Abstract

The pesticides paraquat (PQ) and maneb (MB) have been described as environmental risk factors for Parkinson’s disease (PD), with mechanisms associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species generation. A combined exposure of PQ and MB in murine models and neuroblastoma cells has been utilized to further advance understanding of the PD phenotype. MB acts as a redox modulator through alkylation of protein thiols and has been previously characterized to inhibit complex III of the electron transport chain and uncouple the mitochondrial proton gradient. The purpose of this study was to analyze ATP-linked respiration and glycolysis in human neuroblastoma cells utilizing the Seahorse extracellular flux platform. Employing an acute, subtoxic exposure of MB, this investigation revealed a MB-mediated decrease in mitochondrial oxygen consumption at baseline and maximal respiration, with inhibition of ATP synthesis and coupling efficiency. Additionally, MB-treated cells showed an increase in nonmitochondrial respiration and proton leak. Further investigation into mitochondrial fuel flex revealed an elimination of fuel flexibility across all 3 major substrates, with a decrease in pyruvate capacity as well as glutamine dependency. Analyses of glycolytic function showed a substantial decrease in glycolytic acidification caused by lactic acid export. This inhibition of glycolytic parameters was also observed after titrating the MB dose as low as 6 μM, and appears to be dependent on the dithiocarbamate functional group, with manganese possibly potentiating the effect. Further studies into cellular ATP and NAD levels revealed a drastic decrease in cells treated with MB. In summary, MB significantly impacted both aerobic and anaerobic energy production; therefore, further characterization of MB’s effect on cellular energetics may provide insight into the specificity of PD to dopaminergic neurons.

Keywords: maneb, bioenergetics, glycolysis, ATP, mitochondrial dysfunction, Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative movement disorder described by a loss of dopaminergic neurons within the substantia nigra pars compacta of the brain (Thiruchelvam et al., 2000) and presence of protein aggregates called Lewy bodies (Zhang et al., 2003). Although genetic factors play a role in PD development, recent studies have shown prevalence of idiopathic PD, predominantly with environmental risk factors (Castello et al., 2007; Olanow and Tatton, 1999). Therefore, there has been extensive focus on the role of pesticides and other environmental exposures that potentiate PD, starting with the identification of multiple metals (such as Mn) and agricultural chemicals (Forno et al., 1986; Gorell et al., 1998; Rajput et al., 1987; Semchuk et al., 1992). Also, discovery of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 5, 6-tetrahydropyrine (MPTP), a process impurity created during the manufacturing of the synthetic opioid 1-methyl-4-phenyl-4-propionoxypiperidine (MPPP), has been studied due to its risk of PD pathology (Langston et al., 1984). Paraquat (PQ) has been similarly categorized due to its structural homology to the active metabolite of MPTP (Hertzman et al., 1990; Rajput et al., 1987). Additionally, the overlap of pesticide applications has led to the potential for “multi-hit” models for describing the complex mechanisms, one of which includes the Mn containing dithiocarbamate fungicide maneb (MB) (Thiruchelvam et al., 2000). MB alone has been observed to decrease locomotor activity and increase toxicity of MPTP (Morato et al., 1989; Takahashi et al., 1989).

Toxicants such as MPTP, rotenone, PQ, and MB have been employed to create murine models for PD, and through these models, mechanisms of toxicity have been uncovered which aid in the description of PD pathology, including altered gene expression (Patel et al., 2008) and loss of dopaminergic neurons through apoptosis (Fei and Ethell, 2008). Although MB and PQ alone are cytotoxic at higher concentrations, combined exposure of the 2 compounds shows altered cellular activity at much lower concentrations (Thiruchelvam et al., 2000). For instance, induction of catalase and glutathione (GSH) was enhanced in combination treatment in mice and neuroblastoma cells (Patel et al., 2006; Roede et al., 2011). Additionally, our lab has shown that combination treatment resulted in carbonylation of proteins via oxidative stress throughout the mouse brain, with MB alone having the greatest effect on the cortex. Finally, it is important to note that MB alone has not been observed to decrease striatal dopamine in mouse models, although there was marked disruption of olfactory discrimination, a hallmark clinical indicator of PD (Coughlan et al., 2015).

More recently, mechanistic investigation has revealed PQ-mediated redox cycling and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation through disruption of complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) (Castello et al., 2007). MB’s contribution to the model includes disruption of the ETC at complex III (Zhang et al., 2003), decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) (Domico et al., 2006), and modification of the pharmacokinetics for PQ in mice (Barlow et al., 2003). Of importance, it has been reported that MB-induced inhibition of mitochondrial respiration is completely rescued with addition of complex IV substrates (Zhang et al., 2003). Increased ROS affects intracellular redox states, and it has been shown that MB does not potentiate PQ toxicity simply by increasing ROS (Roede et al., 2011). Furthermore, MB causes increased translocation of Nrf2 to the nucleus and induction of the antioxidant response. Additional studies into potential mechanisms of MB-mediated toxicity have shown thiol-reactivity of the dithiocarbamate moiety through cysteine alkylation (Roede and Jones, 2014a). Investigation of this mechanism may define MB’s role in disruption of redox circuits either at active sites or allosteric cysteines. Lastly, transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of MB treatment in mouse catecholaminergic neuronal cells have also revealed alterations in metabolic pathways (including glycolysis), providing insight to another possible pathway of toxicity (Roede et al., 2014).

Neuroblastoma cell lines are common in vitro models for neurodegenerative diseases and are commonly used for PD research (Rcom-H’cheo-Gauthier et al., 2017; Roede et al., 2011). Specifically, the SK-N-AS cell line is derived from the same primary patient samples as SH-SY5Y with a similar dopaminergic profile including dopamine receptors, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, tyrosine hydroxylase, and dopamine transporter (Michelhaugh et al., 2005; Zhai et al., 2018). For consideration of Seahorse extracellular flux (XFp) analysis, SH-SY5Y create poorly adherent aggregates in cell culture, whereas SK-N-AS have uniform adherence to culture plates (Biedler et al., 1973). Furthermore, SK-N-AS have been found to not require insulin-like growth factor II for proliferation, adapting them for culture and growth in serum-free media such as Seahorse XFp Assay Medium (El-Badry et al., 1991). In this study, SK-N-AS human neuroblastoma cells were acutely treated with MB and analyzed utilizing Seahorse XFp technology in order to better characterize MB’s effects on mitochondria and ATP-generation. Utilizing this method, we further confirmed lowered mitochondrial respiration and ATP production commonly observed in MB exposure. Novel parameters of energetics such as proton leak and nonmitochondrial oxidation were increased with MB treatment. Flexibility of mitochondrial oxidative substrates was nearly eliminated for all 3 major fuel sources after MB exposure. Additionally, acidification of the extracellular matrix (ECM) related to glucose metabolism was drastically decreased, presenting a potential new candidate pathway of altered bioenergetics after MB treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

DMSO (Product number 472301), MB (Product number 45554), Manganese chloride in solution (Product number M1787-10X1ML), and nabam (Product number 45593) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, Missouri). MB and nabam stock solutions (10–30 mM) were prepared in DMSO. MnCl2 stock solution was diluted with deionized water to prepare working solutions. Reagents for Seahorse XFp were purchased directly from manufacturer (Agilent, Santa Clara, California).

Cell culture of SK-N-AS cells

Human SK-N-AS cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Rockville, Maryland). They were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle Minimal essential medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, New York) containing 10% Fetal bovine serum (Product number A316040, Gibco, Gaithersburg, Maryland) and 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen) at 37°C under 5% CO2. Cells used for all assays were between passages 5 and 12.

Cell viability and ATP assays

For the evaluation of cell viability, SK-N-AS cells were plated in a 96-well plate (50 000 cells/well) and allowed to recover and adhere overnight. Cells were treated with MB (0–400 μM, n = 5) or DMSO (0.5%, n = 5) for 1 or 24 h. After the treatment period, a WST-1 colorimetric assay (Roche, Product number 05015944001) was used to assess cell viability as per the manufacturer’s protocol. A SpectraMax 190 microplate reader (Molecular devices, Sunnyvale, California) was used to read the absorbance at 450 nm. Additionally, flow cytometry was performed on the Muse Analyzer (Millipore Sigma, Carlsbad, California) using the Annexin V/Dead Cell Assay kit (Millipore, product number MCH100105). Cells were plated in a 12-well plate at 200 000 cells per well in 1 ml culture medium. Cells were grown to approximately 80% confluence and then treated with 0.5% DMSO (negative control, n = 3), 50 µM MB (n = 3), or 10 mM H2O2 (positive control, n = 3) for 2 or 24 h. The concentration of H2O2 was optimized by testing a range of concentrations from 5 to 20 mM. After the treatment period, cells were prepared and 2000 total events per sample were measured according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were harvested and reconstituted in 1 ml fresh culture media. 100 µl of cells were aliquoted into 1.5 ml in triplicate and combined with 100 µl of reagent for analysis. To investigate the effect of MB treatment to cellular ATP production, the CellTiter-Glo Assay was used (Promega, Catalog number G7570). SK-N-AS cells were plated in a 96-well plate (50 000 cells/well) and allowed to recover and adhere overnight. Cells were treated with MB (50 μM, n = 5) or DMSO (0.5%, n = 5) for 1 h. After the 1 h treatment, cell culture medium was replaced with medium containing CellTiter-Glo reagent (1:1 ratio). Cells were incubated for 10 min and chemiluminescence was measured by an EnVision plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, Massachusetts).

