Abstract

Background:

Prior research shows between-race differences in women’s knowledge and emotions related to having dense breasts, thus suggesting that between-race differences in behavioral decision-making following receipt of breast density (BD) notifications are likely. Guided by the theory of planned behavior, this study examined differences in emotion-related responses (i.e., anxiety, worry, confusion) and behavioral cognition (e.g., intentions, behavioral attitudes) following receipt of BD notifications among African American (AA) and European American (EA) women. This study also examined whether race-related perceptions (i.e., discrimination, group-based medical mistrust), relevant knowledge and socioeconomic status (SES) explained the between race differences.

Method:

Michigan women (N = 457) who presented for routine screening mammogram and had dense breasts, no prior breast cancer diagnoses, and had screen-negative mammograms were recruited from July, 2015 to March 2016. MANOVA was used to examine between race differences in psychological responses (i.e., emotional responses and behavioral cognition), and a multi-group structural regression model was used to examine whether race-related constructs, knowledge and SES mediated the effect of race on emotional responses and behavioral cognition. Prior awareness of BD was accounted for in all analyses.

Results:

AA women generally reported more negative psychological responses to receiving BD notifications regardless of prior BD awareness. AA women had more favorable perceptions related to talking to their physicians about the BD notifications. Generally, race-related perceptions, SES, and related knowledge partially accounted for the effect of race on psychological response. Race-related perceptions and SES partially accounted for the differences in behavioral intentions. Between-race differences in emotional responses to BD notifications did not explain differences in women’s intentions to discuss BD notifications with their physicians.

Conclusions:

Future examinations are warranted to examine whether there are between-race differences in actual post-BD notification behaviors and whether similar race-related variables account for differences.

Keywords: United States, Breast density, Physician communication, Racial difference

1. Introduction

Having dense breasts (i.e., more fibro-glandular relative to fatty breast tissue) increases women’s breast cancer (BC) risk up to 4.5-fold (Barlow et al., 2006; Boyd et al., 2011; McCormack & dos Santos Silva, 2006); however, many women are often unaware of their own breast density (BD) and the associated increased BC risk (Manning et al., 2013; O’Neill et al., 2014; Rhodes et al., 2015; Trinh et al., 2015). Consequently, BD notification laws, which mandate that mammogram reports disclose when a patient has dense breasts, have been adopted in 27 states in the United States thus far (Are You Dense Advocacy Inc, 2016). These laws have been passed with little scientific consensus regarding appropriate follow-up screening recommendations (Haas and Kaplan, 2015; Ray et al., 2015), presenting significant challenges when it comes to advising women who receive the notifications (Brower, 2013; Smith, 2013). These challenges are particularly concerning because of their potential contribution to BC incidence and mortality disparities which disadvantage African American (AA) women compared to European American (EA) women (DeSantis et al., 2016a, 2016b). Between-race differences in women’s BD-related cognition and emotion (Manning et al., 2016a) suggest downstream differences in supplemental BC screening decision-making following receipt of BD notification - differences which would likely continue to disadvantage AA women (e.g., Curtis et al., 2008; Press et al., 2008). However, such differences have not yet been examined. Thus, the purpose of the current analysis is to examine differences in, and predictors of, psychological responses and behavioral decision-making following receipt of BD notifications among AA and EA women.

1.1. Barriers that influence BC screening and decision-making

Barriers that hinder BC screening among AA women and that contribute to racial disparities in BC screening behaviors may also contribute to between-race differences in behavioral decision-making following receipt of BD notifications. Such barriers are particularly important given their contribution to racial disparities in BC mortality. AA women are more likely to present with later stage disease, have lower survival rates at each stage of disease, and have a 42% higher BC mortality rate overall compared to EA women (DeSantis et al., 2016a), and these disparities are related to differences in BC screening behaviors. Disparities in mortality have been attributed to inadequate mammography screening among AA women (Curtis et al., 2008; Smith-Bindman et al., 2006) and to between-race differences in time to followup screening after an abnormal screening mammogram (Jones et al., 2005; Press et al., 2008). Socioeconomic barriers such as low income and lack of transportation; psychological barriers such as poor knowledge about breast cancer screening and lack of medical trust; and systemic barriers such as lack of physician recommendations all demonstrably hinder BC screening among minority women (Alexandraki and Mooradian, 2010).

For this study, the focus was on the influences of perceived past discrimination and medical mistrust; knowledge of BC and BD; socioeconomic status (SES); and psychological responses to receiving BD notifications on EA and AA women’s attitudes and intentions related to discussing the notification with their physicians.

1.1.1. Pre-existing factors

The study considered discrimination, mistrust, knowledge, and SES as pre-existing factors that were already present prior to psychological responses that are contextually bound to receiving BD notification.

1.1.2. Race-related perceptions

Race-related perceptions (e.g., perceptions of discrimination and medical mistrust) adversely affect health and health care of racial and ethnic minorities (Dovidio et al., 2008; Penner and Dovidio, 2016; Penner et al., 2009; Smedley et al., 2003). Perceptions of discrimination are associated with lower adherence to cancer screening behaviors generally (Facione and Facione, 2007; Shariff-Marco et al., 2010), and perceived medical discrimination and medical mistrust contribute to decreased adherence to breast cancer screening guidelines specifically (Crawley et al., 2008; Thompson et al., 2004). This study recognizes that discrimination and medical mistrust are distinct constructs; however, to be succinct, we treat them as race-related perceptions, and it is expected these perceptions will attenuate behavioral intentions for AA women.

1.1.3. Knowledge

Prior research indicates that, compared to EA women, AA women have less knowledge of BD and are less likely to be told about BD by their physicians (Manning et al., 2013, 2016a). Knowledge deficits and lack of physician recommendations are related to AA women’s decreased adherence to BC screening guidelines (Alexandraki and Mooradian, 2010; Coleman and O’Sullivan, 2001; Young and Severson, 2005); similar dynamics would likely attenuate AA women’s intentions to discuss notifications with physicians.

1.1.4. SES

SES factors (e.g., income, education) are documented barriers to BC screening (Alexandraki and Mooradian, 2010) and have been shown to account for EA women’s greater knowledge of BD (Manning et al., 2013). It is expected that SES would be positively associated with women’s behavioral intentions.

Altogether, these pre-existing factors (i.e., race-related perceptions, knowledge, and SES) are expected to account for between-race differences in intentions to discuss BD notification with physicians.

1.1.5. Psychological responses

This study examined how the effects of pre-existing factors on intentions are mediated by women’s psychological responses (e.g., anxiety, worry, confusion) to BD notification. Moderate levels of BC anxiety and worry facilitate, whereas high levels hamper BC screening intentions and behaviors (Consedine et al., 2004; Hay et al., 2006; McCaul et al., 1996). Data show that compared to EA women, AA women have more anxiety related to their BD; however, anxiety attenuates AA women’s intentions to discuss notifications with physicians whereas it increases similar intentions for EA women (Manning et al., 2016a, 2016b). Thus, it is expected that AA women would have less favorable intentions, and that anxiety would partially account for between-race differences in intentions; this study examined whether worry and confusion similarly accounted for between-race differences.

