Abstract

WRKY transcription factors (TFs) are responsible for the regulation of genes responsive to many plant growth and developmental cues, as well as to biotic and abiotic stresses. The modulation of gene expression by WRKY proteins primarily occurs by DNA binding at specific cis-regulatory elements, the W-box elements, which are short sequences located in the promoter region of certain genes. In addition, their action can occur through interaction with other TFs and the cellular transcription machinery. The current genome sequences available reveal a relatively large number of WRKY genes, reaching hundreds of copies. Recently, functional genomics studies in model plants have enabled the identification of function and mechanism of action of several WRKY TFs in plants. This review addresses the more recent studies in plants regarding the function of WRKY TFs in both model and crop plants for coping with environmental challenges, including a wide variety of abiotic and biotic stresses.

Keywords: Transcriptional regulation, signaling, abscisic acid, kinases, stresses

Introduction

Plants are continuously exposed to environmental stresses, such as variations in temperature, nutrient content and availability in the soil, rain availability, and pest/pathogen attacks. Their exposure to this range of stresses unleashes responses at various levels. At the molecular level it activates signaling cascades responsible for inducing or repressing target gene expression. Transcription factors (TFs) are proteins that regulate gene transcription, and any change in their activity dynamically alters the transcriptome, causing metabolic and phenotypic changes in response to a given environmental stimulus (Mitsuda and Ohme-Takagi, 2009).

In eukaryotes, the transcriptional regulation is mediated by recruitment of TFs that recognize and bind to cis-regulatory elements (CREs), which are short sequences present in the promoter regions of genes. TFs interact with CREs, other TFs, and with the basal transcription machinery in order to regulate the expression of target genes (Priest et al., 2009).

Stimuli caused by environmental changes are primarily perceived by a receptor and later transmitted to the nucleus by a complex network of protein interactions. The signals can be transmitted to the nucleus by several systems, including GTP-binding (G proteins that alter their activity by binding to GTP), protein kinase cascades that are phosphorylated in sequence and activate a series of proteins, and ion channels that change ionic features of cells (Mulligan et al., 1997). As observed in the majority of adaptive responses, gene expression is strictly controlled and presents a fast and reversible kinetic response, allowing a cell to change its transcriptional status within minutes in the presence of the stressor, and to return to its basal state when that is no longer present (de Nadal et al., 2011).

Eukaryotic cells have developed sophisticated mechanisms of sensitivity and signal transduction systems that can produce precise results and dynamic responses. Receptor molecules are stimulated by external stimuli and initiate a cascade of downstream signaling network that, through a cross-talk with molecular cell process, respond to the various environmental and developmental stimuli (Osakabe et al., 2013). Changes in gene expression are an important component of stress responses, together with metabolic changes, cell cycle progression, cytoskeleton protein homeostasis, vesicle protein trafficking, enzymatic activity (de Nadal et al., 2011), production of reactive oxygen species (Baxter et al., 2014), and protein phosphorylation (Shiloh and Ziv, 2013).

WRKY factors play an essential role in the regulation of many stress responses of plants, and many studies related to this class of TFs have described activity in response to biotic stresses. However, some recent reports have shown their link also to abiotic stresses. Many WRKY genes have roles in multiple pathways induced by stresses, suggesting nowadays that the signal network involving WRKY includes biotic and abiotic stresses (Eulgem, 2006). However, little is known about the signaling pathways mediated by WRKY TFs induced by abiotic stresses (Rushton et al., 2010).

Most WRKY proteins are involved in responses to bacterial and fungal pathogens, hormones related to pathogens, and salicylic acid (Rushton et al., 1996; Eulgem et al., 1999). They usually mediate signaling by the elicitor molecule encoded by the pathogen and quickly induce apoptosis of cells so as to avoid posterior invasion (Yamasaki et al., 2005).

An increasing number of recent studies have indicated that WRKY proteins are also involved in a variety of other plant specific reactions such as senescence (Miao et al., 2008), mechanical damage (Hara et al., 2000), drought (Zhang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011), heat shock (Li S et al., 2010) high salinity (Wang F et al., 2012; Niu et al., 2012), UV radiation (Izaguirre et al., 2003), sugar signaling (Sun et al., 2003), gibberellins (Zhang et al., 2004), abscisic acid (ABA) (Xie et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2010), and many other processes (reviewed by Agarwal et al., 2011; Phukan et al., 2016). Several studies concerning genetic transformation, including generation of transgenic lines, aiming to identify WRKY TFs functions in response to various biotic and abiotic stresses are shown on supplementary material (Tables S1 (133.8KB, pdf) , S2 (123KB, pdf) , S3 (97.1KB, pdf) and S4 (175.9KB, pdf) ).

Given the importance of this transcription factor family and its relation to biotic and abiotic stresses, the objective of this review was to survey the current knowledge on the regulation, activity, and targets of WRKY family TFs, as well as to give an overview of the main studies about losses and gains of function of WRKY genes in different plant species.

The structure of WRKY transcription factors

WRKY proteins share a DNA binding domain of about 60 amino acids that contains an invariable sequence WRKYGQK (from which the domain was named - WRKY) and a zinc-finger domain-like (CX4–5CX22–23HXH or CX7CX23HXC) (Rushton et al., 1996). Many WRKY proteins have two WRKY domains, which are classified in Group I. Those that have a single WRKY domain and containing the zinc-finger motif Cys2-His2 are classified in Group II, which is divided into five subgroups (IIa-e) based on additional structural motifs conserved outside the WRKY domain. The proteins from Group III show a WRKY domain containing different zinc-finger motifs Cys2-His/Cys Cys2-His2 (Eulgem et al., 2000).

A new WRKY structure has recently been reported, and different novel substitutes of WRKY domains in N- and C-terminal region of WRKY TFs were found (Mohanta et al., 2016). The conserved WRKY amino acids were replaced by different types of amino acids in many different plant species compared to Arabidopsis e.g. W-K-K-Y in Brassica rapa, Citrus clementine, Citrus sinensis, Eucalyptus grandis, Linum usitatissimum, Phaseolus vulgaris, Physcomitrella patens, Picea abies, Populus trichocarpa, Prunus persica and Sorghum bicolor; and W-R-I-Y in Arabidopsis lyrata, W-H-Q-Y in Glycine max, A-R-K-M, W-W-K-N and W-R-M-Y in Phaseolus vulgaris, W-R-K-R, W-I-K-Y, W-S-K-Y and W-Q-K-Y in Solanum lycopersicum, W-H-K-C and W-R-K-C in Solanum tuberosum, F-R-K-Y in Populus trichocarpa (Mohanta et al., 2016).

