Abstract

Relying upon a content analysis of 1 specific type of medium to which young people are exposed beginning at an early age, on a regular basis, and for many years (i.e., animated cartoons), the present study examines what types of messages are provided about being members of different racial groups. This research examines the following issues: (a) How prevalent are race-related content and overt acts of racism in animated cartoons? (b) Has this prevalence changed over time? (c) What “types” of characteristics tend to be associated with being Caucasian, African American, Latino, Native American, and Asian? Results indicate that the prevalence of racial minority groups has been low over the years, with gradual decreases in representation during recent years, when the American population of racial minorities has grown. As time has gone on, the presence of overt racism has decreased greatly, demonstrating particularly sharp declines in the years since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. On most dimensions studied, members of different races were portrayed similarly.

Keywords: animated cartoons, media content, race, racism, portrayals, messages

For more than five decades, media content has been a “hot button” social issue, with many critics contending that exposure to the media leads to a variety of problems, including increased aggression and violence (Hess, Hess, & Hess, 1999; Mares & Woodard, 2005), the development of stereotyped beliefs and attitudes (Donlon, Ashman, & Levy, 2005; Lavin & Cash, 2001; Ward, 2002), and the development of eating disorders (Stice, 1998, 2002; Thomsen, McCoy, & Williams, 2001), among other adverse outcomes. One topic that has received periodic attention over the years is how the media portray members of different racial groups. Generally speaking, studies focusing on race-related content in the media have concluded that racial minority group members are underrepresented in the media (Eschholz, Bufkin, & Long, 2002; Glascock & Preston-Schreck, 2004; Larson, 2002), regardless of whether these persons=characters are African American (Jackson & Ervin, 1991), Latino (Harwood & Anderson, 2002; Li-Vollmer, 2002; Taylor, Lee, & Stern, 1995), Asian (Greenberg, Mastro, & Brand, 2002; Li-Vollmer, 2002; Mastro & Stern, 2003), or Native American (Greenberg et al., 2002; Li-Vollmer, 2002; Mastro & Stern, 2003; Merskin, 1998). Moreover, persons of color tend to be marginalized when they are shown, often occupying minor roles rather than major roles, particularly when compared to their Caucasian counterparts (Bang & Reece, 2003; Greenberg, Mastro, & Brand, 2002; Li-Vollmer, 2002; Taylor & Stern, 1997).

In addition to being underrepresented in the media, most researchers have pointed out that, when racial minority group members are included in the media, they are often portrayed in negative and stereotypical ways. Examples abound but providing a few illustrations can be helpful to elucidate the myriad ways in which racial minorities are portrayed negatively in various types of mass media. With respect to African Americans in the media, Rada and Wulfemeyer (2005) and Billings (2004) reported that, based on their analyses of television coverage of sports events, announcers promote negative images of African American athletes. Similar findings were reported by Hardin and colleagues (2004) in their analysis of newspaper coverage of Olympic sporting events, claiming that the way that African Americans were depicted reinforced hegemonic notions of primitive athleticism among African Americans. In their study of television commercial content, Coltraine and Messineo (2000) concluded that the main message provided about African American males is that they were aggressive and the main message provided about African American females is that they were inconsequential. They concluded that television commercials contribute to the perpetuation of prejudice against African Americans by exaggerating cultural differences. Taylor, Lee, and Stern (1995), based on their research on magazine advertising content, also concluded that the ways in which African Americans were portrayed in that medium were sufficiently stereotyped as to raise societal concerns about discrimination and prejudice. Based on their review of the content analysis literature pertaining to African Americans in the media, Greenberg, Mastro, and Brand (2002, p. 336) concluded “although ... Blacks [in more recent years] have achieved equivalence with regard to the number of roles, the quality and variety remain debatable,” with stereotypes and negative images still typifying portrayals of members of this group.

With regard to Asians in the media, Taylor, Lee, and Stern (1995) magazine advertising research showed that Asian Americans were portrayed as being work-oriented (i.e., “all work and no play”). In a counterpart study examining television advertising, Taylor and Stern (1997) also found that Asian Americans were portrayed disproportionately often in business settings, and underrepresented in settings involving family, friends, and social relationships. Based on her analysis of television and movie content, Mok (1998) concluded that Asian characters are not shown to be as diverse as Asian persons are in real life, and that these particular media tend to emphasize specific beauty standards for Asian Americans. Some researchers have described media portrayals of Asians as representing that of a “model minority”—that is, hard working, efficient, attractive, technologically savvy, well-educated, and so forth (Mastro & Stern, 2003; Paek & Shah, 2003; Taylor & Stern, 1997). Although this type of portrayal is not negative per se, it is nonetheless based on social stereotypes of Asian Americans and its presence in the media does promulgate the continued existence of this type of racial stereotyping.

Based on their research on the content of prime-time television programs, Harwood and Anderson (2002) concluded that Latino characters were portrayed less positively than others when it came to such matters as physical attractiveness, quality of dress, personality characteristics, and their importance to storylines. Greenberg (1982) found that Latinos were almost never portrayed as working professionals when they were shown on television, and Mastro and Stern (2003) reported that so few of the prime-time television commercial characters they studied were Latino that they could not be included in their statistical analysis of racial differences in occupational status. Dixon and Linz (2000) reported that, on television news programs, Latinos were more likely than Caucasians to be shown as lawbreakers. Based on a study of popular films, Berg (1990) concluded that Latino characters tended to be shown in any of six stereotyped ways: “El Bandito” (i.e., the Mexican bandit), the half-breed harlot, a male buffoon, a female clown, a Latin lover, or as a “dark lady.” A review of the 1999–2001 television programming seasons revealed that the Latino population is six times greater in the United States than it is on American television, and that the few Latino characters who are shown tend to be affiliated in some way with the criminal justice system Children Now, 2001; Greenberg, Mastro, and Brand (2002, p. 336). The most recent update of this information (Children Now, 2004) has shown a small increase in the prevalence of Latino characters but no improvement in the quality of the portrayals of Latino characters.

