SUMMARY

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) kills infected macrophages by inhibiting apoptosis and promoting necrosis. The tuberculosis necrotizing toxin (TNT) is a secreted nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) glycohydrolase that induces necrosis in infected macrophages. Here, we show that NAD+ depletion by TNT activates RIPK3 and MLKL, key mediators of necroptosis. Notably, Mtb bypasses the canonical necroptosis pathway since neither TNF-α nor RIPK1 are required for macrophage death. Macrophage necroptosis is associated with depolarized mitochondria and impaired ATP synthesis, known hallmarks of Mtb-induced cell death. These results identify TNT as the main trigger of necroptosis in Mtb-infected macrophages. Surprisingly, NAD+ depletion itself was sufficient to trigger necroptosis in a RIPK3- and MLKL-dependent manner by inhibiting the NAD+ salvage pathway in THP-1 cells or by TNT expression in Jurkat T cells. These findings suggest avenues for host-directed therapies to treat tuberculosis and other infectious and age-related diseases in which NAD+ deficiency is a pathological factor.

In Brief

Pajuelo et al. show that NAD+ hydrolysis by tuberculosis necrotizing toxin (TNT) induces necroptosis. NAD+ depletion alone is sufficient to activate RIPK3 and MLKL, bypassing canonical necroptosis initiation. These findings suggest ways to treat tuberculosis and other diseases in which NAD+ deficiency is a pathological factor.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is the causative agent of tuberculosis, a devastating disease with more than 10 million new cases and over 1.4 million reported deaths in 2016 (WHO, 2017). However, in healthy individuals, Mtb causes persistent infection with no disease symptoms, indicating that Mtb avoids host immune responses (Behar et al., 2010). A key mechanism determining the outcome of infection is the ability of Mtb to induce and alter cellular death pathways in alveolar macrophages (Behar et al., 2010). To control Mtb replication, alveolar macrophages attempt to initiate apoptosis (Behar et al., 2011), a host programmed cell death resulting in containment of the bacteria, increased bacterial killing, reduced inflammation, and enhanced antigen presentation (Liu et al., 2015). However, virulent Mtb strains are capable of triggering a necrosis-like cell death that is associated with higher mycobacterial replication, strong inflammation, dissemination, and disease progression (Behar et al., 2010; Lerner et al., 2017). Intracellular replication of Mtb plays a critical role in determining the fate of the infected cell. If a critical ‘‘burst’’ size is reached (>25 bacilli per cell) the host cell undergoes an atypical, necrotic-like cell death characterized by lysosomal permeabilization, mitochondrial damage, and membrane destruction. In contrast, macrophages with a low bacillary burden undergo apoptosis, leading to a more advantageous outcome for the host (Chen et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2006; Repasy et al., 2013).

Recently, we identified CpnT, an outer membrane protein of Mtb consisting of an N-terminal channel domain that is used for nutrient uptake; the secreted C-terminal domain is the major cytotoxicity factor of Mtb in macrophages and induces necrosis-like cell death in eukaryotic cells (Danilchanka et al., 2014). The C-terminal domain of CpnT, now known as tuberculosis necrotizing toxin (TNT), is secreted into the cytosol of Mtb-infected macrophages, where it hydrolyzes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) (Danilchanka et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2015). The catalytic activity of TNT is required to trigger necrosis of infected macrophages (Sun et al., 2015), but the molecular mechanisms connecting NAD+ depletion and necrosis remained unknown.

Here, we describe TNT as a specific Mtb factor triggering necroptosis, a programmed necrotic cell death pathway executed by activation of receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinases (RIPK) 1 and 3 and the effector molecule mixed-lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) (Vanden Berghe et al., 2014). The canonical pathway to initiate necroptosis is by activation of Fas/ CD95 or tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) and occurs simultaneously with inhibition of caspase-8 (Newton and Manning, 2016). In this study, we show that NAD+ depletion by TNT activates RIPK3 and MLKL to initiate necroptosis independent of RIPK1 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). The catalytic activity of TNT also damages mitochondria and depletes cellular ATP. Inhibition of RIPK3 or MLKL protects macrophages from the cytotoxicity of Mtb to the same level as inactivation or absence of TNT. Thus, the cytotoxicity of Mtb is mainly mediated by initiating necroptosis through the activity of TNT. In fact, NAD+ depletion itself is sufficient to trigger necroptosis. These results reveal additional mechanisms for host-targeted therapies in tuberculosis.

RESULTS

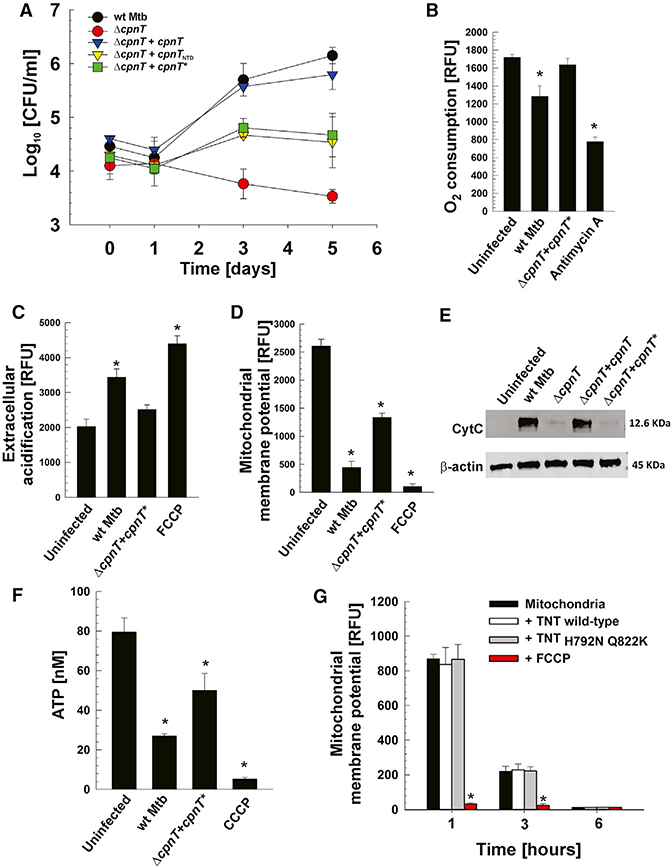

The Catalytic Activity of TNT Induces Mitochondrial Damage and Dysfunction

To examine the molecular mechanism of TNT-induced cell death, we used the human macrophage cell line THP-1 as an infection model (Mendoza-Coronel and Castañón-Arreola, 2016; Riendeau and Kornfeld, 2003). Mtb strains (Table S1) secreting functional TNT replicated and increased cell numbers by 10- to 30-fold after 3–5 days, whereas the ΔcpnT deletion mutant did not replicate and was slowly killed (Figure 1A). Mtb producing only the N-terminal domain (NTD) of CpnT (Mtb ΔcpnT+cpnTNTD) and full-length CpnT with a mutated, non-catalytic TNTH790N/Q822K domain (Mtb ΔcpnT+cpnT*) (Table S1) replicated, but growth stopped at 10-fold lower bacterial numbers compared with wild-type (WT) Mtb (Figure 1A). These results indicated that the catalytic activity of TNT is important for survival and replication of Mtb in macrophages. To examine whether NAD+ depletion by TNT impairs mitochondrial function or integrity, we analyzed mitochondrial health in Mtb-infected THP-1 macrophages. We observed that the oxygen consumption of macrophages 48 hr after infection with WT Mtb was lower than that of uninfected cells, whereas the Mtb strain producing CpnT* did not reduce the oxygen consumption of infected macrophages (Figure 1B). Stressed or damaged mitochondria produce less ATP, which leads to increased glycolysis to compensate for the energy loss and results in extracellular acidification. Infection of macrophages with WT Mtb increased extracellular acidification 2-fold compared with uninfected macrophages (Figure 1C). No difference was found when the macrophages were infected with Mtb producing CpnT* (Figure 1C). The mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was also reduced by 5-fold in Mtb-infected macrophages compared with the uninfected control. Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential was decreased by 2-fold when TNT was inactivated (Figure 1D). These results establish that the catalytic activity of TNT is an important factor in depolarizing mitochondria.

Figure 1. The NAD+ Glycohydrolase Activity of TNT Is Important for Intracellular Replication and Indirectly Damages Mitochondria and Inhibits Their Function.

