Abstract

Background

Despite recent progress in survival times of xenografts in nonhuman primates, there are no reports of survival beyond 5 days of histologically well-aerated porcine lung grafts in baboons. Here we report our initial results of pig-to-baboon xeno lung transplantation (XLTx).

Methods

Eleven baboons received genetically modified porcine left lungs from either GalT-KO alone (n=3), GalT-KO/humanCD47(hCD47)/hCD55 (n=3), GalT-KO/hD47/hCD46 (n=4) or GalT-KO/hCD39/hCD46/hCD55/TBM/EPCR (n=1) swine. The first two XLTx procedures were performed under a non-survival protocol that allowed a 72-hour follow-up of the recipients with general anesthesia, while the remaining nine underwent a survival protocol with intention of weaning from ventilation.

Results

Lung graft survivals in the 2 non-survival animals were 48 and >72 hours, while survivals in the other nine were 25 and 28 hours, 5, 5, 6, 7, >7, 9 and 10 days. One baboon with graft survival >7 days, whose entire lung graft remained well-aerated, was euthanized on POD7 due to malfunction of femoral catheters. hCD47 expression of donor lungs was detected in both alveoli and vessels only in the three grafts surviving >7, 9 and 10 days. All other grafts lacked hCD47 expression in endothelial cells and were completely rejected with diffuse hemorrhagic changes and antibody/complement deposition detected in association with early graft loss.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is first evidence of histologically viable porcine lung grafts beyond 7 days in baboons. Our results indicate that GalT-KO pig lungs are highly susceptible to acute humoral rejection and that this may be mitigated by transgenic expression of hCD47.

Keywords: Xenotransplantation, hCD47, Lung transplantation, pig-to-baboon

INTRODUCTION

Organ shortage is a major obstacle in clinical transplantation1. Although lung transplantation is now widely accepted as the only successful treatment for end-stage lung disease2, there is a large and growing discordance between the number of patients on the waiting list and donor organ availability3. Recent progress in xenotransplantation (XTx) increases the likelihood that XTx may provide a practical means for overcoming this organ shortage.

Size and both physiologic and anatomic similarities between swine and humans, as well as the tractability of swine to genetic modification, have made this species the most attractive potential donor for clinical XTx4–6. Use of multi-transgenic (Tg) swine donors has allowed survival of heterotopic hearts in baboons for over 2 years7, and consistent survivals of life-supporting kidneys for greater than 6 months8, 9. However, the results for lung xenotransplantation (XLTx) in pig-to-baboon models remain limited10–12, with only rare and sporadic reports of survivals over 5 days13. Rejected lung grafts were hemorrhagic despite the use of multi-Tg donors14 and to our knowledge, there have been no published reports of histologically proven survivals over 7 days. These results suggest the presence of unique immunologic barriers in pig-to-primate XLTx.

In the present study, we have attempted to prolong survival of porcine XLTx in baboons by combined strategies, consisting of (i) utilizing four different genetically modified porcine lungs, especially focusing on the role of hCD47 expression in donor lung grafts, and (ii) utilizing an induction immunosuppressive regimen that is similar to that of the xeno kidney transplant model that has achieved an average of longer than 4 months survival of life-supporting GalT-KO alone kidney grafts in baboons15. In designing this strategy, we reasoned; i) that hCD47 expression might overcome problems caused by the known species incompatibility of porcine CD47 and the primate homlog of its ligand, signal-regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα)16,17,18,19; and ii) that hCD55 or hCD46 would mitigate the complement-mediated effects of natural anti-pig antibodies. We also tested whether vascularized thymic grafts from the same donors might facilitate prolonged xenograft lung survival by minimizing primate anti-pig T cell responses20–22. We have previously reported successful induction of tolerance by transplantation of allogeneic VTL23, 24 or thymokidneys (TK)21, 25 as well as markedly prolonged survival of life-supporting porcine TKs in baboons26. Most recently, we have achieved greater than 6-month survival of a life-supporting porcine TK with a modified immunosuppressive regimen15.

Using this strategy, we report here >7-day survival with histological evidence of viable lung xenografts. Immuno-histological analysis of donor lungs demonstrated hCD47 expression both on endothelium and alveolar epithelium only in lungs from donors that survived > 7 days. All other donors lacked hCD47 expression on pulmonary endothelial cells and were completely rejected early with diffuse hemorrhagic changes and antibody/complement deposition. Our data suggest that a unique immunological environment exists in lungs and that hCD47 expression in both alveoli and vessels may play an important role in reducing immunologic damages that cause the early loss of lung xenografts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Recipients

We used eleven baboons (Papio hamadryas) purchased from Mannheimer Foundation, Homestead, FL.

Donors

We used two different strains of GalT-KO pigs. One was the Sachs/Columbia GalT-KO, inbred miniature swine with or without genetic modification to carry hCD47 and hCD55 transgenes27,28 (Fig.1). Four F1 and F2 generation offspring of the founders of this line were used in this study. The other animals were outbred domestic swine provided by Revivicor Inc. (Blacksburg, VA) that carried either hCD46/hCD47 GalT-KO or GalT-KO/hCD39/hCD46/hCD55/hTBM/hEPCR genetic modifications. To confirm transgenic expression in donor lungs, contralateral right naïve lung tissues of donor pigs were collected and stained with anti-human CD39, hCD46, hCD47, hCD55, TBM and EPCR abs (Table 1).

Figure 1.

pDAF (CD55)-CD47 Expression Vector for Transgenic Pig Production. hCD47 and hCD55 expression cassettes are oriented in opposing directions. The hCD55 minigene is comprised of human genomic DNA including the native promoter/enhancer region, the 3′ UTR through the pA, exon 1 and intron 1. The cording sequence (CDS) sequence was substituted for genomic sequences covering the remaining exons. A small segment of plasmid backbone follows the CD55 minigene (not shown).

Table 1.

Donors’ background, hCD47/hCD55 expression in donor GalTKO lungs and graft survival

| Recipient baboon ID | Preformed anti-nonGal cytotoxicity (1:4 ratio) | Survival of donated left grafts | Donor pig ID (source) | Gene expression in lungs | VTL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hCD47 | hCD55 | hCD46 | hTBM | EPCR | hCD39 | |||||||||||

| Ves | Alv | Ves | Alv | Ves | Alv | Ves | Alv | Ves | Alv | Ves | Alv | |||||

| 13P44 | 14.9% |

10 days Well-aerated lung at POD 7. Partially rejection at POD 10 |

24051 (Sachs) | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13P17 | 19.9% |

9 days Partially aerated lung at POD 7. Rejected at POD 9 |

864-01 (Revivicor: Rev) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 14P4 | 24.1% | >7 days Well-aerated entire lung graft |

23697 (Sachs) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 12P79 | 14.3% | Complete rejection with hemorrhagic changes at POD 7 | 23945 (Sachs) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| 11P67 | 26.8% | Complete rejection with hemorrhagic changes at POD 6 | 23656 (Sachs) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 12P53 | 11.7% | Complete rejection with hemorrhagic changes at POD 5 | 884-01 (Rev) | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Technical failure |

| 12P78 | 14.7% | Complete rejection with hemorrhagic changes at POD 5 | 883-02 (Rev) | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Technical failure |

| 13P85 | 41.87% | Partially rejected at 72 hrs (non-survival procure to follow-up up to 72 hrs) | 23519 (Sachs) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13P64 | 46.8% | Rejected at 48 hrs (non-survival procure) | 23604 (Sachs) | No | Yes Low |

Yes Low |

Yes Low |

No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 14P50 | 14.0% | Rejected at 28 hrs | 940-2 (Rev) | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 14P27 | 40.9% | Rejected at 25 hrs | 864-03 (Rev) | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Alv: Alveolar epithelial cells

Ves: Vascular endothelium including alveolar capillary endothelium and pulmonary arterial endothelium

All procedures and animal care were performed in accordance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care formulated by The National Society for Medical Research and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC).

