Abstract

Background

Thyroid hormones are known to affect energy metabolism. Many patients of metabolic syndrome have subclinical or clinical hypothyroidism and vice versa. To study the correlation of thyroid profile and serum lipid profile with metabolic syndrome.

Method

It is a hospital based cross sectional case-control study carried out in tertiary care health center, we studied thyroid functions test and serum lipid profile in 100 metabolic syndrome patients according to IDF criteria and a similar number of age, gender and ethnicity matched healthy controls.

Result

We found that serum HDL was significantly lower (p < 0.001) in cases (41.28 ± 8.81) as compared to controls (54.00 ± 6.31). It was also found that serum LDL, VLDL, triglyceride levels and total cholesterol were found to be significantly higher (p < 0.001) in cases than controls. Serum TSH levels of subjects in cases group (3.33 ± 0.78) were significantly higher (p < 0.001) than that of controls (2.30 ± 0.91) and significantly lower levels of T4 (p < 0.001) in the patients of metabolic syndrome (117.45) than in controls (134.64) while higher levels of T3, although statistically insignificant in the patients of metabolic syndrome.

Conclusion

Thyroid hormones up-regulate metabolic pathways relevant to resting energy expenditure, hence, obesity and thyroid functions are often correlated.

Keywords: Thyroid hormones, Metabolic syndrome, Serum lipid profile

At a glance commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Obesity per se causes alterations in thyroid hormones, i.e. increased thyroid hormone levels, increased TSH with no effect on T3 and T4, or increase in TSH and T3 with no effect on T4; on the other hand, subclinical hypothyroidism as a result of slow metabolism can lead to the obesity.

What this study adds to the field

The mechanism of normal levels of T3, T4 with increased TSH in metabolic syndrome is not defined, but it has been hypothesized that metabolic syndrome is associated with insulin resistance due to the defect in postreceptor signal transduction in target tissue, a similar mechanism of thyroid receptor resistance might be operating in these obese persons.

Obesity, a key component of metabolic syndrome, occurs due to increased energy intake, decreased energy expenditure, or a combination of both, thus leading to positive energy balance. Thyroid hormones up-regulate metabolic pathways relevant to resting energy expenditure, hence, obesity and thyroid functions are often correlated. On one hand, obesity per se causes alterations in thyroid hormones, i.e. increased thyroid hormone levels [1], increased TSH (Thyroid-stimulating hormone) with no effect on T3 (Triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine), [2] or increase in TSH and T3 with no effect on T4, [3] on the other hand, subclinical hypothyroidism as a result of slow metabolism can lead to the obesity [4]. The mechanism of normal levels of T3, T4 with increased TSH in metabolic syndrome is not defined, but it has been hypothesized that metabolic syndrome is associated with insulin resistance due to the defect in post receptor signal transduction in target tissue; a similar mechanism of thyroid receptor resistance might be operating in these obese persons [2]. It is still not clear whether alterations in thyroid hormones are a cause or an effect of obesity (metabolic syndrome) suggesting need for further evaluation on a large scale with inclusion of various hormones elaborated by adipose tissue (like, leptin, resistin, adiponectin, etc). There are various studies on thyroid functions in patients with metabolic syndrome but there is a scarcity of studies on the issue from northern India.

Material and methods

Study design

The present study was conducted in the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, in tertiary care health center in northern part of India, it is a hospital based cross sectional case-control study, to study the correlation of thyroid function and serum lipid with metabolic syndrome.

Study population

Patients attending the outpatient department (OPD) of Endocrinology and Metabolism department were included in the present study (n = 200).

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Subjects who fulfilled the IDF (International Diabetic Federation) criteria for metabolic syndrome were grouped under cases.

-

2

Subjects who gave written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Subjects who are a known case of any psychiatric illness.

-

2.

Patients suffering from any major medical or surgical illness.

-

3.

Patients on medications affecting thyroid profile and serum lipids.

