Summary

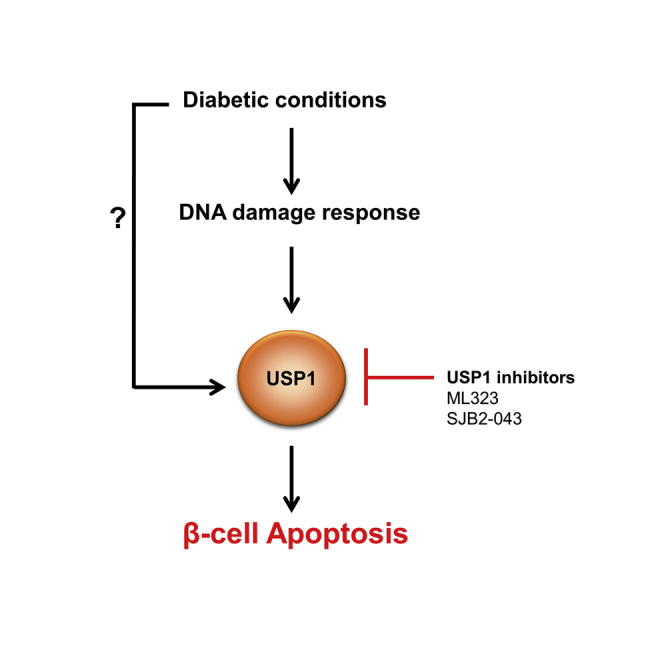

Impaired pancreatic β-cell survival contributes to the reduced β-cell mass in diabetes, but underlying regulatory mechanisms and key players in this process remain incompletely understood. Here, we identified the deubiquitinase ubiquitin-specific protease 1 (USP1) as an important player in the regulation of β-cell apoptosis under diabetic conditions. Genetic silencing and pharmacological suppression of USP1 blocked β-cell death in several experimental models of diabetes in vitro and ex vivo without compromising insulin content and secretion and without impairing β-cell maturation/identity genes in human islets. Our further analyses showed that USP1 inhibition attenuated DNA damage response (DDR) signals, which were highly elevated in diabetic β-cells, suggesting a USP1-dependent regulation of DDR in stressed β-cells. Our findings highlight a novel function of USP1 in the control of β-cell survival, and its inhibition may have a potential therapeutic relevance for the suppression of β-cell death in diabetes.

Subject Areas: Biochemical Mechanism, Endocrinology, Cell Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Genetic and chemical inhibition of USP1 promoted β-cell survival

-

•

USP1 inhibitors blocked β-cell death in human islets without affecting β-cell function

-

•

USP1 inhibition reduced DDR signals in stressed β-cells

Biochemical Mechanism; Endocrinology; Cell Biology

Introduction

Loss of function and/or mass of insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells is a hallmark of both type 1 and 2 diabetes (T1D/T2D) (Butler et al., 2003, Kurrer et al., 1997, Mathis et al., 2001, Rhodes, 2005, Vetere et al., 2014). Pancreatic β-cell death is a critical pathogenic factor contributing to the declined β-cell mass in both T1D and T2D (Ardestani et al., 2014, Butler et al., 2003, Kurrer et al., 1997, Marselli et al., 2014, Masini et al., 2009, Mathis et al., 2001, Meier et al., 2005, Rahier et al., 2008, Rhodes, 2005, Tomita, 2010). Also, β-cell dedifferentiation (Cinti et al., 2016, Jeffery and Harries, 2016, Talchai et al., 2012) and impaired adaptive proliferation (Ardestani and Maedler, 2018, Tiwari et al., 2016) have been proposed as potential additional causes for this diminished β-cell mass in diabetes. Although immune-cell-mediated events predominate in T1D (Chatenoud, 2010), metabolic factors such as elevated levels of glucose, fatty acids, and islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), alongside with pro-inflammatory cytokines, drive β-cell loss and dysfunction in T2D (Alejandro et al., 2015, Ardestani et al., 2018, Donath et al., 2013, Haataja et al., 2008, Huang et al., 2007, Maedler et al., 2002, Poitout and Robertson, 2008, Robertson et al., 2004, Yuan et al., 2017). Excessive β-cell death is commonly seen in the islets of both patients with T1D and lean and obese patients with T2D as determined by multiple complementary approaches (Butler et al., 2003, Masini et al., 2009, Meier et al., 2005, Tomita, 2010). Counter-intuitively, higher levels of β-cell apoptosis in autopsy pancreases from patients with established diabetes inversely correlate with the insulin-positive β-cell area. But even at a pre-diabetic stage, i.e., in at-risk individuals who progressed to T1D, β-cell death is evident and accompanied with diminished insulin secretion (Herold et al., 2015). Correspondingly, in patients with impaired glucose tolerance before T2D diagnosis, loss of β-cells is apparent and correlates with elevated fasting glucose levels (Ritzel et al., 2006); this gradually progresses when hyperglycemia is established and β-cells are unable to sustain insulin production under a higher metabolic demand. Indeed, pancreatic β-cells show a relatively higher susceptibility to apoptosis together with lower stress-induced protective responses compared with many other cell types, including the neighboring pancreatic α-cells. For instance, a recent proteomic analysis shows a very weak induction of β-cell's reactive oxygen species (ROS)-detoxifying enzymes in response to inflammatory assault (Gorasia et al., 2015). This confirms previous observations showing very low levels of protective anti-oxidative enzymes in β-cells (Grankvist et al., 1981, Lenzen, 2008, Lenzen et al., 1996, Tiedge et al., 1997). Consistently, human β-cells are much more sensitive to apoptosis than α-cells in response to T2D-related metabolic stressors (Marroqui et al., 2015). All these seem to represent an “Achilles heel” through which diabetogenic stimuli trigger rapid β-cell death and accelerate the collapse in response to environmental stress and demand.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a highly regulated key intracellular protein degradation pathway, which consists of an enzymatic cascade controlling protein ubiquitination and has important functions in several essential biological processes, such as cell survival, proliferation, development, and DNA damage response (DDR) (Schmidt and Finley, 2014). The UPS is a process of post-translational modification of targeted protein by covalent attachment of one or more ubiquitins to lysine residues by an E3 ubiquitin ligase. This is antagonized by enzyme deubiquitinases (DUBs), such as ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs). The UPS is primarily responsible for the degradation and clearance of misfolded or damaged proteins as well as of dysfunctional organelles, which compromise cellular homeostasis. Abnormalities in the UPS machinery have been linked to the pathogenesis of many diseases, including cancer, immunological and neurological disorders (Frescas and Pagano, 2008, Schmidt and Finley, 2014, Zheng et al., 2016), as well as β-cell failure in diabetes (Broca et al., 2014, Bugliani et al., 2013, Costes et al., 2011, Costes et al., 2014, Hartley et al., 2009, Hofmeister-Brix et al., 2013, Kaniuk et al., 2007, Litwak et al., 2015). A member of the USP family, ubiquitin-specific protease 1 (USP1), is one of the best known DUBs responsible for removing ubiquitin from target proteins and thus influences several cellular processes such as survival, differentiation, immunity and DDR (Garcia-Santisteban et al., 2013, Liang et al., 2014, Yu et al., 2017). Although USP1 was initially identified as a novel component of the Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway (Nijman et al., 2005), extensive subsequent studies revealed a pleotropic function of USP1 and identified novel interacting partners and signaling for USP1 action and regulation in normal physiological conditions and in disease states such as tumorigenesis (Garcia-Santisteban et al., 2013, Liang et al., 2014, Yu et al., 2017). An array-based assay identified reduced USP1 mRNA expression in islets from patients with T2D (Bugliani et al., 2013). As the consequent effects of USP1 in diabetes and especially in the pancreatic β-cell were completely unknown so far, we investigated the role and the mechanism of action of USP1 on β-cell survival under diabetic conditions using clonal β-cells and isolated primary human islets. Although USP1 protein expression was unchanged in a diabetic milieu, we identified a robust protective effect on β-cell survival by USP1 inhibition.