Subsequently, based on phylogenetic analyses, WRKY TFs were divided into I, IIa + IIb, IIc, IId + IIe, and III. Group II was found to be monophyletic (Zhang and Wang, 2005). Besides the two highly conserved domains, WRKY and zinc-finger, Cys2-His2 or Cys2-His/Cys WRKY proteins also contain the following structures: basic signals of putative nuclear localization, leucine zipper, and TIR-NBS-LRR kinase domains that are serine-threonine, glutamine or proline abundant regions. These domain variations in their structure make WRKY proteins play their appropriate roles in the regulation of gene expression (Chen et al., 2012). WRKY proteins are known to mediate signaling by binding to the target gene promoter regions that contain W-box (T) TTGACY sequences, where the letter Y can mean C or T (Pater et al., 1996; Rushton et al., 1996; Eulgem et al., 1999). Genes containing the ERAC W-box in their promoter regions are targets of WRKY including the genes from WRKY family (Eulgem et al., 1999).

WRKY TFs were originally considered exclusive to plants. However, recent reports have detected their presence also in protists (Giardia lamblia) and in Metazoa (Dictyostelium discoideum), suggesting an origin of WRKYs predating the origin of plants (Ulker and Somssich, 2004).

A survey of sequenced plant genomes has revealed that the WRKY TF family is composed by a large number of genes, i.e., 74 genes in Arabidopsis thaliana, 81 genes in Brachypodium distachyon, 51 in Citrus sinensis, 48 in Citrus clementina, 38 genes in Daucus carota, 179 genes in Glycine max, 58 genes in Jatropha curcas,117 genes in Manihot esculenta, 123 genes in Malus domestica, 54 in Morus notabilis, 116 genes in Oryza sativa ssp. Indica, 137 genes in Oryza sativa ssp. japonica, 88 genes in Phaseolus vulgaris, 119 genes in Populus trichocarpa, 79 genes in Solanum lycopersicum, 82 genes in Solanum tuberosum, 98 genes in Vitis vinifera, and 180 genes in Zea mays, (Zhang et al., 2010; Xiong et al., 2013; Ayadi et al., 2016; Baranwal et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Mohanta et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017).

WRKY TF and kinase interaction

Mitogen activated proteins kinases (MAPKs) modulate many plant signaling responses, including response to stresses, making a connection between stimuli perception and molecular cell responses (de Zelicourt et al., 2016). Also, pathway signaling activation mediated by MAPKs is a vital process for plant responses (Sheikh et al., 2016).

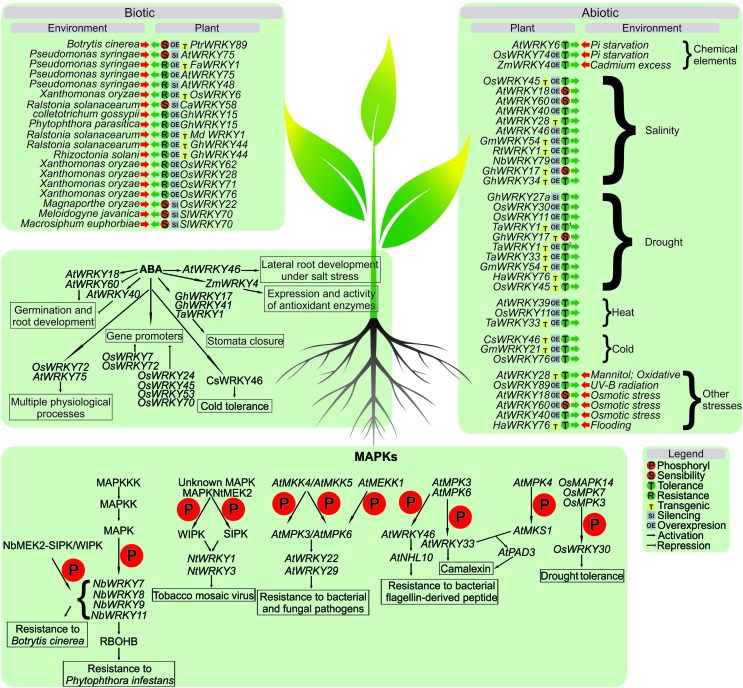

Several studies have suggested that certain WRKY proteins can be targeted by MAPKs, which alter their activity (Figure 1). For example, WIPK (wound-inducible protein kinase) and SIPK (salicylic acid-inducible protein kinase) are two widely studied kinases concerning stress response. They are phosphorylated by MAPKNtMEK2 (in tobacco) in response to infection by a pathogen and by an unknown MAPK upstream. Both WIPK and SIPK seem to be upstream of NtWRKY1 and NtWRKY3 in the signaling cascade of Nicotiana’s defense response (Kim and Zhang, 2004). AtWRKY22 and AtWRKY29 were also identified as located downstream in the MAPK signaling cascade (Asai et al., 2002).

Figure 1. Overview of the most recent reports concerning WRKY roles in plant defense, including the relationships with MAPKs, ABA signaling, and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses.

The mitogen activated protein kinase genes MPK3 and MPK6 are responsive to pathogens and play an essential role in inducing camalexin, the main phytoalexin in Arabidopsis thaliana (Han et al., 2010). Arabidopsis mutants in the wrky33 gene with gain of MPK3 and MPK6 function showed impairment in the production of camalexin induced by pathogens. AtWRKY33 is a transcription factor induced by pathogens whose expression is regulated by the MPK3/MPK6 cascade. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation experiments showed that AtWRKY33 binds to its own promoter in vivo, suggesting a possible regulation by means of a feedback loop (Mao et al., 2011). The AtWRKY33 protein is the substrate of MPK3/MPK6, and mutations in phosphorylation sites of MPK3/MPK6 in AtWRKY33 compromise their ability to complement the induction of camalexin in Atwrky33 mutants. Additionally, in assays of phosphoprotein mobility, it was observed that AtWRKY33 is phosphorylated in vivo by MPK3/MPK6 in response to infection by Botrytis cinerea. AtWRKY33 acts downstream of MPK3/MPK6 in reprogramming camalexin biosynthesis genes, boosting metabolic flow towards the production of Arabidopsis camalexin in response to pathogens (Mao et al., 2011). Likewise, another report demonstrates a relationship of AtWRKY33 with a MAPK (Qiu et al., 2008). In the Atwrky33 mutant, a reduction of PAD3 (Phytoalexin deficient3) mRNA was detected, which was also observed in a mpk4-wrky33 double mutant. This suggested that AtWRKY33 acts with MPK4 in nuclear complexes that depend on MKS1, an MPK4 substrate. When infected with Pseudomonas syringae, MPK4 is activated and phosphorylates MKS1, which binds to AtWRKY33. That complex binds to a PAD3 promoter, which itself encodes an enzyme for camalexin synthesis (Qiu et al., 2008).

A recent report demonstrates the relationship of MPK3 and MPK6 in targeting WRKY phosphorylation in 48 Arabidopsis WRKYs in vitro. Most of the analyzed WRKYs were targets of both MPKs. A phosphorylation of AtWRKY46 was analyzed in vivo, and elicitation with bacterial flagellin-derived flg22 peptide (a pathogen associated molecular pattern - PAMP) led to in vivo AtWRKY46 responses. When overexpressed, it raised basal plant defense, as reflected by the increase in promoter activity of NHL10 (a PAMP-responsive gene), in a MAPK-dependent pathway. A mechanism of plant defense controlled by AtWRKY46 in a MAPK-mediated pathway was suggested (Sheikh et al., 2016).

