Abstract

Scientific evidence suggests women experience more severe problems when attempting to quit smoking relative to men. Yet, little work has examined potential explanatory variables that maintain sex differences in clinically-relevant smoking processes. Smoking outcome expectancies have demonstrated sex differences and associative relations with the smoking processes and behavior, including problems when attempting to quit, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, perceived barriers to quitting, and smoking abstinence. Thus, expectancies about the consequences of smoking may explain sex differences across these variables. Accordingly, the current study examined the explanatory role of smoking-outcome expectancies (e.g., long-term negative consequences, immediate negative consequences, sensory satisfaction, negative affect reduction, and appetite weight control) in models of sex differences across cessation-related problems, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, perceived barriers to quitting, and smoking abstinence. Participants included 450 (48.4% female; Mage = 37.45; SD = 13.50) treatment-seeking adult smokers. Results indicated that sex had an indirect effect on problems when attempting to quit smoking through immediate negative consequences and negative affect reduction expectancies; on smoking-specific experiential avoidance through long-term negative consequences, immediate negative consequences, and negative affect reduction expectancies; on barriers to quitting through negative affect reduction expectancies; and on abstinence through appetite weight control expectancies. The current findings suggest that sex differences in negative affect reduction expectancies and negative consequences expectancies may serve to maintain maladaptive smoking processes, while appetite weight control expectancies may promote short-term abstinence. These findings provide initial evidence for the conceptual role of smoking expectancies as potential ‘linking variables’ for sex differences in smoking variables.

Keywords: Sex, Smoking Outcome Expectancies, Smoking Processes, Tobacco Use, Abstinence

Inconsistent evidence exists regarding sex differences in smoking cessation (Smith et al., 2016). For example, a recent large-scale population based observational study failed to find sex differences for quit success (Jarvis, Cohen, Delnevo, & Giovino, 2013). Other work suggests significant sex differences exist (Smith et al., 2015), particularly for longer-term cessation outcomes (Perkins & Scott, 2008; Ward, Klesges, Zbikowski, Bliss, & Garvey, 1997). Although much work has focused on the role of sex differences in cessation outcomes (e.g., Smith, Bessette, Weinberger, Sheffer, & McKee, 2016), comparatively less scholarly attention has addressed smoking processes that may precede a quit attempt and be involved in the maintenance of smoking (Leventhal et al., 2007; Pang, Zvolensky, Schmidt, & Leventhal, 2014).

Some of the most prominent smoking processes related to the maintenance and relapse of smoking have included the severity of problems experienced when attempting to quit in the past (Zvolensky, Johnson, Leyro, Hogan, & Tursi, 2009), smoking-specific experiential avoidance (Farris, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2015; Gifford & Lillis, 2009), and perceived barriers for quitting (Garey, Kauffman, Neighbors, Schmidt, & Zvolensky, 2016; Macnee & Talsma, 1995). Past quit problems capture symptoms that have interfered with quit success such as weight gain, nausea, irritability, and anxiety and overall withdrawal experiences that contributed to relapse (Buckner et al., 2015). Smoking-specific experiential avoidance assesses the degree to which a smoker smokes to avoid unwanted thoughts (such as “I wish I could have a cigarette now.”) or sensations, including symptoms associated with cravings and acute withdrawal, that are specifically related to smoking (Gifford & Lillis, 2009). Perceived barriers for quitting reflects beliefs about potential barriers for quitting (Garey et al., 2017). Collectively, these constructs uniquely represent an array of early quit difficulties that negatively impact cessation and promote smoking maintenance.

Convergent evidence suggests women experience worse outcomes relative to men across these smoking processes (Garey, Farris, Schmidt, & Zvolensky, 2016; Pang et al., 2014; Robles et al., 2016; Zvolensky, Farris, Schmidt, & Smits, 2014). Such past work, although promising, is limited in that it thus far has neglected to isolate mechanisms that explain the observed sex differences in cessation-related problems, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, and perceived barriers for quitting. Without understanding the mechanisms that underlie these relations, little can be done to target these risk factors from an integrative perspective. Therefore, identifying explanatory variables that may maintain these sex differences in quit success is an important next step in this line of scientific inquiry.

Smoking outcome expectancies, reflecting beliefs about the positive and negative expected consequences or effects of smoking (Gwaltney, Shiffman, Balabanis, & Paty, 2005), may help explain observed sex differences in clinically-relevant smoking processes. Several influential theories and empirical studies underscore the importance of outcome expectancies as a key proximal mediator of smoking outcomes (Brandon, Juliano, & Copeland, 1999; Farris, Leventhal, Schmidt, & Zvolensky, 2015; Marlatt & Donovan, 2005). Empirically, some work suggests that expectancies for smoking to relieve negative affect, enhance a positive experience, and suppress appetite are risk factors for quit failure (Wetter et al., 1999). Other work suggests that only expectancies for smoking to relieve negative affect is a risk factor for quit failure, and expectancies about the negative consequences of smoking and, surprisingly, expectancies for smoking to suppress appetite serve as protective factors of abstinence (Wetter et al., 1994). Inconsistent findings support further research into these associations. Moreover, extant work has identified sex differences across facets of smoking expectancies, such that women often report greater expectancies for smoking to contribute to negative health and social consequences, relieve negative affect, and suppress appetite (Brandon & Baker, 1991; Pang et al., 2014; Wetter et al., 1999; Wetter et al., 1994). Indeed, expectancies for smoking to relieve negative affect appears to be a relatively stronger factor in maintaining smoking behavior among women versus men (Pang et al., 2014).

In addition to observed sex differences, negative affect reduction expectancies explain relations between affective symptoms (i.e., anxiety sensitivity and perceived stress) and prior quit problems, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, and perceived barriers to cessation (Farris et al., 2015; Garey et al., 2016; Robles et al., 2016). These studies provide initial empirical support for smoking expectancies as explanatory mechanisms. Yet, this work has focused exclusively on the negative affect reduction facet of smoking expectancies, which limits their contribution to current understandings for smoking expectancies in smoking models of indirect effects. It may be possible that other smoking outcome expectancies also serve as important explanatory variables.