Such stereotyping and negative depictions of persons of color are of concern because they present people with repeated messages about what it means to be a member of the cultural=racial majority versus a member of a racial minority group, and with unhealthy notions of what one should or should not look like. Over the years, a substantial body of literature has accumulated to demonstrate that exposure to the media has a profound impact upon people’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (see, e.g., Paik & Comstock, 1994; Shrum, Wyler, & O’Guinn, 1998). There also appears to be a doseresponse effect operating, such that people who have more exposure to the media are more affected by what they see, hear, and read than their peers who are exposed less significantly to media messages (Shrum, Wyler & O’Guinn, 1998; Singer et al., 1998).

Conceptually, this makes perfect sense and there is a substantial body of theoretical work in the sociological, psychological, and media studies fields to account for—and to anticipate the presence of—these types of effects. For example, social learning theory (Akers, 1973; Bandura, 1971) posits that people acquire their beliefs, attitudes, and propensity to engage in behaviors directly based on first-hand experiences they have with others who exhibit particular behaviors and/or indirectly, based on what they observe others—including others appearing in the mass media—doing or saying. As Kunkel et al. (1996, p. I6) put it, “through the observation of mass media models the observer comes to learn which behaviors are ‘appropriate’—that is, which behaviors will later be rewarded, and which will be punished.” Accordingly, social learning theory would predict that people of all ages (and young people in particular) will learn a great deal about race, social expectations for what is a “proper” way for Caucasians or African Americans or Latinos or Asians to act, and the social consequences of being a person of color just from being exposed to race-related media content.

As another example, cultivation theory (Gerbner & Gross, 1976; Signorielli & Morgan, 1990) states that media viewers’ perceptions of social reality will be shaped by extensive and cumulative exposure to media-provided messages. This theoretical model assumes that people develop beliefs, attitudes, and expectations about the real world based on what they see and hear on television, on video, in film, in magazines, and so on. Subsequently, they use the beliefs, attitudes, and expectations they have developed to make decisions about how they will behave in real-world settings and situations. Again, Kunkel et al. (1996, p. I11, I13) put it well when they stated, “The media, in particular television, communicate facts, norms, and values about our social world. For many people television is the main source of information about critical aspects of their social environment ... Whether television shapes or merely maintains beliefs about the world is not as important as its role in a dynamic process that leads to enduring and stable assumptions about the world.” In the context of the study of race-related media content, then, cultivation theory would posit that media messages serve as agents of socialization regarding what to think about Caucasians versus racial minority group members. This would be particularly true for young viewers who are exposed rather heavily to such media messages through the types of programming that they tend to view. Given the types of messages that the media provide about race, cultivation theory would predict that the cumulative effect of exposure to these messages would provide young people with beliefs and attitudes that, ostensibly, reinforce social stereotypes that differentiate members of different racial groups, that there are numerous ways in which it is better or preferable socially to be Caucasian than African American or Latino or a member of another racial minority group, that there will be social consequences to pay if one’s race is different from the media-promulgated standards of “good” Caucasian characteristics, and so forth.

Taking these theoretical models’ tenets and the aforementioned research studies on media effects to heart, the present study entails an examination of race-related messages in a medium that, we contend, is likely to provide young people with some of their earliest notions regarding race-related standards/expectations: animated cartoons. We have chosen animated cartoons as the focal point of this research for a few reasons. First, people are exposed to this type of medium beginning at an early age. Therefore, race-related messages provided by this particular medium are likely to be influential in the initial stages of developing beliefs and attitudes about different racial groups. Second, for most young people, this exposure continues for many years, and typically entails repeated and frequent media content exposures during that entire viewing period. Thus, animated cartoons also help to crystallize young people’s race-related beliefs and attitudes, while helping to shape relevant behaviors through the repeated and consistent race-related messages they provide. Research has shown that early-life exposure to media messages does, indeed, affect the formation of attitudes and contributes to the crystallization of notions about a variety of aspects of young viewers’ social worlds (Greenberg, 1982; Tiggemann & Pickering, 1996).

In this study, we address three principal research questions. First, how prevalent is race-related content in animated cartoons? Second, has this prevalence changed over time? Third, what “types” of characteristics tend to be associated with being Caucasian versus being African American, Latino, Native American, or Asian? We conclude by discussing the implications of our findings and elaborating briefly upon some steps that might be taken in the future to provide viewers with what we consider to be more-positive, less-stereotyped race-related messages.

This study contributes to the scientific literature in several ways. First, the research is based on a scientific random sample, rather than on a convenience sample. This random sampling approach facilitates generalizability of findings, whereas this is considerably more difficult when a convenience sample is used. Second, the present study examines portrayals spanning several decades, thereby offering readers an opportunity to understand how race- and racism-related messages have changed over time. This is an advantage that very few previously published studies can offer. Third, this study is based on a large sample (1,221 cartoons and 4,201 major characters in those cartoons) which enables point estimates to be derived and analytical comparisons to be made with adequate (typically, far more than adequate) statistical power. Fourth, this research examines and compares the portrayals of several different racial groups—namely, Caucasians, African Americans, Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans—rather than focusing merely on one or two of these groups, as many previous content analysis studies have done.

METHODS

Sampling Strategy

This study is based on an examination of the content of animated cartoons. For the present study, only animated cel cartoons are included in the sample (e.g., Bugs Bunny, Popeye, Mighty Mouse, Yogi Bear). This eliminates from the present study such types of animation as claymation (e.g., Gumby and Pokey, the California Raisins), pixillation (the type of animation usually seen at the end of The Benny Hill Show), and puppet animation (e.g., Davey and Goliath, George Pal’s Puppetoons).

