Abstract

The current study examines whether social-emotional difficulties associated with higher body weight vary across schools as a function of the school’s weight climate. Weight climate, characterized by “weight-policing,” was assessed indirectly by examining how strongly self-reported weight predicts victim reputation within 26 ethnically diverse middle schools. Social-emotional indicators included self-reported loneliness, school belonging, and self-esteem. In schools with stronger weight-policing at seventh grade, loneliness was intensified by eighth grade among both girls (n=2,101) and boys (n=1,985) with higher weight. Similar effects were found for low self-esteem among girls. Additionally, boys—regardless of their weight—reported lower sense of belonging in schools with stronger weight-policing. The study offers a new method to estimate school weight climate, and the findings provide insights for interventions.

The Effects of Middle School Weight Climate on Youth with Higher Body Weight

Weight-related ridicule and intimidation by peers is frequent and consequential among young adolescents. At least one in four middle school students report having experienced social exclusion or ridicule because of their weight (Haines, Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan & Robinson-O’Brien, 2008; Juvonen, Lessard, Schacter, & Suchilt, 2017; Lampard, MacLehose, Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer, & Davison, 2014). Youth with overweight and obesity are not only at high risk for such negative social experiences (van Geel, Vedder, & Tanilon, 2014), but peer mistreatment also helps partly account for their subsequent lower self-esteem, depression, and loneliness (e.g., Bucchianeri, Eisenberg, Wall, Piran, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2014; Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer, Haines, & Wall, 2006; Puhl & Luedicke, 2012). Moreover, weight teasing in adolescence predicts obesity and disordered eating 15 years later in adulthood, independent of baseline weight (Puhl, et al. 2017). Although schools vary in rates of weight-related peer mistreatment (Lampard, et al., 2014; Puhl, Luedicke & Heuer, 2011), it is unclear whether such variation moderates the emotional plight of youth with higher weight. By examining differences between schools, our goal is to gain insights into the contextual conditions that exacerbate (or alleviate) social-emotional difficulties associated with higher weight in early adolescence.

School-based Weight Norms

Research on weight-related peer victimization in adolescence is typically conducted in school settings by focusing on students’ individual experiences (e.g., Haines et al., 2008; Juvonen et al., 2017; Puhl & Luedicke, 2012; Puhl et al., 2017). Some of these studies examine the negative effects of overweight and/or obesity by taking into account the weight norms of the school. The conceptual assumption guiding such studies is that youth who deviate from what is considered typical or normative within their school are at higher risk for peer victimization and emotional distress. Studies testing such a person-by-environment mismatch (Wright, Giammarino, & Parad, 1986) typically operationalize school weight norms as the average body mass index (BMI) of students’ particular reference group (e.g., same-sex peers: Needham & Crosnoe, 2005, Sutter, Nishina, Witkow, & Bellmore, 2016; same-ethnic peers: Lanza, Echols, & Graham, 2013). Alternatively, the percentage of students with overweight or obesity in school is used to estimate weight norms (Eisenberg, McMorris, Gower, & Chatterjee, 2016). The findings are robust across studies: those with higher body weight than their local norms are at increased risk for peer victimization (Lanza et al., 2013; Sutter et al., 2016) and emotional distress (Eisenberg et al., 2016; Lanza et al., 2013; Needham & Crosnoe, 2005). Such studies highlight person-by-environment interactions and the negative consequences associated with lack of fit at school. However, the assumption guiding such studies is that in any school, deviation from the local norms increases the risk for negative social and emotional experiences. The question that remains is whether some school environments are risker than others for youth with higher body weight, independent of their personal experiences of peer victimization.

Schoolmates’ negative reactions (e.g., exclusion, taunting) toward those with higher body weight provide important insights about differences between schools. One way to capture variations across schools is to aggregate student self-reports of weight-related peer mistreatment. Lampard and colleagues (2014) found that across 20 middle and high schools, the average rates of weight-teasing ranged from 11% to 36%. Higher rates of weight-teasing were associated with lower self-esteem and greater body dissatisfaction among girls and greater depressive symptoms among boys. Such emotional difficulties did not vary as a function of students’ weight category (i.e., underweight, normal weight, overweight). The authors speculate that a greater overall prevalence of weight-teasing at school captures a “toxic environment,” affecting the internalization of socially valued body weight ideals. Although average rates of weight-related peer mistreatment may color the overall school climate (e.g., by increasing general appearance pressures), alternative approaches are needed to examine whether some school environments are emotionally riskier than others for students with higher weight. It is important to further investigate environmental effects on the emotional plight of those with higher weight because they are at heightened risk for a number of subsequent health problems (e.g., Simmonds, Llewellyn, Owen & Woolacott, 2016) and because negative social experiences predict continued weight problems (Puhl et al., 2017).

To be able to compare the social-emotional wellbeing of youth across schools, we rely on a novel school-level weight climate estimate. We presume higher body weight becomes more stigmatizing and emotionally consequential in schools where youth observe peers with higher weight being excluded and ridiculed. To test this idea, we rely on collectively shared knowledge about who is victimized (based on peer reports) as well as self-reported weight to compute the strength of the association between the two constructs at each school. A stronger association between body weight and victim reputation within a school captures a more negative weight climate, which is then expected to adversely affect those with heavier weight—independent of their own experiences of peer victimization. Such an approach examining the degree to which a particular individual characteristic (e.g., academic achievement, gender typicality) is associated with social sanctions (positive or negative) within a setting captures norm salience (Cialdini, Kallgren, & Reno, 1991). The method has been applied to study contextual moderator effects across classrooms (Dijkstra & Gest, 2015) and schools (Smith, Schacter, Enders & Juvonen, 2017). For example, Smith and colleagues (2017) showed that boys who do not perceive themselves typical of their gender felt more distressed in schools where gender atypicality was more strongly related to perceived peer mistreatment. These contextual effects were documented over and above boys’ individual reports of ridicule and exclusion.

Although both boys and girls experience weight-based peer mistreatment, the degree to which their weight is negatively sanctioned by peers or the effects of such mistreatment may vary by sex. We presume that girls’ body weight is especially likely to be policed by peers because of the persistent thin-idealization of females (Thompson & Stice, 2001). Whether girls with higher weight are also particularly sensitive to school-based weight-policing is less clear. Further insights about unique weight-policing dynamics for girls and boys are important to investigate.

