Abstract

Youth living with socially devalued characteristics (e.g., minority sexual orientation, race, and/or ethnicity; disability; obesity) experience frequent bullying. This stigma-based bullying undermines youths’ wellbeing and academic achievement, with lifelong consequences. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommends developing, implementing, and evaluating evidence-based interventions to address stigma-based bullying. To characterize the existing landscape of these interventions, we conducted a systematic review of stigma-based bullying interventions targeting youth in any country published in the peer-reviewed literature between 2000 and 2015. Our analysis was guided by a theoretical framework of stigma-based bullying, which describes stigma-related factors at the societal, structural, interpersonal, and individual levels that lead to stigma-based bullying. We screened 8,240 articles and identified 22 research studies describing 21 interventions addressing stigma-based bullying. We found that stigma-based bullying interventions are becoming more numerous, yet are unevenly distributed across stigmas, geographic locations, and types of organizations. We further found that these interventions vary in the extent to which they incorporate theory and have been evaluated with a wide range of research designs and types of data. We recommend that future work address stigma-based bullying within multicomponent interventions, adopt interdisciplinary and theory-based approaches, and include rigorous and systematic evaluations. Intervening specifically on stigma-related factors is essential to end stigma-based bullying and improve the wellbeing of youth living with socially devalued characteristics.

Keywords: bullying, discrimination, intervention, peer victimization, stigma, youth

Introduction

Youth living with socially devalued identities, characteristics, and attributes [e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (LGBTQ) youth, overweight and obese youth, youth living with disabilities, youth with minority racial and ethnic backgrounds] experience frequent bullying from their peers (Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, & Koenig, 2012). Experiences of bullying, in turn, undermine the academic achievement and wellbeing of youth, with lifelong consequences (Juvonen & Graham, 2014; McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015). In response to growing recognition of the elevated prevalence and harmful consequences of bullying, a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) recommended the development, implementation, and evaluation of evidence-based interventions to address bullying of youth living with socially devalued identities, characteristics, and attributes (i.e., stigma-based bullying; NASEM, 2016). In contrast to non-stigma-based bullying, stigma-based bullying is driven by distinct, stigma-related factors (e.g., social dominance orientation, stereotypes, prejudice); therefore, distinct intervention strategies may be needed to address this form of bullying. To understand the existing landscape of stigma-based bullying interventions targeting youth, we conducted a systematic review of these interventions that have been published in the peer-reviewed literature between 2000 and 2015. Herein, we introduce a theoretical framework of stigma-based bullying that guided this review, describe the results of this review, and present recommendations for future efforts to develop, implement, and evaluate stigma-based bullying interventions.

Bullying, Discrimination, and Stigma-Based Bullying

Research to understand and address stigma-based bullying currently exists in two empirical literatures: the school-based bullying literature and the school-based discrimination literature (NASEM, 2016). Although these literatures define their key constructs in different ways, they often focus on similar phenomena. Bullying is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as unwanted aggressive behavior that involves a power imbalance, is repeated or is likely to be repeated, and may cause harm to the targeted youth (Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Hamburger, & Lumpkin, 2014). Others have also defined bullying as a goal-directed behavior (Volk, Dane, & Marini, 2014). Discrimination is a behavioral manifestation of stigma, or social devaluation and discrediting (Goffman, 1963; Link & Phelan, 2001), that involves the mistreatment of people living with or perceived to live with certain identities, characteristics, or attributes.

Bullying and discrimination share several key similarities and yet are distinct processes. Both may involve aggression, including physical (e.g., hitting), verbal (e.g., name calling), and social (e.g., peer rejection) forms. Both can occur once or repeatedly over time (Gladden et al., 2014; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). Both rely on power imbalances between the perpetrator and target. Moreover, both lead to poorer psychological and physical health outcomes among those who are targeted (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010). Bullying and discrimination are also different in several ways. Unlike discrimination, youth may be targeted by bullying even if they do not have socially devalued identities, characteristics, or attributes. For example, youth who are submissive (i.e., insecure, sensitive) are at increased risk of being bullied regardless of whether they have socially devalued identities, characteristics, or attributes (Juvonen & Graham, 2014). Bullying involves physical and/or social power imbalances whereas discrimination involves social power imbalances. Bullying is a goal-directed behavior, sometimes defined as intentional (Olweus, 1993), whereas discrimination can be intentional or unintentional (i.e., unconscious; Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004). According to the ways in which they are commonly defined in the literature, discrimination occurs at all ages (Link & Phelan, 2001), whereas bullying is most prevalent during childhood and adolescence (Gladden et al., 2014; Rodkin, Espelage, & Hanish, 2015).

Stigma-based bullying (also referred to as bias-based bullying or harassment) represents the overlap between bullying and discrimination, and can be defined as bullying that is motivated by stigma (NASEM, 2016). Stigma-based bullying often involves distinct behaviors, such as sexual harassment directed at girls, homophobic epithets directed at LGBTQ youth and youth presumed to be LGBTQ, or racial slurs directed at racial and ethnic minority youth. Many forms of stigma-based bullying appear to be more common than non-stigma-based bullying. Sexual minority youth and youth with disabilities are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to experience bullying than their heterosexual peers and peers without disabilities, respectively, with bullying disparities lasting from elementary to high school (Rose, Espelage, & Monda-Amaya, 2009; Rose & Gage, 2016; Schuster et al., 2015). Overweight youth also experience more bullying than their peers, with overweight girls being at greatest risk of bullying (Janssen, Craig, Boyce, & Pickett, 2004; Puhl, Peterson, & Luedicke, 2013; Wang, Iannotti, & Luk, 2010). For example, one study suggested that obese girls are 2 times more likely to experience bullying than normal weight girls, whereas obese boys are not more likely than normal weight boys to experience bullying (Janssen et al., 2004).

Evidence comparing bullying experiences of youth of minority races and ethnicities with other youth is mixed, with some studies suggesting that youth of minority races and ethnicities experience less bullying and others suggesting that they experience similar amounts of bullying as youth of majority races and ethnicities (Mueller, James, Abrutyn, & Levin, 2015; Sawyer, Bradshaw, & O’Brennan, 2008). The ways in which bullying is measured may partly explain these differences. In one study, African American youth were less likely than white students to indicate that they were bullied using definition-based measures of bullying but as likely as white students to indicate that they were bullied using behavior-based measures (Sawyer et al., 2008). Moreover, evidence suggests that youth of minority races and ethnicities who do not fulfill stereotypes about their racial and ethnic groups are more likely to be bullied than youth who fulfill stereotypes. For example, African American youth who do not participate in sports and those with higher scores on national tests are more likely to be bullied than their African American peers (Peguero & Williams, 2013).

Some evidence suggests that stigma-based bullying is associated with worse outcomes than non-stigma-based bullying. Drawing on two population-based samples, Russell and colleagues (2012) found that youth who reported stigma-based bullying, including bullying associated with their sexual orientation, race, religion, sex/gender, or disability, were at greater risk of poor mental health (e.g., depression, suicide ideation and attempts), substance use, and low academic achievement than youth reporting non-stigma-based bullying. Moreover, childhood and adolescence may be “sensitive periods” when experiences of stigma-based bullying have a greater effect on wellbeing than discrimination experienced later in life (Gee, Walsemann, & Brondolo, 2012). Evidence that stigma-based bullying is both more common and pernicious than non-stigma-based bullying, and that youth may be particularly vulnerable to experiences of stigma, suggests that special attention is needed to address stigma-based bullying.

Theoretical Framework

We theorize that stigma-based bullying is driven, in part, by distinct stigma-related factors that are not necessarily involved in non-stigma-based bullying (e.g., social dominance orientation, stereotypes, prejudice). To effectively intervene in stigma-based bullying, therefore, it may be necessary to address these factors. We include these factors in our theoretical framework of stigma-based bullying (Figure 1). We adapted our framework from Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1986), as was done with the NASEM bullying report (NASEM, 2016). We conceptualize the individual youth who perpetrate stigma-based bullying as nested within layers of society, structures, and interpersonal relationships, with factors at all of these levels contributing to youths’ perpetration of stigma-based bullying. Different from the model of bullying included in the NASEM bullying report, our framework focuses on factors that lead to stigma-based bullying specifically. Some factors leading to stigma-based bullying may be considered domain-general, in that they may underlie multiple forms of stigma-based bullying (e.g., LGBTQ bullying and disability bullying); others may be considered domain-specific, in that they may drive particular forms of stigma-based bullying (e.g., LGBTQ bullying or disability bullying). Given our scope of coverage of multiple forms of stigma-based bullying, we focus on several key domain-general factors. Finally, stigma-based bullying takes on a variety of forms (e.g., verbal, physical) and affects the academic and health outcomes of targeted youth.

