Abstract

While radiotherapy is a mainstay for cancer therapy, pneumonitis and fibrosis constitute dose-limiting side effects of thorax and whole body irradiation. So far, the contribution of immune cells to disease progression is largely unknown. Here we studied the role of ecto-5′-nucelotidase (CD73)/adenosine-induced changes in the myeloid compartment in radiation-induced lung fibrosis. C57BL/6 wild-type or CD73−/− mice received a single dose of whole thorax irradiation (WTI, 15 Gy). Myeloid cells were characterized in flow cytometric, histologic, and immunohistochemical analyses as well as RNA analyses. WTI induced a pronounced reduction of alveolar macrophages in both strains that recovered within 6 wk. Fibrosis development in wild-type mice was associated with a time-dependent deposition of hyaluronic acid (HA) and increased expression of markers for alternative activation on alveolar macrophages. These include the antiinflammatory macrophage mannose receptor and arginase-1. Further, macrophages accumulated in organized clusters and expressed profibrotic mediators at ≥25 wk after irradiation (fibrotic phase). Irradiated CD73−/− mice showed an altered regulation of components of the HA system and no clusters of alternatively activated macrophages. We speculate that accumulation of alternatively activated macrophages in organized clusters represents the origins of fibrotic foci after WTI and is promoted by a cross-talk between HA, CD73/adenosine signaling, and other profibrotic mediators.—De Leve, S., Wirsdörfer, F., Cappuccini, F., Schütze, A., Meyer, A. V., Röck, K., Thompson, L. F., Fischer, J. W., Stuschke, M., Jendrossek, V. Loss of CD73 prevents accumulation of alternatively activated macrophages and the formation of prefibrotic macrophage clusters in irradiated lungs.

Keywords: pulmonary fibrosis, adenosine, hyaluronan, pneumonitis, thorax irradiation

Radiation is a major treatment option for patients with cancer. However, normal lung tissue is highly sensitive to radiation-induced damage and has little repair capacity. As a consequence, radiation-induced pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis may develop in patients upon thoracic or total body irradiation, thereby reducing survival rates and quality of life (1, 2). No effective treatment is available for clinical use, so that these dose-limiting side effects are still a major barrier to successful radiotherapy of thorax-associated neoplasms (3, 4). Therefore there is high interest in defining involved cells and molecules as well as disease biomarkers. Deregulated cytokine production without or with aseptic lung inflammation is a frequent pathologic finding in patients after thoracic irradiation or total body irradiation and is also observed in murine models (4–8). However, so far, the role of immune cells in the pathogenesis of radiation-induced fibrosis is largely unknown (9).

We use whole thorax irradiation (WTI) of fibrosis-prone C57BL/6 mice with a single high dose of 15 Gy to study the role of radiation-induced immune changes in the pathogenesis of radiation-induced pneumonitis (3–12 wk after irradiation) and pulmonary fibrosis (≥25 wk after irradiation) (10–13). We showed that progressive activation of ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73, NT5E) and chronic accumulation of adenosine play an active role in the pathogenesis of radiation-induced lung fibrosis that can be counteracted by reducing extracellular adenosine accumulation through genetic (CD73−/− mice) or pharmacologic inhibition of CD73/adenosine signaling (13). CD73 and adenosine play critical roles in balancing tissue inflammation and repair processes regulating, among others, leukocyte extravasation and function (14–17). But depending on the disease model (acute or chronic), extracellular accumulation of adenosine has either protective or adverse effects in pulmonary fibrosis (13, 18–20). Because a pathogenic role of macrophages has been postulated for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and has been linked to a pathologic adenosine signaling (21, 22), we aimed to gain further insight into a potential role of CD73/adenosine for radiation-induced immune changes in radiation-induced lung fibrosis.

Various murine models of radiation-induced pneumopathy revealed an influx of myeloid cells during the pneumonitic phase and the fibrotic phase (13, 23, 24). This was associated with a significant increase in the levels of monocyte/macrophage-associated cytokines and chemokines in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid compared to sham-treated controls (10). Moreover, several reports suggested a potential role of foamy macrophages or alternatively activated macrophages in radiation-induced adverse late effects, though the responses may depend on the mouse strain (10, 24–26).

Generally, mononuclear phagocytes participate in orchestrating innate and adaptive immune responses and thereby play essential roles in inflammation and host defense against infections. But they also exert homeostatic functions in diverse tissues and coordinate remodeling after injury or within the tumor environment (27). Their high plasticity allows macrophages to adapt quickly to various environmental signals such as those from lymphocyte subsets or danger signals in injured tissues (28). Macrophages were initially classified into classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) populations executing predominantly proinflammatory or antiinflammatory actions, respectively (29). However, it is now clear that macrophages can adopt various phenotypes as a continuum in between the M1/M2 extremes, including mixed M1/M2 phenotypes under pathologic conditions (30), and that the various phenotypes have tissue- and context-dependent functions (31, 32).

Extracellular matrix molecules such as collagens, fibronectin, and the glycosaminoglycan hyaluronan (hyaluronic acid, HA) that accumulate in fibrotic tissues including radiation-induced fibrosis (33) participate in the regulation of chronic lung inflammation and fibrosis (34, 35). Moreover, interactions between the HA system, particularly low-molecular-weight HA, and adenosine signaling through 2 [adenosine receptor (ADOR) A2A and ADORA2B] of its 4 receptors as well as between low-molecular-weight HA and macrophages (34–37) are well documented.

So far, not much is known about the regulation of macrophage phenotype in the changing environment of irradiated lungs and their impact on radiation-induced lung fibrosis. Thus, we studied radiation-induced changes in the macrophage compartment and the impact of altered CD73/adenosine signaling on macrophage behavior in CD73-deficient mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 wild-type (WT; CD73+/+; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and CD73−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) (15) were bred and housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions in the animal facilities laboratory of the University Hospital Essen. Food and drinking water were provided ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the universities’ animal protection boards in conjunction with the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz Nordrhein-Westfalen according to German animal welfare regulations (AZ.8.87-51.04.20.09.333, AZ.84-02.04.2011.A407).

Irradiation

Mice (8–12 wk old) were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and irradiated in 0.8% isoflurane with either a single dose of 0 Gy (sham control treatment) or with 15 Gy over their whole thorax (WTI) using a cobalt-60 source (Philips, Hamburg, Germany) (12). Mice were humanely killed at 3, 6, 12, 24, or 25 to 30 wk after irradiation, and lung tissue was collected.

Lung leukocyte phenotyping

Total lung cells were isolated as previously described (12) and stained with anti-mouse CD45 PacificBlue (30-F11) to identify total leukocytes. Myeloid cells were defined with anti-CD11b PerCP-Cy5.5 (M1/70), macrophages were defined with anti-F4/80 PE-Cy7 (BM8), and alveolar macrophages (AMs) were defined with anti-CD11c BV (N418) and increased FL-1 autofluorescence according to standard practice (38, 39). Populations were further characterized with anti–major histocompatibility complex II (MHCII) APC (M5/114.15.2), used as a M1 macrophage marker, and anti–macrophage mannose receptor (MMR) PE (C068C2), used as a M2 macrophage marker (40, 41). Antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA), BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA), or eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Data acquisition and analysis were performed on a LSRII device using FACS DIVA (BD Biosciences).

