Key Points

Question

Do patients with CNGB1-associated retinitis pigmentosa have a reduced sense of smell and a characteristic presentation of retinal disease?

Findings

In this case series of 9 patients, early retinal dysfunction was characterized by a slowly progressive rod-cone dystrophy. In all but 1 patient, olfactory function was reduced or absent.

Meaning

These findings suggest that mutations in CNGB1 may cause syndromic retinitis pigmentosa of moderate severity and olfactory dysfunction.

Abstract

Importance

Co-occurrence of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and olfactory dysfunction may have a common genetic cause.

Objective

To report olfactory function and the retinal phenotype in patients with biallelic mutations in CNGB1, a gene coding for a signal transduction channel subunit expressed in rod photoreceptors and olfactory sensory neurons.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This case series was conducted from August 2015 through July 2017. The setting was a multicenter study involving 4 tertiary referral centers for inherited retinal dystrophies. Participants were 9 patients with CNGB1-associated RP.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Results of olfactory testing, ocular phenotyping, and molecular genetic testing using targeted next-generation sequencing.

Results

Nine patients were included in the study, 3 of whom were female. Their ages ranged between 34 and 79 years. All patients had an early onset of night blindness but were usually not diagnosed as having RP before the fourth decade because of slow retinal degeneration. Retinal features were characteristic of a rod-cone dystrophy. Olfactory testing revealed reduced or absent olfactory function, with all except one patient scoring in the lowest quartile in relation to age-related norms. Brain magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography measurements in response to olfactory stimulation were available for 1 patient and revealed no visible olfactory bulbs and reduced responses to odor, respectively. Molecular genetic testing identified 5 novel (c.1312C>T, c.2210G>A, c.2492+1G>A, c.2763C>G, and c.3044_3050delGGAAATC) and 5 previously reported mutations in CNGB1.

Conclusions and Relevance

Mutations in CNGB1 may cause an autosomal recessive RP–olfactory dysfunction syndrome characterized by a slow progression of retinal degeneration and variable anosmia or hyposmia.

This case series reports olfactory function and the retinal phenotype in patients with biallelic mutations in CNGB1, a gene coding for a signal transduction channel subunit expressed in rod photoreceptors and olfactory sensory neurons.

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (OMIM 268000) is a genetically heterogeneous disease characterized by poor night vision and loss of peripheral visual field owing to a decline in rod-dependent vision. Later in the disease course, cones and thus the central visual field and visual acuity may also be affected. Retinitis pigmentosa is caused by mutations in genes coding for proteins involved in photoreceptor function, structure, and/or maintenance. When the gene product is expressed exclusively in the retina or when its lack is compensated for in other tissues, the disease remains restricted to the retina. However, significant expression of the gene product in other organs may result in syndromic RP with morphological and/or functional consequences affecting other organs.

Cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels are key components for signal transduction in photoreceptors and olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs).1 They function as tetramers composed of α and β subunits. Specific types of heterotetramers are expressed in different sensory cells. For example, the rod CNG channel consists of 3 CNGA1 subunits and 1 CNGB1 subunit,2 the cone CNG channel consists of 3 CNGA3 subunits and 1 CNGB3 subunit,3,4 and the CNG channel of OSNs (olfCNG) consists of 2 CNGA2 subunits, 1 CNGA4 subunit, and 1 CNGB1b subunit.5

Therefore, only the CNGB1 subunit is involved in both photoreceptor and olfactory signal transduction. In contrast to most CNGA subunits that are regarded as main subunits (except for CNGA4), CNGB1 does not form functional homomeric channels on its own if heterologously expressed but modulates, when coexpressed with a main subunit, the biophysical properties (eg, ligand sensitivity) of the heteromeric channel. This is essential for retinal rod phototransduction and results in optimization of the odor-induced signal transduction and feedback inhibition in olfactory neurons.6 In accord with these findings, Cngb1 knockout mice develop retinal degeneration and have reduced olfactory function.7,8

Despite the dual function of CNGB1 in rods and OSNs, CNGB1 mutations in humans have hitherto only been associated with autosomal recessive RP (OMIM 600724; OMIM 613767),9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 and, to our knowledge, an association with olfactory dysfunction has not been reported previously. In humans, only mutations in CNGA2 (OMIM 300338) have recently been associated with isolated congenital anosmia in 2 siblings.28,29 We hypothesized that patients with CNGB1-associated RP might also have an impaired sense of smell and tested their olfactory function, which revealed that CNGB1 mutations can also cause syndromic RP with olfactory impairment.

Methods

This case series was conducted from August 2015 through July 2017. Patients were identified from the databases of the following 4 tertiary referral centers for inherited retinal dystrophies: Centre for Ophthalmology at the University of Tübingen, Tübingen Germany (patients 1, 2, 7, and 8); Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany (patients 4 and 5); Oxford Eye Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom (patients 3 and 6); and Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan (patient 9). The study was conducted in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki.30 Institutional review board approval and patient written informed consent were obtained. Patient 8 had hearing impairment since childhood. None of the other patients had any additional functional defects or a medical history suggestive of a syndromic retinal disease.

