Abstract

Perovskite oxide surfaces catalyze oxygen exchange reactions that are crucial for fuel cells, electrolyzers, and thermochemical fuel synthesis. Here, by bridging the gap between surface analysis with atomic resolution and oxygen exchange kinetics measurements, we demonstrate how the exact surface atomic structure can determine the reactivity for oxygen exchange reactions on a model perovskite oxide. Two precisely controlled surface reconstructions with (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) symmetry on 0.5 wt.% Nb-doped SrTiO3(110) were subjected to isotopically labeled oxygen exchange at 450 °C. The oxygen incorporation rate is three times higher on the (4 × 1) surface phase compared to the (2 × 5). Common models of surface reactivity based on the availability of oxygen vacancies or on the ease of electron transfer cannot account for this difference. We propose a structure-driven oxygen exchange mechanism, relying on the flexibility of the surface coordination polyhedra that transform upon dissociation of oxygen molecules.

The availability of surface oxygen vacancies or electrons is often viewed as the defining factor for the reactivity of perovskite oxides. Two precisely controlled surfaces on SrTiO3(110) show strikingly different O exchange kinetics, which the authors ascribe to the flexibility of the surface polyhedra.

Introduction

Oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution often limit the efficiency of energy conversion technologies including fuel cells, electrolyzers, and photo-/electrochemical water splitting. Perovskite oxides (of unit formula ABO3) are widely used and studied materials for enabling these reactions at elevated temperatures. They are used in solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC) for electricity production1–3, in the synthesis of fuels by electrolysis of water or steam4 and in the thermochemical splitting of water and CO25. The reactivity on these perovskite oxides is often interpreted in terms of the availability of surface oxygen vacancies (VO)6–10 or electrons11–15 and the position of the oxygen 2p band center16. Undoubtedly, the atomic-scale details of surface structures ought to also be critical in determining the speed of the oxygen reduction and evolution reactions (ORR and OER), which is measured either electrochemically or by incorporation of isotopically labeled 18O3,17,18. Intriguingly, none of these canonical reactivity models consider the role of the precise surface atomic structure. The important question is how the atomic configuration at the surface affects the ORR/OER mechanisms at the molecular level, either via these reactivity-determining factors or directly via the structure itself. For example, it was shown that La0.7Sr0.3MnO319, La2NiO420, SrRuO321, and SrTiO322 possess different oxygen exchange and water splitting kinetics depending on the surface crystallographic orientation, but the actual atomic structure of the surfaces was not resolved. Reliable computational modeling of surface reactivity at the first-principles level necessarily requires the geometric positions of the surface atoms as an input, which, in turn, need to be confirmed by experiments.

Knowing the geometric arrangement of the surface atoms under reaction conditions has been highly difficult, however. There are scarcely any methods that can determine the surface structure and measure the reactivity to oxygen exchange without perturbing the surface structure under reaction conditions of elevated temperatures and realistic reactant pressures. In addition, many of the Sr-doped perovskite oxides that are used in electrocatalytic or thermochemical reactions [e.g., La0.8Sr0.2MnO3 (LSM)17, La0.6Sr0.4CoO3 (LSC)23, La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3 (LSCF)24, and Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3 (BSCF)25] segregate out Sr-rich-insulating phases26–30, and it is impossible to resolve these highly heterogeneous surface regions with atomic resolution.

In the present study, we marry physical surface science studies with kinetic oxygen exchange measurements on precisely controlled atomic structures and demonstrate how these affect oxygen exchange mechanisms and kinetics. We take SrTiO3 as a prototypical model perovskite oxide, primarily due to our ability to prepare SrTiO3(110) with two distinctly different and controllable surface phases with solved structures31. Another advantage of this system is the fact that Sr segregation is suppressed if single-crystal SrTiO3 surfaces are stabilized by a reconstruction32. We use 0.5 wt.% Nb-doped samples that are sufficiently conductive for evaluating the atomic structure with STM. The relevant bulk VO concentration expected under the experimental conditions of this work is extremely low, as discussed later. The bulk oxygen transport is thus strongly suppressed, but the surface oxygen exchange reaction can still be probed in isotope exchange experiments. By quantifying the 18O exchange for these two reconstructions, while keeping all other experimental parameters exactly constant, we find that their reactivity differs by a factor of three. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations on these precisely resolved surface structures reveal that this difference is neither related to oxygen vacancies nor to variations in work function or surface potential that would affect the availability of electrons on this material. Instead, the structural details determine the interaction with the molecular oxygen. Our results reveal the polyhedral flexibility up to the ideal coordination limit as an important and previously unexplored factor that can govern the reactivity to oxygen exchange reactions on perovskite oxides surfaces.

Results

Characterization of SrTiO3(110) surface reconstructions

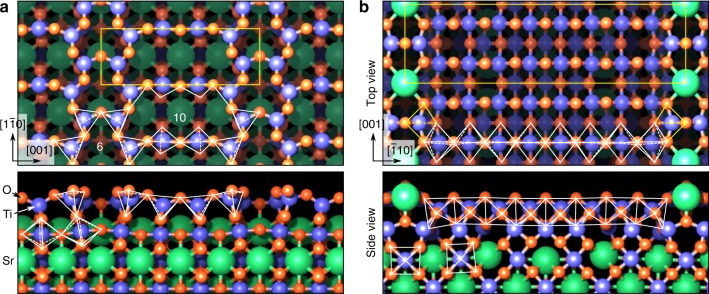

Figure 1 shows the (4 × 1)- and (2 × 5)-reconstructed surfaces of SrTiO3(110), prepared as described in the “Methods” section. In both cases, a layer of TiOx polyhedra (x = 4, 5, 6 as defined below) sits on a (SrTiO)4+ plane, which is only marginally distorted from its bulk structure. These top titania overlayers have distinctly different structural properties, however. The (4 × 1) surface (Fig. 1a) consists of a porous network of corner-sharing tetrahedrally coordinated TiO4 units, arranged into six- and ten-membered rings (highlighted by tetrahedra in Fig. 1a). The SrTiO3(110)-(2 × 5)-reconstructed surface (Fig. 1b) consists, instead, of a bilayer of octahedrally coordinated Ti atoms. The subsurface layer consists of edge- and corner-sharing octahedra. The topmost surface layer hosts 16 edge-sharing TiO6 octahedra, and two TiO5 units, in which the apical oxygen atom is missing. Finally, fivefold-coordinated Sr atoms alternate with the TiO5 units, with a twofold periodicity along [001]. Similar to other surfaces of SrTiO333, these reconstructions on n-type SrTiO3(110) form due to thermodynamic conditions, and in this case mainly due to the minimization of surface energy31 as a function of chemical potential of Ti and Sr, and of strain energy34. The same reconstructions exist on undoped or p-type-doped SrTiO3(110) surfaces.

