Abstract

Scientific and lay theories propose that negative affect plays a causal role in problematic alcohol use. Despite this common belief, supporting experimental evidence has been mixed. Thus, the goals of this study were to a) meta-analytically quantify the degree to which experimentally manipulated negative affect influenced alcohol use and craving in the laboratory, b) examine whether the size of this effect depended on key manipulation characteristics (i.e., self-relevance of the stressor, timing of the end of the stressor, and strength of negative affect induction) or sample characteristics (i.e., substance use history). Across 41 studies (N = 2,403), we found small-to-medium effects for more use (dav = .31, 95% CI [.11, .50]) and craving (dav = .39, 95% CI [.04, .74]) following a negative affect manipulation than a control manipulation. We also found a significant increase in craving from pre- to post- affect induction (dav = .36, 95% CI [.14, .58]). This suggests the mixed results from the prior literature were likely due to statistically-underpowered studies. The moderator hypotheses received weak support, with few significant results in the predicted direction. Our meta-analysis provides clarity about a previously inconclusive set of results and highlights the need for more ecologically valid manipulations of affect in future work.

Keywords: Substance Use, Negative Affect, Alcohol, Meta-Analysis, AUD

Given the numerous short-term and long-term consequences of alcohol use and misuse, research identifying causal factors that can inform targets for intervention is warranted. Many sources of evidence suggest that negative affect plays a causal role in the development of problematic alcohol use (Baker et al., 2004; Hull, 1981; Volpicelli, 1987; Stasiewicz & Maisto, 1993). For example, meta-analytic results reveal a positive association between trait negative affect and alcohol use disorders (Kotov et al., 2010). Further research provides evidence that participants expect alcohol to reduce negative affect (e.g., Kassel, Jackson, & Unrod, 2000), and alcohol users who report drinking to cope with negative affect report greater alcohol use (Patrick, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Johnston, & Bachman, 2011). In addition, there is empirical evidence that negative affect plays an impedimentary role in relapse (e.g., Cooney et al., 1997), and empirically-supported treatments often focus interventions on disrupting the association between negative affect and alcohol use (e.g., Stasiewicz et a., 2013).

Despite this broad support, evidence from well-controlled laboratory studies that manipulate negative affect and then measure either alcohol use (e.g., amount of alcohol consumed in a sham taste test) or self-reported craving, is mixed. Some studies have found a significant effect of negative affect manipulations on alcohol and use and craving (e.g., Higgins & Marlatt, 1975; Tucker et al., 1980), whereas others have either found no significant effect or the opposite effect (e.g., Bacon, Cranford, & Blumenthal, 2015; Larsen et al., 2013). There are at least three possible ways to interpret mixed results. First, it could be there is no true effect, and significant results are false-positives. Second, it could be that these studies are statistically underpowered to detect the size of the true effect. Third, systematic methodological differences between studies increase or decrease the size of the effect, such that in some situations and/or for some people, negative affect may have a stronger effect on alcohol use and craving. A meta-analysis combining the effects across studies and testing key moderators informed by theory could help support or refute each of these interpretations. In particular, a meta-analysis of laboratory-based studies offers the opportunity for the strongest test of the effect of negative affect on alcohol use and craving, despite limitations of laboratory-based studies (e.g., limited ecological validity).

In terms of the potential moderators of effects, several contextual characteristics of stress or drinking situations have been proposed to influence whether negative affect will lead to alcohol use and craving. For instance, Hull’s (1981) self-awareness model predicts alcohol use should occur for stressors that induce negative self-evaluation. This is based on the assumption that alcohol has tension-reducing effects by decreasing the ability to encode information needed for self-awareness. Thus, this theory would predict that mixed results might be a function of some studies using stressors that increase negative self-evaluation (e.g., giving a speech about personal flaws) and other studies using stressors that are irrelevant to the self (e.g., viewing unpleasant, disgusting pictures). Although this theory was developed to understand alcohol use, it can be extended to alcohol craving, meaning that people should crave alcohol when negative self-evaluation is high (versus low).1

Another aspect of the drinking context that may be important is the timing of the stressor in relation to the opportunity to consume alcohol. Volpicelli’s (1987) review of animal and human research determined that alcohol use does not increase in anticipation of or during a stressor. The review indicated that it was only after a stressor that alcohol use increased. This theory would predict that the reason for mixed results in the prior literature is that some studies induced negative affect by having participants anticipate an upcoming stressor (e.g., a speech), whereas other studies measured alcohol use after the end of the stressor (e.g., a stressful imagery script).

Another important consideration may be the strength or potency of the manipulation; that is, its ability to elicit negative affect. Manipulations that elicit high levels of negative affect may be more likely to lead to alcohol use and craving than those that only increase negative affect slightly. Thus, the mixed results from the literature may partly be a function of the relative ability of existing manipulations to successfully increase negative affect. Somewhat in line with this, a meta-analysis of laboratory tobacco research found that studies that elicited more negative affect post-induction had larger effects on tobacco craving (Heckman et al., 2013). This question has not been examined in regard to alcohol use and may elucidate factors contributing to the inconsistency of findings in the alcohol literature.

In addition to contextual characteristics of the stressor, theories have identified individual differences that might explain for whom negative affect is more likely to lead to alcohol use. Theories have identified different motivations for substance use during different phases of the addiction process (Solomon, 1980; Koob, 2009). One set of theories predicts that heavier (e.g., dependent) users will have a stronger link between negative affect and substance use. This is proposed to be a function of the dissipation of the ‘high’ that occurs with repeated frequent use and, increase of unpleasant withdrawal symptoms when the substance is not in the system. Additionally, continued substance use enhances the connections between negative affective stress responses and drug withdrawal (Fox et al., 2005; Sinha et al., 2000), leading dependent users to be more likely to use during all periods of negative affect, and not just withdrawal-related negative affect. Another theory, based on the tobacco literature, suggests the opposite position (e.g., Shiffman et al., 2002). That is, negative affect should be less linked to use among heavy (versus social users). This is proposed to be a function of the fact that compared to other strong cues to use (e.g., morning coffee, end of work), negative affect is not as important of a cue for heavy users. Thus, mixed results highlight the need to examine important sample characteristics as a means to identify precursors to alcohol use and craving across different populations. It should be noted that a handful of other studies have looked at other individual differences such as family history of alcoholism and self-consciousness (Gord & Söderpalm, 2011; Hull & Young, 1983); however, there were too few studies to consider these factors in a meta-analysis.