The cartoons chosen for the study sample were selected randomly from among all cartoons produced between the years 1930 and the mid-1990s by all of the major animation studios. Before drawing the final sample of cartoons that would be viewed and coded for this work, the researchers had to develop a comprehensive and inclusive sample frame of cartoons produced by the aforementioned animation studios. Published filmographies (Lenberg, 1991; Maltin, 1980) provided the authors with a great deal of this information, and in some instances, the animation studios themselves were contacted and asked to provide comprehensive episode-by-episode lists of animated cartoons they had produced. Once the “universe” of cartoons had been identified, actual copies of the specific cartoons selected for viewing and coding as part of the random sampling approach had to be located. This was done in a wide variety of ways: by contacting animation fans and collectors and having them make copies of some of their cartoons for us, visiting film archives and repositories and viewing cartoons in their libraries/holdings on site, obtaining copies of the needed cartoons directly from the animation studios, purchasing sample-selected items from retail outlets and private sellers who advertised them in trade publications, renting videocassettes from retail outlets like Blockbuster Video, and videotaping from programs broadcast on television.

The origination date for this research (1930) was chosen for four reasons: (a) many major animation studios had begun operations by that time, (b) the era of silent cartoons had virtually ended, (c) cartoons produced prior to 1930 are not very accessible today, and (d) many cartoons produced during the 1930s are still broadcast on television and/or available for viewing on home video. Because of the fiscal constraints of the funding program, only animated cartoons with a total running time of 20 minutes or less were included in the sample frame.

A stratified (by decade of production) random sampling procedure was used to ensure that cartoons from all decades were represented equally in the study sample. This stratification procedure was necessary because very different numbers of cartoons have been produced during different decades (e.g., many more were produced during the 1980 s than during the 1930s), thereby leading to the risk that a general random sample (as differentiated from this study’s stratified random sample) might have led to an overrepresentation of certain decades during which greater- or lesser-than-average numbers of racial minority group characters were portrayed.

Data Collection

This study relied upon a content analysis approach to examine the types of messages that cartoons provide about racial group members. Data collection for this research entailed viewing the cartoons contained on the project’s sample list and recording detailed information on predesigned, pretested, pilot tested, fixed-format coding sheets. Prior to beginning their viewing and coding work for this study, research assistants underwent an intensive training that familiarized them with the data that the study strived to collect, the rationale underlying the coding of each piece of information, and the decision-making procedures that should be used when recording information from each cartoon. To make sure that all people involved in the viewing=coding (i.e., data collection) process implemented the decisionmaking procedures in a similar manner, intercoder reliability coefficients were calculated periodically throughout the project. Reliability estimates consistently were above .80 for all major measures and were at least .90 for all of the variables used in the analyses reported in this article, indicating a very high level of intercoder reliability for this research.

To understand the information that this study contains, it is best to conceptualize the database as consisting of two datasets. Dataset 1 focuses on the cartoon itself as the unit of analysis and contains macro-level variables that provide prevalence-type information. Among several others, this dataset includes such measures as the cartoon’s length; number of characters of each gender, race, age, body weight group, and so forth; number of times using or making reference to various legal and illegal drugs; and number of prosocial and antisocial acts committed. This dataset facilitates analyses indicating the proportion of cartoons containing at least one African American (or Latino or Asian or Native American or Caucasian) character, how these proportions changed over time, or identifying the rate of seeing characters of races per hour. The sample size for this dataset is 1,221.

Dataset 2 focuses on the major characters in each cartoon (regardless of whether they are human characters, animals, personified inanimate objects [e.g., cars with the ability to growl or dance, telephone poles given humanlike abilities to see or hear or sing], monsters, ghosts, etc.), providing detailed information that is of value when trying to interpret the types of messages that cartoons provide about who it is that is shown to be Caucasian or African American, etc. This dataset contains information about each major character’s gender, age, race, ethnicity, marital status, level of intelligence, attractiveness, body weight, physique, occupational status, level of goodness or badness, and other demographic-type and descriptive information. In addition, Dataset 2 contains data about the number of acts of violence, aggression, and prosocial behaviors (and limited information about the types of these behaviors involved) that the characters have committed. This dataset’s information is useful for examining such things as whether males/females or smart/dumb characters or attractive/unattractive characters are more likely to be Caucasian or a minority group member, whether characters of different racial groups engage in more activities, prosocial behaviors, antisocial behaviors, and so forth. The sample size for this dataset is 4,201.

Operational Definitions of Some Key Concepts

Perhaps the most important operational definition to provide for this study is that used for classifying characters’ race. In this research, every character’s race was classified either as Caucasian, African American, Latino, Asian, Native American, or as “race indeterminable/no race intended.” Coders were instructed that all human characters must be coded for their racial group. All other character types, such as animal characters, extraterrestrial creatures, and inanimate objects brought to life, were to be classified as “race indeterminable/no race intended” by default unless the cartoon provided specific, unmistakable reasons (based on the character’s appearance) to select one of the other racial group classifications. The benchmark that coders were instructed to use for classifying a nonhuman character as being something other than “race indeterminable/no race intended” was if “some racial comparison is made, if some racial reference is made, or if the character’s appearance is changed at some point during the cartoon to indicate a purported change in race.” Cartoons are rarely subtle in the messages they try/wish to convey; so using this type of coding rule was, in actuality, quite easy for coders to apply in a consistent manner to the classification of characters’ race. Not surprisingly, many of the cartoon characters studied were nonhumans whose race was considered to be “race indeterminable/no race intended,” leaving us with a sample size of 1,674 major characters with a codable, discernible race.

Another key concept for one part of the analysis is an overt act of racism. In this research, we defined an overt act of racism as “any portrayal of a character belonging to a racial minority group that is based on stereotypes of that character’s racial group’s behaviors or exaggerations of that character’s racial group’s physical traits. In order to be counted as an act of overt racism, the depiction must be a disparaging and/or unflattering one.” These instructions enabled African American characters shown to eat watermelons, Chinese characters working in a laundromat, Native Americans saying “How!” as a greeting to another character, and so forth automatically to be construed overt acts of racism. Moreover, coders were instructed to code something as being overtly racist “if the cartoon shows any character treating another character in a disparaging manner because of that character’s race.”

