Abstract

Introduction:

The incidence of extrauterine pregnancy increases to 2–12% following in vitro fertilization –embryo transfer. Several pathogenic theories have been suggested, including abnormal hormonal secretion or exogenous hormones administered in assisted reproductive technology (ART).

Case report:

A 32-year-oId nulliparous woman with primary infertility and Stage 3 endometriosis was treated by ART with intracytoplasmic sperm injection and embryo transfer. The patient showed simultaneous bilateral extrauterine pregnancy, managed by laparoscopic salpingectomy.

Discussion:

The various possible pathophysiological mechanisms are described, with a review of the literature on simultaneous bilateral extrauterine pregnancy following ART. In pregnancies following ART, ectopic pregnancy should always be screened for by serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin monitoring and transvaginal ultrasound until the implantation site can be confirmed as the incidence is higher than in spontaneous pregnancy. Even if serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin concentration increases normally, possible bilateral ectopic pregnancy should always be investigated if no intrauterine gestational sac can be seen.

Keywords: bilateral ectopic pregnancy, embryo transfer, endometriosis, in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection

Introduction

The rate of ectopic pregnancy (EP) is 2% of all pregnancies,1 with a higher rate when assisted reproductive technology (ART) is involved. In the USA in 1999, EP was found in 2.2% of all pregnancies from in vitro fertilization (IVF) and in 1.9% of those resulting from intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), while in the same year in France the occurrence was 3.4% and 1.9%, respectively.2 The first case of IVF and embryo transfer (ET) that resulted in tubal pregnancy was reported by Steptoe and Edwards in 1976.3 Bilateral tubal pregnancy is a rare clinical condition with an incidence of one in 200,000 pregnancies.4,5 It is rare after ART, with only a few case reports. In 1983, Trotnow et al6 reported the first case after IVF–ET, and Kahraman et al7 described the first case after ICSI in 1995.

The present case of bilateral tubal pregnancy occurred in a patient undergoing ICSI with ET 48 hours after ICSI for infertility secondary to Grade 3 endometriosis, with isolated asthenospermia as a male factor.

Case report

The patient was a 32-year-old gravida 1 parity 0 woman with a known case of Grade 3 endometriosis discovered in 2009 during diagnostic laparoscopy for dysmenorrhea. During this intervention, a 6-cm ovarian cyst was removed and a methylene blue test confirmed bilateral tubal patency. Two years later, the patient achieved spontaneous pregnancy, which ended with first trimester miscarriage. For the 2 years prior to 2013, she had been attending our infertility clinic for secondary infertility. Magnetic resonance imaging performed to evaluate her endometriosis status showed rectovaginal nodular adhesion with a 40-mm right ovarian endometrioma. The patient had no symptoms of endometriosis other than mild dysmenorrhea. Serology (chlamydiasis and mycoplasmosis) was negative and the anti-Müllerian hormone concentration was 4.66 ng/mL. However, asthenospermia was detected in her partner. Due to the duration of the infertility (2 years) and endometriosis, we decided to proceed with ART.

It was decided to perform downregulation with gonadorelin agonist from Day 21 of the last menstrual period (Decapeptyl, 0.1 mg; IPSEN Ltd., 190 Bath Road, Slough, Berkshire, SL1 3XE, UK), followed by recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone stimulation (Puregon Pen, 300 IU; Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited, Hertford Road, Hoddesdon, Hertfordhire, EN11 9BU, UK). Twelve days after stimulation and 36 hours after induction of ovulation by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; Ovitrelle; Merck Serono Ltd., Bedfont Cross, Stanwell Road, Feltham, Middlesex, TW14 8NX, UK), egg collection retrieved 10 ovocytes. Two embryos were transferred on Day 2 by ET transfer catheter (KT Ellios catheter; Laboratoires Ellios, 365 rue de Vaugirard, 75015 Paris) in 15-mL transfer medium, and two embryos were frozen at the blastocyst stage (Day 5 and Day 6). The luteal phase was supported with progesterone (Utrogestan, 600 mg/d; Besins Healthcare Avenue Louise, 287 B-1050 Brussels, Belgium). On Day 15 after ET, the β-hCG concentration was 242 IU/L and 1383 IU/L 48 hours later.