In rice it was demonstrated that overexpression of OsWRKY30 transgenic lines improved drought tolerance. OsWRKY30 could interact with and is phosphorylated by OsMPK3, as well as by many other OsMAPKs. Moreover, phosphorylation of OsWRKY30 by MAPKs is crucial for its biological function (Shen et al., 2012). OsWRKY30, in addition to the two WRKY domains in the N-terminus, presents multiple serine-proline (SP) sites that can be putatively phosphorylated by MAP kinases (Cohen, 1997). OsWRKY30 was found phosphorylated in vitro by OsMPK3, OsMPK7, and OsMPK14, suggesting that OsWRKY30 is a potential substrate of OsMPKs, which are proline-directed kinases (Shen et al., 2012).

Studies in Nicotiana benthamiana indicated that phospho-mimicking mutations of WRKYs result in strong induction of cell death, revelaed by examination of WRKY 7-15 made by agroinfiltration in leaves. Four days after the infiltration, trypan blue staining showed that WRKY 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, and 14 were expressed in leaves developing cell death, suggesting that these WRKYs are involved in inducing cell death as MAPK substrate (Adachi et al., 2015). In addition, VIGS-silencing construction with WRKY7, 8, 9, and 11 in leaves delayed cell death in VIGS of SIPK, and WIPK; a suppression of MEK2DD was detected. Difference between TRV-control and WRKY7, 8, 9, and 11-silenced leaves was found through an index of cell death suggesting that this WRKYs participates in HD-like cell death downstream of a MEK2-SIPK/WIPK cascade (Adachi et al., 2016).

WRKY and abscisic acid signaling

Abscisic acid (ABA) plays a variety of roles in plant development, bud and seed dormancy, germination, cell division and movement, leaf senescence and abscission, and cellular response to environmental signals (Rohde et al., 2000; Leung and Giraudat, 1998; Zhu, 2002; Xie et al., 2005). Many reports have shown the involvement of WRKYs and ABA (Figure 1). During drought stress, the accumulation of ABA leads to stomata closure, which helps to maintain the cell water status under water deficit conditions by reducing water loss as a result of transpiration (Schroeder et al., 2001). The possibility that WRKY TFs are involved in stomata closing as a response to both biotic and abiotic stress is an area that requires more research, although evidence is slowly appearing (Rushton et al., 2012).

In Arabidopsis, WRKY proteins act as transcription activators or repressors. Through single, double, and triple mutants, as well as lines overexpressing WRKY genes analyses, it was shown that AtWRKY18 and AtWRKY60 have positive effects on the ABA sensitivity of plants regarding inhibition of seed germination and root growth and increase in the sensitivity to salt and osmotic stress. AtWRKY40 antagonizes with AtWRKY18 and AtWRKY60 concerning the effect caused on the sensitivity of plants to ABA and abiotic stresses, and both genes are rapidly induced by ABA, while induction of AtWRKY60 is delayed by ABA (Chen et al., 2010). ABA-regulated genes such REGULATORY COMPONENT OF ABA RECEPTOR (RCAR), ABA INSENSITIVE 1 (ABI1) and ABI2, together with ABSCISIC ACID RESPONSIVE ELEMENTS-BINDING FACTOR (ABF) were found differentially expressed in the Atwrky40 mutant indicating that they are directly regulated by AtWRKY40 (Shang et al., 2010). On the other hand, AtWRKY18, AtWRKY60 and AtWRKY40 were reported as negative regulators of ABI4 and ABI5 genes by binding to W-box sequences in their promoters suggesting a negative role in ABA signaling (Liu et al., 2012).

In addition, expression of AtWRKY60 induced by ABA is practically null in the mutants Atwrky18 and Atwrky40, indicating that AtWRKY18 and AtWRKY40 recognize a group of W-box sequences in the promoter of AtWRKY60 and activate the expression of AtWRKY60 in protoplasts. Thus, AtWRKY60 could be a direct target of AtWRKY18 and AtWRKY40 in ABA signaling (Chen et al., 2010).

Stomata closure was also tested in tobacco by overexpressing lines, showing that ABA participates in GhWRKY41-induced stomata closure. Stomata movement was analyzed with or without ABA treatment, and the authors found that ABA treatment reduced stomata apertures in the wild type and overexpression lines (Chu et al., 2015).

In rice aleurone cells, the genes OsWRKY24 and OsWRKY45 acted as repressors of a gene promoter induced by ABA, while OsWRKY72 and OsWRKY7 activated the same gene promoters (Xie et al., 2005). Reports on OsWRKY53 and OsWRKY70, paralogs of OsWRKY24, showed the same effect, acting as repressors of a gene promoter induced by ABA (Zang et al., 2015). In Arabidopsis, OsWRKY72 interfered in the abscisic acid signal and auxin transport pathway, so that Arabidopsis lines overexpressing OsWRKY72 showed retarded seed germination under normal conditions and higher sensitivity to mannitol, NaCl, ABA stresses, and sugar starvation when compared to vector plants (Yu et al., 2010).

WRKY and response to abiotic stresses

The relationship between WRKYs in response to abiotic stress has been investigated and is shown in Figure 1 and Table S1 (133.8KB, pdf) . Most reports describe the overexpression of different WRKY genes that resulted in abiotic stress-tolerant phenotypes in different plant species. The majority of stresses studied were salt excess, heat, and drought.

Chemical elements

In Arabidopsis, the regulation of the PHOSPHATE1 (PHO1) gene, which encodes for a phosphate carrier protein from root to shoot (Hamburger et al., 2002), is also important for the adaptation of plants to low phosphate environments (Chen et al., 2009). Under normal conditions, AtWRKY6 suppresses the expression of AtPHO1 to maintain homeostasis of phosphate in the plant through binding to two W-box CREs located in the AtPHO1 gene promoter region (Chen et al., 2009). Regarding phosphate starvation in rice, OsWRKY74 was reported to be involved in tolerance mechanisms. When overexpressed, root and shoot biomass and phosphorus concentration were higher compared to wild type, in an opposite way from what was found in OsWRKY74 loss of function (Dai et al., 2016).

Cadmium stress studies in maize revealed the involvement of ZmWRKY4 in response to stress. ZmWRKY4-silencing by RNAi in mesophyll protoplasts reveal its involvement as a requirement in ABA-induced genes expression and in antioxidative enzyme activity. In overexpression lines, ABA-induced genes were up-regulated and antioxidative enzyme activity was promoted (Hong et al., 2017).

Transcriptomic analyses have also revealed the involvement of WRKYs in nutrient stresses. In rice leaves under manganese stress, six up-regulated WRKYs were identified suggesting their involvement in the stress (Li et al., 2017). Involvement of WRKYs was also detected through microarray analysis in rice leaves under iron stress (Finatto et al., 2015).

