Abstract

Reducing smoking among adolescents is a public health priority. Affect, craving, and cognitive processes have been identified as predictors of smoking in adolescents. The current study examined associations between implicit attitude for smoking (assessed via the positive/negative valence Implicit Association Test), and affect, craving, and smoking assessed using ecological momentary assessment (EMA). Adolescent smokers (n = 154; Mage = 16.57, SD = 1.12) completed a laboratory assessment of implicit smoking attitudes and carried a palm-top computer for several days while smoking ad libitum. During EMA, they recorded affect, craving, and smoking behavior. Data were analyzed using a multilevel path analysis. At the between-subjects level, more positive implicit smoking attitude was indirectly associated with smoking rate via craving. This association was moderated by positive affect, such that it was stronger for those with greater trait-like positive affect. At the event (within-subject) level, implicit attitude potentiated associations between stress and craving and between positive affect and craving. Individuals with a more positive implicit attitude exhibited more robust indirect associations between momentary stress/positive affect and smoking. In sum, a more positive implicit attitude to smoking is associated with overall levels of craving and smoking; and may potentiate momentary affect-craving associations. Interventions which modify implicit attitude may be an approach for reducing adolescent smoking.

Keywords: adolescent smoking, implicit associations, affect states

Smoking among adolescents is a significant public health concern (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2000). Virtually all smoking behavior is initiated during adolescence (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Smoking at an early age increases the likelihood of serious health problems later in life (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1990, 1994). It is estimated that approximately one-third of youth smokers will die prematurely (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996). Even though recent research has indicated that smoking is on the decline among adolescents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017), more than 3,200 teens and adolescents try a cigarette each day in the U.S., while an additional 2,100 youth transition to daily smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Although many adolescents are interested in smoking cessation, achieving and maintaining abstinence remains a difficult task among this population (Choi, Ahluwalia, & Nazir, 2002; Grimshaw et al., 2003; Stanton, Lowe, & Gillespie, 1996; Stanton, McClelland, Elwood, & Ferry, 1996; Stone & Kristeller, 1992; Sussman, Dent, Severson, Burton, & Flay, 1998; Turner & Mermelstein, 2004).

It is important to understand factors that may interfere with cessation among adolescents (Zhu, Sun, Billings, Choi, & Malarcher, 1999). One factor associated with smoking and relapse among adolescents is craving (Myers et al., 2011; Van Zundert, Ferguson, Shiffman, & Engels, 2012). Craving is a central aspect of many theories of smoking and relapse (Brandon, Vidrine, & Litvin, 2007; Tiffany, Warthen, & Goedeker, 2009). Craving can be elicited by the withdrawal process that begins rapidly after administration is complete (i.e., as soon as a person stops smoking) (see Sayette et al., 2000; Shiffman, 2000; West, Hajek, & Belcher, 1989). As a person moves further away from their last use point, craving begins to increase (Jarvik et al., 2000; Payne, Smith, Sturges, & Holleran, 1996). Contextual cues, including perceived stress, can also be a strong trigger of craving (Kleinjan, Visser, & Engels, 2012). Recent research has shown that momentary affective states may predict smoking and craving in adolescent smokers (Mermelstein, Hedeker, & Weinstein, 2010); however, research on ab libitum smoking in adolescents is limited. Understanding factors associated with craving among adolescents may shed light on smoking in this population.

Recent research has also focused on cognitive processes in tobacco addiction, in the hope of finding cognitive targets for intervention (C. D. Robinson, Waters, Kang, & Sofuoglu, 2017). According to the dual-process model of addiction, automatic (or implicit) cognitive processes are important for understanding addiction and relapse (Wiers et al., 2007). Automatic processes include attentional bias toward substance relevant stimuli (Waters & Sayette, 2006), implicit motivation toward use (Ostafin & Brooks, 2011), implicit expectancies (O’Connor & Colder, 2009), and, most pertinent to the current study, implicit attitudes to substance use (Waters et al., 2007). Implicit attitudes are rapid, automatic evaluations of a target concept (Cunningham, Preacher, & Banaji, 2001) that have been widely investigated in psychopathology (Roefs et al., 2011) and addiction (e.g., Marhe, Waters, van de Wetering, & Franken, 2013). In adult smokers, positive implicit attitudes to smoking have been associated with higher craving, and may be associated with relapse in some subgroups (Chassin, Presson, Sherman, Seo, & Macy, 2010). In a recent study of adolescents, positive implicit attitudes were associated with higher past year cigarette use (Ames, Xie, Shono, & Stacy, 2017). However, others have found that implicit attitudes to smoking do not predict daily smoking or nicotine dependence in adolescent Dutch and US smokers (H. Larsen et al., 2014).

The dual-process model also purports that effortful cognitive control is required to reduce the influence of automatic psychological processes, such as implicit attitudes (Wiers et al., 2007). Effortful cognitive control is the degree to which an individual is able to exert self-regulatory control over behavior (Hofmann, Friese, & Strack, 2009). Importantly, research shows that effortful control can be diminished (Muraven, Tice, & Baumeister, 1998), and when this occurs, automatic cognitive processes become more influential predictors of behavior (Hofmann & Friese, 2008; Hofmann et al., 2009; Hofmann, Rauch, & Gawronski, 2007; Ostafin, Marlatt, & Greenwald, 2008). This may be particularly important during adolescence, when effortful cognitive control has not yet been fully developed (Velanova, Wheeler, & Luna, 2009). Effortful control resources might also be diminished by negative affective states (Bruyneel, Dewitte, Franses, & Dekimpe, 2009) thereby increasing the influence of automatic cognitive processes (Ostafin & Brooks, 2011). In addition to negative affect, research suggests that stress may be especially important among smokers due to associations with cigarette craving (Buchmann et al., 2010). Furthermore, stress has been shown to diminish effortful control resources (Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). Thus, the associations between automatic cognitive processes, craving, and smoking may be greater in individuals with generally higher negative affect and/or stress.

The current study examines implicit attitudes as a moderator of within-subject associations between affect and craving/smoking. Previous research has shown that within-subject changes in stress/negative affect are associated with increased craving (Buchmann et al., 2010; Childs & de Wit, 2010; Kleinjan et al., 2012). Within-subject associations between stress/negative affect and craving may be particularly pronounced in individuals with more positive implicit attitudes, as negative affect states may interact with automatic cognitive processes to potentiate substance use (e.g., Ostafin & Brooks, 2011). The current study used ecological momentary assessment (EMA), which permitted collection of relatively large numbers of assessments from each participant, facilitating examination of within-subject associations.