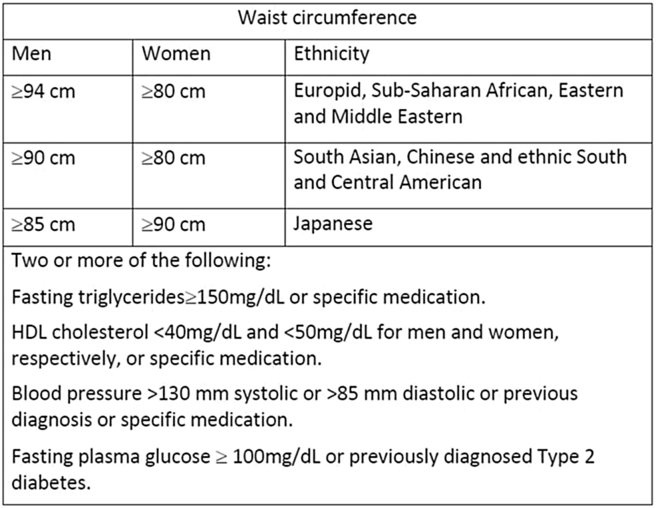

IDF criteria for metabolic syndrome [5] [Fig. 1]

Fig. 1.

IDF criteria for metabolic syndrome.

We chose to follow the IDF criteria over NCEP: ATP III (National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III) because the IDF criteria takes into account the variation of ethnicity while ATP III is applicable mainly to the American population.

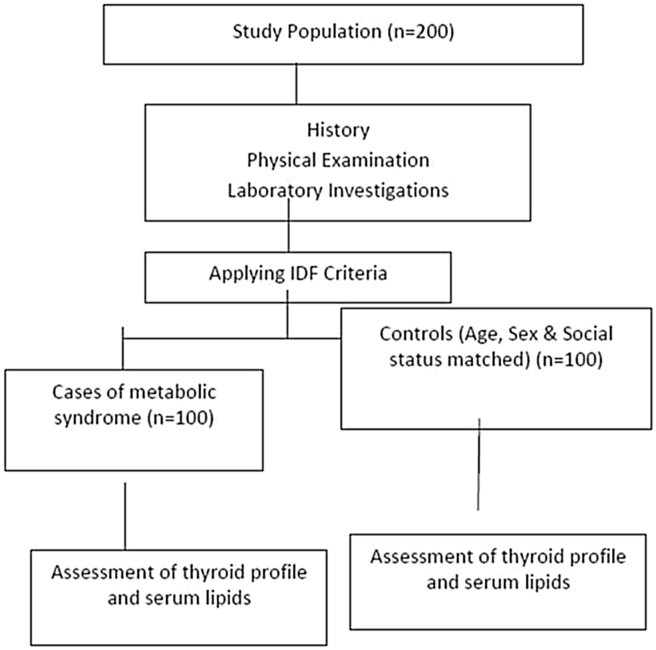

PROTOCOL of the study shown in Fig. 2

Fig. 2.

Study protocol.

The first 100 patients attending OPD of department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, who were fitting in the IDF criteria for metabolic syndrome, were enrolled as cases after taking their consent for the study. Then, the same number of controls was included after matching their age, sex and social status with cases.

History

Information on age, sex and occupation and past history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was obtained by self report.

Examination

Body weight to the nearest 1 kg and standing height to nearest 1 cm were measured using a manual scale and standard measuring tape. Trained physician or technicians measured waist circumference to the nearest 1 cm using standard measuring tape at the level of mid-line between inferior border of ribs and superior border of iliac crest (as per IDF guidelines).

Blood pressure was measured by trained physician after 5 min rest in right arm sitting position with a mercury sphygmomanometer.

Goiter was assessed, and graded as per the WHO grading system. Anti TPO antibody (Anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies) were not done in patients with metabolic syndrome because of financial reasons.

Blood collection and measurement of biochemical variables

All the blood samples were collected by 8–10 h overnight fast in the morning. Serum HDL (High Density Lipoprotein) – Cholesterol, Triglycerides, LDL (Low Density Lipoprotein) – Cholesterol, Total Cholesterol was measured using enzymatic method as instructed in information sheets. Plasma glucose was measured using Enzymatic (GOD-POD) method. T3 (1.3–3.1 nmol/l), T4 (66–181 nmol/l), TSH (0.270–4.20 μIU/ml) were measured using ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were summarized as Mean ± SD while discrete (categorical) in number and percentage. Continuous two independent groups were compared by parametric independent student's t test and the significance of parametric t test was also validated with nonparametric alternative Mann–Whitney U test, where appropriate. Discrete (categorical) groups were compared by chi-square (χ2) test. A two-sided (α = 2) p values less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed on STATISTICA software (Windows version 6.0).

