Abstract

There is a strong link between hypoperfusion and white matter (WM) damage in patients with leukoaraiosis and vascular cognitive impairment (VCI). Other than management of vascular risk factors, there is no treatment for WM damage and VCI that delays progression of the disease process to dementia. Observational studies suggest that exercise may prevent or slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and VCI. However, getting patients to exercise is challenging especially with advancing age and disability. Remote ischemic conditioning, an “exercise equivalent”, allows exercise to be given with a “device” in the home for long periods of time. Since RIC increases CBF in pre-clinical studies and in humans, RIC may be an ideal therapy to treat VCI and WM disease and perhaps even sporadic AD. By using MRI imaging of WM progression, a sample size in the range of about 100 subjects per group could determine if RIC has activity in WM disease and VCI.

The prevalence of dementia is expected to triple by 2050 making it a major threat to world public health.(1) In the last few decades, there has been an “Alzheimerization” of dementia with a tendency to attribute all cognitive decline to Alzheimer’s disease (AD).(2) This view is now being challenged and revised with the pendulum swinging back to the recognition of the major contribution of vascular causes to dementia.(1, 3–5) Vascular dementia makes up to 20% of the cases of dementia.(4, 6) However, many more cases of dementia are of “mixed” etiology with the estimates of “mixed dementia” related to AD and vascular causes ranging up to 50% of cases of dementia. Moreover, cerebral ischemia worsens AD and triggers its clinical expression. In the Nun Study, among participants fulfilling neuropathological criteria for AD, those with brain infarcts had a much higher prevalence of dementia.(7) Participants with lacunar infarcts in the basal ganglia, thalamus, or deep white matter had an odds ratio for dementia of 20.7 compared to those without infarcts.(7)

The National Alzheimer’s Project Act, signed into law in the United States in 2011, mandates a National Plan to address AD. In the plan, the term “Alzheimer’s” includes not only Alzheimer disease (AD) proper, but also Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders. Among these related disorders are vascular dementia and mixed dementia.(8) Recognizing the vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and AD, in 2013 the Alzheimer’s Association together with the National Institutes of Health convened a panel to outline steps to move the research field of vascular contributions to cognitive impairment forward.(9) The National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (NINDS) Stroke Progress Review Group in 2012 cited “prevention of vascular cognitive impairment” as a major research priority.

AD and CBF

Cerebral hypoperfusion is an early finding in AD and may play a role in the pathogenesis of AD.(10–12) In AD, low cerebral blood flow (CBF) is an early finding that precedes deposition of amyloid-beta. Patients with Autosomal Dominant AD have early CBF changes that precede any cognitive symptoms.(13) High amyloid-beta deposition in specific brain regions is associated with lower CBF in those same regions.(14) In the Rotterdam study, subjects with higher middle cerebral artery velocity by transcranial Doppler had a lower risk of dementia and higher middle cerebral artery velocity predicted less cognitive impairment in non-demented subjects, suggesting that hypoperfusion preceded cognitive decline.(15) One theory “critically attained threshold of cerebral hypoperfusion” (CATCH) proposes that impaired perfusion in the brain microvasculature triggers neuronal degeneration and cognitive dysfunction.(16–18) It is debated whether the low CBF reflects lowered neuronal metabolism or if it is a primary cause of neuronal dysfunction and amyloid-beta deposition. CBF has been proposed as a biomarker of AD similar to PET imaging of amyloid-beta.

A link between hypoperfusion, infarcts, and amyloid-beta deposition may be explained by dysfunction of the glymphatic system in the brain. Amyloid-beta accumulation is thought to be related to an imbalance between production and its clearance from the brain. Recent findings suggest that amyloid-beta clearance is mediated by astrocyte-mediated interstitial fluid bulk flow, the glymphatic system (g for “glia”). The glymphatics system involves three components: a.) transport from a para-arterial CSF influx route around penetrating arteries; b.) a para-venous ISF clearance route; and c.) a transparenchymal pathway that is dependent on astroglial water transport via the astrocytic aquaporin-4 (AQP4), that is polarized in location being expressed on perivascular astrocytes.(19–21) (22) Microinfarcts with accompanying astrogliosis impair polarization of AQP-4.(23) Moreover, the loss of arterial pulsatility with aging and the inflammation and gliosis often found in aging brain impair this glymphatic pathway and clearance of amyloid-beta.(24)Defects in this glymphatic clearance system from ischemia and infarcts may be related to deposition of amyloid-beta and tau and may provide the link between brain vascular disease and sporadic AD.

