Abstract

We integrate heterogeneous terminologies into our category-theoretic model of faceted browsing and show that existing terminologies and vocabularies can be reused as facets in a cohesive, interactive system. Commonly found in online search engines and digital libraries, faceted browsing systems depend upon one or more taxonomies which outline the structure and content of the facets available for user interaction. Controlled vocabularies or terminologies are often curated externally and are available as a reusable resource across systems. We demonstrated previously that category theory can abstractly model faceted browsing in a way that supports the development of interfaces capable of reusing and integrating multiple models of faceted browsing. We extend this model by illustrating that terminologies can be reused and integrated as facets across systems with examples from the biomedical domain. Furthermore, we extend our discussion by exploring the requirements and consequences of reusing existing terminologies and demonstrate how categorical operations can create reusable groupings of facets.

Keywords: Faceted Browsing, Terminologies, Category Theory, Information Reuse

1 Introduction

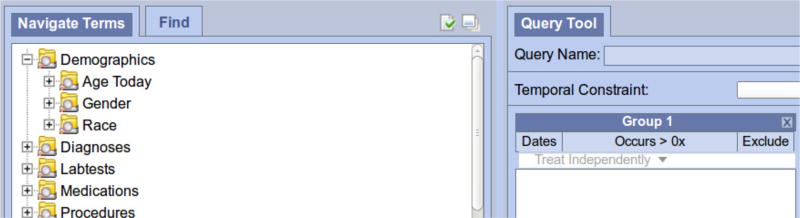

Faceted classification is the process of assigning facets to resources in a way that enables intelligent exploratory search aided by an interactive faceted taxonomy [30]. Exploratory search using a faceted taxonomy is often called faceted browsing (or faceted navigation or faceted search) [14] and is commonly found in digital libraries or online search engines. Facets are the individual elements of the faceted taxonomy and are simply attributes known to describe an object being cataloged; these collections of facets are often organized as sets, hierarchies, lattices, or graphs. Facets are usually shown alongside a list of other related, relevant facets that aid in interactive filtering and expansion of search results [15]. A simple example of facets for a digital library of books would be genre or publication date. The taxonomy behind the interface is either custom to the search needs of the interface or bootstrapped by a terminology familiar to those with working knowledge of the domain. In the biomedical domain, patients are often classified according to ICD10 diagnosis codes [31] in their electronic health record; as seen in Figure 1, the i2b2 query tool is capable of searching for patients using ICD10 codes [19] as well as other common biomedical terminologies. We will discuss i2b2 and another biomedical application in Section 4.

Fig. 1.

Users can select from a variety of biomedical facets within i2b2, including those from existing and well-known terminologies; a subset of the ICD10 terminology as viewed through the i2b2 query tool is shown here.

Facet models formalize faceted data representations and the interactive operations that follow for exploratory search tasks. Wei et al. observed three major theoretical foundations behind current research of facet models: set theory, formal concept analysis, and lightweight ontologies [30]. In our previous work, we demonstrated that category theory can act as a theoretical foundation for faceted browsing that encourages reuse and interoperability by uniting different facet models together under a common framework [9, 10]. We also established facets and faceted taxonomies as categories and have demonstrated how the computational elements of category theory, such as products and functors, extend the utility of our model [9]. The usefulness of faceted browsing systems is well-established in the digital libraries research community [8, 20], but reuse and interoperability are typically not major design considerations [9]. Our goal is to create a rich environment for faceted browsing where reuse and interoperability are primary design considerations.

In this extended paper [11], we integrate heterogeneous terminologies as facets into the category-theoretic model of faceted browsing [10] so that existing and well-known terminologies can be reused in an intelligent manner. These terminologies themselves can act as a faceted taxonomy, but we also demonstrate the usefulness of modeling a terminology as a facet type. We discuss how to create instances of facets and faceted taxonomies in order for our model to interact with multiple, heterogeneous sources. In our extension, we show that categorical pushout and pullback operations help construct reusable groupings of facets. We demonstrate how multiple terminologies can coexist, work together efficiently, and contribute toward the ultimate goal of a particular faceted interface. We present and compare two considerations for modeling faceted browsing interfaces that utilize multiple terminologies: the need to merge facets together into a single “master” taxonomy and the need for multiple focuses from different terminologies.

2 Background

We must discuss faceted taxonomies and introduce concepts from category theory before discussing our category-theoretic model of faceted browsing and its extensions.

2.1 Faceted Taxonomies

At the heart of faceted browsing, regardless of the facet model chosen for a particular interface, there lies a taxonomy which organizes and gives structure to the facets that describe the resources to be explored. Faceted taxonomies can aid in the construction of information models or aid in the construction of a larger ontology [4, 22]. If facet browsing is truly a pivotal element to modern information retrieval [7], then great care must be taken to abstractly model and fully integrate the taxonomies behind the interface. Depending upon the needs and complexity of its design, a faceted browsing interface may rely upon one or many faceted taxonomies to drive exploration and discovery.

2.2 Category Theory

Category theory has been useful in modeling problems from multiple science domains [25], including physics [6], cognitive science [21], and computational biology [26]. Categories also model databases [23, 25] where migration between schemas can be represented elegantly [24]. We will demonstrate that facets and schemas are structurally related in Section 3.2.

In this section, we introduce a few concepts from category theory that are necessary for understanding our model. Informally, a category 𝒞 is defined by stating a few facts about the proposed category (specifying its objects, morphisms, identities, and compositions) and demonstrating that they obey identity and associativity laws [25].

Definition 1

A category C consists of the following:

A collection of objects, Ob(𝒞).

A collection of morphisms (also called arrows). For every pair x, y ∈ Ob(𝒞), there exists a set Hom𝒞(x, y) that contains morphisms from x to y; a morphism f ∈ Hom𝒞(x, y) is of the form f : x → y, where x is the domain and y is the codomain of f.

For every object x ∈ Ob(𝒞), the identity morphism, idx ∈ Hom𝒞(x, x), exists.