1.1.6. Race-related perceptions mediation

Perceived discrimination is linked to negative psychological states (e.g., stress, anxiety, etc.), which hinder behaviors that promote health and well-being (Carter et al., 2016; Mouzon et al., 2017; Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009; Williams and Mohammed, 2009). This study examined whether race-related perceptions influenced psychological responses to BD notifications and, in turn, affected behavioral intentions.

1.1.7. Knowledge mediation

Knowledge attenuates anxieties related to colorectal cancer screening (Honda and Gorin, 2005) and colposcopy (Bekkers et al., 2002; Bosgraaf et al., 2013); hence, knowledge may similarly attenuate anxiety related to BD notification. Since AA women have less BD knowledge (Manning et al., 2013, 2016a), there is a plausible mediational path where less prior BD knowledge among AA recipients results in greater BD related anxiety, which in turn weakens their intentions to discuss BD notifications with physicians.

More knowledge should also be related to less confusion about the BD notification; however, this study did not identify any research indicating whether there were between-race differences in the relation between confusion about a health topic and communicating with one’s physician. Hence, this study explored whether BD-notification confusion mediated the relation between race and intentions.

1.1.8. SES mediation

Finally, upon receiving BD notifications, women with fewer resources and thus more concerns about follow up testing may have more negative psychological responses to BD notifications (e.g., anxiety regarding cost of follow-up care) and thus weaker behavioral intentions. Hence, the study examined whether hypothesized effects of SES on behavioral intentions were mediated by women’s psychological responses to the notifications.

1.2. Theoretical model

This study used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB: Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen, 2011) to frame the model regarding the translation of relevant pre-existing factors and psychological responses to behavioral intentions. The TPB is a well-validated model that has been used successfully in the prediction of health behaviors (e.g., Conner and Sparks, 1996; Hardeman et al., 2002). Though there are no official behavioral guidelines for BD notification recipients, some notification messages clearly indicate that additional screening may be warranted (Haas and Kaplan, 2015; Siu, 2016), implying a behavioral target of BD notifications. In fact, initial epidemiological studies have shown that supplemental BC screening rates increased following the introduction of BD notification laws (Destounis et al., 2015; Weigert and Steenbergen, 2012, 2015), indicating that the notifications are changing behaviors.

In the TPB, behaviors are directly predicted by behavioral intentions and actual behavioral control (though in practice, perceived behavioral control is typically used as a proxy for actual behavioral control). Intentions themselves are directly predicted by behavioral attitudes (positive or negative evaluations of engaging in the behavior), perceptions of descriptive norms (what you see others do) and injunctive norms (what you think others want you to do), and perceptions of behavioral control (PBC: how much control you think you have in doing the behavior). Attitudes, norms and PBC are respectively influenced by beliefs about behavioral outcomes, motivations to comply with and pay attention to relevant others, and beliefs about behavioral impediments. The TPB proposes that other cognitive and emotional factors (e.g., information and knowledge, emotions, discrimination) affect behavioral intentions indirectly via attitudes, norms and PBC (Ajzen, 2012; Ajzen et al., 2007). The TPB provides a parsimonious theoretical model to examine women’s behavioral decision making, and between-race differences in decision making, following receipt of BD notifications.

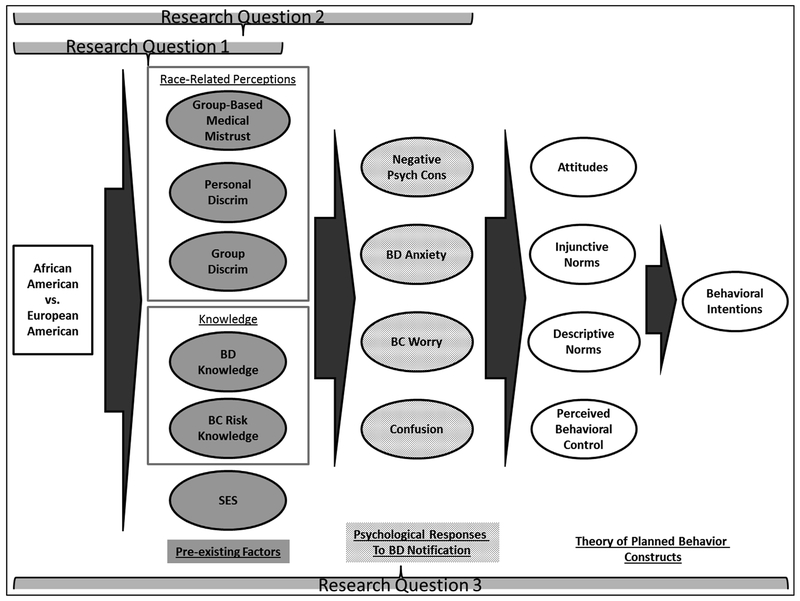

The study’s decision-making model is outlined in Fig. 1. Between-race differences in pre-existing factors were proposed to be translated to differences in psychological responses to BD notifications. In turn, between-race differences in psychological responses translated to differences in behavioral intentions via processes outlined by the TPB. Specifically, the study examined support for the following hypotheses among a sample of women who received BD notifications in the state of Michigan:

Fig. 1:

Theoretical model.

H1. Compared to EA women, AA women will report (a) heightened psychological responses (e.g., greater anxiety) to BD notifications and (b) less favorable attitudes and intentions to discuss the notification with their physicians.

H2. The effect of women’s race on psychological responses will be mediated by race-related perceptions, relevant knowledge, and SES.

H3. The effects of pre-existing factors and psychological responses on behavioral intentions will be mediated by TPB processes (i.e., attitudes, norms and PBC).

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedures

Eligible women were recruited beginning one month after the introduction of the BD notification law in the state of Michigan (July, 2015). Women were eligible if they presented for routine screening mammogram and had dense breasts (i.e., Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System [BI-RADS] density categories c or d), had no prior BC diagnoses, and had screen-negative mammograms (i.e., BI-RADS assessment categories 0, 1 or 2) (D’Orsi et al., 2013). Between July, 2015 and March, 2016, invitations were mailed to 2676 women who received BD notifications to participate in a study examining women’s “opinions and perspective on some information that was included in your mammogram report”; 557 women replied (21% response rate). No further information was available on women who declined to participate; yet, the response rate is consistent with similar studies among this population (Manning et al., 2013, 2016a).

