Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a bioactive lipid that can function both extracellularly and intracellularly to mediate a variety of cellular processes. Using lipid affinity matrices and a radiolabeled lipid binding assay, we reveal that S1P directly interacts with the transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ. Herein, we show that S1P treatment of human endothelial cells (ECs) activated a luciferase-tagged PPARγ-specific gene reporter by ∼12-fold, independent of the S1P receptors. More specifically, in silico docking, gene reporter, and binding assays revealed that His323 of the PPARγ ligand binding domain is important for binding to S1P. PPARγ functions when associated with coregulatory proteins, and herein we identify that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1 (PGC1)β binds to PPARγ in ECs and their progenitors (nonadherent endothelial forming cells) and that the formation of this PPARγ:PGC1β complex is increased in response to S1P. ECs treated with S1P selectively regulated known PPARγ target genes with PGC1β and plasminogen-activated inhibitor-1 being increased, no change to adipocyte fatty acid binding protein 2 and suppression of CD36. S1P-induced in vitro tube formation was significantly attenuated in the presence of the PPARγ antagonist GW9662, and in vivo application of GW9662 also reduced vascular development in Matrigel plugs. Interestingly, activation of PPARγ by the synthetic ligand troglitazone also reduced tube formation in vitro and in vivo. To support this, Sphk1−/−Sphk2+/− mice, with low circulating S1P levels, demonstrated a similar reduction in vascular development. Taken together, our data reveal that the transcription factor, PPARγ, is a bona fide intracellular target for S1P and thus suggest that the S1P:PPARγ:PGC1β complex may be a useful target to manipulate neovascularization.—Parham, K. A., Zebol, J. R., Tooley, K. L., Sun, W. Y., Moldenhauer, L. M., Cockshell, M. P., Gliddon, B. L., Moretti, P. A., Tigyi, G., Pitson, S. M., Bonder, C. S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate is a ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ that regulates neoangiogenesis.

Keywords: transcription factor, endothelial, neovascularization

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a potent lipid mediator produced by 2 sphingosine kinase (SK) enzymes, SK-1 and SK-2, and regulates diverse physiologic and pathologic processes mainly by binding to 5 specific GPCRs: S1P1–5 [reviewed in a study by Pitson (1)]. S1P is an abundant lysophospholipid in human blood with concentrations of 200 nM detected in plasma and 500 nM in serum (2), and due to its amphiphatic nature, S1P also exists free in the cytosol (3). Within cells, gradients of S1P, as well as sphingosine and SK, exist and correlate with their localization in organelle membranes [reviewed in Hla et al. (4)]. Endothelial cells (ECs) express S1P1–3 (5, 6), and extracellular S1P signaling through these receptors promotes EC survival (7), migration (8), proliferation, and angiogenesis (9). However, there is increasing evidence of S1P having multiple intracellular functions independent of the S1P receptors [reviewed in (10)]. These include physiologic roles on the vasculature, with our own data suggesting that intracellular S1P regulates endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) differentiation (6, 11), activation of the integrin α5β1 (12), mediates histamine-induced neutrophil recruitment (13), and enhances CD31-dependent EC survival (14). Intracellular targets for S1P have only recently begun to emerge and include histone deacetylases [HDACs; (15)] 1/2, the E3 ubiquitin ligase TNF receptor-associated factor-2 [TRAF2; (16)], prohibitin 2 [PHB2; (17)], and cIAP2 (18). Herein, we describe the first interaction of S1P with the transcription factor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ.

PPARs are ligand-inducible transcription factors that belong to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily and have well-described roles in the regulation of lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis (19). The PPAR subfamily consists of 3 isoforms: PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ. PPARs facilitate transcription as a complex, existing as a heterodimer with retinoid-x receptors [RXRs; (20)]. Upon ligand binding, specific coactivator proteins are recruited to the PPAR:RXR complex, driving its translocation into the nucleus where it binds to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor response elements (PPREs) upstream of target genes to mediate their transcription (20). PPARγ has 2 isotypes, γ1 and γ2, that differ by a 30-amino acid extension at the N terminus of PPARγ2 (21), conferring divergent activation capacities (22). Levels of PPARγ2 are high within adipose tissue, whereas PPARγ1 is ubiquitously expressed at low levels (21). Genetic deletion of PPARγ1 is embryonic lethal (23), whereas deletion of PPARγ2 alone causes only minimal alterations in lipid metabolism and has been linked to nutritional status and insulin sensitivity (24). In contrast, PPARγ1 has been linked to rat mesangial cell proliferation and differentiation (25), as well as being differentially regulated in CD4+ T lymphocytes (26).

A number of natural ligands for PPARγ have been identified and include phospholipids, such as lysophosphatidic acid [LPA; (27)]. The thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of antidiabetic drugs, including rosiglitazone, troglitazone, and pioglitazone, is synthetic PPARγ agonists that are clinically used to improve insulin sensitivity and fat metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [T2DM; (28)]. There is an emerging role for PPARs in the development and activation of the blood vasculature. For example, TZDs increase the number and improve the function and migratory activity of EPCs in patients with T2DM (29, 30). The TZD, rosiglitazone, promotes the differentiation of angiogenic progenitor cells toward an endothelial lineage and attenuates restenosis in a mouse model of angioplasty (31). Reduced restenosis is attributed to the agonist-induced anti-inflammatory properties of PPARγ on the vasculature with significant attenuation of proinflammatory adhesion molecules and secreted mediators (32, 33). Similarly, cilostazol activates PPARγ to enhance re-endothelialization in a rat model of balloon carotid artery denudation (34). Interestingly, in healthy HUVECs and rat corneas, the natural PPARγ ligand 15-deoxy-D12,14 prostaglandin J2 as well as the TZDs (rosiglitazone and ciglitazone) significantly attenuated blood vessel development in vitro and in vivo (35).

Herein, we demonstrate that S1P binds to PPARγ via its ligand binding domain (LBD). Moreover, this interaction occurs via a different site to that used by other known PPARγ lipid ligands, and we show that PPARγ protein levels are elevated following endogenous S1P production. We also show that in ECs, the coactivating factor bound to PPARγ following S1P activation is peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1 (PGC1)β and that alteration of this complex attenuates vascular development in vitro and in vivo. With previous data suggesting that SK-1/S1P regulate EPC fate and function, this study suggests for the first time that it is the unique complex of S1P:PPARγ:PGC1β that may underpin these effects. With S1P and PPARγ known contributors to the progression of malignant diseases, this complex may represent a new target for the regulation of EC function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical statement

The collection of primary HUVECs was given ethical clearance from the Royal Adelaide Hospital Human Ethics Committee (Adelaide, SA, Australia). The collection of primary human umbilical cord blood (UCB) for use in this study was given ethical clearance from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Children, Youth and Women’s Health Service (North Adelaide, SA, Australia), and informed written consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of South Australia Pathology (Adelaide, SA, Australia) and conform to the guidelines established by the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes.

Human nonadherent endothelial forming cell isolation

Nonadherent endothelial forming cells (naEFCs) were isolated as previously described from starting a mononuclear cell (MNC) population (36). Briefly, human UCB was collected, and MNCs were isolated using density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep; Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway). naEFCs were enriched via a CD133 magnetic sort utilizing the autoMACS Pro Separator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Cells were cultured on fibronectin (50 mg/ml; Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN, USA) in endothelial growth medium (EGM-2; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) complete with BulletKit (Lonza) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Bovogen, VIC, Australia), VEGF (5 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), IGF-1 (0.005 ng/ml; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; 1 ng/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and ascorbic acid (0.1 mM; Sigma-Aldrich). While in culture, the nonadherent cells were transferred to a new precoated fibronectin well with fresh EGM-2 medium (plus supplements) and cultured for 4 d. Expansion of these cells was undertaken following CD133 magnetic sort, where naEFCs were cultured under serum-free conditions in CellGro Serum-free Stem Cell Growth Medium (CellGenix GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) supplemented with 10 ng/ml thrombopoietin (Sigma-Aldrich), 40 ng/ml stem cell factor, and 40 ng/ml Flt3 ligand (both from R&D Systems) at 0.5–1 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were kept under continuous culture conditions where they were counted using Trypan blue and a hemocytometer, and CellGro medium was added to adjust the cell concentration back to 0.5–1 × 106 cells/ml.

EC isolation

HUVECs were isolated and cultured from human umbilical cords by collagenase digestion as previously described (37). ECs were used at passage 2–4.

Overexpression of SK-1 in human ECs

Adenoviral constructs for SK-1 and empty vector (EV) were generated as previously described (14) and used to transduce ECs (6).

Creation of plasmid DNA constructs

pLenti4/TO/IRES (pLenti4/tetracycline operator/internal ribosome entry site) enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was generated as previously described (11). FLAG-tagged wild-type (WT) PPARγ1 (38) and PPARγ1(H323A) (39) were cloned into pLenti4/TO/IRES EGFP following digestion with SpeI and XhoI. Sequencing and restriction analysis verified the integrity and orientation of the inserted PPARγ1 cDNA.

