Abstract

Objective

To evaluate factors associated with incident self-reported vaginal dryness and the consequences of this symptom across the menopausal transition in a multi-racial/ethnic cohort of community-dwelling women.

Methods

We analyzed questionnaire and biomarker data from baseline and 13 approximately annual visits over 17 years (1996–2013) from 2435 participants in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation, a prospective cohort study. We used discrete-time Cox proportional-hazards regression to identify predictors of incident vaginal dryness and to evaluate vaginal dryness as a predictor of sexual intercourse pain and changes in sexual intercourse frequency.

Results

The prevalence of vaginal dryness increased from 19.4% among all women at baseline (ages 42–53 years) to 34.0% at the thirteenth visit (ages 57–69 years). Advancing menopausal stage, surgical menopause, anxiety and being married were positively associated with developing vaginal dryness, regardless of partnered sexual activity. For women not using hormone therapy, higher concurrent levels of endogenous estradiol were inversely associated (multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio: 0.94 per 0.5 standard deviation increase, 95% confidence interval: 0.91–0.98). Concurrent testosterone levels, concurrent dihydroepiandrosterone-sulfate levels, and longitudinal change in any reproductive hormone were not associated with developing vaginal dryness. Both vaginal dryness and lubricant use were associated with subsequent reporting of pain during intercourse, but not with a decline in intercourse frequency.

Conclusion

In these longitudinal analyses, our data support many clinical observations about the relationship between vaginal dryness, menopause, and pain during intercourse, and suggest that reporting of vaginal dryness is not related to androgen level or sexual intercourse frequency.

Keywords: vaginal dryness, menopause, dyspareunia, sexual function

Introduction

Vaginal dryness, a symptom of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause, increases with age and advancing menopausal stage (1, 2). Vaginal dryness may be caused by reduced secretory function of the vaginal epithelium, which is associated with decreased vaginal blood flow, mucosal thinning, microbiome changes, and inflammation (3, 4). Women may report vaginal dryness as irritation, itching, or burning outside of sexual activities. Most women experience vaginal dryness a perceived reduction in lubrication during sexual activity. Vaginal dryness can lead to painful sex, low libido, and decreased sexual satisfaction (5).

The menopause transition (MT) is an important time in genital tract aging. The cyclical, higher levels of estradiol (E2) of premenopause change to widely varying levels in perimenopause and to the more consistent, lower levels in postmenopause. In cross-sectional studies, low E2 levels and a decline in E2 are associated with a higher prevalence of vaginal dryness symptoms (6). However, the longitudinal relationships between MT stages, reproductive hormone changes, the development vaginal dryness, and this symptom’s potential sexual consequences have not been well studied.

Our primary objective was to evaluate longitudinally, from pre- to post-menopause, factors associated with the development and consequences of reported vaginal dryness in a racially and ethnically diverse cohort of community-dwelling women enrolled in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). We hypothesized that MT stage, lower serum levels of and a decline in E2, and psychosocial factors would be associated with incident vaginal dryness which would then precede new onset pain during intercourse and reduced sexual intercourse frequency.

Methods

Study participants

This was a longitudinal analysis of approximately annual questionnaire and biomarker data with repeated measures over 17 years (1996–2013) in SWAN, a multi-center, multi-racial/ethnic cohort study of the MT (7). The study began with a cross-sectional survey of 16,065 community-dwelling midlife women recruited by random–digit-dialing and/or list-based sampling. From this group, each of seven clinical sites recruited approximately 450 women for the prospective cohort study (3302 women). Inclusion criteria for the cohort were: 1) age 42–52 years; and 2) self-identification of race or ethnicity as African-American (Detroit, MI; Chicago, IL; Pittsburgh, PA; and Boston, MA sites); Hispanic (Newark, NJ site), Japanese (Los Angeles, CA site), Chinese (Oakland, CA site) or white (all sites). Exclusion criteria were: 1) inability to speak English, Spanish, Japanese, or Cantonese; 2) no menstrual period within three months before enrollment; 3) hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy prior to onset of study; 4) using any reproductive hormone therapy at enrollment; or 5) pregnant or lactating. All women consented for participation in SWAN, and the institutional review boards at each site approved the study.

Of the 3302 enrolled participants at baseline, 24 were missing data on the frequency of vaginal dryness at baseline, and four reported use of antineoplastic medication which are known to cause vaginal dryness. We included the remaining 3274 women in analyses of reported frequency of vaginal dryness at baseline. For our longitudinal analyses, we excluded 637 women who reported vaginal dryness at baseline, five women who initiated use of anti-neoplastic during follow-up, and 197 with no follow-up data, leaving a longitudinal analytic sample of 2435 participants.

Measures

At baseline and at each of the 13 approximately annual follow-up visits, a self-administered questionnaire elicited recall of vaginal dryness frequency over the past two weeks on a five-point scale (responses were “not at all,” “1–5 days,” “6–8 days,” “9–13 days,” “everyday”). Because frequency of vaginal dryness is not an indicator of perceived symptom severity, and may simply reflect frequency of sexual activity over the previous two weeks, we collapsed responses to this question into a dichotomous variable: any reported vaginal dryness (1 day – every day) versus none (not at all). We defined incident vaginal dryness as a new report of any vaginal dryness in women who had not previously reported this symptom. At baseline and annual follow-up visits 1 through 6, 8, 10, and 12, women were asked about frequency of lubricant use “During the past 6 months how often have you used lubricants, such as creams or jellies, to make sex more comfortable?” and pain during intercourse “During the past 6 months, have you felt vaginal or pelvic pain during intercourse?” Response options for both questions were “never”, “almost never,” “sometimes” “almost always” “always”. We defined sexually active as vaginal sexual activity with a partner for women who reported frequency of intercourse as “once or twice a month,” “about once per week,” “more than once per week,” or “daily” or reported any lubricant use or pain during intercourse. We categorized sexual frequency as “less than monthly” for women who answered “none” to frequency of intercourse but reported at least sometimes to lubricant use or pain during intercourse. Gender of sexual partners was assessed at baseline only.