Finally, some research has shown that positive affect may be associated with cigarette craving in ad libitum smokers (Zinser, Baker, Sherman, & Cannon, 1992). Indeed, Baker and colleagues have suggested a model of craving in which positive affect leads to smoking urge in non-deprived smokers, while negative affect is more important for deprived smokers (Baker, Morse, & Sherman, 1987). This has been supported by Zinser and colleagues (1992) who found that positive affect predicted craving in non-deprived smokers while negative affect was related to craving amongst deprived smokers. This is consistent with the notion that positive affect is linked to drug craving via underlying reward systems important during the initial stages of the development of drug dependence (T. E. Robinson & Berridge, 1993). In addition, positive affect may contribute to more rash action in the context of substance use (Cyders & Smith, 2008). It is worth noting that the empirical data on associations between positive affect and smoking outcomes are quite sparse. In addition, we are not aware of any studies that have examined the interaction between positive affect and automatic psychological processes as a predictor of smoking related outcomes. However, there is a theoretical basis for predicting this interaction.

Research suggests that positive emotional states may lead to “hot” information processing and an overreliance on automatic psychological processes (Cyders & Smith, 2008). Indeed, research has shown that high arousal positive affect may inhibit evaluations of risk, leading to more risky/impulsive behaviors (Eherenfreund-Hager & Taubman – Ben-Ari Orit, 2016). In addition, recent research has highlighted the importance of incentive-motivational models for adolescent use progression (see Lydon, Wilson, Child, & Geier, 2014). Though not examined in adolescent smoking, recent research has indicated that more positive implicit attitudes may moderate associations between positive affect and behavior (Bongers, Jansen, Houben, & Roefs, 2013). In a laboratory study examining alcohol consumption, Wardell and colleagues found that valenced affect (i.e., anything different from neutral affect) interacted with implicit tension-reduction expectancies to predict consumption; however, this was only observed for men (Wardell, Read, Curtin, & Merrill, 2011). Given the relative dearth of research on positive emotion and smoking, positive affect was also examined in this study.

In summary, smoking among adolescents represents a significant public health concern. However, achieving and maintaining abstinence is difficult for adolescents, and understanding precursors to smoking is important. The current study examined implicit attitudes as both a predictor variable and a moderator variable. Regarding the former, implicit attitude may be associated with higher craving and thereby be related to increased smoking. Moreover, as noted above, associations may be stronger in individuals with greater negative affect. Regarding the latter, within-subject associations between affect and craving/smoking may be greater in individuals with more positive implicit attitudes. The current study examines these associations in an EMA study of affect, craving, and smoking among a sample of ad libitum adolescent smokers.

Methods

Participants

Participants were adolescent daily smokers (n = 154), ranging in age from 14-18 (M = 16.57, SD = 1.12). Females (n = 60) comprised 38.85% of the sample; 81.53% were White, 7.64% Black, 7.64% were American Indian or Alaskan Native, 1.91% Asian, and 5.73% were of other races or did not respond. All participants were treated in accordance with American Psychological Association ethical guidelines for research (Sales & Folkman, 2000). This study was approved by the Internal Review Board at Brown University.

Procedure

Participants were recruited as part of a larger study on adolescent smoking cessation (N = 233). The current analysis examines a subsample of the larger sample (n = 154; see data preparation section) and examines ad libitum smoking prior to making a quit attempt. Participants initially reported to the lab where they were trained in the use of a hand-held personal computer (the Teen Electronic Diary [TED]). During this initial appointment, participants completed a series of paper-and-pencil assessments and reported demographic information. They were scheduled for follow-up sessions and left with the TED. At a future session, participants completed the smoking Implicit Association Test (IAT) and a measure of explicit smoking attitudes. The future session often occurred within 24 hours of the first session, but not always. Most participants carried the TED for at least one day prior to administration of the IAT (M = 1.54 days, SD = 1.22, Range = 0-7). For the current analysis, we exclude all EMA assessments prior to completing the IAT lab session (including those on the lab session day prior to the lab session; but not after the lab session). Thus, the IAT was assessed prior to all EMA data. This resulted in the removal of 560 momentary assessments (M = 3.64/subject). After the IAT lab assessment, adolescents continued carrying the TED for a number of ad libitum smoking days leading up to a quit attempt. All data presented were collected prior to the quit attempt.

Participants were told that the purpose of the current study was to better understand what happens to adolescents when they try to quit smoking. At the initial lab session, adolescents were trained on the use of the TED. They completed sample assessments and were able to ask any questions. They returned after the first day of using the TED, discussed their experiences with lab personnel, and completed measures of salivary cotinine and CO. Participants returned for a third visit between one and three days after the second visit for another lab check-in. During this visit, participants again completed measures of CO and salivary cotinine (as well as measures of quitting self-efficacy not examined here). In total, participants met with research staff six times over the course of the entire three-week study.

There were two types of assessments completed on the EMA device: random assessments and self-initiated smoking assessments. Random assessments were signaled throughout the day during groupings of three-hour block time intervals (i.e., 0:00–3:00, 3:00–6:00, 6:00–9:00, 9:00–12:00, 12:00–15:00, 15:00–18:00, 18:00–21:00, 21:00–24:00). Participants also self-initiated assessments just prior to smoking. Identical affect items were presented at both the random and self-initiated smoking assessments. Two previous manuscripts have been published from this data, however, these manuscripts did not examine the role of implicit attitude; further detail on methods are available here (see Hoeppner, Kahler, & Gwaltney, 2014; Roberts, Bidwell, Colby, & Gwaltney, 2015).

Apparatus

Teen Electronic Diary (TED).

The Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) portion of the study was administered on a palm top computer (the Teen Electronic Diary; TED). The TED software was administered on Hewlett Packard iPAQ hand-held computers. This model is 4.5” × 2.8” × 0.5” and weighs 4.67 oz. It has a 16 bit TFT color display. The HP iPAQ runs the Windows Mobile 2003 OS and has 32 MB of flash memory. It is powered by a rechargeable lithium ion battery. Participants responded to items by directly pressing on the screen with a stylus. The TED randomly signaled participants to complete an assessment multiple times/day. In addition, participants would self-initiate an assessment just prior to smoking. Participants could set the TED to ‘Suspend’ and/or ‘Sleep’ during times in which they are unable to complete an assessment. The EMA procedures (outlined in greater detail below) followed the same basic procedures for assessing affect and ad libitum smoking in Shiffman et al. (2002).

Measures

EMA Affect and Craving Assessments.

Affect items were developed based on the circumplex model of affect (R. J. Larsen, Diener, & Clark, 1992; Yik, Russell, & Steiger, 2011). Items were selected to map onto the four quadrants of the model. Participants rated current affect and craving on the TED at two types of assessments: (1) random assessments, and (2) self-initiated pre-smoking assessments. During both assessment types, participants rated current affects (e.g., How are you feeling: Stressed?, Sad?, Irritable?, Relaxed?, Fidgety?, Calm?, Excited?, Cheerful?, and Crave a cigarette?) on an 11-point scale (0- NO!! to 10-YES!!). A single indicator for negative affect was formed using the mean of Sad, Irritable, and Fidgety (α = .63). A single indicator for positive affect was formed using the mean of Cheerful and Excited (α = .72). A single indicator for stress was formed using the mean of Stressed, Relaxed (reversed), and Calm (reversed) (α = .75). These three variables served as the primary affect variables in the analysis.

