Abstract

Introduction

The view that interacting with nature enhances mental wellbeing is commonplace, despite a dearth of evidence or even agreed definitions of ‘nature’. The aim of this review was to systematically appraise the evidence for associations between greenspace and mental wellbeing, stratified by the different ways in which greenspace has been conceptualised in quantitative research.

Methods

We undertook a comprehensive database search and thorough screening of articles which included a measure of greenspace and validated mental wellbeing tool, to capture aspects of hedonic and/or eudaimonic wellbeing. Quality and risk of bias in research were assessed to create grades of evidence. We undertook detailed narrative synthesis of the 50 studies which met the review inclusion criteria, as methodological heterogeneity precluded meta-analysis.

Results

Results of a quality assessment and narrative synthesis suggest associations between different greenspace characteristics and mental wellbeing. We identified six ways in which greenspace was conceptualised and measured: (i) amount of local-area greenspace; (ii) greenspace type; (iii) visits to greenspace; (iv) views of greenspace; (v) greenspace accessibility; and (vi) self-reported connection to nature. There was adequate evidence for associations between the amount of local-area greenspace and life satisfaction (hedonic wellbeing), but not personal flourishing (eudaimonic wellbeing). Evidence for associations between mental wellbeing and visits to greenspace, accessibility, and types of greenspace was limited. There was inadequate evidence for associations with views of greenspace and connectedness to nature. Several studies reported variation in associations between greenspace and wellbeing by life course stage, gender, levels of physically activity or attitudes to nature.

Conclusions

Greenspace has positive associations with mental wellbeing (particularly hedonic wellbeing), but the evidence is not currently sufficient or specific enough to guide planning decisions. Further studies are needed, based on dynamic measures of greenspace, reflecting access and uses of greenspace, and measures of both eudaimonic and hedonic mental wellbeing.

Introduction

Background

Urbanisation is increasing at an unprecedented rate, and with over half the world’s population now residing in cities [1], many people may not have access to the green landscapes in which the human species evolved [2, 3]. Greenspace may provide human benefits, such as facilitating exercise, social activities and connecting with nature [4], and it is suggested that urban greenspaces are critical to healthy living, both physically [5, 6] and mentally [7, 8]. There may also be salutogenic effects on mental health and wellbeing, such as increased attention, feelings of happiness and reduced stress [9, 10].

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals emphasise the importance of greenspace provision “to foster prosperity and quality of life for all” [11]. The World Health Organisation stated that urban greenspaces (including parks, woodlands, and sports facilities) are a “necessary component for delivering healthy, sustainable, liveable conditions” [12], while highlighting the dearth of evidence to support planning advice [12]. In the UK, local authorities are responsible for providing access to the natural environment [13], and guidelines recommend that all residents should live within 300m of at least 2 hectares of greenspace [14, 15], despite limited evidence for the wellbeing benefits of these recommendations.

Measuring greenspace

One of the reasons for this dearth of evidence is the lack of consensus regarding the definition of the terms ‘nature’ and ‘natural’ [10, 16], and features that may appear ‘natural’ are often artificially constructed [8]. Hartig et al. provide the most detailed definition of nature, as the “physical features and processes of nonhuman origin…, the ‘living nature’ of flora and fauna” [8].

Furthermore, ‘nature’ and ‘greenspace’ are often used interchangeably [17–21]; ‘greenspace’ is more inclusive, referring to areas of grass, trees or other vegetation [22], and can be used to describe both surrounding greenness in the countryside, and spaces managed or reserved in urban environments [14]. Greenspace was therefore chosen as the focus of this review. We chose not to include studies of water (blue space), as this is generally considered separately to greenspace [5, 23–25].

Mental wellbeing and greenspace

Mental wellbeing comprises happiness and life satisfaction (hedonic wellbeing) and fulfilment, functioning and purpose in life (eudaimonic wellbeing) [26, 27]. It is therefore a multi-dimensional measure of positive mental health, reflecting more than an absence of mental distress, in which those with the best mental wellbeing are able to realise their potential, cope well with everyday stressors, and flourish mentally. It is increasingly recognised as an indicator of national prosperity [28], due to its associations with productivity, longevity and societal functioning [28–30]. While theories suggest that mental wellbeing may be improved by exposure to greenspace, there is limited evidence for clear benefits; many studies use unvalidated measures or proxies such as mental distress or quality of life [7]. Additionally, measures of nature and greenspace vary widely [8, 12, 22].

Previous reviews have examined the relationship between greenspace (/nature) and general health [7, 8, 12], or mental health [31], although the latter has generally been defined in terms of mental distress, rather than mental wellbeing. While Douglas et al. describe their recent scoping review as focussing on “green space benefits for health and well-being”, they include no studies measuring mental wellbeing per se, but provide further evidence for reduced mental distress in greener neighbourhoods [7]. Similarly, Gascon et al.’s review of “Mental Health Benefits” of long-term greenspace exposure includes some studies of aspects of mental wellbeing, but focusses mainly on measures of mental distress, rather than positive mental health [31]. We therefore believe this is the first review to examine greenspace associations specifically with mental wellbeing, in adults.

The aim of this review was therefore to synthesise quantitative evidence for associations between greenspace and mental wellbeing. We were able to identify varying evidence for associations between different characterisations of greenspace and mental wellbeing, while highlighting key areas for future research, and subsequent implications for policy and practice.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The review was registered with PROSPERO (available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, ID: CRD42016041377). We followed guidance from York’s Centre for Research and Dissemination and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [32, 33]. A search strategy was developed with an information specialist, undertaken by one reviewer (VH), supported by a second, independent reviewer (SW). The following databases were searched: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), American Psychological Association (PsychInfo), National Center for Biotechnology Information (PubMED), Elsevier’s Scopus, and Web of Science (WOS). Common keywords relating to greenspace and mental wellbeing were derived from the literature, refined following a trial search in each database; this created a final set of terms for greenspace (greenspace(s), green space(s), open space(s), green, greener, nature, natural, landscape) and mental wellbeing (wellbeing, well-being, wellbeing, happiness, happy, happier, life satisfaction, satisfaction with life). We restricted searches to studies in English, relating to humans, published after 01/01/1980. Searches were run from 07/07/2016 to 31/01/2018. The full electronic searches are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Database search strategy.

| Database | Search |

|---|---|

| ASSIA | ti(green?space OR "open space" OR green* OR natur* OR landscape) AND ti(wellbeing OR well?being OR "mental health" OR happy OR happi* OR life NEAR/5 satisfaction) |

| PubMed | (((((((greenspace[Title] OR "green space"[Title] OR "open space"[Title] OR green*[Title] OR nature[Title] OR natural[Title] OR landscape[Title])) AND (well-being[Title] OR wellbeing[Title] OR "well being"[Title] OR "mental health"[Title] OR happy[Title] OR happier[Title] OR happiness[Title] OR "life satisfaction"[Title])) AND ("1980/01/01"[PDat]: "2018/01/31"[PDat]) AND Humans[Mesh] AND English[lang]))) |

| PsychInfo | ti(green?space OR "open space" OR green* OR natur* OR landscape) AND ti(wellbeing OR well?being OR "mental health" OR happy OR happi* OR life NEAR/5 satisfaction) AND la.exact("English") |

| Scopus | ((TITLE (greenspace OR (open space) OR (green space) OR green OR greener OR nature OR natural OR landscape) AND TITLE (well?being OR wellbeing OR (mental health) OR happy OR happier OR happiness OR (life W/5 satisfaction)))) AND PUBYEAR > 1979) AND ORIG-LOAD-DATE AFT 1529266261 AND ORIG-LOAD-DATE BEF 1529871076 AND PUBYEAR AFT 2016 AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, "English")) |

| WOS | TITLE: (("green space*" OR greenspace* OR "open space*" OR greener OR green OR nature OR natural OR landscape)) <i>AND</i> TITLE: ((well?being OR wellbeing OR "mental health" OR happy OR happiness OR happier OR life NEAR/5 satisfaction)) Refined by: *LANGUAGES:* (ENGLISH) |

Using the in-built database functions, an auto-search was timed to re-run each query on a weekly basis to detect any further publications within the review duration. All articles recovered from initial searches were recorded in Endnote, and duplicates removed. Titles and Abstracts were screened for potential relevance by two reviewers independently, and full texts of shortlisted studies retrieved for formal inclusion/exclusion. It was agreed that any disputed studies would be cautiously retained for full text evaluation.

Study eligibility criteria

Criteria for inclusion were: (a) Population: adults aged over 16 (or all ages, but not wholly or mainly children); (b) Exposure: any measure of greenspace, defined as areas of grass, trees or other vegetation. Studies measuring personal connectedness to nature were included. As we were interested in all greenspace characteristics, we included both urban and rural studies; (c) Control: Comparators must include a control group which differed in the type/degree of exposure to greenspace, or direct comparison before and after an intervention; (d) Outcome: mental wellbeing, ascertained using a validated measure of hedonic and/or eudaimonic mental wellbeing, or one or more aspects of these (e.g. life satisfaction, happiness, quality of life. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) is designed to measure psychological distress, but includes several positive items, and is prevalent in the literature; studies using this outcome were therefore included. Instruments designed to capture only symptoms of mental distress were not included; (e) No study designs were explicitly excluded.

