Abstract

A divergent strain of Rickettsia japonica was isolated from a Dew’s Australian bat argasid tick, Argas (Carios) dewae, collected in southern Victoria, Australia and a full-genome analysis along with sequencing of 5 core gene fragments was undertaken. This isolate was designated Rickettsia japonica str. argasii (ATCC VR-1665, CSUR R179).

Keywords: Rickettsia, japonica, Australia, Argas, Carios, bat

1. Introduction

The importance of bats as reservoir hosts and vectors of emerging infectious pathogens is becoming increasingly recognised. However, it is typically not until these pathogens “spill over” into humans or domestic livestock that public interest and research funding into the pathogen increases (Calisher et al., 2006). In addition, previous and ongoing research has predominantly focused of viral pathogens, whilst the prevalence of bacterial pathogens and their potential impact continues to be largely neglected (Calisher et al., 2006). A number of studies have detected spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsial antibodies in the blood serum of insectivorous bats (Mühldorfer, 2013), and when experimentally infected, Ornithodoros spp. ticks were able to transmit R. rickettsii to susceptible animals (Parola et al., 2013).

Worldwide, the presence of SFG rickettsiae in argasid ticks is significantly underrepresented compared to their hard bodied counterparts (Brites-Neto et al., 2015) with only a comparatively small number of articles reporting the presence of SFG rickettsiae in Argas spp. Ornithodoros spp. and Carios spp. ticks (Loftis et al., 2005; Cutler et al., 2006; Reeves et al., 2006; Duh et al., 2010; Socolovschi et al., 2012; Milhano et al., 2014; Lafri et al., 2015; Tahir et al., 2016).

To date four characterised and two ‘Candidatus’ SFG rickettsial species have been identified in Australia; R. australis (Queensland tick typhus) (Andrew et al., 1946), R. honei (Flinders Island spotted fever) (Stewart, 1991), R. felis (cat flea typhus) (Schloderer et al., 2006), R. gravesii (Owen et al., 2006), ‘Candidatus R. antechini’ (Owen et al., 2006) and ‘Candidatus R. tasmanensis’ (Izzard et al., 2009). The primary vectors for 5 of the 6 species are hard ticks, Ixodidae spp., the exception being R. felis, which is detected in the cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and identification of ticks

Ticks were collected from the roosting boxes of microbats, primarily Chalinolobus gouldii and Vespadelus spp., during routine monitoring of colonies within Organ Pipes National Park (OPNP) in southern Victoria, Australia (Figure 1). Ticks were removed from the nesting boxes using plastic specimen collection tubes containing damp gauze cloth to avoid subsequent dehydration. Care was required when handling as the soft ticks were very susceptible to mechanical damage. Ticks were identified using the dichotomous identification key found in the book Australian Ticks by F.H.S. Roberts (1970).

Figure 1.

Representative image of the Argas (Carios) dewae ticks collected from the roosting boxes of Chalinolobus gouldii and Vespadelus spp. bats.

2.2. Rickettsial isolation and culture

The ticks were initially washed in 70% ethanol, followed by a rinse in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and then homogenized. The homogenate was then filtered using a 0.45 μm sterile syringe filter (Millex, USA), to remove the tick debris and any other larger bacteria. The smaller rickettsial cells were small enough to pass through the filter. The filtrate was divided, with half subjected to DNA extraction for initial real time PCR and sequencing of 1098 base pairs of the gltA gene for species determination and the other half added to confluent T25 flask of VERO cells. Cultures were incubated at 34° C, no CO2, in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 4 mM L-Glutamine and 3% foetal calf serum. After 30 days the cell culture was tested for the presence of a rickettsial agent using real time PCR and the resulting isolate was submitted to the ATCC (VR-1665) and CSUR (CSUR R179).

2.3. DNA extraction from tick homogenates and cultured bacterial samples

2.3.1. Gene segment analysis

DNA from the tick homogenates and isolated agent were extracted using a QIAmp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) using the manufactures instructions. Briefly, 200 μL of sample was combined with 200 μL of buffer AL and incubated at 56°C for 10 min. Next, 200 μl of glacial ethanol was added and the mix was added to a DNeasy spin column and briefly centrifuged. The column was then washed first with 500 μl of Buffer AW1, followed by 500 μl of Buffer AW2. Finally, the DNA was eluted from the column using 200 μl of AE elution buffer.