Salinity

To study the response to salinity, desiccation, and oxidative stress, Arabidopsis transgenic lines expressing a multigene cassette with GUS, AtWRKY28, and AtBHLH17 (AtAIB) were developed. AtbHLH17 (AtAIB) and AtWRKY28 are TFs known to be up-regulated under drought and oxidative stress, respectively. The transgenic lines exhibited enhanced tolerance to NaCl, mannitol, and oxidative stress. Under mannitol stress condition, significantly higher root growth was observed in transgenic plants. Growth under stress and recovery growth was substantially higher in transgenic plants exposed to gradual longer desiccation stress conditions. The TFs AtNAC102 and AtICE1, which contain either bHLH or WRKY binding cis-elements, showed enhanced expression in transgenic plants under stress. However, genes lacking either one of the two motifs did not differ in their expression levels in stress conditions when compared to wild type plants (Babitha et al., 2012). Moreover, in Arabidopsis, overexpression of AtWRKY46 enhanced lateral root development in salt stress via regulation of ABA signaling. In ABA-related mutants, AtWRKY46 expression was down-regulated but up-regulated by an ABA-independent signal induction under salt stress (Ding et al., 2015).

Another report regarding salinity showed that transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GhWRKY34 (Gossypium hirsutum) enhanced the tolerance to salt stress by improving the plants’ ability to selectively uptake Na+ and K+ and maintain low Na+/K+ in leaves and roots of transgenic plants (Zhou et al., 2015). Transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GmWRKY54, a soybean WRKY, also displayed salt tolerance (Zhou et al., 2008). Overexpressing lines had 70% of survival under 180 mM NaCl treatment while wild type plants showed a survival of 25%.

Furthermore, transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing RtWRKY1 (Rt: Reaumuria trigyna) also demonstrated salinity tolerance. Transgenic lines were able to develop roots, increase fresh weigh under salt stress, as well as showing an increase in antioxidative enzymes activity, and lower Na+ content and Na+/K+ ratio compared to wild type plants. Also, an enhanced expression of RtWRKY1 was detected in plants treated with ABA (Du et al., 2017).

Salinity stress was also tested in recombinant Escherichia coli cells overexpressing a J. curca WRKY. Recombinant cells showed tolerance with significant cell growth under NaCl, mannitol, and KCl supplemented media (Agarwal et al., 2014). It was suggested that these JcWRKY can regulate stress responsive genes and be used to enhance tolerance to abiotic stress.

A study in N. benthemiana overexpressing NbWRKY79 showed promoted tolerant to salinity. A reduced accumulation of reactive oxygen species and increase in activity of antioxidant enzymes during salt treatment was also found. Furthermore, an enhanced ABA-inducible gene expression was detected (Nam et al., 2017).

Drought

In Vitis vinifera it has been shown by stress induction that VvWRKY7, 8 and 28 are up-regulated in response to drought stress by ABA accumulation, which triggers stomata closure, reducing water loss (Wang et al., 2014). The same tolerance is shown in virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of GhWRKY27a, which enhances tolerance to drought stress in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). In addition, GhWRKY27a expression was increased by ABA treatment (Yan et al., 2015).

In tobacco, the ectopic overexpression of TaWRKY1, a wheat WRKY, conferred tolerance to drought, demonstrating that the transgenic tobacco plants exhibited development under stress and, when treated with ABA, the stomata closure rate was increased (Ding et al., 2015). However, overexpression of GhWRKY17 in transgenic N. benthamiana enhanced plant sensitivity to drought and salt stress. No effect of exogenous ABA treatment was detected, since the expression of ABA-inducible genes was also decreased in transgenic lines (Yan et al., 2014).

Studies in transgenic Arabidopsis expressing TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33, a wheat WRKY, revealed tolerance to drought and/or heat stresses (He et al., 2016). Under drought stress, both overexpressing lines showed higher germination rate compared to wild type. However, TaWRKY33 seeds had higher germination rate than TaWRKY1 and wild type plants. Regarding heat stress, TaWRKY33 seeds showed a high survival rate when exposed to 45 °C for 5 hours. Differences between TaWRKY1 and wild type plants were not reported (He et al., 2016). A study in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing GmWRKY54, a soybean WRKY, also detected tolerance to drought stress (Zhou et al., 2008). Plants were withheld from water from 18 days to 3 weeks. When water treatment was recovered, transgenic lines showed up to 85% of survival while wild type plants showed only 30%.

In rice (cv. Sasanishiki), fusion of the gene promoter induced by heat shock HSP101 with the OsWRKY11 gene resulted in overexpression of OsWRKY11 and increased tolerance to drought and heat (Wu et al., 2009).

Heat and cold

Heat stress was also studied in the Arabidopsis for AtWRKY39 gene, which positively regulates the signaling pathways activated by salicylic (SA) and jasmonic (JA) acids and mediates responses to heat stress (Li S et al., 2010). These authors performed a study with mutants featuring the silenced AtWRKY39 gene, and they found an increase in sensitivity to heat stress, a reduction in germination, and a reduction in survival when compared with non-mutated wild type. On the other hand, mutants overexpressing AtWRKY39 had increased heat tolerance compared to the wild type. In this study, the authors also verified the influence of AtWRKY39-induced silencing and overexpression on the expression of other genes. In Atwrky39 plants, AtPR1 (regulated by SA) and AtMBF1c (related to SA) genes showed lower regulation. On the other hand, the overexpression of AtWRKY39 increased the expression of these genes.

Regarding cold stress, a study in Arabidopsis transgenic lines overexpressing CsWRKY46, a cucumber WRKY, showed higher survival rates of freezing seedlings at 4 °C. Hence, tolerance is suggested to be an ABA-dependent process, since an effect of exogenous ABA in transgenic lines was observed (Zhang et al., 2016). Another study with transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing GmWRKY21, a soybean WRKY, also demonstrated enhanced tolerance to cold stress (Zhou et al., 2008). Overexpressing lines were able to survive after 80 minutes under -20 °C, showing a better growth and survival compared to wild type plants.

In rice, overexpression of OsWRKY76 improved tolerance to cold stress at 4 °C (Yokotani et al., 2013). Overexpressing plants showed a significant lower content of ion leakage compared to wild type plants until 72 hours under treatment, demonstrating membrane stability in the overexpressing lines. However, overexpressing lines showed an increased susceptibility to blast fungus (Magnaporthe oryzae), with severe symptoms when infected (Yokotani et al., 2013).

Through transcriptomic analyzes, the involvement of WRKYs in low temperature stress have also been revealed. In paper mulberry cultivated under 4 °C, WRKYs were the second TFs family with expressive changes, comprising 71 genes differentially expressed, for the most part down-regulated (Peng et al., 2015). Hence, the authors suggested that, together with AP2/ERF, bHLH, MYB, and NACs, WRKYs display a central and important role against cold in paper mulberry.

Other stresses

Studies in transgenic Arabidopsis expressing HaWRKY76, a sunflower WRKY, were carried out demonstrating tolerance to flooding (complete submergence) and drought stresses (Raineri et al., 2015). Transgenic plants showed higher biomass, seed production and sucrose content compared to the wild type plants in standard conditions. In addition, when tested under flooding condition, these plants demonstrated tolerance through carbohydrate preservation. In drought stress, the tolerance occurred by stomata closure and via ABA-dependent mechanism. Under both stresses, an increase in seed yield was reported (Raineri et al., 2015).