Median income for AA and EA women in the study ($30,000 to $39,900 and $90,000 to $99,900, respectively) was higher than that for the population ($26,100 and $50,900, respectively). While this difference may represent selection bias based on income, it is important to note that the ranges of income were similar between race, indicating that the selection bias was not differential by the primary predictor of interest (i.e., race). Thus, the income-based selection bias would have little to no effect on the direct or indirect effects of race reported below. Upon reading an information sheet, participants completed all survey materials via a secure online research platform (Qualtrics, 2015), which likely explains the respondents’ relatively higher income (i.e., due to internet access). Participants received a $25 gift certificate in exchange for their time; the respondents’ relatively higher income suggests that the study incentive did not result in a disproportionally higher number of lower income women. The analysis sample consisted of 452 women who identified as either AA or EA and who indicated whether they were aware of their BD prior to receiving the notification. The study was approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. TPB variables

The specific behavior assessed was “Talking to my doctor (i.e., primary care, ob/gyn, etc.) about the notification regarding the density of my breasts within the next three months ...” (see Supplementary Appendix A for all survey items). All item responses were on a 7-point scale, with some items reverse scored to address biased responding due to respondent acquiescence. Two items assessed behavioral intentions (r = 0.43, p < 0.001). The mean of 5 semantic differential items assessed behavioral attitudes (α = 0.80). Injunctive norms were assessed with two items (r = 0.60, p < 0.001). Descriptive norms were assessed with two items (r = 0.46, p < 0.001). One item was used to assess PBC.

2.3. Psychological responses

BD-Related Anxieties.

The study design adapted 12 items assessing negative psychological consequences of mammogram (Cockburn et al., 1992) to assess three dimensions of negative emotionality related to learning BD. Women indicated how often they experienced several symptoms when they thought about how dense their own breasts were on a scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“quite a lot of the time”). Four items assessed the physical dimension (α = 0.86); five items assessed the emotional dimension (α = 0.93); and three items assessed the social dimension (α = 0.85) of negative emotionality.

The study also used a one-item general BD anxiety question (“How anxious do you get when you think about how dense your own breasts are?”) with responses on a scale from 1 (“not at all anxious”) to 10 (“very anxious”).

2.3.1. BC worry

One item (“How often do you worry about breast cancer?”) was used to assess BC worry, with responses from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“all of the time”).

2.3.2. Confusion

Three items assessed general confusion, behavioral confusion, and confusion about risk with responses from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

2.4. Race-related perceptions

2.4.1. Group-based medical mistrust (GBMM)

GBMM was assessed by the 12-item Group-based Medical Mistrust Scale (Thompson et al., 2004), which yields 3 dimensions of GBMM: Lack of support (3 items; α = 0.61); Group discrimination (3 items; α = 0.88); and Suspicion (6 items; α = 0.88). Women responded on a scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”).

2.4.2. Personal and group discrimination

Personal and Group discrimination were each indicated by responses to the following items respectively: “Have you ever experienced discrimination against yourself personally in the following areas?” and “How much are individuals of your ethnic/racial group discriminated against in the following areas?” Women responded by indicating on a scale 1 (never) to 5 (all the time) in the areas of obtaining work, wages/pay, obtaining loans or credit, health care, and obtaining health insurance. The mean of the items was used to create a personal (α = 0.88) and group-based (α = 0.96) discrimination score.

2.5. Knowledge

2.5.1. BC risk knowledge

The study assessed BC risk knowledge using methods similar to McMenamin et al. (2005). Women indicated whether each of 15 items (e.g., age, BRCA1/2 mutations, etc.) “decrease”, “have no effect on”, or “increase” women’s risk of breast cancer. The proportion of items correct out of items attempted was taken as BC risk knowledge score.

2.5.2. BD knowledge

Participants responded to the item “In your own words, what is breast density? Even if you are unsure what breast density is, please give it your best guess.” Three trained coders assessed response accuracy from 1 (“not at all correct”: e.g., “The space from my chest and the nipple”) to 4 (“quite accurate for a lay person”: e.g., “Dense breasts have less fat and more glandular tissue”). The mean across coders was used to indicate BD knowledge (α = 0.81).

2.6. Demographics

2.6.1. Race

Participants indicated race from among 8 options, including “two or more race” and “Other”; participants who indicated “Black or African American” or “White or Caucasian American” were included for analyses. Race was dummy-coded for analysis (1 = AA; 0 = EA).

2.6.2. SES

Socioeconomic status was indicated by three variables: income, marital status, and education. Participants indicated income categorically in ranges of $10,000 (e.g., Less than $9999; $10,000 - $19,999, etc.). Participants categorically indicated their highest education level and their marital status. To facilitate model fitting for analyses described below, each SES indicator was aggregated as follows: Income was dichotomized at the median ($50,000 to $59,999); education was aggregated into three categories (high school; higher education; graduate or professional school); marital status was aggregated into three categories (married or partnered; separated, widowed or divorced; single or never married). Marital status was considered a part of SES given the economic benefit associated with marriage and given some preliminary analyses which showed unique effects of marital status on the outcomes considered here when controlling for income. Women also reported whether they “currently have health insurance coverage”; but, since 97% of all women reported having health insurance, this variable was not included in analyses.

2.6.3. Age

Participants indicated their numerical age. Age was rescaled (divided by 10) for path analyses.

2.7. Planned analyses

2.7.1. Between-race differences in emotional outcomes, confusion and TPB variables

MANOVA was used to examine the effect of race on negative emotionality, BD anxiety, BC worry, and the three areas of confusion. Since it was generally expected that effects would be influenced by women’s prior awareness of their BD, the main effect of prior BD awareness and interactions between race and prior awareness was also controlled for in all analyses. A similar MANOVA was used to examine effects of race on the TPB variables.