For x, y, z ∈ Ob(𝒞), the composition function is defined as follows: ○ : Hom𝒞(y, z) × Hom𝒞(x, y) → Hom𝒞(x, z).

Given 1–4, the following laws hold:

identity: for every x, y ∈ Ob(𝒞) and every morphism f : x → y, f ○ idx = f and idy ○ f = f.

associativity: if w, x, y, z ∈ Ob(𝒞) and f : w → x, g : x → y, h : y → z, then (h ○ g) ○ f = h ○ (g ○ f) ∈ Hom𝒞(w, z).

Our model of faceted browsing leverages two well-known categories: Rel and Cat. We leverage these as building blocks in our model by creating subcategories: categories constructed from other categories by taking only a subset of their objects and the necessary corresponding morphisms.

Definition 2

Rel is the category of sets as objects and relations as morphisms [1], where we define relation arrows f : X → Y ∈ HomRel (X, Y) to be a subset of X × Y.

Definition 3

Cat is the category of categories. The objects of Cat are categories and the morphisms are functors (mappings between categories).

Functors can informally be thought of as mappings between categories, but additional conditions are required:

Definition 4

A functor F from category 𝒞1 to 𝒞2 is denoted F : 𝒞1 → 𝒞2, where F : Ob(𝒞1) → Ob(𝒞2) and for every x, y ∈ Ob(𝒞1), F : Hom𝒞1 (x, y) → Hom𝒞2 (F(x), F(y)). Additionally, the following must be preserved:

identity: for any object x ∈ Ob(𝒞1), F(id𝒞1) = idF(𝒞1).

composition: for any x, y, z ∈ Ob(𝒞1) with f : x → y and g : y → z, then F(g ○ f) = F(g) ○ F(f).

In this section, we describe our category-theoretic model of faceted browsing. We demonstrated previously that our model encourages and facilitates reuse and interoperability within and across faceted browsing systems; we describe only the key elements and leave the minor details available in our prior work [9].

Definition 5

Let Tax be a sub-category of Rel, the category of sets as objects and relations as morphisms where Ob(Tax) = Ob(Rel) and let the morphisms be the relations that correspond only to the ⊆ relations. The identity and composition definitions are simply copied from Rel.

Tax is simply a slimmer version of Rel, where we know exactly what binary relation is being used to order the objects. In our previous work, we did not apply a name to Tax and left this category described as Rel restricted to inclusion mappings [9]; applying a name allows us to be concise in our discussions, which is important because Tax will be the building block that will allow us to apply the additional structure and granularity needed to support faceted browsing. We can refer to an independent facet, such as genre, language, or price-range, as a facet type.

Definition 6

A facet type (a facet i and its related sub-facets) of a faceted taxonomy is a sub-category of Tax, the category of sets as objects and inclusion relations as morphisms. Let us call this sub-category Faceti and let Ob(Faceti) ⊆ Ob(Tax) with the morphisms being the corresponding ⊆ relations for those objects. The relevant identity and composition definitions are also copied from Tax.

From this facet type, users make focused selections when drilling down into faceted data. This selection pinpoints a subset of the facets within this type and by proxy, it pinpoints a subset of the resources classified.

Definition 7

We can define a subcategory of Faceti, called Focusi, to represent a focused selection of objects from Faceti having Ob(Focusi) ⊆ Ob(Faceti) and the necessary corresponding morphisms, identity, and composition definitions for those objects.

Each individual facet category belongs to a larger taxonomy that collectively represents the structure of information within a facet browsing system.

Definition 8

Let FacetTax be a category that represents a faceted taxonomy, whose objects are the disjoint union of Faceti categories. In other words, let and n = |Ob(FacetTax)|. The morphisms of FacetTax are functors (mappings between categories) of the form HomFacetTax(𝒞, 𝒟) = {F : 𝒞 → 𝒟}.

Once you have a faceted taxonomy constructed, interactivity and engagement with it follows; a natural task for users of a faceted system is to perform queries that focus and filter objects being explored.

Definition 9

A facet universe, U, is the n-ary product [1] within the FacetTax category, defined as , where n = |Ob(FacetTax)|. The n coordinates of U are projection functors Pj : ∏ Faceti → Facetj , where j = 1, …, n is the jth projection of the n-ary product.

Note that since Focusi is a subcategory of Faceti, there exists a restricted universe U⊆ ⊆ U where every facet is potentially reduced to a focused subset. The act of querying the universe is essentially constructing this restricted universe U⊆.

Definition 10

A faceted query, Q, is the modified n-ary product [1] within the FacetTax category, defined as , where n = |Ob(FacetTax)|. The n coordinates of Q are similarly defined as projection functors Pj : ∏ Focusi → Focusj.

2.3 A Category-theoretic Model

We visually summarize the key containers and products in Figure 2. We will later demonstrate that this same faceted taxonomy can be represented as a graph. The objects of each Faceti are sets of resources that have been classified as belonging to that facet type; our model can reuse the facets and adjust the surrounding structure to fit our needs: if we wish to arrange the facets as graphs, we can do so without bothering the resource and facet linkages.

Fig. 2.

The structure of facet, focus, and taxonomy are easy to visualize due to their natural hierarchical relationships. Universes and queries are products utilizing this structure.

Figure 3 shows a sample piece of a medication taxonomy; each resource is classified using the taxonomy. In our model, we refer to resources in the general sense. The type of resource depends upon the interface: resources could be books in a digital library system, documents in a electronic health system, and so on. Note that the taxonomy in Figure 3 could easily be considered the facet type medications, which belongs to a large taxonomy (not pictured) instead of a complete faceted taxonomy to itself; either scenario is acceptable as this will depend upon the design of the faceted browsing system, which can vary.

Fig. 3.

We show a sample faceted taxonomy for medications. The objects of each Facet are pointers to a resource that has been classified as belonging to that particular facet type.

