Abstract

Context:

The constructs of job satisfaction and career intentions in athletic training have been examined predominantly via unilevel assessment. The work-life interface is complex, and with troubling data regarding attrition, job satisfaction and career intentions should be examined via a multilevel model. Currently, no known multilevel model of career intentions and job satisfaction exists within athletic training.

Objective:

To validate a multilevel model of career intentions and job satisfaction among a collegiate athletic trainer population.

Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Setting:

Web-based questionnaire.

Patients or Other Participants:

Athletic trainers employed in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I, II, or III or a National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics college or university (N = 299; 56.5% female, 43.5% male). The average age of participants was 34 ± 8.0 years, and average experience as an athletic trainer was 10.0 ± 8 years.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

A demographic questionnaire and 7 Likert-scale survey instruments were administered. Variables were responses related to work-family conflict, work-family enrichment, work-time control, perceived organizational family support, perceived supervisor family support, professional identity and values, and attitude toward women.

Results:

Exploratory factor analysis confirmed 3 subscales: (1) individual factors, (2) organizational factors, and (3) sociocultural factors. The scale was reduced from 88 to 62 items. A Cronbach α of 0.92 indicated excellent internal consistency.

Conclusions:

A multilevel examination highlighting individual, organizational, and sociocultural factors is a valid and reliable measure of job satisfaction and career identity among athletic trainers employed in the collegiate setting.

Key Words: organizational climate, gender, family values

Key Points

Job satisfaction and career intentions within athletic training can be more thoroughly examined via a multilevel approach.

Individual-, organizational-, and sociocultural-level factors should be included in an assessment of the job satisfaction and career intentions of athletic trainers.

This model would benefit from continued examination and may ultimately be used to better understand outcomes of the work-life interface.

Literature on the work-life interface has increased over the last decade, particularly in the sport industry, with the frequent expectation that athletic trainers (ATs) be available “24/7,” as well as the perception that success and commitment are linked to hours worked and time spent working.1 We know that work-life conflict may cause job dissatisfaction,2 which in turn leads to a desire to depart the profession. Indeed, the relationship between work-life conflict and career intentions has been well established. As levels of conflict rise, so do dissatisfaction and thoughts of leaving one's job or profession.3 Empirical and anecdotal discussions within athletic training have often focused on the burden long hours can place on the AT, which in turn may lead to departure.4,5

Traditionally authors of the work-life interface literature have examined constructs unidimensionally, from an individual, organizational, or sociocultural perspective.6–8 Individual factor analysis focuses on a person's preferences, personality, family structure, and gender. Organizational factor analysis examines organizational culture, work hours and scheduling, and job stresses. And sociocultural factor analysis studies the effects of gender ideology and cultural norms and expectations. However, Kozlowski and Klein9 contended that examining factors at multiple levels is important for creating a more complete and integrated understanding of organizational and individual behavior and outcomes. The value of a multilevel perspective is in gaining a better understanding of how to explain and solve problems by viewing them more globally.

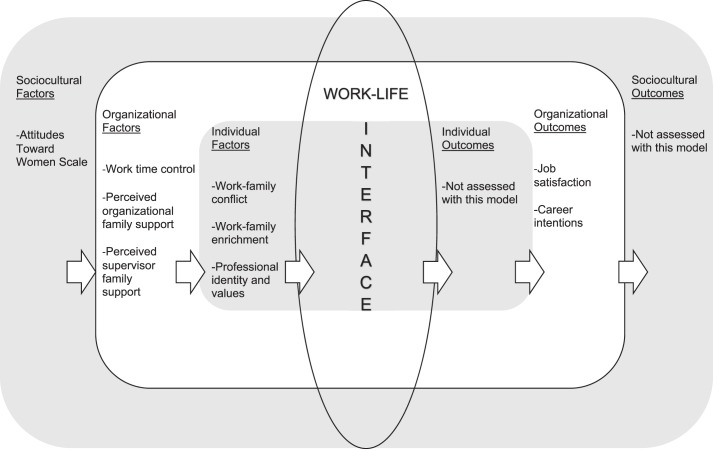

Our study was inspired by the work of Dixon and Bruening,10 who developed a multilevel framework of the work-life interface among female collegiate coaches. Although coaching and athletic training are immensely different professions, Dixon and Bruening10 were the first to examine the work-life interface from a multilevel perspective within athletics and therefore provide a foundational theory for examining the work-life interface from that perspective. Dixon and Bruening10 qualitatively examined interactions at distinct levels, which revealed sociocultural, organizational, and individual factors that can positively or negatively influence the perceptions and consequences of work-life conflict.