Figure 1.

Stigma-Based Bullying Framework, based on ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1986; NASEM, 2016)

Social stigma

The most distal layer represents stigma, or social devaluation and discrediting, that exists within society (Goffman, 1963; Link & Phelan, 2001). We include several socially devalued characteristics in our framework and acknowledge that there may be other socially devalued identities, characteristics, or attributes possessed by youth that place them at risk for bullying. Stigma is a social construct dependent on context, and some characteristics are more or less strongly devalued in certain social contexts. Therefore, youth living with socially devalued characteristics may be at greater risk of bullying in some social contexts than in others. For example, sexual minority youth are more likely to report bullying if they live in neighborhoods with higher rates of LGBT assault hate crimes (Hatzenbuehler, Duncan, & Johnson, 2015), perhaps due to stronger LGBT stigma in these neighborhoods. Similarly, youth experience more bullying in communities in which they are a member of a racial/ethnic minority group rather than a racial/ethnic majority group (Schumann, Craig, & Rosu, 2013), perhaps due to stronger stigma toward their racial/ethnic group in these communities.

Structural level

The next layer represents the structural level. We identify several structures relevant to stigma-based bullying, including countries, states, schools, classes, religious organizations, and clubs, and acknowledge that there are other structures relevant to stigma-based bullying. Structural stigma manifestations may include policies about bullying and segregation (e.g., racial residential segregation). These factors create and maintain environments and contexts in which stigma-based bullying is more likely to occur. Some states have laws prohibiting bullying on the basis of specific socially devalued characteristics, and these laws are associated with lower rates of bullying. For example, sexual and gender minority youth living in states with laws prohibiting bullying on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity report less bullying (Kosciw, Greytak, Bartkiewicz, Boesen, & Palmer, 2012). Even more locally, sexual minority students in districts whose anti-bullying policies explicitly protect sexual and gender minorities report less victimization than those in districts whose policies are not enumerated in this way (Kull, Greytak, Kosciw, & Villenas, 2016). School policies regarding youth living with socially devalued characteristics may further influence rates of stigma-based bullying. Students with disabilities in schools where they are separated from other students report more bullying than students with disabilities in schools where they are integrated into the school (Rose et al., 2009). Moreover, youth of minority races and ethnicities appear to experience less bullying in schools with high teacher diversity (Larochette, Murphy, & Craig, 2010) and in ethnically homogeneous classes (Vervoort, Scholte & Overbeek, 2010).

Interpersonal level

The most proximal layer represents the interpersonal level, and includes individual people who surround youth perpetrating bullying such as parents, teachers, physicians, coaches, and peers. Individual stigma manifestations are ways in which individual people experience and express social stigma. Dominance and control play central roles in both stigma-based and non-stigma-based bullying, with youth who bully striving to exert power over other youth (Juvonen & Graham, 2014). Yet, youth who engage in stigma-based bullying exert a targeted form of social dominance that reinforces group hierarchies that exist within the larger society. As stipulated within social dominance theory, social dominance orientation refers to an individual’s preference that members of their in-group be superior to or have more social power than members of out-groups (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). There is robust evidence that individuals in dominant positions in society (e.g., those who identify as white, heterosexual) more strongly endorse social dominance orientation beliefs, and that social dominance orientation is associated with stronger prejudice and discrimination toward a range of minority groups (Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Among adolescents, social dominance orientation partially accounts for gender differences in sexual prejudice (Mata, Ghavami, & Wittig, 2010). Further, research suggests that social dominance orientation predicts changes in negative attitudes toward LGBTQ people among youth (Hooge & Meeusen, 2012; Poteat & Anderson, 2012).

Prejudice and stereotypes are manifestations of social stigma, or ways that individuals experience and enact social stigma (Brewer, 2007; Earnshaw, Bogart, Dovidio, & Williams, 2013; Phelan, Link, & Dovidio, 2008). Prejudice is a negative affective orientation toward people living with socially devalued characteristics that can be experienced as an emotion, such as disgust, anger, or fear (Allport, 1954; Brewer, 2007; Phelan et al., 2008). Stereotypes are beliefs about attributions of groups that are applied to individual group members, such as low intelligence, laziness, or promiscuity (Brewer, 2007). The expression of prejudice and content of stereotypes differ by group (Cottrell & Neuberg, 2005; Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002). For example, prejudice toward Black people may involve feelings of fear or anger whereas prejudice toward people with disabilities may involve feelings of pity (Cottrell & Neuberg, 2005).

Social dominance orientation, prejudice, and stereotypes are partly learned by youth from other people (Bigler & Liben, 2007). For example, there is some evidence to suggest that children who are more prejudiced toward racial/ethnic minority groups have parents who are also more prejudiced (Aboud & Amato, 2001), and that the relationship between children’s and parents’ levels of prejudice is stronger when children identify with their parents (Sinclair, Dunn, & Lowery, 2005). Similarly, research documents that educators endorse prejudice and stereotypes about overweight people, and that students are aware of their teachers’ negative perceptions of overweight youth (Puhl & Latner, 2007). Peers also exert a significant influence on engagement in both stigma-based and non-stigma-based bullying (Poteat, 2007; Salmivalli, 2010). Not only do adolescents affiliate with peers who are similar in their engagement in these behaviors, but also they encourage these behaviors among each other and become more similar to one another over time. In addition, various norms within peer groups contribute to and can shape individuals’ engagement in stigma-based bullying (Birkett & Espelage, 2015; Poteat, 2008). Scholars thus have emphasized the need for interventions to focus on peer ecologies and not simply individually targeted intervention approaches (Peets, Pöyhönen, Juvonen, & Salmivalli, 2015; Poteat, 2007; Salmivalli, 2010).

Individual level: Perpetrator

Finally, individual youth who perpetrate stigma may express the same individual stigma manifestations, including social dominance orientation, stereotypes, and prejudice, as their parents, peers, and others with whom they interact. In addition to learning prejudice and stereotypes from others, developmental intergroup theory suggests that children develop prejudice and stereotypes toward social groups as a result of categorizing group members based on salient attributes (e.g., noticing societal labeling of group members and physical differences between group members; Bigler & Liben, 2007). Among adults, research demonstrates that social dominance orientation, stereotypes, and prejudice lead to discrimination in contexts including employment, healthcare, and friendship (Dovidio et al., 2008; Fiske & Stevens, 1993; Kteily, Sidanius, & Levin, 2011). Similarly, among youth, these stigma manifestations motivate stigma-based bullying. As examples, stereotypes about overweight and obese youth (e.g., lazy, socially inept, unhealthy) are associated with lower willingness to engage in social, academic, and recreational activities with overweight and obese youth (Greenleaf, Chambliss, Rhea, Martin, & Morrow, 2006). Prejudice toward sexual minorities is associated with LGBTQ bullying among youth, including use of homophobic epithets (Poteat & DiGiovanni, 2010; Poteat, DiGiovanni, & Scheer, 2013).

Stigma-based bullying

Our framework includes general forms of bullying, including verbal, physical, relational, property damage, and cyberbullying (Gladden et al., 2014), because youth living with socially devalued characteristics may experience these forms of bullying more frequently. We further include examples of stigma-specific forms of bullying, such as homophobic epithets, sexual harassment, and racial slurs, which are particular types of verbal, physical, and relational bullying directed toward youth with socially devalued characteristics. There may be other forms of stigma-specific bullying not captured here.