Experimental Groups

Non-survival procedure group

As the initial experiment, we performed 2 non-survival procedures to examine sequential changes of porcine lung grafts in baboons under general anesthesia for up to 72 hours (hrs) after reperfusion, with ventilation.

Survival procedure group

We next performed 9 survival procedures, in which recipients were sedated and maintained with ventilation support for 16hrs after reperfusion of lung xenografts and then weaned from ventilation.

In both non-survival and survival procedures, gross findings were noted, as well as graft PV gas analysis and tissue biopsy. If the graft could not be inflated and PF ratio (PaO2/FiO2: fractional inspired oxygen) of graft PV was <150 mmHg, then the animal was sacrificed. Details of monitoring are described in Supplemental Methods.

Details of donors, experimental groups, the immunosuppressive regimen, surgical procedures, histological examination, flow cytometric analyses, and total and cytotoxic antibody assays are provided as Supplementary Information (References29,30,31,32,33,34).

Results

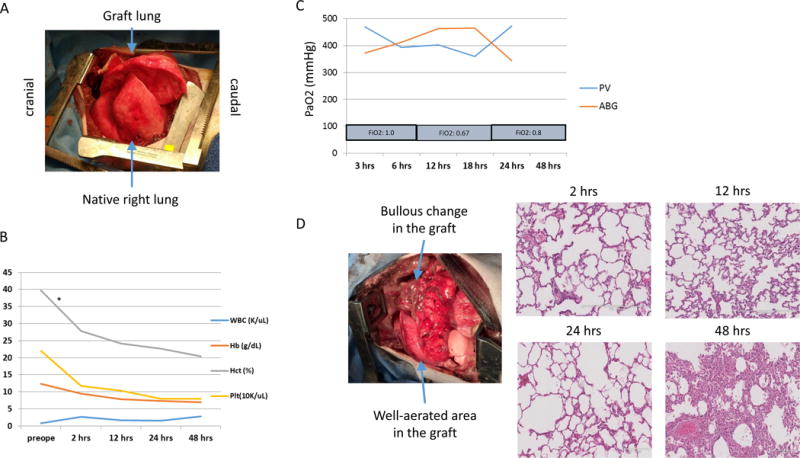

A. Two non-survival procedures performed successfully as a pilot study

In our initial study, we performed 2 non-survival transplant procedures. Both cases were successfully completed without technical or anesthetic complications. Graft survivals for these two cases were 48hrs (Baboon ID #13P64) and >72hrs (13P85), respectively (Table 1). In the first procedure (13P64), both the left lung graft and the right native lung appeared well-perfused and expanded (Fig.2A). The general status of the recipient, including oxygenation, was stable. One unit of packed red blood cells (pRBC) was transfused 2hrs after revascularization (Fig.2B). In addition, the PaO2 of the blood from the graft PV was stable, similar to systemic ABG (Fig.2C). However, at 48hrs post-reperfusion, the graft PA flow weakened and no blood could be taken from the graft PV, indicating graft rejection. Hemorrhagic changes and congestion were seen, both grossly and histologically (Fig.2D). For the 2nd case (13P85), due to the size of the donor, we used the left lower lobe for transplantation into a 7kg baboon. Bullae did not develop and the recipient maintained stable systolic blood pressure and SpO2 levels during the entire 72-hr follow-up period (Fig.3A). The platelet counts did not decrease below 50K after revascularization (Fig.3B). The graft was aerated and the PaO2 from the graft PV was continuously maintained >200mmHg throughout the transplant, until termination of the experiment at 72hrs post-reperfusion (Fig.3C). However, histologic findings showed that although there were still patent small vessels and preservation of alveolar structure, some areas showed hemorrhagic changes and congestion (Fig.3D). Based on these results, we proceeded to the survival study.

Figure 2.

(A) Gross findings of native right lung and graft left lung of #13P64 immediately after reperfusion. Both lungs are well expanded and perfused. (B) CBC data during the experiment. All data (WBC, Hb, Hct and Platelets count) were stable till the termination, although one unit of pRBC was given at 2 hrs post-reperfusion (*). (C) PaO2 of systemic arterial blood gas and graft PV blood gas analysis. The PaO2 of both showed similar good value during the experiment. (D) Gross finding of the graft at the time of the termination and H&E findings of lung graft o at 2hr, 12hr, 24hr and 48 hr. Bullous change increased grossly. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic change increased with time.

Figure 3.

(A) Systolic blood pressure and SpO2 of #13P85. Systolic blood pressure was > 90 mmHg and SpO2 was constantly > 95%. (B) CBC data during experiment. Although three pRBC transfusions (*) were required due to anemia, WBC and platelets were stable. (C) PaO2 of systemic arterial gas and graft PV gas. The PaO2 of both were of good value until the end of the experiment. (D) Gross finding of the graft lung at 72 hrs after and H&E findings of lung graft at 2, 24, 48 and 72 hrs after Tx. Although some superficial congestion due to atelectasis from compression by chest wall was found, the lung graft was well expanded and perfused grossly. Hemorrhagic change, congestion and microthrombi increased with time. However, there were still expanded alveoli and patent vessels 72 hrs after revascularization.

B. Nine survival procedures

Seven of the 9 survival recipients were successfully weaned from ventilation support and returned to their cages within 24hrs after revascularization of porcine lung grafts. In two cases (14P27 and 14P50) the recipients were euthanized at 25hrs and 28hrs, respectively, post-reperfusion, due to accelerated acute humoral rejection, which was confirmed by pathological examination (details in next section). Seven baboons were extubated and brought to their usual cages, without any special oxygen support. Although others have reported a high incidence of unsuccessful weaning from ventilators due to pulmonary or tracheal edema35, we did not experience this complication. Survival of these seven lung xenografts was 5 days (12P53), 5 days (12P78), 6 days (11P67), 7 days (12P79), >7 days (14P4), 9 days (13P17), and 10 days (13P44). #14P4 was euthanized on day 7 with a functioning entire lung graft due to progressive leg edema associated with malfunction of a femoral catheter. Recipients were euthanized at the time of porcine lung graft excision. No technical issues were apparent.

