Abstract

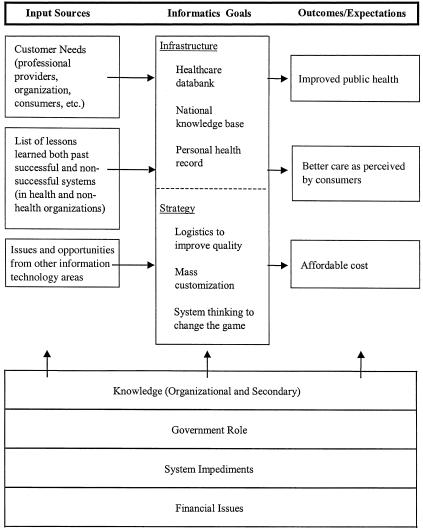

Informatics and information technology do not appear to be valued by the health industry to the degree that they are in other industries. The agenda for health informatics should be presented so that value to the health system is linked directly to required investment. The agenda should acknowledge the foundation provided by the current health system and the role of financial issues, system impediments, policy, and knowledge in effecting change. The desired outcomes should be compelling, such as improved public health, improved quality as perceived by consumers, and lower costs. Strategies to achieve these outcomes should derive from the differentia of health, opportunities to leverage other efforts, and lessons from successes inside and outside the health industry. Examples might include using logistics to improve quality, mass customization to adapt to individual values, and system thinking to change the game to one that can be won. The justification for the informatics infrastructure of a virtual health care data bank, a national health care knowledge base, and a personal clinical health record flows naturally from these strategies.

The 1999 Scientific Symposium of the American College of Medical Informatics (ACMI) was devoted to sharpening our understanding of how to better focus the energy of the health informatics community to achieve its audacious goals.1 The program design was based on the premise that mainstream information technology should be used where the information needs related to health care are similar to those in other industries. Lessons from other industries might also show us how informatics might have the greatest impact on health. Health informatics could then direct its implementation efforts to where the highest payback might be expected and its research to areas where health has different requirements for information support.

This white paper summarizes the major points from the symposium discussion.

Symposium Process

Prior to the symposium, three topics were selected for presentation and ACMI Fellows were chosen to lead the discussion of each topic. Each morning session followed a format beginning with the presentation of ideas by the topic leader and other topic group members.2,3,4 This was followed by a discussion among all symposium participants. During the large-group discussion, key questions and issues were identified. The highest-priority questions and issues were divided among small groups to discuss in breakout sessions. Each group reported to all the symposium members, and then a summary was presented by the ACMI president or the symposium facilitator. The topics, by day, were as follows:

Day 1—Identify information or informatics problems that are unique to health.

Where has health applied an idea or technology from elsewhere directly? Where has adaptation been required? Where has a totally new solution been required?

Which information or informatics problems are specific to health, and which are not?

Is there a common theme to what makes a problem health-specific?

Day 2—Identify mainstream, non-health efforts that can be leveraged by health informatics.

Are there robust solutions outside health that may be more effective than ongoing efforts within health informatics?

How might health informatics influence the direction of these non-health-specific efforts to make them better meet health needs?

Day 3—Identify where health informatics can make the most difference to the health system.

Where has informatics resulted in a breakthrough in other industries?

What constitutes a breakthrough, and what about the effort that resulted in the breakthrough?

Where has health informatics research caused a breakthrough, or where might it do so in the future?

What would be required for the breakthrough to occur? What would be the potential impact? How might the impact be measured?

Differentia of the Health Industry

Organizational Structures

Academic health centers are rooted in entrepreneurial structures that focus on education and research. These activities are expected to translate into quality health care. However, the organizational structure of an academic center does not provide the accountability needed to manage to this objective. Various stakeholders have their own priorities. They share a core of resources. Sometimes they do come together as a community of interest with a measurable overarching goal, when they perceive that their priorities will be served. Sometimes they do not come together, especially if they do not feel that they are a part of the process. As a result, many people in academic centers do not have a touchstone against which to manage tradeoffs in quality, range of services, and cost.

All health organizations tend to have a disconnect between administrative functions and clinical decision makers. The former are responsible for financial stability, infrastructure, process quality, and efficient use of resources. The latter are supposed to observe enterprise-wide practices when appropriate, but also act as independent knowledge workers when necessary. Many current administrative processes for bringing the independent practitioners in line with best practice are imposed as overhead, reducing provider productivity and customer satisfaction.