(A-F) THP-1 cells were infected with Mtb strains at an MOI of 10:1 and analyzed 48 hr after infection

(B-F) or at the indicated time points.

(A) Viable intracellular bacterial count (colony-forming units [CFUs] per milliliter).

(B) Oxygen consumption was measured with the oxygen-sensitive fluorescent probe p-iso-thiocyanatophenyl, a derivative of platinum(II)-coproporphyrin-I.

(C) Extracellular acidification was measured with the pH-sensitive fluorescent probe Eu3+ chelate CS370-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA)-hydrazide.

(D) Mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed by using a JC-1 dye-based fluorescent probe.

(E) Mitochondrial cytochrome c (CytC) release into the cytosol.

(F) Cellular ATP concentration was measured with a luminescent ATP detection assay kit.

(G) Purified mitochondria from THP-1 cells were incubated in 20 mM Tris and 200 mM NaCl at pH 7.6 with 1 μg of purified WT or non-catalytic mutant (TNTh792n q822k)TNT protein and analyzed for mitochondrial membrane potential status by using a JC-1 dye-based fluorescent probe.

Antimycin A (10 μM), inhibitor of complex III of the electron transport chain; carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) (4 μM), uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation; β-actin, loading control. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction compared with uninfected (B-F) or non-treated (G) conditions. See Figures S1 and S2 for related data.

Cytochrome c release from the mitochondria to the cytosol is a sign of outer membrane damage and permeabilization (Ott et al., 2002). Infection with Mtb strains producing functional TNT released a significant amount of cytochrome c, whereas only marginal amounts of cytochrome c were detected in the cytosol of macrophages infected with the ΔcpnT mutant or the Mtb strain secreting non-catalytic TNT (Figure 1E). A consequence of mitochondrial damage and dysfunction is decreased production of cellular ATP. As expected, the total ATP level in macrophages infected with WT Mtb or mutant Mtb producing non-catalytic TNT was lower compared with the uninfected control (Figure 1F).

Interpretation of the loss of mitochondrial damage and ATP depletion induced by the non-catalytic mutant is complicated by the fact that this strain does not replicate at the level of WT Mtb, reducing the bacterial load. To address this, we used the strain Mtb mc26206, a derivative of H37Rv that lacks the genes panCD and leuCD, which are not involved in virulence or drug resistance (Sampson et al., 2004), and a non-catalytic TNT mutant with the same two point mutations as in the virulent strain (H792N/Q822K, Mtb mc26206 ΔcpnT+cpnT*). None of these strains replicated in macrophages (Figure S1A). However, the induced mitochondrial dysfunction and depolarization and the decrease in ATP levels were similar to those induced by the H37Rv and derivative strains (Figures S1B-S1E), indicating that the observed differences were not a consequence of reduced bacterial replication but were, instead, dependent on the catalytic activity of TNT. Taken together, these results demonstrate that NAD+ degradation by TNT leads to permeabilization of both mitochondrial outer and inner membranes and decreases the membrane potential, the respiration rate of mitochondria, and ATP production in macrophages infected with Mtb.

TNT Does Not Damage Mitochondria Directly

The results described above show that TNT damages mitochondria and decreases ATP production, but it is not clear whether this is a consequence of a direct interaction between TNT and mitochondria or whether TNT induces a signaling pathway that leads to mitochondrial damage because of NAD+ depletion. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we incubated isolated mitochondria from THP-1 macrophages with purified TNT and the non-catalytic TNT mutant proteins (Figures S2). The mitochondrial membrane potential was not altered by TNT nor by the non-catalytic mutant throughout the experiment (Figure 1G) suggesting that NAD+ degradation by TNT indirectly damages mitochondria.

TNT Activates RIPK3 and MLKL in Human THP-1 Macrophages Infected with Mtb

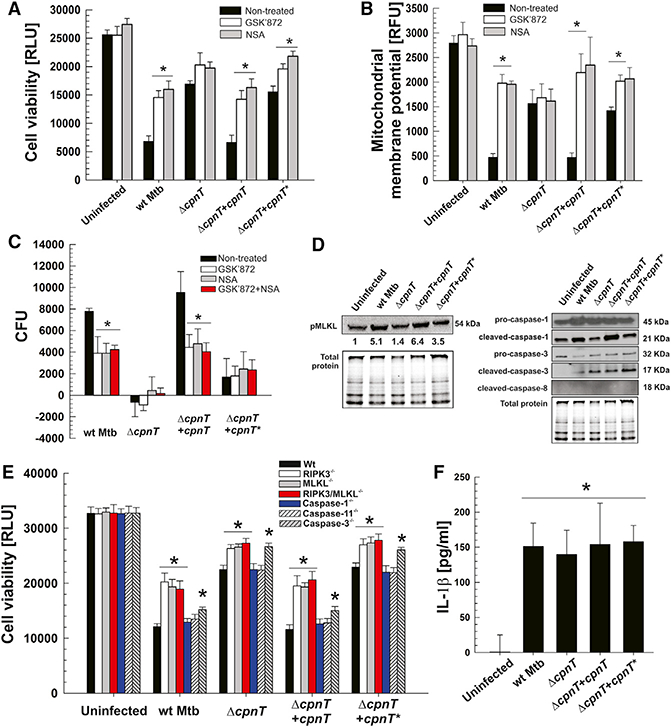

At least three molecular mechanisms may account for the observed mitochondrial damage by TNT. NAD+ is an essential co-factor in crucial cellular processes, and, hence, loss of NAD+ may cause necrotic cell death by metabolic collapse (Zong and Thompson, 2006). Alternatively, TNT could hijack a cytoplasmic protein that is imported by mitochondria (Harbauer et al., 2014) and enable TNT to degrade the mitochondrial NAD+ pool directly. NAD+ depletion by TNT could also activate cellular signaling pathways executing programmed necrotic cell death (Wang et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2016). Because we did not find any evidence for TNT localization to mitochondria, and because it was recently shown that NAD+ depletion by itself does not affect cellular ATP levels (Fouquerel et al., 2014), we tested the hypothesis that TNT triggers programmed necrosis, also termed necroptosis (Wang et al., 2014). To this end, we examined the requirement of RIPK1, RIPK3, or MLKL, key mediators of necroptosis (Vanden Berghe et al., 2014), during TNT-induced macrophage necrosis. As previously shown, the RIPK1 inhibitor necrostatin-1 s(Nec-1s) rescued cells treated with TNF-α, cyclo-heximide, and carbobenzoxy-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-[O-methyl]-fluoromethylketone (zVAD-fmk) (T/C/Z) (Cho et al., 2009), which induce necroptosis by formation of the RIPK1-RIPK3 complex (Wang et al., 2014; Figure S3A). However, Nec-1s did not protect against cell death in Mtb-infected THP-1 macrophages (Figure S3B), ruling out a role for RIPK1 in Mtb-induced cell death (Vanden Berghe et al., 2014). In contrast, both GSK’872 and necrosulfonamide, inhibitors of RIPK3 (Kaiser et al., 2013) and MLKL (Sun et al., 2012), respectively, protected THP-1 macrophages from cell death by Mtb (Figure 2A) at concentrations that were not toxic for Mtb (Figure S4). The protective effect of inhibiting RIPK3 and MLKL was completely abolished or largely reduced in infections with Mtb strains lacking cpnT or expressing inactive cpnT (cpnT*), suggesting that the catalytic activity of TNT somehow activates RIPK3 and MLKL. Importantly, GSK’872 and necrosulfonamide also markedly reduced mitochondrial depolarization in Mtb-infected THP-1 macrophages (Figure 2B). This mitochondrial protection by GSK’872 and necrosulfonamide was completely dependent on cpnT (Figure 2B). Interestingly, we observed a small but significant rescue of the mitochondrial membrane potential when the pretreated macrophages were infected with the Mtb strain producing CpnT with the catalytically inactive TNT mutant compared with the ΔcpnT mutant (Figure 2B). A potential explanation for this observation is that the functional N-terminal channel of CpnT* increases nutrient uptake and intracellular replication of Mtb (Figures 1A, 2C, and S5), as observed earlier (Danilchanka et al., 2014), enhancing production of other Mtb factors that contribute to cell death. Treatment with GSK’872 or necrosulfonamide was also associated with reduced intracellular replication of Mtb strains expressing functional TNT, and no synergistic effect was observed when both compounds were used (Figures 2C and S5). This may reflect the improved mitochondrial health in infected macrophages after inhibition of MLKL or RIPK3 and suggests that they are part of the same pathway. Notably, less phosphorylated MLKL protein (pMLKL, the active form of MLKL) was detected when macrophages infected with the cpnT deletion mutant and Mtb producing the catalytically inactive TNT mutant were analyzed by western blot (Figure 2D). Furthermore, the cleaved forms of caspase-3 and caspase-1, respectively involved in apoptosis and pyroptosis, were also detected in THP-1 macrophages, regardless which strain was used for infection (Figure 2D), suggesting that other pathways might also be active during macrophage death. However, lower levels of cleaved caspase-1 were found in strains lacking functional TNT (Figure 2D), suggesting that the enzymatic activity of TNT and/or the intracellular growth defect of these strains may be important for activation of pyroptosis. In conclusion, these experiments clearly showed that MLKL is activated by TNT in THP-1 macrophages infected with Mtb and that other TNT-independent mechanisms are also involved.

