Abstract

As a continuous source of hormonal stimulation, environmentally ubiquitous estrogenic chemicals, ie, xenoestrogens (XEs), are a potential risk factor for breast carcinogenesis. Given their wide distribution in the environment and the fact that bisphenol-A (BPA), methylparaben (MP), and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) are uniformly detected in unselected body fluid samples, it must be assumed that humans are simultaneously exposed to these chemicals almost daily. We studied the effects of a ternary mixture of BPA, MP, and PFOA on benign breast epithelial cells at the range of concentrations observed for single chemicals in human samples. Measurements of exposure impact relevant to the breast were based on endpoints associated with “hallmarks” of cancer and “key characteristics” of carcinogens. These included modulation of total estrogen receptor (ER)α, phosphorylated ERα (pERα), total ERβ, S-phase induction, and apoptotic evasion. Data from live cell measurements were fit to a log-linear dose-response model. Concentration-dependent reduction of ERβ and apoptosis evasion was observed concurrently with the induction of ERα, pERα, and S-phase fraction, and an increased rate of cell proliferation. Beyond additive effects predicted by the sum of individual test XEs, mixture treatment demonstrated synergism for the ERβ and apoptosis suppression phenotypes (p > .001). Nonmalignant breast cells were more sensitive than commonly used breast cancer lines to XE treatment in 3 of 5 endpoints. All observations were validated with cells isolated from the normal breast tissue of 14 individuals. At relatively low concentrations, a chemical mixture has striking effects on normal cell function that are missed by evaluation of single components.

Keywords: breast cancer, endocrine disruptors, estrogen receptors, apoptosis, chemical mixtures

There are at least 2 unmet challenges in current paradigms for using in vitro tests to estimate human risk for breast cancer posed by common chemicals of commerce. First, chemicals are mostly tested individually rather than as mixtures. Such a hazard testing approach assumes that each chemical exerts its effect(s) individually, in parallel, and superimposed on those of other chemicals in the mixture so that the effect at a given concentration is the same as, but no greater than, the greatest effect of the single, most active component of the mixture. Since human exposure to common chemicals is virtually always to a mixture, it is not possible to know if a chemical is safe until it is evaluated in its typical context as one component of a mixture, and in conjunction with other chemicals to which individuals are similarly and commonly exposed. For example, a recent case-control study links the risk of human breast cancer to the total estrogenic effect of the mixture of test chemicals in serum, rather than to individual chemicals (Pastor-Barriuso et al., 2016). Similarly, single xenoestrogens (XEs) negative in the rat uterotrophic assay display a positive response as mixtures (Tinwell and Ashby, 2004). The compounded effects of weakly estrogenic chemicals within mixtures might be amenable as well to rapid in vitro testing if appropriate test targets and endpoints were identified and employed.

The second poorly addressed challenge is in employing test systems that are representative of carcinogen-targeted epithelial cells in the human breast—the cells it is hoped will not become malignant. Arguably, much has been learned from in vitro studies of the effects of single XEs in breast cancer cell lines (Lapensee et al., 2010; Pfeifer et al., 2015; Sauer et al., 2017; Soto et al., 1995) but these studies beg the lingering question of whether results in extensively genetically deranged malignant cell lines accurately reflect the consequences of chemical exposure within breast cells before they become malignant. We, and others have contributed to the current literature on the effects of single XEs, such as bisphenol-A (BPA), on nonmalignant human breast cells, demonstrating a mechanistic basis for the induction of resistance to cell death and activation of the cell cycle (Dairkee et al., 2013; Fernandez et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2013).

Using ER-positive nonmalignant human breast cell lines previously isolated by us (Goodson et al., 2011), we evaluate the effects of exposure to a mixture of 3 structurally unrelated and environmentally high-abundance XEs at a concentration range reportedly detected in human specimens. We demonstrate that: 1. The XE test mixture intensifies the downstream impact of estrogenic signaling related to estrogen receptor (ER) modulation, cell growth, and evasion of apoptosis at closely similar levels to natural estradiol, and 2. The combination of XEs has significantly greater effects than individual components of the mixture on specific test endpoints. We then confirm the validity of these findings in primary cultures of nonmalignant, nonimmortalized high risk breast epithelial cells (HRBECs) sampled directly from human volunteers—that have not been selected for long term growth in vitro—to demonstrate general relevance to human breast cells widely targeted by this chemical mixture in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of XE test concentrations

Comprising the mixture tested in this study are 3 common consumer use chemicals representing structurally different classes—BPA, methylparaben (MP), and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). The rationale for a mixture of these chemicals is their high volume commercial distribution and consequently widespread human exposure as shown by data from the NHANES-CDC (2015) and Health Canada (2017). Notably, the selected concentration range in our study is directly relevant to human exposure as it encompasses population-based levels associated with tissues and body fluids (Table 1). Additional factors considered in the selection of the chemical concentrations used in this study were that: (1) The lowest test level was lower than that found in human sampling. (2) The test exposure range (1, 10, and 100 nM for BPA and PFOA, 10, 100 nM, and 1 µM for MP, and 1 nM BPA +1 nM PFOA +10 nM MP, 10 nM BPA +10 nM PFOA +100 nM MP, and 100 nM BPA +100 nM PFOA +1 µM MP for the XE mixture) represents a log10 increase between treatment concentrations in order to effectively span variation in human levels. (3) Effects of single XEs versus mixture represented paired comparisons of each cell line or primary culture for all test concentrations and endpoints.

Table 1.

Environmental XE Levels in Human Biological Samples and Experimental Test Concentrations

| Chemical Concentration (ng/ml) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | BPA | MP | PFOA | References |

| Urine | 1.83 | 57 | 3.07 | CDC (2015) |

| 1.14 | 104 | Artacho-Cordón et al. (2017) | ||

| Serum | 0.67 | 3.2 | CDC (2015), Artacho-Cordón et al. (2017) | |

| Adipose tissuea | 0.6 | 0.6 | Artacho-Cordón et al. (2017) | |

| Placentaa | 4.01 | 1.5 | 0.46 | Chen et al. (2017), Fernández et al. (2016), Vela-Soria et al. (2017) |

| 2.27 | Fernández et al. (2016) | |||

| Maternal blood | 0.81 | 0.92 | 1.8 | Beesoon et al. (2011), Shekhar et al. (2017) |

| Cord blood | 1.1 | Beesoon et al. (2011) | ||

| Amniotic fluid | 5.38 | 11.11 | Shekhar et al. (2017) | |

| Human milk | 3.8 | Kärrman et al. (2007) | ||

| Concentration applied to breast cells in current study (Molar equivalents in parentheses) | 0.22, 2.22, 22.2 (1, 10, and 100 nM) | 1.52, 15.2, 152 (10, 100 nM, and 1 μM) | 0.41, 4.14, 41.4 (1, 10, and 100 nM) | |

Values from human samples represent average or upper limit.

Concentrations noted as ng/g of tissue.

Cell culture and XE treatment

Spontaneously immortalized HRBEC lines, designated as PA024, PA025, and PA115 were previously isolated from donor-derived nonmalignant random periareolar fine needle aspirates (RPFNA) of the unaffected contralateral breast of patients undergoing surgical procedures for benign or malignant disease (Goodson et al., 2011) and used here at passage 25–30. Additionally, primary HRBEC cultures were developed from fresh nonmalignant RPFNA samples acquired from human donors with written informed consent approved by the California Pacific Medical Center Institutional Review Board as previously described in Dairkee et al. (2008, 2013), Goodson et al. (2011), and Luciani-Torres et al. (2015). Each RPFNA cell suspension was divided into aliquots for cytopathology and cell culture. The cytology aliquot collected in Cytolyt, was transferred onto ThinPrep microscope slides as a 20-mm circle, stained and mounted for evaluation by a board-certified cytopathologist (I.M.J.) for the presence of cytological atypia among epithelial and stromal cell clusters. Finite-life primary RPFNA cultures generated and assayed here are described in the text in the order of sample accession from PA199 to PA222. Established breast cancer cell lines, T47D, MDA231, and SKBR3, were expanded in RPMI + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and MCF7 in DMEM + 10% FBS. For identity control and cell line authentication, total DNA was amplified with 9 sets of PCR primers commonly used for DNA Fingerprinting. The PCR products were run on 10% Tris-borate-EDTA-polyacrylamide gels and visualized by ethidium bromide. Each HRBEC cell line was confirmed to display a unique short tandem repeat profile.