Individual level: Target

Finally, our framework highlights that stigma-based bullying affects the individual youth who are targeted, including via worse mental and physical health and lowered academic achievement. A robust body of research on the effects of bullying, mostly focused on non-stigma-based bullying, suggests that bullying has long-lasting detrimental effects (NASEM, 2016). Meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that youth who are bullied experience internalizing problems, including greater anxiety and depressive symptoms (Hawker & Boulton, 2000; Reijntjes et al., 2010). Physical health effects of bullying include injuries and psychosomatic problems, such as stomachaches and headaches (Fekkes, 2006; Gini & Pozzoli, 2013; Wang, Iannotti, Luk, & Nansel, 2010). Emerging evidence from neuroscience, neuroendocrinology, and genetics suggests that bullying places youth at risk for life-long health problems via altered biological functioning, including dysregulation of the neuroendocrine response to stress and shortening telomere length (Vaillancourt, Hymel, & McDougall, 2013). Distress resulting from bullying further undermines academic achievement, including worse grades and less school engagement (Juvonen, Wang, & Espinoza, 2010; Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010). As noted above, some evidence suggests that stigma-based bullying is more pernicious, or harmful, than non-stigma-based bullying (Russell et al., 2012).

Bullying and Stigma Interventions

Although research on stigma-based bullying interventions has been limited (NASEM, 2016), interventions have been developed, implemented, and evaluated to address bullying or stigma among youth. To date, bullying interventions typically have not focused on addressing stigma (e.g., their materials do not explicitly address issues of diversity or contain activities directly intended to reduce stereotyping or prejudice) and have not assessed whether they affect stigma-related outcomes, including stigma-based bullying. Similarly, stigma interventions for youth typically do not explicitly focus on addressing bullying and have not assessed whether they affect bullying, instead often targeting outcomes such as stereotypes.

The NASEM bullying report (2016) differentiates among three types of bullying interventions. Universal prevention programs target all youth within a school or community setting, regardless of involvement in or risk for bullying, and are the most popular type of bullying intervention. The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program is a universal program that is perhaps the most popular bullying intervention worldwide (Olweus, 1993). All students in a school are involved in creating rules about bullying, and receive instruction regarding bullying including how to respond to bullying. All teachers and school staff receive training on how to address bullying. Other programs such as KiVa also have been developed and implemented widely (Kärnä et al., 2011). Universal interventions aim to build resiliency among all youth and create supportive school climates to prevent the occurrence of bullying (Juvonen & Graham, 2014). The remaining two types of interventions are more targeted, focusing on youth who are or may become involved in bullying. Selective preventive interventions focus on youth who are at risk of bullying others or being bullied by others, and often involve direct training in social-emotional competence and de-escalation techniques (NASEM, 2016). Indicated preventive interventions focus on youth who are actually involved in bullying others or are being bullied by others, and are often more intensive and individualized than selective preventive interventions (NASEM, 2016). These may address dysfunctional thought patterns, such as hostile attribution biases, among youth bullying others as well as help youth build skills in social-problem solving, communication, and self-control (Juvonen & Graham, 2014). Universal preventive interventions focus on the interpersonal as well as individual perpetrator and individual target levels of our theoretical framework (Figure 1), whereas selective preventive and indicated preventive focus on the individual perpetrator or individual target levels. Our theoretical framework suggests that the factors that lead to stigma-based bullying are multi-level and interactive, and therefore efforts to address stigma-based bullying may be most successful if they target multiple levels.

Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews of bullying interventions have been published in recent years (Cantone et al., 2015; Evans, Fraser, & Cotter, 2014; Jiménez-Barbero, Ruiz-Hernández, Llor-Zaragoza, Pérez-García, & Llor-Esteban, 2016; Merrell, Gueldner, Ross, & Isava, 2008; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). Most analyses focus on universal prevention programs and suggest that interventions, on average, lead to modest reductions in bullying and that many interventions lead to no changes in bullying. They further identify intervention and sample characteristics that are related to reductions in bullying. As examples, interventions targeting youth who are younger than 10 years old appear to be more effective than those targeting older youth (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016). Interventions that involve parents (e.g., parental meetings to provide information and advice about bullying), implement firm disciplinary methods to address bullying, and enhance playground supervision are also effective (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). Evidence regarding the ideal duration of interventions is mixed, with some analyses suggesting that intensive interventions (i.e., lasting 20 hours or more for youth, and 10 hours or more for teachers) are most effective (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011) and other analyses suggesting that programs lasting less than one year are most effective (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016). Promisingly, bullying interventions are becoming increasingly effective, with interventions published since 2007 leading to greater changes in bullying than those published before 2007 (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016).

Compared to reviews of bullying interventions, there are fewer reviews of stigma interventions for youth. The reviews of stigma interventions primarily summarize interventions to address stigma associated with race and ethnicity, and most focus on universal programs that target all students (Aboud et al., 2012; Levy, Shin, Lytle, & Rosenthal, in press; McKown, 2005). Still other efforts have been made to target and reduce bias and stereotypes, though these efforts also have had limited effects and have not been extended to target reductions in stigma-based bullying as one potential result of holding such bias and stereotypes (Bigler & Liben, 1992; Gonzalez, Steele, & Baron, 2017; Vezzali, Stathi, Crisp, & Capozza, 2015). Aboud and colleagues (2012) as well as McKown (2005) identify two popular types of theory-based stigma interventions for youth. Interventions informed by social cognitive theory aim to disrupt information processing among individual youth that gives rise to stigmatizing behavior, such as categorizing individuals into groups and then associating groups with negative beliefs and attitudes, with content typically delivered via instruction or media. Interventions informed by contact theory aim to foster positive intergroup interaction to increase perspective-taking and empathy, reduce anxiety, and ultimately reduce stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Cooperative learning tasks wherein students work in small groups on a shared assignment (e.g., the Jigsaw classroom) have been employed to promote intergroup contact in schools (McKown, 2005). Aboud and colleagues concluded that interventions involving contact, either in person or via media, were somewhat successful in leading to positive changes in attitudes, particularly among youth belonging to racial/ethnic majorities, and that instructional interventions demonstrate promise in reducing stigma (Aboud et al., 2012). Researchers have rarely assessed whether stigma interventions for youth reduce bullying, instead examining whether they reduce stigma-related factors such as prejudice and stereotypes. Our theoretical framework suggests that changes to stereotypes and prejudice may have downstream effects on stigma-based bullying.

Current Review

A small, but growing, number of interventions have been developed in recent years to address various forms of stigma-based bullying. To understand the current landscape of these interventions, including the extent to which they address distinct stigma-related factors described by our theoretical framework, and inform the development of future stigma-based bullying interventions, we conducted a systematic review of stigma-based bullying interventions published in the peer-reviewed literature between 2000 and 2015. Goals of the review were to:

Identify stigma-based bullying interventions reported in the peer-reviewed literature globally between 2000 and 2015.

Characterize the stigma-based bullying interventions to understand commonalities and differences in their focus, approach, and efficacy.

Recommend future directions for the development, implementation, and evaluation of stigma-based bullying interventions.

Material and Methods

We followed the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews (Liberati et al., 2009). We first searched the peer-reviewed scientific literature for articles published in English between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2015. We began the review in 2000 given that previous reviews of the bullying intervention and stigma intervention for youth literatures (e.g., Aboud et al., 2012; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011) uncovered few interventions published before 2000. We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, and EBSCO databases (PsycINFO, ERIC, LGBT Life, Race Relations Abstracts, Urban Studies Abstracts, Women’s Studies International). Articles were eligible for inclusion if they reported on a stigma-based bullying intervention (i.e., an intervention designed to address mistreatment of youth living with socially devalued identities, characteristics, or attributes), a bullying intervention that reported whether it affected stigma-based bullying, or a stigma intervention that reported whether it affected bullying. We searched for interventions that addressed stigma-based bullying among youth through high school, targeting students, school staff, physicians, family members, and community members. Because we aimed to conduct a broad, comprehensive review, we included articles employing any type of intervention and evaluation design, conducted in any country. We used combinations of the following search terms: bully, stigma, bias, prejudice, discrimination; intervention, prevention, program, effect; school, community, clinic, healthcare; race, racial, racism, gay, lesbian, LGBT, LGBTQ, GLBT, homosexual, transgender, sex, sex-based, gender, weight, obese, religion, faith, disability, disable. We supplemented our search with articles identified through other sources (e.g., personal libraries, recommendations).

