Abstract

Purpose:

Ionizing radiation and high levels of circulating estradiol are known breast cancer carcinogens. We investigated the risk of first primary postmenopausal breast cancer in relation to the combined effects of whole-body ionizing radiation exposure and prediagnostic levels of postmenopausal sex hormones, particularly bioavailable estradiol (bE2).

Materials and Methods:

A nested case-control study of 57 incident breast cancer cases matched with 110 controls among atomic bomb survivors. Joint effects of breast radiation dose and circulating levels of sex hormones were assessed using binary regression and path analysis.

Results and Conclusions:

Radiation exposure, higher levels of bE2, testosterone and progesterone, and established reproductive risk factors were positively associated with postmenopausal breast cancer risk. A test for mediation of the effect of radiation via bE2 level suggested a small (14%) but significant mediation (p=0.002). The estimated interaction between radiation and bE2 was large but not significant (interaction=3.86; p=0.32). There is accumulating evidence that ionizing radiation not only damages DNA but also alters other organ systems. While caution is needed, some portion of the radiation risk of postmenopausal breast cancer appeared to be mediated through bE2 levels, which may be evidence for cancer risks due to both direct and indirect effects of radiation.

Keywords: breast cancer, hormones, estradiol, radiation, postmenopausal, interaction, mediation

Background

Evidence is accumulating that ionizing radiation not only damages DNA directly but also may act indirectly by altering immunologic, endocrinologic, and metabolic systems (Hayashi et al. 2005; Wong et al. 1999; Bezemer et al. 2005; Akahoshi et al. 2003). An unanswered fundamental question is whether observed systemic changes mediate part of the total effect, i.e., are biological factors in systems affected by radiation exposure helping to produce health endpoints typically associated solely with radiation effects?

Postmenopausal breast cancer has been associated with high levels of circulating estradiol. A number of factors can modulate a woman’s cumulative exposure or breast sensitivity to estradiol. Those factors include age at menarche, age at menopause, age at first delivery, parity, breast feeding, and BMI (see, for example, Russo & Russo (I. H. Russo & J. Russo 2011)).

Exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) is another well-established risk factor for breast cancer. IR can directly damage DNA and is a risk factor for breast cancer in atomic bomb survivors (Land, Hayakawa, Machado, Y. Yamada, Pike, Akiba & Tokunaga 1994a), women exposed to therapeutic radiation (Carmichael et al. 2003) or high diagnostic radiation (Howe & McLaughlin 1996; Boice et al. 1991), excessive environmental radiation (Bauer et al. 2005; Ostroumova et al. 2008), and occupationally-exposed women (Sigurdson et al. 2003; Preston et al. 2010). Land et al. showed that reproductive-history risk-related factors associated with lower cumulative exposure to estradiol (parity, earlier age at first birth, cumulative duration of lactation) are associated with a lower radiation risk and were able to statistically reject an additive model in favor of a multiplicative model for the joint effect of radiation and reproductive factors (Land, Hayakawa, Machado, Y. Yamada, Pike, Akiba & Tokunaga 1994b). Land et al. did not, however, measure endogenous hormones directly. Kabuto et al (Kabuto et al. 2000) measured bioavailable estradiol (bE2) and other hormones using stored sera, but were unable to see evidence of interaction between radiation and hormone levels using a log-linear model. The lower radiation risk among women with reduced exposure to endogenous estradiol coupled with lack of evidence for direct interaction between radiation and estradiol prompted us to examine in greater detail the joint effect of radiation and estradiol.

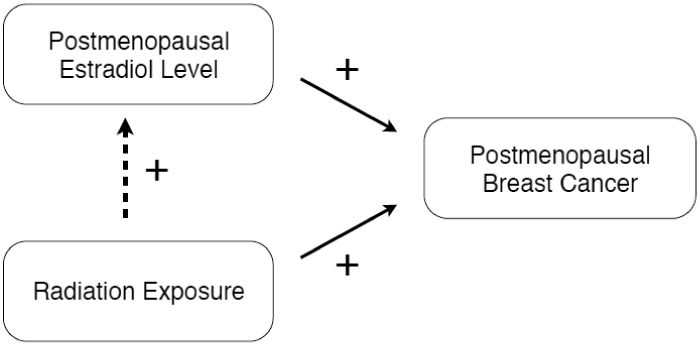

We recently found that postmenopausal serum hormone levels of bE2 were positively associated with radiation dose in cancer-free atomic bomb survivors, which could be an example of systemic effects occurring after radiation exposure (Grant et al. 2011). This finding raises the possibility that estradiol might act as a mediator of some proportion of the overall radiation risk of breast cancer. Therefore, our initial research question was whether the impact of radiation on the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer is mediated via raised levels of bE2 (see Figure 1). A second question was whether Land et al’s observation of multiplicative joint effects between reproductive-history factors and radiation exposure are also evident using postmenopausal levels of circulating sex hormones, primarily bioavailable estradiol (bE2). Women of the atomic bomb survivor cohort provide a unique opportunity to study these questions in a prospective setting among humans.

