Abstract

Background

Cell therapy with bone marrow (BM)-derived progenitors has emerged as a promising therapeutic for refractory angina (RA) patients. In the present study, we evaluated the safety and preliminary efficacy of transcatheter delivery of autologous BM-derived advanced therapy medicinal product CD133+ cells (ATMP-CD133) in RA patients, correlating perfusion outcome with cell function.

Methods

In the phase I “Endocavitary Injection of Bone Marrow Derived CD133+ Cells in Ischemic Refractory Cardiomyopathy” (RECARDIO) trial, a total of 10 patients with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction (ejection fraction ≤ 45%) and evidence of reversible ischemia, as assessed by single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), underwent BM aspiration and fluoroscopy-based percutaneous endomyocardial delivery of ATMP-CD133. Patients were evaluated at 6 and 12 months for safety and preliminary efficacy endpoints. ATMP-CD133 samples were used for in vitro correlations.

Results

Patients were treated safely with a mean number of 6.57 ± 3.45 × 106 ATMP-CD133. At 6-month follow-up, myocardial perfusion at SPECT was significantly ameliorated in terms of changes in summed stress (from 18.2 ± 8.6 to 13.8 ± 7.8, p = 0.05) and difference scores (from 12.0 ± 5.3 to 6.1 ± 4.0, p = 0.02) and number of segments with inducible ischemia (from 7.3 ± 2.2 to 4.0 ± 2.7, p = 0.003). Similarly, Canadian Cardiovascular Society and New York Heart Association classes significantly improved at follow-up vs baseline (p ≤ 0.001 and p = 0.007, respectively). Changes in summed stress score changes positively correlated with ATMP-CD133 release of proangiogenic cytokines HGF and PDGF-bb (r = 0.80, p = 0.009 and r = 0.77, p = 0.01, respectively) and negatively with the proinflammatory cytokines RANTES (r = − 0.79, p = 0.01) and IL-6 (r = − 0.76, p = 0.02).

Conclusion

Results of the RECARDIO trial suggested safety and efficacy in terms of clinical and perfusion outcomes in patients with RA and LV dysfunction. The observed link between myocardial perfusion improvements and ATMP-CD133 secretome may represent a proof of concept for further mechanistic investigations.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02059681. Registered 11 February 2014.

Background

Continual technical improvements in mechanical coronary revascularization have produced as a paradoxical effect a growing number of patients with severe coronary disease, which are no more suitable for further revascularizations and experience refractory angina (RA) despite best medical management. It has been estimated that RA approximates an incidence as high as 50,000 and 30,000–50,000 new cases per year in the USA and continental Europe, respectively [1, 2]. Although the mortality prognosis has improved over time, with current rates approaching 3–5% per year [3, 4], the morbidity counterpart of such a challenging condition still remains a relevant burden for patients as well as health care systems. In particular, RA patients complain of inadequate pain relief leading to revisits to local hospital emergency departments, and undergo repeated coronary investigations [5]. The presence of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction worsens this scenario, contributing to reduce long-term survival and to increase hospitalization rates [2]. In this context, it has been unambiguously shown that ischemia reduction has a pivotal importance for patient survival [6]. Available treatment options on top of best interventional and medical therapy are still limited. Enhanced external counterpulsation, shock waves and coronary sinus reduction [7, 8] have shown therapeutic potential, although none of them has so far gained enough acceptance to enter the routine therapeutic armamentarium.

Cell therapy (CT) with autologous bone marrow (BM)-derived or peripheral blood (PB)-derived vasculogenic cells has emerged as an alternative viable therapeutic option [9, 10]. Randomized controlled trials (RCT) as well as meta-analyses and pooled analyses have recognizably shown, in large cohorts of RA patients, that catheter-based intramyocardial injection of BM or PB-derived selected or unselected progenitors has the ability to improve symptoms, exercise capability and myocardial perfusion with durable effects [11–13].

Nevertheless, in order to gain widespread acceptance and reimbursement from health care systems, pivotal studies as well as large RCT better addressing the cell mode of action (MoA) are still awaited [14]. Moreover, the priority issue about safety and efficacy in the subset of RA patients with LV dysfunction remains to be confirmed, for which less information is available in the literature.

Our group has pioneered the feasibility and safety of direct intramyocardial delivery of BM-derived CD133+ progenitors when injected epicardially through a minimally invasive approach in the context of a “no-option” RA population [15]. Furthermore, we validated the good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compliant standard operative procedures (SOP) required to translate human BM-derived CD133+ cells as an autologous advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP-CD133) in the cardiovascular scenario [16, 17].

We here report 1-year safety and preliminary efficacy results of the transcatheter intramyocardial injection of ATMP-CD133 in RA patients with LV dysfunction and concomitant heart failure (HF) and the correlation with myocardial perfusion outcome with CD133+ cell function.

Methods

Study design

The “Endocavitary Injection of Bone Marrow Derived CD133+ Cells in Ischemic Refractory Cardiomyopathy” (RECARDIO) trial is a prospective, multicenter, unblinded, phase I clinical study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02059681). The trial was performed at two investigational sites: Centro Cardiologico Monzino-IRCCS (Milan, Italy) as the coordinating and recruiting center, and Città della Salute e della Scienza Hospital (Turin, Italy) as the recruiting center. The institutional review board at each center approved the protocol and all patients gave informed consent prior to participation. Patients were excluded in the case of denial and might withdraw from the study at any time, irrespective of the reason. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethical committees (CCFM225/612 and CS/154) and the Italian Competent Authority (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 15,934(13)PRE21-1199).

The study design comprised a screening phase in which patients were checked for inclusion/exclusion criteria and post-procedure follow-up visits scheduled at 6 and 12 months, as safety and efficacy endpoints (Fig. 1). Specifically, the baseline screening assessment was performed within 2 months before the injection procedure and included: clinical evaluation as Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes, concomitant medications, patients’ quality of life and health status; single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT); cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET); two-dimensional (2D) echocardiogram; cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) when applicable; Holter ECG monitoring; and blood tests. The patients’ quality of life and health status were evaluated using the Short Form-12 (SF-12) survey and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ). In particular, the SF-12 survey consists of two parts—the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS)—while the MLHFQ is a 21-question tool to test patients’ perception of the impact of HF.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart. SPECT gated-single photon emission computed tomography, CPET cardiopulmonary exercise testing, CMR cardiac magnetic resonance, 2D two-dimensional, ECG electrocardiogram, ATMP advanced therapy medicinal product, AE adverse event, SAE serious adverse event, MACE major adverse cardiac events

At 6 and 12 months, clinical evaluation, 2D echocardiogram and blood tests were repeated. Moreover, SPECT and CPET were also evaluated at 6 months. Adverse events (AE), serious adverse events (SAE) and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were continuously evaluated up to 12 months.

Study population

The study population consisted of patients with severe CCS angina class III–IV and/or NYHA score II–IV under maximal tolerated medical therapy for at least 3 months not eligible for any type of conventional mechanical revascularization procedure based on the most recent coronary angiography (≤ 12 months). Additional inclusion criteria were: LV ejection fraction (EF) ≤ 45% as determined by 2D echocardiogram, CMR, or left ventriculogram; a reversible perfusion defect ≥ 10% of the LV surface by SPECT; and peak oxygen consumption (VO2) ≤ 21 ml/kg/min at CPET. Major exclusion criteria included: myocardial infarction (MI) within 3 months; presence of LV thrombus; LV wall thickness < 8 mm at the target area of cell injections as assessed by 2D echocardiogram; mechanical aortic valve; severe renal failure (creatinine plasma level > 2.5 mg/dl); positive infectious-disease test for HIV, hepatitis B or C, Treponema pallidum, human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1 and 2; and history of malignancy in the past 5 years.