Result

The present study was undertaken in the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, to find out the correlation between thyroid profile and metabolic syndrome in patients of Metabolic Syndrome and compare it with healthy controls. The study was approved by the ethics committee. One hundred patients attending Endocrinology and Metabolism OPD from August 2012 to July 2013 who fulfilled the criteria of metabolic syndrome as per IDF guidelines were included in the study as cases and an equal number of age, gender and social status matched controls were included. Informed consent was taken before the start of study from patients.

Table 1 showed the age of total study population ranged from 18 to 60 years. In Control group mean age of subjects was 38.77 ± 9.94 (range – 18–57) years whereas in Case group mean age of subjects was 38.10 ± 10.33 (range – 19–60) years. Majority of patients in both the groups were between age groups 31–50 years. Statistically, there was no significant difference between two groups with respect to age. The distribution of subjects in two groups according to gender: In both the groups, majority of subjects were females. There were 64 (64%) females and 36 (36%) males in both control and case group. The present study was a case-control study, to exclude any age or gender bias, an attempt was made to include controls of similar age and gender as of controls. Groups matched perfectly according to age and gender.

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution of subjects.

| Age group (years) | Cases (n = 100) | Controls (n = 100) |

|---|---|---|

| Upto 20 | 2 | 2 |

| 21–30 | 22 | 22 |

| 31–40 | 34 | 34 |

| 41–50 | 31 | 31 |

| 51–60 |

11 |

11 |

| Gender |

Cases (n = 100) |

Controls (n = 100) |

| Female | 64 | 64 |

| Male | 36 | 36 |

Table 2 shows distribution of subjects in two groups according to presence of different factors contributing to metabolic syndrome: In case group, all (100%) subjects had central obesity, 84% had raised blood pressure and 47% had raised fasting plasma glucose, a total of 83 (83%) had raised triglycerides and 76% had reduced HDL cholesterol. In control group, a total of 29 (29%) subjects fulfilled the IDF criteria for central obesity (Males >90 cm, Females >80 cm), 32% had raised blood pressure (>130/85 SBP/DBP or known hypertensive) and only 1 had raised fasting plasma glucose (>100 mg/dL or known diabetic), a total of 2 had raised triglyceride levels (≥150 mg/dL) and 8% had reduced HDL cholesterol (Males ≤ 40 mg/dL, Females ≤ 50 mg/dL). Above data clearly indicates that all the above factors contributing to metabolic syndrome were present in significantly higher proportion (p < 0.001) in cases than in controls.

Table 2.

Distribution of subjects in two groups according to presence of different factors contributing to metabolic syndrome.a

| Factors contributing to metabolic syndrome | Controls (n = 100) | Cases (n = 100) | Statistical significance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p value | |||

| Central obesity | 29 | 100 | 110.078 | <0.001 |

| Raised TGL | 2 | 83 | 134.240 | <0.001 |

| Reduced HDL cholesterol | 8 | 76 | 94.910 | <0.001 |

| Raised blood pressure | 32 | 84 | 55.501 | <0.001 |

| Raised fasting plasma glucose | 1 | 47 | 58.004 | <0.001 |

According to gender specific IDF criteria for metabolic syndrome for South Asian population.

Table 3 shows distribution of subjects according to gender in two groups according to presence of different factors contributing to metabolic syndrome: Above data indicates that in controls none of the above factors showed statistically significant difference between males and females. It was found from the present study that all the cases included in the study were centrally obese irrespective of their gender. In cases, reduced HDL cholesterol was found to be in significantly lower proportion of male (58.33%) than female (85.94%) subjects (p = 0.002) and raised blood pressure was found in significantly higher proportion of male (94.44%) than female (78.13%) subjects (p = 0.033). Statistically no significant difference between gender was found in raised TGL (p = 0.947) and raised fasting plasma glucose (p = 0.385).

Table 3.

