Abstract

Objective

Few studies have comprehensively examined changes in smoking status and related factors after a disaster. We examined these factors among residents of an evacuation area in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Methods

The study participants included 58 755 men and women aged ≥20 years who participated in the Fukushima Health Management Survey in 2012 after the disaster. Smoking status was classified as either current smokers or current non-smokers before and after the disaster. The participants were divided into the following groups: (1) non-smokers both before and after the disaster, (2) non-smokers before and smokers after the disaster, (3) smokers before and non-smokers after the disaster and (4) smokers both before and after the disaster. The adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% CIs of changes in smoking status for demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial factors were tested using logistic regression analysis that was stratified by smoking status before the disaster.

Results

Among the 44 729 participants, who were non-smokers before the disaster, 634 (1.4%) began smoking after the disaster. Among the 14 025 smokers before the disaster, 1564 (11.1%) quit smoking after the disaster, and the proportion of smokers in the evacuation area consequently decreased from 21.2% to 19.6%. In the multivariable model, factors significantly associated with beginning smoking included being a male, being younger, having a lower education, staying in a rental house/apartment, house being damaged, having experienced a tsunami, change jobs and the presence of traumatic symptoms and non-specific psychological distress. On the contrary, factors associated with quitting smoking included being a female, being older, having a higher education and having a stable income.

Conclusion

The proportion of smokers slightly decreased among residents in the evacuation area. The changes in smoking statuses were associated with disaster-associated psychosocial factors, particularly changes in living conditions, having experienced a tsunami, change jobs and developing post-traumatic stress disorder.

Keywords: disaster, smoking cessation, socioeconomic status, population-based, psychological stress

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of this study lie in the sample size and procedures: a large-scale survey (n=58 755) was used for completing an inventory-based analysis of evacuees following the earthquake.

Smoking status before and after the earthquake was investigated using a self-administered questionnaire, and the number of cigarettes used among current smokers was not evaluated.

The present study had a low overall response rate (40.7%); therefore, the representativeness of the target population remains uncertain.

Introduction

The Great East Japan Earthquake that occurred on 11 March 2011 was one of the most disastrous events in the history of Japan. More than 160 000 people in the Fukushima Prefecture were forced to evacuate because of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident following the earthquake and the subsequent tsunami that struck the plant. Six years after the disaster, 77 283 have been evacuated as of March 2017.

The accident resulted in the disruption of normal lives of the people of Fukushima, including loss of life, relocations, maladjustment to new circumstances and induced stressful situations for the evacuees.1–3 A previous report stated that cumulative mental stress is partly associated with an increased risk of smoking because of increased impulsivity.4 Furthermore, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be associated with an increased risk of smoking.5 Moreover, most studies reported the proportion of smokers to have increased subsequent to disasters such as Hurricane Katrina,6–8 earthquakes9 10 and the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City.5 11 However, all previous studies comprised a limited sample size that ranged between 209 and 988 individuals and did not examine the change in smoking status in individuals and the associated factors. This warranted a comprehensive examination with a large sample size for determining the effect of disasters on smoking status.

Among the evacuees in Fukushima Prefecture, the prevalences of overweight, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, polycythaemia and atrial fibrillation increased 1 year after the nuclear power plant accident.12–15 Therefore, the evacuees are potentially at a greater risk of cardiovascular diseases if the proportion of current smoking increases because smoking is a major risk factor associated with cardiovascular diseases.

Therefore, we aimed to examine the smoking status after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident among more than 100 000 people in the evacuation area of the Fukushima Prefecture. The prevalences of a severe degree of traumatic symptoms, psychological distress and anxiety after the nuclear accident are high among the residents of the evacuation area.3 Hence, we also aimed to examine the associations of disaster-related and psychosocial factors with changes in smoking status.

Methods

Participants

The government designated evacuation instruction zones following the Great East Japan Earthquake that occurred on 11 March 2011. Between January and October 2012, the evacuees participated in the Fukushima Health Management Survey of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident that commenced in 2011. The ‘Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey’, which is part of the mentioned longitudinal study, assesses how the disaster and subsequent lifestyle of people affect the mental status of the evacuees over a long period of time.1 3

The target population of the survey included men and women at least 15 years of age who lived in the following evacuation zones specified by the government: Hirono Town, Naraha Town, Tomioka Town, Kawauchi Village, Okuma Town, Futaba Town, Namie Town, Katsurao Village, Minamisoma City, Tamura City, Kawamata Town, Iitate Village and a part of Date City. The questionnaire was mailed on 18 January 2012 to persons who had a certificate of residence in the evacuation area as of 11 March 2011. Of all the residents in the area during the disaster, 180 605 had been born prior to 1 April 1995 (ie, high school students or older). The participant response rate was 40.7% (n=73 569). We used the help of experts for guaranteeing precision when entering the data, and we double checked all entered data.