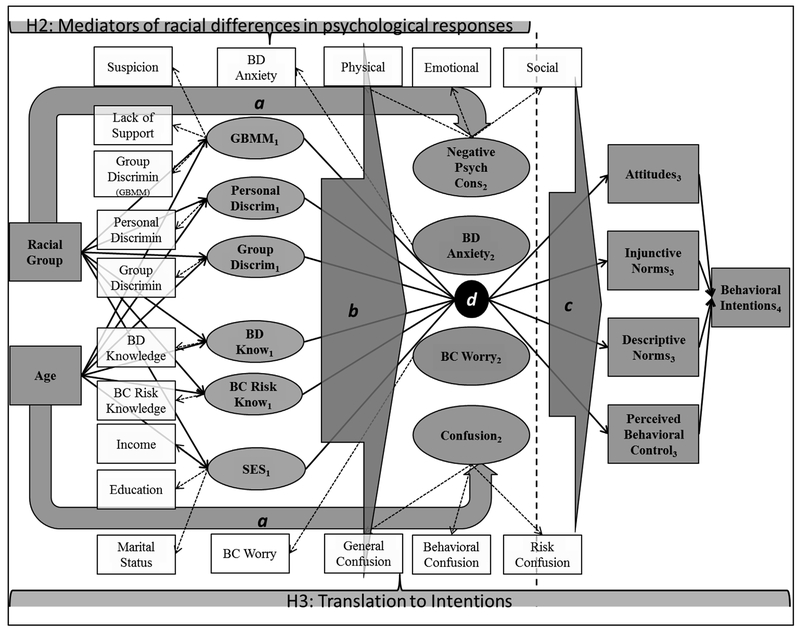

2.7.2. Mediators of racial differences in psychological responses

A multi-group structural regression model was fit to examine whether race-related constructs, knowledge, and SES mediated the effect of race on psychological responses to BD notification (see Fig. 1). Prior awareness of one’s BD (yes vs. no) served as the groups for analyses. The analysis used lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) implemented with R (R Core Team., 2016) to fit the model. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used in light of missing data: 120 cases (27%) had some missing data, which comprised 3.4% of all observations. Initially, an invariant model was fit where all parameters were constrained to be equivalent between groups; following, a variant model with all parameters were freely estimated was fit, with the exception of factor loadings (i.e., there was no theoretical reason to expect group differences in factor loadings for the measurement models). Significant improvement in model fit indicates that the parameter estimates vary based on prior BD awareness. The structural regression approach was taken due to increased parsimony provided by the regressions among the latent constructs. Model specification is presented in Fig. 2. Standard errors were estimated for each indirect effects (i.e., the product of paths from predictor to mediator and from mediator to outcome) via the Delta method (Oehlert, 1992; Rosseel, 2015) and were examined between group differences in direct and indirect effects.

Fig. 2:

Structural regression models for hypotheses 2 and 3. Note: Boxes represent observed variables; ovals represent latent constructs; dashed arrows Indicate factor loadings for measurement models; grey and black solid arrows Indicate direct effects (i.e., regression coefficients). Grey shaded objects represent constructs and paths specified to test theoretical relations. Residual correlations were specified among similarly subscripted endogenous constructs. To increase interpretability of the figure, a, b, c and d were used to represent direct effects as follows: shaded arrows a indicate direct effects from racial group and age to each psychological response (2); shaded arrow b indicates direct effects specific from each preexisting factor (1) to each psychological response (2); shaded arrow c indicates direct effects specified from each psychological response (2) to each TPB predictor (3) of behavioral intentions; dark circle d indicates direct effects specified from each pre-existing factor (1) to each TPB predictor (3). Vertical dashed line indicates where H2 model was extended for test of H3

2.7.3. Translation to intentions

The multi-group structural regression model was expanded by including the TPB predictors and intentions as endogenous variables to examine how much attitudes, norms, and PBC translated pre-existing factors and psychological responses to behavioral intentions (see Fig. 2 for model specification). The model was specified so that distal factors only influenced intentions indirectly via the proximal TPB predictors (the analysis was limited to this stringent representation of the TPB in the working model due to sample size considerations). Indirect effects of race were examined on the TPB predictors and were (1) singularly mediated by each preceding variable and (2) serially mediated by paths from race to pre-existing factors to psychological responses. Finally, guided by the results of (1) and (2), the indirect effects of race on behavioral intentions was examined.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics for pre-existing factors

This sample consisted of 211 (47%) EA and 241 (53%) AA women. Most women (266; 59%) reported no prior awareness of BD; however, significantly more EA women reported prior awareness ([58% vs. 26%], χ2(1) = 48.03, p < 0 0.01). Results of Mann-Whitney U indicated that median income (“$30K to $39.9K”) and education (“some college”) for AA women were significantly lower than income (“$90K to S99.9K”) and education (“college graduate”) for EA women. EA women were more likely to be married (72% vs. 36%), whereas AA women more likely to be single ([34% vs. 6%], χ2(2) = 71.08, p < 0.01). AA women had lower BC risk knowledge, lower BD knowledge, greater scores on all GBMM subscales, and reported more group-based and personal discrimination ([p’s for all t’s < 0.01; see Table 1]; a 2 [Race: AA vs EA] by 2 [Prior BD awareness: Yes vs. No] MANOVA indicated no main effects of prior awareness or any interactions with race on any of the outcomes).

Table 1:

Between race differences in pre-existing factors.

| EA | AA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t** | df | |

| BC Risk Knowledge | 0.65 | 0.13 | 0.54 | 0.15 | 8.73 | 447 |

| BD Knowledge | 2.29 | 0.68 | 1.91 | 0.67 | 5.64 | 401 |

| GBMM - Suspicion Subscale | 1.69 | 0.84 | 2.52 | 1.08 | −9.04 | 442 |

| GBMM - Group Disparity | 2.56 | 1.35 | 3.69 | 1.55 | −8.12 | 441 |

| GBMM - Lack of Support | 2.06 | 0.90 | 3.11 | 1.12 | −10.79 | 442 |

| Group-based Discrimination | 1.77 | 0.69 | 3.14 | 0.93 | −17.43 | 437 |

| Personal Discrimination | 1.32 | 0.53 | 1.88 | 0.84 | −8.26 | 437 |

Note. AA = African American. EA = European American.

All ps < 0.01.

3.2. Between-race differences in responses to BD notifications

Full results of the race by prior BD awareness MANOVAs are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Results indicated significant main effects of race: AA women indicated more physical, social, and emotional negative emotionality and greater BD anxiety (see top panels Table 2 for the implied means of the model). There were also significant main effects of prior BD awareness: Women who already knew their BD reported lower physical and marginally lower emotional negative emotionality and less confusion. Prior awareness interaction was significant for only one race, such that prior awareness alleviated general confusion more for AA women than EA women. Nonetheless, AA women generally reported more negative psychological responses to receiving BD notifications regardless of prior BD awareness. Results of the second MANOVA indicated main effects of race and of prior BD awareness on all TPB variables except for PBC (bottom panels Table 2). Intentions, attitudes, and normative perceptions were more favorable among women with no prior awareness and, in contrast to the hypotheses, more favorable among AA women. There were no significant interactions between race and prior BD awareness: the effects of race persisted regardless of prior BD awareness (see Supplementary Appendix B).