Evaluation of evidence

After identifying eligible papers, one reviewer (VH) evaluated study contents by extracting: authors, publication date, country, study design, age of participants, sample size, greenspace measures, methods, outcomes, confounders, and a results summary, including effect sizes (regression coefficients/risk ratio and confidence interval/standard error).

For quality appraisal, risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane-recommended criteria [32]: the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), adapted for longitudinal and cross-sectional studies, alongside the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) tool for controlled studies [34, 35]. The criteria cover potential risk of bias arising from: representativeness of the sample, participant awareness of the intervention, control factors, and selection of reported results.

We used established Quality Assessment thresholds to categorise each article [36]. For those assessed using the Cochrane RoB tool, a Good quality study met all criteria (low RoB), while those of Fair quality had moderate RoB not meeting one criterion; Poor quality studies had high RoB, not meeting multiple criteria. More complex scoring criteria were used for papers analysed using the NOS, across three domains: Selection (representativeness of sample, treatment of non-respondents), Comparability (between exposure groups) and Outcome (assessment, soundness). Good studies scored at least 3 for Selection, 1 for Comparability and 2 for Outcome; Fair studies scored at least 2, 1 and 2, respectively. Poor papers scored 1 or less for each category. A final quality rating was given according to the lowest rating for any category.

Stratification by characterisation of greenspace

We identified six types of study, according to the characterisation of greenspace: (a) amount of local-area greenspace, most commonly the proportion of local areas covered by greenspace; (b) greenspace type; (c) views of greenspace; (d) visits to greenspace; (e) accessibility, in terms of proximity to greenspaces and self-reported ‘access’; and (f) subjective connection to nature.

We conducted a narrative review of evidence, as methodological heterogeneity precluded meta-analysis. Evidence for associations between each type of greenspace characteristic and mental wellbeing was classified according to the consistency, strength and methodological quality of the findings, and study design. Evidence of association was categorised using established guidelines used by other studies in the field [37]: Adequate (most studies, at least one Good quality, reported an association between greenspace and mental wellbeing); Limited (more than one study, at least one Good, reported an association, but with inconsistent findings); Inadequate (associations reported in one or more studies, but none Good quality); and No association (several Good quality studies reported an absence of a statistically significant association between greenspace and mental wellbeing).

Results

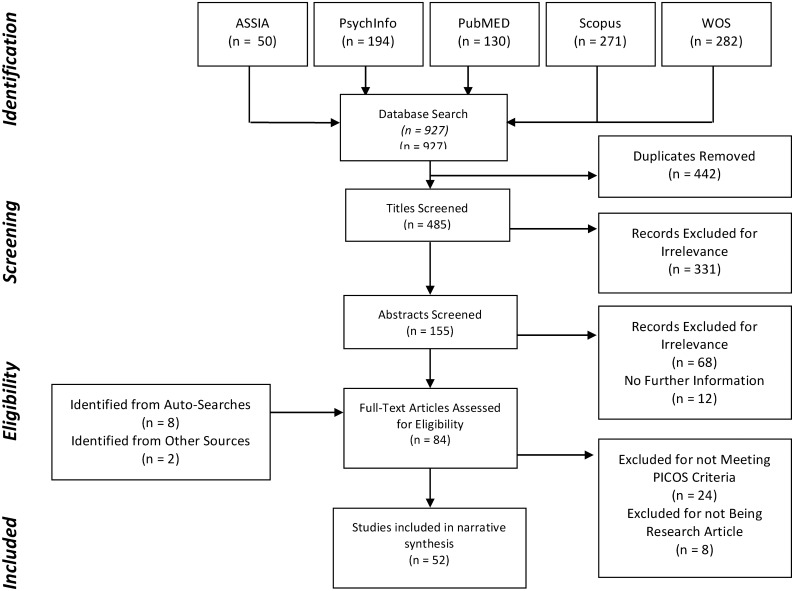

Titles and abstracts of 485 records were screened, and 75 chosen for full-text evaluation; 42 were found to be eligible. During this process, 10 additional papers were found via Auto-Searching the databases and recommendations. Therefore, 52 papers were finally included in this review (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Study selection process.

Among these, 4 were controlled case studies and a further 6 were longitudinal cohort studies; there was one ecological analysis, 4 uncontrolled case studies, the remaining 37 were cross-sectional surveys. Two studies were international, 31 were restricted to Europe, 15 just in the UK; 5 were based in the USA with another 6 in Canada, 10 in Australia. Analyses were confined to urban areas in 22 cases, 9 included only rural greenspace. Sample size ranged from 25 to 30,900 participants, but was not specified in 3 cases. Age ranges were fairly consistent, covering young adults to past retirement age, although 1 focused on ‘youths’ (aged 16–25), 3 studies recruited university students and two included mainly people aged over 55; however, 11 studies did not specify participants’ age. After quality assessment, the majority of studies (n = 27) were determined to be Good, 13 were Fair, and 12 Poor. For Poor studies, Table 2 provides further justification. For full details of the risk of bias for each study, heat maps are presented in S1 and S2 Tables. Table 3 provides further detail on the typologies of greenspace measures implemented for each study.

Table 2. Main characteristics and results of included studies.

| Authors, Year, Country | Study Design | Age of Participants | Sample Size | Greenspace Measure | Mental Wellbeing Tool | Mental Wellbeing | Confounders | Methods | Statistically Significant Associations** |

Effect Size** (C: Correlation Coefficient, SE: Standard Error, CI: Confidence Interval) |

Interaction Effects | Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a) Amount of Local- Area Greenspace | |||||||||||||

| Alcock et al., 2015, England [38] | Longitudinal Cohort Study | under 25- over 75 | 2,020 214 movers |

% area of each LSOA*, 10 land-cover types Rural areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Health Commuting. Local: IMD | Multilevel Linear Regression | Cross-sectional differences: no association. Longitudinal differences for movers: significant, positive associations with increase access individually to Arable, Improved Grassland, Semi-natural Grassland, Mountain, Heath and Bog, and Coastal land cover. |

C, SE: Within-individual: Arable: 0.083, 0.037 Improved Grassland: 1.351, 0.040 Semi-natural Grassland: 0.152, 0.062 Mountains/Heath: 1.667, 0.074 |

N/A | Good | |

| Alcock et al., 2014, England [23] | Longitudinal Cohort Study | 16–55+ | 1,064 residents of BHPS who relocated during survey | % greenspace in each LSOA, including private gardens, Urban areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Health, Pre-move GHQ, Commuting. Local: IMD | Linear Regression | Movers to greener areas: significantly lower GHQ scores post-move. Movers to less green areas: GHQ decreased in year preceding the move but no significant difference post-move. |

C, SE: Movers to greener areas T+1: 0.369, 0.152 T+2: 0.378, 0.158 T+3: 0.431, 0.162 |

N/A | Good | |

| Ambrey and Fleming, 2014, Australia [39] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 15–60+ | NOT GIVEN | % public greenspace in each CD* Urban areas only |

Life Satisfaction | Life Satisfaction | Individual: Demographic, Language, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Health, Commuting, Hours Worked | Linear Regression | More greenspace: higher life satisfaction | C, SE: 0.003, 0.002 | N/A | Good | |

| Ambrey, 2016, Australia [40] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 3,288 | Greenspace per capita, in each CD Urban areas only |

SF-36 Mental Component Survey | Mental Health | Individual: Physical Activity | Linear Regression | More greenspace: better mental health, only for those engaged in physical activity | C, SE: Greenspace Physical Activity Interaction: 4.392, 1.702 | Positive interaction between greenspace and physical activity | Good | |

| Ambrey, 2016, Australia [41] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 6,082 | Greenspace per capita, in each CD Urban areas only |

Life Satisfaction, SF-36 | Life Satisfaction, Quality of Life | Individual: Physical Activity | Logistic Regression | More greenspace: better life satisfaction and quality of life | Odds, CI: Life Satisfaction: 0.942, 0.920–0.990. Quality of Life: 0.974, 0.912–1.039 |

N/A | Good | |

| Ambrey, 2016, Australia [42] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 6,077 | Amount of greenspace in each CD Urban areas only |

SF-36 | Quality of Life | Individual: Demographic, Ethnicity, Marital, SES, Free Time, Social Interaction, Household Members Engaged in Physical Activity, Personality. Local: Proximity to Lake, River, Coastline, SES | Linear Regression | More greenspace: better quality of life, only for those engaged in physical activity | C, SE: 0.553, 0.229 | Positive interaction between greenspace and physical activity | Good | |

| Astell-Burt et al., 2014, UK [17] | Longitudinal Cohort Study | 15–75+ | 65,407 person-years | % greenspace in each ward, excluding water and private gardens Urban areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Smoking | Linear Regression | More greenspace: lower GHQ scores among men. Variation in associations across life course and gender. | C, SE: ‘High’ Greenspace: 0.300, 0.370 | Interactions for life course and gender | Good | |

| Bos et al., 2016, The Netherlands [43] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–87 | 4,924 | % greenspace within 1km and 3km buffers | Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life | Quality of Life | Individual: Demographic, Country of Origin, Marital, SES | Linear Regression | More greenspace within 3km: better quality of life, significant interactions for age and gender. For middle aged men, inverse association Greenspace within 1km: no association |