Seahorse XFp analysis

Live cell analyses of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured with the Seahorse XFp system (Agilent). New cell characterization was performed on SK-N-AS cells according to manufacturer’s protocol, yielding an FCCP concentration of 1.5 µM. Cells were plated at 30 000 cells per well and allowed to seed overnight in a cell culture incubator at 37°C with an XFp cartridge hydrating overnight in a nonCO2 incubator at 37°C. On the day of the analysis, assay media was prepared similar to culture media (25 mM glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 4 mM L-glutamine) and pH was adjusted to 7.4 ± 0.1. The XFp miniplate was washed twice with 1× PBS and a final volume of 180 µl assay media was added to cells. Then, the XFp miniplate was allowed to equilibrate in nonCO2 incubator at 37°C for 30–60 min prior to assay initiation.

Acute injections

Port A on the XFp cartridge was designated for acute treatment of control (0.5% DMSO) or 50 μM MB at 20 µl per well. Ports B-D were assigned for each stress test at varying volumes to account for injection into each well (B = 22 µl, C = 25 µl, D = 27 µl). MB/DMSO was prepared fresh in assay media at 10× concentration prior to each day’s experiments, giving a final well concentration of 50 µM.

Cell energy phenotype

Manufacturer’s protocol was followed for the Cell Energy Phenotype kit with port B containing the FCCP/oligomycin stressor mix at 1.5/1.0 µM (final well concentration).

Cell mito stress

Manufacturer’s protocol was followed for the Cell Mito Stress Test kit with port B containing oligomycin (ATP-Synthase inhibitor) at 1.0 µM, port C with 1.5 µM FCCP (mitochondrial membrane depolarizer), and port D with a mixture of 0.5 µM of each rotenone (complex I inhibitor) and antimycin A (complex III inhibitor) (final well concentration).

Glycolysis stress

Manufacturer’s protocol was followed for the Glycolysis Stress Test kit with port B containing 10 mM glucose, port C with 1.0 µM oligomycin, and port D with 50 mM 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) (competitive hexokinase inhibitor) (final well concentration). NOTE: Assay media for this test does not include glucose or sodium pyruvate.

Fuel flex

Manufacturer’s protocol was followed for the Fuel Flex Test kit to test dependency, capacity, and flexibility of the 3 major fuel sources of mitochondrial oxidation (glucose, glutamine, and fatty acids). For all assays, cell culture media was replaced with assay media containing DMSO (0.5%) or 50 µM MB immediately before equilibration for approximately 30 min in nonCO2 incubator prior to assay initiation. Three pathway inhibitors (pyruvate = 2 µM UK5099, glutamine = 3 µM Bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES), fatty acids = 4 µM etomoxir) are utilized in succession to evaluate percentage of total oxygen consumption reduced by either a single pathway inhibitor, or a combination of all other pathway inhibitors. NOTE: The calculation of flexibility involves the mean values for capacity and dependency, and has no associated error.

Normalization and calculations

Aside from a normalized plating protocol, each run is normalized to control basal ECAR or OCR (for ECAR, basal is represented after glucose injection) to account for between-run variation (Eakins et al., 2016; Mdaki et al., 2016). Figures represent parameters calculated using normalized percentage values. All calculations were made within each individual well. n = 7–9 represents 3 separate analyses in which significant outlier wells are removed from data analysis using Grubb’s test.

Total lactate dehydrogenase activity

For the evaluation of total lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, SK-N-AS cells were plated in a 96-well plate (50 000 cells/well) and allowed to recover and adhere overnight. Cells were treated with a single dose of MB (50 μM, n = 5) or DMSO (0.5%, n = 5) for 1h. After the 1 h treatment, a LDH colorimetric assay (Sigma-Aldrich, product number TOX7) was used to assess total LDH activity as per the manufacturer’s protocol. A SpectraMax 190 microplate reader (Molecular devices, Sunnyvale, California) was used to read the absorbance at 490 nm with a background reading for subtraction at 690 nm.

LC/MS/MS nucleotide analysis

Extraction of nucleotides and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) metabolites coupled with Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) analysis was performed according to a recently published protocol (Evans et al., 2010). Briefly, cells were treated in 6-well plates at 80%–90% confluence with DMSO or 50 µM MB for 1 h. After treatment, cells were extracted and suspended in 500 µl of ice cold 70:30 methanol:water with the addition of 20 µl of isotopically labeled internal standard mix. Samples were centrifuged and supernatant was removed. A 500 µl of ice-cold methanol was added to samples to resuspend the pellet, with supernatant removed and combined with previously removed portion. Supernatant solution was centrifuged and newly generated supernatant transferred into new 1.5 ml tube for drying in a vacuum centrifuge. Dried samples were reconstituted in 100 µl of 1:1 methanol: water, with supernatant transferred to auto-sampler vial for LC/MS/MS analysis. Samples were run on an Agilent 1200 series HPLC using a Luna NH2 column from Phenomenex in HILIC mode with a mobile phase gradient of buffer A (100% ACN) and 5%–100% buffer B (95:5 water: ammonium acetate) with a total run time of 20 min. Mass spectrometric analyses were performed on an Agilent 6410 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in positive ionization mode.

Incucyte S3 live-cell analysis

Images of SK-N-AS cells were captured before and after treatment at 10 min intervals using the Incucyte S3 Live Cell Analyzer (Essen Bioscience, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI) at 10× magnification. A 6-well plates of SK-N-AS cells were brought to approximately 80% confluence, imaged once in the Incucyte analyzer, then treated with 0.5% DMSO or 50 µM. The plates were then analyzed for 24 h with 3 image locations per well at 10-min intervals. Incucyte software was used to apply confluence mask and calculate confluence over the 24 h exposure. Videos were created of images in progression for both control and MB exposed samples and uploaded to Dryad data service.

Statistics

All data sets were analyzed using GraphPad v7 with either student’s t-test (with Welch’s correction where applicable) or either 1- or 2-way ANOVA with post hoc testing (unless otherwise noted). All Seahorse XFp experiments were conducted in triplicate with at least 3 replications per experiment. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

RESULTS

50 µM MB Disrupts Cellular Metabolism without Cytotoxicity in Neuroblastoma Cells