The patient presented to the gynecology emergency department 19 days after ET for right iliac fossa pain without vaginal bleeding. β-hCG level was 2377 IU/L and vaginal ultrasound found no intrauterine gestational sac, lateral uterine mass, or free fluid in the rectovaginal pouch. The only positive finding was the 40-mm right ovarian endometrioma, which had been found 1 year before. The patient was admitted for observation. After 48 hours, β-hCG concentration was 7722 IU/L, and control ultrasound showed free fluid and a 10-mm left adnexal mass (Figure 1). Laparoscopy was performed and we found left ampullary EP with moderate bleeding (estimated blood loss: 250 mL), a severe pelvic adhesion with distortion of fallopian tube bilaterally, and a rectovaginal nodule obscuring the pouch of Douglas. The right tube was slightly distended. Left salpingectomy was immediately performed but it was impossible to differentiate if there was another EP in the right tube, therefore it was conserved. The patient was discharged in good condition 1 day after surgery with a decreased β-hCG level of 3780 IU/L, which further decreased to 1980 IU/L in the 48 hours postdischarge. We did not repeat the ultrasound examination because of the decreasing β-hCG level, which could be a good idea to discover the right EP earlier if it has been done.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image of left side ectopic pregnancy.

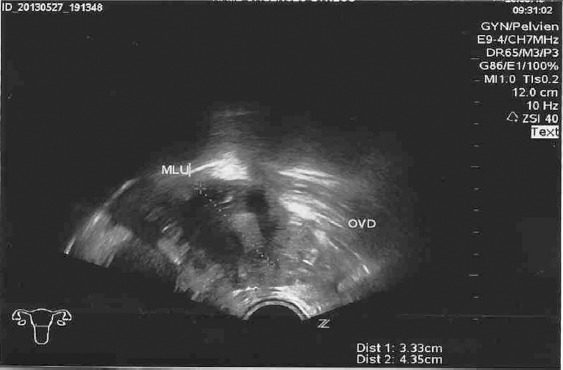

One week later, the patient was seen again in the emergency department with right iliac fossa pain, guarding and no rebound tenderness, associated with mild vaginal bleeding. Ultrasound found a 4-mm right adnexal mass and free fluid in the rectovaginal pouch (Figure 2) and the β-hCG concentration was 3520 IU/L. Laparoscopic right salpingectomy was performed for a distended right tubal EP and bleeding (estimated blood loss: 200 mL).

Figure 2.

Ultrasound image of right ectopic pregnancy.

The patient was discharged in good condition 2 days post-operatively with hemoglobin at 9 g/L and serum β-hCG at 1103 IU/L (returning to 0 at 2 weeks after discharge); histopathological examination confirmed bilateral tubal pregnancy.

Discussion

There are several theories about the genesis of EP and its pathophysiology: endosalpinx pathology (tubal factor) is one well-known important factor8,9 induced by sexually transmitted infection; distortion of pelvic anatomy caused by diseases such as endometriosis or adhesion after previous surgery; and history of EP or hormone concentration imbalance during the menstrual cycle.10

The incidence of EP increases in IVF–ET to between 2% and 12%,11,12 and seems to be related to abnormal hormonal secretions or exogenous hormones administered in ART (notably the smooth muscle relaxant effects of progesterone in luteal support).13 The incidence may increase with the number of transferred embryos, and it is recommended that the volume of transfer medium should not exceed 20 mL.14 Dubuisson et al15,16 reported a 2% incidence of EP after ET in 10–20 mL of fluid, although other authors have not confirmed these findings.16,17 Knutzen et al18 reported tubal reflux in 38% of patients undergoing a mock transfer of 40 mL of radiopaque dye.

In the particular case of bilateral EP after ICSI–ET, three theories have been suggested. First, embryos may be directly injected into the tubes. Second, embryos may be transferred correctly to the endometrial cavity but regressively migrate to the tubes as a consequence of endometrial secretion. The third theory involves a “spray effect” during transfer, whereby embryos might be pushed toward the tubal portions; in healthy functioning tubes, however, they should return to the endometrial cavity.10,19,20

The present case involved multiple risks of EP such as IVF–ET, pelvic adhesion, surgical history, and advanced endometriosis. The latter plays an important role in increasing the probability of EP, causing intrinsic tubal pathologies such as tubal endosalpingiosis that may also account for EP.

