Abstract

Objective

Disparity in size between femoral head and acetabulum could promote premature degeneration of the hip joint. The purpose of this study was to report the results of Kawamura's dome osteotomy for acetabular dysplasia due to sequelae of Perthes' disease.

Patients and Methods

Fourteen patients (14 hips) operated between 1999 and 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. There were 9 males and 5 females with a mean age of 29 years (range, 15–54 years). Functional and radiological results were reviewed at mean follow-up of 9 years (range, 4–12 years).

Results

Pain relief was obtained in 13 of 14 (92.8%) patients postoperatively. Good to excellent functional outcome was obtained in 10 of 14 (71.4%) patients. Mean Harris hip score was improved from 63 to 84 (p < 0.05) at the final follow-up. Improvement of limping gait was observed in 10 of 14 (71.4%) patients. Center edge angle improved from mean 24° (11–36°) preoperatively to mean 35° (27–46°) postoperatively (p < 0.05), acetabular angle improved from mean 43° (36–49°) preoperatively to mean 37° (32–44°) postoperatively (p < 0.05), acetabular head index improved from mean 69% (50–83%) preoperatively to mean 85% (73–100%) postoperatively (p < 0.05). Progression of arthrosis stage occurred in 3 of 14 (21%) patients. None of the hip with preoperative Stulberg III, 2 of 9 hips with Stulberg IV and 2 of 2 hips with Stulberg V needed conversion to total hip arthroplasty during the follow-up.

Conclusion

Dome osteotomy of the pelvis combined with trochanteric advancement could give a reasonable treatment outcome for acetabular dysplasia due to Perthes' disease at mid to long-term follow-up. Advanced stage of arthrosis, preoperative Stulberg V and no improvement of limping gait after the surgery possibly associated with poor outcome.

Level of evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study.

Keywords: Dome osteotomy, Trochanteric advancement, Acetabular dysplasia, Perthes' disease, Sequelae

Introduction

One characteristic of the sequelae of Perthes's disease is the presence of disparity in size between femoral head and acetabulum.1 This condition can induce pain and promote early degeneration of the joint.2 Previously, Chiari osteotomy was known as an alternative salvage operation to solve this problem.3 The original Chiari osteotomy was done by making a flat osteotomy at the superior margin of the acetabulum. The femoral head coverage was then increased by making a medial displacement of the pelvis inferior to the osteotomy.4 This procedure could increase hip joint function and its longevity.5

As a modification to the original Chiari osteotomy, Kawamura6 has described a dome osteotomy of the pelvis through lateral approach of the hip by making a standard trochanteric osteotomy. This procedure will result in a dome shape bone shelf to cover the femoral head. By making a dome shape pelvic osteotomy, the resulted acetabular roof will match with the sphericity of the femoral head, thus a higher joint contact area is obtained.7, 8 Simultaneous advancement of the greater trochanter is also possible through this technique. Here we report the treatment outcome of dome osteotomy combined with greater trochanter advancement for sequelae of Perthes' disease.

Patients and methods

All patients who received dome osteotomy of the pelvis as treatment for sequelae of Perthes' disease between January 1999 and December 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. A total of 15 patients received the procedure within the period. However, one patient was lost to follow-up. Therefore, a total of 14 patients (14 hips) were reviewed in this study. Indication for surgery was progressive hip pain not adequately responding to conservative treatment. There were 9 males and 5 females with a mean age of 29.2 years (range, 15–54 years). The mean of follow-up was 9 years (range, 4–12 years). Two patients had history of Salter innominate osteotomy, one patient had history of femoral varus osteotomy while the other patient had adductor tenotomy and iliopsoas release prior to pelvic dome osteotomy. One patient received femoral valgus osteotomy simultaneously with the procedure of pelvic dome osteotomy (Table 1). All patients received greater trochanter advancement during the procedure.

Table 1.