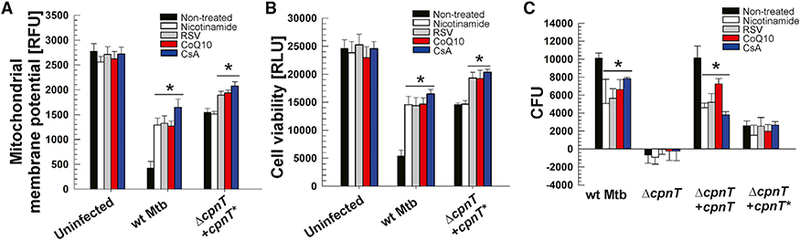

Figure 2. TNT Induces Necroptosis in Macrophages Infected with Mtb.

THP-1 cells were treated (when indicated) with 10 μM of GSK’872 or necrosulfonamide (NSA) and infected with Mtb strains at an MOI of 10:1 for 48 hr.

(A) Cell viability was measured as the total ATP content with a luminescent ATP detection assay kit.

(B) Mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed by using a JC-1 dye-based fluorescent probe.

(C) Increase of Mtb intracellular growth (CFUs per milliliter) from 4 hr to 48 hr post-infection.

(A-C) *p < 0.05, calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction compared with non-treated conditions.

(D) Western blot for pMLKL (phospho S358), pro- and cleaved caspase-1, pro- and cleaved cas-pase-3, and cleaved caspase-8 in the whole-cell lysates of THP-1 cells infected with Mtb strains. Protein levels relative to uninfected samples (and adjusted fortotal protein loading) were quantitated by densitometry and are represented as the fold increase for the pMLKL panel.

(E) Bone marrow-derived macrophages were isolated from mice on a C57BL/6J (Ripk3−/−,Mlkl−/−, Ripk3-Mlk−/− and Casp-3−/−) or mixed C57BL/ 6J-C57BL/6N (Casp-1−/− and Casp-11−/−) genetic background and infected with Mtb strains at an MOI of 10:1, and cell viability (measured as the total ATP content with a luminescent ATP detection assay kit) was analyzed 48 hr post-infection. Statistical analysis (*p < 0.05, calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction) was performed on each Mtb infection group (uninfected and infected with each Mtb strain) independently. For each infection group, statistical significance was determined between WT C57BL/ 6J mouse macrophages and derived knockouts.

(F) Levels of IL-1 β detected by ELISA in supernatants from THP-1 cells infected with Mtb strains at an MOI of 10:1 for 48 hr. *p < 0.05, calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction compared with the uninfected condition. (G) Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See Figures S3-S5 for related data.

Deletion of the Mlkl and Ripk3 Genes Partially Protects Mouse Macrophages from TNT-Induced Cell Death

To assess the relative contribution of different cell death mediators to macrophage death, we used bone marrow-derived macrophages from C57BL/6J mice and measured macrophage viability following infection by Mtb. Macrophages deficient in caspase-1 and caspase-11 did not show any protection against cell death compared with WT macrophages independent of the Mtb strain used for infection, demonstrating that the macrophages do not die by pyroptotic cell death (Yuan et al., 2016; Figure 2E). Caspase-3-deficient macrophages survived slightly better when infected with any of the Mtb strains, suggesting that a small percentage of WT macrophages underwent apoptosis (Danke et al., 2010) in a TNT-independent manner (Figure 2E). In contrast, the cell viability of knockout macrophages in the necroptosis-related genes Ripk3, Mlkl, and Rikp3/Mlkl (Wang et al., 2014) was markedly increased compared with WT macrophages when infected with Mtb (Figure 2E). Importantly, the cell viability of Ripk3−/− and Mlkl−/− macrophages infected with an Mtb strain producing functional TNT increased by 80%, whereas the increase was less than 10% in macrophages infected with the ΔcpnT mutant or the non-catalytic TNT mutant (Figure 2E). This demonstrated that RIPK3 and MLKL play major roles in mediating cell death induced by NAD+ depletion by TNT. The results also showed that TNT accounts for approximately half of the cytotoxicity of Mtb in infected macrophages, as observed earlier (Danilchanka et al., 2014), and indicated that TNT induces mostly programmed necrotic cell death. Interestingly, no differences were found between macrophages with single Ripk3−/− and Mlkl−/− deletions and the double gene deletion Rikp3/Mlkl−/−, suggesting that, in these macrophages, RIPK3 and MLKL act in the same cell death pathway.

In previous studies, caspase-1 activation and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) production were detected in Mtb-infected macrophages without undergoing pyroptosis (Dorhoi et al., 2012; Welin et al., 2011). We measured IL-1β production in Mtb-infected macrophages and found that similar amounts of IL-1β are produced by all macrophages after infection regardless of whether functional TNT was secreted by Mtb (Figure 2F). Furthermore, the survival of macrophages deficient in caspase-1 and caspase-11 is not improved compared with WT macrophages (Figure 2E), suggesting that, although caspase-1 is activated by TNT (Figure 2D), cell death is not dependent on this caspase. Taken together, these results revealed that NAD+ depletion by TNT activates the essential “necrosome” components MLKL and RIPK3, which induce programmed necrotic cell death in Mtb.

TNF-α Is Not Involved in TNT-Induced Cell Death of Macrophages Infected with Mtb

Several studies indicate the importance of TNF-α in Mtb-mediated cell death (Butler et al., 2017; Cavalcanti et al., 2012). To examine whether TNF-α also plays a role in cell death triggered by TNT in human macrophages, we utilized inhibitors of TNF-α and TNFR1: SPD304 and R7050, respectively (González-Juarbe et al., 2017). Although Mtb reduced the viability of infected THP-1 macrophages as expected, neither the TNFR1 inhibitor R7050 nor the TNF-α inhibitor SPD304 increased their cell viability (Figure S3C), suggesting that TNF-α is not required for TNT-induced necroptosis.