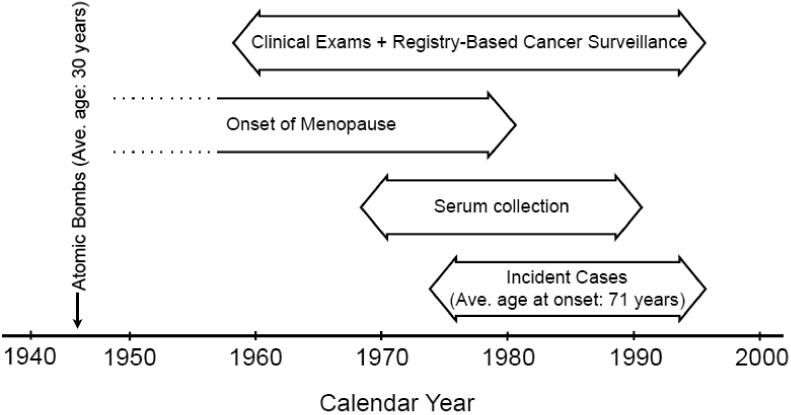

Figure 1.

Timeline of study. On average, subjects for this study were 30 years of age at the time of the bombings (1945) and 71 years of age at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer surveillance and clinical exams began in 1958. Serum collection began in 1969 and all samples were collected at least two years prior to diagnosis. Cases in this study were diagnosed between 1974 and 1996.

Methods

Study Design, Selection, and Eligibility

A nested case control design was employed (Langholz 2005). Study subjects were women selected from the Radiation Effects Research Foundation’s (RERF) Adult Health Study (AHS), a longitudinal cohort study with biennial clinical examinations of atomic bomb survivors initiated in 1958 (M. Yamada et al. 2004). Eligible women had stored sera, breast radiation dose estimates(Young & Kerr 2005), and were cancer-free for at least two years after serum collection (all sera were collected after menopause, see Determining menopausal status, below). Eligibility was further restricted to women who had no prior malignancies, were free from various hormone-related medical conditions, including oophorectomy, and did not have exogenous hormone treatment at the time of serum collection. The primary outcome was the diagnosis of a first-primary malignant breast cancer identified from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki cancer registries (Mabuchi et al. 1994).

Case selection

Originally, 171 first primary breast cancer cases (regardless of menopausal status) were identified. Samples could not be recovered for 19 cases and another 31 samples stored via freeze-drying were excluded due to unreliable reconstitution. Seventeen women who suffered a premenopausal breast cancer were excluded. Another 44 women did not have samples collected after menopause. Other cases were excluded for: no matching control (1), hormone treatment (1), and oophorectomy (1). The final dataset included 57 cases diagnosed with postmenopausal breast cancer.

Control selection

For selection of non-cases (for simplicity, “Controls”) in the nested case-control design, cohort risk-set-based (incidence-density) sampling was conducted from the cohort pool of all eligible women at risk at the time of each case’s diagnosis. Two control subjects were matched to each case on age (±2 years) and year (same decade) at serum collection, and city (Hiroshima vs. Nagasaki). Controls were counter matched on radiation dose to improve efficiency for studying joint effects of radiation and the serum markers given the low frequency of high doses among controls (Cologne, Sharp, et al. 2004). Three dose strata (low, medium, and high) were defined based on tertile cutpoints of 5 mGy and 790 mGy among cases. Each sampled risk set contained the case as well as one control from each of the two dose strata not occupied by the case. Some sets had less than two controls due to unrecoverable samples or determining that a sample was drawn before menopause. This sampling method does not preclude the possibility of a control being selected that could later become a case, however, in the period under surveillance, none of women selected as controls suffered a breast cancer. A total of 109 controls were selected (52 sets with two controls, 5 sets with only one control).

Determination of menopausal status

Menopausal status was determined using a conservative age range supplemented by an FSH (follicular stimulating hormone) assay. Samples collected at ages less than 43 were assumed to be from women who were premenopausal and not eligible; samples collected at age 55 and older were assumed postmenopausal (n=83 controls, n=44 cases). In the intermediate age range, serum FSH was measured and used to assign menopause status (n=27 controls, n=13 cases) based upon the manufacturer’s test guidelines and the investigators’ experience (postmenopausal cut-off: FSH >=23 mIU/ml) (SRL 2013).

Radiation Exposure

Radiation doses to the breast were based on the DS02 dosimetry system (Young & Kerr 2005), and were reported as weighted absorbed dose in gray (Gy) calculated as the gamma dose plus 10 times the neutron dose. Doses were adjusted to account for random errors as is routinely done within this cohort (Pierce et al. 1990).

Other data collection

Sera were stored in vials at −80°C. Samples were assayed for total estradiol, bioavailable estradiol (bE2, total estradiol concentration multiplied by the percent of estradiol free or loosely bound to albumin), testosterone, progesterone, prolactin, ferritin, and (if in the designated age range) FSH. All assays were performed blinded to outcome and radiation exposure. Commercial laboratories with internal quality assurance systems performed all assays. Self-reported data on menopause and reproductive factors were available from a series of in-clinic questionnaires and mailed questionnaires. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was measured at the time of serum collection. A full description of these methods is presented elsewhere (Grant et al. 2011) and a timeline of data collection is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Both Radiation exposure and postmenopausal level of estradiol are known breast cancer carcinogens. Previous findings indicated that radiation exposure can increase postmenopausal levels of estradiol in cancer-free women (dotted line). The research question is therefore whether estradiol mediates the radiation risk of postmenopausal breast cancer.