All patients underwent a complete ophthalmologic examination, including best-corrected visual acuity, slitlamp, and indirect ophthalmoscopy with dilated pupils. All patients underwent fundus autofluorescence (AF) and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) retinal imaging with combined confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and SD-OCT (Spectralis HRA-OCT; Heidelberg Engineering). Color images were recorded in most patients using different fundus cameras depending on local protocols. In 2 patients (patients 3 and 6), pseudocolor images were acquired using a widefield scanning laser ophthalmoscope (Optomap; Optos). Electroretinography in accord with the standards of the International Society of Electrophysiology of Vision and visual field testing were performed with different devices and protocols depending on the availability and local protocols at the 4 centers.

Olfactory testing was performed using the Sniffin’ Sticks (Burghart Messtechnik)31 test battery consisting of tests for odor threshold, odor discrimination, and odor identification or the T&T olfactometer (Daiichi Yakuhin Sangyo),32 which is based on the combined evaluation of odor thresholds and odor identification. Both tests allow the classification of results in terms of anosmia, hyposmia, and normosmia.33 Electroencephalography measurements in response to olfactory stimulation were obtained with an olfactometer (OM6bl; Burghart Messtechnik), with a total flow of 6.4 L/min, stimulus duration of 200 milliseconds, 40 stimuli per quality, and interstimulus interval of approximately 20 seconds.34 Time-frequency analyses were performed as described previously with a 16-channel amplifier (s.i.r. Schabert Instruments), with reference linked earlobes A1 to A2, sampling frequency of 250 Hz, and bandpass filter of 0.2 to 30 Hz.35,36 Diseases that may cause olfactory impairment, such as chronic rhinosinusitis, were excluded based on an extensive history and clinical examination, including nasal endoscopy.

The genetic diagnosis was ascertained in a diagnostic genetic setup by targeted next-generation sequencing as reported previously.22,37,38,39 Nomenclature is based on the GenBank reference NM_001297.4 and Human Genome Variation Society recommendations for describing the genotypes in a recessive disease. Nonsynonymous amino acid substitution (missense) and splice-site variants were evaluated for evolutionary conservation (accessed through the National Center for Biotechnology Information), minor allele frequency in a healthy population (ie, gnomAD browser), by various prediction programs (ie, PolyPhen-2, SIFT, Mutationtaster, and Human Splice Finder), and the recommendations of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Segregation analysis was performed by Sanger sequencing for available family members.

Results

Retinal Phenotype

Nine patients were included in the study, 3 of whom were female. Ages ranged between 34 and 79 years. All patients reported lifelong night blindness. However, the clinical diagnosis of RP was established in the fourth decade or later in 6 of the 9 patients (Table 1), indicating a relatively benign disease course.

Table 1. Genetic Findings and Clinical Features of 9 Patients With Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) With Mutations in CNGB1.

| Patient No./Sex/Age, y | CNGB1 Mutation Sequence | RP Retinal Phenotype | Olfactory Phenotype/Function | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis, y | BCVA | Approximate Preserved Central Visual Field | Full-Field ERG | Refraction (Sphere/Cylinder)a | Additional Comments | Test Result Score | Classification in Relation to Healthy Controlsb | |||||

| OD | OS | Scotopic Responses | Photopic Responses | OD | OS | |||||||

| 1/M/43 | c.[2210G>A(;)2763C>G] | 39 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 30° | Rod-specific undetectable, small mixed responses | Approximately 70% below lower normal limits | +0.25/−0.75 | −0.75/−0.75 | NA | TDI 27.5 | Hyposmia |

| 2/M/49 | c.[2957A>T(;)3044_3050del] | 42 | 20/40 | 20/32 | 20° | Undetectable | Undetectable | −4.0 /−0.75 | −3.75/−0.5 | NA | TDI 31.5 | Normosmia (borderline low) |

| 3/F/34 | c.[2492+1G>A];[(2492+1G>A)] | 30 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 25° | Undetectable | Small delayed b wave | −1.0/−0.5 | −0.75/−0.75 | NA | TDI 14.5 | Anosmia |

| 4/M/49c | c.[2284C>T];[2492+1G>A] | 49 | 20/20 | 20/20 | NP | Undetectable | Small delayed b wave | −3.25/−1.5 | −2.75/−0.75 | NA | TDI 25.5 | Hyposmia |

| 5/F/52c | c.[2284C>T];[2492+1G>A] | 30 | 20/25 | 20/20 | 10° | Undetectable | Undetectable | +1.25/−0.25 | +1.0/−0.50 | NA | TDI 26.25 | Hyposmia |

| 6/M/68 | c.[2284C>T];[(2284C>T)] | 45 | 20/40 | 20/32 | NP | NP | NP | +1.0/−1.5 | +0.5/−1.5 | Right eye pseudophakic | TDI 16.5 | Anosmia |

| 7/M/60 | c.[413-1G>A(;)3139_3142dup] | 25 | LP | LP | NP | Undetectable | Undetectable | −0.50/0 | −0.5/−0.5 | Able to read until age 55 y | TDI 20.5 | Hyposmia |

| 8/F/67 | c.[1312C>T];[(1312C>T)] | 8 | LP | NLPd | 2° | Undetectable | Undetectable | Approximately −10.0e | NP | Right eye pseudophakic, left eye phthisis bulbi,d both eyes glaucoma, high myopia | TDI 30.25 | Hyposmia (borderline high) |

| 9/M/79 | c.[2542_2543insA];[(2542_2543insA)] | Childhood | 20/400 | 20/25 | 10° | Undetectable | Undetectable | −0.5/0 | −0.75/−1.5 | Both eyes pseudophakic | T&T olfactometer 5.8f | Anosmia |

Abbreviations: BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; ERG, electroretinography; LP, light perception; NA, not applicable; NLP, no light perception; NP, not performed; TDI, threshold for butanol, discrimination, and identification of odorants, assessed using the Sniffin’ Sticks (Burghart Messtechnik) test (1 to 16.5 indicates functional anosmia, >16.5 to 30.5 indicates hyposmia, and >30.5 indicates normosmia).