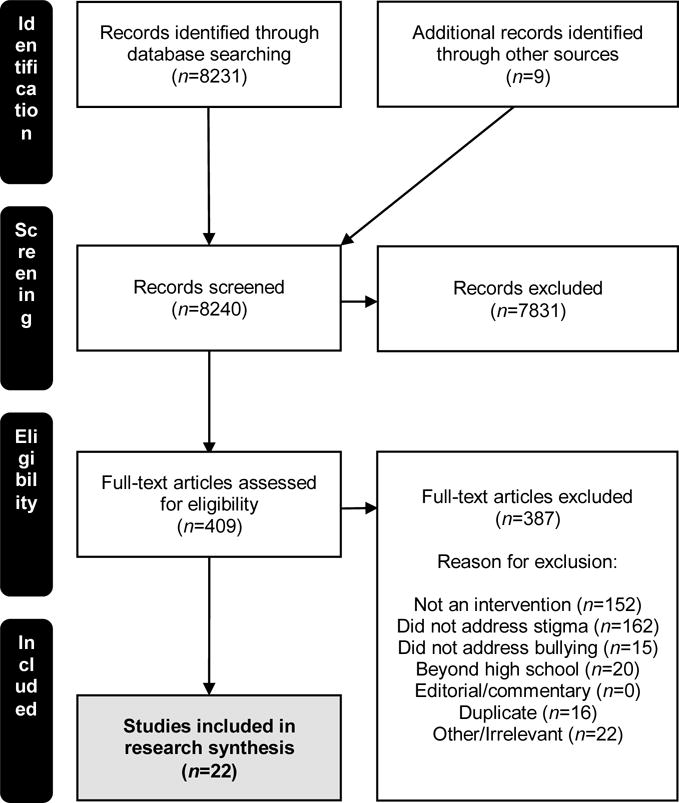

Figure 2 includes the PRISMA diagram depicting the details of the literature search (Liberati et al., 2009). The titles of 8,240 articles were screened, resulting in 409 articles that were assessed for eligibility. We then established reliability for assessing eligibility by having two coders screen 44 of these articles to determine whether each met inclusion criteria for the review (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007). The coders were in full agreement (Kappa=1.00, p<0.001), and one coder continued coding the remaining articles. Articles were excluded because they did not describe an intervention, described an intervention that did not address stigma and bullying, described an intervention targeting individuals beyond high school age, were an editorial or commentary, duplicated another article or intervention included in the search, or were otherwise irrelevant to the review. Several interventions were reported in multiple articles (e.g., one after the first year of intervention and another after multiple years of intervention; Meraviglia, Becker, Rosenbluth, Sanchez, & Robertson, 2003; Sanchez et al., 2001). In these cases, the article was included in the review that reported the most complete and rigorous results (i.e., more outcomes, after a longer follow-up period). One intervention, Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention (SS-SSTP), is represented in the review by two articles because these articles reported on the effect of the intervention on different forms of stigma-based bullying (i.e., LGBTQ and female sex/gender, and disabilities; Espelage, Low, Polanin, & Brown, 2015; Espelage, Rose, & Polanin, 2015). A total of 22 articles were determined to meet inclusion criteria and were retained in the review.

Figure 2.

PRISMA diagram for stigma-based bullying intervention literature search, 2000–2015

Articles fitting inclusion criteria were then coded to extract nine key attributes: (1) Basic article information: the author name, publication date, and intervention title (if applicable). (2) The stigma: the socially devalued identity, characteristic, or attribute that was the focus of the intervention or analysis. (3) The geographic location: the country wherein the intervention took place. (4) Guiding theory of framework: the theoretical basis describing why the intervention was hypothesized to lead to a change in stigma-based bullying. Several articles noted theories that framed their understanding of why stigma-based bullying persists but were unrelated to generating change in stigma-based bullying (e.g., heteronormativity); these theories were not recorded. (5) Intervention program type: following the NASEM definitions, interventions were characterized as universal preventive (i.e., including all youth, teachers, and/or others within a setting), selective preventive (i.e., focusing on youth who are at risk of bullying or being bullied), or indicated preventive (i.e., focusing on youth involved in bullying as perpetrator or target). (6) Target population and sample characteristics: the target population, as defined by the interventionists, as well as the sample characteristics (sample size, type). Teachers and staff or parents were not included as members of the target population if only intervention materials were shared with them (e.g., pamphlets). (7) Intervention overview: a brief description of intervention components. (8) Evaluation design: the design used to evaluate the intervention. (9) Results: a brief summary of the main findings and results of the intervention evaluation, including changes to distinct factors that may drive stigma-based bullying according to our theoretical framework (e.g., prejudice). After coding these nine key attributes, we summarized characteristics of the interventions to understand commonalities and differences across interventions.

Several aspects of risk of bias were assessed using the coding results. Methods for assessing and reporting risk of bias were guided by recommendations by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins & Green, 2011; Higgins et al., 2011). We sought to assess three commonly recognized sources of bias: confounding, selection, and information. Confounding bias occurs when the observed effects can be attributed to something other than the intervention. This was assessed based on whether participants were randomly assigned to intervention vs. control conditions (e.g., participants randomly assigned to intervention vs. control; low risk) or not (e.g., all participants received intervention; high risk). Selection bias results in participants being unrepresentative of a larger population. This was assessed based on whether participants were chosen at random to participate (e.g., whole classroom participated with all students having an equal opportunity to participate; low risk) or were not chosen at random (e.g., students volunteered for study; high risk). Information bias includes issues in how the outcome of interest is measured. This was assessed based on whether evaluations included valid and reliable evaluations (e.g., quantitative measures that are psychometrically valid and reliable, qualitative procedures following standard protocols; low risk) or not (e.g., measures created for the current study, unsystematic qualitative data collection or analysis; high risk).

Results

Table 1 presents key attributes of the 22 articles included in the final review, and Table 2 displays a summary of the characteristics of the stigma-based bullying interventions. The articles describe 21 separate interventions. One intervention, Second Step, was reported in two articles. Both articles were included because they reported on the effects of the intervention on different stigmatized groups [LGBTQ and female sex/gender (Espelage, Low, et al., 2015), and disabilities (Espelage, Rose, et al., 2015)]. This was the only intervention whose effects were tested for multiple stigmas. The remaining 20 interventions addressed one stigma in isolation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of stigma-based bullying interventions, 2000–2015

| Authors (Date) Intervention Title |

Stigma | Country | Guiding Theory or Framework |

Program Type |

Targeted Population Sample Characteristics |

Intervention Overview |

Evaluation Design |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gus (2000) | Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | United Kingdom | None noted | Indicated preventive | Students One 10th grade class | Discussion adapted from Circle of Friends guide and instruction about ASD | Qualitative posttest 1 week after intervention with open-ended written questions | Self-reported more positive attitudes toward and less social rejection of student with ASD in class |

|

Meraviglia, Becker, Rosenbluth, Sanchez, & Robertson (2003) Expect Respect Elementary School Project |

Female sex/gender | United States | None noted | Universal | Whole school N=740 5th grade students; 16% African American, 25% Latino, 59% White N=1,122 staff members in 12 elementary schools; 11% African American, 21% Latino, 65% White |

Implementation of the following components: (1) 12 weekly sessions of student classroom education; (2) staff training; (3) policy and procedure development; (4) parent education via seminars and newsletters; (5) support services for individual students involved in bullying | Schools randomized to intervention or control; Quantitative pretest-posttest | Among students, increased knowledge about sexual harassment but not bullying, and greater awareness of bullying; Among teachers, no differences in knowledge |

| Mpofu (2003) | Physical disabilities (PD) | Zimbabwe | Role salience (role visibility and importance), peer interaction, and academic achievement lead to social acceptance | Universal | Students N=8,342 in 194 classrooms; 11–14 years old; 2.6% with physical disabilities |

