In 2016, the Rhode Island Department of Corrections (RIDOC) became the first state correctional system to initiate a comprehensive program to screen all individuals for opioid use disorder, to offer treatment with all three Food and Drug Administration–approved medications (i.e., methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone) to medically eligible incarcerated people, and to provide linkage to care in the community after release. In the first year of this program’s implementation, there was a 12% drop in statewide overdose deaths and a 61% drop in postincarceration overdose deaths.1 We describe the initiation and growth of this program with the hope that other jurisdictions will develop similar programs.

Opioid use disorder often leads to criminal justice involvement.2 People generally lose opioid tolerance during incarceration and so are more likely to overdose after release. The risk of overdose spikes during the first two weeks after release, making expedited transition to treatment in the community critical.3

RIDOC is a unified (prison and jail) state-run correctional system housing about 3000 men and women with 13 000 intakes and releases annually. It is the sole correctional authority in the state (there are no county jails); therefore, it is an ideal setting for statewide correctional implementation of medication for addiction treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder. RIDOC’s population is aged 18 years and older and is 84% male, 52% White, 23% Black, and 21% Hispanic. Before 2016, RIDOC had offered methadone for more than 30 years (limited to pregnant women and individuals being tapered off of methadone).

IMPLEMENTATION

In August 2015, Governor Gina Raimondo convened a task force that developed a statewide plan to reduce overdose deaths.4 As part of this initiative, the General Assembly of the State of Rhode Island approved $2 million in funding, primarily to expand RIDOC’s MAT program. In July 2016, methadone withdrawal protocols were stopped and prerelease inductions into MAT began. The rollout began in the women’s division and was later expanded to the men’s divisions. Induction protocols were established for methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone (oral while incarcerated and injectable just before release).

MAT is the most effective evidenced-based approach for opioid use disorder,5 with benefits to correctional populations including postincarceration reductions in illicit opioid use,6 criminal behavior,7 mortality and overdose risk,2 and HIV-risk behaviors6 and an increase in treatment engagement.6 Although MAT is effective, few US correctional facilities offer MAT, decreasing the likelihood of postrelease treatment engagement.

RIDOC contracted much of the treatment inside correctional facilities and the transition to care outside correctional facilities to CODAC Behavioral Healthcare, Inc., a state-certified center of excellence in the treatment of opioid use disorder.4 CODAC is the state’s oldest opioid treatment program and the only not-for-profit one. For individuals reporting current MAT during commitment, nursing staff obtain written consent to confirm medication and dose with current prescriber and pharmacy, and MAT is continued. If MAT is not confirmed, individuals are referred to the program. An attempt is made to screen all individuals by using the Texas Christian University Drug Screen 5 within four days of commitment. Those who score positive for an opioid use disorder are assessed according to American Society of Addiction Medicine criteria and referred to a medical provider for further evaluation and treatment initiation.

In addition, people scheduled for release within three to six months are screened and offered MAT as appropriate. The decision of which MAT to offer a patient is determined clinically, primarily by past experiences, patient preference, and logistical considerations. Group counseling, individual counseling, discharge planning services, and prerelease enrollment in health insurance are all part of the comprehensive treatment services. If needed, CODAC staff will attempt health insurance enrollment after release. A memorandum of understanding between all licensed substance abuse providers ensures care coordination for RIDOC clients. Brown University School of Public Health research faculty are evaluating the program.