2.3.2. Full genome analysis

DNA from the isolate was also prepared for whole-genome sequencing using a modified version of the Gentra PureGene (Qiagen) Gram Negative Bacteria method. Briefly, the isolate was grown in flasks containing confluent Vero cells. The cells were detached, pelleted, and then disrupted by vortexing with 400 μM glass beads. The supernatant was filtered using a 2 μm filter, followed by a 1 μm filter, then incubated with DNAse (Brand) to remove contaminating host DNA. The bacterial agent was washed 3 times by centrifuging at 11,000 × g for 5 min and re-suspending in 300 μM sucrose solution. The DNA was then extracted as per the Gentra PureGene (Qiagen) Gram Negative Bacteria protocol.

2.4. Real time PCR detection of rickettsial agents in tick samples

All tick homogenates were subjected to real time PCR to screen for the presence of Rickettsia spp. using a previously described citrate synthase (gltA) specific assay (Baird, Lloyd et al. 1992).

Briefly, a 25 μL qPCR mix was prepared containing 2XPIatinum® qPCR SuperMix-UDG Mastermix (Invitrogen, Australia), 200 nM of each primer and probe, 5 mM MgCl2, and extracted DNA. Extracted DNA from cultured R. australis was added to one tube as a positive control and water was added to a second tube as a ‘no template control’ (NTC). The qPCR reaction was performed in a Rotor-Gene 3000 (Corbett Research, Australia), with an initial 3 min 50°C incubation, followed by a 95°C for 5 min. After this the temperature was cycled 60 times; first with a 95°C denaturation step for 20 s, followed by a 60°C annealing step for 40 s.

2.5. Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of gene segments

1419, 1098, 514, 4899, and 2876 base pairs of the rrs, gltA, rOmpA, rOmpB, and sca4 genes respectively was amplified using primers that have been previously described (Fournier et al., 2003). Sequencing of the amplicons using BigDye v3.1 technology was performed using a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, USA). The product was then analyzed using an ABI Prism 3730×l DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA) at the Australian Genomic Research Facility.

Sequencing traces were assembled in the DNASTAR software package (DNASTAR, Inc. USA) and analysed using BLAST analysis software (NCBI) (Altschul et al., 1990). All sequences have been deposited in GenBank (Table 1). A concatenated tree of the 5 sequences was generated using neighbor-joining and maximum parsimony methods in the MEGA 7 software package.

Table 1.

GenBank accession numbers of Rickettsia japonica str. argasii.