3 Leveraging Multiple Terminologies

The category-theoretic model is perfectly capable of representing basic faceted interfaces in its current form, but the ability to model and interact with multiple heterogeneous sources is needed to support more intricate interfaces. The capacity to integrate multiple terminologies rests largely upon our ability to model instances of our facet categories. Understanding the relationship between schemas and facets will be key to understanding the process for creating instances.

In our previous work on modeling faceted browsing for reusability, we demonstrated the importance that graphs play in reusing and integrating models [9]. We confirm this importance in the following sub-sections.

3.1 Underlying Graphs

The ability to transform into other structures enables the category theoretic model of faceted browsing to consume other models. We show that graphs underlie categories and that a graph-based representation of a facet can be used as input in modeling taxonomies.

Definition 11

Grph is the category with graphs as objects. A graph G is a sequence where G := (V, A, src, tgt) with the following:

a set V of vertices of G

a set A of edges of G

a source function src : A → V that maps arrows to their source vertex

a target function tgt : A → V that maps arrows to their target vertex

Definition 12

The graph underlying a category 𝒞 is defined as a sequence U(𝒞) = (Ob(𝒞), Hom𝒞, dom, cod) [25].

We previously demonstrated given that there exists a functor U : Cat → Grph, so FacetTax can produce graphs of Faceti categories for i = (1, …, |Ob(FacetTax)|) [9].

Definition 13

Let U(Faceti) be the underlying graph of an individual facet and let U(FacetTax) be the underlying graph of the faceted taxonomy at large, as constructed and detailed above.

This underlying graph will be important in discussing the relationship between schemas and faceted taxonomies, which will allow us to create instances of facets and faceted taxomonies.

3.2 Facet and Schema

In this section, we describe how to create instances of facets and faceted taxonomies with a method and rationale that is inspired by Spivak’s database schemas [25]. In fact, we discover that facets are equivalent to database schemas. Although this equivalence may be unexpected initially, conceptually the idea of a database schema is not unlike facets when viewed from a category theory perspective: both describe the conceptual layout that organizes information (rows/entities in the case of databases and resources in the case of facets). Figure 4 shows the same faceted information found in Figure 3, but within a schema. Note that parts of the table are abbreviated with ellipses in order to save space. We will discuss these tables and their relationship with faceted browsing in detail in the next section.

Fig. 4.

A resource table and a medications table using example data from Figure 3 shows the role that primary and foreign keys play in modeling faceted browsing.

Preliminary Definitions

Spivak’s definition of schemas depends upon the idea of congruence, which in turn depends on defining paths, path concatenation, and path equivalence declarations [25].

Definition 14

If G := (V, A, src, tgt) is a graph, then a path of length n in G is a sequence of arrows denoted , where PathG is the set of paths in G [25].

Definition 15

Given a path p : v → w and q : q → x, p + +q : v → x is the concatenation of the two paths [25].

Definition 16

A path equivalence declaration (abbreviated by Spivak as PED) is an expression of the form p ≃ q, where p, q ∈ PathG have the same source and target, e.g., src(p) = src(q) and tgt(p) = tgt(q) [25].

Definition 17

A congruence on G is a relation ≃ on PathG with the following [25]:

The relation ≃ is an equivalence relation.

If p ≃ q, then src(p) = src(q) and tgt(p) = tgt(q).

If given paths p, p′ : a → b and q, q′ : b → c, and if p ≃ p′ and q ≃ q′, then (p + +q) ≃ (p′ + +q′).

Informally, a congruence is an enhanced equivalence relation that marks how different paths in G relate to one another by enforcing additional constraints; pairing a graph with a congruence forms a schema [25].

Categorical View of Schemas

We give Spivak’s definition of a schema below; this definition is generic enough to also apply to faceted browsing when looking at the underlying graph of the facet categories. Figure 4 contains a schema corresponding to the medications example from Figure 3.

Definition 18

A schema S is a named pair S = (G, ≃), where G is a graph and ≃ is a congruence on G [25].

Note that the keys in Figure 4 would normally be integer keys, but here text labels are applied to increase readability and to improve the ease of understanding the example. The resource table in this schema contains a generic list of resources (for example, documents or library items) where each resource has a foreign key indicating how it is classified. The medications table contains a list of classes and sub-classes for medications, as well as a self-referential foreign key pointing back at itself; this foreign key indicates this particular medication’s ancestor. The self-referential key gives additional structure to the medication classes and sub-classes found within the table without the need for additional relationship tables; this method of storing a taxonomy is similar to closure tables [16].

In Figure 4, the entry with Medication as its key has no foreign key. This null relationship indicates that it is the root of this particular facet graph; with respect to the category-theoretic model, it implies there are no morphisms having this object in its domain.

3.3 Instances of Facets and Faceted Taxonomies

An instance of a facet is a collection of objects whose data are classified according to specific relationships, such as the one illustrated in Figure 3. We formalize this below using Spivak’s instances of schemas as inspiration [25].

Definition 19

Let F = (U(Faceti),≃), where the graph underlying a facet type is denoted U(Faceti) for some Faceti ∈ Ob(FacetTax) and where ≃ is a congruence on U(Faceti). An instance on F is denoted (Facet, Ancestor) : F → Set where:

Facet is a function defined as Facet : V → Set, so for each vertex v ∈ V we can recover a set of facets denoted Facet(v) within this facet type.

for every arrow a ∈ A having v = src(a) and w = tgt(a), a function Ancestor(a) : Facet(v) → Facet(w).

congruence is preserved: for any v, v′ ∈ V and paths p,p′ from v to v′ where p = v[f0, f1, f2, …, fm] and p′ = [f0′, f1′, f2′, …, fn′], if p ≃ p′, for all x ∈ Facet(v), ancestor(fm) ○ … ○ ancestor(f1) ○ ancestor(f0)(x) = ancestor(fn′) ○ … ○ ancestor(f1′) ○ ancestor(f0′)(x) ∈ Facet(v′)

To create instances of FacetTax, the logic remains the same from Facet: take the underlying graph and a congruence. Instead of looking at the underlying graph of a single facet type, the underlying graph of FacetTax is considered. We will use instances in the next section to model the integration and reuse multiple heterogeneous sources of information.