RNA isolation

Fresh frozen lung tissue was pulverized, lysed in RLT buffer (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), and sonicated with an Ultraturrax IKA T10 (IKA, Staufen, Germany) for 30 s. RNA was further isolated using the homogenizer QiaShredder and RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was reverse transcribed with the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen), and quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out using specific oligonucleotide primers: β-actin (Actb): forward, 5′–CCAGAGCAAGAGAGGTATCC–3′; reverse, 5′–CTGTGGTGGTGAAGCTGTAG–3′; iNOS (Nos2): forward, 5′–AGCTCCTCCCAGGACCACAC–3′; reverse, 5′–ACGCTGAGTACCTCATTGGC–3′; arginase-1 (ARG1, Arg1): forward, 5′–GTGAAGAACCCACGGTCTGT–3′; reverse, 5′–CTCGCAAGCCAATGTACACG–3′; IL-10Rα (Il10ra): forward, 5′–AGGCAGAGGCAGCAGGCCCAGCAGAATG–3′; reverse, 5′–TGGAGCCTGGCTAGCTGGTCACAGTAGG–3′; hyaluronan synthase 3 (Has3, Has3): forward, 5′–GATGTCCAAATCCTCAACAAG–3′; reverse, 5′–CCCACTAATACATTGCACAC–3′; CD44 (Cd44): forward, 5′–AGGATGACTCCTTCTTTATCCG; reverse, 5′–CTTGAGTGTCCAGCTAATTCG–3′; hyaluronan-mediated motility receptor (RHAMM, Hmmr): forward, 5′–GAATATGAGAGCTCTAAGCCTG–3′; reverse 5′–CCATCATACTCCTCATCTTTGTC–3′, using qPCR MasterMix for SYBR Assay Rox (Eurogentec, Cologne, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene expression levels were normalized to β-actin (set as 1).

Histopathology

Paraffin-embedded tissue

Lungs were perfused (with PBS) and then fixed overnight with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.2). Upon dehydration, lungs were embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 5-µm slices.

Immunohistochemistry

iNOS (NOS2), ARG1 (ARG1), TGF-β (TGFB1), α-SMA (ACTA2)

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of paraffin-embedded lung tissue was performed using the Mouse on Mouse (M.O.M.) ImmPress HRP (horseradish peroxidase) Polymer Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Anti-iNOS (BD Biosciences), anti-ARG1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-TGF-β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) were used as mouse primary antibodies. The ImmPACT VIP Peroxidase (HRP) Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories) was used to detect primary antibodies according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stained sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Macrophage-3 antigen (Mac-3, LAMP2)

Paraffin was removed from the tissue slides; the samples were rehydrated and steam boiled in citrate buffer (pH 6). After blocking endogenous peroxidase with 3% H2O2, sections were blocked for 20 min with 2% normal goat serum and subsequently incubated with anti-Mac-3 antibody (BioLegend) overnight at 4°C. Mac-3 was detected by secondary antibody linked to HRP and subsequent diaminobenzidine staining.

Affinity histochemistry

To assess biotinylated HA binding protein (HABP), paraffin was removed from tissue slides; they were then rehydrated, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2. Affinity histochemistry of HA was performed by incubating biotinylated HABP overnight (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan), and further detection was performed using HRP-labeled streptavidin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) and subsequent diaminobenzidine staining.

Immunofluorescence

For ARG1/Mac-3 double staining, immunofluorescence staining of paraffin-embedded lung tissue was performed using the Mouse On Mouse (M.O.M.) Immunodetection, or Basic Kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue sections were incubated with anti-ARG1 antibodies overnight at 4°C. Anti-ARG1 was detected using a secondary anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Slides were then blocked with 2% normal goat serum and incubated with anti-Mac-3 antibody overnight at 4°C. Anti-Mac-3 was detected using a secondary anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). For normalization, sham-treatment control values were set to 100% or 1, and values for irradiated animals were depicted as a percentage of sham-treated controls or relative to controls. Student’s 2-tailed, unpaired Student's t tests were used to compare differences between 2 groups. One-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare more than 2 groups. Two-way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare groups split on 2 independent variables. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

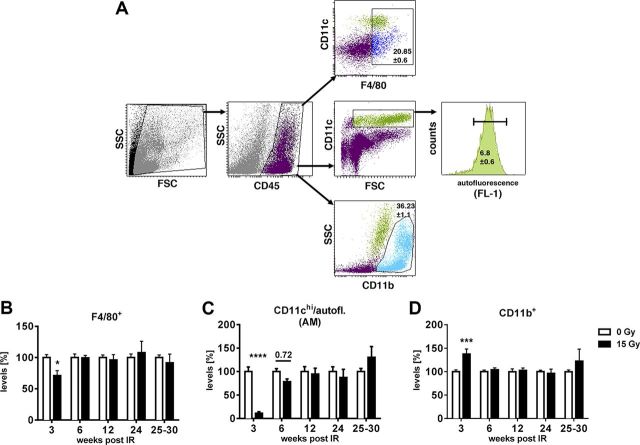

Thorax irradiation triggers early loss of pulmonary macrophages and influx of CD11b+ cells

To study the macrophage response in irradiated lungs, we exposed mice to WTI with a single dose of 15 or 0 Gy (sham control treatment) and dissected the lung tissue for flow cytometric analysis at different time points. Total macrophages were gated on the basis of CD45 and F4/80 staining (Fig. 1A, top). AMs were identified by a gating strategy developed by Vermaelen and Pauwels (38) for distinguishing AMs (CD45+CD11chigh autofluorescent cells) from pulmonary dendritic cells (CD45+CD11chigh nonautofluorescent) (Fig. 1A, middle). In nonirradiated mice, the proportion of F4/80+ pulmonary macrophages from CD45+ leukocytes was 20.9 ± 0.6%, while the percentage of AMs was 6.8 ± 0.6%.

Figure 1.

WTI triggers early loss of pulmonary macrophages and compensatory influx of CD11b+ cells. WT mice received 0 or 15 Gy WTI and were humanely killed at indicated time points after irradiation. Whole lung cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. A) Gating strategy for F4/80+ macrophages, AMs [CD11c+ and high autofluorescence (38)] and CD11b+ cells from CD45+ cells, shown for nonirradiated sample. B–D) Relative percentages of F4/80+ cells (B; n = 7/7, 6/7, 6/6, 6/5, and 8/2 at indicated time points), AMs (C, n = 7/7, 6/7, 6/6, 6/5 and 11/8), and CD11b+ cells (D; n = 7/7, 6/7, 6/6, 6/6 and 8/2) normalized to nonirradiated controls. Shown are means ± sem (B–D). Adjusted P = 0.72 (C). *P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001 by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

WTI led to a significant reduction in the percentage of F4/80+ macrophages (Fig. 1B) and almost complete eradication of AMs at 3 wk after irradiation (Fig. 1C). The loss in pulmonary macrophages was accompanied by a significant increase in CD11b+ monocytic cells (Fig. 1D) compared to nonirradiated control mice (36.2 ± 1.1% on average; Fig. 1A, bottom). Of note, macrophage levels recovered at 6 wk after irradiation (Fig. 1B, C).

