Abstract

Hypoxia can cause stress and structural changes to the epithelial cytoskeleton. The intermediate filament (IF) network is known to reorganize in response to stress. We examined whether rats exposed to hypoxia had altered keratin IF expression in their alveolar epithelial type II (ATII) cells. There was a significant decrease in keratin protein levels in hypoxic ATII cells compared with those in ATII cells isolated from normoxic rats. To define the mechanisms regulating this process we studied changes to the keratin IF network in A549 cells (an alveolar epithelial cell line) exposed to 1.5% oxygen. We observed a time-dependent disassembly-degradation of keratin 8 and 18 proteins, which was associated with an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS). Hypoxia-treated A549 cells deficient in mitochondrial DNA or A549 cells treated with a small interfering RNA against the Rieske iron-sulfur protein of mitochondrial complex III did not have increased levels of ROS nor was the keratin IF network disassembled and degraded. The superoxide dismutase (SOD)/catalase mimetic (EUK-134) prevented the hypoxia-mediated keratin IF degradation as did the overexpression of SOD1 but not of SOD2. Accordingly, we provide evidence that hypoxia promotes the disassembly and degradation of the keratin IF network via mitochondrial complex III-generated reactive oxygen species.—Na, N., Chandel, N. S., Litvan, J., Ridge, K. M. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species are required for hypoxia-induced degradation of keratin intermediate filaments.

Keywords: alveolar epithelial cells, superoxide dismutase, lung

keratin intermediate filaments (ifs) are assembled as obligate heteropolymers of type I (K9–K20) and type II (K1–K8) IF proteins (1⤻, 2)⤻. Simple epithelia, such as those found in lung, liver, intestine, and pancreas, express keratins 8 and 18 (K8 and K18), often in association with variable amounts of secondary keratins, including keratins 7, 19, and 20 (3⤻4⤻5⤻6⤻7)⤻. The prototype structure of all IF proteins, including keratins, consists of a structurally conserved central coiled-coil α-helix, termed the “rod,” that is flanked by non-α-helical N-terminal “head” and C-terminal “tail” domains (1)⤻.

Keratin IFs are the major cytoskeletal component of epithelial cells and play a crucial role in maintaining their structural integrity. Despite the classic concept that IFs are static structures, keratins are highly dynamic and reorganize in response to various external environmental stresses, such as shear stress (6⤻, 7)⤻, and during various cellular events, such as mitosis and apoptosis (8⤻9⤻10)⤻. Accumulating data suggest that reorganization of keratin IFs may facilitate the transmission of signals from the cell surface to all regions of the cytoplasm (1)⤻. Excluding the role that keratin IFs play in helping cells cope with stress, the function of keratin IFs remains poorly understood (11⤻, 12)⤻. However, it is hypothesized that IF assembly and disassembly may be key regulatory mechanisms by which keratin IF may exert various and diverse cellular functions.

Mitochondria-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anions (O2−) and H2O2, have generally been regarded as toxic by-products of cellular respiration. More recent studies indicate that low levels of mitochondrial ROS function as signaling messengers responsible for triggering functional responses to hypoxia in diverse cell types (13⤻14⤻15)⤻. We examined whether hypoxia partially inhibits mitochondrial electron transport, resulting in redox changes in the electron carriers that increase the generation of ROS (16⤻, 17)⤻. These oxidants then enter the cytosol and can function as second messengers, which regulate the assembly state of keratin IF in alveolar epithelial cells.

In the present study we tested the hypothesis that alveolar epithelial cells respond to a change in the partial pressure of oxygen via the mitochondria, which stimulates an increase in the release of ROS signals to the cytosol. We propose that the resulting increase in oxidant signaling is biologically significant, in that it leads to the disassembly and degradation of a key structural element, the keratin intermediate filament network. In this study we examined the generation of mitochondrial ROS in response to hypoxia and the functional significance of this signaling in terms of its ability to disassemble and degrade keratin IF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oxygen conditions

Alveolar epithelial cells were exposed to 1.5% O2, 93.5% N2, and 5% CO2 in a humidified variable aerobic workstation (InVivo O2; BioTrace International, Muncie, IN, USA). The InVivo O2 contains an oxygen sensor that continuously monitors the chamber oxygen tension. In all experiments, cells were plated at 40–70% confluence. Before experimentation, cell culture medium was preequilibrated overnight to the experimental oxygen level. Animals were placed in a Ruskinn InVivo2 400 hypoxia chamber with a 12/12-h light-dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. Oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the chamber were continuously monitored while the chamber temperature was maintained between 18 and 22°C, as described previously (18)⤻.

Isolation and culture of alveolar epithelial cells

Rat ATII cells were isolated from pathogen-free male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–225 g), as described previously. In brief, the lungs were perfused via the pulmonary artery, lavaged, and digested with elastase (30 U/ml; Worthington Biochemical Corp., Freehold, NJ, USA). A549 cells were purified by differential adherence to IgG-pretreated dishes, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion (>95%). Cells were suspended in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum with 2 mM l-glutamine, 40 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and placed in culture for 2 d before the start of all experimental conditions. Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. Human A549 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. To generate ρ0-A549 cells, wild-type A549 cells were incubated in medium containing ethidium bromide (50 ng/ml), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), and uridine (50 μg/ ml) for 4–6 wk (19)⤻. The ρ0 status of cells was confirmed by the absence of cytochrome oxidase subunit II by PCR and the failure to grow in the absence of uridine in the medium. A549 cells (∼50% confluent) were infected with 10 μl [106/μl plaque-forming units (pfu)] of superoxide dismutase (SOD)-1 (Ad5CMVCuZnSOD) and SOD2 (Ad5CMVMnSOD).

Immunofluorescence

Cells grown on glass slides were rinsed 3 times in PBS and fixed in either methanol (−20°C) for 4 min or 3.5% formaldehyde at room temperature for 7 min. After formaldehyde fixation, cells were permeabilized with 0.05% Tween 20 for 5 min. Cells were then washed 3 times with PBS and processed for indirect immunofluorescence as described previously (20⤻, 21)⤻. After staining, the glass slides or Silastic membranes were washed in PBS and mounted in Gelvatol containing 100 mg/ml 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (Dabco; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) (20)⤻. Images of fixed, stained preparations were taken with a Zeiss LSM 510 microscope (Carl Zeiss, New York, NY, USA) (20)⤻.