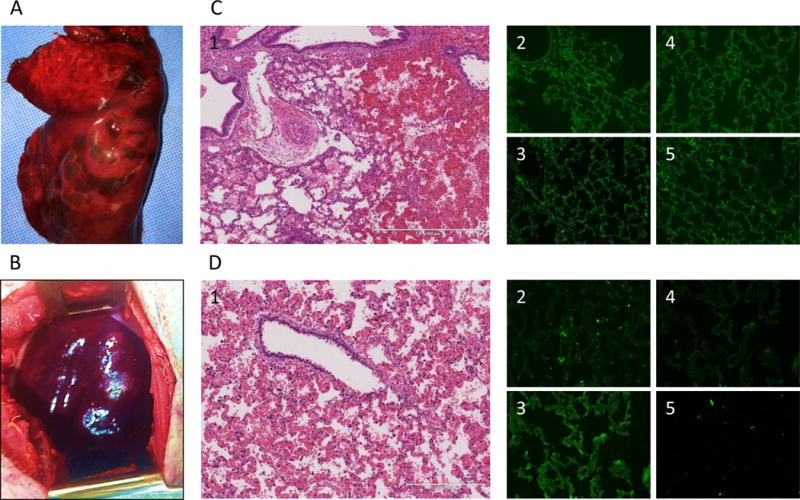

Clinical data and histology of excised lung grafts in the survival procedure

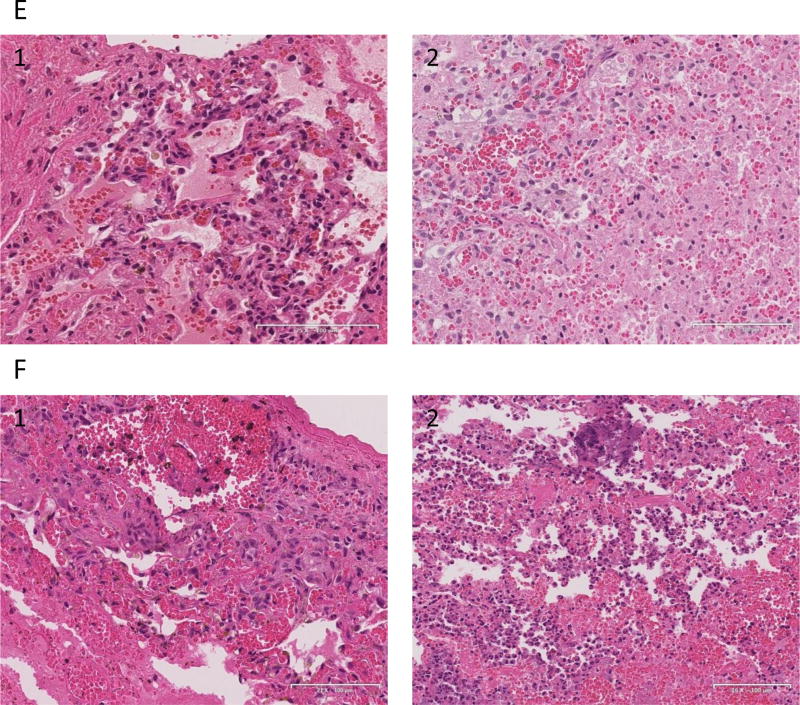

Two grafts (14P27 and 14P50) demonstrated accelerated rejection, with diffuse hemorrhagic changes at 25hrs and 28hrs, respectively, post-revascularization (Fig.4A, B). Histologically, both grafts had alveolar bleeding (Fig.4C-1 and D-1). Immunofluorescence staining of the #14P27 graft showed not only IgM and IgG deposits, but also C3 deposits, indicating severe humoral rejection (Fig.4C2–5) while the #14P50 graft showed IgM and IgG deposits but C3 was negative (Fig.4D2–5).

Figure 4.

(A) necropsy finding of the lung graft of #14P27 and (B) 14P50. Severe congestion and hemorrhagic change were found. (C-1) HE finding at 25 hrs after Tx of #14P27. Hemorrhagic change and congestion increased. (C2-5) Immunofluorescence staining of IgM (C-2), IgG (C-3), C3 (C-4) and C5b (C-5) of the lung graft at 25 hrs after Tx. The positive deposition of IgM, IgG, C3 and C5b were detected. (D-1) H&E finding at 28 hrs after Tx of #14P50. Hemorrhagic changes and congestion were observed (D2-5) Immunofluorescence staining of IgM (D-2), IgG (D-3), C3 (D-4) and C5b (D-5) of the lung graft at 28 hrs after Tx. The positive deposits of IgM and IgG were detected. (E) The H&E finding of the lung graft of #12P53 (E-1) and 12P78 (E-2) at POD 5. Severe diffuse hemorrhagic changes were observed. (F) The H&E finding of the lung graft of #11P67 (F-1, POD 6) and 12P79 (F-2, POD 7), showing severe hemorrhagic changes.

Four baboons (12P79, 11P67, 12P53, 12P78) rejected lung xenografts completely by POD 7. They remained clinically stable (alert, systolic BP >100 mmHg), for at least 4 days. However, two baboons, #12P53 and #12P78, developed increased WBC counts, from 21K and 15K to 26K and 17K, respectively, at POD 5 with frequent coughing during the night on POD 4. These baboons were treated with additional antibiotics, and underwent a left thoracotomy on POD 5, when they were found to have diffusely hemorrhagic lung grafts with a blood gas from the graft PV of <100 mmHg. Histology of the excised grafts showed diffuse hemorrhage (Fig.4E-1, 2). The remaining animals, #11P67 and #12P79, developed continuous coughing and hemosputum 1 day prior to euthanasia. In addition, the chest tube output increased to >100 ml/24hrs, and the effusion became dark, indicating that the graft was severely rejected. The lung graft in both cases showed severe hemorrhagic change (Fig.4F-1, 2). Because of severe hemorrhagic and necrotic changes, immunohistology assessment for antibody deposits was not reliable due to high background.

