Abstract

This is a retrospective study aimed to investigate the patterns of myopic fundus complications in Indian children and young adults. Electronic medical records of 29,592 patients, aged 10–40 years, who visited L V Prasad Eye Institute between 1st January to 31st December 2016 were analysed in the study. Data such as age, gender, refractive error and various pathologic lesions of posterior globe were considered for analysis. Among all the patients with different types of refractive errors, myopia was found in 47.4%, high myopia in 6.8% and pathologic myopia in 2.2%. There was no trend of the increased prevalence of pathologic myopia with increasing age, except for a significant difference between the children aged 10–15 years (2.7%) and those aged more than 15 years (>4%). . Although, the overall pattern of pathologic lesions was similar across different grades of myopia (2.5% in low myopes vs. 2.2% in severe myopes), lesions like staphyloma and retinal detachment increased with increasing degree of myopia. The proportion of pathologic lesions across different grades of myopia suggests the necessity for careful peripheral fundus examinations irrespective of the degree of myopia for better management and prognostic purposes.

Introduction

Myopia has become an epidemic worldwide with steep increase in incidence of myopia in last few decades1–4. A meta-analysis published in 2017 shows the estimated pool prevalence of myopia to be 24.2% (95% CI, 3.3% to 44.8%) in children younger than 20 years and about 30% in adults older than 40 years in Asian population1. Globally, the prevalence of myopia has increased from 22.9% (uncertainty interval, 15.2–31.5%) in 2000 to 28.3% in 2010 (20.6–36.9%) and it is estimated to reach 49.8% by 20505.

Continuous axial elongation of the eye leads to the over stretching of outer coats causing various pathologic changes such as tessellation of fundus, posterior staphyloma, optic disc changes, chorioretinal atrophy, lacquer cracks and choroidal neovascularisation6. Prevalence of pathologic myopia varies from 0.9% to 3.1% in Asians7–10 and 1.2% in Caucasians11. Vision impairment due to pathologic myopia is mostly irreversible12. The pathologic changes progress as the age increases and the associated vision threatening complications possibly increase the economic burden to the individual, family and country13,14. Around 5.8–7.8% of Europeans15–18, 4.5% of Latinos19 and 12.2–32.7% of the Japanese and Chinese population20–22 have low vision or blindness due to pathologic myopia.

Recent studies have shown the differences in structural and optical properties of eyes among different ethnicities23–25. As complications of myopia occur due to ocular stretching, and with the evidence that the ocular shape can be different among different ethnic groups23, it is possible that myopia related pathologic lesions may vary with different ethnic groups. Most of the studies investigated pathologic myopia in older adults, but not in children and young adults who when identified at an early age, can provide some insights into management options. Prevalence of myopia in Indian children a decade ago based on two publications was 4.1% in a rural population26 and 7.4% in urban population27 which increased to 13.1% in year 201528. The prevalence and patterns of pathologic myopia manifestation in children and young adults in Indian population remains unclear. The aim of this study was to investigate patterns of high and pathologic myopia (at a tertiary eye care centres) in Indian children and young adults.

Results

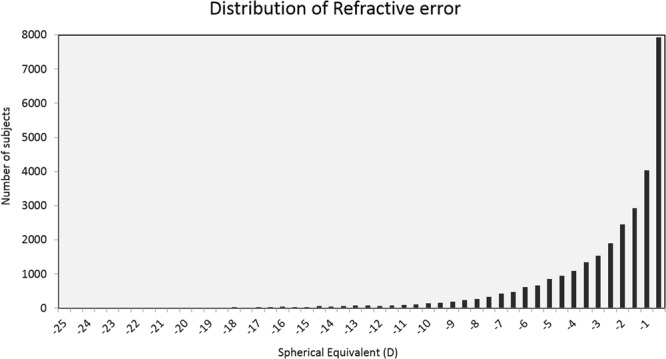

The mean age of the individuals whose data was used in this study was 23.31 ± 7.21 years (range 10 to 40 years). Table 1 shows the distribution of individuals based on age, refractive error and gender. Majority of the individuals were in the age group of 21–30 years (47.85%) followed by 11–20 years (33.69%) and 31–40 years (18.46%). Majority of the eyes had mild myopia (65%) followed by moderate myopia (16.0%), high myopia (14.4%) and severe myopia (4.6%) as shown in Fig. 1. The number of males were 16,467 (55.64%).