Current Study

Focusing on early adolescence – a time when youth are particularly reactive to negative peer treatment (Blakemore & Mills, 2014) – we examine the effects of weight climate on adolescents’ social-emotional difficulties in middle school. As mentioned earlier, the current study relies on an indirect measure of school weight climate. We assess weight climate by relying on two independently assessed variables: collective knowledge of who is victimized and the targets’ self-reports of their body weight. Specifically, we assess how strongly self-reported body weight (adjusted for height and normed based on sex and age) is associated with a victim reputation within each school. A stronger positive association between the two variables suggests that youth with higher weight are more targeted-- or that weight appears to be “policed” by peers in that school. Thus, our weight climate estimate captures what might be described as weight-policing. As described above, the school-level estimates for weight-policing (i.e., how strongly weight predicts victim reputation within a school) were obtained separately for girls and boys. We presumed that the strength of weight-policing may vary by sex across schools (i.e., some schools have a more negative weight climate toward girls than boys). Although the separate analyses do not allow statistical comparisons between girls and boys, we can nevertheless gain insights about unique dynamics for each sex.

Given the novel approach to assessing school weight climate, our first goal was to provide descriptive information about this contextual weight climate variable. In addition to examining the range of the weight-policing coefficients across schools separately for boys and girls, we also computed bivariate correlations between school-level weight-policing and the school average BMI scores (both sex-specific) across schools. We expected a negative correlation between the two constructs: stronger weight-policing should be related to lower school-average BMI (where high weight is less normative).

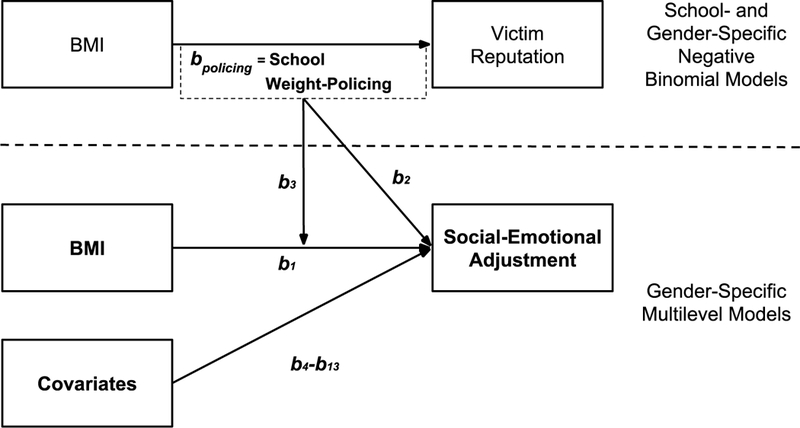

Our main goal was to test the contextual moderator effects of weight climate characterized by weight-policing. Given that a stronger association between BMI and victim reputation is presumed to reflect a more punitive climate toward those with higher weight, we expected youth with higher BMI to report greater social-emotional problems. Specifically, we hypothesized that schools with a stronger weight-policing climate amplify feelings of loneliness, sense of belonging, and low self-esteem among those with higher BMI. Accordingly, a school where BMI is unrelated to victim reputation suggests that the weight climate is not punitive (i.e., classmates with higher weight are not perceived to be targeted), and hence we expected that BMI is unrelated to social-emotional difficulties. Figure 1 provides the conceptual diagram of the tested associations. Assuming that the school-level weight-policing estimate (bpolicing) functions as a contextual moderator, we test a cross-level interaction between individual BMI and school-level weight-policing (indicated by ). In light of past findings regarding schoolwide rates of weight-teasing (Lampard et al., 2014), we also explored whether negative weight climate directly predicts greater loneliness, lower sense of belonging and self-esteem (indicated by in Figure 1). To make sure these effects do not merely reflect students’ personal experiences of peer mistreatment, we controlled for individual-level victim reputation as well as other possible predictors of social-emotional problems (e.g., perceived pubertal timing, ethnicity, SES).

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of associations between school-level (above the dashed line) weight-policing (peer victimization regressed on BMI within schools; bpolicing) and individual-level (below dashed line) BMI and other relevant covariates predicting social-emotional adjustment (b4-b13). Note. BMI=body mass index

The hypotheses were tested using a longitudinal design across three years of middle school (i.e., Grades 6–8). School weight climate assessments were based on data collected during the second year of middle school (i.e., seventh grade) when social norms are established. We then examined the potential main and moderator effects of seventh grade weight-climate on loneliness, sense of belonging, and self-esteem at eighth grade, while controlling for baseline (sixth grade when students started middle school) adjustment. To extend past studies on weight-related peer mistreatment examining emotional distress outcomes (e.g., depression), we focus on social indicators of well-being. Loneliness and lack of belonging capture sense of social dissatisfaction and lack of connection in school, whereas self-esteem is sensitive to peer approval (Harter, 1990).

Method

The current study relies on data from a larger, longitudinal study of youth recruited from 26 urban public schools in California that systematically varied in their ethnic composition. The current analytic sample (n=4,086, 51% girls) was ethnically diverse. Based on self-reported ethnicity in sixth grade, the sample was 30% Latino/a, 22% Caucasian/White, 14% East/Southeast Asian, 11% African American/Black, and 23% from other ethnic groups, including bi-racial and multi-ethnic. The proportion of students eligible for free or reduced lunch price (a proxy for school SES) ranged from 18% to 86% (M=47.6, SD=18.3) across the 26 schools. The average number of seventh grade students across the schools was 196 (SD=100).

Procedure

The study was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board and school districts. During sixth grade recruitment all students and families received informed consent and informational letters. Two $50 gift cards were raffled at each participating school for students who returned signed consent forms, whether or not they were given permission to participate. Parental consent rates averaged 81% and student assent rates averaged 83% across the schools. Only students who turned in signed parental consent and provided written assent participated.

All data collection was conducted in schools. Surveys were read aloud in each classroom by trained researchers, and students received $5 in the spring of sixth grade, and $10 in seventh and eighth grade for completion of the surveys.

Measures

Individual-level predictors.

Body mass index (BMI).