Results

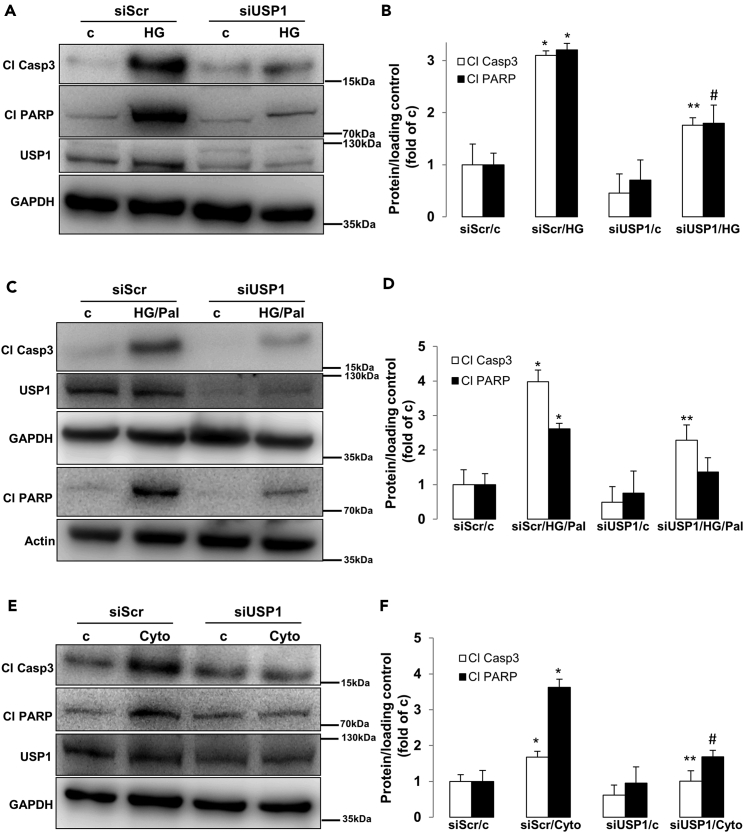

USP1 Knockdown Protects β-cells from Apoptosis Under Diabetic Conditions

Transcriptome analysis of islets isolated from healthy individuals as well as from patients with T2D showed consistent alteration of genes of UPS components, including members of the USP family such as USP1 (Bugliani et al., 2013). Because USP1 is involved in signaling pathways associated with DDR and survival (Liang et al., 2014), we aimed here to identify whether USP1 regulates apoptosis in β-cells under diabetogenic conditions. USP1 was expressed in protein lysates extracted from both human and mouse islets (data not shown) and INS-1E cells (Figure 1). The total protein level was not significantly changed in response to a pro-diabetic milieu in INS-1E cells (Figure 1). To evaluate the function of USP1 in the regulation of β-cell survival, USP1 was depleted in rat INS-1E β-cells by transfection with siUSP1 (Figure S1) and thereafter cultured long term with high glucose concentrations (glucotoxicity; Figures 1A and 1B), a combination of high glucose with saturated free fatty acid palmitate (glucolipotoxicity; Figures 1C and 1D), and a cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1 beta [IL-1β], interferon gamma [IFN-γ], and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]; Figures 1E and 1F). Consistent with our previous observations, long-term culture with elevated glucose, glucose/palmitate, and cytokines robustly induced β-cell apoptosis (Ardestani et al., 2014, Yuan et al., 2016a, Yuan et al., 2016b). Knockdown of USP1 markedly reduced the levels of glucose-, glucose/palmitate-, and cytokine-induced apoptosis as indicated by decreased levels of hallmarks of apoptosis, namely, caspase-3 and its downstream target poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage (Figures 1A–1F). These data indicate that loss of USP1 confers apoptosis resistance to β-cells against stress-induced cell death.

Figure 1.

USP1 Knockdown Protects β-Cell from Apoptosis Under Diabetic Conditions

(A–F) INS-1E cells were seeded at 300,000 cells/well and transfected with either control scrambled siRNA (siScr) or siRNA specific to USP1 (siUSP1) and treated with (A and B) 22.2 mM glucose (HG), (C and D) a mixture of 22.2 mM glucose and 0.5 mM palmitate (HG/Pal), or (E and F) pro-inflammatory cytokines (2 ng/mL recombinant human IL-1β, 1000 U/mL TNF-α, and 1000 U/mL IFN-γ; Cyto) for 2 days. Representative Western blots (A, C, and E) and quantitative densitometry analysis (B, D, and F) of cleaved caspase 3 (Cl Casp3) and cleaved PARP (Cl PARP) protein levels are shown. Data are pooled from at least three independent cell line experiments. Data show means ±SEM. *p < 0.05 siScr treated compared with siScr control conditions. **p < 0.05 siUSP1-treated compared with siScr-treated conditions. #p = 0.05 compared with HG (B) or Cyto (F). See also Figure S1 for USP1 quantification.