Protein isolation and immunoblotting

Total cell lysates were obtained from cells after solubilization in Laemmli sample buffer. Keratin-enriched cytoskeletal preparations were made according to procedures published previously (19⤻, 22)⤻. In brief, the resulting fraction was prepared by solubilizing cells for 10 min at 4°C with buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, and a protease inhibitor mix (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μM leupeptin, 10 μM pepstatin, and 25 μg/ml aprotinin) in PBS (pH 7.4), followed by centrifugation (16,000 g, 10 min). The supernatant was collected as the soluble fraction. The pellet was homogenized in 1 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 140 mM NaCl, 1.5 M KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, and the protease inhibitor mix. After 30 min (4°C) the homogenate was pelleted (16,000 g; 10 min), and the pellet (insoluble fraction) was rehomogenized with 5 mM EDTA in PBS, pH 7.4, pelleted (Triton X-100 insoluble fraction), dissolved in Laemmli sample buffer containing 1% β-mercaptoethanol, sonicated, and boiled for 5 min (23)⤻. The samples were separated on 7.5 or 10% polyacrylamide gels according to the method of Laemmli (23)⤻. Equal amounts of proteins were loaded on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and blotted with the primary antibodies as follows: anti-K8/18 monoclonal antibody (1:500 in TBS; Research Diagnostics, Inc., Flanders, NJ, USA); anti-hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α antibody (1:500 in TBS; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); SOD1 antibody (1:500 in TBS; BD Biosciences), SOD2 antibody (1:1000 in TBS; BD Biosciences), catalase antibody (1:10,000 in TBS; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA), and 1:5000 of Myc antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Proteins were detected using antibodies to the Rieske iron-sulfur protein (RISP) (1:500 in TBS; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). As a loading control, an antibody to α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) was used at 1:2000. Membranes were washed 3 times with TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 30 min, incubated with secondary antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase (in dilutions recommended by supplier), and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). For immunoprecipitation studies, cells were solubilized in modified RIPA buffer. After pelleting (16,000 g; 15 min), keratin was immunoprecipitated from the supernatant using an anti-K8 antibody coupled to protein A/G Sepharose. The beads were washed once with RIPA buffer and twice with PBS (3 mM EDTA). Proteins were solubilized in 3× Laemmli sample buffer and then immunoblotted as described above with the relevant antibodies.

RNA interference

We obtained annealed, 21-bp small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes from Dharmacon RNA Technologies (Lafayette, CO, USA). HEK-293 cells plated onto 60-mm cell culture dishes were transfected with double-stranded RNA targeting the Rieske iron-sulfur gene sequence 1 (5′-AAUGCCGUCACCCAGUUCGUU-3′) or 2 (5′-AAGGUGCCUGACUUCUCUGAA-3′) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Control experiments were performed using the double-stranded RNA targeting the Renilla luciferase gene sequence (5′-AAACATGCAGAAAATGCTGTT-3′). The cells were examined 60 h after transfection. Small hairpin RNA (shRNA) for the Rieske iron-sulfur gene sequence 1 was cloned into the retroviral pSIREN vector (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The Drosophila HIF (dHIF) sequence (5′-CCUACAUCCCGAUCGAUGAUG-3′) was cloned as a control sequence. The retrovirus was packaged using the PT67 packaging cell line (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). The retrovirus encodes the puromycin gene as a resistance marker to make stable clones.

Miscellaneous

ATP levels were measured by the luciferin/luciferase method using an ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit HS II (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was measured using a commercially available assay (Cytotoxicity Detection Kit; Roche Pharmaceuticals, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Protein content was determined according to Bradford (24)⤻ using a commercial dye reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA, USA) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using a Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus kit (Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

Determination of ROS

Generation of ROS was assessed using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Molecular Probes), as described previously (16)⤻. ROS in cells cause oxidation of DCFH (25)⤻, yielding the fluorescent product 2′,7′-DCF. Cells were incubated with DCFH-DA (10 μM) under various experimental conditions. Thereafter, the medium was removed, and the cells were lysed by addition of lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 1 min to remove the cell debris. The supernatant was collected, and fluorescence was measured using a spectrofluorometer (excitation, 500 nm; emission, 530 nm). Data were normalized to values obtained from normoxic, untreated controls.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons were performed with the unpaired Student’s t test. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test was used to analyze the data. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

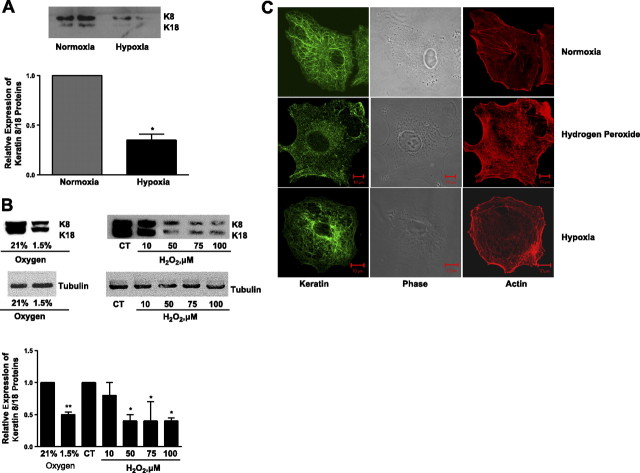

We sought to determine whether hypoxia had an effect on the keratin IF network in alveolar epithelial cells. We established an in vivo model of alveolar hypoxia by exposing rats to 8% oxygen for 24 h. ATII cells were then isolated from normoxic and hypoxic rats, and a keratin-enriched cytoskeleton extract was prepared. Keratin 8 and 18 protein levels were significantly decreased in cells isolated from hypoxic rats compared with those from normoxic rats (Fig. 1A⤻). We then established an in vitro model of hypoxia; A549 cells were exposed to either 21 or 1.5% oxygen for 24 h. K8 and K18 protein abundance was significantly reduced in A549 cells exposed to hypoxia (Fig. 1B⤻). There was no change in keratin IF protein in A549 cells exposed to 1.5% O2 for 1 h compared with that in normoxic controls (data not shown). Several reports have suggested that in oxygen-sensing cells, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) serves as an intracellular messenger because of its relative stability and membrane permeability (25⤻, 26)⤻. We examined whether A549 cells treated with t-butyl-H2O2 (t-H2O2), a more stable analog of H2O2, would mimic the hypoxia-induced reorganization of keratin IF. Keratin 8 and 18 protein abundance was decreased in A549 cells exposed to t-H2O2 (50–100 μM; 120 min) (Fig. 1A⤻). The effects of hypoxia and t-H2O2 were also assessed by indirect immunofluorescence. The keratin IF network in control, unstressed cells was organized into arrays of relatively straight, thin keratin fibrils (Fig. 1C⤻, top panel). In A549 cells exposed to either 1.5% oxygen for 24 h or to 100 μM t-H2O2 for 120 min, the keratin IF network was disorganized and disassembled, as shown by numerous keratin particles and squiggles (Fig. 1C⤻, middle and bottom panels). These latter forms of IF are known to be alternate forms of IF that are typical of disassembled IF networks or involved in the assembly of IF (27)⤻. The effects of hypoxia and H2O2 seem to be specific to the keratin IF component of the cytoskeleton, as the actin microfilaments (Fig. 1B⤻) and tubulin (Fig. 1A⤻) are not disassembled or degraded.