Body weight was estimated based on a BMI score using self-reported weight and height. Although objective measurements for weight and height are ideal, past research using a national sample of U.S. adolescents (AddHealth) has found self-report and objective measures of height and weight to be highly correlated (rheight=.94; rweight=.96; Vaughan & Halpern, 2010). Given that compared to BMI percentile scores, BMI z-scores are considered most suited for statistical analyses when modeling BMI as a continuous variable (Himes, 2009; Wang & Chen, 2012), z-scores were calculated using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2000 growth charts based on weight, height, sex and age. The z-scores represent individuals’ deviation or distance from the nationally normed average of their sex and age group. In the current sample, the mean of BMI z-scores was .21 (SD=.99) for girls, and .26 (SD= 1.10) for boys. Using conversion between nationally normed z-scores and percentiles scores, 21% of the girls and 26% of the boys in our sample were considered overweight or obese (within 85th-99th percentiles).

Peer victimization.

Using an unlimited nomination procedure, peers wrote down the names of classmates who were “picked on” in seventh grade. For each participant, the number of nominations received was totaled, with higher numbers indicating a stronger victim reputation. Typical of victim nominations, the means were low and standard deviations high (Mgirls=.39, SDgirls=1.18 and Mboys=.60, SDboys= 2.04). The number of victim nominations were used to compute weight-policing within each school (see below).

Control variables.

Several individual-level control variables known to predict social-emotional adjustment in early adolescence were used in the analyses. Students reported their sex and ethnicity in the sixth grade. Parent education was used as a proxy for student socioeconomic status. The parent/guardian who completed informed consent indicated his/her highest level of education on a 6-point scale (1= elementary/junior high school to 6= graduate degree) in the beginning of the study. Additionally, participants rated their perceived pubertal timing compared to their same-sex and same-aged peers: “Do you think you are developing (looking like a woman/man) faster or slower than most girls/boys your age?” (Dubas, Graber, & Petersen, 1991), on a 5-point scale, with higher values indicating earlier maturation (M=3.16, SD=.98).

School-level predictors.

Two indicators were used to assess characteristics of the school environment at seventh grade: weight-policing to indicate school weight climate and average BMI to capture relevant norms. Each were assessed separately for girls and boys.

Weight-policing.

As mentioned earlier, to capture weight climate characterized by weight-policing, we relied on BMI z-scores (based on self-reported weight, height and age) as well as peer nominations of victim reputation at each school. We used the sex specific BMI z-scores to predict a victim reputation separately for boys and girls at seventh grade. Because most youth do not receive any victimization nominations (i.e., do not have a reputation as a victim), the majority of nominations go to a relatively small proportion of students (means close to zero). Due to the resulting large positive skew typical of nomination patterns, the peer victimization variable is overdispersed (i.e., standard deviation is larger than the mean; Gazelle, Faldowski & Peter, 2014). As such, the highest values are greater than what would be predicted by a Poisson distribution, which uses a common parameter for the mean and variance. To accommodate the low modal score and long tail, we therefore used negative binomial regression to estimate the slope of BMI on peer victimization (Hilbe, 2011). Estimates of the negative binomial regression slope were computed separately for boys and girls at each school. Higher positive slope values indicate that BMI predicts victimization more strongly. Given that weight-policing captures the strength of the association between BMI and victim reputation, we refer to it in relative terms (e.g., stronger vs. weaker), but use the terms high, average and low weight-policing when conducting follow-up analyses of moderation effects (i.e., simple slopes).

School Average BMI.

To be able to take into account the normative (i.e., average) body weight of students in each school, we computed school-specific BMI averages for boys and girls. Individual sex-normed BMI z-scores (based on national standards) were summed and divided by the number of boys and girls in each school. The range of schoolwide BMI z-scores ranged from −0.27 to 1.32 (M=.28, SD=.22) for boys, and −0.24 to 0.92 (M=.24, SD=.24) for girls.

Social-emotional adjustment outcomes.

Three indicators of social-emotional adjustment outcomes were measured: loneliness, school belonging, and self-esteem. Each indicator was assessed during sixth grade (baseline) as well as at eighth grade.

Loneliness.

Five items from a Children’s Loneliness scale (Asher & Wheeler, 1985) were used to assess feelings of loneliness at school. Students responded to how alone they felt (e.g., “I have nobody to talk to”) at sixth and eighth grade. The responses (1=always true to 5=not true at all) were averaged so that higher scores indicated greater loneliness (α6th grade=.91; α8th grade=.92).

School Belonging.

A 6-item scale adapted from the school climate subscale of the Effective School Battery (ESB; Gottfredson, 1986) was used to assess the degree to which students feel that they belong at their school (e.g., “I feel like I’m a part of this school”) at sixth and eighth grade. Ratings ranged from 1 (for sure yes!) to 5 (no way!) and were reverse coded, with higher mean values indicating greater feelings of school belonging (α6th grade=.80; α8th grade=.85).

Self-Esteem.

General self-esteem was measured using four items of the Self-Perception Profile scale (Harter, 1982). For each item, students read two statements separated by the word “but” and were asked to choose one of these options (e.g., some kids are often unhappy with themselves, but other kids are pretty pleased with themselves). After selecting one statement, students rated if it was “really true” or “sort of true,” such that each item was rated on a 4-point scale. All four items were averaged (α6th grade=.75; α8th grade=.88), such that higher values indicate higher self-esteem.

Missing Data

The analytic sample (n=4,086) represents 80% of the overall seventh grade sample of 5,104 with necessary data for the current study: 2,101 girls and 1,985 boys. Of the analytic sample, 13% were missing data needed to compute BMI z-scores. Of the girls, 8% did not report their weight and 4% were missing height data, while 6% of boys did not report their weight and 5% were missing height. These rates are lower than in other studies that rely on self-reported weight and height (Himes, 2009). In addition, 2% of reports were identified as biologically implausible based on the World Health Organization’s recommended exclusion ranges (height-for-age, weight-for-age, or BMI-for-age) and were excluded from the analyses (CDC, 2015; WHO, 1995). Participants missing perceived pubertal timing (8% girls, 7% boys) were also excluded from the current analyses. Due to the sensitive nature of the weight and pubertal development questions, it cannot be presumed that these data were missing at random (see Himes & Faricy, 2001). All other data was presumed to be missing at random. Self-reports of loneliness and sense of belonging were part of a planned missing design (i.e., each measure completed by a random 2/3 of the sample; Graham, Taylor, Olchowski & Cumsille, 2006).