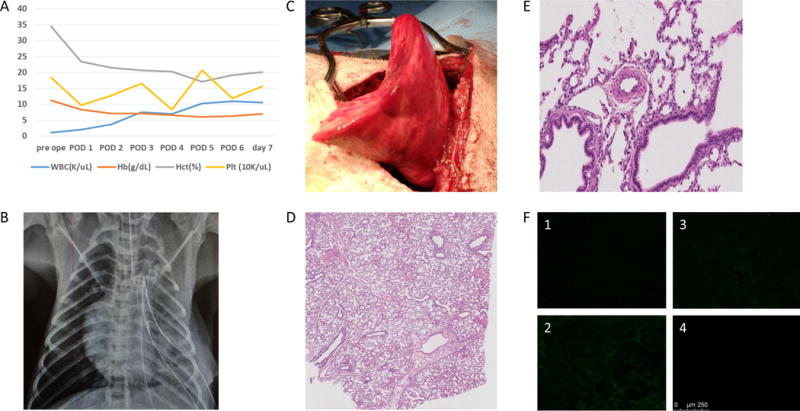

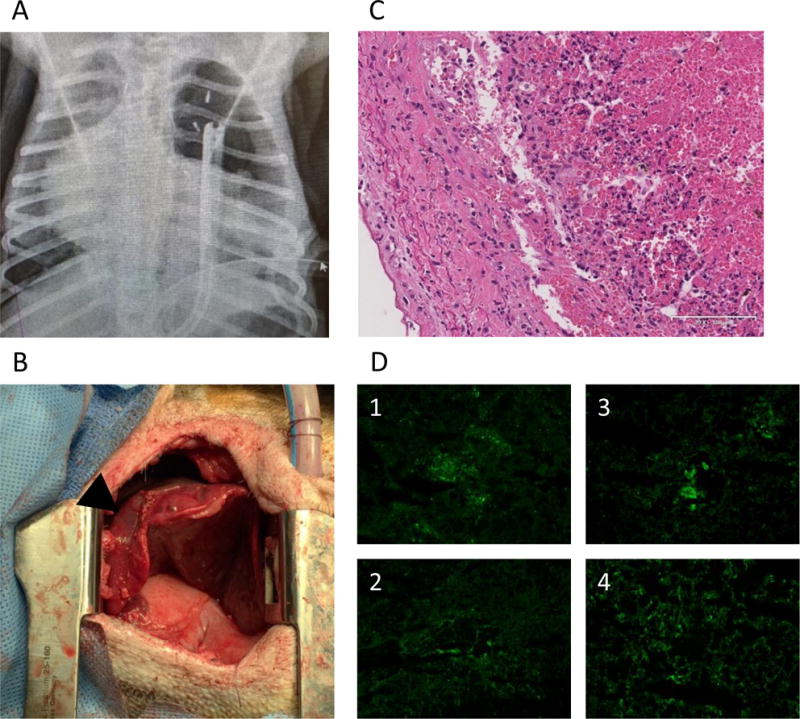

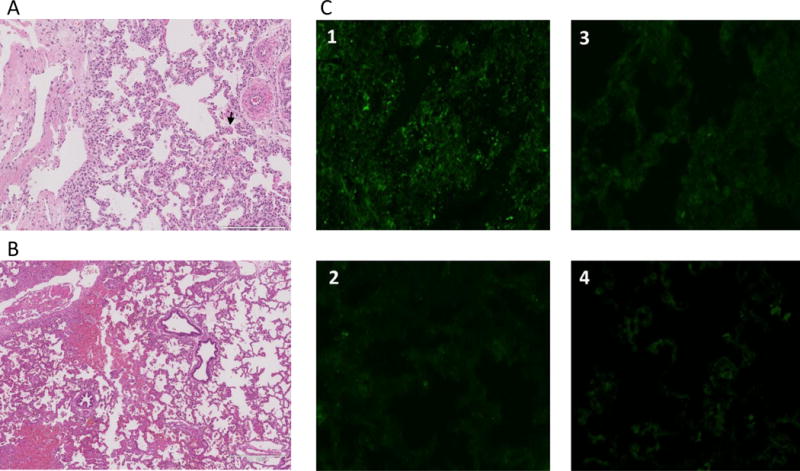

In contrast, the remaining three animals #14P4, #13P17 and #13P44, survived for >7 days; >7, 9 and 10 days. #14P4 showed no respiratory symptoms after XLTx. The animal developed lower extremity edema due to a femoral line occlusion (attributed to crystal formation associated with MMF infusion) on POD 6, necessitating euthanasia on POD 7. On POD 7, the chest X-ray showed that the entire lung was well aerated and gross examination through a left thoracotomy incision also demonstrated fully aerated upper and lower left lobes (Fig.5A–C). Biopsy specimens confirmed well-aerated alveolar spaces and no signs of rejection (Fig.5D, E). No deposition of IgM, IgG, C3, or C5b was detected on immunofluorescence staining (Fig.5F1–4), supporting the conclusion that this pig lung had remained rejection-free in the baboon recipient for 7 days, without elicited antibody, or complement activation. #13P17 had also a stable clinical course through POD 6. The chest X-ray on POD 7, when a cough developed, showed that the lower lobe was partially aerated and the upper lobe was completely collapsed (Fig.6A). Gross examination through a left thoracotomy also confirmed the partially-aerated lower lobe (Fig.6B). Blood gas from the graft PV was 400mmHg with a FiO2 of 100%. The small biopsy specimen from the edge of the lung graft was not viable. A second full examination was performed on POD 9, at which point the lung graft was severely congested and blood could not be obtained from the PV. Histology showed complete rejection of the lung on POD9 (Fig.6C) and a frozen section showed IgM, IgG, C3, and C5b deposits, indicating humoral rejection (Fig.6D). These data thus indicate that rejection likely started on POD 7, with complete rejection by POD 9.

Figure 5.

(A) CBC data during experiment of #14P4. (B) Chest X-ray finding and (C) gross finding of the graft through thoracotomy of #14P4 at POD 7. The lung graft was well expanded even with some inflammatory change. (D) H&E finding at POD 7 at low power and (E) at high power. The alveoli were well expanded and vessels were patent with minimal change. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of IgM (F-1), IgG (F-2), C3 (F-3) and C5b (F-4) of the lung graft. No deposition of these factors was seen.

Figure 6.

(A) the chest X-ray finding and (B) gross appearance through thoracotomy of #13P17 at POD 7. The lower lobe expanded (allow), although the upper lobe was collapsed (arrow head). (C) H&E finding of the lung graft at POD 9. Severe hemorrhagic change and congestion in the graft lung were shown. (D) Immunofluorescence staining (IgM, IgG, C3 and C5b) of the lung graft at POD 9. The positive deposition of IgM, IgG, C3 and C5b were detected.

The other animal, #13P44, had no respiratory symptoms after XLTx throughout the entire experimental period and did not reject the graft completely even by POD10. The chest X-ray on POD7 showed a well-aerated lower lobe but the upper lobe was collapsed, as subsequently confirmed by gross examination through a left thoracotomy. PV blood gas from the graft at that time showed a PaO2 of 400mmHg. Histology on POD7 showed well-aerated alveolar spaces although focal microthrombi (arrow in Fig.7A) were observed. The animal remained stable in the cage after the POD7 biopsy and the second full examination through left thoracotomy was performed on POD10. Despite only partial aeration of the lower lobe, blood gas from the graft PV was 92mmHg with a FiO2 of 100% during the time of this biopsy. Following biopsy, the recipient was euthanized in accordance with our protocol (graft PV gas <150mmHg). Histology at POD 10 confirmed viability of the aerated area of the lower lobe (approximately 50% of the lobe), along with hemorrhagic changes (Fig.7B). Frozen section showed focal IgM deposition but no IgG, C3 or C5b deposit was observed (Fig.7C1–4).

Figure 7.

(A) HE finding of the lung graft of #13P44 at POD7. Well-aerated alveolar spaces with focal mincrothrombi were observed. (B) HE finding of the lung graft of #13P44 at POD10 revealed that aerated area remained approximately 50% of lower lobe while hemorrhagic changes developed. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of IgM (C-1) IgG (C-2), C3 (C-3) and C5b (C-4) of the lung graft of 13P44 at POD 10. Deposition of anti-pig IgM was detected but not IgG, C3 or C5b. (D) Anti Non-Gal antibody levels of baboon recipients assessed by FCM from pre XLTx until the end of the experiment: (1) #14P4, (2)#13P17, (3) #13P44, (4)#12P79, (5)#11P67, (6)#12P53, (7)#12P78, (8)#13P85 (9)#13P64 (10)#14P50 and (11)#14P27 by FCM. All recipients had preformed anti-pig non-Gal NAb. However, no elicited anti-pig non-Gal Ab was observed in sera from any of recipients.

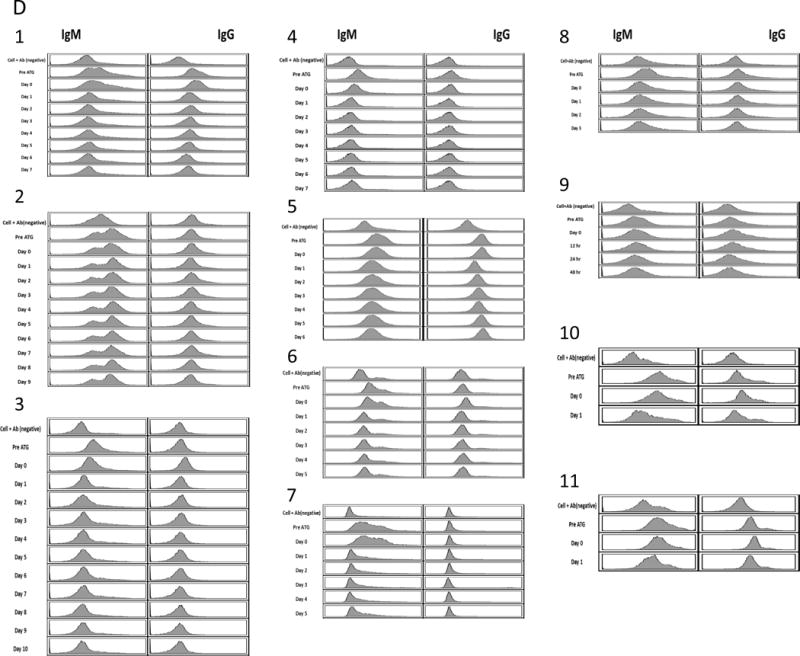

C. Baboon anti-pig antibodies (ab) following XLTx in all 11 recipients

All recipients had pre- formed anti-pig non-Gal NAb, predominantly IgM, assessed by FCM (Fig.7D1–11). The fluorescence intensity of anti-pig IgM decreased at POD 2, suggesting that anti-NAb were adsorbed by lung grafts (Fig.7D). However, we did not detect elicited anti-pig non-Gal Ab in the sera from any of the recipients, including those receiving lungs from GalT-KO alone and those receiving GalT-KO/hCD47/hCD55 XLTx. Elicited anti-pig ab may have accumulated in the rejected hemorrhagic grafts, and thus not have been detectable in sera.