Table 2:

MANOVA modeled effects of race and prior BD awareness psychological responses and planned behavior constructs.

| Variable | Racial Group | Prior BD Awareness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Race | Prior Awareness | Interaction | ||||

| M | SE | M | SE | F1,419 | F1,419 | F1,419 | ||

| Psychological Responses | ||||||||

| Negative Emotionality – Physical | EA | 1.19 | 0.06 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 22.01** | 4.48* | 0.72 |

| AA | 1.51 | 0.04 | 1.34 | 0.07 | ||||

| Negative Emotionality – Social | EA | 1.17 | 0.06 | 1.17 | 0.05 | 18.67** | 0.63 | 0.61 |

| AA | 1.48 | 0.05 | 1.38 | 0.07 | ||||

| Negative Emotionality – Emotional | EA | 1.38 | 0.08 | 1.24 | 0.07 | 19.00** | 2.96† | 0.06 |

| AA | 1.69 | 0.06 | 1.58 | 0.09 | ||||

| BD Anxiety | EA | 3.52 | 0.31 | 3.10 | 0.26 | 4.57* | 0.12 | 1.13 |

| AA | 3.84 | 0.23 | 4.05 | 0.37 | ||||

| BC Worry | EA | 2.49 | 0.10 | 2.72 | 0.08 | 0.71 | 1.38 | 1.73 |

| AA | 2.54 | 0.07 | 2.52 | 0.11 | ||||

| Risk Confusion | EA | 3.11 | 0.13 | 2.63 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 16.53** | 0.00 |

| AA | 3.08 | 0.09 | 2.59 | 0.15 | ||||

| Behavior Confusion | EA | 3.43 | 0.12 | 3.08 | 0.10 | 1.33 | 9.45** | 0.03 |

| AA | 3.29 | 0.08 | 2.97 | 0.14 | ||||

| General Confusion | EA | 2.92 | 0.12 | 2.67 | 0.10 | 0.87 | 21.16** | 6.23* |

| AA | 3.31 | 0.09 | 2.49 | 0.14 | ||||

| TPB Variables | F1,418 | F1,418 | F1,418 | |||||

| Intentions | EA | 5.20 | 0.16 | 4.75 | 0.14 | 12.28** | 4.08* | 0.81 |

| AA | 5.60 | 0.12 | 5.43 | 0.19 | ||||

| Attitudes | EA | 5.74 | 0.12 | 5.16 | 0.10 | 12.65** | 11.08** | 2.83† |

| AA | 5.96 | 0.09 | 5.77 | 0.14 | ||||

| Injunctive Norms | EA | 5.09 | 0.17 | 4.52 | 0.14 | 5.83* | 11.95** | 0.00 |

| AA | 5.47 | 0.13 | 4.92 | 0.20 | ||||

| Descriptive Norms | EA | 5.12 | 0.14 | 4.74 | 0.12 | 10.66** | 9.82** | 0.06 |

| AA | 5.58 | 0.10 | 5.14 | 0.16 | ||||

| PBC | EA | 5.98 | 0.15 | 6.17 | 0.13 | 1.28 | 1.98 | 0.01 |

| AA | 5.80 | 0.11 | 6.02 | 0.18 | ||||

Note. Error df = 419 and 418 due to list-wise deletion of missing data. AA = African American. EA = European American.

BD = Breast density. BC = breast cancer. PBC = perceived behavioral control.

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.10.

3.3. Mediators of between-race differences in responses to BD notifications

The data fit the variant model better than the invariant model (Δχ2(53) = 89.37, p < 0.01). The variant model exhibited good overall fit (χ2(232) = 396.74, p < 0 0.01; RMSEA = 0.06, 90% CI = 0.05 to 0.07; CFI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.05). Standardized direct effects are presented in Table 3 (see Supplementary Table 2 for full model results). Racial group membership had a significant direct effect on all mediating variables: Regardless of prior BD awareness, AA women reported more mistrust and discrimination, less BD and BC risk knowledge, and had lower SES. Whereas there were some direct effects of pre-existing factors on psychological responses (Fig. 2: shaded arrow b), there were no direct effects of racial group on the psychological responses (Fig. 2: shaded arrow a), suggesting that the between-race differences revealed in the previous MANOVA (i.e., Table 2) were attributable to the significant indirect effects discussed below.

Table 3:

Path analyses for psychological response outcomes - standardized estimates.

| Predictor |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | AA | Age | |

| 1. Negative Emotionality | ||||||||

| No | 0.06 | 0.23** | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.28** | −0.09 | −0.17** |

| Yes | −0.09 | 0.44** | −0.18 | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.10 | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| 2. BD Anxiety | ||||||||

| No | 0.12 | 0.19* | −0.19† | −0.10 | 0.00 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.13* |

| Yes | −0.13 | 0.20† | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.18 | 0.10 |

| 3. BC Worry | ||||||||

| No | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.10 | −0.17* |

| Yes | 0.02 | 0.19† | −0.32* | −0.16* | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| 4. Confusion | ||||||||

| No | 0.31** | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.20* | 0.21* | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.07 |

| Yes | 0.23† | 0.10 | −0.11 | −0.19* | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.16 | 0.02 |

| 5. Group-based medical mistrust | ||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.51** | 0.12† |

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.51** | 0.03 |

| 6. Personal discrimination | ||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.37** | 0.16** |

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.39** | 0.12† |

| 7. Group discrimination | ||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.58** | 0.09† |

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.73** | 0.11* |

| 8. BD knowledge | ||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.26** | −0.06 |

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.21** | 0.05 |

| 9. BC risk knowledge | ||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.35** | −0.07 |

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.36** | −0.06 |

| 10. SES | ||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.49** | −0.04 |

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.54** | 0.06 |

Notes. No = No prior BD knowledge, Yes = Prior BD Knowledge; SES = socio-economic status; AA = African American.

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.10.

Significant indirect effects are presented in Table 4. The mediation hypotheses received the most support among women without prior awareness of their BD. Generally, race-related perceptions, SES, and related knowledge transmitted the effects of racial group membership to psychological responses among women without prior awareness of their BD (Table 4: left column). There was also evidence that race-related perceptions transmitted the effects of racial group membership to psychological responses among women who were already aware they had dense breasts (Table 4: right column).

Table 4:

Significant Indirect Effects (Race → Pre-existing factors → Psychological Responses).

| Mediator | Standardized indirect effects | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome | No prior awareness | Prior awareness |

| Personal Discrimination | ||

| Negative psych Consequences | 0.08* | 0.17** |

| Breast density anxiety | 0.07* | − |

| Group Discrimination | ||

| Breast cancer worry | – | −0.23* |

| Group-based medical mistrust | ||

| Confusion | 0.16** | – |

| SES | ||

| Negative Psych Consequences | 0.14** | − |

| Breast density knowledge | ||

| Breast cancer worry | – | – |

| Confusion | 0.05* | – |

| Breast cancer risk knowledge | ||

| Confusion | −0.07* | – |

p < 0.01.

p < 0.05.

3.4. Predicting intentions

Before fitting the full model, correlations were used to examine the bivariate associations of intentions with the indicators for pre-existing factors, psychological responses, knowledge, and ANOVA for bivariate associations with the demographic predictors, separately by prior BD awareness. Group disparity (r = 0.15, p < 0.05), group-based discrimination (r = 0.19, p < 0.05), and the physical (r = 15, p < 0.05), social (r = 0.16, p < 0.05) and emotional (r = 0.15,p < 0.05) dimensions of emotionality were correlated with intentions among women with prior awareness of their BD. For women without prior awareness, confusion (r = 0.16, p < 0.05), BC worry (r = 0.16, p < 0.05), and BD knowledge (r = −0.16, p < 0.05) were correlated with intentions. ANOVAs indicated no associations between SES indicators and intentions.

