Abstract

Rationale: Mucins are essential for airway defense against bacteria. We hypothesized that abnormal secreted airway mucin levels would be associated with bacterial colonization in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Objectives: To investigate the relationship between mucin levels and the presence of potentially pathogenic micro-organisms in the airways of stable patients with severe COPD

Methods: Clinically stable patients with severe COPD were examined prospectively. All patients underwent a computerized tomography scan, lung function tests, induced sputum collection, and bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and protected specimen brush. Patients with bronchiectasis were excluded. Secreted mucins (MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC5B) and inflammatory markers were assessed in BAL and sputum by ELISA.

Measurements and Main Results: We enrolled 45 patients, with mean age (±SD) of 67 (±8) years and mean FEV1 of 41 (±10) % predicted. A total of 31% (n = 14) of patients had potentially pathogenic micro-organisms in quantitative bacterial cultures of samples obtained by protected specimen brush. Patients with COPD with positive cultures had lower levels of MUC2 both in BAL (P = 0.02) and in sputum (P = 0.01). No differences in MUC5B or MUC5AC levels were observed among the groups. Lower MUC2 levels were correlated with lower FEV1 (r = 0.32, P = 0.04) and higher sputum IL-6 (r = −0.40, P = 0.01).

Conclusions: Airway MUC2 levels are decreased in patients with severe COPD colonized by potentially pathogenic micro-organisms. These findings may indicate one of the mechanisms underlying airway colonization in patients with severe COPD.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01976117).

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, mucins, airway infection, airway inflammation

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity, mortality, and resource use worldwide (1). Potentially pathogenic micro-organisms (PPMs) can be isolated from airway secretions in about 30–50% of clinically stable patients with severe COPD (2, 3). This bacterial colonization is associated with increased neutrophil-mediated airway inflammation (4, 5) and more frequent and severe episodes of acute exacerbation of COPD (6). Therefore, airway bacterial colonization plays an important negative role in the clinical course of the disease (7, 8).

Pathogenesis of airway bacterial colonization in COPD is poorly understood. One of the features of COPD is chronic hypersecretion of mucus, which is related to increased risk of airway infection (9, 10). Mucus is composed of water, salt, and proteins. The major macromolecular components of mucus are proteins called mucins (11, 12). Experimental studies have demonstrated that mucin secretion is required for defense against bacterial infections, linking mucin deficiency with chronic airway infections (13).

Several mucins have been described in the lower respiratory tract (14, 15), although mucin (MUC) 5AC, MUC5B, and MUC2 are the major secreted mucins detected in the airways from healthy individuals (16, 17). In moderate COPD, increases of MUC5AC and MUC5B have been detected compared with nonsmokers and smokers without airway obstruction (18, 19), although these findings have not been related to airway infection. In non–cystic fibrosis (CF) bronchiectasis, elevated MUC2 levels were found to be related to the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and severe disease (20). However, no data regarding the role of mucins and its relationship with airway bacterial infection in COPD are available.

We postulated that mucin levels are protective against airway infection in COPD. Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess the association of airway mucin levels and airway bacterial colonization among patients with severe stable COPD.

Methods

Study Design and Ethics

This was a prospective cross-sectional study that included clinically stable patients with severe COPD with and without airway bacterial colonization (n = 14 and n = 31, respectively). The institutional review board (IIBSP-MUC-200920) approved the study protocol, and all subjects gave signed, informed consent to participate in the study.

Participants

Patients were consecutively recruited from a specialist clinic at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain). The diagnosis of COPD was established according to the GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) recommendations (1), and included patients with GOLD stages C and D. All participants were clinically stable, as defined by the absence of an exacerbation that required antibiotic or steroid treatment within 30 days before inclusion. All patients underwent a computerized tomography scan, and those with bronchiectasis, lung cancer, pneumonia, and/or interstitial lung diseases were excluded. Patients with active malignant disease and/or any type of immunosuppression were also excluded.