Nature of Health

Improving health is a societal goal. Most costs are paid by government or business through insurance, not by individual consumers. Government sets policies about health entitlements, but government is not willing to fund the market cost for those services. Faced with a disconnect between entitlement and funding, health providers first shift the cost of these services to business through charges to insurance, then increase the efficiency of service, and finally reduce the range or quality of service. The focus on increasing access and decreasing cost places policy makers, payers, providers, and consumers at odds with one another. This hinders the provision of long-term solutions based on quality improvement.

Health is a perception. It represents the result of the complex interaction between an individual's genetics, brain, environment, and habits. For example, while some individuals may be able to carry on fairly normal activities despite severe loss of 80 percent of their pulmonary capacity, others may be disabled by minor arthritis. Careful reproduction of a process that results in a good outcome for the first will not help the second. Managing to a good outcome requires adaptation to the individual, and it may not be possible to find a gold standard for good outcomes among individuals.

Variability of Biological Systems

Biological systems are inherently variable. For example, biological systems are compartmentalized. The cellular structure and active pumps are needed to permit change between high and low energy states with minimal generation or consumption of heat. As a result, each person consists of many “factories,” each with its own copy of genetic material—material that mutates and evolves randomly. Contrast this variability to the reproducibility of physical systems. Because of the variability, the number of formulas and data points required to document each instantiation of a biological system increases several fold. As a result, the number of conditions that need to be handled by uniform data standards is much greater than that required by standards for physical systems.

Implications for Informatics and Information Technology Requirements

All industries are facing market pressure, a rapid change in knowledge and its organization, and rationing of scarce resources. They need security technologies, connectivity, and information standards. The health informatics community should be able to reuse work performed by the government and the mainstream information technology industry to meet health's needs in these areas.

Health industry requirements are more demanding in a number of areas. Such areas include implications of violations of privacy, support for personal values, responsibility for public health, management of populations, complexity of the knowledge base and terminology, perception of high risk and pressure to make critical decisions rapidly, poorly defined outcomes, and support for diffusion of power. In these areas health informatics may take a lead in developing solutions that can then be reused in less demanding industries.

Demands arising from the disconnects outlined above seem unique to the health care industry. For example, it is unusual to have to respond to market forces on the one hand while providing for consumers who are different from the payers on the other. The conflict between mixed missions and a demand for one-stop shopping is similar. These are areas where those in the health informatics community—as system thinkers—may provide leadership in developing a better model for the health care system, one that better aligns incentives and clarifies outcomes.5

Although health is an information-intensive industry, and most people agree that information is power, it is natural to resist information technology, because it changes roles and the social order. This reaction may be offset by improving communication between the informatics community and the health providers. If the technology is seen as problem-solving technology, it will be more readily accepted.

Bringing Lessons from Industry into Health Informatics

Delivering Results

Industry has used information technology in ways that often directly affect revenue. Because of this direct connection, industry is willing to invest in information technology. Also because of this tie, the investments are made in reliable, production-quality systems and simple things are done well. Data are valued. Code is not valued. Legacy systems are not replaced so long as they handle transactions adequately and can be mined for data needs. At WalMart, the tie between the business strategy and the information strategy is so important that the chief executive officer is a former chief information officer.

Health care does not appear to explicitly value information. The tie between information and improved financial outcomes has not been established. Where are the examples of health systems that have over-whelmed their competition through strategic application of information technology? Information technology has made the managed care movement possible. Why has it not had the same impact on clinical care? Can informatics help hospitals stop losing money? Is information technology the right tool to fix the political, economic, and social problems of the current health system?

The informatics community needs to develop compelling visions that communicate the feasibility of a better health system at an affordable cost. These visions may build on the audacious goals for informatics that were identified during the 1998 ACMI Scientific Symposium.1 There appears to be continued consensus in the informatics community that a virtual health care database, a national health care knowledge base, and personal clinical health records would make a better health system. However, it is less clear that the resulting health system would be better enough to justify the cost or that these informatics-based resources would be the best way to meet the goals of the health system. These visions need to make the benefits of the proposed system clear and establish an explicit link between promised benefits on the one hand and informatics and information technology as key enablers on the other.

