Abstract

Yaws is a neglected tropical disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue. The disease primarily affects children under 15 years of age living in low socioeconomic conditions in tropical areas. As a result of a renewed focus on the disease owing to a recent eradication effort initiated by the World Health Organization, we have evaluated a typing method, adapted from and based on the enhanced Centers for Disease Control and Prevention typing method for T. pallidum subsp. pallidum, for possible use in epidemiological studies. Thirty DNA samples from yaws cases in Vanuatu and Ghana, 11 DNA samples extracted from laboratory strains, and 3 published genomic sequences were fully typed by PCR/RFLP analysis of the tpr E, G, and J genes and by determining the number of 60-bp repeats within the arp gene. Subtyping was performed by sequencing a homonucleotide “G” tandem repeat immediately upstream of the rpsA gene and an 84-bp region of tp0548. A total of 22 complete strain types were identified; two strain types in clinical samples from Vanuatu (5q11/ak and 5q12/ak), nine strain types in clinical samples from Ghana (3q12/ah, 4r12/ah, 4q10/j, 4q11/ah, 4q12/ah, 4q12/v, 4q13/ah, 6q10/aj, and 9q10/ai), and twelve strain types in laboratory strains and published genomes (2q11/ae, 3r12/ad, 4q11/ad, 4q12/ad, 4q12/ag, 4q12/v, 5r12/ad, 6r12/x, 6q11/af, 10q9/r, 10q12/r, and 12r12/w). The tpr RFLP patterns and arp repeat sizes were subsequently verified by sequencing analysis of the respective PCR amplicons. This study demonstrates that the typing method for subsp. pallidum can be applied to subsp. pertenue strains and should prove useful for molecular epidemiological studies on yaws.

Introduction

Yaws is an endemic treponematosis caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue (TPE)[1]. It shares greater than 99.5% sequence identity with T. pallidum subsp. pallidum (TPA) and T. pallidum subsp. endemicum (TEN), the etiologic agents of venereal syphilis and bejel, respectively[2–4]. The three subspecies are indistinguishable on the basis of morphology and serology; however, differences in epidemiological characteristics and clinical presentation are apparent[5]. Though syphilis is usually acquired through sexual contact, yaws is commonly spread through skin-to-skin contact and bejel through contaminated eating utensils. Yaws and bejel are common among children under 15 years old living in low socioeconomic conditions in tropical (yaws) or arid (bejel) climates. The characteristic feature of yaws during the primary infectious stage is a solitary papilloma or ulcer on the lower limb or foot. If untreated, secondary manifestations appear which include ulcers, papillomata and/or papules, squamous macules, and palmar and plantar lesions. This may rarely be accompanied by periostitis of the long bones (saber shin) and fingers (polydactylitis). Late, non-infectious manifestations, although rare these days, result in destructive lesions of skin and bone in up to 10–20% of untreated individuals.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF) conducted a yaws eradication campaign in the 1950s and 1960s; however, the disease soon re-emerged and has continued to spread in parts of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Western Pacific[1,5]. In 2012, the WHO launched a new eradication effort to eliminate yaws by the year 2020, as a result of the demonstration that single-dose azithromycin was as effective as parenteral benzathine benzylpenicillin for yaws treatment[6]. However, despite many studies to determine the prevalence of the disease in various regions and advances in diagnostic methods[7–11], only one recent study has been published describing strain typing for TPE strains[12]. The authors of that study sought to develop a three-gene multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme for TPE, and three main strain types were identified among 190+ lesion swabs. We hypothesized that additional markers may be useful for molecular distinction of TPE strains.

For this work we adapted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) typing method for TPA strains to characterize TPE in clinical samples collected prior to mass drug administration (MDA) campaigns in Vanuatu and Ghana. The CDC typing method combines analysis of the number of 60-bp repeats within the acidic repeat protein (arp) gene with restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) of the T. pallidum repeat (tpr) E, G, and J genes, despite in TPE the regions of tpr G and J used for RFLP are nearly identical and are thus expected to provide less discriminatory power than for TPA[13, 14]. The method used here also includes a subtyping component used for enhanced CDC typing which determines a sequence within the tp0548 locus for greater discrimination[15]. In addition, we evaluated a separate subtyping component which relies on sequence quantification of a variable number of guanine repeats in a guanine homonucleotide run immediately upstream of the rpsA (tp0279) locus. Finally, sequencing analysis was used to verify observed tpr RFLP patterns and arp repeat sizes and sequences.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and DNA isolation

These studies were previously approved by the Ministries of Health in Vanuatu and Ghana and were approved at CDC under project determination # 7103 and 7162.

Cutaneous swabs were collected from clinically-suspected yaws lesions and stored in AssayAssure (Sierra Molecular, Incline Village, NV) medium prior to DNA extraction using the ChargeSwitch gDNA Mini Tissue Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A total of 27 samples from suspected yaws patients on Tanna Island, Vanuatu[8] and 32 samples from the Abamkrom sub-municipality of Ghana that tested positive by PCR for TPE, as part of WHO yaws pilot studies, were included in the initial analysis. Following molecular testing of the DNA, full strain typing results for all targets examined were obtained only from 14 specimens from Vanuatu and 16 from Ghana, and thus only these data are presented here. Parental or guardian written and children’s verbal consent was given prior to examination of subjects. In addition, DNA from 11 TPE laboratory strains that were originally isolated from patients in Ghana (CDC 2575 and Ghana 051, isolated in 1980 and 1988, respectively)[16], Indonesia (K286, K319, K326, K344, K347, K348, K363, and K403, isolated in 1988)[17], and the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville, isolated in 1960)[16] were extracted from rabbit testicular extracts frozen in glycerol. DNA was extracted from the Nichols, Street 14, and JV-1 TPA strains grown in rabbit testes for use as controls[18]. 100 μL of each rabbit testicular sample was extracted using the ChargeSwitch gDNA Mini Tissue Kit and DNA was eluted in 100 μL elution buffer.