Stock solutions of 17β-estradiol (E2) and the chemicals, BPA, MP, and PFOA were prepared in ethanol and stored at −20°C. These stocks were used to generate dilutions that were kept constant for all treatments and endpoint assays. For exposure to test compounds, cells were seeded in 6-well, 96-well, or 100-mm plates and treated without change of growth media for 7-d at indicated concentrations: low (BPA, PFOA—1 nM; MP—10 nM; XE mixture—1 + 1 + 10 nM of the respective XEs), intermediate (BPA, PFOA—10 nM; MP—100 nM; XE mixture—10 + 10 + 100 nM of the respective XEs), and high (BPA, PFOA—100 nM; MP—1 µM; XE mixture—100 + 100 nM + 1 µM of the respective chemicals). During test conditions, cells were maintained in phenol red-free formulations of their optimal growth medium, supplemented with charcoal-stripped FBS at reduced levels that did not affect baseline cell survival (0.2% for HRBECs, and 1% for breast cancer cell lines). All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, Missouri).

Protein isolation and Western blot analysis

To generate protein lysates, cells were lysed in a nondenaturing NP-40 buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.1% NP40, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol containing protease, and phosphatase inhibitors). Total proteins resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE gels were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, incubated with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies, and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. GAPDH served as a loading control.

Primary antibodies directed at test proteins included: ERα, phosphorylated ERα(S118) (pERα) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California), ERβ, and GAPDH (Genetex, Irvine, California). To evaluate quantitative changes in ER isoforms induced by exposure to E2 or XE mixture, treated and untreated cultures of each test sample were processed in parallel and resolved in adjacent lanes within the same gel.

Multiplexed quantitation of ER isoforms by fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Treated, or control cell populations were trypsinized, washed with growth medium, and fixed with 70% ethanol. Cell pellets were stored at −20°C until analyzed. Prior to use, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X, blocked with PBS + 10% FBS, and simultaneously incubated with the above-mentioned primary antibodies, and subsequently with species-specific fluorescence-tagged secondary antibodies matched to each of the primary antibodies. Immunostained cells were resuspended in PBS and analyzed with the Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California) in duplicate runs. Each run represented 104 cells. Background fluorescence detected in no primary antibody control samples was subtracted from the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of all untreated and test samples.

Quantitation of apoptosis evasion

Apoptosis was induced by 24-h treatment with 10 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (OHT). Unfixed cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC (BD Biosciences) following manufacturer’s instructions and analyzed by FACScan (BD Biosciences). Data were acquired from replicates, each consisting of 104 cells. Apoptosis values for each XE treatment were normalized to the baseline (no OHT) sample for each treatment group prior to comparison of results between OHT, single XE, and mixture-treated groups.

Measurement of cell proliferation

DNA synthesis was quantitated by incorporation of 10 mM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1-h into 2-4 replicate cell cultures and subsequently fixed with 70% ethanol. Fixed cells were stained with anti BrdU (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York), counterstained with propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed by FACScan using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Labeling and estimating BrdU-positive cells among the total number of PI-stained cells allowed the clear separation of cells in G1 from early S phase, or late S phase from G2/M, providing an accurate measure of cells in the various stages of the cell cycle (Cecchini et al., 2012).

Additionally, growth curves of XE-treated cells were generated from test cultures plated in 96-well plates at 103 cells/well for defined exposure periods. The PrestoBlue Cell Viability Reagent (Life Technologies) was directly added to the culture medium to quantitate live, metabolically active cells, which reduce the reagent to a fluorescent state. Fluorescence was measured at 560/590 nm excitation/emission and plotted as units derived from treated samples relative to untreated control. Background fluorescence was corrected by subtracting readings on growth medium in control wells without cells from each experimental well. Each data point represented 6 replicates.

Statistical methods for analyzing XE response data

All fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) data were acquired as MFI. Data points derived from 2 to 6 replicates were summarized as mean ± SD. For analysis of FACS-derived raw data, we expressed cell perturbation as a relative effect where each MFI value was normalized to the untreated control for each target across all treatments and experimental endpoints. Apoptosis values for each treatment were normalized to the no-OHT baseline sample for each treatment group prior to comparison between different treatment groups. Growth rate measurements from viable cell counts were compared between different treatment groups using the SLOPE function in Excel. Response of cells with or without test treatment for all endpoints was compared using 2-tailed Student’s t test.

To compare the functional impact of treatment with single XEs or XE mixture upon the “untreated baseline” state of nonmalignant breast epithelial cells, we determined the lowest concentration at which cells displayed a “half baseline effect” (HBE) or “double baseline effect” (DBE) for a specific endpoint. Using a linear mixed effects model (lme), we computed a slope and intercept from the data derived from 3 test concentrations and no treatment for each test cell line and each metric. This data allowed us to mathematically estimate the point at which the XE effect is 50% or 200% of the baseline for a given cellular endpoint. In this model, we used Stata (version 12) to estimate the coefficients of the equation:

where Yij is the log of the relative response for the ith treatment at concentration j, Ii is an indicator for the ith treatment, dij is the log of the concentration for the ith treatment at concentration j, b1j is a random effect at concentration j and eij is a random error term. HBE or DBE was then estimated for each treatment from the equation:

Tests for synergy were facilitated through the use of the lincom command in Stata. For each of the 5 test endpoints, data analysis was based on 6 experimental runs representing 3 nonmalignant HRBEC lines, and 6 runs for breast cancer cell lines (4 for ER-positive, and 2 for ER-negative). Relative values were calculated as the MFI of test sample divided by the untreated control value.

RESULTS

To study the induction of characteristic breast cancer associated phenotypes from exposure to known estrogenic chemicals, individually and as mixtures, we used a model of HRBECs collected as RPFNA from the nonmalignant breast tissue of volunteers (Dairkee et al., 2008). Three previously developed spontaneously immortalized ER-positive HRBEC lines isolated from among 100 processed samples (Dairkee et al., 2013; Goodson et al., 2011; Luciani-Torres et al., 2015) were employed to generate comprehensive data encompassing multiple treatments, concentrations, and endpoints related to the effects of the test mixture on nonmalignant breast epithelium. Key findings were subsequently confirmed in primary finite-life HRBEC cultures.

We selected experimental XE exposures in this study based on the known range of single components of the ternary test mixture within human body fluids (Table 1). Our low and intermediate test concentrations for BPA(1 and 10 nM), MP (10 and 100 nM), and PFOA (1 and 10 nM) both singly and as a mixture are within the environmentally relevant concentration range. Additionally, effects of chemicals at a 10-fold higher exposure level were also studied. Response profiles to single XEs and to ternary mixtures of the XEs were thus compared at 3 log10 increasing concentrations, ranging from 1 to 100 nM (or 10 nM to 1 µM) depending on the abundance of the test chemical in human tissues and body fluids. Tests of the natural estrogen 17β-estradiol (E2) were included in all exposure panels to ascertain estrogen responsiveness within each test model.

The impact of single XE and mixture exposure upon test cells was studied as a continuum of cellular changes associated with aberrant estrogenic signaling, characteristic of clinical breast cancer. First, we measured treatment effects upon total ERα, ERα phosphorylated at serine residue 118 (pERαS118), and ERβ. The contrasting roles of ERα and ERβ in cell cycle regulation are well known. Additionally, phosphorylation of ERα at serine-118 directly activates ERα resulting in the regulation of genes harboring an estrogen response element in their promoters (Kato et al., 1995), including cell cycle genes, and thereby serving as a relevant study endpoint. Subsequently, the direct downstream consequences of such effects were assayed as: (1) the S-phase fraction of the cell cycle, and (2) the proportion of cells that evaded OHT-induced apoptosis.