SWAN annual serum measures of E2 (through visit 13), T and DHEAS (through visit 10) were drawn in days 2–5 of the menstrual cycle for pre- and peri-menopausal women and at any time for postmenopausal women. All endocrine assays were performed on the Automated Chemiluminesence System (ACS)-180 analyzer (Bayer Diagnostics Corporation, Tarrytown, NY) using a double-antibody chemiluminescent immunoassay with a solid phase anti-IgG immunoglobulin conjugated to paramagnetic particles, anti-ligand antibody, and competitive ligand labeled with dimethylacridinium ester (8). The E2 assay modified the rabbit anti-E2-6 ACS-180 immunoassay to increase sensitivity, with a lower limit of detection of 1.0 pg/mL. Duplicate E2 assays were conducted with results reported as the arithmetic mean for each participant, with a coefficient of variation of 3–12%. All other assays were single determinations. The T assay modified the rabbit polyclonal anti-testosterone ACS-180 immunoassay. The DHEAS and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) assays were developed on site using rabbit anti-DHEAS and anti-SHBG antibodies.

SWAN classified menopausal status from menstrual bleeding patterns as: premenopausal—less than three months of amenorrhea and no menstrual irregularities in the previous year, early perimenopausal—less than three months of amenorrhea and some menstrual irregularities in the previous year, late perimenopausal—three to 11 months of amenorrhea, and postmenopausal—at least 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea. Postmenopausal status was further subdivided by users and non-users of exogenous systemic menopausal hormone therapy (HT). Additional categories included unknown menopause status due to concurrent exogenous HT in women who were not known to be postmenopausal and hysterectomy with and without bilateral oophorectomy (BSO), each subdivided by concurrent use of exogenous HT.

We calculated body mass index (BMI) as weight in kilograms/height in meters2 based on measurements taken annually by certified staff using calibrated scales and stadiometers. At each visit, interviewers obtained smoking history (9) and medication use. In annual self-report questionnaires, information was elicited about general health, depressive symptoms (10), and anxiety symptoms (11).

Statistical analyses

We estimated the prevalence of any reported vaginal dryness in the past two weeks as a function of years before/after the final menstrual period in the subset of 1593 women (19,119 observations) with the final menstrual period observed prior to initiation of hormone therapy, hysterectomy, or bilateral oophorectomy. To allow for maximum flexibility in this trajectory, we used nonparametric locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) (12). We compared baseline demographic and sexual activity characteristics with any report of vaginal dryness in the past two weeks using analysis of variance or chi-square testing.

To identify predictors of incident vaginal dryness, we used discrete-time Cox proportional-hazards regression (13) to accommodate the approximately annual nature of longitudinal data collection. Analyses were conducted on three separate analytic samples. In our first analysis, we included all visits and all covariates, except exogenous HT use and characteristics relevant only for visits when women reported sexual activity. Second, we estimated associations between reported vaginal dryness and endogenous hormones, restricting the analytic sample to visits with no exogenous HT use at the current or prior visit. Third, we analyzed associations with characteristics relevant only for sexually active women, restricting the analytic sample to visits with partnered vaginal sexual activity. All analyses omitted observations occurring on or after initiation of antineoplastic or fertility medications, and observations with concurrent pregnancy or lactation due to small numbers in these groups. We estimated unadjusted associations by including each covariate separately, and also assessed adjusted associations in a multivariate model using backward elimination (p<0.05) to omit irrelevant predictors. We estimated separate models for each reproductive hormone due to collinearity of hormones. To allow the associations with incident vaginal dryness to vary by partner status, we tested the interaction of each covariate with partner status.

Because vaginal lubricants and vaginal estrogen are used frequently to manage vaginal dryness symptoms, and their use could alter the reporting of vaginal dryness symptoms, we ran sensitivity analyses including any lubricant or vaginal estrogen use as indicators of vaginal dryness. Additionally, we compared analyses with and without imputation/interpolation of missing variables. In both cases, results were similar (data not shown); so, we have only shown those without imputation.

Since vaginal dryness, pain during intercourse, and decreasing intercourse frequency are clinically and behaviorally intertwined, we performed two additional analyses to investigate these relationships. First, we used discrete-time Cox regression to estimate hazard ratios (HR) for reporting any incident pain during intercourse in relation to vaginal dryness alone, lubricant use alone and vaginal dryness and lubricant use together as independent variables among the 1551 sexually active women who reported no pain during intercourse at baseline. We also conducted binomial logistic regression (14) to examine whether reporting of vaginal dryness alone, lubricant use alone, or vaginal dryness and lubricant use together had preceded a decline in intercourse frequency among 2551 sexually active women at two consecutive visits. All models included age, race/ethnicity, SWAN study site and time-varying putative factors related to outcomes with a p-value less than 0.05, including BMI, menopausal status and HT use, as well as time-varying sexual activity factors. For all analyses, we selected covariates a priori based on the literature (1, 2, 15). We used backward elimination (p<0.05) to omit irrelevant or redundant predictors and selected our final models based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for model fit (16). All analyses were performed in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Descriptive findings