Fig. 1.

Surface structure models on SrTiO3(110). a SrTiO3(110)–(4 × 1), and b SrTiO3(110)–(2 × 5) surface reconstructions31. Top view (top) and cross-section view (bottom). Notice that the structures are displayed with a 90° in-plane rotation. Ti, Sr, and O atoms are drawn as blue, green, and red spheres, respectively. The Ti coordination polyhedra are represented by white lines. While the (4 × 1) surface (a) is composed of ten- and six-membered rings of corner-sharing tetrahedra, the (2 × 5) surface (b) consists of a bilayer of octahedra

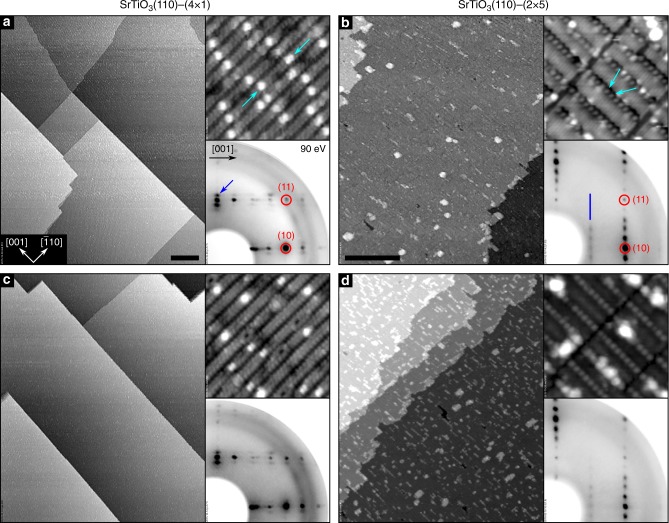

Representative scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) images and low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) patterns from these two surfaces are shown in Fig. 2. The six- and ten-membered rings of TiO4 on the (4 × 1) surface give rise to rows running along the direction, separated by darker trenches along [001], as seen in the high-resolution STM images. Bright, isolated features (light-blue arrows in the top-right inset of Fig. 2a) have been identified as single Sr adatoms, preferentially occupying a surface domain boundary34. In wide-area STM images, (4 × 1)-reconstructed SrTiO3(110) surfaces exhibit large (20–300 nm), atomically flat terraces, separated by steps with single (275 pm) or multiple unit-cell heights, preferentially running along low-index directions (see main panel of Fig. 2a). On the (2 × 5) surface, Sr atoms close to the TiO5 units are usually predominantly visible in high-resolution STM (indicated by the light-blue arrows in Fig. 2b). These Sr atoms are imaged as protrusions centered on shallow dark trenches, while the surface TiO6 octahedra are responsible for the bright appearance of the stripes extending along the [001] direction31. The inset shows the characteristic LEED pattern with (2 × 5) periodicity. In large-area STM images, the (2 × 5)-reconstructed SrTiO3(110) surface shows flat terraces with a morphology similar to the (4 × 1) reconstruction.

Fig. 2.

Surface structures of SrTiO3(110), and their stability upon treatment in oxygen atmosphere. Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) images (main panels: a, c 410 × 500 nm2; b, d 190 × 230 nm2; scale bars represent a length of 50 nm; top-right insets: 15 × 15 nm2), and LEED patterns of the SrTiO3(110)–(4 × 1) (a, c) and –(2 × 5) (b, d) surfaces. The as-prepared (a, b) and O2-annealed (c, d) samples appear similar; the slightly different contrast observed in the high-resolution STM images of b and d are related to variations of the tip termination

After annealing these samples in oxygen atmosphere prior to the 18O exchange experiment (450 °C, 0.1 mbar O2, for 5 h), the atomic-scale structure appears essentially unchanged for both surfaces, seen from comparing Fig. 2a, b with Fig. 2c, d. The (4 × 1)-reconstructed surface (Fig. 2c) retains the atomically flat, large-scale morphology of the pristine sample. On the SrTiO3(110)-(2 × 5) surface (Fig. 2d), the morphology is also largely preserved, along with a slight increase of the fraction covered by rectangular islands. It is known that even small changes in the surface Ti/Sr ratio would switch the surface to another reconstruction35, thus we can exclude any cation segregation. These surface structures are stable upon annealing under the same conditions for a total of 20 h, see Supplementary Fig. 2.

We also prepared a “surface bi-crystal,” i.e., a sample with zones of (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) surface structures. The bulk of the material has thus exactly the same sample history and composition, only the surfaces are different. Sample work functions were determined by measuring the cutoff of secondary electrons (excited by X-rays); the values are 4.470(3) eV and 4.051(10) eV for the (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) reconstructions, respectively (data shown in Supplementary Fig. 5). By comparing the core-level energies in X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) of the two zones on the surface bi-crystal (see Supplementary Fig. 6), no difference in band bending was found, indicating that any surface potential difference is negligible within the measurement uncertainty (±0.03 eV).

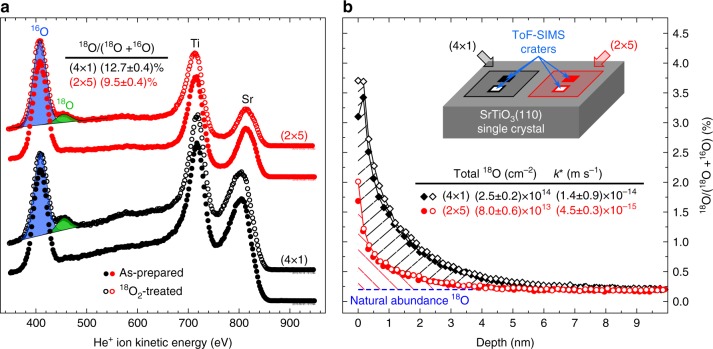

18O2 exchange kinetics from ion spectroscopies

18O exchange was conducted on monophase samples and on the surface bi-crystal sample. The resulting tracer incorporation was evaluated with secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) and low-energy He+ ion scattering (LEIS), see Fig. 3. The LEIS spectra were acquired on the monophase samples in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) right after the 18O treatment (Fig. 3a). Figure 3b shows representative SIMS depth profiles for the 18O isotope on the different zones of the surface bi-crystal; similar results were achieved for the monophase samples (Supplementary Fig. 1). In each case, the (4 × 1)-reconstructed surface incorporates significantly more 18O during the exchange process than the (2 × 5)-reconstructed surface.