Cell lines

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and COS-7 cells were maintained in DMEM (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS, and U937 human monocytes were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS. Cell lines were originally acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

SK-1 enzymatic assay

SK-1 activity was determined from clarified whole-cell lysates as previously described (40). Briefly, D-erythro sphingosine (Biomol, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) solubilized by 0.05% Triton X-100 and [γ32P]]ATP were used as substrates to incubate with the whole-cell lysates. The radioactively labeled phospholipid S1P was resolved by thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

Pull downs with lipid affinity matrices

All pull downs were undertaken in lipid binding buffer [LBB; 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.35% Nonidet P40 substitute (Sigma-Aldrich)] using bovine serum albumin (BSA)-blocked (LBB plus 1 mg/ml BSA for 30 min at 4°C) control, sphingosine, or S1P affinity matrices (Echelon Biosciences Incorporated, Salt Lake City, UT, USA). Full-length human His-tagged PPARγ purified from Escherichia coli was incubated with lipid affinity matrices for 2 h at room temperature before being washed (3× with LBB) prior to immunoblot analysis. For the PPARγ1(H323A) mutant pull downs, cells were harvested in LBB with the addition of complete protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics Corp.), 0.5 mM 4-deoxypyridoxine, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and sonicated in a water bath. Lysates were clarified immediately before preclearing with control matrices. The precleared lysate was then added to the BSA-blocked matrices and incubated for 2 h at 4°C prior to washing with LBB (3×) and immunoblot analysis.

[32P]S1P synthesis

Radiolabeled S1P was synthesized using 100 μM Triton X-100 solubilized sphingosine (Enzo Life Sciences), 1 mM ATP, 1 μCi [γ32P]]ATP, and 100 ng recombinant SK-1 (41) in assay buffer [100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mM NaF] and was incubated for 1 h at 37°C.

[32P]S1P and PPARγ1 binding assay

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with pLenti4/TO/IRES EGFP and pLenti4/TO/Flag-PPARγ1/IRES EGFP using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Whole-cell lysates from transfected cells were sonicated and centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove insoluble material. Flag-tagged PPARγ1 protein was immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag antibody (M2; Sigma-Aldrich) with the immunocomplexes captured by protein A Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). The immunoprecipitated PPARγ1 (beads:Flag-PPARγ1) were washed twice with lysis buffer before resuspension (50% slurry). Synthesized [32P]S1P was incubated with beads:Flag-PPARγ1 for 2 h at 4°C with agitation. Beads:Flag-PPARγ1 were washed twice, and bound [32P]S1P was solvent extracted and resolved by TLC. The TLC plate was exposed to a storage phosphor screen and quantified by Typhoon 9410 phosphorimager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), as described previously (40), with the spot intensity within the linear range of detection.

PPRE-luciferase reporter assay

Human ECs were transfected with the acyl-coenzyme A oxidase PPRE-luciferase (PPRE-Luc) reporter gene construct and a Renilla-luciferase (Renilla-Luc) control vector, using TransPass HUVEC (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Transfected ECs were treated with S1P at 50 nM, 100 nM, and 1 μM with or without the S1P receptor inhibitors JTE013 (10 µM; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) or VPC23019 (1 µM; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL, USA) for 4 h. COS-7 cells were used in mutant PPARγ PPRE-Luc assays. Briefly, COS-7 cells were transfected to express PPRE-Luc, Renilla-Luc, and pcDNA3.1 -EV, -PPARγ1 WT, -PPARγ1 R288A, -PPARγ1 H323A, or -PPARγ1 H449A (39) using Lipofectamine 2000. Transfected COS-7 cells were treated with 5 μM S1P for 5 h. Luciferase activities were measured with the Steady-Glo Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System on a GloMax-Multi+ Microplate luminometer following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Luciferase activity values were calculated relative to Renilla controls.

In silico docking of S1P into the ligand binding pocket of PPARγ

Molecular ligand docking studies were carried out using AutoDock Vina (42). The crystal structure of PPARγ combined with magnolol [Protein Data Bank (PDB) identification number 3R5N] was chosen as the structure of reference protein. All water molecules in the crystal structure were removed, and the protein charges were assigned using MMF94 force field in molecular operating environment (MOE; Chemical Computing Group Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada). The binding site was defined as a box centered around the bound ligand, which is large enough to cover the active site. Prior to docking, S1P was built and optimized in MOE. Ligand and receptor were prepared for docking using Raccoon AutoDock VS (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA). Docking simulations were performed at default settings. The best docking pose based on the lowest AutoDock Vina score was energy optimized, and interactions were visualized in MOE. Figures were produced using PyMOL freeware (Schrödinger, Portland, OR, USA).

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from naEFCs, ECs, and U937 cells treated for 16 h with or without S1P, LPA, or rosiglitazone (all from Cayman Chemical) using the RNeasy Micro Plus Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A total of 0.5–1 μg total RNA was converted into first-strand cDNA using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. QuantiTect SYBR Green was used for quantitative PCRs (qPCRs), and samples were analyzed on Rotor-Gene thermocyclers (Qiagen). Cycling parameters began with a 10-min hold at 95°C followed by cycling at 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s, for 45 cycles. Oligonucleotide sequences are as follows: CYCA (cyclophilin A), 5′-AGACAAGGTCCCAAAGACAGCAGA-3′ and 5′-TGTGAAGTCACCACCCTGACACAT-3′; PGC1β, 5′-GCGTGGTGTACATTCAAAATC TCT-3′ and 5′-GCACCTCGCACTCCTCAATC-3′; PAI-1, 5′-GCCTCGGTGTTGGCCA TGCT-3′ and 5′-GGGGGCCATGCCCTTGTCATC-3′; CD36, 5′-CCAGTTGGAGACCTGC TTATC-3′ and 5′-TCTGTAAACTTCTGTGCCTGTT-3′; aP2 (adipocyte fatty acid binding protein 2), 5′-GGAAAGTCAAGAGCA CCATAAC-3′ and 5′-GCATTCCACCACCAGTTTATC-3′; and PPARγ, 5′-GCCTGCATCTCCACCTTATT-3′ and 5′-ACCCTTGCATCCTTCACAAG-3′. Data obtained were analyzed using Rotor-Gene Analysis Software version 6 (Qiagen). All samples were independently analyzed at least 3 times for each gene. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the comparative quantitation method normalized to the housekeeping gene CYCA.

Immunoprecipitation

Clarified lysates from ECs treated with 5 μM S1P were incubated with PPARγ antibody (E-8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) overnight at 4°C with constant agitation. The immunocomplexes were captured with protein A Sepharose beads for 2 h at 4°C with constant agitation. Clarified lysates from naEFCs and ECs were incubated with PGC1β antibody (H-300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and magnetic protein G beads (Miltenyi Biotec) for 2 h at 4°C with constant agitation. Immunoprecipitation was undertaken as per each manufacturer’s instructions (GE Healthcare Life Sciences and Miltenyi Biotec), and beads were washed 3 times in lysis buffer. The eluate was subjected to SDS-PAGE with proteins transferred to nitrocellulose membranes.

Immunoblotting

Protein expression was detected using the following antibodies: anti-PGC1β (H-300); anti-PPARγ (H-100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-tubulin (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom); anti-His (Abcam); anti-Flag M2 and anti-PAI-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-CD36 (Abcam); anti-aP2 (A-FABP; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); and anti-β actin (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). All antibodies were detected with anti-rabbit IRDye 800 or 680 and visualized using the Li-Cor Odyssey (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). In the naEFC and EC PGC1β immunoprecipitate, PPARγ was detected using anti-rabbit TrueBlot secondary antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals, Limerick, PA, USA), and in the PPARγ1 mutant pull downs, Flag was detected using anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase, both using an ECL kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Immunofluorescence protein detection

Immunofluorescence analysis was undertaken as previously described (13). Cells were stained using PPARγ (H-100; 1:200) and DAPI. Images were taken at ×60 using the Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 confocal microscope (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Fluorescence intensity was analyzed using Olympus Analysis Life Science imaging software, version 3.0 (Tokyo, Japan).

1,19-Dioctadecyl-3,3,39,39-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlo-rate-Ac-LDL uptake assay

naEFCs treated with 5 μM GW9662 for 20 h were incubated at 37°C for 4 h with 10 μg/ml 1,19-dioctadecyl-3,3,39,39-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlo-rate-Ac-LDL (DiI-Ac-LDL; Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA, USA). The percentage of cells within each population that incorporated DiI-Ac-LDL was assessed with flow cytometry using FACSAria II with FACSDIVA (both from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Further analysis was performed using FCS Express 4 Flow Cytometry: Research Edition (De Novo Software, Glendale, CA, USA).

In vitro Matrigel tube formation assay

ECs were treated with 10 μM troglitazone (Sigma-Aldrich) or vehicle (DMSO) for 20 h prior to seeding onto Matrigel (2 × 104 per well; Corning, Tewksbury, MA, USA). For the S1P experiments, ECs were seeded at a suboptimal density (1.2 × 104 per well) on Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel (Corning) in low-serum medium (2% fetal calf serum). GW9662 (1 µM; Cayman Chemical) was given to the cells 30 min before S1P treatment (5 and 10 µM; Cayman Chemical) and seeding into Matrigel. The Matrigel tube formation assay was executed as previously described (6). Images were taken at 6 h using phase-contrast microscopy (Olympus IX70 Inverted Microscope). Images at ×10 magnification were used for publication. Tube formation was quantified by counting the number of tubes per well using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Generation and S1P analysis of Sphk1−/−Sphk2+/− mice

Sphk1−/−Sphk2+/− mice were bred from Sphk1−/− and Sphk2−/− mice as previously described (43). Plasma from these and WT C57Bl/6 mice was obtained via cardiac puncture, and the S1P was analyzed using fluorescent derivatization followed by HPLC, as described previously (44), with data presented as means ± sd (n = 3).