C, SE: 1km: 5.200, 5.500. 3km: 6.300, 4.500 |

Interactions for life course and gender | Poor Limited Statistical reporting |

|

| De Vries et al., 2003, The Netherlands [5] | Cross-Sectional Survey | All ages (including children) | 10,179 | % greenspace in local area, % bluespace in local area, presence of a garden | GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, SES, Living Conditions, Health Insurances, Life Events in Last Year | Multilevel Linear Regression | More greenspace: lower GHQ scores Access to agricultural space: lower GH Only for lower educated groups Results only significant for whole sample, not for individual urban categories Having a garden: significant only in very urban municipalities |

C, SE: %green within 3km: -0.100, 0.003 |

Interaction with level of urbanity | Good | |

| De Vries et al., 2013, The Netherlands [44] |

Cross- Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 1,641 | Quantity and quality of streetscape greenery, Urban areas only |

SF-36 | Quality of Life | Individual: Demographic, SES, Living Conditions, Health, Life Events in Last Year, | Multilevel Linear Regression | Higher amounts of greenspace: higher QOL, but not statistically significant after quality is added to the model. High quality of greenspace: higher quality of life. |

C, SE: Quantity: 0.007, 0.036 (not statistically significant) Quality: 0.0153, 0.069 |

Both Quantity and Quality show positive interactions with stress, social cohesion, and green activity | Good | |

| Dzhambov et al., 2018, Bulgaria [45] | Cross- Sectional Survey | 15–25 | 399 | Amount of green land within 500m of home, perceived neighbourhood greenness and quality Urban areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, SES, Living Conditions, Noise. Local: Population Density | Linear Mixed Models and Linear Mediation Models | Perceived greenness and quality: lower GHQ scores. No statistically significant associations for objective greenspace measures. |

C, CI: Perceived greenness: -0.59, -0.85- -0.32 Greenspace quality: -0.08, -0.12 - -0.04 |

Higher perceived restorative quality was associated with more physical activity and social cohesion, which was associated with lower GHQ scores. For objective measures, this held for all but the greenspace quality measure. | Fair | |

| Houlden et al., 2017, England [46] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 16–65+ | 30,900 | % greenspace in each LSOA, excluding gardens | SWEMWBS | Mental Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Health, Commuting. Local: IMD | Linear Regression | Greater amounts of greenspace: higher SWEMWBS scores. Reduced to null after adjustment | No statistically significant associations to report | N/A | Good | |

| Maas et al., 2009, The Netherlands [47] | Cross-sectional Survey | 12–65+ | 10,089 | %greenspace within 1 and 3km buffers | GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Ethnicity, SES, Living Conditions, Health Insurance, Life Events in Last Year. Local: Level of Urbanity | Multilevel Linear Regression | More surrounding greenspace: lower GHQ score. Stronger association for 1km than 3km | C, SE: 1km: -0.005, 0.002 3km: -0.004, 0.002 |

N/A | Good | |

| Taylor et al., 2018, Australia and New Zealand [48] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–75+ | 1,819 | Amount of greenspace in postcode Urban areas only |

WHO-5 | Hedonic Wellbeing | NO | Linear Regression | Higher amounts of greenspace: higher WHO-5 scores. Only for 2 sample cities, remaining 2 insignificant | C: Melbourne: 1.410 Sydney: 2.470 |

N/A | Poor No controls |

|

| Triguero-Mas et al., 2015, Spain [49] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 8,793 | Amount of greenspace within 300m buffer Sensitivity analysis with other buffers |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Birth Place, Marital, SES, Health Insurance. Local: SES | Logistic Regression | Higher amounts of greenspace: lower odds of higher GHQ score Consistent results for all buffers |

Odds, CI: Males: 0.820, 0.700–0.980 Females: 0.770, 0.670–0.880 |

Stronger association for males than females | Fair | |

| Triguero-Mas et al., 2017, Europe [50] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–75 | 403 | Amount of greenspace within 300m buffer, Urban areas only |

SF-36 Mental Component Survey | Mental Health | Individual: Demographic | Linear Regression | No association for surrounding greenspace. | No Statistical Results to report | Stronger association for males than females | Fair | |

| Vemuri and Costanza, 2006, International [51] | Ecological Analysis | NOT GIVEN | 172 Countries | Ecosystem services product (ESP), per square kilometre for each country, normalised. From amount of each land-cover and multiplied by ecosystem services per country. | Life Satisfaction | Life Satisfaction | NO | Linear Regression | Better natural capital: higher life satisfaction | Odds, SE: 2.453, 0.739 | N/A | Poor No controls, high-level analysis |

|

| Ward Thompson et al., 2014, Scotland [52] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 305 | Amount of greenspace “around each home”, perceptions of local greenspace, Urban areas only |

SWEMWBS | Mental Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, Income, Deprivation | Linear Regression | Perceptions of having sufficient local greenspace: better mental wellbeing Satisfaction with quality: higher mental wellbeing |

No Statistical Results to Report | N/A | Fair | |

| White et al., 2013, England [24] | Cross-Sectional Survey | Under 25-over75 | 12,818 (GHQ) 10,168 (Life Satisfaction) |

% greenspace in each LSOA, including private gardens, Urban areas only |

Life Satisfaction, GHQ | Life Satisfaction, Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Health, Commuting. Local: IMD | Linear Regression | Higher percentage of greenspace: decreased GHQ, increased Life Satisfaction | C, SE: GHQ: -0.004, 0.001 Life Satisfaction: 0.002, 0.001 |

N/A | Good | |

| White et al., 2013, England [25] | Cross-Sectional Survey | Under 25-over75 | 15,361 | % greenspace in each LSOA, including private gardens | Life Satisfaction, GHQ | Life Satisfaction, Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Health, Commuting. Local: IMD | Linear Regression | Higher percentage of greenspace: decreased GHQ | C, SE: GHQ (reversed): Greenspace: 0.003, 0.001 |

N/A | Good | |

| Wood et al., 2017, Australia [53] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 492 | Amount and number of public greenspaces within 1.6km buffer, type of greenspace: sports, recreational, natural Urban areas only |

SWEMWBS | Mental Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, SES | Linear Regression | Number of parks: higher mental wellbeing. Strongest association for largest parks, decreasing with size. Greater area of parks: higher mental wellbeing scores Strongest association for sports spaces |

C, SE: Number of parks: 0.110, 0.050 Hectare increase of park area: 0.070, 0.020 Number of sports spaces: 0.430, 0.210 Number of recreational spaces: 0.110, 0.050 Number of natural spaces: 0.110, 0.050 |

N/A | Fair | |

| b) Greenspace Types | |||||||||||||

| Alcock et al., 2015, England [38] | Longitudinal Cohort Study | under 25- over 75 | 2,020 214 movers |

10 land-cover types Rural areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Health Commuting. Local: IMD | Multilevel Linear Regression | Cross-sectional differences: no association. Longitudinal differences for movers: significant, positive associations with increase access individually to Arable, Improved Grassland, Semi-natural Grassland, Mountain, Heath and Bog, and Coastal land cover. |

C, SE: Within-individual: Arable: 0.083, 0.037 Improved Grassland: 1.351, 0.040 Semi-natural Grassland: 0.152, 0.062 Mountains/Heath: 1.667, 0.074 |

N/A | Good | |

| Annerstedt et al., 2012, Sweden [54] | Longitudinal Cohort Study | 18–80 | 7,549 residents who did not relocate during survey | Presence of 5 green qualities within 300m buffer: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture Rural areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Country of Origin, Marital, Financial Strain, Physical Activity | Logistic Regression | Presence of Serene: lower GHQ score, only for those engaged in physical activity Presence of Spacious: lower GHQ, only for women engaged in physical activity |

Odds, CI: Women with Access to Serene: 0.200, 0.060–0.900 | Positive interaction between being physical activity and serene greenspace Positive interaction between being physical activity and serene greenspace, for women |

Good | |

| Bjork et al., 2008, Sweden [18] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 19–76 | 24,819 | Number of 5 green qualities within 100 and 300m buffers: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture Rural areas only |

SF-36 Vitality Component Survey | Vitality | Individual: Demographic, SES, Financial Strain, Smoking | Logistic Regression | More green qualities within 300m: better vitality, only for women More green qualities within 100m: no association Individual qualities: no association |

Odds and CI, women with access to number of qualities: 4–5: 1.070, 0.880–1.290 3: 1.220, 1.060–1.410 2: 1.060,0.940–1.190 |

