Key Points

Question

Does a higher dose (1200 IU) of supplemental vitamin D3 administered to healthy infants increase bone strength or decrease incidence of infections compared with the standard dose (400 IU)?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial of 975 infants found no difference in bone strength or incidence of infections between intervention groups at 24 months of age.

Meaning

In healthy infants, daily supplementation with 1200 IU of vitamin D3 provides no additional benefits compared with supplementation with 400 IU for bone strength or incidence of infections in early childhood.

Abstract

Importance

Although guidelines for vitamin D supplementation in infants have been widely implemented, they are mostly based on studies focusing on prevention of rickets. The optimal dose for bone strength and infection prevention in healthy infants remains unclear.

Objective

To determine whether daily supplementation with 1200 IU of vitamin D3 increases bone strength or decreases incidence of infections in the first 2 years of life compared with a dosage of 400 IU/d.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized clinical trial involving a random sample of 975 healthy term infants at a maternity hospital in Helsinki, Finland. Study recruitment occurred between January 14, 2013, and June 9, 2014, and the last follow-up was May 30, 2016. Data analysis was by the intention-to-treat principle.

Interventions

Randomization of 489 infants to daily oral vitamin D3 supplementation of 400 IU and 486 infants to 1200 IU from age 2 weeks to 24 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes were bone strength and incidence of parent-reported infections at 24 months.

Results

Of the 975 infants who were randomized, 485 (49.7%) were girls and all were of Northern European ethnicity. Eight hundred twenty-three (84.4%) completed the 24-month follow-up. We found no differences between groups in bone strength measures, including bone mineral content (mean difference, 0.4 mg/mm; 95% CI, −0.8 to 1.6), mineral density (mean difference, 2.9 mg/cm3; 95% CI, −8.3 to 14.2), cross-sectional area (mean difference, –0.9 mm2; 95% CI, −5.0 to 3.2), or polar moment of inertia (mean difference, –66.0 mm4, 95% CI, −274.3 to 142.3). Incidence rates of parent-reported infections did not differ between groups (incidence rate ratio, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.93-1.06). At birth, 914 of 955 infants (95.7%) were vitamin D sufficient (ie, 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentration ≥20.03 ng/mL). At 24 months, mean 25(OH)D concentration was higher in the 1200-IU group than in the 400-IU group (mean difference, 12.50 ng/mL; 95% CI, 11.22-13.78).

Conclusions and Relevance

A vitamin D3 supplemental dose of up to 1200 IU in infants did not lead to increased bone strength or to decreased infection incidence. Daily supplementation with 400 IU vitamin D3 seems adequate in maintaining vitamin D sufficiency in children younger than 2 years.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01723852

This randomized clinical trial compares the effect of 1200-IU vs 400-IU doses of vitamin D3 on bone strength and infection in Finnish healthy term infants.

Introduction

For decades, vitamin D deficiency has been a worldwide health concern.1 Many countries have implemented guidelines for vitamin D supplementation and food fortification, but preventive measures have not been adequate.2 In the United States, vitamin D deficiency, defined as serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) concentration less than 20.03 ng/mL (to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496), was reported in 1988 to 2010 in 26% to 32% of the population.3 Likewise, a 2016 study involving more than 50 000 European adults and children estimated 40% to be vitamin D deficient.4

Vitamin D deficiency in infants can lead to impaired bone mineralization and rickets.5 Since the 1920s, vitamin D has been recognized as effective in preventing and treating rickets, but optimal supplementation for bone health is still unclear, with data on the skeletal effects of vitamin D in infants being scarce.6,7,8

Vitamin D is a potent modulator of both innate and adaptive immunity.9 Some observational studies report an association between vitamin D deficiency and increased infectious diseases.10,11,12 Randomized trials, however, show conflicting results and few involve infants.13,14,15 Because infections are a major cause of early childhood morbidity, the effect of vitamin D supplementation is of great interest.

We conducted a randomized clinical trial comparing daily vitamin D3 supplementation of 400 IU and 1200 IU in healthy infants aged 2 weeks to 24 months. Our aim was to evaluate effects of vitamin D supplementation on bone strength and incidence of infections. We hypothesized that higher dosages of vitamin D supplementation would lead to increased bone strength and to decreased frequency of infections in early childhood.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The Vitamin D Intervention in Infants (VIDI) study was a randomized, double-blind, 24-month clinical trial of daily vitamin D3 supplementation of 400 IU or 1200 IU administered to infants. Between January 14, 2013, and June 9, 2014, families were recruited at Kätilöopisto Helsinki Maternity Hospital, Helsinki, Finland, 1 to 2 days after delivery. All follow-up was completed on May 30, 2016. Mothers took no regular medication and had a singleton pregnancy. Ethnicity was restricted to Northern European to exclude the effect of skin pigmentation on vitamin D status.16 Eligible infants were born at term (37 weeks and 0 days’ to 42 weeks and 0 days’ gestation), with a birth weight within 2 SDs of the mean for gestational age.17

Infants excluded were those requiring intravenous glucose, antibiotics, nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment for more than 1 day, phototherapy for more than 3 days, or nasogastric tube feeding for more than 1 day and infants with seizures.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa approved the study. The project protocol is provided in Supplement 1 and has been described in a previously published article.18 Parents gave written informed consent at recruitment.