Study endpoints

The primary aim of the study was safety in terms of any treatment-emergent SAE documented up to 6 months post catheterization and defined as cardiac perforation, pericardial tamponade, sustained ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation and ectopic tissue formation. Additional safety endpoints were evaluated up to 12 months post procedure and included any AE, SAE and MACE defined as composite of death, nonfatal MI, stroke and hospitalization for worsening of HF.

The secondary aim was the efficacy of the procedure in terms of improvements of LV perfusion at SPECT and/or functional capacity as assessed by CPET at 6 months postoperatively.

The third aim was to correlate perfusion and functional benefits with in vitro angiogenic potency of injected cells in terms of endothelial differentiation, colony forming unit capacity and cytokine production.

Cell preparation

Approximately 350 ml of BM was aspirated from the posterior iliac crest under epidural anesthesia according to the anesthesiologist’s judgment. The procedures were performed by an experienced hematologist within a qualified operating room. BM blood samples were anticoagulated with sodium heparin 5000 UI, stored in bags and shipped at controlled temperature (+ 4 °C/+ 20 °C) to the GMP-qualified facility (Cell and Gene Therapy Laboratory “Stefano Verri”, Monza, Italy).

Since 2007, the Laboratory has been cleared by the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA)) for the manufacturing of ATMPs (current authorization aM-185 2017), including ATMP-CD133.

The manufacturing, quality control and transport processes were performed and documented in agreement with validated SOP and GMP requirements.

Each lot was released if the following specifications were met: cellularity 1–12 × 106 CD133+ cells; purity (% of CD133+ cells/CD45+ cells) ≥ 80%; vitality ≥ 80%; endotoxin < 0.5 EU/ml; and sterile. Cells were stored overnight, resuspended in 10 ml of physiological saline, aliquoted in a sterile polypropylene conical tube and packed by the manufacturer as a “ready-to-use” cell product. Based on our stability data [17], cell suspensions were administered within 24 h from the lot release.

Cell administration and postprocedure monitoring

The day following BM aspiration, patients were admitted to the catheterization laboratory to receive the fluoroscopy-based transendocardial cell injections. The injection technique was performed as previously described [18]. Briefly, selection of target injection sites was done by merging coronary angiography, SPECT and 2D echocardiogram imaging. Upon retrograde LV catheterization, two-view ventriculography was performed to trace LV chamber end-diastolic/end-systolic profiles and color-mark the target landing zone; the different sites for infusion were subsequently chosen within this area. To better guide the Helical Infusion Catheter (BioCardia Inc.), real-time intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) was used in all cases to monitor the appropriate intramyocardial location of the needle during cell delivery and to exclude the release of microbubbles into the cavity. Furthermore, ICE was able to directly visualize the cardiac structures (such as valves and ventricle papillary muscles) and promptly detect procedural complications (such as thrombus formation, valve damage, pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade). In selected cases, 3D electroanatomical mapping (CARTO; BiosenseWebster) was obtained in the area of interest to validate tissue viability by electrogram analysis at the site of injections [19].

The 10 ml total volume was delivered by means of a range of 11–13 injections by slow infusion of 0.5–0.7 ml from the aliquot syringes over 30 s. At the end of the injection procedure, an implantable loop recorder (ILR) was subcutaneously inserted in the upper chest area to provide 12-month continuous arrhythmia monitoring.

To rule out cardiac tamponade or other cardiac-related complications, all patients underwent a postprocedure 2D echocardiogram and then were monitored overnight by telemetry and measuring vital signs in the intensive care unit.

Patients were hospitalized for a minimum of 48 h after the procedure. Before discharge, 2D echocardiogram, 24-h ECG Holter monitoring, standard chest X-ray imaging and routine blood tests were checked.

Myocardial perfusion analysis

SPECT perfusion studies were performed at baseline and 6 months after the procedure to evaluate the presence and the extent of reversible ischemia, expressed as a percentage of the LV. Stress and rest SPECT images were acquired 15–60 min after the injection of 555 MBq 99mTc-Tetrofosmin. ECG-SPECT images were performed with patients in the supine position for a total of 64 projections, 3° interval, every 30 s, over a 180° elliptical orbit. Pharmacological stress with intravenous administration of dipyridamole (0.84 mg/kg over 6 min) or regadenoson (0.4 mg/5 ml) was used to obtain stress images.

Both stress and rest acquisitions were obtained using a dual-head digital camera at 90° geometry equipped with high-resolution collimators. LVEF and volumes were calculated using a completely automated algorithm, previously described and validated [20].

The gated images were normalized to the region of highest activity on the end-systolic image set. Regional myocardial perfusion was assessed on the summed images. Perfusion imaging was scored semi-quantitatively using a 20-segment model scored on a 5-point scale (0 = normal, 4 = no uptake) [21]. A perfusion defect with a score ≥ 3 was considered significant, and a segment score improved by at least one grade was considered reversible. The summed stress score (SSS) and summed rest score (SRS) were calculated in each patient by adding the 20 individual perfusion scores. The difference between the summed stress and rest scores is the summed difference score (SDS), which indicated the amount and the degree of reversible ischemia. The paired SPECT images were evaluated by two independent imaging readers blinded to the clinical data.

Echocardiographic and functional capacity assessments

A 2D echocardiogram was performed at baseline, before hospital discharge and after 6 and 12 months to evaluate LV function, volumes and wall motion score index (WMSI). Pericardial effusions and unwanted tissue changes were also assessed during the study period. Echocardiogram acquisition and analyses were performed according to the guidelines [22]. The 2D echocardiogram at screening was also applied to assess the presence and localization of LV wall thickness < 8 mm at the target sites of cell injections.

CPET studies were performed at baseline and 6 months postoperatively to assess changes in functional capacity. CPET were performed on a cycle ergometer using an incremental ramp protocol. Expiratory O2, CO2 and ventilation were measured breath by breath. Patients were encouraged to perform as maximal exercise as possible. Peak VO2 was reported as a mean over the last 20 s of exercise.

ATMP-CD133 in vitro analyses

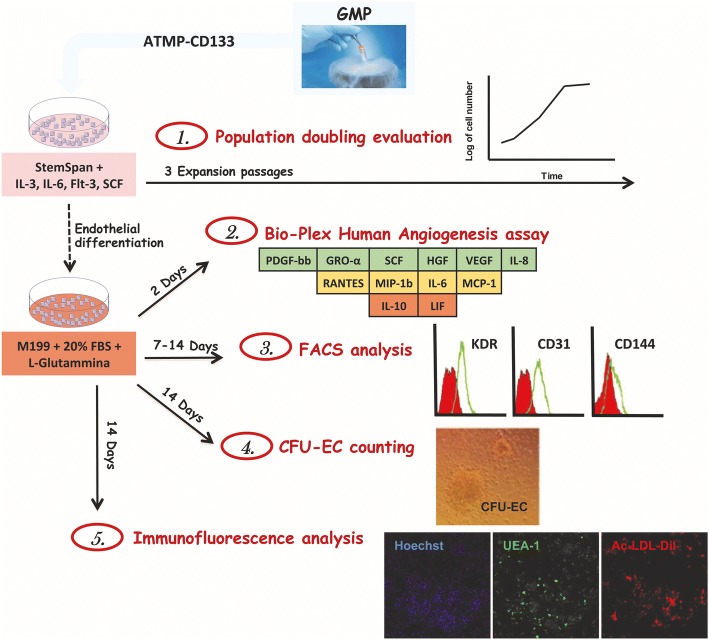

A small amount of each ATMP-CD133 lot was obtained from the GMP facility to perform in vitro studies. The experimental plan is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the in vitro experimental plan. GMP good manufacturing practice, ATMP advanced therapy medicinal product, IL interleukin, SCF stem cell factor, FBS fetal bovine serum, PDGF-bb platelet-derived growth factor type bb, GRO-α growth-regulated oncogene alpha, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, RANTES regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted, MIP-1b macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, LIF leukemia inhibitory factor, FACS fluorescence-activated cell sorting, CFU-EC colony forming unit-endothelial cell, Ac-LDL-Dil acetylated low-density lipoprotein labeled with dioctadecyl-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate, UEA-1 Ulex europaeus agglutinin-1

In detail, samples were thawed and seeded at 105 cells/well in 96-well plates in StemSpan (STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with interleukin (IL)-3 and IL-6 (both at 20 ng/ml; Peprotech), flt3 ligand (FLT3LG) and stem cell factor (SCF) (both at 100 ng/ml; Peprotech) to allow cell proliferation. The ATMP-CD133 growing capacity was assessed using the cumulative population doubling levels (CPDL), as previously described [23].

