Abstract

Background

The diagnostic yield of coeliac disease could be improved by screening in at-risk groups, but long-term benefits of this approach are obscure.

Objective

To investigate health, quality of life and dietary adherence in adult coeliac patients diagnosed in childhood by screening.

Methods

After thorough evaluation of medical history, follow-up questionnaires were sent to 559 adults with a childhood coeliac disease diagnosis. The results were compared between screen-detected and clinically-detected patients, and also between originally asymptomatic and symptomatic screen-detected patients.

Results

In total, 236 (42%) patients completed the questionnaires a median of 18.5 years after childhood diagnosis. Screen-detected patients (n = 48) had coeliac disease in the family and type 1 diabetes more often, and were less often smokers and members of coeliac societies compared to clinically-detected patients, whereas the groups did not differ in current self-experienced health or health concerns, quality of life or dietary adherence. Screen-detected, originally asymptomatic patients had more anxiety than those presenting with symptoms, whereas the subgroups were comparable in other current characteristics.

Conclusion

Comparable long-term outcomes between screen-detected and clinically-detected patients support risk-group screening for coeliac disease. However, asymptomatic patients may require special attention.

Keywords: Children, diagnosis, gluten-free diet, long-term follow-up, quality of life, screening

Key summary

Established knowledge on this subject

Coeliac disease is a common but significantly under-recognized condition.

Screening could be used to improve diagnostic yield, but the long-term benefits of this approach remain unclear.

New findings of this study

Adult Celiac disease patients diagnosed by screening in childhood were comparable to those found because of clinical suspicion in a variety of health outcomes, including adherence to a gluten-free diet and quality of life.

There were also no differences in most characteristics between originally asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, but the former group had more anxiety in adulthood.

Introduction

Over recent decades, coeliac disease has become a common health problem affecting up to 1–3% of the population.1,2 Unfortunately, due to the diverse clinical presentation, most sufferers remain undiagnosed.1,2 Diagnostic efficiency could be improved by risk-group screening, for example among relatives of patients and those with type 1 diabetes.3 Supporting early diagnosis, screen-detected children may already have advanced disease and a subsequent risk of permanent complications such as impaired growth and reduced bone accrual.4–7 Delaying diagnosis until later adulthood predisposes to even more severe maladies, including osteoporotic fractures and refractory coeliac disease.8

Counterweighting the benefits of screening is the burden of demanding treatment. Adhering to a gluten-free diet may negatively affect the quality of life, especially in asymptomatic patients with satisfactory health prior to diagnosis.9 Despite these challenges, there is some evidence from short-term follow-up studies that these children can achieve good dietary adherence and quality of life.7,10–12 However, long-term data in screen-detected coeliac disease patients are very limited.13,14 It is possible that in puberty, the initial “honeymoon period” fades concurrently with the new challenges in life, leading to poor compliance and ill-health.15,16 The paucity of long-term studies has led to prudence when it comes to screening recommendations.17

In the present study, we investigated long-term health and treatment outcomes in adult coeliac disease patients diagnosed in childhood. We were particularly interested in patients detected by at-risk group screening, including those with no apparent symptoms.

Methods

Patients and study design

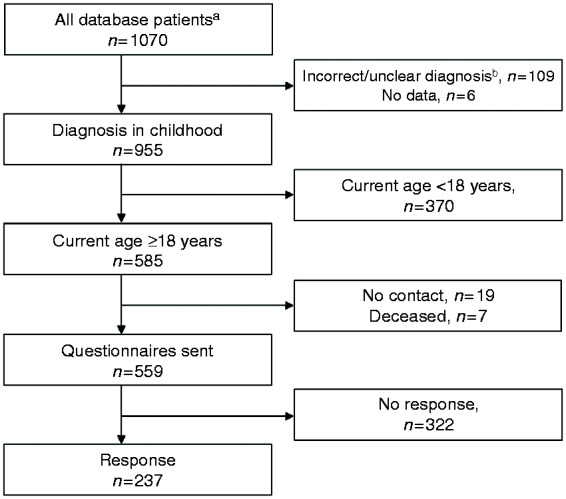

The study was conducted in the Tampere Center for Child Health Research. Data were constructed by combining patients’ answers to questionnaires and personal health information collected from medical records, and, in some cases, by interviews carried out in the context of an earlier study.18 The basic cohort comprised 1070 patients gathered from our research database,18 supplemented by a search with selected diagnosis codes possibly indicating coeliac disease in the patient records of Tampere University Hospital, (Figure 1) a tertiary center with a catchment area of ≈120,000 children. Patients who were diagnosed <18 years of age during 1966–2014 were included for further assessment. After evaluation of medical records, 115 patients were found to be deceased and/or to have an uncertain diagnosis. Of the remaining 955 patients with a proven childhood diagnosis, 559 were currently alive and ≥ 18 years and were sent the study questionnaires. A repeat questionnaire was sent to all non-responders after 2 months (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