In vivo Matrigel plug assay

In vivo Matrigel plug assays utilized 6- to 8-wk-old male C57Bl/6 mice. High-concentration Matrigel Matrix (500 μl; Corning) with 2 mg/ml bFGF and 50 U/ml heparin (Sigma-Aldrich) were injected subcutaneously into both flanks of C57Bl/6 WT and Sphk1−/−Sphk2+/− mice. For the PPARγ inhibitor experiment, the C57Bl/6 WT mice received a Matrigel plug (bFGF and heparin) with 1 μM GW9662 (Cayman Chemical) or 5 µM troglitazone (Cayman Chemical) in one flank and a control plug with vehicle (DMSO) in the alternate flank. At 7 d postinjection, Matrigel plugs were removed, processed, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Stained Matrigel plugs were imaged using a Nanozoomer (Hamamatsu Photonics, Shizuoka, Japan). Representative images are at ×10 magnification. NDP.view software (Hamamatsu Photonics) was used to calculate the area of each Matrigel plug and count vessel-like structures to express the mean number of vessel-like structures per square millimeter.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as means + sem from at least 3 experiments, unless otherwise indicated. Unless otherwise stated, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was performed to determine statistical significance with values of P < 0.05 considered significant.

RESULTS

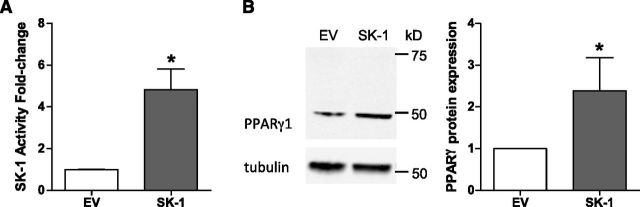

Overexpression of SK-1 induces PPARγ expression

Transcription factors tightly regulate cellular phenotype and function by controlling a specific suite of genes and regulatory pathways. With increasing evidence that the transcription factor, PPARγ, is involved in EC biology, and our own work showing that SK-1 regulates EC differentiation (6, 11), we asked whether manipulation of SK-1 modulates PPARγ expression in ECs. As shown in Fig. 1A, adenoviral-mediated overexpression of SK-1 in ECs resulted in a significant increase in SK-1 activity. This increase in SK-1 activity resulted in a significant induction of PPARγ protein expression (Fig. 1B). Importantly, SK-1 overexpression appeared to elevate the PPARγ1 isoform, rather than PPARγ2 as a single band was evident at ∼50 kDa (PPARγ1 was predicted to be at ∼53 kDa), whereas a doublet or larger band corresponding to PPARγ2 (predicted to be at ∼56 kDa) was not detected.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of SK-1 in ECs increases PPARγ protein expression. A) SK-1 activity of ECs transduced with SK-1 was determined by the enzymatic SK-1 assay. Data are expressed as normalized SK-1 fold changes + sem (n = 3). B) Expression of PPARγ protein in SK-1-transduced ECs was visualized by immunoblotting. Quantified data are expressed as normalized mean band intensities ± sem (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

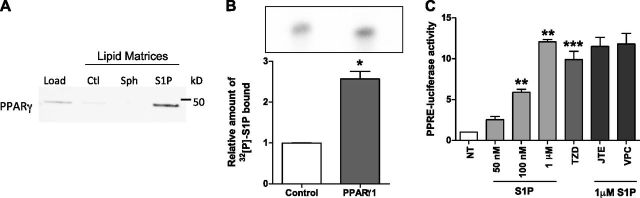

S1P is an intracellular ligand for PPARγ

Because LPA, a lipid with structural similarity to S1P, has been previously shown to bind PPARγ (27), we next investigated whether S1P might also be a ligand for PPARγ. Control, sphingosine, and S1P lipid affinity matrices were incubated with recombinant PPARγ with bound PPARγ detected by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 2A, S1P was detected when bound to the S1P lipid affinity matrices, whereas very little-to-no PPARγ was detected on the control and sphingosine lipid affinity matrices. In addition, the S1P and PPARγ1 interaction was also confirmed using over-expressed PPARγ1 immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1) and incubated with in vitro-synthesized [32P]S1P. Bound [32P]S1P was then extracted, separated by TLC, and quantified using phosphorimaging. As shown in Fig. 2B, a significantly higher level of [32P]S1P was observed bound to PPARγ compared to the EV control.

Figure 2.

S1P is a ligand for PPARγ. A) His-tagged human recombinant PPARγ (Load) was incubated with control (Ctl), sphingosine (Sph), and S1P affinity matrices. Bound PPARγ was resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with an anti-His antibody. Representative blot from n = 3. B) Relative amount of [32P]S1P bound to Flag-PPARγ1 was quantified by [32P]S1P spot intensity. Data are expressed as means + sem (n = 3). *P < 0.05. C) Human ECs transfected with PPRE-Luc were treated with S1P at 50 nM, 100 nM, and 1 μM or the TZD (troglitazone) at 1 μM; or 1 µM S1P with 10 µM JTE013 (JTE; mean from n = 2 plus range) or 1 µM VPC23019 (VPC; mean from n = 2 plus range) for 5 h. Results are fold activation relative to Renilla controls. Data are expressed as means + sem (n = 3). **P < 0.005 and ***P < 0.01 compared to no treatment (NT).

Having shown that S1P can directly interact with PPARγ1, we next investigated whether S1P could activate the transcriptional activity of PPARγ. To execute these experiments, we transiently expressed a PPRE-Luc reporter in ECs and stimulated the cells with increasing concentrations of S1P for 5 h. The concentrations of S1P ranged from that known to be restricted to surface receptor binding (45) as well as that documented to increase intracellular pools of S1P (16, 46). The synthetic PPARγ TZD (troglitazone) agonist was used as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 2C, when PPRE-Luc-expressing ECs were stimulated with S1P at 50 nM, 100 nM, and 1 μM, a dose-dependent increase in PPRE-Luc reporter activity occurred. Notably, the 1 μM S1P stimulated an equivalent increase in luciferase activity to that observed with 1 μM of the synthetic ligand TZD (troglitazone; Fig. 2C). Moreover, we investigated the role of S1P1–3 GPCRs in S1P-induced activation of PPARγ in this assay using the S1P receptor inhibitors JTE031 (S1P2) and VPC23019 (S1P1 and S1P3). As depicted in Fig. 2C, in repeated experiments, the addition of JTE031 or VPC23019 had no effect on 1 µM S1P-induced luciferase activation in ECs.

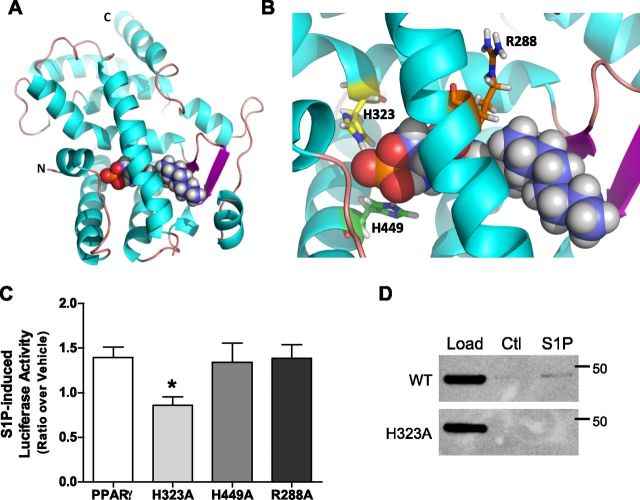

S1P interacts with the PPARγ ligand binding pocket via His323

To establish the residues that mediate S1P binding to PPARγ1, we employed computational modeling to reveal a predicted model of the S1P:PPARγ1 interaction (Fig. 3A). The predicted docking of S1P suggested hydrogen bond interactions between the phosphate head group of S1P and His323 and His449 of helix 12 within the PPARγ1 LBD (Fig. 3B). Of note, S1P was not predicted to interact with Arg288, a residue known to mediate the interaction of LPA with PPARγ (39).

Figure 3.

S1P interacts with the PPARγ ligand binding pocket via His323. A) Computational modeling was utilized to predict the interaction between S1P and the PPARγ LBD (PDB entry 3R5N). S1P is represented in the LBD as spheres colored by atom type (C is in purple, H is in gray, P is in orange, and O is in red) within residues 207–474 of the PPARγ LBD (ribbon structure: α-helices are cyan; and β-sheets are magenta). B) Magnification of the PPARγ binding pocket reveals predicted interacting residues His323 (orange; H323) and His449 (green; H449). Arg288 (orange; R288) is not predicted to interact with S1P. C) Validation of the predicted interacting residues was determined via luciferase assay using WT PPARγ and alanine substitution mutants of the predicted residues (H323A, H449A, and R288A) following 5 µM S1P for 5 h. Luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla controls. Data are represented as mean ratios of luciferase activity of vehicle to S1P + 5 µM sem (n = 3). *P < 0.005 compared to PPARγ WT. D) S1P binding to PPARγ1(H323A) was assessed using cell lysates from HEK293T cells over-expressing PPARγ1 WT or PPARγ1(H323A) in a lipid affinity matrix binding assay. Bound PPARγ was resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with an anti-Flag antibody. Representative blot from n = 3.

To determine whether the aforementioned residues are integral to the activation of PPARγ1 by S1P, alanine-substituted PPARγ1 mutants were screened in a PPRE-Luc assay and compared to WT PPARγ1. To ensure a robust response and high intracellular S1P levels (16, 46), 5 µM S1P was used to stimulate the WT and mutant PPARγ in this assay. Figure 3C shows that mutation of His323 to alanine (H323A) reduced PPARγ activation in response to S1P by ∼30%. Contrary to what was predicted from the aforementioned modeling, S1P activation of His449 to alanine (H449A) mutant was equivalent to WT PPARγ1 (Fig. 3C). In addition, overexpression of the PPARγ1 with Arg288 mutated to alanine (R288A) did not alter S1P-induced reporter activity when compared to WT PPARγ1. Importantly, as shown in Fig. 3D, the PPARγ1(H323A) mutant exhibited reduced binding to S1P lipid affinity matrices when compared to WT PPARγ1. Taken together, these data suggest that S1P may bind to and activate PPARγ1 through predicted hydrogen bonding between the phosphate head group of S1P and His323 within the PPARγ1 binding pocket, with other thus far unidentified residues likely to be important for this interaction.