In this study, we collected detailed data (i.e., the information collected in Dataset 2) only for major characters, although some prevalence-related information pertaining to minor characters’ race was captured in Dataset 1. Therefore, we felt that it was important to distinguish between major and minor characters because the former have a much greater and much more consequential impact upon cartoons’ storylines and messages, whereas the latter do not. Consequently, we adopted operational definition criteria that would enable the two character types (i.e., major and minor) to be differentiated easily and in a meaningful way. Coders were instructed to follow these rules in order to determine whether a character was “major” or “minor”: First, all characters were supposed to be classified by default as minor, unless the conditions stipulated in one or more of the subsequent rules were met. Second, if a character appeared in an average of at least two camera cuts1 for each complete minute or additional partial minute2 of the cartoon’s running time, that was sufficient to label it a “major” character. For example, if a cartoon had a total running time of 8 minutes and 10 seconds, a character would have to appear at least 18 times (i.e., in 18 or more camera cuts [e.g., two per minute or partial minute of running time, multiplied by nine minutes/partial minutes increments]) throughout the duration of the cartoon in order to be considered “major” using this criterion. Third, a character could be considered “major” if it spoke an average two sentences or phrases counting as sentences3 per minute or partial minute of the cartoon’s total running time. Fourth, a character could be considered “major” if it had an average of three or more camera cuts in which it appeared and sentences or phrases counting as sentences per minute of the cartoon’s running time. This criterion was implemented to take into account that many consequential characters in the cartoons do not appear a lot and do not say a lot, but their cumulative visual and verbal presence in the cartoon merits “major” character status even though the two previous rules would have prevented such a designation from being made. Finally, a character could be considered “major” if it appeared on screen for at least 20% of the cartoon’s total running time, regardless of the number of camera cuts and sentences or phrases counting as sentences spoken. Generally speaking, although these rules may seem to be somewhat convoluted, determining whether a character was a major or minor one was an easy, straightforward, and relatively obvious process.

Analysis

Some of the findings reported are based on descriptive statistics, particularly where prevalence estimates are used, as was the case for addressing Research Question 1. Changes over time (Question 2) are examined using logistic regression when the dependent variable was dichotomous (e.g., whether or not a cartoon contained characters belonging to specific racial groups) and the predictor variable was a continuous measure. In addition, some changes over time are examined using simple regression when the dependent variable was continuous (e.g., percentage of characters belonging to a particular racial group) and the predictor variable was a continuous measure. Tests of curvilinearity were performed to determine whether observed changes were linear in nature or whether they demonstrated periods of significant upswing followed by periods of significant downswing (or viceversa). The analyses examining the characteristics associated with which “types” of characters (Question 3) were more=less likely than others to be Caucasian (or a member of another racial group) entailed the computation of odds ratios (ORs), with 95% confidence intervals (CI95) presented for each estimate. Odds ratios were selected for these analyses because they facilitated direct comparisons of the messages provided about characters of different races, whereas other statistical tests do not lend themselves so easily to such comparisons and interpretation. Because of the large sample size used in this research, results are reported as statistically significant whenever p < .01 and as marginally significant whenever p < .05.

RESULTS

Prevalence of Racial Minority Group Characters and Overt Racism

Approximately 1 cartoon in 6 (16.1%) contained at least one character that was a member of a racial minority group, whereas substantially more (69.9%) contained at least one character that was Caucasian. From the early 1930s until the later 1960s, the proportion of cartoons containing any non-White characters declined by approximately two thirds (from 16.6% to 4.4% of all cartoons, p < .002), after which it fairly steadily increased to its highest-ever proportion during the later 1980 s and into the 1990s (31.7% and 22.5%, respectively, p < .0004). In large part, these changes were due to the presence of minor (not major) characters, which increased substantially during recent decades (p < .0001). Similarly, from the early 1930s until the later 1960s, the proportion of all cartoon characters (i.e., major and minor characters combined) that were nonwhite steadily declined (p < .003), after which it increased steadily until the 1990s (p < .02). These changes were mirrored among major and minor characters alike (p < .0001 for both).

The prevalence patterns for different minority groups were not comparable. For example, Asian characters comprised a small percentage (1.7%) of the total population of characters with codable race. This frequency did not change over time (p < .47). Likewise, Latino characters constituted a similarly small proportion of all cartoon characters (2.4%), and that frequency did not change over time either (p < .56). Native American characters, who constituted 1.5% of the sample, became significantly less visible as time went on (p < .0002). Conversely, African Americans, who comprised the largest racial minority group in the study (3.1%), declined in prevalence from the early 1930s (when they constituted approximately 9% of the sample) until the 1960s (when they accounted for less than 0.1% of the sample; p < .002). After that time, there was a gradual yet significant increase in their presence until they comprised nearly 3% of the characters shown during the later 1980 s and 1990 s (p < .0001).

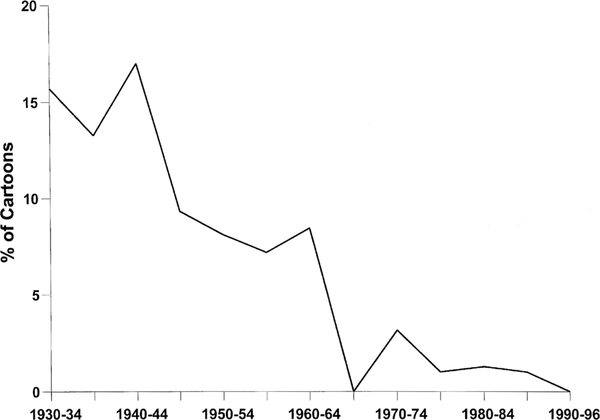

Overall, approximately 1 cartoon in 15 (6.6%) contained at least one act of overt racism. Among cartoons depicting at least one overtly racist act, the mean number of such acts was 3.8 (range = 1–29, SD = 5.1). Figure 1 presents the findings obtained for the prevalence of overt racism over the course of time. This figure shows that there has been a sharp and fairly steady decline in the presence of overtly racist portrayals in cartoons as time has passed (p < .0001).