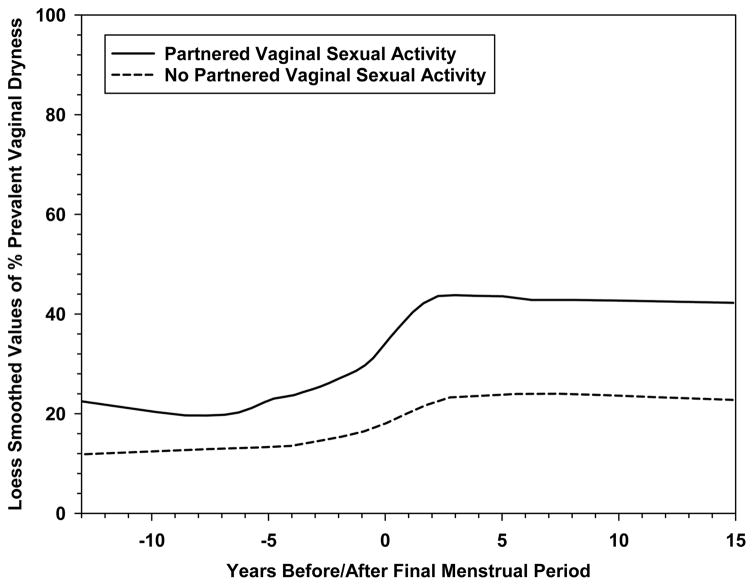

Baseline characteristics of women who reported any versus no vaginal dryness in the previous two weeks are presented in Table 1. At baseline, when all participants were pre- or early peri-menopausal, 13.1% of women who were not sexually active and 21.5% of sexually active women (19.6% of all women) recalled vaginal dryness occurring at least one day in the previous two weeks. Over the 17 years of SWAN, 1470 women (60%) who had not reported vaginal dryness at baseline, reported vaginal dryness at least one study visit. By the end of the study period (visit 13) when 97% of participants were known to be postmenopausal (ages 57–69 years), 25.3% of women who were not sexually active and 47.0% of sexually active women (34.0% of all women) reported vaginal dryness. Vaginal dryness increased in prevalence as the MT progressed, with the most rapid rise around the final menstrual period (Figure 1). None of the 44 women who reported generally having sex with a women at the baseline assessment reported vaginal dryness during follow up. Any lubricant use, measured among sexually active women only, also increased between baseline (25.2%) and visit 13 (63.5%), and frequent lubricant use (almost always/always) increased from 7.5% to 39.9%. For women who generally reported having sex with women, the median percent lubricant use for all visits was 9%. Women reported using vaginal estrogen infrequently over the 17 years, from 0% at baseline to 3.5% (5.9% for women engaged and 1.9% for women not engaged in sexual activity) at visit 13.

Table 1.

SWAN baseline characteristics by vaginal dryness frequency in past two weeks (1996–2013)

| % (N) or Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic at Baseline | None (N=2637) | Any (N=637) | p-value |

| Partnered sexual activity in past 6 months | 74.8 (1925) | 84.4 (528) | <0.0001 |

| Married/living as married | 64.5 (1670) | 73.3 (462) | <0.0001 |

| Menopausal status: | <0.0001 | ||

| Premenopausal | 55.9 (1456) | 46.4 (292) | |

| Early perimenopausal | 44.1 (1147) | 53.6 (337) | |

| Age, years | 46.3 (2.7) | 46.5 (2.8) | 0.104 |

| Race/ethnicity: | <0.0001 | ||

| White | 47.1 (1241) | 47.3 (301) | |

| African American | 28.3 (746) | 26.8 (171) | |

| Chinese | 7.8 (205) | 7.1 (45) | |

| Hispanic | 7.5 (197) | 13.8 (88) | |

| Japanese | 9.4 (248) | 5.0 (32) | |

| Current smoking | 17.3 (453) | 17.4 (110) | 0.953 |

| BMI (kg/m2): | 0.856 | ||

| <25 | 40.4 (1051) | 40.1 (252) | |

| 25 – 29.9 | 26.9 (699) | 26.1 (164) | |

| 30+ | 32.8 (853) | 33.9 (213) | |

| Self-reported health: | 0.001 | ||

| Excellent | 22.4 (581) | 17.2 (108) | |

| Very good | 37.0 (958) | 33.8 (212) | |

| Good | 28.3 (733) | 32.6 (205) | |

| Fair/Poor | 12.4 (321) | 16.4 (103) | |

| CES-D ≥ 16 | 22.4 (590) | 31.5 (200) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety score ≥ 4 | 20.1 (524) | 33.6 (212) | <0.0001 |

| Symptom sensitivity score | 10.1 (3.6) | 10.5 (3.5) | 0.043 |

| Frequency of intercourse* | 0.070 | ||

| <monthly | 0.7 (13) | 1.2 (6) | |

| 1 – 2 times/month | 35.7 (678) | 30.7 (160) | |

| At least weekly | 63.7 (1210) | 68.1 (355) | |

| Frequency of pain with intercourse* | <0.0001 | ||

| Never | 61.7 (1180) | 13.3 (181) | |

| Almost never | 22.2 (425) | 23.7 (124) | |

| Sometimes | 14.7 (281) | 36.1 (189) | |

| Almost always | 1.2 (22) | 4.0 (21) | |

| Always | 0.3 (5) | 1.7 (9) | |

| Frequency of lubricant use* | <0.0001 | ||

| Never | 82.3 (1576) | 47.2 (248) | |

| Almost never | 7.0 (133) | 10.7 (56) | |

| Sometimes | 6.7 (129) | 21.9 (115) | |

| Almost always | 2.0 (38) | 11.8 (62) | |

| Always | 2.0 (39) | 8.6 (45) | |

P values are from X2 and t-tests

Participants with partnered sexual activity in past 6 months only

Figure 1. LOESS plot of prevalence of any vaginal dryness in the prior 2 weeks in an 18-year period bracketing the final menstrual period.

Figure represents 1593 women (19,119 observations) with the final menstrual period observed prior to initiation of hormone therapy, hysterectomy, or bilateral oophorectomy.