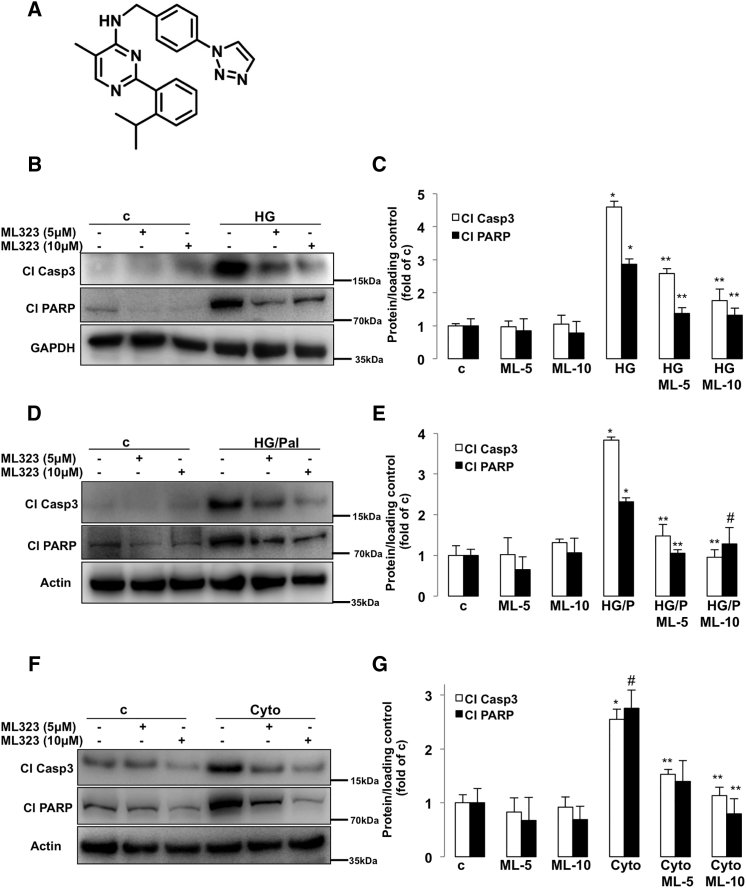

Small Molecule USP1 Inhibitors Block β-Cell Apoptosis Under Diabetic Conditions

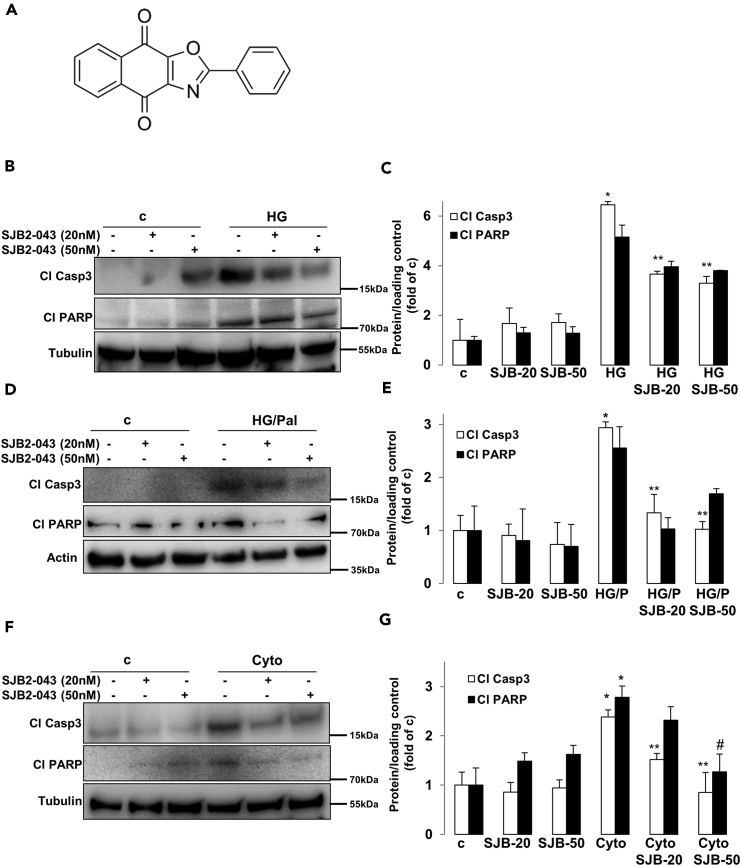

Several USP1 small molecule inhibitors have been developed recently. Quantitative high-throughput screen and subsequent medicinal chemistry identified compound ML323 (Figure 2A) as a highly potent selective inhibitor of USP1 with excellent specificity, when compared with other DUBs, deSUMOylase, deneddylase, and unrelated proteases (Dexheimer et al., 2010, Liang et al., 2014). ML323 was able to potently inhibit USP1 activity in a dose-dependent manner in several complementary in vitro assays as well as in cellular models as represented by increased monoubiquitination of USP1 known substrates proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and Fanconi anemia group D2 protein (FANCD2) (Dexheimer et al., 2010, Liang et al., 2014). Inhibition of USP1 was also confirmed in INS-1E cells treated with ML323 as indicated by the accumulation of ubiquitinated PCNA, a USP1 downstream substrate (Figures S2A and S2B). To confirm the anti-apoptotic action of USP1 loss obtained by the genetic approach, we used ML323 to block USP1 activity in INS-1E cells exposed to diabetic conditions. USP1 inhibition by ML323 at two concentrations (5 and 10 μM), which proved to be non-toxic at basal levels (data not shown), potently inhibited the induction of caspase-3 and PARP cleavage triggered by elevated glucose (Figures 2B and 2C), glucose/palmitate (Figures 2D and 2E), and cytokines (Figures 2F and 2G), further demonstrating the pro-apoptotic activity of USP1 in the presence of the diabetic milieu. Also, by using an ubiquitin-rhodamine-based high-throughput screening, Mistry et al. identified SJB2-043 (Figure 3A) as another potent selective small-molecule inhibitor of USP1. SJB2-043 blocked the deubiquitinating enzyme activity of USP1 in vitro with an IC50 in the nanomolar range (Mistry et al., 2013). To further confirm the utility of USP1 blockade in protecting β-cells from apoptosis, we tested the effect of SJB2-043 on β-cell survival in the presence of diabetogenic conditions. Consistent with our genetic and pharmacological approaches using siRNA against USP1 and the USP1 inhibitor ML323, USP1 inhibition by SJB2-043 at two concentrations (20 and 50 nM) attenuated β-cell apoptosis as represented by the robust reduction of cleaved caspase-3 and PARP induced by glucotoxicity (Figures 3B and 3C), glucolipotoxicity (Figures 3D and 3E), and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Figures 3F and 3G). Altogether, small molecule inhibitors of USP1 improved β-cell survival under diabetic conditions and recapitulated the β-cell protective effect of USP1 silencing.

Figure 2.

USP1 Inhibitor ML323 Blocks β-Cell Apoptosis Under Diabetic Conditions

(A) Chemical structure of ML323.

(B–G) About 500,000 INS-1E cells/well treated with or without USP1 inhibitor ML323 were exposed to 22.2 mM glucose (HG; B and C), a mixture of 22.2 mM glucose and 0.5 mM palmitate (HG/Pal; D and E), or pro-inflammatory cytokines (2 ng/mL recombinant human IL-1β, 1000 U/mL TNF-α, and 1000 U/mL IFN-γ; Cyto; F and G) for 2 days. Representative Western blots and quantitative densitometry analysis of cleaved caspase 3 (Cl Casp3) and cleaved PARP (Cl PARP) protein levels are shown. Data are pooled from at least three independent cell line experiments. Data show means ±SEM. *p < 0.05 treated compared with control conditions. **p < 0.05 inhibitor-treated compared with treated conditions. #p = 0.05 compared with HG/P (E) or untreated control (G) alone. See also Figure S2 for PCNA ubiquitination.

Figure 3.

USP1 Inhibitor SJB2-043 Blocks β-Cell Apoptosis Under Diabetic Conditions

(A) Chemical structure of SJB2-043.

(B–G) About 500,000 INS-1E cells/well treated with or without USP1 inhibitor SJB2-043 were exposed to 22.2 mM glucose (HG; B and C), a mixture of 22.2 mM glucose and 0.5 mM palmitate (HG/Pal; D and E), or pro-inflammatory cytokines (2 ng/mL recombinant human IL-1β, 1000 U/mL TNF-α, and 1000 U/mL IFN-γ; Cyto; F and G) for 2 days. Representative Western blots and quantitative densitometry analysis of cleaved caspase 3 (Cl Casp3) and cleaved PARP (Cl PARP) protein levels are shown. Data are pooled from at least three independent cell line experiments except for cl PARP in C (n = 2). Data show means ±SEM. *p < 0.05 treated compared with control conditions. **p < 0.05 inhibitor-treated compared with treated conditions. #p = 0.05 compared with Cyto (G) alone.

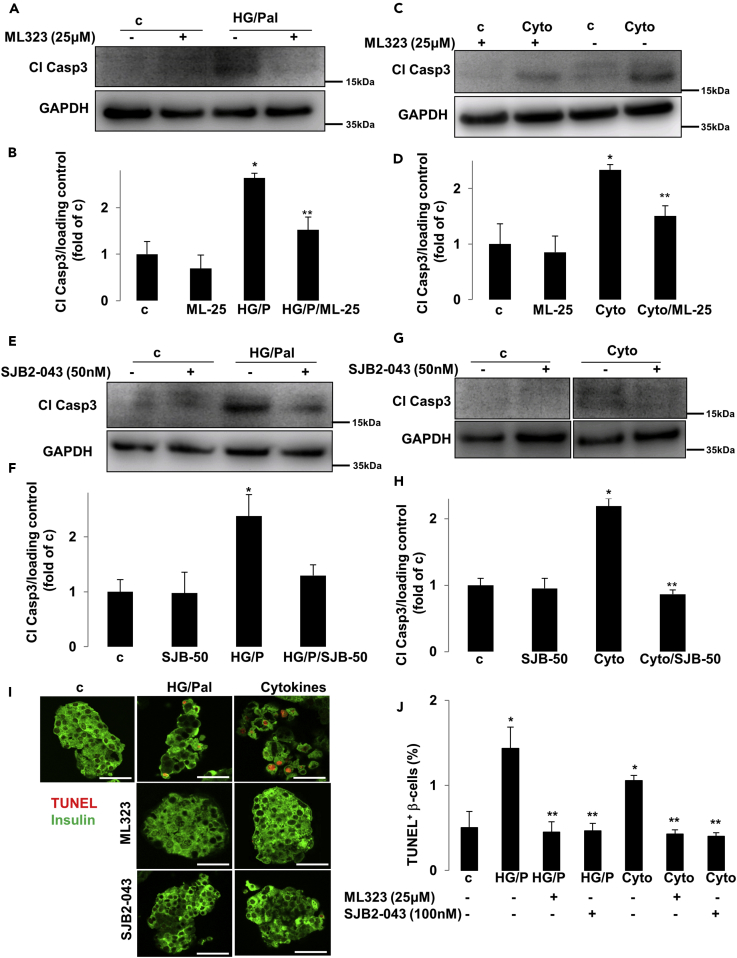

USP1 Inhibition Protects Human Islets from Apoptosis without Compromising Their Insulin Secretory Function