For pseudophakic patients, refraction before cataract surgery is given.

Age range, 16 to 35 years.

Patients 4 and 5 are brother and sister.

Phthisis bulbi with retinal detachment after glaucoma surgery.

Cataract surgery was performed before the patient's first visit and therefore, exact refraction before surgery is not known.

Testing with the T&T olfactometer (Daiichi Yakuhin Sangyo) produces a combined test score from threshold testing and odor identification for 5 odors each.

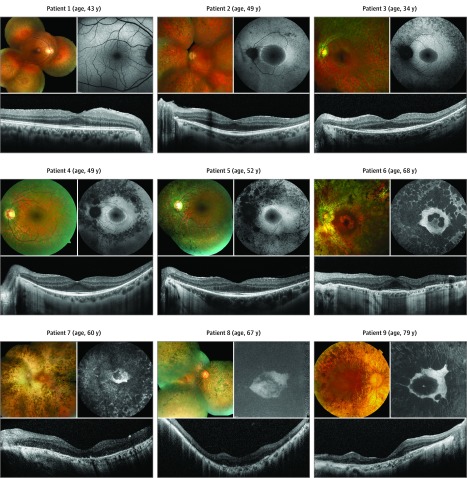

Ophthalmoscopy, AF, and SD-OCT imaging showed changes typical for RP in different stages across patients (Figure 1). This included intraretinal bone spicule pigmentation, narrowed retinal vessels, and pale optic discs on ophthalmoscopy. Fundus AF imaging revealed a paracentral ring of increased AF in patients 2 through 5, and SD-OCT imaging showed a loss or marked reduction of the photoreceptor layer eccentric to this ring. In the older patients 6 through 9, all 60 years or older, variable perifoveal atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptor layer was highlighted on AF and SD-OCT imaging. Patient 1, with the mildest disease manifestation, had only peripheral retinal atrophy and pigmentation but no central fundus involvement.

Figure 1. Retinal Phenotype in Patients With CNGB1-Associated Retinitis Pigmentosa.

For each patient, fundus color (upper left), fundus autofluorescence (upper right), and optical coherence tomography (bottom) images of one eye are shown. The order of patients reflects increasing disease severity on fundus autofluorescence and optical coherence tomography imaging.

Retinawide functional testing using full-field electroretinography was performed in all patients except for one (patient 6). Rod-specific responses were not detectable in any of the tested patients. Residual cone-derived responses were recordable to a variable extent in 3 of the youngest patients (Table 1).

Additional ocular disease included severe glaucoma and high myopia in 1 patient (patient 8), likely explaining her extremely poor vision. Three patients were already pseudophakic in at least one eye (Table 1).

Overall, increasing disease severity occurred with increasing age. However, only relatively mild disease was noted in patient 1. By contrast, more advanced disease was noted at an earlier age in patient 7.

Olfactory Phenotype

Six of the 9 patients were not aware of any reduced olfactory function. One patient (patient 9) reported an absent sense of smell ever since he could remember. Two patients (patients 4 and 5) reported the ability to smell only strong odors since their early childhood. This reduced olfactory function in the 3 patients who were aware of it had never been considered in conjunction with their retinal disease.

