Abstract

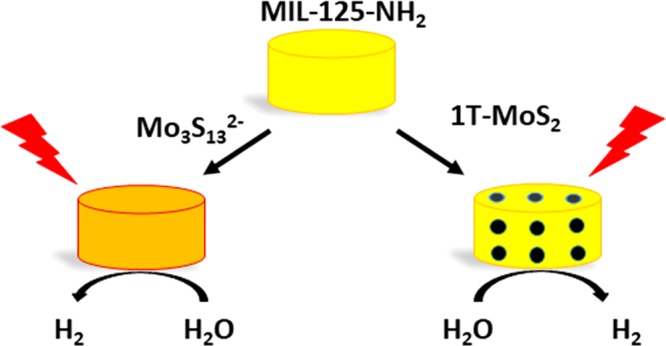

We report the use of two earth abundant molybdenum sulfide-based cocatalysts, Mo3S132– clusters and 1T-MoS2 nanoparticles (NPs), in combination with the visible-light active metal–organic framework (MOF) MIL-125-NH2 for the photocatalytic generation of hydrogen (H2) from water splitting. Upon irradiation (λ ≥ 420 nm), the best-performing mixtures of Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 and 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 exhibit high catalytic activity, producing H2 with evolution rates of 2094 and 1454 μmol h–1 gMOF–1 and apparent quantum yields of 11.0 and 5.8% at 450 nm, respectively, which are among the highest values reported to date for visible-light-driven photocatalysis with MOFs. The high performance of Mo3S132– can be attributed to the good contact between these clusters and the MOF and the large number of catalytically active sites, while the high activity of 1T-MoS2 NPs is due to their high electrical conductivity leading to fast electron transfer processes. Recycling experiments revealed that although the Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 slowly loses its activity, the 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 retains its activity for at least 72 h. This work indicates that earth-abundant compounds can be stable and highly catalytically active for photocatalytic water splitting, and should be considered as promising cocatalysts with new MOFs besides the traditional noble metal NPs.

Keywords: metal−organic framework, hydrogen, molybdenum sulfide, photocatalysis, visible light

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are crystalline porous materials prepared by the self-assembly of metal ions or clusters with organic ligands to form 1-, 2-, or 3-dimensional structures. Because of their high porosity and structural tunability, MOFs are promising for applications in many areas, such as gas storage and separation,1 catalysis,2 and sensing,3 among others. In recent years, several semiconducting MOFs have also been employed as photocatalysts for photocatalytic reactions since the use of MOFs can overcome the disadvantages of the traditional photocatalysts such as the negligible absorptivity of visible light of TiO2 or the low water stability of CdS. Among photocatalytic reactions, the generation of hydrogen (H2) from water is of great interest mainly because of the potential of H2 as a clean energy carrier for a sustainable energy future.4 To efficiently produce H2, MOFs are often coupled with a small amount (<10 wt %) of a cocatalyst, for example, platinum (Pt) nanoparticles (NPs), that attract the photogenerated electrons, and a sacrificial electron donor which donates its electrons to the photogenerated holes to protect the MOF from degradation.

Within the MOF field, the main research efforts in recent years have been focused on the preparation of new visible-light responsive MOFs since the practical use of these MOFs for photocatalytic H2 generation would require the absorption of sunlight, 44% energy of which is provided by light in the visible domain. Up to now, several transition metal-based MOFs, such as MIL-125-NH2, UiO-66-NH2, Al-PMOF, and others, have been known to produce a fairly high amount of H2 under visible light irradiation when they are combined with Pt NPs.5−8 Given the success of Pt NPs as a cocatalyst in H2 production for a large range of different photoactive materials, it has become the “gold” standard in the field. Interestingly, there are also a few reports indicating that suitable earth-abundant cocatalysts can promote H2 generation,9,10 and some of them, such as a Co complex or Ni2P NPs, can outperform Pt NPs with the same MOF in terms of H2 evolution rate and apparent quantum yields.11−13 The fact that a careful choice of the cocatalyst can significantly enhance the H2 generation performance adds a new dimension to this system since the number of possible earth-abundant complexes and NPs with oxides, sulfides, phosphides, or nitrides is essentially limitless. In this work, we investigate the efficiency of molybdenum sulfide-based cocatalysts when combined with MOFs.

