Abstract

Background

This study evaluated variations in root canal configuration in the maxillary permanent molars of Taiwanese patients by analyzing patients' cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) images. Comparisons were made among these configurations and those previously reported. This information may serve as a basis for improving the success rate of endodontic treatment.

Methods

The root canal systems of 114 Taiwanese patients with bilateral maxillary first or second molars were examined using CBCT images. The number of roots, canals per root, and additional mesiobuccal (MB) canals, as well as the canal configuration were enumerated and recorded.

Results

Of the 196 maxillary first molars examined, three (1.5%) had a single root, two (1.0%) had two roots, and 191 (97.5%) had three separate roots. Out of all first molar roots examined, 44% of mesiobuccal (MB) roots had a single canal and the remainder had a second MB (MB2) canal. Of the 212 maxillary second molars examined, 16 (7.1%) had a single root, 51 (24.2%) had two roots, 143 (67.8%) had three roots, and two (0.9%) had four separate roots. For the MB roots, 92.3% of three-rooted maxillary second molars had a single canal and the remainder had an MB2 canal. In all three-rooted maxillary first and second molars, each of the distal and palatal roots had one canal.

Conclusions

The root canal configurations of the MB roots of maxillary molars were more varied than those of the distobuccal and palatal roots, and the root canal configurations of maxillary second molars were more varied than those of the first molars. These findings demonstrate CBCT as a useful clinical tool for endodontic diagnosis and treatment planning.

Keywords: Cone beam computed tomography, Maxillary molars, Root canal system, Taiwan

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

The elucidation of the second mesiobuccal canal (MB2)'s anatomical structure in clinical practice is complex due to anatomical variations between individuals, as well as the excessive dentin deposition at the opening of the canal and the difficulty in visually accessing maxillary molars.

What this study adds to the field

In recent years, CBCT has made it possible to visualize the difficult-to-get-to anatomical structure in three dimensions, and it has now become a valuable tool for facilitating endodontic diagnosis and enabling treatment using a lower dose of radiation when compared to conventional computed tomography.

The thorough and complete debridement, disinfection, and obturation of the root canal system are essential for achieving successful root canal treatment. However, currently available imaging systems do not allow for three-dimensional visualization of the patient's root canal configuration during these procedures. This has resulted in incomplete debridement, disinfection, and obturation in some cases due to the failure to detect all of the patient's roots and canals. Therefore, to facilitate an accurate assessment of patients' root canal systems, clinicians should be aware of common root canal configurations and possible anatomical variations [1].

Because root canal anatomy is genetically determined, there may be similarities as well as variations in the patterns of root canal configuration among different populations. Ethnicity-related differences in root canal anatomy have been reported in many studies. Therefore, characterizing the root canal anatomy of a specific population and comparing the findings with those of other populations would be conducive to enhancing clinicians' understanding of population trends in the anatomy of the root canal system.

Maxillary molars are known to have the highest clinical failure rate in root canal treatment [2], [3], likely because of their complex root anatomy and canal morphology [1], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. According to published studies, most maxillary molars have three roots and four canals [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. The incidence of a second mesiobuccal (MB2) canal in the mesiobuccal (MB) root is higher than 50% [8], [9], [10], [11]. Other anatomical variations that have been reported include a third canal in the mesial root [12], more than one canal in the distobuccal and palatal roots [10], [11], and C-shaped canals [13].

Commonly used methodologies for evaluating the inner morphology of root canal systems include sectioning techniques, canal staining and tooth clearing [4], [14], [15], and acquisition of conventional and digital radiographs [16], [17], [18]. A recently developed imaging method, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), has been shown to provide accurate high-resolution three-dimensional anatomical images for diagnosis and treatment planning before endodontic treatment [19], [20]. Therefore, this imaging method has potential as a superior preoperative assessment for improving root canal treatment outcomes and avoiding further complications.

Numerous studies have used the CBCT method to investigate the canal morphology of maxillary molars. However, the root canal morphology of maxillary permanent molars in the Taiwanese population has not been investigated in this manner. This in vivo study therefore used CBCT imaging to analyze the number of roots and canals of maxillary first and second molars to categorize the presence of MB2 canals in the Taiwanese population.