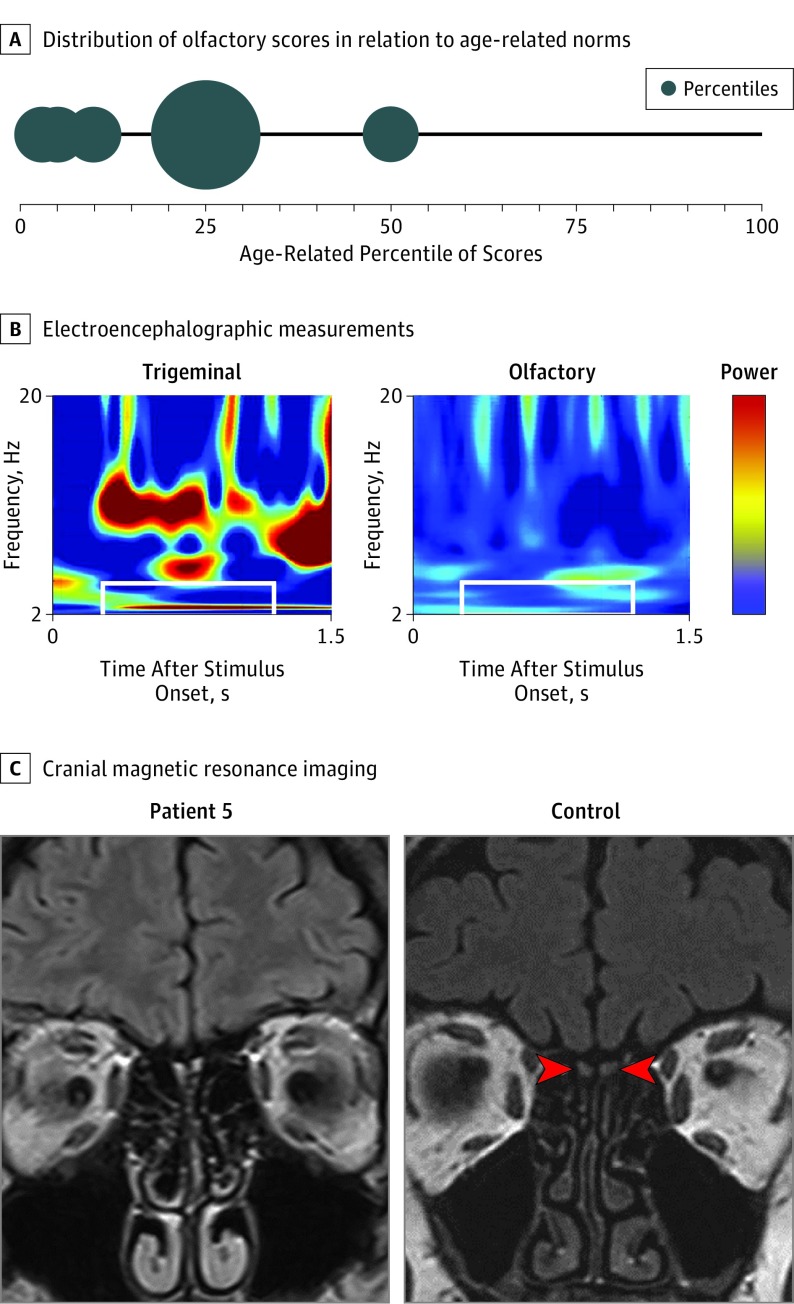

Olfactory testing using Sniffin’ Sticks was performed in 8 of the 9 patients. When related to absolute norms of a group aged between 16 and 35 years,33 anosmia was diagnosed in 2 patients, hyposmia was diagnosed in 5 patients, and normosmia (borderline low) was diagnosed in 1 patient (Table 1). When estimated according to age-related norms,33 7 of 8 patients scored at the 25th percentile or lower, and only 1 patient scored at the 50th percentile (Figure 2A), indicating overall low olfactory sensitivity. In addition, patient 9, who had been tested with the T&T olfactometer, scored in the anosmic range.32,40

Figure 2. Olfactory Phenotype in Patients With CNGB1-Associated Retinitis Pigmentosa.

A, Larger bubbles indicate more patients scoring at this range. All except 1 patient are in the lowest quartile, indicating reduced or absent olfactory function. B, Electroencephalographic measurements in response to trigeminal and olfactory stimulation. Shown is the time-frequency spectrum of event-related potentials obtained from patient 5 in response to trigeminal stimulation with carbon dioxide (60% vol/vol) or olfactory stimulation with rose-like odor phenylethyl alcohol (40% vol/vol). Power is color coded, with blue indicating low power and red indicating high power. The area of interest is marked with white rectangles. While clear activation is seen for trigeminal stimulation, there is little or no activation after olfactory stimulation. C, On the left is a magnetic resonance imaging scan in patient 5 (age, 52 years); the olfactory bulbs are not visible, indicating reduced or absent olfactory function. On the right is a scan in a 55-year-old normosmic individual; red arrowheads point to the left and right olfactory bulbs.

The following details are provided for patient 5, in whom analysis of olfactory function included electro-olfactography: the 52-year-old woman had been known to be night-blind since she was 2 years old. However, she only had noticed visual field defects when she reached age 30 years, at which time she was diagnosed as having RP. The patient knew that her sense of smell was subnormal (ie, certain odors were below her detection threshold). For example, she perceived body odor only when someone sweated extensively and smelled food only when it was spoiled or when the smell was intense (eg, fresh bakery smells). The patient also mentioned that odors were never connected with memories. Her retinal phenotype showed typical bone spicule pigmentation, attenuated retinal vessels, and pale waxy discs. The central island was well preserved for a patient with RP at her age; in keeping with this, the central visual field was constricted to approximately 10°. Olfactory testing revealed hyposmia, as indicated by means of psychophysical and (available only for this patient) electrophysiological measurements (Table 1 and Figure 2B). The patient provided a cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan that had been previously recorded for another indication. The olfactory bulbs were not visible, indicating lack of olfactory tissue (Figure 2C).

Mutational Analysis

We identified 10 different variants in CNGB1 that were likely to explain the disease phenotype in 9 patients from 8 independent families (Table 2). Five variants are novel, and 5 variants have been previously described.15,16,22,27 Three variants are nonsynonymous amino acid substitution (missense) variants. The variants c.2210G>A;p.R737H and c.2284C>T;p.R762C affect highly conserved residues, while c.2957A>T;p.N986I affects a residue only conserved in mammals and birds. However, all 3 are predicted as disease causing by the prediction programs used (Table 2). Seven variants most likely represent protein-truncating mutation types (2 nonsense, 3 indels, and 2 variants affecting the canonical splice site and expected to result in missplicing). The splice-site variants affect the canonical splice sites and are predicted to result in loss of these. Compound heterozygosity could be confirmed by family segregation analysis only in the siblings (patients 4 and 5) because of lack of samples from family members for the other patients. However, 4 patients (patients 3, 6, 8, and 9) were apparently homozygous for their disease-causing variant, indicating that the identified mutation is present either on both alleles or in combination with a large deletion. Therefore, confirmation for biallelic CNGB1 mutations (ie, that the 2 identified heterozygous mutations are in trans) is only lacking for 3 patients (patients 1, 2, and 7).