Vascular Cognitive Impairment

Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) is the term that encompasses the clinical spectrum from mild cognitive dysfunction to vascular dementia. The pathological hallmark of VCI is white matter (WM) damage from ischemia in the periventricular regions and centrum semiovale.(1, 5) The underlying pathology involves small vessel disease although hypertension only accounts for a small proportion of the risk.(25) The imaging correlate of this WM damage is “leukoaraiosis” best detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and almost always apparent by age 70. The degree and severity of leukoaraiosis is associated with cognitive impairment, depression, gait abnormalities and disability.(26) WM changes are mediated by blood brain barrier (BBB) leakage, microglial activation and injury to oligodendrocytes and myelin.(1).

Hypoperfusion of WM appears to be early finding and plays a pathophysiological role in development of WM damage. Reduction of CBF is an early finding in areas of leukoaraiosis.(27) The hemispheric white matter receives its blood supply through long penetrating arteries originating from the pial network on the surface of the brain (rami medullares) and the WM adjacent to the walls of the ventricles from penetrating vessels originating from the base of the brain (rami striati).(28) The location of WM damage in the periventricular area and deep white matter is likely related to this area being an arterial border zone or “watershed” zone susceptible to injury from systemic blood pressure drops or local decreases in CBF related to disease in these vessels. Low blood flow by MRI perfusion or MRI arterial spin labeling (ASL) in normal appearing white matter is predictive of these regions transitioning to white matter lesions.(29, 30) A CSF penumbra exists around white matter lesions that expands in relation to low CBF(30)

Exercise and physical activity and risk of dementia

There is a large body of evidence suggesting that physical exercise reduces the risk of cognitive decline and dementia (see review).(31) Moreover, physical activity reduces biomarkers of AD and dementia such as Position Emission Tomorgraphy (PET) amyloid-beta burden and hippocampal volumes on MRI. On volumetric MRI, physical activity was independently associated with greater whole brain and regional brain volumes and reduced ventricular dilation.(32) A physically active lifestyle is associated with lower amyloid burden on PET and higher hippocampal volumes by MRI.(33)

The LADIS Study (Leukoaraiosis and Disability Study) is a prospective multinational European cohort study that evaluates the impact of white matter changes on the transition of independent elderly subjects to disability. In 3 years of follow up, physical activity reduced the risk of cognitive decline and dementia. .(34) Physical activity also prevented decline of executive function in non-demented and non-cognitively impaired patients with “age-related white matter changes”.(35)

These observational studies support the concept that exercise may be an effective treatment for VCI and patients with early WM damage. While exercise and physical activity appear to reduce cognitive impairment and the risk of dementia, observational studies are limited and often confounded. There are a lack of randomized trials showing exercise reduces dementia or cognitive decline in AD or VCI. There also may be another explanation for the effect of exercise in observational studies. There is evidence that children and young adults with better cognitive function may select healthier lifestyles with more exercise, so called “neuroselection”(36)

Exercise and age

While physical activity and exercise are associated with lower risk of cognitive decline, older patients are less likely to exercise than younger patients. A telephone survey of over 450,000 in the US conducted by the Centers for Disease Control, found that only 20.6% of Americans met the aerobic and muscle-strengthening in the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.(37) While 30.7% of persons aged 18 to 24 years met the guidelines, this fell to 15.9% in those over age 65. Both age and educational status were significantly associated with exercise as older age and less education were associated with less exercise and physical activity. Therefore, as patients age they are less willing or less able to exercise. Since exercise is difficult to enforce and many patients are unwilling or unable to exercise, an alternative is to develop therapies that are equivalent to “exercise in a pill” or “exercise in a device”.