Sequences analyzed for in silico analysis

Previously published whole-genome sequencing data from three TPE strains were used for in silico analysis and strain typing. These include Samoa D (isolated in Western Samoa in 1953), Gauthier (isolated in Nigeria in 1963), and CDC2 (isolated in Ghana in 1980) available under accession numbers CP002374-CP002376[19].

PCR amplification of arp, tpr, tp0548, and rpsA genes for molecular typing

Strain typing was based on the CDC typing method for TPA[13]. The sequences of primers used for molecular analysis and amplicon sequencing are listed in Table 1. Briefly, a nested PCR was used for amplification of the tpr E (tp0313), tpr G (tp0317), and tpr J (tp0621) genes. Fifteen to 20 μL of DNA was used in a 50 μL reaction for the outer PCR with 2.6 units of Expand Taq polymerase (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), 1x PCR buffer, 200 nM dNTPs, and 0.2 μM each of primer B1 and A2. Reaction conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 2 min 30 sec, followed by a final extension at 68°C for 15 min. Two μL of the outer PCR product was used for the nested reaction using the following conditions using primers IP6 and IP7: 94°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 59°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 2 min, followed by a final extension at 68°C for 15 min.

Table 1. Primers used for molecular testing.

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Typing Primers | |

| ARP N1 | 5’–ATCTTTGCCGTCCCGTGTGC– 3’ |

| ARP N2 | 5’–CCGAGTGGGATGGCTGCTTC– 3’ |

| A2 | 5’–CTACCAGGAGAGGGTGACGC– 3’ |

| B1 | 5’–ACTGGCTCTGCCACACTTGA– 3’ |

| IP6 | 5’–CAGGTTTTGCCGTTAAGC– 3’ |

| IP7 | 5’–AATCAAGGGAGAATACCGTC– 3’ |

| TP0548 FP2 | 5’–GGTCCCTATGATATCGTGTTCG– 3’ |

| TP0548 RP2 | 5’–GTCATGGATCTGCGAGTGG– 3’ |

| 220I | 5’–GCGCCCCAGACCCGCTCT– 3’ |

| 220J | 5’–GAGCGATGATCACGGTCCCCAT– 3’ |

| Primers to Amplify Full-Length tpr Genes | |

| E1 | 5’–CAGGATTTTCCGGTTCATTG– 3’ |

| E2 | 5’–TCACGCGTTTAATGTTCTGC– 3’ |

| E3 | 5’–AACCGCTTTTGAGCGTGTTG– 3’ |

| E4 | 5’–CGGTGTTTGGCCGGTTATTC– 3’ |

| G9.89 | 5’–TTGCACTTCGCGTTGTTCTCC– 3’ |

| G10.3026 | 5’–TGTGGGTGTGCTTTGACACCA– 3’ |

| G6.232 | 5’–CTGCGGCCTGTCGCTCTTAG– 3’ |

| TPRG8 | 5’–GGACAGTGTGTGGATTCTTC– 3’ |

| J2 | 5’–CGGTGATTGCAGCTCGGAGT– 3’ |

| J3 | 5’–AAAGGACAGGGCCGTTGAGC– 3’ |

| TPRJ9Fl | 5’–GAAAAGAAGGGTGAGGGGGCTA– 3’ |

| TPRJ11 | 5’–CCTCGGCGGGTGTGGGTGTG– 3’ |

| Sequencing Primers | |

| 220I | 5’–GAGCGATGATCACGGTCCCCAT– 3’ |

| 495F | 5’–CGCTTCTCCTTCGCCCTC– 3’ |

| 120R | 5’–GCTTAAGGAATCCGGCAAAGT– 3’ |

| 458R | 5’–CGCCTCTACCTTCCCCTTGC– 3’ |

| 2124F | 5’–CTGTGCACAGCTGCGTGCTGG– 3’ |

RFLP analysis was performed on the nested tpr PCR product by digesting 6 μL of the DNA in a 10 μL volume with 1x reaction buffer, 1x bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2 units of the Mse I enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The reaction was carried out at 37°C for 2 h, followed by heat-denaturation of the enzyme at 65°C for 20 min. Samples were subsequently run on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The 60-bp acidic repeat region of the arp (tp0433) gene was amplified using primers ARP N1 and ARP N2[15, 20]. A 50 μL reaction mix contained 10 to 15 μL of DNA, 1.75 units of Expand Taq polymerase, 1x PCR buffer, 200 nM dNTPs, and 0.2 μM each of primers ARP N1 and ARP N2. PCR amplification was done using touchdown conditions as follows: 94°C for 2 min, then 13 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 74°C– 1°C/cycle for 45 sec, and 72°C for 1 min 30 sec, then 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 64°C for 45 sec, and 72°C for 1 min 30 sec, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplicons were subsequently run on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Repeat numbers were determined based on comparison with the Nichols TPA strain, which has 14 of the 60-bp repeats within arp[13].

A portion of the tp0548 locus (bp 131–215) was amplified as described previously with minor modifications[21]. A 50 μL reaction mix contained 5 μL of DNA, 2.5 units of AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Life Technologies), 1x PCR buffer, 1.5 μM MgCl2, 200 nM dNTPs, and 0.6 μM each of primers TP0548 FP2 and TP0548 RP2. Reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C for 2 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Samples were subsequently run on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. The PCR product was then purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen Sciences Inc., Germantown, MD, USA) and prepared for cycle sequencing.

A homonucleotide tandem repeat region immediately upstream of the coding region of the rpsA target locus was amplified as described previously[15]. A 50 μL reaction mix contained 10 to 15 μL of DNA, 2.5 units of AmpliTaq Gold polymerase, 1x PCR buffer, 1.5 μM MgCl2, 200 nM dNTPs, and 0.2 μM each of primers 220I and 220J. Reaction conditions were as follows: 94°C for 2 min, then 45 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec, 59°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Samples were subsequently run on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. The PCR product was then purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit and prepared for cycle sequencing.