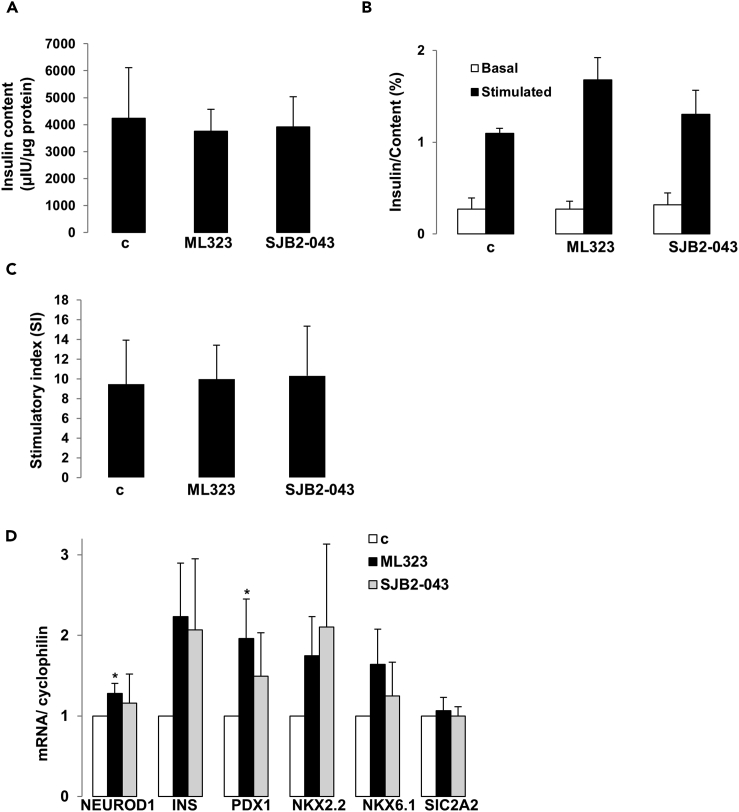

To test the efficacy of USP1 inhibitors in blocking β-cell apoptosis in human islets with physiologically more relevant properties for human disease, human islets isolated from nondiabetic organ donors were treated with USP1 inhibitors ML323 and SJB2-043 and then exposed to the diabetogenic milieu of glucolipotoxicity and pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IFN-γ. Caspase-3 cleavage triggered by high glucose/palmitate as well as by the mixture of cytokines was counteracted by ML323 in isolated human islets, confirmed independently by four batches of human islet preparations (Figures 4A–4D). Similar data were obtained using SJB2-043 as approach to target USP1 in isolated human islets (Figures 4E–4H). To confirm protection from apoptosis, in situ TUNEL together with insulin double-staining was performed to validate our Western blot data on the level of β-cells. Again, both USP1 inhibitors ML323 and SJB2-043 fully protected human islet β-cells from apoptosis induced by prolonged exposure to elevated glucose/palmitate and to the mixture of cytokines (Figures 4I and 4J), confirming the promising efficacy of USP1 inhibitors in rescuing human β-cells from apoptosis. Although strategies to interfere with the intracellular cell death mechanisms to halt β-cell failure in diabetes are highly promising, they should not compromise the insulin secretory function of pancreatic β-cells. As previously reported, modulation of key endogenous anti-apoptotic proteins in β-cells impairs β-cell function (Luciani et al., 2013). Therefore, we sought to determine whether the chemical blockade of USP1 has any impact on insulin secretion and expression of key β-cell maturation and identity genes. Therefore, we probed the influence of USP1 inhibition on the ability of human islets to secrete insulin in response to glucose. Human islets treated with ML323 and SJB2-043 showed no alteration in the intracellular insulin content (Figure 5A), and glucose-stimulate insulin secretion (GSIS) was maintained (Figures 5B and 5C), indicating that USP1 inhibition does not affect the human islet insulin secretory function. To determine whether USP1 inhibitors caused a loss of β-cell identity or de-differentiation, expression of functional genes, including insulin (INS), key β-cell transcription factors (PDX1, NEUROD1, NKX2.2, and NKX6.1), as well as the critical β-cell glucose transporter (SlC2A2), were measured by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in human islets. Our data showed that not only all genes were preserved in USP1 inhibitors-treated human islets cells but also NEUROD1 and PDX1 were significantly increased by ML323 (Figure 5D), suggesting full preservation of β-cell function and functional identity genes upon inhibition of USP1 in human islets. Our data show that inhibition of USP1 efficiently blocked human β-cell apoptosis without compromising function.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of USP1 Promotes β-Cell Survival in Isolated Human Islets

(A–J) Isolated human islets (150–200 islets/dish) treated with or without USP1 inhibitors ML323 or SJB2-043 were exposed to a mixture of 22.2 mM glucose and 0.5 mM palmitate (HG/Pal) (A, B, E, F, I, and J) or to pro-inflammatory cytokines (2 ng/mL recombinant human IL-1β and 1000 U/mL IFN-γ; Cyto; C, D, G–J) for 2 days. Representative Western blots and quantitative densitometry analysis of cleaved caspase 3 (Cl Casp3) protein levels are shown. (G) All lanes are from the same gel but were run noncontiguously. (I and J) Human pancreatic islets were fixed, paraffin embedded, and stained for the TUNEL assay and insulin. Representative images (I) and quantitative percentage of TUNEL-positive β-cells (J) are shown. Scale bars represent 50 μm. Data are pooled from at least three human islet preparations. Data show means ±SEM. *p < 0.05 stimuli treated compared with control conditions. **p < 0.05 inhibitor-treated compared with treated conditions.

Figure 5.

Impact of USP1 Inhibition on Insulin Content, Secretion, and Expression of Functional β-Cell Genes in Isolated Human Islets

(A–D) Isolated human islets were treated with or without USP1 inhibitors ML323 or SJB2-043 for 2 days (30 islets/dish for A–C; 150–200 islets/dish for D). (A) Insulin content analyzed after GSIS and normalized to whole islet protein. (B) Insulin secretion during 1-hr incubation with 2.8 (basal) and 16.7 mM glucose (stimulated), normalized to insulin content. (C) The insulin stimulatory index denotes the ratio of secreted insulin during 1-hr incubation with 16.7 and 2.8 mM glucose. (D) RT-PCR for NEUROD1, INS, PDX1, NKX2.2, NKX6.1, and SlC2A2, normalized to cyclophilin. Tubulin normalization delivered similar results. Pooled data are from four independent experiments from four different human islet donors. Data show means ±SEM. *p < 0.05 compared with control conditions.

USP1 Inhibition Suppressed the DNA Damage Response in Pancreatic β-cells

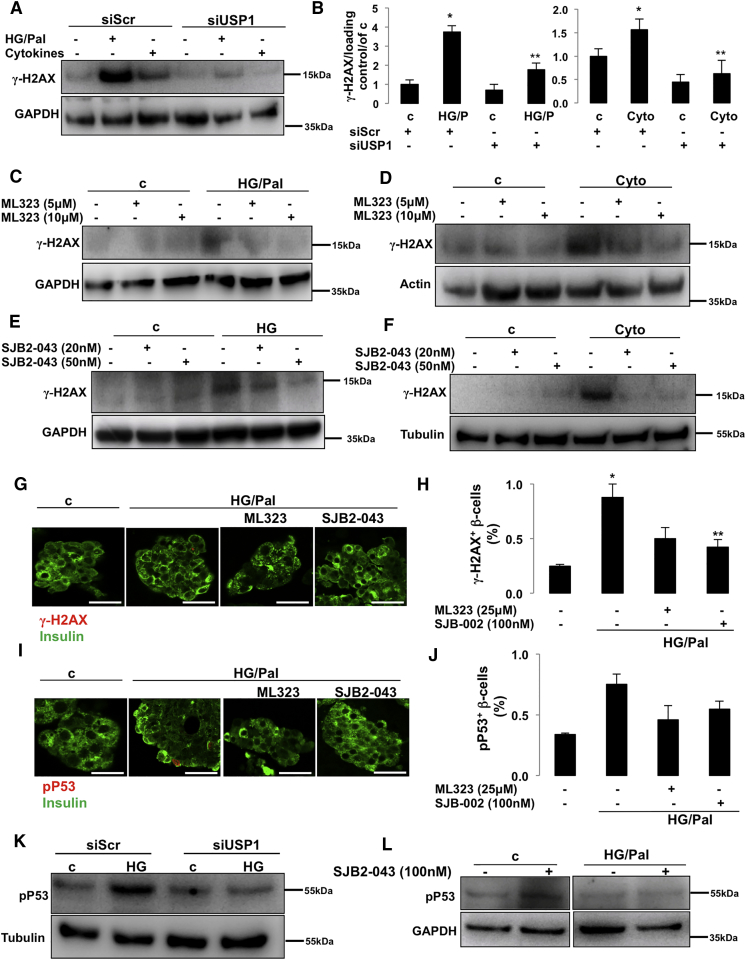

Complex intracellular networks, namely, the DDR, monitor genome integrity and stability by sensing DNA damage and controlling DNA repair pathways and damage tolerance processes (Polo and Jackson, 2011). In principle, if the level of DDR is greater than the cellular capacity, programmed cell death is activated to prevent cellular mutations and related abnormalities that contribute to tumorigenesis. However, DDR dysregulation leads to multiple pathological settings: extensive impairment of DDR leads to cancer with uncontrolled cell overgrowth, whereas extensive upregulation may precede neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases with specific cell loss (Jackson and Bartek, 2009, Shimizu et al., 2014). Several lines of evidence support the important function of USP1 in DDR processes (Cukras et al., 2016, Nijman et al., 2005, Ogrunc et al., 2016, Sourisseau et al., 2016). As DDR markers are highly elevated in human and rodent diabetic islets/β-cells in vitro and in vivo and correlate with β-cell death (Belgardt et al., 2015, Himpe et al., 2016, Nyblom et al., 2009, Oleson et al., 2014, Oleson et al., 2016, Tornovsky-Babeay et al., 2014), we sought to determine whether USP1 inhibition would modulate DDR under diabetic conditions. Histone H2AX is a histone H2A variant, which is essential for cell cycle arrest and activation of DNA repair processes upon double-stranded DNA breaks. Upon DNA damage, H2AX is rapidly phosphorylated at Ser139 by PI3K-like kinases, including ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR), and DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), and its phosphorylation generally referred to as γ-H2AX is universally considered as robust readout of DDR (Yuan et al., 2010). Consistent with previous studies (Belgardt et al., 2015, Himpe et al., 2016, Nyblom et al., 2009, Oleson et al., 2014, Oleson et al., 2016, Tornovsky-Babeay et al., 2014), glucolipotoxicity and pro-inflammatory cytokines strongly induced DDR (represented by γ-H2AX formation; Figures 6A and 6B) in INS-1E β-cells. USP1 knockdown significantly blocked γ-H2AX upregulation, correlating with its anti-apoptotic action in response to diabetogenic stimulation (Figures 6A and 6B). Consistently, both USP1 inhibitors ML323 and SJB2-043 markedly reduced γ-H2AX in all tested diabetic conditions (Figures 6C–6F). To confirm β-cell-specific regulation of DDR by USP1 inhibition in human islets, we quantified the number of γ-H2AX-positive β-cells in human islets treated with the diabetogenic milieu in the absence and presence of ML323 and SJB2-043. Glucolipotoxicity induced a number of γ-H2AX positive β-cells, whereas USP1 inhibitors significantly reduced it (Figures 6G and 6H), suggesting the β-cell-specific suppression of γ-H2AX in human islets. Transcription factor p53 is activated in response to several cellular stresses, including DNA damage, and plays a key function in coordinating cell-intrinsic responses to exogenous and endogenous stressors by promoting cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis (Meek, 2009, Reinhardt and Schumacher, 2012). P53 phosphorylation at serine 15 is the primary event during DDR (phosphorylated by DDR-related kinases ATM and ATR), which promotes both the accumulation and functional activation of p53 and is the surrogate readout of DDR activation (Loughery et al., 2014, Meek, 2009, Meek and Anderson, 2009). To further test the efficacy of USP1 inhibition to suppress DDR, we quantified the number of p-p53 (at Ser15)-positive β-cells in isolated human islets treated with USP1 inhibitors exposed to the diabetic conditions. The number of p-p53-positive β-cells increased in glucose/palmitate-treated human islets, whereas both ML323 and SJB2-043 reduced such p-p53-positive cells (Figures 6I and 6J). Also, chronically elevated glucose-induced p-p53 upregulation was strongly inhibited by USP1 knockdown in INS-1E cells (Figure 6K). In addition, glucose/palmitate-induced p53 phosphorylation was fully blunted in the presence of SJB2-043 (Figure 6L) in human islets, further supporting the attenuation of DDR markers in diabetic β-cells by USP1 inhibition.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of USP1-Suppressed DDR