A list of “wins” that have been made possible by informatics and information technology might best support further investment. Examples include charge collection and billing, automated laboratory testing and reporting, scheduling, inventory control, new imaging modalities, and secondary data use. Each win might be explained by its cost, return on investment, critical success factors, and alternatives to an information technology solution.

The visions may be used to depict the art of the possible, and the wins may show what is doable, in an education effort targeted at chief executive officers, chief information officers, providers, and patients. The informatics community needs to join these groups at the table as they make decisions and bring them into informatics discussions.

Consumer Health: An Example of Visioning

People think of different things when consumer health is discussed. There are at least three vectors of consumer health that can be represented, or facets that can serve as departure points for action.

Laying on of hands. The physician is responsible for the patient's health, and seeing a physician is reassuring to a patient even if what the physician can provide is technically not effective. The ability of the patient to transfer responsibility to the physician is often sufficient to promote healing. In this case the patient does not want to take any responsibility for his or her therapy or health.

Shared responsibility. Here the patient is expected to take some responsibility for his or her health or therapy. By providing information about a diagnosis and therapy or about how to maintain a healthy lifestyle, the physician expects the patient to be able to understand, interpret, and act on medical information. There is a certain arrogance in the assumption that all patients have this ability and want this responsibility.

New vision. A totally new vision of consumer health is needed to make a difference. It is naive to assume that just providing consumers with increased access to medical information will make a difference. What is needed is a new relationship between people and the health system. Providers may become coaches instead of intermediaries. Content may be specifically tailored to consumers, adapted for individual learning styles and values, and presented in a way that they can more readily incorporate into their daily activities.

Despite these three different ways of viewing the issue, it is still possible to identify several key issues that need to be addressed.

Empowerment. Health care often requires difficult, complex decisions, and consumers need some em powerment to take an active part in the process. This implies more authority over decisions about their health program and responsibility for carrying out the program.

Change in the knowledge-as-power relationship. To the extent that knowledge is power, the sharing of information with the patient or consumer changes the relationship between the provider and the patient.

Collaboration to develop tools, content, and uses. Health informatics should learn from learning theories how presentation, format, language, and cultural icons influence learning and create tools that allow these factors to be adjusted for the individual. The health research community should create the content needed to guide consumer decisions. The education and health provider communities should develop programs to incorporate the tools and content into the living patterns of consumers.

Government policy and standards. The federal government is already working on major areas in this domain—privacy legislation, security of patient information, patient access to a personal medical record, and standards for representing information in the medical record.

Only after discussion of competing visions of consumer health, and the issues involved, do we get an indication of the value to be gained by moving forward. At that point, the informatics and information technology community could do a number of tasks to promote the vision, including:

Build systems that support the shared goals of health providers and consumers.

Develop tools that are generalizable and scalable.

Design the interface for transferring information from the health provider to the patient.

Increase research on the utility of Internet health resources, such as chat groups and lists.

Invest in existing resources. Incremental development based on existing resources can begin the process of increasing access to health information by consumers.

All too commonly, however, informatics starts with the tasks. Without the overarching vision and value proposition, it is hard to get commitment of adequate resources. Good informatics work is necessary, but it is not sufficient to improve the health system.

Nurturing Innovation

The government has a role in seeding research, but the relationship between the investment and the ultimate outcome may not be direct. For example, DARPA invested in a series of small projects and included funds to support communication between investigators. These investments ultimately resulted in the Internet, but the investment was not directed to that end. There was a long lag time between the creation of the Internet and its widespread application, because the application awaited the development of the standards and tools that make up the World Wide Web. As a key consumer in health care and information technology, government is in a position to pull innovative products into the market place.

It is hard to predict where the breakthroughs will occur and what will really matter in the future. Simplicity in the user interface is a key ingredient. Timing is all-important. A real or perceived crisis creates openings that can be exploited, if there is external technical momentum, if the number of true stakeholders is limited, and if key players get on board. The acceptance of XML by HL7 is a case in point.

Genomics and informatics may come together to produce a breakthrough in the translation of scientific knowledge into improved health. A similar advance may be achieved by using information technology to explore individual needs and values, to provide customized solutions, and to empower the individual to play an active role in treatment and monitoring.