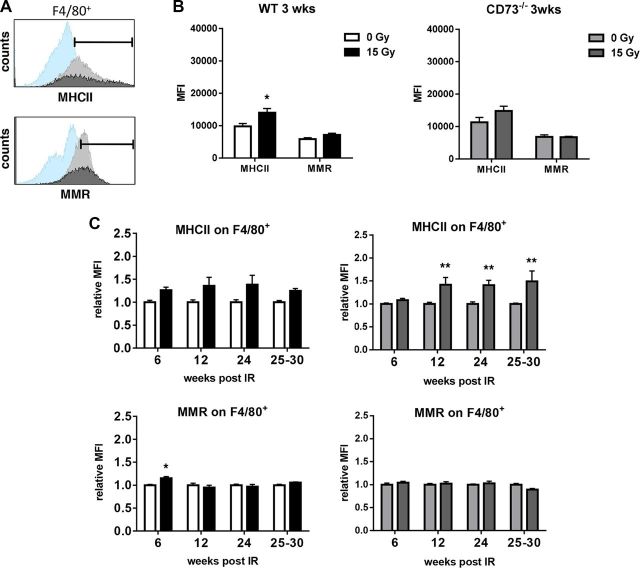

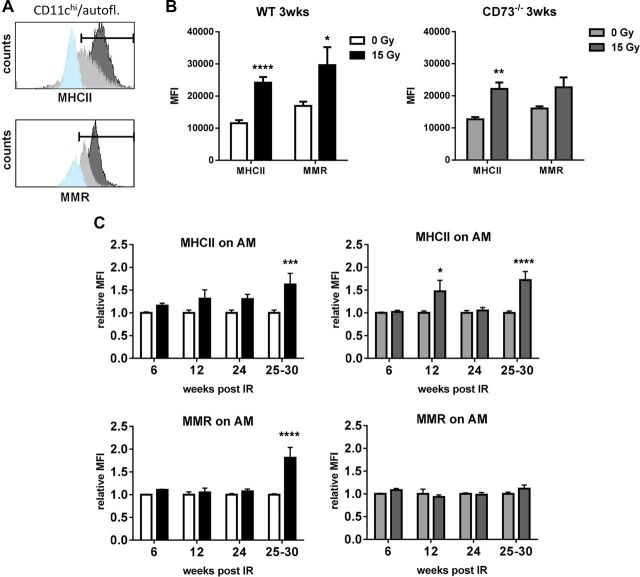

Loss of CD73 prevents radiation-induced alterations in macrophage phenotype during fibrotic phase

Earlier work suggested fibrosis-associated changes in the macrophage phenotype in irradiated lungs (10, 25). Moreover, chronic adenosine accumulation had been linked to alternative macrophage activation and pulmonary fibrosis in other models (22, 42, 43). Therefore, we next investigated whether we could find time-dependent changes in the phenotype of pulmonary macrophages in irradiated WT mice and whether WT and CD73−/− mice would differ in their macrophage response to WTI. We used MHCII as a flow cytometry marker for a proinflammatory phenotype (44) and MMR as a marker for alternative activation (40) of F4/80+ macrophages (Fig. 2A) and AMs (Fig. 3A), respectively.

Figure 2.

WTI triggers delayed increase in MHCII on F4/80+ lung macrophages in CD73−/− mice. WT or CD73−/− mice received 0 or 15 Gy WTI and were humanely killed at indicated time points after irradiation. Whole lung cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. A) Histograms show representative samples (isotype control in light blue, 0 Gy in light gray, 15 Gy in dark gray) for MHCII and MMR for F4/80+ macrophages. Indicated area was used for quantification. B) At 3 wk, F4/80+ macrophages were characterized for their expression of MHCII or MMR in WT and CD73−/− mice. Shown are MFIs (n = 7). C) Relative MFI of MHCII and MMR for F4/80+ macrophages (n = 6/7, 6/6, 6/5 and 8/2 for WT, n = 7/7, 6/5, 6/6 and 7/3 for CD73−/−) at indicated time points; means ± sem. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 by unpaired, 2-tailed Student’s t test (B) or by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (C).

Figure 3.

WTI induces expression of MMR on AMs of WT mice during fibrotic phase. WT or CD73−/− mice received 0 or 15 Gy WTI and were humanely killed at indicated time points after irradiation. Whole lung cells were stained and further analyzed by flow cytometry. A) Histograms show representative samples (isotype control in light blue, 0 Gy in light gray, 15 Gy in dark gray) of MHCII or MMR stainings for AMs. Indicated area was used for quantification. B) At 3 wk, AMs were characterized for their expression of MHCII or MMR in WT and CD73−/− mice. Shown are MFIs (n = 7). C) Relative MFI of MHCII and MMR for AMs (n = 6/7, 6/6, 6/5 and 12/6 for WT, n = 6/7, 6/5, 6/6 and 10/7 for CD73−/−) at indicated time points; means ± sem. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001 by unpaired, 2-tailed Student’s t test (B) or by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (C).

WT and CD73−/− mice showed similar responses to irradiation with respect to the fraction of F4/80+ macrophages and AMs among CD45+ cells (data not shown). Moreover, nonirradiated WT mice and CD73−/− mice expressed MHCII and MMR on F4/80 macrophages and AMs with similar mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (Figs. 2B and 3B). WTI triggered a slight increase in MHCII on F4/80+ macrophages that was significant in WT mice at 3 wk after irradiation (Fig. 2B, top left) and in CD73−/− mice at later time points (Fig. 2C, top right). However, MMR expression levels remained unchanged in irradiated F4/80+ macrophages throughout the observation period (Fig. 2C, bottom). Overall, expression of the investigated marker proteins of pulmonary F4/80+ macrophages in response to radiation was similar in both strains.

WTI also triggered a pronounced increase in MHCII expression on AMs of WT and CD73−/− mice, particularly during the acute inflammatory phase (3 wk after irradiation) and the fibrotic phase (30 wk after irradiation), known to be associated with chronic inflammation (Fig. 3B, C, top). Importantly, WTI triggered a strong increase in expression of MMR in WT mice during the fibrotic phase (Fig. 3C, bottom left). In contrast, no up-regulation of MMR could be detected in CD73−/− mice (Fig. 3C, right). These findings suggest that AMs of irradiated WT mice undergo a phenotypic change toward an alternatively activated phenotype during the fibrotic phase, whereas no such change can be observed in CD73−/− mice.

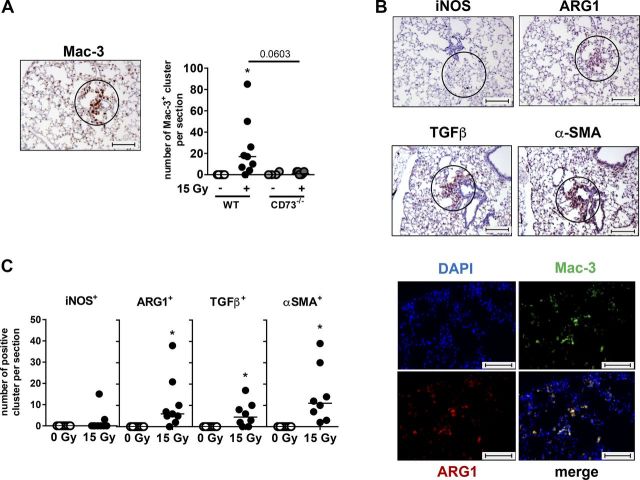

Loss of CD73 prevents the accumulation of alternatively activated macrophages with profibrotic phenotype in organized clusters

