Abstract

Background

Progesterone analogues, such as megestrol acetate (MA) and medroxyprogesterone (MPA), have been used for the palliative care of cancer cachexia for decades and have proven to increase body weight and improve quality of life and performance status. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of progesterone analogue use on quality of life in terms of pain control, performance status, body weight gain, and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) DNA load in recurrent/metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patients.

Methods

We retrospectively enrolled 41 patients with locally recurrent or metastatic NPC who received MA or MPA for cachexia management between January 2007 and February 2014. Patients who underwent aggressive treatment with intravenous chemotherapy were excluded. Body weight, performance status, pain score, and plasma EBV DNA load were used to assess quality of life before and after MA/MPA treatment.

Results

Of the 41 patients, 33 patients (80.5%) experienced body weight gain after progesterone analogue intervention. A significant reduction in plasma EBV DNA load was noted after progesterone analogue use (p < 0.001). In addition, median pain and Karnofsky performance scores were also significantly improved in progesterone analogue responders compared with non-responders (4 vs. 1 and 70 vs. 80, respectively; p = 0.004 and p < 0.001, respectively).

Conclusion

Progesterone analogues improve quality of life in terms of performance status, pain control, and plasma EBV DNA load in patients with locally recurrent/metastatic NPC under palliative care.

Keywords: Epstein–Barr virus, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Progesterone analogues, Cachexia, Quality of life

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Progesterone analogues had been used for the palliative care of cancer cachexia to improve quality of life. Plasma Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA load is a good indicator in monitoring nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) tumor status.

What this study adds to the field

Current studies demonstrated the responder of recurrent/metastatic NPC patients with cachexia status after receiving progesterone analogues treatment would have body weight gain and improved quality of life, daily performance, and pain control, and lowered down plasma EBV DNA load.

Cancer cachexia is a significant issue in head and neck cancer patients under palliative care. According to the international consensus, the diagnostic criterion for cachexia is body weight loss >5%, or body weight loss >2% in individuals with a body mass index (BMI) < 20 kg/m2 or depletion of skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) [1]. This syndrome is associated with decreased physical function [2], reduced tolerance to anticancer therapy [3], and shortened survival [4], [5]. Cachexia is responsible for up to 22% of cancer deaths [6]. The survival of patients with different cancer types is heavily influenced by significant body weight loss [4]. Compromised nutritional status is a key factor associated with diminished sense of general well-being and global quality of life (QoL) and impaired ability to repair tissue damage in head and neck cancer patients [7]. There is some evidence that appetite and body weight maintenance can affect the QoL of cancer patients [8]. However, only a few studies have investigated this relationship in patients with head and neck cancers [9], [10]. The correlation of eating behavior with body weight change is a complex phenomenon. Eating behavior may indirectly impact QoL by enhancing mood, increasing social relations via enjoying mealtime together with family and friends, and providing additional social support via celebrations with meals as the focal point.

Megestrol acetate (MA) and medroxyprogesterone (MPA) are orally active synthetic analogues of the natural steroid progesterone. MA, which was first synthesized in England in 1963, was originally developed as an oral contraceptive [11]. The observed anticancer effects of MA led to its clinical use for breast cancer treatment in 1967. Body weight gain after MA use was first noticed as an unexpected adverse effect in women with metastatic breast cancer. MA is now commonly used to increase appetite and body weight gain in cancer-associated anorexia. In September 1993, MA was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of anorexia, cachexia, or unexplained weight loss in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome-associated cachexia [11]. The definite mechanism of appetite stimulation and ensuing body weight gain by MA is still not well understood. However, MA may downregulate proinflammatory cytokines that are increased during cachexia, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1 [12], [13].