Data derived from paired comparisons of treated and untreated nonmalignant HRBEC lines and primary cultures, as well as the breast cancer cell lines—MCF7 and T47D (ER-positive), and MDA231 (ER-negative), are detailed below:

Differential Effects of XE Mixtures on Malignant Versus Nonmalignant Breast Epithelial Cells

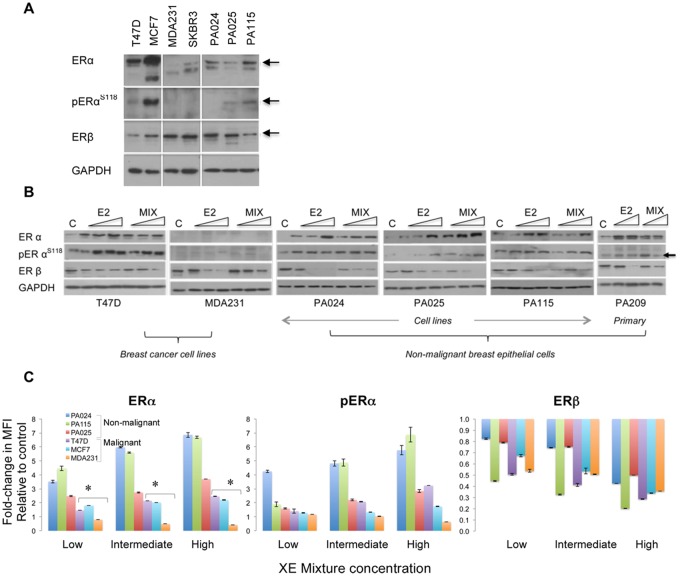

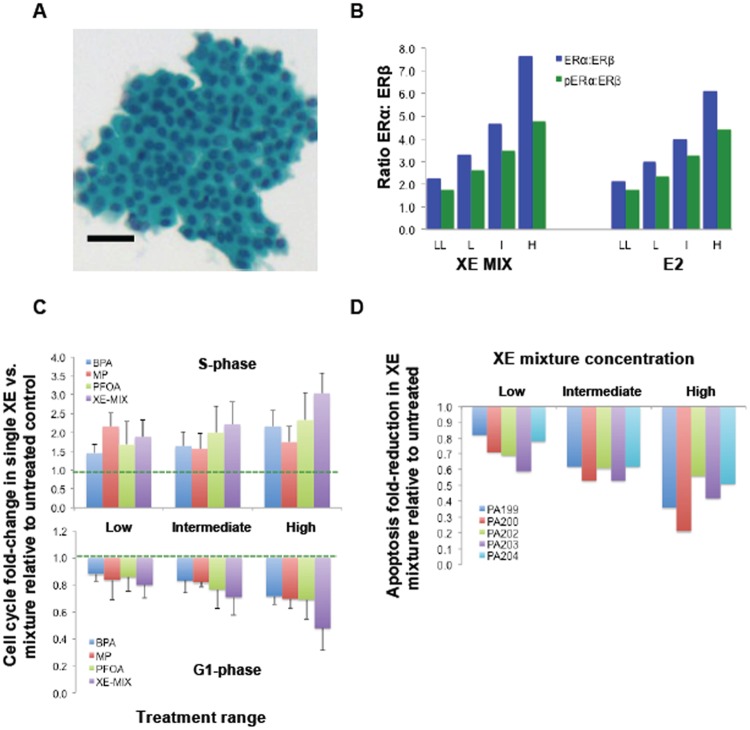

Under growth conditions optimized in our laboratory, HRBEC cultures consistently expressed both ER isoforms. As measured by western blot analysis, expression levels observed for both ERα and ERβ were moderate in comparison to breast cancer cell lines (Figure 1A) . Seven-day exposures to increasing concentrations of the test ternary XE mixture (BPA + MP + PFOA) or to E2, resulted in the induction of total ERα, as well as pERαS118, whereas ERβ levels steadily declined within the same cell lysate (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Relative range of cellular perturbations in malignant and nonmalignant breast epithelial cells treated with a mixture of 3 high-consumer use chemicals. A, Baseline levels of ERα and ERβ isoforms shown as representative western blots. Commonly used ERα-positive and ERα-negative breast cancer cell lines are included as controls to compare relative expression levels of each isoform. pERα is designated as pERαS118. GAPDH is the protein loading control accompanying the sample run. When compared with ERα overexpression in ER-positive breast cancer cell lines, HRBECs maintain moderate to low receptor levels. In panels (A) and (B), each subpanel without vertical separation lines represents adjacent samples processed in parallel within the same gel/blot. Horizontal lines within lanes represent discontinuous areas probed with primary antibodies to indicated proteins. B, Concentration-dependent modulation of ER isoform levels in protein lysates of cells treated with 3 increasing concentrations of the test mixture or E2. The primary culture, PA209 was treated with the 2 higher concentrations. Untreated control is denoted as C. Note concentration-dependent induction of ERα in all ER-positive cells but not in ER-negative MDA231 cells. Concurrently, ERβ is reduced by E2 as well as XE mixture treatment in all test cells. C, Quantitation of ERα, pERαS118, and ERβ by multiplexed FACS measurements of fixed whole cells exposed to increasing XE mixture concentration - low (1 nM BPA +1 nM PFOA +10 nM MP), intermediate (10 nM BPA +10 nM PFOA +100 nM MP), and high (100 nM BPA +100 nM PFOA +1 µM MP). Each data point represents 2–4 replicates. As denoted by asterisks, ERα induction in nonmalignant HRBECs (PA024, PA025, PA115) compared with breast cancer cell lines is statistically significant (t test—p ≤ .05). pERαS118 levels in 2/3 mixture-treated HRBEC lines are significantly higher than others. Reduction of ERβ at low mixture concentration relative to untreated control is more pronounced in malignant cells.

XE-induced, concentration-dependent shifts in ER isoform levels were quantitated in fixed whole cell assays as well. Measurements of ER content in protein lysates, resolved by gel electrophoresis, were confirmed by FACS analysis of cells exposed to identical conditions. A multiplex assay was optimized and used for simultaneous quantitation of all 3 ER-based endpoints within the same cells (Figure 1C). In both types of assays—lysate and whole cell—nonmalignant HRBECs displayed greater ERα induction than cancer cell lines, ie, the nonmalignant cells were more sensitive than cancer cell lines as a group (p < .05). pERαS118 protein levels closely paralleled the increase in total ERα content of cells, indicating the functional potential of ERα protein in XE-treated cells to induce downstream mitogenic signaling. As expected, induction of ERα or pERαS118 was not observed in the ER-negative breast cancer cell line, MDA231. All lines, including ER-negative breast cancer cell lines treated with the XE mixture displayed a reduction in ERβ levels. As a result, the ratio of the receptors shifted to favor ERα in ER-positive cells. Notably, this shift was more striking in nonmalignant HRBECs exposed to low XE mixture concentration than in cancer cells.

Cellular Response Profiles of Exposure to XE Mixture Versus Single Components

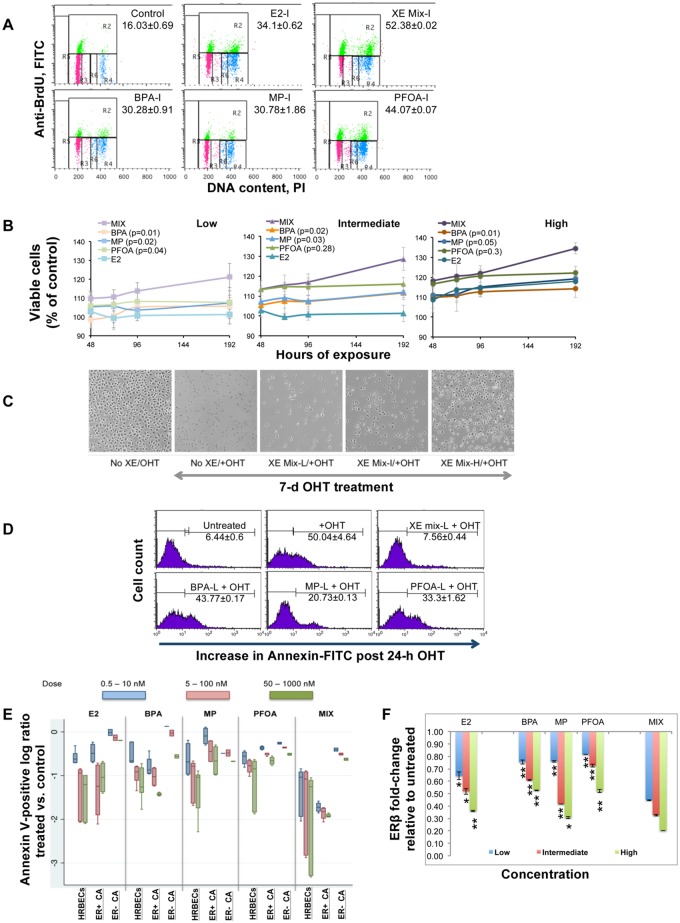

To evaluate XE mixture-mediated downstream mitogenic induction resulting from altered estrogenic signaling, changes in population doubling were measured as the S-phase fraction of the cell cycle. As shown in representative HRBECs (PA115) treated with the intermediate concentration of all test chemicals, percent S-phase (Figure 2A) in XE mixture-exposed cells was significantly greater (52.3% ±0.02%) compared with individual treatment with BPA (30.2% ± 0.9%), MP (30.7% ± 1.8%), or PFOA (44% ± 0.07%). The proportion of S-phase cells was higher in HRBECs at all test concentrations of the mixture relative to single XEs. Differences between the effects of mixture and single XEs or E2 were statistically significant for this endpoint at the 2 higher concentrations tested (p < .001).