Path analysis results indicated that the data was a better fit to the variant model than the invariant model (Δχ2(54) = 97.48, p < 0.001), and the variant model exhibited good overall fit (χ2(352) = 564.65, p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI = 0.04 to 0.06; CFI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.05; full model results and standardized direct effects appear in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4, respectively). With the exception of descriptive norms for those who knew their BD, the TPB variables significantly predicted intentions. In turn, for the psychological responses (Fig. 2: shaded arrow c), BC worry was associated with attitudes, anxiety, and confusion were associated with injunctive norms, and confusion was associated with descriptive norms. Among the preexisting factors (Fig. 2: shaded circle d), mistrust and discrimination were associated with attitudes and PBC, and BC risk knowledge and SES were also associated with PBC. These associations were generally more prevalent when women lacked prior awareness of their BD.

Significant indirect effects of race on the TPB predictors of intentions to talk to physicians were only present among women without prior awareness of their BD (Table 5). The effects of race on behavioral attitudes and PBC were mediated by race-related perceptions and SES (Fig. 2: product of paths from racial group to pre-existing factors [subscripts 1] and paths from pre-existing factors to TPB predictors [dark circle d]). AA women had greater medical mistrust, which attenuated behavioral attitudes and perceptions of control, and AA women perceived more group discrimination which led to more favorable attitudes and perceptions of control. AA women had lower SES, which led to weaker PBC. The serial mediations to intentions (Fig. 2: product of paths from racial group to pre-existing factors [subscripts 1], pre-existing factors to TPB predictors [dark circle d], and TPB predictors to intentions) indicated marginally significant indirect effects of race on intentions mediated by race-related perceptions and SES via attitudes and PBC (Table 5). There was no evidence that psychological responses to BD notifications mediated the relation between race and behavioral intentions.

Table 5:

Standardized Indirect Effects (Race → Pre-existing factors → Attitude and PBC).

| Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race to … | Attitude | Intentiona | PBC | Intentionb |

| Group-based medical mistrust to: | −0.11* | −0.03†† | −0.14** | −0.02†† |

| Group discrimination to: | 0.11* | 0.03†† | 0.11* | 0.02† |

| SES to: | – | – | −0.10* | −0.01† |

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05;

p = 0.05;

p < 0.10.

a = race to enduring factor to attitude to intention mediation.

b = race to enduring factor to PBC to intention mediation.

4. Discussion

The ongoing adoption of BD notification laws in the United States provides inarguable opportunities to inform women with dense breasts that they may be at increased BC risk. These laws have the potential to attenuate racial disparities in BD-related cognition and emotion, particularly if it motivates women to have pertinent discussions with their health care providers (Manning et al., 2016a). However, between-race differences in behavioral responses to the notifications may exacerbate racial disparities in BC, especially if AA women are less likely to discuss the notifications with physicians compared to EA women. When some of the important psychological predictors of behavior were examined in the current study, it was found that AA women had more favorable normative perceptions, attitudes, and intentions to discuss the notification with their health care providers. This finding contradicts the expectations derived from data showing inadequate mammography screening among AA women and its contribution to disparities in BC mortality (Curtis et al., 2008; Smith-Bindman et al., 2006). However, it is consistent with data showing that AA women report greater utilization of mammogram when controlling for important sociodemographic variables (Rakowski et al., 2009; Sassi et al., 2006). Thus, the screening disparity, and the contribution of screening disparity to BC mortality differences, may at least be partially due to socio-economic disadvantages faced by AA women. Indeed, in the BD notification context, results show that SES partially mediated the effect of race on behavioral intentions: AA women’s relative socio-economic disadvantages attenuated their behavioral intentions.

AA women had more extreme negative psychological responses to BD notifications when it came to BD-related emotionality and anxiety; however, there were no racial differences for BC worry or BD confusion. These findings are in line with prior research showing that AA women have greater BD anxiety compared to EA women (Manning et al., 2016a). The between-race differences in anxiety was partially attributed to personal discrimination and SES: AA women reported more discrimination, which led to more BD anxiety, and AA women had more socioeconomic disadvantage, which led to more BD anxiety. This study is the first to show that AA women’s heightened BD-related anxiety is partially due specifically to their relative socio-economic disadvantage and perceived discrimination. Despite AA women reporting more anxiety, the effects of anxiety were not transmitted to behavioral intentions via the proximal TPB variables (attitudes, norms and PBC). Future studies should examine whether other dimensions of anxiety, in contrast to BD-related anxiety, may influence behavioral intentions and actual behaviors.

Despite no significant between-race differences in confusion, the data showed that BD knowledge, GBMM, and BC risk knowledge mediated the relation between race and confusion when women did not have prior awareness of their BD. Ancillary analyses indicated that AA women were significantly more confused. However, the relation between race and confusion was fully mediated by prior BD awareness: AA women were less likely to be aware of their BD, and women who were unaware reported more confusion. This pattern explains why the study (a) failed to find a main effect of race on confusion (Hypothesis 1) when prior BD awareness was controlled for, and (b) found the hypothesized mediations only among women who were unaware of their BD.

The BD knowledge mediation is relatively straight-forward: AA women had lower BD knowledge, and this led to more BD-related confusion following the notification. For the GBMM mediation, AA women reported greater medical mistrust which was associated with more confusion. Prior research has shown that mistrust is associated with poorer physician-patient communication and misinformation regarding a number of cancer relevant topics (Matthews et al., 2002; Pedersen et al., 2012; White et al., 2016). The lack of trust in medical institutions may motivate some AA women to seek information elsewhere, the veracity of which may be questionable. For these women, new information about a personal health risk that may not correspond with existing (mis)information generates more confusion compared to women with greater medical trust, better physician communication, and more veritable health information. The BC risk knowledge mediation is less straight-forward: AA women had lower BC risk knowledge; however, BC risk knowledge was associated with greater confusion following the notification. In other words, when women had existing knowledge of BC risk factors, the assimilation of new BC risk information led to confusion. Some potentially conflicting information can be speculated to be presented in the notification itself. For example, the statement “Dense breast tissue is very common and is not abnormal” when juxtaposed with “dense breast tissue may increase your risk for breast cancer” – may confuse women who had a relatively good grasp of what contributes to BC risks prior to the notification.

For women who lacked prior awareness of their BD, the between-race differences in race-related perceptions and SES were ultimately translated to behavioral intentions via attitudes and PBC. Though it remains to be seen how much intentions predict actual behaviors in this context, these findings nonetheless offer potential intervention targets for facilitating BD and BC risk communication between AA patients and their physicians following receipt of BD notifications. Such communication is essential since AA women are less likely to have prior awareness of their BD due to a lack of physician communication (Manning et al., 2016a): the notifications provide an opportunity for such communication to take place. BD notifications themselves serve as an intervention to increase women’s knowledge about their own breast health; however, additional interventions may mitigate the detrimental influences of medical mistrust and SES for AA women’s decisionmaking. For example, an intervention based on fostering a sense of commonality between patients and physicians at a family medicine clinic increased both patients’ trust in their physicians and greater adherence to physician’s treatment recommendations (Penner et al., 2013).