Clinical and Functional Characterization

Demographic data, number of exacerbations in the previous year, time from last exacerbation, relevant comorbid conditions, and current treatments were recorded at inclusion using standardized questionnaires. Spirometry (Datospir-600; Sibelmed SA, Barcelona, Spain) was performed according to the Spanish Respiratory Society guidelines (21), using the predicted values for Mediterranean populations (22).

Microbiological Evaluation

The presence of airway colonization was determined by quantitative microbiological cultures obtained using a protected specimen brush (PSB). PSB samples were obtained from right intermedius bronchus using a flexible bronchoscope and processed using standard methodology. Samples were processed for qualitative and quantitative bacteriology, as previously described (23). Bacterial load was considered significant when it reached 102 colony-forming units/ml or greater (24).

Mucins Measurement

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples were recovered using 150-ml saline lavage with the bronchoscope wedged in the right middle lobe. Induced sputum was collected as previously described (25). Induced sputum was collected just before the bronchoscopy in all patients. BAL and induced sputum were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 10°C. Proteases inhibitors (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) were added to the samples during thawing.

MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC5B were measured by validated, commercially available ELISA kits (USCN Life Science Inc., Wuhan, China), as we previously described (20)

Inflammatory Markers

IL-6 was measured in sputum by ELISA (R&D Systems, Abington, UK). α1 defensin was also measured in BAL and sputum by ELISA (BlueGene, Shangai, China)

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 17.0 software program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Results are presented as mean (±SD or SEM, as indicated) and frequency or percentage, as required. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t test and ANOVA, whereas categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 tests. Mucin levels, airway inflammation, bacterial load, smoking status, tobacco habit (packs/year), and lung function were correlated by linear regression. Nonparametric tests were used when necessary. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 45 patients with stable severe COPD were included in the study. Median age (± SD) was 67 (±8) years, and median FEV1 was 41 (±10) % predicted; 37 of them (82%) were male, and 16 (35%) were current smokers. A total of 14 (31%) patients with stable, severe COPD had PPMs determined by PSB and were considered colonized.

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the subjects, grouped according to the presence or absence of airway bacterial colonization. There were no statistically significant differences in sex, age, smoking status, lung function tests, pre-existing comorbid conditions, or prior medications used among groups. Patients with COPD with bacterial colonization had a higher rate of frequent exacerbations (P = 0.02) and shorter time from last exacerbation (P = 0.03)

Table 1.

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbid conditions, and prior treatments among colonized and noncolonized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

| Variables | Colonized(n = 14) | Noncolonized (n = 31) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 68.7 ± 10.8 | 66.4 ± 7.3 | 0.07 |

| Male/female, n | 11/3 | 26/5 | 0.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.1 ± 5.0 | 26.0 ± 3.9 | 0.3 |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Smoker/ ex-smoker, n | 5/9 | 11/20 | 0.6 |

| Pack-years | 59.4 ± 24.8 | 52.0 ± 17.5 | 0.3 |

| Chronic cardiac disease, n (%) | 3 (21.4) | 9 (29.0) | 0.5 |

| Prior malignancy, n (%) | 2 (14.3) | 5 (16.1) | 0.8 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 0.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 4 (28.6) | 4 (12.9) | 0.2 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 8 (57.1) | 17 (54.8) | 0.8 |

| Depression, n (%) | 2 (14.3) | 9 (29.0) | 0.2 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (3.2) | 0.5 |

| Functional status | |||

| FEV1, L | 1.1 ± 0.31 | 1.3 ± 0.44 | 0.1 |

| FEV1, % | 37.2 ± 7.8 | 43.1 ± 10.7 | 0.2 |

| Frequent exacerbator, n (%)* | 7 (50.0) | 5 (16.1) | 0.02 |

| Time from last exacerbation, wk | 12.7 ± 4.7 | 21.8 ± 14.4 | 0.03 |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| ICS | 12 (85.7) | 30 (96.8) | 0.1 |

| LABA | 14 (100) | 30 (96.8) | 0.4 |

| LAMA | 12 (85.7) | 27 (87.0) | 0.8 |

| Roflumilast | 1 (7.1) | 2 (6.5) | 0.9 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; ICS = inhaled corticosteroids; LABA = long-acting β-agonist; LAMA = long-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Frequent exacerbator (≥two acute exacerbations in the last 12 mo).

