Abstract

Self-assembled DNA nanostructures have attracted significant research interest in biomedical applications because of their excellent programmability and biocompatibility. To develop multifunctional drug delivery from DNA nanostructures, considerable key information is still needed for clinical application. Traditional fixed endpoint assays do not reflect the dynamic and heterogeneous responses of cells with regard to drugs, and may lead to the misinterpretation of experimental results. For the first time, an integrated time-lapse live cell imaging system was used to study the cellular internalization and controlled drug release profile of three different shaped DNA origami/doxorubicin (DOX) complexes for three days. Our results demonstrated the dependence of DNA nanostructures on shape for drug delivery efficiency, while the rigid 3D DNA origami triangle frame exhibited enhanced cellular uptake capability, as compared with flexible 2D DNA structures. In addition, the translocation of released DOX into the nucleus was proved by fluorescence microscopy, in which a DOX-loaded 3D DNA triangle frame displayed a stronger accumulation of DOX in nuclei. Moreover, given the facile drug loading and auto fluorescence of the anti-cancer drug, DOX, our results suggest that the DNA nanostructure is a promising candidate, as a label-free nanocarrier, for DOX delivery, with great potential for anticancer therapy as well.

Table of Content

DNA origami nanostructures can serve as a promising carrier for drug delivery due to the outstanding programmability and biocompatibility.

Introduction

Doxorubicin (DOX), one of the most effective cytotoxic drugs, has been widely used in chemotherapy regimens against a variety of cancers.1 Unfortunately, it presents numerous challenges to clinical practice. Of particular concern are its multidrug resistance, adverse side effects, and low specificity to tumor cells.2 Together, these factors seriously impede its application in cancer treatment. In recent years, to overcome these issues, various materials (such as metal nanoparticles, liposomes, and synthetic polymers) are being utilized to facilitate anticancer drug delivery and to reduce drug side effects.3–8

DNA origami nano-objects, bottom-up self-assembled artificial DNA structures, have shown promise as candidates for drug delivery because of their superior structural programmability and natural biocompatibility.9–10 In addition, there is facile intercalation of DOX between adjacent DNA base pairs for loading drugs.11–12 Previous work has shown that DOX packed by DNA origami nanostructures can circumvent drug resistance and selectively accumulate in tumor cells to enhance drug delivery efficiency.13–16 However, as a new member of nanocarriers, considerable key information is needed to use this approach in clinical applications. This includes elucidation of the mechanism of drug release from DNA origami, quantification of drug cellular distribution, and the influence of the geometry of DNA architectures on drug delivery efficiency.17–18 Typically, conventional fluorescence microscopy is the major method used to investigate the drug intracellular uptake and release behaviour of DOX/DNA origami complexes in cells. It is commonly based on a snapshot analysis after each fixation and, consequently, dynamic and heterogeneous cell responses are not reflected and temporal resolution is lacking. Unfortunately, this may lead to misinterpretation of experimental results. Fluorescence microscopy uses a traditional light source (e.g., mercury/xenon arc lamp) that allows for continuous imaging of drug delivery systems in live cells. However, the disadvantages of this system (non-uniform illumination across the field of view, lamp intensity decay over time, and photo toxicity) prevent long-term observation of actual fluorescence signals of DOX in live cells.19–20 Therefore, to overcome these limitations, a facile method capable of providing accurate and uninterrupted observations of drug release in a live cell over a period of several days or weeks is highly desired. The temporal information obtained is critical for the unambiguous understanding of the drug delivery mechanism. Further, it can provide key guidance for designing new drug delivery systems.

For the first time, our current study describes the use of EVOS fluorescence auto microscopy (Thermo Fisher), with an integrated onstage incubator, to monitor the DOX/DNA origami dynamic internalization process and the subsequent DOX release in a live breast cancer cell, MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 1). This system eliminates the complexities of microscopy. Also, the light emitting diode (LED) technology in the system can provide a stable, repeatable light source and, importantly, sample damage is reduced during characterization. DNA origami nanostructures, with different morphologies (2D cross, 2D rectangle, and 3D triangle), were studied in order to dissect the drug internalization and release profiles, and to identify the impact of their distinct shapes on the efficiency of drug delivery. The collected quantitative data demonstrated that the DOX-loaded 3D DNA origami triangle (DOX-3DOT) exhibited greater enhanced drug delivery capability and sustained drug release, as compared to the performance of two other DOX-loaded 2D shapes (rectangle: DOX-2DOR, and cross: DOX-2DOC). In addition, nucleus tracking also demonstrated that more DOX, released from DOX-3DOTs in lysosomes and other cell compartments, is able to diffuse into the nucleus to interrupt DNA replication. Our results suggest that optimization of DNA origami design is a critical step toward improving the efficiency of drug delivery.