| Gene | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|

| rrs | JQ727684.1 |

| gltA | JQ727682.1 |

| rOmpA | JQ727681.1 |

| rOmpB | JQ727680.1 |

| sca4 | JQ727683.1 |

2.6. Genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

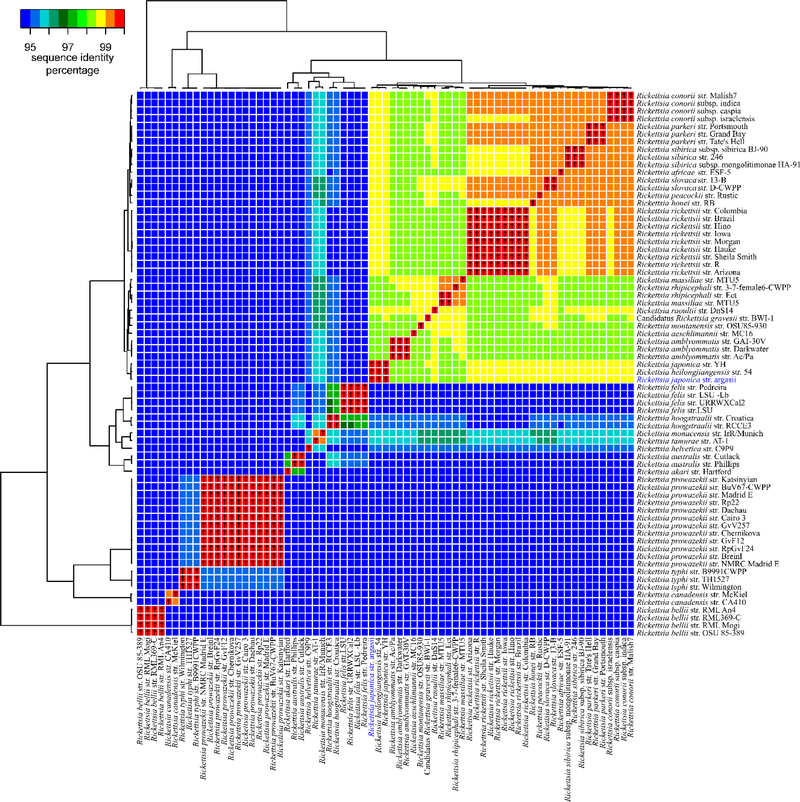

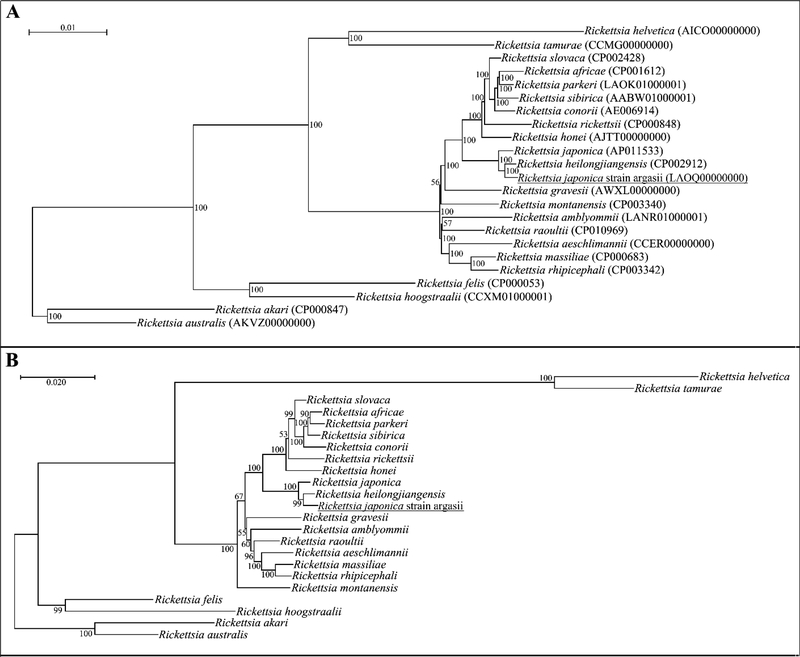

The genome of the isolate was sequenced by University of Maryland School of Medicine using Illumina next generation sequencing technology. The complete or draft sequences of 72 Rickettsia spp. genomes, including the isolate, were downloaded from NCBI GenBank (Benson et al., 2013) and aligned using the multiple whole-genome aligner, Mugsy v2.1 (Angiuoli and Salzberg, 2011). The core genome alignment, consisting of only the nucleotide base pairs present in all 72 genome sequences, was obtained and concatenated using MOTHUR v1.22 (Schloss et al., 2009). The resulting 502,279 bp alignment was used to generate a sequence identity matrix using BioEdit software (www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html) (Figure 2). In addition, the alignment was used to generate a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree using RAxML v8.2.0, using a GTRGAMMA model and 100 bootstraps (Stamatakis, 2014), and was viewed using Dendroscope 3 (Huson and Scornavacca, 2012) (Figure 3A).

Figure 2.

A heat-map of 72 genome sequences showing the level of conservation both within and across different species. The cross (✝) symbol indicates a pairwise sequence identity of ≥99.6% between two sequences. Dendrograms across the top and left of the map show the relationship between different genome sequences.

Figure 3.

(A) A phylogenetic tree prepared using the maximum-likelihood method from a 502,279 bp concatenated core genome alignment. Bootstrap values are indicated at each node. Scale bar indicates the nucleotide divergence represented by the branch length. (B) A phylogenetic tree prepared using the neighbor-joining method from a concatenated sequence of all five gene segments (rrs, gltA, rOmpA, rOmpB and sca4) of Rickettsia japonica str. argasii. Bootstrap values are indicated at each node. Scale bar indicates the nucleotide divergence represented by the branch length.

3. Results

3.1. Tick identification, detection and isolation of rickettsial agents

A rickettsial agent was isolated from Dew’s Australian bat argasid ticks, Argas (Carios) dewae, a soft tick from the family Argasidae (Figure 1). Rickettsial DNA was detected in 7 (70%) of 10 ticks by using a gltA-specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay (Stenos et al., 2005). The majority of the ticks collected were female, so no correlation between the sex of the ticks and presence of rickettsia could be determined.