Methods

Patients

A total of 67 women and 47 men were included in this study, with a mean age of 24.63 years (range: 18–64 years). CBCT images of 196 maxillary first molars and 212 maxillary second molars were obtained from these 114 participants between July 2014 and July 2015 at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. The images were taken as part of routine examination, diagnosis, and treatment planning for patients requiring orthodontic or orthognathic treatment or during preoperative assessment for dental implants. Patients' identities were not revealed; only information regarding gender and age was acquired. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Chang Gung Medical Foundation (protocol number: 201602003B0).

Teeth were selected according to the following criteria: (1) fully erupted permanent maxillary first molars or second molars bilaterally; (2) maxillary first or second molars with fully formed apexes and no previous root canal treatment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) CBCT images that were unclear or had artifacts; (2) maxillary first and second molars with root resorption or calcification, or crown restorations interfering with image analysis.

Image acquisition

All CBCT images were acquired using the i-CAT Cone Beam 3D Dental Imaging System (Image Sciences International, Hatfield, PA, USA). The image parameters were as follows: pixel size, 0.25 mm; slice thickness, 0.25 mm; tube voltage, 120 kVp; tube current, 36.12 mA/s; and acquisition period, 40 s. CBCT imaging was carried out by four licensed radiologists according to the ALARA radiation safety principle.

Image analysis

Reconstructed axial cross-sectional images were obtained using dental computed tomography software (i-CAT 3D Dental Imaging System) and examined in a dark room with a thin-film transistor monitor at a resolution of 1600 × 1200 pixels. All data were analyzed by two dentists between August 2015 and October 2015. Each of them had at least 5 years of clinical experience.