Randomization and Blinding

Infants were randomized (1:1) to receive 400 IU or 1200 IU of vitamin D3 daily from age 2 weeks to 24 months. To ensure fair distribution across the year, a pharmacist at Helsinki University Hospital with no relation to the study performed randomization in blocks of 50. Both study preparations, manufactured by Orion Pharmaceuticals, contained vitamin D3 dissolved in medium-chain triglyceride oil and were identical in appearance. Participants and investigators were masked to group assignment, and no changes to the methods were made after trial commencement. An external steering group monitored the study.

Procedures

Vitamin D supplements were administered orally once daily in a volume of 5 drops for both concentrations. No other vitamin D supplements were allowed concurrently. The families recorded daily vitamin D supplementation and all their child’s infections in study diaries. Completed diaries were collected and reviewed at follow-up visits arranged at ages 6, 12, and 24 months. Adherence to treatment was calculated from the diaries as the percentage of days of supplement administration compared with the total number of days of follow-up.

We analyzed 25(OH)D concentration (in nanograms per milliliter; to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496) at birth (cord blood) and at ages 12 and 24 months and intact parathyroid hormone concentration at ages 12 and 24 months with a fully automated immunoassay (IDS-iSYS; Immunodiagnostic System Ltd). Details on data collection and laboratory analyses are provided in eAppendix 1 and eAppendix 2 in Supplement 2.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes were bone strength and incidence of parent-reported infections at 24 months. We used 4 different bone measurements for total and cortical bone to assess bone strength because none of these alone determines fracture resistance.19 Bone mineral content reflects bone mineral quantity (in milligrams) per millimeter, bone mineral density reflects bone mineral quantity (in milligrams) per cubic centimeter, cross-sectional area of the bone reflects bone area in square millimeters, and polar moment of inertia reflects bone resistance to torsion (measured in quartic millimeters). These bone strength measurements were assessed at age 24 months with peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) (Stratec XCT 2000 L Research+; Stratec Medizintechnik GmbH) of the left tibia. The length of the tibia was measured from the medial malleolus to the medial condyle, and bone strength was measured at 20% distal proximal length. We graded each pQCT scan quality according to movement artifacts from 1 to 5 and further as good (grades 1-2), moderate (grades 3-4), or poor (grade 5).20 If major movement artifacts or incorrect leg positioning occurred, the scan was excluded.

Infections were assessed from study diaries in which parents prospectively recorded all their child’s infections. Parents reported the date of the infection (month/year), infection type, symptoms or specific diagnosis, duration, medication, physician visit, or hospitalization. The cumulative number of infection episodes was calculated for the 24-month study. If several symptoms or diagnosed infections were reported for the same period, these were considered as belonging to the same episode.

For characterization, the parent-reported infections were divided post hoc into 7 subtypes: (1) upper respiratory tract infection, defined as presence of rhinitis, cough, sore throat, nasal congestion, or sneezing, with or without fever (temperature, >38.0°C); (2) acute otitis media diagnosed by a physician; (3) pneumonia diagnosed by a physician; (4) conjunctivitis, defined as reddish eye, discharge from the eye, or both; (5) gastroenteritis, defined as vomiting and/or diarrhea; (6) nonspecified viral infection, defined as fever (temperature, >38.0°C) with or without skin manifestations; and (7) other bacterial infection including miscellaneous bacterial infections, such as of the urinary tract or skin. For outcome analyses, the infections were further grouped into 3 main types: (1) respiratory infections, including upper respiratory tract infections, acute otitis media, and pneumonia; (2) gastroenteritis; and (3) other bacterial and viral infections, including conjunctivitis.

Safety Monitoring

Trial safety was ensured by measurement of the ionized calcium concentration at follow-up visits. In case of severe hypercalcemia, defined as an ionized calcium concentration exceeding the upper age-specific reference limit by 10% or more (ie, 6.12 mg/dL at ages 6 and 12 months and 5.92 mg/dL at age 24 months; to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.25), calcium and 25(OH)D concentrations were to be remeasured, symptoms indicative of hypercalcemia investigated, and continuation of vitamin D supplementation reevaluated. In case of any adverse effects or severe hypercalcemia, an external monitor was to be informed.

Statistical Analysis

The trial was designed with a planned sample of 1000 study participants. This total allowed an estimated 20% dropout rate, leaving 800 participants. To reach the statistical power to detect a 0.2-SD difference in bone mineral content or bone cross-sectional area, the estimate was 210 and 297 pQCT scans, respectively, in each group.21 For infections, assuming an average annual infection rate of 6 for a child younger than 2 years, we estimated that detection of a decrease from 12 to 9 infections during the 24-month study period required a sample size of 220 per group to achieve a statistical power of 90%.22,23

Comparisons of baseline and follow-up characteristics and of biochemical measures were analyzed with the 2-tailed independent sample unpaired t test, Mann-Whitney test, or Pearson χ2 as applicable. Logarithmic transformation was used for variables with nonnormal distribution.