The Dixon and Bruening10 model examined coaches, yet athletic training as a profession is unique in that it is a health care profession often operating within a sport organization. In the collegiate setting, athletic training departmental goals focus on improving the health and well-being of patients, whereas the workplace goals of coaches and sports organizations may focus more on success and profit. Additionally, ATs in many employment settings, unlike coaches, have little control over their schedules and must adapt to others making and changing schedules. The collegiate and university setting is an environment full of unique workplace challenges, particularly for the AT. Challenges specific to the AT working in the collegiate or university clinical setting include odd hours, long road trips resulting in nights away from home, pressure to win, supervision of athletic training students, long competition seasons, last-minute schedule changes, and organizational structures in which supervisors may not be medical professionals.5,11,12

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to complete initial validation of a multilevel model of the work-life interface among a collegiate AT population. Specifically, we used the Dixon and Bruening10 multilevel model, which identified 3 levels contributing to the work-life interface, as a theoretical foundation. Our goal was to examine factors at multiple levels within athletic training to identify interactions that assist in creating retention strategies.

METHODS

Procedures

After receiving institutional review board approval, we contacted the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) to obtain contact information for ATs self-identified as currently employed in the collegiate or university setting. We were provided a list of 2000 e-mail addresses, 1653 of which were viable (for the others, either the e-mail addresses were inactive or the individuals replied to let us know they did not meet the inclusion criteria). The initial recruitment e-mail, including an overview of the study and a link to the online survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT), was sent in mid-November 2015. We e-mailed reminders to participants requesting survey completion at 2 and 4 weeks after initial recruitment. The online survey consisted of demographic questions, 7 Likert-scale survey instruments, and open-ended questions. This study was part of a larger investigation13 that aimed to examine the work-life interface of collegiate ATs from a multilevel perspective via a mixed-methods study design.

Participants

The inclusion criterion was employment in the collegiate or university setting. Participants were excluded from the study if they were graduate assistant or intern ATs. Athletic trainers employed in the college or university setting were purposefully recruited because of the specific organizational challenges they encountered and because they represented the largest population of NATA members.14 A total of 299 surveys were completed (18.1% response rate).

Measures

Demographic Form

The 22-item demographic form requested general demographic information and information specific to the athletic training profession.

Multilevel Factors

To examine factors at multiple levels, we carefully selected 7 previously validated survey instruments that assessed our preselected factors. Additionally, for a study of athletic trainers, it was important to select survey instruments that measured specific factors at the individual level as opposed to a departmental level. To measure individual-level factors, we selected a work-family conflict scale,15 a work-family enrichment scale,16 and a modified version of the Professional Identity and Values Scale.17,18 To measure organizational factors, we selected a work-time control scale,19 the Perceived Organizational Family Support scale,20 and the Perceived Supervisory Family Support scale.20 Lastly, to measure sociocultural factors, we selected the shortened Attitudes Toward Women scale.21 The original and current Cronbach α statistics for each questionnaire are listed in Table 1. Reliability scores for this study ranged between 0.69 and 0.92. Table 2 provides a summary of each individual Likert-survey instrument, the number of anchors, and its corresponding factor level. Each of the 7 original Likert-scale instruments was included in our survey in its entirety; the survey consisted of 88 questions in total.

Table 1.

Reliability Scores of Validated Survey Instruments (α Values)

| Questionnaire Component |

Previous Studies |

Current Study |

| Worktime Control Scale | 0.86 | 0.82 |

| Perceived Organizational Family Support Scale | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| Perceived Supervisory Family Support Scale | 0.63–0.93 | 0.96 |

| Work-Family Conflict Survey | 0.85 | 0.69 |

| Work-Family Enrichment Scale | 0.64–0.86 | 0.78 |

| Professional Identity and Values Scale | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Attitudes Toward Women Scale | 0.81 | 0.83 |

Table 2.