After three expansion passages, samples were seeded onto Fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich)-coated dishes in M199 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Microtech), 2 mM l-glutamine (Euroclone) and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin. Seeded cells were cultured for 2, 7 or 14 days to carry out the secretome and the flow cytometry analyses, to measure the production of colony forming unit-endothelial cells (CFU-EC) and to assess the immunophenotype of cultured cells. In particular, after 2 days, ATMP-CD133 secretome (expressed as pg/ml/105 cells) was characterized using a customized Bio-Plex assay (BIO-RAD). The panel comprised six proangiogenic factors including SCF, growth-regulated oncogene alpha (GRO-α), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor type bb (PDGF-bb), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and IL-8; four proinflammatory factors including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta (MIP-1β), regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) and IL-6; and two anti-angiogenic factors including leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and IL-10. As a negative control, nonconditioned medium was tested.

Immunophenotype analysis of endothelial markers (CD31, KDR, CD144) [24] was performed by multicolor flow cytometry on cultured cells after 7 and 14 days of endothelial conditioning. After detachment, using a nonenzymatic method, cells were resuspended in washing buffer (WB) containing PBS, 0.1% BSA (Gibco) and 2 mM EDTA (Gibco), and incubated in the dark for 15 min with suitable combinations of the following monoclonal or isotype-matched control antibodies: CD31-FITC (clone WM59; BD), KDR-PE (clone 89,106; R&D Systems) and CD144-APC (clone 16B1; R&D Systems). Then, samples were washed with 1 ml of WB and centrifuged for 10 min at 400 × g at 4 °C to remove unbound antibodies. Cells were then resuspended in 250 μl of WB and analyzed with a Gallios™ Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter).

After 14 days in differentiation-promoting conditions, a CFU-EC assay was performed as previously described [16]. For immunofluorescence analysis, cells were incubated in the dark for 5 h at 37 °C with 10 μg/ml of acetylated low-density lipoprotein labeled with dioctadecyl-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (Ac-LDL-Dil; Biomedical Technologies). After washing with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min and then stained with 40 μg/ml of FITC-labeled Lectin from Ulex europaeus agglutinin-1 (UEA-1 Lectin; Sigma-Aldrich) in the dark for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 333,428 (Sigma-Aldrich) in the dark for 15 min. Cells were observed with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range (IQR)), as appropriate. A within-subject Student’s t test was used to compare baseline and 6-month follow-up data. To evaluate differences in the distribution of continuous data at baseline, 6-month and 12-month follow-up, one-way ANOVA or the Friedman test for repeated measures were performed with Bonferroni or Dunn’s post-hoc analysis, respectively. Correlations between continuous variables were assessed by Pearson or Spearman test, as appropriate.

All tests were two-tailed, with a statistically significant p ≤ 0.05. All of the analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism® software (version 5.0).

Results

Patient characteristics

Between December 2013 and November 2016, 10 consecutive patients were enrolled and followed up for a period of 12 months according to the study protocol. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. All patients were males and the mean age was 69.4 ± 3.8 years. All patients had a history of coronary artery bypass grafting and seven patients experienced MI. Two patients were implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) recipients and two patients had a spinal cord stimulator. Medications at baseline, including the use of long-lasting nitroglycerin and ranolazine to manage RA, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Characteristic | Baseline |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 69.4 ± 3.8 |

| Males, n/total | 10/10 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 26.3 ± 2.4 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n/total | |

| Current smoking | 7/10 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6/10 |

| Hypertension | 10/10 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 9/10 |

| Family history of CAD | 6/10 |

| Medical history, n/total | |

| Prior CABG | 10/10 |

| Prior MI | 7/10 |

| Prior PCI | 8/10 |

| Prior ICD implant | 2/10 |

| Spinal cord stimulation | 2/10 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1/10 |

| Current medications, n/total | |

| β-Blockers | 9/10 |

| ACE inhibitors | 5/10 |

| ARBs | 3/10 |

| Calcium antagonists | 1/10 |

| Diuretics | 6/10 |

| Statins | 10/10 |

| Aspirin | 8/10 |

| Ranolazine | 7/10 |

| Long-lasting nitroglycerin | 6/10 |

| Cardiovascular condition at enrolment, mean ± SD | |

| LVEF (%) | 38.3 ± 5.1 |

| LV reversible ischemia (%) | 15.3 ± 8.4 |

| Peak VO2 (ml/kg/min) | 13.3 ± 1.8 |

Continuous data presented as mean ± SD

SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index, CAD coronary artery disease, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, MI myocardial infarction, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, ICD implantable cardioverter defibrillator, ACE angiotensin converting enzyme, ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, LV left ventricle, VO2 oxygen consumption

BM harvesting and ATMP-CD133 lot release

A mean 349 ± 57 ml of BM was aspirated under epidural anesthesia in the absence of adverse events. The mean procedural time was 24 ± 10 min.

At the end of the GMP manufacturing process, the mean number of ATMP-CD133 was 6.57 ± 3.45 × 106 cells. The median (IQR) cell purity and vitality was 88.77% (86.30–90.75%) and 99.90% (99.85–99.95%), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

ATMP-CD133 production and delivery

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| BM harvest (ml) | 349 ± 57 |

| ATMP-CD133 production | |

| Cellularity (× 106) | 6.57 ± 3.45 |

| Purity (%) | 88.77 (86.30–90.75) |

| Vitality (%) | 99.90 (99.85–99.95) |

| ATMP-CD133 delivery | |

| Number of injections | 12 (11–12) |

| Procedural duration (min) | 252 ± 91 |

| Mapping and injection time (min) | 105 ± 29 |

| Fluoroscopy time (min) | 63 ± 22 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), as appropriate

ATMP advanced therapy medicinal product, BM bone marrow

Transendocardial delivery of ATMP-CD133

Fluoroscopy-guided endocavitary intramyocardial cell injections were successfully accomplished in all 10 patients. Patients received a mean total volume of 7.76 ± 0.8 ml, delivered in a median of 12 independent injections of 0.5–0.7 ml each. All injections were double-checked with ICE to confirm engagement of the needle into the LV wall. Mean total procedural duration was 252 ± 91 min, while the mapping and injection time averaged 105 ± 29 min (Table 2). In four cases, the injection procedure was preceded by CARTO-guided electroanatomical mapping. An ILR was implanted in eight patients, with the exception of two cases who were already recipients of an ICD.

Safety profile of ATMP-CD133

There were no treatment-emergent in-hospital SAE related to the transendocardial delivery of ATMP-CD133. In 3 out of 10 patients, mild to moderate (≤ 15 mm) pericardial effusions were recorded on 2D echocardiogram during the 24 h postoperative monitoring. These events were all spontaneously resolved before hospital discharge. During the 12-month arrhythmia follow-up, no patient presented episodes of sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation as documented by ILR or ICD continuous monitoring.