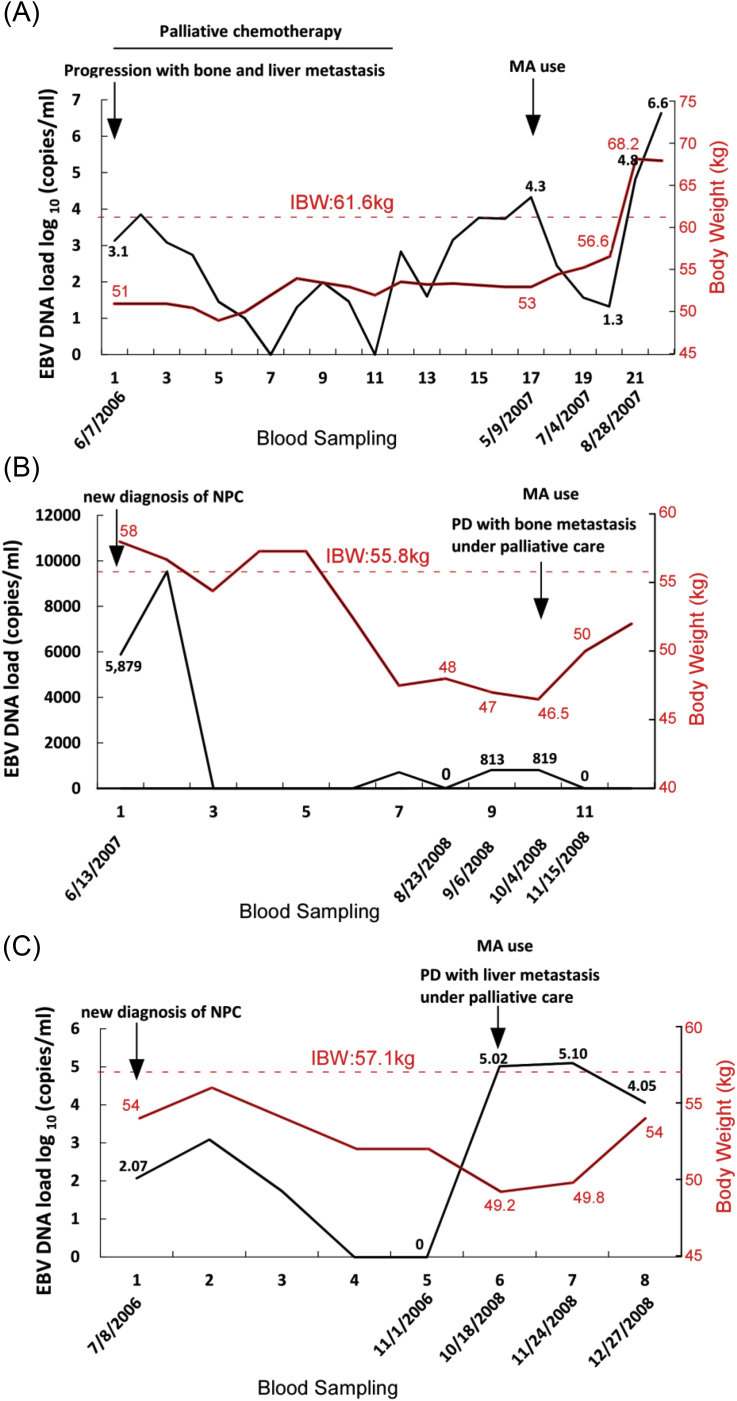

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is different from other head and neck cancers in terms of its epidemiology, histopathology, clinical characteristics, and treatment. It is an endemic, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated malignancy of epidermoid origin. Poorly differentiated and undifferentiated NPCs (World Health Organization type II and III) are associated with a higher incidence of neck lymph node metastasis and greater sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy [14]. EBV infection is especially associated with undifferentiated NPC and may specifically contribute to the pathogenesis of this cancer type [15], [16], [17]. With the advent of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR) technology, circulating plasma cell-free EBV DNA can be detected in more than 95% of NPC patients [18]. Previous studies have demonstrated a strong association between the circulating plasma cell-free EBV DNA level and disease status, tumor recurrence, and survival after radiotherapy [19], [20], [21], [22]. Tumor cells have been postulated to release EBV DNA directly into the circulation. Thus, the circulating plasma cell-free EBV DNA level may reflect tumor load and microscopic residual disease after radiotherapy in NPC patients [23]. In clinical practice, we noticed that progesterone analogue use decreased plasma EBV DNA titer and gradually increased body weight gain in cachectic patients with recurrent/metastatic NPC (Fig. 1). Previous studies have proven that plasma EBV DNA titer is a marker of tumor burden in NPC patients under supportive care [18], [22], [23], [24].