(A, B, and K) INS-1E cells seeded at 300,000 cells/well were transfected with either control siScr or siUSP1 and treated with a mixture of 22.2 mM glucose and 0.5 mM palmitate (HG/Pal) or pro-inflammatory cytokines (2 ng/mL recombinant human IL-1β, 1000 U/mL TNF-α, and 1000 U/mL IFN-γ; Cyto). Representative Western blot (A and K) and quantitative densitometry analysis (B) of γ-H2AX and p-p53 proteins are shown.

(C–F) About 500,000 INS-1E cells/well treated with or without USP1 inhibitors ML323 (C and D) or SJB2-043 (E and F) were exposed to a mixture of 22.2 mM glucose and 0.5 mM palmitate (HG/Pal; C), 22.2 mM glucose (HG; E), or pro-inflammatory cytokines (2 ng/mL recombinant human IL-1β, 1000 U/mL TNF-α, and 1000 U/mL IFN-γ; Cyto; D and F) for 2 days. Data are pooled from at least three independent cell line experiments. Tubulin loading control in Figure 5F is re-used from the same experiment shown in Figure 3F.

(G–J and L) Isolated human islets (150–200 islets/dish) treated with or without USP1 inhibitors ML323 or SJB2-043 were exposed to a mixture of 22.2 mM glucose and 0.5 mM palmitate (HG/Pal) for 2 days. (G–J) Human pancreatic islets were fixed, paraffin embedded, and stained for γ-H2AX (G) or p-p53 (I) and insulin. Representative images (G and I) and quantitative percentage of γ-H2AX or p-p53-positive β-cells (H and J) are shown. Scale bars represent 50 μm. Data are pooled from three human islet preparations except for J (n = 2). (L) Representative Western blot of p-p53 protein is shown. All lanes are from the same gel but were run noncontiguously.

Data show means ±SEM. *p < 0.05 stimuli treated compared with control conditions. **p < 0.05 inhibitor-treated compared with treated conditions.

USP1 Inhibition Improves Survival and Lowers DDR in Diabetic β-cells

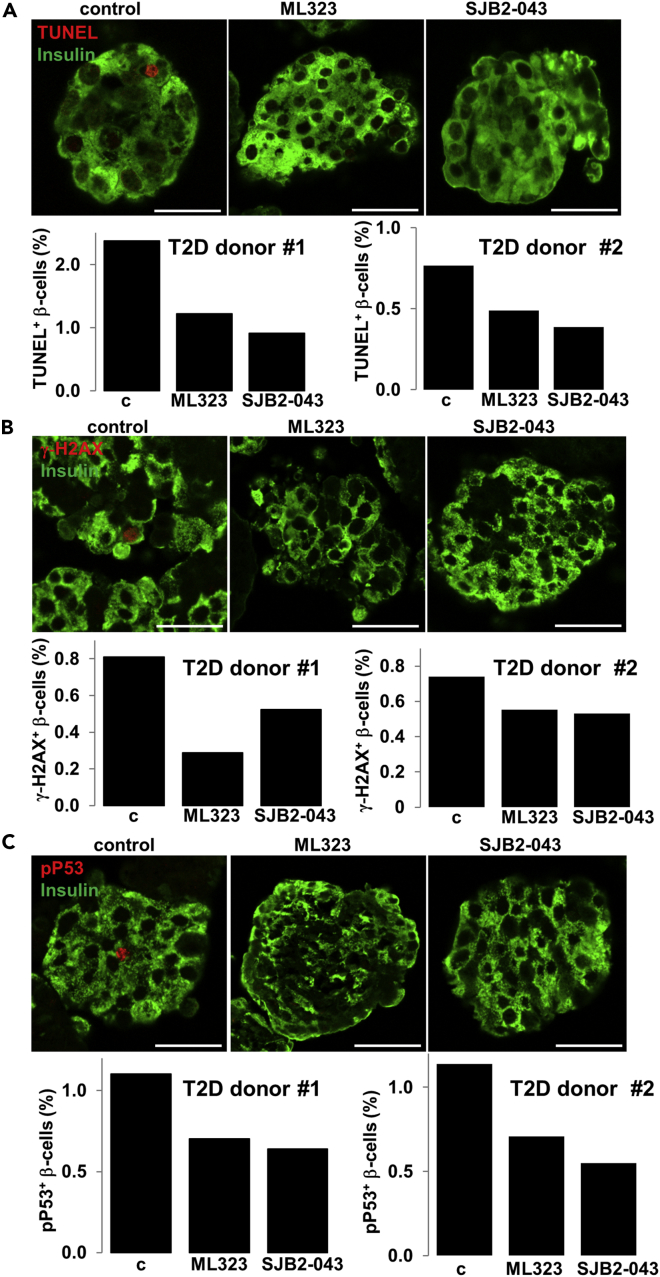

A progressive impairment of β-cell function together with increased β-cell death under diabetic conditions has been clearly documented in human β-cells. To test the potential beneficial effect of USP1 suppression in the human β-cell under conditions of T2D, we performed a proof-of-concept experiment, whereby we inhibited USP1 in two human islet preparations isolated from two patients with T2D. Islets were treated with ML323 and SJB2-043 for 24 hr. Consistent with the improved β-cell survival of human islets under diabetogenic conditions upon USP1 inhibition, isolated T2D islets treated with both USP1 inhibitors showed less apoptotic β-cells, demonstrated in two independent experiments from two different T2D human islet isolations (Figure 7A). In line with our data in INS-1E cells and human islets, both ML323 and SJB2-043 treatment highly reduced the number of γ-H2AX- and p-p53-positive β-cells in human islets consistently in two distinct human T2D islet batches (Figures 7B and 7C). This further confirms the USP1-dependent regulation of DDR under a diabetic environment.

Figure 7.

USP1 Inhibitors Reduced β-Cell Apoptosis and DDR in Human T2D Islets

Isolated human islets from two patients with T2D treated with or without USP1 inhibitors ML323 or SJB2-043 for 1 day. (A–C) Human pancreatic islets were fixed, paraffin embedded, and double stained for the TUNEL assay (A), γ-H2AX (B), or p-p53 (C) and insulin. Representative confocal images and individual quantitative percentage of TUNEL, γ-H2AX, or p-p53 positive β-cells are shown from 2 to 4 technical replica/group from two islet donors with confirmed T2D. Scale bars represent 50 μm. Data are means of TUNEL-, γ-h2AX-, or pp53- and insulin-co-positive β-cells from pooled data of 2–4 different human islet sections spanning the whole islet pellet for each experimental group. About 150–200 islets were plated for each group. The mean number of β-cells scored was 6,050 for each condition for each donor.