3-month classroom-based social enhancement interventions involving (1) role salience (assignment of student with PD to prominent classroom role, e.g., class monitor), (2) peer interaction (students with and without PDs assigned to work together on assignments), or (3) academic support (remediation, tutoring) | Classrooms randomized to 8 conditions including control and combinations of 3 interventions; Quantitative pretest-posttest at 3 and 6 months | Interventions involving role salience increased perceived social acceptance of students with PDs; Effects were stronger when combined with peer interaction and/or academic support |

|

Szalacha (2003) Safe Schools Program for Gay and Lesbian Students (SSP) |

Minority sexual orientation (LGB) | United States | None noted | Universal | Whole schools N=1,646 students in 33 schools; 9th–12th grades; 6.8% sexual minority, 51.9% female, 71.2% White |

Implementation of the following components: (1) develop school policies protecting LGB students from bullying; (2) offer training to school personnel in crisis and suicide intervention; (3) support establishment of Gay-Straight Alliances | Quantitative posttest | Students in schools that implemented more aspects of the SSP reported better sexual diversity climate, including lower reports of bullying |

|

Bauer, Lozano, & Rivara (2007) Olweus Bullying Prevention Program |

Minority race/ethnicity | United States | None noted | Universal | Whole schools N=6,518 in 10 schools; 6th–8th grades; 35.1% White, 23.5% Asian, 15.8% African American, 49.9% female |

Implementation of the following components over one school year: rule setting, staff training, school assembly, student and parent engagement, class discussions, awareness campaign | Nonrandomized controlled trial; Quantitative pretest-posttest; Qualitative assessment of implementation | Reduction of relational and physical bullying among white students in intervention schools but not among students of other races/ethnicities |

| Etherington (2007) | Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | United Kingdom | None noted | Indicated preventive | Students N=6, 8th grade | 6 weekly sessions with 6 students chosen to be peer supporters of student with ASD involving discussion, activities, video partly adapted from Circle of Friends | Qualitative posttest | Reduction of bullying incidents experienced by student with ASD |

|

Beaumont & Sofronoff (2008) The Junior Detective Training Program |

Asperger syndrome (AS) | Australia | Social skills training | Selective preventive | Students with AS N=49; 7.5–11 years; 11.4% female |

8 sessions involving group social skills training, parent training, teacher hand-outs, computer game designed to teach skills in emotion recognition and regulation, and social interaction | Randomized controlled trial; Quantitative pretest-posttest with 6-week and 5-month follow-ups | Generated more ideas regarding how to effectively cope with being bullied at school post intervention and at follow-ups |

| Robertson (2008) | Minority sexual orientation, Minority gender expression and/or identity (LGBT) | United States | None noted | Indicated preventive | Students N=4; 5th grade; 100% boys; 50% African American, 50% Latino |

6 weekly sessions, followed by biweekly sessions for duration of school year led by school psychology students involving activities focused on building social skills, accepting differences, working together, and resolving problems | All students received intervention; Qualitative posttest, focus group with students, interviews with school staff | Reduced bullying of targeted student; Increased students’ abilities to (1) accept individual differences, (2) express feelings, (3) accepting constructive feedback |

|

Taylor (2008) Human Rights/Anti-Homophobia |

Minority sexual orientation (LGB) | Canada | None noted | Universal | Teachers, administrators, and other school staff; N=6,000 + school employees |

Single 2.5 hour workshop for all school employees involving lecture about human rights and homophobia, and policies relevant to LGBTQ bullying; Resource development, including availability of LGBTQ-inclusive books and videos, posters, and anti-homophobia resource guide | None | None noted |

|

DePalma & Atkinson (2009) No Outsiders |

Minority sexual orientation, Minority gender expression and/or identity (LGBT) | United Kingdom | Critical pedagogy, participatory action | Universal | Teachers N=15 teachers in schools located in 3 regions of UK |

Teachers received children’s books, other support materials (e.g., lesson plans), and in-service training on sexualities equality; but given much leeway for implementation | Qualitative, ongoing throughout intervention | None noted |

|

Dessel (2010) Pubiic Conversations Project |

Minority sexual orientation (LGB) | United States | Intergroup dialogue | Universal | Teachers N=36; 80.5% women, 94.4% White, 100% heterosexual |

3 sessions including teachers and LGB community members over 2 weeks involving dialogue guided by manual, stereotype-reduction activities, video and reading materials | Teachers randomized to control or intervention; Mixed-methods pretest-posttest | Increased support of civil rights, more positive feelings about gays and lesbians, greater perspective taking, anticipated greater support of LGBT issues in schools |

|

Payne & Smith (2010) Reduction of Stigma in Schools |

Minority sexual orientation, Minority gender expression and/or identity (LGBTQ) | United States | None noted | Universal | Teachers N=322 teachers who responded to surveys; N=11who responded to open-ended questions |

Single ½-3 hour session involving professional development, with goals to: (1) enhance knowledge of associations between stigma and LGBTQ bullying; (2) provide education and tools for creating positive learning environments; (3) actively create opportunities for dialogue and change to support LGBTQ students. Involves discussion and activities | Mixed-methods posttests | Greater understanding of social stigma experienced by LGBTQ students, and association between stigma and bullying; Increased commitment to intervention |

|

Brinkman, Jedinak, Rosen & Zimmerman (2011) Fairness for All Individuals through Respect (FAIR) |

Female gender | United States | Banks’ educational model for teaching about intersections of identities | Universal | Students N=121 in 6 classrooms; 5th grade; 54.5% girls; 65% White, 23% Latino |

Single 2.5-hour session involving completion of program activities focusing on identifying and challenging gender stereotypes, and practicing responding to gender-based bullying | Classrooms randomized to control or intervention; Mixed-methods pretest-posttest after 1 week | Reduced frequency of gender-based bullying as reported by teachers and students |

|

Vessey & O’Neill (2011) Take a Stand, Lend a Hand, Stop Bullying Now |

Physical, cognitive, and/or emotional disability | United States | Resilience building through creating peer support groups, providing safe environment, teaching social competence | Selective preventive | Students living with disabilities N=65 in 8 schools; 9–14 years old; 66.2% boys; 86.5% White |

12 biweekly sessions conducted by school nurse with support group including viewing webisodes about bullying from campaign, discussing reactions, and completing activities; Stop Bullying Now tip sheets distributed to school staff and parents | Mixed-methods pretest-posttest | Reduced reports of bullying and improved self-concept as reported by students; no differences in global psychosocial functioning as reported by parents |

| Wernick, Dessel, Kulick & Graham (2013) | Minority sexual orientation, Minority gender expression and/or identity (LGBTQ) | United States | Allyhood development, Theater of the Oppressed, community-based participatory research | Universal | Students N=832 in 4 high schools and 3 middle schools; 8th–12th grades; 75% straight/cisgender; 55% White; 53% cisgender men, 40% cisgender women, 7% trans*/genderqueer |

Single ~90-minute session involving (1) arts-based performance including storytelling and sharing climate survey data, (2) common ground activity, (3) post-performance dialogue with audience | Mixed-methods pretest-posttest | Increased self-reported likelihood and confidence in ability to intervene when witnessing LGBTQ bullying |

| Gómez, Munte, & Sorde (2014) | Arab-Muslim, Roma race/ethnicity | Spain | Community involvement | Universal | Whole schools N=2 schools; School 1: 64% immigrant students; 61.2% Moroccan, 11.4% South American, 4.4% Black African, 14.4% Roman; School 2: not reported |

Roma and Arab-Muslim adult men brought into schools, worked with children, role modeled positive cross-race interactions, enrolled in courses | Qualitative fieldwork | Reduced stereotypes and prejudice, greater school retention, reduced bullying |

| Mattey, McCloughan & Hanrahan (2014) | Minority sexual orientation, Minority gender expression and/or identity (LGBT) | Australia | Social norms theory, values-based approaches | Universal | Volleyball players N=Unspecified; 23 years old and younger |

Single 90-minute session, tailored for <15 year olds, 15–17 year olds, and 17–23 year olds involving activities designed to demonstrate stereotyping and exclusion, video clips about bullying, discussion about team values, and instruction on reporting bullying; focus on role models in oldest age group | Quantitative posttest | Perceived learning about consequences of bullying, stereotyping, and importance of not bullying and sticking up for bullying targets |

| Panzer & Dhuper (2014) | Obesity | United States | Social learning theory, cognitive theory | Selective preventive | Obese pediatric patients N=5; 10–12 years old; 60% boys |