Variable Level of Measurement and Analysis

| Instrument |

No. of Likert Anchors |

Level of Measurement |

Level of Analysis |

| Worktime Control Scale | 5 | Organizational | Individual |

| Perceived Organizational Family Support Scale | 7 | Organizational | Individual |

| Perceived Supervisory Family Support Scale | 7 | Organizational | Individual |

| Work-Family Conflict Survey | 5 | Individual | Individual |

| Work-Family Enrichment Scale | 5 | Individual | Individual |

| Professional Identity and Values Scale | 5 | Individual | Individual |

| Attitudes Toward Women Scale | 4 | Sociocultural | Individual |

Data Analyses

All statistical analyses were completed using SPSS (version 22; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using principal component analysis to reduce the number of items in the survey and to rotate the matrix of loadings to obtain oblique factors (direct oblimin rotation) because we expected factors to be correlated. We set a fixed number of factors at 3 based on our theory of individual, organizational, and sociocultural factors. Significant contribution to a factor within the pattern matrix was considered to be r > 0.30, which has been recommended in the athletic training literature.22 All items below a communality extraction of r = 0.40 were removed from the matrix if they did not significantly contribute to a factor. All items that contributed significantly to 1 factor and also contributed significantly to another factor at r > 0.30 were removed from the scale. Items were removed because of a low contribution to 1 factor or significant contributions to multiple factors or because the grouping of items in a specific factor did not result in a clear concept.

Content validity for the model occurred through expert review of the instrument. Conceptual definitions of the 3 factor levels (individual, organizational, and sociocultural) derived from the Dixon and Bruening10 model were provided to reviewers. The expert reviewers were 2 certified ATs currently employed in the academic collegiate setting and identified as having expertise related to the topics of work-life balance, job satisfaction, and career intentions of ATs. Reviewers independently ranked each item with regard to how well it fit each dimension (individual, organizational, sociocultural) but without knowledge of the subscale for which each individual question was specifically designed. The criteria used to retain each item depended on overall reviewer agreement with regard to the strength of the item as well as our opinions.

RESULTS

Participants

The participants in this study (N = 299) were ATs employed in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I, II, or III or a National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics college or university. Respondents identified as male (n = 130, 43.5%) or female (n = 169, 56.5%). All participants were NATA members. They were 34.0 ± 8.0 years old (range = 22–61 years), with 10.0 ± 8 years (range = 0.5–37 years) of experience working as an AT. Participants worked 60 ± 12.0 hours a week (range = 10–100 hours) in season, 46 ± 11.0 hours a week (range = 5–85 hours) during their off-season, and 21.0 ± 16.0 hours a week (range = 0–70 hours) during the summer. Our sample represented diversity in demographic variables as compared with the NATA membership statistics. Most of our participants were single (n = 161, 53.8%) and did not have children (n = 204, 68.2%). All of our participants who reported having children also self-reported being married.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

After the exploratory factor analysis, we reduced the model from 88 to 62 items. Each remaining item was gauged with regard to conceptual agreement by the expert reviewers and us. The model had a Cronbach α of r = 0.92 with a mean interitem correlation of 0.15 (−0.17 to 0.89), indicating that all items uniquely contributed to the overall instrument.

The exploratory factor analysis yielded 3 factors and 62 total items. All final items contributed significantly to 1 factor at a rotated component of r > 0.30. Based on factor analysis, we removed 26 questions from the initial model. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure for the scale was 0.889, with a significant Bartlett test of sphericity ( = 10 308.58, P = .000). The Tukey test for nonadditivity was statistically significant, indicating that the items were nonadditive. The pattern matrix for the model is presented in Table 3. Our proposed model can be found in the Figure.

= 10 308.58, P = .000). The Tukey test for nonadditivity was statistically significant, indicating that the items were nonadditive. The pattern matrix for the model is presented in Table 3. Our proposed model can be found in the Figure.

Table 3.

Professional Identity and Values Scale Pattern Matrixa Continued on Next Page

| Statement |

Factor |

||

| Organizational |

Sociocultural |

Individual |

|

| My supervisor is able to manage the department as a whole team to enable everyone's needs to be met. | 0.830 | ||

| My supervisor and I can talk effectively to solve conflicts between work and nonwork issues. | 0.821 | ||

| My supervisor works effectively with workers to creatively solve conflicts between work and nonwork. | 0.817 | ||

| My supervisor thinks about how the work in my department can be organized to jointly benefit employees and the company. | 0.814 | ||

| My supervisor demonstrates how a person can jointly be successful on and off the job. | 0.808 | ||

| My supervisor takes the time to learn about my personal needs. | 0.808 | ||

| My supervisor makes me feel comfortable talking to him or her about my conflicts between work and nonwork. | 0.796 | ||

| My supervisor demonstrates effective behaviors in how to juggle work and nonwork balance. | 0.796 | ||

| Employees really feel that the organization respects their desire to balance work and family demands. | 0.777 | ||