Since we sought to examine changes in smoking behaviour among the evacuees, we limited our data to men and women who were least 20 years old, which is the legal smoking age in Japan. Consequently, we used 58 754 participants for the analysis.

The purpose of this study was explained to all the respondents in a cover letter distributed with the questionnaire. The cover letter clearly indicated that the return of the questionnaires would be regarded as consent for study participation. The survey data collection was completed in 10 months (from January to October 2012).

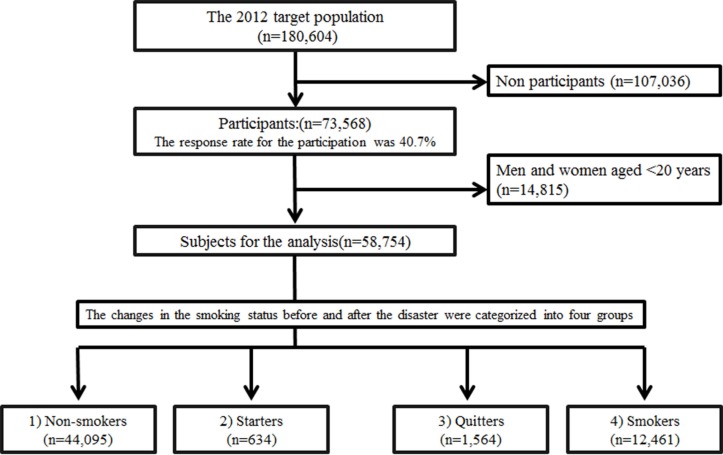

The questionnaire was used for determining smoking status which was classified as current smokers or current non-smokers just before the disaster; however, we did not distinguish participants who had never smoked or ex-smokers from current non-smokers. Smoking status 1 year after the disaster was classified as never smoked, ex-smokers and current smokers. Next, the changes in the smoking status before and after the disaster were categorised into four groups as shown in figure 1: (1) non-smokers both before and after the disaster (non-smokers), (2) non-smokers before and smokers after the disaster (starters), (3) smokers before and non-smokers after the disaster (quitters) and (4) smokers both before and after the disaster (smokers).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for determining smoking status.

Socioeconomic and disaster-related and psychosocial variables

Socioeconomic and disaster-related variables were assessed using the questionnaire responses. The assessed variables included living arrangements (own home, evacuation shelter, temporary housing, rental housing or apartment and relative’s home); whether they had ever lived in evacuation shelters (yes or no); education level (elementary school, junior high school and high school, vocational college, junior college, university (4 years) and graduate school); history of mental illness (yes or no); whether they became unemployed (yes or no); whether their income decreased (yes or no); whether their house was damaged (yes or no); whether they had experienced a tsunami before (yes or no); the presence of traumatic symptoms assessed by the Japanese version of PTSD Checklist-Stressor Specific Version (PCL-S) and the presence of non-specific psychological distress measured using the Japanese version of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6). These Japanese versions were reported to be validated.16–20

We considered a PCL-S score >44 as indicative of the presence of traumatic symptoms.16 17 21 We regarded a Kessler’s K6 score ≥13 as indicative of the presence of non-specific psychological distress.22–24 Age was used as a categorical variable and participants were classified into three age groups (20–49, 50–64 and ≥65 years). Education level was categorised as lower (high school or less) or higher (additional vocational college or junior college experience or higher).

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test was used for comparing the smoking status before and after the disaster. Disaster-related and socioeconomic variables were also compared among the categories of changes in smoking status before and after the disaster using the χ2 test.

We examined the association of demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial variables between those who began smoking compared with those who remained non-smokers after the disaster among all non-smokers before the disaster. We also examined the association of these variables between those who quit smoking compared with those who continued smoking among all smokers before the disaster.

Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CIs of the changes in smoking status for demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial variables were calculated using logistic regression analysis. In the multivariable-adjusted model, adjustments were made for age (years), sex and other associated factors estimated as statistically significant by the age-adjusted and sex-adjusted model. The potential associated factors were educational attainment, history of mental illness, living arrangement, house damage, having experienced a tsunami, change jobs, becoming unemployed, decreased income, the presence of traumatic symptoms and the presence of non-specific psychological distress. Because the proportion of smokers largely differed between men and women, we also conducted the multivariable analyses stratified by sex. P values were obtained using a two-tailed test, and p<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the software package SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the present study. Patient consent is not required.

Results

The proportion of current smokers among the total of 58 754 men and women significantly decreased from 23.9% to 22.3% after the disaster (p<0.001). The corresponding proportion among men decreased from 37.5% to 35.2% (p<0.001), whereas that among women decreased from 12.5% to 11.5% (p<0.001). Among the participants, 634 (1.1%) men and women began smoking after the disaster and 1564 (2.7%) men and women quit smoking after the disaster. The corresponding proportions of initiating and quitting smoking were 1.4% and 3.7% for men and 0.8% and 1.8% for women, respectively.

Table 1 shows the participants’ demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial variables in accordance with the categories of changes in smoking status, that is, non-smokers, starters, quitters and smokers. Compared with non-smokers, the beginner smokers displayed higher proportions of men, younger ages, rental house/apartment, shelter living, house damage, history of mental illness, having experienced a tsunami, becoming unemployed, decreased income, traumatic symptoms and non-specific psychological distress.

Table 1.

Demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial factors according to the categories of changes in smoking status among 58 754 men and women in the evacuation area

| Total | Non-smokers | Starters | Smokers | Quitters | P values | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | P values | n | % | n | % | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Sex | n=58 754 | n=44 095 | n=634 | n=12 461 | n=1564 | |||||||

| Men | 26 764 | 45.6 | 16 351 | 37.1 | 376 | 59.3 | <0.0001 | 9040 | 72.5 | 997 | 63.7 | <0.0001 |

| Women | 31 990 | 54.4 | 27 744 | 62.9 | 258 | 40.7 | 3421 | 27.5 | 567 | 36.3 | ||

| Age group | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| 20–49 years | 21 479 | 36.6 | 13 571 | 30.8 | 382 | 60.3 | <0.0001 | 6727 | 54.0 | 799 | 51.1 | <0.0001 |

| 50–64 years | 18 744 | 31.9 | 14 136 | 32.1 | 147 | 23.2 | 4012 | 32.2 | 449 | 28.7 | ||

| ≥65 years | 18 531 | 31.5 | 16 388 | 37.2 | 105 | 16.6 | 1722 | 13.8 | 316 | 20.2 | ||

| Educational attainment | n=57 076 | |||||||||||

| Primary or middle school | 13 383 | 23.4 | 10 680 | 25.0 | 102 | 16.8 | <0.0001 | 2329 | 19.1 | 272 | 17.7 | <0.0001 |

| High school | 28 331 | 49.6 | 20 190 | 47.2 | 331 | 54.5 | 6986 | 57.2 | 824 | 53.8 | ||

| Vocational college or junior college | 10 127 | 17.7 | 7849 | 18.4 | 116 | 19.1 | 1883 | 15.4 | 279 | 18.2 | ||

| University or graduate school | 5235 | 9.2 | 4014 | 9.4 | 58 | 9.6 | 1005 | 8.2 | 158 | 10.3 | ||

| History of mental illness | n=57 137 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 3149 | 5.5 | 2332 | 5.4 | 60 | 9.9 | <0.0001 | 662 | 5.5 | 95 | 6.2 | <0.0001 |

| Disaster-related factors | ||||||||||||

| Living arrangement | n=47 099 | |||||||||||

| Evacuation shelter | 522 | 1.1 | 401 | 1.1 | 8 | 1.6 | <0.0001 | 99 | 1.0 | 14 | 1.1 | <0.0001 |

| Temporary housing | 5343 | 11.3 | 3989 | 11.3 | 61 | 12.6 | 1164 | 11.6 | 129 | 10.3 | ||

| Rental house or apartment | 19 330 | 41.0 | 13 654 | 38.7 | 270 | 55.7 | 4780 | 47.4 | 626 | 49.8 | ||

| Relative’s home | 2127 | 4.5 | 1731 | 4.9 | 21 | 4.3 | 325 | 3.2 | 50 | 4.0 | ||