Patient's characteristics and preoperative data.

| No | Age (years) | Sex | Side | BMI (kg/m2) | Previous Surgery | Preoperative |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHS | Limping gait | Arthrosis Stage | Stulberg Classification | ||||||

| 1 | 23 | M | R | 27,1 | Proximal femur varus osteotomy | 47 | Moderate | Early | V |

| 2 | 24 | M | L | 21,6 | – | 73 | Moderate | Pre- | IV |

| 3 | 20 | M | R | 20,1 | – | 76 | Moderate | Early | III |

| 4 | 19 | M | L | 24,2 | – | 71 | Mild | Early | III |

| 5 | 19 | F | L | 19,5 | Salter osteotomy | 48 | Severe | Pre- | IV |

| 6 | 15 | M | R | 23,4 | Adductor tenotomy and psoas release | 73 | Moderate | Advanced | V |

| 7 | 30 | F | L | 27,7 | – | 60 | Mild | Pre- | IV |

| 8 | 40 | F | R | 25,9 | – | 47 | Moderate | Early | IV |

| 9 | 41 | M | L | 24,7 | – | 84 | Mild | Early | IV |

| 10 | 51 | F | R | 20,7 | – | 61 | Mild | Pre- | IV |

| 11a | 54 | M | R | 32,5 | – | 45 | Moderate | Early | IV |

| 12 | 34 | F | R | 22,5 | – | 52 | Severe (crutch) | Advanced | III |

| 13 | 20 | M | L | 22,8 | Salter osteotomy | 81 | Moderate | Advanced | IV |

| 14 | 19 | M | R | 32,2 | – | 68 | Mild | Early | IV |

HHS: Harris hip score; BMI: body mass index; M: male; F: female; R: right; L: left.

Received simultaneous proximal femur valgus osteotomy during dome osteotomy.

Operative technique

All operations were done by the senior author (TRY). Details of the procedure have been reported previously.9 Briefly, patient was placed in lateral position. A longitudinal skin incision was made centered over the greater trochanter. After skin incision, fascia lata was devided. Then a superomedial directed greater trochanter osteotomy was done. The attachment of abductor muscle and vastus lateral muscle to the greater trochanter was retained. Exposure of outer table of ilium was obtained with the limb positioned in abduction while the greater trochanter musculo-osseus sleeve was reflected anteriorly. A stainmann pin with diameter of 3.5 mm was inserted to the pelvis at upper border of the capsule in superomedial direction with an angle approximately 15° to horizontal line. The position of the Steinmann pin was confirmed with fluoroscopy. A dome osteotomy was done with the guidance of the Steinmann pin position using an oscillating saw. After osteotomy was completed, distal pelvic fragment was displaced medially. The resulted femoral head coverage was confirmed with fluoroscopy. Internal fixation of the pelvis osteotomy was achieved using a Steinmann pin with diameter of 2.4 mm. Then the greater trochanter was reattached using two cancellous screws or stainless steel wire at a distally advanced position. One patient received closed wedge femoral valgus osteotomy simultaneously.

An abduction brace was used postoperatively. Non-weight bearing crutch walking was allowed within one week and continued until approximately three months upon evaluation for radiological bone union. The Steinmann pin was removed at 6–12 weeks. Patients were followed at one month, three months, six months, one year, and every year thereafter postoperatively. Evaluation for improvement of the pain, gait pattern, joint range of movement (ROM), and functional assessment with Harris hip score (HHS)10 was carried out at each follow-up.