Fig. 1.

Correlation of plasma EBV DNA load with body weight change in patients undergoing megestrol acetate (MA; Megest) intervention. (A) Case 1. A 43-year-old man was diagnosed with NPC (T3N2M0) in 4/2005. He started palliative chemotherapy (gemcitabine + cisplatin regimen) for disease progression with bone and liver metastasis on 10/25/2006. He stopped chemotherapy on 2/24/2007 because of disease progression and treatment-related side effects and accepted supportive care. He underwent MA treatment from 5/23/2007 to 10/24/2007 and expired from liver failure with ascites in 1/2008. (B) Case 2. A 48-year-old woman was diagnosed with NPC (T4N2M0) in 6/2007. She underwent palliative care for disease progression with bone metastasis in 10/2008 and received MA from 1/11/2008 until 3/21/2009. (C) Case 3. A 61-year-old man was diagnosed with NPC (T4N2M0) in 8/2006. He received MA for the palliative treatment of disease progression with liver metastasis from 11/1/2008 to 12/26/2009 and expired in 3/2010. IBW, ideal body weight; PD, progressive disease.

We speculate that progesterone analogue use improves appetite in recurrent/metastatic NPC patients under supportive care by enhancing eating behavior, which indirectly influences global QoL by affecting patient behaviors, feelings, and perceptions [7]. Furthermore, plasma EBV DNA load might be a potential indicator of progesterone analogue treatment response in these patients. We conducted a retrospective study to validate our speculations.

Methods

Patients

A total of 41 patients with locally recurrent or metastatic NPC who received MA or MPA for cachexia management at the Oncology Department of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Linkou, Taiwan) between January 2007 and February 2014 were retrospectively enrolled in the study. Patients from a parallel-group prospective study of EBV DNA load in NPC [22] were included. Patients undergoing active cancer treatment with intravenous chemotherapy were excluded. Oral uracil-tegafur (UFT) maintenance therapy was acceptable in patients who experienced previous treatment failures with UFT-containing combination chemotherapy. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥18 years; biopsy-proven NPC, locally recurrent or metastatic disease proven by biopsy or at least two imaging studies, and body weight loss >5% in the past 12 months. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, and all participating patients provided written informed consent.

We analyzed body weight change before and after progesterone analogue (MA or MPA) intervention. Patients were divided into 2 groups according to their body weight change during the 2-week evaluation: responder (body weight gain at any scale in a 2-week interval after progesterone intervention) and non-responder (no body weight change or body weight loss after progesterone use). We specifically chose 2 weeks as regular clinic follow-up interval because we need to observe the response of symptomatic control medication and modify if indicated, especially when those patients underwent opioid and progesterone analogue use.

Study instruments

The Karnofsky performance status rating scale [25]

This scoring system was designed to measure patient activity level and medical care requirements. It is a general measure of patient independence and has been widely used for the general assessment of cancer patients. The Karnofsky scoring system ranges from 0 (“dead”) to 100 (“normally functioned”) points.

The numeric rating scale (NRS) for pain [26]

The NRS, which allows patients to rate their current pain intensity on a scale of 0 (“no pain”) to 10 (“worst possible pain”), has become the most widely used instrument for pain screening.

EBV DNA titer [18]

Whole blood was collected from patients and healthy volunteers (controls) before MA/MPA treatment. Blood (10 ml) was collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-treated tubes and centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 min. The plasma was removed and stored at −70 °C until testing. Plasma DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Blood MiniKit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). The plasma sample (approximately 500–1000 μl) was applied to the extraction column, and DNA was eluted from the column using 80 μl distilled water. EBV DNA concentrations were measured by Q-PCR of the BamHI-W region of the EBV genome [18]. Primer and probe sequences, including the dual fluorescence-labeled oligomer, and the detailed procedure have been described previously [21].