No patient died during the 1-year safety follow-up. Two MACE and six nonprocedure-related SAE occurred during the 12-month study period. As for MACE, two patients experienced nonfatal non-ST elevation MI at 8 and 12 months, respectively, after the injection procedure. The first patient received PCI of the right coronary artery in territories distal from the targeted injection area and the second was managed conservatively based on coronary angiography. Two patients were treated with ICD implantation in primary prevention 6 months after the cell treatment. One patient reported two SAE during the follow-up, requiring emergency room admission for epigastric ulcer and subdural hematoma after 2 and 8 months, respectively. Finally, one patient, with known peripheral vascular disease, underwent elective percutaneous angioplasty of the femoral superficial artery 5 months after the procedure.

Perfusion outcome

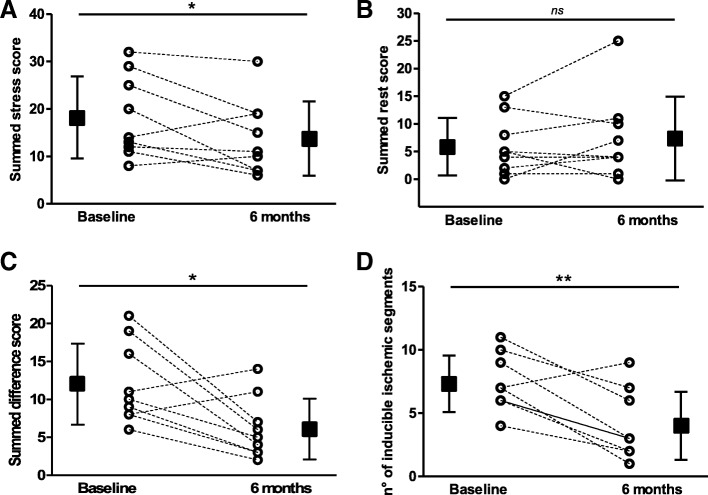

Follow-up SPECT was available in 9 out of 10 patients. Myocardial perfusion was significantly ameliorated at 6 months compared with baseline. In particular, the SSS improved from 18.2 ± 8.6 to 13.8 ± 7.8 (p = 0.05; Fig. 3a) while the SRS did not change significantly (5.9 ± 5.2 vs 7.3 ± 7.9, p = 0.38; Fig. 3b). Moreover, the SDS decreased from 12.0 ± 5.3 to 6.1 ± 4.0 (p = 0.02; Fig. 3c). As for ischemic myocardial segments, a highly significant difference was found in the number of segments showing inducible myocardial ischemia (from 7.3 ± 2.2 to 4.0 ± 2.7, p = 0.003; Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Myocardial perfusion at SPECT after 6-month follow-up. Changes of a summed stress score, b summed rest score, c summed difference score and d number of segments with inducible ischemia per patient. Square data markers with error bars represent mean ± SD of each SPECT parameter at baseline and 6 months (n = 9). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ns = not significant

Echocardiographic and functional outcome

LVEF, LV volumes and WMSI did not change significantly during the follow-up, as assessed by 2D echocardiogram (Table 3).

Table 3.

Echocardiographic findings at baseline and after 6 and 12 months

| Parameter | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%) | 41.1 ± 9.5 | 40.9 ± 11.0 | 39.5 ± 10.7 | 0.76 |

| LVESV (ml) | 93.4 ± 38.5 | 92.1 ± 36.6 | 96.3 ± 40.1 | 0.78 |

| LVEDV (ml) | 153.5 ± 45.0 | 152.1 ± 33.7 | 154.2 ± 36.9 | 0.96 |

| WMSI | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.43 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation

LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, LVESV left ventricular end-systolic volume, LVEDV left ventricular end-diastolic volume, WMSI wall motion score index

Similarly, no differences were recorded between baseline and 6 months in peak VO2 on CPET (13.3 ± 1.8 vs 14.1 ± 3.3, p = 0.37).

Clinical outcome

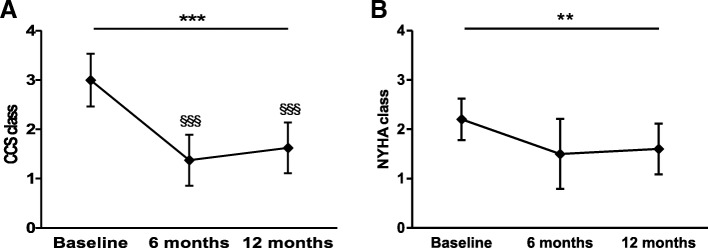

Patients’ clinical status was assessed according to CCS and NYHA classes, nitrate consumption and disease-related questionnaires at baseline and 6 and 12 months post procedure. Of importance, a significant improvement in the CCS angina class was noted during the follow-up period (p ≤ 0.001) in 8 out of 10 patients. In two diabetic patients, no angina symptoms were present at accrual. In particular, the CCS class was observed to be markedly reduced from 3.0 ± 0.5 at baseline to 1.4 ± 0.5 at 6 months (p ≤ 0.001) and to 1.6 ± 0.5 at 12 months (p ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 4a). Notably, the patient percentage showing a ≥ 2 class improvement was 50% at 6 months and 37.5% at 12 months. In parallel, the NYHA class significantly improved during the 12-month study period (n = 10, p = 0.007; Fig. 4b). Moreover, the nitrate consumption per week progressively decreased during the study period from 4 (2–7) to 0.25 (0.04–4) at 6 months and 0.04 (0–2) at 12 months (n = 7, p < 0.0001), with a significant difference in nitrate consumption at 12 months with respect to baseline (p ≤ 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Canadian Cardiovascular Society and New York Heart Association classes over 12-month follow-up. a Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class changes from 6 and 12 months to baseline (n = 8). b New York Heart Association (NYHA) class changes from 6 and 12 months to baseline (n = 10). Data presented as mean ± SD. **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. §§§p ≤ 0.001 vs baseline

In line with these results, quality-of-life perception suggested trends toward symptomatic benefit. The SF-12 survey showed an improvement of the PCS throughout the follow-up period (p = 0.02) with a significant difference in the PCS at 12 months with respect to baseline (p ≤ 0.05). Both SF-12 MCS and MLHFQ total score did not change significantly during the follow-up period (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patients’ quality of life and health status

| Parameter | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12 | ||||

| PCS | 38.4 ± 4.6 | 44.0 ± 6.7 | 44.4 ± 6.0* | 0.02 |

| MCS | 49.8 ± 9.9 | 49.5 ± 13.2 | 49.2 ± 15.2 | 0.99 |

| MLHFQ | 35.9 ± 12.2 | 27.1 ± 10.7 | 33.1 ± 18.6 | 0.29 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation

SF-12, Short Form-12, PCS Physical Component Summary, MCS Mental Component Summary, MLHFQ Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire

*p ≤ 0.05 vs baseline

ATMP-CD133 functional profile

ATMP-CD133 samples were obtained in all patients. ATMP-CD133 CPDL derived after three expansion passages varied highly among samples, ranging from 1.45 to 5.59 with a mean value of 3.32 ± 1.33. After a conditioned period of 48 h, ATMP-CD133 supernatants showed the modulation of the expression levels of several proangiogenic, proinflammatory and anti-angiogenic factors (Fig. 5). Among those tested, a large amount of proangiogenic cytokines and growth factors such as IL-8 and VEGF (1722 ± 1218 and 1293 ± 1153 pg/ml/105 cells, respectively) and, in less proportion, proinflammatory cytokines such as MCP-1 (768 ± 619 pg/ml/105 cells) were secreted. Consistently, low levels of anti-angiogenic cytokines, like LIF and IL-10, were found (13.61 ± 37.42 and 6.61 ± 10.42 pg/ml/105 cells, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Selected secreted signature of ATMP-CD133. Pro-angiogenic (green bars), pro-inflammatory (orange bars) and anti-angiogenic (red bars) factor expression levels detected in supernatants of ATMP-CD133 (n = 10). PDGF-bb platelet derived-growth factor type bb, GRO-α growth-regulated oncogene alpha, SCF stem cell factor, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, IL interleukin, RANTES regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted, MIP-1b macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta, MCP-1 monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, LIF leukemia inhibitory factor