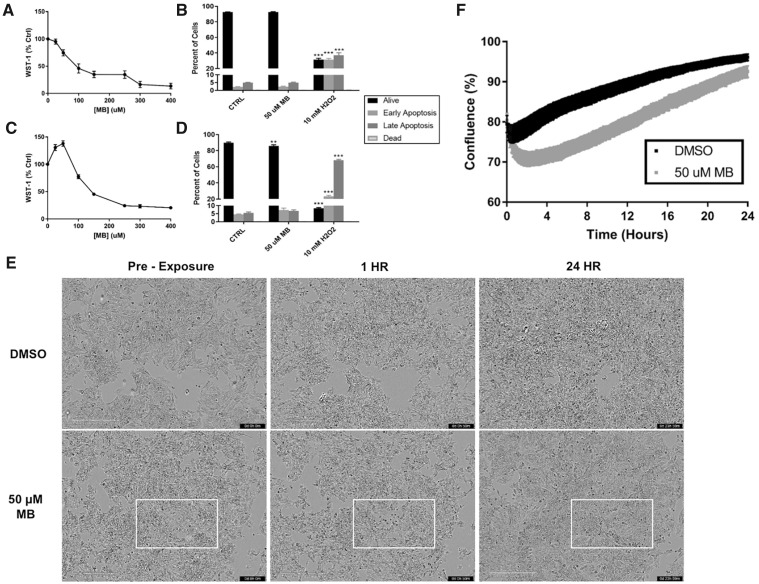

To assess cytotoxicity of MB in SK-N-AS cells, a WST-1 assay was employed. According to Sigma-Aldrich, the WST-1 colorimetric assay measures metabolic activity as a sign of health via mitochondrial dehydrogenase enzymes that reduce a tetrazolium salt to a formazan dye. Comparisons between acute (1 h) and 24 h treatment show a shift in metabolic activity at the 50 µM concentration (Figs. 1A and 1C). This result shows that MB causes an immediate decrease in formazan dye formation, with compensation leading to higher activity at the 24 h mark. Because the WST-1 dye is converted by mitochondrial dehydrogenase enzymes, and that we observed both a decrease in dye conversion at 1h, but an apparent compensatory increase at 24 h it was necessary to investigate cell death and viability using an alternate assay. Therefore, the effect of the 50 µM MB treatment was further validated with flow cytometry and an Annexin V/Dead Cell assay in which no acute toxicity was observed (Figure 1B). It should be noted that the 2-h time point was chosen to represent the total length of an average seahorse XFp analysis, eg, the total length of time cells would be exposed to MB. There was a statistically significant, but not substantial decrease in the percent live cells after 24 h (Figure 1D) compared with control (Control = 89.9% vs 50 µM MB = 85.9%). The SK-N-AS cells were microscopically analyzed using the Incucyte S3 Live Cell Analyzer pretreatment and at 1 and 24 h, showing morphological changes occurring after acute MB exposure (Figure 1E). At 1 h, pockets of MB exposed cells lose their shape and size, confirmed by the drop in confluence (Figure 1F, Supplementary Figure 2). However, recovery of proliferation can be observed both in the images and confluence analysis at 24 h. Video compilations of microscope images at 10-min intervals visualize a recovery in proliferation at approximately 8 h in MB exposed neuroblastoma cells (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). Therefore, due to the lack of impact on cellular viability, a concentration of 50 μM MB was used for the subsequent analyses of mitochondrial and glycolytic activity after acute injection.

Figure 1.

A 50 µM MB does not induce cell death in neuroblastoma cells. WST-1 activity was measured in SK-N-AS cells after (A) 1 h and (C) 24 h with varying concentrations of MB (n = 10, mean ± SEM). Flow cytometry of SK-N-AS cells was performed after (B) 2 h and (D) 24 h treatments in 6-well plates with 10 mM H2O2 as a positive control (n = 6, mean ± SEM). NOTE: Dead cells across all treatments measured between 0 and 0.2%. E, Images obtained at 10× magnification on the incucyte S3 Live Cell Analyzer at preexposure, 1, and 24 h treatment of DMSO or 50 µM MB. F, Confluence analysis (Supplementary Figure 2) using a phase mask in the Incucyte S3 software (n = 6, mean ± SEM).

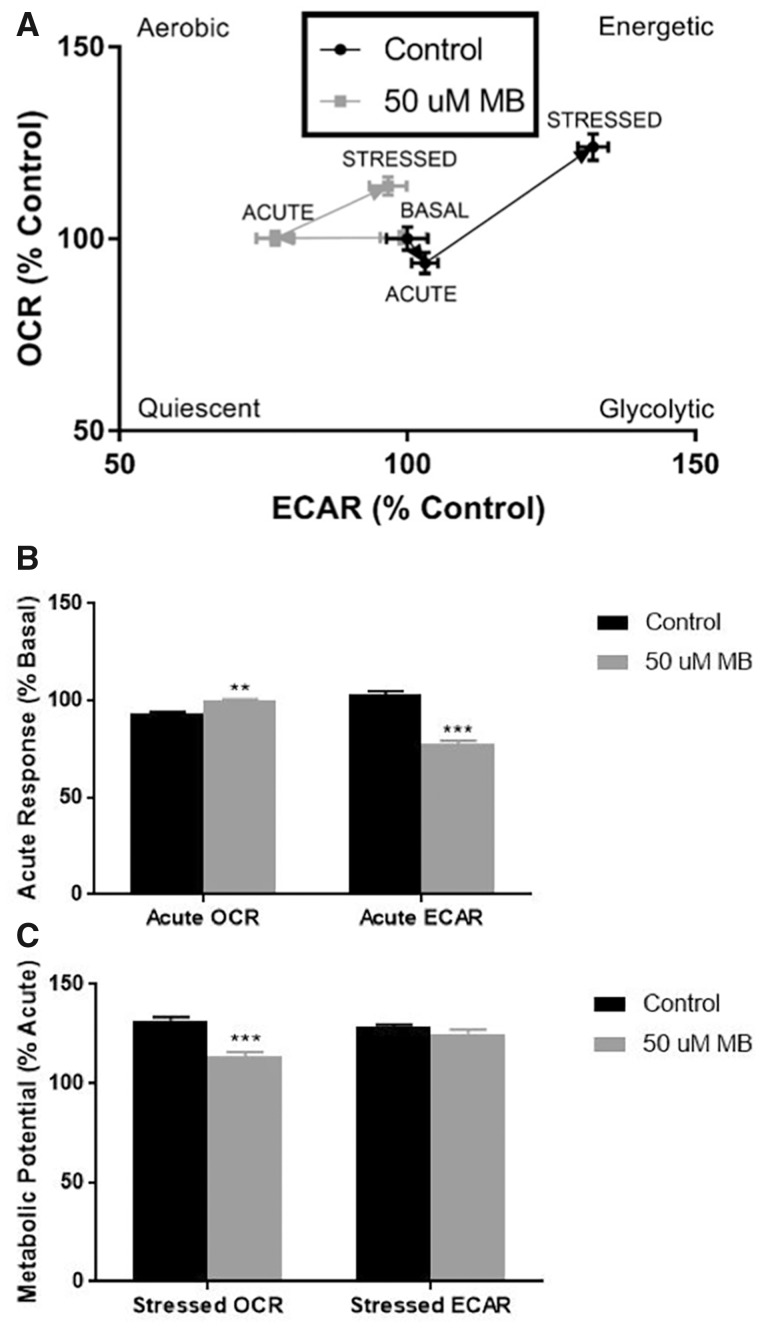

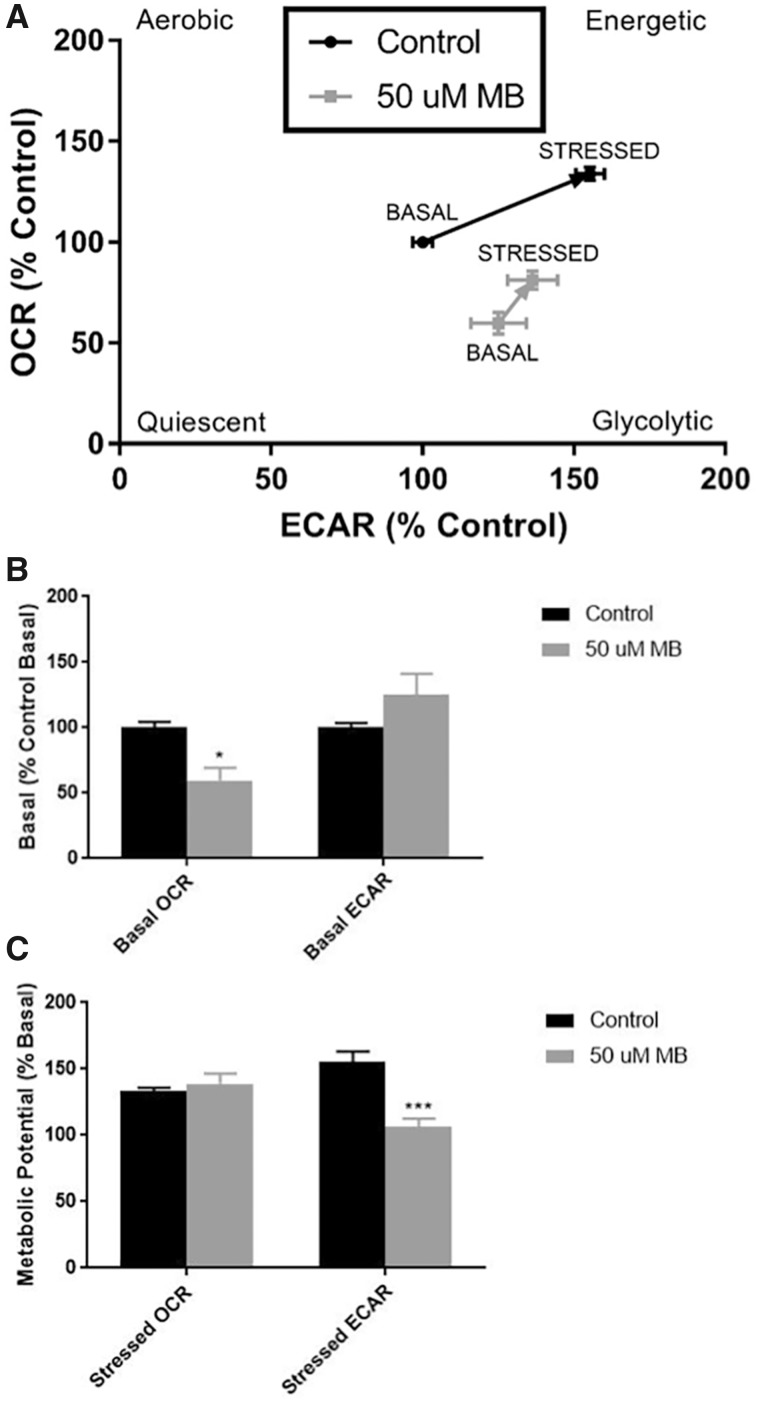

Acute Injection of 50 µM MB Immediately Alters the Energy Phenotype of Neuroblastoma Cells