aPatients were gathered from our research database and supplemented by a search in the patient records with ICD-7-10 diagnosis codes K90.0, 579A, 579.0, 269.00, 269.98 and 286.00 possibly indicating coeliac disease.

bPatients with an incorrect diagnosis code were found to have, for example, haemophilia A, cow’s milk allergy, primary lactose intolerance or von Willerbrandt disease.

For the subsequent analyses, the responders were divided into: (a) those diagnosed via risk-group screening including patients suffering from type 1 diabetes or other concomitant autoimmune disease, or having relatives with coeliac disease, and (b) those found due to clinical suspicion. Screen-detected patients were further classified into asymptomatic and symptomatic based on the evaluation of symptoms at diagnosis before initiation of a gluten-free diet. All study variables were compared between the above-mentioned groups.

Altogether, 110 healthy adults comprised the control group for comparison of current symptoms and quality of life.19 Their median age was 49 (range 23–87) years and 81% were females. Controls were recruited among the friends and close neighborhood of known coeliac disease patients. None of the controls had suspicion of coeliac disease or known coeliac disease in close relatives.

Medical history

Medical data were collected regarding the clinical and histological presentation of coeliac disease at the time of diagnosis. Information was gathered on the main reason for coeliac disease suspicion and presence of gastrointestinal or extra-intestinal symptoms. Furthermore, possible complications, as well as the presence of coeliac disease-related or other coexisting diseases, and coeliac disease in first-degree relatives were noted. Abnormalities in laboratory values or physicians’ examinations were also recorded, but were considered as signs instead of symptoms.

Poor growth was defined as disturbed height and/or weight development compared to expected growth as described in detail elsewhere.5 Body mass index was calculated as height/weight2 (kg/m2). Anaemia at diagnosis was defined based on the age- and gender-dependent reference values for haemoglobin.

Severity of histological damage was classified based on the pathological report. In our hospital practice, the degree of villous atrophy is evaluated from several well-oriented biopsy samples and further categorized as partial, subtotal or total (Marsh IIIa–c).

Questionnaires

Adult patients completed three surveys, including a specifically designed study questionnaire and two questionnaires evaluating gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life.

The study questionnaire comprised items on sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics such as work and study situation, membership of a coeliac society, regularity of physical exercise, smoking, the presence of children and coeliac disease in the family. The presence of coeliac-related comorbidities and other chronic diseases was evaluated. Current self-experienced health was categorized as excellent, good, moderate or poor, and concerns about health as none/minor or moderate/severe. Furthermore, patients reported their experiences of self-assessed possibly coeliac disease-related symptoms and everyday life restrictions caused by the treatment. Adherence to a gluten-free diet was classified as strict, occasional lapses, regular lapses or no diet, and the frequency of follow-up as regular or none/very occasional.

The Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) questionnaire evaluates health-related quality of life, which is subsequently divided into anxiety, depression, positive well-being, self-control, general health and vitality.20 Altogether, 22 questions are rated from 1 to 6, with higher scores representing better well-being. The total score is the sum of all scores, with the values being between 22 and 132, and the subdimensions are calculated as sums of scores of selected questions. For example, vitality describes a person’s energy level, and the score represents the sum of questions about overall energy, activity, tiredness, and experience of resting after a night’s sleep.20

The Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) consists of 15 questions, which evaluate common gastrointestinal symptoms and their severity.21 Each question is scored via a seven-point Likert scale from asymptomatic (1) to severe symptoms (7). The total score is calculated as a mean of all 15 items. Further, the questions are divided to five subdimensions – abdominal pain, indigestion, diarrhoea, constipation and reflux – which are calculated as means of selected questions.

Ethical aspects

The Regional Ethics Committee of Tampere University Hospital approved the research protocol (Ethical committee code R16091, 31 May 2016), and ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki were followed. Patients participating in earlier interviews or answering the questionnaires fulfilled informed consent.