Flow cytometry analysis at 7 days showed the expression at high levels of early endothelial markers such as CD31 (35.95 ± 16.55%) and, to a lesser extent, KDR (26.42 ± 28.13%). The expression of CD144, recognized as a terminally differentiated endothelial marker, was detectable in a minority of cells (15.58 ± 18.01%). After 14 days, CD31 and KDR expression levels decreased to 17.95 ± 18.96% and 19.71 ± 18.32%, respectively, while CD144 expression was maintained (14.04 ± 15.99%).

After 14 days under differentiation conditions, it was found that ATMP-CD133 form a number of CFU-EC which was strongly different among samples, ranging from 47 to 700 colonies/105 cells with a median of 150 (85–415). At immunofluorescence, both clustered and nonclustered cells derived from ATMP-CD133 were double-positive for Ac-LDL-Dil and UEA-1 lectin staining, confirming their endothelial commitment (Fig. 6a–e).

Fig. 6.

ATMP-CD133 in vitro endothelial differentiation. Representative immunofluorescence of a clustered and (b–e) not clustered CFU-EC derived from ATMP-CD133 after 14 days in culture. Arrows indicate ATMP-CD133 committed to endothelial lineage, double-positive for Ac-LDL-Dil (red) and UEA-1 lectin (green). UEA-1 Ulex europaeus agglutinin-1, Ac-LDL-Dil acetylated low-density lipoprotein labeled with dioctadecyl-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate

Correlation of ATMP-CD133 secretome with perfusion

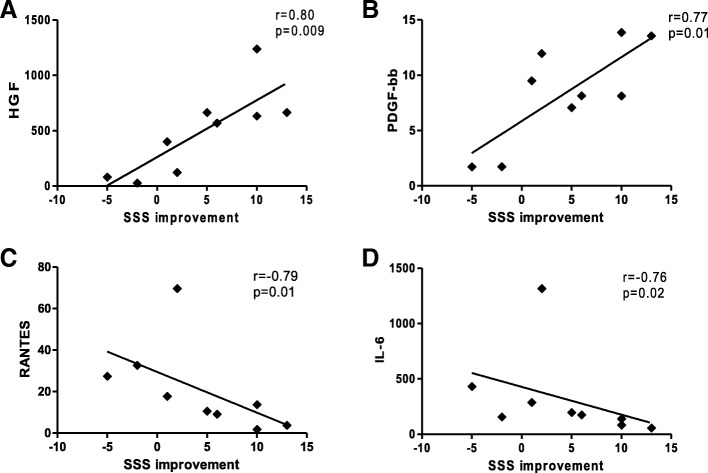

To evaluate whether the ATMP-CD133 functional profile correlates with the observed improvements in myocardial perfusion at SPECT, linear regression analyses were performed. Notably, SSS changes were found to be significantly correlated with the secreted proangiogenic growth factors HGF (r = 0.80, p = 0.009) and PDGF-bb (r = 0.77, p = 0.01; Fig. 7a, b). On the contrary, a negative significant correlation with SSS improvements was found for the proinflammatory cytokines RANTES (r = − 0.79, p = 0.01) and IL-6 (r = − 0.76, p = 0.02), as shown in Fig. 7c, d. No other correlations have been detected between myocardial perfusion changes and ATMP-CD133 functional profile.

Fig. 7.

Correlation between ATMP-CD133 secreted factors and myocardial perfusion changes at SPECT. SSS improvements correlate (a, b) positively with measured levels of proangiogenic factors and (c, d) negatively with proinflammatory factors (n = 9). SSS summed stress score, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, PDGF-bb platelet derived-growth factor type bb, RANTES regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted, IL interleukin

Discussion

The RECARDIO phase I trial was designed to evaluate safety and preliminary efficacy of transcatheter intramyocardial injections of ATMP-CD133 in patients with RA and LV dysfunction (EF ≤ 45%). The major finding of this pilot study was that LV dysfunction in highly symptomatic RA patients does not alter the positive safety profile of catheter-based intramyocardial cell delivery. Further, a favorable preliminary efficacy signal in terms of SSS and SDS improvements at SPECT between baseline and 6-month follow-up was observed. Finally, a correlation was found for the first time in the RA context between myocardial perfusion changes and the ATMP-CD133 secretome profile.

Refractory angina is a debilitating condition representing an emerging burden for health systems [2]. A recent Ontario-based study conservatively estimated the annualized cost of angina-related disability including direct, indirect and system costs at $19,209 per patient/year [1]. In this scenario, the only pharmacological therapy that has been approved for RA in the last 40 years is the late sodium current blocker ranolazine, whose effectiveness has, however, been recently questioned [25].

Of importance, CT by means of catheter-based intramyocardial cell delivery has emerged as a viable and promising therapy. Different BM or PB-derived autologous vasculogenic cell populations, including unfractioned mononuclear cells [26, 27] and positively selected CD34 [28] or CD133 [29, 30] cells, have been injected into ischemic areas to ameliorate perfusion of LV territories not otherwise amenable to revascularization. Large meta-analyses have concordantly suggested that CT has an overall favorable effect in symptom relief and exercise capacity improvement in “no option” patients with RA [12, 31, 32]. Moreover, a decreased incidence of MACE and arrhythmias in cell-treated patients has been observed [12]. Of note, the transcatheter intramyocardial approach appears to compare favorably to intracoronary infusion in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and LV dysfunction [33]. Very recently, a large patient-level pooled analysis of RCT including 304 RA patients [13] has demonstrated consistent and durable improvements in exercise capacity, angina frequency and mortality after intramyocardial injection of autologous CD34+ cells.

We and others have described CD133+ cells as an immature population of endothelial progenitors highly overlapping with CD34+ cells and having enhanced paracrine-driven proangiogenic effects [16, 34–36]. In 2015, we were the first to report the full-GMP compliant validation of BM-derived human CD133+ cells to be used as an ATMP for cardiac CT [17] in compliance with the European Medicine Agency (EMA) guidelines [37] and the Committee of Advance Therapies (CAT) recommendations [38].

In the PROGENITOR trial (Selected CD133+ Progenitor Cells to Promote Angiogenesis in Patients With Refractory Angina) [29], Jimenez-Quevedo et al. were the first to attempt NOGA-guided endocavitary intramyocardial injection of CD133+ cells mobilized from PB in RA patients. Although differences between treated and control groups were not detectable, authors were able to show a significant improvement in CCS class and in the number of angina episodes per month in the treatment arm only. Besides, at 6 months, the summed score improved significantly at rest and stress in the cell arm. On the contrary, in the more recent placebo-controlled REGENT-VSEL study (Transendocardial Delivery of Bone Marrow–Derived CD133+ Cells on Left Ventricle Perfusion and Function in Patients With Refractory Angina) [30], Wojakowski et al. did not report any significant reduction of myocardial ischemia and angina vs placebo after NOGA-guided CD133+ cell intramyocardial injection, although a mild but significant reduction of LV end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes was observed in the cell group only. Moreover, the odds ratio adjusted for confounding factors showed a 3.5-fold higher positive response at SPECT in patients allocated to the active arm vs placebo. In our RECARDIO pilot trial, the main efficacy signal was a significant intragroup improvement in perfusion at SPECT in terms of the SSS and SDS along with a reduction in the number of segments showing inducible myocardial ischemia after 6 months. Moreover, a consistent amelioration in the CCS and NYHA classes was also appreciated during the 12-month follow-up period.