EMA Smoking Assessments.

Participants were asked to enter a smoking assessment prior to each cigarette they smoked. Smoking assessments were self-initiated by participants by selecting a “smoking” button on the TED. This triggered a survey that mirrored the random assessments (i.e., assessing affect and craving items). There was a positive association between the mFTQ and smoking, indicating that individuals with more smoking assessments also had higher levels of nicotine dependence, B = 0.062, p = .003. In addition, craving was higher at smoking assessments (M = 8.30, SD = 2.07) than random assessments (M = 6.33, SD = 3.47), t(7168) = 27.55, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.63; suggesting that smoking assessments were being completed prior to actual smoking behavior. Finally, self-reported smoking in the last 24 hours was positively correlated with CO assessed at the second meeting (r = .30, p < .001) and smoking over the last two to three days (depending on when the third meeting occurred) was positively correlated with salivary cotinine from the third meeting (r = .35, p < .001).

Modified Fägerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (mFTQ) is the adolescent version of the Fägerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (Prokhorov, Koehly, Pallonen, & Hudmon, 1998; Prokhorov, Pallonen, Fava, Ding, & Niaura, 1996). This questionnaire contains 7-items with a specified scoring criteria to reach a decision point for three discrete levels of nicotine dependence (0-2 = no dependence; 3-5 = moderate dependence; 6-9 = substantial dependence). The mFTQ has shown good internal consistency and adequate test-retest reliability (Prokhorov et al., 2000; Prokhorov et al., 1996). Internal consistency in the current sample was α = .65.

Implicit Smoking Attitude was assessed using the Implicit Association Test (IAT), and was based on the IAT used by Waters et al. (2007). The IAT (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998) was programmed in E-Prime (Schneider, Eschman, & Zuccolotto, 2002) and had seven blocks: 1) Practice of categorization for the target concept (smoking/not smoking) (24 trials); 2) Practice of categorization for the attribute (good/bad) (24 trials); 3) First block of combined categorization task (Task 1) (smoking + good/not smoking + bad) (24 trials); 4) Second block for Task 1 (48 trials); 5) Practice of categorization for the target concept but with the response keys reversed from the 1) assignment (not smoking/smoking) (24 trials); 6) First block of alternative combined categorization task (Task 2) (e.g., not smoking + good/smoking + bad) (48 trials); 7) Second block for Task 2 (48 trials). Order of completion of the combined categorization blocks (i.e., 3–4, and 6–7) was counterbalanced across participants. Following Swanson, Rudman, and Greenwald (2001), pictures were used to capture concepts of smoking vs. not smoking. Smoking pictures consisted of a single smoking object (e.g., a cigarette). Not smoking pictures consisted of an everyday object such as a pencil and stapler. Words captured the “good” concept (Nice, Pleasant, Positive, Relaxing, Wonderful) and the “bad” concept (Nasty, Unpleasant, Negative, Irritating, Terrible).

Procedure: On each trial, a stimulus (word or picture) was presented in the middle of a computer screen. Labels were placed on each side of the screen to remind participants of the categories assigned to each key for the current task. Participants pressed either an “L” key or the “R” key on the keyboard on each trial. The instructions were to respond as quickly and as accurately as possible. In blocks 1, 2 and 5, the program selected items at random from the stimulus lists. In blocks 3, 4, 6 and 7, the program selected items at random such that the sequence of trials alternated between the presentation of a (smoking/not smoking) picture and the presentation of a (good/bad) word. After a correct response, the next trial was initiated after a 150 ms inter-trial interval. If the participant made an error, a red “X” appeared below the stimulus (picture or word) and remained until the participant responded correctly. Participants were instructed to correct their errors as quickly as possible.

The scoring algorithm recommended by Greenwald and colleagues was used to derive the IAT effect (Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji, 2003, Table 7). This algorithm involves computing the difference score between mean reaction time (RT) on Task 1 and Task 2 and dividing the difference score by the pooled standard deviation of RTs. The resulting IAT effect, D, is similar to an effect-size measure, and helps to mitigate a “cognitive skill” artifact associated with other scoring algorithms (Greenwald et al., 2003). The algorithm also eliminates 1) participants with RTs < 300 ms on >10% of the trials, and 2) RTs > 10,000 ms (9 participants). RTs on incorrect responses were replaced by the block mean (correct responses) + 600ms. The internal reliability of the IAT effect (D) (r = .78) was estimated by calculating the IAT effects (D scores) computed from blocks 3 + 6 and blocks 4 + 7, correlating these measures, and applying the Spearman-Brown formula to derive the split-half reliability coefficient (Parrott, 1991).

The smoking IAT assesses the relative strength of automatic associations in memory (De Houwer, Custers, & De Clercq, 2006). In the smoking IAT used here (a valence IAT), the IAT indicates whether associations are stronger between smoking and positive, and not smoking and negative, than between not smoking and positive, and smoking and negative (Waters et al., 2007). Administration and scoring of the IAT (using a “D score”) followed the procedures outlined in Greenwald et al. (2003). Higher (more positive) IAT D scores indicate more a positive implicit attitude toward smoking. Previous research supports the use of the valence IAT as a measure of automatic psychological processes (Cunningham et al., 2001).

Explicit smoking attitudes was assessed via 5 items. Participants were presented with the sentence root “Smoking is…” followed by 5 items anchored at opposing poles (positive/negative, irritating/relaxing, unpleasant/pleasant, terrible/wonderful, nasty/nice). Each item was rated on a 7-point scale (e.g., −3 = negative, 0 = neither, 3 = positive). Explicit smoking attitudes were added as a model covariate to control for reflective processes in the model. Internal reliability in the current sample was α = .78.

Data Preparation and Analysis

The primary analysis was conducted in Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. The model examined direct and indirect associations between smoking behavior and affect/stress via craving at both subject (level 2) and event levels (level 1). We further tested whether these paths were conditional on (moderated by) the IAT effect. IAT data were only available for n = 164, as this assessment was introduced after study launch. In addition, 10 individuals made a quit attempt prior to their IAT lab assessment; these individuals were excluded from the analysis. There were 7,170 ad libitum event-level assessments, nested in 1,069 days, across 154 participants available for the primary analysis. The primary analysis examined a multilevel path model of event-level smoking as a function of the IAT effect, trait-like affect, stress, and craving at the subject level (level 2), and as a function of current affect (positive and negative), stress, and craving at the momentary level (level 1). Further, we examined whether 1) associations between the IAT effect (level 2) and craving/smoking were moderated by affect states (level 2), and 2) the IAT effect (level 2) moderated associations between affect (positive and negative), stress, and craving at the momentary level (level 1). At the between-subjects level we use the distribution of product confidence limits approach to calculate bias corrected indirect effects from the IAT to craving and smoking (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007).