Natural molybdenum sulfide (2H-MoS2, H stands for hexagonal symmetry), which is an indirect-band gap (1.29 eV) semiconductor, is an earth-abundant compound that has been well-studied due to its unique electronic, optical and magnetic properties, as well as its potential for applications in electronics, optoelectronics, energy devices and in H2 generation.14 The sulfur edge sites and vacancy defects of 2H-MoS2 were found to be the active sites for the H2 generation reaction,15,16 while the basal planes are catalytically inert. Reducing the size of the 2H-MoS2 particles to achieve greater density of edge sites has shown an improved photocatalytic H2 evolution activity.17 Interestingly, this contraction can even be accomplished at the molecular level; one example is the Mo3S132– cluster, (Figure 1a), which essentially resembles the smallest fraction of MoS2. Another strategy to increase the catalytic activity of MoS2 is to tweak its 2H crystal phase to obtain a polymorph with increased electrical conductivity and hence enhance the electron transfer to the active sites. For example, the 1T-MoS2 (T stands for trigonal symmetry) can be achieved by a lithium (Li) intercalation-exfoliation procedure resulting in a metastable metallic phase.18 Despite their promising catalytic activity for H2 generation,19,20 both Mo3S132– and 1T-MoS2 have not been employed as cocatalysts with MOFs in photocatalytic water reduction.

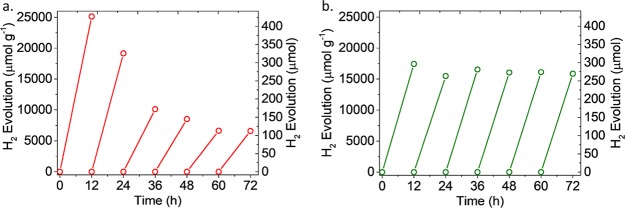

Figure 1.

(a) X-ray crystal structure of the Mo3S132– cluster (color code: turquoise Mo, yellow S).13 (b) SEM image of the 1T-MoS2. (c and d) XPS spectra of Mo3S132– and 1T-MoS2, respectively.

Herein, we report the combination of Mo3S132– and 1T-MoS2 with the well-known visible-light-responsive Ti-based MIL-125-NH2 for photocatalytic H2 generation. Both systems exhibit excellent evolution rates and apparent quantum yields; in addition, the easy synthesis and durable performance of the 1T-MoS2 NPs suggest that not only can earth-abundant NPs be good cocatalyts but also they can be considered as common cocatalysts, besides the standard Pt NPs, for photocatalytic testing of novel MOF photocatalysts.

The Mo3S132– clusters (full chemical formula (NH4)2Mo3S13·2H2O) and the 1T-MoS2 NPs were synthesized based on slight modifications of the reported procedures (SI). The cluster contains three MoIV ions and three different types of S ligands, including three bridging μ2-S22–, three terminal S22–, and one μ3-S2–. Except for the μ3-S2–, all the other sulfur atoms are appropriately positioned for effective catalysis.21 The good match of the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns (Figure S1) and the presence of the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) MoIV3d5/2 and MoIV3d3/2 peaks at 229.84 and 232.97 eV (Figure 1c), respectively, confirmed that the Mo3S132– clusters were formed without oxidized impurities. Immersing the crystalline powder of Mo3S132– in water for 24 h did not affect its crystallinity (Figure S1). Cyclic voltammetry studies were performed in a dimethylformamide (DMF) solution of Mo3S132–; the cyclic voltammogram (Figure S5) displays the first MoIV → MoIII reduction peak at ∼−0.44 V, which is less negative than the energy of the conduction band of MIL-125-NH2 (∼−0.60 V),22 suggesting that Mo3S132– can be used as a cocatalyst with MIL-125-NH2 for the reduction of water (Figure S6).