Procedures

Recurrent/metastatic NPC patients with cachexia were given MA (400 mg daily) (Megest; TTY Biopharm Co., Taiwan) or MPA (500 mg daily) (Farlutal; Pfizer, Taiwan) with palliative intent. All patients underwent a complete history and physical examination before study entry. A history of the patient's body weight, BMI, and ideal body weight (IBW) was obtained from the medical record and patient. Baseline weight was obtained at study entry. Body weight was routinely recorded at each clinic visit every 2 weeks. NRS pain and Karnofsky performance status scores were routinely assessed by clinicians during progesterone analogue intervention. Progesterone analogue use was discontinued in the following situations: occurrence of adverse effects such as diuretic-refractory edema or thromboembolic event; the body weight was beyond the IBW; and treatment failure with continuous body weight loss or no body weight gain despite progesterone analogue use for at least 4 weeks. The duration of progesterone analogue response was calculated as the body weight gain duration. EBV DNA was checked routinely at 1–3-month intervals.

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test or chi-square test was used to compare categorical data. Continuous data were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Parameters were compared before and after progesterone analogue treatment using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The duration of progesterone analogue response was calculated as described in “Procedures”. Overall survival was calculated from the date of study entry to the date of death from any cause and was censored on the date of the last follow-up the patient was known to be alive. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

Results

Patients, treatment, and outcome

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age of the 41 patients was 48.9 years (range, 27–73 years). The median age of patients in the progesterone analogue responder and non-responder groups was 47.1 and 56.4 years, respectively. Twenty-six patients (63.4%) were male. Most patients (35/41, 85.4%) were diagnosed with undifferentiated carcinoma, and 4 out of 41 patients (9.8%) were diagnosed with non-keratinizing carcinoma. Eleven patients (26.8%) had local recurrence, and 30 patients (73.2%) had distant metastasis. Twenty-three patients (56.1%) were under oral UFT chemotherapy. The median duration of progesterone analogue response was 8 weeks.

Table 1.

Characteristics of recurrent/metastatic NPC patients under supportive care with progesterone analogues.

| Responder (n = 33) |

Non-responder (n = 8) |

Total (n = 41) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Range | 29–67 | 27–73 | 27–73 |

| Median | 46 | 59 | 47 |

| Sex | |||

| Male, n (%) | 20 (60.6) | 6 (75) | 26 (63.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (39.4) | 2 (25) | 15 (36.6) |

| Pathology | |||

| UDC, n (%) | 28 (87.5) | 7 (77.8) | 35 (85.4) |

| NKC, n (%) | 3 (9.4) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (9.8) |

| SqCC, n (%) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (4.8) |

| Survival (Recurrence/Metastasis to Death) (months) | |||

| Range | 2–66 | 2–62 | 2–66 |

| Median | 21 | 13 | 17 |

| Recurrence | |||

| Local, n (%) | 6 (18.2) | 5 (62.5) | 11 (26.8) |

| Distant, n (%) | 27 (81.8) | 3 (37.5) | 30 (73.2) |

| Oral palliative chemotherapy | |||

| None, n (%) | 14 (42.4) | 4 (50) | 18 (43.9) |

| UFT, n (%) | 19 (57.6) | 4 (50) | 23 (56.1) |

| Progesterone analogue treatment duration (weeks) | 8 (2–24) | 5.5 (3–20) | 8 (2–24) |

Abbreviations: NKC: non-keratinizing carcinoma; SqCC: squamous cell carcinoma; UDC: undifferentiated carcinoma; UFT: uracil-tegafur.

Change in weight

A significant increase in body weight was observed after progesterone analogue use (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Most patients (33/41, 80.5%) experienced body weight gain after progesterone analogue intervention.

Table 2.

Clinical parameter changes before and after progesterone analogue treatment.

| Progesterone analogue treatment, Median (range) |

p valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| before | after | ||

| Body weight (kg) | 53 (36.9–82.0) | 55 (43.8–85.0) | <0.001 |

| Performance status | |||

| All (n = 41) | 70 (40–90) | 80 (40–90) | <0.001 |

| Responder (n = 33) | 70 (40–90) | 80 (50–90) | |

| Non-responder (n = 8) | 70 (60–90) | 70 (40–90) | |

| Pain score | 4 (0–9) | 1 (0–9) | 0.004 |

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Change in Karnofsky performance status score

Kanofsky performance status scores significantly improved from 70 before progesterone analogue use to 80 after progesterone analogue use (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Change in NRS pain score

Median NRS pain score significantly improved from 4 before progesterone analogue use to 1 after progesterone analogue use (p = 0.004) (Table 2).