6 sessions total; 1 individual session with patient and parent to review bullying experiences, 4 group sessions with patients to teach coping skills (ignoring, engaging in positive self-talk, confronting), and practice skills with role playing; 1 session with parents to review skills | Quantitative pretest-posttest at 2 years | Decreased frequency of bullying and distress in response to bullying, increased use of coping skills among patients |

|

Connolly, Josephson, Schnoll et al. (2015) Respect in Schools Everywhere (RISE) |

Female sex/gender, Non-stigma related bullying | Canada | Peer leadership | Universal | Students N=509 students in 4 schools; 7th–8th grades; 51.4% female; 34.7% South Asian, 20.0% Asian, 12.5% European, 12.5% Middle Eastern, 12.5% African/Caribbean, 7.7% Other |

2 45-minute classroom presentations by youth leaders from local high school; Youth leaders are trained by mental health workers and follow a manual, which they are able to personalize | Cluster-randomized controlled trial; Quantitative pretest-posttest | Increased knowledge about bullying and sexual harassment; Reduction in anxiety; No change in attitudes toward bullying or sexual harassment; No change in bullying or sexual harassment |

|

Espelage, Low, Polanin, & Brown (2015) Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention (SS-SSTP) |

Minority sexual orientation (LGB), Female sex/gender, Non-stigma related bullying | United States | Social-emotional learning | Universal | Students N=3,658 students in 36 schools located in 2 states; 6th–7th grades; 52.2% male; 34.4% African-American, 25.8% Latino, 24.8% White |

28 weekly or semi-weekly lessons through 6th and 7th grades, including instruction, role modeling and activities to promote empathy, emotion regulation, communication skills, and problem-solving strategies | Cluster-randomized controlled trial; Quantitative pretest-posttest at 2 years | Reduction in homophobic victimization and sexual violence victimization in one state; No reductions in bullying perpetration and peer victimization |

|

Espelage, Rose, & Polanin (2015) Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention (SS-SSTP) |

Physical, cognitive, and/or emotional disability | United States | Social-emotional learning | Universal | Students with disabilities N=123 students in 12 schools; 6th–8th grades; 53% female; 53% African-American, 31% White, 6% Latino |

15 lessons through 6th–8th grades, including instruction, role modeling and activities to promote empathy, emotion regulation, communication skills, and problem-solving strategies | Cluster randomized controlled trial; Quantitative pretest-posttest at 2 years | No changes in bullying victimization or physical aggression; Reductions in bullying perpetration |

|

Lucassen & Burford (2015) RainbowYOUTH |

Minority sexual orientation (LGBQ) | New Zealand | None noted | Universal | Students N=229 in 2 high schools, 10 classes; School years 9–10; 12–15 years old; 53.7% boys, 68.1% Pacific ethnicity |

Single 60-minute workshop led by educator involving education about sexual orientation and homophobia, sharing of educator’s coming out story, discussion of how to make school safer for LGB students | Quantitative pretest-posttest | Increased valuing and understanding of LGBQ students |

Table 2.

Summary of characteristics of stigma-based bullying interventions, N=22

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Stigma | ||

| LGBTQ | 10 | 47.6 |

| Disability | 6 | 28.6 |

| Female sex/gender | 3 | 14.3 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 2 | 9.5 |

| Obesity | 1 | 4.8 |

| Country | ||

| United States | 11 | 52.4 |

| United Kingdom | 3 | 14.3 |

| Australia | 2 | 9.5 |

| Canada | 2 | 9.5 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 4.8 |

| Spain | 1 | 4.8 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | 4.8 |

| Theory | ||

| Theory described | 12 | 57.1 |

| None noted | 9 | 42.9 |

| Program Type | ||

| Universal preventive | 15 | 71.3 |

| Selective preventive | 3 | 14.3 |

| Indicated preventive | 3 | 14.3 |

| Targeted Population | ||

| Whole school: 10 and younger | 2 | 9.5 |

| Whole school: 11 and older | 2 | 9.5 |

| Students/youth: 10 and younger | 3 | 14.3 |

| Students/youth: 11 and older | 10 | 47.6 |

| Teachers/administration/school staff | 4 | 19.0 |

| Intervention Duration | ||

| Multiple sessions | 14 | 66.7 |

| Single session | 7 | 33.3 |

| Intervention Components | ||

| Education/skill building | 19 | 90.5 |

| Interaction/contact | 6 | 28.6 |

| Policy development | 3 | 14.3 |

| Other | 6 | 28.6 |

| Evaluation Designs | ||

| Randomized controlled trial | 7 | 33.3 |

| Pretest-posttest | 5 | 23.8 |

| Posttest only | 6 | 28.6 |

| Other | 3 | 14.3 |

| Data Collected | ||

| Quantitative only | 9 | 42.9 |

| Qualitative only | 5 | 23.8 |

| Mixed-methods | 6 | 28.6 |

| None | 1 | 4.8 |

| Results | ||

| Bullying-related behavior | 10 | 47.6 |

| Attitudes | 5 | 23.8 |

| Knowledge | 6 | 28.6 |

| Other | 12 | 57.1 |

| No change | 4 | 19.0 |

| None noted | 2 | 9.5 |

Note: Some percentages do not add to 100 because one intervention counted in more than one category (e.g., Second Step addressed multiple stigmas)

Stigmas Addressed

The interventions addressed bullying of LGBTQ youth, youth with disabilities, female youth, youth of minority races/ethnicities, and obese youth. LGBTQ bullying was the most frequently addressed stigma, with nine interventions. Of the interventions that addressed LGBTQ bullying, four addressed minority sexual orientation bullying (LGBQ) specifically, five addressed both minority sexual orientation and minority gender identity and/or expression bullying (LGBTQ). Interventions addressing both minority sexual orientation and minority gender identity and/or expression bullying (LGBTQ) became more popular over time, with the first intervention published in 2009.

Disability bullying was the second most frequently addressed. Of the five interventions that addressed disability bullying, three addressed bullying of students with autism spectrum disorder specifically; one addressed bullying of students with physical, emotional, and/or cognitive disabilities broadly; and one addressed bullying of students with physical disabilities specifically. Two interventions addressed bullying of female students, with one focused on bullying and sexual harassment (Meraviglia et al., 2003). One intervention addressed racial/ethnic bullying, specifically bullying of Arab-Muslim and Roma students in Spain. One intervention addressed obesity bullying. Two interventions were designed to address bullying in general, yet researchers analyzed whether the intervention reduced bullying among racial/ethnic minority, LGBQ, and female students as well as students with disabilities.

Geographic Locations and Social Contexts

The interventions were implemented in several geographic locations. Thirteen interventions took place in North America, with eleven in the United States and two in Canada. Interventions in North America addressed LGBTQ, disability, female sex/gender, minority race/ethnicity, and obesity bullying. Four interventions were implemented in Europe, including three in the United Kingdom and one in Spain, addressing LGBTQ, disability, and racial/ethnic bullying. Three interventions occurred on the Australian continent, with two in Australia and one in New Zealand, and addressed LGBTQ and disability bullying. One intervention was implemented in Africa (Zimbabwe) and addressed disability bullying. No interventions were found in Asia or South America. Moreover, all interventions except one took place in a school or drew their participants from schools. The one exception took place with volleyball players in the community (Mattey, McCloughan, & Hanrahan, 2014).

Theoretical Frameworks

There was a great deal of variability in the incorporation of theory into the interventions. Twelve of the 21 interventions described at least one theory of change (with some noting multiple theories), and aimed to address LGBTQ bullying, disability bullying, sex/gender bullying, obesity bullying, and racial/ethnic bullying. Nine of the interventions did not include a guiding theory or framework describing how the intervention was hypothesized to address stigma-based bullying. These interventions aimed to address LGBTQ bullying, disability bullying, sex/gender bullying, and race/ethnicity bullying.