Considering that extensive scientific evidence has documented greater expectancies for smoking to relieve negative affect, greater expectancies for smoking to contribute to negative health and social consequences, and greater expectancies to suppress appetite among women, it is plausible that these smoking expectancies serve a mechanistic function in observed sex differences across smoking processes outcomes. Indeed, smokers may firstly develop expectancies from smoking because of experiencing these outcomes from past use (including less negative mood, short and long-term negative consequences, and appetite suppression). With persistent use, smokers may begin to develop other cognitions about use, particularly from experiences when attempting to quit, such as identification of problems experienced when attempting to quit, understanding of smoking-specific experiential avoidance, perceived greater perceived barriers for quitting. The severity of the maladaptive smoking-processes may, in part, be influenced by expectancies regarding use. Importantly, smoking expectancies are unique from the identified processes, as evinced by 73–94% unique variance attributable to expectancies (Robles et al., 2016). Drawing from this theoretical model and informed by extant work and theoretical models of the negative reinforcement properties of addiction (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004), stronger beliefs about smoking to relieve negative affect may be related to severity of problems experienced when attempting to quit in the past, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, greater perceived barriers for quitting, and quit failure. Additionally, treatment-seeking smokers who expect smoking to result in more negative health and social consequences may report fewer difficulties in the variables of interest as well as be more likely to achieve quit success. Indeed, recognizing the negative consequences of smoking may support a cognitive shift in the perceived difficulties associated with quitting, such as severity of problems experienced when attempting to quit and perceived barriers to quitting. Consistent with extant work (Wetter et al., 1999; Wetter et al., 1994), women report greater expectancies for smoking to suppress their appetite. This belief, in turn, may contribute to greater quit difficulties and overall less quit success.

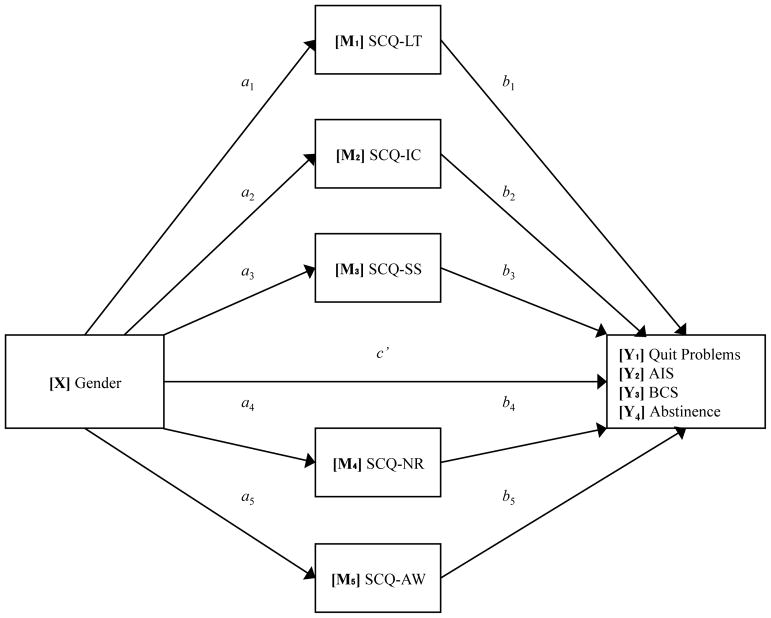

Despite evidence for sex differences in smoking outcome expectancies and smoking processes, no work has evaluated smoking outcome expectancies as explanatory variables for the sex differences across the clinically significant variables of severity of problems experienced when attempting to quit in the past, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, greater perceived barriers for quitting, and abstinence in a test of parallel mediation. Thus, the current study evaluated five facets of smoking outcome expectancies (e.g., long-term negative consequences, immediate negative consequences, sensory satisfaction, negative affect reduction, and appetite-weight control) as explanatory variables in the relation between sex and these dependent variables (see Figure 1). It was hypothesized women would evince more severe quit problems, higher smoking-specific experiential avoidance, greater barriers to smoking cessation, and lower rates of smoking abstinence than men through fewer long-term negative consequence expectancies, fewer immediate negative consequences, greater negative affect reduction, and greater appetite suppression smoking expectancies. To reduce potential confounding effects that may result from shared variance across facets of expectancies (MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000), parallel mediation was followed-up with simple mediation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of tested pathways.

Note: a path = Effect of X on M; b paths = Effect of M on Yi; c’ paths = Direct effect of X on Yi controlling for Mi. Three separate paths were conducted (Y1–4) with the predictor (M1–5). Covariates included: Presence Axis 1 (First et al., 1994), Tobacco-Related Medical Illnesses (Buckner et al., 2015), Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991), and Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Negative Affect Subscale (Watson et al., 1998). SCQ-LT = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Long Term Consequences; SCQ-IC = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Immediate Negative Consequences; SCQ-SS = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Sensory Satisfaction; SCQ-NR = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Negative Reinforcement; SCQ-AW = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Appetite-Weight Control (Garey et al., 2017); Quit problems = Smoking History Questionnaire (Brown et al., 2002), AIS = Smoking-specific Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (Gifford & Lillis, 2009); BCS = Barriers to Cessation Scale (Macnee & Talsma, 1995); Abstinence = 1-week post-quit abstinence (0 = not abstinent; 1 = abstinent).

Methods

Participants

A sample of 450 treatment-seeking adult smokers who responded to study advertisements (48.4% female; Mage = 37.45; SD = 13.50) were included in the current study. Exclusion criteria included suicidality and psychosis. Inclusion criteria for the current study included smoking at least 5 cigarettes per day for the past year. The racial/ethnic distribution of this sample was as follows: 86.2% White/Caucasian; 7.8% Black/Non-Hispanic; 0.7% Black/Hispanic; 2.2% Hispanic; 0.7% Asian; and 2.4% ‘Other.’ At least one current (past year) Axis I diagnosis was endorsed by 43.8% of the sample, most commonly social anxiety disorder (10.2%), generalized anxiety disorder (4.4%), current major depressive episode (4.0%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (3.3%). On average, participants reported smoking 17.49 cigarettes per day (SD = 9.75), had been a daily smoker for 19.13 years (SD = 13.29), and had an average expired carbon monoxide level of 20.06 parts per million (SD = 11.92). A moderate level of tobacco dependence was observed within the sample based on the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (M = 5.33, SD = 2.20; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991).