Table 2. Disease-Causing Variants in CNGB1 and Classification in This Study.

| Variant on Nucleotide Level | Consequence/Variant on Protein Level | Location in CNGB1 Polypeptide | gnomAD Browser MAF, %a | Conservation Among Different Speciesb | Predictionc | ACMG Scoring | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.413-1G>A | Splice defect | N-terminal GARP | 0.008 | NA | Human Splice Finder and MaxEntScan: broken wild-type acceptor site, new acceptor site | Pathogenic (Class Ic) | Azam et al,15 2011 |

| c.1312C>T | p.Q438* | N-terminal GARP | NA | NA | Mutationtaster: disease causing | Pathogenic (Class Ib) | Present study |

| c.2210G>A | p.R737H | TD3 | 0.002 | HsCNGB1 R, MmCNGB1 R, DrCngb1 R | PolyPhen-2: probably damaging (score 0.999), SIFT: damaging (score 0.4), Mutationtaster: disease causing | VUS | Present study |

| c.2284C>T | p.R762C | TD4 | 0.001 | HsCNGB1 R, MmCNGB1 R, DrCngb1 R | PolyPhen-2: probably damaging (score 1.000), SIFT: damaging (score 0), Mutationtaster: disease causing | VUS | Azam et al,15 2011 |

| c.2492+1G>A | Splice defect | Pore | NA | NA | Human Splice Finder and MaxEntScan: broken wild-type donor site | Pathogenic (Class Ib) | Present study |

| c.2542_2543insA | p.G848Efs*4 | Linker pore–TD6 | NA | NA | Mutationtaster: disease causing | Pathogenic (Class Ib) | Oishi et al,22 2014 |

| c.2763C>G | p.Y921* | C-linker | NA | NA | Mutationtaster: disease causing | Pathogenic (Class Ib) | Present study |

| c.2957A>T | p.N986I | CNBD | 0.123 | HsCNGB1 N, MmCNGB1 N, DrCngb1 G | PolyPhen-2: probably damaging (score 0.983), SIFT: damaging (score 0), Mutationtaster: disease causing | VUS | Simpson et al,16 2011 |

| c.3044_3050delGGAAATC | p.G1015Vfs*4 | CNBD | NA | NA | Mutation taster: disease causing | Pathogenic (Class Ib) | Present study |

| c.3139_3142dupGTGG | p.A1048Gfs*13 | CNBD | NA | NA | Mutation taster: disease causing | Pathogenic (Class Ib) | Hull et al,27 2017 |

Abbreviations: ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; CNBD, cyclic nucleotide–binding domain; Dr, Danio rerio; GARP, glutamic acid–rich protein; Hs, Homo sapiens; MAF, minor allele frequency; Mm, Mus musculus; TD, transmembrane domain; NA, not applicable; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/).

Amino acid residue affected by mutation is given in 1-letter code.

PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/), and Mutationtaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/) for prediction for missense variants and Human Splice Finder (http://www.umd.be/HSF3/) and MaxEntScan (http://genes.mit.edu/burgelab/maxent/Xmaxentscan_scoreseq.html) for prediction of splice-site variants.

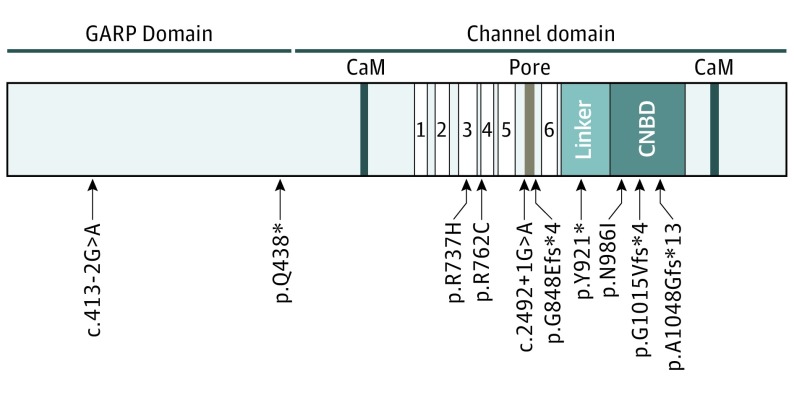

All variants were classified according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines,41 evaluating all nonsense, indel, and canonical splice variants as pathogenic and evaluating the 3 missense variants as variants of uncertain significance (Table 2). Most variants are located within the channel domain of CNGB1 affecting highly conserved amino acid residues, and 2 variants are located in the glutamic acid–rich protein (GARP) domain (Table 2 and Figure 3). No other potentially disease-causing variants were identified in other genes known to be associated with RP.

Figure 3. Structure of the CNGB1 Protein and Location of the Identified Mutations.

The CNGB1 protein consists of an N-terminal glutamic acid–rich protein (GARP) domain and the channel domain with 2 calmodulin-binding sites (CaM), 6 transmembrane domains (TD1-6), a pore region between TD5 and TD6, and a binding site for the cyclic nucleotide–binding domain (CNBD) that is connected via the C-linker to TD6.

Discussion

Our ability to sense light, odor, and sound relies on specialized neuronal cells that have evolved to transduce physical or chemical stimuli into neuronal activation. To fulfill these requirements, specific subcellular structures and cell physiological processes have developed that in part are shared between photoreceptors, OSNs, and hair cells of the inner ear. Consequently, dysfunction of such common cellular characteristics may lead to syndromic disease affecting multiple senses.