We assessed differences in bone strength between groups with a multivariate analysis of covariance. We used a crude model and an adjusted model, the latter using as covariates sex, age, weight, and quality of scans. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS, version 22 (IBM).

To evaluate the effect of group on infection outcome measures, we applied a negative binomial model. Incidence was estimated as the proportion of follow-up time in person-months, which allowed use of all available infection data, including data from incomplete study diaries. A complementary log-logistic model served to model the probability of at least 1 infection episode.

For group-season interaction analyses of infections, data were split into 1-month intervals. Random-effects models served for estimation to account for dependence of individual data on separate intervals (range, 3-25 months per participant). Analyses were performed with Stata statistical software, version 14 (StataCorp).

In the analyses, we applied the intention-to-treat principle. Per-protocol analyses included participants with treatment adherence of at least 80%. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

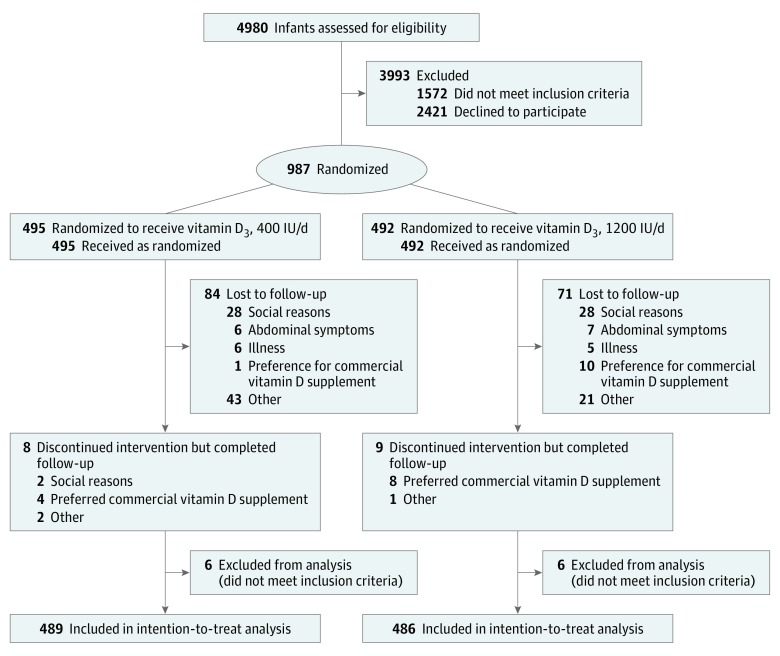

Of the 4980 participants screened, 987 were found eligible and consented to participate. Twelve infants were excluded after randomization for not meeting eligibility criteria, leaving 975 infants, of whom 489 were randomly assigned to the 400-IU group and 486 to the 1200-IU group (Figure 1). Of the 975 infants who were randomized, 485 (49.7%) were girls and all were of Northern European ethnicity. Baseline characteristics between groups did not differ (Table 1).

Figure 1. Participant Flow of the Vitamin D Intervention in Infants Study.

Table 1. Characteristics of 975 Participants in the Vitamin D Intervention in Infants Studya.

| Characteristic | All (N = 975) | 400-IU Group (n = 489) | 1200-IU Group (n = 486) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| Sex, female, No. (%) | 485 (49.7) | 242 (49.5) | 243 (50.0) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 3539 (395) | 3514 (379) | 3565 (410) |

| Birth length, mean (SD), cm | 50.3 (1.7) | 50.3 (1.7) | 50.4 (1.8) |

| Apgar score at 1 min, mean (SD) | 9 (1) | 9 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Gestational age, mean (SD), wk | 40.2 (1.1) | 40.1 (1.1) | 40.2 (1.1) |

| Mode of birth, vaginal, No. (%) | 911 (93.4) | 456 (93.3) | 455 (93.6) |

| Season of birth, No. (%) | |||

| Winter | 189 (19.4) | 100 (20.4) | 89 (18.3) |

| Spring | 400 (41.0) | 197 (40.3) | 203 (41.8) |

| Summer | 217 (22.3) | 108 (22.1) | 109 (22.4) |

| Autumn | 169 (17.3) | 84 (17.2) | 85 (17.5) |

| Older siblings (n = 892), No. (%) | 331 (37.1) | 153 (34.5) | 178 (39.7) |

| Breastfeeding (n = 854), No. (%) | |||

| 0-3 mo | 72 (8.4) | 39 (9.1) | 33 (7.7) |

| 3.1-6 mo | 108 (12.6) | 59 (13.8) | 49 (11.5) |

| >6 mo | 674 (78.9) | 330 (77.1) | 344 (80.8) |

| Daily dietary intake of vitamin D at age 12 mo (n = 730), mean (SD), IU | 248 (148) | 252 (144) | 240 (148) |

| Daily dietary intake of calcium at age 12 mo (n = 730), mean (SD), mg | 613 (308) | 627 (310) | 599 (307) |