Procedures

Data for the present study were collected during a large, multi-site randomized controlled clinical trial examining the efficacy of two smoking cessation interventions described in detail elsewhere (Schmidt, Raines, Allan, & Zvolensky, 2016; Zvolensky et al., 2018). Interested persons responding to community-based advertisements (e.g., flyers, newspaper ads, radio announcements) contacted the research team and were provided with a detailed description of the study via phone. Participants were then screened for initial eligibility, and if eligible, scheduled for a baseline appointment. Upon arrival at their baseline appointment, participants provided informed consent and completed a semi-structured interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview-Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1994). Participants then completed a computerized self-report assessment battery as well as biochemical verification of smoking status. After completing the baseline assessments, participants were evaluated for and informed of their eligibility. The current study is based on secondary analyses of baseline data from the larger trial. Baseline data were included from all participants with complete data for the study variables regardless of eligibility for the larger trial. Only participants who reported at least 5 cigarettes per day for the past year were included in the current secondary analyses. All study procedures were approved by the corresponding Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information included sex, age, and race. Sex was included as a predictor.

Structured Clinical Interview-Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (SCID-I/NP)

Diagnostic assessments of past year Axis I psychopathology was conducted using the SCID-I/NP (First et al., 1994). All SCID-I/NP interviews were administered by trained research assistants or doctoral level staff and supervised by independent doctoral-level professionals. Interviews were audio-taped and the reliability of a random selection of 12.5% of interviews was checked (MJZ) for accuracy; there were no cases of disagreement.

Tobacco-Related Medical Problems

A medical history checklist was used to assess current and lifetime medical problems. As in past work (Buckner et al., 2015; Farris, Zvolensky, Blalock, & Schmidt, 2014; Leventhal, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2011), a composite variable was computed as an index of tobacco-related medical problems (labeled ‘Health’). Specifically, items in which participants indicated having ever been diagnosed (heart problems, hypertension, respiratory disease, or asthma; all coded 0 [no] or 1 [yes]) were summed and a total score was created, with greater scores reflecting the occurrence of multiple markers of tobacco-related disease.

Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD)

The FTCD (Fagerström, 2011; Heatherton et al., 1991) is a 6-item self-report scale that was used to assess gradations in tobacco dependence. Scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores reflecting high levels of physiological dependence on nicotine. The internal consistency in this sample was acceptable (α = .57).

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

The PANAS (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) measured the extent to which participants experienced 20 different feelings and emotions on a scale ranging from 1 (Very slightly or not at all) to 5 (Extremely) in the past month. The measure yields two factors, negative affect (NA) and positive affect (PA), and has strong documented psychometric properties (Watson et al., 1988). The NA subscale was utilized in the current study (α = .91).

Smoking Consequences Questionnaire (SCQ)

The SCQ (Brandon & Baker, 1991), is a measure that examined smoking expectancies on a 10 point scale for likelihood of occurrence, ranging from 0 (completely unlikely) to 9 (completely likely). The traditional 50-item measure employed a 4-factor structure. However, a recent study consisting of 2 independent samples of adult smokers provided evidence for a 5-factor structure (Garey et al., 2017). The 5-factor structure consisted of 35-items assessing outcome expectancies associated with (a) long-term negative consequences, (b) immediate negative consequences, (c) sensory satisfaction, (d) negative affect reduction/reinforcement, and (e) appetite-weight control. The 5-factor SCQ structure demonstrated appropriate construct, convergent, discriminant and predictive validity as well as stability across sex and time among treatment seeking smokers (Garey et al., 2017); thus, this structure was determined to be more appropriate for the present sample. The SCQ subscales demonstrated acceptable to excellent internal consistency in the present study (Long-Term Consequences: α = .89; Immediate Consequences: α = .78; Sensory Satisfaction: α = .93; Negative Reinforcement: α = .93; Appetite Control: α = .91).

Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ)

The SHQ is a self-report questionnaire used to assess smoking history (e.g., onset of regular daily smoking), pattern (e.g., number of cigarettes consumed per day), and problematic symptoms experienced during past quit attempts (e.g., weight gain, nausea, irritability, and anxiety (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002). As in past work (Zvolensky, Lejuez, Kahler, & Brown, 2003), a mean composite score of severity of problem symptoms experienced during past quit attempts was derived from this measure. Specifically, this measure includes 17 items such as “while trying to quit, how serious have each of the following problems been for you?” Items were rated on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) Likert scale. The severity of these items was summed and divided by 17 to compute the mean composite score. The SHQ was also employed to describe the sample smoking history.

Smoking-specific Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS)

The AIS assessed experiential avoidance related to smoking (Gifford & Lillis, 2009). Participants responded to 13-items according to a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very much). Items included “How likely is it that these feelings will lead you to smoke?” and “To what degree must you reduce how often you have these thoughts in order not to smoke.” The AIS has demonstrated good internal consistency (Gifford & Lillis, 2009). Higher scores represent more smoking-based experiential avoidance in the presence of uncomfortable or difficult sensations or thoughts, whereas lower scores suggest more ability to accept difficult feelings or thoughts without allowing them to trigger smoking. Past work has found good convergent and predictive validity of the AIS for smoking processes (Farris, Zvolensky, DiBello, & Schmidt, 2015; Zvolensky et al., 2014). In the present study, we utilized the total AIS score (α = .93).

Barriers to Cessation Scale (BCS)

The BCS (Macnee & Talsma, 1995), is a 19-item self-report assessment of perceived barriers to or stressors resulting from smoking cessation (e.g., “Feeling less in control of your moods”). Responses are provided on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not a barrier (0) to large barrier (3). The BCS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in a sample of treatment seeking smokers (Garey et al., 2017). The BCS total score demonstrated strong internal consistency in the present study (α = .89).

Abstinence

Self-reported smoking status was assessed in-person at the 1-week follow-up. The Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB; Brown et al., 1998; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) procedure was used to assess cigarette consumption for each day for the first 7 days post-quit. The assessment has demonstrated good reliability and validity with biochemical indices of smoking (Sobell & Sobell, 1996). Abstinence was verified by expired carbon monoxide (CO) using a CMD/CO Series Carbon Monoxide Monitor (Model 3110; Spirometrics, Inc., Auburn, ME). Self-reported abstinence was overridden by a positive expired CO reading (> 4 ppm; Perkins, Karelitz, & Jao, 2013). Abstinence was defined as self-reported no smoking, not even a puff, in the 7 days prior to the 1-week assessment and biochemical verification of abstinence (i.e., ppm <5 ppm). Of the 384 participants eligible for the larger trial, 114 self-reported abstinence at the 1-week follow-up. Biochemical verification confirmed abstinence in 79 of those participants. An intent-to-treat model was employed to evaluate 1-week smoking abstinence (0 = smoked, 1 = abstinent). Specifically, 163 participants had missing data at the 1-week follow-up and were therefore coded as having smoked. Ultimately, 79 participants were identified as abstinent at the 1-week follow-up and 305 were identified as having smoked.