To corroborate our findings about the differences in macrophage activation of irradiated WT mice, we performed a detailed IHC analysis of tissues collected during the fibrotic phase (Fig. 4). One interesting observation was that in WT mice, macrophages accumulated during the fibrotic phase in organized clusters (Fig. 4A). Of note, these macrophage clusters were associated with a pronounced expression of ARG1, another marker for alternatively activated macrophages (25), and of the profibrotic markers TGF-β and α-SMA (Fig. 4B, C), respectively. In contrast, expression of the proinflammatory marker iNOS was only rarely detected in these clusters. Double-staining of tissue sections with Mac-3 and ARG1 confirmed a specific localization of ARG1 to macrophages (Fig. 4B, bottom). Importantly, CD73−/− mice failed to develop organized clusters of pulmonary macrophages expressing profibrotic markers at 25 to 30 wk after irradiation (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Alternatively activated macrophages form clusters in lung tissue of WT mice and have profibrotic phenotype. WT or CD73−/− mice received 0 or 15 Gy WTI and were humanely killed at 25–30 wk after irradiation. A) IHC staining of paraffin-embedded lung tissue with primary antibody for Mac-3 was performed to identify macrophages and macrophage clusters per section. Numbers of clusters are shown in scatter plot (horizontal line indicates median). B) Top panels: representative IHC pictures (from irradiated WT samples) for macrophage clusters stained with iNOS, ARG1, TGF-β, or α-SMA primary antibody are shown (circles indicate macrophage clusters). Bottom panels: immunofluorescence double staining for Mac-3 and ARG1. Double staining results in yellow signal. C) Quantification of evaluated macrophage clusters from IHC stainings of WT mice for indicated markers in scatter plots (horizontal line indicates median). *P ≤ 0.05, by 1-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (A) or by unpaired, 2-tailed Student’s t test (C). Scale bars, 100 µm.

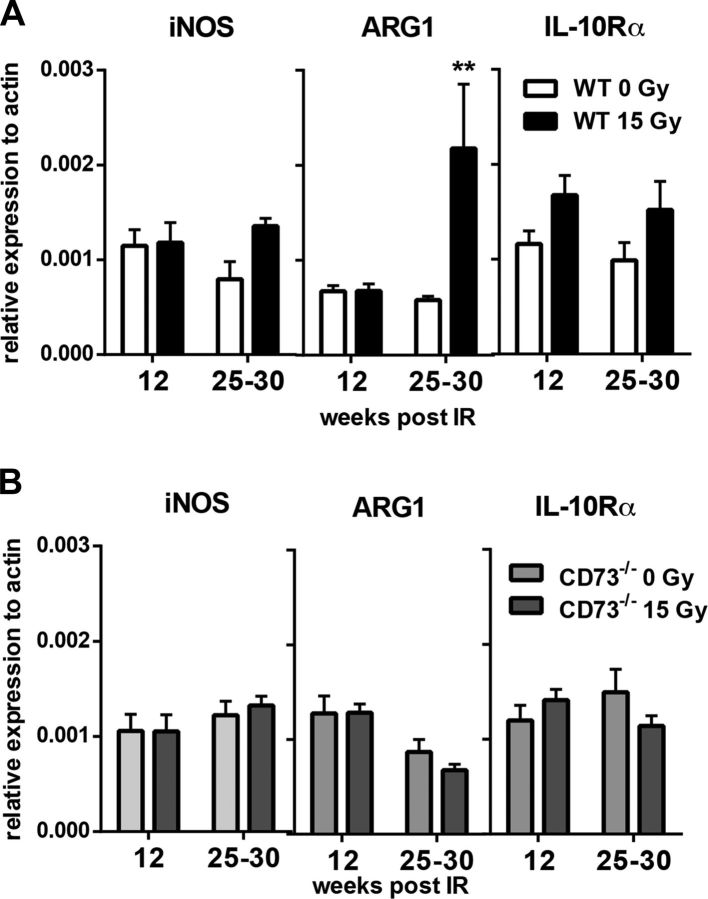

qPCR analyses of whole lung tissue RNA samples confirmed the increase in ARG1 expression in WT mice, specifically at 30 wk after irradiation but not at earlier time points, whereas expression of iNOS and IL-10Rα was not significantly altered during the fibrotic phase (Fig. 5A). In contrast, no radiation-induced changes in the expression of these mediators were observed in whole lung tissue RNA samples of irradiated CD73−/− mice at these time points (Fig. 5B). These findings corroborate the failure of CD73−/− mice to respond to WTI with the accumulation of alternatively activated macrophages during the fibrotic phase.

Figure 5.

WTI triggers up-regulated expression of ARG1 only in lung tissue of WT mice. WT or CD73−/− mice received 0 or 15 Gy WTI and were humanely killed at indicated time points after irradiation. A) qPCR analysis for iNOS (n = 8/7 and 8/7), ARG1 (n = 8/8 and 7/7), and IL-10Rα (n = 8/8 and 8/8) from whole tissue RNA from WT mice. B) qPCR analysis for iNOS (n = 9/10 and 10/10), ARG1 (n = 9/10 and 10/10), and IL-10Rα (n = 10/9 and 10/10) from whole tissue RNA samples from CD73−/− mice; means ± sem. **P ≤ 0.01, by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

CD73 deficiency affects HA signaling pathway

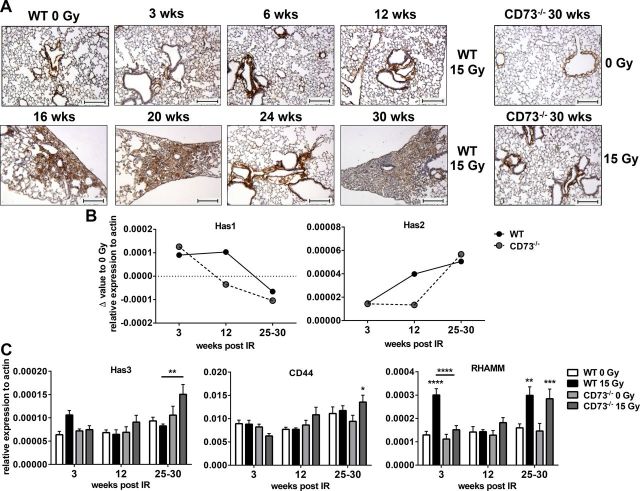

So far, our data suggested that the pathogenesis of radiation-induced lung fibrosis involves an accumulation of AMs in organized clusters and a CD73/adenosine-dependent alteration in AMs toward an alternatively activated phenotype. Our previous work revealed an increased deposition of HA in WT mice during the fibrotic phase (33). Since earlier reports suggested a link between adenosine signaling and the HA system (35, 37), we were interested in potential differences in the HA system in irradiated WT and CD73−/− mice. Affinity histochemical staining for HABP corroborated the accumulation of HA within the fibrotic areas (Fig. 6A). A detailed analysis of the time course of HA accumulation revealed that HA deposition became visible in irradiated WT mice at 16 to 20 wk (Fig. 6A). Of note, no histologically detectable HA positive fibrotic foci were observed in the CD73−/− mice (Fig. 6A, right).

Figure 6.