| Day care attendance, No. (%) | |||

| At age 12 mo (n = 866) | 38 (4.4) | 15 (3.4) | 23 (5.3) |

| At age 24 mo (n = 796) | 491 (61.7) | 243 (61.4) | 248 (62.0) |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD), mo | 16.3 (3.4) | 16.3 (3.5) | 16.3 (3.3) |

| Influenza vaccination (n = 889), No. (%) | 353 (39.7) | 190 (42.7) | 163 (36.7) |

| Mother | |||

| Age at delivery, mean (SD), y | 31.5 (4) | 31.2 (4) | 31.8 (5) |

| BMI before pregnancy (n = 891), mean (SD) | 23.2 (3.7) | 23.1 (3.7) | 23.3 (3.7) |

| Use of vitamin D supplements during pregnancy (n = 863), No. (%) | 813 (94.2) | 407 (94.7) | 406 (93.7) |

| Daily vitamin D supplemental dose during pregnancy (n = 863), IU, mean (SD) | 620 (640) | 660 (760) | 580 (520) |

| Socioeconomic | |||

| Maternal educational level (n = 883), No. (%)b | |||

| Low | 226 (25.6) | 119 (27.2) | 107 (24.0) |

| High | 657 (74.4) | 318 (72.8) | 657 (76.0) |

| Paternal educational level (n = 870), No. (%)b | |||

| Low | 328 (37.7) | 164 (37.8) | 164 (37.6) |

| High | 542 (62.3) | 270 (62.2) | 272 (62.4) |

| Household annual income (n = 750), No. (%)c | |||

| Low | 135 (18.0) | 64 (16.8) | 71 (19.2) |

| Medium | 544 (72.5) | 281 (73.9) | 263 (71.1) |

| High | 71 (9.7) | 35 (9.2) | 36 (9.7) |

| Maternal smoking before pregnancy (n = 878), No. (%) | 130 (14.8) | 64 (14.8) | 66 (14.8) |

| Maternal smoking after delivery (n = 869), No. (%) | 32 (3.7) | 17 (4.0) | 15 (3.4) |

| Mother or father smoking after delivery (n = 837), No. (%) | 137 (16.4) | 65 (15.7) | 72 (17.0) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Infants were randomized to receive vitamin D3, 400 IU/d or 1200 IU/d.

For educational level, low indicates less than a bachelor’s degree; high, at least a bachelor’s degree.

For annual income, low indicates less than €40 000 (<$48 316); medium, €40 000 to €109 999 ($48 316-$132 868); and high, €110 000 ($132 869) or more.

Adherence to Treatment

A total of 823 children (84.4%) completed the 24-month study; 865 (88.7%) attended the 12-month and 892 (91.5%) the 6-month follow-up (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The cumulative number of participants lost to follow-up was 83 at 6 months, 110 at 12 months, and 152 at 24 months and did not differ between groups. The mean adherence to vitamin D supplementation during 24 months was 88% and was similar in both groups (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). At age 24 months, the proportion of children with at least 80% adherence was 83.5% (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