Multilevel Analysis Strategy

To test the main contextual moderator hypotheses, the data were analyzed in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) using a standard multilevel linear model to account for students nested within 26 middle schools (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). In sex-specific analyses, we took into account ethnicity (four dummy coded variables with Latinos, the largest ethnic group, as the reference group), SES, self-report of relative pubertal timing, individual-level victim reputation, baseline levels of each social-emotional adjustment index, as well as school sex-specific BMI average. A cross-level interaction term between BMI and weight-policing was included to test our main moderator hypotheses (i.e., the association between BMI and adjustment varies as a function of within-school weight-policing). Following recommendations for models including cross-level interactions (Enders, 2013), all individual-level predictors were grand-mean centered (sex-specific) to produce individual-level (i.e., level-1) coefficients that control for school-level (level-2) effects and vice versa. For statistically significantly interactions, tests of simple slopes were conducted to compare the adjustment of youth at schools one standard deviation below, at, and one standard deviation above the mean of weight-policing. The equation below depicts the prototype for the final model tested, wherein each indicator of social-emotional adjustment () was examined as a function of student body mass (), within-school weight-policing (), their cross-level interaction , and the aforementioned set of individual and school-level covariates (four of which represent dummy coded ethnic comparisons).

All models included a random intercept, and for each outcome we first tested an intercept-only model to determine the intraclass correlation, or the degree of similarity between individuals due to shared cluster membership at eighth grade (Hox, 2010). Although there were relatively small between-school differences in each dependent variable (ICC range: .01-.03), we nevertheless relied on multilevel modeling to account for the nested data and examine school-level effects (i.e., schoolwide BMI and weight-policing).

Results

The results are divided into two main sections. First, we examine how weight-policing relates to schoolwide BMI for girls and boys across the 26 schools. Second, we present the multilevel regression models examining whether the association between seventh grade BMI and eighth grade social-emotional adjustment outcomes is moderated by weight-policing. We present the main findings for girls followed by those for boys.

Weight-policing and Schoolwide BMI Norms

We computed weight-policing for girls and boys in each of our 26 schools (see Figure 1) by regressing the nominations received for victim reputation on BMI scores. For the girls, the school-level weight-policing values ranged from b = −0.49 to 1.74 (M=0.17 SD=0.49), while for the boys they ranged from b = −0.73 to 1.15 (M=0.01 SD=0.39). A weight-policing value of b = 1 means that, for one-unit increase in z-scored BMI, the difference in the logs of expected counts (number of victim nominations) would be expected to increase by one unit. Thus, the positive values of weight-policing indicate higher BMI predicts stronger victim reputation. To examine the association between weight-policing and BMI norms (i.e., sex-specific BMI average in each school), bivariate correlations were computed separately for the girls and boys cross the 26 schools. As expected, the scores were negatively related, such that stronger weight-policing was associated with lower school average BMI (possibly reflecting fewer students with overweight or obesity). The negative correlation was significant only for the girls, r= −.40, p=.04 (r boys= −.17, p=.40). To examine the role of weight-policing over and above the school-specific weight norms, we control for sex-specific school BMI averages in the main analyses.

Weight-policing: Girls

Correlations for seventh grade BMI and peer victimization as well as eighth grade social-emotional adjustment outcomes are presented in Table 1. To obtain estimates of purely within-school associations, variables were centered within schools (i.e., group-mean centered) prior to calculating the correlations. The bivariate coefficients for girls are presented in the upper diagonal of Table 1. With the exception of the intercorrelations among social-emotional adjustment indicators, the coefficients were small in magnitude.

Table 1.

Correlations among Primary Individual-Level Predictors and Social-Emotional Adjustment Outcomes.

| Variable | Victimization | BMI | Loneliness | Belongingness | Self-Esteem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7th Grade Victim reputation | --- | −.08*** | −.08** | −.04* | −.02 |

| 7th Grade BMI | −.05* | --- | −.01 | .01 | .04 |

| 8th Grade Loneliness | −.08** | −.04*** | --- | −.44*** | −.43*** |

| 8th Grade Belongingness | −.06** | −.05* | −.29*** | --- | .40*** |

| 8th Grade Self-Esteem | −.08*** | −.01*** | −.44*** | .32*** | --- |

Note. Values for boys are below the diagonal and values for girls are above the diagonal. All variables were group-mean centered to reflect within-school associations between the individual level variables.

BMI=body mass index

p<.05.

p<.01.

p < .001.

Table 2 shows the coefficients and standard errors from the multilevel models for girls. Whereas group-mean centering was used for the descriptive correlations, in the main analyses all individual-level variables were grand-mean centered (Enders, 2013). The individual-level predictors showed few statistically significant effects when the school-level moderator effects were tested. As shown in Table 1, only the baseline (i.e., sixth grade) assessments of loneliness, school belonging, and self-esteem were consistently related to the same outcomes by eighth grade. The hypothesized BMI by weight-policing interaction was significant for loneliness as well as self-esteem, and marginal for sense of belonging (bottom row of Table 2). To be able to interpret the cross-level interactions, follow-up analyses were conducted by examining simple slopes between BMI and the social-emotional adjustment outcomes at low (one SD below average), average, and high (one SD above average) levels of weight-policing.

Table 2.