Change in plasma EBV DNA load

Decreased plasma EBV DNA load was observed in 19 patients (46.3%). Plasma EBV DNA load was significantly decreased after progesterone analogue treatment (p < 0.001) (Table 3). EBV DNA load was decreased in 17 out of 33 responders (51.5%) and increased in 4 out of 8 non-responders (50%).

Table 3.

Change in plasma EBV DNA titer in responders and non-responders.

| Plasma EBV DNA (copies/ml) |

Responder (n = 33) |

Non-responder (n = 8) |

Total (n = 41) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease, n (%) | 17 (51.5) | 2 (25) | 19 (46.3) |

| Stable, n (%) | 6 (18.2) | 2 (25) | 8 (19.5) |

| Increase, n (%) | 10 (30.3) | 4 (50) | 14 (34.1) |

Discussion

A review of the literature has shown that progesterone analogues improve QoL in terms of body weight gain and performance status in cancer patients with cachexia [2], [7]. In our study, we obtained similar improvements in QoL including enhanced performance status and body weight gain with progesterone analogue treatment in recurrent/metastatic NPC patients under supportive care. We also found that plasma cell-free EBV DNA titer and pain score were also significantly decreased after progesterone analogue use.

Cancer cachexia significantly influences treatment response, performance status, survival, and QoL [27]. Previous studies have shown that MA use enhances food intake in both rodents and humans [28], [29]. Although the definite mechanism for the increased food intake is still not thoroughly understood, it is thought to be associated with increased production of neuropeptide Y, a potent central appetite stimulant [30]. Furthermore, MA can decrease the production of serotonin and cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α) [31], which are highly related to anorexia-associated catabolism. Studies have shown that body weight maintenance is a common issue in cancer patients, especially those with NPC, and is heavily influenced by previous long-term radiotherapy-related complications and structural deformities [9]. Nutritional status plays a key role in the maintenance of QoL in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NPC under palliative treatment. In the present study, progesterone analogue treatment substantially increased body weight and improved performance status, which is a surrogate marker of QoL, in recurrent/metastatic NPC patients.

The effect of progesterone analogue use on pain control of cancer cachexia was especially emphasized in our study. In previous studies, pain control was simply evaluated using a questionnaire [7], [27]. In our study, we found that progesterone analogue use significantly improved pain control as evidenced by the decrease in median NRS pain score (4–1). Furthermore, the percentage of patients in the responder group who received opioids for pain control was reduced from 55% (18/33) to 40% (13/33) after progesterone analogue treatment. Improved pain control can lead to the avoidance of unnecessary adverse effects, such as constipation, dizziness, and nausea/vomiting. In addition to improved pain control, performance status was also improved. Overall, these positive changes improved QoL. However, the definite mechanism by which progesterone analogues improve pain control is still not clear. We assume that this mechanism involves a progesterone analogue and cytokine interaction. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanism by which progesterone analogues improve pain control of cancer cachexia.

Previous studies have shown the plasma free-cell EBV DNA is a good tumor marker for NPC, with high sensitivity and specificity [22], [32]. Mutirangura et al. demonstrated the correlation between tumor DNA and EBV DNA in NPC patients [33]. Lin et al. further proved the strong correlation between plasma EBV DNA and primary tumor burden in NPC [24]. In the present study, we noticed that some patients with gradual body weight gain after progesterone analogue treatment had decreased plasma EBV DNA titers. A significant decrease in plasma EBV DNA was noted in progesterone analogue responders. This suggests that progesterone analogue responders have a relatively stable tumor status compared with non-responders. Furthermore, body weight gain and performance status improvement may be associated with decreased EBV DNA titer.