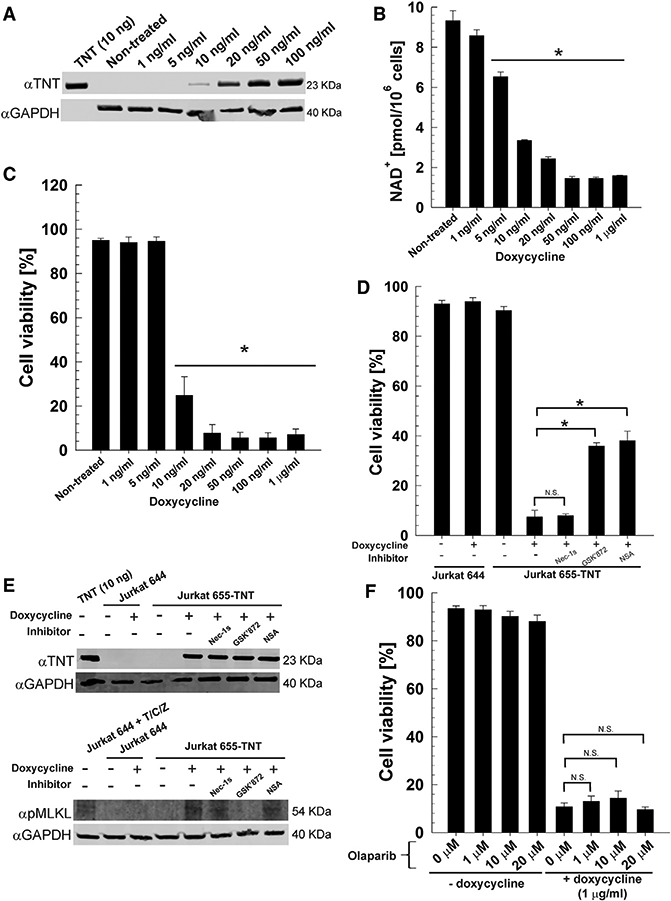

The TNT Protein Is Sufficient to Induce RIPK1-Independent Necroptosis

In a previous study, we showed that expression of the tnt gene in Jurkat T cells (Jurkat 655-TNT) induced a necrotic-like cell death that was not prevented by necrostatin-1, indicating RIPK1-independent necrosis (Danilchanka et al., 2014). In this experimental model, tnt expression was tightly controlled by tetracycline or tetracycline derivatives. Our aim was to control the level of NAD+ depletion in Jurkat T cells and establish a threshold NAD+ level that triggers necroptotic cell death. To this end, we first determined doxycycline concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 ng/mL, which established different TNT levels (Figure 3A). These doxycycline concentrations indeed reduced cellular NAD+ by distinct levels, ranging from 9.2 pmol/million cells in non-treated cells to 1.5 pmol/million cells at 50 ng/mL doxycycline. These experiments also showed that even TNT levels undetectable by western blot led to a significant degradation of NAD+ (Figure 3B). Importantly, the cell viability of Jurkat T cells was only affected when NAD+ levels were reduced by at least 65% to 3.2 pmol/million cells or less. Almost complete cytotoxicity was observed when the cellular NAD+ concentration was approximately 2 pmol/million of cells, corresponding to a depletion of approximately 80% NAD+ (Figure 3C). To examine whether TNT-induced cell death of Jurkat T cells is also mediated by the necroptotic pathway as in Mtb-infected macrophages, we treated Jurkat T cells with the RIPK3 and MLKL inhibitors GSK’872 and necrosulfonamide in the presence of 1 mg/mL doxycycline to maximize tnt expression and cytotoxicity. As expected, cell death was observed in the Jurkat 655-TNT but not in the control Jurkat 644 cell line upon treatment with doxycycline (Figure 3D). Importantly, inhibition of RIPK3 and MLKL afforded protection from TNT-induced cell death, whereas inhibition of RIPK1 with Nec1s did not have any beneficial effect on cell viability (Figure 3D), demonstrating that TNT alone is sufficient to induce RIPK3/MLKL-dependent necroptotic cell death without the presence of bacteria. This conclusion is supported by the detection of phosphorylated MLKL in tnt-expressing Jurkat T cells, which was prevented with the RIPK3 inhibitor GSK’872 (Figure 3E) but not by necrosulfonamide, as observed previously (Sun et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). Of note, NAD+ depletion and subsequent death in mammalian cells is also observed by (over)activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), NAD+-consuming enzymes involved in DNA repair (Morales et al., 2014). However, inhibition of PARP1 and PARP2, the two main isoforms involved in DNA repair and NAD+ depletion, with the inhibitor olaparib (Menear et al., 2008) did not result in any protection, ruling out the involvement of PARPs in TNT-mediated death (Figure 3F).

Figure 3. TNT Induces Necroptosis in Jurkat T Cells.

Expression of TNT in the Jurkat T cell line containing an integrated Tet-regulated TNT expression cassette (Jurkat J655-TNT) was induced with doxycycline for 24 hr. The Jurkat T cell line J644 was included as a control. When indicated, cells were treated with 10 μM of necrostatin-1 s (Nec-1s), GSK’872, or necrosulfonamide.

(A) Western blot for TNT (purified specific polyclonal antibody) and GAPDH (loading control) in the whole-cell lysates of Jurkat J655-TNT cells induced with the indicated doxycycline concentrations. Purified WT TNT protein (Figure S2) was included as a control.

(B) NAD+ levels of Jurkat J655-TNT cells induced with the indicated doxycycline concentrations.

(C) Cell viability measured by trypan blue staining of Jurkat J655-TNT cells induced with the indicated doxycycline concentrations.

(D) Cell viability measured by trypan blue staining of Jurkat J644 and J655-TNT cells induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline in the presence of the RIPK3 and MLKL inhibitors GSK’872 and necrosulfonamide, respectively, and the RIPK1 inhibitor Nec-1 s.

(E) Western blot for TNT (purified specific poly clonal antibody), pMLKL (monoclonal pMLKL antibody, phospho S358) and GAPDH (loading control) in the whole-cell lysates of Jurkat J644 and J655-TNT cells induced with 1 μg/mL doxy-cycline or treated with TNF-α, cycloheximide, and zVAD-fmk (T/C/Z) (Cho et al., 2009). Purified WT TNT protein (Figure S2) was included as control.

(F) Cell viability measured by trypan blue staining of Jurkat J655-TNT cells induced with 1 μg/mL doxycycline plusthe PARP inhibito rolaparib at the indicated concentrations.

*p < 0.05, calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction compared with the non-treated (B and C) or indicated (D and F) conditions (N.S., not significant). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

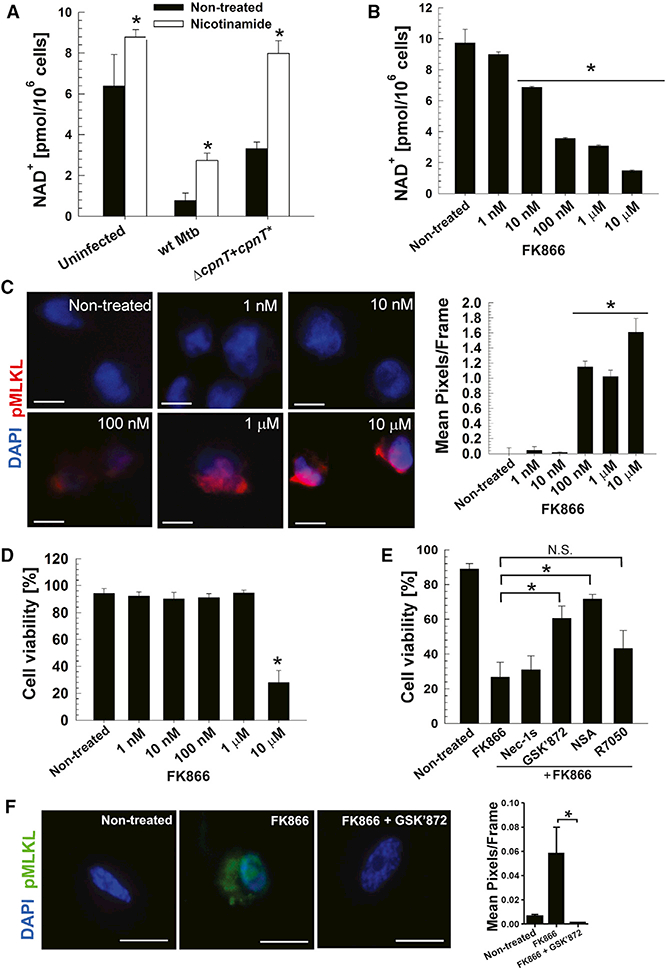

NAD+ Depletion in Macrophages Infected with Mtb Is Mainly Caused by TNT and Is Partially Compensated by Nicotinamide Supplementation

Because the oxidized form of NAD+ is 100-fold more prevalent than its reduced form in cells under physiological conditions (Ying, 2008), we measured NAD+ levels in THP-1 macrophages infected with Mtb. Infection with WT Mtb drastically decreased NAD+ levels. The NAD+ concentration increased 5-fold when the macrophages were infected with an Mtb strain producing inactive TNT (Figure 4A). Importantly, the devastating effect of TNT on cellular NAD+ levels was decreased 4-fold after providing nicotinamide, a precursor of NAD+ biosynthesis, to the macrophages at a concentration that was not toxic for Mtb (Figure S4). NAD+ was completely restored by nicotinamide supplementation in macrophages infected with the Mtb strain producing inactive TNT (Figure 4A). These results show that TNT is the main cause for depletion of NAD+ in macrophages infected with Mtb and indicate that stimulating NAD+ synthesis in infected macrophages might be a feasible therapeutic approach.