Fig. 1.

Scheme illustration of different shapes of DNA origami nanocarriers for DOX delivery. The mixture of virus strand (M13mp18) and hundreds of staple strands were annealed to form 2D cross, 2D rectangle, and 3D triangle DNA origami, which were loaded with DOX and administered to MDA-MB-231 cell lines, respectively. Time-lapse images were captured by the EVOS live cell imaging system, the excitation was set to 480 nm, and red channel images were captured from 550 nm–700 nm.

Results and discussion

The characterization of DNA origami nanocarriers

Fig. 1 schematically illustrates the DOX/DNA origami drug delivery system and the principle of using EVOS fluorescence auto microscopy to track DOX release for a single live cell.

Three different shaped DNA origami nanostructures were employed as DOX carriers in this study, including a 2D rectangular origami (2DOR),21 a 2D cross-shaped origami (2DOC),22 and a newly designed 3D triangular DNA origami frame (3DOT).23 After being subjected to a single-step thermal annealing process, the fabricated DNA origami nanostructures were incubated with DOX to allow for drug loading. DNA origami nanostructures, before and after DOX loading, were characterized by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), agarose gel electrophoresis, dynamic light scattering (DLS), and fluorescence spectroscopy. As can be seen in Fig. 2A, the direct visualization of the three DNA origami shapes by AFM revealed that, upon intercalation of DOX, the DOX/DNA origami complexes (bottom lane) exhibited morphologies, similar to those of pure DNA origami structures (top lane, additional AFM images of 3DOT shown in Figure S1A). This indicated that the integrity of a DNA nanostructure is maintained after drug loading. Also, this was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2B), which showed that DOX-loaded complexes appeared as single bands, with slightly slower mobility, than those of the corresponding pure DNA origami nanostructures, due to DOX intercalation. In addition, the hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of unloaded and DOX-loaded DNA origami structures were characterized by DLS. These results demonstrate that hydrodynamic sizes of all three DNA origami shapes are uniformly distributed: ~ 50 nm with sharp DLS peaks (Fig. S1B). The measurements of zeta potential show that DNA origami nanostructures, with an initially negative charge (−20 ~ −30 mV), turn to a positive charge (+5~10 mV) after drug loading (Fig. 2c and Fig. S1C), thereby indicating the successful intercalation of DOX molecules into the DNA origami. Furthermore, the intercalation of DOX with DNA origami nanostructures, based on the quenching effect of DNA towards DOX, was also investigated by using a fluorescence spectrometer.24 As evident in Fig. 2D, sequential decreases in the fluorescence intensity of DOX were observed when a fixed amount of DOX (1 mM) was incubated with increasing amounts of 3DOTs (1.25 nM to 5 nM). A similar phenomenon was also observed with DOX-2DOR and DOX-2DOC, as shown in supplementary Fig. S1D.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of DNA origami and DOX/DNA origami complexes. (A) AFM images of different shapes of DNA origami and drug-loaded DNA origami. (Scale bar: 100 nm). (B) Agarose gel image of DNA origami and DOX (0.25 mM)/DNA origami (5 nM). Lane 1: 2DOC; lane 2: DOX-2DOC; lane 3: 2DOR; lane 4: DOX-2DOR; lane 5: 3DOT; lane 6: DOX-3DOT. (C) Zeta-potential of 3DOT (red peak) and DOX (1.0 mM)-3DOT(5 nM) (green peak). (D) The fluorescence spectra of DOX (1.0 mM) with varied concentrations of 3D triangle DNA origami.