WTI induces different pattern of HA signaling in WT and CD73−/− mice. WT or CD73−/− mice received 0 or 15 Gy WTI and were humanely killed at indicated time points after irradiation. A) Representative IHC stainings with HABP of 0- or 15-Gy-irradiated WT and CD73−/− animals. Scale bars, 100 µm. B) qPCR analyses for Has1 and Has2 from whole tissue RNA samples at indicated time points after irradiation (2 technical replicates from pooled samples per time point as Δ values from 15- vs. 0-Gy-treated lungs; shown as mean). C) qPCR analyses for Has3 (n = 10/9/6/6; 7/8/9/10; 7/8/10/10), CD44 (n = 10/9/6/6; 7/7/8/10; 8/8/10/10), and RHAMM (n = 10/9/6/6; 7/8/9/10; 8/8/10/10) from whole tissue RNA samples at indicated time points after irradiation (means ± sem). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, by 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Next we examined whether the time-dependent changes in HA abundance in irradiated lungs of WT mice and the differences between WT and CD73−/− mice correlate to radiation-induced differences in the regulation of genes of the HA pathway (Fig. 6B, C). Has1 and -2 mRNA expression in whole lung tissue underwent reciprocal changes after ionizing radiation in both WT and CD73−/− animals (Fig. 6B). While Has1 levels declined over time until the fibrotic phase, Has2 underwent a time-dependent up-regulation after irradiation, with the highest levels observed in the fibrotic phase. Interestingly, at the 12-wk time point, and thus just before the onset of visible HA deposition in WT mice, Has1 and Has2 expression were increased in WT compared to CD73−/− mice, whereas they reached similar levels in both mouse strains during the fibrotic phase (Fig. 6B).

Has3 was up-regulated at the 3-wk time point in the lungs of irradiated WT animals and declined throughout the observation period; in contrast, in CD73−/− mice Has3 expression was low at the 3-wk time point but showed a significant increase during the fibrotic phase (Fig. 6C). This was paralleled by a comparable time course in the expression of the HA receptors CD44 and RHAMM in CD73−/− mice (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the expression of CD44 remained almost unchanged in WT mice, whereas the expression of RHAMM displayed a dual increase at the 3- and 30-wk time points in these mice (Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate for the first time that thorax irradiation of fibrosis-prone C57BL/6 mice induced the generation of AMs with an alternatively activated phenotype and their accumulation in organized clusters expressing fibrotic marker proteins during the fibrotic phase. Genetic deficiency of CD73 abrogated both the radiation-induced acquisition of phenotypic markers of alternative activation in AMs and the formation of organized macrophage clusters. Reduced pulmonary fibrosis in CD73−/− mice was also accompanied by specific differences in the expression of genes of the HA system and reduced HA deposition in the lung tissue compared to WT mice. We conclude that radiation-induced activation of the CD73/adenosine and HA pathways cooperate in promoting pulmonary fibrosis by driving the formation of macrophage clusters and the acquisition of an alternatively activated, profibrotic phenotype.

In detail, the percentage of pulmonary macrophages, particularly AMs, declined during the first weeks after WTI in WT mice, which is consistent with findings by others (26). This was paralleled by an increased influx of CD11b+ myeloid cells. This myeloid cell population is known to contain macrophage precursors (10, 45). We therefore speculate that radiation-induced tissue damage and the resulting increase in monocyte chemoattractants triggers the influx of myeloid cells into the lung tissue to replace the depleted tissue-resident macrophages. Accordingly, we observed a reconstitution of F4/80+ macrophages and AMs about 6 wk after irradiation that was accompanied by a normalization of CD11b+ cell levels. In line with our observations, bone marrow–derived cells replaced eradicated AMs in unshielded murine lungs around 6 wk after total body irradiation (46).

Flow cytometry–based macrophage phenotyping revealed that expression of MHCII and MMR on F4/80+ macrophages was rather similar in nonirradiated and irradiated lungs in WT and CD73−/− mice. In contrast, WTI triggered a pronounced up-regulation of MMR on AMs only in irradiated WT but not in irradiated CD73−/− mice. The presence of macrophages with an alternatively activated phenotype in fibrotic lungs of WT mice was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining with ARG1. Thus, we suggest that pulmonary fibrosis in WT mice is associated with the generation of alternatively activated AMs and that CD73-dependent adenosine accumulation participates in this process. Our findings corroborate earlier reports on the fibrosis-associated generation of alternatively activated macrophages in murine lungs upon thoracic irradiation (25, 26), though different radiation doses, time points, markers, and gating strategies were used to identify pulmonary macrophages. A contribution of alternatively activated macrophages to bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice and other fibrotic diseases has already been reported (22, 47–49). However, their participation in radiation-induced fibrotic disease is still controversial. In one study, macrophages expressing M2-like markers have been linked to disease outcome in radiation-induced renal fibrosis (50). Instead, an accumulation of T cells and no role for macrophages (51) or a contribution of macrophages had been observed in radiation-induced skin fibrosis (30, 52), but without stating the macrophage phenotype.

In our hands, the generation of alternatively activated macrophages in irradiated lungs was associated with their accumulation in organized clusters. This is reminiscent of findings in the rat model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis where organized macrophage clusters were observed at d 7 and 14 after intratracheal bleomycin injection (53). Furthermore, focal lesions containing numerous macrophages were observed in lungs of irradiated C57L/J mice, but already at 8 wk after irradiation (54). A strong association between organized macrophage clusters in the lung and fibrosis development was also reported in a model of targeted type 2 alveolar epithelial cell injury (55). Similarly, the formation of focal lesions containing TGF-β-positive fibroblasts has been described upon single-dose thoracic irradiation (15 Gy) in C57BL/6 mice, but not in fibrosis-resistant C3HeB/FeJ mice (56). In the present study, we now demonstrate that organized macrophage clusters are exclusively present in WT mice and strongly express profibrotic mediators, suggesting a role for cluster-forming, alternatively activated macrophages, presumably AMs, in radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis.

So far, the role of macrophages in radiation-induced pneumopathy and the molecular networks involved in their regulation remained elusive. Here we show for the first time that in irradiated CD73−/− mice, macrophages fail to organize into clusters and AMs do not up-regulate markers for alternative activation such as MMR and ARG1. Together with our earlier findings on the pathogenic role of CD73 and adenosine in radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis (13), our new observations reveal a role for CD73-dependent adenosine accumulation in driving the altered phenotype in macrophages. This is consistent with earlier reports demonstrating a role of adenosine in down-modulating classic activation and promoting alternative activation of macrophages in vitro involving ADORA2A and ADORA2B (14, 42, 57–60). Furthermore, our new findings hint to a potential contribution of alternatively activated AMs in promoting radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis, though the functional relevance of macrophages has to be confirmed by macrophage depletion experiments.

Suggested mechanisms of the profibrotic actions of pulmonary macrophages involve overproduction of reactive oxygen species as well as generation and activation of profibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β (29, 61). Comparative transcriptome analysis of lung tissue from fibrosis-prone and fibrosis-resistant mice exposed to thoracic irradiation revealed differences in the expression of signaling molecules associated with immune activation (62, 63). Accordingly, we observed up-regulated mRNA and protein levels of TGF-β and osteopontin upon WTI only in the lung tissue of WT mice, whereas the levels of these clinically relevant fibrotic markers were lower in the lungs of CD73−/− mice (13). Because TGF-β can induce alternative macrophage activation (64, 65), we speculate that TGF-β may cooperate with adenosine in driving the alterations in the macrophage phenotype in irradiated lungs during the fibrotic phase. Furthermore, macrophages can produce osteopontin-induced downstream of ADORA2B signaling (66).