The Seahorse Extracellular Flux analyzer offers several assays for live-cell assessment of bioenergetic parameters such as mitochondrial oxygen consumption, glycolysis, energy phenotype, and fuel dependency. The Cellular Energy Phenotype kit measures OCR and ECAR at baseline and stressed conditions, and this assay was modified to include an acute injection and measurements of MB-mediated and 0.5% DMSO-mediated (Control) alterations prior to stressor (oligomycin and FCCP mixture) injection (Figure 2). With the acute injection of 50 µM MB, we observed an immediate and significant decrease in ECAR (Control = 103% basal, MB = 77% basal), while DMSO treatment seemed to have a small increase in ECAR with a complimentary small decrease in OCR (Control = 93% basal, MB = 99% basal; Figs. 2A and 2B). After injection of the stressor mix, the cells treated with MB were unable to increase oxygen consumption to the same extent as control (Control = 132% acute respiration, MB = 113% acute respiration; Figs. 2A and 2C). These results show 2 distinct effects of MB on energy phenotypes. First, there is a significant decrease in acidification of the extracellular compartment after acute exposure. Second, MB exposure significantly dampens the induced mitochondrial respiration in response to the stressor mix in comparison to control. Together, these results provide rationale for further examination of MB’s impact on both mitochondrial oxygen consumption and cellular glycolysis.

Figure 2.

XFp analysis of cellular energy phenotype shows acute response to 50 µM mb in basal and stressed conditions in neuroblastoma cells. Seahorse XFp analysis using the cellular energy phenotype kit was performed with acute injection of DMSO or 50 µM MB. A, The phenotype map of OCR and ECAR within basal, acute, and stressed parameters (n = 7–9, mean ± SEM). B, Acute response as a percentage of the mean control basal OCR/ECAR (n = 3 per well) and (C) metabolic potential as a percentage of the mean acute OCR (n = 3 per well) were calculated according to manufacturer’s protocol.

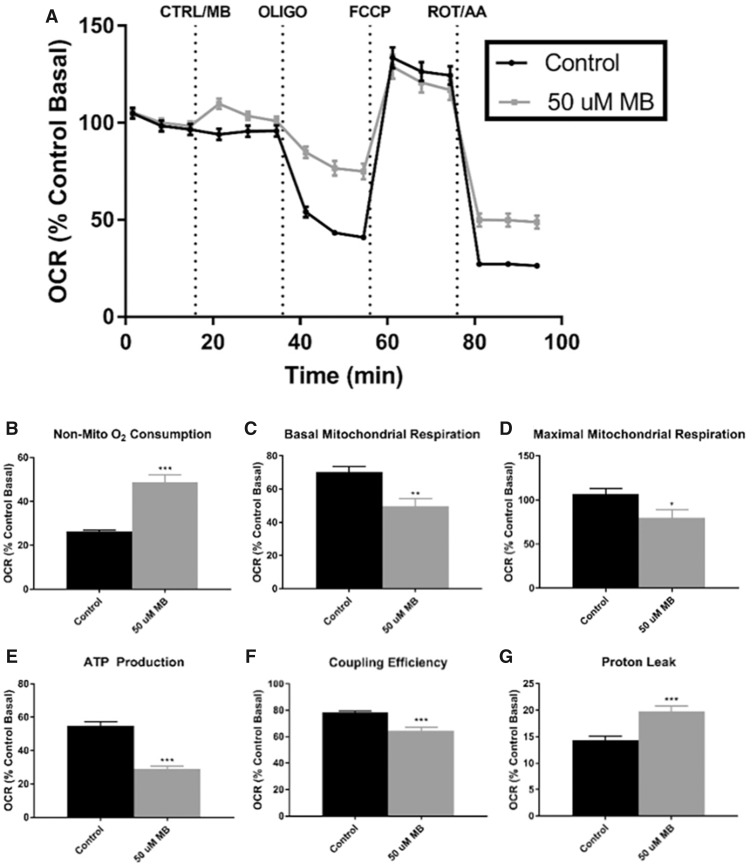

Acute Injection of 50 µM MB Alters Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption and Decreases ATP-Linked Respiration in Neuroblastoma Cells

To further investigate the effects of MB on mitochondrial function, the Cell Mito Stress Test kit was performed with a similar acute injection of DMSO or 50 µM MB (Figure 3). Acute injection of 50 µM MB caused a slight increase of OCR, indicating a possible uncoupling of the MMP, which has been previously observed with MB or mancozeb (Domico et al., 2006; Iorio et al., 2015; Pavlovic et al., 2016; Shukla et al., 2015; Srivastava et al., 2012), or may be explained by the significant difference in nonmitochondrial oxidation (Control = 14%, MB = 20%) represented by the difference in respiration after ROT/AA injection (Figure 3A). It should be noted that all parameters within the Cell Mito Stress assay are calculated with subtraction of nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption. With injection of oligomycin, cells treated with 50 µM MB maintained much higher oxygen consumption than control (Figure 3A), leading to significant differences in ATP-linked respiration (Control = 55%, MB = 29%; Figure 3E), proton leak (Control = 14%, MB = 20%; Figure 3G), and coupling efficiency (Control = 79%, MB = 64%; Figure 3F). Induction of maximal respiration with FCCP injection resulted in similar oxygen consumption in both treatments; however, with adjustment of the nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption, MB-treated cells had significantly reduced maximal mitochondrial respiration (Control = 107%, MB = 80%; Figure 3D). Last, ATP-linked respiration was nearly cut in half in the MB-treated cells (Control = 55%, MB = 29%). Similar to previous reports, ATP production through mitochondrial respiration is diminished with MB exposure (Domico et al., 2006).

Figure 3.

XFp analysis of cell mito stress shows acute disruption of ATP-linked oxygen consumption with 50 µM MB in neuroblastoma cells. Seahorse XFp analysis using the Cell Mito Stress Test kit was performed with acute injection of DMSO or 50 µM MB. A, The time course and live measurement of OCR with injections of stressor compounds (n = 7–9, mean ± SEM). Individual parameters of mitochondrial function (C) basal respiration, (D) maximal respiration, (E) ATP production, (F) coupling efficiency, and (G) proton leak were calculated according to manufacturer’s protocol with (B) nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption adjustment.

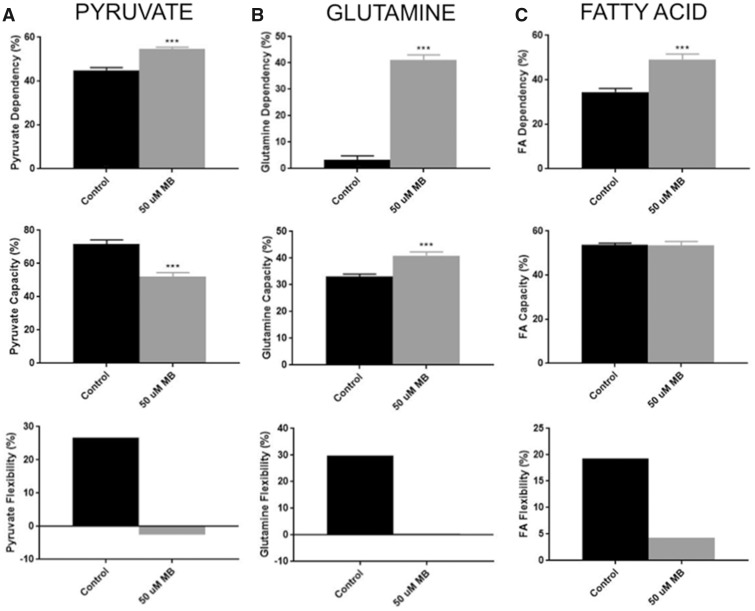

Acute Injection of 50 µM MB Eliminates Fuel Flexibility across All 3 Major Fuel Sources