Part (56.1%) of our patients were under oral UFT (Tegafur-uracil) treatment, an oral preparation combining tegafur (5-fluorouracil prodrug) and uracil in a 1:4 ratio. Although 5-fluouracil monotherapy in nasopharyngeal cancer can reach overall response rate 13% [34]. Sincerely, we didn't know the exact anti-tumor effect of UFT with progesterone analogues in our responders. However, due to previous chemotherapy(s), including fluorouracil-based regimen, failed, we expected that oral UFT has limited anti-tumor efficacy as placebo purpose predominantly. Therefore, we tried to analyzed patients under palliative oral UFT and without UFT using. 15/18 (83.3%) patients without UFT use responded to megace use with decreased or stable plasma EBV DNA load and similar proportion (18/23, 78.3%) of responders was noted among patients under UFT treatment. Furthermore, plasma EBV DNA titer change doesn't influence by oral UFT use or not (p = 1.000) (Table 4). Therefore, we didn't exclude patients under palliative oral UFT treatment.

Table 4.

Palliative oral UFT effect on plasma EBV DNA change.

| Plasma EBV DNA (copies/ml) |

Decrease or stable | Increase | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral UFT | |||

| Yes, n = 23 (%) | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | 1.000 |

| No, n = 18 (%) | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | |

Statistic analysis: Fisher's exact test.