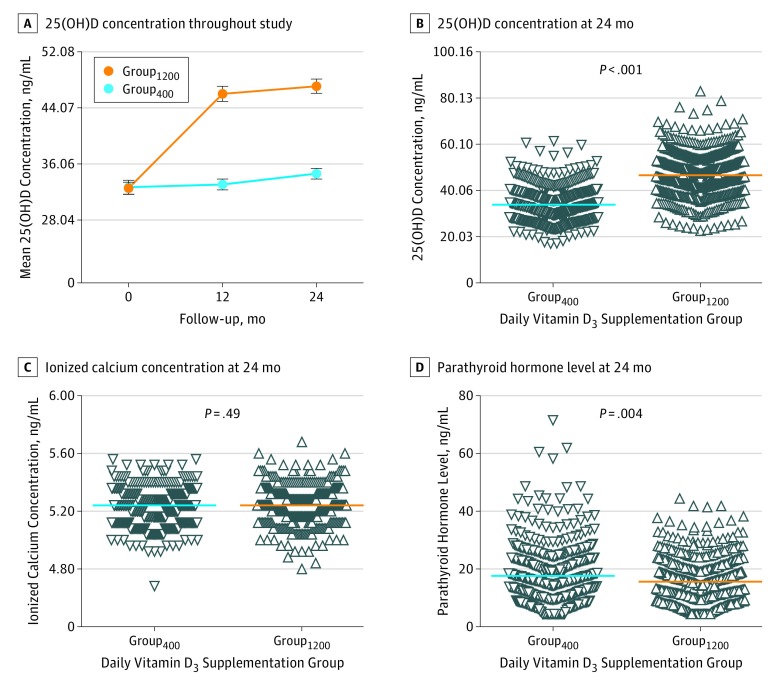

Biochemical Effects

Mean (SD) 25(OH)D concentration at birth was 32.73 (11.14) ng/mL in the 400-IU group and 32.57 (9.62) ng/mL in the 1200-IU group; at 12 months, mean concentration was 33.13 (7.93) ng/mL in the 400-IU group and 46.07 (11.10) ng/mL in the 1200-IU group; and at 24 months, 34.70 (7.85) ng/mL in the 400-IU group and 47.16 (10.46) ng/mL in the 1200-IU group (mean difference, 12.50 ng/mL; 95% CI, 11.22-13.78) (Figure 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 2). At birth, 914 of 955 infants (95.7%) were vitamin D sufficient (25[OH]D concentration ≥20.03 ng/mL), with no difference between groups (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). At age 24 months, the 25(OH)D concentration in the 404 children evaluated in the 400-IU group was 30.05 ng/mL or greater in 285 children (70.5%) and 50.08 ng/mL or greater in 13 (3.2%). Among the 410 children in the 1200-IU group, 391 (95.4%) had a 25(OH)D concentration of 30.05 ng/mL or greater, and 159 (38.8%) had a concentration of 50.08 ng/mL or greater. None of the infants had a 25(OH)D concentration greater than 100.16 ng/mL (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, Ionized Calcium, and Intact Parathyroid Hormone Concentrations During the Vitamin D Intervention in Infants Study.

A, Mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) concentrations with 95% CIs at baseline (cord blood), age 12 months, and age 24 months in infants randomized to vitamin D, 400 IU/d and 1200 IU/d. B through D, Crude values at 24-month follow-up by intervention group. Horizontal lines in panels B, C, and D represent median values. P values refer to differences between intervention groups as tested by the 2-tailed, unpaired, independent-samples t test. To convert serum 25(OH)D to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496; ionized calcium to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.25; and parathyroid hormone to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1.0.

Mean ionized calcium concentrations did not differ between groups (Figure 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 2). At age 12 months, the ionized calcium concentrations were within age-specific reference limits in 838 (98.1%) of the 854 children evaluated, and at age 24 months concentrations were within age-specific limits in 667 (91.9%) of the 726 children evaluated (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). No participants developed severe hypercalcemia. At ages 12 and 24 months, the serum parathyroid hormone level was lower in the 1200-IU group than in the 400-IU group (Figure 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 2). A per-protocol analysis was applied to all biochemical effects with consistent results.

Primary Outcomes

We performed pQCT bone scans of the left tibia in 783 of the 823 children (95.1%) attending the age 24-month follow-up. Owing to motion artifacts, 79 (10.1%) of the scans failed and were excluded. A total of 704 scans (89.9%) were included in the analyses. Of these, scan quality was assessed as good in 165 (48.1%) of the 400-IU group and 193 (53.5%) of the 1200-IU group participants, moderate in 124 (36.2%) of the 400-IU group and 133 (36.8%) of the 1200-IU group, and poor in 54 (15.7%) of the 400-IU group and 35 (9.7%) of the 1200-IU group. Bone strength measurements for total bone and cortical bone did not differ between groups (Table 2). The findings remained unaltered in per-protocol analysis and after adjustment for sex, age, weight, and quality of scans.

Table 2. Total and Cortical Bone Measurements Assessed by pQCT of the Left Distal Tibia at Age 24 Months by Intervention Groupa.

| Bone Measurement | 400-IU Group | 1200-IU Group | Mean Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total bone | |||

| Scans, No. (%) | 343 (48.7) | 361 (51.3) | NA |

| BMC, mean (95% CI), mg/mm | 54.2 (53.4 to 55.1) | 54.7 (53.8 to 55.5) | 0.4 (−0.8 to 1.6) |

| BMD, mean (95% CI), mg/cm3 | 375.8 (367.7 to 383.8) | 378.7 (370.9 to 386.5) | 2.9 (−8.3 to 14.2) |

| CSA, mean (95% CI), mm2 | 148.6 (145.7 to 151.5) | 147.7 (144.9 to 150.6) | −0.9 (−5.0 to 3.2) |

| Polar moment of inertia, mean (95% CI), mm4 | 3759 (3610 to 3908) | 3693 (3548 to 3838) | −66.0 (−274.3 to 142.3) |

| Cortical bone | |||

| Scans, No. (%) | 343 (48.7) | 361 (51.3) | NA |

| BMC, mean (95% CI), mg/mm | 42.6 (41.6 to 43.6) | 43.6 (42.7 to 44.6) | 1.0 (−0.4 to 2.4) |

| BMD, mean (95% CI), mg/cm3 | 723.8 (717.2 to 730.3) | 729.7 (723.3 to 736.1) | 6.0 (−3.2 to 15.2) |

| CSA, mean (95% CI), mm2 | 58.4 (57.4 to 59.4) | 59.4 (58.4 to 60.4) | 1.0 (−0.4 to 2.4) |

| Polar moment of inertia, mean (95% CI), mm4 | 2055 (1999 to 2112) | 2065 (2010 to 2120) | 9.9 (−69.1 to 88.9) |

Abbreviations: BMC, bone mineral content; BMD, bone mineral density; CSA, cross-sectional area; NA, not applicable; pQCT, peripheral quantitative computed tomography.

Infants were randomized to receive vitamin D3, 400 IU/d or 1200 IU/d. Values represent means and mean differences with 95% CIs from multivariate analysis of covariance.