Microbiology

Table 2 shows the identified PPMs and the bacterial load in PSB specimens. The most common pathogen collected from these patients with stable severe COPD were Haemophilus influenzae (n = 8), followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 2), Moraxella catarrhalis (n = 2), Neisseria meningitidis (n = 1), and Escherichia coli (n = 1), respectively. All colonized patients had only one species of PPMs in their PSB samples.

Table 2.

Potentially pathogenic micro-organisms and bacterial load isolated in protected specimen brush samples

| Potentially Pathogenic Micro-organisms | n (%)* | ≥102 CFU/ml n (%) | ≥103 CFU/ml n (%) | ≥104 CFU/ml n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemophilus influenzae | 8 (57) | 1 (12) | 7 (88) | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 2 (14) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 2 (14) | 2 (100) | ||

| Neisseria meningitidis | 1 (7) | 1 (100) | ||

| Escherichia coli | 1 (7) | 1 (100) |

Definition of abbreviation: CFU = colony-forming units.

% refers to the total number of micro-organisms.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Mucin Levels

MUC2 was the secreted mucin with the highest expression in the BAL, with a mean (SD) of 8.1 (±4.4) ng/ml. MUC5AC levels were 80.3 (±11.2) pg/ml and MUC5B levels were 6.4 (±4.0) ng/ml.

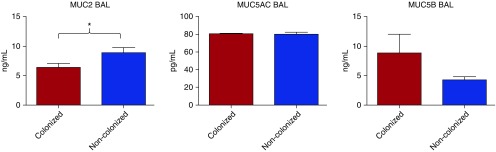

Stable patients with severe COPD and airway bacterial colonization had lower BAL MUC2 levels compared with those with no airway bacterial colonization (6.3 ± 1.3 vs. 8.9 ± 4.9 ng/ml, P = 0.02). No differences related to airway bacterial colonization status were observed for BAL MUC5AC levels (80.3 ± 4.3 vs. 80.3 ± 13.0 pg/ml, P = 0.9) and BAL MUC5B levels (8.8 ± 10.8 vs. 4.2 ± 3.0 ng/ml, P = 0.1), respectively (Figure 1). No differences among BAL mucin levels and type of PPMs were found.

Figure 1.

Mucin (MUC) 2, MUC5AC, and MUC5B bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) levels in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) colonized and noncolonized by potentially pathogenic micro-organisms. Data are presented as median (±SEM). *P < 0.05.

Sputum Mucin Levels

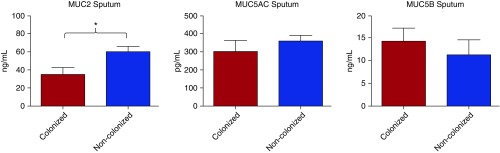

MUC2 was also the secreted mucin with highest expression in the sputum, with a mean (SD) of 52.4 (±32.8) ng/ml, followed by MUC5B (12.2 ng/ml [±14.9]) and MUC5AC (674.2 pg/ml [±179.1]), respectively. Similar to BAL results, only low sputum MUC2 levels were associated with airway bacterial colonization among stable patients with severe COPD (34.7 ± 28.0 vs. 59.9 ± 30.0 ng/ml, P = 0.01). There were no differences in sputum MUC5AC levels (304.3 ± 114.4 vs. 360.1 ± 159.1 pg/ml, P = 0.5) and sputum MUC5B levels (14.2 ± 10.5 vs. 11.1 ± 6.9 ng/ml, P = 0.5) among colonized and noncolonized patients with stable severe COPD (Figure 2). There were no differences among sputum mucin levels and type of PPM.

Figure 2.

Mucin (MUC) 2, MUC5AC, and MUC5B sputum levels in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) colonized and noncolonized by potentially pathogenic micro-organisms. Data are presented as median (±SEM). *P < 0.05.

A positive correlation was identified among MUC2 (r = 0.34, P = 0.03) and MUC5AC (r = 0.14, P = 0.02) sputum and BAL mucin samples from stable patients with severe COPD.

