INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract-related bloodstream infection acquired during hospitalization can lead to substantial morbidity and mortality. Previous studies have indicated that up to 3% of patients in acute care facilities with hospital-acquired bacteriuria develop a related bloodstream infection.1 Veterans are especially susceptible to this complication given that they are predominantly male, and men have been found to develop secondary bloodstream infections due to hospital-acquired urinary tract infection twice as often as women, which is thought to be reflective of structural genitourinary tract abnormalities in this population.2 Additional risk factors previously identified for this infection include age, presence of urethral catheter, urologic disease, malignancy, diabetes mellitus, neutropenia, renal disease, smoking, and immunosuppressant therapy.3-5 Compared to the general population, Veterans Affairs (VA) patients tend to have a prevalence higher than the general population of some of these risk factors--such as diabetes mellitus and presence of a urinary catheter--and prove to be an ideal group in which to study this disease state.3, 6

As national quality measures have increasingly focused on healthcare-associated infections, learning more about the etiology of hospital-acquired urinary tract-related bloodstream infection may help inform preventive interventions.7, 8 Previous studies have described the epidemiology of urinary tract-related bloodstream infections,2, 5, 9, 10 but most have been limited to single sites. One prior single-site study identified risk factors for urinary tract-related bloodstream infection among a Veteran population; however these patients were hospitalized between 1984 and 1999.4 As such, we investigated urinary tract-related bloodstream infection within the Veteran population at four diverse VA hospitals, one in the South and three in the Midwest, to examine whether the microbiology of urinary tract-related bloodstream infection is evolving and to assess the case fatality rate due to this infection.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective review of hospital-acquired urinary tract-related bloodstream infections among adult Veteran inpatients admitted to four VA hospitals over 15 years (01/01/2000-12/31/2014). Cases were defined as patients with urine and blood cultures that grew the same organism with the following criteria: urine culture obtained ≥48 hours after admission, urine culture obtained prior to or the same day as the blood culture, and positive blood culture within 14 days of positive urine culture. The urine culture was considered positive if >103 CFU/ml of a single organism grew.11 Electronic medical records were used to obtain clinical, demographic and microbiologic information. Manual medical record reviews for all cases were conducted by a research nurse to exclude cases with primary bloodstream infection with hematogenous spread to the kidney. Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted using t-test, chi-square tests of association and test for trend was performed by genus and for case fatality rate over time. Analyses were performed using SAS V9.4 (Cary, NC). The study received human subjects institutional review board approval from the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

RESULTS

A total of 499 patients met the case selection criteria. Several patient characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The mean age was 67.2 years, median age was 67 years, and the majority of patients were white (56.3%). Cases who survived were younger on average than those who died (65.9 years vs. 71.0 years, p <0.0001). The study population was mostly male, as expected for a VA population (98.6%). The median length of stay was 26 days and the mean time from admission to bloodstream infection was 19.85 days. Upon discharge, 58.3% of patients were discharged home, 24.2% died in the hospital and 16.0% were transferred to another facility, VA or community nursing home. Surgery during the concurrent admission was noted in 59.3% of patients. Diabetes mellitus (27.5%), neutropenia (22.2%), malignancy (20.4%) and renal disease (18.6%) were the most prevalent comorbidities. A total of 42.1% of patients with urinary tract-related bloodstream infection had an indwelling urethral catheter on the date that they had a positive blood culture that met case criteria, and 64.9% of patients had a urethral catheter at some time between admission and the time they were found to have a positive blood culture that met case criteria for a urinary tract-related bloodstream infection.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of 499 Patients with Hospital-Acquired Urinary Tract-Related Bloodstream Infection

| Characteristic | Total (n=499) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (range) | 67.2 (24-95) |

| Age in years, mean (range) - died | 71.0 (46-95) |

| Age in years, mean (range) - survived | 65.9 (24-92) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 492 (98.6%) |

| Female | 7 (1.4%) |

| Race | |

| White | 281 (56.3%) |

| Black | 175 (35.1%) |

| Other/Declined/Missing | 43 (4.6%) |

| Length of Stay (days) | |

| Mean | 46.8 |

| Median | 26 |

| Range | 4-1440 |

| Discharge Disposition | |

| Home | 291 (58.3%) |

| Died | 121 (24.2%) |

| Transfer to Nursing Home | 69 (13.8%) |

| Transferred to other VA Hospital | 11 (2.2%) |

| Irregular Discharge | 7 (1.4%) |

| Conditions1 | |

| Surgery at Current Admission | 296 (59.3%) |

| History of Renal Failure or Renal Disease | 93 (18.6%) |

| History of Malignancy | 102 (20.4%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 137 (27.5%) |

| Neutropenia | 111 (22.2%) |

| History of Transplant | 2 (0.4%) |

| Liver Disease | 43 (8.6%) |

| Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy | 31 (6.2%) |

| Urinary Catheter Presence | |

| At time of infection | 210 (42.1%) |

| Any time after admission | 324 (64.9%) |

Patients were coded for multiple conditions if these co-existed.