3.2. Gene segment phylogenetic analysis

The 5 gene sequences from the novel isolate were compared to other validated rickettsia species using NCBI BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990). The sequences aligned closest to R. heilongjiangensis for the gltA, rOmpB and rOmpA, with sequence identities of 99.5% (1093bp/1098bp), 98.7% (4836bp/4899bp) and 98.2% (505bp/514bp) respectively, while the rrs and sca4 genes aligned closest to R. japonica, with sequence identities of 99.9% (1418bp/1419bp) and 99.2% (2854bp/2876bp) respectively. Gene sequence analyses using the neighbor-joining algorithm was undertaken for all five genes, with a concatenated tree shown below (Figure 3B).

Phylogenetic analysis using the original 5 gene fragments, concatenated sequence or whole-genome sequence, all resulted in the isolate consistently aligning within the R. japonica and R. heilongjiangensis cluster. The criteria defined by Fournier et. al. (2003) states that for a rickettsial agent to be considered a new species it must not have more than one gene that exhibits a degree of “nucleotide similarity with the most homologous validated species” of equal to or greater than 99.9%, 99.8%, 99.3%, 99.2% and 98.8% for the gltA, rrs, sca4, rOmpB and rOmpA genes (Fournier et al., 2003). Rickettsia japonica str. argasii exhibited percentage identities of 99.9%, 99.5%, 99.2%, 99.1% and 98.1% for the rrs, gltA, sca4, rOmpB, and rOmpA, so by these criteria, only the rrs gene of the isolate was within the percent nucleotide identity threshold, and therefore, satisfies the requirements for classification as a new species.

3.3. Genome phylogenetic analysis

Using the complete or draft genome sequences of 71 Rickettsia spp., a identity matrix was calculated for all pairwise comparisons, and the lowest identity was identified within each of the twenty-nine different Rickettsia species examined. The isolate showed greatest identity to R. heilongjiangensis (99.7%) and R. japonica (99.6%) while the pairwise identity between R. heilongjiangensis and R. japonica was also 99.6%. Therefore, a pairwise identity of >99.7% was chosen as an arbitrary ‘species cutoff as this was the level of identity between the isolate and the validated species R. heilongjiangensis. Of the 15 species analyzed that had genome sequences of more than one strain available, only 8 (53%) had strain pairwise comparisons with >99.7% identity in the core genome alignment; R. amblyommatis (99.8%), R. australis (99.9%), R. felis (99.9%), R. parkeri (99.9%), R. prowazekii (99.9%), R rickettsii (99.9%), R. slovaca (99.9%) and R. typhi (99.9%). Interestingly, nearly half (7) of the 15 species had strain pairwise comparisons where at least one pair had ≤99.7% identity: R. bellii (99.7%), R. canadensis (99.4%), R. conorii (99.6%), R. hoogstraalii (99.7%) R. massiliae (99.5%), R rhipicephali (99.3%), and R. sibirica (99.7%). Of these 7 species, three had pairwise similarities between strains lower than the percent identity between the isolate and either R. heilongjiangensis (99.7%) or R.japonica (99.6%). Of note, they were also lower than the percent identity between R. heilongjiangensis and R. japonica (99.6%). However, when the species cutoff threshold is dropped to 99.6%, which then incorporates R. heilongjiangensis, R. japonica and the isolate within the same species, the number of total species whose strains all fall within the new threshold increases to 12 of 15 (80%) (figure 3). Therefore, while the new isolate fulfills Fournier’s criteria for classification as a novel species, the additional information provided by genome analysis leads to the view that this isolate is more likely a divergent strain of R. japonica as opposed to a novel species. In addition, we believe that R heilongjiangensis most likely also falls under this category and should also potentially be reclassified as a strain of R. japonica.

4. Discussion

When comparing individual genes, the concatenated results and whole-genome sequences, Rickettsia japonica str. argasii consistently clustered with R. heilongjiangensis and R.japonica, both of which are known to cause disease in humans (Uchida et al., 1992; Mediannikov et al., 2009; Aung et al., 2014). This, combined with the knowledge that several members of the Argas spp. are known to aggressively feed on humans (Estrada-Pena and Jongejan, 1999; Otranto et al., 2014; Aubry et al., 2016) suggests that this new rickettsial isolate has the potential to impact human health in the region.