Figure 2.

Comparative effects of exposure to XE mixture vs. single components A, Cell cycle analysis measured by BrdU incorporation into DNA. FACS dot plots of representative HRBECs showing effects of treatment with single XEs or XE mixture at the intermediate (I) test concentration, a value that falls within the reported range of individual XEs detected in human body fluids. X-axis represents total DNA stained with PI. Y-axis represents BrdU-positive fraction. Values indicate percent S-phase (top—gate R2). Other phases of the cell cycle are also depicted as G1 (bottom left—gate R3) and G2M (bottom right—gate R4/R6). Each value represents 2–4 data points. Mixture induced S-phase increase relative to single XEs or E2 treatment is statistically significant (2-tailed p value < .001). B, A relative increase in the number of viable HRBECs in the presence of single XEs or XE mixture at low (BPA, PFOA—1 nM; MP—10 nM; XE mixture—1 nM BPA +1 nM PFOA +10 nM MP), intermediate (BPA, PFOA—10 nM; MP—100 nM; XE mixture—10 nM BPA +10 nM PFOA +100 nM MP), or high (BPA, PFOA—100 nM; MP—1 µM; XE mixture—100 nM BPA +100 nM PFOA +1 µM MP) concentrations, was measured over time (8-day treatment period) as relative fluorescence units of the PrestoBlue reagent. E2 treatment was included as a positive control. Each data point is an average of 6 replicates. A comparison of the slope b of each line in the plot for all 3 test concentrations shows a uniformly higher slope for mixture-treated cells compared with individual chemicals. Consistent with the higher b value, XE mixture treatment results in a significantly faster cell proliferation rate compared with single XEs at similar concentrations. The p-values of 2-tailed t tests comparing single XE and mixture are shown in each graph legend in parentheses.

Increases in cells entering S-phase resulted in higher total cell numbers over time indicating that cell populations captured at S-phase do indeed complete the cell cycle. Consequently, a greater differential was observed between total cell numbers in mixture-treated versus single XE-treated cultures. As evident from the slope of the growth curves of representative HRBECs (Figure 2B) exposed to increasing concentrations of XEs, treatment at all XE mixture concentrations resulted in a cell proliferation rate 40%–70% faster than the comparable single XE concentration. Even at the lowest treatment concentration, a statistically significant difference was observed ranging from a 30%–90% increase over time in the cellular growth rate in mixture-treated relative to single XE-treated cells (p < .05).

In contrast to the cell proliferation endpoint, exposure to increasing concentrations of the XE mixture had the opposite effect on the efficiency of OHT-induced programed cell death or apoptosis. Mixture-exposed HRBECs persisted in culture subsequent to a long duration of OHT treatment (Figure 2C). The Annexin V-stained fraction of apoptotic cells was consistently lower in HRBECs exposed to the ternary mixture compared with single XEs. For example, OHT-induced apoptosis declined over 3- to 6-fold in mixture-treated HRBECs relative to single XE treatment (Figure 2D). A comparison of Annexin V-positive data points across all treatments and test cells (Figure 2E) showed a minimal shift between treated and control ER-negative cell lines. However, in a concentration-based comparison between the effects of single XEs and the mixture upon malignant and nonmalignant ER-positive cells, the highest number of cells evading apoptosis was observed in mixture-treated HRBECs. Breast cancer cell lines were similar to HRBECs for single XE response, but less sensitive than HRBECs for mixture mediated apoptosis evasion.

A comparison between the impact of single XEs and the mixture on the 2 ER isoforms showed that at even the lowest concentration of the test mixture, total ERβ was reduced to less than half the baseline control level (representative HRBECs, Figure 2F), which was significantly lower than the effect of any single chemical tested at that concentration (p < .001). As a result, the normal ratio of the 2 ER isoforms was detectably perturbed.

Altogether, based on multiple assays and cellular endpoints illustrated in Figure 2, mixture treatment had a consistently higher impact than exposure to the same chemicals individually.

XE Mixture Potency Related to Test Cell Type and Test Endpoint

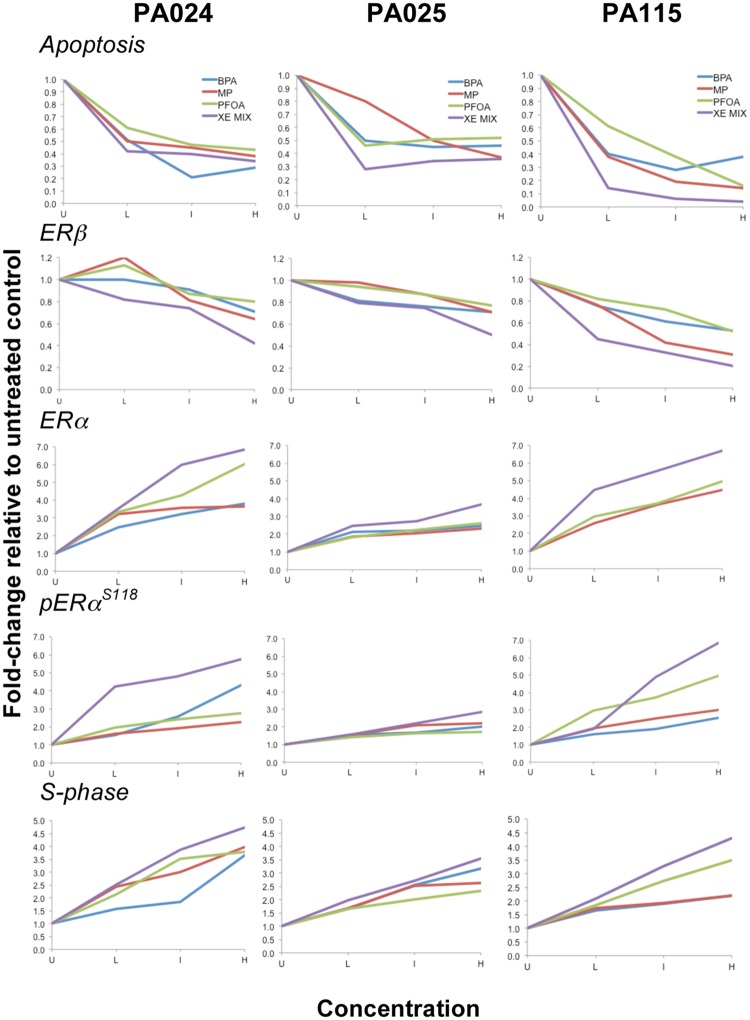

Finally, we evaluated the relationship between the concentration of each chemical and 5 specific cellular responses or endpoints. For each response we had 4 data points, the condition without chemicals and 3 concentrations known to be relevant to human exposure (Table 1). Individual plots of experimental values for all nonmalignant test samples (Figure 3) displayed variable outcomes as would be expected of each test cell line representing a different human donor. Regardless, the deviation from untreated control baseline for each of the 5 test endpoints is greater for the mixture than for any of the single XE components. Similar plots of breast cancer cell lines displayed minimal differences between single XEs and the XE mixture (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3.

HRBECS at human-relevant concentrations of XEs are affected more by the mixture than individual chemicals. Concentration-dependent plots comparing the ratio of none and 3, log10 ratio concentrations of XEs in 3 ER-positive nonmalignant breast cell lines for 5 test endpoints. Concentrations are denoted by U (untreated) L (Low: BPA, PFOA—1 nM; MP—10 nM; XE mixture—1 nM BPA +1 nM PFOA +10 nM MP), I (Intermediate: BPA, PFOA—10 nM; MP—100 nM; XE mixture—10 nM BPA +10 nM PFOA +100 nM MP), or H (High: BPA, PFOA—100 nM; MP—1 µM; XE mixture—100 nM BPA +100 nM PFOA +1 µM MP). The XE mixture effect (purple lines) is greater than any one of the individual XEs for all endpoints in all cases. Further analysis of this data is detailed in Figure 4. Data from these and breast cancer cell lines are shown for comparison in Supplementary Figure 2.