Risks of Borrowing from Industry

The more the change, the higher the potential benefit and the greater the risk. It is easier for management to accept change and risks when faced by a crisis. It is important to understand the situation that an industry was in at the time of a successful change and identify what enabled that change to occur. With that understanding, it is possible to see whether an analogous situation exists in another industry or how other critical success factors might be substituted.

Every major change has unanticipated or unintended consequences, and these need to be expected and managed. In most cases, a change results in a dip before an improvement is seen. There is a tradeoff between time pressure and investment in the future. For example, training may be adequate to get a practice out the door quickly, but education is required to ensure ongoing learning and proper reaction to the unexpected.

Where May Informatics Make the Biggest Difference to Health?

Using Logistics to Improve Quality

The goal for any enterprise can be stated as “getting the right thing done, the right way, at the right time, by the right person.” This same goal can be articulated in regard to high-quality health care. In fact, it holds for achieving high quality in all three areas of effort of an academic health center—patient care, education, and research. If we could accomplish this goal in health care, we could provide individuals with high-quality care and at the same time save substantial personal and financial resources. If we could accomplish it in health education, we would graduate better-trained, lifelong learners and, in research, advance the knowledge base of biomedicine. Given this drive for high quality in all three pursuits of the academic health center, the goal for health informatics is to build the tools or develop the systems that will help achieve this level of quality.

To accomplish this it might be useful to create a value/mission model that would identify both the options available to any academic health center and the areas where informatics would be important for their accomplishment. Such a model could be used to identify where informatics can make a significant difference in achieving the strategy selected by a particular center. By doing this, we could concentrate our efforts in a few key areas and demonstrate the value of these efforts to improving the quality of the goals of the academic health center.

▶ is a brief conceptual model chart of the four “rights”—thing, way, time, and person. An example from the Patient Care column illustrates the approach. The first step is to articulate the vision, or the “right thing” the organization wants to accomplish. In this case, the right thing is not a moral judgment but a decision on the part of the health care organization of its core mission and value. If that vision is to provide population-based medicine, then certain other actions need to be taken to provide a high-quality service. The “right way” might include capturing data from all encounters with the population that is served and analyzing them for common conditions. This database would enable the organization to develop standard treatment protocols or practice guidelines for the conditions that are most likely to be encountered. The “right time” would encourage the development of educational/preventive health care programs. And the “right person” would incorporate the patient and the consumer/public in the overall health care process.

Table 1.

Conceptual Value/Mission Model for Academic Health Centers

| Value: Quality | Mission: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Care | Education | Research | |

| Right Thing (Vision) | ▪ Carriage trade | ▪ Specialists | ▪ Advancing and communicating knowledge |

| ▪ Individualization | ▪ Family Practice Physicians | ||

| ▪ Mass customization | ▪ Academic Physicians | ▪ Outcome research | |

| ▪ Population-based medicine | ▪ Allied Health Professionals | ||

| ▪ Regional health model | |||

| Right Way (Which, How) | ▪ Traditional medicine | ▪ Lecture | ▪ Laboratory-based research |

| ▪ Complementary medicine | ▪ Problem-based learning | ▪ Department/discipline | |

| ▪ Evidence-based medicine | ▪ Small group | ▪ Interdisciplinary institutes | |

| ▪ Standards of care | ▪ Community-based learning | ▪ Academic health center | |

| ▪ Practice guidelines | ▪ Apprenticeships | ||

| ▪ Protocols | |||

| ▪ Learning organization | |||

| ▪ Person empowerment | |||

| ▪ Shared responsibility | |||

| Right Time (When) | ▪ Acute care on demand | ▪ Undergraduate medical education | ▪ Undergraduate education |

| ▪ Preventive medicine | ▪ Graduate education | ||

| ▪ Public health education | ▪ Graduate medical education | ||

| ▪ AA/BA education | |||

| ▪ Just-in-time learning | |||

| ▪ Just-in-time training | |||

| Right Person (Who) | ▪ Physician | ▪ Physicians | ▪ Faculty |

| ▪ Integrated staff | ▪ Other faculty | ▪ Interdisciplinary team | |

| ▪ Skill mix | |||

| ▪ Patient | |||

| ▪ Consumer/public | |||

The task for informatics is to design the information resources and systems that enable such a health care organization to accomplish its vision and goals in the most effective way. This would include achieving the goal of satisfaction on the part of the health care consumers as well as the staff of the organization. If informatics can demonstrate how this vision could be accomplished at a high-level of quality and in a cost-efficient manner, then health care will have been improved considerably. By demonstrating the value of informatics in support of this vision, we will have helped health care become more responsive to its customers and society's needs.