Although many studies have shown mitochondrial dysfunction in both MB exposure and PD models, the effect on mitochondrial fuel utilization has not been defined. The Seahorse XFp Fuel Flex Test kit was used to test parameters of substrate utilization in acute exposures of DMSO and 50 µM MB (Figure 4). This procedure involves using pathway specific inhibitors to compare decreases in oxygen consumption after single or combined pathway inhibition. As reported by the Fuel Flex Test User Guide from Agilent, UK5099 inhibits glucose oxidation via the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. BPTES inhibits glutamine oxidation through allosteric inhibition of glutaminase. Etomoxir acts on fatty acid oxidation through inhibition of the carnitine palmitoyl-transferase. By first inhibiting the targeted pathway followed by inhibition of all other pathways, one can determine dependency of that specific fuel source. Conversely, inhibiting other pathways first and hitting the targeted pathway second allows for calculation of fuel capacity. Simply put, flexibility is a calculation of fuel dependency subtracted from fuel capacity. Targeting of the pyruvate oxidation pathway revealed a MB-mediated increase of pyruvate dependency (Control = 45%, MB = 55%; Figure 4A) and a decrease in pyruvate capacity (Control = 72%, MB = 52%; Figure 4A). This discrepancy is displayed as an elimination of flexibility for pyruvate metabolism after MB exposure. Targeting the glutamine oxidation pathway resulted in a drastic increase in glutamine utilization after MB exposure (Control = 3%, MB = 41%; Figure 4B) along with a significant increase in capacity (Control = 33%, MB = 41%; Figure 4B). Again, MB exposure results in an elimination of glutamine flexibility after acute exposure (Control = 30%, MB = 0%; Figure 4B). Although MB exposure causes an increase in FA dependency (Control = 34%, MB = 49%; Figure 4C), there is no change in FA capacity between control and MB treatments. This alteration causes a decrease in FA flexibility (Control = 19%, MB = 4%). Combined, these results represent MB-mediated metabolic stress in which exposed neuroblastoma cells operate at maximal fuel utilization across all 3 metabolic substrates.

Figure 4.

XFp analysis of fuel flex shows reduced flexibility in all 3 fuels after acute 50 µM MB exposure in neuroblastoma cells. Seahorse XFp analysis using the fuel flex test kits was performed with pretreatment (30 min) with DMSO or 50 µM MB. Dependency (n = 9, mean ± SEM), Capacity (n = 9, mean ± SEM), and flexibility were calculated per manufacturer’s protocol for (A) pyruvate (glucose), (B) glutamine, and (C) fatty acids.

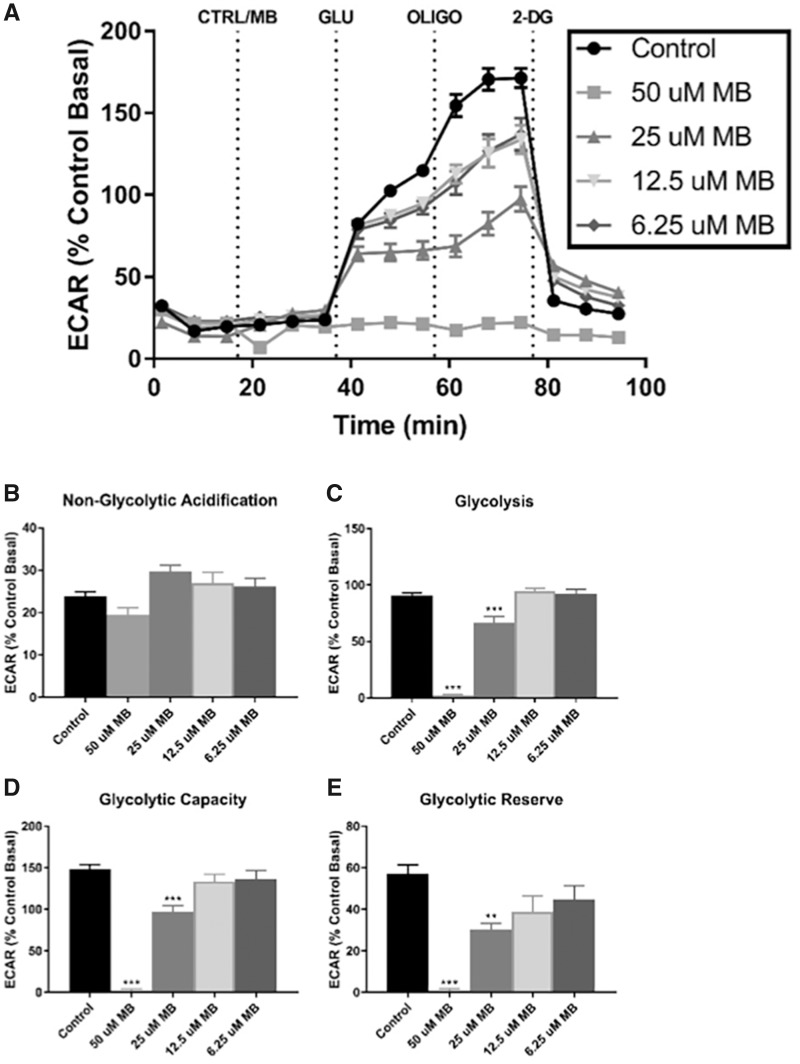

Acute Injection of 50 µM MB Nearly Eliminates Glycolytic Acidification of the ECM in Neuroblastoma Cells

Our results above indicate a significant impact of MB exposure on mitochondrial oxygen consumption and ATP production. Domico et al. have previously reported MB-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction, eg, altered oxygen consumption. They also observed that these cells did not increase lactate production in response to MB (Domico et al., 2006), but there has been no follow up on this observation; therefore, we next attempted to assess the impact that MB had on glycolytic ATP production. To test this, the Glycolysis Stress Test kit was also performed with the acute injection protocol described earlier. The assay media for these analyses does not contain glucose or sodium pyruvate, yielding initial readings of nonglycolytic acidification rates (Figure 5A). Glucose is injected as the first kit reagent, allowing for basal ECAR linked to glycolysis. 50 µM MB-treated cells exhibited lower nonglycolytic acidification after the inhibition of hexokinase by 2-DG (Control = 24%, MB = 19%; Figure 5B). Interestingly, nearly all glycolytic parameters were substantially blunted in the 50 µM MB-treated cells, including glycolysis (Control = 91%, MB = 2%; Figure 5C) and glycolytic capacity (Control = 148%, MB = 3%; Figure 4D). Additionally, glycolytic reserve, which represents the cells ability to increase glycolysis to compensate for stressors within the cell, was also virtually inhibited (Control = 57%, MB = 1%; Figure 4E). Together, these data indicate that 50 µM MB treatment have extensive impact the glycolytic pathway.

Figure 5.

XFp analysis of glycolysis stress shows acute elimination of glycolysis-associated acidification with acute MB exposure in neuroblastoma cells. Seahorse XFp analysis using the Glycolysis Stress Test kit was performed with acute injection of DMSO or MB at varying concentrations. A, The time course and live measurement of ECAR with injections of stressor compounds and substrates (n = 7–9, mean ± SEM). Individual parameters of glycolysis (B) nonglycolytic acidification, (C) glycolysis, (D) glycolytic capacity, and (E) glycolytic reserve were calculated according to manufacturer’s protocol.

The 50 μM concentration of MB was chosen based upon the cell viability and apoptosis results (Figure 1), but might not be biologically relevant in regards to human exposures. Therefore, to determine effects of MB at more biologically relevant concentrations, the Glycolysis Stress test was performed on neuroblastoma cells at 25, 12.5, and 6.25 µM MB (Figure 5). Comparison of the various doses of MB shows increasing suppression of ECAR in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A). In summary, these data show an impact of MB on glycolysis at low micromolar concentrations indicating greater biological relevance.

Neuroblastoma Cells Show Adaptation to 50 µM MB after 24 h

To observe any possible lasting effects of the MB treatment, cells were treated within the Seahorse XFp microplates with DMSO/MB for 24 h and subjected to the Cellular Energy Phenotype test. Results from these experiments show a modified basal phenotype in the MB-treated cells in comparison to control (Figure 6A). Basally, MB-treated cells had significantly lowered oxygen consumption (Control = 100%, MB = 60%) and generally elevated, but more variable, ECAR measurements (Figure 6B). After injection of the stressor mix, MB-treated cells were able to increase OCR to the same extent as DMSO treat controls (Control = 134%, MB = 139%; Figure 6C); however, induction of glycolysis to compensate for stress was significantly decreased in the MB-treated cells (Control = 156%, MB = 107%; Figure 6C). These data indicate that MB-mediated alterations in both mitochondrial oxygen consumption and glycolysis are not transient and can be observed at least 24-h postexposure.

Figure 6.

XFp analysis of cellular energy phenotype after 24-h treatment of 50 µM MB in neuroblastoma cells shows adjustment of cellular energetics. Seahorse XFp analysis using the Cellular Energy Phenotype kit was performed after cells treated within microplates for 24 h with DMSO or 50 µM MB. A, The phenotype map of OCR and ECAR within basal and stressed parameters (n = 7–9, mean ± SEM). B, Basal phenotype as a percentage of the mean control basal OCR/ECAR (n = 3 per well). C, Metabolic potential as a percentage of the mean basal OCR/ECAR (n = 3 per well) were calculated according to manufacturer’s protocol.