Fig. 3.

Oxygen-isotope-sensitive ion spectroscopy measurements performed on the SrTiO3(110)-reconstructed surfaces. a LEIS spectra (He+ with 1000 eV primary energy) measured on (4 × 1)- (black), and (2 × 5)-reconstructed (red) SrTiO3(110) surfaces, respectively. Results from as-prepared and 18O-exchanged samples are displayed with full and open symbols, respectively. Each spectrum is normalized to the total O signal. The uncertainty (standard error) on the fractional 18O signals reported in the table is 0.4% for both surfaces. b ToF-SIMS 18O isotope exchange depth profiles measured on (4 × 1)- (black), and (2 × 5)-reconstructed (red) SrTiO3(110) surfaces of the same crystal. Here, open and full symbols correspond to two separate measurements on different spots on each half of the bi-crystal

Quantification of tracer incorporation at the surface is commonly assessed through the determination of the exchange coefficient k*. This is usually accomplished by fitting the measured tracer fraction profile to analytical or numerical solutions of Fick’s law of diffusion. However, this approach is not applicable in our case, since the profiles in Fig. 3b are extremely shallow due to virtual absence of oxygen vacancies in the bulk of donor-doped SrTiO3 (Supplementary Note 6), and are dominated by SIMS-related broadening effects (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). The total amount of incorporated 18O, however, can still be correctly determined by integration of the 18O profiles (see Fig. 3b). From this total amount of exchanged 18O, an oxygen exchange rate coefficient k* can be obtained (see Methods and Supplementary Eqs. (1–5)). With exchange times of 1 h and 4 h, we find k* to be 4.5–6.0 × 10−15 m s−1 for the (2 × 5)-reconstructed surface, and approximately three times as much (1.4–1.8 × 10−14 m s−1) for the (4 × 1) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, the ratio of effective surface exchange constants k*(4×1)/k*(2×5) amounts to 3.1 ± 0.3 and 3.1 ± 0.6 for the 1 h and 4 h annealing periods, respectively, implying that the incorporation via the surface remains constant over time, at least over several hours. We can thereby exclude that either saturation effects, or different transport in the near-surface regions are responsible for the observed differences between the two reconstructions. Consequently, only the different activity of the respective surface structures is responsible for the threefold larger 18O incorporation on the (4 × 1).

It has to be noted that, with respect to LEIS (Fig. 3b), SIMS (Fig. 3a) measures a larger difference in incorporated oxygen between (4 × 1) and (2 × 5). The reason lies in the different probing depths of the two techniques: While SIMS probes the total amount of tracer ions incorporated in the samples, LEIS is strictly surface sensitive, and therefore probes the 18O density in the topmost surface layer only. This surface 18O density is obtained by scaling the LEIS-measured tracer concentrations with the corresponding density of oxygen atoms in the topmost layer [8.81 × 1014 cm−2 and 1.04 × 1015 cm−2 for (2 × 5) and (4 × 1), respectively], and amounts to (8.4 ± 0.4) × 1013 cm−2 for (2 × 5) and to (1.33 ± 0.04) × 1014 cm−2 for (4 × 1). The 18O density on the (2 × 5) surface nicely agrees with the total SIMS signal [(8.0 ± 0.6) × 1013 cm−2], whereas on (4 × 1) it amounts to half of the total SIMS counts [(2.5 ± 0.2) × 1014 cm−2]. This strongly suggests that oxygen exchange is confined to the topmost surface layer on the (2 × 5), while on the (4 × 1) a few atomic layers are involved. This argument is further strengthened by DFT calculations (see below), which show that oxygen vacancies are more prevalent at the very surface on the (2 × 5), while subsurface sites are favored on the (4 × 1). Moreover, the slight broadening of the SIMS profile found for (4 × 1) after long exchange time (see Supplementary Note 3) supports this conclusion.

O2 reactivity from DFT calculations

The availability of well-supported atomic surface models31,34,35 (Fig. 1) and the fact that these structures are not affected by annealing in 18O2 (Fig. 2) allow us to directly relate the experimental results to first-principles calculations. We first evaluated the formation energies for O vacancies at various positions within the reconstruction layer, both on the top of the surface and closer to the interface with the underlying SrTiO3 bulk lattice (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 1). The formation of the lowest-energy VO on the (2 × 5) surface layer is more favorable by 2.2 eV than on the (4 × 1) surface. Thus, ease of surface VO formation is clearly not a decisive factor in the 18O exchange.