Inflammatory Markers

Sputum IL-6 and α1 defensin levels were higher in colonized patients compared with noncolonized patients (1,948.5 ± 476.7 vs. 389.1 ± 127.2 ng/ml, P < 0.001 and 1,244.4 ± 250.2 vs. 498.8 ± 153.6 pg/ml, P = 0.01, respectively). BAL α1 defensin levels were also higher in colonized patients, although differences were not statistically significant (143.2 ± 33.2 vs. 101.1 ± 12.2 pg/ml, P = 0.2).

Relationship between Mucin Levels and Lung Function and Airway Inflammation

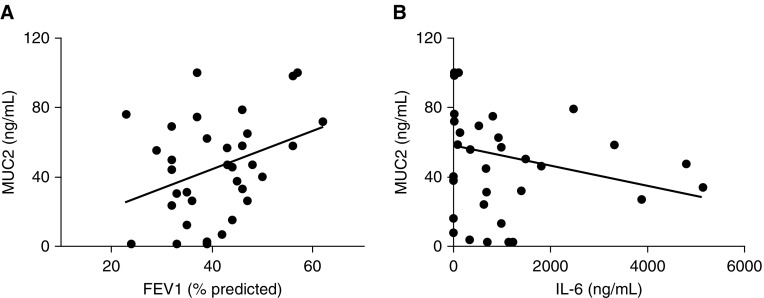

A direct relationship among sputum MUC2 levels and FEV1 % predicted was found (r = 0.355, P = 0.04; Figure 3A). In addition, there was a significant negative correlation between levels of MUC2 and IL-6 levels in sputum (r = −0.40, P = 0.01; Figure 3B). We found no other significant correlations among other mucin levels and inflammatory markers, including α1 defensin. No correlation between mucin levels and airway bacterial load or smoking status was found.

Figure 3.

Relationship between (A) mucin (MUC) 2 sputum levels and FEV1 % predicted and (B) sputum IL-6 levels.

Discussion

Low levels of airway MUC2 were associated with bacterial colonization and the presence of increased airway inflammation in patients with severe COPD. Although, in a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to determine whether decreased MUC2 is a cause or a consequence of airway infection, in view of the experimental data published by Roy and colleagues (13) and others, these findings suggest a specific role for MUC2 in the pathogenesis of airway bacterial colonization in severe COPD. No differences in other airway-secreted mucins were found.

Mucins are proteins produced by respiratory epithelial cells essential for appropriate airway mucus formation (26, 27). Patients with COPD, especially those with chronic bronchitis, have increased mucus secretion (28). This mucus hypersecretion has been associated with an accelerated lung function decline and increased risk of exacerbations (9, 10, 29). Although it has been speculated that mucus hypersecretion is important in the pathogenesis of COPD, there are few data evaluating mucus properties in these patients. In our study, MUC2 was the predominant airway-secreted mucin both in BAL and in the sputum from patients with severe COPD, followed by MUC5B and MUC5AC.

Previous studies in asthma (16), CF (30–32), and chronic bronchitis (33) demonstrated higher levels of MUC5AC and MUC5B than MUC2. In COPD, Kirkham and colleagues (19) demonstrated that MUC5B was the major mucin in sputum in moderate patients with COPD as compared with smokers without airway obstruction. In this study, sputum with increased amount of MUC5B correlated with lower FEV1. In our study, lower sputum MUC2 values correlate with lower FEV1. Caramori and colleagues (18) demonstrated that MUC5AC expression was increased in bronchial submucosal glands of patients with stable moderate COPD. Recently, Chillappagari and colleagues (34) showed higher levels of MUC5AC and MUC5B in sputum of subjects with moderate to severe COPD during a periexacerbation period compared with control subjects.

All of these findings suggest that the expression of airway-secreted mucins are altered in COPD and may be related to disease severity (especially to lung function) and clinical situation (stability or exacerbation). In addition, as has previously been emphasized (35), COPD has a different pathogenesis and different airway inflammatory profile to other chronic airway diseases. Specific roles of mucin subtypes and the impact of external stimuli (such as airway infection) in different airway diseases will require further study.