Current Study

The overall goal of this study was to quantify the degree to which experimental manipulations of negative affect influence alcohol use and craving. We focused on studies involving laboratory inductions of negative affect, instead of naturalistic experiences of negative affect and substance use. This was done in order to conduct the strongest test of the theory, much like one conducts efficacy trials in treatment research before seeking to understand the effect in more real-world conditions. Given our interest in identifying factors that maintain substance use, we focused on use among current users, which included social/recreational users or people with current problems with alcohol use.

Our first goal was to estimate the effect size of manipulated negative affect on alcohol use and craving. Based on theory (e.g., Baker et al., 2004; Hull 1981) we predicted that the effect would be significantly different from zero. Based on similar meta-analyses looking at the effect of experimental affect manipulations on tobacco use and craving (Heckman et al., 2012, 2015), we predicted that negative affect manipulations would have small to medium size effects on alcohol use and craving. Our secondary goal was to clarify the mixed findings in the literature by testing key moderators derived from theories of negative affect and alcohol use. First, in line with Hull (1981), we predicted that the effect would be larger for negative affect manipulations considered self-relevant (e.g., speech about personal flaws) relative to self-irrelevant stressors (e.g., threat of shock). Second, consistent with Volpicelli (1987), we predicted that the effect of negative affect on drinking would be larger for studies that assessed use or craving after the stressor was over, compared to studies that measured use or craving during the anticipation of an upcoming stressor. Third, we looked at the relative strength of the induction, assuming that inductions that lead to a greater increase in negative affect would have larger effects. Finally, we examined whether the substance use history of the sample moderated effects. Based on contradictory theories (Baker et al., 2004; Shiffman et al., 2002), we did not have a specific prediction about substance use history as a moderator.

Method

Literature Search

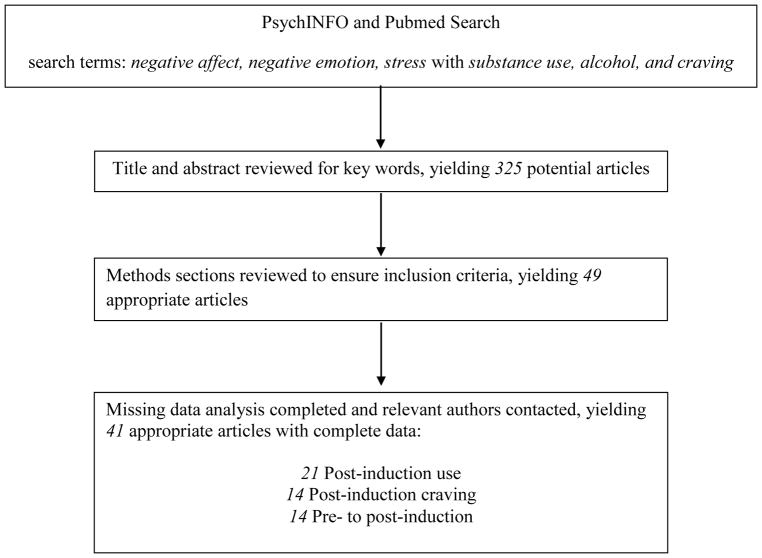

Figure 1 shows the diagram of our literature search. In order to identify relevant publications, we searched PsychINFO and Pubmed using combinations of the following search terms: negative affect, negative emotion, and stress with substance use, alcohol, and craving. During the search, the title and abstract were reviewed, and articles were excluded if they did not report data or did not manipulate negative affect (i.e., correlational studies). We also examined the reference list of key review articles in the area. Combining these searchers yielded 325 articles. At this stage, the method sections for articles were examined for the main inclusion criteria: a laboratory study that manipulated negative affect and then measured alcohol craving and/or use. This stage of the process left 49 articles. Of these, 9 did not include sufficient data needed to calculate effect sizes. In one case we were able to obtain the data from the corresponding authors. In all other cases, we either received no response or the necessary data were no longer available. We ultimately retained 41 studies with a total samples size of 2,403. Due to varying levels of missing data for certain analyses, the exact number of studies varies for any given effect size.

Figure 1.

Diagram of Study Search Strategy

Study Coding and Data Extraction

Data were extracted by two undergraduate students and the first two authors. All data were checked by a different coder and discrepancies were adjusted by consensus. To calculate effect sizes, we extracted the M and SD for craving and use. Our primary effect size compared alcohol use or craving in response to the negative affect induction relative to the neutral induction (hereafter referred to as post-induction use or craving). The majority of these studies were between-subject designs comparing participants exposed to different negative or neutral affect manipulations. There were some studies that exposed the same participants to different affect manipulations in separate sessions (e.g., Cooney, et al., 1997; Miller, Hersen, Eisler, & Hilsman, 1974). To facilitate comparisons across within- and between-subject effects, we use dav as our measure of effect size for within-subject effects (Cumming, 2012). This standardizes on the average of the two standard deviations (i.e., pre, post), making it more comparable to d from a between-subject design, relative to other methods that adjust for the correlation between repeated measures (e.g., drm). All effects were coded such that positive values indicated an greater use or craving in the negative affect condition. We interpreted effect sizes in line with Cohen’s (1992) recommendations (small: d =.2, medium: d =.5, and large: d =.8).

For a subset of craving studies that had the relevant data (k = 14), we also compared changes in craving pre-induction to post-induction in the negative affect condition only (hereafter referred to as pre-post induction craving). Whereas the post-induction effect captures situation-dependent alcohol craving and use following negative affect, the pre-post induction captures within-person change in craving due to negative affect.