Table 1.

Distribution of myopes based on age, gender and refractive error.

| Number of subjects | Mild (−0.50 to −3.00 D) |

Moderate (<−3.00 to −5.00 D) |

High (<−5.00 to −10.00 D) |

Severe (<−10.00 to −25.00 D) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| All | 29,592 | 19,229 (65.0) | 4,747 (16.0) | 4,263 (14.4) | 1,353 (4.6) |

| Age | |||||

| 11–20 | 9,969 | 6,355 (63.7) | 1,791 (18) | 1,345 (13.5) | 478 (4.8) |

| 21–30 | 14,160 | 8,893 (62.8) | 2,254 (15.9) | 2,380 (16.8) | 633 (4.5) |

| 31–40 | 5,463 | 3,981 (72.9) | 702 (12.9) | 538 (9.8) | 242 (4.4) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 16,467 | 11,098 (67.4) | 2,483 (15.1) | 2,163 (13.1) | 723 (4.4) |

| Female | 13,125 | 8,131 (62.0) | 2,264 (17.2) | 2,100 (16.0) | 630 (4.8) |

Figure 1.

Distribution of myopes based on degree of refractive error (D-Dioptres).

Table 2 details the distribution of pathologic lesions on the posterior globe in different age groups and on gender basis. Among different pathologic lesions, lattice degeneration was the most common (2.65%, 95% CI- 2.5% to 2.8%) followed by tessellated fundus (2.07%, 95% CI-1.9% to 2.2%), WWOP (1.17%, 95% CI- 1% to 1.3%) and macular hole (1.16%, 95% CI- 1–1.3%). CNVM/CNV was least common and present only in 0.08% (95% CI- 0.1% to 0.1%) of total myopes. CRA, staphyloma and RD, which are among the leading sight threatening pathologic lesions, were found in 1.1% (95% CI- 1% to 1.2%), 0.15% (95% of CI- 0.1% to 0.2%) and 0.16% (95% CI- 0.1% to 0.2%) of total myopes, respectively. CRA, CNVM, posterior staphyloma and RD were more common in 36–40 years age group. There was no difference in pattern of pathologic lesions between males and females (P = 0.51, independent t-test) as shown in the Table 2. Among all myopes, 4.3% (95% CI- 4.1% to 4.5%) of them had pathologic myopia. Myopes in the age group of 21–25 years had the highest proportion of pathologic myopia lesions (4.9%, 95% CI- 4.4% to 5.4%) while the lowest proportion was seen in 11–15 years of age group (2.7%, 95% CI- 2.2% to 3.2%). WWP was present in less number of myopes (0.34%, 95% CI- 0.3% to 0.4%) compared to WWOP (1.17%, 95% CI- 1% to 1.3%).

Table 2.

Patterns of various myopic fundus lesions among myopes according to age distribution and gender.

| Age group (years) | Median (IQR) | Tessellation% (95% CI) | White without pressure | White with pressure | Lattice degeneration | Atrophy | Hole | CNVM/CNV | Staphyloma | RD | PM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 29,592 | 2.07% (1.9, 2.2) |

1.17% (1, 1.3) |

0.34% (0.3, 0.4) |

2.65% (2.5, 2.8) |

1.1% (1, 1.2) |

1.16% (1, 1.3) |

0.08% (0.1, 0.1) |

0.15% (0.1, 0.2) |

0.16% (0.1, 0.2) |

4.3% (4.1, 4.5) |

| 11–15 (N = 4338) | −2 (−1, −0.75) |

3.3% (2.8, 3.9) |

0.9% (0.6, 1.2) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.3) |

1.4% (1.1, 1.8) |

1.1% (0.8, 1.4) |

0.6% (0.4, 0.9) |

0% (0, 0.1) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

2.7% (2.2, 3.2) |

| 16–20 (N = 5631) | −2 (−1, −4) |

1.8% (1.5, 2.2) |

1.6% (1.3, 1.9) |

0.6% (0.4, 0.8) |

2.5% (2.1, 2.9) |

1.3% (1, 1.7) |

1% (0.8, 1.3) |

0.1% (0, 0.1) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.3) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.3) |