Data Analytic Strategy

First, descriptive statistics and correlations were examined among study variables. Next, parallel mediation (multiple mediator) analyses were conducted using PROCESS (Preacher & Hayes, 2008), a conditional process model that utilizes an ordinary least squares-based path analytical framework to test for both direct and indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). Four independent models were conducted to examine the simultaneous role of smoking expectancies (5 SCQ subscales: Long-Term Consequences, Immediate Consequences, Sensory Satisfaction, Negative Reinforcement, and Appetite Control) in the association between sex and the four dependent variables: severity of prior quit problems (Quit Problems; Model 1), smoking-specific experiential avoidance (AIS; Model 2), barriers to smoking cessation (BCS; Model 3), and abstinence (Model 4). Model 4 utilized a subset of participants eligible for the larger trial (N = 384). Covariates included presence of an Axis I disorder, tobacco-related medical problems (Health), cigarette dependence (FTCD), and negative affectivity (PANAS-NA) because past work has indicated these variables are related to outcome expectancies for smoking and the studied dependent variables (Garey et al., 2016; Garey et al., 2017); treatment condition also was controlled for in the abstinence model.

Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) parallel mediation technique allows for one dependent variable, one predictor, and more than one simultaneous explanatory/mediator variable (MV). Standard errors of indirect effects are estimated using bootstrapping, which addresses the typically non-normal and asymmetric distribution of the standard error of product terms (Hayes, 2018). In parallel mediator models, the indirect effect for each statistical mediator (e.g., a1b1 or a2b2) is tested while controlling for all other mediators, which affords the testing of competing theoretical mechanisms (Hayes, 2013). Tests of simple mediation were conducted to supplement parallel mediation models. All indirect effects were subjected to 10,000 bootstrap re-samplings. A 95-percentile confidence interval (CI) estimate was derived for significance testing (Hayes, 2013).

Effect size in mediation analysis was assessed with the completely standardized indirect effect size (ES), represented as the indirect effect of a one unit change in the standardized predictor (1 unit=1 standard deviation) on the standardized outcome. ES is interpreted as small (0.01), medium (0.09), and large (0.25) (Preacher & Kelley, 2011).

Results

Zero-Order Correlations

All descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 1. Point-biserial correlation coefficients indicated that women reported significantly higher smoking expectancies across all SCQ subscales (r’s range = .11–.26, all p’s < .05), except Sensory Satisfaction. Women also reported more severe quit problems (r = .32, p < .001), AIS (r = .16, p = .001), and BCS (r = .23, p < .001). All SCQ subscales positively and significantly correlated with one other (r’s range = .12–.47, all p’s < .05), except Immediate Consequences and Sensory Satisfaction (r = −.10, p = .04), and with dependent variables (r’s range = .13–.52, all p’s < .01). All dependent variables significantly correlated (r’s range = .38–.58, p < .001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables

| Mean / n | SD / % | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (% female) | 218 | 48.4 | -- | |||||||||||

| 2. Axis I (% present) | 197 | 43.8 | .18*** | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. Health | 0.37 | .62 | .00 | .05 | -- | |||||||||

| 4. FTCD | 5.33 | 2.20 | −.04 | .07 | −.01 | -- | ||||||||

| 5. PANAS-NA | 19.11 | 7.31 | .14** | .35*** | .01 | .04 | -- | |||||||

| 6. SCQ-LT | 8.00 | 1.29 | .11* | −.05 | −.02 | .10* | .04 | -- | ||||||

| 7. SCQ-IC | 5.06 | 1.68 | .14** | .10* | .02 | .13** | .18*** | .47*** | -- | |||||

| 8. SCQ- SS | 5.27 | 2.37 | .01 | −.03 | −.10* | .18*** | .04 | .12* | −.10* | -- | ||||

| 9. SCQ-NR | 5.69 | 1.79 | .16*** | .16*** | −.11* | .17*** | .37*** | .32*** | .25*** | .28*** | -- | |||

| 10. SCQ- AW | 4.22 | 2.34 | .26*** | .09 | −.03 | .15** | .11* | .13** | .27*** | .17*** | .45*** | -- | ||

| 11.Quit Problems | 2.07 | .69 | .32*** | .23*** | .04 | .15** | .37*** | .20*** | .28*** | .14** | .42*** | .31*** | -- | |

| 12. AIS | 45.07 | 10.77 | .16*** | .15** | .02 | .25*** | .24*** | .37*** | .31*** | .13** | .47*** | .19*** | .38*** | -- |

| 13. BCS | 24.92 | 11.01 | .23*** | .16*** | −.03 | .17*** | .35*** | .26*** | .25*** | .19*** | .52*** | .29*** | .49*** | .58*** |

Note. N = 450;

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Sex: 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Mental Illness 0= Absent, 1 = Present; Health = Tobacco-Related Medical Illnesses (Buckner, Zvolensky, Jeffries, & Schmidt, 2014), FTCD = Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991), PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Negative Affect Subscale (Watson et al., 1988), SCQ-LT = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Long Term Consequences; SCQ-IC = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Immediate Negative Consequences; SCQ-SS = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Sensory Satisfaction; SCQ-NR = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Negative Reinforcement; SCQ-AW = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Appetite-Weight Control (Garey et al., 2017), Quit Problems = Smoking History Questionnaire (Brown et al., 2002), AIS = Smoking-specific Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (Gifford & Lillis, 2009), BCS = Barriers to Cessation Scale (Macnee & Talsma, 1995).

Parallel Mediation Analyses

Model 1 tested the indirect association between sex and quit problems through SCQ subscales. Regression coefficients are presented in Table 2. An initial model with quit problems regressed on sex and covariates was significant (F[5, 444] = 27.93, p < .001). The proposed model with sex, covariates, and explanatory variables accounted for significant variance in quit problems (R2 = .33, F[10, 439] = 21.52, p < .001). Individual tests of parallel mediation supported a significant indirect effect for sex on quit problems through Immediate Consequences (a2b2 = .02, 95% CI [.002, .050]) and Negative Reinforcement (a4b4 = .03, 95% CI [.008, .069]). ES for significant models were generally small (Immediate Consequences: ES = .01, 95% CI [.002, .040]; Negative Reinforcement: ES= .02, 95% CI [.006, .053]). Examination of indirect effects suggested that being female indirectly related to increased quit problems though independent paths of increased Immediate Consequences and Negative Reinforcement.