D. Factors involved in avoiding the early loss of lung grafts

In order to examine factors that might play a role in avoiding the early loss of lung grafts, we constructed a table based on survival (Table 1). We divided animals into two sub-groups: (Sub-group A) survival >7 days with aerated lungs (n=3); (Sub-group B) complete rejection of lung grafts by POD7 (n=8). We also characterized transgene expression in donor lungs by examining the contralateral, right naïve lung tissues of donor pigs immuno-histologically.

(1) hCD47 expression in both alveoli and vessels in donor lungs may play an important role in prolonging xeno lung graft survival

To confirm transgenic expression in donor lungs, contralateral right naïve lung tissues of donor pigs were collected and stained with anti-human CD39, hCD46, hCD47, hCD55, TBM and EPCR (Table 1).

Sub-group A: Cases of lung graft survival >7 days (n=3)

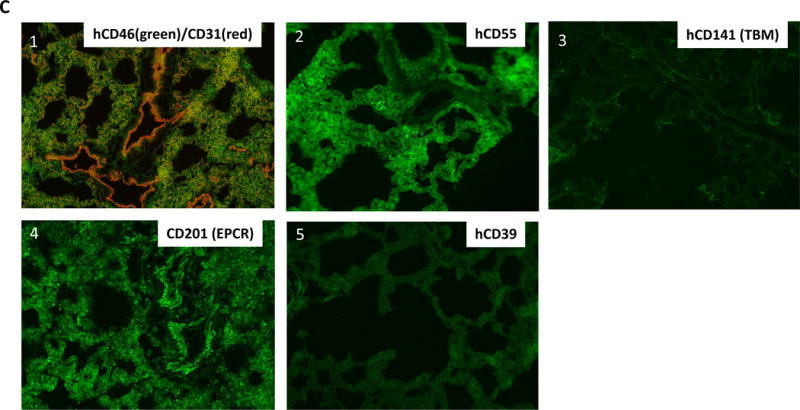

Two donors were Sachs/Columbia miniature swine (Pig-24051 and Pig-23697) and one was a hCD46/hCD47 Revivicor swine (864-01). Double staining with anti-human CD47 and anti-CD31 Ab of the donor’s contralateral lungs showed that all of those lungs expressed hCD47 on endothelial cells (orange in Fig. 8A 1, 2 and 3) and in the median layer (smooth muscle) of vessels (white arrows) as well as diffuse expression on alveolar epithelium (green in Fig. 8A1, 2 and 3). Assessment of hCD55 expression in two lungs of Sachs/Columbia miniature swine showed that the lung of #23697 had hCD55 expression in vessels and on alveoli (Fig.8B-1) while no hCD55 was detected in the lung of #24051 (Fig. 8B-2). hCD46 was expressed in vessels and on alveoli in the hCD46/hCD47 Revivicor swine (#864-01) (Fig. 8B-3).

Figure 8.

(A-1) Double-staining of hCD47 (green) and CD31 (red) of the lung graft of #14P4. hCD47 expression was positive both on alveolar epithelium (Alv) and vascular endothelium (EC) as well as median layers of vessels. Arrows indicate the vessels. (A-2) hCD47 expression of the lung graft of #13P44. Double staining of hCD47 and CD31 showed hCD47 expression was positive both on Alv and EC. (A-3) Double staining of hCD47/CD31 of the lung graft of 13P17. hCD47 expression was positive both on Alv and in vessels. (A-4) hCD47 expression of the lung graft of #12P53. Double staining of hCD47 and CD31 showed hCD47 expression was positive on Alv, but not on EC. Arrows indicate the lack of expression of hCD47 on EC. (B-1) Double staining of hCD55 (green) and CD31 (red) of the lung graft of #14P4. The expression was positive both on Alv and in vessels. Arrow indicates the vessel. (B-2) Double staining of hCD55 (green) and CD31 (red) of the lung graft of 13P44. hCD55 expression was undetectable. (B-3) Double-staining of hCD46 and CD31 of the lung graft of #13P17. hCD46 expression was positive both on Alv and in vessels. (B-4) Double staining of hCD46 and CD31 of the lung graft of #12P53. hCD46 expression was positive on both Alv and EC. (C): Immunofluorescence staining of the lung graft of #14P50. (C-1) Double staining of hCD46 and CD31 of the lung graft of #14P50. hCD46 expression was both positive on Alv and in vessels. (C-2) hCD55 was positive only on Alv, but not in vessels. (C-3) hCD141(TBM) expression of the lung graft of #14P50 showing no expression in the lung. (C-4) CD201 (EPCR) was positive both on Alv and EC. (C-5) hCD39 expression of the lung graft of #14P50 was undetectable.

Sub-group B: Cases of complete rejection of the lung grafts by POD 7 (n=8)

In contrast to Group 1, none of contralateral naïve lungs in Group 2 had hCD47 expression in vessels (Table 1). Four were Sachs/Columbia miniature swine and the remaining four were Revivicor swine. Lungs from three of four Sachs/Columbia miniature swine (Pig-23656, 23519 and 23945) had no expression of hCD47 or hCD55. Three of four Revivicor lungs expressed hCD46 and hCD47. Although hCD47 was expressed on alveolar epithelium, no hCD47 expression was observed in vessels (Fig.8A-4) despite hCD46 expression on alveolar epithelium and in vessels (Fig.8B-4). A remaining Revivicor pig was GalT-KO/hCD39/hCD46/hCD55/TBM/EPCR Tg (Fig.8C 1–5). Notably, this multi-transgenic GalT-KO animal lacked hCD47 and the baboon recipient rejected the lung at 28hrs after revascularization.

(2) Cytotoxicity levels of preformed anti-non-Gal natural antibody (NAb)

All recipients were screened for levels of cytotoxic preformed NAb (Table 1). Three of four animals in Subgroup B that lost grafts within 3 days had relatively high cytotocity (>40%). However, the remaining 5 animals in this subgroup had similar cytotoxicity levels to, or even slightly lower (26.8%, 14.7%, 14.3%, 14.0%, 11.7%) than those in Subgroup A (24.1%, 19.9%, 14.9%). Therefore, although high cytotoxic levels of anti-non-Gal pig NAb may promote early loss of lung grafts, low cytotoxicity of preformed anti-non-Gal NAb did not appear to be sufficient to assure prolongation of lung grafts.