The 1T phase of MoS2 has often been obtained via a Li intercalation-exfoliation process, which involves soaking the bulk 2H-MoS2 material in hexane solution of n-butyl lithium under inert atmosphere for several days followed by exfoliation using ultrasonification.18 Because of the low yield of this procedure, we prepared our 1T-MoS2 following a recently reported one-step hydrothermal method with a slight modification (SI) that can easily give a high amount of the product.23 The PXRD pattern of the 1T-MoS2 sample (Figure S2) displays comparable Bragg reflections with those of the commercial MoS2; however, the peaks are broader due to their nanoscale size. Immersing the powder in water for 24 h did not cause any changes in the pattern (Figure S2). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the 1T-MoS2 (Figure 1b) show that the sample contains aggregates of flakes, with the size varying between few hundred nm to ∼2 μm. As can be seen in the deconvoluted XPS spectrum in Figure 1d, the majority of the sample contains 1T-MoS2 (∼75%, MoIV3d5/2 and MoIV3d3/2 peaks at 228.62 and 231.75 eV, respectively), ∼17% of the sample is the 2H-MoS2 (MoIV3d5/2 and MoIV3d3/2 peaks at 229.80 and 232.93 eV, respectively), while the oxidized impurities containing MoVI comprise ∼8% (MoVI3d5/2 and MoVI3d3/2 peaks at 231.94 and 235.07 eV, respectively). Raman spectrum of the 1T-MoS2 sample (Figure S12) shows peaks at ∼150 cm–1 (J1), ∼230 cm–1 (J2), and ∼334 cm–1 (J3), along with peaks at ∼280 cm–1 (E1g), ∼376 cm–1 (E1g1), ∼404 cm–1 (A1g), which are consistent with the ones reported for Li-intercalated 1T-MoS2.14

Both crystalline powders of Mo3S132– and 1T-MoS2 were subjected to photocatalytic testing with MIL-125-NH2 by simply mixing them in a 25.0 mL vial containing 17.0 mL solution of acetonitrile (MeCN): triethylamine (TEA): water (H2O) (79.0:16.1:4.9 v/v/v) mixture. The solution was purged with N2 before any test. Under visible light irradiation (xenon lamp, long-pass cutoff filter λ ≥ 420 nm) and by varying the added amount of Mo3S132– and 1T-MoS2 while keeping the amount of MIL-125-NH2 constant (17.0 mg), it was found that with 0.82 wt % added amount of the cocatalyst in both cases, the photocatalytic systems produced their highest H2 evolution rates (Figures S16 and S17), which are 2094 and 1454 μmol h–1 g–1MOF for Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 and 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2, respectively. These values are much higher than the H2 evolution rate of 68 μmol h–1 g–1MOF when the same added amount of the commercial MoS2 (Aldrich, <2 μm) was used as the cocatalyst, which exemplifies the enhanced catalytic activity of MoS2 by either decreasing the size of its particles or increasing their electrical conductivity. These H2 evolution rates are also much higher than those of other photocatalytic systems with MIL-125-NH2, for example, the H2 evolution rates of Pt/MIL-125-NH2, Co-oxime@MIL-125-NH2, and Ni2P/MIL-125-NH2 in similar reaction conditions are 269, 637, and 894 μmol h–1 g–1MOF.11,13 In fact, to the best of our knowledge, these rates are the highest values reported to date for visible-light-driven photocatalysis with MOFs incorporated with a cocatalyst. It is worth noting that several (semi)conductors such as ZnIn2S4 or graphene were employed to form composites with MOFs to significantly enhance their H2 evolution rates but they are present in high weight percentages (>50 wt %) and are not considered cocatalysts.24,25

Apparent quantum yields were measured for the best-performing mixtures of Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 and 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2. The measurement were based on the ferrioxalate actinometry method, which first involves the determination of the incident radiation over time (number of photons in a unit of time) of the xenon lamp. The apparent quantum yield (Φ) is then calculated based on eq 1

| 1 |

where nH2 is the number of moles of H2 produced in the time t1, nphoton is the number of moles of photons irradiated during the time t2. The apparent quantum yields for Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 and 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 are 11.0 and 5.8% at 450 nm, respectively, which are excellent compared to the other reported photocatalytic MOF-based systems.11,13,26−29