To characterize the studies, we recorded the year of publication, total sample size, percentage of the sample who were women, racial and ethnic breakdown of the sample, mean age of the sample, and type of sample (undergraduate/community/mixed). We also coded several moderator variables. To test Hull’s theory, we rated the self-relevance of the negative affect induction of the study on a 1 (not at all self-relevant) to 4 (very self-relevant) scale. A priori, we determined exemplars of the different scale anchors: 1–standardized negative images (e.g., snakes); 2–Personalized imagery script about a stressful event; 3–a speech about a news article or non-self-topic; 4–a speech about personal flaws.2 To code the timing of the stressor in relation to use, we coded whether the affect induction involved anticipation of an upcoming stressor (e.g., a speech) or was in response to the termination of the stressor (e.g., following negative image exposure). To test whether the strength of the negative affect induction was related to the effect size (cf. Heckman et al., 2012), we coded the M and SD of self-reported negative affect before and after the induction for participants in the negative affect condition. We used this information in two ways. Similar to Heckman et al.’s (2013) tobacco meta-analysis, we used the raw scores for post-induction ratings only (not change from pre to post). We expanded on Heckman’s methods, however, by also calculating the size of the change in negative affect from pre-to post-induction. We tested addiction models that implicate negative affect in substance use at later stages of the addiction process (e.g., Koob, 2009) by coding whether the participants had an alcohol use disorder or not. For studies that had subsamples with and without alcohol use disorders, we calculated separate effect sizes for each subsample.

Data Analytic Plan

Given the broad array of methods used across studies, we expected heterogeneity in the effect sizes and therefore used a random effects model to calculate meta-analyzed effect size. Effect sizes were weighted by the inverse of the variance. For within-subject effects, we calculated the variance based on the formula provided by Dunlap, Cortina, Vaslow, & Burke’s (1996), which factors in the correlation between repeated measures. Given that the correlations between repeated measures of craving and/or use were generally not reported, we use .8, which is considered a conservative estimate (Rosenthal, 1991). Heterogeneity in the effect sizes across studies was tested with the Q-statistic, which tests the null of no heterogeneity of effect sizes across studies. We also report I2, which characterizes the total heterogeneity divided by the total variability. Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, and Altman (2003) recommend interpreting I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% as small, medium, and large amounts of heterogeneity respectively. All models were run using the Metafor package in R (Viechtbauer, 2010).

For our main effect size calculation, we calculated the overall effects of negative affect on post-induction alcohol use and both post-induction and pre-post induction craving. We then tested our moderating hypotheses with meta-regression. Each moderation hypothesis was tested by adding the moderator (e.g., self-awareness of the study manipulation) as a predictor of effect size. For categorical moderators (e.g., timing of the stressor), we followed up significant effects by examining the effect size for the different categories. For continuous moderators (e.g., self-awareness), we used estimated model-based effect sizes for different points on the scale.

To address publication bias, we used selection methods (Vevea & Hedges 1995; Vevea & Woods, 2005), which a recent simulation showed outperformed other strategies for detecting and correcting for publication bias (McShane, Bockenhold, & Hasen, 2016). Selection methods contain two components: a data model and a selection model. The data model defines results assuming no publication bias exists, whereas the selection model defines the selection process (e.g., only significant results get published; significant results are more likely to be published). Together, these two models allow for a sensitivity analysis to see how the meta-analyzed effect might change under different selection structures.

We fit three different selection models using the weightfunct in R (Coburn & Vevea, 2016). The first estimated parameters for the selection function (Vevea & Hedges, 1995). We specified the selection function to only include significant results in the same direction. An advantage of this approach is that it allows for the estimation of standard errors and confidence intervals. This model provides a likelihood test, which tests whether the model with the selection parameter is a better fit than one without the selection parameter. Significant results are a sign of publication bias. A disadvantage of this approach is that it generally requires large samples (k > 100). The second and third models were based on Vevea and Woods (2005), who proposed a model where the selection parameters are fixed, obviating the need for large samples, but not allowing for the estimation of standard errors and confidence intervals. We used predefined weights that signify moderate and severe bias selection models (see Vevea & Woods for weights). Together the three different models provided a robustness test for our overall effects.

Results

Study Characteristics

The average sample size was 50.06 (see Table 1 for aggregated data and Table 2 for individual studies). Using a between-subject design (assuming an equal number of participants per group), individual studies on average had .10 power to detect small effects (d = .20), .41 power to detect medium effects (d = .50) and .79 power to detect large effects (d = .80). In a within-subject design, this would give .28, .93, and, .99 power to detect small, medium, and large effects. Thus, the studies were individually underpowered for small effects in both within- and between-subject designs and underpowered for medium effects for between-subject designs.

Table 1.

Aggregate Study Characteristics

| k | M | SD | Min-Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication Year | 41 | 2000 | 14.36 | 1973–2016 |

| N | 41 | 50.06 | 32.81 | 8–146 |

| Mean age | 31 | 32.11 | 9.59 | 19.3–49.5 |

| % Women | 40 | 36.56 | 28.46 | 0–100 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| % Caucasian/White | 22 | 74.04 | 17.95 | 22–95 |

| % African American/Black | 16 | 18.40 | 16.80 | 1–65 |

| % Asian/Asian American | 5 | 5.68 | 6.35 | 1–17 |

| % Hispanic/Latinx | 9 | 7.21 | 6.99 | 1–21.4 |

| % Native American | 2 | 3.2 | 2.54 | 1.4–5 |

| % Mixed/Bi-racial | 1 | 2.4 | -- | -- |

| % Other | 7 | 4.22 | 5.31 | 0–16 |

Note. k = number of studies reporting the information.

Table 2.

Study Level Characteristics

| Author (Year) | N | Sample Type | Affect Induction | Outcome | Alcohol use Disorder | Other Disorder(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Abrams et al (2002) | 45 | Community | Short Dialogues With other Participants | Use | None | Social Anxiety Disorder |

| 2. Bacon & Thomas (2013) | 40 | Community | Trier Social Stress Test | Use | Alcohol Dependence | Social Anxiety Disorder |

| 3. Bacon et al. (2015) | 40 | Undergraduate | Cyberball Social Exclusion | Use | None | None |

| 4. Birch et al. (2004) | 86 | Undergraduate | 10 minutes of Music | Craving | None | None |

| 5. Brady et al. (2006)* | 35 | Community | Cold-pressor | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 5. Brady et al. (2006)* | 28 | Community | Cold-pressor | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | PTSD |

| 6. Caselli et al. (2013)* | 29 | Community | Rumination | Craving | None | None |

| 6. Caselli et al. (2013)* | 26 | Community | Rumination | Craving | None | None |

| 6. Caselli et al. (2013)* | 26 | Community–Treatment Seeking | Rumination | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 7. Coffey et al., (2006) | 12 | Community–Treatment Seeking | Trauma Imagery Script | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | PTSD |