| Own home | 17 576 | 37.3 | 13 862 | 39.3 | 101 | 20.8 | 3252 | 32.3 | 361 | 28.7 | ||

| Others | 2201 | 4.7 | 1644 | 4.7 | 24 | 4.9 | 457 | 4.5 | 76 | 6.1 | ||

| Experienced living in evacuation shelters | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 15 865 | 27.0 | 11 887 | 27.0 | 198 | 31.2 | <0.0001 | 3365 | 27.0 | 415 | 26.5 | <0.0001 |

| House damage | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 8706 | 14.8 | 6528 | 14.8 | 134 | 21.1 | <0.0001 | 1812 | 14.5 | 232 | 14.8 | <0.0001 |

| Experience of disaster | ||||||||||||

| Having experienced a tsunami | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 11 807 | 20.1 | 8559 | 19.4 | 176 | 27.8 | <0.0001 | 2747 | 22.0 | 325 | 20.8 | <0.0001 |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||||||||

| Change jobs | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 2542 | 4.3 | 1599 | 3.6 | 56 | 8.8 | <0.0001 | 798 | 6.4 | 89 | 5.7 | <0.0001 |

| Becoming unemployed | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 12 255 | 20.9 | 8643 | 19.6 | 172 | 27.1 | <0.0001 | 3016 | 24.2 | 424 | 27.1 | <0.0001 |

| Decreased income | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 11 141 | 19.0 | 7548 | 17.1 | 145 | 22.9 | <0.0001 | 3117 | 25.0 | 331 | 21.2 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of traumatic symptoms (PCL-S) ≥44 | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 12 266 | 20.9 | 9247 | 21.0 | 210 | 33.1 | <0.0001 | 2515 | 20.2 | 294 | 18.8 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of non-specific mental illness (K6) ≥13 | n=58 754 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 8556 | 14.0 | 6337 | 14.4 | 157 | 24.8 | <0.0001 | 1853 | 14.9 | 209 | 13.4 | <0.0001 |

K6, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; PCL-S, Checklist-Stressor Specific Version.

Compared with smokers, the quitters displayed higher proportions of women, older age, higher education, history of mental illness, having experienced a tsunami and becoming unemployed and lower proportions of shelter living, decreased income, traumatic symptoms and non-specific psychological distress.

Table 2 indicates age-adjusted and sex-adjusted PRs and 95% CIs for the group that started smoking after the disaster according to demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial factors among the 44 729 smokers before the disaster. The corresponding age-adjusted and sex-adjusted PRs (95% CIs) were as follows: 2.91 (2.48 to 3.42) for men, 5.17 (4.15 to 6.43) for ages 20–49 years, 1.74 (1.35 to 2.23) for ages 50–64 years, 0.68 (0.57 to 0.82) for higher education (junior college and higher), 2.03 (1.54 to 2.67) for a history of mental illness, 1.46 (1.10 to 1.93) for living in temporary housing, 1.38 (1.16 to 1.64) for living in a rental house/apartment, 1.64 (1.35 to 1.99) for house damage, 1.57 (1.32 to 1.88) for having experienced a tsunami, 1.57 (1.18 to 2.08) for change jobs, 1.53 (1.28 to 1.83) for becoming unemployed, 1.18 (0.97 to 1.42) for decreased income, 2.38 (2.01 to 2.83) for the presence of traumatic symptoms and 2.26 (1.88 to 2.72) for the presence of non-specific mental illness.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted PRs and 95% CIs of starting smoking after the disaster according to demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial factors among 44 729 non-smokers before the disaster

| Model | Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted model | Multivariable-adjusted model* | ||||

| PR | (95% CI) | P values | PR | (95% CI) | P values | |

| n=44 729 | ||||||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Men (vs women)† | 2.91 | 2.48 to 3.42 | <0.0001 | 3.01 | 2.55 to 3.55 | <0.0001 |

| Age group‡ | ||||||

| Ages 20–49 years | 5.17 | 4.15 to 6.43 | <0.0001 | 5.55 | 4.40 to 7.00 | <0.0001 |

| Ages 50–64 years | 1.74 | 1.35 to 2.23 | <0.0001 | 1.81 | 1.40 to 2.33 | <0.0001 |

| Ages ≥65 years (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Educational attainment Vocational college, junior college or more (vs lower education) |