Ischemic Preconditioning and Remote Ischemic Conditioning

Ischemic preconditioning is one of the most potent cardioprotectants and neuroprotectants known. Ischemic preconditioning like other forms of preconditioning trigger endogenous protective pathways and allow the brain to “self protect”. First described in 1986 by Murry in the canine heart,(38) it was soon learned that ischemic conditioning could be applied regionally and then remotely in other organs and finally with a blood pressure cuff on the limbs, making it highly translatable.

Remote ischemic conditioning (RIC) involves repeated (blood pressure) cuff inflations on the arm or leg to reduce ischemic damage in a distant organ such as the heart, kidney or brain. RIC can be applied before ischemia (Pre-), during ischemia (Per-) or after ischemia and during reperfusion (Post-) There are a large number of randomized clinical trials of remote limb preconditioning to protect the heart suggestive of benefit.(39) RLIC effectively reduces MI when used in the pre-hospital setting before percutaneous coronary interventions.(40)

A large number of preclinical studies indicate that RIC is effective at reducing injury in focal cerebral ischemia models (see review).(41)RIC improves CBF, reduces ischemic damage and also attenuates adverse effects of late IV-tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) in a mouse embolic stroke model.(42) Moreover, the effects are sex independent as ovariectomized female mice also benefit.(43) A recent clinical trial of RIC in the pre-hospital setting in acute stroke did not show efficacy in its primary endpoint; but most patients did not receive the full regimen and a post hoc “tissue analysis” demonstrated an overall significantly reduced risk of infarction in patients randomized to RIC.(44) A consistent finding is that RIC increases CBF in multiple brain injury models making it an attractive therapy for VCI.(42, 43, 45)

Chronic RIC. In an insidious progressing disease such as VCI or vascular dementia, a therapy will need to administered early in the course and chronically, perhaps for months or even years. There is evidence demonstrating that RIC can be applied chronically and daily in the home. Two small randomized clinical trials of chronic RIC in patients with intracranial stenosis showed safety, tolerability and efficacy with a reduction in stroke or stroke and TIA.(46, 47) RIC was safe and well tolerated as patients were treated for 6 months and 300 days, indicating long-term feasibility. RIC increased CBF as measured by SPECT.(46) Similarly, chronic RIC daily in the home could be adapted for VCI, as an “exercise equivalent”, a therapy easier to adopt for aged individuals.

RIC: an exercise equivalent?

Preconditioning and exercise may share common mechanisms and protective pathways. Brief, intense exercise “preconditions” dog hearts and is similar to classical ischemic preconditioning with an early and late phase.(48) Similarly, RIC and exercise may share common mechanisms of protection. Dialysates prepared from plasma from human subjects undergoing vigorous exercise or remote limb conditioning both were protective in an isolated rabbit Langendorff heart preparation.(49) The opioid antagonist, naloxone blocked the effects of dialysates from both exercisers and those undergoing RIC suggesting that common humoral mediators are shared by exercise and RIC.(49) Exercise acts as a form of “remote” conditioning. Alternatively, RIC can be viewed as an “exercise equivalent” and may confer the benefits of exercise to patients unable to unwilling to exercise.