Figure 4. NAD+ Depletion Triggers Necroptosis in THP-1 Cells.

(A) NAD+ levels of THP-1 cells treated with nicotinamide (5 mM) and infected with Mtb strains at an MOI of 10:1 for 48 hr.

(B) NAD+ levels of THP-1 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of FK866 for 6 hr.

(C) Immunofluorescence for pMLKL (monoclonal pMLKL antibody, red, phospho S358) and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in THP-1 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of FK866 for 6 hr. Scale bars, 10 μm. Mean pixels per frame analysis of captured images was determined using ImageJ.

(D) Cell viability measured by trypan bluestaining of THP-1 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of FK866 for 6 hr.

(E) Cell viability measured by trypan blue staining in THP-1 cells treated with 10 μM of FK866, Nec-1s, GSK’872, necrosulfonamide, or R7050 for 6 hr.

(F) Immunofluorescence for pMLKL (monoclonal pMLKL antibody, green, phospho S358) and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in THP-1 cells treated with 10 mM of FK866 and/or GSK’872 for 6 hr. Scale bars, 10 μm. Mean pixels per frame analysis of captured images was determined using ImageJ.

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction compared with the non-treated (A-D) or the indicated (E and F) conditions.

NAD+ Depletion Triggers Necroptosis in Macrophages

To examine whether NAD+ depletion independent of TNT is capable of triggering the necroptotic cell death pathway in THP-1 macrophages, we inhibited nicotinamide phosphoribo-syltransferase (NAMPT), a key enzyme in the NAD+ salvage pathway, with FK866 (Hasmann and Schemainda, 2003). FK866 treatment depleted the NAD+ pool within 6 hr in a concentration-dependent manner, from 9.6 to 1.2 pmol/million cells in the presence of 10 μM FK866 (Figure 4B). Interestingly, reducing the NAD+ level to 3.2 pmol/million cells or below resulted in activation of necroptosis, determined by phosphorylation of MLKL, as shown by immunofluorescence (Figure 4C). However, similar to Jurkat T cells, NAD+ depletion by 80% by treatment with 10 μM FK866 was required to decrease cell viability (Figure 4D). As expected, FK866-induced cell death was not prevented by inhibiting RIPK1 using Nec-1s or the TNFR1 receptor using R7050 (Figure 4E). In contrast, inhibition of RIPK3 and MLKL with GSK’872 and necrosulfonamide, respectively, partially restored the cell viability of the macrophages (Figure 4E). In addition, inhibition of RIPK3 by treatment with GSK’872 prevented phosphorylation of MLKL (Figure 4F). These results demonstrate that NAD+ depletion itself, regardless of the mechanism, triggers necroptosis in THP-1 macrophages downstream of RIPK1. These results also indicate that mammalian cells require a minimal NAD+ level to prevent necroptosis.

NAD+ Replenishment and Protection of Mitochondrial Health Alleviates TNT Cytotoxicity

Interestingly, NAD+ replenishment also increased the mitochondrial membrane potential and cell viability of Mtb-infected macrophages by 3-fold (Figures 5A and5B), but the cell viability did not reach the level of uninfected macrophages, probably because NAD+ replenishment by nicotinamide is limited (Figure 4A). As expected, this effect was dependent on the catalytic activity of TNT because nicotinamide treatment did not change the mitochondrial membrane potential and cell viability of macrophages infected with the Mtb strain producing inactive TNT (Figures 5A and5B).

Figure 5. TNT-Dependent Mitochondrial Toxicity Can Be Rescued by NAD+ Replenishment and Enhancement and Protection of Mitochondrial Function.

THP-1 cells were pretreated with nicotinamide (5 mM), resveratrol (RSV, 100 μΜ), CoenzymeQ10 (CoQ10,100 μΜ) or cyclosporin A (CsA, 5 μΜ), infected with Mtb strains at an MOI of 10:1, and analyzed after 48 hr.

(A) Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using a JC-1 dye-based fluorescent probe.

(B) Cell viability was measured as the total ATP content with a luminescent ATP detection assay kit.

(C) Increase of Mtb intracellular growth (CFUs per milliliter) from 4 to 48 hr post-infection.

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction compared with non-treated conditions. See Figures S4 and S5 for related data.

Next we tested the hypothesis that protecting mitochondria or increasing their function would protect infected macrophages from TNT-induced toxicity. To this end, we treated Mtb-infected macrophages with resveratrol (RSV) and coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) to increase the number and respiration rate of mitochondria, respectively, and with cyclosporin A (CsA), a cyclophilin D inhibitor that prevents formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore (Gan et al., 2005; González-Juarbe et al., 2015). We observed that RSV, CoQ10, or CsA, at concentrations that were not toxic for Mtb (Figure S4), increased the mitochondrial membrane potential by 3- to 4-fold, respectively, in macrophages infected with Mtb (Figure 5A). In all experiments, the observed rescue was higher in macrophages infected with WT Mtb compared with Mtb producing non-catalytic TNT, indicating that the beneficial effects of CsA, RSV, and CoQ10 are, to a large extent, dependent on NAD+ hydrolysis of TNT (Figure 5A). These compounds also increased the cell viability of macrophages infected with WT Mtb by 3-fold, demonstrating that mitochondrial function is directly correlated with macrophage survival (Figure 5B). The beneficial effect of these treatments is mainly dependent on TNT, underlining the importance of TNT for the cytotoxicity of TNT in Mtb-infected macrophages. Importantly, supplementation of infected macrophages with nicotinamide, RSV, CoQ10, or CsA restricted the intracellular growth of WT Mtb and the complemented strain, whereas growth of the strain producing non-functional TNT remained unchanged (Figures 5C and S5). Taken together, our results highlight the importance of mitochondrial health during Mtb infection and show that preserving mitochondrial function alleviates the cytotoxicity induced by the NAD+ glycohydrolase activity of TNT.

DISCUSSION

Mtb kills infected macrophages by inhibiting apoptosis (Liu et al., 2015) and promoting necrosis, a type of cell death that is associated with higher mycobacterial replication, inflammatory response, and progression of tuberculosis (Behar et al., 2010). However, it is unclear which mechanisms Mtb uses to alter host cell death modes in its favor (Moraco and Kornfeld, 2014). In this study, we demonstrated that the Mtb toxin TNT damages mitochondria, a key event in the necrotic cell death of Mtb-infected macrophages (Chen et al., 2006; Duan et al., 2002; Jamwal et al., 2013). The observed mitochondrial damage is a consequence of the NAD+ glycohydrolase activity of TNT and does not require a direct interaction of TNT with mitochondria, in contrast to other Mtb proteins associated with mitochondria (Cadieux et al., 2011; Sohn et al., 2011). The key observation linking NAD+ depletion by TNT to necrotic cell death was that inhibition or lack of RIPK3 and/or MLKL protected Mtb-infected macrophages from TNT-induced cell death. These results were corroborated by the fact that the necrotic cell death induced by TNT in Jurkat T cells involves the same mediators as in Mtb-infected macrophages without the confounding influence of other factors during bacterial infection. These experiments conclusively demonstrated that TNT triggers necroptosis, a form of programmed cell death with molecular features similar to necrosis, preventing viruses from replication in infected cells (Dondelinger et al., 2016; Weinlich et al., 2017). These findings are consistent with recent results published by Zhao et al. (2017), who showed that cell death of macrophages infected with virulent Mtb is dependent on RIPK3 and MLKL and that Ripk3−/− mice were more resistant to Mtb infection than WT mice. Our study established that TNT is the main necroptosis-inducing factor in macrophages infected with Mtb. Other mechanisms may contribute to necrosis of Mtb-infected macrophages, such as uncharacterized cellular pathways targeting mitochondria (Cadieux et al., 2011; Moreno-Altamirano et al., 2012; Sohn et al., 2011).