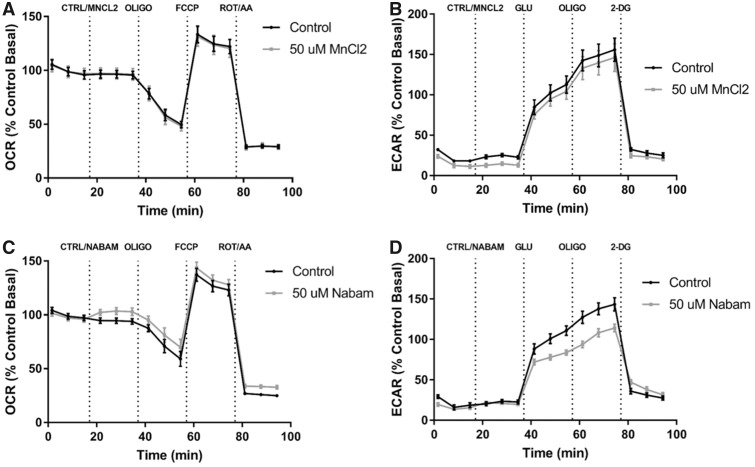

MB’s Effect on Bioenergetics in Neuroblastoma Cells Is Primarily Caused by the Dithiocarbamate Mechanism

To further investigate if MB-mediated alterations in mitochondrial oxygen consumption and glycolysis can be attributed to the metal component (Mn) or the dithiocarbamate moiety of MB, 2 additional compounds were tested and compared with vehicle controls, MnCl2 and nabam (Figure 7). To investigate the role of Mn, 50 µM MnCl2 was acutely injected similar to previous MB assays and both the Cell Mito Stress and the Glycolysis Stress Tests were performed. The time course profiles of MnCl2 treatment and control (water) were similar with no apparent Mn-mediated effect on either oxygen consumption or glycolysis in our model (Figs. 7A and 7B). Next, neuroblastoma cells were treated with control (DMSO) and 50 µM nabam, a dithiocarbamate similar to MB in structure containing Na instead of Mn. The time course of cells treated with 50 µM nabam shows decreased glycolysis-associated ECAR compared with DMSO controls, but mitochondrial oxygen consumption was not significantly impacted (Figs. 7C and 7D). These data indicate that the organic component (dithiocarbamate), not the inorganic (Mn), is playing the greatest role in modulating glycolytic function.

Figure 7.

XFp analysis of 50 µM MnCl2 and 50 µM nabam suggest interaction between metal effect and dithiocarbamate. Seahorse XFp analysis using the cell mito stress test and glycolysis stress test was performed with the acute injection of DMSO, 50 µM MnCl2, or 50 µM nabam. A, Cell mito stress test time course and (B) glycolysis stress time course for 50 µM MnCl2 similar to previous analyses (n = 7–9, mean ± SEM). C, Cell mito stress test time course and (D) glycolysis stress time course for 50 µM nabam (n = 7–9, mean ± SEM).

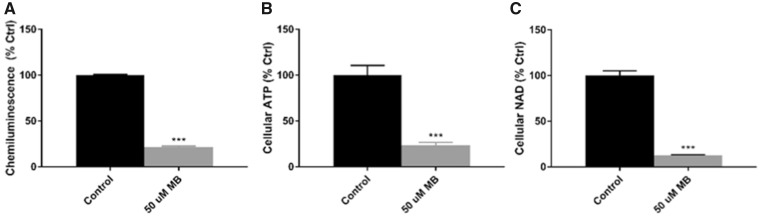

50 µM MB Depletes Cellular ATP and NAD in Neuroblastoma Cells

Finally, to confirm the reduction in ATP-linked respiration seen in the Cell Mito Stress Test and almost complete ablation of glycolytic activity with treatment of 50-µM MB, the CellTiter-Glo chemiluminescence assay was performed across concentrations of MB after 1 h of treatment to measure cellular ATP (Figure 8). At 50 µM MB, treated cells showed significantly reduced cellular ATP (Control = 100%, MB = 21%, Figure 8A) while higher concentrations showed near complete depletion of ATP compared with control (data not shown). Next, LC/MS/MS analyses of cellular nucleotides further confirmed a reduction of cellular ATP in 50 µM MB-treated cells compared with control (Control = 100%, MB = 23%; Figure 8B). The LC/MS/MS studies also revealed a reduction in other cellular energy substrates, including NAD (Control = 100%, MB = 13%, Figure 8C). It is important to note that even though the acute 50 μM MB treatment resulted in significant ATP depletion, this particular treatment did not result in extensive apoptosis or necrosis (Figure 1).

Figure 8.

50 µM MB reduces cellular ATP and NAD in neuroblastoma cells. A, CellTiter-Glo chemiluminescence assay was performed on neuroblastoma cells at 50 µM MB or 0.5% DMSO for 1 h of treatment and displayed as percent control (n = 10, mean ± SEM). B, LC/MS/MS nucleotide assay was performed with DMSO and 50 µM MB (n = 6, mean ± SEM). Percent control is reported for 50 µM MB for (B) Cellular ATP and (C) Cellular NAD.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here further confirm the ability of MB to disrupt mitochondrial oxygen consumption and introduce novel findings of MB-mediated alterations in mitochondrial fuel utilization and glycolysis. Similar to previous studies, MB caused decreased respiration, specifically oxygen consumption linked to ATP synthesis. Results from the CellTiter-Glo and LC/MS/MS nucleotide assay helped to quantify this effect on respiration and glycolysis by showing nearly an 80% reduction in cellular ATP and >80% reduction in cellular NAD. Furthermore, the analyses performed show alterations of multiple pathways of cellular energy metabolism contributing to this drastic reduction in ATP.

Pesticide exposure has been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and protein agglomeration seen in PD pathology (Choi and Xia, 2014). To date, MB-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction has been defined through 2 general mechanisms. First, inhibition of enzymes in the mitochondrial ETC with preferential suppression of complex III observed in isolated mitochondria (Zhang et al., 2003). Second, many studies have shown decreased MMP after MB and mancozeb exposure in vitro and in vivo (Domico et al., 2006; Iorio et al., 2015; Srivastava et al., 2012). MMP disruptions have been linked to uncoupling of mitochondrial respiration leading to enhanced mitochondrial ROS production and decreased ATP synthesis (Domico et al., 2006; Srivastava et al., 2012). With results from several cell viability and health assays (Figure 1), we are confident in 50 µM MB lack of direct acute effect on cell viability. Interestingly, we actually observed an increase in the WST-1 colorimetric assay, showing and increase in mitochondrial activity at 24 h in neuroblastoma cells exposed 50 µM MB when compared with the DMSO control. This result most likely represents a cellular “rewiring” of mitochondrial energetics to compensate for the MB-mediated damage. As our first aim, we looked to further characterize these effects of mitochondrial uncoupling in the neuroblastoma cell model with acute MB exposure. Using the Seahorse XFp Mito Stress Test kit, acute exposure of MB yielded decreased basal and maximal oxygen consumption, confirming inhibition of the ETC in this model (Drechsel and Patel, 2008). Furthermore, the increase in proton leak and consequential decrease in coupling efficiency of MB-treated cells describes inhibition of ATP production via disruption of complexes I and III of the ETC and MMP disruption (Zhang et al., 2003). The exact mechanism of MB-mediated ETC inhibition is still unknown as many observations are based on the production of ROS within the ETC observed with disruption at complex I and III. A previous report from our laboratory demonstrated that MB can act as a thiol reactive substance (Roede and Jones, 2014), enabling interactions with critical cellular thiols that may be involved in redox signaling and control of metabolic processes. In this context, complex I has been reported to be redox regulated via glutathionylation of specific residues that result in enhanced superoxide production (Taylor et al., 2003). Complex I has also been observed to be redox regulated via S-nitrosylation in heart (Chouchani et al., 2013). Although MB exposure has been reported to inhibit complex III activity and PD pathology relates to inhibition of complex I, both would result in increased ROS leakage and decreased ATP production (Hu and Wang, 2016; Lismont et al., 2015). Furthermore, dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta have been shown to be uniquely sensitive to complex I inhibition (Drechsel and Patel, 2008). The involvement of mitochondria and redox signaling has been highly described as the ETC is a well-known source of ROS, specifically mitochondrial H2O2 as a signal for redox control of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (Lismont et al., 2015). However, MB-mediated redox control of specific ETC complexes has not been specifically studied, and more focused experiments are required to understand this potential alkylating agent’s impact on complex activity.