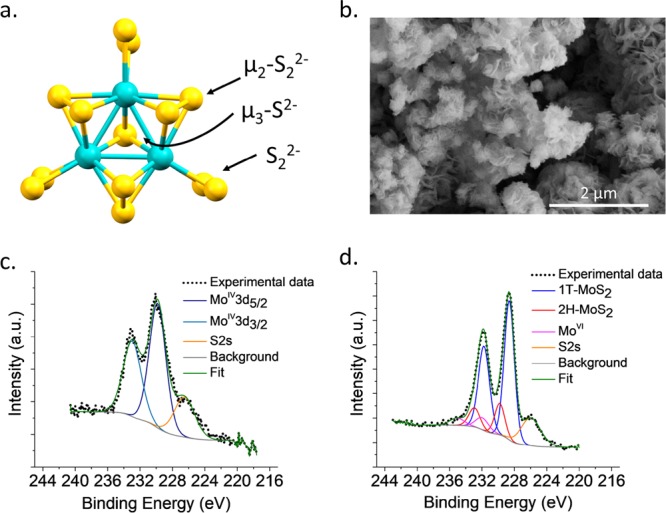

It is worth noting that the performance of a cocatalyst/MOF system depends on several factors as follows: (i) the driving force for electron transfer from the MOF to the cocatalyst, which depends on the energy gap between them, (ii) the contact/interaction between the MOF and the cocatalyst, and (iii) the inherent catalytic activity of the cocatalyst. To investigate the electron transfer from MIL-125-NH2 to Mo3S132– and 1T-MoS2 in their suspension mixtures, luminescence emission (λex = 420 nm) of these solutions were measured together with the emission by MIL-125-NH2 itself. As shown in Figure 2a, the presence of the cocatalysts (0.82 wt %) quenches the luminescence of the MOF since some of the photogenerated electrons are nonradiatively transferred to the Mo3S132– clusters or 1T-MoS2 NPs. It appears that the Mo3S132– clusters do not attract electrons as efficient as the 1T-MoS2 NPs; however, since the clusters are relatively soluble in the MeCN/TEA/H2O solution and are adsorbed by the MIL-125-NH2 (Figure 2b), the interaction between each cluster and the MOF is maximized, together with the inherent high catalytic activity, which apparently compensates for their lower electron affinity. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations (SI) were performed and illustrated that due to the relatively large size (6.5 Å) of the Mo3S132– cluster, the probability for its diffusion from one pore to another is negligible, suggesting that the adsorption only occurs on the MOF’s surface. Nevertheless, the energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping images (Figure S11) of Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 powder after 8 h of irradiation confirmed the even distributions of Mo3S132– on the external surface of MIL-125-NH2 crystals.

Figure 2.

(a) Luminescence emission spectra (λex = 420 nm) of MIL-125-NH2 without and with the cocatalysts. (b) UV–vis absorption spectra of the MeCN/TEA/H2O solution of Mo3S132– and of the supernatant after adding MIL-125-NH2, showing the disappearance of the absorption peak at ∼480 nm, indicating that the clusters are adsorbed by the MOF. (c) SEM and EDX mapping images of 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 after 72 h of irradiation, with the 1T-MoS2 NPs evenly embedded on the surface of the MIL-125-NH2 crystals.

SEM and EDX mapping images were also obtained for 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 (Figure 2c). As can be clearly seen in the SEM image, the NPs attach on and cover the surface of the MIL-125-NH2 crystals allowing for the enhanced interaction between them. It was reported that the basal plane of 1T-MoS2 nanosheets is also active for the H2 generation reaction.14 Therefore, for 1T-MoS2, their high electron affinity, their relatively good contact with the MOF and their high catalytic activity are combined to give the observed high photocatalytic performance.