Figure 1.

Effects of hypoxia on keratin 8/18 protein levels. A) Keratin-enriched fractions were prepared from ATII cells that were isolated from the lungs of rats exposed to 21% (normoxia) or 8% O2 (hypoxia) for 24 h and compared with those from normoxic control lungs. A representative Western blot for keratin 8 and 18 proteins (25 μg protein/lane) is shown; each lane represents cell isolation from a single animal. Bars represent means ± sd of 3 to 5 determinations performed independently (separate ATII cell isolations) and in duplicate. *P < 0.05. B) A549 cells were exposed to 21 or 1.5% O2 for 24 h or to t-H2O2 (10–100 μM, 120 min). Equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with anti-K8/K18 and anti-tubulin. A representative autoradiogram is shown. CT, control. Bars represent means ± sd of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05. C) Effects of hypoxia and t-H2O2 were assessed by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-K8/K18 (green channel). Keratin IF network in control, unstressed cells was organized into arrays of relatively straight, thin keratin fibrils (top panel). In A549 cells exposed to either 100 μM t-H2O2 for 120 min (middle panel) or 1.5% oxygen for 24 h (bottom panel), keratin IF network was disorganized and disassembled, as shown by numerous keratin particles and squiggles. Effects of hypoxia and H2O2 appear to be specific to the keratin IF component of the cytoskeleton, as actin microfilaments (red channel) are not disassembled or degraded.

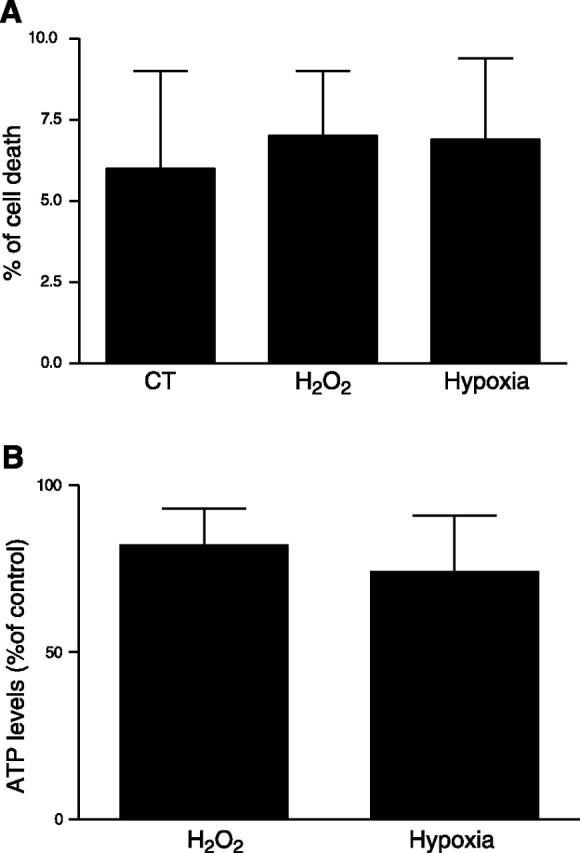

Severe hypoxia (0.5% O2) can cause a decrease in mitochondrial ATP production (28)⤻. It is possible that decreased levels of ATP could trigger hypoxia-related cellular responses such as reorganization of the cytoskeleton or cell death (26⤻, 29)⤻. Therefore, the cellular ATP levels and LDH activity (an index of cell death) were measured in A549 cells exposed to either 21% O2, 1.5% O2, or H2O2. As shown in Fig. 2A, B⤻, there was no change in LDH activity or in ATP levels. The cells were responsive to hypoxia, as HIF-1α protein was stabilized in A549 cells exposed to 1.5% O2 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of hypoxia on cell viability and ATP concentration. LDH release (expressed as a percentage of cell death; A) and ATP levels [expressed as a percentage of control (CT); B] were determined in A549 cells exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h. Bars represent means ± sd of 3 independent experiments.

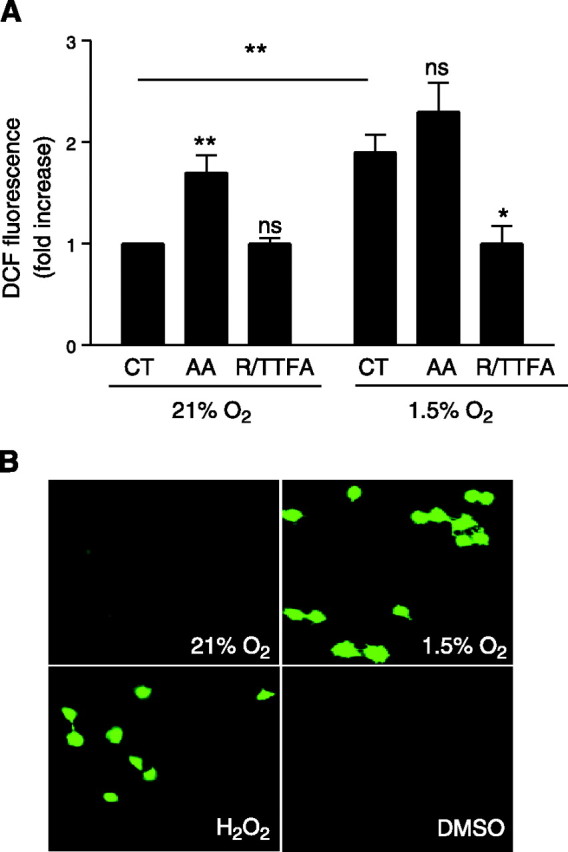

Hypoxia stimulates ROS production in alveolar epithelial cells

Production of ROS has been proposed as a possible sensor mechanism by which cells could detect the decrease in oxygen concentration (30⤻31⤻32)⤻. We determined whether ROS are generated in A549 cells exposed to hypoxia. Thus, A549 cells were preloaded with 2′,7′-DCFH-DA (10 μM) and exposed to 21 and 1.5% O2 for 60 min. Production of ROS results in the oxidation of DCFH and yields the fluorescent product DCF. As shown in Fig. 3⤻, DCF fluorescence was increased in cells incubated for 1 h at 1.5% O2. To determine the source of ROS during hypoxia, cells loaded with DCFH were pretreated with mitochondrial inhibitors before exposure to 1.5% O2. The mitochondrial electron transport inhibitors rotenone (1 μg/ml) and thenoyltrifluoracetone (TTFA) (10 μM) were added to block the electron supply to ubiquinol, thereby limiting the formation of ubisemiquinone (25)⤻ and preventing the increase in DCF fluorescence during hypoxia. A549 cells were also loaded with DCFH and pretreated with anti-mycin A (AA), which inhibits the oxidation of cytochrome b566, thereby increasing the lifetime of ubisemiquinone (25)⤻; this produced an increase in DCFH oxidation, detected by fluorescence measurements, in both normoxic and hypoxic A549 cells. Production of ROS was also assessed by DCF epifluorescence microscopy. Figure 3B⤻ depicts a representative photomicrograph of A549 cells loaded with DCFH and exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h. Hypoxia caused a significant increase in ROS production compared with that in normoxic control cells. Collectively, these results suggest that mitochondrial ROS production is increased in A549 cells exposed to hypoxia compared with normoxic cells.