Methods of analysis

We used excess relative risk (ERR) models to estimate radiation risk (Thompson et al. 1994; Preston et al. 2007) with correction for the counter-matched sampling using a weighted analysis (Langholz & Borgan 1995). We used a binary odds model

where p is the probability of having breast cancer, zj(i) is a vector of other risk factors (including other hormones) or confounders for individual j in risk set i with corresponding vector of parameters δ, ηj(i) is the sampling weight (inverse of sampling probability from counter matching), and d j(i) is radiation dose. Risks for bE2 and other factors (apart from radiation dose) were estimated as natural log relative risks. Because of the risk set matching, model (1) is fit using conditional binary regression. Our primary risk model used to assess main effects of radiation and hormones, as well as interactions, was one with an excess relative risk for radiation and a log relative risk for natural-log-transformed bE2 level (dropping the subscript j(i) to simplify notation):

where β is the excess relative risk per Gy radiation dose, 𝛼 is the log of relative risk for a one-unit difference in natural-log-transformed bE2 level, and 𝛾 quantifies multiplicative statistical interaction between radiation and bE2 level. Lack of interaction corresponds to γ=0, but lack of mechanistic interaction is sometimes equated with additivity of effects. We therefore used a general (mixture) model to assess the relative goodness of fits of multiplicative and additive parameterizations for the joint effect of bE2 and radiation:

The left bracketed term represents a multiplicative parameterization while the right term is additive. Model (3) is similar to that used by Land et al (Land, Hayakawa, Machado, Y. Yamada, Pike, Akiba & Tokunaga 1994b). The conditional binary regression module “PECAN” of the Epicure software was used to fit the binary odds risk models (2) and (3) (Preston et al. 2015).

Causal modeling methods to assess mediation (Pearl 2009; Lange & Hansen 2011) cannot be immediately applied to counter-matched, nested case-control data. Therefore, to consider possible mediation of the effects of radiation through a bE2 pathway (Fig. 1), we used a classical path analysis comparing risks for radiation with and without concomitant adjustment for the potential mediator in the binary regression model (Hafeman & Schwartz 2009; Huang et al. 2004). The estimate of mediation proportion is the difference between non-adjusted and adjusted values of the ERR for radiation, divided by the non-adjusted ERR. This is a valid estimate of causal mediation proportion under an assumption of no interaction between exposure and mediator (VanderWeele & Vansteelandt 2010). We tested mediation nonparametrically by randomly permuting hormone values among the matched sets, maintaining case-control identity of the hormone values to preserve the main effect of estradiol (5000 permutations) (Good 2006). This permutation simulates the distribution of mediation proportion under the null hypothesis of no mediation because permuting the hormone values but not the doses negates the association between radiation and hormone level. We also conducted the permutation test with simultaneous adjustment for the other hormone values, in which case the entire set of hormone values as a unit was permuted among matched sets. Permutation tests of mediation were performed in R using the conditional binary regression function “clogit” for a logistic approximation to model (1) and the generalized nonlinear modeling function “gnm” for fitting model (2) (R Core Team 2014).

Biosamples were collected with oral informed consent in an era prior to that requiring explicit written informed consent. All current biosamples collection at RERF is performed using written informed consent. The RERF Human Investigation Committee approved this study. Privacy and confidentiality of subjects was regarded according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1. The average age at diagnosis of postmenopausal breast cancer was 70.7 years. Serum samples were collected an average of 11.6 years prior to diagnosis, and 11.7 years prior to the matched index case for controls.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| Characteristic (mean, SD, 5th percentile, 95th percentile) | Cases | Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 57 | 109 |

| 70.7 (9.6) | 70.4a (9.2) | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||

| 56.9, 89.5 | 56.0, 88.0 | |

| 30.2 (8.6) | 29.8 (8.2) | |

| Age at radiation exposure (years) | ||

| 14.0, 44.0 | 16.0, 43.0 | |

| 59.2 (7.7) | 58.9 (7.6) | |

| Age at sample collection (years) | ||

| 45.6, 72.7 | 45.9, 70.9 | |

| 11.6 (6.8) | 11.7a (6.7) | |

| Time from sample collection to case diagnosis (years) | ||

| 3.0, 24.0 | 3.3, 24.5 |

Values for controls calculated using their age at the time of the index case’s diagnosis

We examined the correlations between the log-transformed hormone levels. Only testosterone and progesterone had moderate correlations with bE2 (0.32 and 0.50, respectively). The only other correlations of note were IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 with a correlation value of 0.52 and progesterone and testosterone with a correlation of 0.25. All other correlations were low (absolute value ≤ 0.15).

Table 2 shows the distributions and univariate (crude, not adjusted for other factors) relative risks (RR) estimated using model (2) for breast cancer risk factors considered in this study. Significantly reduced risks were found for women who were older at menarche (RR=0.57 per year older; 95% CI: 0.34, 0.83, p=0.003) and who had more full term pregnancies (RR=0.71 per full term pregnancy; 95% CI: 0.55, 0.90; p=0.003), while a higher risk was observed per unit increase in BMI (1.12; 95%CI: 1.01, 1.25; p=0.035). Although other associated risks were not statistically significant, cases were more likely to be nulliparous (13% vs 8%), to be older than controls at menopause (48.8 vs 47.1 years), and older at time of first birth (23.3 vs 22.9 years).

Table 2.