Gram-negative bacterial organisms were involved in the infections of more than half (56.7%) of all cases. Very few isolates (1.6%) were found to have an extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing organism. Staphylococcus was the most common genus associated with infection (36.5%), with coagulase-negative Staphylococcus being the most common species. Conventional genitourinary organisms were frequent: Escherichia coli was the second most common cause of infection (19.2%) and Klebsiella spp. was found in 8.4% of infections. Only one-tenth of infections were due to Candida species (10.2%). Of those, the predominant organism identified was Candida albicans.

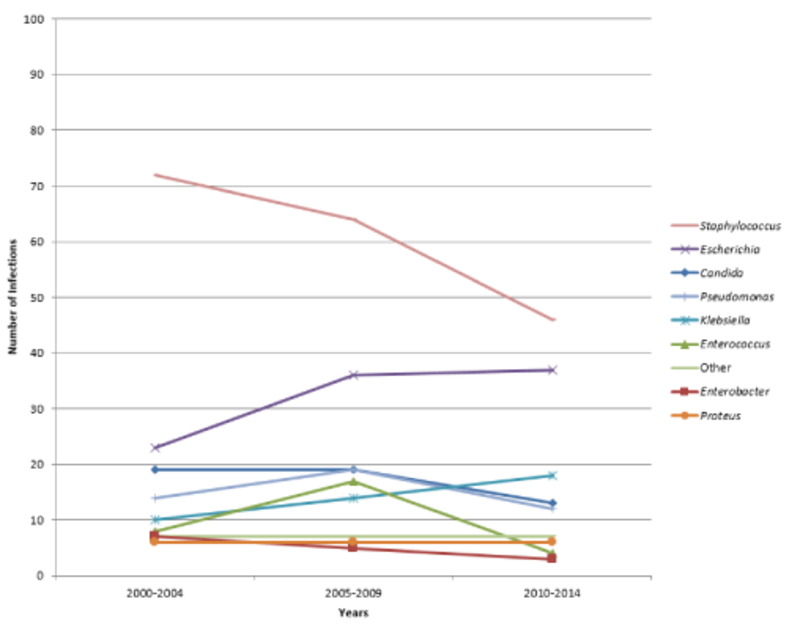

Overall, the case fatality rate was 24.2%. Adjusting for age, malignancy and diabetes, having a surgery during the admission was associated with increased in-hospital mortality (RR=1.61, p=0.01). A total of 25.8% of patients with a Staphylococcus infection and 20.7% with an enterococcal infection died in the hospital. Although Pseudomonas and Enterobacter infections were less common (9.0% and 3.0%, respectively), both were associated with a 20.0% case fatality rate. Genus-specific time trends in infection are presented in Figure 1. Overall, Staphylococcus infections decreased over time (p=0.11), while disease due to conventional genitourinary organisms, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp., increased (p=0.02 and p=0.03, respectively).

Figure 1:

Percentage of Hospital-Acquired Urinary Tract-Related Bloodstream Infections over Time, by Genus

DISCUSSION

We investigated the epidemiology of hospital-acquired urinary tract-related bloodstream infection at 4 VA hospitals over a 15-year period. Several important findings on the microbiology and mortality associated with this infection emerged from our study. First, we have shown a potential shift in the distribution of organisms related to urinary tract-related bloodstream infection acquired during hospitalization. While Staphylococcus spp. remain common organisms, Gram-negative organisms caused the most infections, differing from some previous studies.2, 9, 10 Second, few multi-drug resistant Gram-negative organisms were seen, and Candida albicans --which is not commonly associated with antifungal drug resistance12 --was the most prevalent fungal organism, which is reassuring from an antimicrobial resistance perspective. Third, we identified a considerable case fatality rate among patients with hospital-acquired urinary tract-related bloodstream infection.

Previous studies investigating the microbiology of urinary tract-related bloodstream infection have largely been single center studies. Prior work has found that associated mortality with this infection is high, Gram-negative bacteria (such as Escherichia coli) tend to be the primary etiologies of urinary tract-related bloodstream infection and that risk factors include: genitourinary pathology, presence of urinary catheter, age, male sex, history of diabetes mellitus, malignancy or recent surgery.2, 3, 9 Chang and colleagues reported an overall case fatality rate of 32.8% among patients with hospital-acquired urinary tract-related bloodstream infection in a single site, academic, non-VA hospital.9 The case fatality rate in our study of urinary tract-related bloodstream infection patients across 4 VA hospitals (24.2%) was also considerable.