Unadjusted findings

In unadjusted analyses (Table 2), the HR of incident vaginal dryness increased through the MT, beginning in early perimenopause for both sexually active and sexually inactive women. Having a BSO (with or without HT) increased the HR signficantly for women who were not sexually active. Compared with white women, Hispanic women had a higher HR of reporting vaginal dryness, regardless of sexual activity and adjustment for diabetes (data not shown). African American were more likely than white women to report onset of this symptom when not sexually active (p-value for interaction of race/ethnicity with sexual activity: 0.03). Fair to poor health and depressive and anxiety symptoms were also positively associated with reporting incident vaginal dryness, regardless of sexual activity status. Concurrent higher E2 level was associated with a lower probability of incident vaginal dryness in sexually active women while absolute T and DHEAS levels and change in E2, T and DHEAS levels were not associated with vaginal dryness. For women engaged in sexual activity, more frequent use of sexual lubricants and more frequent pain during intercourse at both the prior and concurrent visit, were associated with a higher HR of incident vaginal dryness.

Table 2.

Unadjusted associations(a) with incidence of any vaginal dryness in SWAN by sexual activity with a partner status (1996–2013).

| Not Sexually Active | Sexually Active with Partner | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | p-value for interaction with sexual activity |

| Concurrent partnered sexual activity | Reference | 1.87 (1.63, 2.15) | <0.001 | ||

| Concurrent menopausal status/HT use: | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.163 | ||

| Premenopausal | Reference | Reference | |||

| Early perimenopausal | 2.78 (1.49, 5.17) | 1.60 (1.25, 2.05) | |||

| Late perimenopausal | 3.50 (1.73, 7.09) | 3.16 (2.34, 4.27) | |||

| Postmenopausal | 4.25 (2.23, 8.12) | 3.56 (2.64, 4.82) | |||

| Postmenopausal-HT | 2.76 (1.13, 6.72) | 1.35 (0.77, 2.38) | |||

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | 3.80 (1.04, 13.87) | 2.29 (0.99, 5.31) | |||

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy-HT | 3.77 (1.20, 11.88) | 2.12 (1.14, 3.91) | |||

| Hysterectomy | 1.82 (0.40, 8.23) | 2.90 (1.63, 5.16) | |||

| Hysterectomy-HT | 3.90 (0.50, 30.28) | 1.71 (0.24, 12.35) | |||

| Not postmenopausal – HT | 3.84 (1.88, 7.82) | 1.79 (1.29, 2.49) | |||

| Concurrent vaginal estrogen | 6.05 (1.93, 18.99) | 0.002 | 2.72 (1.40, 5.28) | 0.003 | 0.270 |

| Race/ethnicity: | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.027 | ||

| White | Reference | Reference | |||

| African American | 1.41 (1.07, 1.85) | 1.10 (0.93, 1.29) | |||

| Chinese | 0.94 (0.56, 1.56) | 1.17 (0.93, 1.48) | |||

| Hispanic | 3.02 (2.06, 4.41) | 1.69 (1.28, 2.23) | |||

| Japanese | 0.74 (0.47, 1.17) | 0.94 (0.75, 1.18) | |||

| Concurrent smoking | 1.19 (0.85, 1.66) | 0.309 | 1.01 (0.83, 1.22) | 0.932 | 0.408 |

| Concurrent BMI (kg/m2): | 0.269 | 0.130 | 0.106 | ||

| < 25 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 25 – 29.9 | 1.13 (0.81, 1.58) | 0.85 (0.72, 1.00) | |||

| 30+ | 1.27 (0.95, 1.69) | 0.90 (0.77, 1.06) | |||

| Concurrent self-reported health: | 0.002 | 0.059 | 0.164 | ||

| Excellent | Reference | Reference | |||

| Very good | 0.86 (0.57, 1.28) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.36) | |||

| Good | 1.21 (0.82, 1.78) | 1.18 (0.97, 1.44) | |||

| Fair/Poor | 1.59 (1.05, 2.42) | 1.40 (1.09, 1.78) | |||

| Concurrent CES-D ≥ 16 | 1.81 (1.41, 2.33) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.07, 1.54) | 0.007 | 0.032 |

| Concurrent anxiety ≥ 4 | 2.74 (2.15, 3.50) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.56, 2.16) | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| Symptom sensitivity per unit increase | 1.03 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.141 | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | <0.001 | 0.463 |

| Currently married/partnered | 1.29 (1.00, 1.65) | 0.047 | 1.09 (0.92, 1.29) | 0.313 | 0.278 |

| Concurrent log hormones(b) | |||||

| E2 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.01) | 0.090 | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) | 0.008 | 0.834 |

| T | 1.03 (0.95, 1.10) | 0.502 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.07) | 0.214 | 0.991 |

| DHEAS | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) | 0.754 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.718 | 0.931 |

| E2 change, prior to current visit(c) | 0.450 | 0.129 | 0.842 | ||

| Decrease | 0.83 (0.58, 1.19) | 0.93 (0.76, 1.13) | |||

| Stable | Reference | Reference | |||

| Increase | 1.08 (0.73, 1.60) | 1.18 (0.96, 1.46) | |||

| T change, prior to current visit(c) | 0.285 | 0.179 | 0.844 | ||

| Decrease | 1.38 (0.92, 2.06) | 1.21 (0.98, 1.48) | |||

| Stable | Reference | Reference | |||

| Increase | 1.21 (0.83, 1.76) | 1.14 (0.94, 1.40) | |||

| DHEAS change, prior to current visit(c) | 0.910 | 0.643 | 0.964 | ||

| Decrease | 1.07 (0.74, 1.56) | 1.04 (0.85, 1.27) | |||

| Stable | Reference | Reference | |||

| Increase | 1.00 (0.69, 1.45) | 0.95 (0.78, 1.15) | |||

| Concurrent intercourse frequency: | 0.087 | ||||

| < monthly | Reference | ||||

| 1–2x/month | 0.76 (0.43, 1.36) | ||||

| ≥ weekly | 0.88 (0.50, 1.57) | ||||

| Concurrent lubricant use: | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | Reference | ||||