In rice, OsWRKY89 was reported to confer tolerance to UV-B radiation. When overexpressed, the SA levels were increased, which enhanced the tolerance to UV-B radiation, but also enhanced resistances to pathogen and pest attacks as to blast fungus and white-backed planthopper (Wang et al., 2007).

WRKY and response to biotic stress

WRKY genes are involved in gene signaling for resistance responses to biotic stresses, such as viruses, bacteria, fungi, insects, and nematodes (Figure 1 and Table S2 (123KB, pdf) ). The defense mechanisms are controlled by signaling molecules, such as salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene, or by combinations of these signaling compounds (Schroeder et al., 2001). SA accumulates locally in infected leaves, as well as in non-infected systemic leaves after infection with biotrophic pathogens, and mediates the induced expression of defense genes, resulting in an enhanced state of defense known as systemic acquired resistance (SAR) (Ryals et al., 1996; Adachi et al., 2015).

A study with signal transduction in SA signaling in Arabidopsis, reported that AtWRKY28 and AtWRKY46 are transcriptional activators of AtICS1 (coding for isochorismate synthase, an enzyme that acts in the conversion of chorismate to isochorismate in SA biosynthesis) and AtPBS3 (AVRPPHB SUSCEPTIBLE 3) that plays an important role in SA metabolism (Schroeder et al., 2001). Expression studies with ICS1 promoter::β-glucuronidase (GUS) genes in protoplasts co-transfected with 35S::WRKY28 showed that overexpression of AtWRKY28 resulted in a strong increase in GUS expression. Moreover, RT-qPCR analyses indicated that the endogenous AtICS1 and AtPBS3 genes were highly expressed in protoplasts overexpressing AtWRKY28 or AtWRKY46, respectively. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays identified potential WRKY28 binding sites in the AtICS1 promoter positioned at 445 and 460 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site. Mutation of these sites in protoplast transactivation assays showed that these binding sites are functionally important for activation of the AtICS1 promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays with hemagglutinin-epitope-tagged WRKY28 showed that the region of the AtICS1 promoter containing the binding sites at 445 and 460 bp was highly enriched in the immunoprecipitated DNA (Schroeder et al., 2001).

In the same way, in transgenic lines of Arabidopsis overexpressing VqWRKY52 (Vq- Vitis quinquangularis), resistance to pathogen was found (Wang et al., 2017). VqWRKY52 expression was induced by SA but not by JA treatment. Ectopic expression in Arabidopsis led to resistance to powdery mildew and Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000, but increased susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea (Wang et al., 2017). It was reported that AtWRKY57 acts in an opposite way in Arabidopsis, acting as a negative regulator against an infection depending of JA signaling pathway (Jiang and Yu, 2016). Loss of function of AtWRKY57 enhanced resistance against Botrytis cinerea infection. As shown by chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments, AtWRKY57 regulates positively the transcription of JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN1 (AtJAZ1) and AtJAZ5, which encodes two important repressors of the JA signaling pathway by binding directly to their promoters (Jiang and Yu, 2016).

The modulation of resistance against Rhizoctonia solani in rice, which causes sheath blight disease, was discovered to be controlled by OsWRKY80. OsWRKY80 expression was induced by R. solani infection, JA, and ethylene. OsWRKY80 overexpression and silencing by RNAi, conferred resistance and sensibility, respectively, in response to sheath blight disease through the positive regulation of OsWRKY4 by binding to their W-box or W-box-like sequences (Peng et al., 2016).

NaWRKY3 is required for the elicitation of NaWRKY6 by fatty acid conjugated with amino acids present in the oral secretions of larvae of Manduca sexta. On the other hand, silencing of one or both genes made plants highly vulnerable to herbivores, possibly indicating that both WRKY genes help the plants to differentiate mechanical damage from herbivore attacks (Skibbe et al., 2008).

The AtWRKY23 response to nematode infection in Arabidopsis has been reported. Silencing of AtWRKY23 resulted in low infection of cystic nematode Heterodera schachtii (Grunewald et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis, the heterologous overexpression of OsWRKY23 increased the defense response to Pyricularia oryzae Cav and SA, besides increasing the expression of pathogenesis-related genes (PR) and providing increased resistance to the pathogenic bacteria Pseudomonas syringae (Shaojuan et al., 2009). Studies on overexpression of WRKY genes furthermore indicated that these lines, besides displaying a particular pathogen resistance, also showed tolerance to abiotic stresses (Table S3 (97.1KB, pdf) ).

In Arabidopsis, the constitutive overexpression of the OsWRKY45 transgene confers a number of properties to transgenic plants. These properties include significantly increased expression of PR genes, enhanced resistance to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae tomato DC3000, enhanced tolerance to salt and drought stresses, decreased sensitivity toward ABA signaling during seed germination and post-germination processes, and modulation of ABA/stress-regulated genes during drought induction. In addition, higher levels of OsWRKY45 expression in transgenic plants correlate positively with the strength of the abiotic and biotic responses mentioned above. More specifically, the decreased ABA sensitivities, enhanced disease resistance, and drought tolerances may be attributed, in part, to stomata closure and induction of stress-related genes during drought induction (Qiu and Yu, 2009).

Regarding the WRKY response to pathogens, some results indicate that these genes may have a negative effect on resistance response. Isolated loss-of-function T-DNA insertion mutants and overexpressing lines for AtWRKY48 in Arabidopsis have resulted in enhanced resistance of the loss-of-function mutants that was associated with an increase in salicylic acid-regulated AtPR1 induction by the bacterial pathogen. The growth of a virulent strain of the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae was decreased in wrky48 T-DNA insertion mutants. On the other hand, transgenic WRKY48-overexpressing plants supported enhanced growth of P. syringae, and the enhanced susceptibility was associated with reduced expression of defense-related PR genes (Xing et al., 2008).

A Populus WRKY was also reported to enhance the basal resistance to fungal pathogen. Transgenic P. tomentosa overexpressing P. trichocarpa WRKY89 showed resistance to Dothiorella gregaria, suggesting that PtrWRKY89 acts by accelerating the expression of PR genes in an SA-dependent defense signaling pathway (Jiang et al., 2014).

Transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing PtrWRKY73 (Populus trichocarpa) showed enhanced sensitivity to Botrytis but enhanced resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato strain DC3000 through the regulation of SA-related gene expression (Duan et al., 2015). A negative effect was also observed in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana overexpressing GhWRKY27a, while exhibiting reduced resistance to Rhizoctonia solani infection (Yan et al., 2015). According to Pandey and Somssich (2009), active targeting of WRKY genes or downstream products by pathogens and the coordinated modulation of these factors, which enable the amplification and timing of the plant’s response during infection, can explain the negative effect caused by WRKYs.

Concluding remarks

Most studies regarding the response of transgenic plants overexpressing WRKY genes indicate tolerance to abiotic stresses, resistance to biotic stresses, or both. On the other hand, in studies where WRKY genes have been silenced, a sensitivity reaction to abiotic stresses and susceptibility to biotic stresses was observed. Some rare cases of negative regulation concerning stress were also reported.