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of overt racism over time (p < .0001).

Differences in How Various Racial Minorities Were Portrayed—Part 1: Descriptive Attributes

Few race-related differences were found based on demographic characteristics and other descriptive attributes among the cartoon characters studied, and those that were found did not form any type of consistent pattern. African Americans were twice as likely to be female as were non-African American characters (OR = 2.18, CI95 = 1.25–3.83, p < .006). With regard to age, one race-related difference was obtained: African American characters were more likely than those of other races to be shown as children or adolescents (OR = 2.25, CI95 = 1.30–3.89, p < .003). In terms of their physical attractiveness, only one race-related finding was observed: African Americans were somewhat more likely than characters of other races to be shown as attractive (OR = 2.39, CI95 = 1.15–4.97, p < .02). Caucasians were somewhat more likely than members of other races to have a job (OR = 1.69, CI95 = 1.13–2.54, p < .02), whereas Latinos were less likely than members of other races to be shown as having a job (OR = 0.23, CI95 = 0.07–0.77, p < .01). Among characters shown to have jobs, however, Caucasians were less likely than other racial groups to be shown to perform their jobs well (OR = 0.22, CI95 = 0.10–0.48, p < .0002) whereas employed African Americans were more likely than other groups to be depicted as being good at their jobs (OR = 6.89, CI95 = 1.92–24.72, p < .0006).

No differences were found among racial groups with respect to body weight, physique, intelligence, marital status, dressing up, or the presence of a physical disability.

Differences in How Various Racial Minorities Were Portrayed—Part 2: Emotional=Feeling States

By and large, characters of all racial groups were shown to experience the same emotions and feelings. No differences were found, for example, based on demonstrating happiness, feeling sadness, experiencing fatigue, being energetic, being loving, experiencing loneliness, being bored, or demonstrating shyness. African Americans were somewhat less likely than other groups to experience anger (OR = 0.55, CI95 = 0.32–0.92, p < .03). Latino characters were somewhat less likely than other racial groups to experience fear (OR = 0.42, CI95 = 0.19–0.93, p < .03).

Differences in How Various Racial Minorities Were Portrayed–Part 3: Activities, Prosocial Behaviors, and Antisocial Behaviors

Overall, African American characters were found to engage in nearly twice as many leisure-time activities as members of other races (t = 3.62, p < .0003). When individual activities items were compared, however, most did not show significant racial differences. This was true with respect to involvement in sports, driving a car, cooking, eating something, playing games, doing housework, doing home maintenance, caring for children, knitting, engaging in artistic/crafts activities, exercising, watching television or listening to the radio, gambling, shopping, reading, writing, engaging in personal care, taking care of a pet, or using any type of legal or illegal drug. The dimensions on which groups were found to differ significantly tended to pertain to entertainment-related measures. For example, African American characters were three times more likely than other racial groups to sing (OR = 3.29, CI95 = 1.66–6.52, p < .0003), more than twice as likely as others to dance (OR = 2.59, CI95 = 1.14–5.87, p < .02), and more than three times as likely as others to play music (OR = 3.30, CI95 = 1.44–7.55, p < .003). Caucasians were less likely than members of other racial groups to take vacations (OR = 0.33, CI95 = 0.15–0.73, p < .004) whereas African American characters were more than five times as likely as other characters to be shown on vacation (OR = 5.57, CI95 = 2.23–13.89, p < .0001).

We looked at several measures of prosocial behaviors, including providing physical assistance to another character, providing financial assistance to another character, offering knowledge or advice to another character, complimenting another character’s appearance or performance, showing concern for another character’s physical or emotional well-being, and an overall measure of involvement in prosocial acts. Compared with members of other races, African Americans were found to engage in a greater number of prosocial acts (t = 2.50, p < .02). This was particularly true for the provision of physical assistance to other characters, which was twice as great among African American characters compared with others (t = 2.79, p < .006). Latino characters were more likely to offer knowledge or advice than were characters of other races (t = 2.66, p < .008). No other racial differences were observed for prosocial behaviors.

Finally, we also examined several measures of antisocial behaviors, including lying to or deceiving other characters, verbal aggression (e.g., yelling, making threats), physical aggression, and violence. Overall, African American characters committed about half as many antisocial acts as characters of other races (t = 2.44, p < .02). This was particularly noticeable when acts of physical aggression were considered, with African American characters perpetrating about one third as many of these acts as characters of other races (t = 2.26, p < .03). No other race-based differences were observed with respect to the commission of antisocial behaviors.

DISCUSSION

Before discussing the implications of our main findings, we would like to acknowledge a few potential limitations of the present study. First, this research was based on animated cartoons with running times of 20 minutes or less, thereby excluding longer-form animated cartoons from consideration. We do not know whether or not short-form and long-form animated cartoons are similar to one another with respect to the types of messages they convey, and therefore cannot assess the extent to which the exclusion of the latter may affect this study’s findings. Conducting research such as ours with the longer cartoons would be a worthwhile endeavor for future researchers to undertake. Second, our sample ends during the middle-1990s. It would be helpful and, we believe, interesting to have this research extended to the present, so that the most up-to-date trends possible are studied and analyzed. Third, as with any content analysis research study, some scholars might prefer to see different operational definitions of the key concepts used. There is no “gold standard” in content analysis research with regard to defining major versus minor characters, overt racism, and so forth. The definitions that we adopted were chosen on the basis of common sense, so that they would foster face validity, and on the basis of simplicity and clarity of implementation, so that they would maximize interrater reliability. We believe that our operational definitions are well-conceptualized and justified; but as with any content analysis study, there is no way to know the extent to which the use of different definitions might have led to different research findings.