At the subject level (level 2), smoking (ratio of smoking to random assessments for each subject) was regressed onto grand mean centered craving (i.e., mean levels of craving from all individual assessments at the event level, centered across participants), grand mean centered positive affect, grand mean centered negative affect, and grand mean centered stress. Subject level craving was simultaneously regressed onto grand mean centered positive affect, grand mean centered negative affect, grand mean centered stress, and the grand mean centered IAT effect. Mean affect (level 2) was added as a moderator of the association between implicit attitudes and craving. Age and gender were added as covariates at level 2.

At the event level (level 1), we regressed event-level smoking (whether an adolescent was currently smoking) onto their person-day centered momentary craving, person-day centered positive affect, person-day centered negative affect, and person-day centered stress. In addition, craving was simultaneously regressed onto person-day centered positive affect, negative affect, and stress. The IAT was examined as a moderator of within-subject associations between affect/stress, craving, and smoking (i.e., cross-level interactions).

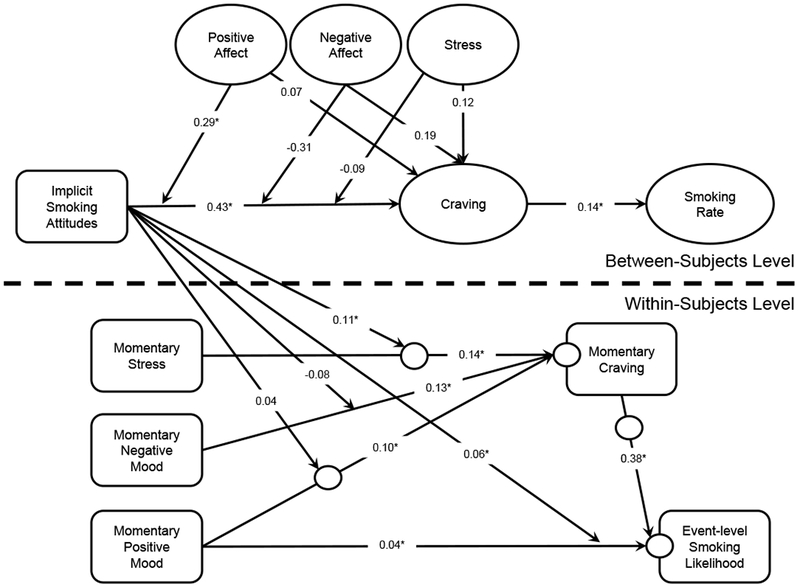

The overall model was complex, with a categorical outcome and variance parsed across levels. Thus, traditional fit indices are not available. We utilized the following approach to determine the most parsimonious model. First, we sequentially examined event-level slopes and intercepts for significant variance components. There was a significant variance component for the craving intercept (σ2 = 2.191, p < .001) and the smoking intercept (σ2 = 0.310, p < .001), as well as for the slopes between craving and momentary positive affect (σ2 = 0.049, p = .002), craving and stress (σ2 = 0.066, p < .001), and craving and smoking (σ2 = 0.047, p < .001). These were allowed to vary randomly and are represented in Figure 1 by open circles. Next, we trimmed non-significant direct paths to the outcome variable across levels to increase model parsimony. At the event-level (level 1), only positive affect significantly predicted smoking, thus, paths from stress and negative affect were both dropped. Mirrored paths, as well as the positive affect path, were dropped at the subject level (level 2). The final model is depicted in Figure 1. Coefficients (reported on Figure 1) reflect (unstandardized) effect sizes for pathways shown.

Figure 1.

Multilevel path model of smoking behavior at the subject (level 2) and event (level 1) level

Note. Age and gender were added as covariates on all between-subjects variables, however, are omitted above for clarity.

*p < .05

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. IAT D scores ranged from −1.71 to 1.03 (M = −0.41, SD = 0.56) and was significantly different from 0 (t[153] = −9.06, p < .001, Cohen’s d = −0.73), indicating that adolescent smokers found the classification task easier when smoking was paired with bad than when smoking was paired with good. There was no difference in IAT effect by gender, t(152) = 0.10, p = .921. Mean craving (M = 6.95, SD = 1.57) was not different for females (M = 7.15, SD = 1.46) than males (M = 6.79, SD = 1.64), t(152) = 1.40, p = .164, Cohen’s d = 0.23.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all study variables.

| Variables | Mean | SD | Skew | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject-level Data (Level 2) (n = 154) | ||||

| Gender | n/a | n/a | n/a | M = 94; F = 60 |

| Age | 16.56 | 1.11 | −0.31 | 14 to 18 |

| mFTQ | 4.74 | 1.47 | −0.09 | 2 to 8 |

| Implicit Smoking Attitude (IATD) | −0.41 | 0.56 | 0.16 | −1.71 to 1.03 |

| Explicit Smoking Attitude | −0.21 | 1.14 | −0.16 | −3.00 to 2.60 |

| Craving | 6.92 | 1.63 | −1.18 | 1 to 9.81 |

| Stress | 3.89 | 1.47 | 0.05 | 0.34 to 8.04 |

| Positive Affect | 4.72 | 1.63 | −0.32 | 0.42 to 8.25 |

| Negative Affect | 3.00 | 1.54 | 0.33 | 0.12 to 7.20 |

| Self-Monitoring Data (n = 7170) | ||||

| Days in Study | 4.31 | 2.42 | 0.51 | 1 to 13 |

| Total Daily Assessments | 7.19 | 3.28 | 0.49 | 1 to 27 |

| Daily Random Assessments | 4.25 | 1.61 | −0.69 | 0 to 8 |

| Daily Smoking Assessments | 2.94 | 2.50 | 1.22 | 0 to 20 |

Note. M= Male; F= Female. mFTQ = Modified Fägerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire.

EMA Monitoring

Individuals carried the TED for 1,069 days of monitoring after completing the IAT lab session. Participants carried the TED for 1 to 13 days (M = 4.20, SD = 2.23) of ad libitum smoking prior to making a quit attempt (all days in the analysis were from the pre-quit attempt data). During this time, participants completed 7,170 assessments (random assessments = 4,265; self-initiated pre-smoking assessments = 2,905), completing an average of 8.60 assessments per day (SD = 3.31). There were 4,839 random assessment signals during the monitoring period (i.e., between the IAT lab meeting and the quit attempt), yielding a compliance rate to random prompts of 88.14%.