Distributions and univariate relative risks of considered breast cancer risk factors.

| Factor | Mean value (SD) 5th percentile, 95th percentile Number with known data | Relative risk [95% CI] p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases N=57 | Non-cases N=109 | |||||

| Age at menarche (years) | 15.1 (1.7) | 15.5 (1.8) | 0.57a | |||

| 12, 18 | 13, 18 | [0.34, 0.83] | ||||

| 32 | 79 | p=0.003 | ||||

| Age at menopause (years) | 48.8 (4.0) | 47.1 (5.0) | 1.08a | |||

| 42, 53 | 40, 54 | [0.96, 1.23] | ||||

| 35 | 81 | p=0.22 | ||||

| Nulliparous (proportion) | 0.13 (0.34) | 0.08 (0.27) | 2.01b | |||

| – | – | [0.48, 9.12] | ||||

| 53 | 105 | p=0.34 | ||||

| Number of full-term pregnancies | 2.6 (1.9) | 3.4 (1.9) | 0.71a | |||

| 0, 6 | 0, 7 | [0.55, 0.90] | ||||

| 53 | 105 | p=0.003 | ||||

| Number of full-term pregnancies | Frequency (prop.) | Frequency | Heterogeneity P = 0.007 | |||

| 0 | (prop.) | |||||

| 7 (0.13) | 1.00 | (reference) | ||||

| 1 | 8 (0.08) | |||||

| 13 (0.25) | 1.69 | [0.31, 10.5] p>0.5 | ||||

| 2 | 7 (0.07) | |||||

| 8 (0.15) | 0.43 | [0.07, 2.44] p=0.34 | ||||

| 3 | 19 (0.18) | |||||

| 9 (0.17) | 0.17 | [0.02, 1.16] p=0.071 | ||||

| 4+ (mean 5.2) | 16 (0.30) | 25 (0.24) | 0.18 | [0.03, 0.95] p=0.043 | ||

| 46 (0.44) | ||||||

| Age at first full-term pregnancy | 23.3 (3.3) | 22.9 (3.5) | 1.07a | |||

| (years) | 20, 30 | 19, 30 | [0.94, 1.24] | |||

| 40 | 89 | p=0.30 | ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.3 (3.7) | 22.6 (3.3) | 1.12a,d | |||

| 17.0, 28.5 | 17.1, 28.3 | [1.01, 1.25] | ||||

| 54 | 103 | p=0.035 | ||||

| Body mass index categories (kg/m2) | Frequency (prop.) | Frequency (prop.) | Heterogeneity p=0.21 | |||

| < 20 | 11 (0.20) | 22 (0.21) | 1.70 | [0.53, 5.49] p=0.37 | ||

| 20, <22.5 | 12 (0.22) | 31 (0.30) | 1.00 | (reference) | ||

| 22.5, <25 | 12 (0.22) | 24 (0.23) | 1.72 | [0.49, 5.99] p=0.39 | ||

| 25, <27.5 | 11 (0.20) | 18 (0.17) | 2.79 | [0.81, 9.98] p=0.10c | ||

| ≥27.5 | 8 (0.15) | 8 (0.08) | 4.72 | [1.22, 19.4] p=0.025 | ||

| Biomarkers (serum) | ||||||

| Log bioavailable E2 (pg/ml) | 2.33 (0.73) | 2.12 (0.64)e | 2.04 | [1.07, 4.09] | p=0.029 | |

| Log testosterone (ng/dl) | 2.59 (0.50) | 2.38 (0.67)e | 1.85 | [1.06, 3.31] | p=0.030 | |

| Log progesterone (ng/ml) | −1.12 (0.47) | −1.34 (0.39)e | 6.31 | [2.27, 19.1] | P<0.000 | |

| Log prolactin (ng/ml) | 1.28 (0.57) | 1.21 (0.59)e | 1.08 | [0.60, 1.96] | p>0.5 | |

| IGF-1 (ng/ml) | 101.9 (45.8) | 112.1 (35.2)e | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.01] | p>0.5 | |

| IGFBP-3 (μg/ml) | 2.39 (0.47) | 2.45 (0.40)e | 0.86 | [0.38, 2.07] | p>0.5 | |

| Log ferritin (ng/ml) | 4.06 (0.88) | 3.93 (0.73)e | 1.34 | [0.88, 2.08] | p=0.18 | |

| Radiation dose (1 Gy) | 0.50 (0.89) | 0.33 (0.54)e | 1.61f | [1.00, 2.83] | P=0.049 | |

With continuous variables, the relative risk is multiplicative per increasing unit change. (For example, the RR is reduced by a factor of 0.57 for each year menarche is delayed. Therefore a women having menarche two years later than another women would have 32% [0.572 years = 0.32] the risk.)

Reference is one or more full-term deliveries [nulliparous estimate]

Relative risk for “overweight” (BMI> 25) is 3.43 (95% CI: 1.14, 11.1, p= 0.029.

A quadratic term in BMI was not significant (P>0.5).

Due to counter matching (stratified sampling of controls within risk sets), a weighted mean for non-case samples was computed using the risk-set-specific and stratum-specific sampling weights. Although only bioavailable E2 and testosterone have demonstrated relationships to radiation dose, due to some correlation between hormones, the weighted values are shown for all hormones in non-cases.

Calculated as ERR using Equation 1 (RR = ERR + 1). The ERR is additive per increasing unit change in dose. (For example, the ERR increases by an increment of 0.50 per Gy. Therefore a woman exposed to 2 Gy would have an ERR of 2.0 or a RR of 3.0.)