The predominance of Gram-negative organisms in our study and previous studies is biologically plausible, as this infection arises from the anatomical site of the genitourinary system. However, the finding in our study that Staphylococcus spp. was the most common species, and that Enterococcus spp. have been more prevalent in recent studies,9 could signal a shift in the factors that contribute to this infection (e.g., underlying co-morbidities, place of acquisition, type of organism).2, 9, 10 The predominance of Staphylococcus spp. were coagulase-negative (90.1%), which is surprising and suggests that indwelling devices could alter microbiologic flora and etiology favoring coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp.13

The substantial mortality of those with a staphylococcal, pseudomonal, or enterococcal infection in our cohort emphasizes the importance of horizontal infection control measures. Horizontal infection control interventions implement broad-based infection control strategies such as contact precautions, hand hygiene, chlorhexidine bathing, environmental cleaning, and reducing unnecessary catheter use.14-16 Infection control literature has shown that horizontal infection control approaches have been successful in reducing multiple types of healthcare-associated infections.14, 15, 17 Vertical infection control initiatives -- focusing on specific organisms -- can also be effective.7, 18 One vertical approach undertaken by the VA is the VA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Prevention Initiative which has seen downstream effects of decreased health care-associated transmission and infections with MRSA.7 A recent study also noted an overall decrease in healthcare-associated and hospital-onset staphylococcal bacteremia throughout the VA between 2003-2014 and increased evidence-based care for patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia during this same time frame.19 It is plausible that enhanced VA-wide infection control interventions as well as earlier appropriate evidence-based interventions for serious Staphylococcus aureus infections (such as consultation of infectious disease specialists and appropriate antibiotic prescription19) could have contributed to the decrease in burden of infections due to Staphylococcus aureus seen in our study.

We found that Gram-negative organisms increased and staphylococcal and enterococcal etiologies declined over the 15 years of data collection. Limiting inappropriate urinary and vascular catheters and preventing healthcare-associated infections has increased in the last decade, and infection prevention interventions may have contributed to this microbiological trend.8, 20, 21

Our study has several limitations. First, the absence of controls constrains our ability to identify associations between risk factors and urinary tract-related bloodstream infection. We plan future analyses addressing this limitation. Second, due to the retrospective design of the study, determining whether the urinary tract infection was truly the primary source of infection rather than a secondary seeding from another site was challenging. To address this, we performed chart review and excluded cases that had an evident secondary bloodstream source, such as endocarditis. Third, detailed information regarding indwelling catheter days prior to the bloodstream infection and the duration and dose of antimicrobial therapies utilized were not available. We reviewed antibiograms from VA sites and academic affiliates to help inform microbiologic interpretation of the data and evaluate whether geographic variation could be playing a role, but the long duration of the study period and differences in antibiogram design, formulary restriction and stewardship interventions limited this approach. Fourth, we did not have the granular data needed to confirm that the urinary tract-related bloodstream infection was the primary cause of death. As such, our genus-specific case fatality rates are approximations, but still highlight the potential fatal consequences of this serious healthcare-associated infection.

Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the literature about urinary tract-related bloodstream infection and may reflect how continued efforts to decrease healthcare-associated infections may contribute to changes in the microbiology of this infection. In most patients who develop a secondary bloodstream infection from a urinary tract infection there is a timeframe in which preventive efforts to reduce risk factors such as unnecessary urinary catheters may be most effective.2, 5

Focused efforts to prevent hospital-acquired urinary tract-related bloodstream infection via evidence-based infection control measures22 should be prioritized to enhance the safety of Veterans.

Table 2:

Microbiology and Genus-specific Case Fatality among 499 Patients with Hospital-Acquired Urinary Tract-Related Bloodstream Infection

| Genus | Species | Died in Hospital |

Total | Genus- specific % of BSI Cases |

Genus- specific Case Fatality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter | Acinetobacter spp. | 1 | 2 | 0.4% | 50.0% |

| Candida | Candida glabrate | 1 | 5 | 10.2% | 45.1% |

| Candida albicans | 17 | 35 | |||

| Candida dubliniensis | 4 | 7 | |||

| Candida parapsilosis | 0 | 2 | |||

| Candida tropicalis | 1 | 2 | |||

| Citrobacter | Citrobacter spp. | 1 | 3 | 0.6% | 33.3% |

| Enterobacter | Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | 5 | 3.0% | 20.0% |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 2 | 10 | |||

| Enterococcus | Enterococcus faecalis | 4 | 17 | 5.8% | 20.7% |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 | 7 | |||

|

Enterococcus faecium (VRE) |

1 | 3 | |||

| Enterococcus spp. * | 0 | 2 | |||

| Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli | 16 | 90 | 19.2% | 18.8% |

| Escherichia coli ESBL+ | 2 | 6 | |||

| Klebsiella | Klebsiella oxytoca | 0 | 6 | 8.4% | 4.8% |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 | 34 | |||