Standard anteroposterior radiographs of the pelvis were taken preoperatively, immediate postoperatively, and at each follow-up. Center edge angle of Wiberg11, acetabular angle of Sharp12, and acetabular head index13 were measured for all radiographs. Joint space at the weight bearing area and the narrowest point were also measured. The angle of pelvic osteotomy, distance and percentage of displacement at the pelvic osteotomy, and distance of greater trochanter advancement were measured for immediate postoperative radiographs (Fig. 1). All radiographic measurement was performed digitaly using Marosis PACS software (Marotech Inc., Seoul, South Korea). With this software, measurement of angles and distances resulted in two decimal points after compensation of magnification. It was then rounded off. Based on modified classification of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association14, all hips were classified into the following four stages of arthrosis based on anteroposterior pelvic radiographs: prearthrosis (dysplasia only), early arthrosis (slight joint space narrowing and subchondral sclerosis), advanced arthrosis (marked joint space narrowing with or without cyst or sclerosis), and terminal arthrosis (obliteration of joint space). Preoperative radiographic of the hip was also classified based on Stulberg classification.15

Fig. 1.

Important points on radiographic measurement. b–c: Distance of acetabular displacement; b-c/a-c x 100%: Percent of acetabular displacement; d–e: Distance of trochanteric advancement.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Paired student's t-test was used to evaluate the significance of data. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Mean HHS was significantly (p < 0.05) improved from 63 (range, 45 to 84) preoperatively to 84 (range, 58 to 100) at the last follow-up. Functional outcomes were excellent in 6, good in 4, fair in 2, and poor in 2 patients. Pain relief was obtained in all patients except one who experienced persistent pain postoperatively. Preoperatively, four patients had severe pain, 9 patients had moderate pain, and 1 patient had mild pain. At the last follow-up, 6 patients had no pain, 4 had mild pain, and 4 had moderate pain. Postoperative joint ROM was not significantly different from preoperative joint ROM.

The effect of this procedure on gait pattern was also evaluated. Limping gait (part of HHS) was improved in ten patients. Four patients reported no difference on gait between preoperative and postoperative. Preoperatively, two patients had severe limping, seven patients had moderate limping, and five patients had mild limping. One patient who had severe limping preoperatively need one crutch aid during walk. Postoperatively, no limping gait was observed in 5 patients and mild limping was observed in 7 patients. The other two patients had moderate limping gait (Table 2). None of these patient required walking aid during ambulation at the last follow-up. One patient experienced inferior gluteal nerve injury and buttock muscle atrophy during follow-up. However, gait pattern in this patient was still improved (moderate to mild limping) postoperatively. No other complications related to dome and greater trochanter osteotomies occurred during the follow-up. Four cases finally converted to total hip arthroplasty (THA) during the follow-up. Of the four cases, THA was needed for three due to pain. The other THA was needed due to unsatisfactory ROM.

Table 2.

Final follow-up data.

| Patient No | Followup Duration (months) | HHS | Limping Gait | Arthrosis stage | Progression of arthrosis | Conversion to THA | Reason of THA | Duration (months) | Functional After THA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 145 | 78 | Mild | Advanced | + | + | Pain | 132 | Excellent |

| 2 | 78 | 86 | Mild | Pre- | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 | 122 | 89 | Mild | Early | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 | 66 | 100 | No | Early | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5 | 123 | 90 | Mild | Advanced | + | – | – | – | – |

| 6 | 82 | 60 | Moderate | Advanced | – | + | Pain | 48 | Excellent |

| 7 | 151 | 100 | No | Pre- | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8 | 155 | 84 | No | Early | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9 | 143 | 94 | Mild | Early | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 62 | 92 | No | Pre- | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11 | 132 | 92 | No | Advanced | + | – | – | – | – |

| 12 | 52 | 85 | Mild | Advanced | – | – | – | – | – |

| 13 | 86 | 76 | Moderate | Advanced | – | + | ROM | 6 | Excellent |

| 14 | 120 | 58 | Mild | Early | – | + | Pain | 8 | Excellent |

HHS: Harris hip score; THA: total hip arthroplasty; ROM: range of movement.

Based on Stulberg classification, preoperative radiograph was classified into type III in 3 patients, type IV in 9 patients, and type V in 2 patients. Preoperatively, 3 patients were in advanced arthrosis, 7 were in early arthrosis, and 4 were in prearthrosis stage. Progression of arthrosis was observed in three patients at the last radiograph follow-up.