Can Mass Customization Be Applied to Health Care?

What aspects of health care might be customized? Health profiles may be personalized on the basis of clinical findings, risk factors, and such. Patient records may be adapted to reflect problems, level of education, and ability to track progress directly. Personal values relevant to diagnostic and treatment options can be modeled and used to tailor protocols. Communication strategies may reflect the patient's preferences to receive information via fax or e-mail or in a face-to-face meeting and may be adapted to reflect the extent to which scientific language is understood.

What payoffs might be obtained through mass customization? Patients may be more satisfied with their health programs. Service planning could be more rational. Patients will be more likely to comply with recommendations that reflect their values. Patient involvement should lead to improved quality, accuracy, relevance, and timeliness of health data. The increase in quality should result in reduced costs, increased revenue, and improved efficiency and should translate into social good.

The issues that must be resolved before mass customization of health care is feasible include the validity of databases, including both personal and public health information; models of health care and patients that provide direction regarding which aspects or variables could be customized; incentives and tools to support collaborating, both for providers and patients; safeguards against fraud; and re-establishment of the public trust.

The most obvious juncture between mass customization and informatics is in the database structure and function needed to support mass customization. Another area where health informatics applications can support mass customization is the explication of models to patients. Finally, informatics can provide the telecommunication tools and knowledge management strategies that facilitate communication with patients in manners unique to each patient.

The Game Must Change for Informatics' Audacious Goals to Be Feasible

A standards-based, patient-centered longitudinal database is implicit in every vision expressed by the informatics community. The following attributes of the current health care system impede the development of such a database:

It is insurance-oriented. The notion behind insurance is that many people pay a small amount so that a few people can use it when they need it. This provides a disincentive for services that everyone will use, except when those services (e.g., mammography) can be proved to decrease costs elsewhere.

It is disease-oriented. Many consumers want little to do with the health care system until they get sick.

It is bottom-line oriented. One can argue that the true “payers” for health care services are employees who generate wealth for the companies that buy the insurance, but since the insurance companies (and, for Medicare, the government) do write the checks, they are in practical terms the payers.

Setting the Agenda for Health Informatics

▶ provides a framework for setting the agenda for health informatics. The agenda should acknowledge the foundation provided by the current health system and the role of financial issues, system impediments, policy, and knowledge in effecting change. The desired outcomes should be compelling, such as improved public health, improved quality as perceived by consumers, and lower costs. Strategies to achieve these outcomes should derive from the differentia of health, opportunities to leverage other efforts, and lessons from successes inside and outside the health industry. Examples might include using logistics to improve quality, mass customization to adapt to individual values, and system thinking to change the game to one that can be won. The justification for the informatics infrastructure of a virtual health care data bank, a national health care knowledge base, and a personal clinical health record flows naturally from these strategies.

Figure 1.

Context for setting the agenda for health informatics.

Acknowledgments

Patricia Brennan, Mark Frisse, Walter Panko, and Mark Tuttle organized the three plenary discussions and facilitated the summarization. Robert Braude, William Braithwaite, William Hersh, Tom Lincoln, and Kathleen McCormick provided reports from breakout groups.

This paper is based on discussions among the fellows of the American College of Medical Informatics (ACMI) during the 1999 ACMI Scientific Symposium, held Feb 12-14, 1999, in Tucson, Arizona.

References

- 1.Greenes RA, Lorenzi NM. Audacious goals for health and biomedical informatics in the new millennium. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(5):395-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panko WB. Clinical care and the factory floor. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999:6(5):349-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuttle MS. Information technology outside health care: what does it matter to us? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999:6(5):354-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frisse MC. The business value of health care information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999:6(5):361-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozbolt JG. Personalized health care and business success: can informatics bring us to the promised land? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999:6(5):368-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]