0.68 | 0.57 to 0.82 | <0.0001 | 0.69 | 0.57 to 0.83 | <0.0001 |

| History of mental illness | ||||||

| Yes (vs no) | 2.03 | 1.54 to 2.67 | <0.0001 | 1.45 | 1.09 to 1.93 | 0.010 |

| Disaster-related factors | ||||||

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Evacuation shelter | 1.53 | 0.75 to 3.13 | 0.246 | 1.36 | 0.66 to 2.78 | 0.409 |

| Temporary housing | 1.46 | 1.10 to 1.93 | 0.009 | 1.25 | 0.94 to 1.66 | 0.127 |

| Rental house or apartment | 1.38 | 1.16 to 1.64 | <0.001 | 1.33 | 1.12 to 1.58 | 0.001 |

| Relative’s home | 1.18 | 0.75 to 1.85 | 0.467 | 1.14 | 0.72 to 1.78 | 0.580 |

| Own home (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| House damage | ||||||

| Yes (vs no) |

1.64 | 1.35 to 1.99 | <0.0001 | 1.24 | 1.01 to 1.50 | 0.038 |

| Experience of disaster | ||||||

| Having experienced a tsunami yes (vs no) |

1.57 | 1.32 to 1.88 | <0.0001 | 1.29 | 1.07 to 1.55 | 0.008 |

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||

| Change jobs yes (vs no) |

1.57 | 1.18 to 2.08 | 0.002 | 1.41 | 1.05 to 1.89 | 0.023 |

| Becoming unemployed yes (vs no) |

1.53 | 1.28 to 1.83 | <0.0001 | 1.19 | 0.99 to 1.43 | 0.064 |

| Decreased income yes (vs no) |

1.18 | 0.97 to 1.42 | 0.092 | |||

| Presence of traumatic symptoms (PCL-S) ≥44 (vs ≤43) | 2.38 | 2.01 to 2.83 | <0.0001 | 1.70 | 1.37 to 2.11 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of non-specific mental illness (K6) ≥13 (vs ≤12) | 2.26 | 1.88 to 2.72 | <0.0001 | 1.38 | 1.09 to 1.75 | 0.007 |

*Adjusted for age and sex, educational attainment, history of mental illness, living arrangement, house damage, having experienced a tsunami, change jobs, becoming unemployed, decreased income, the presence of traumatic symptoms and the presence of non-specific mental illness except for the variable of interest.

†Age adjusted.

‡Sex adjusted.

K6, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; PCL-S, Checklist-Stressor Specific Version; PR, prevalence ratio.

The age-adjusted and sex-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted PRs and 95% CIs of participants who started smoking after the disaster according to demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial factors were calculated among the 44 729 non-smokers before the disaster. The corresponding multivariable-adjusted PRs (95% CIs) were as follows: 3.01 (2.55 to 3.55) for men, 5.55 (4.40 to 7.00) for ages 20–49 years, 1.81 (1.40 to 2.33) for ages 50–64 years, 0.69 (0.57 to 0.83) for higher education (junior college and higher), 1.45 (1.09 to 1.93) for a history of mental illness, 1.33 (1.12 to 1.58) for living in a rental house/apartment, 1.24 (1.01 to 1.50) for house damage, 1.29 (1.07 to 1.55) for having experienced a tsunami, 1.41 (1.05 to 1.89) for change jobs, 1.19 (0.99 to 1.43) for becoming unemployed, 1.70 (1.37 to 2.11) for the presence of traumatic symptoms and 1.38 (1.09 to 1.75) for the presence of non-specific mental illness. These associations did not substantially differ between men and women (online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2017-018943supp001.pdf (170.6KB, pdf)

Table 3 indicates the age-adjusted and sex-adjusted PRs and 95% CIs of quitting smoking after the disaster according to demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial factors among the 14 025 smokers before the disaster. The age-adjusted and sex-adjusted PRs (95% CIs) were 0.63 (0.56 to 0.71) for men, 0.58 (0.50 to 0.66) for 20–49 years, 0.59 (0.50 to 0.68) for 50–64 years, 1.32 (1.17 to 1.49) for higher education, 0.85 (0.75 to 0.97) for decreased income, 0.85 (0.74 to 0.97) for the presence of traumatic symptoms and 0.83 (0.71 to 0.97) for the presence of non-specific mental illness.

Table 3.

Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted PRs and 95% CIs of quitting smoking after the disaster according to demographic, disaster-related and psychosocial factors among the 14 025 smokers before the disaster

| Model | Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted model | Multivariable-adjusted model * | ||||

| PR | (95% CI) | P values | PR | (95% CI) | P values | |

| n=14025 | ||||||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Men (vs women)† | 0.63 | 0.56 to 0.71 | <0.0001 | 0.63 | 0.56 to 0.71 | <0.0001 |

| Age group‡ | ||||||

| Ages 20–49 years | 0.58 | 0.50 to 0.66 | <0.0001 | 0.53 | 0.46 to 0.62 | <0.0001 |

| Ages 50–64 years | 0.59 | 0.50 to 0.68 | <0.0001 | 0.57 | 0.48 to 0.66 | <0.0001 |

| Ages ≥65 years (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| Vocational college, junior college or more (vs lower education) | 1.32 | 1.17 to 1.49 | <0.0001 | 1.31 | 1.16 to 1.47 | <0.0001 |

| History of mental illness | ||||||

| Yes (vs no) | 1.09 | 0.87 to 1.37 | 0.436 | |||

| Disaster-related factors | ||||||

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Evacuation shelter | 1.16 | 0.66 to 2.04 | 0.613 | 1.20 | 0.68 to 2.12 | 0.537 |

| Temporary housing | 0.90 | 0.74 to 1.10 | 0.314 | 0.95 | 0.78 to 1.16 | 0.614 |

| Rental house or apartment | 1.09 | 0.97 to 1.22 | 0.146 | 1.12 | 1.00 to 1.25 | 0.061 |

| Relative’s home | 1.24 | 0.91 to 1.68 | 0.180 | 1.20 | 0.88 to 1.63 | 0.256 |

| Own home (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| House damage | ||||||

| Yes (vs no) |

1.03 | 0.89 to 1.19 | 0.705 | |||

| Experience of disaster | ||||||

| Having experienced a tsunami yes (vs no) |

0.97 | 0.85 to 1.11 | 0.652 | |||

| Psychosocial factors | ||||||

| Change jobs yes (vs no) |

0.94 | 0.75 to 1.18 | 0.594 | |||

| Becoming unemployed yes (vs no) |

1.09 | 0.96 to 1.23 | 0.171 | |||

| Decreased income yes (vs no) |

0.85 | 0.75 to 0.97 | 0.012 | 0.86 | 0.75 to 0.98 | 0.019 |

| Presence of traumatic symptoms (PCL-S) ≥44 (vs ≤43) | 0.85 | 0.74 to 0.97 | 0.016 | 0.89 | 0.76 to 1.05 | 0.160 |

| Presence of non-specific mental illness (K6) ≥13 (vs ≤12) | 0.83 | 0.71 to 0.97 | 0.022 | 0.89 | 0.74 to 1.07 | 0.209 |

*Adjusted for age and sex, educational attainment, living arrangement, decreased income, the presence of traumatic symptoms and the presence of non-specific mental illness except for the variable of interest.

†Age adjusted.

‡Sex adjusted.

K6, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; PCL-S, Checklist-Stressor Specific Version; PR, prevalence ratio.

The corresponding multivariable-adjusted PRs (95% CIs) were 0.63 (0.56 to 0.71) for men, 0.53 (0.46 to 0.62) for 20–49 years, 0.57 (0.48 to 0.66) for 50–64 years, 1.31 (1.16 to 1.47) for higher education, 0.89 (0.76 to 0.98) for decreased income, 0.89 (0.76 to 1.05) for the presence of traumatic symptoms and 0.89 (0.74 to 1.07) for the presence of non-specific mental illness. These associations did not substantially differ between men and women (online supplementary table 2).

Discussion

A primary finding of the present study is that the proportion of smokers slightly decreased among men and women aged ≥20 years in the evacuation area from 23.9% to 22.3% at 10–20 months after the March 2011 earthquake and the subsequent disastrous tsunami and nuclear power plant accident. The proportion of participants who quit smoking was higher than the proportion of those who started smoking, which were 3.7% and 1.4% among men and 1.8% and 0.8% among women, respectively.