4 Bootstrapping Faceted Taxonomies

Faceted taxonomies are common in the biomedical domain where controlled vocabularies are curated and integrated into interfaces in order to assist in the exploration and interaction required by the system. We present two different use cases for faceted taxonomies with different requirements: one where merging heterogeneous terminologies into a single taxonomy fits the design of the interface (for example, i2b2) and one where having control over multiple independent instances of facets is desired (for example, DELVE).

4.1 Designing Faceted Systems

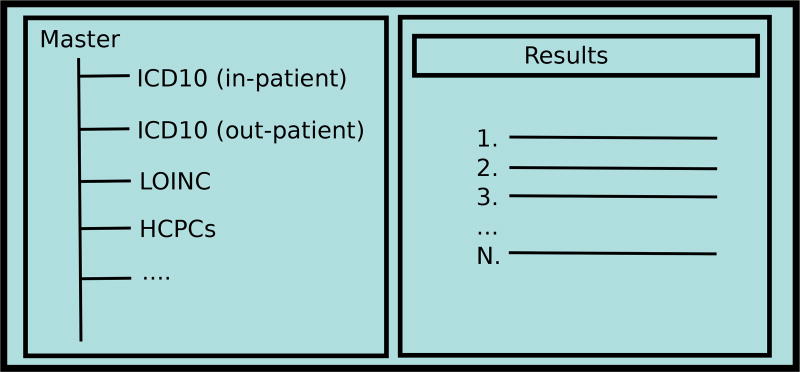

A common design for faceted systems that require multiple terminologies is to simply merge everything together into a centralized master taxonomy; this merged taxonomy is often how lightweight ontologies, discussed as one of the three foundations of facet models [30], are constructed. The merged taxonomy may or may not have multiple instances of the same terminology, depending upon what is needed for the interface. For example, in the conceptual skeleton of the interface presented in Figure 5, the merged taxonomy has multiple existing biomedical terminologies, including two instances of ICD10, based upon whether the resources are classified as belonging to in-patient or out-patient resources. In Section 4.2, we will discuss i2b2, a modern biomedical research tool that estimates patient cohort sizes by constructing Boolean queries from a merged faceted taxonomy.

Fig. 5.

A web interface could merge multiple instances together into a master taxonomy.

Alternatively, multiple terminologies can peacefully co-exist within a single interface without being merged into a master taxonomy. In fact, it could be a pivotal design element in the interface that allows for a deeper exploratory search of the resources by enabling multiple points of faceted search. In Figure 6, we show a conceptual skeleton for a faceted system utilizing multiple terminologies and multiple instances of ICD10. For example, such an interface could leverage ICD10 to draw a graph of facets (i0) and a tree of related facets (i2) and enable the user to interactively explore resources which could be a simple list with annotations (i1). This example is similar to the spirit of DELVE, discussed in Section 4.8, where facets are contained within and help drive visualizations.

Fig. 6.

A web interface containing multiple instances of a terminology in discrete components assists interaction.

4.2 i2b2

The i2b2 (Informatics for Integrating Biology and the Bedside) query tool al- lows researchers to locate patient cohorts for clinical research and clinical trial recruitment [19]; the tool itself provides a drag-and-drop method of creating Boolean queries of inclusion and exclusion criteria from a hierarchical list of facets. For example, if someone wanted to search for only female patients, they would click into the Demographics facet, into the Gender facet, and drag Female to the first query panel. In addition, if they wanted female diabetics, they would also navigate into the Diagnoses facet and drag the desired type of diabetes into the second panel. i2b2’s Boolean queries are formed from having logical or-statements across panels and and-statements within a panel. With respect to the example above, if the user wanted female diabetic and hypertensive patients, they would also find the hypertension facet and drag it into the same panel having diabetes, so that the panel represents patients having either diabetes or hypertension. This Boolean construction can be continued with any number of facets from any number of terminologies.

The biomedical domain has a long history of curating and maintaining controlled vocabularies and terminologies, such as those found in the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) [2]. The structure behind these terminologies is a rich source for building faceted browsing systems that explore resources having been classified with these standards.

In Fig 7, the taxonomy of a local implementation of i2b2 is partially shown; note that every facet type of a patient is compiled into a central taxonomy as part of the meta-data cell for i2b2 [19]. This means that the central taxonomy has very different concepts, such as diagnoses and laboratory procedures, residing in the same table. Our local implementation of i2b2 uses ICD10 codes [31] for diagnoses and HCPCs codes [5] for procedures; these terminologies are externally and independently curated and made available by their creators. To i2b2, diagnosis is a facet type and ICD10 provides the organizational structure behind diagnoses, but ICD10 is a full terminology and one can consider ICD10 itself to be a facted taxonomy for diagnoses; the use of large-scale existing terminologies in faceted browsing system blurs the line between facet types and facet taxonomies, similar to our example and discussion of Figure 3. Our modeling technique needs to be able to abstractly and consistently model both of these cases. In either case, the goal is encouraging the reuse of existing terminologies so that our faceted taxonomies contain accepted interoperable standards. An extension of i2b2 allows networking queries between institutions, so that one Boolean query can return counts of patients from multiple clinical sites; this would be impossible without integration of accepted biomedical terminologies into the faceted backbone of i2b2.

Fig. 7.

The i2b2 query tool uses drag-and-drop interaction to construct patient queries.

4.3 Merge Operations

Suppose we have multiple instances of facets, I0, I1, …, IN, how do we satisfy the requirements of an application such as i2b2 that expects a single instance to act as a master? For example, I0 could be medications, while I1 could be procedures, and so on.