Based on the traditional phylogenetic results, combined with both the novel vector and its remote geographic location compared to R. heilongjiangensis and R. japonica, we would have normally considered this isolate be a novel species. However, the original phylogenetic methodology compares less than 1% of the genome between Rickettsia species, while the addition of full genome sequencing, allowed a comparison with approximately 40% of the genome between species, and it is from these results that it appears that this new isolate is in fact a divergent strain of R. japonica and that it is likely that R. heilongjiangensis and R. japonica are in fact one species. We propose to nominate this rickettsial isolate a novel strain of R. japonica and name it Rickettsia japonica str. argasii after the tick vector from which it was isolated.

As the range of this study was limited to a single location in central Victoria, it would be useful to examine A. dewae ticks from roosting boxes in other locations in Victoria, and throughout Australia, for the presence of this rickettsial agent to help elucidate the true geographical range of this species. The pathogenicity of this strain is currently unknown, as it has currently only been isolated from its arthropod vector. However, as mentioned above, this isolate clustered R. heilongjiangensis and R. japonica, both of which are known to infect humans. This knowledge combined with the fact that other member of the Argas spp. are known to aggressively feed on humans means that the potential exposure risk of this agent should not be disregarded. Pathogenicity studies are required to ascertain its full impact on public health. The likelihood of this agent being present elsewhere is high as the vector of this organism A. dewae is known to feed on the primary resident of the nesting boxes tested (Gould’s Wattled Bat) (Kaiser and Hoogstraal, 1974), and this species of bat is known to travel great distances, therefore can potentially spreading this agent over great distances.

In addition, testing the blood of bats inhabiting the nesting boxes where the A. dewae ticks were found for evidence of SFG rickettsial exposure could also be undertaken and may provide data on whether the bats are being exposed to this agent.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge Lisa Evans, Natasha Schedvin, Robert Bender and Marissa Izzard for their assistance with this project. The sequencing on this project was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services under contract number HHSN272200900007C