Despite these potential limitations, we still believe that the present research has much to contribute to our understanding of cartoons’ messages about race. First, as time has gone on, cartoons have provided fewer examples of characters that can be construed as being overtly racist. The decline in overt racism in animated cartoons began shortly after World War II, and reduced to near-zero levels in the years following the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960 s. It appears to us that, as public pressures increased in our society to treat members of racial minority groups with greater equality and to discriminate less against them, animated cartoon content followed suit by greatly reducing overtly racist portrayals. This finding is consistent with a few other recent studies, which have found that media portrayals of racial minority group members have improved over time (Bang & Reece, 2003; Eschholz, Bufkin, & Long, 2002; Towbin et al., 2003).

A second major finding of the present research is that, for the most part, African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asians, and Caucasians were portrayed relatively similarly on most dimensions. Unlike most previously published studies, which have been based principally on other types of media and which have reported strong stereotyping of racial minority group members by the media, our research does not reveal strong evidence to support this notion. True, we did discover that African Americans were more likely than members of other races to engage in entertainment-related activities like singing, dancing, and playing music—content which, we readily admit, is consistent with age-old stereotypes of Black minstrels and the notion of African Americans as entertainers of the dominant White culture.4 At the same time, however, we also discovered that African American characters were more prosocial and less antisocial than other characters—findings that, far from being negatiely stereotyping, are positive in nature. On most dimensions—including most of the demographic characteristics, most of the descriptor measures, almost all of the emotional states variables, and the large majority of the activities measures studied—no race-related differences were found. This may be due to the relatively small number of major characters comprising the various racial minority groups under study, or it may be due to the fact that animated cartoons, as a youth-oriented medium, traditionally have not provided widespread, patterned, stereotyped messages about African Americans, Latinos, Asians, Native Americans, or Caucasians. Having watched and coded more than 1,200 cartoons for this research, our abiding impression is that the latter explanation is more valid than the former, particularly when one considers cartoons’ overall messages rather than focusing on the negative content that predominated during the earlier years spanned in this research.

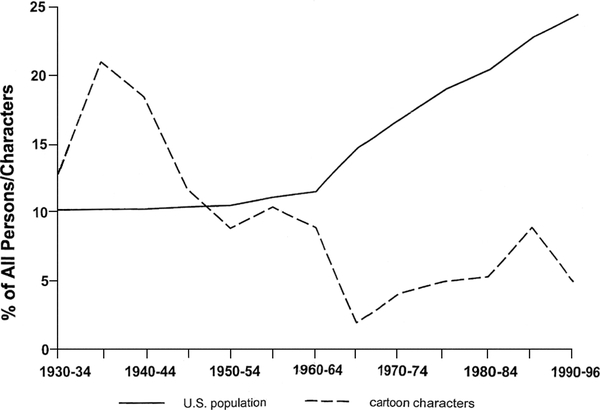

That having been said, however, we wish to point out that animated cartoons have a long history of underrepresenting racial minority groups. Figure 2 demonstrates this contention quite clearly. During the 1930 s and 1940 s, when minority representation in the United States was fairly low (comprising approximately 10% of the total population), animated cartoons included an abundance of minority characters, many of which were highly stereotyped in nature. Ever since then, however, as the population of non-Caucasians grew in the country, the population of non-Caucasians shrunk in the cartoon world. The gap has widened steadily over time, to the point where racial minority groups were underrepresented by nearly a margin of 5:1 during the most recent period studied. This underrepresentation was observed for all racial minority groups except Asians.5 African Americans, who comprised 11.8% of the U.S. population during the time period last covered by this research (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000), constituted only 3.3% of the animated cartoon characters at that time—underrepresented by nearly 4:1. Latinos, comprising 9.0% of the U.S. population, represented 1.2% of the characters shown during the 1990s—underrepresented by more than 7:1. Native Americans, who accounted for 0.72% of the U.S. population during the 1990 s, were only 0.04% of the cartoon characters shown at that time—underrepresented by an 18:1 margin.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of all persons=characters that are racial minorities.

The consistent pattern of failing to show certain types of socially devalued groups (what some sociologists call “out groups”), common among many forms of mass media, has been termed symbolic annihilation by some researchers (Kielwasser & Wolf, 19931994; Merskin, 1998; Ohye & Daniel, 1999). These researchers’ claim–and it is one with which we agree—is that, by presenting certain “types” of persons or characters at the expense of others, and by almost never showing certain “types” of persons or characters, the media not only reflect social values about the goodness/badness or preferability of some groups vis-a-vis others, but they also reinforce these notions in people who are exposed to these media. For example, if television viewers never or rarely witness a well-educated African American on television, or if viewers never or rarely see portrayals of gay characters that are not flamboyant, they may be left with the impression that such persons do not exist. By omitting characters reflecting the true diversity of our society, the media symbolically annihilate certain types of characters, thereby contributing to the persistence of stereotypes and people’s general lack of knowledge and sensitivity toward these types of people. In the context of the present study, then, our findings of significant underrepresentation of most racial minority groups suggest that animated cartoons are guilty of this type of symbolic annihilation. Much greater representation of African American characters and Latino characters and Native American characters is needed in order for viewers to construe these groups as valued and equal contributors to our culture. By showing so few of them, particularly compared with their Caucasian counterparts, animated cartoons send the message—loud and clear—that African Americans do not count, that Latinos do not count, and that Native Americans do not count ... at least not to the same extent that Caucasians do.

What Might Be Done Based on These Findings?