Interactions with gender | Good | |

| Luck et al., 2011, Australia [55] | Cross-sectional Survey | All ages | 1,043 | Residential neighbourhood greenspace aspects:, vegetation cover, vegetation density, Urban areas only |

Subjective Wellbeing | Subjective Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, SES, Living Conditions, General Activity | Multilevel Linear Regression | Higher levels of species richness, species abundance, vegetation cover, vegetation density: better subjective wellbeing, strongest for vegetation | C, SE: Vegetation Cover: 0.560, 0.260 Vegetation Density: 0.800, 0.390 |

N/A | Good | |

| MacKerron and Mourato, 2013, UK [56] | Cross-Sectional Survey | All ages | 21,947 | Land cover types | Happiness | Happiness | NO | Linear Regression | All outdoor land cover types: better happiness than continuous urban areas. Marine and coastal areas have happiest scores. | C, SE: Mountains/moors: 2.710, 0.870 Woodland: 2.120, 0.340 Semi-natural grassland: 2.040, 0.350 Suburban/rural: 0.880, 0.160 |

N/A | Fair | |

| Sugiyama et al., 2008, Australia [57] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 20–65 | 1,895 | Neighbourhood Environment Walkability Scale, Urban areas only |

SF-36 Mental Component Survey | Mental Health | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Walking, Social Interaction | Logistic Regression | Higher reported greenness: better mental health | Odds, CI: High Perceived Greenness: 1.270, 0.990–1.620 |

N/A | Good | |

| Van den Bosch et al., 2015, Sweden [58] | Longitudinal Cohort Study | 18–80 | 1,419 residents who relocated during survey | Amount and presence of greenspace within 300m buffer: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture, Rural areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Deprivation, Marital, Education | Logistic Regression | Gained access to Serene greenspace: improved mental health among women. No other associations | Odds, CI: Access to Serene: 2.800, 1.110–7.040 |

Associations only for females, not males | Good | |

| Vemuri et al., 2011, USA [59] | Cross-sectional Survey | 18–65+ | 1,361 | Neighbourhood satisfaction, quality of neighbourhood natural environment, amount of tree cover per census block, Urban areas only |

Life Satisfaction | Life Satisfaction | Individual: Demographic, Ethnicity, Marital, Living Conditions, Social Capital | Logistic Regression | Stronger perceived environmental quality: improved life satisfaction Perceived shows stronger association than objective measures |

C, SE: 0.276, 0.514 | N/A | Good | |

| Weimann et al., 2015, Sweden [60] | Longitudinal Cohort Study | 18–80 | 9,444 | Number of 5 green qualities within local 1km2 area: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture | GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions BMI, Smoking | Multilevel Logistic Regression | Within-individual difference of higher neighbourhood greenness: lower psychological distress | Odds, CI: Within-Individual: 1.030, 1.000–1.160 Between-Individuals:1.070, 1.000–1.140 |

N/A | Good | |

| Wood et al., 2017, Australia [53] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 492 | Amount and number of public greenspaces within 1.6km buffer, type of greenspace: sports, recreational, natural Urban areas only |

SWEMWBS | Mental Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, SES | Linear Regression | Number of parks: higher mental wellbeing. Strongest association for largest parks, decreasing with size. Greater area of parks: higher mental wellbeing scores Strongest association for sports spaces |

C, SE: Number of parks: 0.110, 0.050 Hectare increase of park area: 0.070, 0.020 Number of sports spaces: 0.430, 0.210 Number of recreational spaces: 0.110, 0.050 Number of natural spaces: 0.110, 0.050 |

N/A | Fair | |

| c) Views of Greenspace | |||||||||||||

| Gilchrist et al., 2015, Scotland [61] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 16–55+ | 366 | Workplace view naturalness, view satisfaction, extent of features in view Urban areas only |

SWEMWBS | Mental Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, Job Type, Greenspace Use in Leisure Time. Local: Location | Linear Regression | No association for view naturalness Satisfaction with view, views of trees/bushes/flowering plants: higher SWEMWBS score Types strongest predictors |

C, SE: View of Trees: 0.616, 0.198 View bushes/flowers: 0.610, 0.312 View Satisfaction: 0.802, 0.215 |

N/A | Good | |

| Pretty et al., 2005, UK [20] | Controlled Case Study | 18–60 | 100 | Running while exposed to photographs: urban/rural pleasant and unpleasant | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire, Profile of Mood States | Self-Esteem, Mood | NO | N/A | Viewing pleasant scenes: increase in self-esteem | No Statistical Results to Report | N/A | Fair | |

| Vemuri et al., 2011, USA [59] | Cross-sectional Survey | 18–65+ | 1,361 | Number of trees visible from residence Urban areas only |

Life Satisfaction | Life Satisfaction | Individual: Demographic, Ethnicity, Marital, Living Conditions, Social Capital | Logistic Regression | Perceived shows stronger association than objective measures | No Statistical Results to Report | N/A | Good | |

| d) Visits to Greenspace | |||||||||||||

| Duvall and Kaplan, 2014, USA [62] | Uncontrolled Case Study | 20–50+ | 73 | Wilderness Expedition, Rural areas only |

AFI, PANAS | Attention, Affect | Individual: Demographic, SES, Physical and Mental Health History, Veteran History | Linear Mixed Models | Post expedition: more positive affect and better attentional functioning Follow-up: better positive affect |

Score Change: AFI: 0.340 Affect: 0.270 |

N/A | Poor Small sample, allocation based on intervention |

|

| Dzhambov et al., 2018, Bulgaria [45] | Cross- Sectional Survey | 15–25 | 399 | Amount of green land within 500m of home, Euclidean distance to nearest greenspace, perceived neighbourhood greenness and quality, travel time to and time spent in neighbourhood greenspace Urban areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, SES, Living Conditions, Noise. Local: Population Density | Linear Mixed Models and Linear Mediation Models | Perceived greenness and quality, and travel time to greenspace: lower GHQ scores. No statistically significant associations for objective greenspace measures. |

C, CI: Perceived greenness: -0.59, -0.85- -0.32 <5min to greenspace: -2.54, -3.96 - -1.12 Greenspace quality: -0.08, -0.12 - -0.04 |

Higher perceived restorative quality was associated with more physical activity and social cohesion, which was associated with lower GHQ scores. For objective measures, this held for all but the greenspace quality measure. | Fair | |

| Gilchrist et al., 2015, Scotland [61] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 16–55+ | 366 | Workplace greenspace visit frequency, weekly use duration Urban areas only |

SWEMWBS | Mental Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, Job Type, Greenspace Use in Leisure Time. Local: Location | Linear Regression | No association for use frequency Time spent in workplace greenspace, satisfaction with view, views of trees/bushes/flowering plants: higher SWEMWBS score Types strongest predictors |

C, SE: Use Duration: 0.431, 0.191 |

N/A | Good | |

| Herzog and Stevey, 2008, USA [63] | Cross-Sectional Survey | University Students | 823 | Self-reported typical contact with nature | Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-Being, Attention, PANAS | Mental Wellbeing, Attention, Affect | Individual: Sense of humour | Linear Regression | Greater contact with nature: better personal development, effective functioning. | C: Personal Development: 0.090 Effective Functioning: 0.230 |

N/A | Fair | |

| Jakubec et al., 2016, Canada [64] |

Uncontrolled Case Study | Adults | 37 | Visits to greenspace, Rural areas only |

Quality of Life Inventory | Quality of Life | NO | Score Change | Post-Intervention: improved quality of life, not statistically significant | Score Change: Satisfaction with love: +1.000 Satisfaction with life: -1.000 |

N/A | Poor No controls, participants aware of intervention |

|

| Kamitsis and Francis, 2013, Australia [65] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–69 | 190 | Nature Exposure, CNS | WHOQOL-BREF | Quality of Life | Individual: Spirituality | Linear Regression | Higher nature exposure or connection to nature: better quality of life | C: Exposure: 0.280 CNS: 0.330 |

N/A | Poor Minimal controls |

|

| Marselle et al., 2013, UK [66] | Controlled Case Study | Adults, mostly over 55 | 708 | Group walks in different environments: natural and semi-natural, green corridors, farmland, parks and gardens, urban, coastal, amenity greenspace, allotments, outdoor sports facilities, other | WEMWBS, PANAS | Mental Wellbeing, Affect | Individual: Demographic, Marital, Education, Deprivation | Multilevel Linear Regression | Walks in farmland: better mental wellbeing No associations with other greenspace types |

C, SE: Walks in farmland: 2.790, 0.003 |

N/A | Fair | |

| Marselle et al., 2015, UK [67] | Cross-Sectional Survey | Adults, mostly over 55 | 127 | Walking: environment type, perceived naturalness, perceived biodiversity, perceived restorativeness, duration of walk, perceived walk intensity | Happiness, PANAS | Happiness, Affect | NO | Multilevel Linear Regression | Perceived restorativeness, perceived walk intensity: positively associated with affect and happiness. | C, SE: Affect: 0.126, 0.014 Happiness: 0.029, 0.003 |