Discussion

Loss of insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells results in hyperglycemia and is the hallmark of both T1D and T2D. Identification of key signaling molecules that promote β-cell death in diabetes, together with an understanding of their mechanisms of action, is critical for the disease pathogenesis as well as for novel therapeutic interventions to halt β-cell failure during development and progression of diabetes. This study provides the first direct evidence that genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the enzyme USP1 protects β-cells from apoptosis under diabetogenic stimulation by attenuating DDR signals.

DDR is a signal transduction pathway, which functions together with other networking pathways known as DNA damage checkpoints (Harrison and Haber, 2006), and its dysregulation is a hallmark of several pathological disorders, such as cancer and neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases (Jackson and Bartek, 2009, Shimizu et al., 2014). Elevated DDR has been observed in pancreatic islets/β-cells under increased cellular stress and metabolic demand in vivo or under diabetic conditions in vitro. Surrogate markers of DDR, such as γ-H2AX, p53, and P53BP1, are highly upregulated in primary islets and β-cells in response to oxidative and inflammatory assaults as well as in pancreatic islets from streptozotocin (STZ)-treated diabetic mice, leptin-receptor-deficient dbdb, and human T2D islets (Belgardt et al., 2015, Himpe et al., 2016, Nyblom et al., 2009, Oleson et al., 2014, Oleson et al., 2016, Tornovsky-Babeay et al., 2014), suggesting that oxidative- or metabolic-mediated double-strand breaks in the DNA and downstream activation of p53 may be a key pathogenic element of β-cell stress under metabolic and inflammatory conditions. This is further supported by the elevated incidence of diabetes in individuals who received irradiation to the pancreas (de Vathaire et al., 2012, Meacham et al., 2009). Furthermore, oxidized DNA and p53 signaling are both highly upregulated in human T2D islets (Sakuraba et al., 2002, Tornovsky-Babeay et al., 2014). Initially, the DDR coordinates a transcriptional program with DNA repair and cell cycle arrest (Ciccia and Elledge, 2010); however, under sustained cellular stresses when DNA damage can no longer be repaired, the DDR initiates apoptosis (Roos and Kaina, 2013). DUBs play an important role in DDR. Although multiple numbers of DUBs are involved in DNA repair and the downstream process, USP1 is the first enzyme characterized as the key player in DDR (Jacq et al., 2013). USP1 is the DUB responsible for deubiquitination of monoubiquitinated FANCD2 (Nijman et al., 2005), an integral component of the Fanconi anemia (FA) DNA repair pathway and PCNA (Kee and D'Andrea, 2012). USP1 and its associated partner USP1-associated factor 1 (UAF1) play an important function in promoting DNA homologous recombination (HR) repair in response to DDR via distinct mechanisms: through FANCD2 deubiquitination (Nijman et al., 2005) or by interacting with RAD51 associated protein 1 (RAD51AP1; Cukras et al., 2016). It is possible that the interactions with these known USP1 targets directly lead to the reduced γ-H2AX described in our study. Also, USP1-dependent regulation of other signaling pathways such as AKT (Zhang et al., 2016, Zhiqiang et al., 2012) or upstream elements of the DDR, such as CHK1, a key kinase involved in DDR and DNA repair, which is also stabilized by USP1 (Guervilly et al., 2011), may affect the DDR output together with γ-H2AX formation (Bozulic et al., 2008, Surucu et al., 2008, Xu et al., 2010). Owing to the complexity of DDR signaling and multi-layer actions of USP1, there may also be dual and time-/concentration-/cell-system-dependent effects on γ-H2AX formation or on DDR in general, as an induction of γ-H2AX upon USP1 inhibition has also been observed (Olazabal-Herrero et al., 2016). Our results suggest that the genetic and pharmacological suppression of USP1 in rodent β-cell and human islets protected the cells from DNA-damage-induced cell death with preserving β-cell insulin secretion and β-cell key maturation genes, proposing the critical function of USP1 in the regulation of β-cell apoptosis under different diabetogenic conditions. However, pathway(s) responsible for the regulation of USP1 as well as the molecular mechanism by which USP1 regulates DDR in β-cells, especially in the diabetic environment, remains unknown and warrants further mechanistic investigations.

Although several USP1 targets, such as FANCD2 and PCNA, have been established in the context of DDR, the identification of novel USP1 substrates in other cellular processes will provide further insights on the action of USP1 in regulating cell survival and stress response. Recently, TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), a key regulator of the innate antiviral immunity and maintenance of immune homeostasis, has been discovered as a novel substrate of USP1 (Yu et al., 2017). Yu et al. showed that USP1 functions as an important cellular enhancer of Toll-like receptor 3/4 (TLR3/4)-, retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-, and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-induced antiviral signaling by TBK1 deubiquitination and regulation of its stability (Yu et al., 2017). TBK1 has a pleotropic function in the metabolic process, inflammation, and diabetes. Identified as an inflammatory kinase that targets the insulin receptor (Munoz et al., 2009), TBK1 regulates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes (Uhm et al., 2017). TBK1 levels are upregulated in obesity and diabetes, and the inhibition of TBK1 together with another inflammatory IKK-related kinase IKKɛ by the dual kinase inhibitor amlexanox reduces weight, fatty liver, and inflammation, as well as promotes insulin sensitivity in obese diabetic mice (Reilly et al., 2013) and presents a significant reduction in HbA1c in a subset of patients with T2D (Oral et al., 2017). As diabetogenic conditions, such as elevated palmitic acid, induce β-cell death and dysfunction at least in part through TLR4 signals (Eguchi et al., 2012, Saksida et al., 2012) upstream of TBK1, it is likely that the newly identified USP1-TBK1 axis affects viability, stress response, and inflammation in β-cells as well as in other metabolically active tissues in metabolic and inflammatory contexts. This remains to be investigated.

Conclusion

Impaired β-cell survival is a key pathogenic element of pancreatic β-cell's insufficiency in both T1D and T2D. Here we demonstrated the anti-apoptotic action of USP1 inhibition through the regulation of DDR in several in vitro and ex vivo experimental models of diabetes in stressed β-cells in both rodent and human cells. The identification of the previously uncharacterized function of USP1 in the regulation of β-cell apoptosis may have a potential therapeutic relevance for the preservation of functional β-cell mass in diabetes. To warrant this, identification of β-cell-specific USP1 substrates, detailed mechanistic analyses, as well as the in vivo preclinical assessment of utility, efficacy, and side effects of currently available USP1 inhibitors are required in the near future.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the JDRF, and the EFSD/Lilly Fellowship Programme. Human islets were provided through the integrated islet distribution program (IIDP) supported by NIH and JDRF and the ECIT Islet for Basic Research program supported by JDRF (JDRF award 31-2008-413). We thank J. Kerr-Conte and Francois Pattou (European Genomic Institute for Diabetes, Lille) for high-quality human islet isolations and Katrischa Hennekens (University of Bremen) for the excellent technical assistance.

Author Contributions

Designed and preformed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper, K.G.; assisted to perform experiments, B.L., K.A., T.Y.; designed and supervised project and wrote the paper, A.A., K.M. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 23, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Transparent Methods and two figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2018.02.003.

Contributor Information

Kathrin Maedler, Email: kmaedler@uni-bremen.de.

Amin Ardestani, Email: ardestani.amin@gmail.com.