Statistics

Non-parametric numeric values are reported as medians with quartiles, and compared between the groups with Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests. Bonferroni correction was used in pair-wise post hoc comparisons. Categorized values are reported as numbers and percentages, and compared via χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Significance was set at p value < 0.05. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS version 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Data were available for > 90% of patients unless otherwise stated.

Results

Altogether, 237 (42%) currently adult patients answered the questionnaires (Figure 1). The responders were more often girls, suffered type 1 diabetes less frequently and had more coeliac disease in the family than the non-responders (n = 322), while the groups did not differ significantly in other diagnostic variables such as clinical presentation and the main reason for diagnostic evaluation (eTable 1).

Of 236 responders with available information on diagnostic approach, 48 (20%) had been found by screening and 188 (80%) due to clinical suspicion (Table 1). Screen-detected patients were diagnosed at a significantly older age and more recently. They also had fewer symptoms and growth disturbances at diagnosis, but although their haemoglobin levels were higher, there was no significant difference between the groups in the presence of anaemia. The groups were also comparable in gender and degree of villous atrophy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics at time of childhood diagnosis in currently adult coeliac disease patients.

| Screen-detected patients, n = 48 | Clinically-detected patients, n = 188 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), years | 11.7 (8.1, 14.6) | 8.7 (4.5, 13.3) | 0.004 |

| Year of diagnosis, median (IQR) | 2000 (1992, 2005) | 1997 (1983, 2003) | 0.017 |

| Girls, no. (%) | 33 (68.8) | 130 (69.1) | 0.957 |

| Symptoms a, no. (%) | 21 (43.8) | 151 (86.3) | <0.001 |

| Poor growth, no. (%) | 8 (17.4) | 88 (51.8) | <0.001 |

| Anaemia, no. (%) | 9 (18.8) | 54 (31.2) | 0.091 |

| Haemoglobin, median (IQR), g/L | 130 (121, 134)b | 123 (114, 131)c | 0.015 |

| Degree of villous atrophy, no. (%) | 0.176 | ||

| Partial | 15 (34.1) | 52 (31.0)d | |

| Subtotal | 21 (47.7) | 62 (36.9)d | |

| Total | 8 (18.2) | 54 (32.1)d |

Asymptomatic signs such as poor growth, anaemia and other laboratory abnormalities excluded.

Data available from 32 patients only.

Data available from 158 patients only.

Data available from 168 patients only.

IQR: interquartile range; no.: number.

In subgroup analysis, screen-detected patients presenting with symptoms at diagnosis (n = 21) were younger (9.5 vs 12.1 years, p = 0.098) and more often girls (86 vs 56%, p = 0.025), and had more anaemia (33 vs 7%, p = 0.031) than asymptomatic subjects (n = 27). The subgroups did not differ in the year of diagnosis, presence of growth disturbances, median haemoglobin or degree of villous atrophy (data not shown).

In current comparison at a median of 18.5 years (interquartile range = 12.7, 30.7 years) after the diagnosis, the presence of coeliac disease in the family and type 1 diabetes were more common in screen-detected patients, whereas they were less often members of coeliac societies or current smokers than those found due to clinical suspicion (Table 2). The groups were comparable in age, work and study situation, the presence of other concomitant diseases and children, frequency of physical exercise and body composition (Table 2), as well as in experienced health, concerns about health, presence of symptoms, daily restrictions caused by the treatment, dietary adherence and the implementation of follow-up (Table 3). There were no differences between the subgroups of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in the aforementioned variables (Table 4).

Table 2.

Current sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics and comorbidities in adult coeliac disease patients diagnosed in childhood.