Social policy interventions to address socioeconomic disadvantages (e.g., Earned Income Tax Credit; Conditional cash transfer programs, etc.) have yielded health benefits and reductions in health disparities (Williams et al., 2008; Williams and Purdie-Vaughns, 2015). However, no studies were identified that examined the psychological mechanisms that translated such interventions to behaviors that improved health among persons from disadvantaged groups. The implementation of health policies such as BD notification laws provides a valuable natural experiment to undertake such scientific investigations.

In contrast to the detrimental effects of medical mistrust and SES on behavioral intentions, perceptions of group discrimination yielded favorable behavioral intentions. AA women perceived that their racial group has been discriminated against, which prompted more positive attitudes, perceptions of control, and intentions to talk to their physicians about the notifications. These findings are consistent with data showing that AAs who perceive more racial discrimination are more active in conversations with their physicians (Hagiwara et al., 2013), which is presumably due to AAs’ motivations to avoid being the victims of prejudice in racially-discordant interactions (Shelton et al., 2005). These findings are also consistent with data showing that AA women scrutinize BD information more than their EA counterparts (Manning et al., 2016c). Altogether, these data suggest that AA women may harbor more suspicion about the BD notifications due to perceptions of group discrimination, which makes them want to talk to their physicians about it.

4.1. Limitations and future directions

This study examined anxiety that as specifically related to BD; however, it did not consider general anxiety or anxiety that might have been related to BC. It is plausible that these other dimensions of anxiety may have been affected by BD notifications, may have been different between AA and EA women, and may be uniquely related to behavioral intentions. Future studies may consider different dimensions of anxiety to more fully represent emotional responses to the BD notifications.

The ability to draw more definitive conclusions from the serial mediations linking racial group to behavioral intentions was hindered by the sample size; hence, despite being consistent with the theories, conclusions about indirect effects of race on the intention outcome should be regarded as tentative. Future studies may examine the indirect effects of race on behavioral intentions, as mediated by the processes investigated here, using larger samples of BD notification recipients. Future studies must also examine the extent to which there are between-race differences in women’s behaviors, and how the effects discerned in the current study are translated to women’s post-notification behaviors.

5. Conclusions

Following receipt of BD notifications in the state of MI, AA women had stronger intentions than EA women to discuss the notifications with their physicians. Despite racial differences in emotional responses to notification, those differences did not account for racial differences in intentions. Rather, race-based medical mistrust, perceptions of discrimination and socioeconomic status accounted for between-race differences in AA and EA women’s intentions to discuss the BD notifications with their physicians. It is important to examine whether AA women’s more favorable intentions translate to a greater probability of them following up on the notifications with their physicians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Strategic Research Initiative Grant from the Karmanos Cancer Institute, which is funded in part by P30CA022453.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.006.