There are a number of things that might be done in an attempt to improve on the situation outlined above. First and foremost, studios producing new animated cartoons and the story-writers and producers of such cartoons could begin to include more racial minority group characters. Such characters could—and we contend, should—be shown realistically so that, just like their Caucasian counterparts, some of them are portrayed as attractive, intelligent, loving, happy, and positive even if others are not. More than anything else, what we are advocating here is a movement toward balanced messages regarding the relationship between personality characteristics, social values, and portrayals of race. Some African American (or Latino or Native American or Asian) persons are attractive; some are not. Some Caucasian persons are attractive; some are not. Likewise, the same can be said for how intelligent such persons are, how prosocial or antisocial they are, and so on. We believe that one excellent way to begin to improve cartoons’ content vis-a-vis race would be, quite simply, to provide a broad array of messages for characters of all types, rather than the relative absence of racial minority group characters that heretofore has typified animated cartoon storylines.

Providing counter-programming amidst televised animated cartoon episodes (or alongside such cartoons made available to consumers on home video and DVD) might also be an avenue worth exploring. One way that counter-programming could be implemented—one that we think might be worthwhile and cost-effective for the television and cable industries to consider—would be through the addition of interstitial segments in existing animated cartoon programs. Interstitials are small program segments, usually having running times ranging from 30 seconds to about 3 minutes, that can be inserted between cartoon episodes within a given program if the episodes are short enough or that can be inserted between programs during the commercial blocks that occur before and after scheduled programming is broadcast. As short-form segments, interstitials would be inexpensive to create, and their short running times would allow them to be added to a variety of children’s programs without requiring the broadcaster to edit these programs for time. The interstitials could be made so that they feature the same cartoon characters shown in the original (i.e., “problematic”) cartoons, but with short vignettes that are simultaneously entertaining, enlightening, prosocially oriented, and race-positive. One way to do this might be to create new animated cartoons or animated interstitials using the same characters shown in the original cartoons but have positive portrayals of racial minority group characters added alongside them. In this manner, the original, entertaining, but “minority absent” cartoons can remain intact and be broadcast intact while being combined with newer content that is designed to be equally entertaining but more prosocial in nature. Over the years, some studios (most notably Hanna-Barbera and Warner Brothers) and some television networks (most notably the American Broadcasting Company [ABC]) have implemented educational and=or prosocial interstitial segments into their animated cartoon programming, and these programs have been entertaining and positive in their content.6 We applaud these efforts. Moreover, some research has been conducted on the effects of counter-programming, generally showing at least some measure of success in accomplishing its goals (Power, Murphy, & Coover, 1996). We believe that this type of approach to the race-related issues we have outlined in this paper merits further exploration in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R03-AA09885). We wish to acknowledge, with gratitude, Denise Welka Lewis, Scott Desmond, Lisa Gervase, and Thomas Lambing for their contributions to this study’s data collection efforts.

Footnotes

The best way to understand the concept of camera cut is to think of looking through the lens of a camcorder, as if one were filming. Whatever is seen through the lens is in the field of vision. If someone moved outside of the field of vision and then returned to it, either because of his/her own movement or because of the movement of the camcorder’s field of vision, that would constitute two camera cuts by this study’s definition—one when he/she was initially in the picture, and a second one when he=she returned to view again after the temporary disappearance.

Time increments for these computations were based in much the same manner that parking garage fees are based. If someone stays for 1 hour and 15 minutes, that person is charged for two hours. Likewise, in this study, if a cartoon had a running time of eight minutes and ten seconds, the computations for major/minor character are based on a nine-minute-long cartoon rule.

Many dialogs and verbal exchanges or utterances do not involve complete sentences, but instead, are based on “shorthand” responses that take the place of complete sentences. For instance, if someone asked “How are you doing today?” and the response given was “fine,” in this study, the “fine” reply would be considered one phrase counting as a sentence, since it is the functional equivalent of a “I am doing fine” complete sentence response.

Further analysis of the data (not previously presented) revealed that these entertainment-type activities on the part of African American characters were highly prevalent during the 1930s and 1940s but almost completely vanished from the 1950s onward. Thus, as stated above, this type of negative portrayal of African American characters was not typical of the group’s behaviors during all time periods, but rather, of their portrayals during the earlier decades studied.

Asians constituted 2.8% of the American population but 4.3% of the cartoon characters studied during the 1990s.

Hanna Barbera, for example, included safety-related interstitial segments into its hour-long Superfriends cartoon block during the mid-1970s. These featured the Wonder Twins in 3-minute self-contained cartoons that focused on such topics as crossing the street safely, how to be safe underwater, how to avoid drug use, and so forth. ABC is perhaps the best known provider of interstitial animated programming with its Schoolhouse Rock interstitial between-program segments featuring well-known vignettes like “I’m Only a Bill,” “Conjunction Junction,” and “Interplanet Janet.” Most recently, the Warner Brothers studio’s cartoon programs The Animaniacs and Pinky and the Brain incorporated highly-entertaining interstitial animated cartoons of 1 to 3 minutes in length, focusing on such subjects as the names of various countries of the world, different types of cheese, and the countries from which they originate, and the elements of the periodic table.

Contributor Information

HUGH KLEIN, Kensington Research Institute, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA.

KENNETH S. SHIFFMAN, Cable News Network, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

REFERENCES

- Akers RL (1973). Deviant behavior. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1971). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bang HK & Reece BB (2003). Minorities in children’s television commercials: New, improved, and stereotyped. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 37, 42–67. [Google Scholar]

- Berg CR (1990). Stereotyping in films in general and of the Hispanic in particular. Howard Journal of Communications, 2, 286–300. [Google Scholar]

- Billings AC (2004). Depicting the quarterback in black and white: A content analysis of college and professional football broadcast commentary. Howard Journal of Communications, 15, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Children Now. (2001). Fall colors 2000–2001. Found at www.childrennow.org, last retrieved on May 10, 2006.