| Screen-detected patients, n = 48 | Clinically detected patients, n = 188 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 26.6 (21.1, 35.2) | 27.2 (22.1, 38.1) | 0.328 |

| Working full-time, no. (%) | 25 (67.6)a | 93 (62.0)b | 0.530 |

| Student, no. (%) | 19 (39.6) | 59 (31.4) | 0.281 |

| Member of coeliac society, no. (%) | 18 (37.5) | 104 (56.5) | 0.019 |

| Coeliac disease in the family, no. (%)c | 31 (64.6) | 72 (40.0) | 0.002 |

| Type 1 diabetes, no. (%) | 13 (27.1) | 5 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Thyroidal disease, no. (%) | 8 (16.7) | 15 (8.2) | 0.103 |

| Other concomitant diseased, no. (%) | 24 (50.0) | 92 (49.5) | 0.947 |

| One or more children, no. (%) | 18 (37.5) | 81 (44.0) | 0.416 |

| Current smoking, no. (%) | 2 (4.2) | 28 (15.2) | 0.042 |

| Quit smoking, no. (%) | 10 (21.3) | 36 (22.0) | 0.921 |

| Regular physical exercisee, no. (%) | 29 (60.4) | 111 (59.0) | 0.863 |

| Body mass index, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 24.6 (22.2, 26.7) | 23.4 (21.3, 26.6) | 0.198 |

Data available for 37 patients only.

Data available for 149 patients only.

First-degree relatives.

For example, other gastrointestinal disease, rheumatic disease, hypertension, cancer, osteoporosis, psoriasis, depression, eating disorder or asthma.

More than three times per week.

IQR: interquartile range; no.: number.

Table 3.

Current health experiences, dietary adherence and follow-up in adult coeliac disease patients diagnosed in childhood.

| Screen-detected patients, n = 48 | Clinically detected patients, n = 188 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experienced health, no. (%) | 0.633 | ||

| Excellent | 12 (25.0) | 45 (24.1) | |

| Good | 30 (62.5) | 104 (55.6) | |

| Moderate | 5 (10.4) | 34 (18.2) | |

| Poor | 1 (2.1) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Concerns about health, no. (%) | 0.137 | ||

| None or minor | 42 (89.4) | 148 (80.0) | |

| Moderate or severe | 5 (10.6) | 37 (20.0) | |

| Symptoms related to coeliac diseasea, no. (%) | 10 (20.8) | 44 (24.2) | 0.627 |

| Daily life restrictionsb, no. (%) | 21 (46.7) | 87 (47.0) | 0.965 |

| Adherence to gluten-free diet, no. (%) | 0.143 | ||

| Strict | 35 (72.9) | 150 (80.2) | |

| Occasional lapses | 7 (14.6) | 24 (12.8) | |

| Regular lapsesc | 6 (12.5) | 8 (4.3) | |

| No diet | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.7) | |

| Follow-up of coeliac disease, no. (%) | 0.467 | ||

| Regular | 14 (29.2) | 45 (24.1) | |

| None or occasional | 34 (70.8) | 142 (75.9) |

Self-assessment.

Perceived as being caused by coeliac disease.

Lapses every week to 1 month.

no.: number.

Table 4.

Current characteristics in subgroups of asymptomatic and symptomatic screen-detected coeliac disease patients diagnosed in childhood.

| Screen-detected |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic, n = 27 | Symptomatic, n = 21 | p value | |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 27.7 (24.5, 35.6) | 25.5 (20.2, 36.8) | 0.513 |

| Coeliac disease in the family, no. (%) | 22 (81.5) | 16 (76.2) | 0.729 |

| Coeliac disease-associated conditiona, no. (%) | 12 (44.4) | 6 (28.6) | 0.260 |

| Other concomitant diseaseb, no. (%) | 12 (44.4) | 12 (57.1) | 0.383 |

| One or more children, no. (%) | 10 (37.0) | 8 (38.1) | 0.940 |

| Experienced health, no. (%) | 0.424 | ||

| Excellent | 5 (18.5) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Good | 17 (63.0) | 13 (61.9) | |

| Moderate | 4 (14.8) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Poor | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Concerns about health, no. (%) | 0.063 | ||

| None or minor | 22 (81.5) | 20 (100) | |

| Moderate or severe | 5 (18.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Symptoms related to coeliac diseasec, no. (%) | 6 (22.2) | 4 (19.0) | 1.000 |

| Daily life restrictionsd, no. (%) | 11 (45.8) | 10 (47.6) | 0.905 |

| Adherence to gluten-free diet, no. (%) | 0.936 | ||

| Strict | 20 (74.1) | 15 (71.4) | |

| Occasional lapses | 4 (14.8) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Regular lapsese | 3 (11.1) | 3 (14.3) | |

| No diet | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Follow-up of coeliac disease, no. (%) | 0.174 | ||

| Regular | 10 (37.0) | 4 (19.0) | |

| None or occasional | 17 (63.0) | 17 (81.0) | |

Type 1 diabetes and/or thyroidal disease.