Surprisingly, we observed that TNT-induced necroptosis does not require TNF-α signaling or RIPK1, one of the core components of the necrosome and the initial kinase that is activated upon TNF-α stimulation (de Almagro and Vucic, 2015; Vanden Berghe et al., 2014). TNF-α-dependent cell death of macrophages is associated with apoptosis (Riendeau and Kornfeld, 2003) and was observed with avirulent Mtb strains and/or low bacillary loads (Lee et al., 2006). Our observation that virulent Mtb bypasses the TNF-α receptor and RIPK1 activation and directly activates RIPK3 is consistent with previous studies (Riendeau and Kornfeld, 2003; Zhao et al., 2017). Roca and Ramakrishnan (2013) showed in zebrafish that Mycobacterium marinum induces RIPK1/RIPK3-dependent necroptosis in the presence of excess TNF-α. This difference between necroptosis induced by M. marinum and Mtb may be caused by the lack of a TNT homolog in M. marinum (Danilchanka et al., 2014). The CpnT homolog in M. marinum (MMAR_5464) has a similar N terminus, which is connected to a C-terminal ADP ribosyltransferase, suggesting that the role of this CpnT homolog is different compared with TNT. Although we found that TNF-α is dispensable for TNT-induced necroptosis, we cannot exclude that RIPK1 could be activated by higher levels of TNF-α, contributing to RIPK3 activation in addition to TNT in Mtb-infected cells. Other studies showed that Mtb-infected fibroblasts die from necroptosis via RIPK1-RIPK3-MLKL in a TNF-α-dependent manner (Butler et al., 2017) and that MLKL does not appear to be activated in Mtb-infected bone marrow-derived or J774.1 mouse macrophages (Butler et al., 2017; Stutz et al., 2018). These apparent discrepancies may result from cell-type-specific differences (Andreu et al., 2017).

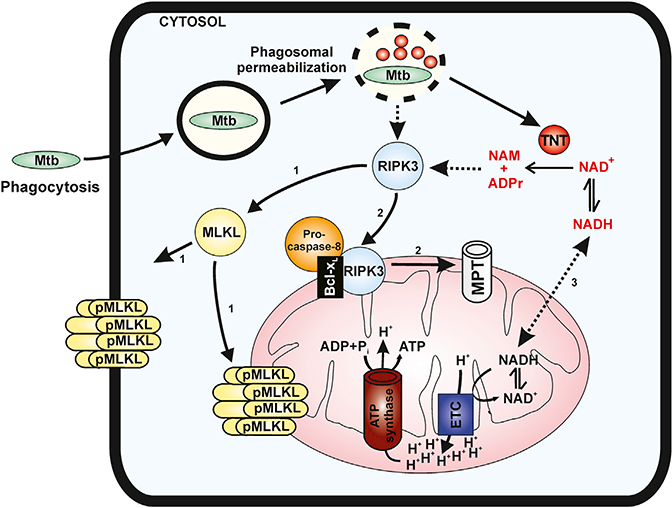

The results of our study lead to the following model for TNT-induced cell death of infected macrophages (Figure 6). After inhalation of Mtb into the lung, the bacteria are taken up by alveolar macrophages through phagocytosis. Mtb evades killing in the phagosome by blocking its fusion with lysosomes (Sun et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2011) and eventually permeabilizes the phagosomal membrane using the proteins ESAT-6 and CFP10, secreted by the ESX-1 system (Manzanillo et al., 2012; Simeone et al., 2012). This process enables Mtb proteins to enter the cytosol of the infected macrophages. One of those proteins is the NAD+ glycohydrolase TNT, which accounts for more than half of the NAD+ loss in Mtb-infected macrophages (Sun et al., 2015). Low cytosolic NAD+ levels induce at least three major molecular pathways in macrophages infected with Mtb. RIPK3 senses lower NAD+ levels and/or increased levels of its degradation products, nicotinamide and ADP-ribose, by an unknown mechanism. Activated RIPK3 phosphorylates MLKL, which then forms oligomeric pores in host cell membranes and induces necrotic death (pathway 1) (Wang et al., 2014). In addition, RIPK3 also migrates, together with Bcl-xL, to mitochondria (pathway 2). The RIPK3-Bcl-xL complex associates with pro-caspase-8 and prevents caspase-8-mediated apoptosis (Zhao et al., 2017). Furthermore, activated RIPK3 triggers formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, depolarizing mitochondria (Zhao et al., 2017). The third pathway is based on connection of the cytosolic and mitochondrial NAD+ pools. Hence, NAD+ depletion in the cytoplasm directly decreases the NAD+ concentration in mitochondria (Cambronne et al., 2016), compromising electron transport chain function and reducing the proton gradient across the inner membrane (Stein and Imai, 2012). The concomitant loss of mitochondrial membrane potential impairs ATP production. Although pathways 1 and 2 are part of the necroptotic death program triggered by activation of RIPK3 (Vanden Berghe et al., 2014), indirect depletion of mitochondrial NAD+ by TNT probably contributes to the rapid demise of mitochondria and the inability of macrophages to mount an effective response to infection by Mtb. All of these observations explain the previously observed importance of phagosomal per-meabilization for the cytotoxicity of Mtb in infected macrophages (Simeone et al., 2012, 2016).

Figure 6. Mechanism of TNT-Mediated Cell Death of Macrophages Infected with Mtb.

After phagocytosis by macrophages, Mtb permeabilizes the phagosomal membrane, enabling TNT to translocate to the cytosol. The enzymatic activity of TNT hydrolyzes cellular NAD+ to nicotinamide (NAM) and ADP-ribose (ADPr). Depletion of the cytosolic NAD+ pool induces three major molecular events. RIPK63 senses lower NAD+ levels and/or increased levels of its degradation products and phosphorylates MLKL (pathway 1), which then forms oligomeric pores in host cell membranes and induces necrotic death (Wang et al., 2014). RIPK3 also migrates, together with Bcl-XL, to mitochondria (pathway 2), prevents caspase-8 activation, and induces formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore, depolarizing mitochondria (Zhao et al., 2017). The third pathway is a consequence of the connection of the cytosolic and mitochondrial NAD+ pools, as shown previously (Cambronne et al., 2016). Depleting cytosolic NAD+ also strongly reduces NAD+ levels in mitochondria, compromising the electron transport chain (ETC) and ATP synthesis. Dashed lines indicate unknown molecular mechanisms.

Importantly, our study shows that NAD+ depletion, whether it is by the glycohydrolase activity of TNT or by blocking NAD+ synthesis, is sufficient to activate RIPK3/MLKL-dependent necroptosis in THP-1 macrophages and Jurkat T cells. Interestingly, macrophages tolerated a much larger reduction of NAD+ concentration of up to 70% without any effect on cell viability compared with T cells, although the overall amount of NAD+ in both cell types was similar (930–960 attomole [amol] per cell). This might be a cell-specific difference or due to the different methods of NAD+ depletion. Interestingly, our results indicate that necroptosis is induced when the NAD+ concentration drops below a critical threshold of ~200 amol NAD+ per cell. It would be important to examine whether low NAD+ levels induce necroptosis in different primary human cells and what the critical NAD+ threshold in these cells is compared with the immortalized cell lines used in our study. However, several studies show a connection between low NAD+ levels and necrosis-like cell death, indicating that lack of NAD+ might be an evolutionarily conserved trigger of necroptosis. For example, the NAD+ glycohydrolase SPN of Streptococcus pyogenes depletes cellular NAD+ and induces necrosis (Chandrasekaran and Caparon, 2015). Similarly, PARP-1 hyper-activation rapidly depletes cellular NAD+, leading to ATP depletion and necrotic cell death, which has previously been interpreted as ‘‘energy collapse’’ (Herceg and Wang, 2001). Our findings suggest that the necrosis observed in the presence of SPN and activation of PARP-1 may be mediated by RIPK3 and MLKL as a result of NAD+ depletion and subsequent initiation of necroptosis.

One of the main questions raised by our study is how RIPK3 is activated by NAD+ depletion (Figure 6). It has been shown that proteins from the Bcl-2 family, such as Bcl-xL, are regulated by sirtuins, NAD+-consuming enzymes whose activity depends on NAD+ (Chang and Guarente, 2014), suggesting a mechanism by which NAD+ depletion could mediate Bcl-xL-dependent recruitment of RIPK3 to mitochondria. NAD+ depletion by TNT may also directly influence sirtuin-dependent processes. For instance, SIRT1 has been shown to induce phagosome-lysosome fusion and decrease Mtb intracellular growth in macrophages (Cheng et al., 2017). Another mechanism of how NAD+ could activate RIPK3 is by increased intracellular calcium concentrations through activation of the TRPM2 calcium channel by elevated ADP-ribose levels after NAD+ hydrolysis (Perraud et al., 2001). This hypothesis is supported by the observation that calcium influx by bacterial pore-forming toxins triggers necroptosis (González-Juarbe et al., 2015, 2017). Further experiments are needed to identify the molecular mechanism(s) that activate(s) RIPK3 when the cellular NAD+ level drops below a critical threshold.