Mean center edge angle of Wiberg, mean acetabular angle of Sharp, mean acetabular head index, and mean weight bearing joint space were improved significantly after the surgery (Fig. 2). No significant difference in minimum joint space at the final follow-up was found. Mean pelvic osteotomy angle was 19° (range, 15° to 28°). Mean distance of acetabular displacement was 15 mm (range, 10–21 mm). Mean acetabular displacement percentage was 27% (range, 15%–36%) (Table 3). There was no penetration of osteotomy into the joint. Mean greater trochanter advancement was 17 mm (range, 10–23 mm). No sign of infection, pelvic or greater trochanter nonunion, femoral head avascular necrosis, or heterotopic ossification was observed in our series.

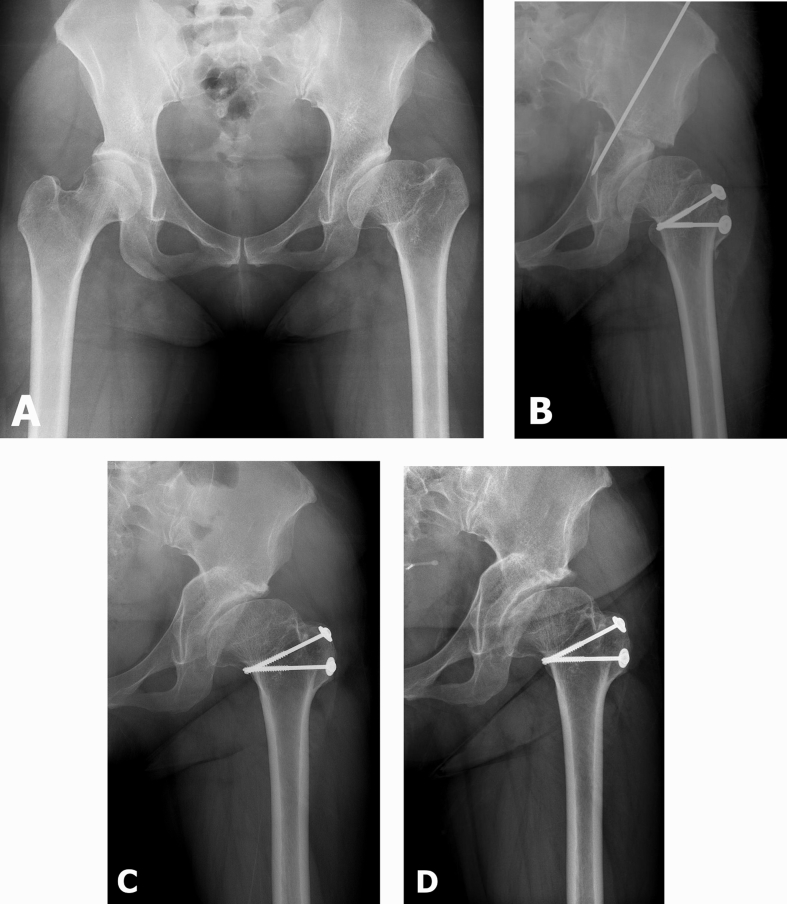

Fig. 2.

(A) Preoperative radiograph of a 30-year-old female with left hip sequelae of Perthes' disease (Stulberg IV); (B) Immediate postoperative radiograph; (C) Radiograph at 6-year follow-up; (D) Joint space was maintained at 12-year follow-up. At this time, the patient was asymptomatic.

Table 3.