Distribution of subjects according to gender in two groups according to presence of different factors contributing to metabolic syndrome.

| Controls (n = 100) |

Cases (n = 100) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 64) |

Male (n = 36) |

Female (n = 64) |

Male (n = 36) |

|||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Central obesity | 22 | 34.38 | 7 | 19.44 | 64 | 100 | 36 | 100 |

| χ2 = 2.494; p = 0.114 | χ2 = 0; p = 1 | |||||||

| Raised TGL | 1 | 1.56 | 1 | 2.78 | 53 | 82.81 | 30 | 83.33 |

| χ2 = 0.174; p = 0.677 | χ2 = 0.004; p = 0.947 | |||||||

| Reduced HDL cholesterol | 7 | 10.94 | 1 | 2.78 | 55 | 85.94 | 21 | 58.33 |

| χ2 = 2.084; p = 0.149 | χ2 = 9.625; p = 0.002 | |||||||

| Raised blood pressure | 20 | 31.25 | 12 | 33.33 | 50 | 78.13 | 34 | 94.44 |

| χ2 = 0.046; p = 0.830 | χ2 = 4.566; p = 0.033 | |||||||

| Raised fasting plasma glucose | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.78 | 28 | 43.75 | 19 | 52.78 |

| χ2 = 1.796; p = 0.180 | χ2 = 0.754; p = 0.385 | |||||||

TGL: triglyceride level; HDL: high density lipoprotein.

Table 4 shows comparison of subjects according to lipid parameters: In the present study it was found that serum HDL was significantly lower (p < 0.001) in cases (41.28 ± 8.81) as compared to controls (54.00 ± 6.31). It was also found that serum LDL, VLDL, Triglyceride levels and total cholesterol were found to be significantly higher (p < 0.001) in cases than controls.

Table 4.

Comparison according to lipid parameters.

| Hemodynamic variables | Controls (n = 100) |

Cases (n = 100) |

Statistical significance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ‘t’ value | p value | |

| HDL | 54.00 | 6.31 | 41.28 | 8.81 | 11.748 | <0.001 |

| LDL | 83.66 | 17.08 | 104.92 | 20.16 | −8.043 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides | 134.68 | 18.87 | 189.91 | 63.27 | −8.365 | <0.001 |

| Total Cholesterol | 166.21 | 17.58 | 184.78 | 26.22 | −5.884 | <0.001 |

| VLDL | 26.83 | 3.82 | 36.93 | 11.48 | −8.354 | <0.001 |

HDL: high density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; VLDL: very low-density lipoprotein.

Table 5 shows comparison of subjects according to thyroid profile parameters: Serum T3 levels of cases (2.23 ± 0.46) were found to be higher than that of controls (2.12 ± 0.47) but this difference was statistically non-significant. Serum T4 levels of subjects in control group were found to be significantly higher (p < 0.001) than that of metabolic syndrome cases. In the present study it was found that serum TSH levels of subjects in cases group (3.33 ± 0.78) were significantly higher (p < 0.001) than that of controls (2.30 ± 0.91).

Table 5.

Comparison according to Thyroid profile parameters.

| Thyroid profile | Controls (n = 100) |

Cases (n = 100) |

Statistical significance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ‘t’ value | p value | |

| T3 (1.3–3.1 nmol/l) | 2.12 | 0.47 | 2.23 | 0.46 | −1.624 | 0.106 |

| T4 (66–181 nmol/l) | 134.64 | 22.14 | 117.45 | 25.07 | 5.140 | <0.001 |

| TSH (0.270–4.20 μIU/ml) | 2.30 | 0.91 | 3.33 | 0.78 | −8.660 | <0.001 |

Table 6: It was found that serum T3 correlates positively with waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and fasting sugar level, T4 correlates positively with only systolic blood pressure, while TSH correlates positively only with triglyceride levels.

Table 6.