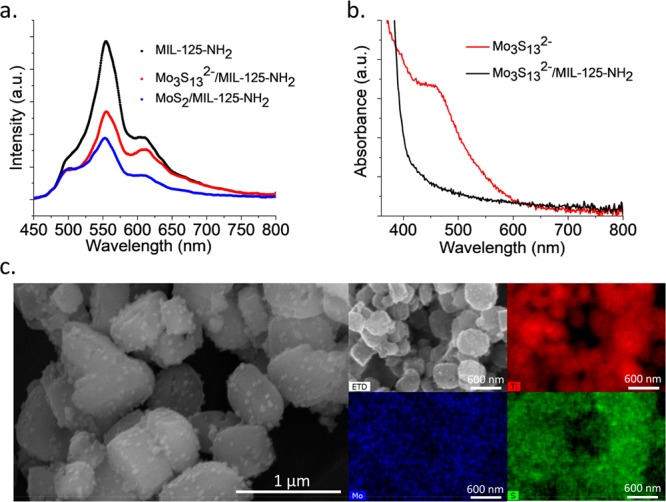

For practical applications, an effective cocatalyst should maintain its activity over a long period of time. Recycling experiments were therefore conducted, in which after every 12 h the reactor containing the best-performing cocatalyst/MIL-125-NH2 was purged with N2 gas to release the H2 produced in the head space before a new cycle. While the 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 maintained its H2 evolution rate (Figure 3b), the Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 slowly lost its performance (Figure 3a), probably due to the gradual decomposition of the clusters over time. The low stability of Mo3S132– in basic solutions was also previously observed.19 PXRD patterns of Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 and 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 after irradiation were collected; however, the peaks for Mo3S132– and 1T-MoS2 were not observed due to the dissolution of the former and the very low concentration of the latter. Nevertheless, the MIL-125-NH2, being the main component of the photocatalytic system, was stable as confirmed by the retention of its crystallinity in the PXRD pattern (Figures S3 and S4) and its high porosity even after 72 h of irradiation (Figure S14). This experiment highlights that while the molecular cocatalysts (Mo3S132–, Co-oxime,11 and others12,30) can have a very high activity, their stability over time is questionable and more robust molecular catalysts are needed for this reaction. On the other hand, although the NPs might have slightly lower catalytic performance, their durability is superior to the molecular ones.

Figure 3.

H2 generation from (a) Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 and (b) 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 after 6 cycles (12 h for each cycle).

In conclusion, we reported the synthesis and characterization of two molybdenum sulfide-based cocatalysts and studied their performance when combined with MIL-125-NH2 for visible-light driven photocatalytic H2 generation. The 1T-MoS2 not only possess high catalytic activity (the H2 evolution rate of 1T-MoS2/MIL-125-NH2 is only lower than the one of Mo3S132–/MIL-125-NH2 and significantly higher than any other reported values for visible-light responsive MOFs incorporated with a cocatalyst), but also maintains its performance for a long period of time. Since almost all recent new MOFs have been mostly combined with Pt NPs for photocatalytic testing, we believe that the easily synthesized 1T-MoS2 NPs can also be employed as one of the common cocatalysts for these prospective reactions.

Acknowledgments

T.N.N., S.K., and K.C.S. thank the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) for funding under the Ambizione Energy Grant no. PZENP2_166888. T.T.N. and K.C.S. are thankful to Materials’ Revolution: Computational Design and Discovery of Novel Materials (MARVEL), of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) for funding—DD4.5. The research of DO was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 666983, MaGic). Part of the calculations was enabled by the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS), under project ID s761. The authors thank Ms. Kun Zhao and Ms. Fatmah Mish Ebrahim for collecting the Raman and luminescence lifetime data, respectively.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsami.8b10010.