| My supervisor is a good role model for work and nonwork balance. | 0.775 | ||

| I can depend on my supervisor to help me with scheduling conflicts if I need it. | 0.772 | ||

| My supervisor is creative in reallocating job duties to help my department work better as a team. | 0.766 | ||

| In general, my organization is very supportive of its employees with families. | 0.765 | ||

| My organization is more family friendly than most other organizations I could work for. | 0.759 | ||

| My supervisor asks for suggestions to make it easier for employees to balance work and nonwork demands. | 0.749 | ||

| My supervisor is willing to listen to my problems in juggling work and nonwork life. | 0.748 | ||

| I can rely on my supervisor to make sure my work responsibilities are handled when I have unanticipated nonwork demands. | 0.739 | ||

| My organization is understanding when an employee has a conflict between work and family. | 0.708 | ||

| My organization has many programs and policies designed to help employees balance work and family life. | 0.666 | ||

| My organization makes an active effort to help employees when there is a conflict between work and family life. | 0.650 | ||

| My organization provides its employees with useful information they need to balance work and family. | 0.616 | ||

| My organization puts money and effort into showing its support of employees and families. | 0.596 | ||

| My organization helps employees with families find the information they need to balance work and family. | 0.550 | ||

| It is easy to find out about family support programs within my organization. | 0.507 | ||

| How much you are able to influence the following: The handling of private matters during the workday | 0.441 | ||

| How much you are able to influence the following: Length of workday | 0.405 | ||

| How much you are able to influence the following: The scheduling of work shifts | 0.400 | ||

| How much you are able to influence the following: The taking of unpaid leave | 0.371 | ||

| How much you are able to influence the following: The starting and ending times of a workday | 0.357 | ||

| How much you are able to influence the following: The taking of breaks during workday | 0.349 | ||

| How much you are able to influence the following: The scheduling of vacations and paid days off | 0.349 | ||

| The intellectual leadership of a community should be largely in the hands of men. | 0.740 | ||

| Women should be concerned with their duties of childbearing and house tending rather than with desires for professional and business careers. | 0.698 | ||

| On the average, women should be regarded as less capable of contributing to economic production than are men. | 0.659 | ||

| Sons in a family should be given more encouragement to go to college than daughters. | 0.641 | ||

| It is ridiculous for a woman to run a locomotive and for a man to darn socks. | 0.636 | ||

| A woman should not expect to go to exactly the same places or to have quite the same freedom of action as a man. | 0.621 | ||

| In general, the father should have greater authority than the mother in the bringing up of children. | 0.619 | ||

| There are many jobs in which men should be given preference over women in being hired or profited. | 0.566 | ||

| The modern girl is entitled to the same freedom from regulation and control that is given to the modern boy. | 0.561 | ||

| Women should be given equal opportunity with men for apprenticeship in the various trades. | 0.493 | ||

| Under modern economic conditions with women being active outside the home, men should share in household tasks such as washing dishes and doing the laundry. | 0.486 | ||

| Intoxication among women is worse than intoxication among men. | 0.472 | ||

| Women should worry less about their rights and more about becoming good wives and mothers. | 0.472 | ||

| There should be a strict merit system in job appointment and promotion without regard to sex. | 0.450 | ||

| A woman should be as free as a man to propose marriage. | 0.446 | ||

| Women should be encouraged not to become sexually intimate with anyone before marriage, even their fiancés. | 0.436 | ||

| Telling dirty jokes should be mostly a masculine prerogative. | 0.435 | ||

| Both husband and wife should be allowed the same grounds for divorce. | 0.412 | ||

| Women should assume their rightful place in business and all the professions along with men. | 0.361 | ||

| Swearing and obscenity are more repulsive in the speech of a woman than of a man. | 0.358 | ||

| It is insulting to women to have the “obey” clause remain in the marriage service. | 0.331 | ||

| I feel comfortable with my level of professional experience. | 0.788 | ||

| I feel confident in my role as an athletic training professional. | 0.759 | ||

| I have developed a clear role for myself with the athletic training profession that I think is congruent with my individuality. | 0.747 | ||

| I am unsure about who I am as an athletic trainer. | 0.719 | ||

| I am still in the process of determining my professional approach. | 0.705 | ||

| At this stage in my career, I have developed a professional approach that is congruent with my personal way of being. | 0.695 | ||

| I understand theoretical concepts but I am unsure how to apply them. | 0.688 | ||

| I have developed personal indicators for gauging my own professional success. | 0.566 | ||

| Overall, I do not feel confident in my role as an athletic trainer. | 0.529 | ||

| Based on my level of experience within the athletic training profession, I have begun developing specialization within the field. | 0.502 | ||

| Percentage of variance | 23.14 | 9.98 | 7.94 |

| Eigenvalue | 14.35 | 6.19 | 4.93 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: oblimin with Kaiser normalization.