N/A | Poor No controls, participants aware of intervention |

|

| Mitchell, 2013, Scotland [19] | Cross-sectional Survey | 16+ | 1,890 | Frequency of use of different environment types for physical activity | WEMWBS, GHQ | Mental Wellbeing, Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Income, Physical Activity. Local: Level of Urbanity | Linear Regression | Regular use of open space/park or woods/forest: lower GHQ score Regular use of natural environments: no clear association with mental wellbeing Regular use of non-natural environments: better mental wellbeing |

Odds, CI: GHQ: Park >1 a week: 0.570, 0.369–0.881 Woods >1 a week: 0.557, 0.323–0.962 WEMWBS: Park <1 a week: 2.442, 0.769–4.115 |

N/A | Good | |

| Molsher and Townsend, 2016, Australia [68] | Uncontrolled Case Study | 14–71 | 32 | Engagement with 10 week Environmental Volunteering Project, Rural areas only |

General Wellbeing Scale, PANAS | Wellbeing, Affect | NO | Score Change | Post-intervention and Follow-up: improved wellbeing and mood state scores | Score Change: Wellbeing: +11.600 | N/A | Poor No controls, participants aware of intervention |

|

| Nisbet and Zekenski, 2011, Canada [69] | Controlled Case Study | 16–48 | 150 | Walking indoors or outdoors in nature, Nature Relatedness Urban areas only |

Happiness, PANAS | Happiness, Affect | NO | T-Tests | Walking outdoors: more positive affect, relaxation and fascination | T-Test: Outdoor Walk: Affect: 4.860 Relaxation: 4.570 Fascination: 4.800 |

N/A | Fair | |

| Panno et al., 2017, Italy [70] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 115 | Self-reported greenspace visit frequency | WHO-5 | Hedonic Wellbeing | Individual: Demographics, SES | Hierarchical Regression | Higher reported frequency of greenspace visits: greater wellbeing scores. Not statistically significant. | No Statistically Significant Results to Report | N/A | Fair | |

| Richardson et al., 2016, UK [71] | Uncontrolled Case Study | 18–71 | 613 | Nature in Self, Engagement with “30 Days Wild” Programme | Happiness | Happiness | NO | T-Tests | Post-intervention, increased nature connection, increased general happiness | T-Tests: 6.650 | N/A | Fair | |

| Triguero-Mas et al., 2017, Europe [50] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–75 | 403 | Frequency of contact with greenspace in terciles Urban areas only |

SF-36 Mental Component Survey | Mental Health | Individual: Demographic | Linear Regression | Lower frequency of greenspace visits: poorer mental health. Stronger associations for males | C, CI for “low” contact Males: -9.140, -14.420 - -3.860 Females: -5.000, -9.790- -0.021 |

Stronger association for males than females | Fair | |

| Van den Berg et al., 2016, Spain, The Netherlands, Lithuania, UK [21] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–75 | 3,748 | Reported hours of greenspace visits in last month, Urban areas only |

SF-36 Mental Component Survey | Mental Health | Individual: Demographic, SES, Living Conditions, Childhood Nature Experience | Multilevel Linear Regression | Higher visits to greenspace: better mental health | C, CI: 0.030, 0.020–0.040 |

N/A | Good | |

| Ward Thompson et al., 2014, Scotland [52] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 305 | Patterns of greenspace use Urban areas only |

SWEMWBS | Mental Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, Income, Deprivation | Linear Regression | No association between greenspace use and mental wellbeing | No Statistical Results to Report | N/A | Fair | |

| White et al., 2017, England [72] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 7,272 | Did the individual visit greenspace yesterday. Amount of time spent outdoors Urban areas only |

ONS4 | Mental Wellbeing | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Health, Commuting. Local: IMD | Logistic Regression | Visiting a greenspace yesterday: higher happiness Spending time outdoors: more frequently associated with higher worth, decreasing with frequency |

C, CI: Visited greenspace yesterday, happiness: 1.660, 1.320–2.080 Spending time outdoors everyday day, compared to never, worth: 1.960, 1.490–2.580 |

N/A | Good | |

| e) Greenspace Accessibility | |||||||||||||

| Bjork et al., 2008, Sweden [18] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 19–76 | 24,819 | Number of 5 green qualities within 100 and 300m buffers: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture Rural areas only |

SF-36 Vitality Component Survey | Vitality | Individual: Demographic, SES, Financial Strain, Smoking | Logistic Regression | More green qualities within 300m: better vitality, only for women More green qualities within 100m: no association Individual qualities: no association |

Odds and CI, women with access to number of qualities within 300m: 4–5: 1.070, 0.880–1.290 3: 1.220, 1.060–1.410 2: 1.060,0.940–1.190 |

Interactions with gender | Good | |

| Bos et al., 2016, The Netherlands [43] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–87 | 4,924 | % greenspace within 1km and 3km buffers | Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life | Quality of Life | Individual: Demographic, Country of Origin, Marital, SES | Linear Regression | More greenspace within 3km: better quality of life, significant interactions for age and gender. For middle aged men, inverse association Greenspace within 1km: no association |

C, SE: 1km: 5.200, 5.500. 3km: 6.300, 4.500 |

Interactions for life course and gender | Poor Limited Statistical reporting |

|

| Dadvand et al., 2016, Spain [73] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–65+ | 3461 | % greenspace within 100m, 250m and 500m buffers, subjective presence of greenspace within 10 minute walk, objective presence of greenspace within 200m of minimum 5000m2 Urban areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress |

Individual: Demographic, SES, Social Support, Physical Activity Local: Deprivation |

Logistic Regression |

More greenspace nearer to home: lower GHQ score. Effect sizes decreasing with distance. Greater subjective and objective proximity to greenspace: lower GHQ scores |

Odds, CI: 100m: 1.320, 1.160–1.510 250m: 1.250, 1.100–1.400 500m: 1.170, 1.040–1.320 Subjective proximity: 1.300, 1.040–1.630 Objective proximity: 1.200, 0.970–1.480 |

N/A | Good | |

| Dzhambov et al., 2018, Bulgaria [45] |

Cross- Sectional Survey | 15–25 | 399 | Amount of green land within 500m of home, Euclidean distance to nearest greenspace, perceived neighbourhood greenness and quality, travel time to greenspace Urban areas only |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, SES, Living Conditions, Noise. Local: Population Density | Linear Mixed Models and Linear Mediation Models | Travel time to greenspace: lower GHQ scores. No statistically significant associations for objective greenspace measures. |

C, CI: <5min to greenspace: -2.54, -3.96 - -1.12 |

Lower travel time to greenspace was associated with more physical activity and social cohesion, which was associated with lower GHQ scores.. | Fair | |

| Krekel et al., 2015, Germany [74] | Cross-sectional Survey | 17–99 | NOT GIVEN | Euclidean distance from home to green and abandoned areas Urban areas only |

SF-36 Mental Component Survey | Mental Health | Individual: Demographic, Country of Origin, Marital, SES, Living Conditions, Disabilities | Linear Regression | Access to urban greenspaces: better mental health Access to abandoned areas: poorer mental health |

C: Greenspace: 0.007 |

N/A | Good | |

| Maas et al., 2009, The Netherlands [47] | Cross-sectional Survey | 12–65+ | 10,089 | %greenspace within 1 and 3km buffers | GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Ethnicity, SES, Living Conditions, Health Insurance, Life Events in Last Year. Local: Level of Urbanity | Multilevel Linear Regression | More surrounding greenspace: lower GHQ score. Stronger association for 1km than 3km | C, SE: 1km: -0.005, 0.002 3km: -0.004, 0.002 |

N/A | Good | |

| Sugiyama et al., 2008, Australia [57] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 20–65 | 1,895 | Neighbourhood Environment Walkability Scale, Urban areas only |

SF-36 Mental Component Survey | Mental Health | Individual: Demographic, Marital, SES, Walking, Social Interaction | Logistic Regression | Higher reported greenness: better mental health | Odds, CI: High Perceived Greenness: 1.270, 0.990–1.620 |

N/A | Good | |

| Triguero-Mas et al., 2015, Spain [49] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 8,793 | Amount of greenspace within 100m, 300m, 500m and 1km buffers, presence of green and blue spaces within buffer Sensitivity analysis with other buffers |

GHQ-12 | Psychological Distress | Individual: Demographic, Birth Place, Marital, SES, Health Insurance. Local: SES | Logistic Regression | Higher amounts of greenspace: lower odds of higher GHQ score Consistent results for all buffers |

Odds, CI: Males: 0.820, 0.700–0.980 Females: 0.770, 0.670–0.880 |

Stronger association for males than females | Fair | |

| f) Subjective Connection to Nature | |||||||||||||

| Cervinka et al., 2012, Austria [75] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 15–87 | 547 | CN-SI* | SF-36 Component Surveys, SWLS, WHOQOL-BREF | Quality of Life, Life Satisfaction | Individual: Demographic | Linear Regression | Higher CN-SI Score: better meaningfulness, mental health, vitality and emotional-role function | C: Meaningfulness: 0.210 Mental Health: 0.180 Vitality: 0.230 Emotions: 0.190 |