Table 2.

Indirect effects between sex and outcomes for parallel mediation.

| Effect | Quit Problems | Smoking-Specific Avoidance and Inflexibility | Barriers to Cessation Scale | Abstinence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| c | 0.37 | 0.06 | (0.260, 0.488) | 2.82 | 0.97 | (0.909, 4.727) | 4.25 | 0.96 | (2.359, 6.141) | 0.47 | 0.26 | (−0.043, 0.980) |

| c' | 0.29 | 0.06 | (0.174, 0.398) | 1.54 | 0.89 | (−0.212, 3.294) | 2.80 | 0.90 | (1.018, 4.574) | 0.27 | 0.28 | (−0.279, 0.815) |

| SCQ-LT as mediator | ||||||||||||

| a | 0.31 | 0.12 | (0.070, 0.555) | 0.31 | 0.12 | (0.070, 0.555) | 0.31 | 0.12 | (0.070, 0.555) | 0.28 | 0.12 | (0.036, 0.523) |

| b | 0.02 | 0.03 | (−0.028, 0.070) | 1.67 | 0.39 | (0.905, 2.441) | 0.71 | 0.40 | (−0.068, 1.489) | 0.11 | 0.14 | (−0.156, 0.38) |

| a1b1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | (−0.009, 0.029) | 0.52 | 0.28 | (0.094, 1.204) | 0.22 | 0.18 | (−0.023, 0.689) | 0.03 | 0.05 | (−0.034, 0.164) |

| SCQ-IC as mediator | ||||||||||||

| a | 0.41 | 0.16 | (0.099, 0.720) | 0.41 | 0.16 | (0.099, 0.720) | 0.41 | 0.16 | (0.099, 0.720) | 0.41 | 0.16 | (0.085, 0.731) |

| b | 0.04 | 0.02 | (0.006, 0.083) | 0.66 | 0.31 | (0.058, 1.257) | 0.41 | 0.31 | (−0.197, 1.02) | 0.01 | 0.10 | (−0.181, 0.196) |

| a2b2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | (0.002, 0.050) | 0.27 | 0.17 | (0.025, 0.734) | 0.17 | 0.16 | (−0.05, 0.614) | 0.003 | 0.04 | (−0.086, 0.102) |

| SCQ-SS as mediator | ||||||||||||

| a | 0.09 | 0.22 | (−0.349, 0.531) | 0.09 | 0.22 | (−0.349, 0.531) | 0.09 | 0.22 | (−0.349, 0.531) | 0.13 | 0.24 | (−0.345, 0.598) |

| b | 0.02 | 0.01 | (−0.008, 0.041) | 0.03 | 0.19 | (−0.354, 0.407) | 0.28 | 0.20 | (−0.106, 0.666) | 0.04 | 0.06 | (−0.080, 0.158) |

| a3b3 | 0.002 | 0.005 | (−0.005, 0.017) | 0.002 | 0.05 | (−0.078, 0.142) | 0.03 | 0.08 | (−0.084, 0.246) | 0.01 | 0.02 | (−0.017, 0.082) |

| SCQ-NR as mediator | ||||||||||||

| a | 0.41 | 0.16 | (0.106, 0.723) | 0.41 | 0.16 | (0.106, 0.723) | 0.41 | 0.16 | (0.106, 0.723) | 0.47 | 0.17 | (0.143, 0.805) |

| b | 0.07 | 0.02 | (0.036, 0.113) | 2.09 | 0.30 | (1.497, 2.692) | 2.12 | 0.31 | (1.513, 2.725) | −0.12 | 0.09 | (−0.304, 0.059) |

| a4b4 | 0.03 | 0.02 | (0.008, 0.069) | 0.87 | 0.37 | (0.235, 1.712) | 0.88 | 0.38 | (0.220, 1.689) | −0.06 | 0.05 | (−0.193, 0.022) |

| SCQ-AW as mediator | ||||||||||||

| a | 1.20 | 0.21 | (0.783, 1.627) | 1.20 | 0.21 | (0.783, 1.627) | 1.20 | 0.21 | (0.783, 1.627) | 1.36 | 0.23 | (0.902, 1.819) |

| b | 0.03 | 0.01 | (−0.001, 0.052) | −0.32 | 0.21 | (−0.738, 0.099) | 0.13 | 0.22 | (−0.292, 0.557) | 0.16 | 0.07 | (0.032, 0.295) |

| a5b5 | 0.03 | 0.02 | (−.0004, 0.072) | −0.38 | 0.27 | (−0.980, 0.084) | 0.16 | 0.26 | (−0.322, 0.710) | 0.22 | 0.10 | (0.048, 0.439) |

Note. Statistically significant indirect effects are bolded. a, b, c, and c' represent unstandardized regression coefficients: a = direct effect of sex on mediator; b = direct effect of mediator on outcomes; c = total effect of sex on outcome, without accounting for mediators; c’ = direct effect of sex on outcomes when accounting for mediators; anbn = Specific Indirect Effect through identified mediator. 95% CI for Indirect Effects were bias corrected and subjected to 10000 bootstrap samples. Covariates for all models included: Presence Axis 1 (First et al., 1994), Tobacco-Related Medical Illnesses (Buckner et al., 2014), FTCD = Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991), PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Negative Affect Subscale (Watson et al., 1988), SCQ-LT = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Long Term Consequences; SCQ-IC = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Immediate Negative Consequences; SCQ-SS = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Sensory Satisfaction; SCQ-NR = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Negative Reinforcement; SCQ-AW = Smoking Consequence Questionnaire-Appetite-Weight Control (Garey et al., 2017), Quit problems = Smoking History Questionnaire (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002), AIS = Smoking-specific Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (Gifford & Lillis, 2009), BCS = Barriers to Cessation Scale (Macnee & Talsma, 1995).