Distribution of TSH, T3 and T4 with respect to parameters of Metabolic Syndrome (Waist Circumference, SBP, DBP, Triglycerides, Fasting Plasma Glucose, HDL Cholesterol) in patients with metabolic syndrome.

| T3 |

T4 |

TSH |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “r” | “p” | “r” | “p” | “r” | “p” | |

| WC | −0.197 | 0.049 | −0.138 | 0.171 | −0.117 | 0.246 |

| SBP | −0.286 | 0.004 | −0.230 | 0.021 | −0.151 | 0.133 |

| DBP | −0.185 | 0.065 | −0.147 | 0.145 | −0.098 | 0.332 |

| FG | −0.237 | 0.018 | −0.007 | 0.945 | 0.143 | 0.157 |

| TG | −0.008 | 0.938 | 0.018 | 0.859 | 0.265 | 0.008 |

| HDL | 0.055 | 0.585 | −0.027 | 0.790 | −0.065 | 0.521 |

Table 7: It was found that when we compare the distribution of thyroid profile between the male and female, only the TSH was found to be statistical significant.

Table 7.

Distribution of TSH, T3 and T4 with respect to gender.

| Gender | N | Mean | SD | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T3 | M | 36 | 2.23 | 0.46 | t = 0.072; p = 0.942 (NS) |

| F | 64 | 2.23 | 0.47 | ||

| T4 | M | 36 | 115.71 | 23.50 | t = 0.520; p = 0.604 (NS) |

| F | 64 | 118.43 | 26.04 | ||

| TSH | M | 36 | 3.61 | 0.48 | t = 2.688; p = 0.008 (S) |

| F | 64 | 3.18 | 0.87 |

Table 8: It was found that TSH correlates positively throughout between different age group, while T4 correlates positively as the age progress.

Table 8.

Distribution of thyroid profile according to different age groups.

| Age group | Group | N | Mean | SD | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤20 Yrs | T3 | 1 | 2 | 2.73 | 0.05 | t = 19.696; p = 0.003 (S) |

| 2 | 2 | 1.98 | 0.02 | |||

| T4 | 1 | 2 | 138.00 | 23.76 | t = 0.736; p = 0.538 (NS) | |

| 2 | 2 | 151.25 | 9.12 | |||

| TSH | 1 | 2 | 4.09 | 0.08 | t = 21.909; p = 0.002 (S) | |

| 2 | 2 | 2.88 | 0.00 | |||

| 21–40 Yrs | T3 | 1 | 56 | 2.30 | 0.47 | t = 1.333; p = 0.185 (NS) |

| 2 | 56 | 2.18 | 0.49 | |||

| T4 | 1 | 56 | 122.53 | 24.63 | t = 2.852; p = 0.005 (S) | |

| 2 | 56 | 134.74 | 20.45 | |||

| TSH | 1 | 56 | 3.32 | 0.77 | t = 6.452; p < 0.001 (S) | |

| 2 | 56 | 2.24 | 0.98 | |||

| 41–60 Yrs | T3 | 1 | 42 | 2.11 | 0.43 | t = 0.607; p = 0.546 (NS) |

| 2 | 42 | 2.05 | 0.46 | |||

| T4 | 1 | 42 | 109.70 | 23.92 | t = 4.537; p < 0.001 (S) | |

| 2 | 42 | 133.73 | 24.61 | |||

| TSH | 1 | 42 | 3.32 | 0.80 | t = 5.511; p < 0.001 (S) | |

| 2 | 42 | 2.35 | 0.82 |

Group 1: Cases, Group 2: Controls.

Discussion

Asian Indians are a high risk population with respect to diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, and the numbers are consistently on the rise [6]. Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of cardiometabolic risk factors like obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL [7]. Many studies have been carried out abroad as well as in India on metabolic syndrome, however limited data is available on correlation of thyroid profile and serum lipids with metabolic syndrome in Indian population.

The gender differences in prevalence of metabolic syndrome have been found in several studies. It might be due to different cut-off points set as criteria for metabolic syndrome like waist circumference and HDL-Cholesterol [8]. The findings of female gender dominance was seen in our data similar to the Arkhangel study done in Russia, Korea and China [9], [10], while it is comparable to the prevalence data in Frinks cohort study, [11] and the studies conducted in Pakistan [12]. It is worrisome that the increase in prevalence of the metabolic syndrome is higher in women than in men. This is mainly driven by the constant rise in obesity in women, with presently 2 million more women than men being affected in the united states [8] as well as in the under developing countries including south east Asian countries [12].