N/A | Poor Limited sampling description |

|

| Howell et al., 2011, Canada [76] | Cross-Sectional Survey | University Students | 452 | CNS* | Keyes’ Index of Well-Being and Mindful Attention Awareness Scale | Mental Wellbeing, Attention | NO | Linear Regression | Greater connection to nature: greater psychological wellbeing and social wellbeing. Not associated with emotional wellbeing or mindfulness | C: Psychological Wellbeing: 0.150 Social Wellbeing: 0.200 |

N/A | Poor No controls, minimal reporting |

|

| Howell et al., 2013, Canada [77] | Cross-Sectional Survey | University Students | 311 | CNS, Nature Relatedness Scale* | Emotional Wellbeing, Steen Happiness Index, Meaning in Life Questionnaire, Meaningful Life Measure, General Life Purpose Scale | Mental Wellbeing, Happiness, Meaning in Life | NO | Linear Regression | Greater connection to nature: better reported wellbeing, meaning in life | C: Meaning: 0.310 Purpose: 0.250 Happiness: 0.220 Emotional Wellbeing: 0.200 Psychological Wellbeing: 0.250 Social Wellbeing: 0.260 |

N/A | Poor No controls, minimal reporting |

|

| Kamitsis and Francis, 2013, Australia [65] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–69 | 190 | Nature Exposure, CNS | WHOQOL-BREF | Quality of Life | Individual: Spirituality | Linear Regression | Higher nature exposure or connection to nature: better quality of life | C: Exposure: 0.280 CNS: 0.330 |

N/A | Poor Minimal controls |

|

| Nisbet et al., 2011, Canada [78] | Cross-Sectional Survey | Adults, student subgroup | 184, 145,in two studies | Nature Relatedness Scale, New Ecological Consciousness Scale | Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Inventory, SWLS, PANAS | Mental Wellbeing, Life Satisfaction, Affect | NO | Linear Regression | Higher nature relatedness: better wellbeing, positive affect, purpose in life. No association for life satisfaction. | C: Study 1: Affect: 0.330 Purpose: 0.230 Study 2: Affect: 0.220 Purpose: 0.240 |

N/A | Fair | |

| Zelenski et al., 2014, Canada [79] | Cross-Sectional Survey | NOT GIVEN | 950 | Nature Relatedness Scale, Inclusion of Nature in Self | Ryff’s PWBI, SWLS, Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), PANAS | Mental Wellbeing, Life Satisfaction, Happiness, Affect | NO | Linear Regression | Stronger connection to nature: improved wellbeing, happiness, life satisfaction and affect | C: Wellbeing: 0.250 Happiness: 0.360 Life Satisfaction: 0.310 Affect: 0.380 |

N/A | Poor No controls |

|

| Zhang et al., 2014, USA [80] | Cross-Sectional Survey | 18–88 | 1,108 | CNS, Engagement with Natural Beauty Scale | SWLS | Life Satisfaction | Individual: Demographic, Personality | Multilevel Linear Regression | Higher connectedness with nature: improved life satisfaction, only for those reporting being attuned to nature’s beauty | C, CI: Connectedness: 0.1000, -0.990–0.109 Engagement: 0.155, 0.121–0.344 ConnectednessXENGAGEMENT: 0.080, 0.170–0.151 |

Positive interaction between connectedness to nature and being attuned to nature’s beauty | Good | |

*LSOA, Lower-Layer Super Output Area, a census-based spatial unit. CD, Census District, a census-based spatial unit.

*CNS, Connectedness to Nature Scale, measure of individuals’ trait levels of feeling emotionally connected to the natural world. CN-SI, single-item version of CNS. Nature Relatedness Scale, affective, cognitive, and experiential aspects of individual’s connection to nature

**All associations described in this table are statistically significant, unless otherwise specified

Table 3. Greenspace measures employed in included studies.

| Study | Greenspace Type | Measure Type | Metrics Used | Spatial Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a) Amount of Local-Area Greenspace | ||||

| Alcock et al., 2015 [38] | Natural Land Cover | Land Cover Map | Proportion of area that is greenspace | LSOA |

| Alcock et al., 2014 [23] | Greenspace and Private Gardens | Generalised Land Use Database (GLUD) | Proportion of area that is greenspace | LSOA |

| Ambrey and Fleming, 2014 [39] | Public Greenspace (including public parks, community gardens cemeteries, sports fields, national parks and wilderness areas) | GIS | Proportion of area that is greenspace | Census District |

| Ambrey, 2016 [40] | Public Greenspace (including public parks, community gardens cemeteries, sports fields, national parks and wilderness areas) | GIS | Amount of greenspace per Capita | Census District |

| Ambrey, 2016 [41] | Public Greenspace (including public parks, community gardens cemeteries, sports fields, national parks and wilderness areas) | GIS | Amount of greenspace per Capita | Census District |

| Ambrey, 2016 [42] | Public Greenspace (including public parks, community gardens cemeteries, sports fields, national parks and wilderness areas) | GIS | Amount of greenspace per Capita | Census District |

| Astell-Burt et al., 2014 [17] | Green and Natural Environment (excluding water and private gardens) | Land Use Database | Proportion of area that is greenspace | Ward |

| Bos et al., 2016 [43] | Greenspace (urban green including vegetable gardens, sports areas >0.5ha, parks >1ha; and rural green including agricultural and natural green) | Dutch Land Use Database and GIS | Proportion of area that is greenspace | 1km and 3km buffers of postcode centroid |

| De Vries et al., 2003 [5] | Greenspace (urban green, agricultural green, forests and nature areas) | National Land Use Classification Database and GIS | Proportion of area that is greenspace | 3km around centre of neighbourhood unit |

| De Vries et al., 2013 [44] | All types of visible vegetation, and quality based on variation, maintenance, orderly arrangement, absence of litter and general impression of greenspace | On-street Audit | Level of greenness (1- the street does not make a very green impression, to 5- the street makes a very green impression) | Average street greenness of neighbourhood unit |

| Dzhambov et al., 2018 [45] | Green land cover | NDVI | Proportion of area that is greenspace | 500m Euclidean buffer of home |

| Greenspace (parks, gardens, street trees) | Self-reported | Perceived neighbourhood greenness and quality, travel time to and time spent in neighbourhood greenspace, green views from home | Self-reported neighbourhood | |

| Houlden et al., 2017 [46] | Greenspace | Generalised Land Use Database (GLUD) | Proportion of area that is greenspace | LSOA |

| Maas et al., 2009 [47] | Greenspace (urban green, agricultural green, forests and nature areas) | National Land Use Classification Database and GIS | Proportion of area that is greenspace | 1km and 3km buffer around individual’s home |

| Taylor et al., 2018 [48] | Green land cover | NDVI | NDVI value | Postcode |

| Triguero-Mas et al., 2015 [49] | Green land cover | NDVI | Amount of greenspace | 300m Euclidean buffer of postcodes |

| Triguero-Mas et al., 2017 [50] | Green land cover | NDVI | Amount of greenspace | 300m Euclidean buffer of postcodes |

| Vemuri and Costanza, 2006 [51] | Land Cover Types | Land Cover Map | Ecosystem Services Product (amount of each land cover, multiplied by ecosystem services per country) | Country |

| Ward Thompson et al., 2014 [52] | Greenspace (parks, woodlands, scrub and other publicly accessible natural environments) | GIS | Amount of Greenspace | Neighbourhood unit |

| White et al., 2013 [24] | Greenspace and Private Gardens | Generalised Land Use Database (GLUD) | Proportion of area that is greenspace | LSOA |

| White et al., 2013 [25] | Greenspace and Private Gardens | Generalised Land Use Database (GLUD) | Proportion of area that is greenspace | LSOA |

| Wood et al., 2017 [53] | Greenspace (parks and other areas of green public open spaces) | Land Cover Map | Amount and number of parks | 1.6km road network buffer |

| b) Greenspace Types | ||||

| Alcock et al., 2015 [38] | Land Cover Types (broadleaf woodland, coniferous woodland, arable, improved grassland, semi-natural grassland, mountain, heath and bog, saltwater, freshwater, coastal, built-up areas including gardens) | Land Cover Map | Proportion of area of each type | LSOA |

| Annerstedt et al., 2012 [54] | 5 qualities: Serene (place of peace, silence and care), Wild (place of fascination with wild nature), Lush (place rich in species), Spacious (place offering a restful feeling of entering another world), Culture (the essence of human culture) | CORINE Land Cover and GIS | Presence of each type | 3km Euclidean buffer from home |

| Bjork et al., 2008 [18] | 5 qualities: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture | CORINE Land Cover and GIS | Presence of each type | 100 and 300m Euclidean buffers from home |

| Luck et al., 2011 [55] | Vegetation Cover (woody and non-woody vegetation) | Advanced Land Observation Satellite | Proportion of vegetation | Census District |

