Overdiagnosis was well recognized in the second half of the 20th century from the advent of widespread screening for cancers.1,2 However, overdiagnosis has received much more widespread attention by health care providers and policy makers in the 21st century following the seminal writings by Welch and Black.3 Initially, there was astonishment that diagnosis of a disorder such as cancer might not be of benefit.

Overdiagnosis remains a difficult concept to communicate to the public, most of whom are unaware of the issue.4 The public, and many in the medical profession, are attuned to the idea that prevention is better than cure. Furthermore, overdiagnosis creates a self-affirming positive cycle. If individuals who were not destined to die in the measured follow-up time are included in survival statistics, the survival rate is inflated—a misleading consequence of overdiagnosis. In turn, this apparent improvement in survival rate encourages more testing of others and more overdiagnosis.5

It is extremely important to recognize and increase awareness of the phenomenon of overdiagnosis, as it is one of the most common and unavoidable consequences of screening and early detection of any disorder. Overdiagnosis should, therefore, be an essential component of background information discussed with individuals who are contemplating screening as part of shared decision making. It should also be considered before any diagnostic test is ordered.

Patient case scenarios

Case 1.

Linda is a 74-year-old woman with right-sided hemiparesis after a stroke. She was diagnosed with a small breast cancer after screening mammography a year ago. She underwent a lumpectomy and radiation therapy. Linda believes that mammography saved her life and becomes a breast cancer screening advocate. For the past year, she has been telling her 50-year-old daughter Sarah to undergo mammography. Your colleague, who is their physician, is just back from a conference and wonders if Linda was diagnosed with a cancer that was not destined to alter her life if it had remained undetected (ie, was she overdiagnosed?). He brings up the cases for discussion at monthly rounds in your group practice.

Case 2.

Gerald is a 65-year-old man who presents for a periodic health examination at the request of his wife. He states that he feels well and has no specific health issues or complaints. He is currently working and he participates in a variety of outdoor activities. During the examination you mention the possibility of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) with ultrasound as part of routine investigations. Gerald agrees to your suggestion. Gerald subsequently returns for follow-up discussion of the results of his abdominal ultrasound, which revealed a 33-mm AAA. Gerald expresses feelings of disappointment, anxiety, and apprehension regarding his diagnosis. He indicates that he is worried that he could suddenly die and that he could be a risk to other individuals. Gerald subsequently alters his lifestyle to reduce physical activity, retires from work, and reduces his plans to travel. He undergoes yearly ultrasounds that show minimal increase in size of his AAA. Gerald dies at age 85 from an unrelated medical condition.

Definition

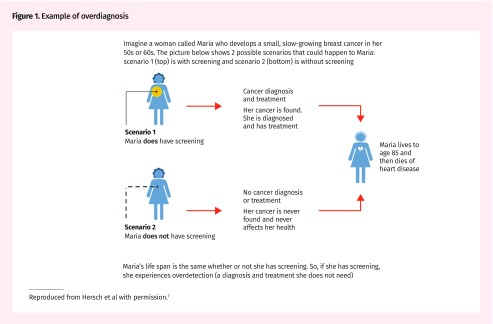

Overdiagnosis refers to the diagnosis of a condition that otherwise would not have caused symptoms or death.6 In other words, it is the detection of a condition without any possible benefit of early treatment to the person with the condition (Figure 1).7

Figure 1.

Example of overdiagnosis

Reproduced from Hersch et al with permission.7

What is not overdiagnosis?

Misdiagnosis and false positives are related but distinctly different concepts. Misdiagnosis is an incorrect diagnosis of a condition, often owing to lack of diagnostic specificity—for example, cellulitis when a patient has swelling and redness of the great toe owing to gout. False positives occur when an initial test result is positive for an abnormality, such as microcalcification seen on mammography, but a follow-up test (eg, biopsy) result reveals no disease. Misdiagnosis and false positives can also lead to harms due to subsequent investigations and unnecessary treatment.

Consequences

Overdiagnosis can lead to serious harms—psychological and behavioural effects of labeling; consequences of subsequent testing (including invasive tests), treatment, and follow-up; and financial effects on the individual who is overdiagnosed and on society. Overtreatment following overdiagnosis can lead to clinically important consequences, including death from the side effects of treatment—for example, sepsis in a patient undergoing chemotherapy for treatment of an overdiagnosed cancer. Higher rates of myocardial infarction and suicide have been reported in men with prostate cancer in the year after diagnosis.8,9

Overdiagnosis is self-perpetuating. Those who might have been overdiagnosed, such as Linda, encourage others to undergo testing without considering the potential harms of testing and subsequent workup or treatment.