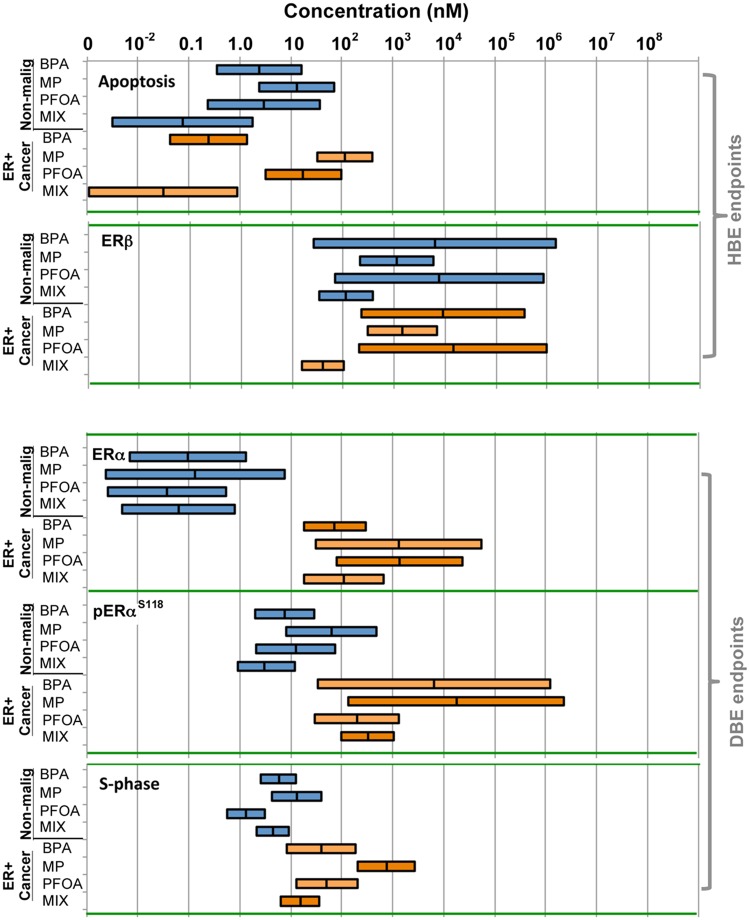

The above-mentioned data generated for all test endpoints (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 2) was used to calculate concentrations at which cells displayed a “HBE” or “DBE” for all treatment conditions using the lme model. This model determined the extent to which single or mixture treatment concentrations, expressed as log concentrations, affect a given cellular endpoint relative to the baseline (no chemicals) in the 2 major ER-positive test cell groupings—malignant and nonmalignant. Represented graphically (Figure 4), these plots illustrate the impact of a chemical mixture versus its single components upon each test endpoint across sets of test cells, and as such are a useful tool for assessing the interactions of the chemicals in the mixture across a broad concentration range. For example, in comparing treatments across nonmalignant HRBECs as a group for the apoptosis evasion endpoint, the calculated mean HBE for single XEs ranges from 4 to 11 nM, whereas that for the XE mixture is 0.09 nM. In other words, a 44- to 122-fold lower concentration of the XE mixture is sufficient to elicit the same adverse cellular effect imparted by exposure to each of the 3 XE components individually. Such a marked reduction in the HBE concentration for the mixture for this endpoint indicates a synergistic effect of the chemicals when present simultaneously within the test cells. If, alternatively, each of the 3 components of the mixture was equipotent, thereby contributing one-third of an additive adverse effect related to apoptosis evasion, the predicted HBE of the mixture would be 6.2 nM, a 68-fold higher value than portrayed by the analysis of our experimental results. A similar synergistic impact of chemicals was displayed by analysis of the XE mixture effects on the ERβ endpoint in both malignant and nonmalignant breast cells.

Figure 4.

Estimation of HBE and DBE levels of mixture versus single XEs—Plots based on cumulative response data for single XEs and ternary mixtures derived from 3 nonmalignant HRBECs and 2 ER-positive breast cancer cell lines for 5 independent cellular endpoints. The length of each horizontal bar represents the 95% CI for computing relative effects in the designated cell line group for a specific treatment and endpoint combination. For endpoints that were decreased in value by XE exposure relative to untreated controls (apoptosis and ERβ), the midpoint mark within the bar is the estimated HBE concentration where the endpoint is reduced to 50% of untreated control maximum. For endpoints where XE exposure led to an increased value relative to untreated controls (ERα, pERαS118, and S-phase), the midpoint mark within the bar is the DBE, an estimated concentration where the measured effect is double that of untreated control maximum. Within the collective data shown for each endpoint and cell group, a synergistic effect of the mixture is depicted wherever the HBE or DBE of the mixture bar does not overlap the HBE or DBE of the bar of any single chemical component, ie, mixture effects on apoptosis and ERβ in nonmalignant HRBECs, and on ERβ and S-phase in malignant cell lines.

The HBE and DBE statistics summarized in Table 2 confirm key differences between the sensitivity of HRBECs and breast cancer cell lines to the XE mixture: (1) for total ERα induction, HRBECs were stimulated at a significantly lower mixture concentration than cancer cells (0.08 vs. 131.8 nM), (2) pERαS118 induction occurred at a significantly lower concentration in HRBECs than in cancer cells (3.62 vs. 388.31 nM), (3) in contrast to ERα perturbation, total ERβ reduction for HRBECs required slightly higher exposures (134.64 vs. 47.77 nM), and (4) S-phase induction occurred at a lower concentration in HRBECs (5.36 vs. 18.16 nM). Similarly, despite variability in the magnitude of response between samples, HRBECs as a group displayed greater sensitivity to E2 compared with ER-positive breast cancer cell lines for 5/5 endpoints. The mean values shown for E2 exposure in Table 2 are derived from a parallel estimation of HBE and DBE (not incorporated into Figure 4) based on data displayed in multiple panels of Figures 1–3. The molecular basis for our findings related to the enhancement of estrogenic signaling by XE mixture treatment of nonmalignant HRBECs leading to ERα expression, S-phase induction, and apoptosis evasion at low concentrations closely approximating natural estradiol levels of induction, presently remains unknown. However, it could be speculated that a synergistic combination of ER agonists simultaneously occupy available receptor sites with varying binding affinities thereby more effectively sustaining ER-regulated gene expression manifested as the functional endpoints used here, instead of limited effects from a transient spike of receptor activity that likely occurs in the presence of single XEs at similar low concentrations.

Table 2.

A Comparison of XE Mixture and E2 Exposure-Derived Estimates of Relative HBE and DBE in ER-Positive Human Breast Epithelial Cells

| Treatment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XE mixture |

E2 |

|||

| Test cells | Nonmalignant | Breast cancer | Nonmalignant | Breast cancer |

| Endpoints | ||||

| HBE (nM)a | ||||

| Apoptosis evasion | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.57 | 1.04 |

| ERβ reduction | 134.64 | 47.77 | 16.18 | 23.39 |

| DBE (nM)b | ||||

| ERα induction | 0.08 | 131.58 | 1.41 | 5.61 |

| pERαS118 induction | 3.62 | 388.31 | 4.77 | 27.48 |

| S-phase increase | 5.36 | 18.16 | 1.95 | 6.59 |

HBE—relative inhibitory concentration resulting in endpoint reduction to half of baseline.

DBE—relative stimulatory concentration resulting in endpoint induction to double of baseline.

Notably, estimated HBE and DBE values for the test chemicals fall mostly within the actual experimental concentration range used (Table 1). As shown in Table 2, compared with nonmalignant breast cells, ER-positive breast cancer cells require relatively higher concentrations of XE mixture or E2 to induce and activate ERα expression, and downstream stimulation of cells to enter the S-phase of the cell cycle. In agreement with our findings, tests conducted in cancer cells report weak estrogenicity of single XEs used here (Henry and Fair, 2013; Kim et al., 2001; Okubo et al., 2001). More importantly, we demonstrate that nonmalignant HRBECs are more sensitive than cancer cells to both XE mixture and E2 for all endpoints (with the exception of ERβ suppression). The differential response of malignant and nonmalignant breast cells to XE mixture and/or E2 might be related to differences in the ligand-receptor interaction. Studies of the ERα conformational state have shown that while the wild type receptor (expectedly present in normal cells) displays an open pocket state for the binding and release of ligand, in an aberrant receptor conformation, a closed pocket state is observed even when unoccupied by ligand, thus accounting for constitutive receptor activity (Carlson et al., 1997), generally found in cancer cells. The striking differences consistently observed in the response to natural and synthetic estrogens between malignant and nonmalignant cells across multiple endpoints underscore the importance of including tests of nonmalignant cells in chemical safety screens.