Multilevel Path Analysis

Level 2 Analyses

At the between-subjects level (level 2), craving (Mean craving) was positively associated with smoking rate (ratio of smoking assessments to random assessments for each subject) (Figure 1). That is, subjects who reported generally higher craving reported a higher proportion of smoking (vs. random) assessments. None of the between-subjects affect states were associated with craving. Explicit smoking attitude (assessed using self-report) was not associated with mean craving (B = −0.092, p = .400) or smoking rate (B = 0.047, p = .293). Further, explicit attitudes did not moderate any of the within- or between-subject associations (ps .297-.703). In short, explicit attitudes had no significant effects in the model. We removed explicit attitudes from the model of the primary analyses reported in this paper.1

The IAT effect was positively associated with craving (B = 0.430, p = .030) and indirectly associated with smoking via craving (see Table 2). That is, subjects who reported a more positive IAT effect reported higher craving, and, in turn, reported a higher proportion of smoking assessments.

Table 2. Indirect, total, and conditional effects from multilevel path model.

| EFFECTS |

LL, ME, UL |

LL, ME, UL |

LL, ME, UL |

|---|---|---|---|

| BETWEEN-SUBJECTS (Level 2) | −1SD PA | Mean PA | +1SD PA |

| INDIRECT EFFECT: | |||

| IAT→Craving→Smoking Rate | −0.097, −0.014, 0.062 | 0.004, 0.061, 0.139 | 0.035, 0.137, 0.276 |

| WITHIN-SUBJECTS (Level 1) | −1SD IAT | Mean IAT | +1SD IAT |

| INDIRECT EFFECTS: | |||

| Positive Affect→Craving→Smoke | −0.001, 0.029, 0.059 | 0.017, 0.038, 0.059 | 0.018, 0.047, 0.076 |

| Negative Affect→Craving→Smoke | 0.035, 0.067, 0.098 | 0.026, 0.050, 0.073 | 0.000, 0.033, 0.065 |

| Stress→Craving→Smoke | 0.003, 0.033, 0.063 | 0.034, 0.056, 0.079 | 0.046, 0.079, 0.113 |

| TOTAL EFFECT: | |||

| Positive Affect→Smoking | −0.028, 0.027, 0.082 | 0.034, 0.073, 0.111 | 0.057, 0.118, 0.180 |

Note. LL = Lower Limit of 95% Confidence Interval; ME = Mean Effect; UL = Upper Limit of 95% Confidence Interval; IAT = Individual Differences in Smoking Implicit Attitude; PA = Between-subjects Positive Affect

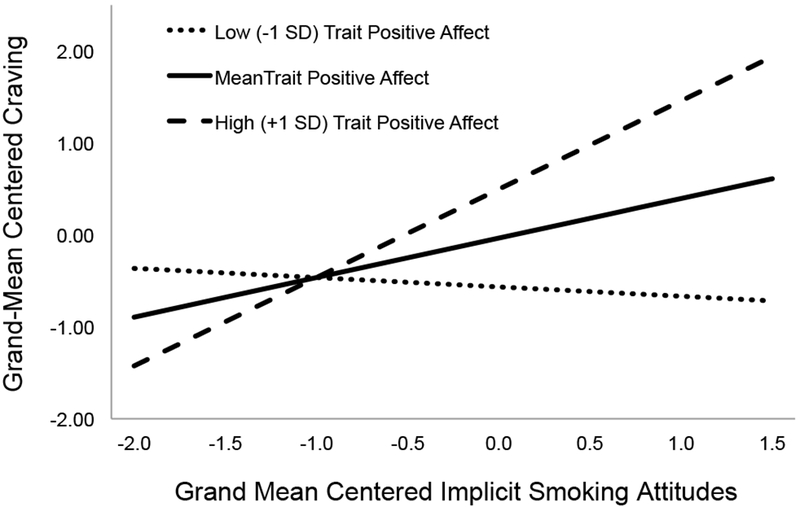

At the between-subjects level (level 2), the association between the IAT effect and craving was moderated by positive affect (see Figure 2). At high levels of trait positive affect (i.e., +1SD positive affect), the IAT effect was positively associated with craving (B = 0.963, p = .002), however at low levels (i.e., −1SD) of trait positive affect, the IAT effect was not associated with craving (B = −0.102, p = .696). Thus, the IAT effect was a more robust predictor of craving among ad libitum smoking adolescents with higher trait positive affect.

Figure 2.

Simple slopes of between-subjects cigarette craving on implicit smoking attitudes as a function of high and low levels of between-subjects positive affect.

Level 1 Analyses

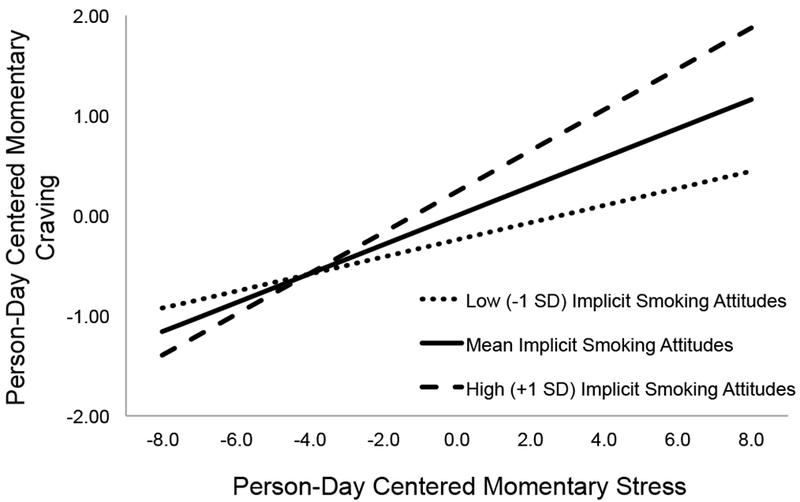

At the event-level (level 1), momentary negative affect was positively associated with momentary craving. Thus, when an individual reported higher negative affect than their subject-specific average on a particular day, he or she reported higher craving. Further, there was an indirect association between momentary negative affect and current smoking via momentary craving (see Table 2). There was also a positive association between momentary stress and craving that was moderated by the IAT effect (see Figure 3). At high levels of IAT (i.e., +1SD IAT), there was a robust positive association between momentary stress and craving (B = 0.207, p < .001), however this was attenuated at low levels (i.e., −1SD) of IAT (B = 0.084, p = .034). Further, the indirect association between momentary stress and event-level smoking was robust among those with high IAT; however, this effect was substantially attenuated and non-significant among those with low IAT.

Figure 3.

Simple slopes of momentary cigarette craving on momentary stress as a function of implicit smoking attitudes.