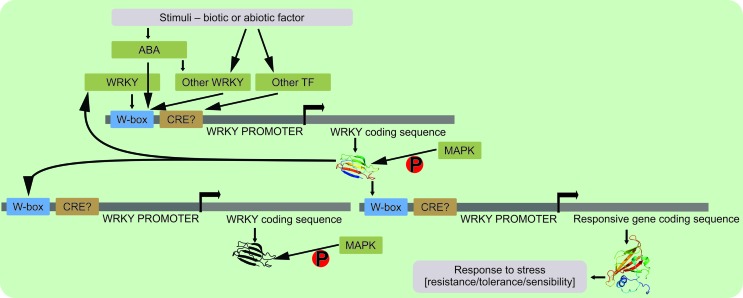

The accurate regulation and fine adjustment of WRKY proteins during plant responses to stress contribute to the establishment of complex signaling networks, and the important roles of WRKY proteins in these networks make them potential candidates for conferring tolerance (Chen et al., 2012) to biotic and abiotic factors. WRKYs can be auto-regulated or regulated by other WRKY members leading to an amplification of their responses (reviewed in Llorca et al., 2014), or prevent WRKY activity (Eulgem 2005) in response to diverse stimuli. However, WRKY transcriptional activation can be a very complex system, since many other TFs from different families can bind to their promoters (Dong et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2015) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Regulatory mechanism of WRKY transcription factors. The signaling pathway starts with an environmental stimulus through ABA signaling or by trans-regulation, which comprise direct transcription factor activation. The trans regulation can occur with a WRKY member, in case of presence of a W-box, or with other TFs from different families. An auto-regulation mechanism can occur, or regulation by promoter binding of a different WRKY member. In some cases, the phosphorylation by an MAPK cascade is a determinant process for the correct WRKY protein function. When activated, WRKY TFs can regulate a different WRKY by binding its W-box sequence, or regulate some other responsive gene conferring tolerance, resistance, or sensibility toward the environmental stimuli.

In addition, considering the large number of genes of the WRKY TF family present in the genome of plant species, WRKY functions and interactions among the family members and WRKY protein kinases in the cascade of signaling need to be clarified.

The development of advanced techniques of molecular biology, such as the combined use of microarrays, immunoprecipitation assays and sequencing techniques, may on a large scale, determine the DNA WRKY protein binding sites and their interaction with other proteins in signaling pathways. In addition, the function of WRKY in plants in response to environmental challenges might be clarified.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq,) and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS).

Supplementary material

The following online material is available for this article:

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Marcio de Castro Silva Filho