Syndromic manifestations of retinal degeneration and olfactory dysfunction have been reported occasionally in CEP290-associated Leber congenital amaurosis42 and in syndromic RP (Bardet-Biedl syndrome,43,44,45,46 Usher syndrome,47 and Refsum syndrome48,49,50). The present case series adds another example to this group of rare syndromic retinal-olfactory diseases: mutations of CNGB1 can cause olfactory dysfunction in conjunction with RP. While similar retinal phenotypic data have been reported previously,27 the key novel findings of the present study are the impaired olfactory function in patients with CNGB1-associated RP.

Nyctalopia, the hallmark symptom of RP, was first noticed among all patients described herein in early childhood. Night blindness, even in the absence of marked structural changes owing to photoreceptor degeneration, would be expected because rod photoreceptor transduction largely depends on functional CNGB1. Although historic and/or long-term observations of the patients were not available, the comparatively late diagnosis, the reasonably well-preserved visual acuities, and the size of the area with spared central retinal structure in patients up to the fifth decade of life suggest a relatively benign disease course compared with many other molecular causes of RP. Overall, the retinal phenotype of the cases reported herein confirms recently reported findings.27,51 The 4 nullizygous patients in our cohort (patients 3, 7, 8, and 9) seem to have a more severe retinal phenotype compared with other reported patients of similar age with possibly less severe mutations (eg, patient 3 has a comparable disease presentation as patients 2, 4, and 5 but is at least 15 years younger). However, the overall number of cases yet reported is too small to draw definite conclusions with regard to a clear correlation between the type of mutation (complete loss of function or missense mutation) and disease severity in CNGB1-associated RP.27 Larger patient cohorts and functional characterization of individual mutations would be necessary to explore this further, as well as consideration of individual mutational effects and gene-gene or environmental effects. Of note, the severely reduced visual function in patient 8 likely owes to the additional copathology (glaucoma).

In most of our patients, only moderate effects of CNGB1 mutations on olfactory function were detected. This correlates with the observations from Cngb1 knockout mice, which show reduced but incomplete loss of olfactory function in behavioral and electrophysiological testing.8 A loss of function because of a frameshift mutation in Cngb1 also results in retinal degeneration in a naturally occurring dog model,51,52,53 but its olfactory function has not yet been reported. In olfactory CNG channels, a modifying role has been attributed to CNGB1, and the channels retain limited functionality when composed of only the CNGA2 and CNGA4 subunits. In the Cngb1 knockout mouse, formation of olfactory CNG channels lacking the CNGB1 subunit results in complex changes at the cellular level, including altered response kinetics with delayed onset and slow recovery, as well as reduced sensitivity to the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate. The olfactory phenotype of patients with CNGB1 mutations is in line with the observations from the Cngb1 knockout mouse, although the variability seems higher in humans, with an olfactory function ranging from normal in the lower range to anosmia. Such variability may be because of mutation site, more variable genetic backgrounds compared with well-controlled animal experiments, or interspecies differences. Furthermore, variability in CNGB1-associated olfactory dysfunction might also be caused by the complex structure of the CNGB1 gene, which contains exons encoding the channel protein and exons encoding for GARPs, giving rise to several different transcripts.54,55,56,57,58,59 The GARP proteins are mainly known for their function in rod photoreceptors, where they coordinate the localization of rod CNG channels in the outer segment via interaction with peripherin 2 (PRPH2),60,61 serve as an inhibitor for channel gating,62 and inhibit phosphodiesterase activity in rods.60 If the GARP proteins only have a role in rods but not in OSNs, one would expect that mutations in the GARP domain, as present in patients 7 and 8, would have no effect on olfactory function. Both patients have mild olfactory dysfunction; however, owing to the small sample size, this question remains unanswered. Alternatively, GARPs might have an as yet unknown function in OSNs, or there might be redundant signaling pathways in OSNs, resulting in different effects of monoallelic mutations in the CNGB1 channel domain.

While CNGB1 mutations undoubtedly result in photoreceptor degeneration, the consequences on OSNs are less clear. An apparently stable olfactory dysfunction may result from the ability of OSNs to regenerate, preventing cumulative damage, or from the inability of patients to identify subtle changes in olfactory dysfunction in relatively homogeneous odor landscapes. In this regard, it should be noted that stable olfactory dysfunction was assumed in this study based on self-reported patient history, which may be unreliable. Whether the nonvisible olfactory bulbs in 1 patient (patient 5) indicate hypoplasia or degeneration, both resulting in reduced olfactory function, remains unknown. The MRI scan was performed for an independent indication using settings not ideal for identifying olfactory bulbs. Future investigations may choose a more appropriate, targeted MRI assessment, and longitudinal imaging and olfactory testing may be needed for reliable interpretation.

The syndromic sensory disease observed in our cohort was not detected or reported in previous studies that included patients with CNGB1-associated RP. An explanation might be the preponderance of mild olfactory dysfunction, with most patients not being aware of their condition. Two research groups specifically reported a normal sense of smell, however, solely based on the patient’s history.13,26 A simple explanation would be that these patients were unaware of their mild olfactory dysfunction. Considering that up to 80% of patients with hyposmia are unaware of their condition,63 it can be easily overlooked unless patients are specifically asked and formally tested for their olfactory ability. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that more subtle qualities of olfactory function may be affected, such as adaptation, that might depend substantially on individual awareness.