Conclusions

The finding that NAD+ depletion triggers programmed cell death to kill macrophages infected with Mtb reveals strategies for host-targeted approaches to treat tuberculosis (TB). For example, Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs such as ponatinib and pazopanib have been shown to inhibit necroptosis (Fauster et al., 2015) and could, perhaps, be used to prevent necrosis and reduce dissemination of Mtb. Alternatively, NAD+ replenishment strategies could counter the toxicity of TNT and protect macrophages from cell death. Indeed, nicotinamide treatment increases NAD+ levels and survival of macrophages infected with Mtb, consistent with previous observations (Sun et al., 2015). NAD+ replenishment could be combined with reagents that promote mitochondrial function, such as RSV and CsA, which were previously shown to protect macrophages from Mtb-induced cell death (Cheng et al., 2017; Gan et al., 2005). These host-targeted strategies could be combined with antibacterial drugs to improve TB chemotherapy (Kaufmann et al., 2018; Nathan and Barry, 2015). These implications may also apply to other bacterial and fungal pathogens that utilize NAD+ glycohydrolases, such as S. pyogenes (Chandrasekaran and Caparon, 2015) and the over 300 microorganisms encoding TNT homologs (Danilchanka et al., 2014). Perhaps even more importantly, the role of RIPK3 as a cellular energy sensor may play a role in other diseases in which NAD+ deficiency is a common pathological factor, such as type 2 diabetes and a variety of neurological and heart diseases (Elhassan et al., 2017; Verdin, 2015; Zhang and Ying, 2018).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Ethics Statement

All experiments involving mice were performed following protocol 20270, approved by the University of Alabama Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and in agreement with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice(male and female, 6–8weekold, age-matched) were kindly provided by Dr. Carlos Orihuela (University of Alabama at Birmingham).

Infection of Macrophages

Mtb strains were harvested in mid-log phase (optical density 600 [OD600] of 0.6). Macrophages were infected with the Mtb strains at an MOI of 10:1 for 4 hr. Macrophage monolayers were incubated with medium containing 20 μg/mL gentamycin for 1 hr to kill extracellular bacteria and then kept in medium without antibiotics. When macrophages required pretreatment, the chemicals were added to the medium 1 hr before the infection and were kept in medium for the rest of the experiment. In all the experiments, both floating and attached macrophages were considered for analysis.

In Vitro NAD+ Glycohydrolase Assays and NAD+ Content in Mtb-Infected Macrophages

The NAD+ glycohydrolase activity of TNTwt and TNTH792N Q822K was measured by incubating 100 ng of protein with 1 μM β-NAD+ for 30 min at 370C in reaction buffer (20 mM Tris and 200 mM NaCl [pH 7.4]). The remaining NAD+ was quantified with the EnzyFluo NAD/NADH Assay Kit (Bioassay Systems). To measure the NAD+ content in Mtb-infected THP-1 cells, macrophages were infected with Mtb strains at an MOI of 10:1 for 48 hr and lysed with 0.025% SDS to release all NAD+ from the macrophages without lysing mycobacteria. The EnzyFluo NAD/NADH Kit was then used to quantify the amount of NAD+ in each sample.

Statistical Analysis

SigmaPlot (Systat Software) was used for graph development and statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments; p values were calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s correction, and p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The NAD+ glycohydrolase TNT triggers necroptosis in macrophages infected by Mtb

NAD+ depletion below a critical threshold is sufficient to induce necroptosis

NAD+ replenishment protects cells from necroptosis and alleviates Mtb cytotoxicity

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI114800 and AG055144 (to C.J.O.) and AI121354 (to M.N.).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, five figures, and one table and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.042.