References

- Adachi H, Nakano T, Miyagawa N, Ishihama N, Yoshioka M, Katou Y, Yaeno T, Shirasu K, Yoshioka H. WRKY transcription factors phosphorylated by MAPK regulate a plant immune NADPH oxidase in Nicotiana benthamiana . Plant Cell. 2015;27:2645–2663. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi H, Ishihama N, Nakano T, Yoshioka M, Yoshioka H. Nicotiana benthamiana MAPK-WRKY pathway confers resistance to a necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Plant Signal Behav. 2016;11:e1183085. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2016.1183085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal P, Reddy MP, Chikara J. WRKY: Its structure, evolutionary relationship, DNA-binding selectivity, role in stress tolerance and development of plants. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:3883–3896. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal P, Dabi M, Agarwal PK. Molecular cloning and characterization of a group II WRKY transcription factor from Jatropha curcas, an important biofuel crop. DNA Cell Biol. 2014;33:503–513. doi: 10.1089/dna.2014.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai T, Tena G, Plotnikova J, Willmann MR. MAP kinase signaling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature. 2002;415:977–983. doi: 10.1038/415977a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayadi M, Hanana M, Kharrat N, Merchaoui H, Marzoug RB, Lauvergat V, Rebai A, Mzid R. The WRKY transcription factor family in Citrus: Valuable and useful candidate genes for citrus breeding. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2016;180:516–543. doi: 10.1007/s12010-016-2114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitha KC, Ramu SV, Pruthvi V, Mahesh P, Nataraja KN, Udayakumar M. Co-expression of AtbHLH17 and AtWRKY28 confers resistance to abiotic stress in Arabidopsis . Transgenic Res. 2012;22:327–341. doi: 10.1007/s11248-012-9645-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranwal VK, Negi N, Khurana P. Genome-wide identification and structural, functional and evolutionary analysis of WRKY components of Mulberry. Sci Rep. 2016;30794:1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep30794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A, Mittler R, Suzuki N. ROS as key players in plant stress signalling. J Exp Bot. 2013;65:1229–1240. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lai Z, Shi J, Xiao Y, Chen Z, Xu X. Roles of Arabidopsis WRKY18, WRKY40 and WRKY60 transcription factors in plant responses to abscisic acid and abiotic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Song Y, Li S, Zhang L, Zou C, Yu D. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant abiotic stresses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YF, Li LQ, Xu Q, Kong YH, Wang H, Wu WH. The WRKY6 transcription factor modulates PHOSPHATE1 expression in response to low Pi stress in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell. 2009;21:3554–3566. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu X, Wang C, Chen X, Lu W, Li H, Wang X, Hao L, Guo X. The Cotton WRKY Gene GhWRKY41 positively regulates salt and drought stress tolerance in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana . Plos One. 2015;10:e0143022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. The search for physiological substrates of MAP and SAP kinases in mammalian cells. Trends Cell Biology. 1997;7:353–361. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Wang Y, Zhang WH. OsWRKY74, a WRKY transcription factor, modulates tolerance to phosphate starvation in rice. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:947–960. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zelicourt A, Colcombet J, Hirt H. The role of MAPK modules and ABA during abiotic stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nadal E, Ammerer G, Posas F. Controlling gene expression in response to stress. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:833–845. doi: 10.1038/nrg3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding ZJ, Yan JY, Li CX, Li GX, Wu YR, Zheng SJ. Transcription factor WRKY46 modulates the development of Arabidopsis lateral roots in osmotic/salt stress conditions via regulation of ABA signaling and auxin homeostasis. Plant J. 2015;84:56–69. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Chen C, Chen Z. Expression profiles of Arabidopsis WRKY superfamily during plant defense response. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;51:21–37. doi: 10.1023/a:1020780022549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du C, Zhao P, Zhang H, Li N, Zheng L, Wang Y. The Reaumuria trigyna transcription factor RtWRKY1 confers tolerance to salt stress in transgenic Arabidopsis . J Plant Physiol. 2017;4:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Jiang Y, Ye S, Karim A, Ling Z, He Y, Yang S, Luo K. PtrWRKY73, a salicylic acid-inducible poplar WRKY transcription factor, is involved in disease resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:831–841. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1745-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T. Regulation of the Arabidopsis defense transcriptome. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T. Dissecting the WRKY web of plant defense regulators. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e126. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Schmelzer E, Hahlbrock K, Somssich IE. Early nuclear events in plant defence signalling: Rapid gene activation by WRKY transcription factors. EMBO J. 1999;18:4689–4699. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finatto T, de Oliveira AC, Chaparro C, da Maia LC, Farias DR, Woyann LG, Mistura CC, Soares-Bresolin AP, Llauro C, Panaud O, et al. Abiotic stress and genome dynamics: Specific genes and transposable elements response to iron excess in rice. Rice. 2015;8:13. doi: 10.1186/s12284-015-0045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald W, Karimi M, Wieczorek K, Van de Cappelle E, Wischnitzki E, Grundler F, Inzé D, Beeckman T, Gheysen G. A role for AtWRKY23 in feeding site establishment of plant-parasitic nematodes. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:358–368. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.119131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger D, Rezzonico E, Petétot JMC, Somerville C, Poirier Y. Identification and characterization of the Arabidopsis PHO1 gene involved in phosphate loading to the xylem. Plant Cell. 2002;14:889–902. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Li GJ, Yang KY, Mao G, Wang R, Liu Y, Zhang S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 and 6 regulate Botrytis cinerea-induced ethylene production in Arabidopsis . Plant J. 2010;64:114–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Yagi M, Kusano T, Sano H. Rapid systemic accumulation of transcripts encoding a tobacco WRKY transcription factor upon wounding. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;263:30–37. doi: 10.1007/pl00008673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He GH, Xu JY, Wang YX, Liu JM, Li PS, Chen M, Ma YZ, Xu ZS. Drought-responsive WRKY transcription factor genes TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 from wheat confer drought and/or heat resistance in Arabidopsis . BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:116. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0806-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C, Cheng D, Zhang G, Zhu D, Chen Y, Tan M. The role of ZmWRKY4 in regulating maize antioxidant defense under cadmium stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;482:1504–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaguirre MM, Scopel AL, Baldwin IT, Ballaré CL. Convergent responses to stress. Solar ultraviolet-B radiation and Manduca sexta herbivory elicit overlapping transcriptional responses in field-grown plants of Nicotiana longiflora . Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1755–1767. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Yu D. The WRKY57 transcription factor affects the expression of jasmonate ZIM-Domain genes transcriptionally to compromise Botrytis cinerea resistance. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:2771–2782. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Duan Y, Yin J, Ye S, Zhu J, Zhang F, Lu W, Fan D, Luo K. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the Populus WRKY transcription factor family and analysis of their expression in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:6629–6644. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CY, Zhang S. Activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade induces WRKY family of transcription factors and defense genes in tobacco. Plant J. 2004;38:142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J, Giraudat J. Abscisic acid signal transduction. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:199–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MY, Xu ZS, Tian C, Huang Y, Wang F, Xiong AS. Genomic identification of WRKY transcription factors in carrot (Daucus carota) and analysis of evolution and homologous groups for plants. Sci Rep. 2016;15:23101. doi: 10.1038/srep23101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Song A, Li Z, Fan F, Liang Y. Transcriptome analysis in leaves of rice (Oryza sativa) under high manganese stress. Biologia. 2017;72:388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zhou X, Chen L, Huang W, Yu D. Functional characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY39 in heat stress. Mol Cells. 2010;29:475–483. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Yang W, Liu D, Han Y, Zhang A, Li S. Ectopic expression of a grapevine transcription factor VvWRKY11 contributes to osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis . Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:417–427. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QN, Liu Y, Xin ZZ, Zhang DZ, Ge BM, Yang RP, Wang ZF, Yang L, Tang BP, Zhou CL. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the WRKY gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2017;71:212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZQ, Yan L, Wu Z, Mei C, Lu K, Yu YT, Liang S, Zhang XF, Wang XF, Zhang DP. Cooperation of three WRKY-domain transcription factors WRKY18, WRKY40, and WRKY60 in repressing two ABA-responsive genes ABI4 and ABI5 in Arabidopsis . J Exp Bot. 2012;63:6371–6392. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorca CM, Potschin M, Zentgraf U. bZIPs and WRKYs: Two large transcription factor families executing two different functional strategies. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao G, Meng X, Liu Y, Zheng Z, Chen Z, Zhang S. Phosphorylation of a WRKY transcription factor by two pathogen-responsive MAPKs drives phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell. 2011;23:1639–1653. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y, Smykowski A, Zentgraf U. A novel upstream regulator of WRKY53 transcription during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Biol. 2008;10:110–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda N, Ohme-Takagi M. Functional analysis of transcription factors in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1232–1248. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanta TK, Park YH, Bae H. Novel genomic and evolutionary insight of WRKY transcription factors in plant lineage. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37309. doi: 10.1038/srep37309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan RM, Chory J, Ecker JR. Signaling in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2793–2795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam TN, Thia LH, Mai DS, Tuan NV. Overexpression of NbWRKY79 enhances salt stress tolerance in Nicotiana benthamiana . Acta Physiol Plant. 2017;39:121. [Google Scholar]