Infection data from study diaries were obtained from 449 participants in the 400-IU group and 448 in the 1200-IU group; for 78 participants, data were completely missing. At the trial’s end, 8458 parent-reported infection episodes had occurred, amounting to a mean 9.18 (95% CI, 8.73-9.63) in the 400-IU group and 9.14 (95% CI, 8.68-9.60) in the 1200-IU group, with no differences in incidence rates of infection between groups (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.00; 95% CI, 0.93-1.06); (Table 3 and eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Infection characteristics were similar; the majority were respiratory infections (eTable 7 in Supplement 2). The only difference between groups was a higher incidence rate of antibiotic treatment in the 1200-IU group (IRR 1.17; 95% CI, 1.00-1.36). Results did not change in per-protocol analysis or after adjustment for potential confounding factors (ie, parental educational level, existence of older siblings, parental smoking, day care attendance, season of birth, or duration of breastfeeding).

Table 3. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Infection Outcome Measures During the 24-Month Vitamin D Intervention in Infants Studya.

| Outcome Measure | 400-IU Group | 1200-IU Group | IRR (95% CI)d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, No. | Events, No. | Incidence Rateb | Participants, No. | Events, No. | Incidence Ratec | ||

| Infection episodes | 449 | 4244 | 0.41 | 448 | 4214 | 0.41 | 1.00 (0.93-1.06) |

| Respiratory infections | 449 | 3321 | 0.32 | 448 | 3303 | 0.32 | 1.00 (0.93-1.07) |

| Gastroenteritis | 449 | 379 | 0.04 | 448 | 349 | 0.03 | 0.92 (0.79-1.08) |

| Other infections | 449 | 544 | 0.05 | 448 | 562 | 0.06 | 1.04 (0.91-1.19) |

| Antibiotic treatments | 441 | 795 | 0.08 | 435 | 922 | 0.09 | 1.17 (1.00-1.36) |

| Physician visits | 443 | 1421 | 0.14 | 435 | 1502 | 0.15 | 1.07 (0.94-1.21) |

| Hospitalizations | 443 | 33 | 0.00 | 435 | 38 | 0.00 | 1.16 (0.71-1.89) |

| Days infected, No.e | 437 | 26 314 | 0.08 | 430 | 25 541 | 0.08 | 0.97 (0.88-1.07) |

| Duration per infection episode, df | 437 | 3272 | 0.01 | 430 | 3100 | 0.01 | 0.95 (0.89-1.01) |

Abbreviation: IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Infants were randomized to receive vitamin D3, 400 IU/d or 1200 IU/d.

Incidence rate was calculated from the total number of events divided by the number of person-months (10 237) except for duration per infection episode and number of days infected, which were divided by the number of person-days (309 657).

Incidence rate was calculated from the total number of events divided by the number of person-months (10 204) except for duration per infection episode and number of days infected, which were divided by the number of person-days (308 675).

Calculated using negative binomial regression.

Total number of days of illness during the 24-month follow-up.

Duration of illness in days per infection episode.

In interaction analyses, the only differences were for infection duration, indicating that, in winter and spring, duration was shorter in the 1200-IU group (test for 2 interactions: P = .01; winter: IRR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81-0.97; spring: IRR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81-0.99), and the likelihood of contracting gastroenteritis in winter was also lower in the 1200-IU group (test for interaction: P = .04; IRR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.60-0.97).

Discussion

This study involving 975 healthy children is, to our knowledge, the first large randomized clinical trial evaluating vitamin D supplementation from infancy to early childhood. We observed no differences in bone strength measurements or in incidence of parent-reported infections between the 400-IU and 1200-IU intervention groups. Our study had adequate power to detect or exclude any but small differences between groups.

At birth, 914 of 955 (95.7%) of the infants were vitamin D sufficient (had a 25[OH]D concentration ≥20.03 ng/mL), reflecting adequate maternal vitamin D intake.24 At age 24 months, 809 of 814 (99.4%) of the study participants were vitamin D sufficient. None had a 25(OH)D concentration greater than 100.16 ng/mL or severe hypercalcemia, which are indicators of vitamin D toxicity.5 These findings imply that a daily dose of 1200 IU of vitamin D3 in this age group is safe, but even 400 IU will maintain vitamin D sufficiency in most children.

We found no significant differences between the groups in any of the bone strength measurements, in line with randomized trials involving older vitamin D–sufficient children (aged 8-17 years) in which vitamin D dosages ranging from 132 IU/d to 14 000 IU/wk did not improve bone strength as measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry or pQCT.25 However, in an earlier study in 3-month-old infants, those with higher-dose vitamin D supplementation (1600 IU vs 400 IU) had larger tibial bone area compared with those receiving the lower dose.26 The divergent results in the present study may result from this study’s longer duration and larger cohort. In vitamin D–sufficient children, factors other than 25(OH)D concentration, such as motor competence, lean mass, or calcium intake, may have a greater influence on bone strength.21,27,28