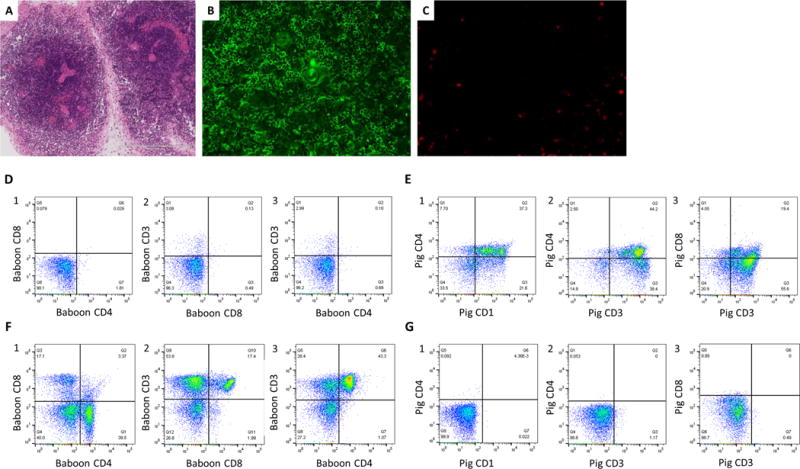

(3) Co-transplantation of pig VTLs

Five of 9 baboons under the survival protocol received VTL grafts simultaneously with the lung Tx, as part of a tolerance-inducing strategy that we have previously studied extensively in our kidney xenograft models15,26. Unfortunately, two cases were not well-vascularized soon after revascularization (i.e. technical failures). The other three VTL grafts turned pink immediately after revascularization (Table 1). We did not observe prolongation of survival of lung grafts by VTL grafts simultaneously transplanted. However, although excised lung grafts were rejected at 28hrs (14P50), POD7 (12P79) and POD9 (13P17), all three VTL grafts were found to be viable at necropsy, suggesting that a unique immunologic barrier, not present for thymus, led the early graft loss of lungs. H&E findings of these VTL grafts showed well-maintained thymic structure of the medulla and cortex (Fig. 9A). Cell populations of VTLs excised at POD 7 or 9 were examined by both histologic and FCM analysis, and showed consistent findings. Immunofluorescence staining showed that pig CD4-positive cells remained in the medulla (Fig.9B) and that baboon CD3-weak positive cells were present in the cortex (Fig.9C). FCM analysis of VTLs further confirmed the presence of these pig and baboon T cell populations. Using anti-human mAbs, baboon cells were detected with low intensity staining for CD3+ that lacked both CD4 and CD8 (Fig. 9-C and D), suggesting that thymopoiesis36 of baboon T cells might have been initated in the pig VTL. FCM analysis of the VTL using anti-pig Abs showed that the CD4+ pig cells seen in the medullary area (Fig.9B), were porcine CD3-high, indicating mature thymocytes (Fig.9E). These FCM profiles were clearly different from those of peripheral lymph nodes of the recipient baboons (Fig.9F and 9G), indicating persistence of viable pig VTL grafts in baboons that had lost pig lungs.

Figure 9.

H&E findings of the VTL graft (A) and IF staining finding of the VTL graft; (B): anti pig Ab and (C): anti human Ab. (A) Cellularity was rich in medulla while poor in cortex. (B) Pig CD4 positive cells (green color) were present in the medulla. (C) Baboon CD3 weak positive cells (red color) were observed in the cortex. FCM analysis of the VTL (D and E) and peripheral LN of the #12P79 (F and G). (D1-3) FCM analysis of the VTL graft by using anti-human Abs showed CD3 low positive CD4CD8 double negative cells derived from baboon were present in the VTL. (E1-2) FCM analysis of the VTL by using anti-pig Abs showed CD1 positive/CD3 high positive CD4 positive cells were present in the VTL, indicating mature pig thymocytes existed in the VTL and the VTL was viable. (F and G) FCM analysis of the peripheral LN of #12P79. Cells in baboon LN were CD4 single positive or CD8 single positive baboon cells, different from the finding of the VTL (F). A small percent (<0.5%) of pig chimerisn was observed in the baboon LN. (G)

Discussion

We report here >7-day survival with histological evidence of viable lung xenografts. Immunohistological analysis of donor lungs demonstrated hCD47 expression both on endothelium and alveolar epithelium only in lungs from donors that survived > 7 days. All other donor lungs lacked endothelial hCD47 expression and were completely rejected by POD 6. In addition, we observed acceptance of a vascularized thymic graft without hCD47 expression in a baboon that lost its lung xenograft. Our data suggest that a unique immunological environment exists in lungs and that hCD47 expression in both alveoli and vessels may play an important role in prolonging lung xenograft survival. To our knowledge, this is first evidence of histologically viable porcine lung grafts beyond 7 days in baboons and the first demonstration that GalT-KO pig lungs undergo acute humoral rejection, to which they may be uniquely susceptible. Our data suggest that this early humoral rejection may be mitigated by transgenic expression of hCD47.

Although the number of animals studied in this report is relatively small, it is noteworthy that among the 9 survival procedures, all three lung xenotransplants utilizing donors expressing hCD47 in their lung vessels survived greater than seven days with aerated lungs. In contrast, other donors, not expressing hCD47 in pulmonary vessels (Table), underwent severe rejection, associated with diffuse hemorrhage. Although additional animals are required to draw firm conclusions, the presented data suggest that expression of hCD47 in pig donor lung vessels may be important for protection of the lung grafts during the early post-transplant period.

Another potentially important finding was split acceptance of a VTL graft in the baboon that lost its xenograft lung at POD7 or 9, suggesting a unique immunological environment in lungs, since previous studies of kidney plus VTL grafts showed comparable survivals of both organs30,37. Indeed, we have previously demonstrated that co-transplantation of a pig vascularized thymus, either as TK or VTLs, markedly prolonged survival of pig kidneys in baboon recipients, compared with transplantation of kidneys alone26. In contrast, the porcine lung in baboon #12P79 was clearly rejected, despite the fact that the VTL graft from the same GalT-KO donor (Pig-23945) was viable and functioning, with evidence of well-preserved thymic structure with early recipient baboon thymopoiesis. A possible explanation for this dichotomy of organ survival relates to the fact that the mammalian pulmonary cappilaries are extremely thin38. Additionally, an inherently more robust innate immune response may exist within the lung due to its barrier function39–41. The alveolar capillary network may thus be particularly susceptible to endothelial activation or destruction associated with innate responses, including the effects of preformed NAb.

Our data, along with previous data in vitro and in vivo42,43, are consistent with the hypothesis that species incompatibility of CD47 and its ligand, signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα), may play an important role in the early destruction of endothelium in the alveolar network, resulting in hemorrhagic changes in lung grafts. In the present study, the lung grafts of both recipients surviving >7 days expressed hCD47 not only on alveolar epithelium but also on the endothelium, while all other lungs lacked hCD47 expression on the endothelium, despite the expression of hCD47 in alveoli. These results are also consistent with findings from this laboratory on the role of limited cross-species reactivity of CD47-SIRPα interactions44 and on the ability of transgenic hCD47 to prevent xenograft rejection by suppressing phagocytosis of donor cells17–19.

Based on our results along with other reports described above, preformed anti-non-Gal cytotoxicity is likely a synergistic factor, but not the sole mechanism of the early destruction of the alveolar network. Thus, human macrophages can phagocytose porcine cells even in the absence of Ab or complement activation45. In addition, low cytotoxic levels of preformed anti-pig Ab do not induce accelerated rejection of heart or kidney xenotransplants in GalT-KO pig-to-NHP models9, 46, 47. Taken together, these studies suggest a mechanism in which destruction of the fragile structure of alveolar capillary endothelium by preformed NAb, even at low level, combined with macrophage activation and/or phagocytosis of endothelial cells caused by CD47-SIRPα incompatibility, leads to diffuse hemorrhage in the grafts. Therefore, expression of hCD47 on vascular endothelium in lungs may be essential to the prevention of early destruction of the alveolar network across this xenogeneic barrier.

One of four Revivicor hCD46/hCD47 GalT-KO swine showed hCD47 expression in pulmonary vessels but the others did not. Although all Revivicor pigs were produced by cloning, and using an identical GalT-KO/CD46 background, two different founder animals with different CD47 integration events were used. While all demonstrated hCD47 expression in the lung, the line that expressed hCD47 specifically in pulmonary vessels was not an identical clone to the other three. The Sachs/Columbia hCD47/hCD55 Tg GalT-KO miniature swine were naturally produced from source pigs (Supplemental Document Table 1). Although F1 and F2 donors were descendants of two clonal generation founders, both of which were produced by nuclear transfer from the same cloned fetal cell line, transgenic donors in this study showed different expression patterns of hCD47 and hCD55 in the lungs (Table 1). This differs from the consistently low expression of hCD47 and consistently moderate expression of hCD55 observed in PBMC of this Tg line (not shown). Aside from global differences in gene expression between cloned and naturally produced animals48, transgenes introduced by other methods have been shown to exhibit epigenetic variability of expression. Epigenetic differences in expression can be dependent on genetic background and require multiple passages of the transgene through the germ line for stabilization49. The results presented here further emphasize the need for transgene expression monitoring, even in early generations of naturally produced source pigs.

