Summary

Neurons are highly dependent on mitochondria, but little is known about how they react to a local mitochondrial oxidative insult. We therefore developed a protocol in primary hippocampal cultures that combines the photosensitizer mito-KillerRed with fluorescent biosensors and photoactivatable GFP. We found in both the soma and dendrites that neurons restrict the local increase in mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species and the decrease in ATP production to the damaged compartment, by quarantining mitochondria. Although the cytosol of both the soma and dendrites became oxidized after mito-KillerRed activation, dendrites were more sensitive to the oxidative insult. Importantly, the impaired mitochondria exhibited decreased motility and fusion, thereby avoiding the spread of oxidation throughout the neuron. These results establish how neurons manage oxidative damage and increase our understanding about the somatodendritic regulation of mitochondrial functions after a local oxidative insult.

Subject Areas: Physiology, Neuroscience, Cell Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

An oxidative insult is contained locally to the damaged region of a neuron

-

•

ATP levels decrease only in the damaged region of the soma or dendrite

-

•

ATP levels increase in the regions distal to the oxidative insult

-

•

Stressed mitochondria are fragmented, with a decreased motility and fusion rate

Physiology; Neuroscience; Cell Biology

Introduction

Mitochondria are particularly important in neurons, which rely almost exclusively on the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system to produce ATP (Harris et al., 2012). ATP is essential for many neuronal processes, including the maintenance of the membrane potential; the synthesis, release, and recapture of neurotransmitters; and the reversal of ion flux through postsynaptic receptors. Furthermore, neurons are highly structured and elaborated cells, with different compartments having unique mitochondrial requirements (Misgeld and Schwarz, 2017).

Paradoxically, mitochondria are also the main source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), an inevitable by-product of electron transport chain activity, with this organelle being the first target of ROS toxicity (Grimm and Eckert, 2017). Neurons can counteract mitochondrial ROS (mROS) overload to a certain extent, due to cellular antioxidant defenses, mitochondrial dynamics (fusion/fission activity), and, in the case of more severe damage, removal of impaired organelles by mitophagy (reviewed in Cummins and Götz, 2017, Grimm and Eckert, 2017). These systems are believed to maintain the cellular reduction/oxidation balance and ATP generation, thereby promoting neuronal survival. However, the specific effects of mROS on mitochondrial bioenergetics, redox state, and mitochondrial dynamics in different neuronal compartments have not been systematically dissected.

Most methods to induce oxidative damage in cells are based on treatment with oxidative agents such as hydrogen peroxide (Lejri et al., 2017), mROS-inducing drugs such as paraquat (Schmuck et al., 2002), or inhibitors of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (Leuner et al., 2012, Stockburger et al., 2014). Importantly, these substances can not only disturb non-mitochondrial cell functions but also affect the entire cell. To overcome these limitations, more targeted optogenetic methods have been developed. A highly versatile tool is the photosensitizer KillerRed (KR), a protein that generates ROS in response to stimulation with green light, with subsequent cell death being demonstrated in a range of cell types (Bulina et al., 2006) and even in living organisms (Williams et al., 2013). Targeting this protein to mitochondria (mt-KR) enables not only the induction of ROS production in subsets of mitochondria through spatially restricted illumination but also the temporal control of the duration of the mt-KR-induced ROS production. This strategy mimics what is encountered at a cellular level in response to mitochondrial damage, by locally inducing ROS generation specifically within mitochondria without the confound of drugs acting on the entire cell, which can disrupt other mitochondrial and cellular functions. This method lends itself to study processes in a more “physiological” context, by inducing only limited oxidative stress and assessing how the cells cope with such an insult. Using such an approach, mt-KR-dependent ROS production has previously been shown to initiate mitophagy locally (Ashrafi et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2012, Yang and Yang, 2011), and to induce the local elimination of photostimulated mt-KR-expressing dendrites and spines (Ertürk et al., 2014). However, no studies have focused on upstream events, namely, the regulation in neurons of the redox balance and ATP synthesis after mt-KR-induced acute and local mitochondrial oxidative damage.

Therefore, we asked whether it would be possible to monitor changes in redox state and ATP turnover in neurons after an acute mitochondrial oxidative insult in real time; how neurons cope with local, “physiologically relevant” mitochondrial stress when confined to areas in the soma and dendrites; and whether there were compartment-specific differences. To address these questions, we used a combination of techniques, which included light-induced mt-KR stimulation to generate mitochondrial-derived ROS, fluorescent biosensors to investigate the mitochondrial and cytosolic redox state (Waypa et al., 2010) as well as the ATP/ADP ratio (Berg et al., 2009), and a mitochondrially targeted photo-activatable GFP to track mt-KR-damaged mitochondria (Karbowski et al., 2004).

Results

mt-KR Photostimulation Induces Mitochondrial Oxidation, Increases Cytosolic Oxidation, and Decreases ATP Levels

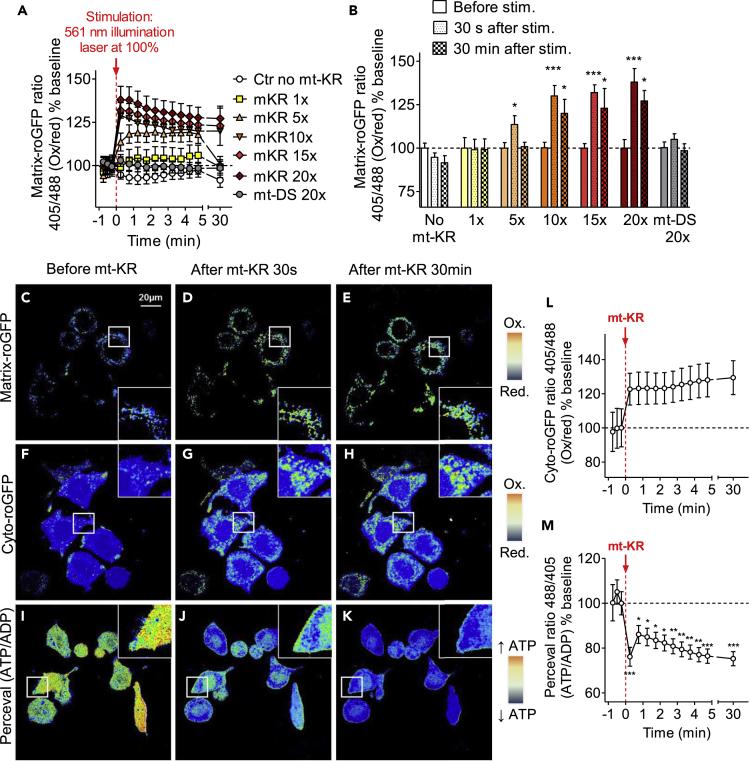

We first established a protocol in N2a cells to determine whether the mitochondrial redox state could be monitored in real time before and after mt-KR photostimulation (Figures 1A and 1B). N2a cells were co-transfected with mt-KR and matrix-roGFP, a mitochondrial redox biosensor that indicates the ratio of oxidation/reduction based on the ratio of fluorescence intensity at two excitations, 405 and 488 nm (with higher ratios of 405/488 nm reflecting a more oxidized environment) (Waypa et al., 2010). It has previously been shown in HeLa cells that activation of mt-KR by photobleaching produces ROS in a dose-dependent manner that can be visualized with the fluorescent dye OxyBURST as an ROS detector (Wang et al., 2012). Guided by this study, and to verify whether matrix-roGFP was able to detect different degrees of mitochondrial oxidation after acute bursts of ROS in mitochondria, mt-KR photostimulation was performed by scanning N2a cells with a 561-nm laser set at 100% to bleach (photostimulate) mt-KR. Several scanning paradigms were tested: no mt-KR scans (control) and 1–20 scans. The mitochondrially targeted red fluorescent protein mito-DsRed was used as control (20 scans, mt-DS 20×). Compared with baseline (before mt-KR photostimulation), we observed an increase in the 405/488 nm ratio, indicating increased mitochondrial oxidation in the mt-KR groups that had been scanned 5, 10, 15, or 20 times (up to 38% increased oxidation 30 s after 20 mt-KR stimulation, Figures 1A and 1B). The oxidative stress remained significantly elevated over a period of 30 min after stimulation. No increase was observed with mt-DS, or with 0 or 1 scan. Although a “dose effect” of photostimulation on mitochondrial oxidation could be observed with increasing numbers of scans, there were no significant differences between cells that had received 10, 15, or 20 scans. Thus, in all subsequent experiments, 20 scans were used to photostimulate mt-KR. Figures 1C–1E display the corresponding fluorescence ratio images of the matrix-roGFP before and after 20 mt-KR scans.

Figure 1.

Redox State and ATP/ADP Ratio before and after mt-KR Activation in N2a Cells

(A) “Dose effect” of mt-KR photoactivation on the mitochondrial redox state. To activate mt-KR-induced ROS production, cells were scanned between 1 and 20 times (1×–20×). The fluorescence ratio of the matrix-roGFP protein (405 nm/488 nm = oxidized/reduced state) was measured every 30 s for 5 min after photostimulation, and again after 30 min. Values represent the mean ± SEM of n = 10–15 cells/group from 3 independent experiments.

(B) Mitochondrial redox state before and 30 s and 30 min after mt-KR activation in the different photostimulated groups. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 10–15 cells. One-way ANOVA (repeated measurements) and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test versus baseline (before mt-KR), *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

(C–E) Fluorescence ratio (405 nm/488 nm) of the matrix-roGFP protein before (C), 30 s after (D), and 30 min after (E) mt-KR activation. An increase in the signal indicates an increase in oxidation in the mitochondria. For each representative image, a zoomed-in image is shown (400%).

(F–H) Fluorescence ratio (405 nm/488 nm) of the cyto-roGFP protein before (F), 30 s after (G), and 30 min after (H) mt-KR activation. An increase of the signal indicates an increase in oxidation in the cytosol. For each representative image, a zoomed-in image is shown (400%).

(I–K) Fluorescence ratio (488 nm/405 nm) of the Perceval protein (ATP/ADP ratio) before (I), 30 s after (J), and 30 min after (K) mt-KR activation. A decrease in the signal indicates a decrease in the ATP/ADP ratio. For each representative image, a zoomed-in image is shown (400%).

(L) Cytosolic redox state in cyto-roGFP-transfected cells after acute mt-KR activation (scanned 20×). Values represent the mean ± SEM of 19 cells from 3 independent experiments.

(M) ATP/ADP ratio in Perceval-transfected cells after acute mt-KR activation (scanned 20×) and analysis of the signal before, 30 s after, and 30 min after mt-KR activation. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 18 cells from 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA (repeated measurements) and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test versus baseline (before mt-KR), *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

mt-DS, mito-DsRed.

We then tested whether it was also possible to monitor the cytosolic redox state (using cyto-roGFP) and the ATP/ADP ratio (using the fluorescent reporter “Perceval,” which competitively binds to ATP and ADP and changes the fluorescence intensity at excitations of 488 and 405 nm, with a higher 488/405 nm ratio reflecting higher ATP levels) (Berg et al., 2009). Although the cytosolic redox state was increased after mt-KR stimulation (Figures 1F–1H and 1L), this result was not statistically significant, due to high intercellular variation. Of note, the cyto-roGFP signal after mt-KR stimulation was mainly punctate (Figures 1G and 1H), suggesting that the oxidation observed in the cytosol was due to increased mROS levels. We displayed the fluorescence ratio images of the Perceval signal before and after 20 mt-KR stimulations (Figures 1I–1K) and observed a 25% decrease in the ATP/ADP ratio 30 s after mt-KR stimulation (Figure 1M). This ratio remained stable even 30 min after stimulation.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that it is possible to monitor the mitochondrial and cytosolic redox state, as well as ATP turnover, before and after an acute oxidative insult in N2a cells in real time. Specifically, mt-KR photostimulation was found to induce mitochondrial oxidation, increased cytosolic oxidation, and decreased ATP levels.

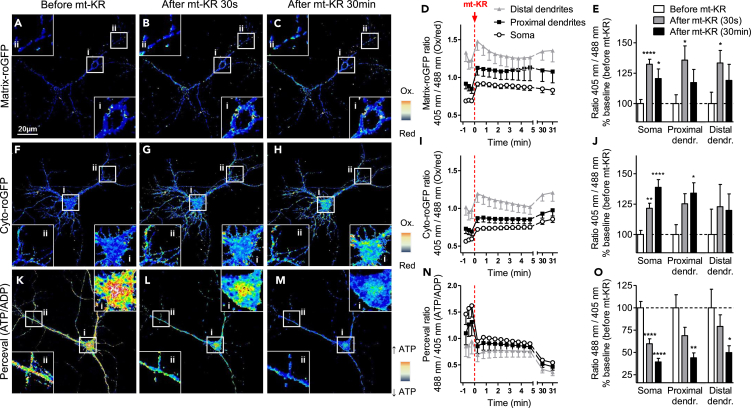

We next extended these findings to primary hippocampal neurons, given that neurons more generally have specialized energy requirements and are specifically sensitive to oxidative stress (Grimm and Eckert, 2017). They are also highly compartmentalized, with distinctive energy requirements in the different compartments (reviewed in Harris et al., 2012). Therefore, we characterized the mito- and cyto-redox states and ATP/ADP ratio separately in the soma, proximal dendrites (within 25 μm distance to the soma), and distal dendrites (beyond 25 μm distance to the soma) (Figure 2). Interestingly, the basal mito- and cyto-redox states (before mt-KR stimulation) was almost twice as oxidized in the distal dendrites when compared with the soma (mito-redox state: soma versus proximal dendrite p < 0.001, proximal versus distal dendrites p < 0.01; cyto-redox state: soma versus proximal dendrites p < 0.001, proximal versus distal dendrites p < 0.05; one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons) (Figures 2D and 2I). Also, the ATP/ADP ratio was lower in the distal dendrites when compared with the soma (soma versus distal dendrites p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons) (Figure 2N). No significant differences were observed between the soma and proximal dendrites.

Figure 2.

Somatodendritic Redox State and ATP/ADP Ratio before and after mt-KR Induced Oxidative Insult in Primary Hippocampal Neurons

(A–E) Fluorescence ratio (405 nm/488 nm) of the matrix-roGFP protein before (A), 30 s after (B), and 30 min after (C) mt-KR activation. For each representative image, a zoomed-in image is shown (400%). (D and E) Quantification of the signal in different neuronal compartments. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 19 cells from 3 independent hippocampal cultures.

(F–J) Fluorescence ratio (405 nm/488 nm) of the cytosolic roGFP protein before (F), 30 s after (G), and 30 min after mt-KR activation (H). For each representative image, a zoomed-in image is shown (400%). (I and J) Quantification of the signal in different neuronal compartments. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 11 cells from 3 independent hippocampal cultures.

(K–O) Fluorescence ratio (488 nm/405 nm) of the Perceval protein (ATP/ADP ratio) before (K), 30 s after (L), and 30 min after mt-KR activation (M). For each representative image, a zoomed-in image is shown (400%). (N and O) Quantification of the signal in different neuronal compartments. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 11 cells from 3 independent hippocampal cultures.

(E, J, and O) One-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test versus baseline (before mt-KR). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. mt-KR: mito-KillerRed.

We then applied our mt-KR stimulation paradigm of 20 scans to the neurons using whole-cell stimulation and compared the changes in the mito- and cyto-redox states and ATP/ADP ratio in the three neuronal compartments (Figures 2D, 2I, and 2N). We observed an induction of mitochondrial oxidation (+30–35%) 30 s after mt-KR activation in all three compartments (Figure 2E), which was slightly decreased by 30 min post-stimulation, but remained significantly elevated compared with baseline in the soma (Figures 2A–2E). Similarly, the cytosolic redox state was oxidized (+20–25% oxidation) 30 s post mt-KR stimulation in all three neuronal compartments, and this oxidation continued to increase after 30 min, especially in the soma (+38%) (Figures 2F–2J). Similar to what we had observed in N2a cells, the cyto-roGFP signal appeared punctate after mt-KR stimulation (Figures 2G and 2H), suggesting that the oxidation observed in the cytosol is due to the increased mROS levels triggered by mt-KR stimulation. A decrease in the ATP/ADP ratio was detected already 30 s after mt-KR stimulation (−40% in the soma) and kept further decreasing after 30 min in all three compartments (−60% in the soma, −56% in proximal dendrites, −50% in distal dendrites) (Figures 2K–2O).

Together, our results demonstrated that mt-KR stimulation of a whole neuron induces mitochondrial and cytosolic oxidation, coupled with a decrease in ATP levels in the soma and proximal and distal dendrites.

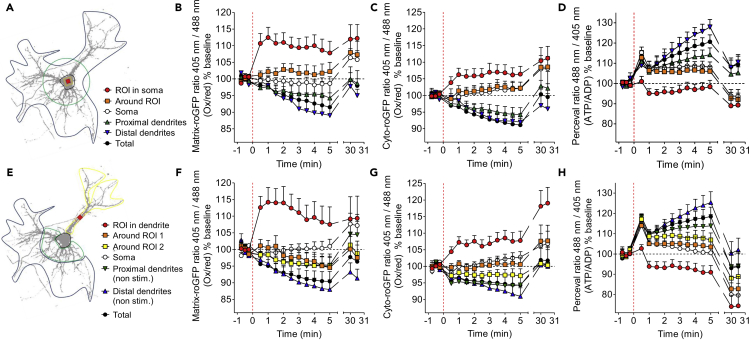

Focal Mitochondrial Oxidation Is Contained in the Oxidatively Damaged Region, with Dendrites Exhibiting Higher Sensitivity

We next aimed to investigate how neurons react to a local oxidative insult in either the soma or the dendrite, an analysis that may be more physiologically relevant than a global, whole-cell, oxidative insult (Figure 3). The neurons were again co-transfected with mt-KR and matrix-roGFP, cyto-roGFP, or Perceval. However, this time, only a small 10 μm2 region of interest (ROI) was stimulated in either the soma (Figure 3A) or the primary dendrite (Figure 3E). We found that the mitochondrial redox state was oxidized (+10%) already 30 s after stimulation, but importantly, this response was confined to the ROI (Figures 3B and 3F, Table S1). In the soma, mitochondrial oxidation remained elevated up to 30 min after stimulation (at which point the experiment was terminated), but it was slightly decreased in the dendrite. The global whole-cell mito-redox state (Figures 3B and 3F) and the cyto-redox state (Figures 3C and 3G) were reduced, as was the case for the non-stimulated distal dendrites (Figure 3F). However, a significant cytosolic oxidation occurred in the ROI 30 min after stimulation in the soma (+10%, Figure 2C) and to a greater extent in the dendrite (+19%, Figure 3G). The zones directly surrounding the ROI also displayed a slight cytosolic oxidation 30 min post-stimulation (Figures 3C and 3G, Table S1).

Figure 3.

Somatodendritic Redox State and ATP/ADP Ratio after Focal mt-KR Activation in the Soma or the Dendrites

(A) For analysis of events after focal soma stimulation, neuronal images were divided into the stimulated region of interest (ROI), representing a 10 μm2 area; the area directly surrounding the stimulated ROI; the soma; the proximal dendrites; and the distal dendrites.

(B–D) Mitochondrial redox state (B), cytosolic redox state (C), and ATP/ADP ratio (D) in different neuronal compartments after focal mt-KR activation in the soma. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 10–11 cells from three independent hippocampal cultures. Statistics are detailed in Table S1, and the corresponding images are displayed in Figure S1. The dashed line indicates the time of mt-KR activation.

(E) For the analysis of events after focal mt-KR activation in dendrites, neurons were divided into the stimulated ROI, representing a 10 μm2 area; the area directly surrounding the ROI (around ROI 1); the rest of the stimulated dendrite (around ROI 2); the soma; the non-stimulated proximal dendrites; and the non-stimulated distal dendrites.

(F–H) Mitochondrial redox state (F), cytosolic redox state (G), and ATP/ADP ratio (H) in different neuronal compartments after focal mt-KR activation in the dendrite. Values represent the mean ± SEM of 14–16 cells from 3 independent hippocampal cultures. Statistics are detailed in Table S1, and the corresponding images are displayed in Figure S2. The dashed line indicates the time of mt-KR activation.

Interestingly, although the ATP/ADP ratio was significantly decreased after 30 min in the stimulated small ROI in the soma (−10%, Figure 3D), there was an even greater reduction in the dendrite (−25%, Figure 3H). The zones surrounding the ROI in the dendrite also displayed a significant decrease in ATP 30 min after mt-KR stimulation (Figure 3H, Table S1). Conversely, in all other investigated regions (except for the ROI), a peak in ATP levels was observed directly after stimulation (at 30 s), followed by a progressive increase in the ATP/ADP ratio in the whole cell (total ATP/ADP), particularly in the proximal and distal dendrites. ATP levels increased up to 25% in the distal dendrite when the ROI was in the soma, and up to 23% in the non-stimulated dendrite when the ROI was in a dendrite, 5 min post-stimulation (Figures 3D and 3H). The corresponding fluorescence ratio images of matrix-roGFP, cyto-roGFP, and Perceval before and after mt-KR activation are shown for the soma (Figure S1) and the dendrite (Figure S2).

A Pearson correlation was performed to determine the link between mitochondrial oxidation and the ATP/ADP ratio over time after mt-KR stimulation (Table S2). A negative correlation was observed between the two parameters in all examined regions, except for the ROI and the surrounding zones in both the soma and dendrite (Table S2). This could suggest that the increase in mROS triggers a decrease in ATP production.

Together, these data demonstrate that in both the soma and the dendrite, mitochondrial oxidation is contained within the mt-KR-stimulated region. The cytosolic oxidation was slightly increased in the zone surrounding the ROI 30 min post-stimulation, suggesting that an excess of mROS, produced by mt-KR stimulation, was leaking from mitochondria to the cytosol. Furthermore, our findings suggest that dendrites are more sensitive to oxidative insult than the soma, with a higher increase in cytosolic oxidation and decreased ATP levels observed in the damaged region. Interestingly, ATP levels were decreased in the damaged region, again to a greater extent in the stimulated dendrite, but they were increased in the non-stimulated parts of the neuron, particularly the distal dendrites. We also revealed that variations in the ATP levels in the non-stimulated regions correlated with the redox state, because the ATP/ADP ratio decreased when oxidation increased.

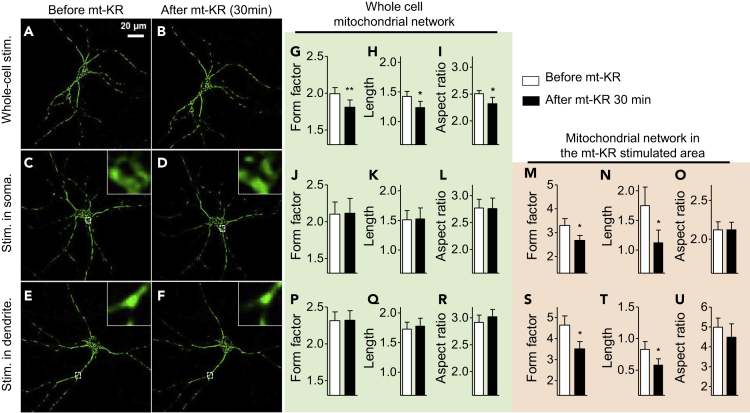

A Focal Oxidative Insult Results in Mitochondrial Fragmentation Only in the Damaged Region

Oxidative stress is known to induce rapid mitochondrial fragmentation, which is associated with cell death by apoptosis (Flippo and Strack, 2017). To investigate whether the acute oxidative insult induced here had an impact on the mitochondrial network, we assessed mitochondrial morphology before and after mt-KR stimulation (Figure 4). To detect subtle changes, we used a morphometry macro in ImageJ (Merrill et al., 2017). This allowed us to detect a slight but significant decrease in mitochondrial shape complexity (form factor), mitochondrial length, and mitochondrial interconnectivity/elongation (aspect ratio), 30 min after whole-cell mt-KR stimulation (Figures 4A, 4B, and 4G–4I). The global mitochondrial network was not altered after focal mt-KR stimulation in the soma (Figures 4C, 4D, and 4J–4L) or the dendrite (Figures 4E, 4F, and 4P–4R). However, fragmentation of the mitochondrial network was detected in the stimulated ROI in the soma (Figures 4C and 4D) and dendrite (Figures 4E and 4F) 30 min post-stimulation, as demonstrated by a decrease in the form factor (Figures 4M and 4S) and mitochondrial length (Figures 4N and 4T). No changes in the aspect ratio were observed (Figures 4O and 4U).

Figure 4.

Changes in Mitochondrial Morphology and Mobility after mt-KR Stimulation in Primary Hippocampal Neurons

(A–F) Pictures display mitochondrial network morphology (matrix-roGFP fluorescence signal at 488 nm) before and 30 min after mt-KR photoactivation in the whole neuron (A and B), in the soma (C and D), and in the dendrite (E and F). Insets are an 800% zoom of the stimulated area (dashed squares).

(G–U) Quantification of the mitochondrial morphology parameters after mt-KR photostimulation in the whole neuron (G–I), in the soma (J–L: whole-cell mitochondrial network, M–O: mitochondria in the stimulated area), and in the dendrite (P–R: whole-cell mitochondrial network, S–U: mitochondria in the stimulated area). (G, J, M, P, and S) Form factor (mitochondrial elongation), (H, K, N, Q, and T) mitochondrial length, and (I, L, O, R, and U) aspect ratio (mitochondrial interconnectivity). On average 1,000–3,000 mitochondria were analyzed per group (n = 10–11 neurons/group from 3 independent hippocampal cultures).

Values represent the mean ± SEM. Student's paired t test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

These data indicate that an acute oxidative insult to the whole neuron impairs mitochondrial network integrity. A focal oxidative insult induced mitochondrial fragmentation only in the damaged region, but was not severe enough to alter the global mitochondrial network, at least in the short term (i.e., within 30 min).

Decreased Mitochondrial Fusion and Motility after Focal Oxidative Insult

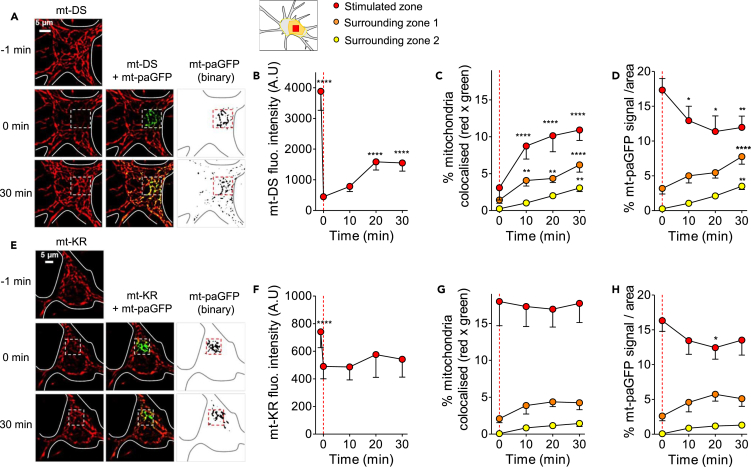

We next investigated the fate of damaged mitochondria in neurons in more detail. We co-transfected the neurons with mt-KR and photoactivatable mitochondrial paGFP (mt-paGFP), which allowed us to “track” damaged mitochondria based on the diffusion of the mt-paGFP fluorescence. Cells that were co-transfected with mt-paGFP and mt-DS were used as negative control, because mt-DS does not induce mitochondrial oxidation after photostimulation (Figures 1A and 1B). Again, only a small 10 μm2 area was stimulated in either the soma or in a dendrite resulting in bleaching of the mt-KR or mt-DS in the ROI, directly followed by mt-paGFP activation to visualize mt-KR/mt-DS-stimulated mitochondria (Figures 5 and 6). As indicators of mitochondrial dynamics, three parameters were measured (Hung et al., 2018): (1) fluorescence recovery after photostimulation (bleaching) in the ROI, (2) the percentage of colocalization of the red (mt-KR or mt-DS) and green signal (mt-paGFP) as an indicator of mitochondrial fusion in the ROI and surrounding zones (see Figures 5 and 6 inset), and (3) the percentage of the mt-paGFP-positive area in the ROI and surrounding zones as an indicator of the diffusion of the GFP signal, reflecting mitochondrial transport or fusion outside the stimulated zone. In mt-DS-stimulated neurons (Figure 5A), the fluorescence intensity plummeted in the ROI upon stimulation of the soma but then recovered by 30% after 30 min, reflecting efficient mitochondrial dynamics in this region (Figures 5B and 6I). In mt-KR-stimulated neurons (Figures 5E and 5F), a decrease in the fluorescence intensity was also observed (Figure 5B). The mt-KR fluorescence signal did not significantly increase in the ROI 30 min post-stimulation, suggesting that mitochondrial dynamics was impaired in the oxidatively stressed area (+5.6% increase, Figures 5F and 6I). Similar findings were obtained after stimulation of dendrites (Figures 6A, 6B, 6E, 6F, and 6I).

Figure 5.

Alterations of Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Soma after Focal mt-KR Activation

(A) Time-lapse imaging of mt-DS before and after photostimulation (left panel, dashed square indicates photobleached area). Fluorescence recovery in the stimulated region was monitored every 10 min for 30 min. mt-paGFP was photoactivated in the same region (middle panel), and colocalization with mt-DS was assessed every 10 min for 30 min in 3 zones: the stimulated region, the zone directly surrounding the stimulated region (zone 1), and the rest of the soma (zone 2, inset). The area of mt-paGFP fluorescence is displayed over time as binary images in the right panel.

(B–D) Quantification of mt-DS fluorescence recovery after mt-DS photostimulation in the stimulated region (B), mt-DS and mt-paGFP colocalization (C), and diffusion of mt-paGFP-positive mitochondria (D). Values represent the mt-DS fluorescence intensity in the ROI (B), the percentage of colocalization (red × green signal) in the total area corresponding to the ROI or surrounding zones (C), and the mt-paGFP-positive area as a percentage of the total area corresponding to the ROI or surrounding zones, indicating the spreading of the GFP signal (D). The dashed line indicates the time of mt-DS photostimulation.

(E) Time-lapse imaging of mt-KR before and after photostimulation (left panel, dashed square indicates photobleached area). Fluorescence recovery in the stimulated region was monitored every 10 min for 30 min. mt-paGFP was photoactivated in the same region (middle panel), and colocalization with mt-KR was assessed every 10 min for 30 min in 3 zones: the stimulated region, the zone directly surrounding the stimulated region (zone 1), and the rest of the soma (zone 2). The area of mt-paGFP fluorescence is displayed over time as binary images in the right panel.

(F–H) Quantification of fluorescence recovery after mt-KR photostimulation in the soma (in the stimulated region) (F), mt-KR and mt-paGFP colocalization (in the stimulated regions and surrounding zones) (G), and diffusion of mt-paGFP-positive mitochondria (H). Values represent the mt-KR fluorescence intensity in the ROI (F), the percentage of colocalization (red × green signal) in the total area corresponding to the ROI or surrounding zones (G), and the mt-paGFP-positive area as a percentage of the total area corresponding to the ROI or surrounding zones, indicating the spreading of the GFP signal (H). The dashed line indicates the time of mt-KR activation.

Values represent the mean ± SEM of 10–11 neurons from three independent hippocampal cultures. Two-way ANOVA (repeated measurements) and Dunnett's multiple comparison test versus T = 0 min, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. mt-KR: mito-KillerRed, mt-DS: mito-DsRed.

Figure 6.

Alterations of Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Dendrites after Focal mt-KR Activation

(A) Time-lapse imaging of mt-DS before and after photostimulation (left panel, dashed square indicates photobleached area). Fluorescence recovery in the stimulated region was monitored every 10 min for 30 min. mt-paGFP was photoactivated in the same region (middle panel), and colocalization with mt-DS was assessed every 10 min for 30 min in 3 zones: the stimulated region, the zone directly surrounding the stimulated region (zone 1), and the zone surrounding zone 1 (zone 2, inset). The area of mt-paGFP fluorescence is displayed over time as binary images in the right panel.

(B–D) Quantification of fluorescence recovery after mt-DS photostimulation in the stimulated region (B), mt-DS and mt-paGFP colocalization (in the stimulated regions and surrounding zones) (C), and diffusion of mt-paGFP-positive mitochondria (D). Values represent the mt-DS fluorescence intensity in the ROI (B), the percentage of colocalization (red × green signal) in the total area corresponding to the ROI or surrounding zones (C), and the mt-paGFP-positive area as a percentage of the total area corresponding to the ROI or surrounding zones, indicating the spreading of the GFP signal (D). The dashed line indicates the time of mt-DS photostimulation.

(E) Time-lapse imaging of mt-KR before and after photostimulation (left panel, dashed square indicates photobleached area). Fluorescence recovery in the stimulated region was monitored every 10 min for 30 min. mt-paGFP was photoactivated in the same region (middle panel), and colocalization with mt-KR was assessed every 10 min for 30 min in 3 zones: the stimulated region, the zone directly surrounding the stimulated region (zone 1), and the zone surrounding zone 1 (zone 2). The area of mt-paGFP fluorescence is displayed over time as binary images in the right panel.

(F–H) Quantification of fluorescence recovery after mt-KR photostimulation in the dendrite (in the stimulated region) (F), mt-KR and mt-paGFP colocalization (in the stimulated regions and surrounding zones) (G), and the diffusion of mt-paGFP-positive mitochondria (H). Values represent the mt-KR fluorescence intensity in the ROI (F), the percentage of colocalization (red × green signal) in the total area corresponding to the ROI or surrounding zones (G), and the mt-paGFP-positive area as a percentage of the total area corresponding to the ROI or surrounding zones, indicating the spreading of the GFP signal (H). The dashed line indicates the time of mt-KR activation.

(I) Percentage of fluorescence recovery 30 min after photostimulation in the soma or the dendrite (stimulated region).

(J) Percentage of mt-paGFP-positive area 30 min after photostimulation in the zones surrounding the stimulated region in the soma or dendrite.

(K) Percentage of colocalization between the mt-DS and mt-paGFP fluorescence signal (red × green) in the zones surrounding the stimulated region 30 min after photostimulation in the soma or the dendrite.

Values represent the mean ± SEM of 10–11 neurons/group from three independent hippocampal cultures. (B–D and F–H) Two-way ANOVA (repeated measurements) and Dunnett's multiple comparison test versus T = 0 min, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. (I–K) Values represent the mean ± SEM of 10–11 neurons/group. Student's unpaired t test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Colocalization between the mt-DS and mt-paGFP signals was significantly increased over time in the ROI and in the zones surrounding the soma (Figure 5C) and the dendrite (Figure 6C), mirrored by an increased diffusion of the mt-paGFP signal (increased percentage of mt-paGFP positive mitochondria per area) into the zones surrounding the ROI (Figures 5D and 6D). The mt-paGFP signal concomitantly decreased in the ROI, indicating mitochondrial movement from the simulated region into the surrounding zones. In contrast, these parameters were not significantly altered in mt-KR-stimulated neurons, in either the soma (Figures 5G and 5H) or the dendrite (Figures 6G and 6H), suggesting impaired mitochondrial fusion in the damaged region. Of note, our mt-KR stimulation paradigm of 20 scans was not sufficient to totally bleach the mt-KR signal, unlike that of mt-DS (Figures 5G and 6G). This technical limitation therefore makes it difficult to interpret the data obtained for the photostimulated area, as the percentage of colocalization between the mt-KR and the mt-paGFP signal in the ROI remained constant over time.

Nevertheless, there was a clear difference between mt-DS- and mt-KR-stimulated neurons, when the fluorescence recovery, the percentage mt-paGFP-positive area, and the colocalization (red × green) were compared between 0 and 30 min post-stimulation in the soma and dendrite (Figures 6I–6K). A significant reduction in these three parameters was observed in the mt-KR- versus mt-DS-stimulated cells, which may reflect (1) decreased mitochondrial transport back to the damaged ROI (Figure 6I), (2) decreased transport of damaged mitochondria outside the ROI (Figure 6J), and (3) decreased fusion rate of damaged mitochondria in the ROI, with healthy ones remaining around the ROI (Figure 6K) (see also Twig et al., 2008, Wang et al., 2012).

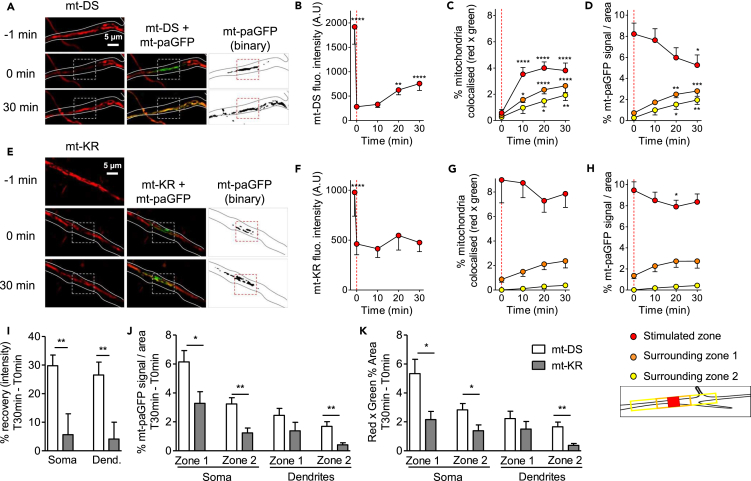

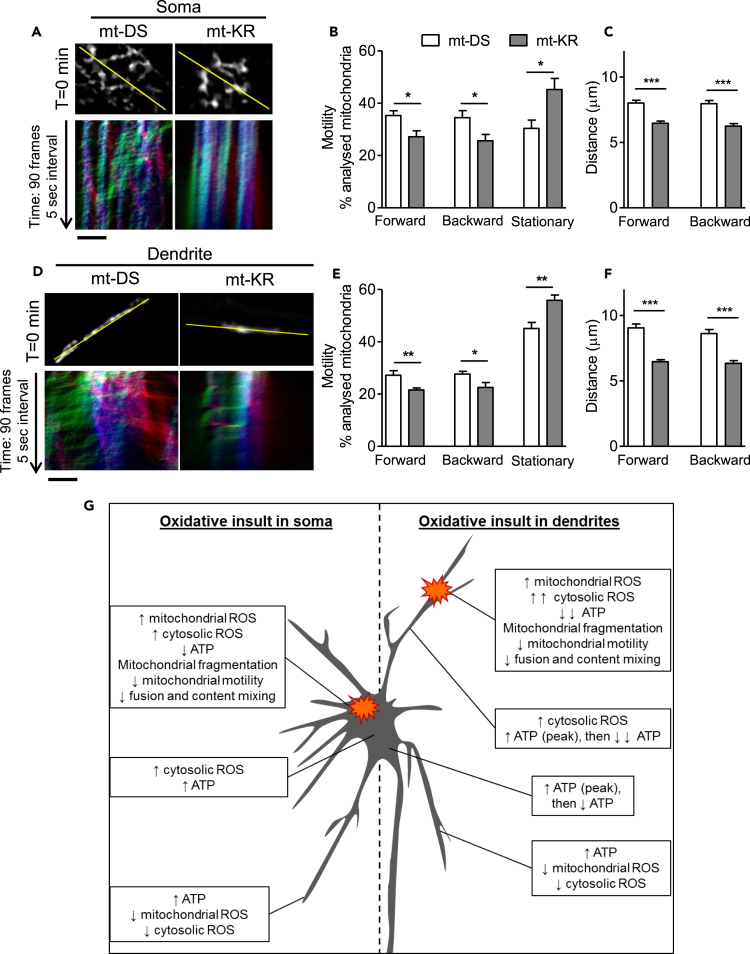

In addition, analysis of the motility of mt-paGFP-positive mitochondria revealed a reduction in the proportion of mitochondria moving forward and backward in the soma (Figures 7A and 7B) and the dendrite (Figures 7D and 7E) of mt-KR-stimulated neurons when compared with mt-DS-stimulated cells. Also, the proportion of stationary mitochondria was significantly increased in both compartments (mt-KR versus mt-DS: +15% in the soma and +10% in the dendrite, Figures 7B and 7E, respectively). The average distance traveled by mobile mitochondria (moving forward and backward) was significantly reduced in the soma (Figure 7C) and the dendrite (Figure 7F) of mt-KR-stimulated neurons when compared with mt-DS-stimulated cells.

Figure 7.

Decreased Mitochondrial Motility at the Site of Insult after Focal mt-KR Activation, and Proposed Model

(A) Top panel: mt-paGFP fluorescence signal in the soma in the first frame of the time-lapse recording (T = 0 min, total 90 frames, 0.5-s interval). The yellow lines demarcate the selections used to generate kymographs. Lower panel: Representative kymographs (mt-paGFP fluorescence signal) showing the relative mitochondrial motility in the soma after mt-paGFP activation. The blue vertical lines represent stationary mitochondria, the green oblique lines indicate mitochondria moving forward, and the red oblique lines indicate mitochondria moving backward. Scale bar represents 5 μm.

(B) Analysis of mitochondrial motility by direction of movement (forward, backward, and stationary) in the soma. Values represent the mean ± SEM of the proportion of mobile and immobile mitochondria per total number of analyzed mitochondria per kymograph. N = 10–11 cells/group from three independent hippocampal cultures.

(C) Analysis of the distance traveled by mobile mitochondria in the soma. On average 150–200 mitochondria were analyzed per group (n = 10–11 neurons/group from 3 independent hippocampal cultures).

(D) Top panel: mt-paGFP fluorescence signal in the dendrite in the first frame of the time-lapse recording (T = 0 min, total 90 frames, 0.5-s interval). The yellow lines show the selections used to generate kymographs. Lower panel: Representative kymographs (mt-paGFP fluorescence signal) showing relative mitochondrial motility in the dendrite after mt-paGFP activation. Blue vertical lines represent stationary mitochondria, the green oblique lines indicate mitochondria moving forward (toward distal dendrites), and the red oblique lines indicate mitochondria moving backward (back to the soma). Scale bar represents 5 μm.

(E) Analysis of mitochondrial motility by direction of movement (forward, backward, and stationary) in the dendrite. Values represent the mean ± SEM of the proportion of mobile and immobile mitochondria per total number of analyzed mitochondria per kymograph. N = 10–11 cells/group from 3 independent hippocampal cultures.

(F) Analysis of the distance traveled by mobile mitochondria in the dendrite. On average 150–200 mitochondria were analyzed per group (n = 10–11 neurons/group from 3 independent hippocampal cultures).

(B, C, E, and F) Values represent the mean ± SEM Student's paired t test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

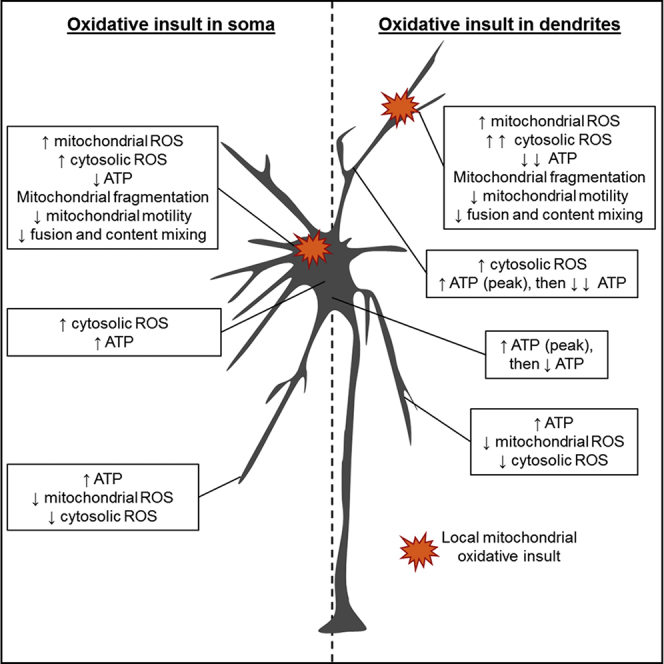

(G) Proposed model of the somatodendritic regulation of redox state and ATP turnover after an acute local oxidative insults. When an oxidative damage occurs within somatic mitochondria (left panel), ROS increase only in the photostimulated mitochondria and the ATP/ADP ratio decreases. Cytosolic ROS levels increase in the damaged region as well as in the remainder of the soma. Impaired mitochondria are fragmented and have a decreased motility and a reduced ability to fuse with other mitochondria. In the soma and dendrites, the ATP/ADP ratio increases, whereas mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS decrease in the distal dendrites. Similarly, when oxidative damage occurs within dendritic mitochondria (right panel), ROS increase only in the photostimulated mitochondria. The ATP/ADP ratio decreases and cytosolic ROS increase in the damaged region to a greater extent than in the soma under similar conditions. Again, impaired mitochondria are fragmented and have a decreased motility and a reduced ability to fuse with other mitochondria. In the rest of the affected dendrite, the ATP/ADP ratio increases and then strongly decreases over time. In the non-damaged dendrites, mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS decrease, with a concomitant increase in the ATP/ADP ratio. Thus, neurons avoid the spread of oxidation by quarantining damaged mitochondria at the site of insult.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that damaged mitochondria have a reduced motility and fusion rate, which may prevent the spreading of the oxidative insult beyond the zone of damage.

Discussion

Given the high energy needs of neurons, it is essential for them to maintain mitochondrial function after a local insult. Considering that most studies address the whole-cell response of neurons to an oxidative insult, we addressed the following two questions in our study: (1) is it possible to monitor changes in redox homeostasis and ATP turnover in neurons after an acute mitochondrial oxidative insult and (2) are there compartment-specific differences in how neurons cope with local mitochondrial stress.

The main findings of our study are as follows: (1) The basal mito- and cyto-redox states in distal dendrites are more oxidized and ATP levels are lower than those in the soma and proximal dendrites. (2) When an oxidative insult occurs locally in the soma or dendrite, mitochondrial oxidation increases and ATP levels decrease only in the damaged region, whereas the ATP/ADP ratio increases in the distal regions. (3) Oxidatively stressed mitochondria are fragmented and have a decreased motility and a reduced fusion rate. (4) The soma and dendrites respond in the same way to a focal oxidative insult; however, dendrites seem to be more sensitive to oxidative stress, with a higher increase in cytosolic oxidation and decreased ATP levels observed in the damaged region (Figure 7G).

Whole-cell mt-KR stimulation triggered mitochondrial and cytosolic oxidation, coupled with a decrease in ATP levels and fragmentation of the mitochondrial network. As neurons rely almost exclusively on mitochondrial respiration to synthesize ATP molecules (Harris et al., 2012), it is likely that the decrease in ATP levels observed after mt-KR-induced oxidative stress is due to the inhibitory effects of ROS on mitochondrial respiration and subsequent ATP production (reviewed in Grimm and Eckert, 2017). Indeed, when produced in excess, mROS may damage proteins and DNA, and induce lipid peroxidation, with the corresponding mitochondrial structures, including the respiratory chain that produces ATP molecules, being the first target of toxicity. For example, Brown and Borutaite previously showed that some ROS species inhibit mitochondrial complex IV activity by competitively binding to its oxygen site (Brown and Borutaite, 2002). Thus, the direct inhibitory effect of mROS on the mitochondrial respiration, combined with the rapid utilization of ATP molecules within neurons, may explain the rapid depletion of cellular ATP that we observed after mt-KR stimulation.

The progressive cytosolic oxidation may be explained by the diffusion of the mt-KR-derived ROS from the mitochondrial matrix to the cytosol, given that mROS, including superoxide, can pass through the mitochondrial membrane via voltage-dependent anion channels (Tafani et al., 2016). It is also possible that the mROS overload induces the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, releasing mROS into the cytosol (Rottenberg and Hoek, 2017, Zorov et al., 2014). Besides, it cannot be excluded that mROS induce the formation of cytosolic ROS via a vicious circle of oxidative stress (Grimm and Eckert, 2017, Grimm et al., 2016), which may explain why oxidation continued to increase for 30 min after mt-KR stimulation.

A major focus of our study was to investigate the impact of a local oxidative insult in the soma and dendrites. We found that mitochondrial oxidation was immediately increased after the insult but only in the stimulated region. However, we also observed a slow cytosolic oxidation, again suggesting that ROS produced in the mitochondria by mt-KR stimulation were “leaking” into the cytosol. Interestingly, the ATP/ADP ratio decreased in the photostimulated regions, but increased in the neighboring compartments, particularly distal dendrites. Indeed, after mt-KR stimulation in the soma or dendrite, the ATP/ADP ratio presented an initial sharp rise followed by a slower increase in non-stimulated regions (see also Figure 7G). This may reflect a compensatory mechanism developed by neurons to prevent a local oxidative stress affecting the remainder of the neuron. We may speculate that neurons upregulate their antioxidant defenses in response to an oxidative insult, leading to an increase in mitochondrial respiration and ATP production, coupled with a decrease in oxidation. In line with this concept, a recent study has highlighted the role of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) as a potential regulator of the cellular metabolic balance in response to increased mROS (Rabinovitch et al., 2017). The study showed that mROS can activate AMPK, promoting a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha-dependent antioxidant response program that regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and cellular metabolic balance. Another explanation may be provided by the close interconnection between the ER and mitochondria via the mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) (Paillusson et al., 2016). It is known that an increase in mROS affects the ER, leading to an increased release of Ca2+ (reviewed in Gorlach et al., 2015). Thus, the fast increase in the ATP/ADP ratio that we observed outside the stimulated region may be due to calcium transfer to mitochondria via the MAMs, thereby stimulating ATP synthesis (Bravo et al., 2011, Griffiths and Rutter, 2009). Further experiments are required to determine which pathway is involved (e.g., AMPK or MAM-dependent Ca2+ signaling pathway).

mt-KR-stimulated dendrites exhibited a greater increase in cytosolic oxidation and a more pronounced decrease in ATP levels in the damaged region when compared with the soma. This may correlate with the basal redox state and ATP/ADP ratio, as we showed that the mito- and cyto-redox states were more oxidized in the distal dendrites than the soma, together with a lower ATP/ADP ratio. These findings are in line with previous evidence showing higher peroxide production in synaptic compared with non-synaptic mitochondria (reviewed in Grimm and Eckert, 2017). Similarly, synaptic mitochondria were shown to express lower levels of manganese superoxide dismutase compared with non-synaptic mitochondria, which supports the high sensitivity of synapses to oxidative stress (Volgyi et al., 2015). Interestingly, at physiological concentrations, ROS play a role in different processes including cellular signaling and learning and memory (Kishida and Klann, 2007, Veal et al., 2007). Physiological levels of ROS are important for the regulation of synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation (LTP). Indeed, inhibiting ROS production or reducing superoxide levels through scavenging mechanisms resulted in deficient LTP in healthy mice (reviewed in Massaad and Klann, 2011). Therefore, it is conceivable to assume that the higher oxidation we observed in dendrites may serve neuronal functions by regulating synaptic plasticity.

Synaptic mitochondria need to sustain the high energy level required for synaptic activity, with a recent report detailing the amount of ATP that is required for synaptic transmission (Harris et al., 2012). ATP is mainly used by several ATPases to re-establish the ion balance after the firing of an action potential, to lower intracellular calcium levels, to energize vesicle transmitter uptake, and to allow mitochondrial transport by motor proteins. Specifically, in dendrites, half of the total ATP is required, mainly for the reversal of ion flux through post-synaptic receptors (Harris et al., 2012). Therefore, the higher oxidation observed by us in dendrites may be due to higher ROS production and lower antioxidant defenses in synaptic mitochondria. In addition, the high ATP requirements in the post-synaptic compartment may explain the lower ATP/ADP ratio observed in dendrites compared with the soma, as the available ATP is rapidly used to sustain synaptic activity.

As far as mitochondrial mobility and dynamics after a local oxidative insult are concerned, we did not observe any differences between the soma and dendrites. Following focal mt-KR stimulation, a local mitochondrial fragmentation was observed. In addition, impaired mitochondria were found to have a decreased motility as well as a reduced fusion rate. In line, previous studies showed that mt-KR photostimulation induced mitochondrial depolarization (Wang et al., 2012), which may prevent mitochondrial fusion (Twig et al., 2008). Using focal mt-KR stimulation in axonal mitochondria, Ashrafi and colleagues reported local mitochondrial fragmentation and the PINK1/Parkin-dependent elimination of damaged mitochondria (Ashrafi et al., 2014). This group also showed that PINK1 phosphorylates Miro, a protein that is involved in anchoring kinesin to the mitochondrial surface, leading to Parkin-dependent degradation of Miro, detachment of kinesin from the mitochondria, and the arrest of mitochondrial transport before their clearance (Wang et al., 2011). As we also observed local mitochondrial fragmentation in mt-KR-stimulated mitochondria coupled with a decrease in mitochondrial movement and fusion, it is possible that similar mechanisms might occur in the soma and dendrites to eliminate damaged mitochondria by mitophagy (Cummins and Götz, 2017). Neuronal mitophagy in the somatodendritic compartment has been shown (using the ionophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP)) to require hours of mitochondrial depolarization (Cai et al., 2012), and is therefore likely to occur outside the time window investigated in the present study. Future work will determine the long-term effects of acute mt-KR stimulation on somatodendritic redox homeostasis and ATP turnover. In this regard, it is worth noting that continuous mt-KR irradiation of distal dendrites for up to 15 min induced local spine elimination (caspase-3 dependent), although no cell death was detected even 9 hr post-stimulation (Ertürk et al., 2014).

Taken together, our findings expand the current knowledge about the somatodendritic regulation of redox homeostasis, ATP turnover, and mitochondrial dynamics after a local oxidative insult in neurons. Given that neurons are compartmentalized cells with high energy demands and with a lifespan similar to that of the whole organism, they need an efficient system to maintain their redox balance and ATP levels in response to oxidative insults. By combining the photosensitizer mt-KR, fluorescent biosensors, and photoactivatable GFP, we showed that neurons are able to contain a local oxidative stress in the soma or dendrite, limiting the increase in ROS and the decrease in ATP production to the damaged area. The cells therefore avoid the spreading of oxidation by “quarantining” mitochondria. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and bioenergetic deficits are hallmarks of brain aging, as well as of numerous neurodegenerative disorders (Damiano et al., 2010, Grimm and Eckert, 2017, Grimm et al., 2016, Pickrell and Youle, 2015), and understanding how neuronal redox homeostasis and bioenergetics are regulated under physiological conditions will likely also have implications for the treatment of these conditions.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tishila Palliyaguru for general laboratory coordination; Rumelo Amor for training, microscopy assistance, and technical advice; and Rowan Tweedale for critically reading the manuscript. This study was supported by the Estate of Dr. Clem Jones AO, as well as grants from the Australian Research Council (ARC) [DP160103812], the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia [GNT1037746, GNT1127999], the State Government of Queensland (DSITI, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation), and the Swiss National Foundation [P2BSP3_172045]. Confocal microscopy was facilitated by the Queensland Brain Institute's Advanced Microscopy Facility, supported by the ARC LIEF Grant (LE130100078).

Author Contributions

A.G., N.C., and J.G. conceived and designed the experiments; A.G. and N.C. performed the experiments; A.G. performed the data analysis; and A.G., N.C., and J.G. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Published: August 31, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Transparent Methods, two figures, and two tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2018.07.015.

Supplemental Information

References

- Ashrafi G., Schlehe J.S., Lavoie M.J., Schwarz T.L. Mitophagy of damaged mitochondria occurs locally in distal neuronal axons and requires PINK1 and Parkin. J. Cell Biol. 2014;206:655–670. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J., Hung Y.P., Yellen G. A genetically encoded fluorescent reporter of ATP: ADP ratio. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:161–166. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo R., Vicencio J.M., Parra V., Troncoso R., Munoz J.P., Bui M., Quiroga C., Rodriguez A.E., Verdejo H.E., Ferreira J. Increased ER-mitochondrial coupling promotes mitochondrial respiration and bioenergetics during early phases of ER stress. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:2143–2152. doi: 10.1242/jcs.080762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G.C., Borutaite V. Nitric oxide inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and its role in cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;33:1440–1450. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulina M.E., Chudakov D.M., Britanova O.V., Yanushevich Y.G., Staroverov D.B., Chepurnykh T.V., Merzlyak E.M., Shkrob M.A., Lukyanov S., Lukyanov K.A. A genetically encoded photosensitizer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nbt1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q., Zakaria H.M., Simone A., Sheng Z.H. Spatial parkin translocation and degradation of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy in live cortical neurons. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins N., Götz J. Shedding light on mitophagy in neurons: what is the evidence for PINK1/Parkin mitophagy in vivo? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017;75:1151–1162. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2692-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiano M., Galvan L., Déglon N., Brouillet E. Mitochondria in Huntington's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1802:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertürk A., Wang Y., Sheng M. Local pruning of dendrites and spines by caspase-3-dependent and proteasome-limited mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:1672–1688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3121-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flippo K.H., Strack S. Mitochondrial dynamics in neuronal injury, development and plasticity. J. Cell Sci. 2017;130:671–681. doi: 10.1242/jcs.171017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach A., Bertram K., Hudecova S., Krizanova O. Calcium and ROS: a mutual interplay. Redox Biol. 2015;6:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths E.J., Rutter G.A. Mitochondrial calcium as a key regulator of mitochondrial ATP production in mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:1324–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm A., Eckert A. Brain aging and neurodegeneration: from a mitochondrial point of view. J. Neurochem. 2017;143:418–431. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm A., Friedland K., Eckert A. Mitochondrial dysfunction: the missing link between aging and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Biogerontology. 2016;17:281–296. doi: 10.1007/s10522-015-9618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J.J., Jolivet R., Attwell D. Synaptic energy use and supply. Neuron. 2012;75:762–777. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C.H., Cheng S.S., Cheung Y.T., Wuwongse S., Zhang N.Q., Ho Y.S., Lee S.M., Chang R.C. A reciprocal relationship between reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial dynamics in neurodegeneration. Redox Biol. 2018;14:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowski M., Arnoult D., Chen H., Chan D.C., Smith C.L., Youle R.J. Quantitation of mitochondrial dynamics by photolabeling of individual organelles shows that mitochondrial fusion is blocked during the Bax activation phase of apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2004;164:493–499. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida K.T., Klann E. Sources and targets of reactive oxygen species in synaptic plasticity and memory. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007;9:233–244. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.ft-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejri I., Grimm A., Miesch M., Geoffroy P., Eckert A., Mensah-Nyagan A.G. Allopregnanolone and its analog BR 297 rescue neuronal cells from oxidative stress-induced death through bioenergetic improvement. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017;1863:631–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuner K., Schutt T., Kurz C., Eckert S.H., Schiller C., Occhipinti A., Mai S., Jendrach M., Eckert G.P., Kruse S.E. Mitochondrion-derived reactive oxygen species lead to enhanced amyloid beta formation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;16:1421–1433. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaad C.A., Klann E. Reactive oxygen species in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and memory. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;14:2013–2054. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill R.A., Flippo K.H., Strack S. Measuring mitochondrial shape with ImageJ. Neuromethods. 2017;123:31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Misgeld T., Schwarz T.L. Mitostasis in neurons: maintaining mitochondria in an extended cellular architecture. Neuron. 2017;96:651–666. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillusson S., Stoica R., Gomez-Suaga P., Lau D.H., Mueller S., Miller T., Miller C.C. There's something wrong with my MAM; the ER-mitochondria axis and neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell A.M., Youle R.J. The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2015;85:257–273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitch R.C., Samborska B., Faubert B., Ma E.H., Gravel S.P., Andrzejewski S., Raissi T.C., Pause A., St-Pierre J., Jones R.G. AMPK maintains cellular metabolic homeostasis through regulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell Rep. 2017;21:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg H., Hoek J.B. The path from mitochondrial ROS to aging runs through the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Aging Cell. 2017;16:943–955. doi: 10.1111/acel.12650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmuck G., Rohrdanz E., Tran-Thi Q.H., Kahl R., Schluter G. Oxidative stress in rat cortical neurons and astrocytes induced by paraquat in vitro. Neurotox. Res. 2002;4:1–13. doi: 10.1080/10298420290007574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockburger C., Gold V.A., Pallas T., Kolesova N., Miano D., Leuner K., Muller W.E. A cell model for the initial phase of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:395–411. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafani M., Sansone L., Limana F., Arcangeli T., De Santis E., Polese M., Fini M., Russo M.A. The interplay of reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, inflammation, and sirtuins in cancer initiation and progression. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016;2016:3907147. doi: 10.1155/2016/3907147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twig G., Elorza A., Molina A.J., Mohamed H., Wikstrom J.D., Walzer G., Stiles L., Haigh S.E., Katz S., Las G. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:433–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veal E.A., Day A.M., Morgan B.A. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volgyi K., Gulyassy P., Haden K., Kis V., Badics K., Kekesi K.A., Simor A., Gyorffy B., Toth E.A., Lubec G. Synaptic mitochondria: a brain mitochondria cluster with a specific proteome. J. Proteomics. 2015;120:142–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Winter D., Ashrafi G., Schlehe J., Wong Y.L., Selkoe D., Rice S., Steen J., Lavoie M.J., Schwarz T.L. PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2011;147:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Nartiss Y., Steipe B., Mcquibban G.A., Kim P.K. ROS-induced mitochondrial depolarization initiates PARK2/PARKIN-dependent mitochondrial degradation by autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:1462–1476. doi: 10.4161/auto.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waypa G.B., Marks J.D., Guzy R., Mungai P.T., Schriewer J., Dokic D., Schumacker P.T. Hypoxia triggers subcellular compartmental redox signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2010;106:526–535. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.C., Bejjani R.E., Ramirez P.M., Coakley S., Kim S.A., Lee H., Wen Q., Samuel A., Lu H., Hilliard M.A. Rapid and permanent neuronal inactivation in vivo via subcellular generation of reactive oxygen with the use of KillerRed. Cell Rep. 2013;5:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.Y., Yang W.Y. Spatiotemporally controlled initiation of Parkin-mediated mitophagy within single cells. Autophagy. 2011;7:1230–1238. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorov D.B., Juhaszova M., Sollott S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol. Rev. 2014;94:909–950. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.