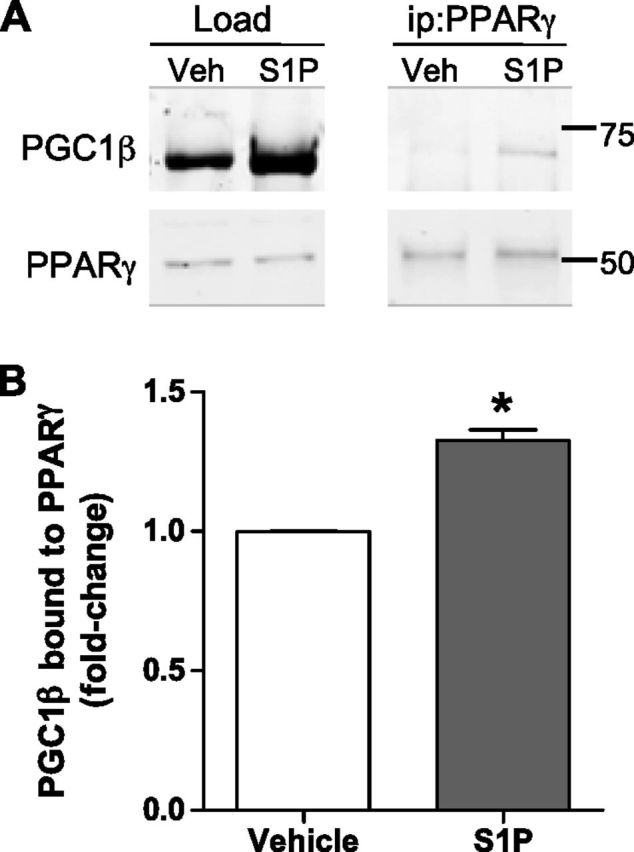

S1P enhances the association of PPARγ and the putative coactivator, PGC1β, in ECs

Having identified that S1P is a ligand for PPARγ, we next investigated the greater PPARγ complex induced by S1P (47). With a known role for PPARγ and S1P in ECs, we used these cells in immunoprecipitation experiments to identify putative PPARγ coactivators. As shown in Fig. 4A, treatment of ECs with 5 µM S1P resulted in an increase in PGC1β protein expression. Immunoprecipitation of PPARγ from these lysates showed an increase in the amount of the PPARγ and PGC1β complex in S1P-treated cells. Importantly, normalization of immunoprecipitated PGC1β to the input revealed a significant increase in PGC1β associated with PPARγ compared to vehicle control (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that S1P induces the association of PPARγ with PGC1β in ECs.

Figure 4.

S1P induces PGC1β to bind to PPARγ in ECs. PPARγ and PGC1β association in response to S1P was determined by PPARγ immunoprecipitation of EC lysates treated with 5 μM S1P (20 h). A) Representative blot and (B) PGC1β protein from PPARγ immunoprecipitation (ip) normalized to PGC1β load are shown. Veh, vehicle. Data are expressed as PGC1β band intensity fold changes + sem (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

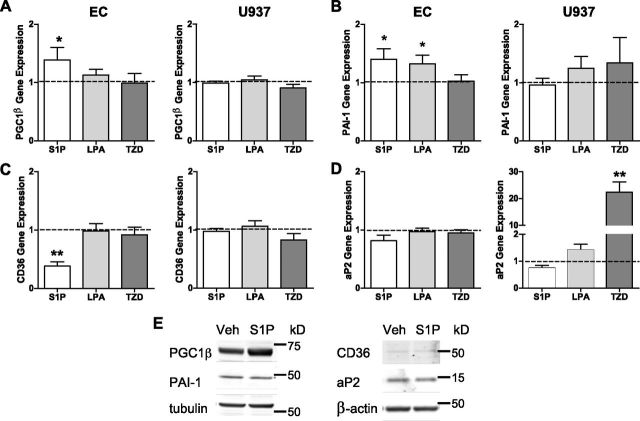

Treatment of ECs and U937 cells with PPARγ agonists modulates differential gene and protein expression

Having revealed that S1P binds to PPARγ, we next wanted to determine whether different cell types might confer gene regulation specificity in response to different PPARγ ligands. Herein, we compared ECs to the monocytic U937 cell line with the treatment of 3 different PPARγ ligands (S1P, LPA, and the synthetic TZD, rosiglitazone) because PPARγ has also been identified to regulate monocyte differentiation (48). Having previously identified the coassociation of PGC1β with PPARγ following S1P administration, we first compared expression of PGC1β in ECs and U937 cells. In Fig. 5A, mRNA expression of PGC1β in ECs was shown to be significantly increased in response to S1P treatment. A slight increase in PGC1β was also seen with LPA treatment, but not with TZD (rosiglitazone). Interestingly, expression of PGC1β in U937 cells did not increase following treatment with S1P, LPA, or TZD (rosiglitazone; Fig. 5A). Analysis of the endothelial gene PAI-1 in ECs revealed an increase in gene expression in response to S1P or LPA treatment, with no change observed following TZD (rosiglitazone) treatment (Fig. 5B). Expression of PAI-1 in U937 cells was not altered by S1P, LPA, or TZD (rosiglitazone; Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Treatment of ECs and U937 cells with PPARγ results in differential gene expression. Expression of (A) PGC1β, (B) PAI-1, (C) CD36, and (D) aP2 in ECs and U937 cells in response to 16-h treatment with 5 μM S1P, 5 μM LPA, and 5 μM rosiglitazone (TZD) was determined by qPCR. Gene expression was normalized to CYCA. Data are expressed as mean relative fold changes + sem with vehicle (depicted as dotted line) (n = 6). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 determined by unpaired t test compared to vehicle. E) Protein expression in ECs in response to 5 µM S1P for 16 h was determined using SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Representative blot from n = 3.

Two well-described PPARγ target genes include the macrophage receptor scavenger, CD36 (48), and aP2 (49). In ECs, CD36 mRNA expression was significantly reduced in response to S1P treatment, whereas LPA and TZD (rosiglitazone) did not alter CD36 expression (Fig. 5C). Of note, in the U937 cells, CD36 gene expression was not altered by S1P, LPA, or TZD (rosiglitazone; Fig. 5C). As shown in Fig. 5D, expression of aP2 in ECs was not shown to be regulated by S1P, LPA, or TZD (rosiglitazone). Interestingly, aP2 expression in U937 cells was not altered with S1P or LPA, whereas there was a significant increase in aP2 gene expression observed in response to TZD (rosiglitazone; Fig. 5D). These data suggest that gene regulation of PPARγ-induced gene transcription is controlled at the level of PPARγ ligand and host cell.

To ensure that this change in PPARγ target gene expression in ECs also resulted in modulation of protein expression, immunoblot analysis was undertaken of ECs treated with S1P. As depicted in Fig. 5E, PGC1β protein expression, like gene expression, was enhanced with S1P treatment. Interestingly, the increase in PAI-1 gene expression seen with S1P treatment did not translate to protein. Moreover, the reduction in CD36 gene expression was not seen in response to S1P treatment at the protein level and may be due to the low amount of CD36 protein detected. As expected, no change in aP2 expression was seen in ECs following S1P treatment. Together, these data suggest that in ECs, gene modulation of PGC1β by S1P translates to protein expression.

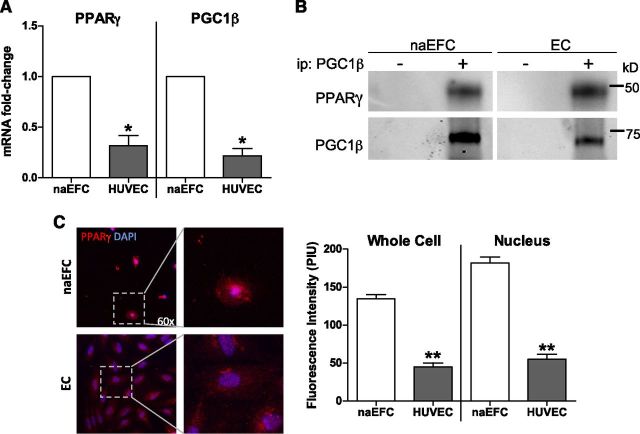

PPARγ and PGC1β are differentially expressed by ECs and their progenitors

Having established a novel PPARγ transcriptional complex within ECs of S1P:PPARγ:PGC1β, we next wanted to confirm PPARγ as a functional regulator in both naEFCs and ECs. A recent microarray analysis of naEFC and EC gene expression showed PPARγ and PGC1β expressed by both cell types (36). In Fig. 6A, this was further confirmed by qPCR. Of note, there was significantly less PPARγ and PGC1β gene expression detected within the mature EC population. To confirm whether PGC1β and PPARγ directly interact within naEFCs and ECs, magnetic immunoprecipitation of endogenous PGC1β from protein lysates of expanded naEFCs and ECs was undertaken, and interacting proteins were detected by immunoblotting. Antibody detection of PPARγ revealed coimmunoprecipitation with PGC1β in both the expanded naEFCs and ECs (Fig. 6B). These data support our hypothesis of PGC1β directly interacting with PPARγ within cells of the endothelial lineage. Interestingly, immunofluorescence experiments confirmed increased PPARγ protein present within naEFCs and its localization in the nuclear compartment, whereas in ECs, PPARγ expression was largely localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 6C). Quantification of PPARγ protein fluorescence intensity confirmed that naEFCs contain significantly more PPARγ within their nucleus compared to ECs, indicating the presence of transcriptionally active PPARγ. Moreover, S1P treatment of ECs resulted in the translocation of PPARγ into the nucleus (Supplemental Fig. 2), with the translocation not analyzed in naEFCs due to the existing nuclear localization detected in these cells (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

PPARγ and PGC1β are expressed and associate in naEFCs and ECs. A) Endogenous PPARγ and PGC1β gene expression was determined in naEFCs and ECs by qPCR. Gene expression was normalized to CYCA. Data are expressed as means + sem (n = 3). *P < 0.001. B) An interaction between PGC1β and PPARγ was determined by PGC1β immunoprecipitation from naEFC and EC protein lysates. Bound PPARγ and confirmation of PGC1β pull down were detected via immunoblotting compared to no antibody control. Representative blot from n = 3. C) PPARγ protein in naEFCs and ECs was assessed by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Cells were immunostained for PPARγ (Alexa Fluor 594 in red) and the nucleus (DAPI in blue). PPARγ protein intensity was quantified using pixel intensity units (PIU). Images were taken at ×60 for publication, with single cells magnified to show PPARγ localization. Data are expressed as mean PIU + sem (n = 3). **P < 0.05.