Figure 3.

ROS production in A549 cells during hypoxia. A) A549 cells were preincubated in the presence or absence of AA (1 μg/ml) or rotenone (1 μg/ml) plus TTFA (10 μM) (R/TTFA) and then incubated under 21 or 1.5% O2 in the presence of DCFH-DA (10 μM) for 60 min. Data are means ± sd of 4 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. B) A549 cells were incubated under 21 or 1.5% O2 or with 50 μM H2O2 in the presence of DCFH-DA (10 μM) for 60 min. Representative photomicrographs of DCFH fluorescence are shown.

ROS are required for hypoxia-induced decrease in keratin expression

Mitochondria-derived ROS are initially produced as superoxide (16)⤻, which is subsequently converted to H2O2 by SOD. For the cell to eliminate superoxide anions and other radicals, two sequential reactions are required. Superoxide anions need to be converted to H2O2 through one of the cellular SODs in the mitochondria and catalase in the cytosol. Because both superoxide anion and H2O2 may be required for hypoxia-mediated reorganization of keratin IF, we chose to use the combined SOD/catalase mimetic EUK-134. This compound has been shown to correct the mev1 genetic defect caused by a deficiency in antioxidant enzymes in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (33)⤻. Rat ATII cells were treated with EUK-134 (20 μM), as described previously (34)⤻, and were simultaneously exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 4A⤻, EUK-134 prevented hypoxia-induced disassembly of keratin IF in rat ATII cells as shown by Western blot. In addition, the keratin IF network was protected from hypoxia in cells treated with EUK-134 as assessed by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 4B⤻). Rat ATII cells were treated with EUK-134 as described above and simultaneously were exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h. One hour before the end of hypoxic exposure the cells were loaded with 2′,7′-DCFH-DA (10 μM). As shown in Fig. 4C⤻, DCF fluorescence was increased in cells exposed to 1.5% O2 but not in the hypoxic cells treated with EUK-134.

Figure 4.

Rat ATII cells were incubated under 21% O2 in the presence or absence of the combined superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic EUK-134 (20 μM) and then exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h. A) Equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with anti-K8 and -K18 antibodies. Bars represent means ± sd of 3 independent experiments. A representative autoradiogram is shown. B) Cells were fixed and processed for indirect immunofluorescence using anti-K8/K18. In cells exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h, the keratin IF network was extensively disassembled (left panel). In cells exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h in the presence of EUK-134, the keratin IF network was unaffected compared with that in normoxic control cells (Fig. 1C⤻). C) Rat ATII cells were incubated in the presence or absence of EUK-134 (20 μM) and then incubated under 21 or 1.5% O2 for 24 h. One hour before hypoxic exposure, cells were loaded with DCFH-DA (10 μM) for 60 min. CT, control. Data are means ± sd of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

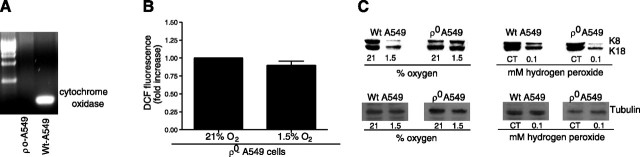

To determine whether ROS generated by the mitochondria during hypoxia are involved in coupling the O2 sensor (i.e., the mitochondria) to the disassembly of the keratin IF network in A549 cells, we generated ρ0-A549 cells. ρ0-A549 cells are deficient in mitochondrial DNA-derived proteins and are not capable of mitochondrial respiration because they lack key components of the electron transfer chain (19)⤻. As shown in Fig. 5A⤻, we generated ρ0-A549 cells that were depleted of mitochondrial DNA, which lack the respiratory chain catalytic subunit (cytochrome oxidase II). Without a functional electron transport chain, ρ0-A549 cells cannot regulate normal redox potential and cannot generate ROS when exposed to 1.5% O2 (Fig. 5B⤻). There was no change in the assembly dynamics of keratin IF network in ρ0-A549 cells exposed to 1.5% O2 (Fig. 5C⤻); however, when ρ0-A549 cells were incubated with t-H2O2, there was a significant decrease in keratin 8 and 18 protein levels (Fig. 5C⤻). These results suggest that mitochondria-generated ROS mediate the degradation of keratin IF.

Figure 5.

Effect of mitochondrial ROS on keratin IF protein. A) Southern blot analysis of total cellular DNA from wild-type (Wt) and ρ0-A549 cells. Hybridization was performed with a cytochrome oxidase subunit II probe, spanning bp 7757–8195, generated by RT-PCR. B) ρ0-A549 cells were incubated with DCFH-DA (10 μM) for 60 min at 21 or 1.5% O2. Fluorescence was measured in cell lysates. Data were normalized to values obtained from normoxic controls. Bars represent means ± sd of 3 experiments. C) Wild-type A549 cells and ρ0-A549 cells were exposed to 21 or 1.5% O2 or 100 μM t-H2O2. Equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with anti-K8 and -K18 antibodies. A representative autoradiogram is shown from 4 independent experiments.

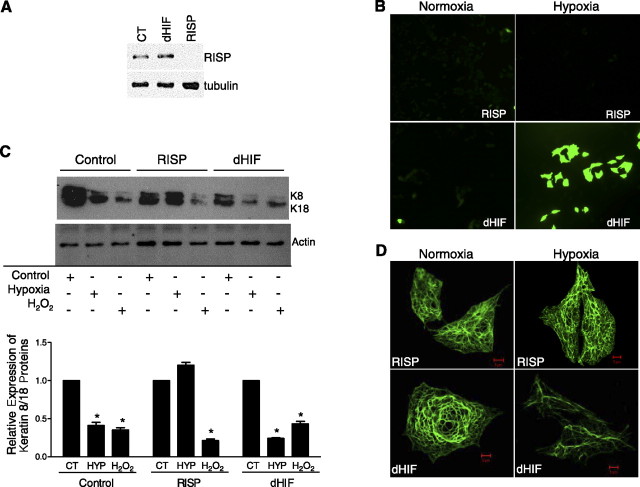

To further test our hypothesis that ROS generated at complex III are involved in the hypoxia-mediated reorganization of keratin IF, we used an siRNA knockdown strategy against the RISP; this protein is required for complex III to function properly. A549 cells transfected with siRNA against the RISP displayed a significant decrease in iron-sulfur protein levels compared with those in cells transfected with dHIF (used as an internal control) (Fig. 6A⤻). Furthermore, RISP knockdown decreases hypoxia-induced ROS production (Fig. 6B⤻). Importantly, there was no change in the keratin protein levels in hypoxic A549 cells that were transfected with siRNA against RISP compared with levels in hypoxic A549 cells that were transfected with siRNA against dHIF as demonstrated by Western blot and immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6C, D⤻).