Bacterial colonization plays an important role in the pathogenesis and course of COPD (36). Chronic airway infection increases airway inflammation and leads to further impairment of local host defense (4, 5, 37). Several studies have demonstrated that patients with COPD with airway colonization by PPMs had worse clinical outcomes (6, 10).

The reasons why some patients with COPD become colonized are not well established. Mucins have been postulated as natural antimicrobial agents (17). In the gastrointestinal tract, mucins have demonstrated an antibiotic function against Helicobacter pylori (38), but few data are available regarding the relationship between mucin expression and airway infection. Recent experimental studies have demonstrated the crucial role of MUC5B as an airway defense mechanism (13).

In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a polymorphism of the MUC5B gene has been associated with increased airway bacterial burden and risk of death (39). In patients with non-CF bronchiectasis, a recent study showed that stable patients with airway bacterial colonization had higher levels of sputum MUC2, especially those colonized with P. aeruginosa (20). In our study, we found that patients colonized by PPMs, primarily by H. influenzae, expressed lower levels of airway MUC2 in the airway from BAL and sputum samples compared with patients without airway bacterial colonization. These findings may suggest a specific role for MUC2 in the response to bacterial infection that may be airway disease specific and modulated by specific bacterial pathogens. In COPD, the presence of MUC2 might be protective against bacterial colonization, mainly due to H. influenzae.

Factors that influence mucin secretion may be a key to understanding these findings. Different studies have demonstrated that mucin secretion is regulated in relation to several factors, such as bacterial products (39) and inflammatory cytokines (40). MUC2 gene is up-regulated in vitro by inflammatory mediators present in the airway secretions of patients with chronic lung disease (12). However, using human bronchial epithelial cells, Fujisawa and colleagues (41) demonstrated that mucin expression is stimulated by inflammatory cytokines in a time- and dose-dependent manner. These authors showed that the persistence of inflammatory stimulus over time or the presence of excessive inflammation (both features present in most patients with severe COPD) inhibits mucin induction (41). These findings are consistent with our study, in which we found that higher airway inflammation (detected by IL-6 levels) in patients with COPD were correlated with lower MUC2 levels. This observation may have important biological consequences, suggesting that those patients with severe COPD with elevated and persistent airway inflammation are those with lower MUC2 levels. No relationship among mucin levels and other factors that potentially may influence mucin secretion, such as airway bacterial load or current smoking, were found. Further studies are needed to interpret this complex pathway, which may contribute to a better understanding of the role of secreted mucins as natural antimicrobial agents in the airways of patients with COPD.

The strengths of our study include the use of gold standard bronchoscopic PPM identification with PSB quantitative microbiological cultures (24). In addition, the careful selection of stable patients with severe COPD without bronchiectasis or other structural lung diseases, as determined by computerized tomography scan, strengthen the validity of the results.

Our study also has limitations. First, although our sample size was larger than those previously reported in other studies of airway mucins in patients with COPD (16, 19), asthma (16), and CF (30–32), it was still small enough to limit the strength and generalizability of the results. Second, a control group was not included, and it might have informed the normal expression of mucin levels in patients without COPD. Third, we did not assess several other factors that may influence mucin secretion, such as specific microbiological properties, pattern recognition receptors, airway cell counts, or neutrophil activity. Fourth, previous studies have suggested concerns about accurate measurements of MUC2 (12), indicating that some results should be considered with caution. Finally, although the differences we observed were clearly statistically significant, we do not know enough about the biology of specific mucin subtypes in the airway to determine the minimum clinically important difference in airway mucin levels. Further studies correlating mucin levels with clinical outcomes are needed.

In conclusion, we found that airway MUC2 levels are decreased in patients with severe COPD with bacterial colonization, which is related to higher airway inflammation. These observations may suggest that secreted mucins play a role in determining the presence of airway bacterial colonization in stable severe COPD. This justifies a larger, more detailed investigation of the role of mucins in airway defense in patients with COPD.

Footnotes

Supported by Sociedad Española de Neumología, Fundació Catalana de Pneumologia, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III grant FIS PI 09/2567; M.I.R. is partially funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute award K23HL096054.