Several differences have to be taken into account when interpreting such mixed results. Although both the PROGENITOR and REGENT-VSEL trials randomized RA patients vs controls/placebo, whereas the RECARDIO trial did not, these studies were underpowered to detect perfusion differences. However, additional variables may also play a major role. One of the most relevant is probably the level of the ischemic burden. Rodrigo et al. [39] identified the large number of myocardial segments at baseline as an independent predictor of a significant improvement in perfusion, and Wojakowski et al. [30] recognized that the inclusion of patients with a low number of baseline ischemic segments might have influenced their results (3.6 ± 2.7 in the REGENT-VSEL trial vs 7.3 ± 2.2 in the RECARDIO trial). Along the same line, it is likely that the higher angina class, the better the likelihood of improvement, as reflected by the nearly identical and significant 6-month reduction of CCS class that the RECARDIO and PROGENITOR studies have observed, having included patients with mean CCS ≥ 3 at baseline. It is worth mentioning that our findings of a remarkable sustained angina benefit are perfectly in line with a consistent body of previous RCT and meta-analyses confirming clinical efficacy of BM or PB intramyocardial progenitor cell injection in RA patients [13, 40, 41]. One can expect that perfusion and symptom changes may correlate with LV and patients’ functional amelioration. However, this correlation was not evenly observed in previous studies [42, 43], probably reflecting the heterogeneous nature of this patient population.

Other factors, including guidance of cell delivery and the number of injected cells, may also be taken into account to explain variability among studies. Different from the REGENT-VSEL and PROGENITOR studies, in the RECARDIO trial intramyocardial injection was fluoroscopy based rather than NOGA based. Given the difficulty of anatomical matching between injections and SPECT target areas [30], the fluoroscopy-based approach may be postulated as less accurate in targeting injections in viable ischemic areas. This limitation was partially overcome by using electroanatomical mapping to reveal the electrical properties within the area of interest and exclude segments of scar. Besides, the routine use of ICE contributed to monitoring the needle engagement into the myocardial wall [19]. Overall, in our experience, the fluoroscopy-based approach has confirmed feasibility, safety and practicality as previously reported in larger studies [44, 45]. Moreover, the unique design of the Helical Infusion Catheter has been recently proved to provide a cell retention 3-fold higher than a straight needle approach [46].

As for the cell number, even if no dose-finding studies are available for CD133+ cells in RA, we have delivered into the myocardium a mean of 6.5 × 106 CD133+ cells, a cell dosage 2-fold higher than the REGENT-VSEL study, which is the only one of the RCT in RA delivering selected CD133+ cells obtained from the BM.

Safety aspects

The specificity of our study with respect to previous ones in RA was the inclusion of patients with moderate to severe LV dysfunction (baseline EF 38.3%), a scenario that may worsen the safety of CT. Nevertheless, we have confirmed the excellent safety profile of catheter-based intramyocardial cell injection, including the absence of any treatment-emergent SAE. Our results are in line with those reported in the FOCUS-CCTRN trial in which 92 patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy were randomized to transendocardial cell vs placebo injection, without safety issues in terms of mortality and SAE at early and mid-term [47]. In particular, in our study, ILR continuous monitoring confirmed the absence up to 12 months of malignant arrhythmias. Since one of the major safety concerns of transendocardial cell delivery is cardiac tamponade due to perforation, we have routinely utilized ICE to check the real-time status of the pericardium during injections. Such an adjuvant imaging technique was not previously reported in CT studies. Moreover, the long steerable shuttle sheet (Morph) of the Helix delivery technology (BioCardia Inc.) is helpful for safely handling the injection catheter both in the case of peripheral vessel tortuosity and for crossing the aortic valve in the case of calcified cusps.

Correlations between perfusion and ATMP-CD133 secretome

In the global position paper of the TACTICS group [48], a recommendation has been made to incorporate CT mechanistic endpoints into newly designed clinical trials to corroborate unanswered hypotheses on the MoA. Since a consistent body of evidence suggests paracrine activity of angiogenic cells as the principal MoA [49], there is the need to investigate the link between cell potency and function for ATMP-CD133. To our knowledge, no such previous information is available in the RA context. Our findings correlate for the first time the ATMP-CD133 secretome profile with SSS changes, a recognized perfusion index impacting cardiac prognosis [50]. Specifically, a positive correlation with SSS improvements was found with the proangiogenic growth factors HGF and PDGF-bb, whereas the proinflammatory cytokines RANTES and IL-6 correlate negatively. Interestingly, cardiotrophic growth factors, such as HGF and PDGF-bb, have been consistently described as the main components of the paracrine MoA of BM-derived endothelial progenitors concurring to cooperative neovasculogenesis and exerting chemoattractants as well as stimulatory effects on endothelial and muscle cell growth [51–54]. Conversely and notably, RANTES has been described as a marker of refractory symptoms in plasma of patients with unstable angina [55]. Moreover, proinflammatory chemokines, as IL-6 and RANTES, have been shown to play detrimental inflammatory direct effects on the myocardium [49] as well as to impair survival and differentiation of transplanted endothelial progenitors in the ischemic heart substrate [56]. In our study, we found no correlation with other well-known cytokines related to angiogenesis and inflammation, such as VEGF, and neither we were able to dissect the exact contribution of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors (i.e., IL-6 or MCP-1) to produce the angiogenic effect. Further analyses are required on a larger sample size for a comprehensive assessment of the biological background of cell potency. Nevertheless, we can speculate that our data support the rationale for linking up a cell-specific secretion signature with a potential therapeutic benefit.

Study limitations

The RECARDIO trial is a phase I uncontrolled study, so no efficacy claims can be extrapolated. Perfusion improvements detected at SPECT must be confirmed by larger RCT. Another possible study limitation is that the ATMP-CD133 cytokine profile has been gathered from in vitro experiments, which may not fully mimic the in vivo environment. Moreover, correlations observed between cell secretome and SSS improvement have to be only considered as a proof of concept of a possible ATMP-CD133 MoA that needs further mechanistic investigations.

Conclusions

The RECARDIO trial was the first designed to address safety and preliminary efficacy of intramyocardial injection of ATMP-CD133 in the RA patient subset with LV dysfunction, and to correlate perfusion changes with CD133+ cell function. The satisfactory safety profile along with perfusion amelioration at SPECT may open larger controlled investigations in this context. Moreover, the observed link between cell function and SPECT changes hints for the first time in patients at mechanistic insights for a vasculogenic CD133+ cell MoA.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was an investigator-driven trial, partially sponsored by independent research grants from the Italian Ministry of Health (RF-2010-2321151) and the Amici del Cuore Piemonte ONLUS.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Abbreviations

- 2D

Two-dimensional

- Ac-LDL-Dil

Acetylated low-density lipoprotein labeled with dioctadecyl-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate

- AE

Adverse events

- ATMP

Advanced therapy medicinal product

- BM

Bone marrow

- CCS

Canadian Cardiovascular Society

- CFU-EC

Colony forming unit-endothelial cell

- CMR

Cardiac magnetic resonance

- CPET

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

- CT

Cell therapy

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- EF

Ejection fraction

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- FLT3LG

Flt3 ligand

- GMP

Good manufacturing practice

- GRO-α

Growth-regulated oncogene alpha

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- ICD

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator

- ICE

Intracardiac echocardiography

- IL

Interleukin

- LIF

Leukemia inhibitory factor

- LV

Left ventricle

- MACE

Major adverse cardiac events

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MCS

Mental Component Summary

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- MIP-1β

Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta

- MLHFQ

Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire

- MoA

Mode of action

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- PCS

Physical Component Summary

- PDGF-bb

Platelet-derived growth factor type bb

- RA

Refractory angina

- RANTES

Regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted

- RCT

Randomized controlled trials

- SAE

Serious adverse events

- SCF

Stem cell factor

- SDS

Summed difference score

- SF-12

Short Form-12

- SOP

Standard operative procedure

- SPECT

Gated-single photon emission computed tomography

- SRS

Summed rest score

- SSS

Summed stress score

- UAE-1

Ulex europaeus agglutinin-1

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VO2

Oxygen consumption

- WB

Washing buffer

- WMSI

Wall motion score index

Authors’ contributions

BB coordinated the study, enrolled and followed-up patients, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. CC, PA, PS and FA enrolled and treated patients. VC, SR and LB enrolled and followed-up patients. AB and MA performed gated-SPECT analysis. FC performed echocardiogram analysis. MP performed bone marrow harvest. GG and DB produced the ATMP-CD133 lots. EG performed the in vitro experiments. ER and AB analyzed the data and wrote the paper. GP conceived and designed the study, treated patients, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethical committees (CCFM225/612 and CS/154) and the Italian Competent Authority (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 15,934(13)PRE21-1199). The institutional review board at each center approved the protocol and all patients gave informed consent prior to participation. Patients were excluded in the case of denial and might withdraw from the study at any time, irrespective of the reason.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Beatrice Bassetti, Email: beatrice.bassetti@ccfm.it.

Corrado Carbucicchio, Email: corrado.carbucicchio@ccfm.it.

Valentina Catto, Email: valentina.catto@ccfm.it.

Elisa Gambini, Email: elisa.gambini@ccfm.it.

Erica Rurali, Email: erica.rurali@ccfm.it.

Alberto Bestetti, Email: alberto.bestetti@unimi.it.

Giuseppe Gaipa, Email: g.gaipa@asst-monza.it.

Daniela Belotti, Email: daniela.belotti@unimib.it.

Fabrizio Celeste, Email: fabrizio.celeste@ccfm.it.

Matteo Parma, Email: m.parma@asst-monza.it.

Stefano Righetti, Email: s.righetti@asst-monza.it.

Lorenza Biava, Email: biava.lorenza@gmail.com.

Maurizio Arosio, Email: m.arosio@asst-monza.it.

Alice Bonomi, Email: alice.bonomi@ccfm.it.

Piergiuseppe Agostoni, Email: piergiuseppe.agostoni@ccfm.it.

Paolo Scacciatella, Email: paolo.scacciatella@tin.it.

Felice Achilli, Email: felice.achilli@gmail.com.

Giulio Pompilio, Phone: +39 02-58002562, Email: giulio.pompilio@ccfm.it.

References

- 1.McGillion M, Arthur HM, Cook A, et al. Management of patients with refractory angina: Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Pain Society Joint Guidelines. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:S20–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry TD, Satran D, Jolicoeur EM. Treatment of refractory angina in patients not suitable for revascularization. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;11:78–95. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry TD, Satran D, Hodges JS, et al. Long-term survival in patients with refractory angina. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2683–2688. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Povsic TJ, Broderick S, Anstrom KJ, Shaw LK, Ohman EM, Eisenstein EL, Smith PK, Alexander JH. Predictors of long-term clinical endpoints in patients with refractory angina. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:1–12. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andréll P, Ekre O, Grip L, Währborg P, Albertsson P, Eliasson T, Jeppsson A, Mannheimer C. Fatality, morbidity and quality of life in patients with refractory angina pectoris. Int J Cardiol. 2011;147:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anavekar NS, Chareonthaitawee P, Narula J, Gersh BJ. Revascularization in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction: is the assessment of viability still viable? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2874–2887. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad M, Wan Ahmad WA, Sukmawan R, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave myocardial therapy is efficacious in improving symptoms in patients with refractory angina pectoris—a multicenter study. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26:194–200. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abawi M, Nijhoff F, Stella PR, Voskuil M, Benedetto D, Doevendans PA, Agostoni P. Safety and efficacy of a device to narrow the coronary sinus for the treatment of refractory angina: a single-centre real-world experience. Netherlands Hear J. 2016;24:544–551. doi: 10.1007/s12471-016-0862-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pompilio G, Nigro P, Bassetti B, Capogrossi MC. Bone marrow cell therapy for ischemic heart disease: the never ending story. Circ Res. 2015;117:490–493. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nigro Patrizia, Bassetti Beatrice, Cavallotti Laura, Catto Valentina, Carbucicchio Corrado, Pompilio Giulio. Cell therapy for heart disease after 15 years: Unmet expectations. Pharmacological Research. 2018;127:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassetti B, Nigro P, Catto V, Cavallotti L, Righetti S, Achilli F, Scacciatella P, Carbucicchio C, Pompilio G. Cell therapy for refractory angina: a reappraisal. Stem Cells Int. 2017:5648690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Khan AR, Farid TA, Pathan A, Tripathi A, Ghafghazi S, Wysoczynski M, Bolli R. Impact of cell therapy on myocardial perfusion and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with angina refractory to medical therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Res. 2016;118:984–993. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.308056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henry Timothy D, Losordo Douglas W, Traverse Jay H, Schatz Richard A, Jolicoeur E Marc, Schaer Gary L, Clare Robert, Chiswell Karen, White Christopher J, Fortuin F David, Kereiakes Dean J, Zeiher Andreas M, Sherman Warren, Hunt Andrea S, Povsic Thomas J. Autologous CD34+ cell therapy improves exercise capacity, angina frequency and reduces mortality in no-option refractory angina: a patient-level pooled analysis of randomized double-blinded trials. European Heart Journal. 2018;39(23):2208–2216. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassetti B, Capogrossi MC, Pompilio G. Power is nothing without control: the enduring search for the best cell in cardiac cell therapy at a crossroads. Circ Res. 2016;119:988–991. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pompilio G, Steinhoff G, Liebold A, Pesce M, Alamanni F, Capogrossi MC, Biglioli P. Direct minimally invasive intramyocardial injection of bone marrow-derived AC133+ stem cells in patients with refractory ischemia: preliminary results. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:71–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-989351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaipa G, Tilenni M, Straino S, et al. GMP-based CD133+ cells isolation maintains progenitor angiogenic properties and enhances standardization in cardiovascular cell therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1619–1634. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belotti D, Gaipa G, Bassetti B, et al. Full GMP-compliant validation of bone marrow-derived human CD133+ cells as advanced therapy medicinal product for refractory ischemic cardiomyopathy. Biomed Res Int. 2015:473159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Trachtenberg B, Velazquez DL, Williams AR, et al. Rationale and design of the transendocardial injection of autologous human cells (bone marrow or mesenchymal) in chronic ischemic left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure secondary to myocardial infarction (TAC-HFT) trial: a randomized, double-blind. Am Heart J. 2011;161:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carbucicchio C, Casella M, Catto V, Bassetti B, Bestetti A, Pompilio G. Novel application of 3-dimensional real-time cardiac imaging to guide stem cell-based therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:1073. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Germano G, Kiat H, Kavanagh PB, Moriel M, Mazzanti M, Su HT, Van Train KF, Berman DS. Automatic quantification of ejection fraction from gated myocardial perfusion SPECT. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:2138–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berman DS, Kiat H, Friedman JD, Wang FP, Van Train K, Matzer L, Maddahi J, Germano G. Separate acquisition rest thallium-201/stress technetium-99m sestamibi dual-isotope myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography: a clinical validation study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90557-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s guidelines and standards committee and the chamber quantification writing group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiograph. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin T-M, Tsai J-L, Lin S-D, Lai C-S, Chang C-C. Accelerated growth and prolonged lifespan of adipose tissue-derived human mesenchymal stem cells in a medium using reduced calcium and antioxidants. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:92–102. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fadini GP, Losordo D, Dimmeler S. Critical reevaluation of endothelial progenitor cell phenotypes for therapeutic and diagnostic use. Circ Res. 2012;110:624–637. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisz G, Généreux P, Iñiguez A, et al. Ranolazine in patients with incomplete revascularisation after percutaneous coronary intervention (RIVER-PCI): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:136–145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beeres Saskia L.M.A., Bax Jeroen J., Dibbets-Schneider Petra, Stokkel Marcel P.M., Fibbe Willem E., van der Wall Ernst E., Schalij Martin J., Atsma Douwe E. Sustained effect of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell injection in patients with refractory angina pectoris and chronic myocardial ischemia: Twelve-month follow-up results. American Heart Journal. 2006;152(4):684.e11-684.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Ramshorst J, et al. Intramyocardial bone marrow cell injection for chronic myocardial ischemia. JAMA. 2009;301:1997–2004. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Povsic TJ, Henry TD, Traverse JH, et al. The RENEW trial: efficacy and safety of intramyocardial autologous CD34+ cell administration in patients with refractory angina. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:1576–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jimenez-Quevedo P, Gonzalez-Ferrer JJ, Sabate M, et al. Selected CD133+ progenitor cells to promote angiogenesis in patients with refractory angina final results of the PROGENITOR randomized trial. Circ Res. 2014;115:950–960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wojakowski W, Jadczyk T, Michalewska-Włudarczyk A, et al. Effects of transendocardial delivery of bone marrow-derived CD133+ cells on left ventricle perfusion and function in patients with refractory angina. Circ Res. 2017;120:670–680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher SA, Doree C, Brunskill SJ, Mathur A, Martin-Rendon E. Bone marrow stem cell treatment for ischemic heart disease in patients with no option of revascularization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li N, Yang Y-J, Zhang Q, Jin C, Wang H, Qian H-Y. Stem cell therapy is a promising tool for refractory angina: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:908–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kandala J, Upadhyay GA, Pokushalov E, Wu S, Drachman DE, Singh JP. Meta-analysis of stem cell therapy in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratajczak J, Kucia M, Mierzejewska K, Marlicz W, Pietrzkowski Z, Wojakowski W, Greco NJ, Tendera M, Ratajczak MZ. Paracrine proangiopoietic effects of human umbilical cord blood-derived purified CD133+ cells—implications for stem cell therapies in regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:422–430. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bongiovanni D, Bassetti B, Gambini E, Gaipa G, Frati G, Achilli F, Scacciatella P, Carbucicchio C, Pompilio G. The CD133 + cell as advanced medicinal product for myocardial and limb ischemia. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:2403–2421. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramos AL, Darabi R, Akbarloo N, Borges L, Catanese J, Dineen SP, Brekken RA, Perlingeiro RCR. Clonal analysis reveals a common progenitor for endothelial, myeloid, and lymphoid precursors in umbilical cord blood. Circ Res. 2010;107:1460–1469. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guideline on Human Cell-Based Medicinal Products (EMEA/CHMP/410869/2006). http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003894.pdf