Figure 6.

Site III of the mitochondrial electron transport chain is required for hypoxia-induced oxidant production and disassembly of keratin IF network. A) Protein abundance of the RISP was measured by immunoblotting in a stable line of A549 cells expressing a shRNA against the RISP or a control shRNA, dHIF. B) These cells were incubated under 21 or 1.5% O2 in the presence of DCFH-DA (10 μM) for 60 min. Representative photomicrographs of DCFH fluorescence. C) Control (CT) A549 cells, RISP-A549 cells, and dHIF-A549 cells were exposed to 21 or 1.5% O2 for 24 h or to 100 μM t-H2O2 for 120 min. Equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with anti-K8 and -K18 antibodies and anti-actin. A representative autoradiogram is shown. Bars represent means ± sd of 3 to 5 determinations performed independently, *P < 0.05. HYP, hypoxia. D) Cells were fixed and processed for indirect immunofluorescence using anti-K8/K18. In RISP-A549 cells exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h, the keratin IF network was unaffected compared with that in normoxic RISP-A549 cells. In dHIF-A549 cells exposed to 1.5% O2 for 24 h, the keratin IF network was disassembled compared with that in normoxic dHIF-A549 cells.

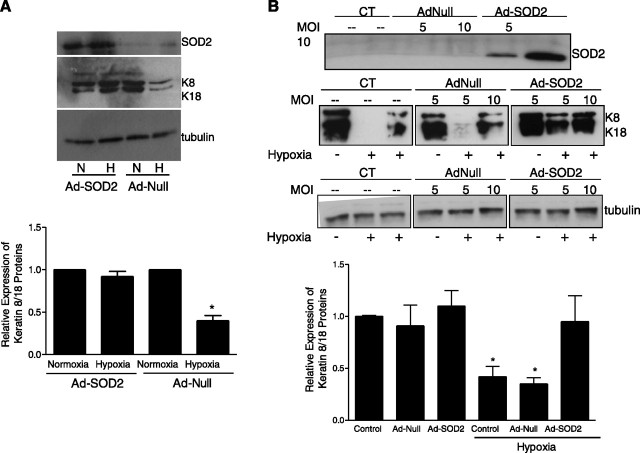

During hypoxia ROS are initially produced as superoxides, which subsequently are converted to H2O2 in the mitochondria by SOD2. To determine whether overexpression of the ROS scavenger SOD2 would prevent the hypoxia-induced decrease in keratin IF proteins, spontaneously breathing rats were infected with an adenovirus expressing SOD2 (AdSOD2, 2–4×109 pfu) and compared with rats infected with a null virus (AdNull, 2–4×109 pfu). Seven days after infection, rats were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia (21 or 8% O2, respectively) for 24 h. ATII cells were subsequently isolated, total cells lysates were prepared, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-SOD2. There was abundant expression of SOD2 in AdSOD2-infected rats compared with that in AdNull-infected rats (Fig. 7A⤻). Overexpression of SOD2 prevented the hypoxia-mediated decrease in keratin IF protein (Fig. 7A⤻). Adnull-infected hypoxic rats had a significant decrease in keratin 8 and 18 protein levels compared with those in normoxic control and AdSOD2-infected hypoxic rats (Fig. 7A⤻). These results were then confirmed in the in vitro model of hypoxia: A549 cells were transfected with adenoviral vectors expressing SOD1 and SOD2 (Ad-SOD1 and Ad-SOD1, respectively) and compared with cells transfected with a null virus [AdNull, 5 and 10 multiplicity of infection (MOI)] or untreated control cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, total cell lysates were prepared, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-SOD2. As shown in Fig. 7A⤻, in AdSOD2-transfected cells there was abundant expression of the SOD2 protein. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia (21 or 1.5% O2, respectively) for 24 h; keratin-enriched cytoskeleton preparations were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred, and immunoblotted with anti-keratin 8 and 18. There was no change in the assembly dynamics of the keratin IF network (i.e., K8/K18 protein levels were unchanged) in hypoxic A549 cells that overexpressed SOD2 compared with hypoxic, untreated A549 cells, as demonstrated by Western blot (Fig. 7B⤻). In contrast, there was no protective effect observed in A549 cells that overexpressed SOD1; the keratin proteins levels were decreased after exposure to hypoxia (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Rats were infected with AdSOD2 and compared with sham and Adnull-infected rats. A) Seven days after infection, rats were exposed to either 21 or 8% O2 for 24 h. Equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with anti-SOD2, anti-K8/K18, and anti-tubulin. A representative Western blot of the SOD2 protein abundance in lung tissue from Adnull- and AdSOD2-infected rats is shown; each lane represents a single animal. Bars represent means ± sd of 3 determinations performed independently. N, normoxia; H, hypoxia. B) A549 cells were infected with adenovirus vectors overexpressing SOD2. Twenty-four hours after infection, the cells were exposed to 21 or 1.5% O2 for 24 h. Equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with anti-SOD2, anti-K8/K18, and anti-tubulin. Representative Western blots of each of the proteins in Adnull- and AdSOD2-infected A549 cells at 5 and 10 MOI are shown. Bars represent means ± sd of 3 to 5 determinations performed independently (separate infections at 10 MOI). *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The relationship between hypoxia and the production of ROS is controversial (22)⤻, and the relationship between ROS and keratin IF network has not been described previously. This study demonstrates that hypoxia promotes the disassembly and degradation of keratin IF proteins in alveolar epithelial cells via mitochondria-generated ROS. We and others have reported that exposure of cells or tissue to moderate hypoxia (Po2=7–20 mm Hg) increases the production of mitochondria-generated ROS (19)⤻. In fact, these levels of oxygen are sufficient to generate nanomolar concentrations of ROS. The production of ROS is directly related to the degree and duration of the hypoxic exposure (19)⤻. As shown in Figs. 3⤻ and 4⤻, we observed that the oxidant-sensitive fluorescent dye 2′,7′-DCFH-DA is oxidized in alveolar epithelial cells during exposure to hypoxia, indicating that ROS are generated; the use of these dyes to measure ROS production has been reported previously (25⤻, 35⤻36⤻37)⤻. The mitochondrial electron transport chain can generate superoxide anions at complexes I, II, and III (17)⤻. Complexes I and II generate superoxide into the mitochondrial matrix, whereas complex III has the ability to generate superoxide into both the mitochondrial intermembrane space and the mitochondrial matrix. Complex III produces superoxide anions from the radical ubisemiquinone during the Q cycle. In the present study, inhibition of the electron transport chain with rotenone (site I) plus TTFA (site II) blocked the ROS signal during hypoxia, whereas AA, an inhibitor of complex III, increased ROS production (Fig. 3⤻). Superoxide generated within the mitochondria matrix can be converted to H2O2 by manganese SOD (SOD2) and H2O2 can then be degraded by mitochondrial glutathione peroxidase. Alternatively, superoxide generated in the mitochondria intermembrane space can be converted to H2O2 by copper-zinc SOD (SOD1). H2O2 can then be metabolized to molecular oxygen and water by catalase. EUK-134 is both a SOD and a catalase mimetic and can effectively detoxify oxygen radicals (33)⤻. Pretreatment with EUK-134 prevented the hypoxia-mediated disassembly/degradation of keratin protein in alveolar epithelial cells. Our findings are similar to those of other investigators who have demonstrated improved protection against oxidant stress with the use of EUK-134 compared with other antioxidants (33⤻, 38)⤻. Importantly, we demonstrate that both in vivo and in vitro overexpression of SOD2 was protective against the ROS-mediated disassembly and degradation of keratin IF proteins.