Doxorubicin loading and releasing in vitro

Considering the effect of temperature changes on the winding of DNA duplexes, (that may affect the intercalation of DOX into DNA), we incubated a mixture of DOX and each type of DNA origami structure at two temperatures (25 °C and 37 °C) for 24 h to evaluate drug loading efficiency. Loading efficiency was calculated by measuring the free DOX before and after loading. As depicted in Fig. 3A, three different DNA origami shapes (cross, rectangle, and triangle) loaded 68.3%, 71.8 %, and 70.5% of DOX, respectively, at 25 °C. While at 37 °C, the DOX loading percentages were 85.8%, 86.2%, and 86.3% for corresponding origami shapes, which is ~ 15% higher than those obtained at 25 °C. Part of the reason for this efficiency elevation may be due to 1) enhanced accessibility of DOX to less tightly linked DNA duplexes at an elevated temperature; 2) Increased thermodynamic activity between DNA nanostructures and DOX molecules. Therefore, 37 °C was set as our incubation temperature of drug loading.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of drug loading and release efficiency of DNA origami nanostructures. (A) Drug loading efficiency of three different shapes of DNA origami incubated with DOX at 25 °C and 37 °C for 24 h, respectively. The 37 °C groups showed approximately 85% efficiency while the 25 °C groups showed 70%. The error bar represents the standard deviation of three independent measurements for each group; (B) DOX release profile from triangle DNA origami (DOX incubation at 37 °C). The accumulated release showed that the DNA origami with acidic triggered release.

Given that the controlled and efficient release of drugs at a target site is essential for an ideal drug delivery system, a study was conducted in vitro of the release kinetic profiles of DOX/DNA origami complexes. Three different pH values (pH=4.5, 6.6, and 7.4), that mimic intracellular and physiological conditions, were tested to demonstrate pH influence on the release of DOX from DNA origami. Fig. 3B shows that the pH-sensitive drug release capability of the 3DOT at 37 °C. The results reveal that DOX release exhibited a two-phase profile: an initial burst release: that occurred within the first 6 h, was followed by a slower rate of release. A comparison of results obtained under tested pH conditions clearly shows that DOX was released very slowly from the DNA origami in both neutral (pH 7.4) and acidic (pH 6.6) environments. Release efficiencies were around 25% over a period of 48 h. When the pH dropped to 4.5, approximately 50% of DOX was released within 48 h, which was a higher release than that at both pH 7.4 and pH 6.6. This observation indicates that the release of DOX from DNA origami carriers is acid-responsive.14 In addition, an investigation was conducted on the impact of the geometric shapes of DNA origami nanocarriers on DOX release. As shown in Fig. S2, the 3DOT displayed a greater DOX release at pH 4.5, 37 °C, as compared to both 2DOR and 2DOC. This higher release may be attributed to the structural features of triangular DNA origami: a honey-comb design with internal cavities of each edge, which increases the accessible surface area for DOX loading and release.8,15

In vitro cytotoxicity of a DOX-loaded DNA nanostructure system

The MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line was examined by MTT assay (with PBS buffer as control) to assess the effects of the cytotoxicity of free DOX, three different shapes of DNA origami, and drug loaded DNA origami. As can be seen in Fig. 4A, the DNA origami nanostructures exhibited no obvious cytotoxicity towards the cells. Almost 100% of the cells were still viable after a 4-day incubation with DNA origami, which confirmed the excellent biocompatibility of DNA nanostructures to cells. Fig. 4B shows the in vitro cytotoxic effect of the DOX-loaded DNA origami nanostructures. The results reveal that all three types of DOX/DNA origami complexes exhibited a cytotoxicity effect on the breast cancer cells that was similar to that of free DOX. The viability of the breast cancer cells depended on the DOX concentration. With an increasing DOX concentration (from 0.01 µM to ~1.0 µM), the cell viability dropped down to ~20–30%, and even further down, to less than 15%, when the DOX concentration reached 5 µM. Moreover, the study of cytotoxicity showed that the DOX-3DOT complex had a lower IC50 value (IC50=0.07859 µM) than the 2D complexes (DOX-2DOR: IC50=0.1005 µM, DOX-2DOC: IC50=0.1118 µM). This indicates that the cell inhibition efficiency of DOX-3DOT is higher than those of the 2D complexes, and affirms that the geometry of DNA nanostructures significantly impacts drug delivery efficiency, which is consistent with previous studies.11–15

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxicity of DNA origami and DOX-loaded DNA origami nanocarriers. (A) Varying concentration of three different shapes of DNA origami (PBS as control) were administrated to MDA-MB-231 cells for 4 days, followed by MTT assays (n=10). It indicated no cytotoxicity of the DNA origami nanostructures. (B) Cell viability of MDA-MB-231 cells after administration with varied concentrations of DOX and DOX-loaded DNA origami for 4 days. Then the values of IC50 were calculated.