Animal models of VCI

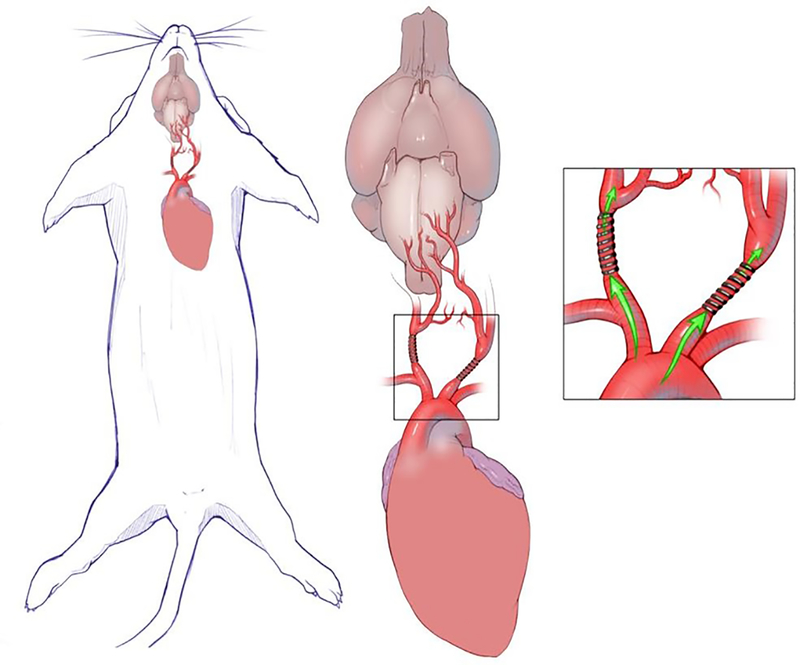

There are a number of proposed animal models for VCI. In a recent review of all mouse models for VCI and vascular dementia, Bink determined the mouse bilateral carotid artery stenosis (BCAS) model to be the most valid.(50) Microcoils are placed around the extracranial carotid arteries with reduction of cerebral blood flow. (figure) This model reproduces the WM damage, cerebral hypoperfusion, inflammation, BBB damage and cognitive deficits of the human condition.(51, 52) There are also fibrinoid changes in the small vessels of the brain with gliosis and disruption of aquaporin polarization.(53) With these small vessel changes, the BCAS model may be useful to test interventions to treat small vessel disease of the brain.(53)

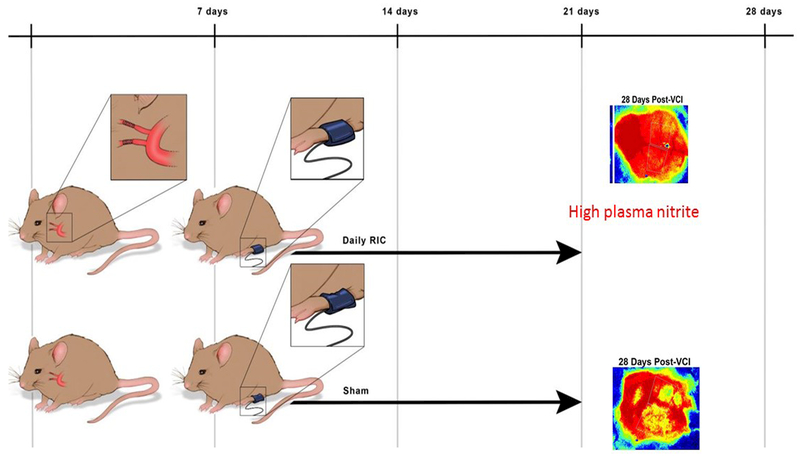

RIC was tested daily for two weeks in C57/B6 male mice (10-weeks old) subjected to BCAS using microcoils to induce cerebral chronic hypoperfusion.(45) (Figure 2) Mice were randomized into 3 groups: a sham-operated group, BCAS with daily sham RIC and BCAS with daily RIC. CBF was measured using high-resolution laser speckle contrast imager. There was no significant difference between baseline CBF of BCAS with sham RIC and BCAS with RIC (before and immediately after BCAS). RIC or sham RIC was started 7 days after BCAS surgery. After 7 days of RIC treatment, there was a significant increase in CBF compared to sham RIC. RIC therapy was continued for 1 more week up to day 21 post-BCAS and then discontinued for the next 1 week. When measured at day 28, the RIC significantly increased CBF even after the RIC therapy was discontinued for a week. This demonstrated a sustained effect on CBF even after the cessation of RIC

Figure 2:

Depiction of randomization of mice to RIC (top) and RIC sham (bottom). (Sham BCA group not shown) There was a significant increases in CBF by laser speckle contrast imaging at 28 days and rise in plasma nitrite in the mice treated with RIC

At 28 days BCAS significantly triggered the accumulation of Aβ42 (4 fold) and increased inflammation as measured by ICAM and VCAM and microglial activation, gliosis, demyelination and subsequent cell death. RIC therapy for 2 weeks attenuated upregulation of ICAM and VCAM, microglial activation, and decreased the Aβ42 (2 fold) accumulation in RIC as compared to sham RIC, leading to attenuation of WM degeneration. RIC also improved cognition as measured by the novel object recogntion test. These results indicate that RIC improves CBF, improves cognition, reduces inflammation and white matter damage and reduces amyloid accumulation in a BCAS model.(45)