| Sometimes/Almost never | 2.57 (2.20, 3.00) | ||||

| Always/almost always | 4.18 (3.47, 5.05) | ||||

| Concurrent pain with intercourse: | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | Reference | ||||

| Sometimes/Almost never | 2.83 (2.46, 3.25) | ||||

| Always/almost always | 5.18 (3.81, 7.03) | ||||

| Prior-visit intercourse frequency: | 0.021 | ||||

| None | Reference | ||||

| < monthly | 1.41 (0.64, 3.09) | ||||

| 1–2x/month | 0.69 (0.51, 0.92) | ||||

| ≥ weekly | 0.82 (0.62, 1.08) | ||||

| Prior-visit lubricant use: | <0.001 | ||||

| No intercourse | 1.49 (1.13, 1.96) | ||||

| Never | Reference | ||||

| Sometimes/Almost never | 1.59 (1.31, 1.94) | ||||

| Always/almost always | 2.29 (1.74, 3.03) | ||||

| Prior-visit pain with intercourse: | <0.001 | ||||

| No intercourse | 1.63 (1.23, 2.17) | ||||

| Never | Reference | ||||

| Sometimes/Almost never | 1.71 (1.46, 2.00) | ||||

| Always/almost always | 2.38 (1.36, 4.14) | ||||

Models include baseline age and time since baseline

Visits with exogenous HT use excluded; hormones log-transformed; analyses with log E2 adjust for whether blood draw was in days 2–5 of menstrual cycle in pre- and peri-menopause

Visits with concurrent or prior-visit exogenous HT use excluded; adjusted for current-visit log-transformed hormone; analyses with log E2 also adjust for blood draw in days 2–5 of menstrual cycle at current and prior visit in pre- and peri-menopause; stable indicates change ≤ 0.5 SD

2435 participants in analytic sample: 9 excluded when initiated antineoplastic medication, 24 missing baseline vaginal dryness; 637 excluded who reported vaginal dryness at baseline, 197 dropped out after baseline

Multivariable results

In adjusted analyses, we examined the relations between selected covariates and incident vaginal dryness in three analytic samples of SWAN women: all women eligible for this current analysis, women who did not use HT, and only women reporting sexual activity (Table 3). For all samples, advancing menopausal stage, surgical menopause, anxiety symptoms, and married status remained positively associated with developing vaginal dryness, regardless of sexual activity. Current anxiety symptoms was the only factor modified by sexual activity; the association between concurrent sexual activity and incident vaginal dryness was stronger in women with lower anxiety. Conversely current higher anxiety symptom score showed a stronger association with vaginal dryness in women reporting no sexual activity compared to sexually active women. Use of exogenous HT appeared to be associated with a smaller HR of incident vaginal dryness in women with natural postmenopausal status (covariate-adjusted p=0.001 for HT), compared to women with BSO or hysterectomy (combining BSO and hysterectomy, covariate-adjusted p=0.49 for HT, p-value for interaction=0.013). For women not using HT, higher levels of endogenous E2 in the concurrent visit remained inversely associated with the development of vaginal dryness in women at all menopausal stages (Table 3) and in a subanalysis of only postmenopausal women, regardless of their BMI (data not shown). Neither concurrent T nor DHEAS levels nor change in any reproductive hormone from the prior visit predicted incident vaginal dryness. For women engaged in sexual activity, the more frequent use of lubricants or reports of pain in the concurrent visit the higher the HR of incident vaginal dryness, even after adjustment for other predictors. We found that HRs for developing vaginal dryness increased with higher frequency of lubricant use and pain during intercourse at the prior visit; the impact of adjustment for other predictors was minimal.

Table 3.

Multivariable-adjusted associations with incident vaginal dryness in SWAN (1996–20013)

| Characteristic | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI)(a) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| All women/All visits (N = 2246 women/10421 visits) | ||

| Concurrent partnered sexual activity, stratified by concurrent anxiety (b) | ||

| Anxiety symptom score < 4 | 2.21 (1.81, 2.70) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety symptom score ≥ 4 | 1.36 (1.03, 1.79) | 0.029 |

| Concurrent menopausal Status/HT use | <0.0001 | |

| Premenopausal | Reference | |

| Early perimenopausal | 1.67 (1.31, 2.13) | |

| Late perimenopausal | 2.98 (2.21, 4.02) | |

| Postmenopausal | 3.48 (2.57, 4.71) | |

| Postmenopausal-HT | 1.57 (0.94, 2.61) | |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | 2.19 (0.99, 4.84) | |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy-HT | 2.70 (1.56, 4.67) | |

| Hysterectomy | 2.21 (1.19, 4.10) | |

| Hysterectomy-HT | 2.74 (0.67, 11.20) | |

| Not postmenopausal, HT | 2.03 (1.49, 2.77) | |

| Concurrent vaginal estrogen | 2.97 (1.62, 5.45) | 0.003 |

| Race/ethnicity: | 0.101 | |

| White | Reference | |

| African American | 1.08 (0.91, 1.29) | |

| Chinese | 0.86 (0.64, 1.16) | |

| Hispanic | 1.74 (1.08, 2.78) | |

| Japanese | 1.11 (0.82, 1.51) | |

| Concurrent BMI (kg/m2): | 0.011 | |

| < 25 | Reference | |

| 25 – 29.9 | 0.82 (0.70, 0.96) | |

| 30+ | 0.80 (0.68, 0.94) | |

| Concurrent anxiety ≥ 4 vs. < 4, stratified by concurrent partnered sexual activity(b) | ||