PCR amplification to verify the typing method

To verify the RFLP patterns observed following restriction digestion, we used a nested PCR to amplify the full-length tpr genes separately for sequencing analysis[14]. Two μL of DNA was amplified in a 50 μL reaction with 2.5 units of TaKaRa polymerase (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), 1x PCR buffer, 200 nM dNTPs, and 0.2 μM of primers E1 and E2 for tpr E, G9.89 and G10.3026 for tpr G, or J2 and J3 for tpr J. Reaction conditions were as follows: 94°C for 1 min, then 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 3 min 30 sec, followed by a final extension at 68°C for 10 min. Two μL of outer PCR product were used for the nested reaction, which was carried out using the same conditions but with primers E3 and E4 for tpr E, G6.232 and TPRG8 for tpr G, and TPRJ9Fl and TPRJ11 for tpr J. Samples were run on an Agilent Bioanalyzer and subsequently purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit for amplicon sequencing.

To verify the number of 60-bp repeats as well as the sequence of each repeat within arp, we purified all arp amplicons using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit.

Cycle sequencing and sequencing analysis

The BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies) was used to sequence the purified arp and tpr E, G, and J gene amplicons. The oligonucleotides used for sequencing are listed in Table 1. Briefly, approximately 150 ng of DNA was mixed with 1 μL of BigDye, 1.5 μL of sequencing buffer, and 4 pmol of sequencing primer in a 10 μL final volume. Primers ARP N1 and ARP N2 were used to sequence arp while primers A2, B1, IP6, IP7, 495F, 120R, 458R, and 2124F were used to sequence each of the tpr genes. Cycle sequencing was performed on a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with an initial denaturation of 96°C for 1 min followed by 25 cycles of 96°C for 10 sec, 50°C for 5 sec, and 60°C for 4 min. The tp0548 and rpsA amplicons were similarly sequenced with the following modifications: 5 ng of DNA was used with 2 μL of BigDye and 3.2 pmol of primer TP0548 FP2 or TP0548 RP2 for tp0548 or primer 220E or 220J for rpsA and with an initial denaturation of 96°C for 10 min. Products were purified using the BigDye XTerminator Purification Kit (Applied Biosystems) and run on an Applied Biosystems 3130xl Genetic Analyzer. All assemblies of sequenced amplicons, analyses of amplicons and published genomic sequences, and in silico digestion of tpr were performed using Geneious software (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand).

Statistical methods

Associations between categorical variables were determined by using the chi-squared test. Results for which P<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Tpr RFLP patterns

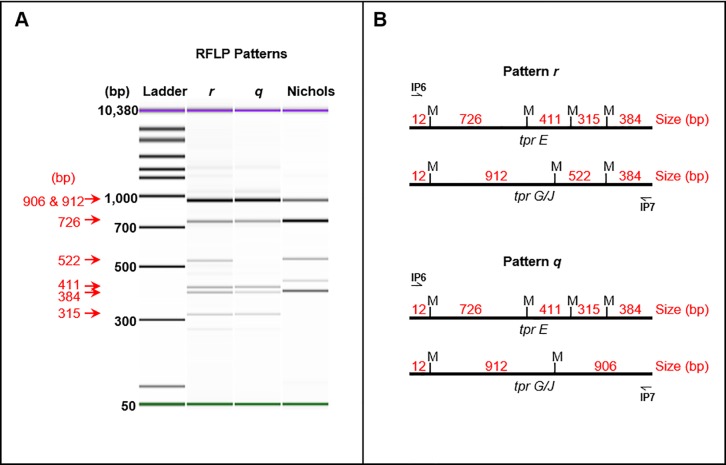

Initially, 73 TPE strains were analyzed including 27 clinical specimens from Vanuatu, 32 clinical specimens from Ghana, 11 laboratory strains, and 3 published TPE genomes. Due to incomplete strain typing data at a single or multiple targets, a total of 44 TPE strains were fully typed including 14 clinical specimens from Vanuatu and 16 clinical specimens from Ghana; and 14 laboratory strains including 3 strains with whole genome sequences were strain typed. Following nested PCR amplification of the tpr E, G, and J genes and digestion with the enzyme Mse I two patterns, the previously identified pattern q[22] and new pattern r, were observed (Fig 1A). Six bands (approximately 320, 400, 420, 530, 750, and 950 bp in size) were observed in pattern r while five bands (approximately 320, 400, 420, 750, and 950 bp in size) were observed in pattern q (Fig 1B). Of these 44 strains, 100% (14/14) of the Vanuatu specimens and 94% (15/16) of the Ghana specimens were considered pattern q while 6% (1/16) of the Ghana specimens exhibited pattern r. Greater diversity of the two patterns was observed among the laboratory strains with 57% (8/14) considered pattern q and 43% (6/14) pattern r. A significant association was observed between RFLP pattern and geographic region (p = 0.0245), though a larger dataset may be necessary to understand if overrepresentation of the historic strains accounts for this.

Fig 1. RFLP patterns of T. pallidum subsp. pertenue.

(A) The tpr E, G, and J genes were amplified in a nested PCR to produce a mixed amplicon approximately 1830–1848 bp in length. Following PCR, amplicons were digested with the enzyme Mse I and analyzed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Two RFLP patterns (q and r) were observed among the clinical specimens and laboratory strains analyzed, including those for strains only partially typed (data not shown). The sizes of each fragment were confirmed through sequencing and are indicated in red. The Nichols TPA strain was used as a control for RFLP. The violet and green bands visible in each lane depict the Bioanalyzer kit’s internal control upper and lower bands, respectively. (B) Each of the tpr E, G, and J genes was amplified directly from the genome and sequenced. Regions of the products between the IP6 and IP7 primer annealing sequences were analyzed for Mse I restriction sites for both patterns. Approximate positions of each site (indicated as “M”) are shown. Sizes between each restriction site are listed in red.