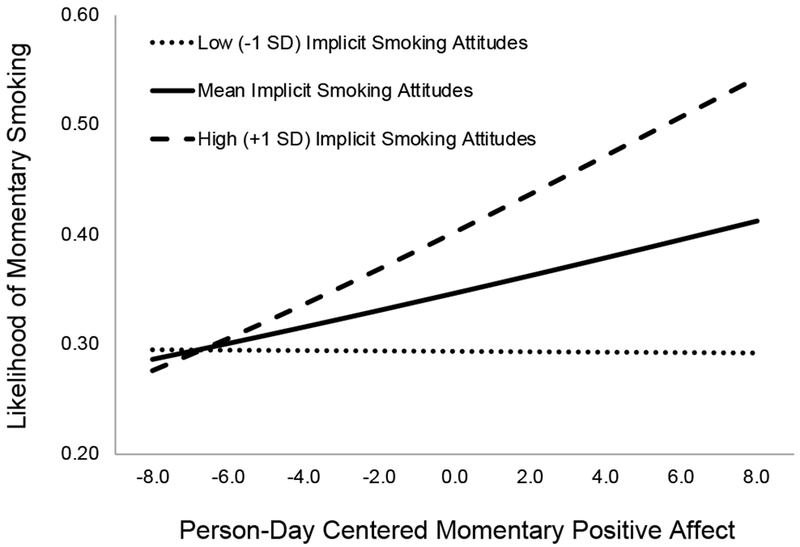

Again, at the event-level (level 1), momentary positive affect was directly associated with event-level smoking, as well as indirectly associated with smoking via higher momentary craving (see Table 2). Further, the IAT effect moderated the direct association between momentary positive affect and smoking (see Figure 4). At high levels of IAT (i.e., +1SD IAT), momentary positive affect was associated with an increased likelihood of smoking (B = 0.071, OR = 1.07, p = .002), however at low levels (i.e., −1SD) of IAT positive affect was not associated with smoking likelihood (B = −0.002, OR= 0.99, p = .934). Further, the total association between positive affect and smoking likelihood (i.e., direct and indirect via craving) was no longer significant (see Table 2).

Figure 4.

Simple slopes of momentary smoking likelihood on positive affect as a function of implicit smoking attitudes.

Discussion

The current study examined the associations between implicit attitudes, affect, craving, and smoking in adolescents. Implicit attitudes were examined as a predictor variable and a moderator variable. At the between-subject level, implicit smoking attitude was associated with craving, which in turn was associated with smoking. This association was moderated by positive affect, such that it was stronger for those with greater trait-like positive affect. At the event (within-subject) level, implicit attitude potentiated associations between stress and craving and between positive affect and craving. Individuals with a more positive implicit attitude exhibited more robust indirect associations between momentary stress/positive affect and smoking. These findings are discussed further below.

At the between-subjects level, implicit smoking attitude was positively associated with craving, and indirectly related to smoking via craving. That is, subjects who reported a more positive IAT effect reported higher craving, and, in turn, reported more smoking. The between-subject association between the IAT effect and craving is consistent with research in adults (Waters et al., 2007) and extends these findings to adolescents. These data suggest that modifying implicit smoking attitudes, perhaps through cognitive bias modification (Mühlig et al., 2016), may help reduce ad libitum craving and smoking in adolescents. However, one should note that attempts to change behavior through manipulation of implicit associations in other domains have hitherto not been promising (Forscher et al., 2017). On the other hand, Kong and colleagues (2015) found a small effect of cognitive bias modification on implicit approach bias and smoking behavior. Coupled with these results, it seems plausible that cognitive bias modification may alter automatic processes to reduce smoking. Also, it was noteworthy that the adolescents in the current study had a generally negative implicit attitude (faster response when smoking paired with bad) (see also Waters et al., 2007), although this may reflect the fact that the smokers in the current study were seeking to quit.

In addition, at the between-subjects level, it was hypothesized that affect states would moderate the association between the IAT effect and craving/smoking. Although we predicted that negative affect would serve as a moderator, the indirect association between implicit smoking attitudes and the rate of smoking (via craving) was more pronounced among individuals with higher levels of trait-like positive affect. The role of positive affect is discussed further below.

At the within-subjects level, it was hypothesized that momentary negative affect would be indirectly associated with ad libitum smoking via increased momentary craving, and that this association would be stronger among those with a more positive implicit attitude toward smoking. This hypothesis was supported for momentary stress, but not momentary negative affect. Thus, when an adolescent experienced more stress than usual, they reported more craving and smoking, and this association was particularly strong for those with a more positive implicit attitude. This aligns with research indicating that some negative affective states may synergistically interact with automatic cognitive processes to potentiate substance use (see Ostafin & Brooks, 2011), perhaps due to the effect of negative affect on one’s ability to effectively exert effort control (Bruyneel et al., 2009). However, this effect was not observed for negative affect (it was only observed for stress). This seems to highlight the distinct nature that qualitatively different negative affective states may have on effortful control. These findings suggest that developing adaptive ways of coping with momentary stress is particularly important among adolescent smokers, especially among those with a more positive implicit attitude.

An intriguing finding is that positive affect exhibited a number of significant associations with smoking. At the between-subjects level, as noted above, positive affect was the only variable that significantly moderated the indirect association between implicit attitude and smoking. At the event-level, positive affect was indirectly linked to event-level smoking via craving and was also the only momentary affective state with a direct association with concurrent smoking. This supports previous research linking positive affect with cigarette craving in ad libitum smokers (Zinser et al., 1992) and extends this finding to adolescents. Recent research has emphasized the role of incentive processes in adolescent smoking (Lydon et al., 2014). This research suggests that incentive-motivational processes are particularly important in the early stages of smoking (Piasecki, Hedeker, Dierker, & Mermelstein, 2016; Selya, Dierker, Rose, Hedeker, & Mermelstein, 2016), and positive affect may promote “hot” information processing that permits the execution of automatic processes.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted within the context of study limitations. First, participants were enrolled in a smoking cessation trial. Though we only included pre-cessation, ad libitum smoking, data in the analysis - all individuals had endorsed a desire to quit, and were only days away from making a cessation attempt. Thus, results may not generalize to more typical adolescent smokers not seeking to quit. Second, assessments occurring just prior to smoking may be subject to contamination by expectancy effects. Further, it is unclear how accurate these assessments are with regard to the timing of smoking behavior. For example, we are not certain if individuals are reporting affect, craving, and smoking events (a) before smoking, (b) while actually smoking, or (c) after smoking. The fact that craving was higher at smoking assessments, relative to random assessments, bolsters confidence that they were happening prior to smoking. In addition, this is a fairly standard method for assessing ad libitum smoking using EMA (for examples see Dunbar, Scharf, Kirchner, & Shiffman, 2010; Shiffman et al., 2014; Shiffman et al., 2002; Shiffman & Kirchner, 2009). Third, analyses are correlational, and the data do not permit strong conclusions regarding direction of causal relationships. For example, it is not known whether implicit attitude causes an increase in craving, or vice versa, though the current analysis does conceptualize implicit attitudes as more enduring aspects of cognition that do not fluctuate from moment to moment in the same manner as affect. Another limitation is the assessment of affect in this study. Though positive affect and stress showed good internal consistency, the internal consistency for the negative affect indicator was markedly lower. A replication of these findings with a more reliable assessment of affect is warranted. Finally, we did not examine the role of cognitive control in the current study. Given that dual process theory identifies cognitive control as a moderator of automatic psychological processes, future research should consider examining the current model in the context of varying levels of effortful control.