- 38.Reflection Paper on Stem Cell-Based Medicinal Products (EMA/CAT/571134/2009, 2011). http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2011/02/WC500101692.pdf

- 39.Rodrigo SF, Van Ramshorst J, Mann I, et al. Predictors of response to intramyocardial bone marrow cell treatment in patients with refractory angina and chronic myocardial ischemia. Int J Cardiol. 2014;175:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodrigo SF, Mann I, van Ramshorst J, Beeres SL, Zwaginga JJ, Fibbe WE, Bax JJ, Schalij MJ, Atsma DE. Safety and efficacy of percutaneous intramyocardial bone marrow cell injection for chronic myocardial ischemia: long-term results. J Interv Cardiol. 2017;30:440–447. doi: 10.1111/joic.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henry TD, Schaer GL, Traverse JH, et al. Autologous CD34+ cell therapy for refractory angina: 2-year outcomes from the ACT34-CMI study. Cell Transplant. 2016;25:1701–1711. doi: 10.3727/096368916X691484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fuchs S, Kornowski R, Weisz G, et al. Safety and feasibility of transendocardial autologous bone marrow cell transplantation in patients with advanced heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:823–829. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perin EC, Silva GV, Henry TD, et al. A randomized study of transendocardial injection of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells and cell function analysis in ischemic heart failure (FOCUS-HF) Am Heart J. 2011;161:1078–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heldman AW, DiFede DL, Fishman JE, et al. Transendocardial mesenchymal stem cells and mononuclear bone marrow cells for ischemic cardiomyopathy: the TAC-HFT randomized trial. Jama. 2014;311:62–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hare JM, Fishman JE, Gerstenblith G, et al. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by Transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Jama. 2012;308:2369. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitsutake Y, Pyun WB, Rouy D, Foo CWP, Stertzer SH, Altman P, Ikeno F. Improvement of local cell delivery using Helix transendocardial delivery catheter in a porcine heart. Int Heart J. 2017;58:435–440. doi: 10.1536/ihj.16-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perin EC, Willerson JT, Pepine CJ, et al. Effect of transendocardial delivery of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells on functional capacity, left ventricular function, and perfusion in chronic heart failure: the FOCUS-CCTRN trial. Jama. 2012;307:1717–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernández-Avilés F, Sanz-Ruiz R, Climent AM, et al. Global position paper on cardiovascular regenerative medicine. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2532–2546. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee S, Yoon YS. Revisiting cardiovascular regeneration with bone marrow-derived angiogenic and vasculogenic cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:290–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw LJ, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, Friedman J, Diamond GA. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death: differential stratification for risk of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:535–543. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kucia M, Dawn B, Hunt G, et al. Cells expressing early cardiac markers reside in the bone marrow and are mobilized into the peripheral blood after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2004;95:1191–1199. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150856.47324.5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Urbich C, Aicher A, Heeschen C, Dernbach E, Hofmann WK, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Soluble factors released by endothelial progenitor cells promote migration of endothelial cells and cardiac resident progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao R, Bråkenhielm E, Pawliuk R, Wariaro D, Post MJ, Wahlberg E, Leboulch P, Cao Y. Angiogenic synergism, vascular stability and improvement of hind-limb ischemia by a combination of PDGF-BB and FGF-2. Nat Med. 2003;9:604–613. doi: 10.1038/nm848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishikawa F, Miyazono K, Hellman U, Drexler H, Wernstedt C, Hagiwara K, Usuki K, Takaku F, Risau W, Heldin CH. Identification of angiogenic activity and the cloning and expression of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor. Nature. 1989;338:557–562. doi: 10.1038/338557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kraaijeveld AO, De Jager SCA, De Jager WJ, et al. CC chemokine ligand-5 (CCL5/RANTES) and CC chemokine ligand-18 (CCL18/PARC) are specific markers of refractory unstable angina pectoris and are transiently raised during severe ischemic symptoms. Circulation. 2007;116:1931–1941. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawamoto A, Iwasaki H, Kusano K, et al. CD34-positive cells exhibit increased potency and safety for therapeutic neovascularization after myocardial infarction compared with total mononuclear cells. Circulation. 2006;114:2163–2169. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact author for data requests.