- Niu CF, Wei W, Zhou QY, Tian AG, Hao YJ, Zhang WK, Ma B, Lin Q, Zhang ZB, Zhang JS, et al. Wheat WRKY genes TaWRKY2 and TaWRKY19 regulate abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:1156–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osakabe Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K, Tran LSP. Sensing the environment: key roles of membrane-localized kinases in plant perception and response to abiotic stress. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:445–458. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SP, Somssich IE. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1648–1655. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pater S, Greco V, Pham K, Memelink J, Kijne J. Characterization of a zinc-dependent transcriptional activator from Arabidopsis . Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4624–4631. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Wu Q, Teng L, Tang F, Pi Z, Shen S. Transcriptional regulation of the paper mulberry under cold stress as revealed by a comprehensive analysis of transcription factors. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0489-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Wang H, Jang JC, Xiao T, He H, Jiang D, Tang X. OsWRKY80-OsWRKY4 module as a positive regulatory circuit in rice resistance against Rhizoctonia solani. Rice. 2016;9:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12284-016-0137-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest HD, Filichkin SA, Mockler TC. Cis-regulatory elements in plant cell signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phukan UJ, Jeena GS, Shukla RK. WRKY transcription factors: Molecular regulation and stress responses in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:760. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu JL, Fii BK, Petersen K, Nielsen HB, Botanga CJ, Thorgrimsen S, Palma K, Suarez-Rodriguez MC, Sandbech-Clausen S, Lichota J, et al. Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 regulates gene expression through transcription factor release in the nucleus. EMBO J. 2008;27:2214–2221. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Yu D. Over-expression of the stress-induced OsWRKY45 enhances disease resistance and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis . Environ Exp Bot. 2009;65:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Raineri J, Ribichich KF, Chan RL. The sunflower transcription factor HaWRKY76 confers drought and flood tolerance to Arabidopsis thaliana plants without yield penalty. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:2065–2080. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde A, Kurup S, Holdswoth M. ABI3 emerges from the seed. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:418–419. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01736-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton PJ, Torres JT, Parniske M, Wernert P, Hahlbrock K, Somssich IE. Interaction of elicitor-induced DNA-binding proteins with elicitor response elements in the promoters of parsley PR1 genes. EMBO J. 1996;15:5690–5700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton PJ, Somssich IE, Ringler P, Shen QJ. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton DL, Tripathi P, Rabara RC, Lin J, Ringler P, Boken AK, Langum TJ, Smidt L, Boomsma DD, Emme NJ, et al. WRKY transcription factors: Key components in abscisic acid signalling. Plant Biotechnol J. 2012;10:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryals JA, Neuenschwander UH, Willits MG, Molina A, Steiner HY, Hunt MD. Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1809–1819. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Kwak JM, Allen GJ. Guard cell abscisic acid signaling and engineering drought hardiness in plants. Nature. 2001;410:327–330. doi: 10.1038/35066500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Yan L, Liu ZQ, Cao Z, Mei C, Xin Q, Wu FQ, Wang XF, Du SY, Jiang T, et al. The Mg-chelatase H subunit of Arabidopsis antagonizes a group of WRKY transcription repressors to relieve ABA-responsive genes of inhibition. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1909–1935. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.073874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh AH, Eschen-Lippold L, Pecher P, Hoehenwarter W, Sinha AK, Scheel D, Lee J. Regulation of WRKY46 transcription factor function by mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis thaliana . Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Liu C, Zhang Y, Meng X. OsWRKY30 is activated by MAP kinases to confer drought tolerance in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;80:241–253. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9941-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Yao J, Sun J, Chang L, Wang S, Ding M, Qian Z, Zhang H, Zhao N, Sa G, et al. Populus euphratica HSF binds the promoter of WRKY1 to enhance salt tolerance. Plant Sci. 2015;235:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh Y, Ziv Y. The ATM protein kinase: regulating the cellular response to genotoxic stress, and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:197–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibbe M, Qu N, Galis I, Baldwin IT. Induced plant defenses in the natural environment: Nicotiana attenuata WRKY3 and WRKY6 Coordinate responses to herbivory. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1984–2000. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Palmqvist S, Olsson H, Borén M. A novel WRKY transcription factor, SUSIBA2, participates in sugar signaling in barley by binding to the sugar-responsive elements of the iso1 promoter. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2076–2092. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulker B, Somssich IE. WRKY transcription factors: From DNA binding towards biological function. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Hou X, Tang J, Wang Z, Wang S, Jiang F, Li Y. A novel cold-inducible gene from Pak-choi (Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis), BcWRKY46, enhances the cold, salt and dehydration stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:4553–4564. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Hao J, Chen X, Hao Z, Wang X, Lou Y, Peng Y, Guo Z. Overexpression of rice WRKY89 enhances ultraviolet B tolerance and disease resistance in rice plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;65:799–815. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Vannozzi A, Wang G, Liang YH, Tornielli GB, Zenoni S, Cavallini E, Pezzotti M, Cheng ZM. Genome and transcriptome analysis of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) WRKY gene family. Horticult Res. 2014;1:14106. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2014.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Guo R, Tu M, Wang D, Guo C, Wan R, Li Z, Wang X. Ectopic expression of the wild grape WRKY transcription factor VqWRKY52 in Arabidopsis thaliana enhances resistance to the biotrophic pathogen powdery mildew but not to the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea . Front Plant Sci. 2017;31:97. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Shiroto Y, Kishitani S, Ito Y, Toriyama K. Enhanced heat and drought tolerance in transgenic rice seedlings overexpressing OsWRKY11 under the control of HSP101 promoter. Plant Cell Rep. 2009;28:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0614-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Ruas P, Shen QJ. Regulatory networks of the phytohormone abscisic acid. Vitam Horm. 2005;72:235–269. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)72007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing DH, Lai ZB, Zheng ZY, Vinod KM, Fan BF, Chen ZX. Stress-and pathogen-induced Arabidopsis WRKY48 is a transcriptional activator that represses plant basal defense. Mol Plant. 2008;1:459–470. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Xu X, Zhang L, Wu P, Chen Y, Li M, Jiang H, Wu G. Genome-wide analysis of the WRKY gene family in physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.) Gene. 2013;524:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki K, Kigawa T, Inoue M, Tateno M, Yamasaki T, Yabuki T, Aoki M, Seki E, Matsuda T, Yasuko T, et al. Solution structure of an Arabidopsis WRKY DNA binding domain. Plant Cell. 2005;17:944–956. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Jia H, Chen X, Hao L, An H, Guo X. The cotton WRKY transcription factor GhWRKY17 functions in drought and salt stress in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana through ABA signaling and the modulation of reactive oxygen species production. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:2060–2076. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Jia H, Wang F, Wang C, Shuchang L, Xingqi G. Overexpression of GhWRKY27a reduces tolerance to drought stress and resistance to Rhizoctonia solani infection in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana . Front Physiol. 2015;6:265. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokotani N, Sato Y, Tanabe S, Chujo T, Shimizu T, Okada K, Yamane H, Shimono M, Sugano S, Takatsuji H, et al. WRKY76 is a rice transcriptional repressor playing opposite roles in blast disease resistance and cold stress tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:5085–5097. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Ligang C, Liping Z, Diqiu Y. Overexpression of OsWRKY72 gene interferes in the abscisic acid signal and auxin transport pathway of Arabidopsis . J Biosci. 2010;35:459–471. doi: 10.1007/s12038-010-0051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang L, Gu L, Ringler P, Smith S, Rushton PJ, Shen QJ. Three WRKY transcription factors additively repress abiscisic acid and gibberellin signaling in elleurone cells. Plant Sci. 2015;236:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Jin J, Tang L, Zhao Y, Gu X, Gao G, Luo J. Plant TFDB 2.0: update and improvement of the comprehensive plant transcription factor database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;39:1114–1117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Wang X, Bi Y, Zhang C, Fan YL, Wang L. Isolation and functional analysis of transcription factor GmWRKY57B from soybean. Chin Sci Bull. 2008;53:3538–3545. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang L. The WRKY transcription factor superfamily: Its origin in eukaryotes and expansion in plants. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yu H, Yang X, Li Q, Ling J, Wang H, Gu X, Huang S, Jiang W. CsWRKY46, a WRKY transcription factor from cucumber, confers cold resistance in transgenic-plant by regulating a set of cold-stress responsive genes in an ABA-dependent manner. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;108:478–487. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZL, Xie Z, Zou X, Casaretto J, Ho TD, Shen QJ. A rice WRKY gene encodes a transcriptional repressor of the gibberellin signaling pathway in aleurone cells. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1500–1513. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.034967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Wang NN, Gong SY, Lu R, Li Y, Li XB. Overexpression of a cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) WRKY gene, GhWRKY34, in Arabidopsis enhances salt-tolerance of the transgenic plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;96:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou QY, Tian AG, Zou HF, Xie ZM, Lei G, Huang J, Wang CM, Wang HW, Zhang JS, Chen SY. Soybean WRKY-type transcription factor genes, GmWRKY13, GmWRKY21, and GmWRKY54, confer differential tolerance to abiotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2008;6:486–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.