The study also had strengths. Most notably, to the best of our knowledge it is the first study to examine the association between a laboratory measure of implicit cognition and craving/smoking assessed in the field in adolescent smokers. The study had a relatively large sample size, increasing power to detect moderate-to-small effect sizes.

In sum, the data indicate that implicit smoking attitude may contribute to smoking by increasing craving and potentiating momentary affect-craving associations. Further, this study highlights the role of positive affect among adolescent smokers. The results may help to identify adolescent smokers who are at risk of elevated craving/smoking, and when they are at risk of craving and smoking. Moreover, approaches that reduce implicit attitude to smoking, or that reduce the relationship between implicit attitude and momentary affect-craving associations, may be an avenue for reducing adolescent smoking.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by grant R01 DA021677 to Chad J. Gwaltney and grant R21 DA 035761 to Robert D. Dvorak.

Footnotes

The indirect effect of IAT to smoking, via craving, was slightly more robust when controlling for explicit attitudes. Results of analyses which tested all of the direct and mediation effects for explicit attitudes (mirroring implicit attitude paths) are available upon request from the first author.

References

- Ames SL, Xie B, Shono Y, & Stacy AW (2017). Adolescents at risk for drug abuse: A 3-year dual-process analysis. Addiction, 112(5), 852–863. doi: 10.1111/add.13742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Morse E, & Sherman JE (1987). The motivation to use drugs: A psychobiological analysis of urges In Rivers PC (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol. 34. Alcohol and Addictive Behavior (pp. 257–323). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska University Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers P, Jansen A, Houben K, & Roefs A (2013). Happy eating: The Single Target Implicit Association Test predicts overeating after positive emotions. Eating Behaviors, 14(3), 348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Vidrine JI, & Litvin EB (2007). Relapse and relapse prevention. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 257–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruyneel SD, Dewitte S, Franses PH, & Dekimpe MG (2009). I felt low and my purse feels light: Depleting mood regulation attempts affect risk decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 22(2), 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann AF, Laucht M, Schmid B, Wiedemann K, Mann K, & Zimmermann US (2010). Cigarette craving increases after a psychosocial stress test and is related to cortisol stress response but not to dependence scores in daily smokers. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 24(2), 247–255. doi: 10.1177/0269881108095716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1990). The health benefits of smoking cessation: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1994). Preventing tobacco use among young people: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1996). Projected Smoking-Related Deaths Among Young—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 45(44), 971–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(23), 597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Seo D-C, & Macy JT (2010). Implicit and explicit attitudes predict smoking cessation: Moderating effects of experienced failure to control smoking and plans to quit. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 670–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs E, & de Wit H (2010). Effects of acute psychosocial stress on cigarette craving and smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12(4), 449–453. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Ahluwalia JS, & Nazir N (2002). Adolescent smoking cessation: implications for relapse-sensitive interventions. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine 156(6), 625–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham WA, Preacher KJ, & Banaji MR (2001). Implicit attitude measures: Consistency, stability, and convergent validity. Psychological Science, 12(2), 163–170. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Smith GT (2008). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 807–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer J, Custers R, & De Clercq A (2006). Do smokers have a negative implicit attitude toward smoking? Cognition and Emotion, 20(8), 1274–1284. doi: 10.1080/02699930500484506 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar MS, Scharf D, Kirchner T, & Shiffman S (2010). Do smokers crave cigarettes in some smoking situations more than others? Situational correlates of craving when smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12(3), 226–234. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntpl98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eherenfreund-Hager A, & Taubman – Ben-Ari Orit. (2016). The effect of affect induction and personal variables on young drivers’ willingness to drive recklessly. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 41(Part A), 138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2016.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forscher PS, Lai CK, Axt JR, Ebersole CR, Herman M, Devine PG, & Nosek BA (2017). A Meta-Analysis of Change in Implicit Bias. unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, & Schwartz JLK (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, & Banaji MR (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw G, Stanton A, Blackburn C, Andrews K, Grimshaw C, Vinogradova Y, & Robertson W (2003). Patterns of smoking, quit attempts and services for a cohort of 15- to 19-year-olds. Child: Care, Health and Development, 29(6), 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeppner BB, Kahler CW, & Gwaltney CJ (2014). Relationship between momentary affect states and self-efficacy in adolescent smokers. Health Psychology, 33(12), 1507–1517. doi: 10.1037/hea0000075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, & Friese M (2008). Impulses got the better of me: Alcohol moderates the influence of implicit attitudes toward food cues on eating behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(2), 420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Friese M, & Strack F (2009). Impulse and Self-Control From a Dual-Systems Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 162–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Rauch W, & Gawronski B (2007). And deplete us not into temptation: Automatic attitudes, dietary restraint, and self-regulatory resources as determinants of eating behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik ME, Madsen DC, Olmstead RE, Iwamoto-Schaap PN, Elins JL, & Benowitz NL (2000). Nicotine blood levels and subjective craving for cigarettes. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 66(3), 553–558. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00261-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, & Bachman JP (2000). Monitoring the future national survey results on adolescent drug use: overview of the key findings, 1999.