Of particular interest is the observation of increased nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption shown in MB-treated cells, which may represent the immediate induction of nonETC oxygen consumption or alternate pathways of ATP production. One such pathway would include lactate oxidation as seen in other neuronal systems (Kane, 2014). Another possibility is activation of NADPH oxidase enzymes, which has been previously observed in polymorphonuclear leukocytes after MB exposure (Shukla et al., 2015). Further investigation of alternative oxidative substrates and other oxygen consuming systems activated by MB exposure is required to fully describe this observation and work is currently underway to study this.

Our next aim was to expand on MB-mediated mitochondrial alterations by investigating changes in oxidative fuel flex within neuroblastoma cells after acute exposure. Although direct mechanisms of disruption are not revealed, these data show an increase in dependency across all 3 fuel pathways, defining metabolic stress within this exposure. Furthermore, a decrease in capacity was observed for pyruvate and gives insight to a potential direct inhibition of glycolysis leading to a decrease in cellular pyruvate available for oxidation. Additionally, drastic differences in glutamine utilization were observed between control and MB exposed cells. This increase in glutamine oxidation may have an indirect effect on GSH synthesis acutely, although previous reports show an increase in GSH after 24 h MB exposure (Roede et al., 2011).

We then shifted focus to nonmitochondrial ATP-generating processes to further define MB’s effect on bioenergetics. Although the response to MB exposure observed during the Glycolysis Stress Tests was quite drastic, the interpretation must be approached with caution, as the signal being measured is the acidification caused by export of lactic acid formed during anaerobic processing of pyruvate from glycolysis. This signal is far downstream of glycolysis, and perturbations of the pathway or signal can occur at multiple protein systems such as glycolysis, LDH, and lactate/pyruvate transporters. For instance, if MB is in fact inhibiting glycolysis prior to pyruvate conversion to lactate by LDH, it would be expected that LDH activity would be decreased causing a reduction in lactic acid export. As LDH also replenishes NAD pools through conversion of NADH as a cofactor in pyruvate metabolism to lactate, it would potentially explain a reduction in cellular NAD (Adams et al., 1973). However, it is possible that MB may alter the fate of pyruvate postglycolysis, similar to altered glycolysis to combat oxidative stress (Mullarky and Cantley, 2015). It would be expected that if this were the case, an increase in mitochondrial oxygen consumption would have been observed as opposed to the actual decrease reported, as pyruvate is a fuel for mitochondrial oxidation. Another possible mechanism for disruption of the lactate pathway is the use of lactate as a fuel source as seen in both cancer (Bonuccelli et al., 2010) and neuronal systems (Kane, 2014; Yamada et al., 2009). Due to lactate export into the extracellular compartment and low cellular lactate concentrations, reversal of LDH is rarely observed in biological systems. However, it has been shown that LDH within the mitochondria can oxidize pyruvate into lactate, which then can enter the TCA cycle as fuel. Oxidation of pyruvate utilizes cellular NAD, potentially contributing to depletion of the cellular pool as was observed. Additionally, this could explain the increase in nonETC linked respiration observed after acute MB exposure. Further studies into the glycolysis and LDH pathways are needed to describe this observation in the Seahorse XFp model.

Due to the fact that NAD is a cofactor of many cellular metabolic and antioxidant enzymes, this depletion caused by MB exposure could explain the enhanced toxicity when in combination with PQ (Belenky et al., 2007; Roede et al., 2011). Furthermore, many cellular mechanisms are reliant upon ATP, such as reduction of cellular chaperones and apoptosis. Similar to other studies, morphological changes after MB treatment visualizes the stress that depletion of ATP and NAD imparts (Figure 1E) causes on these neuroblastoma cells, and it would be plausible that higher concentrations of MB would tip the cells past a “breaking point” inducing cell death pathways (Figure 1). In regards to the morphologic changes that occurred in our study, shorter neuritic processes were also observed after MB or MZ exposure in rat primary mesencephalic neurons (Domico et al., 2006). It should be noted that in a previous in vivo study investigating PQ and MB-mediated changes in protein carbonylation in mouse cortex and striatum revealed that this exposure significantly impacted the actin cytoskeleton (Coughlan et al., 2015). Additionally, it has been shown using redox proteomics approaches that the actin cytoskeleton is a sensitive target (Go et al., 2013a,b). Further investigation into the potential MB-mediated changes in the actin cytoskeleton is needed to determine the impact on neuron function.

MnCl2 and nabam treatment of neuroblastoma cells confirm previous studies that MB’s effect on energy metabolism is more pronounced than the individual metal or dithiocarbamate effect (Zhang et al., 2003). This could represent interactions between the metal component of MB and the dithiocarbamate functional group, with the chemical properties of manganese potentiating the compound’s effect (Zhang et al., 2003). Additionally, decreasing the concentration of MB during acute exposure revealed significant disruption of glycolytic acidification down to 6 µM, showing relevance to potential occupational exposure levels (Gorell et al., 1998).

As MB has been shown to modify protein thiols, it is important to investigate and acknowledge the possibility of disruption of redox signaling in both mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis (Roede and Jones, 2014). For instance, ATP synthase (Complex V) and LDH have been shown to contain allosteric cysteine residues involved in redox control of enzyme activity (Adams et al., 1973; Wang et al., 2013). Furthermore, many enzymes involved in glycolysis have shown redox control especially modifying the pentose phosphate pathway as an alternative to pyruvate formation (Mullarky and Cantley, 2015). A recent comparative proteomics study found increased carbonylated proteins involved in many metabolic pathways including sugar and amino acid metabolism (Coughlan et al., 2015). Additionally, Go et al. showed, using redox proteomics, that glycolysis is a major pathway that is redox regulated via the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase/NADPH system (Go et al., 2013b). Preliminarily, neuroblastoma cells treated with 50 μM MB showed a significant reduction in total LDH activity compared with control of about 15% (Supplementary Figure 1). This result is different than an LDH release assay, as the cells are lysed and given sufficient substrate and cofactor for enzyme activity analysis. However, depletion of NAD seen in the mass spectrometry assays is not accounted for in this test for LDH activity. Further investigation into redox regulation of mitochondrial and glycolytic enzymes, as well as oxidative substrates in both normal and pathological conditions is needed and may reveal specific mechanisms that can be targeted by therapeutics.

In conclusion, this study validates the disruption of mitochondrial and glycolytic energy production with acute exposure to noncytotoxic concentrations of MB in neuroblastoma cells. Oxidation of all 3 major fuel substrates is operating at maximal capacity after acute MB exposure in this neuroblastoma cell model, providing better characterization of metabolic stress. Extracellular compartment acidification seen in control cells is nearly eliminated after acute MB treatment, presenting novel findings of bioenergetics disruption outside of the mitochondria. It is our belief that combined toxicity of MB and PQ may involve MB-mediated sensitization of neurons through depletion of energy substrates in addition to PQ-mediated depletion of GSH and generation of ROS. Combined toxicity may be observable in concentrations closer to environmental exposure, further describing the risk associated with pesticide exposure and PD pathology. As PD pathology is specific to dopaminergic neurons within the substantia nigra, comparison of energy dependence and flexibility among different categories of neurons may uncover the mechanism of this specificity and present dopaminergic-specific targets for PD therapeutics.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr Ryan Smith, Dr Ajit Divakaruni, Dr Natalia Romero, Allan Schell, and Michael Armstrong for their guidance and support in the presented research.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 ES027593).