Mechanism of action of RIC

The mechanism of action of RIC in neuroprotection is no precisely known but likely involves humoral factors and neural loops, especially type C afferents and the autonomic nervous system.(54) Chronic RIC also has anti-inflammatory effects and stimulates autophagy.(55, 56) Humoral mediators associated with the cardioprotective effect of RIC include stromal derived factor 1,(57) IL-10,(58)micro RNA-144,(59) and nitrite.(60). Moreover, opioids appear to play a role in the protective effect of both exercise and RIC.(49)

The eNOS/NO/nitrite system

The eNOS/NO system plays a key role in regulating CBF in the brain and in the processing of amyloid-beta and may serve as the link between vascular dysfunction and impaired cognition in AD.(61, 62) Inhibition of “vascular nitric oxide (NO)” after chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in the rat causes immunocytochemical changes in the brain leading to loss in learning and spatial memory function.(63) Plasma nitrite reflects endothelial NO production and improved endothelial function.(64) Endothelial NO produced remotely can be delivered via plasma nitrite to protect a distant ischemic organ such as the brain, an “endocrine effect” of NO.(65) Rassaf and colleagues recently showed that circulating nitrite mediates the cardioprotective effect of RIC in a myocardial infarction model.(60) Mice undergoing BCAS have lower plasma nitrite and RIC increases plasma nitrite in the mouse BCAS model.(66) (67) Plasma nitrite mediates hypoxic vasodilation via reduction to NO by hemoglobin and other heme moieties.(68–75) This suggests that plasma nitrite may be the mediator of the increased CBF observed after RIC and may serve as a blood biomarker of the conditioning response. The eNOS/NO system may also underlie the beneficial effects of exercise in cerebral ischemia. In a mouse model of acute ischemic stroke, the beneficial effects of exercise- improving recovery and increased CBF- are abrogated in eNOS knockout mice.(76) Thus, the mechanism of both exercise and RIC may be eNOS dependent. While the effects of RIC are pleotropic and likely involve multiple mechanisms, enhancement of the eNOS/NO/nitrite system may underlie the beneficial effects of RIC in the BCAS model and may be important in VCI patients.

Future Perspectives

RIC may be an effective treatment for VCI and in patients with WM and small vessel disease. RIC appears to increase CBF and in a mouse BCAS model improves cognition and reduces inflammation. Clinical trials already show that RI can be applied chronically for up to 300 day in the home with safety and tolerability. An ongoing clinical trial is evaluating the safety, feasibility, and effect of RIC on WM damage on MRI in patients with recent lacunar infarct and WM disease. (REM-PROTECT Clinicaltrials.gov NCT0218992) Using participant and MRI data from the LADIS study, WM progression would only require a sample size of 58 to 70 subjects per treatment arm(77) Similarly, data from the prospective St George’s Cognition and Neuroimaging in Stroke study (SCANS) suggests that MRI WM and DTI measurements would allow sample sizes in the 100s.(78) The time has arrived to evaluate RIC in patients with VCI. A clinical trial with a sample size as small as about 100 per group using WM progression of DTI as a biomarker would determine if RIC has ‘activity” in VCI and WM disease.

Figure 1:

Depiction of bilateral carotid stenosis model in mice with microcoils applied to the extracranial carotid arteries

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Colby Polonsky, Medical Illustrator, Georgia Regent’s University Supported by NIH/NINDS R21NS090609–01A1