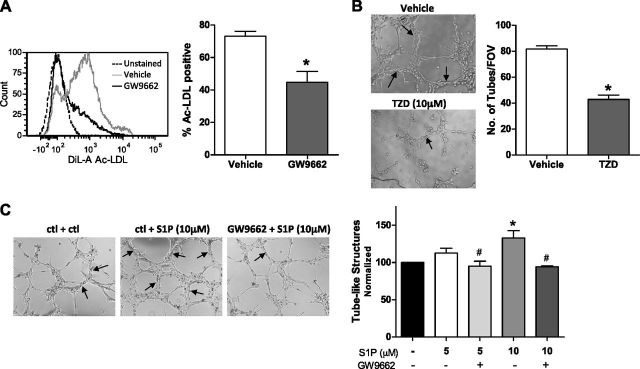

Inhibition of PPARγ in naEFCs reduces Ac-LDL uptake

Uptake of modified LDL is a feature of EPCs and ECs (50) and is facilitated by scavenger receptors (51). Having revealed a PPARγ transcriptional complex in naEFCs and ECs and a previous study showing that LPA enhances modified LDL uptake in murine macrophages, we next wanted to determine whether PPARγ participated in Ac-LDL uptake in ECs. To address this, we treated naEFCs with the irreversible PPARγ inhibitor GW9662 for 20 h prior to incubation with DiI-Ac-LDL and determined lipoprotein uptake by flow cytometric analysis. As shown in Fig. 7A, administration of GW9662 caused a significant reduction in DiI-Ac-LDL uptake when compared to control.

Figure 7.

PPARγ regulates DiI-Ac-LDL uptake and in vitro vessel-like structure formation. A) naEFCs were treated with the PPARγ antagonist, GW9662, at 5 μM for 20 h prior to incubation with DiI-Ac-LDL. Uptake was detected by flow cytometry. Representative histogram from n = 3. Data are expressed as means + sem (n = 3). *P < 0.05. B) Human ECs were treated with the PPARγ agonist, troglitazone (TZD), at 10 μM and vehicle (DMSO) for 20 h prior to Matrigel tube formation assay. Data are expressed as mean tubes per well [field of view (FOV)] + sem (n = 3). C) Human ECs were pretreated with GW9662 (1 µM) or vehicle for 30 min before being stimulated with S1P (5 or 10 µM) or vehicle. The number of tubes formed after 6 h was quantified, per well. Data are expressed as means + sem (n = 4). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle and #P < 0.05 vs. respective S1P alone.

Modulation of PPARγ alters tube formation in vitro and in vivo

With current conflicting reports regarding a role for PPARγ in tube formation [reviewed in Giaginis et al. (52)], we next investigated whether modulation of PPARγ activity altered the vasculogenic potential of ECs. First, we treated ECs with the synthetic PPARγ agonist, TZD (troglitazone) at 10 μM, and vehicle control (DMSO) and compared their ability to form tube-like structures in a 3-dimensional tube forming assay using Matrigel. As shown in Fig. 7B, ECs treated with 10 μM TZD (troglitazone) showed a significant reduction in tubular structures at 6 h when compared to control cells. With S1P being a known angiogenic factor (53), we next investigated whether the effect of S1P might be via the activation of PPARγ. To examine this, ECs were pretreated for 30 min with 1 µM GW9662 before being stimulated with S1P and seeded onto Matrigel. As depicted in Fig. 7C, there was a dose-dependent increase in tube formation with S1P treatment at 5 and 10 µM compared to vehicle, and importantly, this increase was significantly reduced with the addition of the PPARγ inhibitor GW9662.

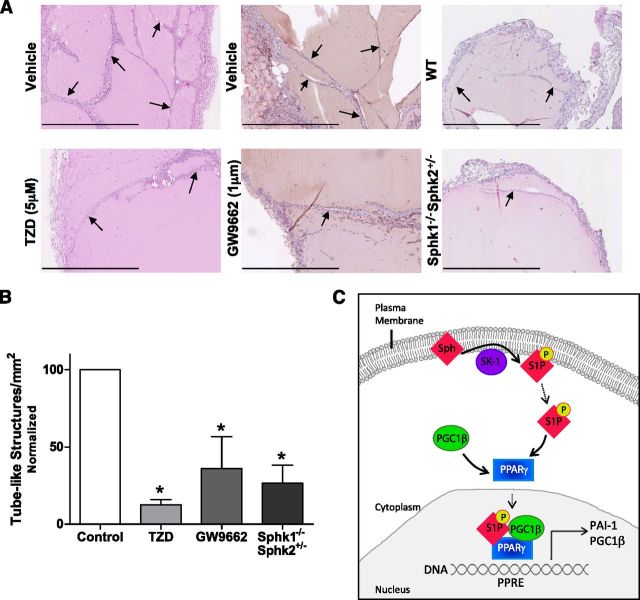

To determine whether modulation of PPARγ altered in vivo neovascularization, we implanted Matrigel plugs containing the specific PPARγ inhibitor, GW9662 (1 μM), TZD (troglitazone, 5 µM), or vehicle (DMSO) into the flank of C57Bl/6 mice. After 7 d, plugs were retrieved, and vessel-like structures were visualized with H&E. As shown in Fig. 8A, B, Matrigel plugs with TZD contained significantly fewer vessel-like structures compared to vehicle (control), similar to that seen in vitro. Moreover, Matrigel plugs containing GW9662 exhibited significantly less vessel-like structures when compared to vehicle (control)-treated plugs (Fig. 8A, B). Utilizing Sphk1−/−Sphk2+/− mice, which we found have very low plasma levels of S1P (64 ± 13 nM, compared to 1.05 ± 0.01 μM for WT mice), similar Matrigel plug experiments were undertaken to assess vessel-like structure formation in vivo. As shown in Fig. 8A, B, and similar to that seen with GW9662 inhibition of PPARγ, the plugs analyzed from Sphk1−/−Sphk2+/− mice contained significantly less vessel-like structures when compared to WT (control) mice.

Figure 8.

PPARγ regulates vessel-like structure formation in vivo. Matrigel plugs containing (A) 1 μM GW9662 and vehicle (DMSO), (B) 5 µM TZD and vehicle (DMSO), or from WT and Sphk1−/−Sphk2+/− mice were retrieved and H&E stained. The number of newly formed tube-like structures was counted per square millimeter. Arrows depict examples of quantified tube-like structures. Scale bars, 800 μm. Data are expressed as percentages of control per square millimeter + sem (n = 3–7). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle or WT. C) Schematic representation of the formation of the PPARγ transcriptional complex in ECs. Plasma membrane sphingosine is phosphorylated by SK-1, producing the bioactive lipid, S1P. Free S1P in the cytoplasm binds to the PPARγ complex, stimulating the recruitment of PGC1β and translocation of this transcriptional complex into the nucleus. The PPARγ:S1P:PGC1β complex binds to PPREs in the gene promoter and facilitates transcription of the PPARγ target genes: PGC1β and PAI-1.

DISCUSSION

The bioactive lipid S1P has been extensively investigated and implicated in a vast number of physiologic and pathologic cellular processes (54). These functions include the regulation of cell survival, proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis [reviewed in (55)]. One way S1P mediates these functions is via binding to and activating its cell surface GPCRs, which then stimulate downstream signaling pathways (1). Moreover, we and others have shown that S1P plays an important role in the regulation of EC function, independent of its cell surface GPCRs (6, 13), suggesting the presence of intracellular targets that mediate the effects of S1P in the vasculature. To this end, a number of intracellular targets for S1P have recently emerged, including 1) HDAC 1/2, whereby binding of S1P inhibits HDAC 1/2 enzymatic activity, resulting in enhanced gene transcription of p21 and c-fos (15); 2) TRAF2, which upon S1P binding, its U3 ubiquitin ligase activity is stimulated mediating lysine-63-linked polyubiquitination of receptor-interacting protein 1 (16); 3) PHB2, which regulates mitochondrial assembly and respiration following S1P binding (17); and most recently, 4) cIAP2, which upon S1P binding, has enhanced E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (18). By employing lipid affinity matrices, a radiolabeled S1P binding assay, luciferase reporter assays, and computational modeling, we have revealed PPARγ as another important intracellular target for S1P. Moreover, this is the first evidence that S1P binds any transcription factor and provides the first mode of S1P directly regulating gene expression. Our work also shows that activation of PPARγ by S1P stimulates recruitment of the PPARγ coactivator, PGC1β, leading to the formation of a transcriptional complex within ECs.