Several interventions drew on well-established theories of change from the fields of education and/or social psychology. The most commonly cited theories were related to social and emotional learning (e.g., cognitive-behavioral, social learning theory), with four interventions aiming to address social skills and other social and emotional competencies (Beaumont & Sofronoff, 2008; Espelage, Low, et al., 2015; Espelage, Rose, et al., 2015; Panzer & Dhuper, 2014; Vessey & O’Neill, 2011). Three interventions incorporated intergroup contact theory (Dessel, 2010; Mpofu, 2003; Wernick, Dessel, Kulick, & Graham, 2013). Interaction occurred through collaborative assignments, discussion, and theater. The remaining interventions described a wide range of theories of change. These included critical pedagogy and participatory action (DePalma & Atkinson, 2009); social norms theory (Mattey et al., 2014); development of allies, or people with privilege who speak out against discrimination (Wernick et al., 2013); and Banks’ educational model for teaching about intersections of identities (Brinkman, Jedinak, Rosen, & Zimmerman, 2011). Several interventions described youth or community participation as a framework for changing stigma-based bullying (Connolly et al., 2015; Gómez, Munte, & Sorde, 2014; Wernick et al., 2013). For example, one intervention invited men of Arab-Muslim and Roma backgrounds to participate in their local schools to address racial/ethnic bullying via role modeling (Gómez et al., 2014). One intervention tested competing theories of change, including role salience of youth with disabilities, peer interaction between youth with and without disabilities, and academic support for youth with disabilities (Mpofu, 2003).

Intervention and Implementation Details

All types of interventions defined by the NASEM bullying report (2016) were represented in the review. Fifteen interventions were universal preventive and targeted all individuals within a school or organizational setting. Of those interventions that were universal preventive, seven aimed to reach all youth in a school or organization; four aimed to reach all teachers, with some also reaching staff; three aimed to reach students, teachers and staff, and parents; and one aimed to reach all students, and teachers and staff. These interventions generally focused on preventing bullying. Some researchers described a need for intervention as a response to bullying that had occurred within the school or organization. Three interventions were selective preventive, focusing on youth at risk of experiencing bullying due to living with a disability or obesity. These interventions involved small groups of youth (n=5–65) and focused on building social skills, including appropriate responses to being bullied, and teaching skills for coping with bullying. No interventions focused on specific groups of youth at risk of engaging in stigma-based bullying. Three interventions were indicated preventive and were also implemented with small groups of youth (ranging from 4 students to one class of students, with sample size not reported). All three interventions included youth who had bullied another student, and one of the interventions included the student who was bullied. Goals for these interventions included improving understanding of, attitudes toward, and/or behaviors toward the individual student who was bullied.

Interventions targeting youth spanned elementary through high school-aged participants. Five interventions included youth aged 10 years and younger. Two of the three whole school interventions included the younger youth. Moreover, two of the three interventions addressing sex/gender bullying and the only intervention addressing racial/ethnic bullying occurred with younger youth. One intervention with the younger youth addressed disability bullying and one addressed LGBTQ bullying. Twelve interventions included youth aged 11 years and older. These interventions addressed LGBTQ, disability, female sex/gender, minority race/ethnicity, and obesity bullying. All four interventions targeting teachers, administrators, and/or school staff focused on LGBTQ bullying.

Intervention duration and components varied widely. Fourteen of the interventions involved multiple sessions, spanning two 45-minute sessions to two years in duration. The remaining seven interventions involved a single session. Nineteen of the interventions included some type of education or skill building component, which was achieved via a wide variety of methods including instruction, activities, videos, discussion, play, and performance. Education and skill building was used with youth, teachers, and parents to address all types of stigma-based bullying. Six interventions included generating contact between participants and members of stigmatized groups, which was achieved by working together on activities, discussion, and presentations and performances in which members of stigmatized groups shared their stories. Contact was used with students and teachers to address LGBTQ and disability stigma. Developing school policies to better protect students with stigmatized characteristics was employed in three interventions, which addressed LGBTQ, sex/gender, and racial/ethnic bullying. Finally, six interventions included other types of components, including providing academic support to bullied students, providing support services to bullied students, creating clubs for students with stigmatized characteristics and their allies (i.e., Gay Straight Alliances, which are now increasingly referred to as Genders & Sexualities Alliances), and role modeling of positive behavior by adults and older youth. Many interventions employed multiple strategies, including five that involved education and interaction, and three that involved education and policy development.

Evaluation Designs and Results

The interventions were evaluated with several types of designs and data. Seven interventions were evaluated via a randomized controlled trial, with randomization occurring at the level of the individual [e.g., teachers (Dessel, 2010), students with disabilities (Beaumont & Sofronoff, 2008)], classroom, or school. Evaluations employing randomized controlled trials reported either quantitative data (n=5) or a combination of quantitative and qualitative data (n=2). Five interventions were evaluated with pretest-posttest designs. One of these included controls whereas four did not include controls. They used quantitative data (n=2) or a combination of quantitative and qualitative data (n=3). Six interventions employed a posttest only design. Two of these reported quantitative data, one reported a combination of quantitative and qualitative data, and three reported qualitative data including focus groups, interviews, and open-ended written questions. Two interventions drew on qualitative observations, including fieldwork (DePalma & Atkinson, 2009; Gómez et al., 2014). Four interventions included longitudinal posttests, including after five months (Beaumont & Sofronoff, 2008), six months (Mpofu, 2003), and two years (Espelage, Low, et al., 2015; Espelage, Rose, et al., 2015; Panzer & Dhuper, 2014). One intervention did not include an evaluation and therefore did not report data on its results (Taylor, 2008).

Results suggested that the interventions affected behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge related to stigma-based bullying as well as other outcomes. Nine studies reported changes to behaviors, including lower frequency of bullying (n=8), less behavioral social rejection (n=1; Gus, 2000), and less homophobic and sexual violence victimization (n=1; Espelage, Low, et al., 2015). Five studies reported changes to attitudes, including more positive attitudes or feelings (n=4), and reduced prejudice (n=1; Gómez et al., 2014). Six studies reported changes to knowledge, including knowledge about bullying (n=3), knowledge about stigmatized students (n=2), and knowledge about stigma (n=1; Payne & Smith, 2010). Twelve studies reported other types of outcomes. Some outcomes were related to bullying behaviors (e.g., agreement with the importance of engaging in bystander intervention; Mattey et al., 2014), some were related to responding to bullying (e.g., coping with bullying; Panzer & Dhuper, 2014), and some were indirectly related to bullying (e.g., school retention; Gómez et al., 2014). Thirteen studies reported changes in multiple outcomes. Four studies reported no change in at least one of the outcomes reported, with all four drawing on quantitative data. One study reported reductions in experiences of bullying among students with disabilities but no changes in their psychosocial functioning (Vessey & O’Neill, 2011), one reported greater knowledge about some forms of bullying among students but no changes in knowledge among teachers (Meraviglia et al., 2003), and one reported reductions in bullying in one state but not another (Espelage, Low, et al., 2015) as well as reductions in bullying perpetration but not experiences of victimization (Espelage, Rose, et al., 2015). Two studies did not report outcomes.

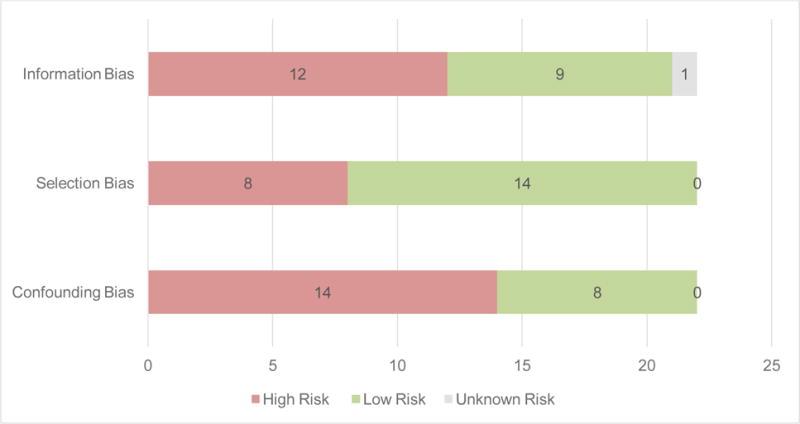

Risk of Bias

The greatest risk of bias observed across studies was confounding, followed by information and selection (see Figure 3). As described above, the majority of interventions were not assessed with randomized controlled designs. For interventions not assessed with randomized controlled designs, it is difficult to determine whether observed effects are due to the intervention or other factors (e.g., changes could be due to discussion of events occurring during the intervention). There was also a pronounced risk of information bias across studies. Many studies using quantitative methods involved measures created for the study rather than previously established valid and reliable measures. Many studies using qualitative methods incorporated unsystematic data collection and/or analysis procedures rather than standard and systematic procedures such as semi-structured protocols to collect data or multiple coders to analyze data. There was a smaller risk of selection bias across studies. Many interventions included all students or teachers in a classroom or school, wherein every individual had an equal probability of being involved in the study, and fewer relied on volunteer samples that may not be representative of the school populations from which samples were drawn.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias in studies assessing stigma-based bullying interventions, N=22