Each Faceti category is disjoint and contains no linkage to another Facetj where i ≠ j, so we must manufacture a link. This link is a meta-facet, an organizational tool that typically aids in drawing the faceted taxonomy [9]. By design, the meta-facet must connect to the root of each facet; we can easily identify the root in our facet graph because it is the only entry with a null ancestor. Given an instance, such as I0 above, we know that the root of I0 is the source of an arrow a ∈ A from U(Facet0) where Ancestor(a) is the empty set; we shall call this function that returns the root object root(Ii) : A → Set for some instance Ii.

Definition 20

Let FacetM be a meta-facet category for categories Facet0, …, FacetN, containing a meta-object and the roots of the others:

M is a meta-object sharing a relationship with every object: HomFacetM(M, x) for each x ∈ Ob(FacetM).

Figure 8 illustrates adding a meta-facet to join together a collection of facets; each black subtree represents a particular facet type. M is a new meta-object that must be created; the gray and dotted arrows that link this meta-object and the roots of the other facet graphs must be created as well.

Fig. 8.

A meta-facet can assist in merging facets together by providing a common anchor point.

Let us define the union of two underlying graphs, U(Faceti) and U(Facetj), as the union of its constituent parts. By definition, the sets of vertices and arrows for graphs underlying two Facet categories, Faceti and Facetj, are disjoint and can be merged with the union of corresponding vertices and arrows; this leaves the graph disconnected, since Faceti and Facetj have no object in common.

Using the root of each instance and a meta-facet, we can create a new instance connecting every other underlying graph to our meta-facet:

Definition 21

The merger of instances I0, I1, …, IN of categories Facet0, …, FacetN is a new instance IM on (GU, ≃U) where:

GU = U(Facet0) ∪ … ∪ U(FacetN) ∪ U(FacetM). This is the union of the underlying graphs of the meta-data facet and the facets that are merging.

≃U is a congruence on GU. We define this the same as in Section 3.3 but do note that the collection of paths have grown. No two paths in the merging categories conflict because the facets are disjoint by definition.

The merged instance IM is not defined much differently than I0, …, IN in that it still maintains (Facet, Ancestor) : F → Set function mappings; the only difference is that the underlying graph has changed with additional path considerations. The merge operation is simply a transformation: we are manipulating the facets into a graph and symbolically merging graphs to suit our needs. The information regarding classified resources that is embedded into each facet gets reused; only the surrounding structure changes. In the following section, we formally define pullbacks and give an example of the utility of merged instances.

4.4 Pullback Operations

Recall that the objects of each Faceti categories are sets of pointers toward resources which have been classified as belonging to a particular facet. Our model can create higher-level faceted groupings from existing facets by leveraging categorical pullback operations, also known as fiber products [25]; these operations model interactive conjunctions within instances of Faceti and FacetTax categories, yielding new facet types that are not available directly in the taxonomy.

Definition 22

Given sets A, B, C ∈ Ob(𝒞) for some category 𝒞, a pullback of A and B over C is any set D where an isomorphism A ×C B → D exists for A ×C B = {(a, b, c)|f(a) = c = g(b)}; this is illustrated below, using Spivak’s ⌟-notation to label the pullback [25]:

|

The result of a pullback is easily illustrated with an example. If horror and comedy belong to the facet type for genres of either movies or books, then we can draw the relationships between horror and comedy easily:

|

We derive a new set that we can label horror and comedy by applying the pullback to the set of horror and the set of comedy objects:

|

This forms a new set of objects being characterized by a conjunctive facet not directly found in the facet type; we could even give this new set a new semantic name: comedic horror. The direct semantic name for groupings found indirectly within the data can become an engaging element of the interface, eliminating the possibility of the user being limited only to interaction with facets defined directly within the original taxonomy.

The projection functions π1 and π2 may look trivial: a comedic horror title is clearly a comedy and clearly a horror title. Despite simplicity in appearance, the utility of the projection functions π1 and π2 mapping back to the original facets can be seen with faceted cues: for example, we can use π1 to highlight comedic horror titles within the horror titles.

Since patients in i2b2 are classified across multiple merged terminologies, we can use pullbacks to create reusable conjunctions to bridge across facet types in instances of FacetTax. A common goal within i2b2 is to identity groups of patient cohorts by dragging and dropping facets from a master taxonomy. A clinical researcher can quickly refine Boolean queries targeting patient populations; often these queries have a base population that can be specified as a conjunction. For example, a clinical researcher studying patients with breast cancer who have undergone a mastectomy procedure needs the ability to quickly reference such a population. We diagram what the data provides below:

|

(1) |

If we apply the pullback to the category of procedure (Mastectomy) and the category of diagnosis (Breast Cancer), we get a new category that we can label Breast Cancer and Mastectomy:

|

(2) |

This new category becomes an interactive element that can be reused within the interface; within i2b2, conjunctions can be annotated with a friendly human-readable name and can be shared across users. In the next section, we will demonstrate that pushouts help construct new facets from disjunctions.

4.5 Pushout Operations

Our model can assist in computing ad-hoc facets that attempt to compensate for short-comings in either the terminologies involved or the underlying data. In this section, we define what a pushout operation computes given specific sets of resources.

Definition 23

Given sets A, B, C ∈ Ob(𝒞) for some category 𝒞, a pushout of sets B and C over A is any set D where an isomorphism B ⊔A C ← D exists; this is illustrated below, using Spivak’s ⌜-notation to label the pushout [25]:

|

It is important to note that B ⊔A C was formed by the quotient of the disjoint union of A, B, C and an equivalence relation on B and C with A. An example will help demonstrate the utility of pushouts. Hypertensive patients are woefully under-diagnosed and relying solely on diagnosis codes to locate patients with hypertension is problematic [28]. In addition to diagnosis codes, vital signs are either recorded by medical providers or recorded by machines at given intervals; these measurements can be used to determine a person’s hypertensive state [28]. Recall that our resources for i2b2 are patients; patients can have diagnoses (from an instance of the ICD10 terminology) and vitals signs (from an instance of the LOINC terminology):

|

(3) |

We compute the pushout and receive a single anchor for those individuals that were either coded to have a hypertension diagnosis code or that were recorded having high blood pressure:

|

(4) |

The pushout acts as a convenient, derived facet that the user can interact with just like any other facet. In i2b2, the disjunction between diagnoses codes and vital signs can be performed without the pushout because the interface itself allows for Boolean queries to be performed by dragging and dropping any facet into its query window. The value of the pushout is simply for convenience and reuse: when the pushout is used by multiple people, the context of a patient with hypertension is made clear and reusable.