| 8. Cooney et al. (1997) | 50 | In Patient | Personalized Imagery Script | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 9. Corcoran & Parker (1991) | 69 | Undergraduate | Preparation for A Speech about Body Flaws | Use | None | None |

| 10. de Wit et al. (2003) | 37 | Community | Trier Social Stress Test | Use | None | None |

| 11. Fox et al. (2013) | 26 | Community | Personalized Imagery Script | Craving | None | None |

| 12. Higgins & Marlatt (1973) * | 20 | Community | Anticipation of Painful Shocks | Use | None | None |

| 13. Higgins & Marlatt (1973) * | 20 | Community | Anticipation of Painful Shocks | Use | “Alcoholics” | None |

| 14. Higgins & Marlatt (1975) | 64 | Undergraduate | Anticipation of Evaluation | Use | None | None |

| 15. Higley et al. (2011) | 28 | Community | Stressful Imagery Script | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 16. Hull & Young (1983) | 120 | Community | Failure Feedback | Use | None | None |

| 17. Jansma et al. (2000) | 40 | Inpatient Addiction Center | Average of Failure and Sad Music | Use | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 18. Kidorf & Lang (1999) | 84 | Undergraduate | Preparation for A Speech about Body Flaws | Use | None | None |

| 19. Larsen et al. (2013) | 106 | Undergraduate | Trier Social Stress Test | Use | None | None |

| 20. Marlatt et al (1975) | 20 | Undergraduate | Insulting Confederate | Use | None | None |

| 21. Mason et al. (2008) | 47 | Community | Unpleasant IAPS Images | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 22. McGrath et al. (2016) | 100 | Mix | Preparing for Speech About Physical Appearance | Use | None | None |

| 23. McNair (1996) | 60 | Undergraduate | Preparing for Speech About Physical Apparence | Use | None | None |

| 24. Miller et al. (1974)* | 8 | Community | Role Play Requiring Assertiveness | Use | None | None |

| 24. Miller et al. (1974)* | 8 | Community | Role Play Requiring Assertiveness | Use | Alcohol Abuse or Dependence | None |

| 25. Noel & Lisman (1980)* | 38 | Undergraduate | Unsolvable Anagrams | Use | None | None |

| 25. Noel & Lisman (1980)* | 48 | Undergraduate | Unsolvable Anagrams | Use | None | None |

| 26. Nosen et al. (2012) | 108 | Community–Treatment Seeking | Trauma Imagery Script | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | PTSD |

| 27. Phil et al. (1994) | 27 | Community | Electric Shock | Use | None | None |

| 28. Phil & Yankofsky (1979) | 40 | Undergraduate | Intelligence Feedback | Use | None | None |

| 29. Ralevski et al. (2016) | 25 | Community–Treatment Seeking | Trauma Imagery Script | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | PTSD |

| 30. Ray (2011) | 64 | Community | Stressful Imagery Script | Craving | None | None |

| 31. Rubonnis (1994) | 57 | Inpatient | Personalized Imagery Script | Craving | Alcohol Abuse or Dependence | None |

| 32. Sinha et al (2009)* | 28 | Community–Treatment Seeking | Personalized Imagery Script | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 32. Sinha et al (2009)* | 28 | Community | Personalized Imagery Script | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 33. Steinberg et al. (2011)* | 24 | Community | Uncontrollable Noise | Craving | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 33. Steinberg et al. (2011)* | 28 | Community | Uncontrollable Noise | Craving | None | None |

| 34. Thomas (2010) | 129 | Undergraduate | Worry | Craving | None | None |

| 35. Thomas et al. (2011) | 79 | Community | Trier Social Stress Test | Use | Alcohol Dependence | None |

| 36. Thomas et al. (2014) | 82 | Community | Trier Social Stress Test | Use | None | None |

| 37. Tucker et al. (1980) | 40 | Undergraduate | Intellectual Performance Stress | Use | None | None |

| 38. Vinci et a. (2014) | 39 | Undergraduate | Unpleasant IAPS Images and Music | Craving | None | None |

| 39. Wardell et al. (2012) | 146 | Undergraduate | Unpleasant IAPS Images and Music | Use | None | None |

| 40. Wolfe & Maisto (2000) | 60 | Undergraduate | Increased Salience of Self-discrepancy | Use | None | None |

| 41. Zack et al. (2006) | 69 | Undergraduate | Read & Create Synonyms for Negative Words | Use | None | None |

Note.

Multiple Samples From the Same Paper With the Same Author and Year; PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; Treatment Seeking = Currently in Treatment for Alcohol Use; IAPS = International Affective Picture System.

The demographics of the studies roughly followed the general population in the United States (United States Census Bureau, 2017). Participants were generally White and in their early-to-mid 30’s (in 2012, the median age was 37). Studies tended to include more men than women and in relation to census data, had an underrepresentation of Hispanic/Latinx (17.6 versus 7.21). Perhaps more striking is the fact that only 51% of studies reported race/ethnicity and many studies only reported the percentage of Caucasians. The majority of the studies (63%) recruited from the community as a whole, with a minority (27%) using exclusively undergraduates. Three studies explicitly reported a mix of undergraduates and community members. See Table 1 for summary statistics and Table 2 for individual study data.

Overall Effects

In terms of alcohol use following a negative affect induction, there was a significant post-induction effect that was small-to-medium in size, (dav = .31, 95% CI [.11, .50], k = 21), with a large amount of heterogeneity (I2 = 71.54, p < .001). The effect was in the expected direction, indicating that the negative affect conditions produced more alcohol consumption than the control conditions. The post-induction effect was significant for craving and in the same direction and of similar magnitude (dav = .39, 95% CI [.04, .74], k = 14). There was significant heterogeneity in the effect (I2 > 80). Similar effects were found when looking at changes in craving from pre- to post-induction in the negative affect condition (dav = .36, 95% CI [.14, .58], k = 14), again with significant heterogeneity (p’s < .001) that was large in size (I2 > 80). Taken together, these results are consistent with our predictions and suggest that the effects of negative affect inductions on alcohol use and craving fall between small to medium in size. The large amount of heterogeneity across studies warranted further investigation of moderators.