4.2% (3.7, 4.8) |

| 21–25 (N = 7898) | −2.25 (−1, −4.75) |

1.9% (1.6, 2.2) |

1.5% (1.3, 1.8) |

0.5% (0.3, 0.6) |

3.6% (3.1, 4) |

0.8% (0.6, 1) |

1.6% (1.3, 1.8) |

0% (0, 0.1) |

0.1% (0, 0.1) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.3) |

4.9% (4.4, 5.4) |

| 26–30 (N = 6262) | −1.62 (−0.75, −0.75) |

1.4% (1.1, 1.7) |

1% (0.8, 1.3) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.3) |

3% (2.6, 3.4) |

1% (0.8, 1.3) |

1.3% (1, 1.5) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

0.1% (0, 0.1) |

4.6% (4.1, 5.2) |

| 31–35 (N = 3156) | −1.5 (−0.75, −3.25) |

2% (1.5, 2.4) |

0.6% (0.3, 0.8) |

0.2% (0, 0.3) |

2.2% (1.7, 2.7) |

1.4% (1, 1.8) |

1% (0.7, 1.4) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

0.2% (0, 0.3) |

0.2% (0, 0.3) |

4.2% (3.5, 4.9) |

| 36–40 (N = 2307) | −1.25 (−0.75, −2.75) |

2.6% (1.9, 3.2) |

0.5% (0.2, 0.8) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

2% (1.4, 2.5) |

1.5% (1, 2) |

1% (0.6, 1.5) |

0.3% (0.1, 0.5) |

0.4% (0.1, 0.6) |

0.3% (0.1, 0.5) |

4.6% (3.8, 5.5) |

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male (N = 16467) | 2% (1.8, 2.3) |

2.1% (1.9, 2.3) |

1.2% (1, 1.4) |

0.4% (0.3, 0.5) |

2.6% (2.4, 2.9) |

1.2% (1, 1.4) |

1.2% (1, 1.4) |

0.1% (0, 0.1) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.2) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.3) |

4.4% (4.1, 4.8) |

| Female (N = 13125) |

2% (1.8, 2.2) |

2% (1.8, 2.2) |

1.1% (0.9, 1.3) |

0.3% (0.2, 0.4) |

2.7% (2.4, 3) |

1% (0.8, 1.1) |

1.1% (0.9, 1.3) |

0.1% (0, 0.1) |

0.1% (0.1, 0.2) |

0.1% (0.1, 0.2) |

4.1% (3.8, 4.5) |

In table, CNVM/CNV, RD and PM represent choroidal neovascular membrane/choroidal neovascularization, retinal detachment and pathological myopia, respectively.

Single eye analysis (only right eye analysed of the two eyes) showed 2.5% of myopes to have pathologic myopia. Whilst tessellation of fundus and lattice were observed in majority of patients, the occurrence of CNVM was much lower, a trend similar to what observed when both eyes were considered for analysis. Retinal holes, CRA, staphyloma and RD were present even in mild and moderate myopia groups as shown in Table 3. However, proportion of myopes having staphyloma and RD increased with the degree of myopia. Staphyloma was four times more common in severe myopes (0.4%) than in mild myopes (0.1%).

Table 3.

Prevalence pattern of different pathologic myopia lesions among myopes in right eye.

| Grades of Myopia | N | Tessellation % (95%CI) | White without pressure | White with pressure | Lattice degeneration | Atrophy | Hole | CNVM/CNV | Staphyloma | RD | PM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 29,529 | 2% (1.8, 2.2) |