Mean radiation dose to the breast in cases was 0.50 Gy while mean dose in non-cases was 0.33 Gy (corrected for stratified counter-matching as explained in Footnote ‘e’ of Table 2). Radiation dose was significantly associated with breast cancer risk (ERR = 0.61/Gy; 95% CI: 0.00, 1.83; p=0.049 via model (2) with no interaction [γ=0] and no adjustment for other factors). Radiation risk declined slightly with increasing age at exposure and increasing attained age, as in previous analyses of the atomic bomb survivor cohort (Tokunaga et al. 1994; Preston et al. 2007), but neither effect modifier was statistically significant in this study (data not shown).

We assessed the breast cancer risk of individual hormone levels using model (2) with no adjustment for radiation dose. A significant increase in RR per unit increase in log bE2 was observed (RR=2.04; 95% CI: 1.04, 4.09; p=0.029). Unit increases in levels of both log testosterone and log progesterone showed positive, significant associations with breast cancer risk (RR=1.85 95% CI: 1.06, 3.31; p=0.030 and RR=6.31 95% CI: 2.27, 19.1; p<0.001, respectively). No significant associations with levels of log prolactin, IGF-1, IGFBP-3, or log ferritin were observed.

The relative change with radiation exposure of log bE2 levels at 1 Gy was 1.20 (95% CI: 0.98, 1.41; p=0.072) among cases and 1.19 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.34; p=0.010) among controls. The mean log bE2 was 2.33 pg/ml among cases (i.e. the geometric mean bE2 level was e2.33=10.3 pg/ml), while the mean log among controls was 2.12 pg/ml (adjusted for the radiation-related sampling due to the association between radiation and bE2 levels among cancer-free women).

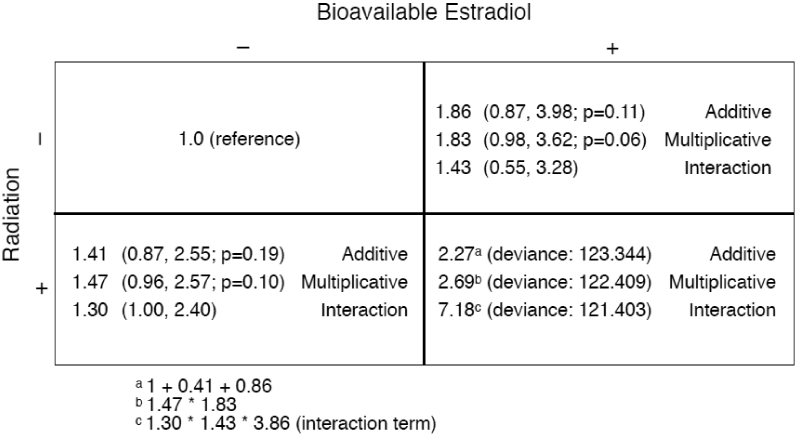

We analyzed the joint effects of radiation and bE2 using the mixture model (3) to investigate if an additive or multiplicative model best fit the data. Setting the mixture parameter (θ) to 0 produces estimates for a pure additive model (deviance 123.344) while a pure multiplicative model (θ=1) fit slightly better (deviance 122.409). An interaction model (2) was used to test whether bE2 significantly modified the radiation response (i.e. γ≠0). The estimate of the interaction term was large and positive (3.86; 95% CI: 0.27, >2000; p=0.32), suggesting a super-multiplicative joint effect, but was not significant (deviance 121.403). Main and joint relative risks estimated from these three models are shown using a 2×2 table layout in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Two-by-two representation of the joint effects of bioavailable estradiol and radiation exposure based on additive, multiplicative and interaction models. Estradiol levels in the reference group (“−”) were the geometric mean among the control subjects and the level in the “exposed” group (“+”) was one log unit above the geometric mean (i.e. 2.72-times higher on a linear scale). Radiation dose in the unexposed group was 0 Gy, and it was 1 Gy for the “exposed” group. The main effects were estimated using additive, multiplicative, and interaction models (without adjustment for other variables), and then the respective joint effects were manually calculated (see footnotes) and displayed in the bottom-right quadrant. The smallest deviance was observed using the interaction model.

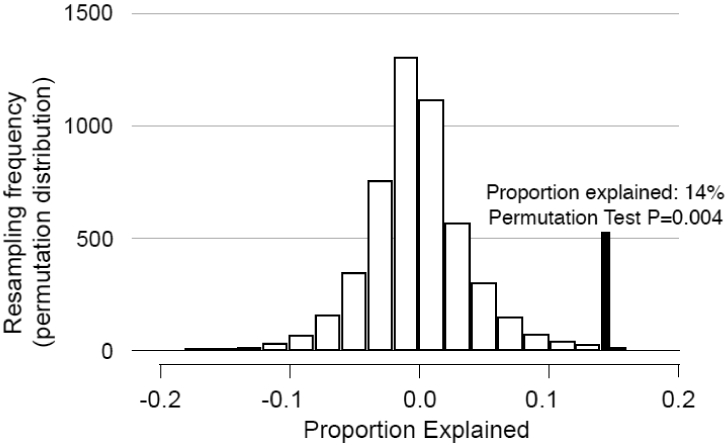

Based on model (2) without interaction, the mediation (proportion of total radiation risk explained by bE2) on the log RR scale (log RR = log[1+ERR]) was 14% (ERR was 0.467 with adjustment for log bE2, 0.605 without). The permutation test p-value was 0.004. Analogous tests of mediation of the log RR for radiation by testosterone, progesterone, and prolactin (without adjustment for bE2 or other hormones) conducted post-hoc revealed 17% (p=0.005), 11% (p=0.12), and 0.8% (p=0.21) decreases, respectively. With further adjustment for these other hormones there was no evidence of mediation by bE2 (0.2% decrease in log RR for radiation; p=0.47).