Prerequisites

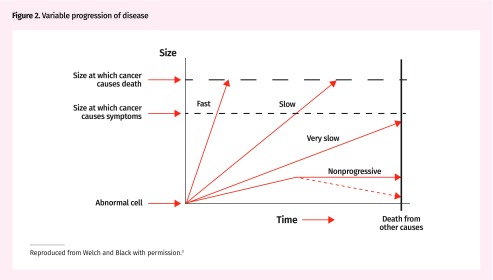

Overdiagnosis is much more likely to occur in conditions with heterogeneous progression, including those with very slow or no progression to symptoms or death (Figure 2).3 Also essential for overdiagnosis is a test that detects the condition in the early asymptomatic state. To be effective, screening requires a long asymptomatic phase and a test to detect the condition during that time. As not all individuals with an asymptomatic condition will ever become symptomatic, overdiagnosis is inherent to any form of effective screening. The proportion of overdiagnosed cases differs for each disease (Table 1).10–18

Figure 2.

Variable progression of disease

Reproduced from Welch and Black with permission.3

Table 1.

Examples of medical conditions often overdiagnosed, by pathway to overdiagnosis

| CLINICAL INTERVENTION | DIAGNOSIS | EXTENT OF REPORTED OVERDIAGNOSIS | HARMS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidentalomas | |||

| • Thyroid imaging | Thyroid cancer | 75% of thyroid cancer cases in Canada have been estimated to be overdiagnosed10 | Surgery and its complications |

| • Abdominal CT | Renal cancer | The incidence of renal cancers in the United States has been reported to be related to the abdominal CT rate11 | Treatment of harmless tumours11 |

| Widened disease definitions | |||

| • Lowered target for treatment and threshold for initiating treatment | Hypertension | SPRINT reported improved cardiovascular outcomes with more intensive 120 mm Hg systolic blood pressure targets12 but with increased side effects. The intensive strategy did not achieve a net clinical benefit13 | Treatment causes hypotension and other side effects. Be cautious about extending “tight control” to patients with hypertension and perhaps restrict to those at higher cardiovascular risk |

| • Cognitive screening tests | Dementia | “The current prevalence of dementia is thought to be 10–30% in people over the age of 80, but the adoption of new diagnostic criteria will result in up to 65% of this age group having Alzheimer’s disease diagnosed and up to 23% of non-demented older people being diagnosed with dementia”14 | “Unnecessary investigation and treatments with side effects; adverse psychological and social outcomes; and distraction of resources and support from those with manifest dementia in whom need is greatest”14 |

| Screening-detected overdiagnosis | |||

| • Papanicolaou tests in women < 25 y | Cervical “precancers” that mostly resolve | 10% or more of women < 25 y have abnormal test results15 | Increased anxiety, referral, colposcopy, biopsy |

| • PSA test | Prostate cancer | 33.2% of prostate cancers were overdiagnosed in the ERSPC trial,16 and 50.4% of cancers detected by screening during the screening phase were overdiagnosed17 | Disease labeling and overtreatment, including unnecessary surgery |

| • Abdominal ultrasound | AAA | 49 per 10 000 screened men were reported to be overdiagnosed, while 2 per 10 000 would avoid death from AAA18 | Labeling; surveillance; 19 per 10 000 will have unnecessary surgery18 |

AAA—abdominal aortic aneurysm, CT—computed tomography, ERSPC—European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer, PSA—prostate-specific antigen,

SPRINT—Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial.

Factors leading to increasing overdiagnosis

Increased rates of testing (increased frequency or wider use of the test in low-risk groups), implementation of higher-sensitivity tests, physician or patient desire to not miss a diagnosis, widened disease definitions (eg, lower threshold for diabetes diagnosis), and financial incentives (eg, payment for increased testing or screening referral) can all lead to increased overdiagnosis.19

Overdiagnosis can arise when criteria for a disease are modified to include more individuals. This is often done without confirmation of benefit for a substantial portion of those labeled with the disease based on the new definitions.20

Increasing use and overuse of tests can lead to detection of unrelated incidentalomas, a version of overdiagnosis. For example, increasing use of imaging tests (eg, computed tomography [CT] scans, including CT colonography) leads to detection of unrelated asymptomatic conditions such as renal carcinoma or a small aortic aneurysm.11 Consequently, it was demonstrated recently that nephrectomies were linked to the number of scans done, not to the actual incidence of renal cancer. Overtreatment through surgery is now recognized to be one of the risks of excessive CT imaging.