EP is becoming more frequent with the development of ART. In case of pregnancy after ART, EP should always be screened for by monitoring serum β-hCG and performing transvaginal ultrasound until the implantation site can be confirmed, as the incidence is higher than in spontaneous pregnancy. We should be careful when two embryos are transferred, even if the serum β-hCG concentration increases normally, and possible bilateral EP should always be investigated if no intrauterine gestational sac can be seen. In the present case, serum β-hCG levels were doubling normally, but there was no intrauterine image. Another important point during ART is that, in case of unilateral EP after the transfer of two embryos, the situation of the other tube should be systematically checked and β-hCG levels should be monitored until negative. In the present case, distention of the other tube was mild but, as the patient was known to have severe endometriosis with significant peritoneal adhesions, it was decided to continue β-hCG monitoring, which decreased after the first operation but then increased 1 week later.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Speroff L, Glass RH, Kase NG. Clinical Gynecological Endocrinology and Infertility. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patil M. Ectopic pregnancy after infertility treatment. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2012;5:154–165. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.101011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steptoe PC, Edwards RG. Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet. 1978;12:366. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonler M, Rasmussen KL, Lundorff P. Coexistence of bilateral tubal and uterine pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:750–752. doi: 10.3109/00016349509021188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart HL. Bilateral ectopic pregnancy. West J Surg Obstet Gynecol. 1950;58:648–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trotnow S, Al-Hasani S, Hünlich T, Schill WB. Bilateral tubal pregnancy following in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Arch Gynecol. 1983;234:75–78. doi: 10.1007/BF02114729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahraman S, Alatas C, Tasdemir M, Nuhoglu A, Aksoy S, Biberoglu K. Simultaneous bilateral tubal pregnancy after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:3320–3321. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verhulst G, Camus M, Bollen N, Van Steiterghem A, Devroey P. Analysis of risk factors with regard to the occurrence of ectopic pregnancy after medically assisted procreation. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1284–1287. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman A, Weinraub Z, Ron-El R, Bukovsky I, Golan A, Caspi E. The role of tubal pathology and other parameters in ectopic pregnancies occurring in in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:864–868. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53947-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Los Ríos JF, Castañeda JD, Miryam A. Bilateral ectopic pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serour GI, Aboulghar MD, Mansour R, Sattar MA, Amin Y, Aboulghar Complications of medically assisted conception in 3,500 cycles. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:638–642. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pyrgiotis E, Sultan KM, Neal GS, Liu HC, Grifo JA, Rosennwaks Z. Ectopic pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Gen. 1994;11:79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02215992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garmel SH. Early pregnancy risks. In: Decherney AH, Nathan L, editors. Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003. pp. 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JD, Chang SY, Chang MY, Lai YM, Soong YK. Simultaneous bilateral tubal pregnancies after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: report of a case. J Formos Med Assoc. 1992;91:99–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubuisson J, Aubriot F, Mathieu L, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in 556 pregnancies after in vitro fertilization: implications for preventive management. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:686–690. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen J, Mayoux MJ. Grossesse ectopique après fécondation in vitro et transfert d'embryon. Contracept Fertil Sex. 1986;14:999–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diedrich K, Van der Ven H, Al-Hasani S, Krebs D. Establishment of pregnancy related to embryo transfer techniques after in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1989;4:S111–S114. doi: 10.1093/humrep/4.suppl_1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knutzen V, Stratton CJ, Sher G, et al. Mock embryo transfer in early luteal phase. The cycle before in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: a descriptive study. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:156–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issat T, Grzybowski W, Jakimiuk AJ. Bilateral ectopic tubal pregnancy, following in vitro fertilisation (IVF) Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2009;47:S147–S148. doi: 10.2478/v10042-009-0093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewitt J, Martin R, Steptoe PC, Rowland GF, Webster J. Bilateral tubal ectopic pregnancy following in-vitro fertilization and embryo replacement. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92:850–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]