| Not sexually active visit | 2.56 (1.96, 3.35) | <0.001 |

| Sexually active visit | 1.57 (1.31, 1.89) | <0.001 |

| Symptom sensitivity, 1-unit increase | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | 0.011 |

| Currently married/partnered | 1.20 (1.02, 1.40) | 0.024 |

| Visits in Which Women Report No Hormone Therapy Use (N = 2068 – 2072 women/7196 – 7577 visits) | ||

| Concurrent log hormones, 0.5 SD:(c) | ||

| E2 | 0.94 (0.91, 0.98) | 0.002 |

| T | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.382 |

| DHEAS | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.555 |

| E2 change, prior visit to current visit(d) | 0.126 | |

| Decrease | 0.89 (0.74, 1.06) | |

| Stable | Reference | |

| Increase | 1.12 (0.92, 1.35) | |

| T change, prior visit to current visit(d) | 0.134 | |

| Decrease | 1.19 (0.99, 1.44) | |

| Stable | Reference | |

| Increase | 1.16 (0.96, 1.40) | |

| DHEAS change, prior visit to current visit(d) | 0.323 | |

| Decrease | 1.01 (0.84, 1.21) | |

| Stable | Reference | |

| Increase | 0.89 (0.75, 1.07) | |

| Visits in Which Women Report Partnered Sexual Activity(e) (N = 1771 women/6515 visits for concurrent-visit predictors, N=1745 women/5532 visits for prior-visit predictors) | ||

| Concurrent intercourse frequency: | 0.107 | |

| < monthly | Reference | |

| 1–2x/month | 0.74 (0.41, 1.32) | |

| ≥ weekly | 0.86 (0.48, 1.53) | |

| Concurrent lubricant use: | <0.001 | |

| Never | Reference | |

| Sometimes/almost never | 2.53 (2.14, 3.00) | |

| Always/almost always | 4.31 (3.53, 5.26) | |

| Concurrent pain with intercourse: | <0.001 | |

| Never | Reference | |

| Sometimes/almost never | 2.98 (2.56, 3.46) | |

| Always/almost always | 4.68 (3.36, 6.50) | |

| Prior-visit intercourse frequency: | 0.412 | |

| None | Reference | |

| < monthly | 1.17 (0.46, 2.97) | |

| 1–2x/month | 0.81 (0.59, 1.12) | |

| ≥weekly | 0.91 (0.67, 1.24) | |

| Prior-visit lubricant use: | <0.001 | |

| No intercourse | 1.30 (0.96, 1.76) | |

| Never | Reference | |

| Sometimes/almost never | 1.64 (1.34, 2.01) | |

| Always/almost always | 2.11 (1.58, 2.84) | |

| Prior-visit pain with intercourse: | <0.001 | |

| No intercourse | 1.44 (1.05, 1.96) | |

| Never | Reference | |

| Sometimes/almost never | 1.73 (1.46, 2.04) | |

| Always/almost always | 2.08 (1.16, 3.72) | |

Also adjusted for site and baseline age,

p-value for sexual activity × anxiety = 0.003

Visits with exogenous HT use excluded; analyses with log E2 adjusted for blood draw in days 2–5 of menstrual cycle; adjusted for partnered sexual activity through marital status, site and baseline age

Visits with concurrent/prior-visit exogenous HT use excluded; adjusted for current-visit log-transformed hormone; analyses with log E2 adjusted for blood draw in days 2–5 of menstrual cycle; stable indicates change ≤ 0.5 SD; adjusted for partnered sexual activity through marital status, site and baseline age

Adjusted for variables menopause status through marital status, site and baseline age

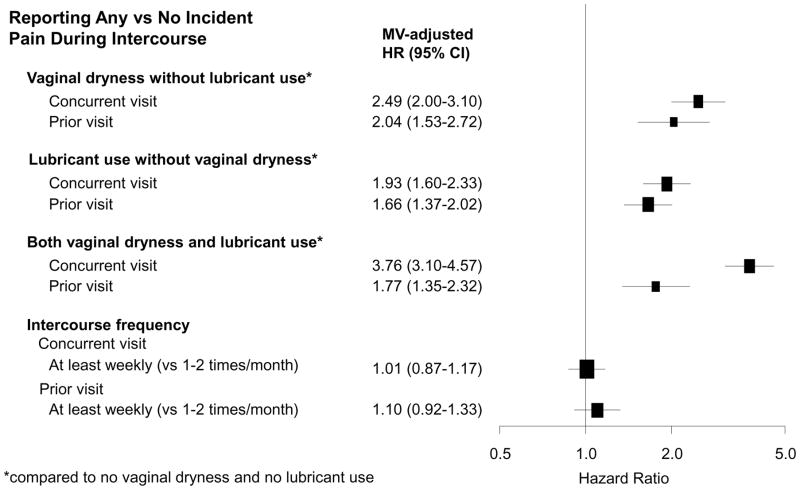

To examine the longitudinal relationship between vaginal dryness and lubricant use and the development of pain during intercourse, we used any reporting of vaginal dryness alone, lubricant use alone, and both vaginal dryness and lubricant use as independent variables among sexually active women. In women who did not report any pain during intercourse at baseline, we found that concurrent visit reporting of vaginal dryness and lubricant use were positively associated with incident pain during intercourse (Figure 2a) regardless of age, menopausal status, BMI and hormone use. Women who reported vaginal dryness with lubricant use together in the concurrent visit had the highest HR of reporting new onset pain during intercourse, likely representing severity of their vaginal dryness with their behavior of lubricant use to treat it. Meanwhile, developing pain with intercourse was not associated with intercourse frequency at the visit before or visit of reporting new onset pain.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios for reporting incident pain during intercourse. Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios for reporting incident pain during intercourse in relation to reporting of vaginal dryness alone, lubricant use alone, vaginal dryness and lubricant use together, and intercourse frequency in SWAN (1996–2013) among 1,474 women who reported having partnered sexual activity in 4,764 visits; excluding women who reported pain during intercourse at baseline and women with missing baseline partner status (and thus missing baseline pain). Models included variable of interest one at a time (for example, vaginal dryness at concurrent visit) and adjusted for age, race and ethnicity, site, menopausal status and hormone use, BMI, anxiety (score ≥ 4), and symptom sensitivity score. Bracket size is proportional to sample size.