- Kleinjan M, Visser A-F, & Engels RCME (2012). Examining nicotine craving during abstinence among adolescent smokers: The roles of general perceived stress and temptation-coping strategies. Journal of Substance Use, 17(3), 249–259. doi: 10.3109/14659891.2011.565110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, Larsen H, Cavallo DA, Becker D, Cousijn J, Salemink E, … Krishnan-Sarin S (2015). Re-training automatic action tendencies to approach cigarettes among adolescent smokers: A pilot study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 41(5), 425–432. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1049492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen H, Kong G, Becker D, Cousijn J, Boendermaker W, Cavallo D, … Wiers R (2014). Implicit motivational processes underlying smoking in American and Dutch adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Diener E, & Clark MS (1992). Promises and problems with the circumplex model of emotion Emotion. (pp. 25–59). Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon DM, Wilson SJ, Child A, & Geier CF (2014). Adolescent brain maturation and smoking: What we know and where we’re headed. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 45, 323–342. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, & Lockwood CM (2007). Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODLIN. Behavior Research Methods, 39(3), 384–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhe R, Waters AJ, van de Wetering BJM, & Franken IHA (2013). Implicit and explicit drug-related cognitions during detoxification treatment are associated with drug relapse: An ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0030754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein RJ, Hedeker D, & Weinstein S (2010). Ecological Momentary Assessment of Mood-Smoking Relationships in Adolescents In Kassel JD (Ed.), Substance Abuse and Emotion (pp. 217–236). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlig S, Paulick J, Lindenmeyer J, Rinck M, Cina R, & Wiers RW (2016). Applying the ‘cognitive bias modification’ concept to smoking cessation—A systematic review. Sucht: Zeitschrift für Wissenschaft und Praxis, 62(6), 333–354. doi: 10.1024/0939-591l/a000454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, & Baumeister RF (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, Tice DM, & Baumeister RF (1998). Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 774–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus Statistical Modeling Software: Release 8.0. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Gwaltney CJ, Strong DR, Ramsey SE, Brown RA, Monti PM, & Colby SM (2011). Adolescent first lapse following smoking cessation: Situation characteristics, precipitants and proximal influences. Addictive Behaviors, 36(12), 1253–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RM, & Colder CR (2009). Influence of alcohol use experience and motivational drive on college students alcohol-related cognition. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(8), 1430–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostafin BD, & Brooks JJ (2011). Drinking for relief: Negative affect increases automatic alcohol motivation in coping-motivated drinkers. Motivation and Emotion, 35(3), 285–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ostafin BD, Marlatt GA, & Greenwald AG (2008). Drinking without thinking: An implicit measure of alcohol motivation predicts failure to control alcohol use. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(11), 1210–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AW (1991). Performance tests in human psychopharmacology (1): test reliability and standardization. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Payne T, Smith P, Sturges L, & Holleran S (1996). Reactivity to smoking cues: Mediating roles of nicotine dependence and duration of deprivation. . Addictive Behaviors, 21, 139–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Hedeker D, Dierker LC, & Mermelstein RJ (2016). Progression of nicotine dependence, mood level, and mood variability in adolescent smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(4), 484–493. doi: 10.1037/adb0000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, De Moor C, Pallonen UE, Hudmon KS, Koehly L, & Hu S (2000). Validation of the modified Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire with salivary cotinine among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 25(3), 429–433. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Koehly LM, Pallonen UE, & Hudmon KS (1998). Adolescent nicotine dependence measured by the Modified Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire at two time points. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 7(4), 35–47. doi: 10.1300/J029v07n04_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Pallonen UE, Fava JL, Ding L, & Niaura R (1996). Measuring nicotine dependence among high-risk adolescent smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 21(1), 117–127. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, Bidwell LC, Colby SM, & Gwaltney CJ (2015). With others or alone? Adolescent individual differences in the context of smoking lapses. Health Psychology, 34(11), 1066–1075. doi: 10.1037/hea0000211 10.1037/hea0000211.supp (Supplemental) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CD, Waters AJ, Kang N, & Sofuoglu M (2017). Neurocognitive Function as a Treatment Target for Tobacco Use Disorder. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 4, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, & Berridge KC (1993). The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews, 18(3), 247–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roefs A, Huijding J, Smulders FTY, MacLeod CM, de Jong PJ, Wiers RW, & Jansen ATM (2011). Implicit measures of association in psychopathology research. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 149–193. doi: 10.1037/a0021729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales BD, & Folkman S (2000). Ethics in research with human participants. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS, Martin CS, & Shadel WG (2000). The measurement of drug craving. Addiction, 95(Suppl2), S189–S210. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Eschman A, & Zuccolotto A (2002). E-Prime User’s Guide. Pittsburgh: Psychology Software Tools, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Selya AS, Dierker L, Rose JS, Hedeker D, & Mermelstein RJ (2016). Early-emerging nicotine dependence has lasting and time-varying effects on adolescent smoking behavior. Prevention Science, 17(6), 743–750. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0673-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S (2000). Comments on craving. Addiction, 95(Suppl2), S171–S175. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Dunbar MS, Li X, Scholl SM, Tindle HA, Anderson SJ, & Ferguson SG (2014). Craving in intermittent and daily smokers during ad libitum smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 16(8), 1063–1069. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, … Gnys M (2002). Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(4), 531–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, & Kirchner TR (2009). Cigarette-by-cigarette satisfaction during ad libitum smoking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(2), 348–359. doi: 10.1037/a0015620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton WR, Lowe JB, & Gillespie AM (1996). Adolescents’ experiences of smoking cessation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 43(1-2), 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton WR, McClelland M, Elwood C, & Ferry D (1996). Prevalence, reliability and bias of adolescents’ reports of smoking and quitting. Addiction, 91(11), 1705–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone SL, & Kristeller JL (1992). Attitudes of adolescents toward smoking cessation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 8, 221–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW, Severson H, Burton D, & Flay BR (1998). Self-initiated quitting among adolescent smokers. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted to Practice and Theory, 27(5, Pt 3), A19–A28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JE, Rudman LA, & Greenwald AG (2001). Using the Implicit Association Test to investigate attitude–behaviour consistency for stigmatised behaviour. Cognition and Emotion, 15(2), 207–230. doi: 10.1080/0269993004200060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Warthen MW, & Goedeker KC (2009). The functional significance of craving in nicotine dependence In Bevins RA & Caggiula AR (Eds.), The motivational impact of nicotine and its role in tobacco use. (Vol. 55, pp. 171–197). New York, NY US: Springer Science + Business Media. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner LR, & Mermelstein R (2004). Motivation and Reasons to Quit: Predictive Validity among Adolescent Smokers. American Journal of Health Behavior, 28(6), 542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General.. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zundert RM, Ferguson SG, Shiffman S, & Engels R (2012). Dynamic effects of craving and negative affect on adolescent smoking relapse. Health Psychology, 31(2), 226–234. doi: 10.1037/a0025204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velanova K, Wheeler ME, & Luna B (2009). The maturation of task set-related activation supports late developmental improvements in inhibitory control. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(40), 12558–12567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1579-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Read JP, Curtin JJ, & Merrill JE (2011). Mood and implicit alcohol expectancy processes: Predicting alcohol consumption in the laboratory. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(1), 119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AJ, Carter BL, Robinson JD, Wetter DW, Lam CY, & Cinciripini PM (2007). Implicit attitudes to smoking are associated with craving and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 91(2-3), 178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AJ, & Sayette MA (2006). Implicit Cognition and Tobacco Addiction In Wiers RW & Stacy AW (Eds.), Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. (pp. 309–338). Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- West RJ, Hajek P, & Belcher M (1989). Severity of withdrawal symptoms as a predictor of outcome of an attempt to quit smoking. Psychological Medicine, 19(4), 981–985. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700005705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Bartholow BD, van den Wildenberg E, Thush C, Engels RCME, Sher KJ, … Stacy AW (2007). Automatic and controlled processes and the development of addictive behaviors in adolescents: A review and a model. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 86(2), 263–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yik M, Russell JA, & Steiger JH (2011). A 12-point circumplex structure of core affect. Emotion, 11(4), 705–731. doi: 10.1037/a0023980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Sun J, Billings SC, Choi WS, & Malarcher A (1999). Predictors of smoking cessation in U.S. adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 16, 202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinser MC, Baker TB, Sherman JE, & Cannon DS (1992). Relation between self-reported affect and drug urges and cravings in continuing and withdrawing smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(4), 617–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]