Moderators

Self-relevance

The self-relevance of the stressor was not significantly related to post-induction use (b = .01, 95% [−.18, .20], p = .929, k = 21) or post-induction craving (b = .26, 95% [−.17, .71], p = .241, k = 14). In support of hypotheses, however, self-relevance was related to larger pre-to-post induction increases in alcohol craving, (b = .175, 95% [.005, .345], p = .043, k = 14). To understand this effect, we estimated, based on the model, the effect size at low self-relevance (i.e., rating of 1 on 4-point scale) and high self-relevance of the manipulation (i.e., rating of 4). For inductions with low self-relevance, the effect was not significant, (dav = .06, 95% CI [−.28, .41]), whereas inductions high in self-relevance had a significant and large effect (dav = .59, 95% CI [.29, .89]).

Timing

Although not statistically significant (b = .26, 95% [−.21, .74], p = .286, k = 21), studies that used anticipation as the negative affect induction had smaller post-induction use effect sizes (dav = .11, 95% CI [−.31, .53], k = 5) compared to studies that allowed for alcohol use after the stressor was over (dav = .37, 95% CI [.14, .60], k = 16). Moreover, the confidence interval for studies that measured alcohol use during the anticipation phase contained zero, whereas the other studies did not. These results provide weak evidence that alcohol use increases after a stressful event has ended but not during anticipation (Volpicelli, 1987).

Strength of negative affect manipulation

Next, we examined whether the strength of the negative affect manipulation influenced the size of effects. Contrary to predictions, neither self-reported negative affect post-induction nor increase in negative affect from pre-to-post induction was related to effect size for post-induction alcohol use or craving (see Table 3). This may be due, in part, to the fact that so few studies reported enough information about the negative affective experiences of participants in response to the induction to be included in these analyses. We did find one significant effect, such that post-induction negative affect, but not changes in negative affect pre to post induction, was associated with larger pre to post changes in craving (b = .02, 95% CI [.01, .05]).

Table 3.

Results of Moderator Analyses for Negative Affect Inductions on Alcohol Use and Craving

| k | b | 95% CI | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-relevance | ||||

| Post-induction Use | 21 | .01 | [−.18, .20] | 0 |

| Post-induction Craving | 14 | .26 | [−.17, .71] | 3.08 |

| Pre-Post Induction Craving | 14 | .18 | [.01, .34] | 24.26 |

| Timing | ||||

| Post-induction Use | 21 | .26 | [−.21, .74] | 0 |

| Post-induction Negative Affect | ||||

| Post-induction Use | 7 | −.001 | [−.02, .02] | 0 |

| Post-induction Craving | 8 | .02 | [−.02, .06] | 0 |

| Pre-Post Induction Craving | 8 | .03 | [.01, .05] | 65.24 |

| Negative Affect Change | ||||

| Post-induction Use | 8 | −.05 | [−.28, .17] | 0 |

| Post-induction Craving | 8 | −.08 | [−.45, .30] | 0 |

| Pre-Post Induction Craving | 9 | .07 | [−.15, .29] | 0 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | ||||

| Post-induction Use | 21 | −.22 | [−.78, .34] | 0 |

| Post-induction Craving | 14 | .51 | [−.21, 1.23] | 2.74 |

| Pre-Post Induction Craving | 14 | .27 | [−.17, .71] | 2.53 |

Note. k = the number of samples included in the analysis; Self-relevance = self-relevance of the stressor/negative affect induction of the study; R2 = amount of heterogeneity accounted for.

As a supplement, we examined whether, on average, the manipulations used in these studies actually increased negative affect substantially. Thus, we calculated the meta-analyzed effect size for the increase in negative from pre to post in the negative affect condition. Across the 22 studies that had enough data, the effect of the induction on increases in negative affect across participants was significant and large in size (dav = 1.13, 95% CI [.73, 1.53], k = 21), with a high amount of heterogeneity, I2 = 96.75. These results show that, in general, the manipulations were successful in increasing negative affect.

Substance use history

Alcohol use disorder status was not significantly related to any of the effect sizes (see Table 3).

Publication Bias

Table 4 displays the results for the publication bias analysis. Following Vevea and Woods (2005), we interpreted the results from these analyses by looking at instability in the effect size across the different models. Large reductions when incorporating more severe selection bias models are indicative of publication bias. We made two comparisons to determine whether a reduction was large: a) the percentage change for the adjusted effect in relation to the original effect and b) the adjusted effect sizes to the 95% CI for the unadjusted effect.

Table 4.

The Effect Size and Standard Error From Publication Bias Analyses

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-induction Use | .30 (.114) | .56 | .26 | .21 |

| Post-induction Craving | .39 (.179) | .26 | .24 | .18 |

| Pre-Post Induction Craving | .36 (.112) | .57 | .33 | .26 |

Note. 1 = unadjusted; 2 = Vevea & Hedges (1995); 3 = Vevea & Woods (2004) Moderate

Selection Bias; 4 = Vevea & Woods Severe Selection Bias.

The percentage decrease was generally small (M = 23%; min = 10%, max = 40%). In two cases, the adjusted model had a larger effect size than the unadjusted, which suggests the opposite of publication bias. These results are likely explained by the fact that the Vevea and Hedges (1995) model assumes studies are mostly reporting significant results in the same direction, whereas we have identified and included nonsignificant results in our analyses. Aside from the two cases of effect size increase, all adjusted estimates were within the confidence intervals of the unadjusted effect. This suggests that there is little evidence of publication bias, which is not surprising given that there have been published results with null findings.

Discussion

The goal of this meta-analysis was to quantify the degree to which experimentally manipulated negative affect influences alcohol use and craving in the laboratory. We found small-to-medium effects, such that after a negative affect manipulation, participants were more likely to consume and crave alcohol than after a control manipulation. It is therefore likely that the mixed results from the prior literature were due to statistically underpowered studies. Our secondary goal was to examine whether the size of this effect depended on key manipulation characteristics (e.g., self-relevance and strength of negative affect induction) or sample characteristics (e.g., alcohol use disorder status). The moderator analyses generally failed to support our hypotheses, except for some consistent effects of self-relevance on craving effect sizes, despite significant heterogeneity of the effect sizes across studies.

Effect of Negative Affect Inductions on Substance Use and Craving

The overall finding that negative affect increases alcohol use and craving supports theories implicating negative affect as a maintenance factor of alcohol use (e.g., Baker et al., 2004; Koob, 2009; Stasiewicz & Maito, 1993). The effect sizes were similar when comparing post-induction between negative affect and neutral/control conditions (between-group) and pre-post change in craving in the negative affect condition (within-individuals), suggesting that this effect occurs both between situations and within people. The results were also similar across craving and alcohol use. This may be unsurprising, as many theories suggest that substance craving and substance use are strongly causally linked (e.g., Baker et al., 2004); however, other theories suggest that craving only occurs when substance use is blocked (Gass et al., 2014; Tiffany, 1990), which may imply different associations.