0.9% (0.8, 1) |

0.3% (0.2, 0.3) |

1.8% (1.7, 2) |

0.3% (0.3, 0.4) |

0.7% (0.6, 0.8) |

0% (0, 0.1) |

0.1% (0.1, 0.1) |

0.1% (0.1, 0.1) |

2.5% (2.3, 2.7) |

| <−0.50 to −3.00 D | 20,053 | 2% (1.8, 2.2) |

1% (0.9, 1.2) |

0.3% (0.3, 0.4) |

1.9% (1.7, 2.1) |

0.3% (0.2, 0.4) |

0.7% (0.6, 0.9) |

0% (0, 0.1) |

0.1% (0, 0.1) |

0.1% (0.1, 0.1) |

2.5% (2.3, 2.8) |

| <−3.00 to −5.00 D | 4,567 | 1.5% (1.1, 1.8) |

0.8% (0.6, 1.1) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.3) |

1.9% (1.5, 2.3) |

0.4% (0.2, 0.5) |

0.7% (0.5, 0.9) |

0% (0, 0) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

0.1% (0, 0.1) |

2.6% (2.1, 3.1) |

| <−5.00 to −10.00 D | 3,860 | 2.2% (1.7, 2.6) |

0.5% (0.3, 0.7) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

1.5% (1.1, 1.9) |

0.4% (0.2, 0.6) |

0.5% (0.3, 0.7) |

0.1% (0, 0.2) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.4) |

0.2% (0.1, 0.4) |

2.3% (1.9, 2.8) |

| <−10.00 to −25.00 D | 1,112 | 2.4% (1.5, 3.3) |

0.2% (−0.1, 0.4) |

0.1% (−0.1, 0.3) |

1.3% (0.6, 1.9) |

0.3% (0, 0.6) |

0.4% (0.1, 0.8) |

0% (0, 0) |

0.4% (0, 0.7) |

0.2% (−0.1,0.4) |

2.2% (1.3, 3) |

In table, CNVM/CNV, RD and PM represent Choroidal Neovascular Membrane, Retinal Detachment and Pathological Myopia respectively.

Discussion

Among different types of refractive errors, we found myopia in 47.4% of patients, high myopia in 6.8% and pathologic myopia in 2.2%. However, among only myopes, high myopia was found in 14.4% and pathologic myopia in 4.3%. Children between 10–15 years of age group had lowest proportion (2.7%) while adults between age group 25–30 years had highest proportion (4.9%) of pathologic myopia. Various pathologic lesions associated with myopia were found across all grades of myopia indicating that pathologic myopia lesions also exist in low grades of myopia (2.5% in low myopes vs. 2.2% in severe myopes). Lattice degeneration was the most frequent (2.7%) and CNVM/CNV was the least frequent lesion (0.08%) found in myopes.

Our result of 2.2% of pathologic myopia among patients with different types of refractive error lies within the prevalence reported in East Asian (Beijing Eye Study (3.1%)9, Shihpai Eye Study (3.0%)7 and Hisayama study (1.7%)10) and Caucasian populations (Blue Mountain Eye Study (1.2%)12). The Shihpai Eye Study conducted in Taiwan has defined the pathologic myopia taking into account both refractive error and axial length whereas our study has defined pathologic myopia based on fundus findings only. Direct comparison of our study results with Beijing, Shihpai, Hisayama and Blue Mountain studies may not be appropriate because of the following two reasons: Our study is a hospital based study while the other studies were population based study. Secondly, population included in these studies were elderly (≥49 years in Blue Mountain Eye Study, ≥65 years in Shihpai Eye Study, >40 years in Hisayama study and >40 years in Beijing Eye Study) while the current study included individuals within the age group of 10–40 years. In our study, the overall number of individuals with high myopia (<−5.0 D to −10.0 D) were found to be 6.8% which is higher than prevalence reported in Beijing Eye Study (3.3%), Hisayama study (5.7%) and Blue Mountain Eye Study (2.2%). In patients between 11–20 years of age, the prevalence of high myopia was found to be 2.15% which is significantly lower than the results reported by the study done in Singapore (7.3%)29 in adolescent children of age 14 years.

Beijing Eye Study showed the prevalence of staphyloma to be 1.6% and chorio-retinal atrophy to be 3.1%. In 2008, Lai et al.30 reported the prevalence of staphyloma to be 7.7%, chorio-retinal atrophy to be 2.7%, Lacquer crack to be 1.8% and Fuch’s spot to be 0.3% in the posterior pole. In the similar age group among myopic patients, the pattern of these pathologic lesion in our study is quite low, 0.15% of staphyloma and 1.1% of chorio-retinal atrophy. Proportionately, lattice degeneration stands highest (2.65%) among all types of pathologic lesions in Indian population.