REFERENCES

- Adams M. J., Buehner M., Chandrasekhar K., Ford G. C., Hackert M. L., Liljas A., Rossmann M. G., Smiley I. E., Allison W. S., Everse J.. et al. (1973). Structure-function relationships in lactate dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 70, 1968–1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow B. K., Thiruchelvam M. J., Bennice L., Cory-Slechta D. A., Ballatori N., Richfield E. K. (2003). Increased synaptosomal dopamine content and brain concentration of paraquat produced by selective dithiocarbamates. J. Neurochem. 85, 1075–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky P., Bogan K. L., Brenner C. (2007). NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedler J. L., Helson L., Spengler B. A. (1973). Morphology and growth, tumorigenicity, and cytogenetics of human neuroblastoma cells in continuous culture. Cancer Res. 33, 2643–2652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuccelli G., Tsirigos A., Whitaker-Menezes D., Pavlides S., Pestell R. G., Chiavarina B., Frank P. G., Flomenberg N., Howell A., Martinez-Outschoorn U. E.. et al. (2010). Ketones and lactate “fuel” tumor growth and metastasis: Evidence that epithelial cancer cells use oxidative mitochondrial metabolism. Cell Cycle 9, 3506–3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello P. R., Drechsel D. A., Patel M. (2007). Mitochondria are a major source of paraquat-induced reactive oxygen species production in the brain. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14186–14193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W. S., Xia Z. (2014). Maneb-induced dopaminergic neuronal death is not affected by loss of mitochondrial complex I activity: Results from primary mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons cultured from individual Ndufs4+/+ and Ndufs4-/- mouse embryos. Neuroreport 25, 1350–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouchani E. T., Methner C., Nadtochiy S. M., Logan A., Pell V. R., Ding S., James A. M., Cocheme H. M., Reinhold J., Lilley K. S.. et al. (2013). Cardioprotection by S-nitrosation of a cysteine switch on mitochondrial complex I. Nat. Med. 19, 753–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan C., Walker D. I., Lohr K. M., Richardson J. R., Saba L. M., Caudle W. M., Fritz K. S., Roede J. R. (2015). Comparative proteomic analysis of carbonylated proteins from the striatum and cortex of pesticide-treated mice. Parkinson Dis. 2015, 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domico L. M., Zeevalk G. D., Bernard L. P., Cooper K. R. (2006). Acute neurotoxic effects of mancozeb and maneb in mesencephalic neuronal cultures are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Neurotoxicology 27, 816–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel D. A., Patel M. (2008). Role of reactive oxygen species in the neurotoxicity of environmental agents implicated in Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44, 1873–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakins J., Bauch C., Woodhouse H., Park B., Bevan S., Dilworth C., Walker P. (2016). A combined in vitro approach to improve the prediction of mitochondrial toxicants. Toxicol. In Vitro 34, 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Badry O. M., Helman L. J., Chatten J., Steinberg S. M., Evans A. E., Israel M. A. (1991). Insulin-like growth factor II-mediated proliferation of human neuroblastoma. J. Clin. Investig. 87, 648–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C., Bogan K. L., Song P., Burant C. F., Kennedy R. T., Brenner C. (2010). NAD+ metabolite levels as a function of vitamins and calorie restriction: Evidence for different mechanisms of longevity. BMC Chem. Biol. 10, 2.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Q., Ethell D. W. (2008). Maneb potentiates paraquat neurotoxicity by inducing key Bcl-2 family members. J. Neurochem. 105, 2091–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forno L. S., Langston J. W., DeLanney L. E., Irwin I., Ricaurte G. A. (1986). Locus ceruleus lesions and eosinophilic inclusions in MPTP-treated monkeys. Ann. Neurol. 20, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go Y. M., Orr M., Jones D. P. (2013a). Actin cytoskeleton redox proteome oxidation by cadmium. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 305, L831–L843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go Y. M., Roede J. R., Walker D. I., Duong D. M., Seyfried N. T., Orr M., Liang Y., Pennell K. D., Jones D. P. (2013b). Selective targeting of the cysteine proteome by thioredoxin and glutathione redox systems. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 3285–3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorell J. M., Johnson C. C., Rybicki B. A., Peterson E. L., Richardson R. J. (1998). The risk of Parkinson’s disease with exposure to pesticides, farming, well water, and rural living. Neurology 50, 1346–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C., Wiens M., Bowering D., Snow B., Calne D. (1990). Parkinson’s disease: A case-control study of occupational and environmental risk factors. Am. J. Ind. Med. 17, 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Wang G. (2016). Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 5, 14.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio R., Castellucci A., Rossi G., Cinque B., Cifone M. G., Macchiarelli G., Cecconi S. (2015). Mancozeb affects mitochondrial activity, redox status and ATP production in mouse granulosa cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 30, 438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane D. A. (2014). Lactate oxidation at the mitochondria: A lactate-malate-aspartate shuttle at work. Front. Neurosci. 8, 366.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston J. W., Forno L. S., Rebert C. S., Irwin I. (1984). Selective nigral toxicity after systemic administration of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 5, 6-tetrahydropyrine (MPTP) in the squirrel monkey. Brain Res. 292, 390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lismont C., Nordgren M., Van Veldhoven P. P., Fransen M. (2015). Redox interplay between mitochondria and peroxisomes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 3, 35.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mdaki K. S., Larsen T. D., Weaver L. J., Baack M. L. (2016). Age related bioenergetics profiles in isolated rat cardiomyocytes using extracellular flux analyses. PLoS One 11, e0149002.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelhaugh S. K., Vaitkevicius H., Wang J., Bouhamdan M., Krieg A. R., Walker J. L., Mendiratta V., Bannon M. J. (2005). Dopamine neurons express multiple isoforms of the nuclear receptor nurr1 with diminished transcriptional activity. J. Neurochem. 95, 1342–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morato G. S., Lemos T., Takahashi R. N. (1989). Acute exposure to maneb alters some behavioral functions in the mouse. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 11, 421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullarky E., Cantlyey L.C. (2015). Diverting glycolysis to combat oxidative stress In: Innovative Medicine (K. Nakao, N. Minato and S. Uemoto, Eds.), 1st ed., pp. 3–23. Springer, Tokyo. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow C. W., Tatton W. G. (1999). Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 123–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S., Singh K., Singh S., Singh M. P. (2008). Gene expression profiles of mouse striatum in control and maneb + paraquat-induced Parkinson’s disease phenotype: Validation of differentially expressed energy metabolizing transcripts. Mol. Biotechnol. 40, 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S., Singh V., Kumar A., Gupta Y. K., Singh M. P. (2006). Status of antioxidant defense system and expression of toxicant responsive genes in striatum of maneb- and paraquat-induced Parkinson’s disease phenotype in mouse: Mechanism of neurodegeneration. Brain Res. 1081, 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic V., Cekic S., Ciric M., Krtinic D., Jovanovic J. (2016). Curcumin attenuates Mancozeb-induced toxicity in rat thymocytes through mitochondrial survival pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 88, 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajput A. H., Uitti R. J., Stern W., Laverty W., O’Donnell K., O’Donnell D., Yuen W. K., Dua A. (1987). Geography, drinking water chemistry, pesticides and herbicides and the etiology of Parkinson’s disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 14, 414–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rcom-H’cheo-Gauthier A. N., Meedeniya A. C., Pountney D. L. (2017). Calcipotriol inhibits alpha-synuclein aggregation in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells by a Calbindin-D28k-dependent mechanism. J. Neurochem. 141, 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roede J. R., Hansen J. M., Go Y. M., Jones D. P. (2011). Maneb and paraquat-mediated neurotoxicity: Involvement of peroxiredoxin/thioredoxin system. Toxicol. Sci. 121, 368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roede J. R., Jones D. P. (2014). Thiol-reactivity of the fungicide maneb. Redox .Biol. 2, 651–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roede J. R., Uppal K., Park Y., Tran V., Jones D. P. (2014). Transcriptome-metabolome wide association study (TMWAS) of maneb and paraquat neurotoxicity reveals network level interactions in toxicologic mechanism. Toxicol. Rep. 1, 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semchuk K. M., Love E. J., Lee R. G. (1992). Parkinson’s disease and exposure to agricultural work and pesticide chemicals. Neurology 42, 1328–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S., Singh D., Kumar V., Chauhan A. K., Singh S., Ahmad I., Pandey H. P., Singh C. (2015). NADPH oxidase mediated maneb- and paraquat-induced oxidative stress in rat polymorphs: Crosstalk with mitochondrial dysfunction. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 123, 74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A. K., Ali W., Singh R., Bhui K., Tyagi S., Al-Khedhairy A. A., Srivastava P. K., Musarrat J., Shukla Y. (2012). Mancozeb-induced genotoxicity and apoptosis in cultured human lymphocytes. Life Sci. 90, 815–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R. N., Rogerio R., Zanin M. (1989). Maneb enhances MPTP neurotoxicity in mice. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 66, 167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E. R., Hurrell F., Shannon R. J., Lin T. K., Hirst J., Murphy M. P. (2003). Reversible glutathionylation of complex I increases mitochondrial superoxide formation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19603–19610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchelvam M., Richfield E. K., Baggs R. B., Tank A. W., Cory-Slechta D. A. (2000). The nigrostriatal dopaminergic system as a preferential target of repeated exposures to combined paraquat and maneb: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 20, 9207–9214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. B., Murray C. I., Chung H. S., Van Eyk J. E. (2013). Redox regulation of mitochondrial ATP synthase. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 23, 14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada A., Yamamoto K., Imamoto N., Momosaki S., Hosoi R., Yamaguchi M., Inoue O. (2009). Lactate is an alternative energy fuel to glucose in neurons under anesthesia. Neuroreport 20, 1538–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai D., Li S., Dong G., Zhou D., Yang Y., Wang X., Zhao Y., Yang Y., Lin Z. (2018). The correlation between DNA methylation and transcriptional expression of human dopamine transporter in cell lines. Neurosci. Lett. 662, 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Fitsanakis V. A., Gu G., Jing D., Ao M., Amarnath V., Montine T. J. (2003). Manganese ethylene-bis-dithiocarbamate and selective dopaminergic neurodegeneration in rat: A link through mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Neurochem. 84, 336–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.