Overdiagnosis can also occur when there is concurrent disease that leads to death and the overdiagnosed disease would not have had time to progress to being symptomatic, as is likely for both the cases described above.

Not limited to cancer screening and detection

Although first described in the setting of cancer diagnosis, overdiagnosis can occur with many conditions,21 especially those that have a long indolent phase. Nevertheless, more studies on overdiagnosis have focused on cancer diagnosis than other conditions.

Determining a diagnosis that has clinical consequences and mitigating overdiagnosis

Unfortunately, science has not advanced enough to be able to distinguish whether a condition in a particular individual will lead to clinical consequences. However, attempts are being made to distinguish very slowly progressive or nonprogressive versions of different conditions, as they are more likely to represent overdiagnosis and could be followed up without any treatment.5 Examples include the recent recognition and increase in surveillance without treatment of low-risk prostate cancers and ongoing studies to determine when breast DCIS (ductal carcinoma–in situ) can be followed without treatment.22 There are proposals to remove the word cancer from the naming of low-grade and premalignant neoplasms and instead reclassify them as indolent lesions of epithelial origin.23

Overdiagnosis is real and common

It is expected that the intervention arms of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of screening would initially demonstrate higher detection and incidence rates. If this were all due to early detection of diseases, it should lead to equivalent decreased incidence later on. In addition, there should be a concomitant decreased incidence of advanced disease. Also, if the screening intervention detects precancer conditions and prevents development of cancers or disease, then there would be an overall reduction in cumulative incidence of the disease.24 Thus, if there were no overdiagnosis, after a long enough follow-up, the overall incidence of cases would be the same in both groups or decreased in the screening group. The Canadian National Breast Screening Study demonstrates that the cumulative increased incidence in the screening and intervention arm usually persists without a later decrease in incidence even when long-term follow-up is available; this is an example of overdiagnosis in the screened group.25 Detecting pre-disease or early disease and changing the outcome is the goal of screening. Unfortunately, there is always a balance between cases in which it might be possible to change the outcome and overdiagnosed cases where we are causing harm.

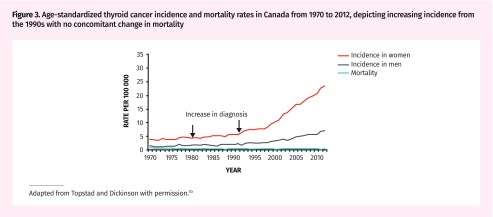

The pattern in clinical practice most frequently seen and indicative of overdiagnosis is when trends over time demonstrate an increasing incidence, especially of early-stage disease with no or minimal progression to serious disease (ie, advanced disease or cause-specific mortality). As an example, thyroid ultrasound became available in 1980. The incidence of thyroid cancer has been increasing in Canada since the early 1990s, with minimal reduction in mortality due to thyroid cancer (Figure 3).10 This pattern suggests overdiagnosis due to diagnostic testing.

Figure 3.

Age-standardized thyroid cancer incidence and mortality rates in Canada from 1970 to 2012, depicting increasing incidence from the 1990s with no concomitant change in mortality

Adapted from Topstad and Dickinson with permission.10

Estimates of extent

The extent of overdiagnosis is estimated from follow-up within RCTs, observational studies (such as ecological studies and trends of incident diagnosis and concomitant death over time), and modeling studies.26 Each method has limitations. For RCTs, estimates require long-term follow-up (which might not be available) and assessment under ideal experimental settings. Ecological studies are vulnerable to unidentified confounding. There are many assumptions made for input variables in modeling studies. Indeed, all study designs make inherent assumptions, which lead to varying estimates.

In addition, estimates vary because different formulas are used to calculate overdiagnosis. As an example, a review on prostate-specific antigen screening for prostate cancer17 used 2 different denominators: all screening-detected prostate cancers during the screening phase of the trials, and prostate cancers diagnosed overall, with the numerator for both calculations being the excess number of cancer cases diagnosed as determined during long-term follow-up. The first approach estimated the percentage of overdiagnosed screening-detected cancers to be 50.4% in the ERSPC (European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer) trial. The second approach estimated the percentage of all cancer cases that were overdiagnosed to be 33.2% in the ERSPC trial. Other studies have used incident cases in the unscreened group as the denominator; this approach leads to higher overdiagnosis estimates compared with using the higher number of cancers diagnosed in the screened groups as the denominator. The lowest estimates are obtained when the entire screened population is used in the denominator.27,28

There is ongoing debate on the best method to measure overdiagnosis.27,28 Currently, it is recommended to quote the range of magnitude of overdiagnosis, the denominator used, and the method of estimation used.