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ, 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew R, Bonnin J, Williams S, 1946. Tick typhus in north Queensland. Med J Aust. II, 253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angiuoli SV, Salzberg SL, 2011. Mugsy: fast multiple alignment of closely related whole genomes. Bioinformatics. 27, 334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry C, Socolovschi C, Raoult D, Parola P, 2016. Bacterial agents in 248 ticks removed from people from 2002 to 2013. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 7, 475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aung AK, Spelman DW, Murray RJ, Graves S, 2014. Rickettsial infections in Southeast Asia: implications for local populace and febrile returned travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 91, 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird RW, Lloyd M, Stenos J, Ross BC, Stewart RS, Dwyer B, 1992. Characterization and comparison of Australian human spotted fever group rickettsiae. J Clin Microbiol. 30, 2896–2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J,Sayers EW, 2013. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brites-Neto J, Duarte KM,Martins TF, 2015. Tick-borne infections in human and animal population worldwide. Vet World. 8, 301–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calisher CH, Childs JE, Field HE, Holmes KV,Schountz T, 2006. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 19, 531–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SJ, Browning P,Scott JC, 2006. Ornithodoros moubata, a soft tick vector for Rickettsia in east Africa? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1078, 373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duh D, Punda-Polic V, Avsic-Zupanc T, Bouyer D, Walker DH, Popov VL, Jelovsek M, Gracner M, Trilar T, Bradaric N, Kurtti TJ,Strus J, 2010. Rickettsia hoogstraalii sp. nov., isolated from hard- and soft-bodied ticks. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 60, 977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Pena A,Jongejan F, 1999. Ticks feeding on humans: a review of records on human-biting Ixodoidea with special reference to pathogen transmission. Exp Appl Acarol. 23, 685–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier P, Dumler J, Greub G, Zhang J, Wu Y,Raoult D, 2003. Gene sequence-based criteria for identification of new Rickettsia isolates and description of Rickettsia heilonjiangensis sp. nov. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 41, 5456–5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier PE, Dumler JS, Greub G, Zhang J, Wu Y,Raoult D, 2003. Gene sequence-based criteria for identification of new rickettsia isolates and description of Rickettsia heilongjiangensis sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 41, 5456–5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH,Scornavacca C, 2012. Dendroscope 3: an interactive tool for rooted phylogenetic trees and networks. Syst Biol. 61, 1061–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzard L, Graves S, Cox E, Fenwick S, Unsworth N,Stenos J, 2009. Novel rickettsia in ticks, Tasmania, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 15, 1654–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser M,Hoogstraal H, 1974. Bat ticks of the genus Argas (Ixodoidea: Argasidae). 10. A. (Carios) dewae, new species, from southeastern Australia and Tasmania. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 67, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lafri I, Leulmi H, Baziz-Neffah F, Lalout R, Mohamed C, Mohamed K, Parola P,Bitam I, 2015. Detection of a novel Rickettsia sp. in soft ticks (Acari: Argasidae) in Algeria. Microbes Infect. 17, 859–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis AD, Gill JS, Schriefer ME, Levin ML, Eremeeva ME, Gilchrist MJ,Dasch GA, 2005. Detection of Rickettsia, Borrelia, and Bartonella in Carios kelleyi (Acari: Argasidae). J Med Entomol. 42, 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediannikov O, Makarova V, Tarasevich I, Sidelnikov Y,Raoult D, 2009. Isolation of Rickettsia heilongjiangensis strains from humans and ticks and its multispacer typing. Clin Microbiol Infect. 15 Suppl 2, 288–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhano N, Palma M, Marcili A, Nuncio MS, de Carvalho IL,de Sousa R, 2014. Rickettsia lusitaniae sp. nov. isolated from the soft tick Ornithodoros erraticus (Acarina: Argasidae). Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 37, 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühldorfer K, 2013. Bats and bacterial pathogens: a review. Zoonoses Public Health. 60, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Giannelli A, Latrofa MS, Cascio A, Cazzin S, Ravagnan S, Montarsi F, Zanzani SA, Manfredi MT,Capelli G, 2014. Ticks infesting humans in Italy and associated pathogens. Parasit Vectors. 7, 328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen H, Clark P, Stenos J, Robertson I,Fenwick S, 2006. Potentially pathogenic spotted fever group rickettsiae present in Western Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 14, 284–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen H, Unsworth N, Stenos J, Robertson I, Clark P,Fenwick S, 2006. Detection and identification of a novel spotted fever group rickettsia in Western Australia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1078, 197–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P, Paddock CD, Socolovschi C, Labruna MB, Mediannikov O, Kernif T, Abdad MY, Stenos J, Bitam I, Fournier PE,Raoult D, 2013. Update on tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: a geographic approach. Clin Microbiol Rev. 26, 657–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves WK, Loftis AD, Sanders F, Spinks MD, Wills W, Denison AM,Dasch GA, 2006. Borrelia, Coxiella, and Rickettsia in Carios capensis (Acari: Argasidae) from a brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) rookery in South Carolina, USA. Exp Appl Acarol. 39, 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts FHS (1970). Australian Ticks. Melbourne, CSIRO. [Google Scholar]

- Schloderer D, Owen H, Clark P, Stenos J,Fenwick SG, 2006. Rickettsia felis in fleas, Western Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 12, 841–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ,Weber CF, 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socolovschi C, Kernif T, Raoult D,Parola P, 2012. Borrelia, Rickettsia, and Ehrlichia species in bat ticks, France, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 18, 1966–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 30, 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenos J, Graves SR,Unsworth NB, 2005. A highly sensitive and specific real-time PCR assay for the detection of spotted fever and typhus group Rickettsiae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 73, 1083–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RS, 1991. Flinders Island spotted fever: a newly recognised endemic focus of tick typhus in Bass Strait. Part 1. Clinical and epidemiological features. Med J Aust. 154, 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir D, Socolovschi C, Marie JL, Ganay G, Berenger JM, Bompar JM, Blanchet D, Cheuret M, Mediannikov O, Raoult D, Davoust B,Parola P, 2016. New Rickettsia species in soft ticks Ornithodoros hasei collected from bats in French Guiana. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 7, 1089–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T, Uchiyama T, Kumano K,Walker DH, 1992. Rickettsia japonica sp. nov., the etiological agent of spotted fever group rickettsiosis in Japan. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 42, 303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]