Time-lapse live cell imaging of cellular uptake of DOX/DNA origami complexes

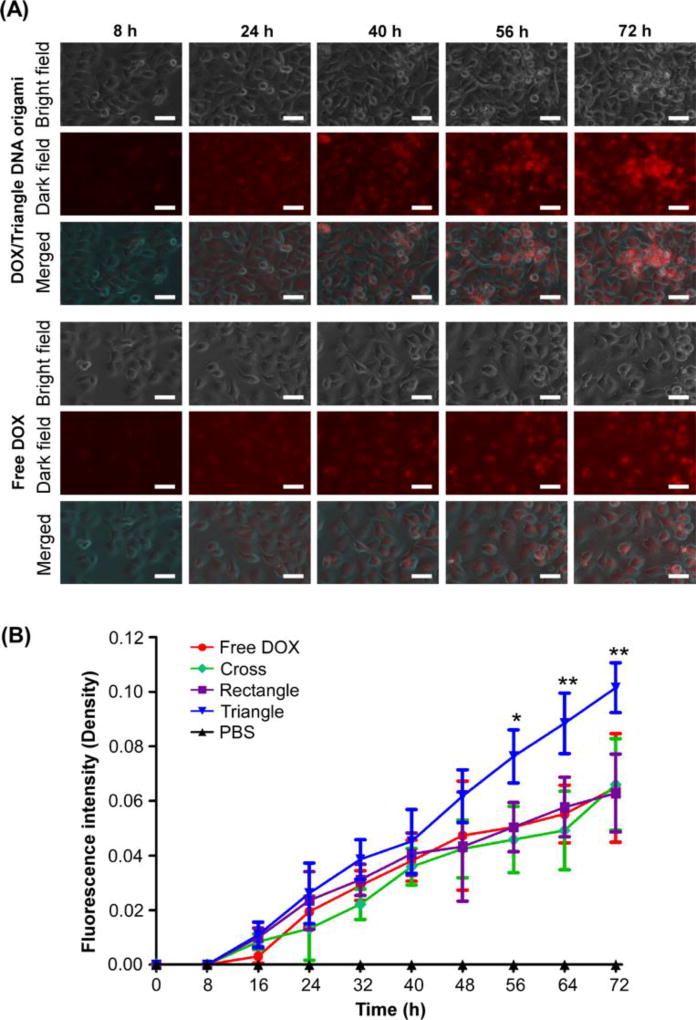

An investigation was made to determine the cellular internalization of DOX/DNA origami complexes and their sequential drug release within live cells in real time. The Invitrogen EVOS FL Auto Time-Lapse Imaging System with Onstage Incubator (Thermo Fisher) was employed to visualize the in situ process in MDA-MB-231 cells. First, the cells were seeded in a culture dish and incubated in a DMEM 1640 medium for 24 h. Then, the cells were transferred into 24-well plates (50, 000 cells/well) and exposed to free DOX, and DOX/DNA origami complexes (the final concentration of DOX was 2 µM) for further incubation and automatic image capture every 20 mins. It is evident, from the images in Fig. 5 and Fig. S3, that fluorescence intensity of DOX in all samples gradually increased in whole cells, with an extended incubation time of up to 72 h. This indicated that the DOX/DNA origami complexes could be successfully internalized in MDA-MB-231 cells. And that DOX could be sequentially released in a time-dependent manner. Moreover, the cellular uptake of DOX/DNA origami complexes was quantified as a function of time by using fluorescence yields obtained by normalizing integrated fluorescence intensities to the cellular area. As shown in Fig. 5B, the fluorescence intensity of cells exposed to DOX-2DOR and DOX-2DOC increased at a rate similar to that of cells incubated with free DOX. However, in the cells incubated with DOX-3DOT, the increasing rate of fluorescence intensity was markedly higher than that of those treated with 2D structures and free DOX, and the fluorescence intensity was statistically significant (56 h, *P<0.05; 64 h and 72 h, **P<0.01, n=40) after incubation for 56 h. This suggests that DOX-3DOT complexes have higher internalization capabilities and can maintain a longer sustained drug release than 2D DOX/DNA origami complexes. This is likely due to specific structural features of the 3D DNA origami triangular frame (rigid edges and sharp vertices) which implies a higher chance that the structures could adhere to cancer cell surfaces and be more easily internalized by cells than 2D structures. Our results are consistent with earlier published studies.25

Fig. 5.