In our study population, among the cases, central obesity was present in 100% patients of metabolic syndrome. Among other parameters for metabolic syndrome, raised blood pressure was present in 84% of the cases. The third most common parameter was raised triglycerides levels (83%) followed by decreased HDL Cholesterol (76%) and raised fasting plasma glucose (47%). The common components of metabolic syndrome included central obesity and dyslipidemia in our study [Table 2]. This finding is not surprising as it has been seen that central obesity plays a central role in the development of the metabolic syndrome and appears to precede the appearance of the other metabolic syndrome components [8]. The raised blood pressure, raised Triglycerides and decreased HDL cholesterol levels can be attributed to our dietary habits, especially high carbohydrate, high cholesterol and excess salt diet and sedentary life-style.

Different studies have been undertaken to characterize the major components of the metabolic syndrome in women and men in different populations. Investigations performed in the French Monica cohorts to separate the contributions of different factors to the metabolic syndrome showed a significantly elevated body weight, waist girth, and low HDL cholesterol in women than in men [13]. Similar findings were seen in our study i.e. low HDL were present more in women as compared to men while triglycerides levels were same in both the gender but raised blood pressure was found in higher proportion of men than women.

Central fat accumulation and the presence of insulin resistance have both been associated with a cluster of dyslipidemic features, i.e., elevated plasma triglyceride level, an increase in very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), the presence of small dense LDL particles, and a decrease in HDL-cholesterol. These abnormalities of lipoprotein metabolism are more likely to occur together than separately and constitute the key component traits of the metabolic syndrome. In the present study it was found that serum HDL was significantly lower (p < 0.001) in cases (41.28 ± 8.81) as compared to controls (54.00 ± 6.31). It was also found that serum LDL, VLDL, Triglyceride levels and total cholesterol (TC) were found to be significantly higher (p < 0.001) in cases than controls [Table 4]. Dyslipidemia is another well-known risk factor for cardiovascular disease, as well as a component of metabolic syndrome, and the role of HDL, triglycerides (TG) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) are already established as predictors of cardiovascular disease [14]. On the other hand, a characteristic dyslipidemia is also associated with insulin resistance [15]. The LDL cholesterol or total cholesterol level has been widely used to assess lipid atherogenesis, but its utility for Insulin resistance is not well known, in contrast to TG or HDL cholesterol. In the present study, we found a significant higher proportion of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels among cases of metabolic syndrome which is in accordance with the study done by Anthonia O Ogbera [16]. Recent evidence suggests that a fundamental defect is an overproduction of large very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles, which initiates a sequence of lipoprotein changes, resulting in higher levels of remnant particles, smaller LDL, and lower levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol [17].

In the present study it was found that serum TSH levels of subjects in cases group (3.33 ± 0.78) were significantly higher (p < 0.001) than that of controls (2.30 ± 0.91) which is in accordance with the different studies done by Lai et al. and Chugh et al. [18], [19]. Bastemir et al. and Kundsen et al. [2], [20] found in different studies that obesity per se causes increased TSH with no effect on T3 and T4 [3], [20] while studies done by Stichel et al., Reinehr et al. and Kiortsis et al. concluded that obesity causes increase in TSH and T3 with no effect on T4 [23]. In a study done by KVS Hari Kumar et al. [21] T3 showed positive correlation with triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol (LDL), total cholesterol, insulin, HOMA-IR (insulin resistance) and negatively with body fat. TSH correlated positively with BMI, insulin, HOMA-IR, LDL and negatively with HDL-cholesterol (p < 0.05). FT3 correlated positively with waist circumference and T4 did not show correlation with metabolic syndrome parameters [22]. Many different studies shows the positive correlation of thyroid profile with metabolic syndrome [24], similarly in the present study significant association found between the thyroid profile and different component of metabolic syndrome.

In our study, it was found that serum T3 correlates positively with waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and fasting sugar level, T4 correlates positively with only systolic blood pressure, while TSH correlates positively only with triglyceride levels. It may be because of early adjustment and short half life of T3 compare to T4 and TSH in patients with metabolic syndrome.

There was limitation in the present study in determination of exact correlation between thyroid functions and metabolic syndrome as we chose only those subjects in whom thyroid profile was normal and all other subjects with deranged thyroid profile were excluded in order to negate the confounding effect of thyroid function in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome.