Unlike other studies (Beijing, Shihpai and Blue Mountain Eye Study), the current study does not show a trend of increased prevalence of pathologic myopia with age, except for a significant difference between the ones aged 11–15 years and the remaining (2.7% in younger children vs. >4% in those aged >15 years). With the increasing age, several structural and functional changes occur in the posterior part of the eye31,32. A study conducted with OCT has shown thinning of retina with ageing33. As the age advances, lacquer cracks extend, increasing the area of atrophy in the macular area34. This could be the reason for increased prevalence of myopic maculopathy with age. In our study, the upper age limit is 40 years and this might have delivered lesser difference in proportion of patterns of various myopia complications between younger and older age group within 10–40 years. The results of current study also show no difference in the pattern of pathologic lesions with increase in grades of myopic refractive error. Beijing Eye Study had found prevalence of myopic retinopathy significantly increased with increasing refractive error, from 3.8% in eyes with <−4.0 D to 89.6% in eyes with at least −10.0 D. The Hisayama study also reported an increase in prevelence of pathologic lesions with increase in degree of myopia (myopic retinopathy increased from 0.3% in eyes with refractive error <−6.0 D to 36.8% in eyes with refractive error of at least −10.0 D). However, on analysing each pathologic lesion independently, we found that the proportion of staphyloma and RD increased with grades of myopia.

There was no difference in the pattern of pathologic myopia between male and female in our study, similar to the results from Blue Mountains and Beijing Eye Study. However, Hisayama study in Japanese elderly population reported female to have higher prevalence than males (2.2% vs. 1.2%). Similar outcomes were reported by Ito-Ohara et al. and Gozum et al. from Japan and Turkey respectively35,36.

The current study included 29,592 myopes for the analysis, which is so far, the highest number of patients enrolled for a study on patterns of pathologic myopia. This is one of the biggest strength of this study. In most of the East Asian and Caucasian studies, prevalence of pathologic myopia was seen in elderly population but we reported its prevalence in children and young adults. This study has some limitations. Firstly, our study is hospital based study where most of the patients’ visit only if they have some vision related problem. Secondly, the pattern of pathologic lesions were reported only among myopes. Thus, the results obtained in this specific age group may be an overestimated value i.e. proportion of people with myopia lesions. Considering that the few changes associated with pathologic myopia such as chorio-retinal atrophy and myopic CNV usually develop later in life, the use of data from 10 to 40 years age in this study does not give insights on overall proportion of myopia lesions in elderly population. Due to retrospective nature of the study, our study failed to analyse the axial length measurements and retinal Optical Coherence Tomography findings and classify the severity of the fundus changes based on the META-PM (META-analysis for Pathologic Myopia) study. Hence comparison of the results from this study with other studies and the generalisability of the outcomes of this study should be made with caution. Further population based studies are needed to understand the actual prevalence of pathologic myopia and its association with axial length. The relationship between various lesions of posterior globe with visual acuity and describing lesions based on its location were beyond the scope of this paper.

In conclusion, various pathologic lesions of myopia were found in 4.3% of myopes in our database. Although, the overall proportion of pathologic myopia was similar among all degrees of myopia, lesions like staphyloma and retinal detachment increased with increasing degree of myopia. The results from this study indicates the necessity for careful peripheral fundus examinations irrespective of degree of myopia for better management and prognostic purposes. Future studies are needed to understand the age appropriate strategies for management of pathologic myopia so that visually debilitating lesions like retinal detachment and CNVM/CNV can be prevented or strategically managed.