Author Contributions: all authors have given their final approval of the manuscript. O.S. is the guarantor of the study, coordinated all the steps, including study design, obtaining funding, coordinating acquisition of data, and preparation of the manuscript, and had full access to the data and will vouch for the integrity of the data analysis; L.G.-B. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript; J.G., A.R.-T., G.S.-C., D.C., and I.S. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; A.T., S.V., and F.S.-R. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, and preparation of the manuscript; E.F.M. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data; E.S. and B.G.C. contributed to the design of the study; M.I.R., A.A., and J.D.C. contributed to the interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript; V.P. contributed to the study design, interpretation of the data, and preparation of the manuscript.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ, Nishimura M, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monsó E, Ruiz J, Rosell A, Manterola J, Fiz J, Morera J, Ausina V. Bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a study of stable and exacerbated outpatients using the protected specimen brush. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1316–1320. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.4.7551388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zalacain R, Sobradillo V, Amilibia J, Barrón J, Achótegui V, Pijoan JI, Llorente JL. Predisposing factors to bacterial colonization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:343–348. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13b21.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill AT, Campbell EJ, Hill SL, Bayley DL, Stockley RA. Association between airway bacterial load and markers of airway inflammation in patients with stable chronic bronchitis. Am J Med. 2000;109:288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethi S, Maloney J, Grove L, Wrona C, Berenson CS. Airway inflammation and bronchial bacterial colonization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:991–998. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1525OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel IS, Seemungal TA, Wilks M, Lloyd-Owen SJ, Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between bacterial colonisation and the frequency, character, and severity of COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2002;57:759–764. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.9.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Patel IS, Bhowmik A, Wilkinson TM, Hurst JR, MacCallum PK, Wedzicha JA. Airway and systemic inflammation and decline in lung function in patients with COPD. 2005. Chest. 2009;136(5) suppl:e30. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soler-Cataluña JJ, Martínez-García MA, Román Sánchez P, Salcedo E, Navarro M, Ochando R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60:925–931. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.040527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prescott E, Lange P, Vestbo J. Chronic mucus hypersecretion in COPD and death from pulmonary infection. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1333–1338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08081333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dekker J, Rossen JW, Büller HA, Einerhand AW. The MUC family: an obituary. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:126–131. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:245–278. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy MG, Livraghi-Butrico A, Fletcher AA, McElwee MM, Evans SE, Boerner RM, Alexander SN, Bellinghausen LK, Song AS, Petrova YM, et al. Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature. 2014;505:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose MC, Nickola TJ, Voynow JA. Airway mucus obstruction: mucin glycoproteins, MUC gene regulation and goblet cell hyperplasia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:533–537. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.f218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornton DJ, Carlstedt I, Howard M, Devine PL, Price MR, Sheehan JK. Respiratory mucins: identification of core proteins and glycoforms. Biochem J. 1996;316:967–975. doi: 10.1042/bj3160967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkham S, Sheehan JK, Knight D, Richardson PS, Thornton DJ. Heterogeneity of airways mucus: variations in the amounts and glycoforms of the major oligomeric mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B. Biochem J. 2002;361:537–546. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voynow JA, Rubin BK. Mucins, mucus, and sputum. Chest. 2009;135:505–512. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caramori G, Casolari P, Di Gregorio C, Saetta M, Baraldo S, Boschetto P, Ito K, Fabbri LM, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM, et al. MUC5AC expression is increased in bronchial submucosal glands of stable COPD patients. Histopathology. 2009;55:321–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkham S, Kolsum U, Rousseau K, Singh D, Vestbo J, Thornton DJ. MUC5B is the major mucin in the gel phase of sputum in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1033–1039. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-391OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sibila O, Suarez-Cuartin G, Rodrigo-Troyano A, Fardon TC, Finch S, Mateus EF, Garcia-Bellmunt L, Castillo D, Vidal S, Sanchez-Reus F, et al. Secreted mucins and airway bacterial colonization in non-CF bronchiectasis. Respirology. 