Model 2 tested the indirect association between sex and AIS through SCQ subscales. Regression coefficients are presented in Table 2. An initial model with AIS regressed on sex and covariates was significant (F[5, 444] = 13.51, p < .001). The proposed model with sex, covariates, and explanatory variables accounted for significant variance in AIS (R2 = .33, F[10, 439] = 21.72, p < .001). Individual tests of parallel mediation supported a significant indirect effect for sex on AIS through Long-Term Consequences (a1b1 = .52, 95% CI [.094, 1.204]), Immediate Consequences (a2b2 = .27, 95% CI [.025, .734]),1 and Negative Reinforcement (a4b4 = .87, 95% CI [.240, 1.712]). ES for significant models were small (Long-Term Consequences: ES = .03, 95% CI [.005, .057]; Immediate Consequences: ES = .01, 95% CI [.001, .035]; Negative Reinforcement: ES= .04, 95% CI [.011, .081]). Examination of indirect effects suggested that being female indirectly related to increased AIS though independent paths of increased Long-Term Consequences, Immediate Consequences, and Negative Reinforcement.

Model 3 tested the indirect association between sex and BCS through SCQ subscales. Regression coefficients are presented in Table 2. An initial model with BCS regressed on sex and covariates was significant (F[5, 444] = 20.20, p < .001). The proposed model with sex, covariates, and explanatory variables accounted for significant variance in BCS (R2 = .34, F[10, 439] = 22.82, p < .001). Individual tests of parallel mediation supported a significant indirect effect for sex on quit problems through Negative Reinforcement (a4b4 = .88, 95% CI [.220, 1.689]). Again, ES for the significant model were small (Negative Reinforcement: ES= .04, 95% CI [.010, .081]). Examination of indirect effects suggested that being female indirectly related to increased BCS though increased Negative Reinforcement.

Model 4 tested the indirect association between sex and abstinence through SCQ subscales. Log odds coefficients are presented in Table 2. Individual tests of parallel mediation supported a significant indirect effect for sex on abstinence through Appetite Control (a4b4 = .22, 95% CI [.048, .439]). Examination of indirect effects suggested that being female indirectly related to increased abstinence though increased Appetite Control expectancies.

Simple Mediation Analyses

Tests of simple indirect effects revealed a significant indirect effect of sex on quit problems through Long-Term Consequences (a2b2 = .03, 95% CI [.008, .054]), Immediate Consequences (a2b2 = .03, 95% CI [.007, .062]), Negative Reinforcement (a4b4 = .05, 95% CI [.014, .089]), and Appetite Control (a4b4 = .07, 95% CI [.037, .116]). Regarding AIS, sex indirectly related to this outcome through Long-Term Consequences (a2b2 = .88, 95% CI [.210, 1.763]), Immediate Consequences (a2b2 = .63, 95% CI [.170, 1.304]), Negative Reinforcement (a4b4 = 1.014, 95% CI [.263, 1.948]), and Appetite Control (a4b4 = .60, 95% CI [.104, 1.237]). Sex exerted an indirect effect on BCS through Long-Term Consequences (a2b2 = .58, 95% CI [.166, 1.184]), Immediate Consequences (a2b2 = .42, 95% CI [.110, 0.980]), Negative Reinforcement (a4b4 = 1.05, 95% CI [.262, 1.991]), and Appetite Control (a4b4 = 1.09, 95% CI [.550, 1.855]). Lastly, an indirect effect was observed from sex to abstinence through Appetite Control (a4b4 = .19, 95% CI [.028, .390]).

Discussion

The current study tested the indirect effect of sex on clinically significant variables of severity of problems experienced (e.g., withdrawal, negative mood) when attempting to quit in the past, smoking-specific experiential avoidance, greater perceived barriers for quitting, and short-term abstinence through smoking outcome expectancies. As hypothesized, results indicated that sex had an indirect effect on all dependent variables through select smoking outcome expectancies. Further, all effects were observed after controlling for competing smoking outcome expectancies, mental illness, tobacco-related medical illness, cigarette dependence, and propensity towards experiencing negative affect.

Consistent with the negative reinforcement model of addiction (Baker et al., 2004), the current findings suggest that substantive sex differences in negative affect reduction expectancies may be related to more maladaptive cognitive-affective smoking processes. Specifically, women tended to expect smoking to relieve negative affect states and symptoms more than men, which contributed to more severe quit problems, less flexibility when responding to smoking-specific internal cues, and more perceived barriers to cessation. These findings are consistent with prior work that has implicated smoking to relieve negative affect as a more pertinent expectancy in maintaining smoking behavior among women versus men (Pang et al., 2014). The current work further developed this research by identifying how such differences contribute to distal smoking processes that may maintain smoking.

Beyond negative reinforcement smoking outcome expectancies, evidence emerged for the relevance of immediate and long-term negative consequences in tested models with smoking processes. Immediate negative consequences were found to be a statistically significant explanatory variable for the effect of sex on severity of problems experienced when attempting to quit in the past and smoking-specific experiential avoidance whereas long-term negative consequences mediated sex differences on smoking-specific experiential avoidance. The present results are consistent with previous findings that social stigmatization around smoking is more commonly experienced among women versus men (Woo, 2012). Theoretically, women with more strongly held expectancies about the negative consequences may be more perceptive of difficulties when attempting to quit in the past and more cognizant of their tendency to respond inflexibly to smoking-specific cues because of their increased attention to experiences and challenges. Importantly, these findings should be considered in the context of cigarette dependence. Specifically, a potential negative consequence of smoking is cigarette dependence. Smokers who perceived this as a core negative consequence may be experiencing greater cigarette dependence. Subsequently, these smokers may have greater difficulty quitting and report more maladaptive cognitive perceptions of smoking and quitting.

Although appetite weight control expectancies did not mediate sex difference in the smoking process, across both parallel and simple mediation models, results implicated appetite weight control expectancies as the only mediator for sex differences in abstinence. While current data support that women expect smoking to suppress appetite to a higher degree than men, having this belief encouraged abstinence, instead of hindering it. The association between greater appetite weight control expectancies and abstinence was also found by Wetter and colleagues (1994). Other work (see Wetter et al., 1999), however, found the opposite effect. It may be that these expectancies are more malleable and likely to change during treatment, which results in greater abstinence. In light of mixed findings between the current and past research (Wetter et al., 1999; Wetter et al., 1994), additional work is needed to fully understand the association between appetite weight control expectancies and abstinence as well as how change in these expectancies during treatment may influence abstinence across sex.