We observed no differences in the incidence of parent-reported infections between the groups, with identical results in the per-protocol analyses. One recent large meta-analysis13 concluded that vitamin D supplementation is effective in preventing acute respiratory tract infections, but it comprised heterogeneous studies including children older than 2 years and adults with varying baseline 25(OH)D concentrations; in subgroup analysis, the protective effect of supplementation was stronger in those with a baseline 25(OH)D concentration less than 10.02 ng/mL. Because our study participants were mostly ([914 of 955] [95.7%]) vitamin D sufficient, our results support the findings that, in vitamin D–sufficient children, additional vitamin D supplementation provides no further benefit in resisting infections.29

In interaction analyses, however, we did observe the duration of infections in winter and spring in the 1200-IU group to be shorter than in the 400-IU group. This finding suggests that higher dosages of vitamin D may shorten the duration of illness during winter months, when infections are more frequent and when cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D is limited. However, this difference was marginal, was based on a post hoc analysis, and demands confirmation in future studies.

We hypothesized that higher dosages of vitamin D supplementation improve bone strength and reduce infections in early childhood in a northern European population with limited sunlight exposure. We expected a greater proportion of children to be vitamin D deficient at birth because studies conducted in 2007 and 2010 showed that approximately half the healthy newborns studied were vitamin D deficient.26,30 However, since 2010, Finnish public health authorities have improved vitamin D intake at the population level by food fortification and promotion of vitamin D supplementation. Currently, liquid milk products are fortified with 40 IU of vitamin D3 per 100 mL and fat spreads with 800 IU per 100 g. Guidelines for vitamin D supplementation recommend 400 IU daily for pregnant and breastfeeding women and for children younger than 2 years and 300 IU daily for persons aged 2 to 17 years.31 These public health actions have recently improved vitamin D status in Finland.31,32 The absence of vitamin D–deficient infants may explain the lack of any effect of higher vitamin D supplementation on our primary outcomes. Moreover, the higher dose of 1200 IU is unlikely to have been too small because, for 676 of the 814 (83.0%) participants at study end, 25(OH)D concentrations exceeded 30.05 ng/mL.

Limitations

The quality of bone scans varied, and movement artifacts were common owing to technical challenges in pQCT measurement in young children. However, 615 of the 704 scans (87.4%) were of good or moderate quality, with no differences between groups. We adjusted the statistical model by scan quality, with consistent results. On the other hand, pQCT gives more detailed information about bone characteristics, and we regard its use, instead of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, as a significant strength of our study. Assessment of infections was based on parents’ report without clinical evaluation or laboratory confirmation, which may have led to underestimation or overestimation of infection prevalence. Definitions of infection may also vary. However, because the study was double-blinded and controlled, any recall and observation bias is likely to be equally distributed between groups, although such bias could increase random error and thus reduce the likelihood of detecting differences. That the frequency and seasonal distribution of infections in our cohort corresponds to earlier findings in a similar age group further supports the validity of our data.33,34

Conclusions

In vitamin D–sufficient healthy infants, daily supplementation with 1200 IU vitamin D3 compared with 400 IU provides no additional benefits for bone strength or for parent-reported incidence of infections during the first 2 years of life. In a country where sunlight exposure is limited but food fortification with vitamin D is common, supplementation with 400 IU of vitamin D3 daily seems adequate to ensure vitamin D sufficiency in children younger than 2 years.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix 1. Supplementary Methods

eAppendix 2. The Report from Immunodiagnostic Systems Containing the Linear Regression Equation for Correction of Cord Blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration

eTable 1. Child Anthropometric Characteristics at Follow-up Visits

eTable 2. Compliance With Vitamin D Supplementation During the 24-Month Study

eTable 3. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, Plasma Ionized Calcium, and Serum Intact Parathyroid Hormone Concentrations During Follow-up by Intervention Group

eTable 4. Vitamin D Status During Follow-up by Intervention Group

eTable 5. Calcium Status During Follow-up by Intervention Group

eTable 6. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Incidence of Infections at 24 Months, With Infections in Seven Subtypes According to Parentally Reported Symptoms or Diagnosis

eTable 7. Characteristics of Parent-Reported Infections per Child During 24-Month Follow-up