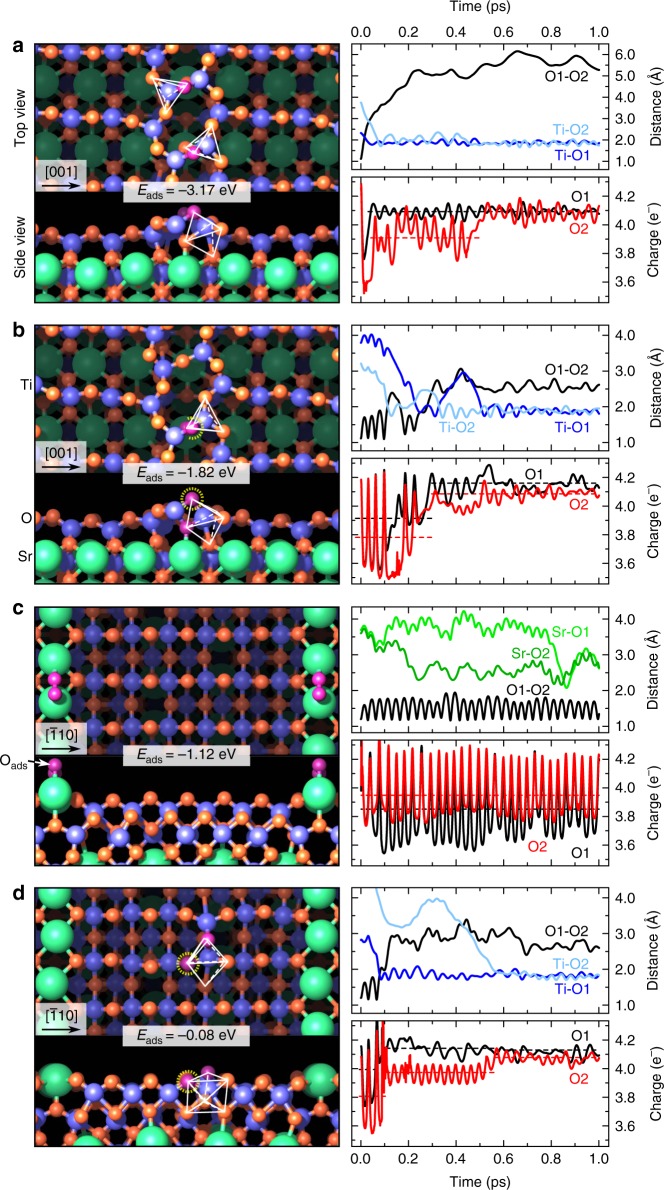

Next, we modeled with first-principles molecular dynamics (FPMD) the interaction of O2 considering a vacancy-free surface and a defective one with a single VO for each of the two reconstructions. The adsorption structures with the lowest energy at the end of the FPMD runs are displayed in Fig. 4, along with the corresponding relative adsorption energies Eads. These structures are thermodynamically stable, as proven by the phase diagram shown in Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12. Additional (less stable) configurations are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 2. The kinetics of the entire process of oxygen incorporation depends on the adsorption energies as well as the unit reaction energy barriers. The rate of incorporation of oxygen from surface to subsurface is affected by the concentration of adsorbed oxygen at the surface. That term, the source of oxygen incorporation, is determined by adsorption energies. For the vacancy-free surfaces, O2 dissociative adsorption/incorporation is considerably more favorable in the (4 × 1) structure. Even without a VO, O2 easily dissociates and incorporates into the (4 × 1) surface at both the six-member and the ten-member rings of TiO4 tetrahedra, with an energy gain of −3.17 eV and −2.94 eV, respectively. On the vacancy-free (2 × 5) surface, in contrast, O2 does not dissociate. It stays anchored on top of the Sr rows (see Fig. 4c). O2 adsorption and dissociation is also energetically highly unfavorable on the flat TiO6 area, resulting in a positive adsorption energy (see Supplementary Fig. 8). If VOs are present in the (2 × 5) structure, they play the role of an active center for O2 dissociation (see Fig. 4d): one O fills the VO site, whereas the second one hops into a nearby bridge position between two surface Ti atoms. We note here that it is important to consider and compare these adsorption energies in the kinetics of oxygen incorporation.

Fig. 4.

O2 adsorption structures and O2 dynamics calculated by FPMD-DFT. Lowest-energy structural models and time evolution (first 1.0 ps; for later time the results remain unchanged) of selected ionic distances and charge populations during the adsorption of one O2 on a the (n × 1) and c the (2 × n) surfaces without a vacancy, and on b the (n × 1) and d the (2 × n) surfaces with one VO (the O atom filling the VO is highlighted with a dashed yellow circle). Adsorption energies are indicated, and take into account also the VO formation energy. Green, red, and blue spheres indicate Sr, O, and Ti atoms, respectively. The intact, adsorbed O2 molecule and the O atoms resulting from its dissociation are depicted in purple. Five- (a, b) and sevenfold (d) coordination polyhedra of Ti are outlined in white. O1 and O2 refer to the oxygen atoms belonging to the O2 molecule, while Ti–O1 (Ti–O2) is the distance between O1 (O2) and the closest Ti atom in the structure

These results can be rationalized by inspecting the time evolution of the relevant ionic distances and the O2 valence charge during the dissociation of the O2 molecule in the (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) surfaces without and with vacancy36, see Fig. 4. In the (4 × 1) phase, the O1–O2 bond of the O2 molecule breaks rapidly during the initial 0.3 ps, and the O1/O2 valence charges increase by about 0.3 electrons as a result of charge transfer from the surface Ti atoms. The O2 dissociation mechanism in the vacancy-free (4 × 1) surface is different compared to the defective surface. Without VO the dissociated O atoms bind to surface Ti atoms located on opposite sides of the six-member ring, as confirmed by the increasing O1–O2 distance and the decrease of the Ti–O distances. Instead, on the defective surface, one O atom remains at the surface filling the VO site and re-establishing the Ti–O bond, while the second one is incorporated in the subsurface, increasing the coordination of the Ti atoms from TiO4 to TiO5. The overall energy gain, −1.82 eV, is reduced by about 1.3 eV with respect to the vacancy-free surface due to the large energy cost to form VOs (see Supplementary Table 1). A similar dissociation mechanism is at play on the defective (2 × 5) surface (Fig. 4d) but the final energy gain is much smaller—by 1.74 eV—compared to (4 × 1). Conversely, on the vacancy-free (2 × 5) surface, the O1–O2 bond does not break (the bond length oscillates between 1.2 Å and 1.6 Å), and the O2 molecule binds weakly to the underlying Sr atoms.

We have also computed the activation energy for the O2 dissociation process on both surfaces with nudged elastic band (NEB) calculations. Since O2 dissociation is endothermic on the vacancy free (2 × 5) (Supplementary Fig. 8), we have only considered the vacancy-free (4 × 1) and both the (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) surfaces with one VO. The results, collected in Supplementary Fig. 9, deliver low transition barriers: 0.3 eV for the clean and defective (4 × 1), and 0.1 eV for the defective (2 × 5) reconstruction.

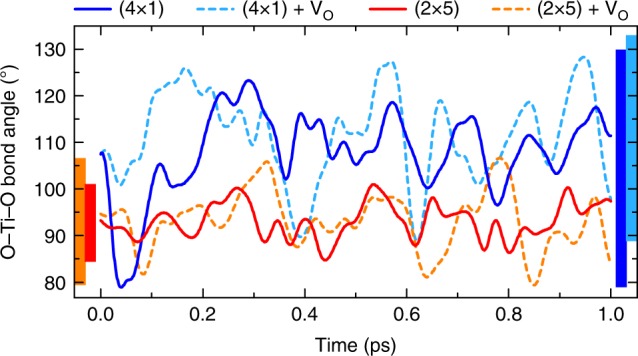

We attribute the different reactivity of the (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) surfaces to the different degree of structural flexibility of the TiO4 and TiO6 surface polyhedra, manifested by the dynamical structural reorganization (rotations and distortions associated with phonon softening, see Supplementary Note 10 and ref. 37) of the TiO4 and TiO6 units during the adsorption process. The time evolution of the average O–Ti–O angle of surface polyhedra in the (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) surfaces, displayed in Fig. 5, shows that the under-coordinated TiO4 polyhedra undergo much larger oscillations compared to the TiO6 units. The ease of performing such structural distortions ultimately provides the (4 × 1) surface with the structural flexibility to host external adsorbates such as O2, and off-stoichiometry facilitates charge transfer from the under-coordinated Ti atoms to the adsorbed oxygen. In contrast, stoichiometric TiO6 octahedra are structurally rigid and chemically saturated, and active adsorption and migration is reduced or suppressed, unless oxygen vacancies that reduce the TiO6 coordination are formed. In other words, such dynamic reorganization performs similarly to a mobile oxygen vacancy at the surface, and represents an alternative way to promote the oxygen incorporation reaction.