Experimental methods, synthetic procedures, and characterizations (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): We filed a patent application with some of the results presented in this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- Li H.; Wang K.; Sun Y.; Lollar C. T.; Li J.; Zhou H.-C. Recent Advances in Gas Storage and Separation Using Metal–Organic Frameworks. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 108–121. 10.1016/j.mattod.2017.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L.; Liu X.-Q.; Jiang H.-L.; Sun L.-B. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Heterogeneous Basic Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8129–8176. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig W. P.; Mukherjee S.; Rudd N. D.; Desai A. V.; Li J.; Ghosh S. K. Metal-organic Frameworks: Functional Luminescent and Photonic Materials for Sensing Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3242–3285. 10.1039/C6CS00930A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoedel A.; Ji Z.; Yaghi O. M. The Role of Metal–Organic Frameworks in a Carbon-neutral Energy Cycle. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16034. 10.1038/nenergy.2016.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fateeva A.; Chater P. A.; Ireland C. P.; Tahir A. A.; Khimyak Y. Z.; Wiper P. V.; Darwent J. R.; Rosseinsky M. J. A Water-Stable Porphyrin-Based Metal–Organic Framework Active for Visible-Light Photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 7558–7562. 10.1002/ange.201202471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyao T.; Saito M.; Horiuchi Y.; Mochizuki K.; Iwata M.; Higashimura H.; Matsuoka M. Efficient Hydrogen Production and Photocatalytic Reduction of Nitrobenzene over a Visible-light-responsive Metal-organic Framework Photocatalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 2092–2097. 10.1039/c3cy00211j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D.; Liu W.; Qiu M.; Zhang Y.; Li Z. Introduction of a Mediator for Enhancing Photocatalytic Performance via Post-synthetic Metal Exchange in Metal-organic Frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 2056–2059. 10.1039/C4CC09407G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S.; Qin J.-S.; Xu H.-Q.; Su J.; Rossi D.; Chen Y.; Zhang L.; Lollar C.; Wang Q.; Jiang H.-L.; Son D. H.; Xu H.; Huang Z.; Zou X.; Zhou H.-C. [Ti8Zr2O12(COO)16] Cluster: An Ideal Inorganic Building Unit for Photoactive Metal–Organic Frameworks. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 105–111. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-L.; Wang R.; Zhang M.-Y.; Yuan Y.-P.; Xue C. Dye-sensitized MIL-101 Metal Organic Frameworks Loaded with Ni/NiOx Nanoparticles for Efficient Visible-light-driven Hydrogen Generation. APL Mater. 2015, 3, 104403. 10.1063/1.4922151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L.; Tong Y.; Gu L.; Xue Z.; Yuan Y. MOFs as an Electron-transfer-bridge Between a Dye Photosensitizer and a Low cost Ni2P Co-catalyst for Increased Photocatalytic H2 Generation. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2018, 10.1039/C8SE00168E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasalevich M. A.; Becker R.; Ramos-Fernandez E. V.; Castellanos S.; Veber S. L.; Fedin M. V.; Kapteijn F.; Reek J. N. H.; van der Vlugt J. I.; Gascon J. Co@NH2-MIL-125(Ti): Cobaloxime-derived Metal-organic Framework-based Composite for Light-driven H2 Production. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 364–375. 10.1039/C4EE02853H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Xiao J.-D.; Jiang H.-L. Encapsulating a Co(II) Molecular Photocatalyst in Metal–Organic Framework for Visible-Light-Driven H2 Production: Boosting Catalytic Efficiency via Spatial Charge Separation. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5359–5365. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kampouri S.; Nguyen T. N.; Ireland C. P.; Valizadeh B.; Ebrahim F. M.; Capano G.; Ongari D.; Mace A.; Guijarro N.; Sivula K.; Sienkiewicz A.; Forro L.; Smit B.; Stylianou K. C. Photocatalytic hydrogen generation from a visible-light responsive metal-organic framework system: the impact of nickel phosphide nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 2476–2481. 10.1039/C7TA10225A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C. N. R.; Maitra U.; Waghmare U. V. Extraordinary Attributes of 2-dimensional MoS2 Nanosheets. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 609, 172–183. 10.1016/j.cplett.2014.