Cellular uptake of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with free DOX and DOX-loaded DNA origami (A) In vitro time-lapse live cell imaging of DOX-loaded 3D triangular DNA origami and free DOX by using the EVOS cell imaging system. The images were captured every 20 mins, and the picked time point was shown as 8, 24, 40, 56, and 72 h, respectively. The bright field, dark field, and merged images are illustrated. Scale bar: 20 µm. (B) The quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity of intercellular DOX. The 3D triangle DNA origami showed the strongest fluorescence intensity of statistical significance after 56 h incubation (*P<0.05 and **P<0.01).

Intracellular localization of DOX in nuclei

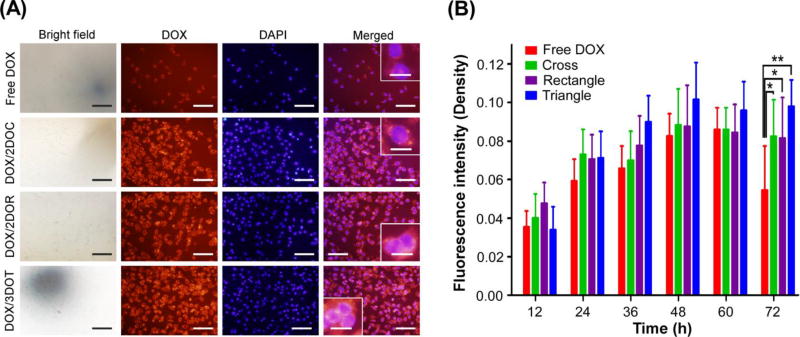

Several studies11,13 have reported that DNA origami nanocarriers can be uptaken by endocytic pathways, and reside in endocytotic vesicles (e.g., lysosomes) where the acidic environment can trigger DOX release from degraded DNA nanostructures. Therefore, to further explore the intracellular localization of DOX, we tracked the diffusion profile of DOX in nuclei with fluorescence microscopy, after staining with DAPI. Fig. 6A presents the fluorescence image of MDA-MB-231 cells after they were incubated with free DOX and DOX-3DOT in DMEM for 72 h. It is clear from the merged images of co-localization of DOX and the nuclei that DOX fluorescence signals distributed in and around nuclei, suggesting that the released DOX diffused into nuclei and accumulated there. A quantitative analysis of fluorescence yields in nuclei (shown in Fig. 6B) reveals that the fluorescence yields in the cells, treated with free DOX, increased with time and reached a maximum after about 60 hours of incubation. A gradual decrease followed. In contrast, fluorescence yields in DOX-DNA origami treated cells peaked at 48 h, and maintained a similar level during the remaining hours. This was significantly higher than it was in free DOX treated cells for 72 h. Moreover, the result also indicated that, among DOX/DNA complexes, the fluorescence intensity of cells treated with DOX-3DOT was higher than that in DOX-2DOR, and DOX-2DOC treated cells. This revealed the higher cellular uptake efficiency of DOX-3DOT, with subsequent release and progressive accumulation of DOX in cell nuclei, which supports the previous results obtained from in vitro time-lapse live cell imaging.

Fig. 6.

Localization of DOX in nucleus. (A) Bright-field and fluorescence images of DAPI stained MDA-MB-231 cells treated with the same concentration of DOX/DNA origami and free DOX for 72 h. The red fluorescence of DOX was captured in red channel and DAPI stained nuclei was captured in blue channel. The overlapping images demonstrated the co-localization of DOX and nuclei, indicating the diffusion of DOX into nuclei and accumulation. (PBS was used as the negative control). Scale bar: 100 µm, scale bar in zoomed area: 20 µm. (B) The quantitative analysis of fluorescence images of DAPI stained MDA-MB-231 cells treated with DOX/ DNA origami and free DOX from 12 h to 72 h. The fluorescence intensity of DOX was calculated in the cell nucleus region via the red channel. All of the DOX-loaded DNA origami groups demonstrated enhanced DOX accumulation in cell nuclei, as compared with that of free DOX. (cross and rectangle *P<0.05, triangle **P<0.01).