Figure.

Proposed multilevel model of the work-life interface among collegiate athletic trainers.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of our study was to validate a model of the work-life interface among an AT population using multiple factorial levels. Exploratory factor analysis of our model indicated it was a valid and reliable measure of the work-life interface for collegiate ATs. We were able to maintain questions related to all 3 levels of factors and reduced the scale from 88 to 62 questions. The scale created for this study was based on the work-life interface research conducted by Dixon and Bruening,10 who highlighted the influence of individual, organizational, and sociocultural factors. Simply stated, their model illustrated the complexity of the concepts of work-life balance and suggested the need for a comprehensive understanding of all factors and their relationships to organizational constructs such as job satisfaction and career intentions that affect the work-life interface.

Removal of Scale Items

Based on the exploratory factor analysis, all questions from the work-life conflict and work-life enrichment Likert scales were removed from our instrument. The work-life conflict constructs were initially included because of the abundance of literature indicating the influence this construct may have on the work-life interface. Authors of a 2010 meta-analysis23 examining consequences associated with work-family enrichment suggested that it was positively related to job satisfaction, physical health, mental health, affective commitment, and family satisfaction. The athletic training literature has indicated that work-life conflict negatively affects both job and life satisfaction and is positively related to burnout and intention to leave an organization.3 Although it was initially surprising that we removed all items related to work-life conflict and work-life enrichment, our results may be explained by recent qualitative findings highlighting sociocultural effects on career intentions. Eason13 found that women who had traditional sociocultural beliefs, meaning they viewed women as “caretakers” and men as “breadwinners,” and men who had egalitarian beliefs indicated their desire to depart the collegiate clinical setting or the athletic training profession altogether. Conversely, men with traditional views and women with egalitarian views indicated their intention to continue working in the collegiate setting. Because the constructs of work-life conflict and work-life enrichment may understandably be influenced by sociocultural beliefs and further by gender, these items were ultimately removed from the scale.

Explaining the Rationale for a Blended Approach

Although individual factors may affect choices, Allison24 argued that those choices and subsequent actions are shaped and perhaps rooted in organizational policies and environments that engender behaviors that then influence organizational and individual actions. The organizational approach to the work-life interface examines characteristics of the workplace and their relationship to individual behavior. Organizational factors have been studied within an athletic training population and suggested to have effects on the work-life interface of ATs. Salary,7 nature of the work,7 work overload,25 the organizational climate,25 and staffing25 were identified as strong predictors of intention to leave the profession, whereas job title and National Collegiate Athletic Association division minimally affected job satisfaction and career intentions.7 However, these results do not explain the findings of Naugle et al,26 who reported that men described lower levels of burnout despite working more hours than women. Rather, the model depicted in athletic training offers a perspective that organizational and individual factors may be interrelated and influence perceptions of satisfaction, balance, and intentions. The nature of the job (demands, hours worked, etc) may be perceived differently by each individual AT, especially as it fits within the AT's family and personal values. Additionally, the inclusion of sociocultural factors in our model suggests that examination of the work-life interface needs to include sociocultural factors, particularly gender ideology, and an understanding that social norms and values have the ability to influence the interface.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our results may not be generalizable to all athletic training professionals because we sampled only ATs employed in the collegiate setting. The possibility exists that the job demands and patient populations of other job settings may affect job satisfaction and career intentions. Sampling ATs employed in different clinical settings is warranted to obtain more information regarding job satisfaction and career intentions across the profession. Also, the scales we selected to include in this model could have affected the results. Although the scales were carefully selected to represent multiple constructs and multiple levels and guided by prior work conducted by Dixon and Bruening,10 it was not possible to include all individual, organizational, or sociocultural constructs. For example, we did not include scales related to personality or resiliency, which may influence the overall multilevel nature of an individual's job satisfaction and career intentions. Similarly, confirmatory factor analysis is needed to solidify the scale items and their potential application to the athletic training profession. Our model also needs to be assessed in regard to test-retest reliability.