Fig. 5.

Dynamical reorganization of the TiO4 and TiO6 polyhedra. Time evolution of the average O−Ti−O angle in the (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) surfaces with and without oxygen vacancy. Trajectories are shown during the first 1.0 ps, but qualitatively similar results are obtained for the whole time range considered in the calculation (10 ps). Vertical bars indicate the maximum amplitude of the oscillations during the whole simulation period

Discussion

Our experimental and computational results are at odds with the commonly accepted models for oxygen exchange mentioned above, i.e., availability and mobility of VOs6–10 and the electronic effects that facilitate electron transfer11–14. Our experimental and theoretical methods allow us to independently assess these factors: their values suggest a higher reactivity of the (2 × 5) structure, the opposite of what is observed in the 18O experiments.

From our DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 1), the (2 × 5) surface should accommodate a larger concentration of oxygen vacancies at the surface compared to (4 × 1). The preferential vacancy formation sites on the (4 × 1) system are, in fact, sub-surface38. Therefore, the vacancy mechanism cannot explain the higher reactivity of the (4 × 1) compared to the (2 × 5) surface. When it comes to the ease of electron transfer, the surface work function is a good measure to correlate to reactivity11–14. The work function measured by XPS and calculated by DFT is lower by 0.42 eV and 0.7 eV, respectively, for the (2 × 5) compared to the (4 × 1) surface. The core-level binding energies measured on the (4 × 1) and the (2 × 5) surfaces are the same (Supplementary Fig. 6). Therefore, the surface potential or band bending (if it exists) is the same on these two surfaces, and the vacuum level on the (2 × 5) surface should be lower. In addition, the (4 × 1) surface has a larger band gap than the (2 × 5)38. Therefore, electron transfer to O2 molecules should be easier at the (2 × 5) surface. Again, this cannot explain why (4 × 1) is more reactive. In addition, from our STM images it is clear that the step density, which can significantly enhance reactivity39, is comparable on both surfaces, or slightly higher at the (2 × 5) surface after oxygen exchange treatment (Fig. 2). Thus, step density cannot be the reason for the higher reactivity of the (4 × 1) either. Consequently, none of these traditionally considered models related to vacancies, electronic structure, or step edges for controlling the reactivity of oxide surfaces are able to explain the difference found between the reactivities of the (4 × 1)- and (2 × 5)-reconstructed surfaces on SrTiO3(110).

Our computational results reveal that oxygen incorporation on SrTiO3(110) is affected directly via the atomic structure itself. The lower coordination of Ti by O atoms on the (4 × 1) accommodates the adsorbed/dissociated oxygen by increasing the coordination of Ti, either at the top surface or by incorporating oxygen atoms to the first subsurface layer. In other words, the enhanced reactivity of the (4 × 1) toward O2 dissociative adsorption and incorporation is a result of the increased degree of structural and chemical flexibility of the under-coordinated TiO4 units as compared to the almost fully coordinated and rigid TiO5 and TiO6 units in the (2 × 5). The rigid TiO6 polyhedra in the (2 × 5) surface cannot accommodate more oxygen unless surface VOs assist the reaction.

Thus, we suggest that two parallel oxygen exchange mechanisms are present on our SrTiO3 surfaces: a structurally mediated mechanism, dominating the exchange rate on the (4 × 1) surface, and a vacancy-mediated one, enabling exchange also on the (2 × 5) surface.

Existence of a vacancy-mediated oxygen exchange is often assumed in the literature, and the oxygen exchange rate is frequently compared with the (bulk) VO concentration6. A direct and proportional dependence of the k* on the oxygen vacancy concentration in the bulk was shown for some perovskite oxides6. k* divided by the fraction of oxygen sites occupied by VOs, denoted here as k*V, amounts to 10−6 m s−1 and 10−5 m s−1 for LSCF and BSCF, respectively, at 800 °C in air6, and to 10−9–10−8 m s−1 for LSC at 450 °C and 200 mbar O240. On (2 × 5)-reconstructed surfaces of our 0.5 wt.% Nb-doped SrTiO3(110), k*V is at least on the order of 10−4 m s−1 at 450 °C and 0.1 mbar oxygen (see Supplementary Note 6 for estimates of the vacancy concentration in our samples). Intriguingly, this value is comparable to that on LSCF and BSCF, and several orders of magnitude higher than the values reported for LSC. A possible factor contributing to this large discrepancy is the completely clean and stable atomic structures that are retained without any segregation of cations, impurities, or secondary phases on our samples. The often-found surface segregation and phase precipitation of SrOx or impurities on the aliovalently doped systems hinder their surface reactivity by blocking the electron and oxygen transfer reactions30,41,42. Indeed, a substantially enhanced k* was found for a clean LSC surface upon removal of the SrOx termination layer43. Presumably, for vacancy-rich perovskite oxides the full potential of oxygen activity has not been exploited yet. These findings further demonstrate that establishing physics-based relations of the very surface state to the reaction kinetics is needed for a mechanistic understanding, rather than relying only on bulk non-stoichiometry of oxygen as a descriptor.

In summary, we have realized a comprehensive and gap-bridging approach between model surfaces with well-defined atomic structure and macroscopic kinetic measurements of reaction rates, and revealed a dependence of reactivity on the precise surface atomic structure on a perovskite oxide. The oxygen exchange kinetics is three times faster on the (4 × 1)-reconstructed surface of SrTiO3(110) than on the (2 × 5) one. Neither availability of surface vacancies nor the work function or band bending can explain this enhanced reactivity of the (4 × 1) surface. We find that the surface atomic structure itself has the dominant role by assisting the oxygen adsorption and dissociation on the (4 × 1) surface, owing to a high degree of dynamical flexibility of the under-coordinated surface Ti atoms. This directly demonstrates and explains the influence of reconstructions on the reactivity of a perovskite oxide. Reconstructions are prevalent at the surfaces of any complex oxide44, and oxides with other transition metal cations such as Fe, Mn, and Co can as well form different polyhedral coordinations45,46. Accordingly, the higher flexibility of unsaturated metal–oxygen polyhedra may play a role in affecting the ease of oxygen incorporation on a broader range of perovskite oxide surfaces. Most importantly, the gap-bridging approach that we demonstrated here should motivate more research in resolving the surface atomic structure and relating that to reactivity on a wider range of perovskite oxides.