|

Klebsiella pneumoniae ESBL+ |

0 | 2 | |||

| Proteus | Proteus mirabilis | 8 | 18 | 3.6% | 44.4% |

| Pseudomonas |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

9 | 45 | 9.0% | 20.0% |

| Staphylococcus | Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus |

40 | 164 | 36.5% | 25.8% |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

7 | 15 | |||

| Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus |

0 | 3 | |||

| Streptococcus | Group B Streptococcus | 0 | 1 | 0.6% | 0.0% |

| Alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus |

0 | 2 | |||

| Other | Burkholderia cepacia | 0 | 1 | 2.6% | 23.1% |

| Corynebacterium spp. | 1 | 2 | |||

| Morganella morganii | 1 | 3 | |||

| Providencia spp. | 0 | 2 | |||

| Serratia marascens | 1 | 5 | |||

| 121 | 499 |

speciation not available

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a Merit Review (EPID-011-11S) awarded to SS from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service.

Footnotes

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Nicolle LE. Catheter associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control. 2014;3:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krieger JN, Kaiser DL, Wenzel RP. Urinary tract etiology of bloodstream infections in hospitalized patients. The Journal of infectious diseases. July 1983;148(1):57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greene MT, Chang R, Kuhn L, et al. Predictors of hospital-acquired urinary tract-related bloodstream infection. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. October 2012;33(10):1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saint S, Kaufman SR, Rogers MA, Baker PD, Boyko EJ, Lipsky BA. Risk factors for nosocomial urinary tract-related bacteremia: a case-control study. American journal of infection control. September 2006;34(7):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortin E, Rocher I, Frenette C, Tremblay C, Quach C. Healthcare-associated bloodstream infections secondary to a urinary focus: the Quebec provincial surveillance results. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. May 2012;33(5):456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pogach LM, Hawley G, Weinstock R, et al. Diabetes prevalence and hospital and pharmacy use in the Veterans Health Administration (1994). Use of an ambulatory care pharmacy-derived database. Diabetes care. March 1998;21(3):368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain R, Kralovic SM, Evans ME, et al. Veterans Affairs initiative to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. The New England journal of medicine. April 14 2011;364(15):1419–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knoll BM, Wright D, Ellingson L, et al. Reduction of inappropriate urinary catheter use at a Veterans Affairs hospital through a multifaceted quality improvement project. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. June 2011;52(11):1283–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang R, Greene MT, Chenoweth CE, et al. Epidemiology of hospital-acquired urinary tract-related bloodstream infection at a university hospital. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. November 2011;32(11):1127–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bishara J, Leibovici L, Huminer D, et al. Five-year prospective study of bacteraemic urinary tract infection in a single institution. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. August 1997;16(8):563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipsky BA, Ireton RC, Fihn SD, Hackett R, Berger RE. Diagnosis of bacteriuria in men: specimen collection and culture interpretation. The Journal of infectious diseases. May 1987;155(5):847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel PK, Erlandsen JE, Kirkpatrick WR, et al. The Changing Epidemiology of Oropharyngeal Candidiasis in Patients with HIV/AIDS in the Era of Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS research and treatment. 2012;2012:262471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker K, Heilmann C, Peters G. Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clinical microbiology reviews. October 2014;27(4):870–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryce E, Grant J, Scharf S, et al. Horizontal infection prevention measures and a risk-managed approach to vancomycin-resistant enterococci: An evaluation. American journal of infection control. November 2015;43(11):1238–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traa MX, Barboza L, Doron S, Snydman DR, Noubary F, Nasraway SA Jr., Horizontal infection control strategy decreases methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection and eliminates bacteremia in a surgical ICU without active surveillance. Critical care medicine. October 2014;42(10):2151–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Septimus E, Weinstein RA, Perl TM, Goldmann DA, Yokoe DS. Approaches for preventing healthcare-associated infections: go long or go wide? Infection control and hospital epidemiology. July 2014;35(7):797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. The New England journal of medicine. June 13 2013;368(24):2255–2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wertheim HF, Vos MC, Boelens HA, et al. Low prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) at hospital admission in the Netherlands: the value of search and destroy and restrictive antibiotic use. The Journal of hospital infection. April 2004;56(4):321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goto M, Schweizer ML, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, et al. Association of Evidence-Based Care Processes With Mortality in Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia at Veterans Health Administration Hospitals, 2003–2014. JAMA internal medicine. September 05 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magill SS, Hellinger W, Cohen J, et al. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections in acute care hospitals in Jacksonville, Florida. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. March 2012;33(3):283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mody L, Greene MT, Saint S, et al. Comparing Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection Prevention Programs Between Veterans Affairs Nursing Homes and Non-Veterans Affairs Nursing Homes. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. December 05 2016:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A Program to Prevent Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection in Acute Care. The New England journal of medicine. June 02 2016;374(22):2111–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]