From the above study, it is clear those thyroid dysfunctions are independent risk factor for the metabolic syndrome.

Conclusion

Waist circumference, mean systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, fasting blood sugar, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) were significantly higher, and high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were significantly lower in the metabolic syndrome patients compared to the control group concluding that there is significant association between TSH and metabolic syndrome, and it highlights the importance of thyroid function tests in patients with metabolic syndrome. It is still not clear whether alterations in thyroid hormones are a cause or an effect of obesity (metabolic syndrome) suggesting need for further evaluation on a large scale with inclusion of various hormones elaborated by adipose tissue.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Michalaki M.A., Vagenakis A.G., Leonardou A.S., Argentou M.N., Habeos I.G., Makri M.G. Thyroid function in humans with morbid obesity. Thyroid. 2006;16:73–78. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastemir M., Akin F., Alkis E., Kaptanoglu B. Obesity is associated with increased serum TSH level, independent of thyroid function. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:431–434. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stichel H., I'Allemand D., Gruter A. Thyroid function and obesity in children and adolescents. Horm Res. 2000;54:14–19. doi: 10.1159/000063431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhowmick S.K., Dasari G., Levens K.L., Rettig K.R. The prevalence of elevated serum thyroid-stimulating hormone in childhood/adolescent obesity and of autoimmune thyroid diseases in a subgroup. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:773–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The I.D.F. Consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. Int Diabetes Fed IDF. 2006:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misra A., Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008:S9–S30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isomaa B., Almgren P., Tuomi T., Forsén B., Lahti K., Nissén M. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–689. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regitz-Zagrosek V., Lehmkuhl E., Weickert M.O. Review Gender differences in the metabolic syndrome and their role for cardiovascular disease. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006;95:136–147. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-0351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y., Jiang B., Wang J., Feng K., Chang Q., Fan L. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its relation to cardiovascular disease in an elderly Chinese population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1588–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidorenkov O., Nilssen O., Brenn T., Martiushov S., Arkhipovsky V.L., Grjibovski A.M. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its components in Northwest Russia: the Arkhangelsk study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilanne-Parikka P., Eriksson J.G., Lindstrom J., Hämäläinen H., Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S., Laakso M. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its components: findings from a Finnish general population sample and the Diabetes Prevention Study cohort. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2135–2140. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jahan F., Qureshi R., Borhany T., Hamza H.B. Metabolic syndrome: frequency and gender differences at an out – patient clinic. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dallongeville J., Cottel D., Arveiler D., Tauber J.P., Bingham A., Wagner A. The association of metabolic disorders with the metabolic syndrome is different in men and women. Ann Nutr Metab. 2004;48:43–50. doi: 10.1159/000075304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reaven G.M. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogbera A.O. Prevalence and gender distribution of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adiels M., Olofsson S.O., Taskinen M.R., Borén J. Overproduction of very low-density lipoproteins is the hallmark of the dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome. Arter Biol. 2008;28:1225–1236. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Y., Wang J., Jiang F., Wang B., Chen Y., Li M. The relationship between serum thyrotropin and components of metabolic syndrome. Endocr J. 2011;58:23–30. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chugh K., Goyal S., Shankar V., Chugh S.N. Thyroid function tests in metabolic syndrome. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2012;16:958–961. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.102999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kundsen N., Lamberg P., Rasmussen L.B., Bülow I., Perrild H., Ovesen L. Small differences in thyroid function may be important for body mass index and the occurrence of obesity in the population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4019–4024. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar H.K., Yadav R.K., Prajapati J., Reddy C.V.K., Raghunath M., Modi K.D. Association between thyroid hormones, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:908–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinehr T., de Sousa G., Toschke A.M., Andler W. Comparison of metabolic syndrome prevalence using eight different definitions: a critical approach. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:1067–1072. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.104588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiortsis D., Mavridis A., Vasakos S., Nikas S., Drosos A. Effects of infliximab treatment on insulin resistance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:765–766. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.026534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal P., Singh M.M., Gutch M. Thyroid function and metabolic syndrome. Thyroid Res Pract. 2015;12:85–86. [Google Scholar]