Another approach that we used to prevent superoxide production during hypoxia was to generate cells deficient in cytochrome c and by expression of an RNA interference targeting the RISP (39)⤻. ρ0-A549 cells, which are deficient in cytochrome c, exposed to 1.5% O2 failed to increase DCFH oxidation and to decrease keratin protein levels (Fig. 5⤻). However, ρ0-A549 cells incubated with H2O2 had disassembled keratin IF networks and a decrease in keratin protein abundance (Fig. 5⤻), indicating that these cells were still functionally intact. As an alternative to ρ0 cells, we transfected A549 cells with siRNA against the RISP (a component of complex III); cells transfected with siRNA against the RISP displayed a significant decrease in iron-sulfur protein levels, and, importantly, their keratin IF network was not altered in response to hypoxia. Further, the change in keratin protein expression is not a consequence of cell death nor is it associated with reduced cellular energy production due to oxygen deprivation (Fig. 2⤻). In fact, A549 cells exposed to 1.5% oxygen had normal levels of ATP. Interestingly, the hypoxia-mediated disassembly and degradation of keratin protein may be specific because the actin and tubulin protein levels were unchanged (Fig. 1⤻). Collectively, these results suggest that ROS generated in complex III of the mitochondria are required for the hypoxia-mediated disassembly and degradation of keratin IF proteins.

The other major source of ROS generation in the cell is the plasma membrane NAD(P)H oxidase (40)⤻. NAD(P)H oxidase is a multiprotein complex formed by the assembly of resident membrane proteins, including gp91phox and p22phox, and by the recruitment of cytosolic proteins, including p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, and the small GTPases Rac1 and Rac2 (41)⤻. Natarajan and colleagues (42)⤻ demonstrated that NAD(P)H oxidase is primarily responsible for ROS generation in response to hyperoxia; however, the role for NAD(P)H oxidase in hypoxia is less clear. One possibility is that mitochondria-generated ROS may serve as a sensor signaling the kinase-mediated assembly of the NAD(P)H oxidase that then amplifies the ROS signal. However, mice with a targeted deletion of the gp91phox subunit of NAD(P)H oxidase exhibit normal pulmonary vasoconstriction in response to hypoxia (43)⤻. These observations suggest that NAD(P)H oxidase may not be a requirement for sensing in hypoxia; however, it is possible that alternative isoforms of the gp91phox may exist and compensate for the loss of gp91phox in this animal model. Relevant to our study are the data in Figs. 5⤻ and 6⤻, in which mitochondrial ROS production is ablated, preventing the disassembly and degradation of keratin proteins under hypoxic conditions.

We propose that in hypoxic alveolar epithelial cells the initial ROS signaling event that mediates the degradation of keratin, a key structural protein, is derived from the mitochondria. These newly produced ROS may serve as signaling molecules to activate signal transduction pathways and affect the assembly dynamics of the keratin IF network. Evidence to support this hypothesis comes from our observations that respiration-deficient cells or cells treated with mitochondrial inhibitors fail to generate ROS and the keratin IF network is not disassembled or degraded after exposure to hypoxia. Recently, it was reported that mitochondria-generated ROS were required for hypoxia-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3/6 and p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase (14)⤻. p38 MAPK has been shown to associate with K8 and phosphorylate K8 Ser-73 in vivo. Phosphorylation of this serine residue has been reported to be associated with keratin filament disassembly (44)⤻ and keratin degradation (5⤻, 7)⤻. These data support our hypothesis that mitochondria-generated ROS are involved in keratin filament disassembly and degradation.

The biological function associated with the hypoxia-mediated keratin IF network disassembly and degradation in epithelial cells requires further investigations, although the reorganization of the IF network may be a cytoprotective mechanism. IFs interact with signaling pathways involved in cell survival. For example, the IF protein nestin forms a scaffold with cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) (45)⤻, thereby regulating the apoptosis-inducing activity of Cdk5 during oxidant-induced cell death (46)⤻. One interpretation of these data is that nestin plays a cytoprotective role in asymmetric cell division of neuronal stem cells, during which one daughter cell survives and the other undergoes apoptosis. The surviving daughter cell has a high nestin content, in contrast to the apoptotic cell, which is low in nestin content but has large amounts of the proapoptotic protein Par-4 (47)⤻. Likewise, K8 sequesters the proapoptotic JNK after death receptor stimulation (48)⤻. The interaction with keratin filaments may keep JNK from phosphorylating proapoptotic nuclear transcription factor targets, because c-Jun phosphorylation was clearly reduced under these conditions (48)⤻. We could extend our observations and speculate that the collapse of the keratin IF network after exposure to hypoxia may limit the activity of mitochondrial-generated ROS by affecting the intracellular organization and location of mitochondria.

Mitochondria are situated proximal to IFs in several cell types (49⤻, 50)⤻ and may play an important role in mitochondrial function. An important functional link between IFs and mitochondria comes from findings in desmin-null mice (51⤻, 52)⤻, which develop cardiovascular lesions, dilated cardiomyopathy, and skeletal myopathy (53⤻, 54)⤻. The heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria of desmin-null mice have an altered morphology and intracellular distribution. These alterations lead to changes in mitochondrial function, which differ somewhat in different muscle types, including decreased maximal respiration rate, lower ADP-stimulated oxygen consumption, and decreased cytochrome c levels in association with relocation of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein from the mitochondrial inner membrane to the cytoplasm proximal to the outer membrane (55⤻, 56)⤻. Although the effect of IFs on mitochondrial functions (e.g., apoptosis and energy metabolism), turnover, and intracellular organization are clear, significant details as to specific interactions between the mitochondria and IFs remain to be elucidated.