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Iadecola C The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron. 2013;80(4):844–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libon DJ, Price CC, Heilman KM, Grossman M. Alzheimer’s “other dementia”. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2006;19(2):112–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jellinger KA. Pathology and pathogenesis of vascular cognitive impairment-a critical update. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42(9):2672–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iadecola C The overlap between neurodegenerative and vascular factors in the pathogenesis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120(3):287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pantoni L, Gorelick P. Advances in vascular cognitive impairment 2010. Stroke. 2011;42(2):291–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. Jama. 1997;277(10):813–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montine TJ, Koroshetz WJ, Babcock D, Dickson DW, Galpern WR, Glymour MM, et al. Recommendations of the Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias conference. Neurology. 2014;83(9):851–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder HM, Corriveau RA, Craft S, Faber JE, Greenberg SM, Knopman D, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia including Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2015;11(6):710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z Characterizing early Alzheimer’s disease and disease progression using hippocampal volume and arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2014;42 Suppl 4:S495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Das SR, Xie SX, Arnold SE, Detre JA, Wolk DA, et al. Arterial spin labeled MRI in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: A multi-site study. NeuroImage Clinical. 2013;2:630–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wierenga CE, Hays CC, Zlatar ZZ. Cerebral blood flow measured by arterial spin labeling MRI as a preclinical marker of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2014;42 Suppl 4:S411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDade E, Kim A, James J, Sheu LK, Kuan DC, Minhas D, et al. Cerebral perfusion alterations and cerebral amyloid in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2014;83(8):710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattsson N, Tosun D, Insel PS, Simonson A, Jack CR Jr., Beckett LA, et al. Association of brain amyloid-beta with cerebral perfusion and structure in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2014;137(Pt 5):1550–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruitenberg A, den Heijer T, Bakker SL, van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, et al. Cerebral hypoperfusion and clinical onset of dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Annals of neurology. 2005;57(6):789–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de la Torre JC. Critical threshold cerebral hypoperfusion causes Alzheimer’s disease? Acta neuropathologica. 1999;98(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de la Torre JC. Cerebral hemodynamics and vascular risk factors: setting the stage for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2012;32(3):553–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de la Torre JC, Stefano GB. Evidence that Alzheimer’s disease is a microvascular disorder: the role of constitutive nitric oxide. Brain research Brain research reviews. 2000;34(3):119–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, Feng T, Logan J, Nedergaard M, et al. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(3):1299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iliff JJ, Nedergaard M. Is there a cerebral lymphatic system? Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44(6 Suppl 1):S93–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Science translational medicine. 2012;4(147):147ra11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, Glodzik L, Butler T, Fieremans E, et al. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nature reviews Neurology. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Wang M, Iliff JJ, Liao Y, Chen MJ, Shinseki MS, Venkataraman A, et al. Cognitive deficits and delayed neuronal loss in a mouse model of multiple microinfarcts. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32(50):17948–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kress BT, Iliff JJ, Xia M, Wang M, Wei HS, Zeppenfeld D, et al. Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Annals of neurology. 2014;76(6):845–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wardlaw JM, Allerhand M, Doubal FN, Valdes Hernandez M, Morris Z, Gow AJ, et al. Vascular risk factors, large-artery atheroma, and brain white matter hyperintensities. Neurology. 2014;82(15):1331–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poggesi A, Pantoni L, Inzitari D, Fazekas F, Ferro J, O’Brien J, et al. 2001–2011: A Decade of the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis And DISability) Study: What Have We Learned about White Matter Changes and Small-Vessel Disease? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(6):577–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Sullivan M, Lythgoe DJ, Pereira AC, Summers PE, Jarosz JM, Williams SC, et al. Patterns of cerebral blood flow reduction in patients with ischemic leukoaraiosis. Neurology. 2002;59(3):321–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pantoni L, Garcia JH. Pathogenesis of leukoaraiosis: a review. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1997;28(3):652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernbaum M, Menon BK, Fick G, Smith EE, Goyal M, Frayne R, et al. Reduced blood flow in normal white matter predicts development of leukoaraiosis. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Promjunyakul N, Lahna D, Kaye JA, Dodge HH, Erten-Lyons D, Rooney WD, et al. Characterizing the white matter hyperintensity penumbra with cerebral blood flow measures. NeuroImage Clinical. 