There are two ways to interpret the size of the effect. One the one hand, the effect size may be smaller than expected. Lay theories in particular, and psychological theories to a lesser extent (e.g., Baker et al., 2004), place a heavy emphasis on the association between negative affect and alcohol use, and this is reflected in the focus on negative affect and stress in various empirically supported treatments for substance use disorders. Thus, under the highly controlled laboratory conditions, it may be expected that the effect would be medium-to-large (e.g., d = .60 −.80). On the other hand, the size of the effect may be as expected or even larger than expected. The stressors used in the laboratory tend to be artificial and quite different (e.g., less complex, shorter duration) from the types of situations that elicit negative affect outside of the lab. Moreover, many aspects of laboratory alcohol studies reduce the likelihood that participants will consume alcohol (e.g., time of day, observer reactance), which would reduce to ability to find an effect. Thus, the fact that these laboratory studies detected effects of small to medium size can be interpreted as a support for theories that implicate negative affect in alcohol use.

Research using ecological momentary assessment, which measures affect and alcohol use across time in participants’ natural environments, may help reconcile these interpretations.; however, somewhat similar to the laboratory studies, ecological momentary assessment studies have found mixed associations between prior negative affect and later alcohol use, with most studies finding null results (e.g., Dvorak et al., 2016; Treloar et al., 2015). These findings highlight that there are multiple factors that influence alcohol use; despite this, the meta-analysis detected a significant and arguably meaningful effect.

Moderator Analyses

We focused on several factors gleaned from prior theory to explain heterogeneity of the effect size across studies. First, we found that affect manipulations rated higher (versus lower) in self-relevance had a relatively stronger effect on within-person changes in craving. Although Hull’s model (1981) was initially conceived for alcohol use and not craving, it makes logical sense that if, as the theory proposes, alcohol is reinforcing by reducing self-awareness, cravings to drink could be stronger in situations that increase their self-awareness. Our results show that this, in fact, occurs and provides a useful extension of Hull’s model beyond alcohol consumption. It is unclear why the self-relevance of the stressor was not related to the effect size for alcohol use, although actual consumption may be a higher-threshold behavior that many participants avoid engaging in the lab (relative to endorsing craving). It is also possible that individual-level moderators influence the extent to which stressors that are more (versus less) self-relevant lead to drinking. In particular, prior research has found that self-relevant stressors lead to drinking among people high in trait self-consciousness (Hull & Young, 1983; Hull, Young, & Jouriles, 1986). Well-designed, well-powered studies in this area are needed to better understand the mechanisms by which self-relevance influences the association between negative affect and alcohol use.

Second, we found weak evidence for the moderating effect of anticipation vs. completion of the stressor prior to assessing drinking. That is, the effect size of negative affect on alcohol use was only significantly different from zero when stressors were completed prior to assessing alcohol use (but not when alcohol use was assessed during anticipation of a stressor). These results are somewhat in line with Volpicelli (1987), who reviewed animal studies showing increased alcohol consumption only after stressors had completed. The small number of studies using anticipation as a negative induction makes these results difficult to interpret. This fact highlights the need for further research.

Third, we sought to examine whether more powerful inductions of negative affect would have a stronger effect on craving and substance use. We found that mean post-induction negative affective responses were associated with a larger increase in within-subject craving; however, we did not find any other evidence in support of our hypothesis. This is somewhat surprising given that there was significant heterogeneity in the intensity of the affect manipulations and the effect size. The fact that few studies reported enough information to be included may have affected the ability to detect an effect. This suggests that future studies in the area should adequately report the effects of their manipulation on negative affective responses of the participants (e.g., M’s, SD’s tests statistics) to allow future researchers to more effectively evaluate the internal validity of the manipulations.

Finally, we did not find any evidence that the effect of negative affect was stronger or weaker for people with an alcohol use disorder vs. those who did not have a disorder. This likely suggests that the association between negative affect and substance use may not differ as a function of alcohol dependence. Rather, individuals who are dependent may be more likely to experience negative affect, which, in combination with other vulnerability factors (e.g., reduced self-control), may lead to more frequent use. This fits with prior research showing the individuals with alcohol use disorders are higher (versus lower) in trait negative affect (e.g., Kotov et al., 2010).

Recommendations for Future Studies

Based on these results, we make three recommendations for future studies in this area. First, given that the average size of the effect was small to medium, between-subject manipulations of negative affect should include a sample size of at least 260 to ensure power of 0.80, and within-subject designs should have at least 67 participants to adequately power their studies. Failing to do so increases the risk of continued mixed results in the literature and potential for both false-positive and false-negative results. Second, even when we included moderators in our analyses, there was a high amount of heterogeneity of effect size. This suggests that more standardization may be necessary in negative affect-alcohol use studies. Collaboration among multiple labs and using integrative data analysis (i.e., analysis of multiple data sets as one) may help identify sources of heterogeneity and therefore inform effective strategies for reducing their influence. Third, to properly estimate the effect of negative affect on drinking behavior in the real world, future studies, even in the laboratory, can seek to increase the ecological validity of the settings (e.g., bar lab) and the manipulations used (e.g., provocation by another person). Finally, most of the theories in this area have neglected to examine cultural and social identity factors, which may explain heterogeneity across studies. Previous research has identified different rates of substance use by gender (e.g., Wilsnack et al., 2009), racial and ethnic group (e.g., African Americans; Zapolski, Pederson, McCarthy, & Smith, 2013) and sexual minority status (e.g., McCabe et al., 2009), which may imply different contextual maintenance factors.

Limitations

Several limitations should be taken into account when considering our results. Although laboratory studies on the link between negative affect and substance use have been conducted for decades, we still had a fairly modest sample size of studies. More large-scale studies are needed to build further confidence in our results. Nonetheless, our meta-analysis provides initial clarity about a set of difficult-to-interpret mixed results and provides several avenues for future research, including providing guidelines for sample size. Second, our analyses, like those of prior studies, examine negative affect in general. Negative affect, however, is made up of several distinct feeling states (e.g., anger, fear, anxiety), which may have unique associations with alcohol use and craving. The majority of the negative affect inductions used in the reviewed studies likely targeted several emotions, making it difficult for us to capture that nuance in our moderator analyses. Future studies may wish to test the effects of certain negative affect states against others (e.g., anxiety vs anger).