Supplemental Information

References

- Alejandro E.U., Gregg B., Blandino-Rosano M., Cras-Meneur C., Bernal-Mizrachi E. Natural history of beta-cell adaptation and failure in type 2 diabetes. Mol. Aspects Med. 2015;42:19–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardestani A., Lupse B., Kido Y., Leibowitz G., Maedler K. mTORC1 signaling: a double-edged sword in diabetic beta cells. Cell Metab. 2018;27:314–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardestani A., Maedler K. The Hippo signaling pathway in pancreatic beta-cells: functions and regulations. Endocr. Rev. 2018;39:21–35. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardestani A., Paroni F., Azizi Z., Kaur S., Khobragade V., Yuan T., Frogne T., Tao W., Oberholzer J., Pattou F. MST1 is a key regulator of beta cell apoptosis and dysfunction in diabetes. Nat. Med. 2014;20:385–397. doi: 10.1038/nm.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgardt B.F., Ahmed K., Spranger M., Latreille M., Denzler R., Kondratiuk N., von Meyenn F., Villena F.N., Herrmanns K., Bosco D. The microRNA-200 family regulates pancreatic beta cell survival in type 2 diabetes. Nat. Med. 2015;21:619–627. doi: 10.1038/nm.3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozulic L., Surucu B., Hynx D., Hemmings B.A. PKBalpha/Akt1 acts downstream of DNA-PK in the DNA double-strand break response and promotes survival. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broca C., Varin E., Armanet M., Tourrel-Cuzin C., Bosco D., Dalle S., Wojtusciszyn A. Proteasome dysfunction mediates high glucose-induced apoptosis in rodent beta cells and human islets. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugliani M., Liechti R., Cheon H., Suleiman M., Marselli L., Kirkpatrick C., Filipponi F., Boggi U., Xenarios I., Syed F. Microarray analysis of isolated human islet transcriptome in type 2 diabetes and the role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in pancreatic beta cell dysfunction. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013;367:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A.E., Janson J., Bonner-Weir S., Ritzel R., Rizza R.A., Butler P.C. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:102–110. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatenoud L. Immune therapy for type 1 diabetes mellitus-what is unique about anti-CD3 antibodies? Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2010;6:149–157. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccia A., Elledge S.J. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinti F., Bouchi R., Kim-Muller J.Y., Ohmura Y., Sandoval P.R., Masini M., Marselli L., Suleiman M., Ratner L.E., Marchetti P. Evidence of beta-cell dedifferentiation in human type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;101:1044–1054. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costes S., Gurlo T., Rivera J.F., Butler P.C. UCHL1 deficiency exacerbates human islet amyloid polypeptide toxicity in beta-cells: evidence of interplay between the ubiquitin/proteasome system and autophagy. Autophagy. 2014;10:1004–1014. doi: 10.4161/auto.28478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costes S., Huang C.J., Gurlo T., Daval M., Matveyenko A.V., Rizza R.A., Butler A.E., Butler P.C. beta-cell dysfunctional ERAD/ubiquitin/proteasome system in type 2 diabetes mediated by islet amyloid polypeptide-induced UCH-L1 deficiency. Diabetes. 2011;60:227–238. doi: 10.2337/db10-0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukras S., Lee E., Palumbo E., Benavidez P., Moldovan G.L., Kee Y. The USP1-UAF1 complex interacts with RAD51AP1 to promote homologous recombination repair. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:2636–2646. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1209613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vathaire F., El-Fayech C., Ben Ayed F.F., Haddy N., Guibout C., Winter D., Thomas-Teinturier C., Veres C., Jackson A., Pacquement H. Radiation dose to the pancreas and risk of diabetes mellitus in childhood cancer survivors: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexheimer, T.S., Rosenthal, A.S., Liang, Q., Chen, J., Villamil, M.A., Kerns, E.H., Simeonov, A., Jadhav, A., Zhuang, Z., and Maloney, D.J. (2010). Discovery of ML323 as a Novel Inhibitor of the USP1/UAF1 Deubiquitinase Complex. In Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program (Bethesda (MD)). [PubMed]