2015;8:224–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes JN. Exercise, cognitive function, and aging. Advances in physiology education. 2015;39(2):55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyle CP, Raji CA, Erickson KI, Lopez OL, Becker JT, Gach HM, et al. Physical activity, body mass index, and brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2015;36 Suppl 1:S194–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okonkwo OC, Schultz SA, Oh JM, Larson J, Edwards D, Cook D, et al. Physical activity attenuates age-related biomarker alterations in preclinical AD. Neurology. 2014;83(19):1753–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verdelho A, Madureira S, Ferro JM, Baezner H, Blahak C, Poggesi A, et al. Physical activity prevents progression for cognitive impairment and vascular dementia: results from the LADIS (Leukoaraiosis and Disability) study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43(12):3331–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frederiksen KS, Verdelho A, Madureira S, Bazner H, O’Brien JT, Fazekas F, et al. Physical activity in the elderly is associated with improved executive function and processing speed: the LADIS Study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2015;30(7):744–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belsky DW, Caspi A, Israel S, Blumenthal JA, Poulton R, Moffitt TE. Cardiorespiratory fitness and cognitive function in midlife: neuroprotection or neuroselection? Annals of neurology. 2015;77(4):607–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris CD, Watson KB, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Dorn JM Adult participation in aerobic and muscle-strenghening physical activites-United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2013;62(17):326–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74(5):1124–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brevoord D, Kranke P, Kuijpers M, Weber N, Hollmann M, Preckel B. Remote Ischemic Conditioning to Protect against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e42179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Botker HE, Kharbanda R, Schmidt MR, Bottcher M, Kaltoft AK, Terkelsen CJ, et al. Remote ischaemic conditioning before hospital admission, as a complement to angioplasty, and effect on myocardial salvage in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9716):727–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hess DC, Hoda MN, Bhatia K. Remote limb perconditioning [corrected] and postconditioning: will it translate into a promising treatment for acute stroke? Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44(4):1191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoda MN, Siddiqui S, Herberg S, Periyasamy-Thandavan S, Bhatia K, Hafez SS, et al. Remote ischemic perconditioning is effective alone and in combination with intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator in murine model of embolic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43(10):2794–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoda MN, Bhatia K, Hafez SS, Johnson MH, Siddiqui S, Ergul A, et al. Remote ischemic perconditioning is effective after embolic stroke in ovariectomized female mice. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5(4):484–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hougaard KD, Hjort N, Zeidler D, Sorensen L, Norgaard A, Hansen TM, et al. Remote ischemic perconditioning as an adjunct therapy to thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a randomized trial. Stroke. 2014;45(1):159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan MB, Hoda MN, Vaibhav K, Giri S, Wang P, Waller JL, et al. Remote ischemic postconditioning: harnessing endogenous protection in a murine model of vascular cognitive impairment. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6(1):69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meng R, Asmaro K, Meng L, Liu Y, Ma C, Xi C, et al. Upper limb ischemic preconditioning prevents recurrent stroke in intracranial arterial stenosis. Neurology. 2012;79(18):1853–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meng R, Ding Y, Asmaro K, Brogan D, Meng L, Sui M, et al. Ischemic Conditioning Is Safe and Effective for Octo- and Nonagenarians in Stroke Prevention and Treatment. Neurotherapeutics. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Domenech R, Macho P, Schwarze H, Sanchez G. Exercise induces early and late myocardial preconditioning in dogs. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55(3):561–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michelsen MM, Stottrup NB, Schmidt MR, Lofgren B, Jensen RV, Tropak M, et al. Exercise-induced cardioprotection is mediated by a bloodborne, transferable factor. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107(3):260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bink DI, Ritz K, Aronica E, van der Weerd L, Daemen MJ. Mouse models to study the effect of cardiovascular risk factors on brain structure and cognition. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(11):1666–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shibata M, Ohtani R, Ihara M, Tomimoto H. White matter lesions and glial activation in a novel mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Stroke. 2004;35(11):2598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shibata M, Yamasaki N, Miyakawa T, Kalaria RN, Fujita Y, Ohtani R, et al. Selective impairment of working memory in a mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Stroke. 2007;38(10):2826–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holland PR, Searcy JL, Salvadores N, Scullion G, Chen G, Lawson G, et al. Gliovascular disruption and cognitive deficits in a mouse model with features of small vessel disease. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2015;35(6):1005–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hess DC, Hoda MN, Bhatia K. Remote Limb Preconditioning and Postconditioning: Will It Translate Into a Promising Treatment for Acute Stroke? Stroke. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rohailla S, Clarizia N, Sourour M, Sourour W, Gelber N, Wei C, et al. Acute, delayed and chronic remote ischemic conditioning is associated with downregulation of mTOR and enhanced autophagy signaling. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei D, Ren C, Chen X, Zhao H. The chronic protective effects of limb remote preconditioning and the underlying mechanisms involved in inflammatory factors in rat stroke. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davidson SM, Selvaraj P, He D, Boi-Doku C, Yellon RL, Vicencio JM, et al. Remote ischaemic preconditioning involves signalling through the SDF-1alpha/CXCR4 signalling axis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108(5):377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cai ZP, Parajuli N, Zheng X, Becker L. Remote ischemic preconditioning confers late protection against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice by upregulating interleukin-10. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107(4):277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li J, Rohailla S, Gelber N, Rutka J, Sabah N, Gladstone RA, et al. MicroRNA-144 is a circulating effector of remote ischemic preconditioning. Basic Res Cardiol. 2014;109(5):423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rassaf T, Totzeck M, Hendgen-Cotta UB, Shiva S, Heusch G, Kelm M. Circulating nitrite contributes to cardioprotection by remote ischemic preconditioning. Circ Res. 2014;114(10):1601–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Austin SA, d’Uscio LV, Katusic ZS. Supplementation of nitric oxide attenuates AbetaPP and BACE1 protein in cerebral microcirculation of eNOS-deficient mice. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2013;33(1):29–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katusic ZS, Austin SA. Endothelial nitric oxide: protector of a healthy mind. European heart journal. 2014;35(14):888–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de la Torre JC, Aliev G. Inhibition of vascular nitric oxide after rat chronic brain hypoperfusion: spatial memory and immunocytochemical changes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25(6):663–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagababu E, Rifkind JM. Measurement of plasma nitrite by chemiluminescence. Methods in molecular biology. 2010;610:41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Bryan NS, Lefer DJ. Nitric oxide promotes distant organ protection: evidence for an endocrine role of nitric oxide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(32):11430–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, et al. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399(6736):597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hess DC, Hoda MN, Khan MB Humoral mediators of remote ischemic conditioning:important role of eNOS/NO/nitrite. Acta Neurochirurgica Supplement. 2015;121(in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alef MJ, Vallabhaneni R, Carchman E, Morris SM Jr., Shiva S, Wang Y, et al. Nitrite-generated NO circumvents dysregulated arginine/NOS signaling to protect against intimal hyperplasia in Sprague-Dawley rats. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121(4):1646–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grubina R, Basu S, Tiso M, Kim-Shapiro DB, Gladwin MT. Nitrite reductase activity of hemoglobin S (sickle) provides insight into contributions of heme redox potential versus ligand affinity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(6):3628–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hendgen-Cotta UB, Merx MW, Shiva S, Schmitz J, Becher S, Klare JP, et al. Nitrite reductase activity of myoglobin regulates respiration and cellular viability in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(29):10256–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2008;7(2):156–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mack AK, McGowan Ii VR, Tremonti CK, Ackah D, Barnett C, Machado RF, et al. Sodium nitrite promotes regional blood flow in patients with sickle cell disease: a phase I/II study. British journal of haematology. 2008;142(6):971–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Nitrite mediates cytoprotection after ischemia/reperfusion by modulating mitochondrial function. Basic research in cardiology. 2009;104(2):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shiva S, Sack MN, Greer JJ, Duranski M, Ringwood LA, Burwell L, et al. Nitrite augments tolerance to ischemia/reperfusion injury via the modulation of mitochondrial electron transfer. J Exp Med. 2007;204(9):2089–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Totzeck M, Hendgen-Cotta UB, Luedike P, Berenbrink M, Klare JP, Steinhoff HJ, et al. Nitrite regulates hypoxic vasodilation via myoglobin-dependent nitric oxide generation. Circulation. 2012;126(3):325–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gertz K, Priller J, Kronenberg G, Fink KB, Winter B, Schrock H, et al. Physical activity improves long-term stroke outcome via endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent augmentation of neovascularization and cerebral blood flow. Circulation research. 2006;99(10):1132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmidt R, Berghold A, Jokinen H, Gouw AA, van der Flier WM, Barkhof F, et al. White matter lesion progression in LADIS: frequency, clinical effects, and sample size calculations. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43(10):2643–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benjamin P, Zeestraten E, Lambert C, Ster IC, Williams OA, Lawrence AJ, et al. Progression of MRI markers in cerebral small vessel disease: sample size considerations for clinical trials. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]