Future researchers should look beyond the collegiate athletics setting to include secondary schools and other employment settings that have often been described as more structured and family oriented. Future investigators should include scales that focus on the individual factors of the AT, including resiliency and hardiness, which are known to be related to persistence and effective coping strategies. Our data were also collected at one point in time; longitudinal data may offer better insights into the cyclic nature of these constructs, as well as allow researchers to appreciate whether job satisfaction and career intentions are in fact transitory.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results indicate that a model of multilevel factors was a valid and reliable measure of job satisfaction and career intentions among ATs employed in the collegiate clinical setting. This scale highlights the importance of examining the work-life interface from a multilevel perspective and of avoiding attribution of only individual or organizational factors to concerns about the attrition within our profession. The work-life interface is a multifaceted subject, and in order to create retention strategies, we need to better understand the reasons for career departures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruening JE, Dixon MA. Situating work-family negotiations within a life course perspective: insights on the gendered experiences of NCAA Division I head coaching mothers. Sex Roles. 2008;58(1–2):10–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortese CG, Colombo L, Ghislieri C. Determinants of nurses' job satisfaction: the role of work-family conflict, job demand, emotional charge and social support. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(1):35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ, Burton LJ. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eberman LE, Kahanov L. Athletic trainer perceptions of life-work balance and parenting concerns. J Athl Train. 2013;48(3):416–423. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45(3):287–298. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson M, Dunnagan T. Analysis of a worksite health promotion program's impact on job satisfaction. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40(11):973–979. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199811000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terranova AB, Henning JM. National Collegiate Athletic Association Division and primary job title of athletic trainers and their job satisfaction or intention to leave athletic training. J Athl Train. 2011;46(3):312–318. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.3.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A, Pitney WA. Achieving work-life balance in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting, part I: the role of the head athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2015;50(1):82–88. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozlowski S, Klein K. A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations. In: Klein KJ, Kozlowski SJ, editors. Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass;; 2000. pp. 3–90. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Perspectives on work-family conflict in sport: an integrative approach. Sport Manage Rev. 2005;8(3):227–253. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. Athletic trainers with children: finding balance in the collegiate practice setting. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2011;16(3):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eason CM. A Multilevel Examination of Career Intentions in Athletic Training: Individual, Organizational, and Sociocultural Factors [dissertation] Storrs: University of Connecticut;; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Membership statistics. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. http://members.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/index.cfm Updated 2016. Accessed February 18, 2016.

- 15.Matthews RA, Kath LM, Barnes-Farrell JL. A short, valid, predictive measure of work-family conflict: item selection and scale validation. J Occup Health Psychol. 2010;15(1):75–90. doi: 10.1037/a0017443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kacmar KM, Crawford WS, Carlson DS, Ferguson M, Whitten D. A short and valid measure of work-family enrichment. J Occup Health Psychol. 2014;19(1):32–45. doi: 10.1037/a0035123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healey AC. Female Perspectives of Professional Identity and Success in the Counseling Field [dissertation] Norfolk, VA: Old Dominion University;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eason CM, Mazerolle SM, Denegar CR, Burton LJ, McGarry J. Validation of the professional identity and values scale among an athletic trainer population. J Athl Train. 2018;53(1):72–79. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-209-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ala-Mursula L, Vahtera J, Linna A, Pentti J, Kivimaki M. Employee worktime control moderates the effects of job strain and effort-reward imbalance on sickness absence: the 10-town study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(10):851–857. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jahn EW, Thompson CA, Kopelman RE. Rationale and construct validity evidence for a measure of perceived organizational family support (POFS): because purported practices may not reflect reality. Community Work Fam. 2003;6(2):123–140. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spence JT, Helmreich R, Stapp J. A short version of the Attitudes Toward Women Scale (AWS) Bull Psychon Soc. 1973;2(4):219–220. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burton LJ, Mazerolle SM. Survey instrument validity part I: principles of survey instrument development and validation in athletic training education research. Athl Train Educ J. 2011;6(1):27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNall LA, Nicklin JM, Masuda AD. A meta-analytic review of the consequences associated with work–family enrichment. J Bus Psychol. 2010;25(3):381–396. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allison GT. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. Boston, MA: Little Brown;; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Pitney WA. Athletic trainers' barriers to maintaining professional commitment in the collegiate setting. J Athl Train. 2015;50(5):524–531. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.1.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naugle KE, Behar-Horenstein LS, Dodd VJ, Tillman MD, Borsa PA. Perceptions of wellness and burnout among certified athletic trainers: sex differences. J Athl Train. 2013;48(3):424–430. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]