In summary, the key new finding reported here is the high sensitivity of lung xenografts to antibody mediated rejection. All three lung xenografts that expressed hCD47 in the lungs at both alveolar and vascular levels (on both endothelial cells and median layers) survived ≥7, 9 and 10 days, with no histologic evidence of rejection for over 7 days. In contrast, all lung grafts not expressing hCD47 at these levels in this study were rejected by POD7 with hemorrhagic changes. Collectively, our results suggest that GalT-KO pig lungs are highly susceptible to acute vascular rejection that can be mitigated, but not totally avoided, by transgenic expression of hCD47 in donor lungs. It is therefore clear that further strategies will be required to prolong lung graft survival from days to months. In order to protect the alveolar capillary network, in addition to adding hCD47 and other vascular protective genes as well as genes to reduce antigens against non-Gal Abs50, strategies to minimize inflammatory responses caused by preformed Nab, macrophages, NK cells, T cells and B cells must be considered prior to XLTx. We are currently exploring delayed lung transplantation in recipients that have received tolerance inducing preconditioning with lung-specific strategies. We have previously reported that intra-bone bone marrow (IBBM) Tx in a GalTKO pig-to-baboon model allowed pig BM cells to engraft for over 28 days in a baboon, resulting in the induction of donor-specific unresponsiveness in vitro and prolonged survival of a xenokidney33. We have also previously reported that fully allogeneic porcine VTL grafts in recipients treated with 28 days of tacrolimus facilitated induction of tolerance of VTL-matched kidneys that were transplanted 3 months after VTL grafts without immunosuppression in a swine model23. We will now determine whether combining these delayed XLTx strategies a tolerance-inducing preconditioning regimen, with lung-specific treatment29 as well as with new Tgs donors50 will overcome the unique immunologic barriers in XLTx.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Masayuki Tasaki for his helpful advice and review of this manuscript. We thank Genzyme for rabbit ATG and Genentech for Rituximab. This research was supported by NIH grant P01AI45897, and sponsored research funding from Lung Biotechnology PBC. FCM analysis reported in this publication was performed in the CCTI Flow Cytometry Core, supported in part by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health under awards S10RR027050.

Abbreviations

- ABG

arterial blood gas

- Abs

antibodies

- Alv

alveolar epithelium

- BMT

bone marrow transplantation

- Br

bronchus

- CBC

complete blood count

- CO

carbon monoxide

- CUMC

Columbia University Medical Center

- DAF

decay accelerating factor

- EC

endothelium

- EPCR

endothelial protein C receptor

- FCM

flow cytometry

- FiO2

fractional inspired oxygen

- GalT-KO

alpha-13 galactocyl transferase knock out

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- IBBM

intra bone bone marrow

- IF

immunofluorescence

- IS

immunosuppression

- MMF

Mycophenolate Mofetil

- NAb

natural antibody

- NHP

nonhuman primate

- PA

pulmonary artery

- PaO2

partial pressure of oxygen

- PF ratio

PaO2/FiO2

- POD

postoperative days

- pRBC

packed red blood cell

- PV

pulmonary vein

- TBM

thrombomodulin

- TFPI

tissue factor pathway inhibitor

- Tx

transplantation

- SpO2

saturation of peripheral oxygen

- Tg

transgenic

- TK

thymokidney

- VTL

vascularized thymic lobe

- XLTx

xeno lung transplantation

- XTx

xeno transplantation

Footnotes

PROF. KAZUHIKO YAMADA (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-0510-5843)