Suggestions for family physicians

Family physicians should discuss the possibility of overdiagnosis in shared decision making. Overdiagnosis can harm patients; therefore, it needs to be discussed with patients before they enter the cascade of screening. A study from Australia reported that more than 90% of women who had mammography and 82% of men who had prostate-specific antigen screening were not informed of the issue of overdiagnosis. When this concept was explained to patients, a large percentage considered this information crucial to decision making.29 When women aged 48 to 50 were informed of the possible extent of overdiagnosis, they were much less likely to undergo mammographic screening.7 Explaining the concept of overdiagnosis is difficult because it is inherently counterintuitive. Stating this up front and using the image of a turtle to explain that some cancers progress slowly can be helpful to foster understanding. An example of such an approach can be found in “The Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) Test” video by Dr Mike Evans.30

A recent review has described public health efforts to counter the drivers of overdiagnosis, which is worthwhile reading.31

Returning to our cases

Case 1.

It is very difficult to explain the concept of overdiagnosis to individuals who believe they benefited and survived because of screening, even though they were likely overdiagnosed. So, you might not want to approach the issue with Linda. But, more important, Sarah has not been screened yet and should be informed of the potential benefits and harms of screening. Our role is to help her arrive at a decision congruent with her values and preferences after providing the known evidence of potential benefits and harms. What would be sad would be for her to make a decision without the pertinent information and without the chance to reflect on her values and preferences toward that type of screening.

Case 2.

Clearly Gerald was overdiagnosed with AAA and suffered the harms of overdiagnosis. Although traditionally 30 mm has been used as the cutoff for diagnosis of AAA, there have been suggestions to lower the threshold of AAA diagnosis, which might tip the balance of AAA screening to net harm.32 It is important to discuss the potential benefits and harms, including that of overdiagnosis, before implementing weak recommendations such as those for AAA screening.

Conclusion

Overdiagnosis is inherent in most screening and diagnostic activities. The magnitude varies for different disorders. The possibility of overdiagnosis should be considered in clinical decision making before ordering any screening or diagnostic tests, and it is important to communicate the possibility of overdiagnosis in shared decision making before individuals enter the screening cascade.

Key points

▸ Overdiagnosis refers to the diagnosis of a condition that otherwise would not have caused symptoms or death. It is an inevitable consequence of screening and diagnostic testing, and can result from increased sensitivity of diagnostic tests or excessively widened disease definitions.

▸ Harms from overdiagnosis occur because of unnecessary diagnostic tests, treatments, and follow-up from which the patient does not receive any benefit.

▸ Estimates of overdiagnosis can vary owing to differences in the methods and sources used to compute rates.

▸ Shared decision making between patients and physicians supported by well-designed decision aids is recommended to minimize the harms associated with overdiagnosis.

Footnotes

Suggested additional reading

1. Welch HG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosed. Making people sick in the pursuit of health. Boston, MA:Beacon Press; 2011.

2. Pathirana T, Clark J, Moynihan R. Mapping the drivers of overdiagnosis to potential solutions. BMJ 2017;358:j3879. Epub 2017 Aug 6.

3. Brodersen J, Schwartz LM, Heneghan C, O’Sullivan JW, Aronson JK, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosis: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ Evid Based Med 2018;23(1):1-3.

4. Too much medicine [collection]. London, Engl: BMJ Publishing Group; 2018. Available from: www.bmj.com/specialties/too-much-medicine. Accessed 2018 Jul 24.

Competing interests

All authors have completed the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ Unified Competing Interest form (available on request from the corresponding author). Dr Singh reports grants from Merck Canada, personal fees from Pendopharm, and personal fees from Ferring Canada, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de septembre 2018 à la page e373.