Methodology

A retrospective analysis of patient’s electronic medical record (EMR), who visited any of the four tertiary centres of the L V Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI), between 1st January 2016 to 31st December 2016, was conducted. Although, the four tertiary centres are located in four different geographical location of India, viz Bhubaneswar, Orissa; Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh; Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh; and Hyderabad, Telangana, the involved 29,592 patients came from different states panning from east to west and north to south India. Every single patient had signed informed general consent form prior to routine clinical examinations approving the use of their data for research purposes. The study was approved by institutional ethics committee of LVPEI, Hyderabad and procedures were in accordance to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

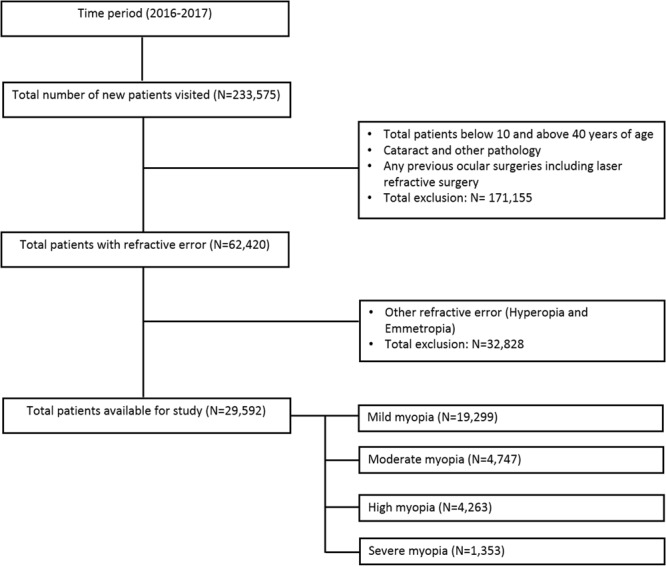

A total of 233,575 patients visited for the first time during the chosen one-year study time period. To avoid the effect of any age-related changes on the refractive error like emmetropization or cataract, only patients above 10 years and below 40 years of age were included in the study. Any patients who either had media opacity or underwent any form of ocular surgery that could influence the refractive error were excluded from the study (N = 171,155) leaving behind 62,420 patients of which 29,592 were myopes. Figure 2 represents the flowchart of patient’s data pool at different level of inclusion and exclusion stages.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of patient data pool at various levels of inclusion and exclusion stages.

Demographic data such as age and gender, and clinical data such as refractive error and retinal signs as documented in EMR by treating ophthalmologist using indirect ophthalmoscope and slit lamp biomicroscope were collected. Medical records were reviewed to identify various pathologic myopia lesions, namely tessellation of fundus, white without pressure (WWOP), white with pressure (WWP), lattice degeneration, chorio-retinal atrophy (CRA), retinal holes, choroidal neovascularisation (CNVM/CNV), posterior staphyloma and retinal detachment (RD). Considering that the CNVM/CNV can also occur due to causes other than myopia, viz. idiopathic CNVM and punctate inner choroidopathy, care was taken to exclude such findings. Pathologic myopia was defined as the presence of any one of the following retinal signs: lattice degeneration, CRA, retinal holes, CNVM/CNV, posterior staphyloma or RD16.

The prevalence of high myopia and pathologic myopia based on age, gender and grades of myopia was expressed in percentage (%). Data of both the eyes were collected and if above mentioned signs were present in at least one of the eye, then patient was labelled to have pathologic myopia lesion. To understand the patterns of pathologic lesions based on refractive error, data of only right eye were analysed. Myopia was divided into 4 categories i.e. mild, moderate, high and sever where mild myopia was defined as spherical equivalent (SE) of <−0.50 D to −3.00 D, moderate myopia as <−3.00 D to −5.00 D, high myopia as <−5.00 D to −10.00 D and severe myopia as <−10.00 D and above5.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the eyeSmart EMR team at L V Prasad Eye Institute, especially Dr. Anthony Vipin Das, Gaddamanugu Yasaswi, Vadelpalli Ranganath and Mohammed Pasha for their support in retrieving the data. We also thank Mr. Peguda Hari for his initial inputs during data extraction and analysis.

Author Contributions

R.D. drafted and reviewed the manuscript; A.G. collected and analysed data; R.N. critically reviewed the manuscript and P.K.V. conceptualized, analysed and critically reviewed the manuscript

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rohit Dhakal and Abhilash Goud contributed equally.