Limitations

In summary, the number of patients is too small to draw definite conclusions on effects of individual mutations, and we cannot determine whether or not olfactory neurons degenerate due to the lack of longitudinal observations.

Conclusions

This case series indicates that mutations in CNGB1 can result in an autosomal recessive RP–olfactory dysfunction syndrome. Olfactory dysfunction may inform on the underlying molecular etiology in patients with RP. In reverse, the identification of this syndromic association may support CNGB1 mutations as truly disease causing in these individuals.

References

- 1.Kaupp UB, Seifert R. Cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(3):769-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng J, Trudeau MC, Zagotta WN. Rod cyclic nucleotide-gated channels have a stoichiometry of three CNGA1 subunits and one CNGB1 subunit. Neuron. 2002;36(5):891-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding XQ, Matveev A, Singh A, Komori N, Matsumoto H. Biochemical characterization of cone cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channel using the infrared fluorescence detection system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;723:769-775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shuart NG, Haitin Y, Camp SS, Black KD, Zagotta WN. Molecular mechanism for 3:1 subunit stoichiometry of rod cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Nat Commun. 2011;2:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng J, Zagotta WN. Stoichiometry and assembly of olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron. 2004;42(3):411-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaupp UB. Olfactory signalling in vertebrates and insects: differences and commonalities. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(3):188-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hüttl S, Michalakis S, Seeliger M, et al. Impaired channel targeting and retinal degeneration in mice lacking the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel subunit CNGB1. J Neurosci. 2005;25(1):130-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michalakis S, Reisert J, Geiger H, et al. Loss of CNGB1 protein leads to olfactory dysfunction and subciliary cyclic nucleotide-gated channel trapping. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(46):35156-35166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge Z, Bowles K, Goetz K, et al. NGS-based molecular diagnosis of 105 eyeGENE probands with retinitis pigmentosa. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saqib MA, Nikopoulos K, Ullah E, et al. Homozygosity mapping reveals novel and known mutations in Pakistani families with inherited retinal dystrophies. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maranhao B, Biswas P, Gottsch AD, et al. Investigating the molecular basis of retinal degeneration in a familial cohort of Pakistani decent by exome sequencing. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez-Carro R, Corton M, Sánchez-Navarro I, et al. Panel-based NGS reveals novel pathogenic mutations in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bareil C, Hamel CP, Delague V, Arnaud B, Demaille J, Claustres M. Segregation of a mutation in CNGB1 encoding the beta-subunit of the rod cGMP-gated channel in a family with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Genet. 2001;108(4):328-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo H, Qin M, Mizota A, et al. A homozygosity-based search for mutations in patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa, using microsatellite markers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(12):4433-4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azam M, Collin RW, Malik A, et al. Identification of novel mutations in Pakistani families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(10):1377-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson DA, Clark GR, Alexander S, Silvestri G, Willoughby CE. Molecular diagnosis for heterogeneous genetic diseases with targeted high-throughput DNA sequencing applied to retinitis pigmentosa. J Med Genet. 2011;48(3):145-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bocquet B, Marzouka NA, Hebrard M, et al. Homozygosity mapping in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa families detects novel mutations. Mol Vis. 2013;19:2487-2500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu Q, Wang F, Wang H, et al. Next-generation sequencing–based molecular diagnosis of a Chinese patient cohort with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(6):4158-4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishiguchi KM, Tearle RG, Liu YP, et al. Whole genome sequencing in patients with retinitis pigmentosa reveals pathogenic DNA structural changes and NEK2 as a new disease gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(40):16139-16144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schorderet DF, Iouranova A, Favez T, Tiab L, Escher P. IROme, a new high-throughput molecular tool for the diagnosis of inherited retinal dystrophies. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:198089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang XF, Huang F, Wu KC, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation and mutation spectrum in a large cohort of patients with inherited retinal dystrophy revealed by next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2015;17(4):271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oishi M, Oishi A, Gotoh N, et al. Comprehensive molecular diagnosis of a large cohort of Japanese retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome patients by next-generation sequencing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(11):7369-7375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, Guan L, Shen T, et al. Mutations of 60 known causative genes in 157 families with retinitis pigmentosa based on exome sequencing. Hum Genet. 2014;133(10):1255-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao L, Wang F, Wang H, et al. Next-generation sequencing–based molecular diagnosis of 82 retinitis pigmentosa probands from Northern Ireland. Hum Genet. 2015;134(2):217-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maria M, Ajmal M, Azam M, et al. Homozygosity mapping and targeted Sanger sequencing reveal genetic defects underlying inherited retinal disease in families from Pakistan. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fradin M, Colin E, Hannouche-Bared D, et al. Run of homozygosity analysis reveals a novel nonsense variant of the CNGB1 gene involved in retinitis pigmentosa 45. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37(3):357-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hull S, Attanasio M, Arno G, et al. Clinical characterization of CNGB1-related autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(2):137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karstensen HG, Mang Y, Fark T, Hummel T, Tommerup N. The first mutation in CNGA2 in two brothers with anosmia. Clin Genet. 2015;88(3):293-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sailani MR, Jingga I, MirMazlomi SH, et al. Isolated congenital anosmia and CNGA2 mutation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G. “Sniffin’ Sticks”: olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses. 1997;22(1):39-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo H, Matsuda T, Hashiba M, Baba S. A study of the relationship between the T&T olfactometer and the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test in a Japanese population. Am J Rhinol. 