Effects of Sixth Grade Controls and Seventh Grade Weight Variables on Eighth Grade Adjustment Outcomes among Girls.

| 8th grade outcomes (unstandardized coefficients and standard errors) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | School Belonging | Self-Esteem | ||||

| Predictors | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE |

| Individual level | ||||||

| Intercept | −1.80*** | .06 | −3.56*** | .04 | −2.97*** | .05 |

| African-American/Black | −0.13*** | .09 | −0.02 | .06 | −0.35*** | .06 |

| East/Southeast Asian | −0.19**** | .07 | −0.04 | .05 | −0.05*** | .06 |

| White/Caucasian | −0.04*** | .06 | −0.05 | .05 | −0.07 | .08 |

| Other | −0.09*** | .09 | −0.01 | .05 | −0.05 | .06 |

| SES | −0.00*** | .02 | −0.00 | .02 | −0.03* | .02 |

| Perceived Pubertal Timing | −0.01*** | .03 | −0.00*** | .02 | −0.05* | .02 |

| Baseline Adjustment | −0.40*** | .07 | −0.41*** | .03 | −0.34*** | .02 |

| Victimization | −0.03 | .03 | −0.04 | .02 | −0.01 | .03 |

| BMI | −0.06**** | .03 | −0.00*** | .02 | −0.03*** | .02 |

| School level | ||||||

| BMI Average | −0.23 | .12 | −0.06* | .12 | −0.08 | .13 |

| Weight-policing | −0.08 | .08 | −0.05 | .05 | −0.02 | .06 |

| Cross-level interaction | ||||||

| BMI X Weight-policing | 0.13* | .06 | −0.07** | .04 | −0.13***** | .03 |

Note. SE=standard error; BMI=body mass index; SES=socioeconomic status

Ethnicity reference group=Latino.

***p<.001,

**p<.01,

*p<.05.

Loneliness.

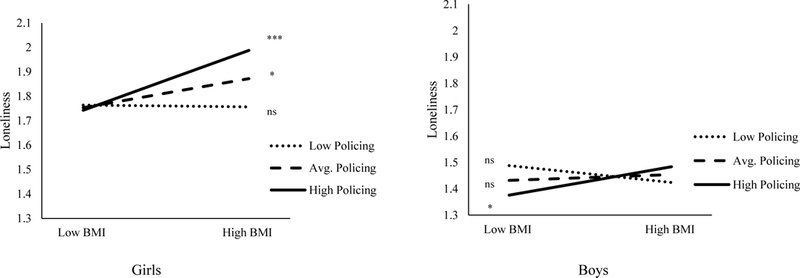

The significant cross-level interaction between BMI and weight-policing (b=.13, SE=.06, p=.034) suggests that, for girls, the association between BMI and loneliness varies across schools depending on weight-policing. Analyses of the simple slopes (see Figure 2) show that higher BMI is related to greater loneliness at schools with average (b=.06, SE=.03, p=.020) and high (i.e., one SD above mean) weight-policing (b=.11, SE=.04, p=.002), whereas BMI is unrelated to loneliness at schools with low (i.e., one SD below mean) weight-policing (b=.01, SE=.03, p=.882). Thus, girls with higher body weight feel lonelier only in schools where higher weight is policed by peers (i.e., where higher BMI is associated with a stronger victim reputation). There was also a lower-order (conditional) effect of BMI on loneliness, indicating that higher BMI predicted greater sense of loneliness for students in schools with average levels of weight-policing (i.e., when weight-policing=0). Also, ethnic differences in loneliness were obtained showing that Asian girls reported higher loneliness compared to Latinas.

Figure 2.

The moderating role of weight-policing on the association between BMI and loneliness for girls (left panel) and boys (right panel). The values presented reflect loneliness scores for individuals at low (one SD below the sample mean) and high (one SD above the sample mean) BMI, in schools with average, low or high weight-policing (± one SD above or below the mean), and at the mean on all other variables. Note. BMI=body mass index ***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05.

School belonging.

The interaction capturing weight-policing was only marginally significant (b= −.07, SE=.04, p=.065) for school belonging.

Self-esteem.

The analyses yielded a significant cross-level interaction between BMI and weight-policing (b= −.13, SE=.03, p<.001) for girls’ self-esteem. Tests of simple slopes revealed that at schools with higher weight-policing (i.e., +1 SD), higher BMI was associated with lower self-esteem (b= −.08, SE=.02, p=.001). At schools with average (b= −.03, SE=.02, p=.203) and low (i.e., −1 SD; b=.02, SE=.03, p=.370) weight-policing, there was no association between BMI and self-esteem. That is, higher BMI predicted decreased self-esteem only among girls attending schools where BMI is more strongly (positively) linked with a victim reputation. In addition, African American girls reported higher self-esteem than Latinas.

In sum, weight-policing at seventh grade predicted the subsequent social-emotional difficulties of girls with higher weight. These contextual moderator effects were obtained while controlling for ethnicity, SES, pubertal timing, personal victim reputations, social-emotional adjustment in sixth grade, and the average BMI of girls in each school.

Weight-policing: Boys

Correlations for boys’ individual seventh grade BMI and peer victimization and eighth grade social-emotional adjustment outcomes are presented in lower diagonal of Table 1. The pattern of correlations was similar to those of girls described above. Table 3 shows the coefficients and standard errors from the multilevel models for boys. The findings varied across the three social-emotional indicators, except for consistent baseline effects. Although school-level predictors were associated for sense of belonging, our contextual moderator hypothesis was supported only for loneliness. In the absence of a significant cross-level interaction, the interaction term was removed from the model to predict sense of belonging and self-esteem.

Table 3.

Effects of Sixth Grade Controls and Seventh Grade Weight Variables on Eighth Grade Adjustment Outcomes among Boys.

| 8th grade outcomes (unstandardized coefficients and standard errors) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | School Belonging | Self-Esteem | ||||

| Predictors | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE |

| Individual level | ||||||

| Intercept | −1.44**** | .05 | 3.61*** | .04 | −3.49*** | .04 |

| African-American/Black | −0.12***** | .07 | −0.13**** | .06 | −0.04*** | .07 |

| East/Southeast Asian | −0.44**** | .07 | −0.07*** | .08 | −0.26*** | .06 |

| White/Caucasian | −0.21****** | .07 | −0.11** | .06 | −0.04***** | .03 |

| Other | −0.18****** | .06 | −0.06** | .06 | −0.02***** | .05 |

| SES | −0.02**** | .02 | −0.01*** | .01 | −0.01*** | .01 |

| Perceived Pubertal Timing | −0.02**** | .02 | −0.02*** | .02 | −0.04***** | .02 |

| Baseline Adjustment | −0.37**** | .04 | −0.40*** | .03 | −0.32*** | .03 |

| Victimization | −0.02 | .02 | −0.03 | .02 | −0.04* | .02 |

| BMI | −0.01**** | .01 | −0.00*** | .02 | −0.01*** | .02 |

| School level | ||||||

| BMI Average | −0.02**** | .16 | −0.31** | .10 | −0.07 | .07 |

| Weight-policing | −0.06**** | .06 | −0.14***** | .05 | −0.02*** | .05 |

| Cross-level interaction | ||||||

| BMI X Weight-policing | −0.10***** | .05 | −0.00 | .04 | −0.02* | .03 |

Note. SE=standard error; BMI=body mass index; SES=socioeconomic status

Ethnicity reference group=Latino.