Discussion

Ionizing radiation and high levels of bE2 are known breast cancer (BC) risk factors. The atomic bomb survivor cohort provides a rare opportunity to study these factors simultaneously in humans. We observed that 1 Gy of ionizing radiation exposure to the breast raised the risk of postmenopausal BC risk by about 60%. A higher level of postmenopausal bE2 was also associated with increased risk of postmenopausal BC. The effects of traditional BC risk factors conformed to expectations, although—as might be expected in a study of this size—not all were statistically significant. The joint effects of IR and bE2 were statistically consistent with both additive and multiplicative models; it is known that power to discriminate the scale of joint effects can be low (Cologne, Pawel, et al. 2004; Greenland 1983). While not statistically significant, the point estimate of the interaction term and the results from the mixture model both indicated that a multiplicative model provided a slightly better fit.

In a previous study of female cancer-free atomic bomb survivors, we found that radiation exposure was associated with higher levels of bE2 in 199 postmenopausal samples (Grant et al. 2011). In the present study, in which the controls are a subset of the previous study, we observed a similar effect of radiation on bE2 level among both cases and controls, although they were not statistically significant. Using a classical path analysis we observed a modest decrease (14%) in the risk of radiation exposure after adjusting for postmenopausal bE2 level, indicating that bE2 level may have a mediating effect upon the radiation risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Although a classical path analysis is not ideal for assessing mediation with fundamentally nonlinear regression models such as those used for cohort or case-control analyses (Lange et al. 2012), the counter-matched nested case-control design employed in the present study prohibits immediate application of more appropriate methods of mediation analysis. This is a topic of ongoing methodological work.

There is a strong consensus that the direct pathway for increased risk of solid cancer (including breast cancer) after radiation exposure is DNA damage, particularly double strand breaks, which are often repaired with error-prone mechanisms that lead to deletion mutations and genomic instability. There is also a body of knowledge showing that systems within the body can be altered by radiation exposure (i.e., indirect effects). Examples include changes in immune response resulting in a decline of T-cell immunity leading to increased inflammation (Hayashi et al. 2005), altered lipid metabolism (Wong et al. 1999; Bezemer et al. 2005; Akahoshi et al. 2003), and increased fatty liver and hypertension, among others (M. Yamada et al. 2004). There is evidence that indirect effects contribute to increased risks of non-cancer diseases and circulatory-related mortality (Shimizu et al. 2010; Ozasa et al. 2012). Mediation, such as that by estradiol suggested in the present study, may therefore be an aspect of radiation carcinogenesis requiring further investigation.

The results of the present study are generally consistent with the findings of Land et al, (Land, Hayakawa, Machado, Y. Yamada, Pike, Akiba & Tokunaga 1994b) who noted that radiation exposure interacted with reproductive factors that act to reduce overall exposure to high levels of endogenous sex hormones and/or reduce the number of undifferentiated mammary gland cells that are sensitive to sex hormones and radiation damage. Brooks et al. described higher risk of contralateral breast cancer if the woman was nulliparous at the time of radiation treatment for the initial breast cancer while women who were parous showed no additional risks (Brooks et al. 2012). Pregnancy is thought to protect the breast against cancer due to the advancement of undifferentiated breast lobules to more developed ones (J. Russo et al. 2005). Studies exploring the effects of reproductive status at the time of exposure have reported varying findings. Holmberg reported no interaction of radiation risks and fertility patterns for breast cancer risk among women who had been irradiated for skin hemangiomas in infancy (Holmberg 2001). Ronckers et al. failed to see a difference in BC risk among women with scoliosis exposed to diagnostic X-rays at different reproductive development periods (Ronckers et al. 2008) while McDougall et al. did not see a hypothesized increase in BC risk among atomic bomb survivors exposed between menarche and first birth compared to other developmental periods (McDougall et al. 2010). Hill et al. found higher risks of BC among women treated during pregnancy for Hodgkin lymphoma (Hill et al. 2005).

An early rat study indicated synergistic effects of estradiol and IR (Segaloff & Maxfield 1971). In another study, rats that underwent ovariohysterectomy showed no radiation risks compared to normal rats, while those treated with estradiol showed higher radiation risks (Solleveld et al. 1986). Pedram et al (Pedram et al. 2009) suggested a possible mechanism whereby estradiol interferes with the signalling and cell cycle checkpoint processes that occur after DNA damage, which may partially explain a synergistic interaction between bE2 and radiation exposure.

There are several limitations to this study. The number of cancer cases is small, levels of mediation were modest, and power to assess effect modification was limited. Menopausal status at time of sample collection was based on age and FSH level. FSH has been shown to be not fully specific (Henrich et al. 2006) so some misclassification of menopause status among the 25% of samples that were assigned using FSH is possible. Mediation analysis for dichotomous outcome data can produce misleading results if there is interaction between the exposure and mediator. Generalizability of the findings may be limited due to the fact that the subjects received whole-body exposure, which is different than exposures to the breast during mammograms for breast cancer screening. Another generalizability issue is the fact that these women survived at least 25 years after an acute whole-body exposure prior to having sera collected. To perform the permutation tests, we used either conditional logistic regression or unconditional nonlinear binary odds regression, but all approaches gave similar results.