References

- Ajzen I, 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, 2011. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 26, 1113–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, 2012. Martin Fishbein’s Legacy: the reasoned action approach. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 640, 11–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Albarracin D, Hornik R, 2007. Prediction and Change of Health Behavior: Applying the Reasoned Action Approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ US. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandraki I, Mooradian AD, 2010. Barriers related to mammography use for breast cancer screening among minority women. J. Of Natl. Med. Assoc. 102, 206–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Are You Dense Advocacy Inc, 2016. D.E.N.S.E.* State Efforts. WORX Branding & Advertising. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow WE, White E, Ballard-Barbash R, Vacek PM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Carney PA, et al. , 2006. Prospective breast cancer risk prediction model for women undergoing screening mammography. J. Of Natl. Cancer Inst. 98, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers RLM, van der Donck M, Klaver FM, van Minnen A, Massuger LFAG, 2002. Variables influencing anxiety of patients with abnormal cervical smears referred for colposcopy. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 23, 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosgraaf RP, de Jager WCC, Servaes P, Prins JB, Massuger LFAG, Bekkers RLM, 2013. Qualitative insights into the psychological stress before and during colposcopy: a focus group study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 34, 150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Yaffe MJ, Minkin S, 2011. Mammographic density and breast cancer risk: current understanding and future prospects. Breast Cancer Res. 13,223.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower V, 2013. Breast density legislation fueling controversy. J. Of Natl. Cancer Inst. 105, 510–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SE, Walker RL, Cutrona CE, Simons RL, Beach SRH, 2016. Anxiety mediates perceived discrimination and health in African-American women. Am. J. Health Behav. 40, 697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn J, De Luise T, Hurley S, Clover K, 1992. Development and validation of the PCQ: a questionnaire to measure the psychological consequences of screening mammography. Soc. Sci. Med. (1982) 34, 1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA, O’Sullivan P, 2001. Racial differences in breast cancer screening among women from 65 to 74 years of age: trends from 1987–1993 and barriers to screening. J. Of Women & Aging 13, 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, Sparks P, 1996. The theory of planned behaviour and health behaviours In: Conner M, Norman P (Eds.), Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. Open University Press, Maidenhead, BRK England, pp.121–162. [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Magai C, Krivoshekova YS, Ryzewicz L, Neugut AI, 2004. Fear, anxiety, worry, and breast cancer screening behavior: a critical review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. A Publ. Of Am. Assoc. For Cancer Res. 13, 501–510 Cosponsored By The American Society Of Preventive Oncology. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley LM, Ahn DK, Winkleby MA, 2008. Perceived medical discrimination and cancer screening behaviors of racial and ethnic minority adults. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. A Publ. Of Am. Assoc. For Cancer Res. 17, 1937–1944 Cosponsored By The American Society Of Preventive Oncology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis E, Quale C, Haggstrom D, Smith-Bindman R, 2008. Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: how much is explained by screening, tumor severity, biology, treatment, comorbidities, and demographics? Cancer 112, 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA, 2013. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. American College of Radiology, Reston, VA. [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding Sauer A, Kramer JL, Smith RA, Jemal A, 2016a. Breast cancer statistics, 2015: convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 66, 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Alcaraz KI, et al. , 2016b. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 66, 290–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destounis S, Arieno A, Morgan R, 2015. Initial experience with the new york state breast density inform law at a community-based breast center. J. Of Ultrasound Med. 34, 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Norton WE, Gaertner SL, Shelton JN, 2008. Disparities and distrust: the implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Soc. Sci. Med. 67, 478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facione NC, Facione PA, 2007. Perceived prejudice in healthcare and women’s health protective behavior. Nurs. Res. 56, 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JS, Kaplan CP, 2015. The divide between breast density notification laws and evidence-based guidelines for breast cancer screening: legislating practice. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 1439–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N, Penner LA, Gonzalez R, Eggly S, Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, et al. , 2013. Racial attitudes, physician-patient talk time ratio, and adherence in racially discordant medical interactions. Soc. Sci. Med. 87, 123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston DW, Bonetti D, Wareham NJ, Kinmonth AL, 2002. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour in behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Psychol. Health 17, 123–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hay JL, McCaul KD, Magnan RE, 2006. Does worry about breast cancer predict screening behaviors? A meta-analysis of the prospective evidence. Prev. Med. 42, 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, Gorin SS, 2005. Modeling pathways to affective barriers on colorectal cancer screening among Japanese Americans. J. Behav. Med. 28, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BA, Dailey A, Calvocoressi L, Reams K, Kasl SV, Lee C, et al. , 2005. Inadequate follow-up of abnormal screening mammograms: findings from the race differences in screening mammography process study (United States). Cancer Causes Control CCC 16, 809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Albrecht TL, Yilmaz-Saab Z, Shultz J, Purrington K, 2016. a. Influences of race and breast density on related cognitive and emotion outcomes before mandated breast density notification. Soc. Sci. Med. 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Duric N, Littrup P, Bey-Knight L, Penner L, Albrecht TL, 2013. Knowledge of breast density and awareness of related breast cancer risk. J. Cancer Educ. 7, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Purrington K, Duric N, Shultz J, Yilmaz-Saab Z, 2016b. Unique influences of medical mistrust and perceived discrimination on women’s responses to breast density notification. In: Annual Meeting of the Society for Behavioral Medicine, (Washington D.C). [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Purrington K, Penner L, Duric N, Albrecht TL, 2016c. Between-race differences in the effects of breast density information and information about new imaging technology on breast-health decision-making. Patient Educ. Couns. 99, 1002–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Sellergren SA, Manfredi C, Williams M, 2002. Factors influencing medical information seeking among African American cancer patients. J. Of Health Commun. 7, 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul KD, Schroeder DM, Reid PA, 1996. Breast cancer worry and screening: some prospective data. Health Psychol. 15, 430–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I, 2006. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 15, 1159–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin M, Barry H, Lennon A-M, Purcell H, Baum M, Keegan D, et al. , 2005. A survey of breast cancer awareness and knowledge in a Western population: lots of light but little illumination. Eur. J. Of Cancer (Oxford, Engl. 1990) 41, 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouzon DM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Chatters LM, 2017. Everyday racial discrimination, everyday non-racial discrimination, and physical health among African-Americans. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work Innovation Theory, Res. Pract. 26, 68–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SC, Leventhal KG, Scarles M, Evans CN, Makariou E, Pien E, et al. , 2014. Mammographic breast density as a risk factor for breast cancer: awareness in a recently screened clinical sample. Women’s Health Issues 24, e321–e326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehlert GW, 1992. A note on the Delta method. Am. Stat. 46, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L, 2009. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 135, 531–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen VH, Armes J, Ream E, 2012. Perceptions of prostate cancer in Black African and Black Caribbean men: a systematic review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology 21, 457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Dovidio JF, 2016. Racial color blindness and Black-White health care disparities In: Neville HA, Gallardo ME, Sue DW, Neville HA, Gallardo ME, Sue DW (Eds.), The Myth of Racial Color Blindness: Manifestations, Dynamics, and Impact. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, US, pp. 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Edmondson D, Dailey RK, Markova T, Albrecht TL, et al. , 2009. The experience of discrimination and black-white health disparities in medical care. J. Black Psychol. 35, 180–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Gaertner S, Dovidio JF, Hagiwara N, Porcerelli J, Markova T, et al. , 2013. A social psychological approach to improving the outcomes of racially discordant medical interactions. J. Of General Intern. Med. 28, 1143–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina E-GV, 2008. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J. Of Women’s Health (2002) 17, 923–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics, 2015. Qualtrics; (Provo, Utah, USA: ). [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2016. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W, Clark MA, Rogers ML, Weitzen S, 2009. Investigating reversals of association for utilization of recent mammography among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Black women. Cancer Causes Control CCC 20, 1483–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray KM, Price ER, Joe BN, 2015. Breast density legislation: mandatory disclosure to patients, alternative screening, billing, reimbursement. AJR. Am. J. Of Roentgenol. 204, 257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DJ, Radecki Breitkopf C, Ziegenfuss JY, Jenkins SM, Vachon CM, 2015. Awareness of breast density and its impact on breast cancer detection and risk. J. Of Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Of Am. Soc. Of Clin. Oncol. 33, 1143–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y, 2012. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y, 2015. The Lavaan Tutorial. (Belgium: ). [Google Scholar]

- Sassi F, Luft HS, Guadagnoli E, 2006. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in female breast cancer: screening rates and stage at diagnosis. Am. J. Of Public Health 96, 2165–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariff-Marco S, Klassen AC, Bowie JV, 2010. Racial/ethnic differences in self-reported racism and its association with cancer-related health behaviors. Am. J. Of Public Health 100, 364–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Richeson JA, Salvatore J, 2005. Expecting to Be the target of prejudice: implications for interethnic interactions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31, 1189–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu AL., 2016. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann. Of Intern. Med. 164, 279–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press, Washington, DC US. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, Abraham L, Barbash RB, Strzelczyk J, et al. , 2006. Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann. Of Intern. Med. 144, 541–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, 2013. The density conundrum: does legislation help or hurt? J. Of Am. Coll. Of Radiol. JACR 10, 909–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W, 2004. The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev. Med. 38, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh L, Ikeda DM, Miyake KK, Trinh J, Lee KK, Dave H, et al. , 2015. Patient awareness of breast density and interest in supplemental screening tests: comparison of an academic facility and a county hospital. J. Of Am. Coll. Of Radiol. JACR 12, 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigert J, Steenbergen S, 2012. The Connecticut experiment: the role of ultrasound in the screening of women with dense breasts. Breast J. 18, 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigert J, Steenbergen S, 2015. The Connecticut experiments second year: ultrasound in the screening of women with dense breasts. Breast J. 21, 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RO, Chakkalakal RJ, Presley CA, Bian A, Schildcrout JS, Wallston KA, et al. , 2016. Perceptions of provider communication among vulnerable patients with diabetes: influences of medical mistrust and health literacy. J. Of Health Commun. 21, 127–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA, 2008. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J. Of Public Health Manag.Pract. JPHMP 14 (Suppl. 1), S8–S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA, 2009. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 32, 20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Purdie-Vaughns V, 2015. Social and behavioral interventions to improve health and reduce disparities in health In: Quality A.f.H.R.a. (Ed.), Population Health: Behavioral and Social Science Insights. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Young RF, Severson RK, 2005. Breast cancer screening barriers and mammography completion in older minority women. Breast Cancer Res.Treat. 89, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.