To characterize the PPARγ:S1P interaction, computational modeling was undertaken to map the predicted interaction of S1P with PPARγ through His323, His449, and Arg288. Luciferase assays confirmed that His323 on helix 12 of the PPARγ ligand binding pocket is critical in the binding of the phosphate head group of S1P. Moreover, the PPARγ1(H323A) mutant exhibited reduced binding and activation in response to S1P treatment. Of note, His323 and His449 are known to be involved in the binding of PPARγ to the TZD, rosiglitazone, whereas the binding of LPA involves Arg288, which is located on the opposite side of the binding pocket (39). In our hands, neither His449 nor Arg288 appeared to be critical for S1P binding and activation of PPARγ, suggesting that different PPARγ ligands bind via alternative residues. It is our contention that His323 is likely to be one of a number of thus far unidentified residues important for S1P-induced activation of PPARγ. Our data, in combination with Tsukahara et al. (39), reveal distinct interactions that mediate PPARγ ligand binding and thereby suggest a potential for alternative conformations and possibly differential gene regulation. In support, Dentelli et al. (56) and Trombetta et al. (57) showed that different PPARγ ligands could either augment or attenuate cell cycle progression via differential control of cyclin D1. Whether these ligand-induced differences in gene regulation are due to varied coactivator recruitment to the transcription factor complex is unknown. Herein, we showed that gene regulation is differential in response to different PPARγ ligands and in the 2 cell lines tested. ECs treated with S1P showed a cell-type-specific increase in PGC1β mRNA and protein because it was not modulated by S1P in U937 cells. PAI-1, a known PPARγ target gene (58), was also up-regulated in ECs in response to S1P, which has been observed previously in U373 glioblastoma cells but shown to occur in an S1P2-dependent manner (59). Interestingly, we were able to show that transcriptional activation of PPARγ by S1P was S1P1–3 independent, which may be due to the cell type (ECs) used in this study. PAI-1 protein, unlike gene expression, was not shown to increase with S1P treatment and could be attributed to secretion of PAI-1 from the ECs (60). Interestingly, our data also showed that LPA modulated PGC1β and PAI-1 gene expression in a manner similar to that of S1P in ECs. This may be explained by the structural similarities of S1P and LPA and their known overlapping roles within the vasculature [reviewed in Panetti (61)].

Gene expression analysis of the known PPARγ target genes, CD36 and aP2, with the different PPARγ ligands in ECs and U937 cells, validated the intricacies of PPARγ-mediated transcriptional regulation. CD36 is a scavenger receptor that, in a PPARγ-dependent manner, promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation (48) and adipocyte differentiation (62). In ECs, exposure to S1P reduced CD36 gene expression, which did not occur in the myeloid U937 cells. Interestingly, we did not observe an S1P-induced reduction in CD36 protein production in ECs. A role for CD36 in inhibiting angiogenesis via the induction of apoptosis has been documented in microvascular ECs (63). Interestingly, large vessel ECs, like HUVECs used in this study, have been shown previously to not express CD36 (64). This is consistent with our observation of low levels of the CD36 gene and protein. Like CD36, regulation of aP2 by PPARγ mediates adipocyte development (49), in addition to its role in lipid metabolism in macrophages (65). In this study, aP2 was not altered by any PPARγ agonist in ECs but was reduced in U937 cells in response to S1P and increased significantly in response to TZD. A recent study has implicated aP2 in regulating VEGF-induced airway angiogenesis (66), suggesting an additional role for aP2 in the endothelium that warrants further investigation. These data suggest that S1P stimulates a specific endothelial PPARγ-mediated gene transcription program, resulting in the loss of adipocyte/monocyte target gene expression through the lack of PPARγ availability. Whether activation of PPARγ by S1P regulates a specific transcriptional program in ECs will be best confirmed utilizing chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing.

PPARγ responses are tightly regulated through association with coactivators. PGC1β is 1 of 3 members of the PGC1 family of coactivators that has been described to mediate a wide array of metabolic functions (67). To date, there have been no studies that specifically investigate a role for PGC1β in the vasculature and thus far no reported vascular-specific animal models of PGC1β, or its family member, PGC1α. In this study, we have for the first time revealed PGC1β as a coactivator present within both naEFCs and ECs, with its gene expression shown to be significantly elevated in the immature progenitor population by microarray analysis (36) and qPCR. We have also shown that PGC1β is regulated by S1P and directly interacts with PPARγ in naEFCs and ECs, suggesting a role for PGC1β in mediating the endothelial effects of PPARγ. Interestingly, a recent study using HepG2 cells (a human hepatocellular carcinoma line) has shown that S1P increases mitochondrial biogenesis and stimulates the expression of PGC1α (68). This study also showed the effects of S1P on mitochondrial biogenesis (e.g., up-regulation of mitochondrial DNA replication) to be S1P2 dependent (68). Although limited literature is available on a vascular role for PGC1β, PGC1β overexpression in vascular smooth muscle cells inhibits proliferation and neointima hyperplasia, with a reduction in PGC1β detected in the arteries following balloon injury (69). PGC1β also increases VEGF expression in skeletal muscle cells, which results in increased migration of adjacent ECs, thus contributing to angiogenesis (70). A role for PGC1β and PPARs in macrophage activation has also been described through the modulation of macrophage lipid metabolism (71). Further investigation into the direct role of PGC1β on naEFC and EC function is warranted if this new transcriptional complex is to be targeted to modulate these cells.

A role for S1P in regulating EC biology has been widely described (53). Our laboratory has identified a role for SK-1 as a regulator of EPC differentiation, with SK-1 activity significantly elevated in murine bone marrow (BM)-derived EPCs, maintaining their progenitor cell phenotype (6). Interestingly, BM-derived EPCs isolated from SK-1 knockout mice have increased EC phenotype and function coupled with a reduction in progenitor cell markers, which was identified to occur independently of the S1P1–3 receptors (6). Furthermore, we have shown that overexpression of SK-1 in human ECs results in partial dedifferentiation toward a progenitor-like phenotype (11). In this current study, we have established that PPARγ is expressed at high levels in immature human naEFCs, which is similar to the expression profile of SK-1 observed to be elevated in murine EPCs (6), suggesting the presence of both the ligand (S1P) and receptor (PPARγ) in EPCs. Importantly, there is further evidence in the literature of reciprocal regulation of S1P and PPARγ with 1) mice deficient in cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator ABC transporter [suggested to traverse S1P across the plasma membrane (72)] exhibiting reduced PPARγ expression and function (73); 2) deficiency in S1P lyase resulting in elevated intracellular S1P levels and thereby an increase in PPARγ expression (74); and 3) S1P having been shown to regulate expression of PAI-1, a known PPARγ target gene in glioblastoma cells (59). Also of relevance to this study, the promoter of SK-1 contains a PPRE, and upon activation of PPARγ with TZDs, SK-1 mRNA, activity, and intracellular S1P levels have been shown to increase (75). We provide a conceptual advance with data showing that an increase in SK-1 activity increased PPARγ protein levels.

Roles for SK-1 and PPARγ in malignant diseases have been revealed in a number of studies. SK-1 expression is elevated in a number of human cancers, including breast (76), colon (77), and lung (78), when compared to normal tissue. Moreover, elevated SK-1 levels in patients with cancer can correlate with a poor prognosis (76). Like SK-1, PPARγ has been reported to be over-expressed in human cancers, including breast (79), colon (80), and prostate (81), although the activation state of PPARγ within these malignancies has not been identified. Interestingly, there is also conflicting evidence as to whether PPARγ activity levels modulate tumor progression (81) or suppression (82). Of note, PPARγ dysfunction in colon cancer was shown to occur through mutations of the protein itself as well as via down-regulation of its coactivator, PGC1β (80). In addition to direct effects within cancer cells, PPARγ and SK-1/S1P can also regulate nutrient delivery to the tumor. It has been well documented that for solid tumors to grow and metastasize, they require access to the blood supply (83). Both SK-1 and PPARγ are known to mediate blood vessel formation in normal and pathologic states. S1P stimulates tube formation in vitro (84) and promotes neovascularization in ischemia (85). S1P also promotes angiogenesis in breast cancer, contributing to tumor progression (86). To date, there are conflicting data describing PPARγ’s role in physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis, with some studies showing that PPARγ can promote this process (87), whereas others show that PPARγ has an inhibitory role (35). Previous studies have shown that the PPARγ agonists (88), TZDs, are antiangiogenic, and we have recapitulated those observations here. A proangiogenic role for PPARγ has been reported less frequently with some suggestion that it is partially mediated by EPCs, whereby PPARγ agonists increase EPC mobilization and function (29, 30). Of note, PPARγ−/− mice are embryonic lethal due to vascular defects in placental vasculature development, suggesting that proangiogenic PPARγ is essential to vascularize the placenta to support successful reproduction (18). Here, we have shown that S1P-induced in vitro tube formation is PPARγ dependent. With S1P well described as a key regulator of EC biology (53), this is the first intracellular target for S1P that has been shown to regulate EC function. Moreover, these data also support our observation that different ligands to PPARγ stimulate differential gene/protein expression, a phenomenon also seen by Dentelli et al. (56) and Trombetta et al. (57) in EPCs. Interestingly, we also show that TZD-induced activation inhibits tube formation in vitro and in vivo. A reduction in tube formation was also observed in vivo when the PPARγ inhibitor GW9662 was added. This raises the obvious question of why and how a PPARγ agonist (e.g., TZD) and antagonist (e.g., GW9662) can have the same inhibitory effect on vascular development. The answer may lie in the binding of the ligand to PPARγ. TZDs were discovered to have a very high binding affinity for PPARγ, much higher than that of endogenous PPARγ ligands (89), suggesting that a synthetic agonist may outcompete endogenous PPARγ agonists. Indeed, the study from McIntyre et al. (27) investigated S1P binding to PPARγ, but it was dismissed because it could not compete against the already bound TZD (rosiglitazone) from the PPARγ LBD. In addition, GW9662 is an irreversible inhibitor of PPARγ, preventing the binding and activation of endogenous ligands to PPARγ. These characteristics of TZDs and GW9662 lend themselves to dominant cellular effects, when compared to endogenous S1P. To further support this, we have shown significantly less tube formation in Matrigel plugs retrieved from mice with low levels of circulating S1P (23-fold; Sphk1−/−Sphk2−/−) compared to WT, suggesting that S1P is important in vascular development. Taken together, these studies suggest that neovascularization requires the activation of PPARγ by S1P. Ultimately, the execution of these in vivo Matrigel plug assays within mice with EC PPARγ deficiency would lead us to a greater understanding of the S1P and PPARγ axis in in vivo angiogenesis. In addition to modulating vessel formation, inhibition of PPARγ also reduced the capacity of naEFCs to take up Ac-LDL. This uptake occurs via a family of scavenger receptors (51) and assists in the depletion from the plasma when circulating lipoprotein levels are high; failure to do so contributes to the progression of atherosclerosis (90). Interestingly, our results contrast those by Chang et al. (91) who suggested that pretreatment of the murine macrophage cell line J774A.1 with GW9662 could not abolish LPA-induced oxidated LDL uptake. This supports our hypothesis of PPARγ-mediated cellular functions differing between ECs and myeloid cells. Taken together, these data suggest that binding of exogenous synthetic molecules may reduce the proangiogenic function of ECs and their progenitors impairing vessel formation through the displacement of endogenous ligands such as S1P.