Mean and range of radiographic parameters at preoperative, immediate postoperative, and final follow-up.

| Radiographic parameters | Preoperative | Immediate postoperative | Final F/U |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preop-postop | Preop-final F/U | ||||

| Center edge angle of Wiberg | 24° (11-36°) | 35° (27-46°) | 37° (29-48°) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Acetabular angle of Sharp | 43° (36-49°) | 37° (32-44°) | 37° (33-42°) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Acetabular head index | 69% (50–83%) | 85% (73–100%) | 85% (57–100%) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Weight bearing joint space | 5 mm (3–6 mm) | 8 mm (5–12 mm) | 6 mm (4–9 mm) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Minimum joint space | 3 mm (1–4 mm) | 4 mm (2–7 mm) | 3 mm (2–5 mm) | 0.040 | 0.547 |

| Pelvic osteotomy angle | – | 19° (15o–28°) | – | – | – |

| Acetabular displacement | – | 15 mm (10–21 mm) | – | – | – |

| Acetabular displacement (%) | – | 27% (15–36%) | – | – | – |

| Trochanteric advancement | – | 17 mm (10–23 mm) | – | – | – |

F/U: follow-up; Preop: preoperative; Postop: postoperative.

Discussion

Acetabular dysplasia could be caused secondary to developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), neuromuscular disorders, Perthes' disease, or trauma.16 Migaud et al17 have reported the outcome of original Chiari osteotomy for treatment of acetabular dysplasia in 90 hips due to various etiology at mean follow-up of six years. At the final follow-up, they found that 73 patients had slight or no pain while the rest of them had moderate to severe pain. Worsening of the joint arthrosis was found in 16 (17.7%) patients at the final follow-up. Anwar et al7 have reported a relatively better outcome on the use of pelvic dome osteotomy combined with trochanteric advancement for treating acetabular dysplasia due to various etiologies. They reported excellent or good clinical result for 93 (92%) of 101 hips at a mean follow-up of 8.3 years. Progression of joint arthrosis was found in 10 cases at final follow-up. Factors significantly associated with poor outcome included advanced stage of arthrosis, valgus deformity of proximal femur, older age at time of operation, and postoperative persistence of abductor insufficiency.7

Different from the previous study, our series involved more adult population of acetabular dysplasia due to sequelae of Perthes' disease. Only a few studies have reported treatment outcome of dome osteotomy in this specific population. Koyama et al18 have reported the outcome of dome osteotomy combined with trochanteric advancement for coxarthrosis after Perthes' disease. Similar to our series, they found that center edge angle of Wiberg, acetabular angle of Sharp, and acetabular head index were significantly improved on postoperative radiograph evaluation. They also found that pain was improved in 11 of a total of 14 hips (79%) at a median follow-up of 6 years. Median hip score was increased from 76 preoperatively to 91 postoperatively. However, they found that the overall activity of daily life was not improved.18

In our series, three patients experienced radiographic progression of arthrosis at the final follow-up. However, only one of them needed conversion to THA at the final follow-up. This patient received THA at 11 years after dome osteotomy (Fig. 3). Despite of good radiological result and pain relief, one of our patients requested THA because he was unsatisfied with the ROM of the joint. Similar to results of Koyama et al18, significant improvement of joint ROM was not found at the final follow-up in this study. For comparison, Sakai et al8 have reported a long term follow-up of dome osteotomy for acetabular dysplasia due to DDH. With a minimum follow-up of 25 years, 21 of 59 (36%) hips converted to THA at a mean of 18 years (range, 2.5–25 years). They found that older age, presence of preoperative Trendelenberg sign, higher arthrosis grade, and smaller postoperative acetabular head index predicted conversion to THA.8

Fig. 3.

(A) Preoperative radiograph of a 23-year-old male with right hip sequelae of Perthes' disease (Stulberg V); (B) Immediate postoperative radiograph; (C) Radiograph at postoperative11 years. At this time, the patient requested THA; (D) Radiograph at 4 months after THA.

In our series, 3 of 4 patients who had no improvement in limping gait needed THA conversion during the follow-up. We also paid attention to the role of Stulberg classification of preoperative radiograph on the prediction of THA conversion. We found that 2 of 9 (22%) patients who had Stulberg IV and all (two) patients who had Stulberg V needed conversion to THA during the follow-up period. However, no patients who had Stulberg III needed THA conversion at the final follow-up.