4.6 Faceted Views

We can construct commonly-used patient cohorts via pullback and pushout operations. In another example, we consider chronic kindey disease (CKD). CKD suffers from an issue similar to hypertension: diagnostic codes are not always used and might not capture the true disease state of the population, but laboratory results can predict CKD, including the disease’s stage [17].

In Figure 9, we show that pushouts can create new facets from existing ones in order to better address the needs of the interface. We create a facet for a hypertensive cohort by the pushout of diagnostic codes for hypertension and qualifying vital signs; we also create a cohort of CKD patients by considering CKD diagnostic codes and qualifying eGFR lab results. d1 and d2 are inclusion maps for the hypertensive cohort, while c1 and c2 are inclusion maps for the CKD cohort. The underlying taxonomies for patient data are large, having up to tens of thousands of nodes. The ability to create faceted views on top of the standard taxonomy will greatly improve the usability of an interface by providing the user with the most meaningful and efficient facets, resulting in targeted and relevant resources.

Fig. 9.

Faceted views can provide convenient, derived facets for interactivity.

4.7 Implementation

If we connect instances back to our notion that schemas are not structurally different than facets, it is clear that IM is simply another table containing N + 1 relationships with entries from the Facet0, …, FacetN categories sharing a relationship with the meta-facet. The foreign keys of these meta-relationships would simply point back to the roots of the other facets; this enables reuse in-place without needlessly copying data. Furthermore, this gives a clear implementation path for enabling reusable terminologies in a standard relational database, where tables help structure facets and the resources that have been classified accordingly. If a relational database is not possible for the application, then an equivalent scheme can be mimicked in other environments. For example, a web-application could use JSON (Javascript Object Notation) data interchange format [3] to store the taxonomy and links to resources.

4.8 DELVE

DELVE (Document ExpLoration and Visualization Engine) is our framework and application for browsing biomedical literature through heavy use of visualizations [12, 13]. In fact, our motivation for choosing category theory began when first designing DELVE, due to the difficulty in modeling facets that are controlled by visualizations or found within a visualization. In the case of i2b2, the design of the interface insists on merging terminologies together into a master taxonomy that directs exploration within the interface. With DELVE supporting multiple visualizations, a master taxonomy is unrealistic as each visualization potentially requires a different set of facets altogether.

Understanding DELVE

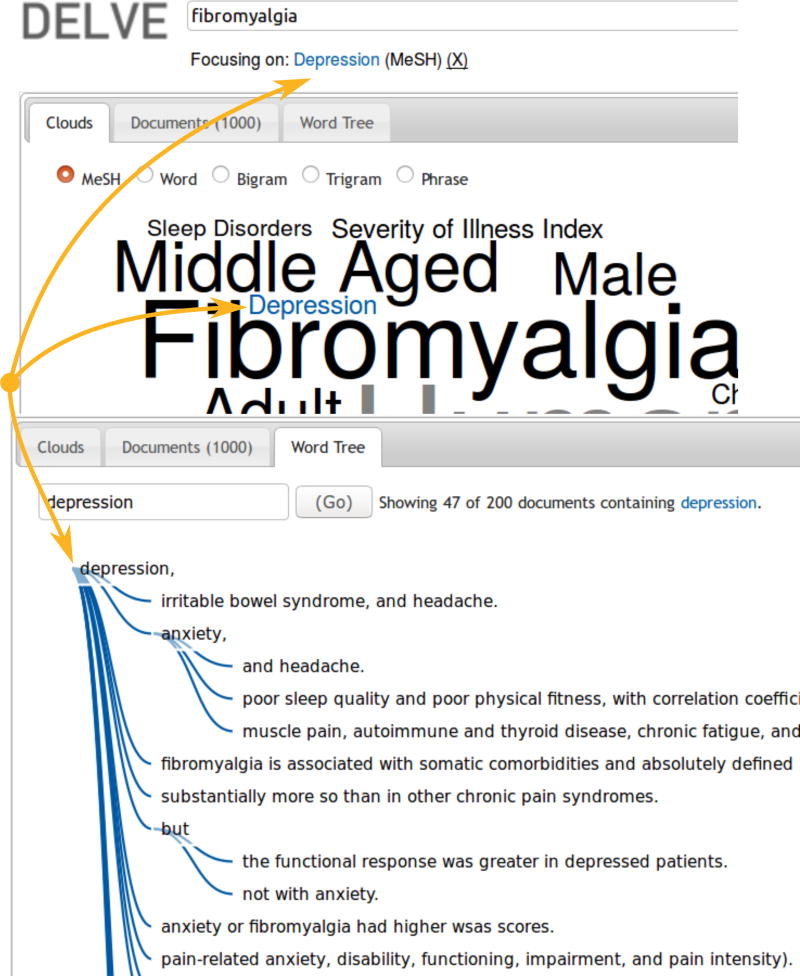

In Figure 10, a query for fibromyalgia is shown. The screen is split into two parts for this example; the abbreviated left-hand side contains a cloud [27] and the right-hand side contains a list of relevant biomedical publications. The default cloud shows the frequency of terms using the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) vocabulary; librarians at the National Library of Medicine manually review journal articles and tag them with appropriate MeSH terms [18]. MeSH terms are hierarchically organized and are typically accurate reections of the article's contents since they are manually assigned, making them great facet candidates. In addition to MeSH terms, we extend the general concept of world clouds [27] to unigrams, bigrams, trigrams, and common phrases.