***p<.001,

**p<.01,

*p<.05.

Loneliness.

Consistent with our contextual moderation hypothesis, a significant BMI by weight-policing interaction (b=.10, SE=.05, p=.037) was obtained. Tests of simple slopes revealed that at schools with higher weight-policing, boys with higher BMI reported greater sense of loneliness (b=.04, SE=.02, p=.038), while BMI was a non-significant predictor of loneliness at schools with average (b=.01, SE=.01, p=.655) and low (i.e., one SD below) weight-policing (b= −.03, SE=.02, p=.192; see Figure 2). Also, ethnic differences in loneliness were obtained showing that compared to Latinos, all other ethnic groups (with the exception of African-American students) reported higher loneliness.

School belonging.

The cross-level interaction between BMI and weight-policing was non-significant for school belonging (b=.00, SE=.04, p=.929). When the interaction term was removed from the model, the coefficients for school-level BMI average and weight-policing remained similar to the conditional effects reported in Table 3. Specifically, boys attending schools with higher average BMI reported lower school belonging (b= −.31, SE=.10, p=.001). Also, boys reported lower school belonging in schools with stronger weight policing, regardless of their own weight (b= −.14, SE=.05, p=.003). Compared to Latinos, African American boys had higher sense of school belonging, while White boys reported a lower sense of belonging.

Self-esteem.

The interaction between weight-policing and BMI was non-significant for self-esteem (b= −.02, SE=.03, p=.553). When the interaction term was removed from the model, earlier pubertal timing (b=.04, SE=.02, p=.032) and victim reputation (b= −.04, SE=.02, p=.021) predicted eighth grade self-esteem, over and above baseline self-esteem and demographic covariates. Compared to Latinos, Asian boys had lower self-esteem.

Taken together, the results suggest that for boys, weight-policing only intensified feelings of loneliness among those with higher body weight. However, weight-policing at seventh grade was negatively associated with sense of belonging in school at eighth grade, regardless of boys’ weight. Boys’ self-esteem at eighth grade, in turn, was negatively associated with their seventh grade victim reputation.

Discussion

The social costs of not fitting in with body ideals and norms can be substantial in adolescence. Studies examining person-by-environment mismatch show that youth with higher weight than the average weight of their local reference group are at heightened risk for peer victimization (Lanza, et al., 2013; Needham & Crosnoe, 2005; Sutter, et al., 2016 ). Moreover, weight-related peer mistreatment in early adolescence predicts subsequent emotional problems (e.g., Haines et al., 2008; Juvonen et al., 2017) and long-term health problems over and above initial weight (Puhl et al., 2017). Extending past research, the current study sheds light on the moderating effects of school weight climate. Although weight climate can be potentially captured in various ways, we chose to rely on students’ observations of who is mistreated in school, presuming that in schools where youth observe peers with higher weight being excluded and ridiculed, higher BMI is more emotionally consequential. As far as we know, our findings are the first to suggest that the emotional meaning of body weight varies across middle schools-- independent of the local weight norms and personal experiences of peer mistreatment.

The methodological contribution of the current study pertains to our novel approach of capturing negative school weight climate. The approach was based on the idea that we can capitalize on shared understanding about who is targeted by peers. When students see individuals with higher weight ridiculed and excluded, the negative sanctions then convey what is not accepted or tolerated (Juvonen & Galvan, 2008). By examining how strongly higher BMI predicts victim reputation for girls and boys in each school, we learned that there is indeed substantial variability in the sex-specific weight-policing estimates across schools. Moreover, weight climate characterized by stronger weight-policing was associated with subsequent social-emotional difficulties among those with higher weight, especially among girls.

Consistent with our hypotheses, girls with higher BMI at seventh grade felt lonelier and had lower self-esteem at eighth grade in schools where body weight increased the risk of being perceived as a victim. In contrast, there was no association between BMI and these social-emotional outcomes in schools where weight appeared not to be associated with peer mistreatment. The test of weight climate effects were rigorous: we controlled for earlier social-emotional adjustment, perceived pubertal timing, and victim reputations at seventh grade, in addition to ethnic and SES differences. Thus, loneliness and low self-esteem of girls with higher BMI clearly depend on the weight climate of their middle school.

For boys, we only found support for the contextual moderator effects of weight climate on loneliness. That is, boys with higher BMI were lonelier at schools with stronger weight-policing. The less robust contextual moderator effects of weight climate for boys (i.e., no such evidence for sense of belonging and self-esteem) can be partly interpreted in light of our descriptive findings. Across the 26 schools, the strength of school-level weight-policing did not vary by the school average BMI of boys as systematically as it did for girls. The lack of the association may have to do with the BMI measure. Although BMI adjusts weight relative to height, it is an imperfect weight indicator for boys, who typically have greater muscle mass than girls. Boys with higher BMI might not be at heightened risk for weight-policing if their BMI reflects their muscularity (see Jones, Vigfusdottir & Lee, 2004; Smolak & Stein, 2006). Hence, weight-policing in school may not affect the self-esteem and sense of belonging of boys with higher body weight if their BMI reflects high muscle mass. However, weight-policing of boys was related to their lower sense of belonging in school, regardless of their weight. This finding is consistent with research on the effects of higher average rates of weight teasing across middle and high schools (Lampard et al., 2014). We presume that such main effects may reflect greater general appearance pressures among boys.