Discussion

Our systematic review of stigma-based bullying interventions published within the peer-reviewed literature highlights trends, gaps, and opportunities to inform future design, development, and evaluation of these interventions. It appears that stigma-based bullying interventions are becoming more numerous: six articles describing stigma-based bullying interventions were published between 2000 and 2007, whereas 16 were published between 2008 and 2015. The introduction of more of these interventions in recent years parallels increasing research evidence that stigma-based bullying is more common and more harmful than non-stigma-based bullying (Janssen et al., 2004; Rose et al., 2009; Russell et al., 2012; Schuster et al., 2015). Intervention design and development can continue to benefit from integrating the best available science concerning the effects of stigma-based bullying and potential mitigating mechanisms that can be harnessed to improve youth outcomes.

We found that LGBTQ and disability bullying have been the most frequently addressed types of stigma-based bullying. The relative popularity of interventions to address these stigmas may be the result of underlying societal shifts. For example, in the U.S. there has been increasing momentum to achieve equality in civil rights among LGBTQ people (e.g., same-sex marriage) and address factors that lead to health inequities among LGBTQ people (e.g., Institute of Medicine report in 2011 with calls to promote the health of LGBTQ people; Institute of Medicine, 2011). Many of these stigma-based bullying interventions have focused on LGB bullying. Yet, there appears to be a trend toward addressing both minority sexual orientation and minority gender expression and identity within these interventions. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 requires that children with disabilities receive education in the least restrictive environment possible; therefore, there has been a movement toward including children with disabilities in general education classrooms. It is possible that this shift has inspired a focus on addressing disability bullying.

Interventions to address sex/gender and racial/ethnic bullying were less numerous. The current review did not include interventions designed to reduce stereotypes and prejudice associated with sex/gender and race/ethnicity for youth (Aboud et al., 2012; Kim & Lewis, 1999) because these interventions did not specifically aim to address bullying. Yet, it is possible that they reduce stigma-based bullying and future research should explore this possibility. One study included in this review reported that a general bullying intervention, the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program, reduced bullying among white students but not students of minority races and ethnicities (Bauer et al., 2007). This suggests that bullying interventions that do not address distinct stigma stigma-related factors may not successfully address racial/ethnic bullying. A global survey of 100,000 youth in 18 countries found that 25% who reported being bullied attributed it to their ethnicity or national origin, highlighting that interventions to address this form of bullying may be needed in many contexts around the world (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2017). Only one intervention addressed obesity bullying, yet obese youth frequently experience bullying (Janssen et al., 2004; Puhl et al., 2013; Wang, Iannotti, & Luk, 2010) and recommendations to address obesity bullying have existed for years (Puhl & Latner, 2007). We did not find interventions addressing other forms of stigma-based bullying, such as bullying related to religion, socio-economic status, or immigration. Additionally, most interventions addressed one stigma in isolation rather than intervening on multiple stigmas simultaneously. Second Step was an exception to this: Researchers examined whether the intervention reduced LGBTQ, disability, and sex/gender bullying (Espelage, Low, et al., 2015; Espelage, Rose, et al., 2015). Nevertheless, it should be noted that this program was not designed to reduce stigma, but rather researchers considered whether this general social emotional learning program could reduce several forms of stigma-based bullying.

Our review suggests that stigma-based bullying interventions are concentrated in certain geographic locations and social contexts. The majority were implemented in North America, with most in the United States, and in Europe, with most in the United Kingdom. No stigma-based bullying interventions were found in Asia or South America, and few were found in Africa, Australia, or in Europe outside of the United Kingdom. This may be problematic to the extent that bullying of youth with socially devalued characteristics is unaddressed, or at least such interventions have gone unreported in these locations. For example, LGBTQ stigma is particularly strong in some areas of Africa, Asia, Latin America and Oceania, where laws prohibit same-sex sexual behavior (Carroll, 2016), and bullying of sexual and gender minority youth in these countries may be pronounced. Moreover, racial/ethnic bullying may be prevalent in countries that are receiving racial/ethnic minority immigrants from around the world (Jansen, Mieloo, Domisse-van Berkel, Verlinden, & van der Ende, 2016; Maynard, Vaughn, Salas-Wright, & Vaughn, 2016). All but one intervention addressed bullying in schools. Yet, stigma that is manifested within structures beyond school systems (e.g., extracurricular clubs, religious settings) and individuals who are not involved in schools (e.g., religious leaders, physicians) may influence the extent to which youth endorse social dominance orientation, stereotypes, and prejudice. This suggests that stigma-based bullying will continue as long as social stigma, and its manifestations at the structural and interpersonal levels, persists. Expanding the geographic regions and social contexts in which stigma-based bullying interventions are implemented is recommended.

Most stigma-based bullying interventions have been designed for youth aged 11 years and older. Yet, research suggests that bullying is prevalent among elementary-aged youth (Juvonen & Graham, 2014) and that bullying interventions are more effective with younger youth (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016). Moreover, theory suggests that it is important to address stereotypes and prejudice during early developmental periods (Bigler & Liben, 2007). We found that certain stigmas were mostly addressed with younger or with older youth. For example, sex/gender and racial/ethnic bullying were more frequently addressed with younger youth, and LGBTQ bullying was almost exclusively addressed with older youth. Similarly, all interventions targeting adults addressed LGBTQ bullying. This highlights the need for researchers and interventionists to address developmental gaps when generating and testing the effectiveness of programs that address these and other forms of stigma-based bullying. It is particularly important to intervene on LGBTQ bullying at an earlier age given research that characterizes developmental milestones for sexual identity at early ages, such as first becoming aware of same-gender attraction (D’augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2008; Katz-Wise et al., 2016; Martos, Nezhad, & Meyer, 2015). In addition, interventions that simultaneously address sex/gender and LGBTQ bullying are especially warranted for gender diverse, genderqueer, transgender, or gender nonconforming youth (Reisner, Greytak, Parsons, & Ybarra, 2015). Similarly, it is important to address racial/ethnic bullying among older youth and with teachers and other adults.

A gap in intervention research is the inconsistent utilization of theory as the basis for intervention. Despite increasing evidence that suggests that public health interventions based in social and behavioral science theories are more effective than those not based in a specific theoretical framework (Glanz & Bishop, 2010), many articles in this review did not describe a theoretical framework for how the intervention was hypothesized to lead to a change in stigma-based bullying. Several articles that described a theoretical framework drew on well-established theories from education and social psychology, including those of social and emotional learning and intergroup contact. The goal of social and emotional learning interventions is to promote self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making to ultimately improve positive adjustment and academic success (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011). Meta-analytic evidence suggests that social and emotional learning interventions improve social and emotional skills, attitudes, behavior, and academic performance (Durlak et al., 2011). Intergroup contact theory is also supported by meta-analytic evidence and suggests that interpersonal contact reduces prejudice by enhancing knowledge about, reducing anxiety regarding, and increasing empathy toward members of outgroups (e.g., youth with socially devalued characteristics; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008).

Future stigma-based bullying interventions might also benefit from incorporating theoretical frameworks from other disciplines. Several social and behavioral science theories have been shown to be efficacious in public health interventions (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008; Rogers, 2010). As examples, applying a transtheoretical model of health-related behaviors, stigma-based bullying interventions could target specific stages of change with different components, such as helping teachers to progress from preparation (being ready to intervene on stigma-based bullying) to action (making specific modifications to their behaviors to intervene). Social marketing intervention components could use a diffusion of innovations framework to spread anti-stigma messaging. Stigma-based bullying requires public health intervention; thus, applying well-tested social and behavioral science theories may improve interventions to address stigma-based bullying in youth.