This study has several limitations. It was a retrospective study with a small group of patients. Such small number of patients was included because most patients with sequelae of Perthes' disease who came to our hospital were at terminal stage of arthrosis which contraindicated joint preservation surgery. A longer follow-up is needed to determine the long-term outcome of this procedure. In addition, there was no control group in this study.

In summary, our study demonstrated that dome osteotomy of the pelvis combined with trochanteric advancement could give a reasonable treatment outcome for acetabular dysplasia due to Perthes' disease at mid to long-term follow-up. Advanced stage of arthrosis, preoperative Stulberg V and no improvement of limping gait after the surgery possibly associated with poor outcome.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant (CRI18092-1) of Chonnam National University Hospital Biomedical Research Institute.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Turkish Association of Orthopaedics and Traumatology.

Contributor Information

Asep Santoso, Email: asepsantoso@gmail.com.

Pramod Shaligram Ingale, Email: pramodingale2010@gmail.com.

Ik-Sun Choi, Email: iksunchoios@gmail.com.

Young-Rok Shin, Email: x-file0826@hanmail.net.

Kyung-Soon Park, Email: chiasma@hanmail.net.

Taek-Rim Yoon, Email: tryoon@jnu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Bennett J.T., Mazurek R.T., Cash J.D. Chiari's osteotomy in the treatment of Perthes' disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:225–228. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynolds D.A. Chiari innominate osteotomy in adults. Technique, indications and contra indications. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:45–54. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B1.3941141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karami M., Fitoussi F., Ilharreborde B., Penneçot G.F., Mazda K., Bensahel H. The results of Chiari pelvic osteotomy in adolescents with a brief literature review. J Child Orthop. 2008;2:63–68. doi: 10.1007/s11832-007-0071-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiari K. Medial displacement osteotomy of the pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;98:55–71. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy R.R., Morin C. Chiari osteotomy in Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:1–9. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawamura B. The transverse pelvic osteotomy. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 1959;32:1181–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anwar M.M., Sugano N., Matsui M., Takaoka K., Ono K. Dome osteotomy of the pelvis for osteoarthritis secondary to hip dysplasia. An over five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:222–227. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B2.8444941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakai T., Nishii T., Takao M., Ohzono K., Sugano N. High survival of dome pelvic osteotomy in patients with early osteoarthritis from hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2573–2582. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2282-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu Q.S., Ul-Haq R., Park K.S., Yoon T.R., Lee K.B. Dome osteotomy of the pelvis using a modified trochanteric osteotomy for acetabular dysplasia. Int Orthop. 2012;36:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris W.H. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint: with special reference to the complication of osteoarthrosis. Acta Chir Scand. 1939;83:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp I.K. Acetabular dysplasia: the acetabular angle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:268–272. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyman C.H., Herndon C.H. Legg-Perthes disease; a method for the measurement of the roentgenographic result. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32A:767–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higuchi F., Inoue A. Chiari pelvic osteotomy using lateral approach. Orthop Surg Trauma. 1995;38:331–337. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stulberg S.D., Cooperman D.R., Wallensten R. The natural history of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:1095–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osebold W.R., Lester E.L., Watson P. Dynamics of hip joint remodeling after Chiari osteotomy. 10 patients with neuromuscular disease followed for 8 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:128–132. doi: 10.3109/17453679709003994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migaud H., Duquennoy A., Gougeon F., Fontaine C., Pasquier G. Outcome of Chiari pelvic osteotomy in adults. 90 hips with 2-15 years' follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66:127–131. doi: 10.3109/17453679508995505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koyama K., Higuchi F., Inoue A. Modified Chiari osteotomy for arthrosis after Perthes' disease. 14 hips followed for 2-12 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:129–132. doi: 10.3109/17453679809117612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]