The strength of our study is the groundbreaking finding of the relationship between plasma EBV DNA titer and progesterone analogue treatment response. Furthermore, we show that pain control can be used as a new parameter to assess QoL in cancer patients with cachexia. However, our study has some limitations. The major limitation of our study is its retrospective design. Second, data was collected from a single institution. Third, the study was limited by its small sample size, and 56.1% of patients were receiving palliative treatment with UFT, which might influence the interpretation of results. In addition, patients were treated in a supportive care setting and thus, a follow-up of disease status was not performed. Therefore, prospective multi-institutional or nationwide studies are needed to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, progesterone analogues, such as MPA and MA, can improve QoL by enhancing performance status and improving pain control in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NPC under palliative care. In addition, plasma EBV DNA titer was significantly decreased after progesterone analogue treatment, especially in patients with body weight gain (progesterone analogue responders), which may be related to stable tumor status. Further studies are necessary to understand the mechanisms by which progesterone analogues improve pain control and EBV DNA load in NPC.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan, ROC, grant number: CMRPG360251-3, CMRPG391381-3, CMRPG3C1931, CMRPG3E1221.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Fearon K., Strasser F., Anker S.D., Bosaeus I., Bruera E., Fainsinger R.L. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moses A.W., Slater C., Preston T., Barber M.D., Fearon K.C. Reduced total energy expenditure and physical activity in cachectic patients with pancreatic cancer can be modulated by an energy and protein dense oral supplement enriched with n-3 fatty acids. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:996–1002. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann J., Heiligensetzer M., Krakowski-Roosen H., Buchler M.W., Friess H., Martignoni M.E. Cachexia worsens prognosis in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1193–1201. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0505-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewys W.D., Begg C., Lavin P.T., Band P.R., Bennett J.M., Bertino J.R. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med. 1980;69:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(05)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fearon K.C., Voss A.C., Hustead D.S. Definition of cancer cachexia: effect of weight loss, reduced food intake, and systemic inflammation on functional status and prognosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1345–1350. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren S. The immediate causes of death in cancer. Am J Med Sci. 1932;184:610–615. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McQuellon R.P., Moose D.B., Russell G.B., Case L.D., Greven K., Stevens M. Supportive use of megestrol acetate (Megace) with head/neck and lung cancer patients receiving radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1180–1185. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donohoe C.L., Ryan A.M., Reynolds J.V. Cancer cachexia: mechanisms and clinical implications. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:13. doi: 10.1155/2011/601434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H.C., Leung S.W., Wang C.J., Sun L.M., Fang F.M., Hsu J.H. Effect of megestrol acetate and prepulsid on nutritional improvement in patients with head and neck cancers undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 1997;43:75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)01921-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couch M., Lai V., Cannon T., Guttridge D., Zanation A., George J. Cancer cachexia syndrome in head and neck cancer patients: part I. Diagnosis, impact on quality of life and survival, and treatment. Head Neck. 2007;29:401–411. doi: 10.1002/hed.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz Garcia V., Lopez-Briz E., Carbonell Sanchis R., Gonzalvez Perales J.L., Bort-Marti S. Megestrol acetate for treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004310.pub3. CD004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh S.S., Wu S.Y., Levine D.M., Parker T.S., Olson J.S., Stevens M.R. The correlation of cytokine levels with body weight after megestrol acetate treatment in geriatric patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M48–M54. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.1.m48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh S.S., Schuster M.W. Geriatric cachexia: the role of cytokines. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:183–197. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.70.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teo P.M., Chan A.T. Treatment strategy and clinical experience. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:497–504. doi: 10.1016/s1044579x02000925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathmanathan R., Prasad U., Chandrika G., Sadler R., Flynn K., Raab-Traub N. Undifferentiated, nonkeratinizing, and squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Variants of Epstein-Barr virus-infected neoplasia. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1355–1367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathmanathan R., Prasad U., Sadler R., Flynn K., Raab-Traub N. Clonal proliferations of cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus in preinvasive lesions related to nasopharyngeal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:693–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509143331103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tune C.E., Liavaag P.G., Freeman J.L., van den Brekel M.W., Shpitzer T., Kerrebijn J.D. Nasopharyngeal brush biopsies and detection of nasopharyngeal cancer in a high-risk population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:796–800. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.9.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo Y.M., Chan L.Y., Lo K.W., Leung S.F., Zhang J., Chan A.T. Quantitative analysis of cell-free Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1188–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo Y.M., Chan A.T., Chan L.Y., Leung S.F., Lam C.W., Huang D.P. Molecular prognostication of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by quantitative analysis of circulating Epstein-Barr virus DNA. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6878–6881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo Y.M. Quantitative analysis of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma and serum: applications to tumor detection and monitoring. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;945:68–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu C.L., Chang K.P., Lin C.Y., Chang H.K., Wang C.H., Lin T.L. Plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA concentration and clearance rate as novel prognostic factors for metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2012;34:1064–1070. doi: 10.1002/hed.21890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu C.L., Chan S.C., Chang K.P., Lin T.L., Lin C.Y., Hsieh C.H. Clinical scenario of EBV DNA follow-up in patients of treated localized nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan A.T., Lo Y.M., Zee B., Chan L.Y., Ma B.B., Leung S.F. Plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA and residual disease after radiotherapy for undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1614–1619. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.21.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin J.C., Wang W.Y., Chen K.Y., Wei Y.H., Liang W.M., Jan J.S. Quantification of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2461–2470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schag C.C., Heinrich R.L., Ganz P.A. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:187–193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krebs E.E., Carey T.S., Weinberger M. Accuracy of the pain numeric rating scale as a screening test in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1453–1458. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreyev H.J., Norman A.R., Oates J., Cunningham D. Why do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for gastrointestinal malignancies? Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:503–509. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Von Roenn J.H., Armstrong D., Kotler D.P., Cohn D.L., Klimas N.G., Tchekmedyian N.S. Megestrol acetate in patients with AIDS-related cachexia. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:393–399. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-6-199409150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loprinzi C.L., Schaid D.J., Dose A.M., Burnham N.L., Jensen M.D. Body-composition changes in patients who gain weight while receiving megestrol acetate. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:152–154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy H.D., Crowder R.E., Dryden S., Williams G. Megestrol acetate stimulates food and water intake in the rat: effects on regional hypothalamic neuropeptide Y concentrations. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;265:99–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mantovani G., Maccio A., Lai P., Massa E., Ghiani M., Santona M.C. Cytokine involvement in cancer anorexia/cachexia: role of megestrol acetate and medroxyprogesterone acetate on cytokine downregulation and improvement of clinical symptoms. Crit Rev Oncog. 1998;9:99–106. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v9.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens N.A., Skipworth R.J., Fearon K.C. Cachexia, survival and the acute phase response. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2008;2:267–274. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283186be2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mutirangura A., Pornthanakasem W., Theamboonlers A., Sriuranpong V., Lertsanguansinchi P., Yenrudi S. Epstein-Barr viral DNA in serum of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:665–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs C., Lyman G., Velez-Garcia E., Sridhar K.S., Knight W., Hochster H. A phase III randomized study comparing cisplatin and fluorouracil as single agents and in combination for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:257–263. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]