The current findings uniquely bridge seemingly disparate lines of scientific inquiry devoted to (a) understanding sex differences in smoking expectancies (Pang et al., 2014) and (b) elucidating underlying mechanisms that contribute to smoking processes that maintain the addiction and contribute to relapse (Brown et al., 2002; Cropsey et al., 2014; Slopen et al., 2013). Prior to the current investigation, theoretical and empirical models had yet to consider the concurrent role of smoking expectancies in sex differences in smoking processes. Overall, women reported significantly higher endorsement of all five expectancies and all five expectancies were significantly associated with all three dependent variables if examined independently. Given these associations it is possible that the absence of mediation effects for sensation seeking and appetite weight control were due to their shared variance with the other three expectancies to the extent that they were no longer associated with dependent variables when controlling for the other three. This matter is noteworthy considering that appetite weight control emerged as a mediator for all models when evaluated in tests of simple mediation. Thus, the shared variance between negative reinforcement expectancies and appetite weight control (20%) may have masked the role of appetite weight control in the tested models.

The theoretical implications of the present findings arise from examining the unique contributions of specific smoking expectancies as potential ‘linking variables’ for sex differences in smoking dependent variables even after controlling for other smoking expectancies and the fact that indirect patterns differ across smoking constructs. Further, the theoretical contribution of the present investigation stems from the statistical test of parallel mediation that controlled for other expectancies while testing the indirect effect of an identified expectancy. Such an approach strengthens confidence in the observed findings and provides justification for further examination of the significant explanatory expectancies (i.e., long-term negative consequences, immediate negative consequences, and negative affect reduction) in sex specific models of smoking. Despite the rigorous statistical approach employed, findings should be considered in the context of potential confounding effects (MacKinnon et al., 2000) and highlight the importance of isolated mediation when examining related constructs. Thus, based on present findings, it is recommended simple mediation be conducted as an adjunct to parallel mediation and findings be contextualized in the strengths and limitations of each analytic approach.

Clinically, the present data provide empirical evidence for sex-specific treatment approaches that target smoking expectancies. Indeed, it may be relatively more helpful to address expectancies for smoking to relieve negative affect and expectancies about the negative consequences of smoking among women than men because of the tendency for women to hold stronger beliefs about these outcomes and their demonstrated impact on smoking processes that may interfere with the quit process. For example, the association between these expectancies and smoking processes could be integrated into a motivational interviewing or acceptance-based approach to smoking cessation (Bommelé et al., 2017; Hettema & Hendricks, 2010), or presented as additional psychoeducation in standard smoking cessation treatment. Moreover, clinicians may consider using cognitive behavioral strategies to challenge maladaptive beliefs about smoking (i.e., negative reinforcement expectancies) and explore how expectancies about negative consequences of smoking develop and relate to client’s smoking patterns. As supported by the present investigation, such an approach may be particularly relevant for women.

The study implications should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, participants were primarily White/Caucasian, treatment-seeking smokers. Replication work is needed among a sample of ethnically/racially diverse smokers who are not seeking treatment to validate the generalizability of the observed pathways. Second, the nature of the data did not permit testing of temporal sequencing. Future work is needed to determine the directional effects of these relations. Third, this study utilized self-report measures. Future work would benefit from employing a multi-method approach such as interview assessments or implicit tests of smoking expectancies. Fourth, another potentially fruitful extension of this research is to consider potential moderators of the unique effects of specific expectancies on dependent variables, such as age, executive functioning, or related constructs. Fifth, despite statistically significant findings, the observed effects sizes were relatively small. Thus, the clinical impact of the present work should be interpreted with caution. Lastly, although the current study examined multiple dimensions of smoking expectancies, it is possible that other psycho-social constructs, such as smoking motives, may explain the observed sex differences in the studied dependent variables. To increase current theoretical and empirical understanding for sex differences in smoking processes, additional potential explanatory variables should be tested.

Overall, findings offer a unique perspective for the role of smoking expectancies in observed sex differences among smoking processes as well as the relative robustness of their contribution. The significant pathways suggest that different smoking expectancies (including negative affect reduction, immediate and long-term consequences, and appetite weight control) may be more pertinent to certain smoking outcomes than other expectancies. Within these models, negative affect reduction may serve as a key risk factor that contributes to a wide array of maladaptive cognitive smoking processes and explains sex differences in these processes. Moreover, the present study identified women as a group at greater risk for more severe maladaptive smoking processes and behavior through select smoking expectancies. This is not to say, however, that the tested indirect effects are non-substantial for men, but that the indirect effect may be more clinically-relevant for women. Future work is needed to examine the tested indirect effects in a multiple-group analysis to parse out the indirect effects across each sex. Additionally, strategic steps should be employed to test the current pathways on a sample of ethnically diverse smokers interested in quitting. An important ‘first-step’ is to educate researchers on the most appropriate methods to recruit these often to difficult to enroll smokers (Brodar et al., 2016). Such tactics should them be employed as part of a smoking cessation trial targeting ethnically diverse smokers. Finally, this area of research could benefit from continued investigation of the concurrent role of smoking outcome expectancies in sex differences among alternative smoking constructs

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funding was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH076629; Co-PIs: Norman B. Schmidt and Michael J. Zvolensky). Work on this paper was supported by funding from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (1F31DA043390; PI: Lorra Garey).

Footnotes

In an alternative analysis wherein age was included as a covariate, Immediate Consequences did not significantly mediate the relation of sex on AIS (a2b2 = .18, 95% CI [−.002, .612])

Declarations of Interest: All authors report no financial relationships with commercial interest