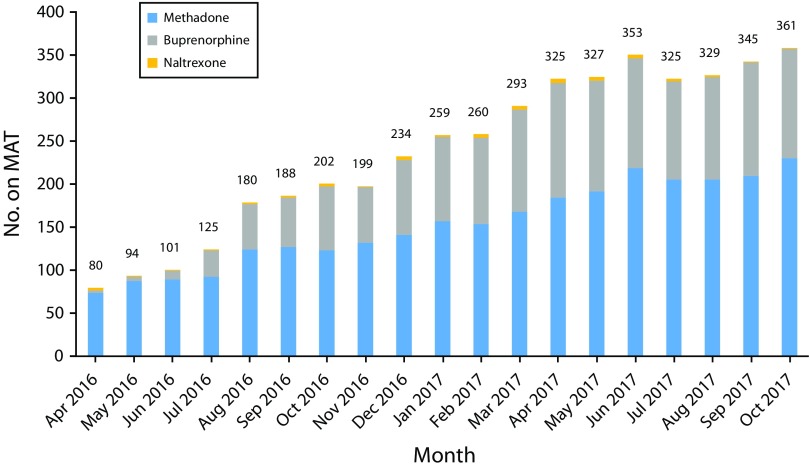

Between October 2016 and October 2017, screening increased by 75%. Approximately 25% of new commitments screened report an opioid use disorder. One obstacle to comprehensive screening is limited access after the day of commitment (e.g., court appointments, housing restrictions, visitations and releases [48% are released within 72 hours]). From April 2016 to October 2017, there was a 350% increase in individuals receiving MAT (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Medication Type Used by Individuals on Medication for Addiction Treatment (MAT): Rhode Island Department of Corrections, 2016–2017

RIDOC covers the cost of MAT, including wraparound services, at rates similar to or below those paid by private and public insurers. There is no cost to the patient. Protocols for induction, dosing, nonadherence, monitoring, and withdrawal (in the case of prolonged anticipated incarceration lasting more than two years) have been developed and continue to be modified (see http://www.doc.ri.gov for more information).

CHALLENGES

Diversion has been a concern of security staff, in part because medication lines are long and require more security time. Medical and security staff directly observe medication administration and check patients’ mouths before and after administration. Initial use of buprenorphine pills was changed to buprenorphine and naloxone film, as they are more difficult to divert because they dissolve faster. There have been no cases of injury from diverted medications. The methadone is liquid. Medical staff manage program consequences of diversion on an individualized basis. For logistical reasons, MAT dosing in some facilities takes place at night. Because of sleep disruption, this has been problematic for many individuals and is being transitioned to morning dosing.

Some nursing and correctional staff had initial negative perceptions of MAT. Some inmates reported hesitation with continuing treatment because of staff comments. Some patients expressed concern that they were “substituting one addiction for another” and “not drug free” while on MAT. Educational initiatives for both staff and inmates to alleviate concerns and stigma are under way. There has been a gradual transition to acceptance and even support for the program.

The coordination of postrelease care is a challenge. Individuals going to correctional facilities not offering MAT (federal or out of state) have to be weaned off MAT. Release to the community is often unpredictable. However, individuals can immediately continue treatment because they are already enrolled as CODAC patients.

VIABILITY

The Rhode Island state budget for 2017 officially contained $2 million for the implementation of the MAT expansion program and has been funded again through 2018. Governor Raimondo has highlighted the program’s efforts as a significant component of her statewide overdose and addiction prevention plan.4

System-wide changes also ensure that the program will become a part of RIDOC’s standard health care services. Provider time has been increased and additional providers have been hired. To facilitate communication between administration, security, rehabilitative services, and medical staff, program leaders established an MAT process team. Members serving on the Governor’s Overdose Prevention and Intervention Task Force provide the public insight on program challenges and changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The increase in illicit use of heroin and other illicit opioids is a serious public health concern. Despite justice-involved persons being especially vulnerable to overdose and relapse upon release, prisons and jails have been slow to allow this population access to MAT. Rhode Island’s statewide comprehensive program expansion at the RIDOC shows that MAT is feasible in correctional settings, and preliminary outcomes suggest strong rates of treatment retention after release. In the face of a severe public health crisis related to illicit opioid use, continuing and initiating MAT in correctional facilities with seamless linkage to care in the community should be a top priority for any community concerned about illicit opioid use and overdose deaths.

REFERENCES

- 1.Green TC, Clarke JG, Brinkley-Rubinstein L et al. Postincarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405–407. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B et al. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2011;106(1):32–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merrall EL, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA et al. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1545–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevent Overdose RI. The task force. Available at: http://preventoverdoseri.org/the-task-force. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- 5.Schuckit MA. Treatment of opioid-use disorders. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):357–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1604339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma A, O’Grady KE, Kelly SM, Gryczynski J, Mitchell SG, Schwartz RP. Pharmacotherapy for opioid dependence in jails and prisons: research review update and future directions. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016;7:27–40. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S81602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deck D, Wiitala W, McFarland B et al. Medicaid coverage, methadone maintenance, and felony arrests: outcomes of opiate treatment in two states. J Addict Dis. 2009;28(2):89–102. doi: 10.1080/10550880902772373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]