References

- 1.Klassen DK, Edwards LB, Stewart DE, Glazier AK, Orlowski JP, Berg CL. The OPTN Deceased Donor Potential Study: Implications for Policy and Practice. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2016;16(6):1707–1714. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Benden C, Dipchand AI, Goldfarb SB, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-second Official Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplantation Report–2015; Focus Theme: Early Graft Failure. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2015;34(10):1264–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeshan BC, Rossano JW, Beck N, Hammond R, Kreindler J, Spray TL, et al. Lung transplant waitlist mortality: height as a predictor of poor outcomes. Pediatr Transplant. 2015;19(3):294–300. doi: 10.1111/petr.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sachs DH. The pig as a potential xenograft donor. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. 1994;43(1–3):185–191. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato M, Kagoshima A, Saitoh I, Inada E, Miyoshi K, Ohtsuka M, et al. Generation of alpha-1,3-Galactosyltransferase-Deficient Porcine Embryonic Fibroblasts by CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Knock-in of a Small Mutated Sequence and a Targeted Toxin-Based Selection System. Reprod Domest Anim. 2015;50(5):872–880. doi: 10.1111/rda.12565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hai T, Teng F, Guo R, Li W, Zhou Q. One-step generation of knockout pigs by zygote injection of CRISPR/Cas system. Cell research. 2014;24(3):372–375. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, Thomas ML, III, Clark T, Lewis BG, et al. Chimeric 2C10R4 anti-CD40 antibody therapy is critical for long-term survival of GTKO.hCD46.hTBM pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft. Nature communications. 2016;7:11138. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwase H, Hara H, Ezzelarab M, Li T, Zhang Z, Gao B, et al. Immunological and physiological observations in baboons with life-supporting genetically engineered pig kidney grafts. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24(2) doi: 10.1111/xen.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higginbotham L, Mathews D, Breeden CA, Song M, Farris AB, 3rd, Larsen CP, et al. Pre-transplant antibody screening and anti-CD154 costimulation blockade promote long-term xenograft survival in a pig-to-primate kidney transplant model. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22(3):221–230. doi: 10.1111/xen.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubicki N, Laird C, Burdorf L, Pierson RN, 3rd, Azimzadeh AM. Current status of pig lung xenotransplantation. Int J Surg. 2015;23(Pt B):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantu E, Gaca JG, Palestrant D, Baig K, Lukes DJ, Gibson SE, et al. Depletion of pulmonary intravascular macrophages prevents hyperacute pulmonary xenograft dysfunction. Transplantation. 2006;81(8):1157–1164. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000169758.57679.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper DK, Satyananda V, Ekser B, van der Windt DJ, Hara H, Ezzelarab MB, et al. Progress in pig-to-non-human primate transplantation models (1998–2013): a comprehensive review of the literature. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21(5):397–419. doi: 10.1111/xen.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantu E, Balsara KR, Li B, Lau C, Gibson S, Wyse A, et al. Prolonged function of macrophage, von Willebrand factor-deficient porcine pulmonary xenografts. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2007;7(1):66–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burdorf L, Laird C, O’Neill N, Dahi SS, Kubicki N, Zhang T, et al. Xenogeneic Lung Transplantation: Extending Life-Supporting Organ Function Using Multi-Transgenic Donor Pigs and Targeted Drug Treatments. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2016;35(4):S188. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.01.525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanabe T, Watanabe H, Shah JA, Sahara H, Shimizu A, Nomura S, et al. Role of Intrinsic (Graft) Versus Extrinsic (Host) Factors in the Growth of Transplanted Organs Following Allogeneic and Xenogeneic Transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2017 doi: 10.1111/ajt.14210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oldenborg PA, Zheleznyak A, Fang YF, Lagenaur CF, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science. 2000;288(5473):2051–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ide K, Wang H, Tahara H, Liu J, Wang X, Asahara T, et al. Role for CD47-SIRPalpha signaling in xenograft rejection by macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(12):5062–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609661104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navarro-Alvarez N, Yang YG. CD47: a new player in phagocytosis and xenograft rejection. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2011;8(4):285–288. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Yang YG. Innate cellular immunity and xenotransplantation. Current opinion in organ transplantation. 2012;17(2):162–167. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328350910c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Swenson K, Sergio JJ, Arn JS, Sachs DH, Sykes M. Skin graft tolerance across a discordant xenogeneic barrier. Nat Med. 1996;2(11):1211–1216. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada K, Shimizu A, Utsugi R, Ierino FL, Gargollo P, Haller GW, et al. Thymic transplantation in miniature swine. II. Induction of tolerance by transplantation of composite thymokidneys to thymectomized recipients. Journal of immunology. 2000;164(6):3079–3086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee LA, Gritsch HA, Arn JS, Emery DW, Glaser RM, Sablinski T, et al. Induction of tolerance to pig antigens in mice grafted with fetal pig thymus/liver grafts. Transplantation proceedings. 1994;26(3):1300–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamano C, Vagefi PA, Kumagai N, Yamamoto S, Barth RN, LaMattina JC, et al. Vascularized thymic lobe transplantation in miniature swine: thymopoiesis and tolerance induction across fully MHC-mismatched barriers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(11):3827–3832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306666101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nobori S, Samelson-Jones E, Shimizu A, Hisashi Y, Yamamoto S, Kamano C, et al. Long-term acceptance of fully allogeneic cardiac grafts by cotransplantation of vascularized thymus in miniature swine. Transplantation. 2006;81(1):26–35. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000200368.03991.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada K, Vagefi PA, Utsugi R, Kitamura H, Barth RN, LaMattina JC, et al. Thymic transplantation in miniature swine: III. Induction of tolerance by transplantation of composite thymokidneys across fully major histocompatibility complex-mismatched barriers. Transplantation. 2003;76(3):530–536. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000080608.42480.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada K, Yazawa K, Shimizu A, Iwanaga T, Hisashi Y, Nuhn M, et al. Marked prolongation of porcine renal xenograft survival in baboons through the use of alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout donors and the cotransplantation of vascularized thymic tissue. Nat Med. 2005;11(1):32–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolber-Simonds D, Lai L, Watt SR, Denaro M, Arn S, Augenstein ML, et al. Production of alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase null pigs by means of nuclear transfer with fibroblasts bearing loss of heterozygosity mutations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(19):7335–7340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307819101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tena AA, Sachs DH, Mallard C, Yang YG, Tasaki M, Farkash E, et al. Prolonged Survival of Pig Skin on Baboons After Administration of Pig Cells Expressing Human CD47. Transplantation. 2017;101(2):316–321. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahara H, Shimizu A, Setoyama K, Oku M, Okumi M, Nishimura H, et al. Beneficial effects of perioperative low-dose inhaled carbon monoxide on pulmonary allograft survival in MHC-inbred CLAWN miniature swine. Transplantation. 2010;90(12):1336–1343. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ff8730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto S, Lavelle JM, Vagefi PA, Arakawa H, Samelson-Jones E, Moran S, et al. Vascularized thymic lobe transplantation in a pig-to-baboon model: a novel strategy for xenogeneic tolerance induction and T-cell reconstitution. Transplantation. 2005;80(12):1783–1790. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000184445.70285.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu A, Yamada K, Robson SC, Sachs DH, Colvin RB. Pathologic characteristics of transplanted kidney xenografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(2):225–235. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaMattina JC, Kumagai N, Barth RN, Yamamoto S, Kitamura H, Moran SG, et al. Vascularized thymic lobe transplantation in miniature swine: I. Vascularized thymic lobe allografts support thymopoiesis. Transplantation. 2002;73(5):826–831. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200203150-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tasaki M, Wamala I, Tena A, Villani V, Sekijima M, Pathiraja V, et al. High incidence of xenogenic bone marrow engraftment in pig-to-baboon intra-bone bone marrow transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2015;15(4):974–983. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griesemer A, Liang F, Hirakata A, Hirsh E, Lo D, Okumi M, et al. Occurrence of specific humoral non-responsiveness to swine antigens following administration of GalT-KO bone marrow to baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2010;17(4):300–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2010.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burdorf L, Laird C, O’Neill N, et al. New multi-transgenic donor pigs and targeted drug treatments extended lifesupporting xenogeneic lung function. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22(s193) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ceredig R, Rolink T. A positive look at double-negative thymocytes. Nature reviews Immunology. 2002;2(11):888–897. doi: 10.1038/nri937. e-pub ahead of print 2002/11/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buhler L, Yamada K, Alwayn I, Kitamura H, Basker M, Barth RN, et al. Miniature swine and hDAF pig kidney transplantation in baboons treated with a nonmyeloablative regimen and CD154 blockade. Transplantation proceedings. 2001;33(1–2):716. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)02220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller DL. Mechanisms for Induction of Pulmonary Capillary Hemorrhage by Diagnostic Ultrasound: Review and Consideration of Acoustical Radiation Surface Pressure. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42(12):2743–2757. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreisel D, Goldstein DR. Innate immunity and organ transplantation: focus on lung transplantation. Transplant international : official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. 2013;26(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engelmann B, Massberg S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13(1):34–45. doi: 10.1038/nri3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantu E, Lederer DJ, Meyer K, Milewski K, Suzuki Y, Shah RJ, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis identifies key innate immune pathways in primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2013;13(7):1898–1904. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao M, Roberts DD, Isenberg JS. Thrombospondin-1 inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell responses occurs via modulation of both cAMP and cGMP. Pharmacological research. 2011;63(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slee JB, Alferiev IS, Nagaswami C, Weisel JW, Levy RJ, Fishbein I, et al. Enhanced biocompatibility of CD47-functionalized vascular stents. Biomaterials. 2016;87:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Subramanian S, Parthasarathy R, Sen S, Boder ET, Discher DE. Species- and cell type-specific interactions between CD47 and human SIRPalpha. Blood. 2006;107(6):2548–2556. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1463. e-pub ahead of print 2005/11/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ide K, Ohdan H, Kobayashi T, Hara H, Ishiyama K, Asahara T. Antibody- and complement-independent phagocytotic and cytolytic activities of human macrophages toward porcine cells. Xenotransplantation. 2005;12(3):181–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2005.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Azimzadeh AM, Kelishadi SS, Ezzelarab MB, Singh AK, Stoddard T, Iwase H, et al. Early graft failure of GalTKO pig organs in baboons is reduced by expression of a human complement pathway-regulatory protein. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22(4):310–316. doi: 10.1111/xen.12176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griesemer AD, Hirakata A, Shimizu A, Moran S, Tena A, Iwaki H, et al. Results of gal-knockout porcine thymokidney xenografts. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9(12):2669–2678. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koike T, Wakai T, Jincho Y, Sakashita A, Kobayashi H, Mizutani E, et al. DNA Methylation Errors in Cloned Mouse Sperm by Germ Line Barrier Evasion. Biology of reproduction. 2016;94(6):128. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.116.138677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki S, Iwamoto M, Saito Y, Fuchimoto D, Sembon S, Suzuki M, et al. Il2rg gene-targeted severe combined immunodeficiency pigs. Cell stem cell. 2012;10(6):753–758. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butler JR, Martens GR, Estrada JL, Reyes LM, Ladowski JM, Galli C, et al. Silencing porcine genes significantly reduces human-anti-pig cytotoxicity profiles: an alternative to direct complement regulation. Transgenic research. 2016;25(5):751–759. doi: 10.1007/s11248-016-9958-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.