Experimental

Materials

DNA origami staple strands were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc, stored in 96-well plates with a concentration of 100 µM, and were used without further purification. Single-stranded M13mp18 viral DNA was purchased from Bayou Biolabs. DOX and Polyethylene Glycol 8000 (PEG8000) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. Cell culture consumables were purchased from Corning, Inc. Centrifugal Filters (100 KDa MWCO) were purchased from Pall, Inc. The MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). All the cells were cultured in DMEM 1640 medium (Corning, Inc., USA) with 10% of FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., USA) under 37 °C with 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Self-assembly of DNA origami nanostructures

DNA origami nanostructures were prepared by following the Rothemund’s method with modification.9 Briefly, M13mp18 viral DNA (20 nM) and staple strands were mixed at a 1:5 ratio in a 1× TAE/Mg2+ buffer (pH 8.0, 40 mM of Tris-HCl, 20 mM of acetic acid, 2 mM of EDTA and 12.5 mM of Mg2+). The mixture was annealed by slowly cooling from 90 °C to 16 °C over the course of 12 h in a thermocycler (Eppendorf). Upon annealing, the DNA origami was purified using the PEG8000 method to remove excess staple strands,26 and it was finally stored at 4 °C until further use. For the PEG purification procedure, the DNA nanostructures were mixed with PEG8000 (15% final concentrations) and centrifuged twice at 13,000 g for 30 min to remove the free DNA strands. The concentrations of DNA origami were calculated by measuring the UV absorbance of 260 nm (Ultrospec 9000, Biochrom, USA).

Formation of DOX/DNA origami complexes

DOX/DNA origami complexes were prepared by mixing DNA origami nanostructures (5.0 nM) and DOX (1 mM) together. The mixture was incubated at 25 °C (or 37 °C) for 24 h. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 15,800 g for 15 min, and then the supernatant containing free DOX was collected and the concentration of free DOX was calculated at an absorbance of 485 nm, based on a known standard curve. The precipitation (DOX/DNA origami complexes) was stored and re-suspended in a PBS buffer for further use.

Characterization of DNA origami nanostructures

Agarose gel electrophoresis

Prepared DNA origami nanostructures and DOX/DNA origami complexes were characterized by 0.8% agarose gel in a 1× TAE/Mg2+ buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM of acetic acid, 2 mM of EDTA, and 12.5 mM of magnesium acetate) at 50 V and room temperature. The concentration of DNA origami, and intercalated DOX is 5 nM, and 0.25 mM, respectively.

Atomic force microscopy

AFM images were obtained in tapping mode in air with a Nanoscope IIIa (Digital Instruments). Typically, a 5 µl of a sample solution was spotted onto freshly cleaved muscovite mica (Ted Pella, Inc.) and absorbed for approximately 30 sec. To remove buffer salts, the mica surface was rinsed three times with DI-water (30 µl). The drop was then wiped off with a kimwipe, and further blow-dried with compressed air.

Dynamic light scattering

The size distribution and zeta-potential of DNA origami and DOX/DNA origami complexes were measured with a DLS analyzer (Zetasizer ZS90, Malvern, UK). The DNA origami, before DOX loading, was diluted in 500 µL of a 1× TAE buffer with 12.5 mM Mg2+, and injected into a plastic cuvette to measure size distribution and zeta-potential. This procedure was repeated three times.

DOX release from DNA origami nanostructures

The DOX release experiments were conducted by re-suspending DOX/DNA origami precipitation in 1.0 ml of phosphate buffer at pH 4.5, 6.8, and 7.4, respectively, followed by incubation at 37 °C. The data was collected at time points of 1, 3, 6, 24, 48 h (for the pH 7.4 condition, the time was extended to 72 h to ensure the complete release of DOX). At each time point, the origami/DOX complexes were centrifuged at 15,800 g for 15 min, and the amount of the concentration of DOX released from the DNA origami nanostructure was determined by measuring the UV absorbance of DOX in a supernatant at 485 nm. The new buffer was refilled for the next time point measurement. Each data was shown as average ± SD (n=3).