For example, other gastrointestinal disease, rheumatic disease, hypertension, cancer, osteoporosis, psoriasis, depression, eating disorder or asthma.

Self-assessment.

Perceived as being be caused by coeliac disease.

Lapses every week to 1 month.

IQR: interquartile range; no.: number.

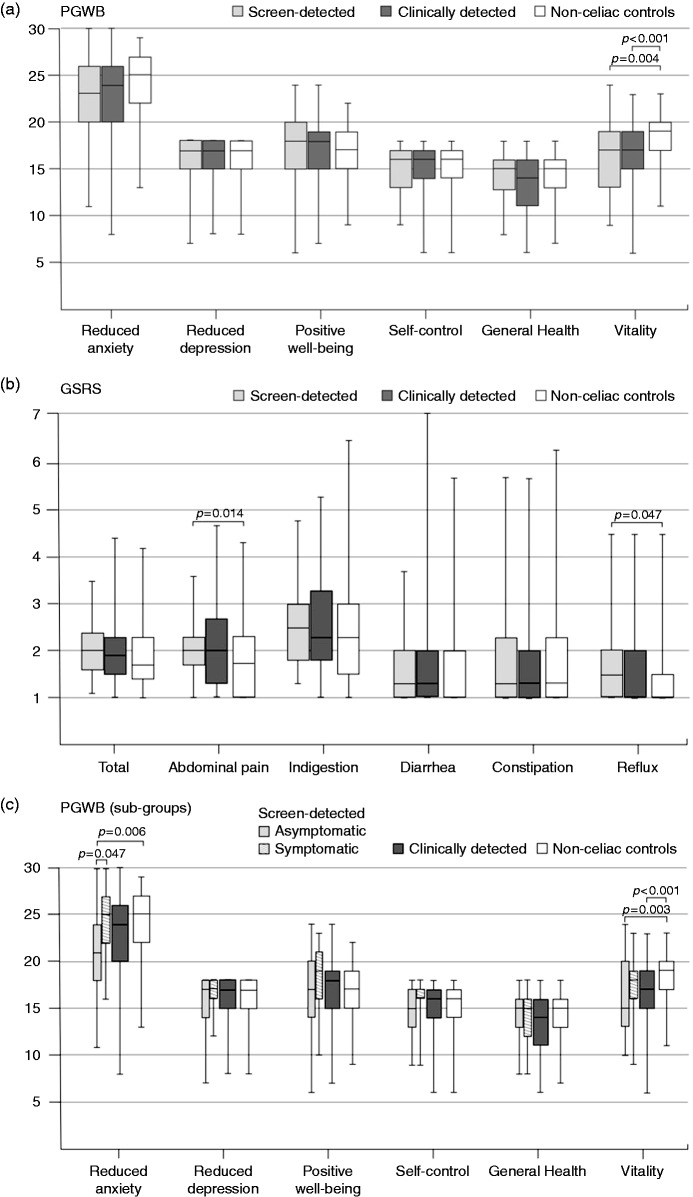

Screen-detected and clinically-detected patients were comparable with respect to current quality of life and symptoms as measured by PGWB and GSRS, but both groups showed lower vitality (Figure 2(a)), and screen-detected patients reported more abdominal pain and reflux (Figure 2(b)), compared to non-coeliac controls. When the analyses were repeated in the subgroups, PGWB anxiety and vitality scores were lower than controls in those who were asymptomatic at diagnosis (Figure 2(c)), while there were no differences in GSRS (data not shown). Increased anxiety was also seen in patients with non-coeliac-related co-morbidities such as malignancies, eating disorders and depression, and in smokers, whereas coexisting type 1 diabetes or thyroid disease were not associated with anxiety and it did not correlate with the time from the diagnosis (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Psychological General Well-Being and Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale subscores in adults.

Coeliac disease patients were first divided into those diagnosed in childhood via risk-group screening (n = 48) and due to clinical suspicion (n = 188) ((a) and (b)), and the group of screen-detected patients was then further divided into those who were asymptomatic (n = 27) and symptomatic (n = 21) at diagnosis (c). The corresponding values for 110 non-coeliac adults are shown for comparison. Higher scores indicate either better psychological well-being ((a) and (c)) or more severe symptoms (b). Differences between the groups were evaluated by Kruskal–Wallis test and Bonferroni correction was used in pair-wise post hoc comparisons. Median (horizontal line), interquartile range (box), and minimum and maximum values (vertical line) of the scores are presented for each patient group.