Interestingly, the specific knockout of ADORA2B on myeloid cells (LysMCre) reduced adenosine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, reduced the numbers of alternatively activated macrophages, and reduced α-SMA+ fibroblasts and bleomycin-induced fibrosis (22). Moreover, CD73 and ADORA2B were up-regulated in lung biopsy samples from patients with stage 4 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or severe idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, respectively, with their expression particularly confined to alternatively activated pulmonary macrophages (47). These findings highlight a role of CD73 activation, adenosine accumulation, and ADORA2B activation in driving the accumulation of alternatively activated macrophages and fibrotic pulmonary disease in patients. Consistent with these findings, we observed in preliminary experiments that WTI induces up-regulated expression of ADORA2B in lung tissue of WT mice during the fibrotic phase but not in the lung tissue of CD73-knockout mice (data not shown). But the role of specific adenosine receptors in mediating the pathogenic role of adenosine in radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis remains to be defined in future studies by using the respective knockout mice.

Of note, the role of adenosine and its receptors in fibrotic disease in vivo seems to largely depend on the tissue and the model investigated. Earlier reports revealed a critical role of ADORA2A signaling in dermal fibrosis induced, for example, by genetic loss of adenosine deaminase, systemic administration of bleomycin, and ionizing radiation, whereas ADORA2B activation was shown to play a major pathogenic role in the related models of pulmonary fibrosis (35, 51, 67, 68). These differences might be due to tissue-specific expression patterns of adenosine receptors or other fibrosis-modulating signaling molecules in resident cells or recruited immune cells, tissue-specific damage responses, or both (67, 68). However, the models of radiation-induced fibrosis in the lung and the skin also differ in the radiation dose (15 Gy in the lung vs. 35–40 Gy in the skin) and the time course (weeks vs. months). Thus, some differences in radiation-induced dermal and pulmonary fibrosis may well be due to differences in the damage model, which is reminiscent of the differences between the acute and chronic models of bleomycin-induced lung injury (19, 20).

We also identified the HA pathway as another important modulator of radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis, presumably through an interaction with the CD73/adenosine-pathway: HA deposition occurred only in irradiated WT but not in CD73−/− mice. Furthermore, HA deposition in WT lungs was observed at 16 to 20 wk after irradiation, and thus in parallel to the chronic accumulation of adenosine but before the occurrence of histologically detectable fibrosis described earlier (13). Interestingly, the differences in HA deposition between irradiated WT and CD73−/− mice were associated with differences in the expression of HA synthases (Has). At the critical 12-wk time point that represents the onset of adenosine accumulation (13), Has1 and 2 displayed increased expression in WT compared to CD73−/− mice. These observations corroborate the suggested link between the adenosine and HA pathways in regulating tissue inflammation and fibrosis in other murine models and for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (35, 37). However, expression of Has2 reached similar levels in irradiated WT and CD73−/− mice during the fibrotic phase. The failure of irradiated CD73−/− mice to chronically accumulate adenosine may thus abrogate the profibrotic signaling loop involving adenosine, Has2, and TGF-β in WT mice, thereby limiting fibrosis development. Instead, Has3 was up-regulated during the fibrotic phase only in the CD73−/− mice. Unlike Has1 and 2, Has3 mainly synthesizes low-molecular-weight HA with reported proinflammatory actions (69, 70). Activation of the proinflammatory arm of the HA pathway during the fibrotic phase may thus help the CD73−/− mice to limit fibrosis development (e.g., through activating extracellular matrix–degrading enzymes) (51).

Taken together, our results point to a pathogenic role for the accumulation of alternatively activated macrophages in prefibrotic clusters in radiation-induced lung fibrosis. Reduced extracellular adenosine accumulation in CD73−/− mice prevented macrophages from accumulating in organized clusters, undergoing phenotypic alterations, and expressing profibrotic markers in irradiated lungs. Thus, radiation-induced increases in adenosine and HA may cooperate with TGF-β in driving macrophage recruitment, organization in prefibrotic clusters, up-regulation of alternative activation, and fibrosis progression. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of the signaling networks driving polarized macrophage activation and fibrosis in the irradiated lung and may allow us to define new diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for dose-limiting adverse effects of thorax irradiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank M. Groneberg and E. Gau (both from the University Hospital Essen) for excellent technical support. The work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; Grants GRK1739/1 and JE275/4-1 to V.J.), and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF; Grant 02NUK024D to V.J.).

Glossary

- ADOR

adenosine receptor

- α-SMA

α smooth muscle actin

- AM

alveolar macrophage

- ARG1

arginase-1

- CD73

ecto-5′-nucelotidase

- HA

hyaluronic acid

- HABP

hyaluronan binding protein

- Has

hyaluronan synthase

- Hmmr

hyaluronan-mediated motility receptor (RHAMM)

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IHC

immunohistochemical

- Mac-3

macrophage-3 antigen

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MHCII

major histocompatibility complex II

- MMR

macrophage mannose receptor

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- RHAMM

hyaluronan-mediated motility receptor (Hmmr)