The study has several important strengths. Most notably, it was prospective with biosamples collected uniformly for all members of the cohort regardless of outcome or exposure, and prior to diagnosis for cases. Dosimetry is exceptionally reliable for a population-based study. Inferences concerning hormonal involvement were based on sera measurements rather than self-reported reproductive factors. Permutation tests are non-parametric and do not rely on any particular assumed distribution for the test statistic (Good 2006).

Conclusions

This study of women exposed to atomic bomb radiation shows increased risk of postmenopausal breast cancer due to radiation as well as to circulating levels of bE2. A portion of the risk of radiation exposure appeared to be mediated by bE2 levels. Estimates of the joint effects of radiation and bE2 provided only equivocal evidence regarding effect modification by bioavailable estradiol levels. This is the first direct epidemiologic evidence of hormonal effects on the magnitude of radiation-induced breast cancer risk; the finding requires replication and possibly further elucidation by genomic and metabolomic studies in radiation-exposed cohorts.

Figure 4.

Results of a permutation test to determine if the effects of radiation were mediated through changes in the level of bioavailable estradiol (bE2). Hormone values were randomly permuted (5000 permutations) among case-control sets maintaining case status of the values; this preserves the main effects of bE2 levels and radiation while rendering bE2 levels random with respect to radiation dose (which would be true under the null hypothesis of no mediation). The distribution of the proportion explained is shown ([log(radiation risk) - log(radiation risk after adjustment of bE2))] ∕ log(radiation risk)). The solid line shows the actual proportion explained in the dataset (14%), which was outside of the expected range at a p-level of 0.004 (via permutation testing). This indicates that there was statistically significant evidence of mediation of the radiation risk via bE2 level changes.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the women of the AHS study for graciously donating biosamples. We also thank Dr. Roy Shore for his many helpful comments and suggestions and Dr. Kazuo Neriishi for his assistance and advice. The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan is a public interest foundation funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the US Department of Energy (DOE). The research was also funded in part through DOE award DE-HS0000031 to the National Academy of Sciences, and by US National Cancer Institute contracts HHSN261200900005C and HHSN261201400009C, and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology grants 14031227 and 15026220, and 25330039 (S Izumi). The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect those of the two funding governments.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest

References

- Akahoshi M et al. , 2003. Effects of radiation on fatty liver and metabolic coronary risk factors among atomic bomb survivors in Nagasaki. Hypertension research: official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension, 26(12), pp.965–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S et al. , 2005. Radiation exposure due to local fallout from Soviet atmospheric nuclear weapons testing in Kazakhstan: solid cancer mortality in the Semipalatinsk historical cohort, 1960–1999. Radiation Research, 164(4 Pt 1), pp.409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezemer ID et al. , 2005. C-peptide, IGF-I, sex-steroid hormones and adiposity: a cross-sectional study in healthy women within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Cancer Causes & Control, 16(5), pp.561–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boice JD et al. , 1991. Frequent chest X-ray fluoroscopy and breast cancer incidence among tuberculosis patients in Massachusetts. Radiation Research, 125(2), pp.214–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JD et al. , 2012. Reproductive status at first diagnosis influences risk of radiation-induced second primary contralateral breast cancer in the WECARE study. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics, 84(4), pp.917–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael A, Sami AS & Dixon JM, 2003. Breast cancer risk among the survivors of atomic bomb and patients exposed to therapeutic ionising radiation. European journal of surgical oncology: the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology, 29(5), pp.475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cologne JB, Pawel DJ, et al. , 2004. Uncertainty in estimating probability of causation in a cross-sectional study: joint effects of radiation and hepatitis-C virus on chronic liver disease. Journal of radiological protection, 24(2), pp.131–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cologne JB, Sharp GB, et al. , 2004. Improving the efficiency of nested case-control studies of interaction by selecting controls using counter matching on exposure. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(3), pp.485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good PI, 2006. Resampling Methods 3rd ed, Boston: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar]