Fluorescence spectrometer

Fluorescence was used as an indicator to monitor controlled DOX release. The concentrations of DOX were fixed to 1.0 mM, and mixed with varied concentrations of DNA origami (1.25, 2.50, 3.75, 5.00 nM). The fluorescence of DOX/DNA origami complexes, as well as free DOX, was measured with a fluorescence spectrometer (Nanodrop 3300, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The excitation wavelength was set to 485 nm, and the emission was recorded from 500 to 650 nm.

Cell viability assay

The MDA-MB-231 cells were transferred into a 96-well plate with 3,000 cells per well. The cells were treated with varied concentrations of DOX/DNA origami complexes (0.01–5 µM DOX concentration), as well as free DOX (0.01–5 µM), and then cultured at 37 °C (pure DNA origami and PBS were treated as negative controls (n=3)). After 4 days, when the cells (treated with 0 µM DOX) occupied the whole well, 100 µl of WST-8 (100 µM) was added to each well. After further culturing for 2 h, the cell culture medium was abandoned, and the absorbance of the solutions in the wells was measured at 495 nm with a multi-mode microplate reader (Synergy H4, BioTec, USA) to determine cell viability.

In vitro time-lapse live cell imaging

The MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in a DMEM 1640 medium containing 10% FBS at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were then transferred into 24-well plates (50,000 cells per well). The DOX/DNA origami complexes and free DOX were diluted to 100 µM with PBS buffer (in DNA origamis/DOX samples, calculated as DOX), and 1.0 ml was added to each well. The EVOS cell imaging system (EVOS FL Auto, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to monitor intracellular drug internalization, and to choose a phase and RFP channels for 72-h incubation. The focus was set as an automatic option, and fluorescence photographs were taken every 20 min. The fluorescence images were used to make movies and analyzed quantitatively by measuring the fluorescence intensity, which were recorded, and the data of the different samples were compared.

Cell nucleus staining

Cell nucleus staining was used to determine the DOX distribution in cell nucleus. The MDA-MB-231 cells were transferred into a 96-well-plate at a density of 10,000/well. After the cells adhered to a plate, 100 µl of DOX-loaded DNA origami or free DOX (the same concentration (2.0 µM) of DOX, in a DMEM 1640 medium containing 10% FBS) were added to the wells (PBS solution was used as negative control.). The observation time points were set as 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h. At each time point, the used medium in each well was removed, and the wells were washed three times with PBS. Then, the cells were fixed with 100 µl of 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 10 min. After the residual paraformaldehyde was removed and the cells were washed with PBS, 100 µL of 1×DAPI (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., USA) were added to each well to stain the cell nucleus for 5 mins. Then, the cells were washed three times with PBS. The bright field and fluorescence images were captured by fluorescence microscopy (DP71, Olympus, Japan) in both blue and red channels, which were excited by a 365 nm UV lamp and a 520 nm green lamp, respectively. The number of quantitative analyzed cells is 199, 133, 159, and 37 corresponding to triangle, rectangle, cross, and free DOX, respectively. The fluorescence intensity of DOX in nucleus was quantified via two channels. First, the location of nucleus with DAPI stain was recorded in blue channel (DAPI emission, 454 nm); Second, the image was exposed in red channel (DOX emission, 595 nm) and merged with DAPI stained image; Finally, according to the borders of cell nucleus in blue channel, the signal of DOX in nucleus region was separated from the whole cell, then the fluorescence intensity of DOX in nucleus was quantified, and compared with the different samples.