Fig. 10.

DELVE contains visualizations controlled by facets as well as visualizations that contain facets.

DELVE provides other collections of terms as facets for two reasons: 1) interdisciplinary collaboration typically involves researchers interested in biomedical literature who are not familiar with MeSH terms and 2) granularity and phrasing of terms can be an issue. For example, a researcher queries for fibromyalgia using DELVE as seen in Figure 10; they are also interested in functional somatic syndromes but this term is not directly available as a MeSH term. Instead, articles covering functional somatic syndromes are typically tagged somatoform disorders; without this knowledge, a researcher could miss desired articles. DELVE resolves this issue by providing a list of biomedical trigrams as a facet, which was compiled by analyzing all trigrams found within Pubmed’s library of biomedical articles; the phrase functional somatic syndromes occurs in great frequency. From a modeling perspective, there are natural differences in the structure of the MeSH hierarchy and the collection of anchoring trigrams, but our categorical model naturally accounts for this by allowing objects to have any inclusive relationship within Facet categories: including those who have many (MeSH terms) and those who have none (DELVE’s trigrams). In DELVE’s case, instances of facets play a role when creating focused collections of documents based on what the user has selected through the interface, which could potentially span one or more facets.

Other visualizations, such as word trees and histograms, are available as part of the extensible nature of DELVE. We give an example of MeSH clouds and word trees working together in Section 4.9.

Focusing Considerations

The annotated screen-shot in Figure 11 demonstrates DELVE’s ability to use a facet to focus. In this example, a search for fibromyalgia is focused on the MeSH term analgesics, which causes the documents viewer to show only those documents that are classified as belonging to the MeSH term analgesics. Multiple points of focus are supported in the subsequent version of DELVE, such as focusing using different word clouds [27] and word trees [29]. If the user also selects the MeSH term female, the document viewer would only show those documents tagged with both MeSH terms analgesics and female. Color is used to visually offset the facets being focused upon. The document viewer ranks results according to how many occurrences of the focus terms can be found within the abstract of the corresponding article.

Fig. 11.

A DELVE search for fibromyalgia publications focusing on analgesics

Within one faceted taxonomy, aggregating focuses becomes a focused version of the queries discussed in Section 2. Suppose the user also wishes to focus on the trigram functional somatic disorders. If we have created instances of Facet categories as discussed in Section 3.3, we can also create instances of focused subcategories by taking a subgraph of the graph underlying Facet:

Definition 24

Given instances I0, I1, …, IN of categories Facet0, …, FacetN, let IF0, IF1, …, IFN be focused instances created by replacing U((Faceti)) with U(Focusi) for i = 0, 1, …, N.

Recalling Resources

At some point during a user’s interactive session in a faceted browsing system, it is advantageous or desirable to recall and list all resources that were classified according to a focused selection of facets. When creating instances of our facet categories, we defined a function capable of returning the ancestor of the facet type for a given facet. We can similarly define a function capable of returning focused resources.

Definition 25

Let R be a function defined as R(Focus, Resource) : Focus → Set, where:

Focus is a function similar to the Facet defined in Section 3.3: Focus : V → Set, so for each vertex v ∈ V we can recover a set of focused facets denoted Focus(v)

Resource is a function defined for every focused facet f ∈ Focus(v) above as Resource(f) : Focus(v) → Resource(f).

In other words, similar to how we defined a function Ancestor in Section 3.3 as a self-referential link back to facets, we now define a function that unrolls the foreign relationship between facets and resources. An example of this is seen in Fig 4: the resource with resource 2 as its key holds a foreign relationship with the medication that has anti-diabetic as its primary key. Relating this back to the definition above, we rephrase this as: for every facet in the graph, collect their primary keys (PKs) and from the resource table, collect any primary keys where any foreign keys match the original keys (PKs). At this point, the interface is free to present the resources as needed, which consequentially allows us to model ranking and sorting schemes for resources; we leave these discussions as future work.

4.9 Interacting with Word Clouds and Trees

In DELVE, facets contained in visualizations can work together harmoniously through a centralized point of focus; by default, focusing in one visualization will set the focus in all other visualizations. In Figure 12, we show a DELVE search for fibromyalgia and the result of focusing on the MeSH term depression. Within the MeSH cloud, the term is highlighted with blue and a secondary reminder cue containing the focused term is placed below the original query. The word tree redraws itself with the selected term as the root of the tree; this shows occurrences of the term depression within the sentences belonging to the classified resources, where redundancy is collapsed to a common prefix. For example, the following phrases are collapsed under tree nodes for depression followed by anxiety:

depression, anxiety, and headache.

depression, anxiety, poor sleep quality and poor physical fitness…

depression, anxiety, muscle pain, autoimmune and thyroid disease…

Fig. 12.

A DELVE search for fibromyalgia publications focusing on depression

From Figure 12, we can also see that the phrases of the form {depression, anxiety, and …} and the phrase {depression, but not with anxiety} point to different resources containing relationships between fibromyalgia, depression, and anxiety. The goal of DELVE is to immerse a researcher into an exploratory search system where visualizations help expedite the discovery process. This goal is made easier by constructing DELVE upon a solid theoretical foundation that has been demonstrated to intelligently reuse and integrate existing biomedical terminologies.

5 Future Work

As mentioned previously, a natural consequence of modeling facets, faceted taxonomies, and faceted browsing systems is that resources ultimately are retrieved. This opens the door to abstractly modeling and developing deeper manipulations of faceted data in a way that is transparent and reusable across systems. For example, we demonstrated that categorical constructions such as pullbacks and pushouts can help dynamically organize and reorganize faceted data. These types of operations could potentially lead to creating facets dynamically, where new facets are created on the y from computations involving existing facets. Other operations, such as retractions, need to be explored so that their role in the model is fully understood; this is the groundwork toward the next steps of ranking and sorting resources. It is important to note that category theory focuses largely on structure, but structural similarity does not necessarily imply functional similarity; existing knowledge bases and terminologies must be intelligently used and reused to supplement and extend our abstract framework.