Methods

Sample preparation

The surfaces of one-side polished, Nb-doped (0.5 wt.%) SrTiO3(110) single crystals (5 × 5 mm2, Crystec GmbH) were prepared in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) system47. The latter is composed of three in situ interconnected vessels: The preparation chamber is used for Ar-ion sputtering, electron-beam annealing, and contains molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) facilities. The analysis chamber houses a low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) setup, a hemispherical analyzer for X-ray photoelectron (XPS) and low-energy ion scattering (LEIS; 1 keV He+; scattering angle 132°) spectroscopies, and a variable-temperature scanning tunneling microscope (STM). The oxygen exchange experiments were performed in the third vessel (pulsed laser deposition chamber), allowing for infrared-laser annealing of samples at elevated oxygen pressures (up to 200 mbar).

The SrTiO3(110) crystals were cleaned in the preparation chamber by repeated cycles of sputtering (1 keV, 5 μA, 10 min) and annealing in O2 gas (1000 °C, 3 × 10−6 mbar, 1 h), to remove contamination. The surface of each sample was then prepared to exhibit predominantly a (4 × 1) or a (2 × 5) structure. The (4 × 1) structure was obtained by deposition of sub-monolayer amounts of Sr or Ti at room temperature, and subsequent annealing in an O2 background (1000 °C, 3 × 10−6 mbar, 30 min)35. Particular care was taken in obtaining a uniform structure over the whole sample surface, by deposition of small amounts of metals while partly shadowing the sample with a dedicated shutter. The (2 × 5)-reconstructed surfaces were obtained by reactively depositing (5 × 10−6 mbar O2) 0.8 Å Ti at 600 °C on SrTiO3(110)-(4 × 1). Two sets of samples were prepared: either single-phase [uniformly (4 × 1)- or (2 × 5)-reconstructed on a given crystal], to allow for STM characterization, or with both the (4 × 1) and (2 × 5) co-existing on the same crystal surface, each occupying ~5 × 2.5 mm2. In the latter case, half of the sample surface was shadowed during reactive deposition of Ti to induce the (2 × 5) surface after the (4 × 1) surface was formed. We refer to the latter as a “surface bi-crystal.” The results obtained with the two sets of samples were checked for consistency by comparing the LEED patterns on several spots on the sample at each preparation step, and after the subsequent treatments.

18O isotope exchange

To ensure the stabilization of a steady-state oxygen vacancy (VO) concentration, the as-prepared samples were first annealed in situ in flowing O2 gas of natural isotope composition (referred to as 16O2) for 4 h or 16 h, at 450 °C and 0.1 mbar, with 60 °C min−1 heating and cooling ramps. The reason for performing the exchange at a relatively low temperature and oxygen pressure is to minimize the risk of atomic surface structure changes. Furthermore, because of the very low vacancy concentration (as explained above), the O2 exchange is expected to be limited to the near-surface region without bulk transport. Prior to the equilibration step, the vessel was continuously flushed with 16O2 (20 sccm) for 1 h; this ensures reproducible conditions in the vacuum chamber. The pumping speed was regulated to stabilize a pressure of 1 mbar. Finally, each sample was annealed in isotopically labeled oxygen (97.1% 18O2, referred to as 18O2 for brevity) for 1 h or 4 h, at 450 °C and 0.1 mbar (static) with heating and cooling ramps of 60 °C min−1 and 120 °C min−1, respectively. Similar to the 16O2 equilibration step, the chamber was pre-conditioned in 18O2 at 0.5 mbar static pressure for 30 min prior to each experiment. After the 18O2 treatments, samples were analyzed with LEED, XPS (both monophase and surface bi-crystal samples), STM, and LEIS (monophase samples only) in situ, i.e., in the UHV apparatus, and then transported to the time-of-flight–secondary-ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) setup.

Depth profiling and quantification of 18O

Oxygen-isotope depth profiles were analyzed via ToF-SIMS on a TOF-SIMS 5 instrument (ION-TOF, Germany). 25 keV Bi3++ clusters (0.02 pA) were used as primary ions in collimated burst alignment mode optimized for oxygen isotope measurements18,48. Negative secondary ions were detected from areas of 100 × 100 µm2 using a raster of 512 × 512 measured points, and the secondary ion counts of 16O− and 18O− were used to determine the isotopic composition f = 18O/(18O + 16O). For depth profiling, areas of 400 × 400 µm2 were sputtered using Cs+ ions, and the depth information was calculated from the sputter coefficients and sputter currents, referenced by measuring the depth of the sputter craters via digital holography microscopy. An electron flood gun (21 eV) was used for charge compensation.

For calculating the average oxygen exchange coefficient k* from the measured fraction of incorporated 18O (fm), the 18O fraction in the stainless steel UHV vessel (fout) was estimated as 0.971, corresponding to the original 18O concentration of the tracer-enriched oxygen. The validity of this assumption was tested by exchanging (at 700 °C) 18O into a fast-mixed ionic electronic conductor, a 50 nm-thick La0.6Sr0.4CoO3 film grown on SrTiO3(001)40, under nominally identical gas composition as the exchange experiment performed on the SrTiO3(110) crystals in the same UHV setup. Since fout is much larger than all tracer fractions measured in the Nb-doped SrTiO3 single crystals, we can approximately assume a constant tracer exchange flux density j during the exchange time t. Within this assumption, the effective oxygen exchange coefficient can be expressed as (see Supplementary Note 2 for the full derivation)

| 1 |

In Eq. (1), fbg denotes the background tracer fraction (approximated by the natural abundance fbg = 0.00205), cO is the concentration of oxygen sites, and ds is the sputter depth per measurement point.