To verify that the observed tpr RFLP patterns q and r are genetically relevant for molecular typing purposes, we sequenced the relevant regions of tpr E, G, and J. Each gene was amplified using gene-specific primers from several samples displaying either RFLP pattern. Following sequencing analysis of the regions between IP6/IP7 annealing sites we confirmed the presence and positions of Mse I restriction sites in each. In all tpr E samples that were examined, four restriction sites at positions 13, 739, 1150, and 1465 bp within the region were identified resulting in five fragments (Fig 1B). Specimens with RFLP pattern r displayed genetic variation between the tpr G and J genes. In some strains with pattern r the sequences of tpr G and J were identical with three restriction sites at positions 13, 922, and 1447 bp which resulted in four fragments approximately 12, 384, 522, and 912 bp in length in both genes. In other strains displaying pattern r the additional restriction site at position 1447 bp was not present in tpr J, though the resulting pattern was still visually indistinguishable from the other RFLP pattern r strains as the site was present within tpr G. This Mse I site at position 1447 bp was absent in both tpr G and J amplicons from RFLP pattern q specimens. Following sequencing analysis we performed in silico digestion using the enzyme Mse I on the relevant regions of the three genes from each sample. The digestion confirmed the sizes of each fragment produced in the tpr amplicon mixture as observed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Fig 1A).

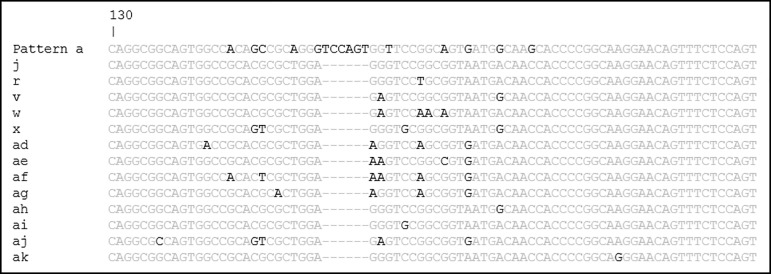

Analysis of 60-bp repeats within arp

Eight different arp patterns (containing 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, or 12 60-bp repeats, respectively) were observed among the 44 strains fully typed, including the published genomes computationally analyzed (not shown) (Fig 2A). All 14 clinical specimens from Vanuatu had 5 arp repeats, including those only partially typed (data not shown), while the majority of clinical specimens from Ghana (13/16) had 4 repeats and a single strain each had 3, 6, and 9 repeats, respectively (Fig 2B). Of the Ghana strains partially subtyped, 4 60-bp repeats was also the only observable arp pattern (data not shown). Seven repeat patterns (containing 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, or 12 60-bp repeats, respectively) were observed among the 14 laboratory strains and published genomes. Overall, arp repeat size was associated with geographic region (p<0.0001), with some arp patterns primarily localized in certain countries (e.g. Vanuatu).

Fig 2. Analysis of the arp 60-bp repeat region.

(A) A portion of the arp gene was amplified through PCR and run on an Agilent Bioanalyzer for each sample. Seven patterns containing 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 10 repeats were identified among the samples tested in the lab, and an additional pattern (12 repeats) was seen following in silico analysis of one of the published genomes (not shown). The Nichols TPA strain, which contains 14 repeats, was used as a reference. The violet and green bands visible in each lane depict the Bioanalyzer kit’s internal control upper and lower bands, respectively. (B) Distribution of repeat sizes in clinical specimens from Vanuatu, Ghana clinical specimens, and among laboratory strains.

In order to verify the number of 60-bp repeats within arp we sequenced the purified amplicons. Sequencing subsequently confirmed the number of repeats observed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer in each of the 44 samples fully strain typed. Additionally, for all samples the sequence within each 60-bp repeat was identical as expected based on previous studies by Harper et al.[23].

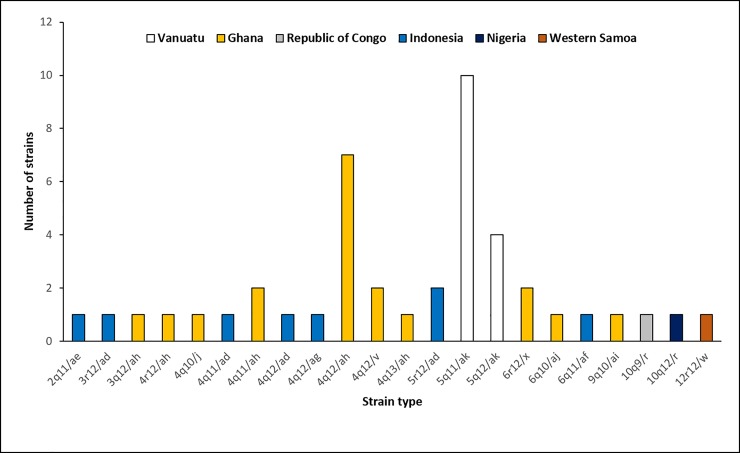

Molecular subtyping by pattern determination within tp0548

A total of 13 subtyping patterns were obtained following sequencing of the tp0548 locus or in silico analysis of published data (Fig 3), one of which matched a known TPA pattern and four of which were identified previously [12, 14]. Accordingly, tp0548 subtyping pattern names for TPE strains were assigned according to the next available letter to be consistent with previous TPE designations. There was a significant association between tp0548 subtype and geographic region (p<0.0001) with some subtypes only located in specimens from a single country. For example, a single subtype (ak) was observed in the Vanuatu clinical specimens, including among those only partially strain typed (data not shown). Five subtypes (j, v, ah, ai, and aj) were observed in the Ghana clinical specimens, including a single partially strain typed strain (which had pattern aj, not shown). Among them, subtype ah was the most common, being observed in 75% (12/16) of specimens fully strain typed. Eight subtypes (r, v, w, x, ad, ae, af, and ag) were observed in the laboratory strains with pattern ad (5/14) being the most frequent. Subtype v was observed in a single Ghana clinical strain, matching the pattern computationally determined for the TPE strain CDC2, which was isolated in Ghana in 1980.