On the contrary, studies have reported that the proportion of current smokers increases after a disaster: from 34.4% to 52.5% among men and women 1 year after Hurricane Katrina8 and from 22.6% to 23.4% among men and women aged ≥18 years 6 months after the terrorist attacks in Manhattan on 11 September 2001.9

In the present study, we found that factors associated with quitting smoking included being a female, older age, having a higher education and having a stable income. In contrast, factors associated with initiating smoking included being a male, younger age, having a lower education, staying in a rental house/apartment, experiencing damage to one’s house, having experienced a tsunami, change jobs, the presence of traumatic symptoms and the presence of non-specific psychological distress. The findings of this study regarding traumatic symptoms and non-specific psychological distress were consistent with findings from previous studies on Hurricane Katrina, the September 11 terrorist attacks and the Canterbury Great Earthquake; all these studies revealed that PTSD was a major factor for initiating smoking.6 7 9 Therefore, the management of PTSD may help prevent individuals from initiating smoking.

The National Health Nutrition Survey in Japan reported that the proportion of smokers in Japan before and after the disaster slightly increased from 19.5% (95% CI 20.0% to 20.9%) in 2010 to 20.7% (95% CI 18.6% to 20.3%) in 2012.25 One reason for the slight decrease in the proportion of current smokers in Fukushima after the disaster may be the decreased access to tobacco products. The earthquake damaged tobacco plantations, which ceased tobacco production and disrupted railway and road transportation networks in the areas that were damaged by the earthquake. Tobacco distribution stagnated after the disaster. According to a press release by Japan Tobacco, the total cigarette sales volume in April 2011 decreased by 81.8% compared with April 2010, and domestic cigarette sales decreased by 74.8%. Furthermore, the cigarette sales volume between April and September 2011 decreased by 41.2%, whereas the tobacco sales volume decreased by 20.4% compared with the same period in the previous year.26 These situations likely contributed to participants quitting smoking after the disaster in Fukushima.

Even though the proportion of current smokers slightly decreased among the evacuees after the disaster, the proportion of current smokers was still higher in the evacuation area than in other areas of Japan. In the present study, the proportion of current smokers was 22.3% (35.2% men and 11.5% women), whereas the corresponding proportion in the national sample was 20.1% (32.4% men and 9.7% women) in 2012.27

The strengths of this survey lie in its size and procedures because it involved a large-scale survey for completing an inventory-based analysis of evacuees following the earthquake.

This study has several limitations. First, we investigated smoking status before and after the earthquake using a self-reported questionnaire administered after the disaster that involved a cross-sectional study design; this may have led to recall bias. Second, we did not assess the number of cigarettes smoked among current smokers; thus, we could not examine dose–response relationships. Third, because the response rate in the present study was relatively low (41%), the representativeness of target populations was uncertain. Furthermore, if non-responders tended to be smokers or beginner smokers, the proportion of smokers after the disaster could be underestimated. Because smoking status changes more frequently in the teenage years, psychosocial factors may influence smoking status, particularly in teenagers. Unfortunately, the questions associated with smoking status were limited to men and women 20 years of age and older in the present study. Therefore, we did not evaluate an association between psychosocial factors and smoking status among the participants aged <20 years. Lastly, no data were present from non-disaster-exposed areas for comparison, except for national data on the prevalence of smoking.

In conclusion, the proportion of smokers slightly decreased among residents in the evacuation area. The changes in smoking status were associated with disaster-related psychosocial factors, particularly changes in living conditions, having experienced a tsunami, switching jobs and developing PTSD. A long-term follow-up study is warranted for examining the effects of disaster-related factors on smoking status among evacuees.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation for the support extended to them by the chairpersons, expert committee members, advisors and staff of the Fukushima Health Management Survey Group.

Footnotes

Contributors: HN, TO and HI contributed to the design of the present study. TO, SY, AO, MM, MH, NH, YS, HY and HT were responsible for data collection and overseeing the study procedures. The analysis was conducted by HN. The manuscript was written by HN. TO, SY, AO, MM, MH, NH, YS, HY, HT, MN, WZ, HI and KK made significant contributions to the critical interpretation of the results in terms of important practical content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This survey was conducted as part of Fukushima Prefecture’s postdisaster recovery plans and was supported by the ‘National Health Fund for Children and Adults Affected by the Nuclear Incident’.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This survey was approved by the ethics review committee of Fukushima Medical University (No. 1316).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Yasumura S, Hosoya M, Yamashita S, et al. Study protocol for the Fukushima Health Management Survey. J Epidemiol 2012;22:375–83. 10.2188/jea.JE20120105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Situation of the evacuation area and support for the victims in Fukushima. Cited 2017 May http://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/site/portal/list271.html (accessed 31 May 2017).