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo T. F.; Jørgensen K. P.; Bonde J.; Nielsen J. H.; Horch S.; Chorkendorff I. Identification of Active Edge Sites for Electrochemical H2 Evolution from MoS2 Nanocatalysts. Science 2007, 317, 100–102. 10.1126/science.1141483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataca C.; Ciraci S. Dissociation of H2O at the Vacancies of Single-layer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2012, 85, 195410. 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.195410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen A. B.; Kegnaes S.; Dahl S.; Chorkendorff I. Molybdenum Sulfides-efficient and Viable Materials for Electro - and Photoelectrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 5577–5591. 10.1039/c2ee02618j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eda G.; Yamaguchi H.; Voiry D.; Fujita T.; Chen M.; Chhowalla M. Photoluminescence from Chemically Exfoliated MoS2. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5111–5116. 10.1021/nl201874w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F.; Hou Y.; Asiri A. M.; Wang X. Assembly of Protonated Mesoporous Carbon Nitrides with Co-catalytic [Mo3S13]2– Clusters for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 13221–13224. 10.1039/C7CC07805F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitra U.; Gupta U.; De M.; Datta R.; Govindaraj A.; Rao C. N. R. Highly Effective Visible-Light-Induced H2 Generation by Single-Layer 1T-MoS2 and a Nanocomposite of Few-Layer 2H-MoS2 with Heavily Nitrogenated Graphene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13057–13061. 10.1002/anie.201306918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibsgaard J.; Jaramillo T. F.; Besenbacher F. Building an Appropriate Active-site Motif into a Hydrogen-evolution Catalyst with Thiomolybdate [Mo3S13]2– Clusters. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 248. 10.1038/nchem.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendon C. H.; Tiana D.; Fontecave M.; Sanchez C.; D’arras L.; Sassoye C.; Rozes L.; Mellot-Draznieks C.; Walsh A. Engineering the Optical Response of the Titanium-MIL-125 Metal–Organic Framework through Ligand Functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10942–10945. 10.1021/ja405350u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Li X.; He Q.; Khalil A.; Liu D.; Xiang T.; Wu X.; Song L. Gram-Scale Aqueous Synthesis of Stable Few-Layered 1T-MoS2: Applications for Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Small 2015, 11, 5556–5564. 10.1002/smll.201501822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Zhang J.; Ao D. Construction of Heterostructured ZnIn2S4@NH2-MIL-125(Ti) Nanocomposites for Visible-light-driven H2 Production. Appl. Catal., B 2018, 221, 433–442. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Yu Y.; Li R.; Liu H.; Zhang W.; Ling L.; Duan W.; Liu B. Hydrogen Production with Ultrahigh Efficiency under Visible Light by Graphene Well-wrapped UiO-66-NH2 Octahedrons. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 20136–20140. 10.1039/C7TA06341E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes Silva C.; Luz I.; Llabrés i Xamena F. X.; Corma A.; García H. Water Stable Zr–Benzenedicarboxylate Metal–Organic Frameworks as Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 11133–11138. 10.1002/chem.200903526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; deKrafft K. E.; Lin W. Pt Nanoparticles@Photoactive Metal–Organic Frameworks: Efficient Hydrogen Evolution via Synergistic Photoexcitation and Electron Injection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7211–7214. 10.1021/ja300539p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T.; Du Y.; Borgna A.; Hong J.; Wang Y.; Han J.; Zhang W.; Xu R. Post-synthesis Modification of a Metal-organic Framework to Construct a Bifunctional Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Production. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3229–3234. 10.1039/c3ee41548a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toyao T.; Saito M.; Dohshi S.; Mochizuki K.; Iwata M.; Higashimura H.; Horiuchi Y.; Matsuoka M. Development of a Ru Complex-incorporated MOF Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Production under Visible-light Irradiation. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 6779–6781. 10.1039/c4cc02397h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P.; Jiang M.; Li Y.; Liu Y.; Wang J. Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production from Pure Water via a Photoactive Metal-organic Framework and Its PDMS@MOF. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 7833–7838. 10.1039/C7TA01070B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.