- Grant EJ et al. , 2011. Associations of ionizing radiation and breast cancer-related serum hormone and growth factor levels in cancer-free female A-bomb survivors. Radiation Research, 176(5), pp.678–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, 1983. Tests for interaction in epidemiologic studies: a review and a study of power. Statistics in medicine, 2(2), pp.243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman DM & Schwartz S, 2009. Opening the Black Box: a motivation for the assessment of mediation. International Journal of Epidemiology, 38(3), pp.838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T et al. , 2005. Long-term effects of radiation dose on inflammatory markers in atomic bomb survivors. The American journal of medicine, 118(1), pp.83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich JB et al. , 2006. Limitations of follicle-stimulating hormone in assessing menopause status: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999–2000). Menopause (New York, NY), 13(2), pp.171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DA et al. , 2005. Breast cancer risk following radiotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma: modification by other risk factors. Blood, 106(10), pp.3358–3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg E, 2001. Excess breast cancer risk and the role of parity, age at first childbirth and exposure to radiation in infancy. British journal of cancer, 85(3), pp.362–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GR & McLaughlin J, 1996. Breast cancer mortality between 1950 and 1987 after exposure to fractionated moderate-dose-rate ionizing radiation in the Canadian fluoroscopy cohort study and a comparison with breast cancer mortality in the atomic bomb survivors study. Radiation Research, 145(6), pp.694–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B et al. , 2004. Statistical assessment of mediational effects for logistic mediational models. Statistics in medicine, 23(17), pp.2713–2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabuto M et al. , 2000. A prospective study of estradiol and breast cancer in Japanese women. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention, 9(6), pp.575–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land CE, Hayakawa N, Machado SG, Yamada Y, Pike MC, Akiba S & Tokunaga M, 1994a. A case-control interview study of breast cancer among Japanese A-bomb survivors. I. Main effects. Cancer Causes & Control, 5(2), pp.157–165. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=pubmed&Cmd=Retrieve&list_uids=8167263&dopt=abstractplus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land CE, Hayakawa N, Machado SG, Yamada Y, Pike MC, Akiba S & Tokunaga M, 1994b. A case-control interview study of breast cancer among Japanese A-bomb survivors. II. Interactions with radiation dose. Cancer Causes & Control, 5(2), pp.167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange T & Hansen JV, 2011. Direct and indirect effects in a survival context. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass), 22(4), pp.575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange T, Vansteelandt S & Bekaert M, 2012. A simple unified approach for estimating natural direct and indirect effects. American Journal of Epidemiology, 176(3), pp.190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langholz B, 2005. Case-Control Study, Nested. In Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. pp. 646–655. [Google Scholar]

- Langholz B & Borgan OR, 1995. Counter-matching: A stratified nested case-control sampling method. Biometrika, 82(1), pp.69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mabuchi K et al. , 1994. Cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors. Part I: Use of the tumor registries in Hiroshima and Nagasaki for incidence studies. Radiation Research, 137(2 Suppl), pp.S1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall JA et al. , 2010. Timing of menarche and first birth in relation to risk of breast cancer in A-bomb survivors. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 19(7), pp.1746–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroumova E et al. , 2008. Breast cancer incidence following low-dose rate environmental exposure: Techa River Cohort, 1956–2004. British journal of cancer, 99(11), pp.1940–1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozasa K et al. , 2012. Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors, Report 14, 1950–2003: an overview of cancer and noncancer diseases. Radiation Research, 177(3), pp.229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J, 2009. Causal inference in statistics: An overview. Statistics Surveys, 3, pp.96–146. [Google Scholar]

- Pedram A et al. , 2009. Estrogen inhibits ATR signaling to cell cycle checkpoints and DNA repair. Molecular biology of the cell, 20(14), pp.3374–3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce DA, Stram DO & Vaeth M, 1990. Allowing for random errors in radiation dose estimates for the atomic bomb survivor data. Radiation Research, 123(3), pp.275–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston DL et al. , 2015. Epicure User Guide 12 ed, Ottawa: Risk Sciences International. [Google Scholar]

- Preston DL et al. , 2010. How much can we say about site-specific cancer radiation risks? Radiation Research, 174(6), pp.816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston DL et al. , 2007. Solid Cancer Incidence in Atomic Bomb Survivors: 1958–1998. Radiation Research, 168(1), pp.1–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2014. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2nd ed., Vienna, Austria: Available at: http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Ronckers CM et al. , 2008. Multiple diagnostic X-rays for spine deformities and risk of breast cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention, 17(3), pp.605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo IH & Russo J, 2011. Pregnancy-induced changes in breast cancer risk. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia, 16(3), pp.221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo J et al. , 2005. The protective role of pregnancy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research, 7(3), pp.131–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segaloff A & Maxfield WS, 1971. The synergism between radiation and estrogen in the production of mammary cancer in the rat. Cancer research, 31(2), pp.166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y et al. , 2010. Radiation exposure and circulatory disease risk: Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivor data, 1950–2003. British Medical Journal, 340(jan14 1), pp.b5349–b5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdson AJ et al. , 2003. Cancer incidence in the US radiologic technologists health study, 1983–1998. Cancer, 97(12), pp.3080–3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solleveld HA et al. , 1986. Effects of X-irradiation, ovariohysterectomy and estradiol-17 beta on incidence, benign/malignant ratio and multiplicity of rat mammary neoplasms–a preliminary report. Leukemia research, 10(7), pp.755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRL (Tokyo Special Reference Laboratories, Inc) 2013, 卵胞刺激ホルモン (FSH) 基準値 [Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) reference levels]. Available at: http://www.srl.info/srlinfo/kensa_ref_CD/otherdata/06-6118.html [Accessed October 24, 2013].

- Thompson DE et al. , 1994. Cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors. Part II: Solid tumors, 1958–1987. Radiation Research, 137(2 Suppl), pp.S17–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga M et al. , 1994. Incidence of female breast cancer among atomic bomb survivors, 1950–1985. Radiation Research, 138(2), pp.209–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ & Vansteelandt S, 2010. Odds ratios for mediation analysis for a dichotomous outcome. American Journal of Epidemiology, 172(12), pp.1339–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong FL et al. , 1999. Effects of radiation on the longitudinal trends of total serum cholesterol levels in the atomic bomb survivors. Radiation Research, 151(6), pp.736–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M et al. , 2004. Noncancer disease incidence in atomic bomb survivors, 1958–1998. Radiation Research, 161(6), pp.622–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RW & Kerr GD eds., 2005. Reassessment of the Atomic Bomb Radiation Dosimetry for Hiroshima and Nagasaki - Dosimetry System 2002, Hiroshima: Radiation Effects Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]