- 3. Yabe H, Suzuki Y, Mashiko H, et al. Psychological distress after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident: results of a mental health and lifestyle survey through the Fukushima Health Management Survey in FY2011 and FY2012. Fukushima J Med Sci 2014;60:57–67. 10.5387/fms.2014-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ansell EB, Gu P, Tuit K, et al. Effects of cumulative stress and impulsivity on smoking status. Hum Psychopharmacol 2012;27:200–8. 10.1002/hup.1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vlahov D, et al. Increased Use of Cigarettes, Alcohol, and Marijuana among Manhattan, New York, Residents after the September 11th Terrorist Attacks. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:988–96. 10.1093/aje/155.11.988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beaudoin CE. Hurricane Katrina: addictive behavior trends and predictors. Public Health Rep 2011;126:400–9. 10.1177/003335491112600314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flory K, Hankin BL, Kloos B, et al. Alcohol and cigarette use and misuse among Hurricane Katrina survivors: psychosocial risk and protective factors. Subst Use Misuse 2009;44:1711–24. 10.3109/10826080902962128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peters MN, Moscona JC, Katz MJ, et al. Natural disasters and myocardial infarction: the six years after Hurricane Katrina. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:472–7. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erskine N, Daley V, Stevenson S, et al. Smoking prevalence increases following Canterbury earthquakes. ScientificWorldJournal 2013;2013:1–4. 10.1155/2013/596957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naoi K. Local mental health activity after the Nligata-ken Chuetsu Earthquake: Findings of investigations performed three and a half months and thirteen months after the earthquake, and analysis about the risk factor of PTSD. Jap Bull Soc Psychiatry 2009;18:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vlahov D, Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, et al. Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan, New York, residents after the September 11th terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:988–96. 10.1093/aje/155.11.988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ohira T, Hosoya M, Yasumura S, et al. Effect of Evacuation on Body Weight After the Great East Japan Earthquake. Am J Prev Med 2016;50:553–60. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Satoh H, Ohira T, Nagai M, et al. Hypo-high-density Lipoprotein Cholesterolemia Caused by Evacuation after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident: Results from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Intern Med 2016;55:1967–76. 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sakai A, Ohira T, Hosoya M, et al. Life as an evacuee after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident is a cause of polycythemia: the Fukushima Health Management Survey. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1318 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Suzuki H, Ohira T, Takeishi Y, et al. Increased prevalence of atrial fibrillation after the Great East Japan Earthquake: Results from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Int J Cardiol 2015;198:102–5. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iwasa H, Suzuki Y, Shiga T, et al. Psychometric Evaluation of the Japanese Version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist in Community Dwellers Following the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Incident. Sage Open 2016;6:215824401665244 10.1177/2158244016652444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suzuki Y, Yabe H, Horikoshi N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Japanese posttraumatic stress measures after a complex disaster: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2017;9 10.1111/appy.12248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, et al. The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2008;17:152–8. 10.1002/mpr.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:184–9. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2010;19 Suppl 1:4–22. 10.1002/mpr.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther 1996;34:669–73. 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kessler RC, Galea S, Jones RT, Ronald CK, Sandro G, Russell TJ, et al. Mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:930–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, et al. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1427–34. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parslow RA, Jorm AF. Tobacco use after experiencing a major natural disaster: analysis of a longitudinal study of 2063 young adults. Addiction 2006;101:1044–50. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cancer Registry and Statistics. Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan, Pref_Smoking_Rate (2001-2013). http://ganjoho.jp/data/reg_stat/statistics/dl/Pref_Smoking_Rate (accessed 5 May 2017).

- 26. JAPAN TOBACCO INC(JTI). Japanese Domestic Cigarette Sales Results for April 2011 (Preliminary Report). 2011. cited 2015 June 11 http://www.jt.com/investors/media/press_releases/2011/pdf/20110512_12.pdf (accessed 5 Jun 2015).

- 27. Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Summarize the results of National Health Nutrition Survey. 2012. cited 1 Dec 2015 http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/04-Houdouhappyou-10904750-Kenkoukyoku-Gantaisakukenkouzoushinka/0000099296.pdf (accessed 5 Jun 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018943supp001.pdf (170.6KB, pdf)