Validation of XE Mixture Induced Perturbations in Primary HRBECs

To evaluate mixture-related effects directly upon freshly isolated human breast cells, data were generated from cytopathologically confirmed nonmalignant primary HRBECs derived from multiple volunteers under closely similar experimental conditions (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 1). Even though relatively low cell yields from such finite lifespan HRBECs, coupled with limitations of assay sensitivity, restricted the feasibility of evaluating the breadth of treatments and functional endpoints within a single FNA sample, all observations made in cell lines were validated with cells from 11 independent donors so that the number of subjects tested offset the limited data acquisition potential from a single test sample.

Figure 5.

Mixture-induced effects displayed by primary nonimmortalized HRBECs. A, Micrograph of an H&E-stained FNA smear illustrates benign cytopathology of a representative sample (PA200) prior to primary cell culture. Bar—50 µm. This, and additional FNA samples used for analysis of mixture effects are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. B, Relative effects of XE mixture on ERα: ERβ and pERαS118: ERβ ratios in primary HRBECs. Average ratios from 7 independent volunteers shown are based on individual values for ERα, pERαS118, and ERβ levels. Similar to HRBECs in Figures 1 and 3, ERα, and pERαS118 were increased, and ERβ levels were decreased by the treatment. Similar to the effects of E2 in these cells, note XE-mixture induced concentration-dependent shifts in the ratio of the 2 isoforms favoring ERα levels. XE mixture concentrations represent: LL (0.1 nM BPA +0.1 nM PFOA +1 nM MP), L (1 nM BPA +1 nM PFOA +10 nM MP), I (10 nM BPA +10 nM PFOA +100 nM MP), and H (100 nM BPA +100 nM PFOA +1 µM MP). The E2 concentration range is: LL (0.5 nM), L (5 nM), I (50 nM), and H (500 nM). For both XE mixture and E2 treatment, the increase in ratio between the 2 lower and 2 higher concentrations is statistically significant (p < .01). C, Mixture versus single XE-induced increase in S-phase fraction (top panel), and decrease in G1 fraction (bottom panel). Dashed lines represent S-phase and G1-phase for control unexposed cells as a reference point for the extent of endpoint shift in XE-treated cells. Plots represent average values derived from 7 independent human volunteer samples analyzed at passage 2. Despite inter sample variability, concentration-dependent fold-change in S-phase induction and G1 reduction is evident at the intermediate and high XE mixture treatment compared with single XEs. D, Evasion of apoptosis (induced by 24-h OHT treatment) in 5 independent primary HRBEC samples at passage 2. Note concentration-dependent decline in the apoptotic cell fraction in each donor cell sample treated with the XE mixture.

The observed changes in ER isoform ratio displayed by HRBEC lines were confirmed in primary HRBEC cultures derived from 7 volunteer samples, PA203, PA209, PA217, PA218, PA219, PA221, and PA222 (Figure 5B). A concentration-dependent association was observed between mixture treatment and ER isoform modulation, ie, ERα or pERαS118 induction and ERβ reduction in the test samples. The range of ratio modulation of XE mixture-treated primary HRBECs was closely similar to those exposed to E2.

Relative to single agents, mixture-induced increase in S-phase and concurrent decrease in G1-phase of the cell cycle observed in malignant and nonmalignant breast epithelial cell lines, was confirmed in primary HRBEC cultures derived from 5 independent subjects: PA199, PA200, PA202, PA203, and PA209. The S-phase fraction of HRBECs from different individuals increased between 0.3- to 2.4-fold at the lowest mixture concentration relative to untreated control. Due to intersample variability between the 5 test samples, S-phase increase in mixture-treated cells although generally greater than single chemical treatment at the same concentration, did not reach statistical significance. Similarly, a trend suggesting a greater mixture effect for a declining G1 fraction of the cell cycle was observed in primary HRBECs (Figure 5C).

Mixture-induced apoptosis evasion observed in malignant and nonmalignant breast epithelial cell lines, was also displayed to varying degrees by primary HRBECs derived consecutively from 5 independent subjects, PA199, PA200, PA202, PA203, and PA204. A concentration-dependent association with exposure to the XE mixture was evident for this endpoint (Figure 5D). An average of 42% ± 9% and 59% ± 14% reduction in apoptosis was observed in cells treated with intermediate and high mixture concentrations, respectively, relative to untreated control. In the presence of high concentration single XEs, apoptosis evasion in these cells was <30% of the level observed in the XE mixture at that concentration.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we use nonmalignant human breast cells to demonstrate that XEs (in concentrations found in human body fluids) cause more key pathway perturbations as a mixture than as individual XEs. Such biological effects of chemical mixtures—as opposed to the effects of individual chemicals—have been a matter of concern for over 2 decades (Kaiser, 1996; Simons, 1996). Recent reviews have predicted additive and/or synergistic effects of low-dose chemical mixtures (Goodson et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2017). Continuing reports directed at a wide variety of model systems and endpoints including cellular gap junctions (Kang et al., 1996), yeast reporter assay (Silva et al., 2002), rat uterotrophic assay (Charles et al., 2007), and mouse embryonic stem cells (Zhou et al., 2017) have served to demonstrate additive or synergistic effects of estrogenic chemical mixtures. In terms of the relevance of such mixtures to the breast, in vitro treatment of the breast cancer cell line—MCF7 with 3 and 4 component XE mixtures (Soto et al., 1997), suggested synergistic effects based on the single endpoint of cell proliferation as a hallmark of estrogen action. Similarly, Charles and Darbre (2013) reported that parabens detected in human tissue stimulated greater growth of MCF7 cells when administered as a reconstituted mixture than as individual chemicals at the same concentrations. Synergism or antagonism between specific estrogenic chemicals in such cells was shown to be restricted to certain dose combinations (Suzuki et al., 2001).

Our study advances findings related to estrogenic chemicals by demonstrating perturbations in estrogen responsive benign human breast epithelial cells induced by a ternary mixture of structurally dissimilar chemicals of commerce, sufficiently widespread in the environment that even at low concentrations their combined effects are likely to be clinically relevant. Cell culture studies are generally limited to single cell lines, and to our knowledge, treatments extending across a panel of independent live cell models of human tissue, as presented here, are nonexistent. Moreover, multiple endpoints are rarely assayed simultaneously in tests of potential carcinogenic chemicals and their mixtures. As a result, there is a dearth of data on comparability between the response of multiple test samples, and the relative sensitivity of independent in vitro tests. Here, we measured 5 endpoints relevant to human cancer. (1). Increased S-phase: Higher S-phase estimates in malignant compared with benign tissues, is well established (Christov et al., 1991, 1994). In premenopausal women, a high proliferation index in benign breast tissue predicts future development of invasive breast cancer in the same patient (Huh et al., 2016), (2) Increased ERα: Higher ER levels in benign breast tissue have long been known in proliferative fibrocystic condition (Jacquemier et al., 1982), and more recently they have been correlated with future breast cancer risk (Posso et al., 2017). Measurable ERα levels correlate directly with breast cancer risk factors such as obesity and alcohol consumption, and inversely with nursing, a protective factor (Oh et al., 2017). (3) ERα activation: Several phosphorylation sites are reported within ERα, which are involved in the regulation of receptor-mediated signaling (reviewed in Anbalagan and Rowan, 2015). ERα phosphorylated at serine 118 (S118) in the Activation function-1 domain localizes preferentially at promoters of ER responsive genes (Weitsman et al., 2006). This binding is critical for increased cell growth and resistance to apoptotic cell death (Huderson et al., 2012), supporting the hypothesis that activation at this key phosphorylation site is a potential surrogate for a functional ERα signaling pathway in breast cancer. (4) Apoptosis evasion: Well recognized as a characteristic of cancer cells, induction of apoptotic cell death is a common objective of all forms of cancer treatment, i.e. radiation, chemotherapy, and hormone based therapy. In rodent models, loss of apoptotic cell death occurs in the progression to malignancy (Shilkaitis et al., 2000), and predicts tumor aggressiveness (Sierra et al., 1996). Age-related lobule involution, an apoptotic process, is inversely related to the occurrence of breast cancer (Milanese et al., 2006). (5) Decreased ERβ: ERβ modulates the effects of ERα by suppressing cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in xenograft models (Helguero, 2005; Paruthiyil et al., 2004). In women, ERβ protein (Roger et al., 2001) and ERβ mRNA levels (Park et al., 2003) decrease during the progression from benign to ductal carcinoma-in situ, or benign to nodal metastases, respectively. In ERα-positive cancers, presence of ERβ is associated with better survival (Maehle, 2009), while lower ERβ levels in benign breast disease predict subsequent cancer risk (Shaaban et al., 2003).