This study has revealed a new lipid activator of PPARγ and begun to elucidate the specific residues that mediate this interaction. This new information may be exploited to design new PPARγ ligands for regulation of neovascularization. It is important to note that PPARγ1 is ubiquitously expressed, and thus, targeting specific PPARγ:ligand interactions will be key to regulating function. Alternatively, because coactivators are critical in controlling PPARγ function and specificity, and with PGC1β identified here as a coactivator in naEFCs and ECs, targeting the PPARγ1:PGC1β interaction may be more desirable to modulate PPARγ function and warrants further investigation.

Our results have uncovered PPARγ as the first transcription factor target for S1P. As depicted in Fig. 8C, we propose that PPARγ is binding to PGC1β within cells from the endothelial lineage after S1P binding and activation of PPARγ and that this complex regulates EC genes. This study has confirmed a role for PPARγ in ECs in vitro and in vivo, and thus, these new insights of how S1P interacts with PPARγ provide new opportunities for therapeutic targets to modulate endothelial function.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. David Dimasi for preparing the ECs, Samantha Escarbe for preparing the nonadherent endothelial forming cells, Lorena Davies for technical assistance with sphingosine 1-phosphate analysis, Dr. James Fells for his assistance with the in silico docking experiments, Dr. Melissa Pitman for assistance with interpretation of the in silico docking data, and the staff and consenting donors at Women’s and Children’s Hospital (North Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia) and Burnside Memorial Hospital (Burnside, Adelaide, SA, Australia) for the donation and collection of the umbilical cords and UCB. This work and C.S.B. were supported by a Heart Foundation Fellowship (CR 10A 4983). K.A.P. was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award and the Co-operative Research Centre for Biomarker Translation. S.M.P. was supported by a Senior Research Fellowship (1042589) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Fay Fuller Foundation. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- aP2

adipocyte fatty acid binding protein 2

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- BM

bone marrow

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CYCA

cyclophilin A

- DiI-Ac-LDL

1,19-dioctadecyl-3,3,39,39-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlo-rate-Ac-LDL

- EC

endothelial cell

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- EV

empty vector

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- LBB

lipid binding buffer

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- MNC

mononuclear cell

- MOE

molecular operating environment

- naEFC

nonadherent endothelial forming cell

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- PGC1

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1

- PHB2

prohibitin 2

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PPRE

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor response element

- PPRE-Luc

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor response element-luciferase