| Vegetation Density (understory, mid-story and over-story cover) | Field Survey | Proportion of vegetation | Census District | |

| MacKerron and Mourato, 2013 [56] | Land Cover Classes (marine and coastal, freshwater and wetlands, mountains and moors and heathland, semi-natural grasslands, farmland, coniferous woodland, broadleaf woodland, bare ground, suburban/rural development, continuous urban) | Land Cover Map | Type | Current GPS location |

| Sugiyama et al., 2008 [57] | Neighbourhood Greenness | Self-Reported | Level of greenness | Neighbourhood unit |

| Van den Bosch et al., 2015 [58] | 5 qualities: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture | CORINE Land Cover and GIS | Amount and presence of each type | 300m Euclidean buffer from home |

| Vemuri et al., 2011 [59] | Natural environment quality and satisfaction | Self-Reported | Perceptions of neighbourhood | Neighbourhood |

| Weimann et al., 2015 [60] | 5 qualities: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture | CORINE Land Cover and GIS | Presence of each type | 5–10 minute walk from homes |

| Wood et al., 2017 [53] | Sports, recreational, and natural green spaces | Land Cover Map | Amount and presence of each type | 1.6km network buffer of homes |

| Views of Greenspace | ||||

| Gilchrist et al., 2015 [61] | Workplace greenspace | Self–Reported | Perceptions of view of greenspace naturalness and extent | Workplace |

| Pretty et al., 2005 [20] | Rural pleasant and unpleasant scenes Urban pleasant and unpleasant scenes |

Lab environment setting | Photographs | Photographs of views |

| Vemuri et al., 2011 [59] | Number of trees visible from home | Self-Reported | Perceptions of neighbourhood | Individual |

| c) Visits to Greenspace | ||||

| Duvall and Kaplan, 2014 [62] | Wilderness | Objective | Exposure through expedition | Individual |

| Dzhambov et al., 2018 [45] | Parks and gardens | Self-Reported | Time spent in greenspace | Self-reported Neighbourhood |

| Gilchrist et al., 2015 [61] | Workplace greenspace | Self–Reported | Frequency and duration of greenspace exposure | Workplace |

| Herzog and Stevey, 2008 [63] | Nature | Self-Reported | Typical contact | Individual |

| Jakubec et al., 2016 [64] | Wilderness | Objective | Exposure through expedition | Individual |

| Kamitsis and Francis, 2013 [65] | Nature | Self-Reported | Level of exposure | Individual |

| Marselle et al., 2013 [66] | Natural and semi-natural, green corridors, farmland, parks/gardens, urban, coastal, amenity green space, allotments, outdoor sports facilities, other | Land Use Database | Walking while exposed to different environments | Individual |

| Marselle et al., 2015 [67] | Natural and semi-natural, green corridors, farmland, parks/gardens, urban, coastal, amenity green space, allotments, outdoor sports facilities, other | Land Use Database, | Duration of walk and environment type | Individual |

| Natural and semi-natural, green corridors, farmland, parks/gardens, urban, coastal, amenity green space, allotments, outdoor sports facilities, other | Self-Reported | Perceived naturalness, biodiversity, restorativeness, walk intensity | Individual | |

| Mitchell, 2013 [19] | Woodland/forest, open space/park, country paths, beach/river, sports field/courts, swimming pool, gym/sports centre, pavements, home/garden, other, none | Self-Reported | Frequency of use of different greenspace types for physical activity | Individual |

| Molsher and Townsend, 2016 [68] | Rural nature | Objective | Engagement with 10-week Environmental Volunteering Project | Individual |

| Nisbet and Zekenski, 2011 [69] | Outdoors (in nature) | Objective | Walking indoors vs outdoors | Individual |

| Panno et al., 2017 [70] | Greenspace | Self-Reported | Greenspace visit frequency | Individual |

| Richardson et al., 2016 [71] | Nature | Self-Reported | Engagement with 100 days wild programme | Individual |

| Triguero-Mas et al., 2017 [50] | Natural outdoor environment | Urban Atlas, CORINE Land Cover and GIS | Duration of exposure to nature | Individual |

| Van den Berg et al., 2016 [21] | Greenspace (Public and private open spaces that contain “green” and/or “blue” natural elements such as street trees, forests, city parks and natural parks/reserves) | Self-Reported | Duration of visits to greenspace | Individual |

| Ward Thompson et al., 2014 [52] | Greenspace (parks, woodlands, scrub and other publicly accessible natural environments) | Self-Reported | Frequency of greenspace visits | Individual |

| White et al., 2017 [72] | Greenspace | Self-Reported | Having visited a greenspace yesterday | Individual |

| d) Greenspace Accessibility | ||||

| Bjork et al., 2008 [18] | 5 qualities: Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Culture | CORINE Land Cover and GIS | Presence of each type | 100 and 300m Euclidean buffer of home |

| Bos et al., 2016 [43] | Greenspace (urban green including vegetable gardens, sports areas >0.5ha, parks >1ha; and rural green including agricultural and natural green) | Dutch Land Use Database and GIS | Proportion of area that is greenspace | 1km and 3km Euclidean buffers of postcode centroid |

| Dadvand et al., 2016 [73] | Green land cover | NDVI | Proportion of area that is greenspace Presence of 5000m2 greenspace within 200m |

100m, 250m and 500m Euclidean buffer of home |

| Greenspace | Self-Reported | Proximity to greenspace | 10 minute walk from home | |

| Dzhambov et al., 2018 [45] | Greenspace (park, allotment, or recreational grounds) | OpenStreetMap and GIS | Proximity to greenspace | Euclidean distance from home |

| Krekel et al., 2015 [74] | Urban green areas (greens, forests, and waters), and abandoned urban areas | European Urban Atlas | Proximity to greenspace | Euclidean distance from home |

| Maas et al., 2009 [47] | Greenspace (urban green, agricultural green, forests and nature areas) | National Land Use Classification Database and GIS | Proportion of area that is greenspace | 1km and 3km Euclidean buffer of home |

| Sugiyama et al., 2008 [57] | Neighbourhood Greenness | Self-Reported | Access to park or nature reserve | Neighbourhood |

| Triguero-Mas et al., 2015 [49] | Green land cover | NDVI | Amount of greenspace | 100m, 300m, 500m, 1km Euclidean buffer of home |

| e) Subjective Connection to Nature | ||||

| Cervinka et al., 2012 [75] | Nature | Self-Reported | Connectedness to nature | Individual |

| Howell et al., 2011 [76] | Nature | Self-Reported | Connectedness to nature | Individual |

| Howell et al., 2013 [77] | Nature | Self-Reported | Connectedness to nature Nature relatedness |

Individual |

| Kamitsis and Francis, 2013 [65] | Nature | Self-Reported | Connectedness to nature | Individual |

| Nisbet et al., 2011 [78] | Nature | Self-Reported | Nature relatedness Ecological consciousness |

Individual |

| Zelenski et al., 2014 [79] | Nature | Self-Reported | Nature relatedness Inclusion of nature in self |

Individual |

| Zhang et al., 2014 [80] | Nature | Self-Reported | Connectedness to nature Engagement with natural beauty |

Individual |

Mental wellbeing measures

Only 14 studies were found to measure both hedonic and eudaimonic mental wellbeing, of which the most commonly used measure was the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) [19, 46, 52, 53, 61, 66]. WEMWBS includes 14 positively worded questions, regarding individual feelings over the past 2 weeks, including “feeling relaxed”, “interested in new things”, and “close to others” [81]; there is also a reduced 7-item version, known as SWEMWBS (Shortened-WEMWBS) [82]. The recent Personal Wellbeing ONS4, applied in to one study [72], measures individuals’ life satisfaction, happiness and anxiety (hedonic wellbeing) and sense of worth (eudaimonic wellbeing) [83].

The remaining 32 studies assessed outcomes considered to be aspects of mental wellbeing, such as quality of life, life satisfaction, and affect, but did not report both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index, used in 2 studies [48, 70], asks how frequently individuals have felt “cheerful and in good spirits” and “calm and relaxed”, over the previous 2 weeks, but focusses on hedonic rather than eudaimonic wellbeing [84].

Quality of life was measured in 6 studies, two using the WHOQOL-BREF [65, 75], a 26-item questionnaire covering physical and psychological health, social relationships and personal environment [85]. The SF-36 instrument measures quality of life with 36 physical, emotional and psychological health questions [86], and was used in 4 studies [41, 42, 44, 75]. A brief 12-item version (SF-12) has three subscales: mental health, vitality [18], and emotional-role functioning. The mental component summary (MCS), derived from a subset of emotional problems, wellbeing and social functioning questions, was used in 6 papers [21, 40, 50, 57, 74, 75], asking how often the individual recently felt “full of energy”, “nervous” and “happy” [86].

Single-item Life Satisfaction was used in 6 studies [24, 25, 40, 41, 51, 87]. The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) was applied to 4 studies [75, 78–80], and includes a more thorough 5 life-evaluation questions, which ask how ideal and satisfying the individual’s life is, and if they have “gotten the important things… in life” [88].