Perturbations induced by BPA, MP, and PFOA in the above-mentioned endpoints correspond to 3 “Hallmarks” or common traits of cancer as a disease (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011), ie, increased proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and overriding normal cell control mechanisms through effects on the ER (increased total and activated ERα, and decreased ERβ). Additionally, these chemicals exhibit 2 of the 10 “Key Characteristic” abilities shared among carcinogens (Smith et al., 2016), ie, they “modulate receptor-mediated effects” (through ERα and β signaling) and “alter cell proliferation [and] cell death…” (through increased S-phase and total cell number, and decreased apoptosis and the G1 fraction of the cell cycle). As defined through the analysis of an extensive framework of mechanistic studies of known carcinogenic chemicals, a carcinogen will exhibit at least 1 key characteristic (Smith et al., 2016). Any identified characteristic is therefore a cause for concern even before the mechanism of action is known, and as such could play an important role in guiding regulatory decisions.

We confirmed that the direction of pathway toxicity for each endpoint shown in Figure 4 is consistent and repeatable with fresh samples from additional subjects. Unlike repetitive testing on one cell line—which it is hoped will have internal consistency because the cells are indistinguishable at the outset—our paradigm tests chemical exposures on unrelated nonmalignant samples derived from multiple individuals (Supplementary Figure 1). An effect demonstrated across such samples is more likely to be a universal phenomenon, reducing the risk of being misled by results unique to an individual cell line. Altogether, our data support the conclusion that since chemicals interact jointly with the cellular machinery, their toxicity is undetermined until adequately tested as a component of a mixture to which humans are regularly exposed.

To seek exposure levels of chemicals and chemical mixtures that could be biologically harmful, we calculated an HBE level (the concentration that reduced a cellular endpoint to 50 percent of untreated baseline value) or the DBE level (the concentration that increased a cellular endpoint to 200 percent of untreated baseline value) across ER-positive malignant and nonmalignant cell lines. This analysis specifically aims to determine the concentration level at which an adverse effect of a given exposure will likely occur in any at-risk cell. The most striking implication of the data plotted in Figure 4 is that some endpoints are more readily perturbed in benign cells than in malignant cells. For example, total ERα and pERα induction are approximately 1000-fold and 100-fold more sensitive, respectively, to XE exposure. This explains why testing of malignant cell lines can miss important events. For other processes, ie, evasion of apoptosis and suppression of ERβ, it is evident that the effects are synergistic in both benign and malignant cells, confirming that the mixture is widely effective at a significantly lower concentration than single chemicals. Considering that a chemical might intensify the effects of another chemical, merely noting their effects individually does not inform the joint impact of chemicals upon cellular pathways and consequently the safe level of exposure to such ubiquitous mixtures that populations are exposed to daily. Equally important is an understanding of the biological consequences of mixtures of common XEs and antiestrogens. As previously demonstrated, simultaneous exposure to low equimolar concentrations of BPA and curcumin—a natural polyphenol that suppresses ERα expression, effectively neutralizes the impact of BPA exposure (Dairkee et al., 2013). In this light, expanding the emphasis from single chemical screening to real world scenarios of exposure is a critical need, particularly as consumers are confronted with an ever-increasing chemical content in daily use products.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the California Breast Cancer Research Program (17UB-8702) and by the Clarence E. Heller Charitable Foundation.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Anbalagan M., Rowan B. G. (2015). Estrogen receptor alpha phosphorylation and its functional impact in human breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 418, 264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artacho-Cordón F., Arrebola J. P., Nielsen O., Hernández P., Skakkebaek N. E., Fernández M. F., Andersson A. M., Olea N., Frederiksen H. (2017). Assumed non-persistent environmental chemicals in human adipose tissue; matrix stability and correlation with levels measured in urine and serum. Environ. Res. 156, 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesoon S., Webster G. M., Shoeib M., Harner T., Benskin J. P., Martin J. W. (2011). Isomer profiles of perfluorochemicals in matched maternal, cord, and house dust samples: Manufacturing sources and transplacental transfer. Environ.Health Perspect. 119, 1659–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson K. E., Choi I., Gee A., Katzenellenbogen B. S., Katzenellenbogen J. A. (1997). Altered ligand binding properties and enhanced stability of a constitutively active estrogen receptor: Evidence that an open pocket conformation is required for ligand interaction. Biochemistry 36, 14897–14905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). (2015). Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/pdf/fourthreport_updatedtables_feb2015.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2015.

- Cecchini M. J., Amiri M., Dick F. A. (2012). Analysis of cell cycle position in mammalian cells. J. Vis. Exp. 59, 3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles G. D., Gennings C., Tornesi B., Kan H. L., Zacharewski T. R., Bhaskar Gollapudi B., Carney E. W. (2007). Analysis of the interaction of phytoestrogens and synthetic chemicals: An in vitro/in vivo comparison. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 218, 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles A. K., Darbre P. D. (2013). Combinations of parabens at concentrations measured in human breast tissue can increase proliferation of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 33, 390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Yin S., Kelly B. C., Liu W. (2017). Isomer-specific transplacental transfer of perfluoroalkyl acids: Results from a survey of paired maternal, cord sera, and placentas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 5756–5763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christov K., Chew K. L., Ljung B. M., Waldman F. M., Duarte L. A., Goodson W. H. 3rd, Smith H. S., Mayall B. H. (1991). Proliferation of normal breast epithelial cells as shown by in vivo labeling with bromodeoxyuridine. Am. J. Pathol. 138, 1371–1377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christov K., Chew K. L., Ljung B. M., Waldman F. M., Goodson W. H. 3rd, Smith H. S., Mayall B. H. (1994). Cell proliferation in hyperplastic and in situ carcinoma lesions of the breast estimated by in vivo labeling with bromodeoxyuridine. J. Cell Biochem. Suppl. 19, 165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dairkee S. H., Seok J., Champion S., Sayeed A., Mindrinos M., Xiao W., Davis R. W., Goodson W. H. (2008). Bisphenol A induces a profile of tumor aggressiveness in high-risk cells from breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 68, 2076–2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dairkee S. H., Luciani-Torres M. G., Moore D. H., Goodson W. H. (2013). Bisphenol-A-induced inactivation of the p53 axis underlying deregulation of proliferation kinetics, and cell death in non-malignant human breast epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis 34, 703–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez S. V., Huang Y., Snider K. E., Zhou Y., Pogash T. J., Russo J. (2012). Expression and DNA methylation changes in human breast epithelial cells after bisphenol A exposure. Int. J. Oncol. 41, 369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández M. F., Arrebola J. P., Jiménez-Díaz I., Sáenz J. M., Molina-Molina J. M., Ballesteros O., Kortenkamp A., Olea N. (2016). Bisphenol A and other phenols in human placenta from children with cryptorchidism or hypospadias. Reprod. Toxicol. 59, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson W. H., Luciani M. G., Sayeed S. A., Jaffee I. M., Moore D. H., Dairkee S. H. (2011). Activation of the mTOR pathway by low levels of xenoestrogens in breast epithelial cells from high-risk women. Carcinogenesis 32, 1724–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson W. H., Lowe L., Carpenter D. O., Gilbertson M., Manaf Ali A., Lopez de Cerain Salsamendi A., Lasfar A., Camero A., Azqueta A., Amedei A., et al. (2015). Assessing the carcinogenic potential of low-dose exposures to chemical mixtures in the environment: The challenge ahead. Carcinogenesis 36, S254–S296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. (2017). Fourth Report on Human Biomonitoring of Environmental Chemicals in Canada. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/environmental-workplace-health/reports-publications/environmental-contaminants/fourth-report-human-biomonitoring-environmental-chemicals-canada.html