References

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological review. 2004;111(1):33. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommelé J, Schoenmakers TM, Kleinjan M, Peters GJY, Dijkstra A, Mheen D. Targeting hardcore smokers: The effects of an online tailored intervention, based on motivational interviewing techniques. British journal of health psychology. 2017;22(3):644–660. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Baker TB. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire: The subjective expected utility of smoking in college students. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;3(3):484. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Juliano LM, Copeland AL. Expectancies for tobacco smoking 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Brodar KE, Hall MG, Butler EN, Parada H, Stein-Seroussi A, Hanley S, Brewer NT. Recruiting diverse smokers: enrollment yields and cost. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2016;13(12):1251. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13121251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12(2):101. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez C, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2002;111(1):180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(1):180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, Shah SM, Leventhal AM, Minnix JA, Schmidt NB. Dysphoria and smoking among treatment seeking smokers: the role of smoking-related inflexibility/avoidance. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(1):45–51. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.927472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Jeffries ER, Schmidt NB. Robust impact of social anxiety in relation to coping motives and expectancies, barriers to quitting, and cessation-related problems. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2014;22(4):341. doi: 10.1037/a0037206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropsey KL, Leventhal AM, Stevens EN, Trent LR, Clark CB, Lahti AC, Hendricks PS. Expectancies for the effectiveness of different tobacco interventions account for racial and gender differences in motivation to quit and abstinence self-efficacy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(9):1174–1182. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;14(1):75–78. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Leventhal AM, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety sensitivity and pre-cessation smoking processes: Testing the independent and combined mediating effects of negative affect–reduction expectancies and motives. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2015;76(2):317–325. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, Blalock JA, Schmidt NB. Negative affect and smoking motives sequentially mediate the effect of panic attacks on tobacco-relevant processes. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2014;40(3):230–239. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.891038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, DiBello AM, Schmidt NB. Validation of the Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS) Among Treatment-Seeking Smokers. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pas0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Smoking-specific experiential avoidance cognition: Explanatory relevance to pre-and post-cessation nicotine withdrawal, craving, and negative affect. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;44:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Cheema MK, Otal TK, Schmidt NB, Neighbors C, Zvolensky MJ. The sequential pathway between trauma-related symptom severity and cognitive-based smoking processes through perceived stress and negative affect reduction expectancies among trauma exposed smokers. The American journal on addictions. 2016;25(7):565–572. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Farris SG, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. The role of smoking-specific experiential avoidance in the relation between perceived stress and tobacco dependence, perceived barriers to cessation, and problems during quit attempts among treatment-seeking smokers. Journal of contextual behavioral science. 2016;5(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Jardin C, Kauffman BY, Sharp C, Neighbors C, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Psychometric evaluation of the Barriers to Cessation Scale. Psychological assessment. 2017;29(7):844. doi: 10.1037/pas0000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Kauffman BY, Neighbors C, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Treatment attrition: Associations with negative affect smoking motives and barriers to quitting among treatment-seeking smokers. Addictive behaviors. 2016;63:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Manning K, Jardin C, Leventhal A, Stone M, Raines A, … Zvolensky M. Smoking Consequences Questionnaire: A Reevaluation of the Psychometric Properties Across Two Independent Samples of Smokers. Psychological assessment. 2017 doi: 10.1037/pas0000511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Lillis J. Avoidance and inflexibility as a common clinical pathway in obesity and smoking treatment. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(7):992–996. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: prediction of smoking lapse and relapse. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2005;114(4):661. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Methodology in the social sciences. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction to Alcohol and Other Drugs. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JE, Hendricks PS. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a meta-analytic review. American Psychological Association; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MJ, Cohen JE, Delnevo CD, Giovino GA. Dispelling myths about gender differences in smoking cessation: population data from the USA, Canada and Britain. Tobacco Control. 2013;22(5):356–360. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Waters AJ, Boyd S, Moolchan ET, Lerman C, Pickworth WB. Gender differences in acute tobacco withdrawal: effects on subjective, cognitive, and physiological measures. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2007;15(1):21. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Smoking-related correlates of depressive symptom dimensions in treatment-seeking smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13(8):668–676. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention science. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnee CL, Talsma A. Development and testing of the barriers to cessation scale. Nurs Res. 1995;44(4):214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pang RD, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB, Leventhal AM. Gender differences in negative reinforcement smoking expectancies. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014:ntu226. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Jao NC. Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(5):978–982. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Scott J. Sex differences in long-term smoking cessation rates due to nicotine patch. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(7):1245–1251. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior research methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological methods. 2011;16(2):93. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles Z, Garey L, Hogan J, Bakhshaie J, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Examining an underlying mechanism between perceived stress and smoking cessation-related outcomes. Addictive behaviors. 2016;58:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Raines AM, Allan NP, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety sensitivity risk reduction in smokers: a randomized control trial examining effects on panic. Behaviour research and therapy. 2016;77:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Kontos EZ, Ryff CD, Ayanian JZ, Albert MA, Williams DR. Psychosocial stress and cigarette smoking persistence, cessation, and relapse over 9–10 years: a prospective study of middle-aged adults in the United States. Cancer Causes & Control. 2013;24(10):1849–1863. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Bessette AJ, Weinberger AH, Sheffer CE, McKee SA. Sex/gender differences in smoking cessation: A review. Preventive medicine. 2016;92:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Kasza KA, Hyland A, Fong GT, Borland R, Brady K, … McKee SA. Gender differences in medication use and cigarette smoking cessation: results from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17(4):463–472. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Measuring alcohol consumption. Springer; 1992. Timeline follow-back; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Problem drinkers: Guided self-change treatment. Guilford Press; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward KD, Klesges RC, Zbikowski SM, Bliss RE, Garvey AJ. Gender differences in the outcome of an unaided smoking cessation attempt. Addictive behaviors. 1997;22(4):521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1988;54(6):1063. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Kenford SL, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. Gender differences in smoking cessation. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1999;67(4):555. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Smith SS, Kenford SL, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Hurt RD, … Baker TB. Smoking outcome expectancies: factor structure, predictive validity, and discriminant validity. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1994;103(4):801. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J. Gender differences in cigarette smoking: The relationship between social perceptions of cigarette smokers and smoking prevalence. Minnesota State University; Mankato: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, Schmidt NB, Smits JA. The Role of Smoking Inflexibility/Avoidance in the Relation Between Anxiety Sensitivity and Tobacco Use and Beliefs Among Treatment-Seeking Smokers. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Garey L, Allan NP, Farris SG, Raines AM, Smits JA, … Schmidt NB. Effects of anxiety sensitivity reduction on smoking abstinence: An analysis from a panic prevention program. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2018;86(5):474. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Johnson KA, Leyro TM, Hogan J, Tursi L. Quit-attempt history: Relation to current levels of emotional vulnerability among adult cigarette users. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2009;70(4):551–554. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez C, Kahler CW, Brown RA. Integrating an interoceptive exposure-based smoking cessation program into the cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder: Theoretical relevance and case demonstration. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2003;10(4):347–357. [Google Scholar]