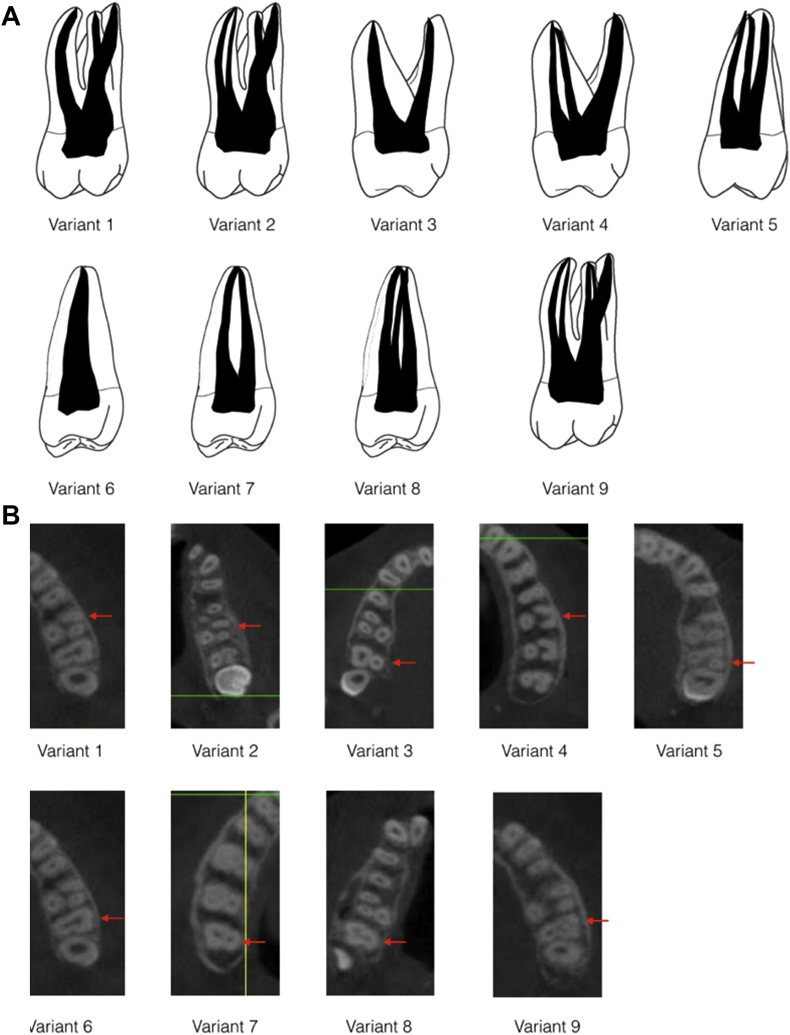

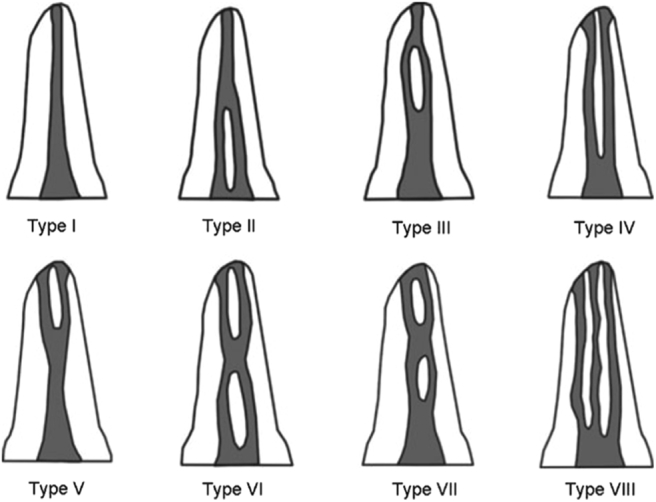

CBCT images of the teeth included in the study were examined and enumerated to determine the (1) number of roots, (2) number of canals per root, (3) root canal configurations using Vertucci's classification [Fig. 1], and (4) pattern of concurrence of anatomical variations in contralateral molars. The variants were classified as follows, similar to the classifications described in Zhang et al. [5] [Fig. 2]:

Variant 1: Three separate roots, comprising MB, distobuccal, and palatal roots, with one canal in each root.

Variant 2: Three separate roots, with one canal in each of the distobuccal and palatal roots and two canals in the MB root.

Variant 3: Two separate roots, comprising a buccal root and a palatal root, with one canal in each root.

Variant 4: Two separate roots, comprising a mesial root and a distal root, with one canal in each root.

Variant 5: Two separate roots, comprising a mesial root with two canals and a distal root with one canal.

Variant 6: One root with a single canal.

Variant 7: One root with two canals.

Variant 8: One root with three canals.

Variant 9: Three separate roots, with two canals in each the MB and distobuccal roots and one canal in the palatal root.

Fig. 1.

Vertucci's (1984) classification of the root canal system.

Fig. 2.

(A) Categorization of the nine variants in the maxillary molars; (B) CBCT images of the categorization of the nine variants in the maxillary molars.

Statistical analysis

The association between MB2 canal and gender was evaluated using Pearson's chi-square test. The test difference between MB2 canal and age was determined using Student's t-test for independent samples. SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used to conduct these statistical tests. A value of p < 0.05 was chosen as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

Number of roots and root morphology

Of the 196 maxillary first molars examined, three (1.5%) had a single root, two (1.0%) had two roots (a buccal and a palatal root) and 191 (97.5%) had three separate roots.

Of the 212 maxillary second molars examined, 16 (7.1%) had a single root, 51 (24.2%) had two roots (of which 14 had a mesial and a distal canal and 37 had a buccal and a palatal canal), 143 (67.8%) had three roots, and two (0.9%) had four separate roots.

Number of canals per root

In the three-rooted maxillary first molars, all of the distal and palatal roots had one canal. A total of 84 (44%) of the MB roots had a single canal, and the remainder had an MB2 canal. No statistically significant differences were found in the comparisons of the incidence of an MB2 canal with gender and age (p = 0.271 and p = 0.418, respectively).

In the maxillary second molars, when three separate roots were present, all of the distal and palatal roots had one canal. For the MB roots, 132 (92.3%) had a single canal and the remainder had an MB2 canal.

In the other maxillary second molars with one root, seven (53.9%) had one canal, and six (46.1%) had three canals.

Of the 53 two-rooted maxillary second molars, 23 (43.4%) had one canal in each of the two roots (buccal and palatal roots), 14 (26.4%) had two canals in the mesial root and one in the distal root, and 16 (30.2%) had two canals in the buccal root and one in the palatal root.

Although the incidence of MB2 canals was higher in men (58%) than in women (42%), this trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.812). On the other hand, the difference between the average age of subjects whose roots had MB2 canal (mean ± SD = 25.66 ± 11.07) and the average age of subjects whose MB roots had a single canal (mean ± SD = 36.17 ± 13.43) was statistically significant (p = 0.002).