First-principles calculations

All calculations were carried out using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)49,50 in the framework of density functional theory (DFT) within the generalized gradient correction approximation of Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof51. The surface reconstructions were modeled with symmetric slabs composed by five layers plus the reconstructed surfaces, separated by ~12 Å of vacuum. We used the same (4 × 4) two-dimensional base unit cell for both types of SrTiO3(110) reconstructions, effectively modeling (4 × 2) and (2 × 4) reconstructions. (4 × 2) and (4 × 1) belong to the same (n × 1) structure family, and (2 × 4) and (2 × 5) belong to the same (2 × n) surface structure family. For consistency with the experimental description, we refer to the slabs representing the (n × 1) overlayer as (4 × 1), and the (2 × n) overlayer as (2 × 5) in the text. The surface geometry was optimized by keeping the central three layers fixed to the corresponding bulk positions and relaxing the remaining atomic positions until the forces on each atom were less than 0.02 eV Å−1. For the Brillouin-zone integration, we have adopted a 2 × 2 × 1 k-point grid, corresponding to an 8 × 8 × 1 mesh for the 1 × 1 cell, and used a standard energy cutoff of about 300 eV for the plane-wave expansion. The formation energy of one oxygen vacancy formed on both sides of the symmetric slab was computed using the standard relation

| 2 |

where is the DFT energy of an isolated oxygen molecule, whereas Etot(2VO) and Etot(0VO) represent the DFT total energies of the slabs with and without oxygen vacancies, respectively.

The interaction between the surfaces and oxygen atoms was modeled by studying the adsorption, dissociation, and dynamics of one O2 molecule by means of first-principles molecular dynamics (FPMD) and the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB)52. To reduce the computational costs, the FPMD and CI-NEB calculations were performed using asymmetric slabs with a reduced energy cutoff (250 eV) and a smaller k-mesh (1 × 1). The FPMD calculations were performed at the simulating temperature of 700 K for 5–10 ps using a canonical ensemble and the Nosé thermostat algorithm53. For the estimation of energy barriers within the CI-NEB method, five images were constructed, and the convergence criteria for the forces was reduced to 0.05 eV Å−1.

Relative adsorption energies Eads per O2 molecule, as given in the text, are defined as , where Eslab and Eclean are the T = 0 DFT total energies of the full slab containing the O2 molecule and the clean surface, respectively. refers to the oxygen vacancy formation energy at site S, chosen as the energetically least costly VO3 and VO4 for the (4 × 1) and (2 × 5)-like surfaces, respectively (see Supplementary Note 7), and x indicates the number of oxygen vacancies in the slab.

Work functions were computed as the difference between the Fermi energy (valence band maximum) and the vacuum level, extracted from the local potential profile in the direction perpendicular to the slab.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (SFB “Functional Oxide Surfaces and Interfaces” - FOXSI, Project F 45) and by the ERC Advanced Grant “OxideSurfaces” (Project ERC-2011-ADG_20110209). B.Y. also thanks for support from the NSF CAREER Award of the National Science Foundation, Division of Materials Research, Ceramics Program, Grant No. 1055583. C.F. acknowledges the support of the FWF-SFB project ViCoM (Grant No. F41). X.H. thanks National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 21303156 and 21543006) for support. The computational results presented have been achieved using the Vienna Scientific Cluster (VSC).

Author contributions

M.R., G.F., and S.G. prepared the samples and performed the STM, XPS, WF, LEED, LEIS, and exchange experiment. M.K., H.H., and J.F. performed and analyzed the 18O SIMS. C.F. and X.H. performed the DFT calculations. M.R., M.K., M.S., J.F., C.F., B.Y., and U.D. wrote the manuscript. J.F., U.D., B.Y., and M.S. designed and coordinated the research.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request. Source data for Figs. 1 and 4, and Supplementary Figs. 7, 9, and 10 are provided with the paper in Supplementary Data 1.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bilge Yildiz, Email: byildiz@mit.edu.

Ulrike Diebold, Email: diebold@iap.tuwien.ac.at.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-05685-5.