Fig 3. Alignment of the sequences using the variable region within tp0548.

Amplicons containing a region of the tp0548 locus were sequenced and analyzed for their genetic composition. The alignment compares the subtypes identified in this study to the Nichols TPA strain (pattern a). Thirteen subtypes, designated following nomenclature used for TPA strains and previously applied to TPE strains[12], were identified among the clinical specimens and laboratory strains, including those only partially strain typed.

Molecular subtyping by tandem repeat determination within rpsA

Amplicons containing a portion of the rpsA locus were sequenced to determine the composition of a guanine homonucleotide tandem repeat upstream of the rpsA coding sequence. Five subtyping patterns were observed, containing 9, 10, 11, 12 or 13 repeats. Two subtypes were found in the Vanuatu samples with 71% (10/14) of the samples fully strain typed containing 11 repeats and 29% (4/14) containing 12 repeats, respectively. No additional subtypes were observed in the samples not fully strain typed, though a larger number of those (8/13) contained 12 repeats than 11 repeats (3/13) (data not shown). While 63% (10/16) of the Ghana specimens fully strain typed contained 12 tandem repeats, samples containing 10 (3/16 strains), 11 (2/16 strains), and 13 (1/16 strains) repeats were also found. Similar to the Vanuatu specimens, 12 repeats were more often seen among the Ghana samples not fully strain typed (5/16) than the other subtype identified (10 repeats, in a single strain) (data not shown). The most common rpsA subtyping pattern among the laboratory strains was 12 repeats as observed in 71% (10/14) of the samples. Other subtypes among the laboratory strains include 11 and 9 tandem repeats. Overall, there was a significant association between rpsA subtype and geographic region (p<0.0001).

We also sought to examine the stability and reproducibility of this locus. While a previous study noted inter- and intrastrain variability in homopolymeric tracts within T. pallidum[24], we observed stable sequences within the rpsA locus. Analysis of rpsA amplicons from the Street 14 TPA strain taken at three random rabbit passages over a 15-month period gave identical results (data not shown). This was consistent in five separate experiments using DNA from the Nichols, Street 14, and JV-1 TPA strains (i.e. consistently yielding 10, 9 and 9 repeats, respectively). Also, mixing three consecutive repeat sizes (9, 10, and 11) in different ratios followed by direct sequencing resulted in the observed repeat size being the same as the major repeat in the sample (data not shown).

Strain types of TPE strains

Full strain typing results are shown in Table 2. Similar to the nomenclature used for enhanced CDC typing of TPA strains[21], strain types of TPE strains have been expressed as the number of 60-bp repeats (e.g. “5” in 5q12/ak), the tpr E, G, and J RFLP pattern (e.g. “q” in 5q12/ak), and the tp0548 pattern (e.g. “ak” in 5q12/ak).When the number of tandem repeats within rpsA are included the designated strain type reflects the numerical count (e.g. “12” in 5q12/ak).

Table 2. Complete molecular strain types of T. pallidum subsp. pertenue.

| Number of specimens (% of region) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical strains | Laboratory strains and in silico analysis of published sequences | ||||||

| Strain type | Vanuatu n = 14 |

Ghana n = 16 |

Republic of Congo n = 1 |

Indonesia n = 8 |

Ghana n = 3 |

Nigeria n = 1 |

Western Samoa n = 1 |

| 2q11/ae | - | - | - | 1 (12%) | - | - | - |

| 3r12/ad | - | - | - | 1 (12%) | - | - | - |

| 3q12/ah | - | 1 (6%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4r12/ah | - | 1 (6%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4q10/j | - | 1 (6%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4q11/ad | - | - | - | 1 (12%) | - | - | - |

| 4q11/ah | - | 2 (13%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4q12/ad | - | - | - | 1 (12%) | - | - | - |

| 4q12/ag | - | - | - | 1 (12%) | - | - | - |

| 4q12/ah | - | 7 (44%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4q12/v | - | 1 (6%) | - | - | 1 (33%) | - | - |

| 4q13/ah | - | 1 (6%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5r12/ad | - | - | - | 2 (25%) | - | - | - |

| 5q11/ak | 10 (71%) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5q12/ak | 4 (29%) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6r12/x | - | - | - | - | 2 (67%) | - | - |

| 6q10/aj | - | 1 (6%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6q11/af | - | - | - | 1 (12%) | - | - | - |

| 9q10/ai | - | 1 (6%) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10q9/r | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | - | - |

| 10q12/r | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - |

| 12r12/w | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) |

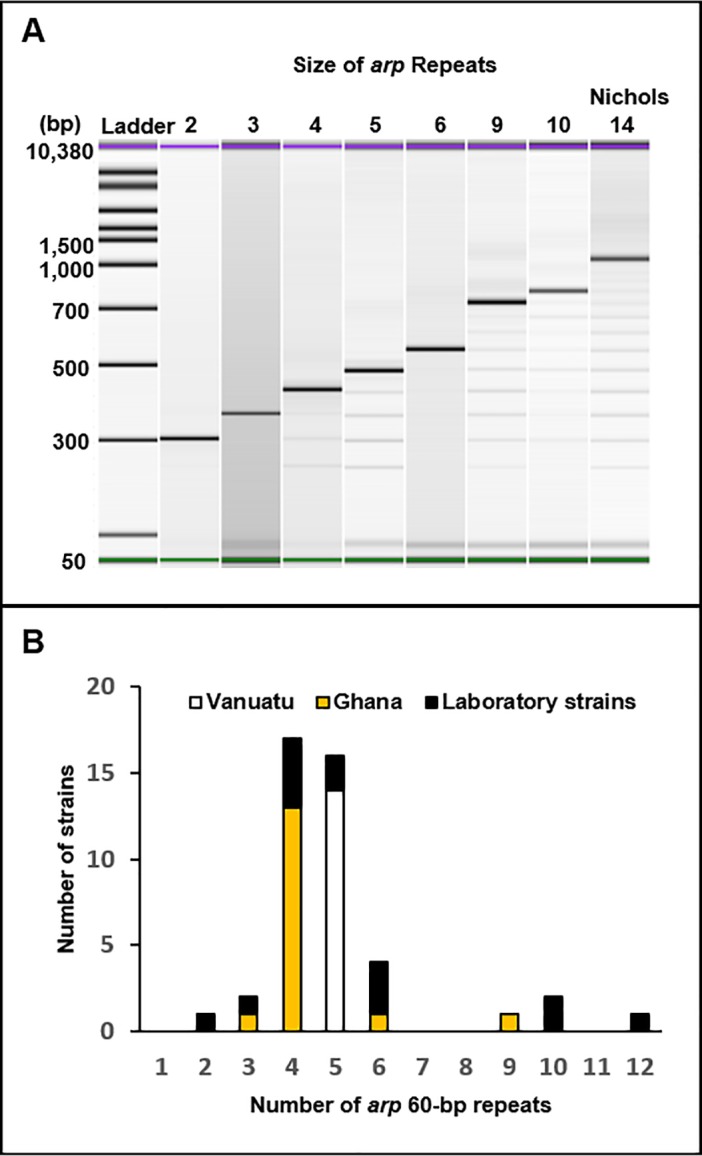

Using only the original target loci in the CDC molecular typing method consisting of the tpr RFLP and arp 60-bp repeat analysis, a total of 12 different types were identified among all samples fully strain typed. A total of 18 strain types were observed following the addition of the rpsA data to tpr and arp, and 17 strain types were observed instead with the addition of tp0548 data to tpr and arp. A total of 22 strain types were identified when all 4-target loci were combined for typing (Table 2). The distribution of strain types among the different countries reflects the diversity of TPE strains in yaws-endemic regions (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Distribution of TPE strains.

Twenty-two strain TPE strain types were identified among the 44 specimens and genomic sequences analyzed. The overall distribution between each of the geographic locations is shown.

Associations between RFLP pattern and tp0548 subtype (p = 0.011) as well as arp repeat size with both tp0548 subtype (p<0.0001) and rpsA subtype (p = 0.0075) were observed, while there was no association between RFLP pattern and rpsA pattern. Additionally an association between tp0548 and rpsA subtypes (p = 0.0042) was observed, which indicates complementarity of these subtyping components when applied to TPE strains. Finally, there is an association between strain type and geographic region (p<0.0001), which appears evident from the presence of certain strain types in singular locations (e.g. 5b11/ak, which was found in high numbers only among the Vanuatu specimens).

Discussion

The original TPA CDC typing method, as well as its variations[15, 21], has been successfully used in characterizing syphilis cases worldwide since the introduction of TPA typing two decades ago[13, 15, 20, 25–28]. Strain typing has subsequently proved a valuable tool in molecular epidemiologic studies during surveillance in specific regions, the emergence of macrolide resistance and during specific outbreaks[29–35]. While yaws is perhaps not as well-known as syphilis, it has become the focus of renewed interest as a result of the disease eradication campaign initiated by the WHO in 2012[1]. Recently, Godornes and colleagues applied a novel MLST scheme for TPE strains to 194 lesion samples from Papua New Guinea, and they found three predominant sequence types[12]. While their work presents a promising new method for molecular characterization of yaws strains, to our knowledge the scheme has not been applied to syphilis strains; therefore, it is more challenging for strain typing comparisons of yaws and syphilis. The goal of our present study was to evaluate the use of the CDC genotyping method for syphilis in molecular epidemiological studies of yaws.

In order to determine whether the typing system could be applied to TPE strains, we initially tested 73 specimens from PCR-confirmed yaws cases in Vanuatu and Ghana as well as laboratory strains originally isolated from Indonesia and parts of Africa. While a direct comparison of the typing method described here to the MLST scheme recently published[12] would provide a better picture of the utility of either approach, due to low specimen volumes or lack of DNA we were unable to address this in the present study. Four target loci were used for molecular typing, including the 60-bp repeat region within arp, tpr for RFLP analysis, a variable region within tp0548, and a homonucleotide tandem repeat within rpsA. The CDC typing method was fully applied to 44 TPE strains, including 41 tested in the lab and 3 computationally analyzed; however, several differences compared to TPA strains were noted.

First, the observed RFLP patterns differ from those found in TPA strains as genetic variations between the two subspecies exist at the tpr loci. In addition, because tpr G and J are identical in several TPE strains there is decreased discrimination using this genotyping component compared with application to TPA strains, as evidenced by the sheer number of RFLP patterns among syphilis strains while only two among the 44 yaws strains were revealed in this study. Next, sequencing analysis of arp amplicons revealed only the type II repeat motif was present among the TPE strains analyzed though in syphilitic strains there is more variability, as reported in the literature[18, 23]. Though the researchers in these studies concluded that diversity in arp correlated with transmission mode, further analysis of the significance of a singular motif in arp is beyond the scope of this paper and was not explored in the work presented here. Inclusion of the tp0548 and rpsA subtyping methods allowed for greater discrimination of the yaws strains than the original CDC typing targets alone, similar to previous findings in syphilis[15, 21]. These findings support the inclusion of both subtyping targets for strain typing of TPE strains. Associations between the individual components of the typing scheme (including RFLP pattern with tp0548 subtype, arp repeat size with rpsA and tp0548, and between the subtyping components) should be explored to understand if there is a genetic preference or if these findings simply reflect the genetic diversity of the strains examined here.