Variations in the morphology of root canal systems

Of the maxillary first molars, 83 (42.3%) were classified as variant 1, 107 (54.6%) as variant 2, 3 (1.5%) as variant 8, 2 (1%) as variant 3, and 1 (0.5%) as variant 9. The distribution and percentage of the nine variants in root canal morphology are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution and percentage of the nine variants in root canal anatomy in the maxillary second molars.

| Variant |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Total | |

| Number | 133 | 11 | 26 | 13 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 212 |

| Percentage | 62.7 | 5.2 | 12.3 | 6.1 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 0 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 100 |

Root canal configuration of MB root analyses by Vertucci's classification

The root canal configurations of the MB root of maxillary first molars when MB2 is present were as follows: 15 (14%) type II, 75 (70%) type IV, and 17 (16%) type V.

The configurations of the MB root of maxillary second molars were as follows: 2 (18%) type II, 6 (58%) type IV, 2 (21%) type V, and 1 (3%) type VI.

Symmetry in the bilateral homonymous teeth

Of the 97 patients who had both bilateral homonymous maxillary first molars, 63 (65.0%) had perfect symmetry in the root and canal morphology of the contralateral homonymous teeth.

Among the 105 patients who had both bilateral homonymous maxillary second molars, 67 (63.8%) had perfect symmetry in the root and canal morphology of the contralateral homonymous teeth.

Discussion

This observational study characterized the root and canal anatomies of the maxillary first and second molars in the Taiwanese population based on the analysis of images captured using CBCT. It is generally recognized by clinicians that all of the maxillary first molars have three roots; however, the present findings indicate that this is not necessarily so, because five (2.5%) maxillary first molars did not have three roots. Our results corroborate previous findings in the Brazilian, Chinese, Ugandan, Indian, Irish, and South Korean populations, where not all of the patient populations' first molars have three roots [6], [7], [21], [22], [23], [24]. However, other studies conducted in the Thai, Kuwaiti, and Burmese populations and a Chinese subpopulation have revealed three separate roots in all maxillary first molars [4], [17], [25].

In our study, among the maxillary second molars, 144 (67.8%) had three separate roots, 51 (24.2%) had two roots, and 15 (7.1%) had one root. Furthermore, two (0.9%) second molars had four separate roots. These findings are consistent with those of Zhang et al. [5] (three separate roots: 82%, two roots: 9%, single root: 10%), al Shalabi et al. [22] (three separate roots: 85%, two roots: 15%) and Peikoff et al. [26] (four separate roots: 1.4%, three separate roots: 88.6%, two roots: 6.9%, single root: 3.1%), in that three separate roots is the standard anatomical form of maxillary second molars. Zhang et al., who sampled from a Chinese population, and al Shalabi et al., who sampled from an Irish population, had similar percentages of maxillary second molars with three separate roots. This finding does not appear to support al Shalabi et al.'s suggestion that root morphology may be determined by the ethnic background of the populations from which the samples were drawn. Additionally, the present study, which sampled from a Taiwanese population, had a relatively lower percentage of maxillary second molars with three separate roots than that of Zhang et al.

The incidence of root fusion was 32.0% in the maxillary second molars. The findings of this study indicate a higher incidence of root fusion than those reported in the Thai, Burmese, and Indian populations [4], [7], [25]; however, the results show similar incidences to those reported in the Chinese, South Korean, and Brazilian populations [6], [23], [27]. Compared with previous studies conducted on the Taiwanese population using the clearing and staining technique [28], the present study shows a lower but still similar incidence of root fusion. Although Chen et al., Yilmaz et al., and Kim et al. [29], [30], [31] have observed that other variants exist in root canal anatomy, these single-tooth variants were not focused upon and were detailed only in case reports. No C-shaped roots or canals were found in this study, in contrast to previous studies that have indicated a low incidence of C-shaped roots in the maxillary molars in a Chinese population [28]. However, the present study did not consider ethnic data, which is one of its methodological limitations.