Alternatively, the disassembly and degradation of the keratin IF network may be required for cell migration in a hypoxic environment. In other words cells may be required to move to a nutrient-rich environment (high oxygen levels) from a nutrient-poor environment (low oxygen levels). Several studies indicate a role for keratin IFs in moderating cell migration. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex cell lines carrying mutations in either K14 or K5 keratin migrate faster in a scratch wound assay than in a control keratinocyte cell line (57)⤻. Ablation of K6 by gene targeting of both K6a and K6b isoforms reveals that K6-negative cells display enhanced motility in vitro (58)⤻. Simple epithelial keratins have also been implicated in cell migration. Perinuclear reorganization of the K8/18 network by sphingosylphosphorylcholine increases cellular elasticity and migration (59)⤻. However, studies on the role of simple epithelial keratins in the migration of alveolar epithelial cells are incomplete and warrant further investigations.

Our data strongly suggest that mitochondria-derived ROS are involved in the hypoxia-mediated disassembly and degradation of keratin IFs in alveolar epithelial cells.

References

- 1.Herrmann, H., Bar, H., Kreplak, L., Strelkov, S. V., Aebi, U. (2007) Intermediate filaments: from cell architecture to nanomechanics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. ,562-573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim, S., Coulombe, P. A. (2007) Intermediate filament scaffolds fulfill mechanical, organizational, and signaling functions in the cytoplasm. Genes Dev. ,1581-1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moll, R., Franke, W. W., Schiller, D. L., Geiger, B., Krepler, R. (1982) The catalog of human cytokeratins: patterns of expression in normal epithelia, tumors and cultured cells. Cell ,11-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schweizer, J., Bowden, P. E., Coulombe, P. A., Langbein, L., Lane, E. B., Magin, T. M., Maltais, L., Omary, M. B., Parry, D. A. D., Rogers, M. A., Wright, M. W. (2006) New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. J. Cell Biol. ,169-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridge, K. M., Linz, L., Flitney, F. W., Kuczmarski, E. R., Chou, Y. H., Omary, M. B., Sznajder, J. I., Goldman, R. D. (2005) Keratin 8 phosphorylation by protein kinase Cδ regulates shear stress-mediated disassembly of keratin intermediate filaments in alveolar epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. ,30400-30405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sivaramakrishnan, S., DeGiulio, J. V., Lorand, L., Goldman, R. D., Ridge, K. M. (2008) Micromechanical properties of keratin intermediate filament networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. ,889-894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaitovich, A., Mehta, S., Na, N., Ciechanover, A., Goldman, R. D., Ridge, K. M. (2008) Ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of keratin intermediate filaments in mechanically stimulated A549 cells. J. Biol. Chem. ,25348-25355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou, Y. H., Bischoff, J. R., Beach, D., Goldman, R. D. (1990) Intermediate filament reorganization during mitosis is mediated by p34cdc2 phosphorylation of vimentin. Cell ,1063-1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galarneau, L., Loranger, A., Gilbert, S., Marceau, N. (2007) Keratins modulate hepatic cell adhesion, size and G1/S transition. Exp. Cell Res. ,179-194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert, S., Ruel, A., Loranger, A., Marceau, N. (2008) Swith in Fas-activated death signaling pathway as result of keratin 8/18 intermediate filament loss. Apoptosis ,1479-1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs, E., Cleveland, D. W. (1998) A structural scaffolding of intermediate filaments in health and disease. Science ,514-519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ku, N. O., Zhou, X., Toivola, D. M., Omary, M. B. (1999) The cytoskeleton of digestive epithelia in health and disease. Am. J. Physiol. ,G1108-G1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell, E. L., Emerling, B. M., Chandel, N. S. (2005) Mitochondrial regulation of oxygen sensing. Mitochondrion ,322-332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emerling, B. M., Platanias, L. C., Black, E., Nebreda, A. R., Davis, R. J., Chandel, N. S. (2005) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for hypoxia signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. ,4853-4862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandel, N. S., Maltepe, E., Goldwasser, E., Mathieu, C. E., Simon, M. C., Schumacker, P. T. (1998) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. ,11715-11720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandel, N. S., Schumacker, P. T. (2000) Cellular oxygen sensing by mitochondria: old questions, new insight. J. Appl. Physiol. ,1880-1889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turrens, J. F. (2003) Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J. Physiol. (Lond.) ,335-344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litvan, J., Briva, A., Wilson, M. S., Budinger, G. R., Sznajder, J. I., Ridge, K. M. (2006) β-Adrenergic receptor stimulation and adenoviral overexpression of superoxide dismutase prevent the hypoxia-mediated decrease in Na,K-ATPase and alveolar fluid reabsorption. J. Biol. Chem. ,19892-19898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dada, L. A., Chandel, N. S., Ridge, K. M., Pedemonte, C., Bertorello, A. M., Sznajder, J. I. (2003) Hypoxia-induced endocytosis of Na,K-ATPase in alveolar epithelial cells is mediated by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and PKC-ζ. J. Clin. Invest. ,1057-1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon, M., Moir, R. D., Prahlad, V., Goldman, R. D. (1998) Motile properties of vimentin intermediate filament networks in living cells. J. Cell Biol. ,147-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prahlad, V., Yoon, M., Moir, R. D., Vale, R. D., Goldman, R. D. (1998) Rapid movements of vimentin on microtubule tracks: kinesin-dependent assembly of intermediate filament networks. J. Cell Biol. ,159-170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weissmann, N., Schermuly, R. T., Ghofrani, H. A., Hanze, J., Goyal, P., Grimminger, F., Seeger, W. (2006) Triggered by an increase in reactive oxygen species?. Novartis Found. Symp. ,196-217 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature ,680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradford, M. M. (1974) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye-binding. Anal. Biochem. ,248-254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duranteau, J., Chandel, N. S., Kulisz, A., Shao, Z., Schumacker, P. T. (1998) Intracellular signaling by reactive oxygen species during hypoxia in cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. ,11619-11624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heberlein, W., Wodopia, R., Bartsch, P., Mairbaurl, H. (2000) Possible role of ROS as mediators of hypoxia-induced ion transport inhibition of alveolar epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Biol. ,L640-L648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou, Y. H., Goldman, R. D. (2000) Intermediate filaments on the move. J. Cell Biol. ,F101-F106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Budinger, G. R., Chandel, N., Shao, Z. H., Li, C. Q., Melmed, A., Becker, L. B., Schumacker, P. T. (1996) Cellular energy utilization and supply during hypoxia in embryonic cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. ,L44-L53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crawford, L. E., Milliken, E. E., Irani, K., Zweier, J. L., Becker, L. C., Johnson, T. M., Eissa, N. T., Crystal, R. G., Finkel, T., Goldschmidt-Clermont, P. J. (1996) Superoxide-mediated actin response in post-hypoxic endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. ,26863-26867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandel, N. S., McClintock, D. S., Feliciano, C. E., Wood, T. M., Melendez, J. A., Rodriguez, A. M., Schumacker, P. T. (2000) Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1α during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J. Biol. Chem. ,25130-25138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Budinger, G. R., Duranteau, J., Chandel, N. S., Schumacker, P. T. (1998) Hibernation during hypoxia in cardiomyocytes: role of mitochondria as the O2 sensor. J. Biol. Chem. ,3320-3326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lum, H., Roebuck, K. A. (2001) Oxidant stress and endothelial cell dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. ,C719-C741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melov, S., Ravenscroft, J., Malik, S., Gill, M. S., Walker, D. W., Clayton, P. E., Wallace, D. C., Malfroy, B., Doctrow, S. R., Lithgow, G. J. (2000) Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science ,1567-1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Budinger, G. R., Mutlu, G. M., Eisenbart, J., Fuller, A. C., Bellmeyer, A. A., Baker, C. M., Wilson, M., Ridge, K., Barrett, T. A., Lee, V. Y., Chandel, N. S. (2006) Proapoptotic bid is required for pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. ,4604-4609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Killilea, D. W., Hester, R., Balczon, R., Babal, P., Gillespie, M. N. (2000) Free radical production in hypoxic pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Biol. ,L408-L412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waypa, G. B., Chandel, N. S., Schumacker, P. T. (2001) Model for hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction involving mitochondrial oxygen sensing. Circ. Res. ,1259-1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waypa, G. B., Marks, J. D., Mack, M. M., Boriboun, C., Mungai, P. T., Schumacker, P. T. (2002) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger calcium increases during hypoxia in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Circ. Res. ,719-726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, H. L., Akinci, I. O., Baker, C. M., Urich, D., Bellmeyer, A., Jain, M., Chandel, N. S., Mutlu, G. M., Budinger, G. R. S. (2007) The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is required for lipopolysaccharide-induced lung endothelial cell death. J. Immunol. ,1834-1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunelle, J., Bell, E. L., Quesada, N. M., Vercauteren, K., Tiranti, V., Zeviani, M., Scarpulla, R. C., Chandel, N. S. (2005) Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. ,409-414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolin, M. S., Ahmad, M., Gupte, S. A. (2005) Oxidant and redox signaling in vascular oxygen sensing mechanisms: basic concepts, current controversies, and potential importance of cytosolic NADPH. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Biol. ,L159-L173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griendling, K. K., Sorescu, D., Ushio-Fukai, M. (2000) NAD(P)H oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ. Res. ,494-501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parinandi, N. L., Kleinberg, M. A., Usatyuk, P. V., Cummings, R. J., Pennathur, A., Cardounel, A. J., Zweier, J. L., Garcia, J. G. N., Natarajan, V. (2003) Hyperoxia-induced NAD(P)H oxidase activation and regulation by MAP kinases in human lung endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Biol. ,L26-L38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders, K. A., Sundar, K. M., He, L., Dinger, B., Fidone, S., Hoidal, J. R. (2002) Role of components of the phagocytic NADPH oxidase in oxygen sensing. J. Appl. Physiol. ,1357-1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ku, N.-O., Azhar, S., Omary, M. B. (2002) Keratin 8 phosphorylation by p38 kinase regulates cellular keratin filament reorganization: modulation by a keratin 1-like disease-causing mutation. J. Biol. Chem. ,10775-10782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sahlgren, C. M., Mikhailov, A., Vaittinen, S., Pallari, H.-M., Kalimo, H., Pant, H. C., Eriksson, J. E. (2003) Cdk5 regulates the organization of nestin and its association with p35. Mol. Cell. Biol. ,5090-5106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sahlgren, C. M., Pallari, H.-M., He, T., Chou, Y. H., Goldman, R. D., Eriksson, J. E. (2006) A nestin scaffold links Cdk5/p35 signaling to oxidant-induced cell death. EMBO J. ,4808-4819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bieberich, E., MacKinnon, S., Silva, J., Noggle, S., Condie, B. G. (2003) Regulation of cell death in mitotic neural progenitor cells by asymmetric distribution of prostate apoptosis response 4 (PAR-4) and simultaneous elevation of endogenous ceramide. J. Cell Biol. ,469-479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He, T., Stepulak, A., Holmstrom, T. H., Omary, M. B., Eriksson, J. E. (2002) The intermediate filament protein keratin 8 is a novel cytoplasmic substrate for c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J. Biol. Chem. ,10767-10774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner, O. I., Lifshitz, J., Janmey, P. A., Linden, M., McIntosh, T. K., Leterrier, J.-F. (2003) Mechanisms of mitochondria-neurofilament interactions. J. Neurosci. ,9046-9058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uttam, J., Hutton, E., Coulombe, P. A., Anton-Lamprecht, I., Yu, Q. C., Gedde-Dahl, T., Fine, J. D., Fuchs, E. (1996) The genetic basis of epidermolysis bullosa simplex with mottled pigmentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. ,9079-9084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Capetanki, Y. (2002) Desmin cytoskeleton: a potential regulator of muscle mitochondrial behavior and function. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. ,339-348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paulin, D., Li, Z. (2004) Desmin: a major intermediate filament protein essential for the structural integrity and function of muscle. Exp. Cell. Res. ,1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Milner, D. J., Weitzer, G., Tran, D., Bradley, A., Capetanaki, Y. (1996) Disruption of muscle architecture and myocardial degeneration in mice lacking desmin. J. Cell Biol. ,1255-1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li, Z., Colucci-Guyon, E., Pincon-Raymond, M., Mericskay, M., Pournin, S., Paulin, D., Babinet, C. (1996) Cardiovascular lesions and skeletal myopathy in mice lacking desmin. Dev. Biol. ,362-366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milner, D. J., Mavroidis, M., Weisleder, N., Capetanaki, Y. (2000) Desmin cytoskeleton linked to muscle mitochondrial distribution and respiratory function. J. Cell Biol. ,1283-1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linden, M., Li, Z., Paulin, D., Gotow, T., Leterrier, J.-F. (2001) Effects of desmin gene knockout on mice heart mitochondria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. ,333-341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morley, S. M. (2003) Generation and characterization of epidermolysis bullosa simplex cell lines: scratch assays show faster migration with disruptive keratin mutations. Br. J. Dermatol. ,46-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong, P., Coulombe, P. A. (2003) Loss of keratin 6 (K6) proteins reveals a function for intermediate filaments during wound repair. J. Cell Biol. ,327-337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beil, M., Micoulet, A., von Wichert, G., Paschke, S., Walther, P., Omary, M. B., Van Veldhoven, P. P., Gern, U., Wolff-Hieber, E., Eggermann, J., Waltenberger, J., Adler, G., Spatz, J., Seufferlein, T. (2003) Sphingosylphosphorylcholine regulates keratin network architecture and visco-elastic properties of human cancer cells. Nat. Cell Biol. ,803-811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]