References

- 1.Feinleib M, Zelen M. Some pitfalls in the evaluation of screening programs. Arch Environ Health. 1969;19(3):412–5. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1969.10666863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox MS. On the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. JAMA. 1979;241(5):489–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(9):605–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099. Epub 2010 Apr 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghanouni A, Meisel SF, Renzi C, Wardle J, Waller J. Survey of public definitions of the term ‘overdiagnosis’ in the UK. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010723. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebell M, Herzstein J. Improving quality by doing less: overdiagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(3):162–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch HG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosed. Making people sick in the pursuit of health. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hersch J, Barratt A, Jansen J, Irwig L, McGeechan K, Jacklyn G, et al. Use of a decision aid including information on overdetection to support informed choice about breast cancer screening: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9978):1642–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60123-4. Epub 2015 Feb 18. Erratum in: Lancet 2015;385(9978):1622. Epub 2015 Mar 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fall K, Fang F, Mucci LA, Ye W, Andrén O, Johansson JE, et al. Immediate risk for cardiovascular events and suicide following a prostate cancer diagnosis: prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(12):e1000197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000197. Epub 2009 Dec 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang F, Keating NL, Mucci LA, Adami HO, Stampfer MJ, Valdimarsdóttir U, et al. Immediate risk of suicide and cardiovascular death after a prostate cancer diagnosis: cohort study in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(5):307–14. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp537. Epub 2010 Feb 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Topstad D, Dickinson JA. Thyroid cancer incidence in Canada: a national cancer registry analysis. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(3):E612–6. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welch HG, Skinner JS, Schroeck FR, Zhou W, Black WC. Regional variation of computed tomographic imaging in the United States and the risk of nephrectomy. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):221–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. Epub 2015 Nov 9. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2017;377(25):2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi G, Jamil A, Jamil U, Balouch MA, Marszalek J, Kahe F, et al. Effect of intensive versus standard blood pressure control on major adverse cardiac events and serious adverse events: a bivariate analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2018 Apr 10; doi: 10.1080/10641963.2018.1462373. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Couteur DG, Doust J, Creasey H, Brayne C. Political drive to screen for pre-dementia: not evidence based and ignores the harms of diagnosis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5125. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickinson JA, Ogilvie G, Van Niekerk D, Popadiuk C. Evidence that supports policies to delay cervical screening until after age 25 years. CMAJ. 2017;189(10):E380–1. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Zappa M, Nelen V, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2027–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. Epub 2014 Aug 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenton JJ, Weyrich MS, Durbin S, Liu Y, Bang H, Melnikow J. Prostate-specific antigen-based screening for prostate cancer: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1914–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson M, Zahl PH, Siersma V, Jørgensen KJ, Marklund B, Brodersen J. Benefits and harms of screening men for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Sweden: a registry-based cohort study. Lancet. 2018;391(10138):2441–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ioannidis JPA. Diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines and in the real world. JAMA. 2018;319(2):115–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenniskens K, de Groot JAH, Reitsma JB, Moons KGM, Hooft L, Naaktgeboren CA. Overdiagnosis across medical disciplines: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018448. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanbayashi C, Iwata H. Current approach and future perspective for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47(8):671–7. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx059. Epub 2017 May 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B, Nelson P, Ransohoff DF, Welch HG, et al. Addressing overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: a prescription for change. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(6):e234–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70598-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkin W, Wooldrage K, Parkin DM, Kralj-Hans I, MacRae E, Shah U, et al. Long term effects of once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening after 17 years of follow-up: the UK Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1299–311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30396-3. Epub 2017 Feb 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baines CJ, To T, Miller AB. Revised estimates of overdiagnosis from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. Prev Med. 2016;90:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.033. Epub 2016 Jun 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter JL, Coletti RJ, Harris RP. Quantifying and monitoring overdiagnosis in cancer screening: a systematic review of methods. BMJ. 2015;350:g7773. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies L, Petitti DB, Martin L, Woo M, Lin JS. Defining, estimating, and communicating overdiagnosis in cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):36–43. doi: 10.7326/M18-0694. Epub 2018 Jun 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter SM, Rogers W, Heath I, Degeling C, Doust J, Barratt A. The challenge of overdiagnosis begins with its definition. BMJ. 2015;350:h869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moynihan R, Nickel B, Hersch J, Beller E, Doust J, Compton S, et al. Public opinions about overdiagnosis: a national community survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans M. The prostate specific antigen (PSA) test. YouTube; 2014. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bTgS0DuhaUU. Accessed 2018 Jun 26. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pathirana T, Clark J, Moynihan R. Mapping the drivers of overdiagnosis to potential solutions. BMJ. 2017;358:j3879. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3879. Epub 2017 Aug 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansson M, Hansson A, Brodersen J. Estimating overdiagnosis in screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: could a change in smoking habits and lower aortic diameter tip the balance of screening towards harm? BMJ. 2015;350:h825. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h825. Epub 2015 Mar 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]