Of all the roots of the maxillary first molars, the MB2 canal can be the most difficult to detect and negotiate in clinical situations. A total of 44% of the maxillary first molars had three roots and three canals, whereas 56.0% presented with three roots and four canals, with one canal in each of the distobuccal and palatal roots and two canals in the MB root. Several previous root canal morphology investigations using CBCT scans have shown similar results [5], [6], [7], [32]. The higher percentages found by other studies, ranging from 65% to 91% [4], [8], [33], relative to our findings, might be explained by differences in CBCT resolution, radiographic interpretation, definition of the second canal, and sample size. The CBCT image resolution of 250 μm was a limitation of this study. Ex vivo or in vitro studies on the incidence of MB2 canals have revealed a higher incidence of MB2 canals compared with in vivo studies [22], [25], [34]. Other studies using an operating microscope, clearing technique, or sectioning methodology have reported higher detection rates than those that have employed radiographic or CBCT examinations [9], [22], [25], [35]. Although in vitro studies achieve a higher detection rate of MB2 canals, they are carried out on extracted teeth, which may cause confusion for clinicians with regards to the original positions of the teeth. These in vitro studies are advantageous in that the root canal anatomies of the extracted teeth are not masked by the surrounding tissues and structures, thus enabling more accurate identification of the number of roots and canals in a tooth compared to in vivo studies. However, in vitro studies are time consuming, largely due to the complicated procedures required to prepare the teeth for examination. In addition, ex vivo studies have a high detection rate for MB2 canals, but have widely varying incidence rates ranging from 50% to more than 80%; this disparity may be attributable to ethnic differences [3], [22], [25], [34], [36], [37].

Patient age has previously been found to affect the detection rate of the MB2 canal. Neaverth et al. [38] found fewer canals in the MB roots of older patients, likely due to an increase in the level of calcification [38]. Consistent with this finding, in the present study, the detection rate for MB2 canals was found to be significantly and inversely associated with age (p < 0.05).

Regarding the effect of gender, a clearing study conducted by Sert and Bayirli [10] concluded that gender and race were important factors to consider in the preoperative evaluation of canal morphology for endodontic treatment. However, Neaverth et al. [38] and Zheng et al. [6] concluded that the gender of the patient was not associated with the number of MB root canals in the maxillary molars. Our results concurred with those of Neaverth et al. and Zheng et al.; we found that male and female patients had equal distributions of MB2 canals.

Anatomical variations in additional canals in the distobuccal and palatal roots of the maxillary first molars have been less frequently observed. In this study, a single canal was observed in each of the distobuccal and palatal roots in all three-rooted maxillary first molars. These findings are similar to those of previous studies that showed little variation in these roots [6], [22].

In the maxillary first molars, there were five variants in root canal anatomy; most were classified as variants 1 and 2. By contrast, eight variants were observed for the maxillary second molars, indicating a broader range of distribution for variant types. These findings indicate that maxillary second molars have a more complex root canal system than do maxillary first molars. The most common root canal anatomy of maxillary first molars was categorized as variant 2 (56%), with two canals in the MB root and one canal in each of the distobuccal and palatal roots. The most commonly observed root canal morphology of the maxillary second molars was three separate roots with one canal each (62.7%), categorized as variant 1; this prevalence was similar to that observed in previous studies [4], [5], [6], [7], [17], [21], [22], [25], [27], [32].

Among the observed MB2 canals, the most common canal configuration in the maxillary first and second molars was type IV, which is consistent with previous studies in the Thai and Chinese populations [4], [6].

Regarding the symmetry of bilateral homonymous teeth, in 65% of the maxillary first molars and 63% of the maxillary second molars, the root canal anatomy revealed bilateral symmetry. This is consistent with a previous study in Canada using traditional radiographs [26] and a study in a Chinese population using CBCT [6].

In the present study, MB2 canals were present in 56% of the maxillary first molars and 7.7% of the maxillary second molars. Although some studies employing microcomputed tomography [36] and the staining and clearing technique [22], [34] have been able to achieve higher detection rates (ranging from 52.3% to 78% and from 40% to 58%, respectively) than those of the present study, it should be noted that these studies were conducted in vitro on extracted human teeth. Among in vivo studies, our findings indicate a similar detection rate for MB2 canals in maxillary first molars compared to those found in a Chinese population (52.24% of mesiobuccal roots, 1.12% of distobuccal roots, and 1.76% of palatal roots) by Zheng et al. through CBCT [6]. In a Taiwanese population, Huang et al. [39] observed a higher incidence of the fourth canal in three-rooted mandibular first molars by using CBCT compared with previous studies using periapical radiographs. These findings demonstrate the superior quality of CBCT imaging and its clinical application in studying root canal morphology prior to clinical endodontic treatment. However, CBCT imaging should be applied only in cases with suspected complex anatomy or morphology. Clinicians should consider the ALARA principle, despite CBCT involving minimal ionizing radiation. In cases in which an unexpected canal anatomy or orifice cannot be found after access preparation, intraoperative CBCT is an excellent diagnostic tool, as recently proposed by Ball et al. [40].

