financial barriers on secondary prevention of heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C, Li Q, Sweetman A, Hurley J. Mandatory universal drug plan, access to health care and health: evidence from Canada. J Health Econ. 2015;44:80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley JA, et al. Adverse events associated with prescription drug cost-sharing among poor and elderly persons. JAMA. 2001;285(4):421–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lexchin J, Grootendorst P. Effects of prescription drug user fees on drug and health services use and on health status in vulnerable populations: a systematic review of the evidence. Int J Health Serv. 2004;34(1):101–122. doi: 10.2190/4M3E-L0YF-W1TD-EKG0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng B, Poulose A, Fulford M, Holbrook A. A pilot study on cost-related medication nonadherence in Ontario. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2012;19(2):e239–e247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Millar WJ. Disparities in prescription drug insurance coverage. Health Rep. 1999;10(4):11–31. (ENG); 9-30(FRE). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kratzer J, Cheng L, Allin S, Law MR. The impact of private insurance coverage on prescription drug use in Ontario, Canada. Healthc Policy. 2015;10(4):62–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanley GE. Prescription drug insurance and unmet need for health care: a cross-sectional analysis. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e178–e183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhong H. Equity in pharmaceutical utilization in Ontario: a cross-section and over time analysis. Can Public Policy. 2007;33(4):487–507. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allin S, Hurley J. Inequity in publicly funded physician care: what is the role of private prescription drug insurance? Health Econ. 2009;18(10):1218–1232. doi: 10.1002/hec.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Law MR, Cheng L, Kolhatkar A, et al. The consequences of patient charges for prescription drugs in Canada: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. 2018;6(1):E63–E70. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20180008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapur V, Basu K. Drug coverage in Canada: who is at risk? Health Policy. 2005;71(2):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luffman J. Out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs. Perspect Lab Income. 2005;6(9):5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 58.McLeod L, Bereza BG, Shim M, Grootendorst P. Financial burden of household out-of-pocket expenditures for prescription drugs: cross-sectional analysis based on national survey data. Open Med. 2011;5(1):e1–e9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simon-Tuval T, Triki N, Chodick G, Greenberg D. Determinants of cost-related nonadherence to medications among chronically ill patients in maccabi healthcare services, Israel. Value Health Reg Issues. 2014;4(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rahimi AR, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, Bernheim SM, Krumholz HM. Financial barriers to health care and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1063–1072. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43(6):521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Piette JD, Wagner TH, Potter MB, Schillinger D. Health insurance status, cost-related medication underuse, and outcomes among diabetes patients in three systems of care. Med Care. 2004;42(2):102–109. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108742.26446.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Atella V, Schafheutle E, Noyce P, Hassell K. Affordability of medicines and patients’ cost-reducing behaviour: empirical evidence based on SUR estimates from Italy and the UK. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2005;4(1):23–35. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200504010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Musich S, Cheng Y, Wang SS, Hommer CE, Hawkins K, Yeh CS. Pharmaceutical cost-saving strategies and their association with medication adherence in a medicare supplement population. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1208–1214. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3196-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kennedy J. Using cost-related medication nonadherence to assess social and health policies. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):168–170. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naci H, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Persistent medication affordability problems among disabled Medicare beneficiaries after Part D, 2006–2011. Med Care. 2014;52(11):951–956. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]