PGWB: Psychological General Well-Being; GSRS: Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale.

Discussion

Our main finding was that coeliac disease patients diagnosed in childhood by screening and due to clinical suspicion are comparable in most measured adulthood health outcomes. The results give further support to screening among at-risk children. However, a subgroup of patients asymptomatic at diagnosis are at an increased risk of later anxiety and may require special support during follow-up. Whether the benefits of screening overcome the possible burden of the dietary treatment cannot be answered with certainty by this study design, but it is important to bear in mind that asymptomatic screen-detected patients are also at risk of developing permanent complications.

As regards to the rationale of screening, it was of particular importance that we found no differences in dietary adherence between screen- and clinically-detected coeliac disease patients. Earlier long-term studies investigating this issue are scant. In a study by Roma et al., 88% of screen-detected children adhered to a gluten-free diet compared to 58% of the whole-study cohort after 4 years on the diet.22 Fabiani et al. reported a mere 23% of screen-detected adolescents maintaining a strict diet after 5 years compared to 68% of those found because of malabsorptive symptoms.15 Besides these paediatric studies, we and Mahadev et al. have observed similar dietary adherence patterns between cohorts of screened and clinically-detected adults, in which some individuals were diagnosed as children.23,24 However, subjects with a childhood diagnosis were not evaluated separately. A few more adult studies have assessed adherence in originally paediatric patients, but it is unclear whether screen-detected subjects were included.13,25

Drawing firm conclusions from this limited number of studies is challenging, but adherence is likely to be markedly dependent on the variability of the prevailing knowledge of coeliac disease and the availability of gluten-free products.26,27 Furthermore, it is important to realize that Fabiani et al. published their study as far back as 2000, since which the gluten-free diet has become popular and easier to maintain.28 More studies in different populations are needed, but we here demonstrated that, in favorable circumstances, the achievement of good long-term dietary adherence is possible in screen-detected patients. Furthermore, screened patients had similar or even better health-related behavior, when for example smoking was less common among them. However, one explanation for this could be that a higher proportion of those with type 1 diabetes were screen-detected compared to those that were clinically found, since these patients are particularly advised to avoid smoking strictly to prevent diabetes-associated long-term complications.

A gluten-free diet is necessary to achieve remission in coeliac disease, but can be challenging in many respects. Here, screen-detected and clinically identified patients did not differ in quality of life or their experience of everyday life restrictions caused by the treatment. Nevertheless, dietary restriction might be particularly burdensome in screen-detected patients, who often consider themselves healthy before the diagnosis and may lack the experience of a positive treatment response.29,30 Earlier, Fabiani et al. observed screen- and clinically-detected adolescents to be comparable regarding the experience of anxiety and depression.15 In addition, van Koppen et al. reported comparable quality of life between healthy controls and 32 screen-detected children after 10 years on a gluten-free diet.14 However, even at that point, these patients were still in early adolescence (<15 years) and the treatment was mainly the parents’ responsibility.

Clinical presentation and particularly the absence of symptoms may affect the experience of an individual with coeliac disease even more than the original reason for diagnostic evaluation.17 Hitherto, the lack of evidence on the long-term benefits of screening, particularly in asymptomatic patients, has led to considerable caution, and, for example, the US Preventive Services Task Force has demanded more prospective studies before releasing screening recommendations.17 However, in practice, the required studies are particularly laborious and may take decades to complete with sufficient power. Our center has a long tradition in coeliac disease research, which has enabled us to obtain a unique cohort of adults diagnosed by childhood screening from as far back as the 1970s.18,31 Another issue that must be considered when discussing screening is that it is not a synonym for an absence of symptoms, as many of these patients are not asymptomatic but simply unrecognized,7,10,23 as was seen in almost half of our patients. As regards truly asymptomatic cases, it was noteworthy that they did not report more restrictions in daily life or most aspects of quality of life.