Limitations and Future Research Needs

In spite of methodological strengths (e.g., reliance on multiple informants, longitudinal design, and ethnically diverse sample), the current study has shortcomings that should be addressed in further research. First of all, we relied on self-reported weight and height to calculate BMI. These self-reports included missing data and some invalid values, limiting the generalizability of the findings. It is therefore critical that the current findings are replicated with more complete objective weight and height data. Second, we used a general indicator of peer victimization that does not provide any insights about whether youth target others specifically because of their weight. That is, even when higher BMI is related to a stronger victim reputation within a school, it is possible that someone with higher BMI is ridiculed for other reasons besides their weight (e.g., because of the types of clothes they wear or how they walk or talk). Rather than referring to derogatory comments and other behaviors targeting body weight, we adopted the term weight-policing to capture the socially punitive aspect of the weight climate. However, information about the form or the type of weight-related mistreatment (e.g., name calling) would provide some further insights about the nature of weight-policing among girls versus boys. For example, differences in the types of comments that girls and boys receive about their body shape or size might be differentially hurtful. Also, we did not statistically compare girls and boys because of their different BMI norms. However, the differences in the overall results of girls and boys are consistent with research on body ideals. For example, research shows that weight ideals encountered in daily life by adult women are more rigid, narrow, and pervasive than those for men (Buote, Wilson, Strahan, Gazzola, & Papps, 2011). Although our findings regarding the social-emotional effects of weight-policing are consistent with prior research suggesting that adolescent girls are more sensitive to body ideals (Hargreaves & Tiggemann, 2004) and weight-based teasing than boys (Goldfield et al., 2010), explicit testing of sex differences is warranted in future investigations.

Although we relied on an ethnically diverse sample of middle school students, we could not test ethnic differences in weight-policing because of an insufficient number of boys and girls across different ethnic groups within our schools. That is, the analyses used to assess the strength of weight-policing needed to be based on groups of sufficient size to compute the regression slopes. To be able to gain insights about ethnic differences or the intersectionality of sex and ethnicity regarding weight stigma (Himmelstein, Puhl, & Quinn, 2017), qualitative methods may be most fruitful. Additionally, examination of friendship networks might provide important insights about the social-emotional plight of youth with higher weight. For example, it is possible that girls and boys with higher weight felt lonelier in schools with stronger weight-policing because they lack friends. Testing possible mediational mechanism, such as lack of friends, was beyond the scope of the current investigation, but should be further explored in subsequent research.

Implications

The conceptual frameworks guiding past studies on the social-emotional difficulties of youth with higher weight can yield some problematic implications. For example, it would be unwise to conclude that a teen with overweight is better off in schools where the weight norm (i.e., average weight) is high. Although students with overweight would better fit the local norms in such schools, the social contagion of overweight may exacerbate existing or future health problems (Christakis & Fowler, 2007). On the other hand, it may also be simplistic to presume that anti-bullying programs that decrease bullying can specifically improve the wellbeing of youth with higher weight. In schools with lower levels of peer victimization, those who are targeted blame themselves more (Schacter & Juvonen, 2015) and feel more socially anxious (Bellmore, Witkow, Graham & Juvonen, 2004). Thus, reductions in rates of peer mistreatment are not necessarily enough to help youth with higher weight.

What, then, are the implications of the current approach? We believe that our approach and findings imply that to improve the well-being (or reduce the social-emotional difficulties) of youth with higher weight, we need to focus on bias reduction. Curricula promoting weight acceptance and body shape diversity have been effective in improving peer acceptance and reducing teasing of students with overweight in elementary school (Irving, 2000). Although it might be possible to develop similar curricula for middle school students, there are also other ways to reduce bias. Some of the most effective prejudice reduction efforts based on contact theory (e.g., Pettrigrew, 1998) involve facilitating regular interaction, cooperation, and equal status across different groups. Teachers can promote such conditions through their classroom activities (e.g., by assigning students into groups rather than allowing students to form groups). Moreover, close friendships between youth of different body weight could be particularly powerful in facilitating optimal conditions for prejudice reduction: high frequency contact, equal status, and cooperation.

Final Conclusions

The current findings demonstrate the importance of studying the effects of school weight climate on young adolescents’ social well-being. That is, our weight-policing findings were especially robust for loneliness. Yet most prior research on weight, school-based weight norms, and weight-related mistreatment examine self-esteem and depression as the main indices of emotional distress. Feelings of loneliness are particularly important adjustment indicators because they are likely to capture social isolation associated with social marginalization. When youth with higher weight lack sense of social connection because they are concerned about peer mistreatment, they may be less likely to participate in class or join extracurricular activities in middle school. Indeed, youth with higher weight are least likely to take part in sports (De Bourdeaudhuij et al., 2005), possibly because of their larger body shape and size or the ridicule that their weight elicits. Encouragement of youth with higher body weight to join physical activities may only be successful in schools that are emotionally safe for them.

In sum, we believe that examining the ways in which weight (or other developmentally salient attributes) increase the risk of peer victimization provide us with new insights about which characteristics are targeted by peers—and as such, offer valuable insights about the climate or culture of the school. For example, while in some schools students maybe be particularly intolerant of boys who are not gender typical (Smith et al., 2017), in other schools it might be girls with higher weight that are ridiculed and excluded. Based on the current measurement approach, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of schools’ social climates without needing to rely on youth’s inferences about why they (or their peers) are victimized. Examination of nuanced social climates enable us to then understand why some schools are risker than others for particular students.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Dr. Sandra Graham (PI of the Project) and the members of the UCLA Middle School Diversity team for their contributions to collection of the data, and all school personnel and participants for their cooperation. We also appreciate the fee

Funding This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (Grant 1R01HD059882–01A2) and the National Science Foundation (No. 0921306). The second author (LL) received additional support from the University of California, Los Angeles Graduate Summer Research Mentorship Program, the third author (HS) from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowships under Grant No. DGE-1144087, and the fourth author (CE) from the Institute of Educational Sciences Award (R305D150056).

References

- Asher SR, & Wheeler VA (1985). Children’s loneliness: a comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 500–505. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.4.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmore A, Witkow MR, Graham S, & Juvonen J (2004). Beyond the individual: the impact of ethnic context and classroom behavioral norms on victims’ adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 40, 1159–1172. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, & Mills KL (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucchianeri MM, Eisenberg ME, Wall MM, Piran N, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2014). Multiple types of harassment: Associations with emotional well-being and unhealthy behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, 724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buote VM, Wilson AE, Strahan EJ, Gazzola SB, & Papps F (2011). Setting the bar: Divergent sociocultural norms for women’s and men’s ideal appearance in real-world contexts. Body Image, 8, 322–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). A SAS program for the 2000 CDC growth charts (ages 0 to <20) . Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm.