Conclusions

The MB roots of maxillary molars in a Taiwanese population were found to have more variation in their canal system compared with other roots. The incidence of two canals in the MB roots in the first molars was higher than that of the second molars. The root and canal configuration of maxillary second molars were more variable than those of the first molars. These findings demonstrate the potential of CBCT as a useful clinical tool for endodontic diagnosis and treatment planning, and may also serve as a basis for improving the success of endodontic treatment.

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Weine F.S., Healey H.J., Gerstein H., Evanson L. Canal configuration in the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar and its endodontic significance. 1969. J Endod. 2012;38:1305–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartwell G., Appelstein C.M., Lyons W.W., Guzek M.E. The incidence of four canals in maxillary first molars: a clinical determination. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:1344–1346. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smadi L., Khraisat A. Detection of a second mesiobuccal canal in the mesiobuccal roots of maxillary first molar teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:e77–e81. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alavi A.M., Opasanon A., Ng Y.L., Gulabivala K. Root and canal morphology of Thai maxillary molars. Int Endod J. 2002;35:478–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang R., Yang H., Yu X., Wang H., Hu T., Dummer P.M. Use of CBCT to identify the morphology of maxillary permanent molar teeth in a Chinese subpopulation. Int Endod J. 2011;44:162–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Q.H., Wang Y., Zhou X.D., Wang Q., Zheng G.N., Huang D.M. A cone-beam computed tomography study of maxillary first permanent molar root and canal morphology in a Chinese population. J Endod. 2010;36:1480–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neelakantan P., Subbarao C., Ahuja R., Subbarao C.V., Gutmann J.L. Cone-beam computed tomography study of root and canal morphology of maxillary first and second molars in an Indian population. J Endod. 2010;36:1622–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J.H., Kim K.D., Lee J.K., Park W., Jeong J.S., Lee Y. Mesiobuccal root canal anatomy of Korean maxillary first and second molars by cone-beam computed tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:785–791. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baratto Filho F., Zaitter S., Haragushiku G.A., de Campos E.A., Abuabara A., Correr G.M. Analysis of the internal anatomy of maxillary first molars by using different methods. J Endod. 2009;35:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sert S., Bayirli G.S. Evaluation of the root canal configurations of the mandibular and maxillary permanent teeth by gender in the Turkish population. J Endod. 2004;30:391–398. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200406000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kottoor J., Velmurugan N., Sudha R., Hemamalathi S. Maxillary first molar with seven root canals diagnosed with cone-beam computed tomography scanning: a case report. J Endod. 2010;36:915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson D.B., Kjar K.S., Hartwell G.R. Three canals in the mesiobuccal root of a maxillary first molar: a case report. J Endod. 2005;31:400–402. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000148147.01937.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dankner E., Friedman S., Stabholz A. Bilateral C shape configuration in maxillary first molars. J Endod. 1990;16:601–603. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(07)80204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vertucci F.J. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:589–599. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Awawdeh L., Abdullah H., Al-Qudah A. Root form and canal morphology of Jordanian maxillary first premolars. J Endod. 2008;34:956–961. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weine F.S., Hayami S., Hata G., Toda T. Canal configuration of the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar of a Japanese sub-population. Int Endod J. 1999;32:79–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattanshetti N., Gaidhane M., Al Kandari A.M. Root and canal morphology of the mesiobuccal and distal roots of permanent first molars in a Kuwait population–a clinical study. Int Endod J. 2008;41:755–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel S. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: Part 2. Cone beam computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2009;42:463–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotton T.P., Geisler T.M., Holden D.T., Schwartz S.A., Schindler W.G. Endodontic applications of cone-beam volumetric tomography. J Endod. 2007;33:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durack C., Patel S. Cone beam computed tomography in endodontics. Braz Dent J. 2012;23:179–191. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402012000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rwenyonyi C.M., Kutesa A.M., Muwazi L.M., Buwembo W. Root and canal morphology of maxillary first and second permanent molar teeth in a Ugandan population. Int Endod J. 2007;40:679–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.al Shalabi R.M., Omer O.E., Glennon J., Jennings M., Claffey N.M. Root canal anatomy of maxillary first and second permanent molars. Int Endod J. 2000;33:405–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2000.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim Y., Lee S.J., Woo J. Morphology of maxillary first and second molars analyzed by cone-beam computed tomography in a Korean population: variations in the number of roots and canals and the incidence of fusion. J Endod. 2012;38:1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva E.J., Nejaim Y., Silva A.V., Haiter-Neto F., Cohenca N. Evaluation of root canal configuration of mandibular molars in a Brazilian population by using cone-beam computed tomography: an in vivo study. J Endod. 2013;39:849–852. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng Y.L., Aung T.H., Alavi A., Gulabivala K. Root and canal morphology of Burmese maxillary molars. Int Endod J. 2001;34:620–630. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peikoff M.D., Christie W.H., Fogel H.M. The maxillary second molar: variations in the number of roots and canals. Int Endod J. 1996;29:365–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva E.J., Nejaim Y., Silva A.I., Haiter-Neto F., Zaia A.A., Cohenca N. Evaluation of root canal configuration of maxillary molars in a Brazilian population using cone-beam computed tomographic imaging: an in vivo study. J Endod. 2014;40:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Z.P., Yang S.F., Lee G. The root and root canal anatomy of maxillary molars in a Chinese population. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1988;4:215–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1988.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen I.P., Karabucak B. Conventional and surgical endodontic retreatment of a maxillary first molar: unusual anatomy. J Endod. 2006;32:228–230. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yilmaz Z., Tuncel B., Serper A., Calt S. C-shaped root canal in a maxillary first molar: a case report. Int Endod J. 2006;39:162–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J.R., Choi S.B., Park S.H. A maxillary second molar with 6 canals: a case report. Quintessence Int. 2008;39:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vizzotto M.B., Silveira P.F., Arus N.A., Montagner F., Gomes B.P., da Silveira H.E. CBCT for the assessment of second mesiobuccal (MB2) canals in maxillary molar teeth: effect of voxel size and presence of root filling. Int Endod J. 2013;46:870–876. doi: 10.1111/iej.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reis A.G., Grazziotin-Soares R., Barletta F.B., Fontanella V.R., Mahl C.R. Second canal in mesiobuccal root of maxillary molars is correlated with root third and patient age: a cone-beam computed tomographic study. J Endod. 2013;39:588–592. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imura N., Hata G.I., Toda T., Otani S.M., Fagundes M.I. Two canals in mesiobuccal roots of maxillary molars. Int Endod J. 1998;31:410–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1998.0169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coutinho-Filho T.S.G.-F.E., Souza-Filho F.J., Silva E.J. Preliminary investigation to achieve patency of MB2 canal in maxillary molars. Braz J Oral Sci. 2012;11:373–376. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plotino G., Grande N.M., Pecci R., Bedini R., Pameijer C.H., Somma F. Three-dimensional imaging using microcomputed tomography for studying tooth macromorphology. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1555–1561. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weng X.L., Yu S.B., Zhao S.L., Wang H.G., Mu T., Tang R.Y. Root canal morphology of permanent maxillary teeth in the Han nationality in Chinese Guanzhong area: a new modified root canal staining technique. J Endod. 2009;35:651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neaverth E.J., Kotler L.M., Kaltenbach R.F. Clinical investigation (in vivo) of endodontically treated maxillary first molars. J Endod. 1987;13:506–512. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(87)80018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang C.C., Chang Y.C., Chuang M.C., Lai T.M., Lai J.Y., Lee B.S. Evaluation of root and canal systems of mandibular first molars in Taiwanese individuals using cone-beam computed tomography. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109:303–308. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ball R.L., Barbizam J.V., Cohenca N. Intraoperative endodontic applications of cone-beam computed tomography. J Endod. 2013;39:548–557. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]