There are already important arguments favoring coeliac disease screening in childhood. Notwithstanding the less severe clinical presentation, we observed that screen-detected and even asymptomatic children can already have severe histological damage. This confirms our earlier findings and demonstrates that these otherwise unidentified patients are at risk of permanent complications, similarly to those found in clinical practice.7 In fact, some asymptomatic children already had signs of anaemia and poor growth, and others have reported that such patients can suffer from osteopaenia and underachievement.4,32 Furthermore, although more studies are needed, an early-initiated gluten-free diet might reduce the risk of other autoimmune diseases.33,34

Although most of our results support childhood screening, certain challenges remain. We found an absence of symptoms to predispose to increased anxiety in adulthood, which is in accordance with our previous observation in a small subgroup of asymptomatic adults.9 It is logical that these individuals find it difficult to adapt to the diagnosis and life-long dietary restriction, particularly if its justification is unclear. Alternatively, owing to the absence of warning symptoms, they might be afraid of inadvertent gluten exposure and the subsequent development of complications. It is therefore important to explain why treatment could be rational in asymptomatic coeliac disease, and to underline the good prognosis when dietary adherence is successful.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of the present study is the large cohort of adults with biopsy-proven coeliac disease diagnosed in childhood. We also succeeded in collecting comprehensive medical data at diagnosis together with data on a variety of current sociodemographic, health and lifestyle factors. The use of validated questionnaires in the evaluation of symptoms and quality of life increases the reliability and generalizability of the results.9,19–21,23,27

There were also limitations. A relatively low response rate to questionnaires predisposes to selection bias. This common problem in postal surveys was likely further aggravated by the long interval between the diagnosis and the current study. For example, it is possible that patients who had better dietary adherence were more likely to answer the questionnaires and thus skewed the results. However, the fact that responders and non-responders were comparable in most features reduces the risk of bias. Another limitation was incomplete data in a part of the study variables at the time of diagnosis. Finally, the non-coeliac controls were older and more often female than coeliac disease patients, which may have affected the comparability of quality of life.35

Conclusions

We have provided evidence, which was previously lacking, regarding the long-term health outcomes in screen-detected coeliac disease. Of particular importance was that even asymptomatic children can attain good adulthood quality of life while maintaining a strict gluten-free diet. However, physicians should bear in mind that, in some patients, the absence of symptoms at childhood diagnosis may predispose to later anxiety. We do not regard this as a counterargument against screening, but encourage physicians to take clinical presentation into account when planning long-term follow-up. At this point, we feel that affected children and their families at least have a right to be aware of the underlying coeliac disease and be in a position to consider treatment options. Without screening, a substantial number of sufferers remain undiagnosed, with often unrecognized symptoms and an increased risk of complications.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for Long-term health and treatment outcomes in adult coeliac disease patients diagnosed by screening in childhood by Laura Kivelä, Alina Popp, Taina Arvola, Heini Huhtala, Katri Kaukinen and Kalle Kurppa in United European Gastroenterology Journal

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This study was supported by Competitive State Research Financing of Tampere University Hospital, the Foundation for Pediatric Research, the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation, the Mary and Georg C. Ehrnrooth Foundation, the Maud Kuistila Foundation, the Maire Rossi Foundation and the Finnish Medical Foundation.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from patients participating in earlier interviews or answering the questionnaires.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by Regional Ethics Committee of Tampere University Hospital (Ethical committee code R16091, 31 May 2016).