Statistical analysis

All of the data were represented by three independent measurements. Statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data for different groups were treated by using a one-way ANOVA to determine statistical significance, which was indicated by the *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Conclusions

Long-term single-cell imaging is an advanced technique that can provide a dynamic profile of molecular interaction, which can lead to many important biological discoveries.19 In this study, time-lapse live cell imaging was used to investigate the cellular internalization of DOX/DNA origami complexes and, for the first time, to track drug release for up to 3 days. Our results unambiguously demonstrate that drug delivery efficiency depends on the shape of DNA nanostructures: the rigid 3D DNA origami triangle frame exhibited enhanced cellular uptake capability with sustained drug release compared with flexible 2D DNA structures. In addition, the translocation of released DOX into the nucleus was proved by fluorescence microscopy, in which a DOX-loaded 3D DNA triangle frame displayed a stronger accumulation of DOX in nuclei. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that drug loading efficiency of DNA origami nanostructures can be increased ~15% at an elevated incubation temperature (37 °C), compared to the room temperature that is normally accepted in literature.11,13 The effective and accurate dissection of the impact of distinct shapes of DNA nanostructures on drug delivery efficiency will provide valuable information to identify the more promising structures for biomedical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by University of Missouri Research Board, Material Research Center and Center of Biomedical Research of Missouri S&T to R. W. This study was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grants R01 CA178831 and CA191785, Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Breakthrough Level II grant BC151845 to L. X. The authors would like to thank Dr. Daniel Forciniti and Ke Li for assistance of fluorescence measurement, and Dr. Yuewern Huang for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hortobagyi GN. Drugs. 1997;54:1. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199700544-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottesman MM. Annu. Rev. Med. 2002;53:615. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang M, Fan K, Zhou M, Duan D, Zheng J, Yang D, Feng J, Yan X. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:14900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407808111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu C, Zhou M, Zhang X, Wei W, Chen X, Zhang X. Nanoscale. 2015;7:5683. doi: 10.1039/c5nr00290g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai X, Luo Y, Zhang W, Du D, Lin Y. ACS appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:22442. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b04933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Annu. Rev. Med. 2012;63:185. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-040210-162544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gul-e-Saba, Abdullah MA. Biotechnology and Bioinformatics: Advances and Applications for Bioenergy, Bioremediation, and Biopharmaceutical Research. 2015:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Ouyang J, Kong J, Zhong W, Xing MM. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:3108. doi: 10.1021/am400017q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothemund PW. Nature. 2006;440:297. doi: 10.1038/nature04586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angell C, Xie S, Zhang L, Chen Y. Small. 2016;12:1117–1132. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q, Jiang Q, Li N, Dai L, Liu Q, Song L, Wang J, Li Y, Tian J, Ding B, Du Y. ACS Nano. 2014;8:6633. doi: 10.1021/nn502058j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H, Yang H, Hao X, Xu H, Lv Y, Xiao D, Wang H, Tian Z. Small. 2013;9:2639. doi: 10.1002/smll.201203127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halley PD, Lucas CR, McWilliams EM, Webber MJ, Patton RA, Kural C, Lucas DM, Byrd JC, Castro CE. Small. 2016;12:308. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang Q, Song C, Nangreave J, Liu X, Lin L L, Qiu D, Wang Z-G, Zou G, Liang X, Yan H, Ding B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13396. doi: 10.1021/ja304263n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y-X, Shaw A, Zeng X, Benson E, Nyström AM, Högberg Br. ACS nano. 2012;6:8684. doi: 10.1021/nn3022662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song L, Jiang Q, Liu J, Li N, Liu Q, Dai L, Gao Y, Liu W, Liu D, Ding B. Nanoscale. 2017;9:7750. doi: 10.1039/c7nr02222k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao J, Liu H, Su S, Wang L, Huang W, Fan C. Small. 2014;10:4626. doi: 10.1002/smll.201401309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pei H, Zuo X, Zhu D, Huang Q, Fan C. Accounts Chem. Res. 2013;47:550. doi: 10.1021/ar400195t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skylaki S, Hilsenbeck O, Schroeder T. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:1137. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aswani K, Jinadasa T, Brown CM. Microscopy Today. 2012;20:22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang R, Nuckolls C, Wind SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2012;51:11325. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W, Zhong H, Wang R, Seeman NC. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2011;50:264. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu W, Li L, Yang S, Gao J, Wang R. Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23:14177. doi: 10.1002/chem.201703927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu G, Zheng J, Song E, Donovan M, Zhang K, Liu C, Tan W. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:7998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220817110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bannunah AM, Vllasaliu D, Lord J, Stolnik S. Mol. Pharm. 2014;11:4363. doi: 10.1021/mp500439c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stahl E, Martin TG, Praetorius F, Dietz H. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2014;53:12735. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.