2015;20:1082–1088. doi: 10.1111/resp.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García-Río F, Calle M, Burgos F, Casan P, Del Campo F, Galdiz JB, Giner J, González-Mangado N, Ortega F, Puente Maestu L Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) Spirometry. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49:388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castellsagué J, Burgos F, Sunyer J, Barberà JA, Roca J. Prediction equations for forced spirometry from European origin populations. Barcelona Collaborative Group on Reference Values for Pulmonary Function Testing and the Spanish Group of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Respir Med. 1998;92:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sibila O, Garcia-Bellmunt L, Giner J, Merino JL, Suarez-Cuartin G, Torrego A, Solanes I, Castillo D, Valera JL, Cosio BG, et al. Identification of airway bacterial colonization by an electronic nose in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2014;108:1608–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soler N, Agustí C, Angrill J, Puig De la Bellacasa J, Torres A. Bronchoscopic validation of the significance of sputum purulence in severe exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2007;62:29–35. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vidal S, Bellido-Casado J, Granel C, Crespo A, Plaza V, Juárez C. Flow cytometry analysis of leukocytes in induced sputum from asthmatic patients. Immunobiology. 2012;217:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buisine MP, Devisme L, Copin MC, Durand-Réville M, Gosselin B, Aubert JP, Porchet N. Developmental mucin gene expression in the human respiratory tract. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:209–218. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.2.3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim V, Han MK, Vance GB, Make BJ, Newell JD, Hokanson JE, Hersh CP, Stinson D, Silverman EK, Criner GJ COPDGene Investigators. The chronic bronchitic phenotype of COPD: an analysis of the COPDGene Study. Chest. 2011;140:626–633. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1530–1535. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies JR, Svitacheva N, Lannefors L, Kornfält R, Carlstedt I. Identification of MUC5B, MUC5AC and small amounts of MUC2 mucins in cystic fibrosis airway secretions. Biochem J. 1999;344:321–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henke MO, Renner A, Huber RM, Seeds MC, Rubin BK. MUC5AC and MUC5B mucins are decreased in cystic fibrosis airway secretions. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:86–91. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0345OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henke MO, John G, Germann M, Lindemann H, Rubin BK. MUC5AC and MUC5B mucins increase in cystic fibrosis airway secretions during pulmonary exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:816–821. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-1011OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hovenberg HW, Davies JR, Herrmann A, Lindén CJ, Carlstedt I. MUC5AC, but not MUC2, is a prominent mucin in respiratory secretions. Glycoconj J. 1996;13:839–847. doi: 10.1007/BF00702348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chillappagari S, Preuss J, Licht S, Müller C, Mahavadi P, Sarode G, Vogelmeier C, Guenther A, Nahrlich L, Rubin BK, et al. Altered protease and antiprotease balance during a COPD exacerbation contributes to mucus obstruction. Respir Res. 2015;16:85. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Postma DS, Reddel HK, ten Hacken NH, van den Berge M. Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: similarities and differences. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2355–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Donnell RA, Peebles C, Ward JA, Daraker A, Angco G, Broberg P, Pierrou S, Lund J, Holgate ST, Davies DE, et al. Relationship between peripheral airway dysfunction, airway obstruction, and neutrophilic inflammation in COPD. Thorax. 2004;59:837–842. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molyneaux PL, Cox MJ, Willis-Owen SA, Mallia P, Russell KE, Russell AM, Murphy E, Johnston SL, Schwartz DA, Wells AU, et al. The role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:906–913. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0541OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li D, Gallup M, Fan N, Szymkowski DE, Basbaum CB. Cloning of the amino-terminal and 5′-flanking region of the human MUC5AC mucin gene and transcriptional up-regulation by bacterial exoproducts. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6812–6820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levine SJ, Larivée P, Logun C, Angus CW, Ognibene FP, Shelhamer JH. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces mucin hypersecretion and MUC-2 gene expression by human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;12:196–204. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.12.2.7865217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujisawa T, Chang MM, Velichko S, Thai P, Hung LY, Huang F, Phuong N, Chen Y, Wu R. NF-κB mediates IL-1β- and IL-17A-induced MUC5B expression in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:246–252. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0313OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]