- Children Now. (2004). Fall colors 2003–2004: Prime time diversity report. Found at www.childrennow.org, last retrieved on May 10, 2006.

- Coltraine S & Messineo M (2000). The perpetuation of subtle prejudice: Race and gender imagery in 1990s television advertising. Sex Roles, 42, 363–389. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon TL & Linz D (2000). Race and the misrepresentation of victimization on local television news. Communication Research, 27, 547–573. [Google Scholar]

- Donlon MM, Ashman O, & Levy BR (2005). Re-vision of older television characters: A stereotype-awareness intervention. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 307319. [Google Scholar]

- Eschholz S, Bufkin J, & Long J (2002). Symbolic reality bites: Women and racial=ethnic minorities in modern film. Sociological Spectrum, 22, 299–334. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbner G & Gross L (1976). Living with television: The violence profile. Journal of Communication, 26, 173–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glascock J & Preston-Schreck C (2004). Gender and racial stereotypes in daily newspaper comics: A time-honored tradition? Sex Roles, 51, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg BS (1982). Television and role socialization: An overview In Pearl D, Bouthilet L, & Lazar J (Eds.), Television and behavior: Ten years of scientific progress and implications for the eighties: Vol. 2, 179–190. Technical reviews. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg BS, Mastro D, & Brand JE (2002). Minorities and the mass media: Television into the 21st century In Bryant J & Zillman D (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 333351). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin M, Dodd JE, Chance J, & Walsdorf K (2004). Sporting images in black and white: Race in newspaper coverage of the 2000 Olympic games. Howard Journal of Communication, 15, 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood J & Anderson K (2002). The presence and portrayal of social groups on prime-time television. Communication Reports, 15, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hess TH, Hess KD, & Hess AK (1999). The effects of violent media on adolescent inkblot responses: Implications for clinical and forensic assessments. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55, 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson LA & Ervin KS (1991). The frequency and portrayal of Black females in fashion advertisements. Journal of Black Psychology, 18, 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kielwasser AP & Wolf MA (1993–1994). Silence, difference, and annihilation: Understanding the impact of mediated heterosexism on high school students. High School Journal, 77, 58–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel D, Wilson BJ, Linz D, Potter J, Donnerstein E, Smith SL, Blumenthal E, & Gray T (1996). Violence in television programming overall: University of california santa barbara study. In Mediascope, Inc., National Television Violence Study 1994–1995 (pp. I1I172). Studio City, CA: Mediascope, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Larson MS (2002). Race and interracial relationships in children’s television commercials. Howard Journal of Communications, 13, 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Lavin MA & Cash TF (2001). Effects of exposure to information about appearance stereotyping and discrimination on women’s body images. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenberg J (1991). The encyclopedia of animated cartoons. New York: Facts on File. [Google Scholar]

- Li-Vollmer M (2002). Race representation in child-targeted television commercials. Mass Communication and Society, 5, 207–228. [Google Scholar]

- Maltin L (1980). Of mice and magic: A history of american animated cartoons. New York: Plume. [Google Scholar]

- Mares ML & Woodard E (2005). Positive effects of television on children’s social interactions: A meta-analysis. Media Psychology, 7, 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Mastro DE & Stern SR (2003). Representations of race in television commercials: A content analysis of prime-time advertising. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 47, 638–647. [Google Scholar]

- Merskin D (1998). Sending up signals: A survey of Native American media use and representation in the mass media. Howard Journal of Communications, 9, 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Mok TA (1998). Getting the message: Media images and stereotypes and their effect on Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 4, 185–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohye BY & Daniel JH (1999). The “other” adolescent girls: Who are they? In Johnson NG & Roberts MC (Eds.), Beyond appearance: A new look at adolescent girls (pp. 115–119). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Paek HJ & Shah H (2003). Racial ideology, model minorities, and the “notso-silent partner.” Stereotyping of Asian Americans in U.S. magazine advertising. Howard Journal of Communications, 14, 225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Paik H & Comstock G (1994). The effects of television violence on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis. Communication Research, 21, 516–546. [Google Scholar]

- Power JG, Murphy ST, & Coover G (1996). Priming prejudice: How stereotypes and counter-stereotypes influence attribution of responsibility and credibility among ingroups and outgroups. Human Communication Research, 23, 36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rada JA & Wulfemeyer KT (2005). Color coded: Racial descriptors in television coverage of intercollegiate sports. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 49, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shrum LJ, Wyler RS Jr., & O’Guinn TC (1998). The effects of television consumption on social perceptions: The use of priming procedures to investigate psychological processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 447–458. [Google Scholar]

- Signorielli N & Morgan M (1990). Cultivation analysis: New directions in media effects research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Singer MI, Slovak K, Frierson T, & York P (1998). Viewing preferences, symptoms of psychological trauma, and violent behaviors among children who watch television. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 1041–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E (1998). Modeling of eating pathology and social reinforcement of the thinideal predict onset of bulimic symptoms. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 36, 931–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 825–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CR, Lee JY, & Stern BB (1995). Portrayals of African, Hispanic, and Asian Americans in magazine advertising. American Behavioral Scientist, 38, 608–621. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CR & Stern BB (1997). Asian-Americans: Television advertising and the “model minority” stereotype. Journal of Advertising, 26, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen SR, McCoy JK, & Williams M (2001). Internalizing the impossible: Anorexic outpatients’ experiences with women’s beauty and fashion magazines. Eating Disorders, 9, 49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggeman M & Pickering AS (1996). Role of television in adolescent women’s body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 20, 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin MA, Haddock SA, Zimmerman TS, Lund LK, & Tanner LR (2003). Images of gender, race, age, and sexual orientation in Disney feature-length animated films. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 15, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). Statistical abstract of the united states. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM (2002). Does television exposure affect emerging adults’ attitudes and assumptions about sexual relationships? Correlational and experimental confirmation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar]