Abstract

Most low-income Americans fail to meet physical activity recommendations. Inactivity and poor diet contribute to obesity, a risk factor for multiple chronic diseases. Health promotion activities have the potential to improve health outcomes for low-income populations. Measuring the effectiveness of these activities, however, can be challenging in community settings. A “Biking for Health” study tested the impact of a bicycling intervention on overweight or obese low-income Latino and African American adults to reduce barriers to cycling and increase physical activity and fitness. A randomized controlled trial was conducted in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in summer 2015. A 12-week bicycling intervention was implemented at two sites with low-income, overweight, or obese Latino and African American adults. We found that randomized controlled trial methodology was suboptimal for use in this small pilot study and that it negatively affected participation. More discussion is needed about the effectiveness of using traditional research methods in community settings to assess the effectiveness of health promotion interventions. Modifications or alternative methods may yield better results. The aim of this article is to discuss the effectiveness and feasibility of using traditional research methods to assess health promotion interventions in community-based settings.

Keywords: Black/African American, Latino, obesity, physical activity/exercise, program planning, evaluation

➢ INTRODUCTION

In 2006, the National Institutes of Health launched the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program. Since its inception, the National Institutes of Health has funded more than 50 CTSA centers at academic institutions and medical centers throughout the United States (National Center for Advancing Translational Science, n.d.). These CTSA centers have worked to translate research and knowledge not only from “bench-to-bedside” but also to clinical practice, and to health promotion in the larger community. CTSA funds the Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) of southeastern Wisconsin, which is a consortium of three universities, a large children’s hospital, a Veteran’s Administration hospital, a statewide blood research institute, and a medical school. According to its administrators, CTSI has struggled to connect with the communities that it serves. To this end, CTSI (n.d.) has redesigned its grant-funding processes to encourage community-based research projects.

While CTSI guidelines indicate it is open to communitybased research projects, the structures that review and oversee projects remain influenced by medical research methods, tools, and protocols. This article will discuss the relevance and limitations of traditional research methods used in a community-based participatory research health promotion intervention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Lessons learned might advance future translational science research to improve community health.

➢ BACKGROUND

Nationally, obesity rates among Latinos and African Americans are high and contribute to chronic health conditions in both populations (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2014). Mirroring national trends, obesity rates are high for Latinos and African Americans in Milwaukee (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2016). Located in southeastern Wisconsin, Milwaukee is Wisconsin’s largest city and its commercial and industrial center. Milwaukee’s Latino population is clustered around Milwaukee’s south side, while the African American population is clustered around the central city and the north side.

Evidence suggests that physical activity, including bicycling, can promote health in many ways (Hamer & Chida, 2008), yet most Americans do not engage in recommended amounts of physical activity (Haskell et al., 2007). In addition, disparities exist between the prevalence of inactivity in lower socioeconomic and higher socioeconomic communities (Crespo, Smit, Andersen, Carter-Pokras, & Ainsworth, 2000).

To decrease barriers to bicycling and improve physical activity, a pilot study, “Biking for Health,” delivered a 12-week bicycling intervention for adults in two Milwaukee low-income neighborhoods. One group of participants was recruited from the city’s predominantly Latino community surrounding the Sixteenth Street Community Health Center, a Federally Qualified Health Center that has served neighborhood residents for over 45 years. A second group was recruited from the city’s Westlawn neighborhood, which is primarily African American and is anchored by the Silver Spring Neighborhood Center, a nonprofit social service agency that serves the surrounding community.

Partners on the study team included a health coordinator and two community health workers from the Sixteenth Street Community Health Center, a community health worker from the Silver Spring Neighborhood Center, three staff from the Bike Federation of Wisconsin, three researchers from the Medical College of Wisconsin, and three researchers from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. Community health workers assisted with recruitment, and two Bike Federation of Wisconsin staff implemented the intervention. All other team members assisted with recruitment, data collection, intervention planning, and analysis.

The overall goal of the study was to learn about barriers to bicycling and to assess the efficacy of a bicycling intervention in inactive, low-income, Latino and African American, overweight, or obese adults. The transtheoretical model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1986) and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) informed our study, which sought to assess whether a 12-week bicycling intervention would result in reduced barriers to bicycling, leading to increased physical activity and improved physical fitness, and to determine the short- and intermediate-term health impacts of the bicycling intervention. The objective of this article is to discuss the lessons learned from applying traditional medical research methods in a communityengaged study.

➢ METHOD

The study took place from May through October 2015. The research team conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) at two sites: the Latino neighborhood around the Sixteenth Street Community Health Center and the African American neighborhood around the Silver Spring Neighborhood Center. RCT methodology was used for several reasons: (a) we were unaware of any studies that have used an RCT to evaluate a bicycling education and promotion intervention, using survey and biometric data; (b) RCT methodology could provide robust findings with which to evaluate this health promotion activity; and (c) it made our CTSI proposal competitive for funding to conduct the study.

To recruit study participants, the team posted recruitment flyers at local community-based clinics and organizations, conducted outreach at community events, and made phone calls to potential participants based on past indications of interest in bicycling. Those who were interested completed a consent form, provided demographic information, and were screened for study eligibility. The study team emphasized to enrollees during the consent process that this study would include both a bicycling intervention group and a comparison group. Potential participants were screened for eligibility criteria, including physical inactivity, defined by self-reporting less than 20 minutes of physical activity three times per week. In addition, height and weight were measured; participants with body mass index <25 were excluded. Participants were also screened for safety to participate in moderate physical activity using the validated Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (Thomas, Reading, & Shephard, 1992). Outcome data were collected from all participants at baseline, at 12 weeks after the bicycling intervention was completed, and at 20 weeks to determine if there were residual impacts from the intervention. Data collected at each point included responses from a biking attitudes survey; self-reported physical activity using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ); and assessment of physical fitness using the 6-Minute Step Test (Arcuri et al., 2016), weight, blood pressure, and waist circumference.

The Bicycling & Attitude Questionnaire included 19 potential barriers to bicycling (see Figure 1). Participants were asked to rate the significance of each barrier, and participants recorded their own answers. The survey was developed based on literature related to bicycling barriers and relevant survey instruments (Dill & Voros, 2007; Emond & Handy, 2012; Engbers & Hendriksen, 2010; Schneider & Hu, 2015). The survey was pilot tested and further revised based on feedback from community liaisons and university students. The language was also modified to accommodate low literacy levels. Qualitative data about attitudes toward bicycling were also captured in field notes by the ride leaders and in the additional open-ended comments provided by participants on the Bicycling & Attitude Questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Bicycling & Attitude Questionnaire: Perceived Barriers Questions

The IPAQ (Craig et al., 2003) was used to assess how much physical activity participants engaged in. Language on the IPAQ was modified to accommodate low literacy levels. The study team asked participants the questions and wrote down their answers.

Forty-nine eligible adults enrolled in the study between both sites and were randomly assigned to an intervention or control group. Of these, 38 actively participated at the beginning of the study, with 21 in the intervention group and 17 in the control group (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | Intervention Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Latino | 13 | 4 |

| African American | 8 | 13 |

| Annual household income, $ | ||

| <15,000 | 5 | 13 |

| 15,000–34,000 | 6 | 2 |

| >34,000 | 7 | 1 |

| Unreported | 3 | 1 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 18 | 14 |

| Male | 3 | 3 |

| Total participants | 21 | 17 |

Incentives included a refurbished bicycle, helmet, and bike lock for intervention group participants, which were theirs to keep on study completion, and gift cards for control group participants, which they received at baseline, 12-week, and 20-week data collection points. Intervention group members also received gift cards at 12-week and 20-week data collection points, and control group members also received bicycles, helmets, and bike locks at the conclusion of the study.

All recruitment and research study materials were translated into Spanish and were available in Spanish and English in the Sixteenth Street Community Health Center community. In addition, Spanish-speaking project team members from the Sixteenth Street Community Health Center assisted with phone calls and outreach to potential participants and were available to assist with translation on data collection dates, and a bilingual ride leader from the Bike Federation of Wisconsin led the weekly intervention group bike rides in the health center community. The two intervention groups met approximately weekly. Two sessions were used for bicycle fittings and bicycling instruction; the remaining 10 weeks consisted of group rides, led by Bike Federation of Wisconsin biking instructors. The study was approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board (IRB).

➢ RESULT

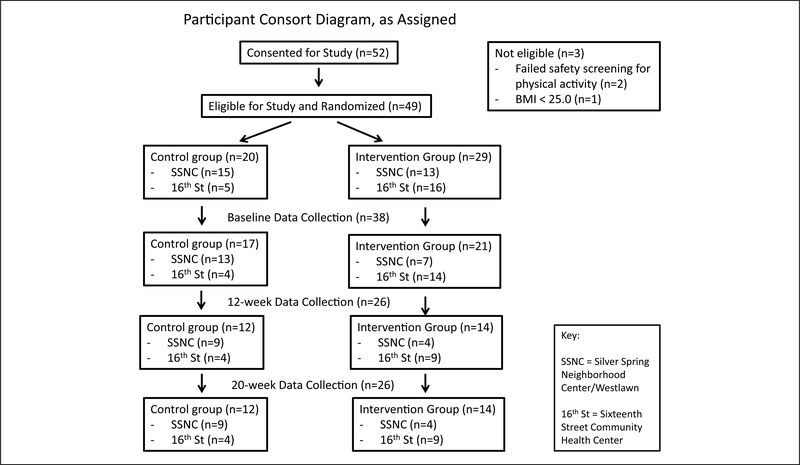

Data were collected from 38 participants at baseline. Due to attrition, 26 participants provided followup data at 12-weeks, and again at 20-weeks. Data were analyzed using t tests, chi-square Fischer exact testing, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and analysis of variance as appropriate. The Figure 2 Consort Flow Diagram shows how many participants were involved from each site and in which group.

Figure 2.

Participant Consort Diagram

The biking attitudes survey found at 20 weeks that there were significant decreases in perceived barriers for the intervention group compared to the control group: not feeling healthy enough to bike (p = .049), not feeling safe from crime (p = .012), and not feeling safe from car traffic (p = .002). Qualitative data analysis of field notes collected during rides and of notes collected during administration of the biking attitudes survey found two common themes among all participants as reasons to bicycle and increase their physical activity: (a) More than three quarters mentioned that family and social support was important and (b) more than half cited personal health reasons as important. A thorough compilation and discussion of the biking attitudes survey results and qualitative data analysis are available elsewhere (see Schneider, Kusch, Dressel, & Bernstein, 2016).

Results from the IPAQ indicated a significant increase in self-reported bicycling for the intervention group at 20 weeks. Participants in the intervention group reported more time spent “bicycling for transport” compared to the control group (mean difference +23.1 minutes/day, 95% confidence interval [+3.5, +42.7]). However, there were no significant differences in fitness and biometrics between and within both groups at baseline, 12 weeks, and 20 weeks.

Comprehensive study results are available elsewhere (see Bernstein et al., 2016).

➢ DISCUSSION

The bicycling education and promotion intervention significantly decreased several perceived barriers to bicycling for the intervention group, including not feeling healthy enough to bike, not feeling safe from crime, and not feeling safe from car traffic. In addition, intervention group members reportedly spent more time engaged in “bicycling for transport” at 20 weeks. While these findings are encouraging, they did not result in a significant increase in health and physical fitness for the intervention group.

The study did raise important questions, however, about how well health promotion assessment and evaluation processes, research tools, protocols, and methods work in a community setting, which is the focus of this discussion. The most successful tools were the bicycle attitudes survey and the 6-Minute Step Test. The bicycle attitudes survey yielded important findings about perceived barriers to bicycling in each community and indicated that several barriers decreased significantly among participants in the intervention group. The 6-Minute Step test was found to be convenient to conduct and acceptable to participants. The wooden step was portable, allowing study team members to move it between the two data collection sites, and the test was easy for participants to understand and execute.

Much has been written about the importance of community partners in successful community-based research studies (Sadler et al., 2012). Community partners were key in this study as well for reasons that have already been well documented. Team members from the partnering organizations knew the community residents, which aided in recruitment. These community partners also called participants to remind them about scheduled rides and about data collection dates. Participants knew and trusted the community partners. Spanish-speaking study staff and recruitment materials were necessary in the Latino community, since some participants spoke only Spanish, and it helped the study get more community buy-in from study participants. As one participant stated, “Seeing the recruitment materials in Spanish made me feel like this really was a program for our community.” Related to this issue, however, the team did not adequately plan for translation costs in the grant budget, an important consideration for projects in multiethnic communities.

In several ways, the requirements of the IRB— designed for higher risk medical research trials—were ill suited to a low-risk community health promotion intervention. The literature has discussed successful recruitment strategies for minority communities (Horowitz, Brenner, Lachapelle, Amara, & Arniella, 2009). We found, however, that the IRB-approved recruitment flyer for our Biking for Health study was uninviting, was ineffective, and contained too much text. In addition, the IRB-approved consent form was intimidating, long, and difficult for participants to understand. Likewise, the requirement to reconsent participants in order to use a budget surplus to give out modest retention incentives to the control group was received as silly and unnecessary to participants.

The IRB constrained the program to use of a preexisting consent form template that, despite being specifically written for low-risk community-engaged projects, was nevertheless found to be long and relatively complicated. A draft recruitment flyer referring to the research study as “fun” and referring to the bicycling intervention that only some participants would be involved with was felt to be coercive and inaccurate, so it was revised to meet compliance for IRB approval. Of note, after completion of the project, the institution’s IRB began work to significantly change its approach to low-risk community-engaged research based on a participatory process involving both community-engaged academic researchers and community members. This process is currently under way.

Developing a convenient IRB-approved consent process for communities has been discussed in the literature (Reidy, Orpinas, & Davis, 2012); however, translating suggested solutions into accepted IRBapproved protocols is lacking. If academic institutions want to be more involved in community research and systematic assessment of health promotion interventions, openness to modifying documentation requirements for low-risk interventions and residents of all education levels would be good first steps.

Related to recruitment, only six men enrolled in this study across both sites. One possible explanation is that community recruiters were neighborhood women. For example, one academic researcher observed that the recruiter in Westlawn was more comfortable approaching other women. In addition, women tend to be more involved in the community (Jenkins, 2005), so they were more likely to be at community meetings and events where recruitment occurred. This was not necessarily a negative outcome since women often make decisions for the health and well-being of their families (U.S. Department of Labor, 2013). In addition, mothers could model healthy behavior for their children, and if a mother participates in the study and becomes comfortable bicycling, she may encourage her children to ride as well. African American and Latino women are also an important group to reach since they have the lowest rates of bike ridership of any groups in the country (League of American Bicyclists, 2013). However, this gender discrepancy was not anticipated sufficiently and made it difficult to find enough bicycles of the correct size and type for all participants. For example, many female participants wanted a wide, comfortable bike seat, which the study team was not always able to provide. In addition, this sampling, which included more women than men, introduced significant limitations in the generalizability of our findings since the study participants did not reflect the wider gender demographics of each community.

The need for child care during the bike rides and data collection was also an issue. We were able to provide child care at only one site, potentially affecting participant recruitment and engagement. Including child care in the budget and study plan should be considered in future studies.

Other research tools that have been validated for controlled studies did not work well for our study populations. For example, we found that the IPAQ did not provide reliable estimates of physical activity for our participants. All participants confirmed during enrollment that they currently exercised less than 60 minutes per week. However, they reported, using the baseline IPAQ, an average of 270.5 minutes per day of vigorous physical activity and 467 minutes per day of moderate-intensity physical activity. The data of 18 participants had to be excluded based on standard scoring procedures because they reported >960 minutes per day of activity. The IPAQ was difficult for study participants to understand, as participants had to differentiate between concepts such as “vigorous” and “moderate” activity. Even with language-appropriate versions and interviewer administration, low education and literacy levels led to difficulties with comprehension.

Finally, the RCT design was suboptimal in our community settings. Often touted as the “gold standard” for research (grossman & Mackenzie, 2005), using the RCT was a way to ensure that the Biking for Health study would be competitive for CTSI funding. Lessons learned from this study can contribute to a discussion of the appropriateness of the RCT for use in community-based research and assessment of health promotion interventions. For example, randomization can be challenging in a community setting. Many potential participants wanted to sign up for the study with their family members and friends. People who wanted to sign up were interested in bicycling and wanted to ride. Randomization was explained to participants, and people indicated—via informed consent—an understanding of the concept, but many still believed and assumed they would be assigned to the intervention group. This left people in the control group upset, and it affected participation in both groups. For example, a group of four sisters enrolled for the study at the Westlawn site. Three of the sisters were randomly assigned to the control group and one sister to the intervention group. Without her sisters to ride with, the intervention group–assigned participant never participated in any of the rides.

The second pillar of the RCT is control. While it may be easier to control for mitigating or confounding factors in clinical settings, being placed in a “control” group in a community setting can have repercussions that are problematic for community members and for researchers. It is important to note that communitybased research happens “in” communities and is not simply the recruitment of participants “from” communities. Recruitment materials advertised that people in the intervention group would be given a free bicycle, helmet, and bike lock. This helped get people interested in the study; however, many participants who were randomized into the control group and did not get a bicycle at the start became angry. Again, people understood the concept of randomization, but it did not help alleviate resentment about the research study.

Frustration with the study continued throughout the study period. Due to random chance, most participants in the Westlawn neighborhood were assigned to the control group. One researcher, who works in Westlawn on a regular basis, heard people continuing to express displeasure throughout the summer about not getting a bike and about not being able to ride. While control group members received a bicycle at the end of the study, by then it was late October in Wisconsin. This left the research team concerned about frustrated community members being less willing to participate in future studies and health promotion programs.

Finally, the terminology used by researchers can be problematic, especially in community settings. Academic research terminology may sound dehumanizing, such as “trial” or “control group,” especially when applied in community settings. given IRB requirements, research jargon spilt over into study recruitment flyers, consent forms, and tools. The terminology was mandated for use by academic institutions, but it did not work well in this small community-based pilot study.

➢ CONCLUSIONS

Limitations of this study include its small size as a pilot study and limited generalizability to other communities. While the RCT design helped ensure funding for the Biking for Health study, based on data provided by study participants, it also led to dissatisfaction and frustration among community participants. The study, however, may not have yielded as much information about the feasibility, fitness and health impact, and change in bicycle-related attitudes resulting from this intervention if the study lacked a comparison group. Based on our experience, future community-based research studies considering an RCT design should contemplate using a crossover approach as well as clustering friends and family during randomization. The study did yield important lessons about the need for more discussion on how to merge academic research methods, tools, and protocols with what actually works and is needed in community settings.

REFERENCES

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Arcuri JF, Borghi-Silva A, Labadessa I. g., Sentanin AC, Candolo C, Pires Di Lorenzo V (2016). Validity and reliability of the 6-Minute Step Test in healthy individuals: A cross-sectional study. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 26, 69–75. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein R, Schneider R, Denomie M, Dressel A, Welch W, Kusch J, & Sosa M (2016). Biking for health: Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial examining the behavioral, fitness, and health impact of a bicycling intervention on lower-income adults. Manuscript submitted for publication. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Translation Science Institute of Southeast Wisconsin. (n.d.). Community. Retrieved from https://ctsi.mcw.edu/community/

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, . . . Oja P (2003). International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 35, 1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo CJ, Smit E, Andersen RE, Carter-Pokras O, & Ainsworth BE (2000). Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 18, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill J, & Voros K (2007). Factors affecting bicycling demand: Initial survey findings from the Portland region. Transportation Research Record, 2031, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Emond CR, & Handy SI (2012). Factors associated with bicycling to high school: Insights from Davis, CA. Journal of Transport Geography, 20, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Engbers LH, & Hendriksen IJM (2010). Characteristics of population commuter cyclists in the Netherlands: Perceived barriers and facilitators in the personal, social and physical environment. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman J, & Mackenzie F (2005). The randomized controlled trial: gold standard, or merely standard? Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 48, 516–534. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2005.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M, & Chida Y (2008). Active commuting and cardiovascular risk: A meta-analytic review. Preventive Medicine, 46, 9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, . . . Bauman A (2007). Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation, 116, 1081–1093. doi: 10.1161/circulation.107.185649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Brenner BL, Lachapelle S, Amara DA, & Arniella g. (2009). Effective recruitment of minority populations through community-led strategies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37, S195–S200. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins K (2005, June). Gender and civic engagement: Secondary analysis of survey data (CIRCLE Working Paper No. 41). Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED494075.pdf

- League of American Bicyclists. (2013). The new majority: Pedaling towards equity. Retrieved from http://www.bikeleague.org/sites/default/files/equity_report.pdf

- National Center for Advancing Translational Science. (n.d.). Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. Retrieved from https://ncats.nih.gov/files/ctsa-factsheet.pdf

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, & Flegal KM (2014). Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. Journal of the American Medical Association, 311, 806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, & DiClemente CC (1986). Toward a comprehensive model of change. New York, NY: Platinum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reidy MC, Orpinas P, & Davis M (2012). Successful recruitment and retention of Latino study participants. Health Promotion Practice, 13, 779–787. doi: 10.1177/1524839911405842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2016). The state of obesity in Wisconsin. Retrieved from http://stateofobesity.org/states/wi/

- Sadler LS, Larson J, Bouregy S, LaPaglia D, Bridger L, McCaslin C, & Rockwell S (2012). Community-university partnerships in community-based research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 6, 463–469. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RJ, & Hu I (2015). Improving university transportation sustainability: Reducing barriers to campus bus and bicycling commuting. International Journal of Sustainability Policy and Practice, 11(1), 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RJ, Kusch J, Dressel A, & Bernstein R (in press). Can a twelve-week intervention reduce barriers to bicycling among overweight adults in low-income Latino and Black communities? Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S, Reading J, & Shephard RJ (1992). Revision of the physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q). Canadian Journal of Sport Sciences, 17, 338–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Labor U.S. (2013). Women as major health care consumers. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]