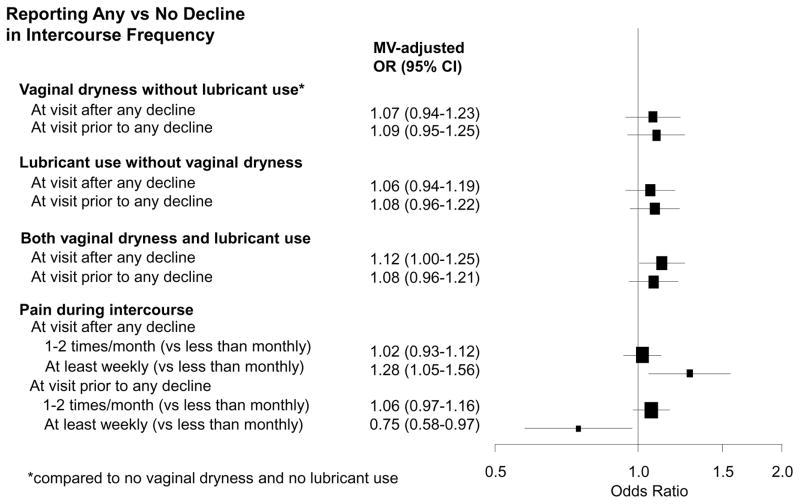

Figure 2b. Multivariable-adjusted odds ratio for reporting decline in intercourse frequency. Multivariable-adjusted odds ratio for reporting decline in intercourse frequency in relation to vaginal dryness, lubricant use, and pain during intercourse in SWAN (1996–2013) among 2364 women who reported having sexual partners in 13,047 visits. Models included variables of interest one at a time (for example, vaginal dryness at concurrent visit) and adjusted for age at current visit, site, race and ethnicity, years between visits, menopausal status and hormone use, BMI, CES-D (score ≥ 16), smoking, and marital status. Bracket size is proportional to sample size.

We also examined longitudinally whether reporting of vaginal dryness alone, lubricant use alone, and vaginal dryness and lubricant use together predicted a decline in intercourse frequency among women reporting sexually activity across the 13 years of follow up. Regardless of age, menopausal status, BMI, and hormone use, only women reporting both vaginal dryness and lubricant use together had a decline in intercourse frequency from the previous visit. Interestingly, we found that at least weekly pain during intercourse was associated with an increased odds of decline in intercourse frequency from the previous visit, whereas at least weekly pain during intercourse reported prior to the measured change in intercourse frequency had a reduced odds of decline in intercourse frequency. (Figure 2b).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study following a large multi-racial and ethnic sample of community-dwelling women over 17 years across the MT, we found that, after controlling for age, advancing natural menopausal stage and surgical menopause were the factors most strongly associated with new reporting of any vaginal dryness within the previous two weeks. Higher concurrent endogenous levels of E2 were associated with a reduced probability of incident vaginal dryness, while neither concurrent endogenous T and DHEAS levels nor change in any reproductive hormone was associated with the development of this symptom.

Lower concurrent serum levels of estrogen have been associated with vaginal dryness in other studies (15), while few studies have focused on the relationship between changes in serum E2 over time and incident vaginal dryness symptoms. Our somewhat surprising lack of association between declines in E2 and incident vaginal dryness could be explained by a number of factors. For example, declines between two measurements approximately one year apart may not represent the hormonal patterns over a longer time frame. A change in serum E2 may not correspond to changes in the hormone’s effect on the vaginal epithelium. Early follicular phase pre- and peri-menopausal E2 levels may not be the best values for predicting effects on vaginal dryness. The strong association we found between incident vaginal dryness and advancing menopausal stage likely better reflects the complexity of factors involved in development of vaginal dryness, such as the psychosocial impact of menopause and variations in physiological change. Our finding that systemic HT may have differential effects on the development of vaginal dryness depending on a natural MT versus surgical menopause, is novel. While we had small numbers in our surgical menopause group, other explanations include differences in type or dose of HT prescribed, different indications or timing for starting HT, or unclear biological factors.

Independent of menopausal stage and E2 level, we found several other factors associated with incident vaginal dryness, regardless of sexual activity. That Hispanic women were more likely to report incident vaginal dryness is consistent with prevalence estimates from SWAN cross-sectional reports (2, 17, 18) as well as other large studies (19). In these studies, region of origin, but not primary language, immigrant status or perceived quality of life were associated with vaginal dryness reporting (18, 19). Hispanic women have been noted to have higher reporting of vulvovaginal symptoms such as vulvodynia (20).

We found that concurrent anxiety symptoms were independently related to the development of vaginal dryness, but there was a weaker relationship between concurrent anxiety and vaginal dryness in sexually active women compared to those who were not sexually active. Depressive symptoms have been associated with low libido, whereas anxiety symptoms have been linked to both higher subjective sexual arousal and vaginal lubrication (21) but also lower desire, emotional satisfaction and physical pleasure (2).