- WT

wild type

- WTI

whole thorax irradiation

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S. de Leve and F. Wirsdörfer designed research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the article; F. Cappuccini performed experiments and evaluated data; A. V. Meyer, A. Schütze, and K. Röck performed experiments; L. F. Thompson wrote and critically reviewed the article; J. W. Fischer and M. Stuschke discussed data and critically reviewed the article; and V. Jendrossek designed research, and wrote and critically reviewed the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kong F. M., Ten Haken R., Eisbruch A., Lawrence T. S. (2005) Non–small cell lung cancer therapy–related pulmonary toxicity: an update on radiation pneumonitis and fibrosis. Semin. Oncol. (2, Suppl 3)S42–S54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelsey C. R., Horwitz M. E., Chino J. P., Craciunescu O., Steffey B., Folz R. J., Chao N. J., Rizzieri D. A., Marks L. B. (2011) Severe pulmonary toxicity after myeloablative conditioning using total body irradiation: an assessment of risk factors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. , 812–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begg A. C., Stewart F. A., Vens C. (2011) Strategies to improve radiotherapy with targeted drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer , 239–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graves P. R., Siddiqui F., Anscher M. S., Movsas B. (2010) Radiation pulmonary toxicity: from mechanisms to management. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. , 201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arpin D., Perol D., Blay J. Y., Falchero L., Claude L., Vuillermoz-Blas S., Martel-Lafay I., Ginestet C., Alberti L., Nosov D., Etienne-Mastroianni B., Cottin V., Perol M., Guerin J. C., Cordier J. F., Carrie C. (2005) Early variations of circulating interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 levels during thoracic radiotherapy are predictive for radiation pneumonitis. J. Clin. Oncol. , 8748–8756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin P., Johnston C. J., Williams J. P., McDonald S., Finkelstein J. N. (1995) A perpetual cascade of cytokines postirradiation leads to pulmonary fibrosis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. , 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston C. J., Wright T. W., Rubin P., Finkelstein J. N. (1998) Alterations in the expression of chemokine mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and -sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Exp. Lung Res. , 321–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong Z. Y., Song K. H., Yoon J. H., Cho J., Story M. D. (2015) An experimental model–based exploration of cytokines in ablative radiation-induced lung injury in vivo and in vitro. Lung , 409–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wirsdörfer F., Jendrossek V. (2016) The role of lymphocytes in radiotherapy-induced adverse late effects in the lung. Front. Immunol. , 591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappuccini F., Eldh T., Bruder D., Gereke M., Jastrow H., Schulze-Osthoff K., Fischer U., Kohler D., Stuschke M., Jendrossek V. (2011) New insights into the molecular pathology of radiation-induced pneumopathy. Radiother. Oncol. , 86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eldh T., Heinzelmann F., Velalakan A., Budach W., Belka C., Jendrossek V. (2012) Radiation-induced changes in breathing frequency and lung histology of C57BL/6J mice are time- and dose-dependent. Strahlenther. Onkol. , 274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wirsdörfer F., Cappuccini F., Niazman M., de Leve S., Westendorf A. M., Lüdemann L., Stuschke M., Jendrossek V. (2014) Thorax irradiation triggers a local and systemic accumulation of immunosuppressive CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Radiat. Oncol. , 98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wirsdörfer F., de Leve S., Cappuccini F., Eldh T., Meyer A. V., Gau E., Thompson L. F., Chen N. Y., Karmouty-Quintana H., Fischer U., Kasper M., Klein D., Ritchey J. W., Blackburn M. R., Westendorf A. M., Stuschke M., Jendrossek V. (2016) Extracellular adenosine production by ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) enhances radiation-induced lung fibrosis. Cancer Res. , 3045–3056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haskó G., Linden J., Cronstein B., Pacher P. (2008) Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. , 759–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson L. F., Eltzschig H. K., Ibla J. C., Van De Wiele C. J., Resta R., Morote-Garcia J. C., Colgan S. P. (2004) Crucial role for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. J. Exp. Med. , 1395–1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deaglio S., Dwyer K. M., Gao W., Friedman D., Usheva A., Erat A., Chen J. F., Enjyoji K., Linden J., Oukka M., Kuchroo V. K., Strom T. B., Robson S. C. (2007) Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J. Exp. Med. , 1257–1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaku H., Cheng K. F., Al-Abed Y., Rothstein T. L. (2014) A novel mechanism of B cell–mediated immune suppression through CD73 expression and adenosine production. J. Immunol. , 5904–5913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chunn J. L., Molina J. G., Mi T., Xia Y., Kellems R. E., Blackburn M. R. (2005) Adenosine-dependent pulmonary fibrosis in adenosine deaminase–deficient mice. J. Immunol. , 1937–1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volmer J. B., Thompson L. F., Blackburn M. R. (2006) Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73)-mediated adenosine production is tissue protective in a model of bleomycin-induced lung injury. J. Immunol. , 4449–4458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y., Schneider D. J., Morschl E., Song L., Pedroza M., Karmouty-Quintana H., Le T., Sun C. X., Blackburn M. R. (2011) Distinct roles for the A2B adenosine receptor in acute and chronic stages of bleomycin-induced lung injury. J. Immunol. , 1097–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang-Hoover J., Sutton A., van Rooijen N., Stein-Streilein J. (2000) A critical role for alveolar macrophages in elicitation of pulmonary immune fibrosis. Immunology , 501–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karmouty-Quintana H., Philip K., Acero L. F., Chen N. Y., Weng T., Molina J. G., Luo F., Davies J., Le N. B., Bunge I., Volcik K. A., Le T. T., Johnston R. A., Xia Y., Eltzschig H. K., Blackburn M. R. (2015) Deletion of ADORA2B from myeloid cells dampens lung fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J. , 50–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston C. J., Williams J. P., Elder A., Hernady E., Finkelstein J. N. (2004) Inflammatory cell recruitment following thoracic irradiation. Exp. Lung Res. , 369–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiang C. S., Liu W. C., Jung S. M., Chen F. H., Wu C. R., McBride W. H., Lee C. C., Hong J. H. (2005) Compartmental responses after thoracic irradiation of mice: strain differences. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. , 862–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H., Han G., Liu H., Chen J., Ji X., Zhou F., Zhou Y., Xie C. (2011) The development of classically and alternatively activated macrophages has different effects on the varied stages of radiation-induced pulmonary injury in mice. J. Radiat. Res. (Tokyo) , 717–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groves A. M., Johnston C. J., Misra R. S., Williams J. P., Finkelstein J. N. (2015) Whole-lung irradiation results in pulmonary macrophage alterations that are subpopulation and strain specific. Radiat. Res. , 639–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sica A., Mantovani A. (2012) Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J. Clin. Invest. , 787–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biswas S. K., Mantovani A. (2010) Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat. Immunol. , 889–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon S. (2003) Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. , 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horton J. A., Hudak K. E., Chung E. J., White A. O., Scroggins B. T., Burkeen J. F., Citrin D. E. (2013) Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit cutaneous radiation-induced fibrosis by suppressing chronic inflammation. Stem Cells , 2231–2241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray P. J., Allen J. E., Biswas S. K., Fisher E. A., Gilroy D. W., Goerdt S., Gordon S., Hamilton J. A., Ivashkiv L. B., Lawrence T., Locati M., Mantovani A., Martinez F. O., Mege J. L., Mosser D. M., Natoli G., Saeij J. P., Schultze J. L., Shirey K. A., Sica A., Suttles J., Udalova I., van Ginderachter J. A., Vogel S. N., Wynn T. A. (2014) Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity , 14–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosser D. M., Edwards J. P. (2008) Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. , 958–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein D., Steens J., Wiesemann A., Schulz F., Kaschani F., Röck K., Yamaguchi M., Wirsdörfer F., Kaiser M., Fischer J. W., Stuschke M., Jendrossek V. (2016) Mesenchymal stem cell therapy protects lungs from radiation-induced endothelial cell loss by restoring superoxide dismutase 1 expression. Antioxid. Redox Signal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savani R. C., Hou G., Liu P., Wang C., Simons E., Grimm P. C., Stern R., Greenberg A. H., DeLisser H. M., Khalil N. (2000) A role for hyaluronan in macrophage accumulation and collagen deposition after bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. , 475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karmouty-Quintana H., Weng T., Garcia-Morales L. J., Chen N. Y., Pedroza M., Zhong H., Molina J. G., Bunge R., Bruckner B. A., Xia Y., Johnston R. A., Loebe M., Zeng D., Seethamraju H., Belardinelli L., Blackburn M. R. (2013) Adenosine A2B receptor and hyaluronan modulate pulmonary hypertension associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. , 1038–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKee C. M., Penno M. B., Cowman M., Burdick M. D., Strieter R. M., Bao C., Noble P. W. (1996) Hyaluronan (HA) fragments induce chemokine gene expression in alveolar macrophages. The role of HA size and CD44. J. Clin. Invest. , 2403–2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheibner K. A., Boodoo S., Collins S., Black K. E., Chan-Li Y., Zarek P., Powell J. D., Horton M. R. (2009) The adenosine a2a receptor inhibits matrix-induced inflammation in a novel fashion. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. , 251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vermaelen K., Pauwels R. (2004) Accurate and simple discrimination of mouse pulmonary dendritic cell and macrophage populations by flow cytometry: methodology and new insights. Cytometry A , 170–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.GeurtsvanKessel C. H., Lambrecht B. N. (2008) Division of labor between dendritic cell subsets of the lung. Mucosal Immunol. , 442–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Misharin A. V., Morales-Nebreda L., Mutlu G. M., Budinger G. R., Perlman H. (2013) Flow cytometric analysis of macrophages and dendritic cell subsets in the mouse lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. , 503–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rőszer T. (2015) Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. , 816460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Csóka B., Selmeczy Z., Koscsó B., Németh Z. H., Pacher P., Murray P. J., Kepka-Lenhart D., Morris S. M. Jr., Gause W. C., Leibovich S. J., Haskó G. (2012) Adenosine promotes alternative macrophage activation via A2A and A2B receptors. FASEB J. , 376–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haskó G., Pacher P. (2012) Regulation of macrophage function by adenosine. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. , 865–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chávez-Galán L., Olleros M. L., Vesin D., Garcia I. (2015) Much more than M1 and M2 macrophages, there are also CD169(+) and TCR(+) macrophages. Front. Immunol. , 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Groves A. M., Johnston C. J., Misra R. S., Williams J. P., Finkelstein J. N. (2016) Effects of IL-4 on pulmonary fibrosis and the accumulation and phenotype of macrophage subpopulations following thoracic irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. , 754–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matute-Bello G., Lee J. S., Frevert C. W., Liles W. C., Sutlief S., Ballman K., Wong V., Selk A., Martin T. R. (2004) Optimal timing to repopulation of resident alveolar macrophages with donor cells following total body irradiation and bone marrow transplantation in mice. J. Immunol. Methods , 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Y., Murthy J. N., Zeng D., Belardinelli L., Blackburn M. R. (2010) Alterations in adenosine metabolism and signaling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS One , e9224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gibbons M. A., MacKinnon A. C., Ramachandran P., Dhaliwal K., Duffin R., Phythian-Adams A. T., van Rooijen N., Haslett C., Howie S. E., Simpson A. J., Hirani N., Gauldie J., Iredale J. P., Sethi T., Forbes S. J. (2011) Ly6Chi monocytes direct alternatively activated profibrotic macrophage regulation of lung fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. , 569–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wynn T. A., Vannella K. M. (2016) Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity , 450–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scharpfenecker M., Floot B., Russell N. S., Stewart F. A. (2012) The TGF-beta co-receptor endoglin regulates macrophage infiltration and cytokine production in the irradiated mouse kidney. Radiother. Oncol. 105, 313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perez-Aso M., Mediero A., Low Y. C., Levine J., Cronstein B. N. (2016) Adenosine A2A receptor plays an important role in radiation-induced dermal injury. FASEB J. , 457–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nawroth I., Alsner J., Deleuran B. W., Dagnaes-Hansen F., Yang C., Horsman M. R., Overgaard J., Howard K. A., Kjems J., Gao S. (2013) Peritoneal macrophages mediated delivery of chitosan/siRNA nanoparticle to the lesion site in a murine radiation-induced fibrosis model. Acta Oncol. , 1730–1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khalil N., Bereznay O., Sporn M., Greenberg A. H. (1989) Macrophage production of transforming growth factor beta and fibroblast collagen synthesis in chronic pulmonary inflammation. J. Exp. Med. , 727–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franko A. J., Sharplin J. (1994) Development of fibrosis after lung irradiation in relation to inflammation and lung function in a mouse strain prone to fibrosis. Radiat. Res. , 347–355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osterholzer J. J., Christensen P. J., Lama V., Horowitz J. C., Hattori N., Subbotina N., Cunningham A., Lin Y., Murdock B. J., Morey R. E., Olszewski M. A., Lawrence D. A., Simon R. H., Sisson T. H. (2012) PAI-1 promotes the accumulation of exudate macrophages and worsens pulmonary fibrosis following type II alveolar epithelial cell injury. J. Pathol. , 170–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franko A. J., Sharplin J., Ghahary A., Barcellos-Hoff M. H. (1997) Immunohistochemical localization of transforming growth factor beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha in the lungs of fibrosis-prone and “non-fibrosing” mice during the latent period and early phase after irradiation. Radiat. Res. , 245–256 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leibovich S. J., Chen J. F., Pinhal-Enfield G., Belem P. C., Elson G., Rosania A., Ramanathan M., Montesinos C., Jacobson M., Schwarzschild M. A., Fink J. S., Cronstein B. (2002) Synergistic up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in murine macrophages by adenosine A(2A) receptor agonists and endotoxin. Am. J. Pathol. , 2231–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Macedo L., Pinhal-Enfield G., Alshits V., Elson G., Cronstein B. N., Leibovich S. J. (2007) Wound healing is impaired in MyD88-deficient mice: a role for MyD88 in the regulation of wound healing by adenosine A2A receptors. Am. J. Pathol. , 1774–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ferrante C. J., Pinhal-Enfield G., Elson G., Cronstein B. N., Hasko G., Outram S., Leibovich S. J. (2013) The adenosine-dependent angiogenic switch of macrophages to an M2-like phenotype is independent of interleukin-4 receptor alpha (IL-4Rα) signaling. Inflammation , 921–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koscsó B., Csóka B., Kókai E., Németh Z. H., Pacher P., Virág L., Leibovich S. J., Haskó G. (2013) Adenosine augments IL-10-induced STAT3 signaling in M2c macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. , 1309–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Todd N. W., Luzina I. G., Atamas S. P. (2012) Molecular and cellular mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair , 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paun A., Lemay A. M., Haston C. K. (2010) Gene expression profiling distinguishes radiation-induced fibrosing alveolitis from alveolitis in mice. Radiat. Res. , 512–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalash R., Berhane H., Au J., Rhieu B. H., Epperly M. W., Goff J., Dixon T., Wang H., Zhang X., Franicola D., Shinde A., Greenberger J. S. (2014) Differences in irradiated lung gene transcription between fibrosis-prone C57BL/6NHsd and fibrosis-resistant C3H/HeNHsd mice. In Vivo , 147–171 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang F., Wang H., Wang X., Jiang G., Liu H., Zhang G., Fang R., Bu X., Cai S., Du J. (2016) TGF-beta induces M2-like macrophage polarization via SNAIL-mediated suppression of a pro-inflammatory phenotype. Oncotarget , 52294–52306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mantovani A., Biswas S. K., Galdiero M. R., Sica A., Locati M. (2013) Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J. Pathol. , 176–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schneider D. J., Lindsay J. C., Zhou Y., Molina J. G., Blackburn M. R. (2010) Adenosine and osteopontin contribute to the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. FASEB J. , 70–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cronstein B. N. (2011) Adenosine receptors and fibrosis: a translational review. F1000 Biol. Rep. , 21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shaikh G., Cronstein B. (2016) Signaling pathways involving adenosine A2A and A2B receptors in wound healing and fibrosis. Purinergic Signal. , 191–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Itano N., Sawai T., Yoshida M., Lenas P., Yamada Y., Imagawa M., Shinomura T., Hamaguchi M., Yoshida Y., Ohnuki Y., Miyauchi S., Spicer A. P., McDonald J. A., Kimata K. (1999) Three isoforms of mammalian hyaluronan synthases have distinct enzymatic properties. J. Biol. Chem. , 25085–25092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weigel P. H., Hascall V. C., Tammi M. (1997) Hyaluronan synthases. J. Biol. Chem. , 13997–14000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]