1998;12(5):353-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hummel T, Kobal G, Gudziol H, Mackay-Sim A. Normative data for the “Sniffin’ Sticks” including tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds: an upgrade based on a group of more than 3,000 subjects. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(3):237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hummel T, Kobal G Olfactory event–related potentials. In: Simon SA, Nicolelis MAL, eds. Methods and Frontiers in Chemosensory Research Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2001:429-464. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huart C, Rombaux P, Hummel T, Mouraux A. Clinical usefulness and feasibility of time-frequency analysis of chemosensory event-related potentials. Rhinology. 2013;51(3):210-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schriever VA, Han P, Weise S, Hösel F, Pellegrino R, Hummel T. Time frequency analysis of olfactory induced EEG-power change. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eisenberger T, Neuhaus C, Khan AO, et al. Increasing the yield in targeted next-generation sequencing by implicating CNV analysis, non-coding exons and the overall variant load: the example of retinal dystrophies. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glöckle N, Kohl S, Mohr J, et al. Panel-based next generation sequencing as a reliable and efficient technique to detect mutations in unselected patients with retinal dystrophies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(1):99-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Randazzo NM, Shanks ME, Clouston P, MacLaren RE. Two novel CAPN5 variants associated with mild and severe autosomal dominant neovascular inflammatory vitreoretinopathy phenotypes [published online October 17, 2017]. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takagi SF. A standardized olfactometer in Japan: a review over ten years. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;510:113-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. ; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEwen DP, Koenekoop RK, Khanna H, et al. Hypomorphic CEP290/NPHP6 mutations result in anosmia caused by the selective loss of G proteins in cilia of olfactory sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(40):15917-15922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulaga HM, Leitch CC, Eichers ER, et al. Loss of BBS proteins causes anosmia in humans and defects in olfactory cilia structure and function in the mouse. Nat Genet. 2004;36(9):994-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iannaccone A, Mykytyn K, Persico AM, et al. Clinical evidence of decreased olfaction in Bardet-Biedl syndrome caused by a deletion in the BBS4 gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;132A(4):343-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brinckman DD, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Blumhorst C, et al. Cognitive, sensory, and psychosocial characteristics in patients with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(12):2964-2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braun JJ, Noblet V, Durand M, et al. Olfaction evaluation and correlation with brain atrophy in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Clin Genet. 2014;86(6):521-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zrada SE, Braat K, Doty RL, Laties AM. Olfactory loss in Usher syndrome: another sensory deficit? Am J Med Genet. 1996;64(4):602-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skjeldal OH, Stokke O, Refsum S, Norseth J, Petit H. Clinical and biochemical heterogeneity in conditions with phytanic acid accumulation. J Neurol Sci. 1987;77(1):87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van den Brink DM, Brites P, Haasjes J, et al. Identification of PEX7 as the second gene involved in Refsum disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(2):471-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibberd FB, Feher MD, Sidey MC, Wierzbicki AS. Smell testing: an additional tool for identification of adult Refsum’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(9):1334-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petersen-Jones SM, Occelli LM, Winkler PA, et al. Patients and animal models of CNGβ1-deficient retinitis pigmentosa support gene augmentation approach. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(1):190-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahonen SJ, Arumilli M, Lohi H. A CNGB1 frameshift mutation in Papillon and Phalène dogs with progressive retinal atrophy. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkler PA, Ekenstedt KJ, Occelli LM, et al. A large animal model for CNGB1 autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biel M, Zong X, Ludwig A, Sautter A, Hofmann F. Molecular cloning and expression of the modulatory subunit of the cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(11):6349-6355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sautter A, Zong X, Hofmann F, Biel M. An isoform of the rod photoreceptor cyclic nucleotide-gated channel β subunit expressed in olfactory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(8):4696-4701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bönigk W, Bradley J, Müller F, et al. The native rat olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channel is composed of three distinct subunits. J Neurosci. 1999;19(13):5332-5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugimoto Y, Yatsunami K, Tsujimoto M, Khorana HG, Ichikawa A. The amino acid sequence of a glutamic acid–rich protein from bovine retina as deduced from the cDNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(8):3116-3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Körschen HG, Illing M, Seifert R, et al. A 240 kDa protein represents the complete β subunit of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel from rod photoreceptor. Neuron. 1995;15(3):627-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ardell MD, Bedsole DL, Schoborg RV, Pittler SJ. Genomic organization of the human rod photoreceptor cGMP-gated cation channel β-subunit gene. Gene. 2000;245(2):311-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Körschen HG, Beyermann M, Müller F, et al. Interaction of glutamic-acid–rich proteins with the cGMP signalling pathway in rod photoreceptors. Nature. 1999;400(6746):761-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poetsch A, Molday LL, Molday RS. The cGMP-gated channel and related glutamic acid–rich proteins interact with peripherin-2 at the rim region of rod photoreceptor disc membranes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(51):48009-48016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Michalakis S, Zong X, Becirovic E, et al. The glutamic acid–rich protein is a gating inhibitor of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. J Neurosci. 2011;31(1):133-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wehling E, Nordin S, Espeseth T, Reinvang I, Lundervold AJ. Unawareness of olfactory dysfunction and its association with cognitive functioning in middle aged and old adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;26(3):260-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]