In SWAN, we were able to follow women’s reporting of vaginal dryness, sexual intercourse frequency, lubricant use, and pain during intercourse longitudinally over 13 years and found bidirectional relationships. In addition to a strong co-occurrence of vaginal dryness, lubricant use, and pain during intercourse, we found vaginal dryness, lubricant use and both vaginal dryness and lubricant use together were independently associated with the development of pain during intercourse. However, we also found that pain during intercourse preceded new reporting of vaginal dryness, suggesting that sexual pain leads to reduced vaginal lubrication during arousal. We also found that frequency of intercourse at the prior visit, whether 1–2 times per month or more than weekly, was not associated with developing pain during intercourse.

Our study results should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, without confirmation by a detailed history and physical examination, self-reported vaginal dryness is a non-specific symptom that could represent a true reduction in vaginal fluid only or could be construed as a symptom of pathological vulvovaginal conditions. Second, our assessment of vaginal dryness asked the frequency of the symptom over the previous two weeks. Frequency of vaginal dryness within the previous two weeks is likely difficult to recall and may not reflect perceived severity because experience of the symptom may depend largely on frequency of sexual activity; for this reason, we did not analyze vaginal dryness by reported frequency and could not assess severity of the symptom. Additionally, assessments of sexual intercourse, lubricant use, and pain during intercourse elicited perceived frequency over the previous six months, a different time frame from the vaginal dryness symptom question, and these time frame differences may lead to missclassification bias. Third, the strong association we found between vaginal dryness and lubricant use is likely because the symptom and behavior are inextricably intertwined--lubricant use may either mask awareness of or represent a response to vaginal dryness symptoms. To address this, we analyzed vaginal dryness and lubricant use alone and together as both predictors and outcomes. Fourth, we cannot assess whether participant responses to SWAN’s sexual orientation-neutral sexual activity questions were influenced by a perception that they were heterosexual-specific. Finally, while vaginal dryness is most often clinically associated with insertional dyspareunia, pain is not easy to localize. In this regard, our broader defintion of pain during intercourse likely improves the generalizability of our results.

Conclusion

Over 50% of women with vaginal dryness do not report this symptom to their health care provider. (22) While vaginal dryness can be treated successfully and safely in many women with vaginal estrogen tablets, creams and rings, less than 4% of SWAN participants reported using any of these medication by visit 13. In this unique longitudinal analysis, our data support many clinical observations, for example, that the incidence and prevalence of vaginal dryness, regardless of sexual activity, increased with progression through the MT and with lower E2 levels, and that reporting vaginal dryness both precedes and co-occurs with sexual intercourse pain. We also describe some new and clinically relevant findings. The development of any vaginal dryness does not appear to be related to androgen levels or sexual frequency. In sexually active women, less frequent (1–2 time per month) intercourse compared to more frequent (at least weekly) intercourse does not appear to increase the risk of developing pain during intercourse. HT may be less effective in preventing the development of vaginal dryness in women after hysterectomy compared to women experiencing natural menopause.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061; U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH.

We thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN.

Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Siobán Harlow, PI 2011 – present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994–2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA – Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 – present; Robert Neer, PI 1994 – 1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL – Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 – present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994 – 2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser – Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles – Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY – Carol Derby, PI 2011 – present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010 – 2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004 – 2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry – New Jersey Medical School, Newark – Gerson Weiss, PI 1994 – 2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD – Chhanda Dutta 2016- present; Winifred Rossi 2012–2016; Sherry Sherman 1994 – 2012; Marcia Ory 1994 – 2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD – Program Officers.

Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012 - present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 – 2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995 – 2001.

Steering Committee: Susan Johnson, Current Chair

Chris Gallagher, Former Chair

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, et al. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:351–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF, Jr, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16:442–52. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181948dd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canada SoOaGo. The detection and management of vaginal atrophy. Intern J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88:222–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brotman RM, Shardell MD, Gajer P, et al. Association between the vaginal microbiota, menopause status, and signs of vulvovaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2014;21:450–8. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a4690b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon JA, Nappi RE, Kingsberg SA, et al. Clarifying Vaginal Atrophy’s Impact on Sex and Relationships (CLOSER) survey: emotional and physical impact of vaginal discomfort on North American postmenopausal women and their partners. Menopause. 2014;21:137–42. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318295236f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger HG, et al. New findings from non-linear longitudinal modelling of menopausal hormone changes. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:551–7. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sowers M, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, et al. SWAN: A Multicenter, Multiethnic, Community-Based Cohort Study of Women and the Menopausal Transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey JL, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.England BG, Parsons GH, Possley RM, et al. Ultrasensitive semiautomated chemiluminescent immunoassay for estradiol. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1584–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferris B. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society) American Review of Respiratory Diseases. 1978;118:1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–283. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1226–35. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ. Locally weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:596–610. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison PD. Survival Analysis using SAS: a practical guide. Cary, N.C: SAS Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molenberghs G, Verbeke G. Models for discrete longitudinal data. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20:888–902. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182a122c2. quiz 03–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akaike H. Information measures and model selection. Int Stat Inst. 1983;22:277–91. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40–55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green R, Polotsky AJ, Wildman RP, et al. Menopausal symptoms within a Hispanic cohort: SWAN, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Climacteric. 13:376–84. doi: 10.3109/13697130903528272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastore LM, Carter RA, Hulka BS, et al. Self-reported urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative. Maturitas. 2004;49:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed BD, Legocki LJ, Plegue MA, et al. Factors associated with vulvodynia incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:225–31. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalmbach DA, Kingsberg SA, Ciesla JA. How changes in depression and anxiety symptoms correspond to variations in female sexual response in a nonclinical sample of young women: a daily diary study. J Sex Med. 2014;11:2915–27. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, et al. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1790–9. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]