References

- 1.Neagu D, Tsekouras G, Miller DN, Ménard H, Irvine JTS. In situ growth of nanoparticles through control of non-stoichiometry. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:916–923. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee KT, Wachsman ED. Role of nanostructures on SOFC performance at reduced temperatures. MRS Bull. 2014;39:783–791. doi: 10.1557/mrs.2014.193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleig J. Solid oxide fuel cell cathodes: polarization mechanisms and modeling of the electrochemical performance. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2003;33:361–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.matsci.33.022802.093258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graves C, Ebbesen SD, Jensen SH, Simonsen SB, Mogensen MB. Eliminating degradation in solid oxide electrochemical cells by reversible operation. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:239–244. doi: 10.1038/nmat4165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chueh WC, et al. High-flux solar-driven thermochemical dissociation of CO2 and H2O using nonstoichiometric ceria. Science. 2010;330:1797–1801. doi: 10.1126/science.1197834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuklja MM, Kotomin EA, Merkle R, Mastrikov YA, Maier J. Combined theoretical and experimental analysis of processes determining cathode performance in solid oxide fuel cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013;15:5443–5471. doi: 10.1039/c3cp44363a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bikondoa O, et al. Direct visualization of defect-mediated dissociation of water on TiO2(110) Nat. Mater. 2006;5:189–192. doi: 10.1038/nmat1592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diebold U. The surface science of titanium dioxide. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2003;48:53–229. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5729(02)00100-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaub R, et al. Oxygen vacancies as active sites for water dissociation on rutile TiO2(110) Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;87:266104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.266104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheiber P, Riss A, Schmid M, Varga P, Diebold U. Observation and destruction of an elusive adsorbate with STM: O2/TiO2(110) Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:216101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.216101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deskins NA, Rousseau R, Dupuis M. Defining the role of excess electrons in the surface chemistry of TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:5891–5897. doi: 10.1021/jp101155t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greiner MT, et al. Universal energy-level alignment of molecules on metal oxides. Nat. Mater. 2012;11:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nmat3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greiner MT, Chai L, Helander MG, Tang WM, Lu ZH. Transition metal oxide work functions: the influence of cation oxidation state and oxygen vacancies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012;22:4557–4568. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201200615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, et al. Electronic activation of cathode superlattices at elevated temperatures - source of markedly accelerated oxygen reduction kinetics. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013;3:1221–1229. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201300025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merkle R, Maier J. Oxygen incorporation into Fe-doped SrTiO3: mechanistic interpretation of the surface reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002;4:4140–4148. doi: 10.1039/b204032h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YL, Kleis J, Rossmeisl J, Shao-Horn Y, Morgan D. Prediction of solid oxide fuel cell cathode activity with first-principles descriptors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011;4:3966–3970. doi: 10.1039/c1ee02032c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brichzin V, Fleig J, Habermeier HU, Cristiani G, Maier J. The geometry dependence of the polarization resistance of Sr-doped LaMnO3 microelectrodes on yttria-stabilized zirconia. Solid State Ion. 2002;152:499–507. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2738(02)00379-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubicek M, et al. A novel ToF-SIMS operation mode for sub 100 nm lateral resolution: application and performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014;289:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.10.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan L, Balasubramaniam KR, Wang S, Du H, Salvador PA. Effects of crystallographic orientation on the oxygen exchange rate of La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 thin films. Solid State Ion. 2011;194:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2011.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burriel M, et al. Influence of crystal orientation and annealing on the oxygen diffusion and surface exchange of La2NiO4+δ. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:17927–17938. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b05666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang SH, et al. Functional links between stability and reactivity of strontium ruthenate single crystals during oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4191. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerman K, Ko C, Ramanathan S. Orientation dependent oxygen exchange kinetics on single crystal SrTiO3 surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012;14:11953–11960. doi: 10.1039/c2cp41918a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayd J, Yokokawa H, Ivers-Tiffée E. Hetero-interfaces at nanoscaled (La,Sr)CoO3-δ thin-film cathodes enhancing oxygen surface-exchange properties. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013;160:F351–F359. doi: 10.1149/2.017304jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter S, et al. Oxygen-transport in selected nonstoichiometric perovskite-structure oxides. Solid State Ion. 1992;53:597–605. doi: 10.1016/0167-2738(92)90435-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao ZP, Haile SM. A high-performance cathode for the next generation of solid-oxide fuel cells. Nature. 2004;431:170–173. doi: 10.1038/nature02863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai Z, Kubicek M, Fleig J, Yildiz B. Chemical heterogeneities on La0.6Sr0.4CoO3-δ thin films-correlations to cathode surface activity and stability. Chem. Mater. 2012;24:1116–1127. doi: 10.1021/cm203501u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee W, Han JW, Chen Y, Cai Z, Yildiz B. Cation size mismatch and charge interactions drive dopant segregation at the surfaces of manganite perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7909–7925. doi: 10.1021/ja3125349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y, et al. Segregated chemistry and structure on (001) and (100) surfaces of (La1-xSrx)2CoO4 override the crystal anisotropy in oxygen exchange kinetics. Chem. Mater. 2015;27:5436–5450. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b02292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Téllez H, Druce J, Ju YW, Kilner J, Ishihara T. Surface chemistry evolution in LnBaCo2O5+δ double perovskites for oxygen electrodes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 2014;39:20856–20863. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.06.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y, et al. Impact of Sr segregation on the electronic structure and oxygen reduction activity of SrTi1-xFexO3 surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012;5:7979–7988. doi: 10.1039/c2ee21463f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, et al. Transition from reconstruction toward thin film on the (110) surface of strontium titanate. Nano Lett. 2016;16:2407–2412. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b05211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohsawa T, Shimizu R, Iwaya K, Shiraki S, Hitosugi T. Negligible Sr segregation on SrTiO3(001)-(√13 × √13)-R33.7° reconstructed surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016;108:161603. doi: 10.1063/1.4947441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heifets E, Piskunov S, Kotomin EA, Zhukovskii YF, Ellis DE. Electronic structure and thermodynamic stability of double-layered SrTiO3(001) surfaces: ab initio simulations. Phys. Rev. B. 2007;75:115417. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.75.115417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z, et al. Strain-induced defect superstructure on the SrTiO3(110) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;111:056101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.056101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z, et al. Evolution of the surface structures on SrTiO3(110) tuned by Ti or Sr concentration. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;83:155453. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.83.155453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugiura S, et al. Role of oxygen vacancy in dissociation of oxygen molecule on SOFC cathode: Ab initio molecular dynamics simulation. Solid State Ion. 2016;285:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2015.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Benedek NA. Enhancement of ionic transport in complex oxides through soft lattice modes and epitaxial strain. Chem. Mater. 2015;27:2647–2652. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b00445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, et al. Anisotropic two-dimensional electron gas at SrTiO3(110) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:3933–3937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318304111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong XQ, Selloni A, Batzill M, Diebold U. Steps on anatase TiO2(101) Nat. Mater. 2006;5:665–670. doi: 10.1038/nmat1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kubicek M, et al. Tensile lattice strain accelerates oxygen surface exchange and diffusion in La1-xSrxCoO3-δ thin films. ACS Nano. 2013;7:3276–3286. doi: 10.1021/nn305987x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kubicek M, Limbeck A, Frömling T, Hutter H, Fleig J. Relationship between cation segregation and the electrochemical oxygen reduction kinetics of La0.6Sr0.4CoO3-δ thin film electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011;158:B727–B734. doi: 10.1149/1.3581114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsvetkov N, Lu Q, Sun L, Crumlin EJ, Yildiz B. Improved chemical and electrochemical stability of perovskite oxides with less reducible cations at the surface. Nat. Mater. 2016;15:1010–1016. doi: 10.1038/nmat4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rupp GM, et al. Correlating surface cation composition and thin film microstructure with the electrochemical performance of lanthanum strontium cobaltite (LSC) electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:7099–7108. doi: 10.1039/C3TA15327D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erdman N, et al. The structure and chemistry of the TiO2-rich surface of SrTiO3(001) Nature. 2002;419:55–58. doi: 10.1038/nature01010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu Q, Yildiz B. Voltage-controlled topotactic phase transition in thin-film SrCoOx monitored by in situ x-ray diffraction. Nano Lett. 2016;16:1186–1193. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nyholm, R. S., Woolliams, P. R., Shepard, D., Guyer, J. & Cohn, K. in Inorganic Syntheses Vol. 11 (ed. Jolly, W. L.) 56–61 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1968).

- 47.Gerhold S, Riva M, Yildiz B, Schmid M, Diebold U. Adjusting island density and morphology of the SrTiO3(110)-(4 × 1) surface: pulsed laser deposition combined with scanning tunneling microscopy. Surf. Sci. 2016;651:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2016.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holzlechner G, Kubicek M, Hutter H, Fleig J. A novel ToF-SIMS operation mode for improved accuracy and lateral resolution of oxygen isotope measurements on oxides. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2013;28:1080–1089. doi: 10.1039/c3ja50059d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kresse G, Hafner J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;48:13115–13118. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.48.13115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996;6:15–50. doi: 10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henkelman G, Uberuaga B, Jónsson H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;113:9901–9904. doi: 10.1063/1.1329672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nosé S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:511–519. doi: 10.1063/1.447334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request. Source data for Figs. 1 and 4, and Supplementary Figs. 7, 9, and 10 are provided with the paper in Supplementary Data 1.