References

- 1.Pan CW, Dirani M, Cheng CY, Wong TY, Saw SM. The age-specific prevalence of myopia in Asia: a meta-analysis. Optom Vis Sci. 2015;92:258–266. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourne RR, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e339–349. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashemi H, et al. Global and regional estimates of prevalence of refractive errors: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2018;30:3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.joco.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan CW, Ramamurthy D, Saw SM. Worldwide prevalence and risk factors for myopia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holden BA, et al. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohno-Matsui K, Lai TY, Lai CC, Cheung CM. Updates of pathologic myopia. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;52:156–187. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SJ, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of myopic maculopathy in elderly Chinese: the Shihpai eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:4868–4873. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao LQ, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of myopic retinopathy in a rural Chinese adult population: the Handan Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1199–1204. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu HH, et al. Prevalence and progression of myopic retinopathy in Chinese adults: the Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1763–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asakuma T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for myopic retinopathy in a Japanese population: the Hisayama Study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1760–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attebo K, Ivers RQ, Mitchell P. Refractive errors in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1066–1072. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vongphanit J, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Prevalence and progression of myopic retinopathy in an older population. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:704–711. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fricke TR, et al. Global cost of correcting vision impairment from uncorrected refractive error. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:728–738. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.104034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith TS, Frick KD, Holden BA, Fricke TR, Naidoo KS. Potential lost productivity resulting from the global burden of uncorrected refractive error. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:431–437. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.055673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klaver CC, Wolfs RC, Vingerling JR, Hofman A, de Jong PT. Age-specific prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in an older population: the Rotterdam Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:653–658. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong TY, Ferreira A, Hughes R, Carter G, Mitchell P. Epidemiology and disease burden of pathologic myopia and myopic choroidal neovascularization: an evidence-based systematic review. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:9–25 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cedrone C, et al. Incidence of blindness and low vision in a sample population: the Priverno Eye Study, Italy. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:584–588. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01898-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cedrone C, et al. Prevalence of blindness and low vision in an Italian population: a comparison with other European studies. Eye (Lond). 2006;20:661–667. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotter SA, et al. Causes of low vision and blindness in adult Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1574–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu L, et al. Causes of blindness and visual impairment in urban and rural areas in Beijing: the Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(1134):e1131–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwase A, et al. Prevalence and causes of low vision and blindness in a Japanese adult population: the Tajimi Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1354–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada M, et al. Prevalence of visual impairment in the adult Japanese population by cause and severity and future projections. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:50–57. doi: 10.3109/09286580903450346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verkicharla PK, Suheimat M, Schmid KL, Atchison DA. Differences in retinal shape between East Asian and Caucasian eyes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2017;37:275–283. doi: 10.1111/opo.12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang P, et al. Peripheral refraction in different ethnicities. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:6059–6065. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan NS, Gilmartin B, Wildsoet CF, Dunne MC. Posterior retinal contour in adult human anisomyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2152–2162. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dandona R, et al. Refractive error in children in a rural population in India. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:615–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murthy GV, et al. Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:623–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saxena R, et al. Prevalence of myopia and its risk factors in urban school children in Delhi: the North India Myopia Study (NIM Study) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samarawickrama C, et al. Myopia-related optic disc and retinal changes in adolescent children from singapore. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2050–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai TY, Fan DS, Lai WW, Lam DS. Peripheral and posterior pole retinal lesions in association with high myopia: a cross-sectional community-based study in Hong Kong. Eye (Lond). 2008;22:209–213. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao H, Hollyfield JG. Aging of the human retina. Differential loss of neurons and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saka N, et al. Long-term changes in axial length in adult eyes with pathologic myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150:562–568 e561. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alamouti B, Funk J. Retinal thickness decreases with age: an OCT study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:899–901. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.7.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohno-Matsui K, Tokoro T. The progression of lacquer cracks in pathologic myopia. Retina. 1996;16:29–37. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito-Ohara M, Seko Y, Morita H, Imagawa N, Tokoro T. Clinical course of newly developed or progressive patchy chorioretinal atrophy in pathological myopia. Ophthalmologica. 1998;212:23–29. doi: 10.1159/000027254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gozum N, Cakir M, Gucukoglu A, Sezen F. Relationship between retinal lesions and axial length, age and sex in high myopia. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997;7:277–282. doi: 10.1177/112067219700700313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]