- Cialdini RB, Kallgren CA, & Reno RR (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 201–234.doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis NA, & Fowler JH (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. The New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lefevre J, Deforche B, Wijndaele K, Matton L, & Philippaerts R (2005). Physical activity and psychosocial correlates in normal weight and overweight 11 to 19 year olds. Obesity Research, 13, 1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijstra JK, & Gest SD (2015). Peer norm salience for academic achievement, prosocial behavior, and bullying: Implications for adolescent school experiences. The Journal of Early Adolescence , 35, 79–96. doi: 10.1177/0272431614524303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubas JS, Graber JA, & Petersen AC (1991). A longitudinal investigation of adolescents’ changing perceptions of pubertal timing. Developmental Psychology, 27, 580–586. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.4.580 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, McMorris BJ, Gower AL, & Chatterjee D (2016). Bullying victimization and emotional distress: Is there strength in numbers for vulnerable youth? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 86, 13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Haines J, & Wall M (2006). Weight-teasing and emotional well-being in adolescents: Longitudinal findings from Project EAT. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2013). Centering predictors and contextual effects In Scott MA, Simonoff JS, & Marx BD (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Faldowski RA, & Peter D (2015). Using peer sociometrics and behavioral nominations with young children In Saracho ON (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Early Childhood Education, Review of Research Methodologies (Vol. 1, pp. 27–70). Charlotte: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfield G, Moore C, Henderson K, Buchholz A, Obeid N & Flament M (2010). The relation between weight-based teasing and psychological adjustment in adolescents. Pediatric Child Health , 15, 283–288. doi: 10.1093/pch/15.5.283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson GD (1986). Using the effective school battery in school improvement and effective schools programs. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/63245700/138AF469B2958EB7CFD/1?acco untid=14512 [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Olchowski AE, & Cumsille PE (2006). Planned missing data designs in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 11, 323–343. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan P, & Robinson-O’Brien R (2008). Child versus parent report of parental influences on children’s weight-related attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33, 783–788. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves DA, & Tiggemann M (2004). Idealized media images and adolescent body image: “Comparing” boys and girls. Body Image, 1, 351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87–97. doi: 10.2307/1129640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1990). Self and identity development In Feldman SS & Elliott GR (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 352–387). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM (2011). Negative binomial regression. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Himes JH (2009). Challenges of accurately measuring and using BMI and other indicators of obesity in children. Pediatrics, 124, S3–S22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3586D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himes JH, & Faricy A (2001). Validity and reliability of self-reported stature and weight of US adolescents. American Journal of Human Biology, 13, 255–260. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, & Quinn DM (2017). Intersectionality: an understudied framework for addressing weight stigma American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 53, 421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, & Schoot R van de: (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Irving LM (2000). Promoting size acceptance in elementary school children: The EDAP puppet program. Eating Disorders, 8, 221–232. doi: 10.1080/10640260008251229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DC, Vigfusdottir TH, & Lee Y (2004). Body image and the appearance culture among adolescent girls and boys: an examination of friend conversations, peer criticism, appearance magazines, and the internalization of appearance ideals. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 323–339. doi: 10.1177/0743558403258847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J & Galvan A (2008). Peer influence in involuntary social groups: Lessons from research on bullying Peer Influence Processes Among Youth (pp.225–244). Prinstein Mitchell J. & Dodge Kenneth A., Eds. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Lessard LM, Schacter HL, & Suchilt L (2017). Emotional implications of weight stigma across middle school: the role of weight-based peer discrimination. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46, 150–158. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1188703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampard AM, MacLehose RF, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, & Davison KK (2014). Weight-related teasing in the school environment: Associations with psychosocial health and weight control practices among adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1770–1780. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0086-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza HI, Echols L, & Graham S (2013). Deviating from the norm: Body mass index (BMI) differences and psychosocial adjustment among early adolescent girls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38, 376–386. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL, & Crosnoe R (2005). Overweight status and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36, 48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, & Luedicke J (2012). Weight-based victimization among adolescents in the school setting: Emotional reactions and coping behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 27–40. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9713-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Luedicke J, & Heuer C (2011). Weight-based victimization toward overweight adolescents: Observations and reactions of peers. Journal of School Health, 81, 696–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00646.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Wall MM, Chen C, Bryn Austin S, Eisenberg ME, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2017). Experiences of weight teasing in adolescence and weight-related outcomes in adulthood: a 15-year longitudinal study. Preventive Medicine, 100, 173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Schacter HL, & Juvonen J (2015). The effects of school-level victimization on self-blame: Evidence for contextualized social cognitions. Developmental Psychology, 51, 841–847. doi: 10.1037/dev0000016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, & Woolacott N (2016). Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 17, 95–107. doi: 10.1111/obr.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Schacter HL, Enders CK, & Juvonen J (2017). Effects of school-level gender norm salience on adolescent adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. Online first. [Google Scholar]

- Smolak L, & Stein JA (2006). The relationship of drive for muscularity to sociocultural factors, self-esteem, physical attributes gender role, and social comparison in middle school boys. Body Image, 3, 121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter C, Nishina A, Witkow MR, & Bellmore A (2016). Associations between adolescents’ weight and maladjustment differ with deviation from weight norms in social contexts. Journal of School Health, 86, 638–644. doi: 10.1111/josh.12417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JK, & Stice E (2001). Thin-ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 181–183. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Geel M, Vedder P & Tanilon J (2014). Are overweight and obese youths more often bullied by their peers? A meta-analysis on the correlation between weight status and bullying. International Journal of Obesity , 38, 1263–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CA, & Halpern CT (2010). Gender differences in depressive symptoms during adolescence: the contributions of weight-related concerns and behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence , 20, 389–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00646.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, & Chen H (2012). Use of percentiles and z-scores in anthropometry In Preedy VR (Ed.), Handbook of Anthropometry (pp. 29–48). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1995). Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. WHO Technical Report Series: 854. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland: Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/37003/1/WHO_TRS_854.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JC, Giammarino M, & Parad HW (1986). Social status in small groups: Individual–group similarity and the social “misfit.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 523–536. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]