A key limitation highlighted by the current meta-analysis is the lack of tests of ecological validity in the analyzed studies. Although our results show it is possible for negative affect to increase substance use and craving, they do not establish that this occurs outside of the laboratory. More ecologically-valid studies are needed to triangulate these findings. It is important to note, however, that existing ecological momentary assessment studies uncover results that are consistent with those of this meta-analysis (with small to medium effect sizes; Treloar et al., 2015). One compromise in balancing internal and external validity concerns would be to manipulate the presence of negative affect cues in the context of ecological momentary assessment studies, similar to drug cue reactivity studies in naturalistic environments (i.e., cue reactivity with ecological momentary assessment; Wray, Godleski, & Tiffany, 2011). Importantly, incorporating knowledge obtained from contemporary aversive learning theories and research (e.g., conditioned inhibition; serial conditioning; Laude & Fillmore, 2015) can lead to the development of studies and manipulations that take into account the complexities of human stressors and the effects of combined stimuli as they occur in the real world. Despite these limitations, this meta-analysis consolidates and provides some clarity to laboratory studies looking at the effect of negative affect on alcohol use and craving.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work came from National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant F31 DA038417 awarded to Konrad Bresin.

Footnotes

In some of the research that followed the model’s proposal, Hull and colleagues (Hull & Young, 1983; Hull, Young, & Jouriles, 1986) identified trait self-consciousness as an important moderator, with stronger effects of self-evaluation on drinking among people high in trait self-consciousness. We return to this point in the discussion.

The Trier Social Stress Test was a commonly-used stressor across studies. It was coded as a “3” or “4” depending on the topic of the speech. When the topic was a non-personal topic (e.g., controversial issue) it was coded as 3, when it was a personal topic (e.g., personal qualifications) it was coded as a 4.

Contributor Information

Konrad Bresin, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign.

Yara Mekawi, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign.

Edelyn Verona, University of South Florida.

References

* = study included in the meta-analysis.

- *.Bacon AK, Cranford AN, Blumenthal H. Effects of ostracism and sex on alcohol consumption in a clinical laboratory setting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29:664–672. doi: 10.1037/adb0000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bacon AK, Thomas SE. Stress reactivity, social anxiety, and alcohol consumption in people with alcoholism: A laboratory study. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2013;9:107–114. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2013.778775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Birch CD, Stewart SH, Wall A, McKee SA, Eisnor SJ, Theakston JA. Mood-induced increases in alcohol expectancy strength in internally motivated drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:231–238. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brady KT, Back SE, Waldrop AE, McRae AL, Anton RF, Upadhyaya HP, … Randall PK. Cold pressor task reactivity: Predictors of alcohol use among alcohol-dependent individuals with and without comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:938–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Caselli G, Gemelli A, Querci S, Lugli AM, Canfora F, Annovi C, … Watkins ER. The effect of rumination on craving across the continuum of drinking behaviour. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2879–2883. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn KM, Vevea JL. Weightr: Estimating weight-function models for publication bias in r. R pack-age version 1.0.0. 2016 Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=weightr.

- *.Coffey SF, Stasiewicz PR, Hughes PM, Brimo ML. Trauma-focused imaginal exposure for individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence: Revealing mechanisms of alcohol craving in a cue reactivity paradigm. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:425–435. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Cooney NL, Litt MD, Morse PA, Bauer LO, Gaupp L. Alcohol cue reactivity, negative-mood reactivity, and relapse in treated alcoholic men. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:243–250. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Corcoran KJ, Parker PS. Alcohol expectancy questionnaire tension reduction scale as a predictor of alcohol consumption in a stressful situation. Addictive Behaviors. 1991;16:129–137. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G. Understanding the new statistics: Effect sizes, confidence intervals, and meta-analysis. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- *.de Wit H, Söderpalm AHV, Nikolayev L, Young E. Effects of acute social stress on alcohol consumption in healthy subjects. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1270–1277. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000081617.37539.D6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Drobes DJ. Cue reactivity in alcohol and tobacco dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:1928–1929. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000040983.23182.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap WP, Cortina JM, Vaslow JB, Burke MJ. Meta-analysis of experiments with matched groups or repeated measures designs. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Pearson MR, Sargent EM, Stevenson BL, Mfon AM. Daily associations between emotional functioning and alcohol involvement: Moderating effects of response inhibition and gender. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;163:S46–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn CE, Sayette MA. A social-attributional analysis of alcohol response. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1361–382. doi: 10.1037/a0037563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Talih M, Malison R, Anderson GM, Kreek MJ, Sinha R. Frequency of recent cocaine and alcohol use affects drug craving and associated responses to stress and drug-related cues. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:880–891. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Fox HC, Sofuoglu M, Morgan PT, Tuit KL, Sinha R. The effects of exogenous progesterone on drug craving and stress arousal in cocaine dependence: Impact of gender and cue type. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1532–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JC, Motschman CA, Tiffany ST. The relationship between craving and tobacco use behavior in laboratory studies: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:1162–1176. doi: 10.1037/a0036879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman BW, Carpenter MJ, Correa JB, Wray JM, Saladin ME, Froeliger B, … Brandon TH. Effects of experimental negative affect manipulations on ad libitum smoking: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2015;110:751–760. doi: 10.1111/add.12866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman BW, Kovacs MA, Marquinez NS, Meltzer LR, Tsambarlis ME, Drobes DJ, Brandon TH. Influence of affective manipulations on cigarette craving: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2013;108:2068–2078. doi: 10.1111/add.12284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Higgins RL, Marlatt GA. Effects of anxiety arousal on the consumption of alcohol by alcoholics and social drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1973;41:426–433. doi: 10.1037/h0035366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Higgins RL, Marlatt GA. Fear of interpersonal evaluation as a determinant of alcohol consumption in male social drinkers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1975;84:644–651. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.84.6.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Higley AE, Crane NA, Spadoni AD, Quello SB, Goodell V, Mason BJ. Craving in response to stress induction in a human laboratory paradigm predicts treatment outcome in alcohol-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2355-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hull JG, Young RD. Self-consciousness, self-esteem, and success–failure as determinants of alcohol consumption in male social drinkers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:1097–1109. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.44.6.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull JG. A self-awareness model of the causes and effects of alcohol consumption. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90:586–600. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Jansma A, Breteler MHM, Schippers GM, De Jong Cor AJ, Van DS. No effect of negative mood on the alcohol cue reactivity on in-patient alcoholics. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:619–624. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kidorf M, Lang AR. Effects of social anxiety and alcohol expectancies on stress-induced drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Neurobiological substrates for the dark side of compulsivity in addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, Watson D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:768–821. doi: 10.1037/a0020327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Larsen H, Engels RCME, Granic I, Huizink AC. Does stress increase imitation of drinking behavior? an experimental study in a (semi-)naturalistic context. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:477–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laude JR, Fillmore MT. Alcohol cues impair learning inhibitory signals in beer drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:880–886. doi: 10.1111/acer.12690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Marlatt GA, Kosturn CF, Lang AR. Provocation to anger and opportunity for retaliation as determinants of alcohol consumption in social drinkers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1975;84:652–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mason BJ, Light JM, Escher T, Drobes DJ. Effect of positive and negative affective stimuli and beverage cues on measures of craving in non treatment-seeking alcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McNair LD. Alcohol use and stress in women: The role of prior vs. anticipated stressors. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1996;18:331–345. [Google Scholar]