- Helguero L. A., Faulds M. H., Gustafsson J. A., Haldosén L. A. (2005). Estrogen receptors alfa (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta) differentially regulate proliferation and apoptosis of the normal murine mammary epithelial cell line HC11. Oncogene 24, 6605–6616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry N. D., Fair P. A. (2013). Comparison of in vitro cytotoxicity, estrogenicity and anti-estrogenicity of triclosan, perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid. J. Appl. Toxicol. 33, 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huderson B. P., Duplessis T. T., Williams C. C., Seger H. C., Marsden C. G., Pouey K. J., Hill S. M., Rowan B. G. (2012). Stable inhibition of specific estrogen receptor α (ERα) phosphorylation confers increased growth, migration/invasion, and disruption of estradiol signaling in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 153, 4144–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh S. J., Oh H., Peterson M. A., Almendro V., Hu R., Bowden M., Lis R. L., Cotter M. B., Loda M., Barry W. T., et al. (2016). The proliferative activity of mammary epithelial cells in normal tissue predicts breast cancer risk in premenopausal women. Cancer Res. 76, 1926–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemier J. D., Rolland P. H., Vague D., Lieutaud R., Spitalier J. M., Martin P. M. (1982). Relationships between steroid receptor and epithelial cell proliferation in benign fibrocystic disease of the breast. Cancer 49, 2534–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser J. (1996). Environmental estrogens. New yeast study finds strength in numbers. Science 272, 1418.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K. S., Wilson M. R., Hayashi T., Chang C. C., Trosko J. E. (1996). Inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication in normal human breast epithelial cells after treatment with pesticides, PCBs, and PBBs, alone or in mixtures. Environ. Health Perspect. 104, 192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. J., Hong Y. B., Yi Y. W., Cho C. H., Wang A., Bae I. (2013). Correlations between BRCA1 defect and environmental factors in the risk of breast cancer. J. Toxicol. Sci. 38, 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrman A., Ericson I., van Bavel B., Darnerud P. O., Aune M., Glynn A., Lignell S., Lindström G. (2007). Exposure of perfluorinated chemicals through lactation: Levels of matched human milk and serum and a temporal trend, 1996–2004, in Sweden. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 226–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S., Endoh H., Masuhiro Y., Kitamoto T., Uchiyama S., Sasaki H., Masushige S., Gotoh Y., Nishida E., Kawashima H., et al. (1995). Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science 270, 1491–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S., Han S. Y., Yoo S. D., Lee B. M., Park K. L. (2001). Potential estrogenic effects of bisphenol-A estimated by in vitro and in vivo combination assays. J. Toxicol. Sci. 26, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPensee E. W., LaPensee C. R., Fox S., Schwemberger S., Afton S., Ben-Jonathan N. (2010). Bisphenol A and estradiol are equipotent in antagonizing cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 290, 167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. C., Fisher M., Davis K., Arbuckle T. E., Sinha S. K. (2017). Identification of chemical mixtures to which Canadian pregnant women are exposed: The MIREC Study. Environ. Int. 99, 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciani-Torres M. G., Moore D. H., Goodson W. H., Dairkee S. H. (2015). Exposure to the polyester PET precursor—Terephthalic acid induces and perpetuates DNA damage-harboring non-malignant human breast cells. Carcinogenesis 36, 168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehle B. O., Collett K., Tretli S., Akslen L. A., Grotmol T. (2009). Estrogen receptor beta–an independent prognostic marker in estrogen receptor alpha and progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer?. APMIS 117, 644–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanese T. R., Hartmann L. C., Sellers T. A., Frost M. H., Vierkant R. A., Maloney S. D., Pankratz V. S., Degnim A. C., Vachon C. M., Reynolds C. A., et al. (2006). Age-related lobular involution and risk of breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98, 1600–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. F., Goodson W. H., Manjili M. H., Kleinstreuer N., Bisson W. H., Lowe L. (2017). Low-dose mixture hypothesis of carcinogenesis workshop: Scientific underpinnings and research recommendations. Environ. Health Perspect. 125, 163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H., Eliassen A. H., Beck A. H., Rosner B., Schnitt S. J., Collins L. C., Connolly J. L., Montaser-Kouhsari L., Willett W. C., Tamimi R. M. (2017). Breast cancer risk factors in relation to estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, insulin-like growth factor-1, and Ki67 expression in normal breast tissue. NPJ Breast Cancer 3, 39.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo T., Yokoyama Y., Kano K., Kano I. (2001). ER-dependent estrogenic activity of parabens assessed by proliferation of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells and expression of ERalpha and PR. Food Chem Toxicol. 39, 1225–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B. W., Kim K. S., Heo M. K., Ko S. S., Hong S. W., Yang W. I., Kim J. H., Kim G. E., Lee K. S. (2003). Expression of estrogen receptor-beta in normal mammary and tumor tissues: Is it protective in breast carcinogenesis? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 80, 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paruthiyil S., Parmar H., Kerekatte V., Cunha G. R., Firestone G. L., Leitman D. C. (2004). Estrogen receptor beta inhibits human breast cancer cell proliferation and tumor formation by causing a G2 cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 64, 423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Barriuso R., Fernández M. F., Castaño-Vinyals G., Whelan D., Pérez-Gómez B., Llorca J., Villanueva C. M., Guevara M., Molina-Molina J. M., Artacho-Cordón F., et al. (2016). Total effective xenoestrogen burden in serum samples and risk for breast cancer in a population-based multicase-control study in Spain. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 1575–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer D., Chung Y. M., Hu M. C. (2015). Effects of low-dose bisphenol a on dna damage and proliferation of breast cells: The Role of c-Myc. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 1271–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posso M., Corominas J. M., Serrano L., Román M., Torá-Rocamora I., Domingo L., Romero A., Quintana M. J., Vernet-Tomas M., Baré M., et al. (2017). Biomarkers expression in benign breast diseases and risk of subsequent breast cancer: A case-control study. Cancer Med. 6, 1482–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger P., Sahla M. E., Mäkelä S., Gustafsson J. A., Baldet P., Rochefort H. (2001). Decreased expression of estrogen receptor beta protein in proliferative preinvasive mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 61, 2537–2541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer S. J., Tarpley M., Shah I., Save A. V., Lyerly H. K., Patierno S. R., Williams K. P., Devi G. R. (2017). Bisphenol A activates EGFR and ERK promoting proliferation, tumor spheroid formation and resistance to EGFR pathway inhibition in estrogen receptor-negative inflammatory breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 38, 252–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban A. M., O'Neill P. A., Davies M. P., Sibson R., West C. R., Smith P. H., Foster C. S. (2003). Declining estrogen receptor-ß expression defines malignant progression of human breast neoplasia. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 27, 1502–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar S., Sood S., Showkat S., Lite C., Chandrasekhar A., Vairamani M., Barathi S., Santosh W. (2017). Detection of phenolic endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) from maternal blood plasma and amniotic fluid in Indian population. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 241, 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilkaitis A., Green A., Steele V., Lubet R., Kelloff G., Christov K. (2000). Neoplastic transformation of mammary epithelial cells in rats is associated with decreased apoptotic cell death. Carcinogenesis 21, 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A., Castellsagué X., Tórtola S., Escobedo A., Lloveras B., Peinado M. A., Moreno A., Fabra A. (1996). Apoptosis loss and bcl-2 expression: Key determinants of lymph node metastases in T1 breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2, 1887–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva E., Rajapakse N., Kortenkamp A. (2002). Something for “nothing”—eight weak estrogenic chemicals combined at concentrations below NOEC’s produce significant mixture effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 1751–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons S. S., Jr. (1996). Environmental estrogens: Can two “alrights” make a wrong? Science 272, 1451.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. T., Guyton K. Z., Gibbons C. F., Fritz J. M., Portier C. J., Rusyn I., DeMarini D. M., Caldwell J. C., Kavlock R. J., Lambert P. F., et al. (2016). Key characteristics of carcinogens as a basis for organizing data on mechanisms of carcinogens. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 713–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto A. M., Sonnenschein C., Chung K. L., Fernandez M. F., Olea N., Serrano F. O. (1995). The E-SCREEN assay as a tool to identify estrogens: An update on estrogenic environmental pollutants. Environ. Health Perspect. 103, 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto A. M., Fernandez M. F., Luizzi M. F., Oles Karasko A. S., Sonnenschein C. (1997). Developing a marker of exposure to xenoestrogen mixtures in human serum. Environ .Health Perspect. 105, 647–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Ide K., Ishida M. (2001). Response of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells to some binary mixtures of oestrogenic compounds in-vitro. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 53, 1549–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinwell H., Ashby J. (2004). Sensitivity of the immature rat uterotrophic assay to mixtures of estrogens. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vela-Soria F., Gallardo-Torres M. E., Ballesteros O., Díaz C., Pérez J., Navalón A., Fernández M. F., Olea N. (2017). Assessment of parabens and ultraviolet filters in human placenta tissue by ultrasound-assisted extraction and ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1487, 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitsman G. E., Li L., Skliris G. P., Davie J. R., Ung K., Niu Y., Curtis-Snell L., Tomes L., Watson P. H., Murphy L. C. (2006). Estrogen receptor-alpha phosphorylated at Ser118 is present at the promoters of estrogen-regulated genes and is not altered due to HER-2 overexpression. Cancer Res. 66, 10162–10170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R., Cheng W., Feng Y., Wei H., Liang F., Wang Y. (2017). Interactions between three typical endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in binary mixtures exposure on myocardial differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cell. Chemosphere 178, 378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.