References

- 1.Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1538–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myléus A, Ivarsson A, Webb C, et al. Celiac disease revealed in 3% of Swedish 12-year-olds born during an epidemic. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009; 49: 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludvigsson JF, Card TR, Kaukinen K, et al. Screening for celiac disease in the general population and in high-risk groups. United European Gastroenterol J 2015; 3: 106–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björck S, Brundin C, Karlsson M, et al. Reduced bone mineral density in children with screening-detected celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017; 65: 526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nurminen S, Kivelä L, Taavela J, et al. Factors associated with growth disturbance at celiac disease diagnosis in children: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol 2015; 15: 125–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cellier C, Flobert C, Cormier C, et al. Severe osteopenia in symptom-free adults with a childhood diagnosis of coeliac disease. Lancet 2000; 355: 806–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivelä L, Kaukinen K, Huhtala H, et al. At-risk screened children with celiac disease are comparable in disease severity and dietary adherence to those found because of clinical suspicion: A large cohort study. J Pediatr 2017; 183: 115–121.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viljamaa M, Kaukinen K, Pukkala E, et al. Malignancies and mortality in patients with coeliac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis: 30-year population-based study. Dig Liver Dis 2006; 38: 374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ukkola A, Mäki M, Kurppa K, et al. Diet improves perception of health and well-being in symptomatic, but not asymptomatic, patients with celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinos S, Kurppa K, Ukkola A, et al. Burden of illness in screen-detected children with celiac disease and their families. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 55: 412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webb C, Myléus A, Norström F, et al. High adherence to a gluten-free diet in adolescents with screening-detected celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015; 60: 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordyke K, Norström F, Lindholm L, et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescents with screening-detected celiac disease, before and one year after diagnosis and initiation of gluten-free diet, a prospective nested case-referent study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 142–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Leary C, Wieneke P, Healy M, et al. Celiac disease and the transition from childhood to adulthood: A 28-year follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99: 2437–2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Koppen EJ, Schweizer JJ, Csizmadia CGDS, et al. Long-term health and quality-of-life consequences of mass screening for childhood celiac disease: A 10-year follow-up study. Pediatrics 2009; 123: e582–e588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabiani E, Taccari L, Rätsch I-M, et al. Compliance with gluten-free diet in adolescents with screening-detected celiac disease: A 5-year follow-up study. J Pediatr 2000; 136: 841–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurppa K, Lauronen O, Collin P, et al. Factors associated with dietary adherence in celiac disease: A nationwide study. Digestion 2012; 86: 309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for celiac disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2017; 317: 1252–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kivelä L, Kaukinen K, Lähdeaho M-L, et al. Presentation of celiac disease in Finnish children is no longer changing: A 50-year perspective. J Pediatr 2015; 167: 1109–1115.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paarlahti P, Kurppa K, Ukkola A, et al. Predictors of persistent symptoms and reduced quality of life in treated coeliac disease patients: A large cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol 2013; 13: 75–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimenäs E, Carlsson G, Glise H, et al. Relevance of norm values as part of the documentation of quality of life instruments for use in upper gastrointestinal disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1996; 221: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, et al. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res 1998; 7: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roma E, Roubani A, Kolia E, et al. Dietary compliance and life style of children with coeliac disease. J Hum Nutr Diet 2010; 23: 176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahadev S, Gardner R, Lewis SK, et al. Quality of life in screen-detected celiac disease patients in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 50: 393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paavola A, Kurppa K, Ukkola A, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life in screen-detected celiac disease. Dig Liver Dis 2012; 44: 814–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Högberg L, Grodzinsky E, Stenhammar L. Better dietary compliance in patients with coeliac disease diagnosed in early childhood. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003; 38: 751–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White LE, Bannerman E, Gillett PM. Coeliac disease and the gluten-free diet: A review of the burdens; factors associated with adherence and impact on health-related quality of life, with specific focus on adolescence. J Hum Nutr Diet 2016; 29: 593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viljamaa M, Collin P, Huhtala H, et al. Is coeliac disease screening in risk groups justified? A fourteen-year follow-up with special focus on compliance and quality of life. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 22: 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newberry C, McKnight L, Sarav M, et al. Going gluten free: The history and nutritional implications of today’s most popular diet. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2017; 19: 54–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uutela T, Hannonen P, Kautiainen H, et al. Positive treatment response improves the health-related quality of life of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009; 27: 108–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leffler DA, Kelly CP. The cost of a loaf of bread in symptomless celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2014; 147: 557–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mäki M, Kallonen K, Lähdeaho M-L, et al. Changing pattern of childhood coeliac disease in Finland. Acta Paediatr 1988; 77: 408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verkasalo MA, Raitakari OT, Viikari J, et al. Undiagnosed silent coeliac disease: A risk for underachievement? Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 1407–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ventura A, Magazzù G, Greco L. Duration of exposure to gluten and risk for autoimmune disorders in patients with celiac disease. SIGEP Study Group for Autoimmune Disorders in Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 1999; 117: 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sategna Guidetti C, Solerio E, Scaglione N, et al. Duration of gluten exposure in adult coeliac disease does not correlate with the risk for autoimmune disorders. Gut 2001; 49: 502–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casellas F, Rodrigo L, Vivancos JL, et al. Factors that impact health-related quality of life in adults with celiac disease: A multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 46–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for Long-term health and treatment outcomes in adult coeliac disease patients diagnosed by screening in childhood by Laura Kivelä, Alina Popp, Taina Arvola, Heini Huhtala, Katri Kaukinen and Kalle Kurppa in United European Gastroenterology Journal