We are developing an application programming interface (API) for faceted browsing and wish to include support for interfaces that require multiple heterogeneous terminologies. The mapping between schemas and facets clears the path to implementation with a database containing faceted data and taxonomies. Support for functional databases is growing [23, 24], but a traditional relational database is adequate. An API for faceted browsing can bridge the gap between a categorical model for faceted browsing and databases, allowing us to start with traditional relational databases and migrate towards functional databases as they mature.

The impact that visualizations play in faceted browsing systems deserves to be explored further. In systems such as DELVE, one interaction can have consequences in many parts of the interface. Ultimately, with a categorical model, one will be able to mathematically prove something is possible before implementation; the relationships and road maps between proof and implementation paths need to be researched further.

6 Conclusions

We extended our category-theoretic model of faceted browsing to support multiple heterogeneous terminologies as facets, which are needed in interfaces where more than one source of information controls the exploration of the data. Two use-cases emerged from our discussions of integrating multiple terminologies: merging instances into a single master and operation considerations when managing multiple facets.

We also showed that facets are categorically similar to database schemas, which allowed us to create instances of facets and faceted taxonomies and in turn support modeling heterogeneous terminologies as facets. Our model was previously demonstrated to encourage the reuse and interoperability of existing facet models [9], but the additional extensions presented also encourage the reuse of existing terminologies and provide a clear path to integrating them as controllable facets within a faceted browsing system.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through grant numbers UL1TR001998 and UL1TR000117. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Barr M, Wells C. Category theory for computing science. Prentice Hall; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodenreider O. The unified medical language system (umls): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32(suppl 1):D267–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray T. The javascript object notation (json) data interchange format. 2014 Mar; retrieved June 15, 2016 from https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7159/

- 4.Chu HJ, Chow RC. Information Reuse and Integration (IRI), 2010 IEEE International Conference on. IEEE; 2010. An information model for managing domain knowledge via faceted taxonomies; pp. 378–379. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CMS. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coecke B, Paquette ÉO. New Structures for Physics. Springer; 2011. Categories for the practising physicist; pp. 173–286. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson A, Brown D, Broughton V. Aslib proceedings: new information perspectives. Vol. 58. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2006. The need for a faceted classification as the basis of all methods of information retrieval; pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fagan JC. Usability studies of faceted browsing: a literature review. Information Technology and Libraries. 2013;29(2):58–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris DR. Information Reuse and Integration (IRI), 2015 IEEE International Conference on. IEEE; 2015. Modeling reusable and interoperable faceted browsing systems with category theory; pp. 388–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris DR. Foundations of reusable and interoperable facet models using category theory. Information Systems Frontiers. 2016;18(5):953–965. doi: 10.1007/s10796-016-9658-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris DR. Information Reuse and Integration (IRI), 2016 IEEE 17th International Conference on. IEEE; 2016. Modeling integration and reuse of heterogeneous terminologies in faceted browsing systems; pp. 58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris DR, Kavuluru R, Jaromczyk JW, Johnson TR. Proceedings of the summit on clinical research informatics. AMIA; 2017. Rapid and reusable text visualization and exploration development with delve. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris DR, Kavuluru R, Yu S, Theakston R, Jaromczyk JW, Johnson TR. Proceedings of the summit on clinical research informatics. AMIA; 2014. Delve: A document exploration and visualization engine; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hearst MA. Clustering versus faceted categories for information exploration. Communications of the ACM. 2006;49(4):59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hearst MA. SIGIR workshop on faceted search. ACM; 2006. Design recommendations for hierarchical faceted search interfaces; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karwin B. Pragmatic Bookshelf. 1. 2010. SQL antipatterns: avoiding the pitfalls of database programming. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kern EF, Maney M, Miller DR, Tseng CL, Tiwari A, Rajan M, Aron D, Pogach L. Failure of icd-9-cm codes to identify patients with comorbid chronic kidney disease in diabetes. Health services research. 2006;41(2):564–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowe HJ, Barnett GO. Understanding and using the medical subject headings (mesh) vocabulary to perform literature searches. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(14):1103–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy SN, Weber G, Mendis M, Gainer V, Chueh HC, Churchill S, Kohane I. Serving the enterprise and beyond with informatics for integrating biology and the bedside (i2b2) Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2010;17(2):124–130. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2009.000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niu X, Hemminger B. Analyzing the interaction patterns in a faceted search interface. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/asi.23227. [DOI]

- 21.Phillips S, Wilson WH. Categorial compositionality: A category theory explanation for the systematicity of human cognition. PLoS computational biology. 2010;6(7):e1000858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prieto-Díaz R. Information Reuse and Integration, 2003. IRI 2003. IEEE International Conference on. IEEE; 2003. A faceted approach to building ontologies; pp. 458–465. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spivak DI. Simplicial databases. 2009 arXiv preprint arXiv:0904.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spivak DI. Functorial data migration. Information and Computation. 2012;217:31–51. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spivak DI. Category Theory for the Sciences. MIT Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spivak DI, Giesa T, Wood E, Buehler MJ. Category theoretic analysis of hierarchical protein materials and social networks. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e23911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viegas FB, Wattenberg M, Feinberg J. Participatory visualization with wordle. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics. 2009;15(6):1137–1144. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2009.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wall HK, Hannan JA, Wright JS. Patients with undiagnosed hypertension: Hiding in plain sight. JAMA. 2014;312(19):1973–1974. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wattenberg M, Viégas FB. The word tree, an interactive visual concordance. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics. 2008;14(6):1221–1228. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2008.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei B, Liu J, Zheng Q, Zhang W, Fu X, Feng B. A survey of faceted search. Journal of Web engineering. 2013;12(1–2):41–64. [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization; 1992. The icd-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. [Google Scholar]