Of the 44 fully typed TPE strains, 22 strain types were identified using the 4-component system (Table 2). No strain type was observed in more than one country (Fig 4). We observed only two strain types among the Vanuatu specimens, which probably reflects infrequent introduction of new strains from the outside world into the rural communities of this remote island nation, while the genetic diversity observed in Ghana possibly reflects higher endemicity or transmission between communities. While the low sample size could have influenced these findings, we did observe a significant association between strain type and geographic region (p<0.0001) which appears to support these observations. Furthermore, each of the targets used for strain typing was associated with geographic region (p<0.05), highlighting their utility for distinction of TPE strains.

It should be noted that more researchers are moving away from complex typing schemes due to difficulties with amplification of long tracts of repetitive sequences and issues with reproducibility of RFLP patterns. Interestingly, in this study we initially found a “third” RFLP pattern that could not be confirmed upon sequencing analysis of the tpr genes examined. Inclusion of the roughly 80-nt region of tp0548 for enhanced CDC typing greatly improves the discriminatory ability of strain typing compared with the original typing scheme, and researchers in the Czech Republic have identified further genetic variations in the locus for molecular distinction[21, 29]. However, phylogenetic analyses of these longer regions of tp0548 indicate it is not useful for distinction of the TPA and TPE/TEN lineages[4]. Difficulties such as these have prompted exploration of sequence-based approaches and additional targets for yaws and syphilis studies. Though several studies have examined the utility of sequencing various targets for strain typing with promising findings[12, 36–38], the enhanced CDC typing remains a useful and highly discriminatory tool for molecular characterization of syphilis strains.

Overall, our data demonstrate that the CDC typing method for syphilis can be effectively applied to yaws strains. Application of the procedures described here to characterize TPE-specific DNA from confirmed yaws cases could prove useful in genetic characterization of the disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their sincere thanks to Dr. Gerda Noordhoek for providing the laboratory TPE strains. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other funding agencies.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Mitja O, Asiedu K, Mabey D. Yaws. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):763–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62130-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smajs D, Norris SJ, Weinstock GM. Genetic diversity in Treponema pallidum: implications for pathogenesis, evolution and molecular diagnostics of syphilis and yaws. Infection, genetics and evolution: journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2012;12(2):191–202. 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.12.001 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3786143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staudova B, Strouhal M, Zobanikova M, Cejkova D, Fulton LL, Chen L, et al. Whole genome sequence of the Treponema pallidum subsp. endemicum strain Bosnia A: the genome is related to yaws treponemes but contains few loci similar to syphilis treponemes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(11):e3261 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003261 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4222731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora N, Schuenemann VJ, Jager G, Peltzer A, Seitz A, Herbig A, et al. Origin of modern syphilis and emergence of a pandemic Treponema pallidum cluster. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16245 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.245 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asiedu K, Amouzou B, Dhariwal A, Karam M, Lobo D, Patnaik S, et al. Yaws eradication: past efforts and future perspectives. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86(7):499–A. 10.2471/BLT.08.055608 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2647478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitja O, Hays R, Ipai A, Penias M, Paru R, Fagaho D, et al. Single-dose azithromycin versus benzathine benzylpenicillin for treatment of yaws in children in Papua New Guinea: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9813):342–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61624-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitja O, Smajs D, Bassat Q. Advances in the diagnosis of endemic treponematoses: yaws, bejel, and pinta. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013;7(10):e2283 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002283 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3812090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi KH, Danavall D, Taleo F, Pillay A, Ye T, Nachamkin E, et al. Molecular differentiation of Treponema pallidum subspecies in skin ulceration clinically suspected as yaws in Vanuatu using real-time multiplex PCR and serological methods. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(1):134–8. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0459 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4347369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks M, Sokana O, Nachamkin E, Puiahi E, Kilua G, Pillay A, et al. Prevalence of Active and Latent Yaws in the Solomon Islands 18 Months after Azithromycin Mass Drug Administration for Trachoma. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2016;10(8):e0004927 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004927 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4994934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks M, Katz S, Chi KH, Vahi V, Sun Y, Mabey DC, et al. Failure of PCR to Detect Treponema pallidum ssp. pertenue DNA in Blood in Latent Yaws. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2015;9(6):e0003905 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003905 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4488379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghinai R, El-Duah P, Chi KH, Pillay A, Solomon AW, Bailey RL, et al. A cross-sectional study of 'yaws' in districts of Ghana which have previously undertaken azithromycin mass drug administration for trachoma control. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2015;9(1):e0003496 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003496 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4310597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godornes C, Giacani L, Barry AE, Mitja O, Lukehart SA. Development of a Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) scheme for Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue: Application to yaws in Lihir Island, Papua New Guinea. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(12):e0006113 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006113 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5760108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillay A, Liu H, Chen CY, Holloway B, Sturm AW, Steiner B, et al. Molecular subtyping of Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1998;25(8):408–14. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikalova L, Strouhal M, Cejkova D, Zobanikova M, Pospisilova P, Norris SJ, et al. Genome analysis of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum and subsp. pertenue strains: most of the genetic differences are localized in six regions. PloS one. 2010;5(12):e15713 10.1371/journal.pone.0015713 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3012094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz KA, Pillay A, Ahrens K, Kohn RP, Hermanstyne K, Bernstein KT, et al. Molecular epidemiology of syphilis—San Francisco, 2004–2007. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2010;37(10):660–3. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e1a77a . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noordhoek GT, Cockayne A, Schouls LM, Meloen RH, Stolz E, van Embden JD. A new attempt to distinguish serologically the subspecies of Treponema pallidum causing syphilis and yaws. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1990;28(7):1600–7. ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC267996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noordhoek GT, Engelkens HJ, Judanarso J, van der Stek J, Aelbers GN, van der Sluis JJ, et al. Yaws in West Sumatra, Indonesia: clinical manifestations, serological findings and characterisation of new Treponema isolates by DNA probes. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases: official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 1991;10(1):12–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H, Rodes B, George R, Steiner B. Molecular characterization and analysis of a gene encoding the acidic repeat protein (Arp) of Treponema pallidum. Journal of medical microbiology. 2007;56(Pt 6):715–21. 10.1099/jmm.0.46943-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cejkova D, Zobanikova M, Chen L, Pospisilova P, Strouhal M, Qin X, et al. Whole genome sequences of three Treponema pallidum ssp. pertenue strains: yaws and syphilis treponemes differ in less than 0.2% of the genome sequence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(1):e1471 Epub 2012/02/01. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001471 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3265458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruz AR, Pillay A, Zuluaga AV, Ramirez LG, Duque JE, Aristizabal GE, et al. Secondary syphilis in cali, Colombia: new concepts in disease pathogenesis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(5):e690 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000690 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2872645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marra C, Sahi S, Tantalo L, Godornes C, Reid T, Behets F, et al. Enhanced molecular typing of treponema pallidum: geographical distribution of strain types and association with neurosyphilis. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;202(9):1380–8. 10.1086/656533 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3114648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grange PA, Allix-Beguec C, Chanal J, Benhaddou N, Gerhardt P, Morini JP, et al. Molecular subtyping of Treponema pallidum in Paris, France. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2013;40(8):641–4. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harper KN, Liu H, Ocampo PS, Steiner BM, Martin A, Levert K, et al. The sequence of the acidic repeat protein (arp) gene differentiates venereal from nonvenereal Treponema pallidum subspecies, and the gene has evolved under strong positive selection in the subspecies that causes syphilis. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology. 2008;53(3):322–32. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00427.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinto M, Borges V, Antelo M, Pinheiro M, Nunes A, Azevedo J, et al. Genome-scale analysis of the non-cultivable Treponema pallidum reveals extensive within-patient genetic variation. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16190 Epub 2016/10/18. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.190 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pope V, Fox K, Liu H, Marfin AA, Leone P, Sena AC, et al. Molecular subtyping of Treponema pallidum from North and South Carolina. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005;43(8):3743–6. 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3743-3746.2005 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1233889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai T, Li K, Lu H, Gu X, Wang Q, Zhou P. Molecular typing of Treponema pallidum: a 5-year surveillance in Shanghai, China. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012;50(11):3674–7. 10.1128/JCM.01195-12 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3486273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azzato F, Ryan N, Fyfe J, Leslie DE. Molecular subtyping of Treponema pallidum during a local syphilis epidemic in men who have sex with men in Melbourne, Australia. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012;50(6):1895–9. 10.1128/JCM.00083-12 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3372124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Florindo C, Reigado V, Gomes JP, Azevedo J, Santo I, Borrego MJ. Molecular typing of treponema pallidum clinical strains from Lisbon, Portugal. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2008;46(11):3802–3. 10.1128/JCM.00128-08 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2576594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grillova L, Petrosova H, Mikalova L, Strnadel R, Dastychova E, Kuklova I, et al. Molecular typing of Treponema pallidum in the Czech Republic during 2011 to 2013: increased prevalence of identified genotypes and of isolates with macrolide resistance. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2014;52(10):3693–700. 10.1128/JCM.01292-14 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4187743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pillay A, Liu H, Ebrahim S, Chen CY, Lai W, Fehler G, et al. Molecular typing of Treponema pallidum in South Africa: cross-sectional studies. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2002;40(1):256–8. 10.1128/JCM.40.1.256-258.2002 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC120137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin IE, Tsang RS, Sutherland K, Anderson B, Read R, Roy C, et al. Molecular typing of Treponema pallidum strains in western Canada: predominance of 14d subtypes. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2010;37(9):544–8. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181d73ce1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng RR, Yin YP, Wei WH, Wang HC, Zhu BY, Liu QZ, et al. Molecular typing of Treponema pallidum causing early syphilis in China: a cross-sectional study. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2012;39(1):42–5. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318232697d . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H, Chang SY, Lee NY, Huang WC, Wu BR, Yang CJ, et al. Evaluation of macrolide resistance and enhanced molecular typing of Treponema pallidum in patients with syphilis in Taiwan: a prospective multicenter study. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012;50(7):2299–304. 10.1128/JCM.00341-12 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3405618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lukehart SA, Godornes C, Molini BJ, Sonnett P, Hopkins S, Mulcahy F, et al. Macrolide resistance in Treponema pallidum in the United States and Ireland. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(2):154–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa040216 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliver S, Sahi SK, Tantalo LC, Godornes C, Neblett Fanfair R, Markowitz LE, et al. Molecular Typing of Treponema pallidum in Ocular Syphilis. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43(8):524–7. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000478 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5253705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pospisilova P, Grange PA, Grillova L, Mikalova L, Martinet P, Janier M, et al. Multi-locus sequence typing of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum present in clinical samples from France: Infecting treponemes are genetically diverse and belong to 18 allelic profiles. PloS one. 2018;13(7):e0201068 Epub 2018/07/20. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201068 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6053231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flasarova M, Pospisilova P, Mikalova L, Valisova Z, Dastychova E, Strnadel R, et al. Sequencing-based molecular typing of treponema pallidum strains in the Czech Republic: all identified genotypes are related to the sequence of the SS14 strain. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(6):669–74. Epub 2012/03/22. 10.2340/00015555-1335 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flasarova M, Smajs D, Matejkova P, Woznicova V, Heroldova-Dvorakova M, Votava M. [Molecular detection and subtyping of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum in clinical specimens]. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2006;55(3):105–11. Epub 2006/09/15. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.