- Donath M.Y., Dalmas E., Sauter N.S., Boni-Schnetzler M. Inflammation in obesity and diabetes: islet dysfunction and therapeutic opportunity. Cell Metab. 2013;17:860–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi K., Manabe I., Oishi-Tanaka Y., Ohsugi M., Kono N., Ogata F., Yagi N., Ohto U., Kimoto M., Miyake K. Saturated fatty acid and TLR signaling link beta cell dysfunction and islet inflammation. Cell Metab. 2012;15:518–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frescas D., Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:438–449. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Santisteban I., Peters G.J., Giovannetti E., Rodriguez J.A. USP1 deubiquitinase: cellular functions, regulatory mechanisms and emerging potential as target in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer. 2013;12:91. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorasia D.G., Dudek N.L., Veith P.D., Shankar R., Safavi-Hemami H., Williamson N.A., Reynolds E.C., Hubbard M.J., Purcell A.W. Pancreatic beta cells are highly susceptible to oxidative and ER stresses during the development of diabetes. J. Proteome Res. 2015;14:688–699. doi: 10.1021/pr500643h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grankvist K., Marklund S.L., Taljedal I.B. CuZn-superoxide dismutase, Mn-superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in pancreatic islets and other tissues in the mouse. Biochem. J. 1981;199:393–398. doi: 10.1042/bj1990393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guervilly J.H., Renaud E., Takata M., Rosselli F. USP1 deubiquitinase maintains phosphorylated CHK1 by limiting its DDB1-dependent degradation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:2171–2181. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haataja L., Gurlo T., Huang C.J., Butler P.C. Islet amyloid in type 2 diabetes, and the toxic oligomer hypothesis. Endocr. Rev. 2008;29:303–316. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J.C., Haber J.E. Surviving the breakup: the DNA damage checkpoint. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006;40:209–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.051206.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley T., Brumell J., Volchuk A. Emerging roles for the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy in pancreatic beta-cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;296:E1–E10. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90538.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold K.C., Usmani-Brown S., Ghazi T., Lebastchi J., Beam C.A., Bellin M.D., Ledizet M., Sosenko J.M., Krischer J.P., Palmer J.P. Beta cell death and dysfunction during type 1 diabetes development in at-risk individuals. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:1163–1173. doi: 10.1172/JCI78142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himpe E., Cunha D.A., Song I., Bugliani M., Marchetti P., Cnop M., Bouwens L. Phenylpropenoic acid glucoside from rooibos protects pancreatic beta cells against cell death induced by acute injury. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeister-Brix A., Lenzen S., Baltrusch S. The ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates the stability and activity of the glucose sensor glucokinase in pancreatic beta-cells. Biochem. J. 2013;456:173–184. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.J., Lin C.Y., Haataja L., Gurlo T., Butler A.E., Rizza R.A., Butler P.C. High expression rates of human islet amyloid polypeptide induce endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated beta-cell apoptosis, a characteristic of humans with type 2 but not type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:2016–2027. doi: 10.2337/db07-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S.P., Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacq X., Kemp M., Martin N.M.B., Jackson S.P. Deubiquitylating enzymes and DNA damage response pathways. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2013;67:25–43. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery N., Harries L.W. Beta-cell differentiation status in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016;18:1167–1175. doi: 10.1111/dom.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniuk N.A., Kiraly M., Bates H., Vranic M., Volchuk A., Brumell J.H. Ubiquitinated-protein aggregates form in pancreatic beta-cells during diabetes-induced oxidative stress and are regulated by autophagy. Diabetes. 2007;56:930–939. doi: 10.2337/db06-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee Y., D'Andrea A.D. Molecular pathogenesis and clinical management of Fanconi anemia. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:3799–3806. doi: 10.1172/JCI58321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurrer M.O., Pakala S.V., Hanson H.L., Katz J.D. Beta cell apoptosis in T cell-mediated autoimmune diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:213–218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen S. Oxidative stress: the vulnerable beta-cell. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:343–347. doi: 10.1042/BST0360343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen S., Drinkgern J., Tiedge M. Low antioxidant enzyme gene expression in pancreatic islets compared with various other mouse tissues. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996;20:463–466. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)02051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q., Dexheimer T.S., Zhang P., Rosenthal A.S., Villamil M.A., You C., Zhang Q., Chen J., Ott C.A., Sun H. A selective USP1-UAF1 inhibitor links deubiquitination to DNA damage responses. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:298–304. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwak S.A., Wali J.A., Pappas E.G., Saadi H., Stanley W.J., Varanasi L.C., Kay T.W., Thomas H.E., Gurzov E.N. Lipotoxic stress induces pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis through modulation of Bcl-2 proteins by the Ubiquitin-Proteasome system. J. Diabetes Res. 2015;2015:280615. doi: 10.1155/2015/280615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughery J., Cox M., Smith L.M., Meek D.W. Critical role for p53-serine 15 phosphorylation in stimulating transactivation at p53-responsive promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7666–7680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciani D.S., White S.A., Widenmaier S.B., Saran V.V., Taghizadeh F., Hu X., Allard M.F., Johnson J.D. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL suppress glucose signaling in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2013;62:170–182. doi: 10.2337/db11-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maedler K., Sergeev P., Ris F., Oberholzer J., Joller-Jemelka H.I., Spinas G.A., Kaiser N., Halban P.A., Donath M.Y. Glucose-induced beta-cell production of interleukin-1beta contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:851–860. doi: 10.1172/JCI15318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroqui L., Masini M., Merino B., Grieco F.A., Millard I., Dubois C., Quesada I., Marchetti P., Cnop M., Eizirik D.L. Pancreatic alpha cells are resistant to metabolic stress-induced apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marselli L., Suleiman M., Masini M., Campani D., Bugliani M., Syed F., Martino L., Focosi D., Scatena F., Olimpico F. Are we overestimating the loss of beta cells in type 2 diabetes? Diabetologia. 2014;57:362–365. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini M., Bugliani M., Lupi R., del Guerra S., Boggi U., Filipponi F., Marselli L., Masiello P., Marchetti P. Autophagy in human type 2 diabetes pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1083–1086. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis D., Vence L., Benoist C. beta-Cell death during progression to diabetes. Nature. 2001;414:792–798. doi: 10.1038/414792a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacham L.R., Sklar C.A., Li S., Liu Q., Gimpel N., Yasui Y., Whitton J.A., Stovall M., Robison L.L., Oeffinger K.C. Diabetes mellitus in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Increased risk associated with radiation therapy: a report for the childhood cancer survivor study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009;169:1381–1388. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek D.W. Tumour suppression by p53: a role for the DNA damage response? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:714–723. doi: 10.1038/nrc2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek D.W., Anderson C.W. Posttranslational modification of p53: cooperative integrators of function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009;1:a000950. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier J.J., Bhushan A., Butler A.E., Rizza R.A., Butler P.C. Sustained beta cell apoptosis in patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes: indirect evidence for islet regeneration? Diabetologia. 2005;48:2221–2228. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1949-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry H., Hsieh G., Buhrlage S.J., Huang M., Park E., Cuny G.D., Galinsky I., Stone R.M., Gray N.S., D'Andrea A.D. Small-molecule inhibitors of USP1 target ID1 degradation in leukemic cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2651–2662. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0103-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz M.C., Giani J.F., Mayer M.A., Toblli J.E., Turyn D., Dominici F.P. TANK-binding kinase 1 mediates phosphorylation of insulin receptor at serine residue 994: a potential link between inflammation and insulin resistance. J. Endocrinol. 2009;201:185–197. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman S.M., Huang T.T., Dirac A.M., Brummelkamp T.R., Kerkhoven R.M., D'Andrea A.D., Bernards R. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP1 regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyblom H.K., Bugliani M., Fung E., Boggi U., Zubarev R., Marchetti P., Bergsten P. Apoptotic, regenerative, and immune-related signaling in human islets from type 2 diabetes individuals. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:5650–5656. doi: 10.1021/pr9006816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrunc M., Martinez-Zamudio R.I., Sadoun P.B., Dore G., Schwerer H., Pasero P., Lemaitre J.M., Dejean A., Bischof O. USP1 regulates cellular senescence by controlling genomic integrity. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1401–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olazabal-Herrero A., Garcia-Santisteban I., Rodriguez J.A. Mutations in the 'Fingers' subdomain of the deubiquitinase USP1 modulate its function and activity. FEBS J. 2016;283:929–946. doi: 10.1111/febs.13648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleson B.J., Broniowska K.A., Naatz A., Hogg N., Tarakanova V.L., Corbett J.A. Nitric oxide suppresses beta-cell apoptosis by inhibiting the DNA damage response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016;36:2067–2077. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00262-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleson B.J., Broniowska K.A., Schreiber K.H., Tarakanova V.L., Corbett J.A. Nitric oxide induces ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein-dependent gammaH2AX protein formation in pancreatic beta cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:11454–11464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.531228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral E.A., Reilly S.M., Gomez A.V., Meral R., Butz L., Ajluni N., Chenevert T.L., Korytnaya E., Neidert A.H., Hench R. Inhibition of IKKvarepsilon and TBK1 improves glucose control in a subset of patients with type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2017;26:157–170.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poitout V., Robertson R.P. Glucolipotoxicity: fuel excess and beta-cell dysfunction. Endocr. Rev. 2008;29:351–366. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo S.E., Jackson S.P. Dynamics of DNA damage response proteins at DNA breaks: a focus on protein modifications. Genes Dev. 2011;25:409–433. doi: 10.1101/gad.2021311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahier J., Guiot Y., Goebbels R.M., Sempoux C., Henquin J.C. Pancreatic beta-cell mass in European subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2008;10(Suppl 4):32–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S.M., Chiang S.H., Decker S.J., Chang L., Uhm M., Larsen M.J., Rubin J.R., Mowers J., White N.M., Hochberg I. An inhibitor of the protein kinases TBK1 and IKK-varepsilon improves obesity-related metabolic dysfunctions in mice. Nat. Med. 2013;19:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nm.3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt H.C., Schumacher B. The p53 network: cellular and systemic DNA damage responses in aging and cancer. Trends Genet. 2012;28:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes C.J. Type 2 diabetes-a matter of beta-cell life and death? Science. 2005;307:380–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1104345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzel R.A., Butler A.E., Rizza R.A., Veldhuis J.D., Butler P.C. Relationship between beta-cell mass and fasting blood glucose concentration in humans. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:717–718. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R.P., Harmon J., Tran P.O., Poitout V. Beta-cell glucose toxicity, lipotoxicity, and chronic oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 1):S119–S124. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos W.P., Kaina B. DNA damage-induced cell death: from specific DNA lesions to the DNA damage response and apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksida T., Stosic-Grujicic S., Timotijevic G., Sandler S., Stojanovic I. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor deficiency protects pancreatic islets from palmitic acid-induced apoptosis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012;90:688–698. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuraba H., Mizukami H., Yagihashi N., Wada R., Hanyu C., Yagihashi S. Reduced beta-cell mass and expression of oxidative stress-related DNA damage in the islet of Japanese Type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2002;45:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s125-002-8248-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M., Finley D. Regulation of proteasome activity in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1843:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu I., Yoshida Y., Suda M., Minamino T. DNA damage response and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2014;20:967–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourisseau T., Helissey C., Lefebvre C., Ponsonnailles F., Malka-Mahieu H., Olaussen K.A., Andre F., Vagner S., Soria J.C. Translational regulation of the mRNA encoding the ubiquitin peptidase USP1 involved in the DNA damage response as a determinant of Cisplatin resistance. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:295–302. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1120918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surucu B., Bozulic L., Hynx D., Parcellier A., Hemmings B.A. In vivo analysis of protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt regulation in DNA-PKcs-null mice reveals a role for PKB/Akt in DNA damage response and tumorigenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:30025–30033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803053200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talchai C., Xuan S., Lin H.V., Sussel L., Accili D. Pancreatic beta cell dedifferentiation as a mechanism of diabetic beta cell failure. Cell. 2012;150:1223–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedge M., Lortz S., Drinkgern J., Lenzen S. Relation between antioxidant enzyme gene expression and antioxidative defense status of insulin-producing cells. Diabetes. 1997;46:1733–1742. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S., Roel C., Tanwir M., Wills R., Perianayagam N., Wang P., Fiaschi-Taesch N.M. Definition of a Skp2-c-Myc pathway to expand human beta-cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28461. doi: 10.1038/srep28461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita T. Immunocytochemical localisation of caspase-3 in pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic subjects. Pathology. 2010;42:432–437. doi: 10.3109/00313025.2010.493863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornovsky-Babeay S., Dadon D., Ziv O., Tzipilevich E., Kadosh T., Schyr-Ben Haroush R., Hija A., Stolovich-Rain M., Furth-Lavi J., Granot Z. Type 2 diabetes and congenital hyperinsulinism cause DNA double-strand breaks and p53 activity in beta cells. Cell Metab. 2014;19:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhm M., Bazuine M., Zhao P., Chiang S.H., Xiong T., Karunanithi S., Chang L., Saltiel A.R. Phosphorylation of the exocyst protein Exo84 by TBK1 promotes insulin-stimulated GLUT4 trafficking. Sci. Signal. 2017;10 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aah5085. eaah5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetere A., Choudhary A., Burns S.M., Wagner B.K. Targeting the pancreatic beta-cell to treat diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:278–289. doi: 10.1038/nrd4231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N., Hegarat N., Black E.J., Scott M.T., Hochegger H., Gillespie D.A. Akt/PKB suppresses DNA damage processing and checkpoint activation in late G2. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:297–305. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Song H., Jia M., Zhang J., Wang W., Li Q., Zhang L., Zhao W. USP1-UAF1 deubiquitinase complex stabilizes TBK1 and enhances antiviral responses. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:3553–3563. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J., Adamski R., Chen J. Focus on histone variant H2AX: to be or not to be. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3717–3724. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan T., Gorrepati K.D., Maedler K., Ardestani A. Loss of Merlin/NF2 protects pancreatic beta-cells from apoptosis by inhibiting LATS2. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2107. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan T., Rafizadeh S., Azizi Z., Lupse B., Gorrepati K.D., Awal S., Oberholzer J., Maedler K., Ardestani A. Proproliferative and antiapoptotic action of exogenously introduced YAP in pancreatic beta cells. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e86326. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan T., Rafizadeh S., Gorrepati K.D., Lupse B., Oberholzer J., Maedler K., Ardestani A. Reciprocal regulation of mTOR complexes in pancreatic islets from humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2017;60:668–678. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Lu X., Akhter S., Georgescu M.M., Legerski R.J. FANCI is a negative regulator of Akt activation. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:1134–1143. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1158375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Q., Huang T., Zhang L., Zhou Y., Luo H., Xu H., Wang X. Dysregulation of ubiquitin-proteasome system in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:303. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhiqiang Z., Qinghui Y., Yongqiang Z., Jian Z., Xin Z., Haiying M., Yuepeng G. USP1 regulates AKT phosphorylation by modulating the stability of PHLPP1 in lung cancer cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2012;138:1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1193-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.