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- Renilla-Luc

Renilla luciferase

- RXR

retinoid-x receptor

- S1P

sphingosine 1-phosphate

- SK

sphingosine kinase

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TLC

thin-layer chromatography

- TRAF2

TNF receptor-associated factor-2

- TZD

thiazolidinedione

- UCB

umbilical cord blood

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pitson S. M. (2011) Regulation of sphingosine kinase and sphingolipid signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. , 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yatomi Y., Igarashi Y., Yang L., Hisano N., Qi R., Asazuma N., Satoh K., Ozaki Y., Kume S. (1997) Sphingosine 1-phosphate, a bioactive sphingolipid abundantly stored in platelets, is a normal constituent of human plasma and serum. J. Biochem. , 969–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.García-Pacios M., Collado M. I., Busto J. V., Sot J., Alonso A., Arrondo J. L., Goñi F. M. (2009) Sphingosine-1-phosphate as an amphipathic metabolite: its properties in aqueous and membrane environments. Biophys. J. , 1398–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hla T., Venkataraman K., Michaud J. (2008) The vascular S1P gradient-cellular sources and biological significance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta , 477–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin C. I., Chen C. N., Lin P. W., Lee H. (2007) Sphingosine 1-phosphate regulates inflammation-related genes in human endothelial cells through S1P1 and S1P3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. , 895–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonder C. S., Sun W. Y., Matthews T., Cassano C., Li X., Ramshaw H. S., Pitson S. M., Lopez A. F., Coates P. T., Proia R. L., Vadas M. A., Gamble J. R. (2009) Sphingosine kinase regulates the rate of endothelial progenitor cell differentiation. Blood , 2108–2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gamble J. R., Sun W. Y., Li X., Hahn C. N., Pitson S. M., Vadas M. A., Bonder C. S. (2009) Sphingosine kinase-1 associates with integrin αVβ3 to mediate endothelial cell survival. Am. J. Pathol. , 2217–2225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwalm S., Döll F., Römer I., Bubnova S., Pfeilschifter J., Huwiler A. (2008) Sphingosine kinase-1 is a hypoxia-regulated gene that stimulates migration of human endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. , 1020–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan G., Chen S., You B., Sun J. (2008) Activation of sphingosine kinase-1 mediates induction of endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Cardiovasc. Res. , 308–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strub G. M., Maceyka M., Hait N. C., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2010) Extracellular and intracellular actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. , 141–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett J. M., Parham K. A., Pippal J. B., Cockshell M. P., Moretti P. A., Brice S. L., Pitson S. M., Bonder C. S. (2011) Over-expression of sphingosine kinase-1 enhances a progenitor phenotype in human endothelial cells. Microcirculation , 583–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun W. Y., Pitson S. M., Bonder C. S. (2010) Tumor necrosis factor-induced neutrophil adhesion occurs via sphingosine kinase-1-dependent activation of endothelial α5β1 integrin. Am. J. Pathol. , 436–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun W. Y., Abeynaike L. D., Escarbe S., Smith C. D., Pitson S. M., Hickey M. J., Bonder C. S. (2012) Rapid histamine-induced neutrophil recruitment is sphingosine kinase-1 dependent. Am. J. Pathol. , 1740–1750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Limaye V., Li X., Hahn C., Xia P., Berndt M. C., Vadas M. A., Gamble J. R. (2005) Sphingosine kinase-1 enhances endothelial cell survival through a PECAM-1-dependent activation of PI-3K/Akt and regulation of Bcl-2 family members. Blood , 3169–3177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hait N. C., Allegood J., Maceyka M., Strub G. M., Harikumar K. B., Singh S. K., Luo C., Marmorstein R., Kordula T., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2009) Regulation of histone acetylation in the nucleus by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science , 1254–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvarez S. E., Harikumar K. B., Hait N. C., Allegood J., Strub G. M., Kim E. Y., Maceyka M., Jiang H., Luo C., Kordula T., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2010) Sphingosine-1-phosphate is a missing cofactor for the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF2. Nature , 1084–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strub G. M., Paillard M., Liang J., Gomez L., Allegood J. C., Hait N. C., Maceyka M., Price M. M., Chen Q., Simpson D. C., Kordula T., Milstien S., Lesnefsky E. J., Spiegel S. (2011) Sphingosine-1-phosphate produced by sphingosine kinase 2 in mitochondria interacts with prohibitin 2 to regulate complex IV assembly and respiration. FASEB J. , 600–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harikumar K. B., Yester J. W., Surace M. J., Oyeniran C., Price M. M., Huang W. C., Hait N. C., Allegood J. C., Yamada A., Kong X., Lazear H. M., Bhardwaj R., Takabe K., Diamond M. S., Luo C., Milstien S., Spiegel S., Kordula T. (2014) K63-linked polyubiquitination of transcription factor IRF1 is essential for IL-1-induced production of chemokines CXCL10 and CCL5. Nat. Immunol. , 231–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tontonoz P., Spiegelman B. M. (2008) Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu. Rev. Biochem. , 289–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalik L., Auwerx J., Berger J. P., Chatterjee V. K., Glass C. K., Gonzalez F. J., Grimaldi P. A., Kadowaki T., Lazar M. A., O’Rahilly S., Palmer C. N., Plutzky J., Reddy J. K., Spiegelman B. M., Staels B., Wahli W. (2006) International Union of Pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. , 726–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee R., Jow L., Croston G. E., Paterniti J. R. Jr (1997) Identification, characterization, and tissue distribution of human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) isoforms PPARgamma2 versus PPARgamma1 and activation with retinoid X receptor agonists and antagonists. J. Biol. Chem. , 8071–8076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werman A., Hollenberg A., Solanes G., Bjorbaek C., Vidal-Puig A. J., Flier J. S. (1997) Ligand-independent activation domain in the N terminus of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARgamma). Differential activity of PPARgamma1 and -2 isoforms and influence of insulin. J. Biol. Chem. , 20230–20235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asami-Miyagishi R., Iseki S., Usui M., Uchida K., Kubo H., Morita I. (2004) Expression and function of PPARgamma in rat placental development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. , 497–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medina-Gomez G., Virtue S., Lelliott C., Boiani R., Campbell M., Christodoulides C., Perrin C., Jimenez-Linan M., Blount M., Dixon J., Zahn D., Thresher R. R., Aparicio S., Carlton M., Colledge W. H., Kettunen M. I., Seppänen-Laakso T., Sethi J. K., O’Rahilly S., Brindle K., Cinti S., Oresic M., Burcelin R., Vidal-Puig A. (2005) The link between nutritional status and insulin sensitivity is dependent on the adipocyte-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ2 isoform. Diabetes , 1706–1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asano T., Wakisaka M., Yoshinari M., Iino K., Sonoki K., Iwase M., Fujishima M. (2000) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ1 (PPARgamma1) expresses in rat mesangial cells and PPARgamma agonists modulate its differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta , 148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norazmi M. N., Mohamed R., Nurul A. A., Yaacob N. S. (2012) The modulation of PPARγ1 and PPARγ2 mRNA expression by ciglitazone in CD3/CD28-activated naïve and memory CD4+ T cells. Clin. Dev. Immunol. , 849195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McIntyre T. M., Pontsler A. V., Silva A. R., St Hilaire A., Xu Y., Hinshaw J. C., Zimmerman G. A., Hama K., Aoki J., Arai H., Prestwich G. D. (2003) Identification of an intracellular receptor for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA): LPA is a transcellular PPARgamma agonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA , 131–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehmann J. M., Moore L. B., Smith-Oliver T. A., Wilkison W. O., Willson T. M., Kliewer S. A. (1995) An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR γ). J. Biol. Chem. , 12953–12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pistrosch F., Herbrig K., Oelschlaegel U., Richter S., Passauer J., Fischer S., Gross P. (2005) PPARgamma-agonist rosiglitazone increases number and migratory activity of cultured endothelial progenitor cells. Atherosclerosis , 163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner C., Kamani C. H., Gensch C., Böhm M., Laufs U. (2007) The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist pioglitazone increases number and function of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with coronary artery disease and normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes , 2609–2615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C. H., Ciliberti N., Li S. H., Szmitko P. E., Weisel R. D., Fedak P. W., Al-Omran M., Cherng W. J., Li R. K., Stanford W. L., Verma S. (2004) Rosiglitazone facilitates angiogenic progenitor cell differentiation toward endothelial lineage: a new paradigm in glitazone pleiotropy. Circulation , 1392–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cicha I., Urschel K., Daniel W. G., Garlichs C. D. (2011) Telmisartan prevents VCAM-1 induction and monocytic cell adhesion to endothelium exposed to non-uniform shear stress and TNF-α. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. , 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung Y., Song S., Choi C. (2008) Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ agonists suppress TNFalpha-induced ICAM-1 expression by endothelial cells in a manner potentially dependent on inhibition of reactive oxygen species. Immunol. Lett. , 63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawabe-Yako R., Masaaki I., Masuo O., Asahara T., Itakura T. (2011) Cilostazol activates function of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell for re-endothelialization in a carotid balloon injury model. PLoS One , e24646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xin X., Yang S., Kowalski J., Gerritsen M. E. (1999) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands are potent inhibitors of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. , 9116–9121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appleby S. L., Cockshell M. P., Pippal J. B., Thompson E. J., Barrett J. M., Tooley K., Sen S., Sun W. Y., Grose R., Nicholson I., Levina V., Cooke I., Talbo G., Lopez A. F., Bonder C. S. (2012) Characterization of a distinct population of circulating human non-adherent endothelial forming cells and their recruitment via intercellular adhesion molecule-3. PLoS One , e46996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Litwin M., Clark K., Noack L., Furze J., Berndt M., Albelda S., Vadas M., Gamble J. (1997) Novel cytokine-independent induction of endothelial adhesion molecules regulated by platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule (CD31). J. Cell Biol. , 219–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurnell M., Wentworth J. M., Agostini M., Adams M., Collingwood T. N., Provenzano C., Browne P. O., Rajanayagam O., Burris T. P., Schwabe J. W., Lazar M. A., Chatterjee V. K. (2000) A dominant-negative peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARgamma) mutant is a constitutive repressor and inhibits PPARgamma-mediated adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. , 5754–5759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsukahara T., Tsukahara R., Yasuda S., Makarova N., Valentine W. J., Allison P., Yuan H., Baker D. L., Li Z., Bittman R., Parrill A., Tigyi G. (2006) Different residues mediate recognition of 1-O-oleyllysophosphatidic acid and rosiglitazone in the ligand binding domain of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. J. Biol. Chem. , 3398–3407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pitson S. M., D’andrea R. J., Vandeleur L., Moretti P. A., Xia P., Gamble J. R., Vadas M. A., Wattenberg B. W. (2000) Human sphingosine kinase: purification, molecular cloning and characterization of the native and recombinant enzymes. Biochem. J. , 429–441 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pitson S. M., Moretti P. A., Zebol J. R., Zareie R., Derian C. K., Darrow A. L., Qi J., D’Andrea R. J., Bagley C. J., Vadas M. A., Wattenberg B. W. (2002) The nucleotide-binding site of human sphingosine kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. , 49545–49553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trott O., Olson A. J. (2010) AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. , 455–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizugishi K., Yamashita T., Olivera A., Miller G. F., Spiegel S., Proia R. L. (2005) Essential role for sphingosine kinases in neural and vascular development. Mol. Cell. Biol. , 11113–11121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leclercq T. M., Moretti P. A., Vadas M. A., Pitson S. M. (2008) Eukaryotic elongation factor 1A interacts with sphingosine kinase and directly enhances its catalytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. , 9606–9614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee M. J., Van Brocklyn J. R., Thangada S., Liu C. H., Hand A. R., Menzeleev R., Spiegel S., Hla T. (1998) Sphingosine-1-phosphate as a ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor EDG-1. Science , 1552–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Brocklyn J. R., Jackson C. A., Pearl D. K., Kotur M. S., Snyder P. J., Prior T. W. (2005) Sphingosine kinase-1 expression correlates with poor survival of patients with glioblastoma multiforme: roles of sphingosine kinase isoforms in growth of glioblastoma cell lines. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. , 695–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nolte R. T., Wisely G. B., Westin S., Cobb J. E., Lambert M. H., Kurokawa R., Rosenfeld M. G., Willson T. M., Glass C. K., Milburn M. V. (1998) Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Nature , 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tontonoz P., Nagy L., Alvarez J. G., Thomazy V. A., Evans R. M. (1998) PPARgamma promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell , 241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rival Y., Stennevin A., Puech L., Rouquette A., Cathala C., Lestienne F., Dupont-Passelaigue E., Patoiseau J. F., Wurch T., Junquéro D. (2004) Human adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein (aP2) gene promoter-driven reporter assay discriminates nonlipogenic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. , 467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Voyta J. C., Via D. P., Butterfield C. E., Zetter B. R. (1984) Identification and isolation of endothelial cells based on their increased uptake of acetylated-low density lipoprotein. J. Cell Biol. , 2034–2040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daugherty A., Cornicelli J. A., Welch K., Sendobry S. M., Rateri D. L. (1997) Scavenger receptors are present on rabbit aortic endothelial cells in vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. , 2369–2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giaginis C., Margeli A., Theocharis S. (2007) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligands as investigational modulators of angiogenesis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs , 1561–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Limaye V. (2008) The role of sphingosine kinase and sphingosine-1-phosphate in the regulation of endothelial cell biology. Endothelium , 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hla T. (2004) Physiological and pathological actions of sphingosine 1-phosphate. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. , 513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hannun Y. A., Obeid L. M. (2008) Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. , 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dentelli P., Trombetta A., Togliatto G., Zeoli A., Rosso A., Uberti B., Orso F., Taverna D., Pegoraro L., Brizzi M. F. (2009) Formation of STAT5/PPARgamma transcriptional complex modulates angiogenic cell bioavailability in diabetes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. , 114–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trombetta A., Togliatto G., Rosso A., Dentelli P., Olgasi C., Cotogni P., Brizzi M. F. (2013) Increase of palmitic acid concentration impairs endothelial progenitor cell and bone marrow-derived progenitor cell bioavailability: role of the STAT5/PPARγ transcriptional complex. Diabetes , 1245–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marx N., Bourcier T., Sukhova G. K., Libby P., Plutzky J. (1999) PPARgamma activation in human endothelial cells increases plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 expression: PPARgamma as a potential mediator in vascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. , 546–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bryan L., Paugh B. S., Kapitonov D., Wilczynska K. M., Alvarez S. M., Singh S. K., Milstien S., Spiegel S., Kordula T. (2008) Sphingosine-1-phosphate and interleukin-1 independently regulate plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor expression in glioblastoma cells: implications for invasiveness. Mol. Cancer Res. , 1469–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Handt S., Jerome W. G., Tietze L., Hantgan R. R. (1996) Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 secretion of endothelial cells increases fibrinolytic resistance of an in vitro fibrin clot: evidence for a key role of endothelial cells in thrombolytic resistance. Blood , 4204–4213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Panetti T. S. (2002) Differential effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate and lysophosphatidic acid on endothelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta , 190–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]