REFERENCES

- Andreu N, Phelan J, de Sessions PF, Cliff JM, Clark TG, and Hibberd ML (2017). Primary macrophages and J774 cells respond differently to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci. Rep 7, 42225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar SM, Divangahi M, and Remold HG (2010). Evasion of innate immunity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: is death an exit strategy? Nat. Rev. Microbiol 8, 668–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar SM, Martin CJ, Booty MG, Nishimura T, Zhao X, Gan HX, Divangahi M, and Remold HG (2011). Apoptosis is an innate defense function of macrophages against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunol. 4, 279–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler RE, Krishnan N, Garcia-Jimenez W, Francis R, Martyn A, Mendum T, Felemban S, Locker N, Salguero FJ, Robertson B, and Stewart GR (2017). Susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected host cells to phospho-MLKL driven necroptosis is dependent on cell type and presence of TNFα. Virulence 8, 1820–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadieux N, Parra M, Cohen H, Maric D, Morris SL, and Brennan MJ (2011). Induction of cell death after localization to the host cell mitochondria by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis PE_PGRS33 protein. Microbiology 157, 793–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambronne XA, Stewart ML, Kim D, Jones-Brunette AM, Morgan RK, Farrens DL, Cohen MS, and Goodman RH (2016). Biosensor reveals multiple sources for mitochondrial NAD+. Science 352, 1474–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti YV, Brelaz MC, Neves JK, Ferraz JC, and Pereira VR (2012). Role of TNF-Alpha, IFN-Gamma, and IL-10 in the Development of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Pulm. Med 2012, 745483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran S, and Caparon MG (2015). The Streptococcus pyogenes NAD(+) glycohydrolase modulates epithelial cell PARylation and HMGB1 release. Cell. Microbiol 17, 1376–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, and Guarente L (2014). SIRT1 and other sirtuins in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 25, 138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Gan H, and Remold HG (2006). A mechanism of virulence: virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv, but not attenuated H37Ra, causes significant mitochondrial inner membrane disruption in macrophages leading to necrosis. J. Immunol 176, 3707–3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CY, Gutierrez NM, Marzuki MB, Lu X, Foreman TW, Paleja B, Lee B, Balachander A, Chen J, Tsenova L, et al. (2017). Host sirtuin 1 regulates mycobacterial immunopathogenesis and represents a therapeutic target against tuberculosis. Sci. Immunol 2, eaaj1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M, and Chan FK (2009). Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137, 1112–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilchanka O, Sun J, Pavlenok M, Maueröder C, Speer A, Siroy A, Marrero J, Trujillo C, Mayhew DL, Doornbos KS, et al. (2014). An outer membrane channel protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with exotoxin activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6750–6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danke C, Grünz X, Wittmann J, Schmidt A, Agha-Mohammadi S, Kutsch O, Jäck HM, Hillen W, and Berens C (2010). Adjusting transgene expression levels in lymphocytes with a set of inducible promoters. J. Gene Med 12, 501–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almagro MC, and Vucic D (2015). Necroptosis: Pathway diversity and characteristics. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 39, 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondelinger Y, Hulpiau P, Saeys Y, Bertrand MJM, and Vandenabeele P (2016). An evolutionary perspective on the necroptotic pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorhoi A, Nouailles G, Jörg S, Hagens K, Heinemann E, Pradl L, Oberbeck-Müller D, Duque-Correa MA, Reece ST, Ruland J, et al. (2012). Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is uncoupled from susceptibility to active tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol 42, 374–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Gan H, Golan DE, and Remold HG (2002). Critical role of mitochondrial damage in determining outcome of macrophage infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol 169, 5181–5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhassan YS, Philp AA, and Lavery GG (2017). Targeting NAD+ in Metabolic Disease: New Insights Into an Old Molecule. J. Endocr. Soc 1, 816–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauster A, Rebsamen M, Huber KV, Bigenzahn JW, Stukalov A, Lardeau CH, Scorzoni S, Bruckner M, Gridling M, Parapatics K, et al. (2015). A cellular screen identifies ponatinib and pazopanib as inhibitors of necroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquerel E, Goellner EM, Yu Z, Gagné JP, Barbi de Moura M, Feinstein T, Wheeler D, Redpath P, Li J, Romero G, et al. (2014). ARTD1/PARP1 negatively regulates glycolysis by inhibiting hexokinase 1 independent of NAD+ depletion. Cell Rep. 8, 1819–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan H, He X, Duan L, Mirabile-Levens E, Kornfeld H, and Remold HG (2005). Enhancement of antimycobacterial activity of macrophages by stabilization of inner mitochondrial membrane potential. J. Infect. Dis 191, 1292–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Juarbe N, Gilley RP, Hinojosa CA, Bradley KM, Kamei A, Gao G, Dube PH, Bergman MA, and Orihuela CJ (2015). Pore-Forming Toxins Induce Macrophage Necroptosis during Acute Bacterial Pneumonia. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Juarbe N, Bradley KM, Shenoy AT, Gilley RP, Reyes LF, Hinojosa CA, Restrepo MI, Dube PH, Bergman MA, and Orihuela CJ (2017). Pore-forming toxin-mediated ion dysregulation leads to death receptor-independent necroptosis of lung epithelial cells during bacterial pneumonia. Cell Death Differ. 24, 917–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbauer AB, Zahedi RP, Sickmann A, Pfanner N, and Meisinger C (2014). The protein import machinery of mitochondria-a regulatory hub in metabolism, stress, and disease. Cell Metab. 19, 357–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasmann M, and Schemainda I (2003). FK866, a highly specific noncompetitive inhibitor of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, represents a novel mechanism for induction of tumor cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 63, 7436–7442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herceg Z, and Wang ZQ (2001). Functions of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in DNA repair, genomic integrity and cell death. Mutat. Res 477, 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamwal S, Midha MK, Verma HN, Basu A, Rao KV, and Manivel V (2013). Characterizing virulence-specific perturbations in the mitochondrial function of macrophages infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci. Rep 3, 1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Sridharan H, Huang C, Mandal P, Upton JW, Gough PJ, Sehon CA, Marquis RW, Bertin J, and Mocarski ES (2013). Toll-like receptor 3-mediated necrosis via TRIF, RIP3, and MLKL. J. Biol. Chem 288, 31268–31279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann SHE, Dorhoi A, Hotchkiss RS, and Bartenschlager R (2018). Host-directed therapies for bacterial and viral infections. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 17, 35–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Remold HG, Ieong MH, and Kornfeld H (2006). Macrophage apoptosis in response to high intracellular burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by a novel caspase-independent pathway. J. Immunol 176, 4267–4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner TR, Borel S, Greenwood DJ, Repnik U, Russell MR, Herbst S, Jones ML, Collinson LM, Griffiths G, and Gutierrez MG (2017). Mycobacterium tuberculosis replicates within necrotic human macrophages. J. Cell Biol 216, 583–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Li W, Xiang X, and Xie J (2015). Mycobacterium tuberculosis effectors interfering host apoptosis signaling. Apoptosis 20, 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanillo PS, Shiloh MU, Portnoy DA, and Cox JS (2012). Mycobacterium tuberculosis activates the DNA-dependent cytosolic surveillance pathway within macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 11, 469–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Coronel E, and Castañón-Arreola M (2016). Comparative evaluation of in vitro human macrophage models for mycobacterial infection study. Pathog. Dis 74, ftw052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menear KA, Adcock C, Boulter R, Cockcroft XL, Copsey L, Cranston A, Dillon KJ, Drzewiecki J, Garman S, Gomez S, et al. (2008). 4-[3-(4-cyclo-propanecarbonylpiperazine-1-carbonyl)-4-fluorobenzyl]-2H-phthalazin-1-one: a novel bioavailable inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. J. Med. Chem 51, 6581–6591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraco AH, and Kornfeld H (2014). Cell death and autophagy in tuberculosis. Semin. Immunol 26, 497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales J, Li L, Fattah FJ, Dong Y, Bey EA, Patel M, Gao J, and Boothman DA (2014). Review of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mechanisms of action and rationale for targeting in cancer and other diseases. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr 24, 15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Altamirano MM, Paredes-González IS, Espitia C, Santiago-Maldonado M, Hernández-Pando R, and Sánchez-García FJ (2012). Bio-informatic identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins likely to target host cell mitochondria: virulence factors? Microb. Inform. Exp 2, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C, and Barry CE 3rd. (2015). TB drug development: immunology at the table. Immunol. Rev 264, 308–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K, and Manning G (2016). Necroptosis and Inflammation. Annu. Rev. Biochem 85, 743–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M, Robertson JD, Gogvadze V, Zhivotovsky B, and Orrenius S (2002). Cytochrome c release from mitochondria proceeds by a two-step process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1259–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perraud AL, Fleig A, Dunn CA, Bagley LA, Launay P, Schmitz C, Stokes AJ, Zhu Q, Bessman MJ, Penner R, et al. (2001). ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature 411, 595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repasy T, Lee J, Marino S, Martinez N, Kirschner DE, Hendricks G, Baker S, Wilson AA, Kotton DN, and Kornfeld H (2013). Intracellular bacillary burden reflects a burst size for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riendeau CJ, and Kornfeld H (2003). THP-1 cell apoptosis in response to Mycobacterial infection. Infect. Immun 71, 254–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca FJ, and Ramakrishnan L (2013). TNF dually mediates resistance and susceptibility to mycobacteria via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell 153, 521–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson SL, Dascher CC, Sambandamurthy VK, Russell RG, Jacobs WR Jr., Bloom BR, and Hondalus MK (2004). Protection elicited by a double leucine and pantothenate auxotroph of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in guinea pigs. Infect. Immun 72, 3031–3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone R, Bobard A, Lippmann J, Bitter W, Majlessi L, Brosch R, and Enninga J (2012). Phagosomal rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis results in toxicity and host cell death. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone R, Majlessi L, Enninga J, and Brosch R (2016). Perspectives on mycobacterial vacuole-to-cytosol translocation: the importance of cytosolic access. Cell. Microbiol 18, 1070–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn H, Kim JS, Shin SJ, Kim K, Won CJ, Kim WS, Min KN, Choi HG, Lee JC, Park JK, and Kim HJ (2011). Targeting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis heparin-binding hemagglutinin to mitochondria in macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LR, and Imai S (2012). The dynamic regulation of NAD metabolism in mitochondria. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 23, 420–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutz MD, Ojaimi S, Allison C, Preston S, Arandjelovic P, Hildebrand JM, Sandow JJ, Webb AI, Silke J, Alexander WS, and Pellegrini M (2018). Necroptotic signaling is primed in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages, but its pathophysiological consequence in disease is restricted. Cell Death Differ. 25, 951–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Wang X, Lau A, Liao TY, Bucci C, and Hmama Z (2010). Mycobacterial nucleoside diphosphate kinase blocks phagosome maturation in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. PLoS ONE 5, e8769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X, and Wang X (2012). Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148, 213–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Siroy A, Lokareddy RK, Speer A, Doornbos KS, Cingolani G, and Niederweis M (2015). The tuberculosis necrotizing toxin kills macrophages by hydrolyzing NAD. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 22, 672–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, and Vandenabeele P (2014). Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15, 135–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdin E (2015). NAD+ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science 350, 1208–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang LF, Wang FS, and Wang X (2014). Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol. Cell 54, 133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinlich R, Oberst A, Beere HM, and Green DR (2017). Necroptosis in development, inflammation and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18, 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welin A, Eklund D, Stendahl O, and Lerm M (2011). Human macrophages infected with a high burden of ESAT-6-expressing M. tuberculosis undergo caspase-1- and cathepsin B-independent necrosis. PLoS ONE 6, e20302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2017). Global Tuberculosis Report. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/.

- Wong D, Bach H, Sun J, Hmama Z, and Av-Gay Y (2011). Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase (PtpA) excludes host vacuolar-H+-ATPase to inhibit phagosome acidification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19371–19376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying W (2008). NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in cellular functions and cell death: regulation and biological consequences. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 179–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Najafov A, and Py BF (2016). Roles of Caspases in Necrotic Cell Death. Cell 167, 1693–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, and Ying W (2018). NAD+ Deficiency Is a Common Central Pathological Factor of a Number of Diseases and Aging: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. Published online February 7, 2018 10.1089/ars.2017.7445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Khan N, Gan H, Tzelepis F, Nishimura T, Park SY, Divangahi M, and Remold HG (2017). Bcl-xL mediates RIPK3-dependent necrosis in M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 1553–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong WX, and Thompson CB (2006). Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev. 20, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.