References

- 1.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiro A, Buttriss JL. Vitamin D: an overview of vitamin D status and intake in Europe. Nutr Bull. 2014;39(4):322-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schleicher RL, Sternberg MR, Lacher DA, et al. The vitamin D status of the US population from 1988 to 2010 using standardized serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D shows recent modest increases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(2):454-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cashman KD, Dowling KG, Škrabáková Z, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in Europe: pandemic? Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(4):1033-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munns CF, Shaw N, Kiely M, et al. Global consensus recommendations on prevention and management of nutritional rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):394-415. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holick MF. Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2062-2072. doi: 10.1172/JCI29449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sayers A, Fraser WD, Lawlor DA, Tobias JH. 25-Hydroxyvitamin-D3 levels are positively related to subsequent cortical bone development in childhood: findings from a large prospective cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(8):2117-2128. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1813-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viljakainen HT, Korhonen T, Hytinantti T, et al. Maternal vitamin D status affects bone growth in early childhood—a prospective cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(3):883-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewison M. An update on vitamin D and human immunity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;76(3):315-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Science M, Maguire JL, Russell ML, Smieja M, Walter SD, Loeb M. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and risk of upper respiratory tract infection in children and adolescents. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(3):392-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JW, Hogan PG, Hunstad DA, Fritz SA. Vitamin D sufficiency and Staphylococcus aureus infection in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(5):544-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ginde AA, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA Jr. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and upper respiratory tract infection in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(4):384-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Hooper RL, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao L, Xing C, Yang Z, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of childhood acute respiratory infections: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(7):1026-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vuichard Gysin D, Dao D, Gysin CM, Lytvyn L, Loeb M. Effect of vitamin D3 supplementation on respiratory tract infections in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clemens TL, Adams JS, Henderson SL, Holick MF. Increased skin pigment reduces the capacity of skin to synthesise vitamin D3. Lancet. 1982;1(8263):74-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saari A, Sankilampi U, Hannila ML, Kiviniemi V, Kesseli K, Dunkel L. New Finnish growth references for children and adolescents aged 0 to 20 years: length/height-for-age, weight-for-length/height, and body mass index-for-age. Ann Med. 2011;43(3):235-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helve O, Viljakainen H, Holmlund-Suila E, et al. Towards evidence-based vitamin D supplementation in infants: vitamin D intervention in infants (VIDI)—study design and methods of a randomised controlled double-blinded intervention study. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0845-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ammann P, Rizzoli R. Bone strength and its determinants. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(suppl 3):S13-S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blew RM, Lee VR, Farr JN, Schiferl DJ, Going SB. Standardizing evaluation of pQCT image quality in the presence of subject movement: qualitative versus quantitative assessment. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;94(2):202-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ireland A, Rittweger J, Schönau E, Lamberg-Allardt C, Viljakainen H. Time since onset of walking predicts tibial bone strength in early childhood. Bone. 2014;68:76-84. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wald ER, Guerra N, Byers C. Frequency and severity of infections in day care: three-year follow-up. J Pediatr. 1991;118(4, pt 1):509-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denny FW, Collier AM, Henderson FW. Acute respiratory infections in day care. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8(4):527-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hauta-Alus HH, Holmlund-Suila EM, Rita HJ, et al. Season, dietary factors, and physical activity modify 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration during pregnancy [published online March 2, 2017]. Eur J Nutr. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1417-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winzenberg T, Powell S, Shaw KA, Jones G. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on bone density in healthy children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmlund-Suila E, Viljakainen H, Hytinantti T, Lamberg-Allardt C, Andersson S, Mäkitie O. High-dose vitamin D intervention in infants—effects on vitamin D status, calcium homeostasis, and bone strength. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(11):4139-4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeddi M, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Ranjbar Omrani G, Ayatollahi SM, Bagheri Z, Bakhshayeshkaram M. Relative importance of lean and fat mass on bone mineral density in Iranian children and adolescents. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;13(3):e25542. doi: 10.5812/ijem.25542v2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umaretiya PJ, Thacher TD, Fischer PR, Cha SS, Pettifor JM. Bone mineral density in Nigerian children after discontinuation of calcium supplementation. Bone. 2013;55(1):64-68. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aglipay M, Birken CS, Parkin PC, et al. ; TARGet Kids! Collaboration . Effect of high-dose vs standard-dose wintertime vitamin D supplementation on viral upper respiratory tract infections in young healthy children. JAMA. 2017;318(3):245-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viljakainen HT, Saarnio E, Hytinantti T, et al. Maternal vitamin D status determines bone variables in the newborn. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(4):1749-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raulio S, Erlund I, Männistö S, et al. Successful nutrition policy: improvement of vitamin D intake and status in Finnish adults over the last decade. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(2):268-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jääskeläinen T, Itkonen ST, Lundqvist A, et al. The positive impact of general vitamin D food fortification policy on vitamin D status in a representative adult Finnish population: evidence from an 11-y follow-up based on standardized 25-hydroxyvitamin D data. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1512-1520. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.151415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toivonen L, Schuez-Havupalo L, Karppinen S, et al. Rhinovirus infections in the first 2 years of life. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161309. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taipale TJ, Pienihäkkinen K, Isolauri E, Jokela JT, Söderling EM. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12 in reducing the risk of infections in early childhood. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(1-1):65-69. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix 1. Supplementary Methods

eAppendix 2. The Report from Immunodiagnostic Systems Containing the Linear Regression Equation for Correction of Cord Blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration

eTable 1. Child Anthropometric Characteristics at Follow-up Visits

eTable 2. Compliance With Vitamin D Supplementation During the 24-Month Study

eTable 3. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, Plasma Ionized Calcium, and Serum Intact Parathyroid Hormone Concentrations During Follow-up by Intervention Group

eTable 4. Vitamin D Status During Follow-up by Intervention Group

eTable 5. Calcium Status During Follow-up by Intervention Group

eTable 6. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Incidence of Infections at 24 Months, With Infections in Seven Subtypes According to Parentally Reported Symptoms or Diagnosis

eTable 7. Characteristics of Parent-Reported Infections per Child During 24-Month Follow-up