Happiness was measured with one question in 4 studies [56, 67, 69, 71]. The Attentional Functioning Index (AFI), which assesses daily functioning, was used in one study [62, 89].

Eight studies reported affect scores [62, 63, 66–69, 78, 79], which include positive feelings (happiness, interest), and negative emotions (anger, sadness), using the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) [90]. Similarly, The Profile of Mood States (POMS) asks about experiences of 65 different emotions, including some positive items, such as “lively” and “relaxed” [91], and was used in one study [20]. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) was used in 14 studies [5, 17, 19, 23–25, 38, 45, 47, 49, 54, 58, 60, 73]. It contains some positively worded items (“In the last 2 weeks I have… been able to concentrate”, “felt I have been playing a useful part” and “feeling reasonably happy”) but was designed and validated as a screening tool for psychiatric disorders, with higher scores indicative of greater distress [92]. Other studies which measured on poor mental health were excluded from this review.

Full details of the included studies are presented in Table 2, which is ordered by greenspace characteristic. Where articles cover multiple characteristics, the study appears under multiple headings.

Greenspace characteristics

Amount of local-area greenspace

21 studies examined associations between quantities of local-area greenspace and mental wellbeing, 2 of which were longitudinal. Most calculated the proportion of greenspace for each Lower-Layer Super Output Area (LSOA, a geographic area generated for being as consistent in population size as possible, with a minimum population of 1000 and the mean of 1500), Census District (CD), or within a defined radius of residents. Two articles measured greenspace area per capita. Of 15 studies, one was restricted to public greenspace [39], and 14 included only urban areas.

Only four (cross-sectional) studies measured hedonic and eudaimonic mental wellbeing (SWEMWBS and ONS4). No statistically significant association was reported between greenspace and mental wellbeing in three studies [46, 52, 72], although urban residents who reported “sufficient local greenspace” showed significantly higher SWEMWBS scores [52]. However, Wood et al.’s study found that a 1ha increase in park area within a 1.6km walk of an individual’s home showed a 0.070-point increases in SWEMWBS score [53]; this suggests that examining greenspace around individuals, rather than aggregating to local area, may better detect associations.

Five studies, 4 of which were Good quality and based in urban areas, found that life satisfaction was significantly higher in areas with more greenspace [24, 39, 41, 51], albeit with small linear effect sizes of 0.002–0.003 [24, 39]. The study by White et al. included a large sample, over 10,000 individuals, demonstrating a slight but significant association between LSOA greenspace proportions and life satisfaction. Another large study by the same authors found no significant association between mental wellbeing and the amount of rural local-area greenspace [25], suggesting that associations may differ between urban and rural environments.

An ecological analysis of over 172 countries measured the amount of green land cover per km2, adjusted for the nation’s size, finding a significant association with better life satisfaction. Despite the large sample size and strong odds ratios (2.450), the study was of poor methodological quality, due to its ecological design and hence inability to adjust for individual-level confounding [51]. Four studies also found the quantity of urban greenspace was associated with quality of life or mental health, characterised by the SF-36 scale and its sub-components [41–43, 74]; however, three others, which included only public urban greenspace, found no association [39, 44, 50]. Taylor et al. observed mixed results: the amount of urban greenspace was positively and significantly associated with hedonic wellbeing for two cities in Australia, but not two others in New Zealand [48].

Based on these Good quality studies, we conclude that there is adequate evidence for an association between local-area urban greenspace and life satisfaction, but not rural greenspace. Mixed results provide inadequate evidence for associations with quality of life, mental health, and multi-dimensional mental wellbeing.

GHQ was the outcome in 8 studies, of which 6 were Good quality and 3 were confined to urban areas. All but one [45] found an inverse association between the amount of greenspace and GHQ score [5, 17, 23–25, 47, 49, 50], implying reduced mental distress; again, linear regression coefficients varied considerably, from 0.003 to 0.431. The Fair quality study by Dzhambov et al., however, found no statistically significant association for objective greenspace quantities, but observed significantly lower GHQ scores for those with higher perceived greenness in their neighbourhood [45]. In a longitudinal study, Alcock et al. found that people moving to areas with higher greenspace proportions had significantly lower GHQ score after relocating, averaging 0.430 points lower 3 years post-move [23]. Therefore, there was adequate evidence for the inverse association between the amount of local-area greenspace and (lower) GHQ score.

Greenspace types

A total of 8 Good and 2 Fair quality studies classified greenspace according to greenspace types, using bespoke classification systems; no consensus was observed regarding greenspace typology. Four of these were longitudinal studies.

Only one Fair study measured hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing, with WEMWBS, comparing linear associations between the amount of sport, recreational and ‘natural’ spaces within a 1.6km buffer of the individual [53]. The strongest associations were observed for sports (0.430 increase in WEMWBS for each additional space), followed by recreational and natural spaces (0.110 each).

One research group conducted four studies (3 longitudinal) using the longitudinal Swedish Health Survey (SHS), based in suburban and rural areas. They classified public greenspace within 300m of each residents’ home into 5 aspects: Serene (quiet, audible ‘nature’), Wild (undeveloped, no visible human impact), Lush (biodiversity), Spacious (large cohesive area) and Cultural (cultural heritage, old trees) [18, 54, 58]. Two studies measured GHQ: the first found associations between Serene or Spacious greenspace and slightly, but significantly, lower GHQ scores for physically active individuals; however, associations with Spacious greenspace held only for women [54]. In the second, only women moving to areas with Serene greenspace had significantly lowered GHQ scores, but with much higher odds than in Annerstedt et al.’s work [58]. In a cross-sectional analysis, these authors found that the total number of green aspects (Serene, Wild, Lush, Spacious, Cultural) was associated with slightly better SF-36 Vitality scores for women [18]. The third longitudinal study found marginally but significantly lower GHQ scores for greater numbers of different green aspects, including those moving between areas [60].

In a cross-sectional study, based on 12,697 observations from 2,020 residents of rural England, no association was found between LSOA land cover classes and GHQ scores. However, individuals who relocated to areas with more arable, grass, ‘natural’, mountainous and heath land had significantly lower GHQ scores post-move [38].

Among 3 cross-sectional studies, urban residents with higher amounts of local vegetative or ‘natural’ greenspaces reported better mental wellbeing: vegetation density and cover, from field surveys and satellite imagery in Australia, were strongly and significantly associated with life satisfaction [55]. The number of trees, or an indicator of how ‘green’ the neighbourhood is, were significantly associated with better mental health (SF-36 Mental Component) and life satisfaction [57, 59]. Residents’ ratings of the ‘quality of their local natural environment’, on a scale of 0–10 (very dissatisfied to very satisfied), was associated with higher SF-36 Mental Component Summary scores [59].

A large cross-sectional study in the UK used app data on users’ self-reported feelings, while their phones’ GPS linked their location to a land-cover database; this novel study therefore benefits from measuring happiness in situ. Being in mountainous, woodland or ‘semi-natural grassland’ areas, as opposed to urban, was associated with approximately 2-points higher happiness, on a scale of 0–10, although no additional factors were controlled for [56].

While most of these studies were Good quality, interpretation is difficult due to lack of consensus in greenspace classification; in addition, four reports were based on data from the same survey. All but one were restricted to either urban or rural areas, so comparisons between these environments is not possible; however, larger effect sizes were observed in rural studies. Two of the Swedish studies concluded that green aspects were associated with lower GHQ scores for women, while 6 others highlighted that Serene (quiet, ‘natural’) and ‘natural’ rural greenspaces were associated with improved life satisfaction, SF-36 and lower GHQ scores, although none defined the term ‘natural’. Additionally, two studies reported an association between subjective perceptions of local greenspace and mental wellbeing. Evidence is therefore limited.

Visits to greenspace

Seventeen papers reported studies of visits, either comparing mental wellbeing scores before and after an intervention (n = 7), or testing cross-sectional associations with greenspace visiting patterns (n = 10).

Fair quality studies compared happiness and positive affect for those walking in ‘natural’ versus indoor environments [69], and walks in urban versus green areas [66]. The former reported a statistically significant difference in favour of greenspace walking, the latter did not. In a further Fair quality cross-sectional study, Marselle et al. reported a positive association between perceived restorativeness of the walking environment and positive affect and happiness [67].

Duvall and Kaplan observed 73 individuals on a wilderness expedition; attention and affect were improved post-expedition, persisting for 3–4 weeks [62]. Although effects were quite large (score changes of 0.270 to 0.340), participants were not blind to the intervention. A Fair quality uncontrolled study encouraged individuals to engage with ‘nature’ for 30 days by noticing/protecting wildlife, sharing experiences, or connecting with ‘nature’. Participants reported greater happiness following the programme [71]. Similarly, Molsher and Townsend noted mental wellbeing improvements following engagement with environmental volunteering projects [68], although their study displayed high risk of bias. Jakubec, however, reported no association between visiting greenspaces and Quality of Life Inventory score, in a Poor quality study [64].