- McShane BB, Böckenholt U, Hansen KT. Adjusting for publication bias in meta- analysis: An evaluation of selection methods and some cautionary notes. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2016;11:730–749. doi: 10.1177/1745691616662243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Miller PM, Hersen M, Eisler RM, Hilsman G. Effects of social stress on operant drinking of alcoholics and social drinkers. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1974;12:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(74)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg CA, Curtin JJ. Alcohol selectively reduces anxiety but not fear: Startle response during unpredictable versus predictable threat. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:335–347. doi: 10.1037/a0015636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts 2001: a compilation of motor vehicle crash data from the fatality analysis reporting system and the general estimates system. U.S. Department of Transportation; Washington, DC: 2002. [accessed on October 20, 2015]. http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov. [Google Scholar]

- *.Nosen E, Nillni YI, Berenz EC, Schumacher JA, Stasiewicz PR, Coffey SF. Cue-elicited affect and craving: Advancement of the conceptualization of craving in co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Behavior Modification. 2012;36:808–833. doi: 10.1177/0145445512446741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG. Adolescents' reported reasons for alcohol and marijuana use as predictors of substance use and problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:106–116. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Pihl RO, Giancola PR, Peterson JB. Cardiovascular reactivity as a predictor of alcohol consumption in a taste test situation. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1994;50:280–286. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199403)50:2<280::aid-jclp2270500222>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Pihl RO, Yankofsky L. Alcohol consumption in male social drinkers as a function of situationally induced depressive affect and anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 1979;65:251–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00492212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. Rev. ed. [Google Scholar]

- *.Rubonis AV, Colby SM, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Gulliver SB, Sirota AD. Alcohol cue reactivity and mood induction in male and female alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:487–494. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA. An appraisal-disruption model of alcohol's effects on stress responses in social drinkers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:459–476. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, … Gnys M. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Fuse T, Aubin LR, O’Maller SS. Psychological stress, drug cues and cocaine craving. Psychopharmacology. 2000;152:140–148. doi: 10.1007/s002130000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon RL. The opponent-process theory of acquired motivation: The costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. American Psychologist. 1980;35:691–712. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz PR, Bradizza CM, Schlauch RC, Coffey SF, Gulliver SB, Gudleski GD, Bole CW. Affect regulation training (ART) for alcohol use disorders: Development of a novel intervention for negative affect drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;45:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz PR, Maisto SA. Two-factor avoidance theory: The role of negative affect in the maintenance of substance use and substance use disorder. Behavior Therapy. 1993;24:337–356. [Google Scholar]

- *.Steinberg L, Tremblay A, Zack M, Busto UE, Zawertailo LA. Effects of stress and alcohol cues in men with and without problem gambling and alcohol use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;119:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Thomas SE, Bacon AK, Randall PK, Brady KT, See RE. An acute psychosocial stressor increases drinking in non-treatment-seeking alcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2163-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Thomas SE, Merrill JE, von Hofe J, Magid V. Coping motives for drinking affect stress reactivity but not alcohol consumption in a clinical laboratory setting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:115–123. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST. A cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: Role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychological Review. 1990;97:147–168. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar H, Piasecki TM, McCarthy DM, Sher KJ, Heath AC. Ecological evidence that affect and perceptions of drink effects depend on alcohol expectancies. Addiction. 2015;110:1432–1442. doi: 10.1111/add.12982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Sobell MB, Maisto SA. Normal drinkers' alcohol consumption as a function of conflicting motives induced by intellectual performance stress. Addictive Behaviors. 1980;5:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(80)90035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Mean age by Race and Hispanic Origin: 2012 and 2060. 2017 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/cspan/pop_proj/20121214_cspan_popproj_12.pdf.

- *.Vinci C, Peltier MR, Shah S, Kinsaul J, Waldo K, McVay MA, Copeland AL. Effects of a brief mindfulness intervention on negative affect and urge to drink among college student drinkers. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;59:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vevea JL, Woods CM. Publication bias in research synthesis: Sensitivity analysis using A priori weight functions. Psychological Methods. 2005;10:428–443. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.10.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vevea JL, Hedges LV. A general linear model for estimating effect size in the presence of publication bias. Psychometrika. 1995;60(3):419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metaphor package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- *.Wardell JD, Read JP, Curtin JJ, Merrill JE. Mood and implicit alcohol expectancy processes: Predicting alcohol consumption in the laboratory. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm N, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: Patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104:1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray JM, Godleski SA, Tiffany ST. Cue-reactivity in the natural environment of cigarette smokers: The impact of photographic and in vivo smoking stimuli. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:733–737. doi: 10.1037/a0023687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Zack M, Poulos CX, Fragopoulos F, Woodford TM, MacLeod CM. Negative affect words prime beer consumption in young drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, Smith GT. Less drinking, yet more problems: Understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:188–223. doi: 10.1037/a0032113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]